Home Page

Home Page

- Lecture.mp3

- Listen in iTunes

- Listen on Stitcher

-

My initial definition. An ethical technical

communicator is one who produces good technical communication.

Of course, pretty much everything in that definition itself

needs to be defined.

- Good technical communication. I've taken these from

Markel's Technical Communication, our textbook for

English 303.

- Honesty

- Clarity

- Accuracy

- Comprehensiveness

- Accessibility

- Conciseness

- Professional Appearance

- Correctness

- Bad technical communication is technical

communication that fails to be good in one or more of the

categories above. This is a good-faith failure that happens

in spite of the best efforts of the communicator.

- Evil technical communication fails to be good technical communication on purpose. It's different from the previous category in that it involves bad faith on the part of the communicator. Here are some examples of evil technical communication going back to ancient times.

- The Greek Sophists, at least as characterized by Plato.

In his view, they were willing to argue any side of an

issue without regard for the actual truth.

- Aristophanes The Clouds portrays Socrates as a sophist. At one point has a debate between Just Discourse (Δίκαιος Λόγος, Dikaios Logos) and Unjust Discourse (Ἄδικος Λόγος, Adikos Logos). (I misremembered the terminology in spoken lecture as Good Discourse vs Evil Discourse). Unjust Discourse wins without a problem because it can use any argument, while Just Discourse has to stick to the truth.

- The Catholic Church in its fight with Galileo.

- The anti-Darwinism of some Protestant denominations. See

the Creation Museum.

- The Tobacco Institute, which used to publish false studies throwing doubt on the science of the harmful health effects of tobacco use.

- Climate change deniers. These may be the worst of the lot because the result of their actions risk destroying the livability of the only world we have to live in.

The Current State of Ethics

- Alasdair MacIntyre starts After Virtue with "A Disquieting Suggestion." He has us imagine a world where an anti-science cult has taken over society and is systematically killing scientists and destroying science books. Eventually rational people overthrow the cult and start to rebuild science. They will be doing so with bits and pieces of both real and fake science divorced from their original systems. We've seen this kind of apocalypse in numerous dystopian novels.

- MacIntyre argues that this has already happened to ethics.

The ability to do ethics rationally has been derailed by the

Enlightenment. The Enlightenment ushered in the modern

scientific era, but its theory of knowledge is that science

can discover facts but not values.

- ′ As we saw above, the collapse of ethics in the

post-Enlightement world endangers the scientific branch of

knowledge as well. Highly paid propaganda mills muddy the

waters of science by churning out lies to counter the truth,

unencumbered by ethical constraints. If I can believe

whatever I want to about ethics based on my strong feelings,

why not science also?

MacIntyre suggests the way to fix this breakdown is a return

to the beginning of ethics: Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics.

An Excerpt from MacIntyre

After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, 2nd ed.

by Alasdair MacIntyre

A Disquieting Suggestion

In such a culture men would use expressions such as 'neutrino', 'mass', 'specific gravity', 'atomic weight' in systematic and often interrelated ways which would resemble in lesser or greater degrees the ways in which such expressions had been used in earlier times before scientific knowledge had been so largely lost. But many of the beliefs presupposed by the use of these expressions would have been lost and there would appear to be an element of arbitrariness and even of choice in their application which would appear very surprising to us. What would appear to be rival and competing premises for which no further argument could be given would

This imaginary possible world is very like one that some science fiction writers have constructed. We may describe it as a world in which the language of natural science, or parts of it at least, continues to be used but is in a grave state of disorder. We may notice that if in this imaginary world analytical philosophy were to flourish, it would never reveal the fact of this disorder. For the techniques of analytical philosophy are essentially descriptive and descriptive of the language of the present at that. The analytical philosopher would be able to elucidate the conceptual structures of what was taken to be scientific thinking and discourse in the imaginary world in precisely the way that he elucidates the conceptual structures of natural science as it is.

What is the point of constructing this imaginary world inhabited by fictitious pseudo-scientists and real, genuine philosophy? The hypothesis which I wish to advance is that in the actual world which we inhabit the language of morality is in the same state of grave disorder as the language of natural science in the imaginary world which I described. What we possess, if this view is true, are the fragments of a conceptual scheme, parts which now lack those contexts from which their significance derived. We possess indeed simulacra of morality, we continue to use many of the key expressions. But we have — very largely, if not entirely — lost our comprehension, both theoretical and practical, of morality.

