Home Page

Home Page

Aristophanes.

The Clouds.

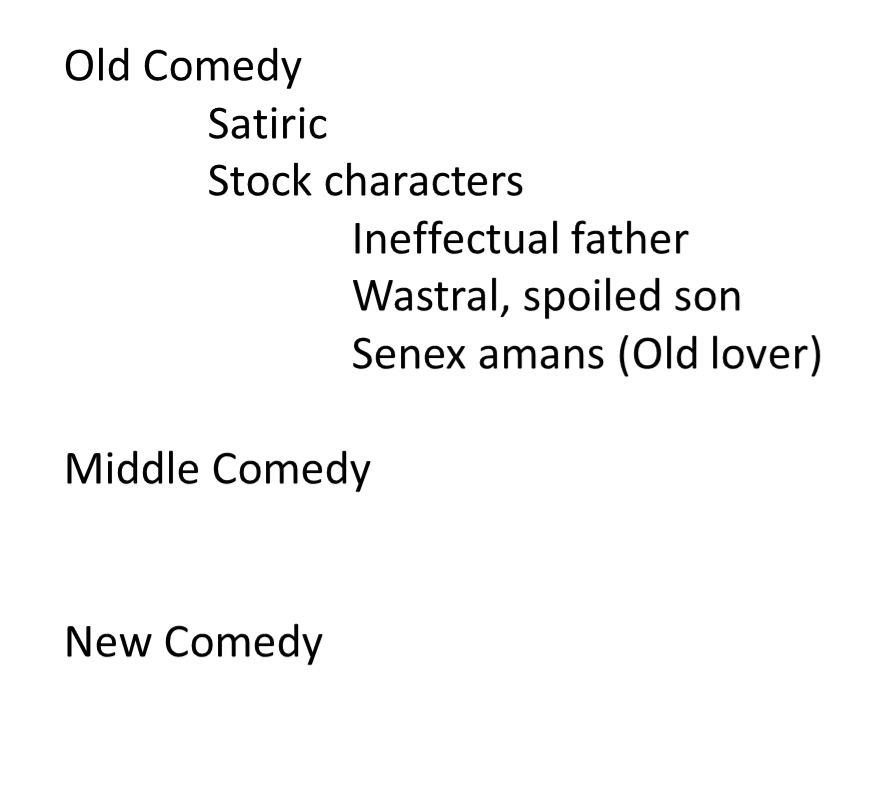

The Clouds by Aristophanes is a comedy written in 432 B.C. Aristophanes lived 446 BC – 386 BC and was a playwright in ancient Athens. Except for a few fragments by other comics, his plays are all that remain of Old Comedy. Old Comedy was Middle Comedy and then New Comedy. Old Comedy was characterized by its lampooning of real people, institutions, and events. In that way, it's similar to satire. New Comedy (Middle Comedy is mostly lost) avoided portraying actual people — it was too dangerous for the playwright to anger powerful tyrants. Instead, we find an increase in the use of stock characters, which were present from the beginning. New Comedy is the ancestor of both Shakespeare's comedies and the modern sit-com. They endlessly mix and re-mix the stereotypical characters — the henpecked husband, the over-bearing wife, the wastrel son, the braggart soldier, the bothersome neighbor.

If Medea represents the great fear of the patriarchal

Athenians — a strong woman — The Clouds presents us with

the inverse fear — that of being an ineffectual father.

Strepsiades is unable to discipline either his wife (now

deceased, apparently) or his son, Phidippides. As a

result, he is heavily in debt and needs to figure out a way out

of his debts. At the time, citizens were required to

present their own case, but they normally paid a person familiar

with the legal system to write their speeches for them. In

this case, Strepsiades decides to go to school himself to learn

to write his own speech.

Strepsiades ends up at the Thinkery (or Thoughtery), headed by

Socrates. Given that Plato didn't start writing his

dialogues until after the death of Socrates in 399 B.C., this

play is the introduction of Socrates on the stage of world

literature. Aristophanes makes Socrates into a buffoon,

entering the play in the basket (machina, Latin; mēchanē,

Greek) hanging above the stage and spouting, "I walk on air, and

contemplate the sun." The machinery was designed to portray the

grandeur of the gods who normally rode in it, but it could also

be ripe for satire.

It would only take a few twitches on the rope to

make the machinery into a farce. The farce still

works. In 1988, George H. W. Bush was running against

Michael Dukakis for President. Bush was a very tall

candidate, and Dukakis a very short one. That was also

the year that a study came out that showed that in a

Presidential race, the taller candidate typically won. Problem:

how how to have a presidential debate that did not give an

unfair advantage to the taller candidate.

Solution: a platform that adjusted to the height of the

candidate. The lift was a great success, at least until

Saturday, when Saturday Night Live got a hold of it.

Socrates was a good target for satire because he

was bald, ugly, and went around barefoot when any other

citizen who could afford it would wear sandals. He was

also local, where many of the Sophists he debated were from

other cities and less well-known. Aristophanes makes

Socrates into a Sophist, which he was not. It may have

been difficult for the towns people to tell the difference

among the schools of thought; it was easier to just lump them

all together.

Aristophanes DOES give us an insight into the

early phases of the Greek enlightenment. This was the

first time that analytical thought had been applied to

question of how things worked. The title comes from the

play's contention that Zeus is not really the god who causes

thunder; that would be the Clouds. In the context of the

play, this is the wrong answer, but it turns out to be much

closer to the answers the will eventually come from philosophy

and science about the nature of lightning. We see a

similar debate in The Lion King, where the mythic

answer is correct in the movie and the literally correct

answer gets laughed at:

Aristophanes even sometimes anticipates the eventual

scientific revolution; figuring out how far a flea can jump

compared to its body size is empirical research of the kind

that biologists actually do. We also see the scholars

trying to teach the thick-headed Strepsiades poetic

meter. The dactyl (Greek for 'finger') is a long vowel

followed by two short ones (— ~ ~); supposedly because the

meter bears a resemblance to the a finger with its one

longer joint and two shorter ones. Strepsiades

responds sticking his middle finger out at Socrates, which

is the first reference I've found in history to "the

finger." I had no idea the gesture was so ancient.

The play had such an impact and hurt Socrates' feelings so

much that 30 years later when he was on trial for his life,

he spent a good bit of his defense complaining about how

unfairly he had been treated by Aristophanes. He even

quoted a few lines. Think he had the whole thing

memorized?