Home Page

Home Page The Telephone Game and

Textual Criticism

If you are interested in doing textual criticism, the Greek

Bible is one of your best choices. The bulk of ancient books

have very few surviving mss (ms=one manuscript: mss=multiple

manuscripts). Often there is only one extant copy of a book,

such as de Rerum Natura by Lucretius. The Greek Bible,

on the other hand, has 5,800 surviving mss. The Vulgate has

10,000 surviving mss. The great number of mss create their own

set of problems; critics have to find ways to wade through all

the evidence. My textual criticism professor used to say that we

needed to weigh the evidence, not count it. That

is, if 1 ms introduces a mistake, and 999 copy it, then that is

1 witness to the reading, not 1,000. Hence the importance of

grouping mss into families.

Our original text is the 1st edition of the 1611 KJV. For

handwritten books, the text created by the author is called the

autograph, which in Greek literally means written by

oneself. We don't have autographs of any of the books in

the Bible. What we have are copies and copies of copies.

There are 4 branches of mss witnesses of Greek Bible: the

Alexandrian, the Caesarean, the Western, and the Byzantine. For

our class, I set up two groups to make the copies. Imagine

having only the last two copies made, one from each family, and

trying to reconstruct the original KJV.

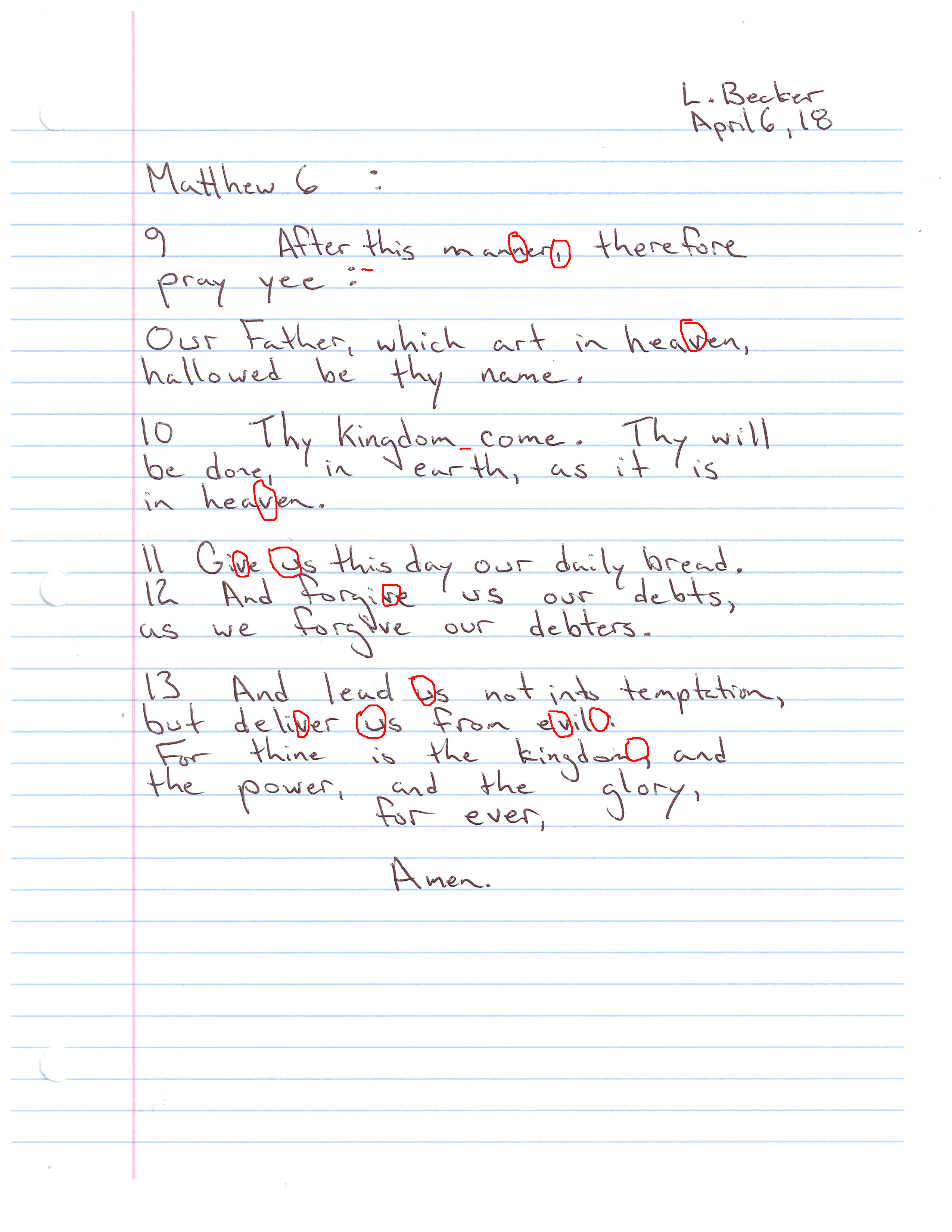

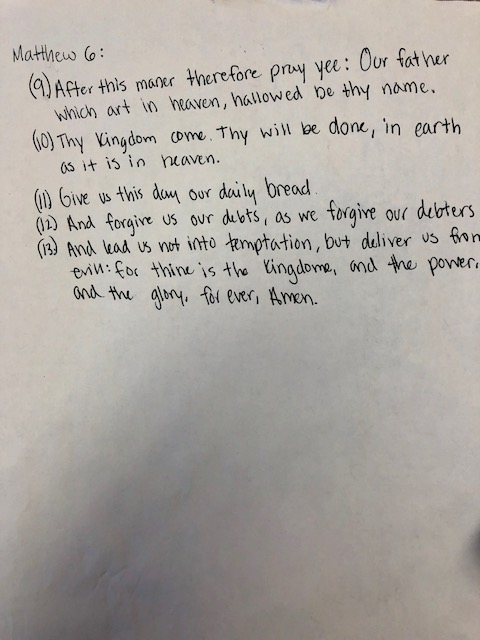

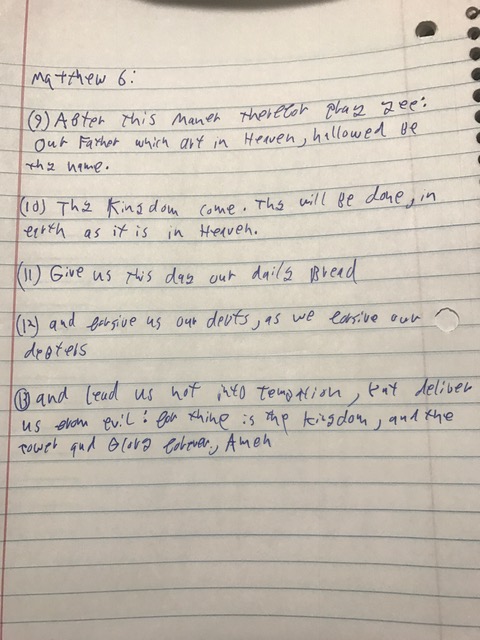

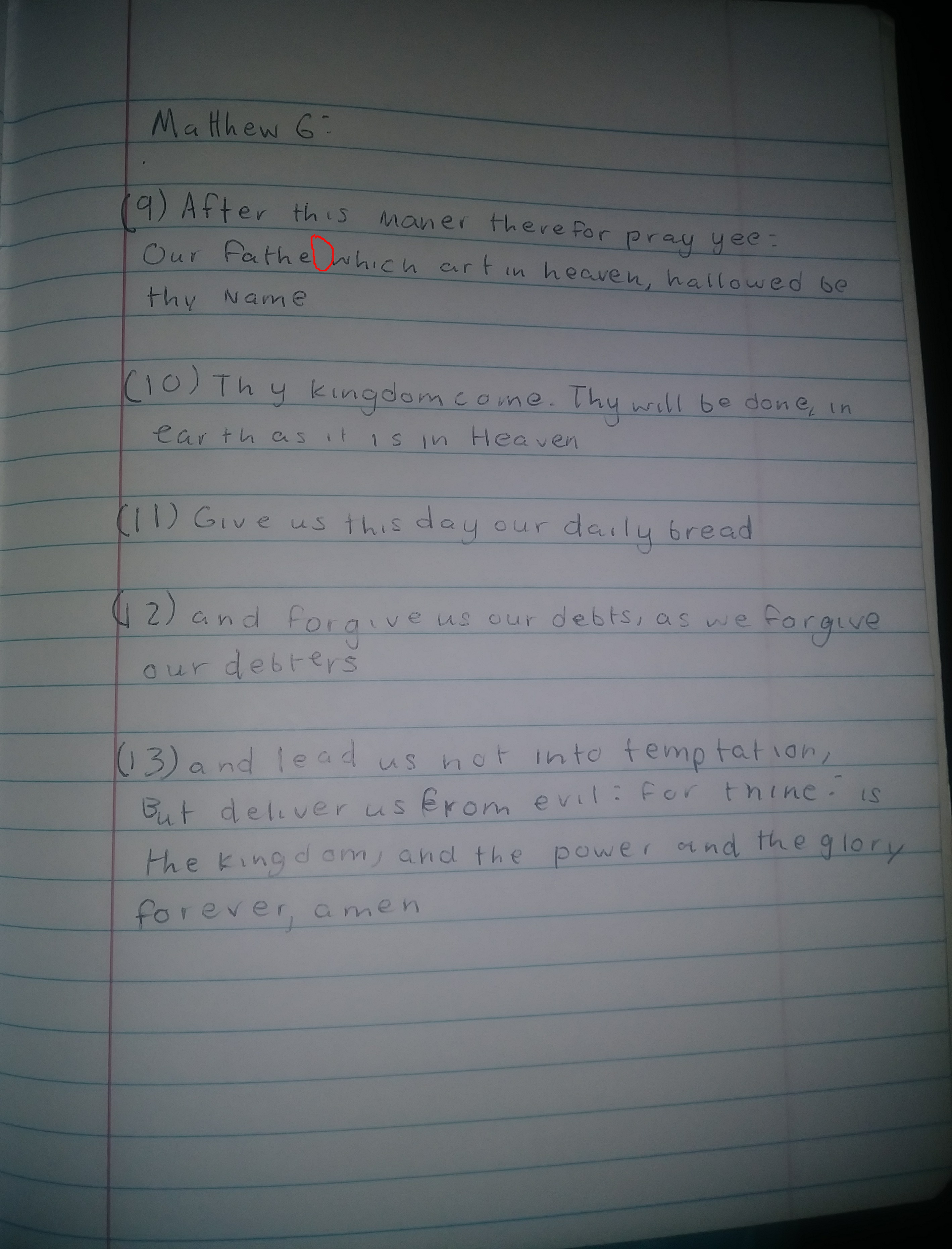

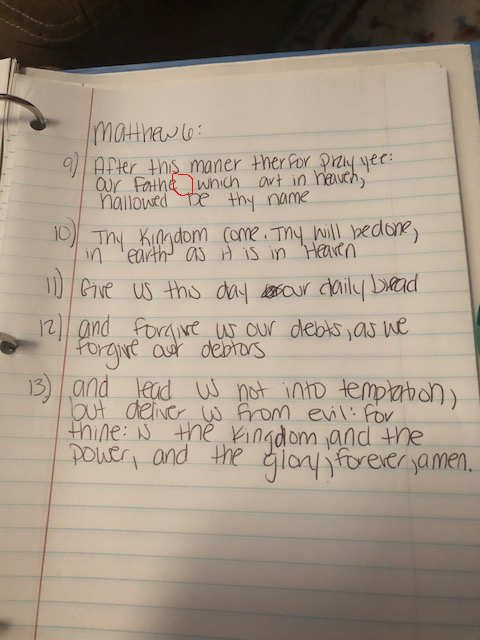

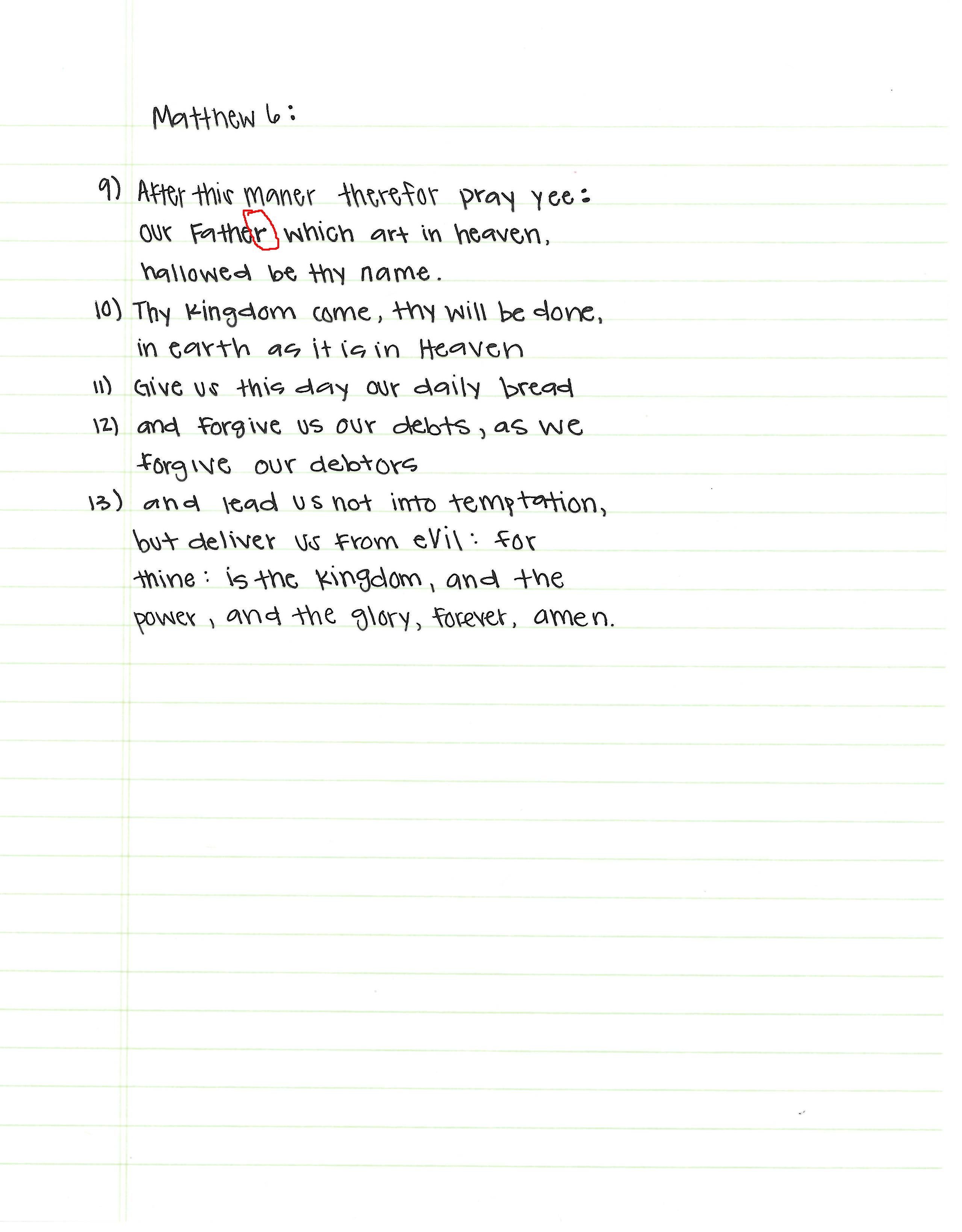

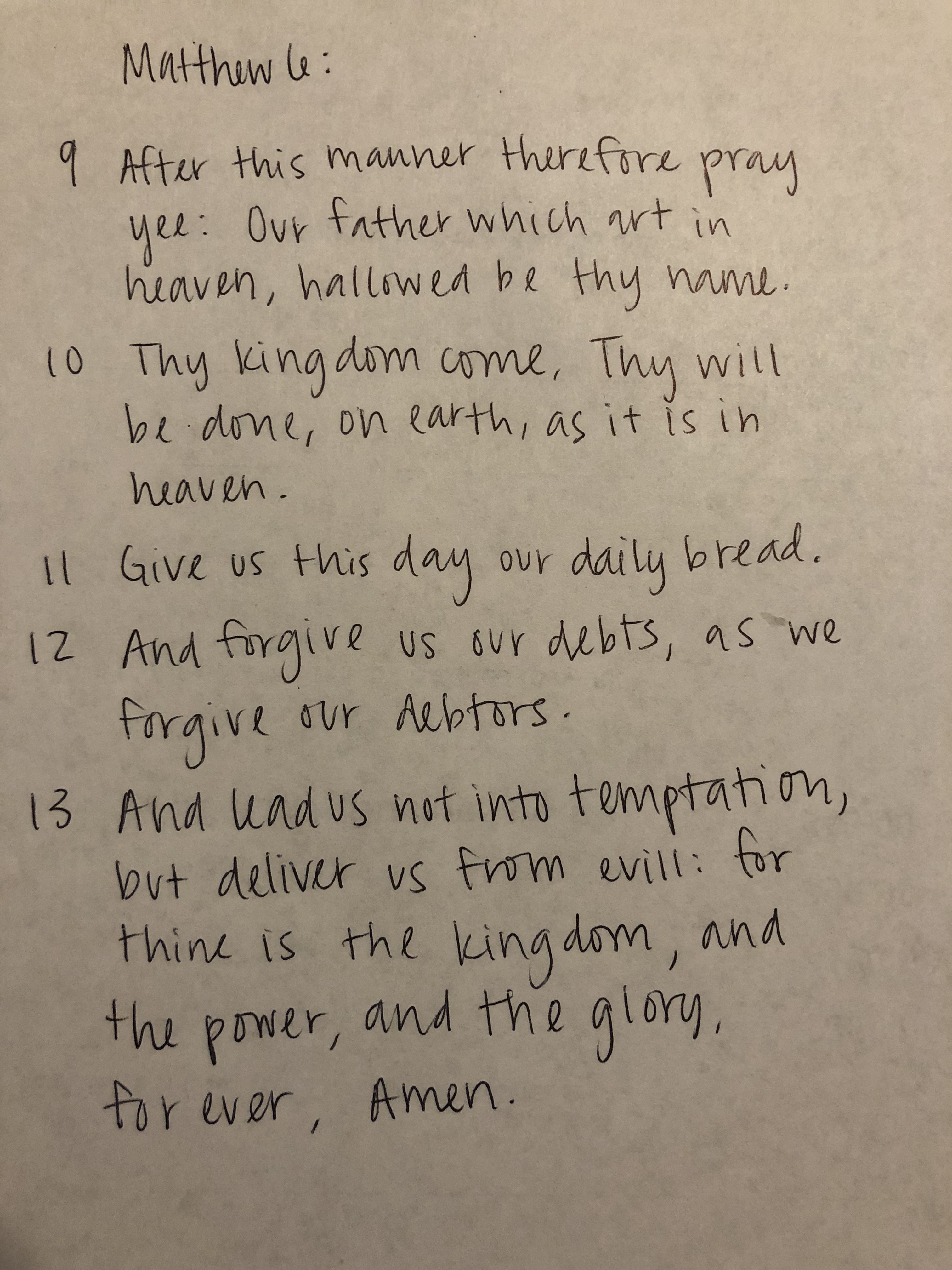

I have labelled our two groups "Family 1" (f01) and "Family 2"