Chapter 2 — The Nature of Moral Disagreement Today and the Claims of Emotivism

The most striking feature of contemporary moral utterance is that so much of it is used to express disagreements; and the most striking feature of the debates in which these disagreements are expressed is their interminable character. I do not mean by this just that such debates go on and on and on — although they do — but also that they apparently can find no terminus. There seems to be no rational way of securing moral agreement in our culture.

They are of three kinds. The first is what I shall call, adapting an expression from the philosophy of science, the conceptual incommensurability of the rival arguments in each of the three debates. Every one of the arguments is logically valid or can be easily expanded so as to be made so; the conclusions do indeed follow from the premises. But the rival premises are such that we possess no rational way of weighing the claims of one as against another. For each premise employs some quite different normative or evaluative concept from the others, so that the claims made upon us are of quite different kinds.

- In the first argument, for example, premises which

invoke justice and innocence are at odds with premises

which invoke success and survival;

- in the second, premises which invoke rights are at odds

with those which invoke universalizability;

- in the third it is the claim of equality that is matched against that of liberty.

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics.

1

Every art and every inquiry, and similarly every action and pursuit, is thought to aim at some good; and for this reason the good has rightly been declared to be that at which all things aim. But a certain difference is found among ends; some are activities, others are products apart from the activities that produce them. Where there are ends apart from the actions, it is the nature of the products to be better than the activities. Now, as there are many actions, arts, and sciences, their ends also are many; the end of the medical art is health, that of shipbuilding a vessel, that of strategy victory, that of economics wealth. But where such arts fall under a single capacity- as bridle-making and the other arts concerned with the equipment of horses fall under the art of riding, and this and every military action under strategy, in the same way other arts fall under yet others — in all of these the ends of the master arts are to be preferred to all the subordinate ends; for it is for the sake of the former that the latter are pursued. It makes no difference whether the activities themselves are the ends of the actions, or something else apart from the activities, as in the case of the sciences just mentioned.

2

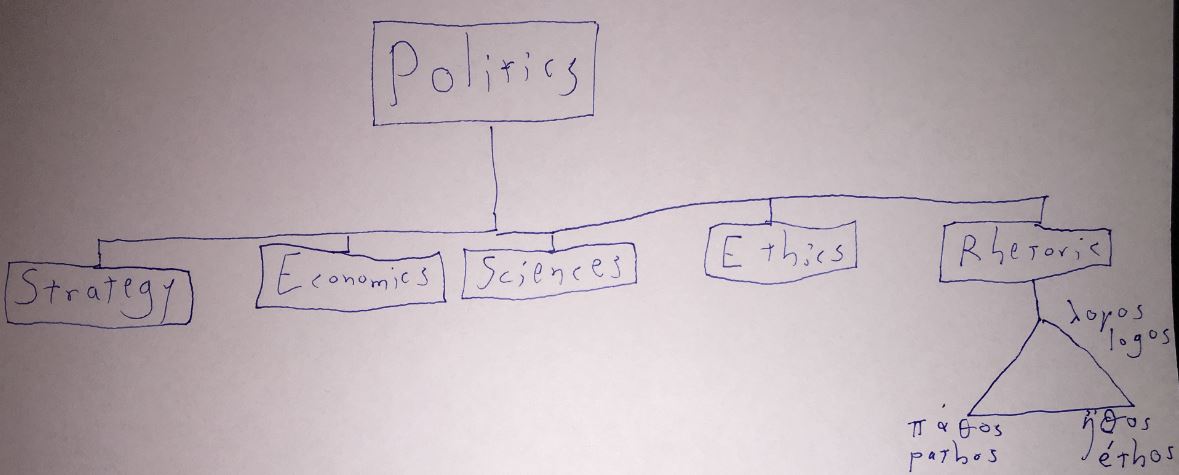

If, then, there is some end (τέλος, télos) of the things we do, which we desire for its own sake (everything else being desired for the sake of this), and if we do not choose everything for the sake of something else (for at that rate the process would go on to infinity, so that our desire would be empty and vain), clearly this must be the good (τἀγαθὸs, tagathňs from to agathňs, the good) and the chief good (ἄριστον, áristos). Will not the knowledge of it, then, have a great influence on life? Shall we not, like archers who have a mark to aim at, be more likely to hit upon what is right? If so, we must try, in outline at least, to determine what it is, and of which of the sciences or capacities it is the object. It would seem to belong to the most authoritative art and that which is most truly the master art (ἀρχιτεκτονική, architektoniké). And politics appears to be of this nature; for it is this that ordains which of the sciences should be studied in a state, and which each class of citizens should learn and up to what point they should learn them; and we see even the most highly esteemed of capacities to fall under this, e.g. strategy, economics, rhetoric; now, since politics uses the rest of the sciences, and since, again, it legislates as to what we are to do and what we are to abstain from, the end of this science must include those of the others, so that this end must be the good for man. For even if the end is the same for a single man and for a state, that of the state seems at all events something greater and more complete whether to attain or to preserve; though it is worth while to attain the end merely for one man, it is finer and more godlike to attain it for a nation or for city-states (πόλις, pólis). These, then, are the ends at which our inquiry aims, since it is political science (πολιτική, politiké), in one sense of that term.

In my opinion, Aristotle's biggest contribution was in his

creation of the taxonomy of knowledge. Here we see the

taxonomy of politics, with some of its sub-categories.

Because Aristotle defines ethics as a sub-category of

politics, ethics requires the presence of the city-state (πόλις, pólis)

to exist in the Aristotelian sense. So what came before?

Greeks had a sense of right and wrong, but it was rooted in

the social organization of the era.

οἶκος oikos. House, household. The basic morality of the society based in the household is that blood is thicker than water. You side with your brother against your cousin; the three of you side together against a stranger. Even if somebody in your family hurts an outsider, you side with your family.

ξενία, xenia.

Hospitality is the only larger instituion than the

household. A ξενος/ξενα xenos/xena is

stranger who comes to your home; ξενία, xenia

is the hospitality you show them. This typically

involves giving the guest a place to stay, feasting, and

giving gifts for them to take back home. At some point in the

future, you might visit them and become the guest yourself and

receive the hospitality. After this, the two households will

become allies. We see the importance of hospitality at the

beginning of Beowulf, who goes to help Hrothgar to

repay a debt of hospitality that Hrothgar had shown Beowulf's

father.

ἐχθρά echthra

— enmity. νεῖκος neikos — feud. A feud

is what happens when something goes wrong either within the

household or between houses. Either way, the result is a feud.

Early on, there was no social organization that could stop a

feud. The logic of a feud is for it to continue until one or

both sides were all dead. The best place to see this dynamic

in modern popular culture is in mafia movies like the Godfather.

The familia doesn't go to the police when its people

are killed; it takes care of its own vengeance.

Δίκη Dike — Justice. The goddess Justice is familiar because of her depictions with a sword, a set of scales, and in her Roman version, blindfolded. During the oikos era, the family sought justice directly; there was little to distinguish justice from vengeance. The amount of justice you could get depended on the strength of your family. And because you sought more in revenge than the other person had done, the cycle tended to escallate. You didn't seek justice through a modern trial.

In Aeschylus' Oresteia,

- the king has gotten justice through the Trojan War; the

gods decided it in the favor of the Greeks.

- His wife Clytemnestra sought justice against Agamemnon for

killing their daughter by throwing a net over him while he

bathed and stabbing him to death.

- Their son Orestes sought justice against Clytemnestra by

striking her down with a sword.

- Her furies sought to hound Orestes to death for his matricide. And all this was one cycle of revenge.

Ἄτη, ἄτη atē.

Atē

"personified, the goddess of mischief, author of rash

actions."

atē "bewilderment, infatuation,

caused by blindness or delusion sent by the

gods, mostly as the punishment of guilty rashness" (Liddell,

Scott, & Jones). So in the oikos, there is little

difference between atē

and dike.

People in their blindness think that they are seeking justice,

but each escallation only makes the situation worse.

At the end of the Odyssey, the

families of the suitors Odysseus killed showed up for revenge.

Athena appears in the sky and stops the fighting. This kind of

artificial ending was necessary because there was no human

institution that could stop the fighting.

The Divine

Command Theory. The appearance to Athena to tell them to

stop fighting brings us to another theory of morality — The

Divine Command Theory. According to this approach, morality is

based in following the commands of the gods. There are some

difficulties with this theory.

- I have some trouble seeing this approach as an approach to ethics, at least as defined by Aristotle. He wants to develop good judgment and habits of good behavior among his pupils so they could make wise decisions. The Divine Command theory mostly involves doing what you're told. It can be the opposite of using judgment.

- How do you know it's the gods telling what to do, and not your own wishful thinking? Does it ever seem strange that the gods just happen to hate all the same people you do? And think the same things are yucky that you do?