(f02). Each copy is numbered according to its order in the

assignment (c01, c02, etc.). We have an advantage in knowing the

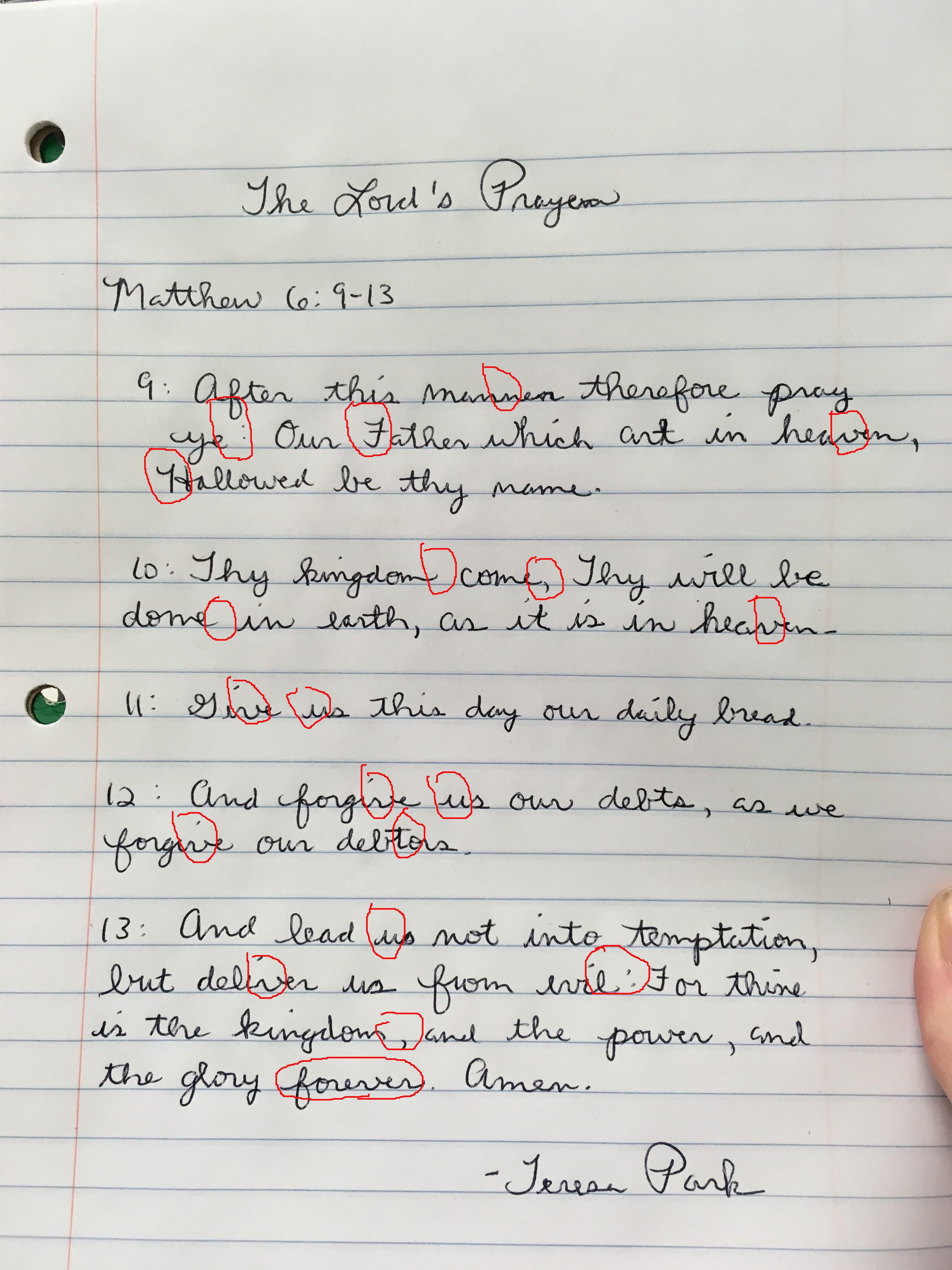

relative relationship among our mss. In the image below from the

United Bible Society's edition, you can see in the footnote that

Biblical scholars have created such a numbering system for

Biblical mss.