- What if the gods disagree? Greek mythology is full of gods

giving conflicting commands to humans.

- Is something wrong because the gods tell you it is, or do

they just tell you not to do it because it was wrong anyway?

If God hadn't told Cain not to kill Abel, would it have been

okay to do so?

μίασμα miasma.

Miasma, stain, defilement. A blood crime can leaves

behing a miasma a pollution that can stain a whole house or

city. In Oedipus Rex, for insance, Oedipus begins his

investigation into the former king's death because there is a

miasma over the city of Thebes. Even after a crime

seems to be over, the pollution remains.

So what we have during the era of the oikos and xenia

is a system that doesn't work.

πόλις polis.

City, city-state.The city provides institutions that

transcend the oikos, xenia, and echthra. The

household will endure, of course, but it will decrease in

relative importance. In the new system, my identity as a

citizen of the United States is more important than my

identity as a Magee. According to a Roman legend, the founder

of the Roman Republic, Brutus (the ancestor of the one we've

heard of) learned that his adult sons were conspiring to bring

back the exiled king. Brutus responded by killing them. This

shows that his first loyalty was to Rome, not to his familia.

δημοκρατία demokratia. Democracy. Aristotle roots his ethics in the polis, but different cities had different forms of government that called for different virtues. Under a monarchy, we would all be subjects to the ruler. And what do rulers expect from their subjects? Usually they value obedience as the most important characteristic of their loyal subjects. Hence the epithet 'loyal.' But in a democracy, the subject is replaced by a citizen. And citizens have a role in the government. As citizens, we aren't governed by rulers; therefore, we have to govern ourselves.

Δίκη

Dikē.

Justice in the oikos period had depended

well-armed relatives to extract their vengeance. Now Δίκη Dikē

works through the δίκαι dikai (plural of δίκη) of the

legal system of the polis. Now instead of angry uncles

and cousins lying in wait, we have a judge, a prosecutor, a

defense, and a jury of citizens. Justice has been transformed

by being transferred to the jurisdiction of the polis.

ἔθος ethos is a

neutral word originally meaning custom or habit — a habit

can be good or bad. It is the word Aristotle used to

describe the virtues he was teaching his pupils at his academia.

Whatever morality Greeks had had before was transformed in a

way similar to the way the idea of Justice had

changed. The realm of ethical behavior is the polis

rather than the oikos.