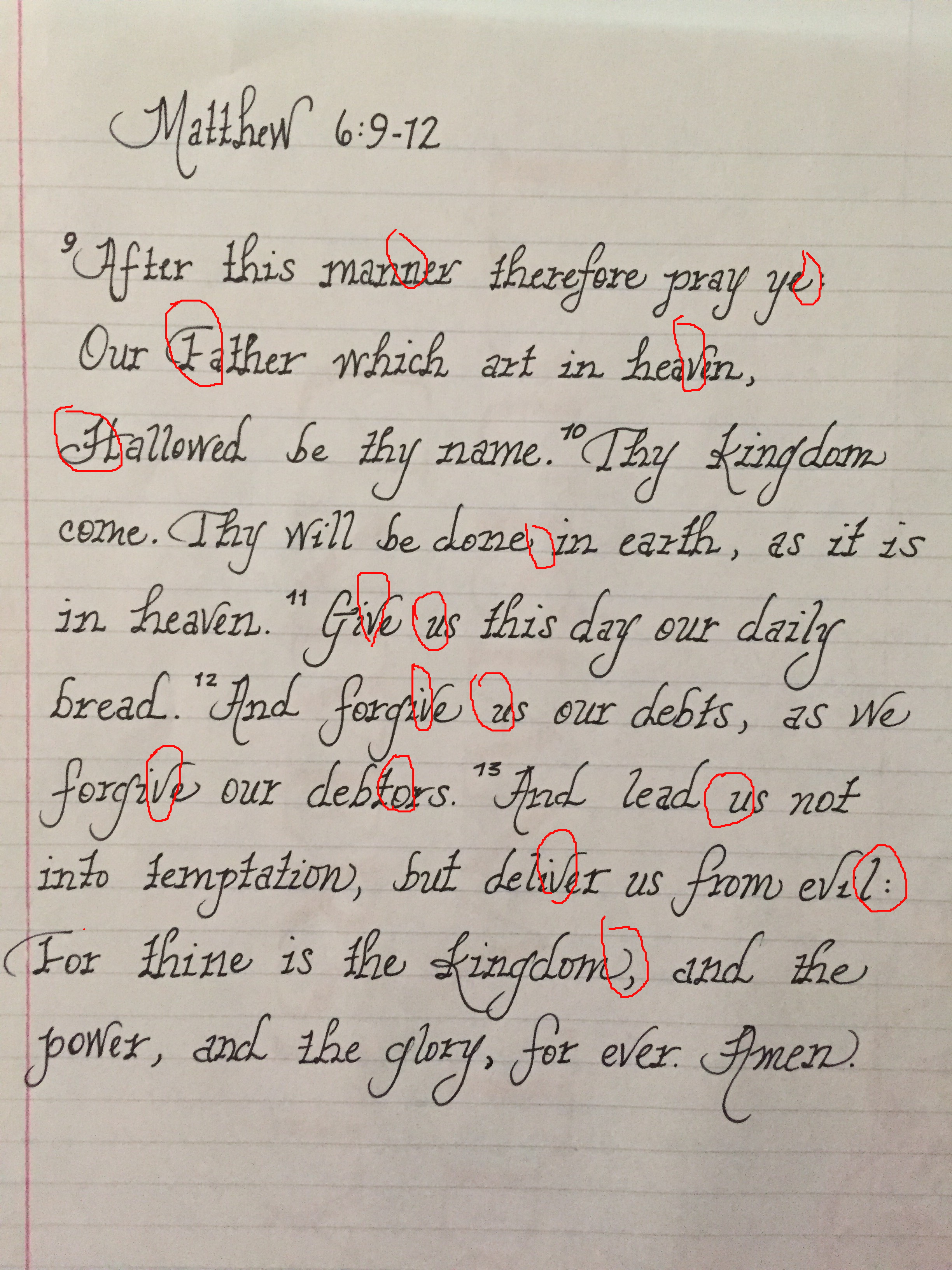

The comparison of various mss is called collation. I've

collated a sample of them. I collated my copy with the original

& found a couple of mistakes. Since there are errors in the

copy used to create both families, it would be hard to get

behind that to the autograph, at least based on mss evidence.

That's how we get into "critical emendations," i.e., educated

guesses about the original text. Such are the limits of textual

criticism.

To some degree the mistakes that enter, they fall into

predictable patterns based on who is making the copy and how.

For instance, in some scriptoria, one monk would read the text,

and several would copy it down. But they were prone to errors of

the ear -- mistaking one vowel for a vowel that sounds

the same. Copying by looking at one ms and writing another leads

to errors of the eye. If two lines close to each other

end with the same word, for example, you might skip down the the

second line and leave out the ones in between.

The pattern of mistakes we made make our two families most like

the Byzantine text type.

- The Byzantine scribes were highly educated, as are you.

- They were working in their first language, Greek. You are working with your first language, English. If I had given you the Lord's Prayer in Greek or Latin, then we would have produced as Western text type. They spoke Latin as their first language, and so their Greek mistakes tended to be random spelling errors, etc.

- They were working many centuries after the original text, as

are you. So they and we face a specific set of temptations in

copying. We want to update the text to modern standards. We

first change from blackletter font to something we are more

used to reading now. The Byzantine monks were also dealing

with orthographical changes.

- I was pleasantly surprised that the "yee" lasted as long as

it did. I myself changed "kingdome" to "kingdom." "Maner"

predictably became "manner," "evill" became "evil," and other

spelling and punctuation changes crept in that made the

language closer to standard current English, especially

regarding the letters 'u' and 'v.'

There is no 'V.'

By far the biggest creator of chaos in our game of telephone

was due to a subtile shift in the English alphabet since the

time of King James. I found out

something about the alphabet in the King James era that I didn't

know until now — there is no 'v.' Or maybe no 'u.' When you read

Latin, some texts show 'u,' 'v,' 'i,' & 'j'. Some show 'u,'

'v,' & 'i,' and some just show 'u,' & 'i.' That's

because originally 'i' and 'u' were like our 'y'; sometimes a

consonant, sometimes a vowel. Likewide, in the English of the

first edition of the KJV, there was only 'u.' Or maybe only 'v.'

Sometimes it was a consonant; sometimes a vowel. The difference

in shape was based upon the position in the word. At the

beginning of word, it was printed 'v'; in the middle, 'u.' So

you would "saue vp" rather than "save up."

Fall 2019 Class

The Exemplar

Family 1 — The Acton Family

Family 2 —Jones Family

2018 Class

The Exemplars

Family 1

Family 2

Home Page