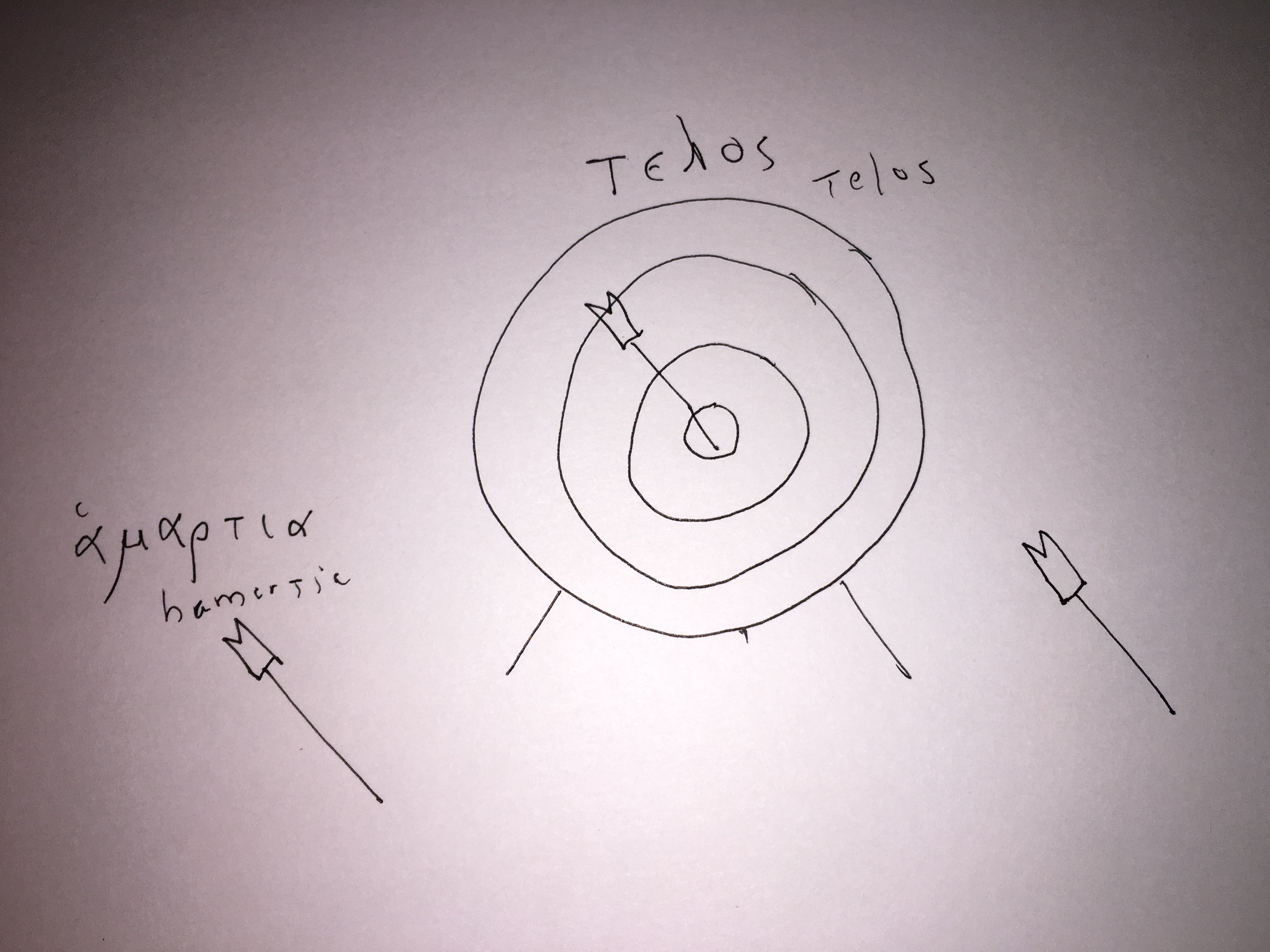

Ethics in Aristotle are teleological. In fact, all the

various components of his philosophy are teleological. A τέλος

telos is a goal or target.

The telos (goal) of ethos (ethics) is to

produce good citizens for the polis (city). Without

good citizens, the democratic polis will collapse. For

Aristotle, we learn these virtues through training, practice,

and patience. As you hit the mark (telos) more and

more, the virtue becomes part of your character. Of course, it

is inevitable that as you practice, you'll miss the mark.

Aristotle uses the term ἁμαρτία (harmatia)for missing

the telos. In the New Testament, the word ἁμαρτία is

usually translated 'sin.' Sin is marked by bad will, rebellion

against the will of God. This is NOT

Aristotle's definition. People don't miss the target on

purpose; they are doing the best they can with their talent

and skill. For the Bible, the way to deal with harmatia

is repentance and forgiveness. For Aristotle, it's more

practice. Another difference between the Bibile and Aristotle,

really all Greek philosophy, is the contrast between zealotry

and moderation. The Bible teaches its followers to believe in

one God and be completely devoted to him. Greek polytheism

requires us to serve all the gods enough. Serving any god too

much would keep us from giving other gods the τιμή (timē,

honor) that they demand. Greek polytheism naturally inclined

toward moderation.

Aristotle sees evil as a lack, inadequate goodness as it

were. The Biblical we can see evil as its own force. The book

of Proverbs (which is closer to Aristotle than most of the

rest of the Bible) talks about both forms of evil as two kinds

of ignorance.

- Ignorance as the lack of knowledge and wisdom. This can be

fixed by listening to your elders; in fact, the person with

this kind of ignorance is called "my child." This is the

kind of ignorance behind bad technical communication.

- Ignorance that actively opposes knowledge. It rejects

wisdom and experience out of hand. With correction, it only

becomes more ignorant. The person with this kind of

ignorance is called a fool. This kind of ignorance is behind

evil technical communication.

For Aristotle, the arrow being shot at the target can fall

short or go too far. So the citizen can have too much or too

little of any specific virtue. For instance, courage is an

important virtue. Too little courage is cowardice; too much is

rashness. In the Greek phalanx, the courageous stay with the

group. The coward runs away; the rash rushes ahead of the

others. Neither one helps the polis to victory. This

Aristotlean principle goes by several names:

- Via Media (the middle path)

- The Golden Mean

- The Goldilocks Principle

I believe that Aristotle's idea of moderation is a natural

outgrowth of the polytheistic religion of ancient Greece. In

order to give all the gods the worship they deserve, you could

not serve any too much or too little. This is in contrast to

the Biblical idea of zeal and total commitment.