Anthology of Louisiana Literature

Carl Bernhard, Duke of Saxe-Weimar Eisenach.

Travels through North America During the Years 1825 and

1826.

TRAVELS

THROUGH

NORTH AMERICA,

DURING THE

YEARS 1825 AND 1826.

BY HIS HIGHNESS

BERNHARD, DUKE OF SAXE-WEIMAR EISENACH.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

PHILADELPHIA:

CAREY, LEA & CAREY — CHESNUT STREET.

SOLD IN NEW YORK BY G. & C. CARVILL.

1828.

|

|

|

Prince

Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (1792-1862)

|

CHAPTER XI.

Journey to Philadelphia. — Stay in that place. — Bethlehem

and Nazareth.

Mr. J. R. Livingston, a very respectable citizen of New York,

whose country seat is at Massena, near Redhook, about a

hundred miles up the Hudson river, near the little town called

Hudson, invited me to visit him, and be present at a ball.

I accepted the invitation, especially as I was informed I

should find assembled there the best society, who generally

reside during the summer in the country.

The Grymes’ family, which arrived at New York not long after

me, were likewise of the party. Consequently we left New York

on the 5th of October, on board the safety-barge Lady Van

Rensselaer, for Albany. As Mr. Livingston had invited several

other persons of the best families of New York, who were all

on board, good conversation was not wanting. About half past

five we started, but did not long enjoy the beauties of this

noble river, as it soon became dark. During night we were

awakened with the unpleasant news that the leading boat had

run ashore in a fog. After five hours of useless exertion to

get her afloat, we were obliged to go on board the steam-boat

Henry Eckford, passing up the river. This boat was old, and no

longer used for conveying passengers, but as a tow-boat. She

had vessels attached to her, on both sides, laden with goods,

which gave her the appearance of a ferry-boat. Though not very

pleasantly situated on board of this boat, we had a good

opportunity of observing the magnificent banks of the river

after the fog disappeared. Instead of arriving at eight

o’clock, a. m.

we did not reach our place of destination till five o’clock p. m. We were

received by the owner, a gentleman seventy-six years old,

and his lovely daughter. The house is pleasantly situated on

an elevated spot in a rather neglected park. Our new

acquaintances mostly belonged to the Livingston family.

I was introduced to Mr. Edward Livingston, member of

congress, the brother of our entertainer, a gentleman,

who for talent and personal character, stands high in this

country. He resides in Louisiana, and is employed in preparing

a new criminal code for that state, which is much praised by

those who are acquainted with jurisprudence.

|

|

Edward Livingston

|

In the evening about eight o’clock, the company assembled at

the ball, which was animated, and the ladies elegantly

attired. They danced nothing but French contra-dances, for the

American ladies have so much modesty that they object to

waltzing. The ball continued until two o’clock in the morning.

I became acquainted at this ball with two young officers

from West Point, by the name of Bache, great grandsons of

Dr. Franklin. Their grandmother was the only daughter of

this worthy man; one is a lieutenant of the artillery at West

Point, and the other was educated in the same excellent

school, and obtained last year the first prize-medal; he was

then appointed lieutenant of the engineer corps, and second

professor of the science of engineering, under Professor

Douglass. On the following day we took a ride in spite of the

great heat, at which I was much astonished, as it was so late

in the season, to the country-seat of General Montgomery’s

widow, a lady eighty-two years of age, sister to the

elder Messrs. Livingstons. General Montgomery fell before

Quebec on the 31st of October, 1775. This worthy lady, at this

advanced age, is still in possession of her mental faculties;

her eyes were somewhat dim. Besides her place of residence,

which is handsomely situated on the Hudson river, she

possesses a good fortune. Adjoining the house is a small park

with handsome walks, and a natural waterfall of forty feet.

I observed in the house a portrait of General Montgomery,

besides a great number of family portraits, which the

Americans seem to value highly. According to this painting he

must have been a very handsome man. At four o’clock in the

afternoon we left our friendly landlord and embarked in the

steam-boat Olive Branch, belonging to the Livingston family

for New York, where we arrived next morning at six o’clock.

At Mr. Walsh’s I found a numerous assembly, mostly of

scientific and literary gentlemen. This assembly is called “Wistar Party;” it is

a small learned circle which owes its existence to a Quaker

physician, Dr. Wistar, who assembled all the literati and

public characters of Philadelphia at his house, every Saturday

evening, where all well-recommended foreigners were

introduced. After his death, the society was continued by his

friends, under the above title, with this difference, that

they now assemble alternately at the houses of the members.

The conversation generally relates to literary and scientific

topics. I unexpectedly met Mr. E. Livingston in this

assembly; I was also introduced to the mayor of the city,

Mr. Watson, as well as most of the gentlemen present, whose

interesting conversation afforded me much entertainment.

His excellency, John Quincy Adams, President of the United

States, had just returned from a visit to his aged and

venerable father near Boston, and took the room next to mine

in the Mansion-house. He had been invited to the Wistar-Party

on the 22d of October, at the house of Colonel Biddle, and

accepted the invitation to the gratification of all the

members. I also visited the party. The President is a man

about sixty years old, of rather short stature, with a bald

head, and of a very plain and worthy appearance. He speaks

little, but what he does speak is to the purpose. I must

confess that I seldom in my life felt so true and sincere a

reverence as at the moment when this honourable gentleman whom

eleven millions of people have thought worthy to elect as

their chief magistrate, shook hands with me. He made many

inquiries after his friends at Ghent, and particularly after

the family of Mr. Meulemeester. Unfortunately I could not long

converse with him, because every member of the party had

greater claims than myself. At the same time I made several

other new and interesting acquaintances, among others with a

Quaker, Mr. Wood, who had undertaken a tour through England,

France, Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Russia, mostly with the

philanthropic view of examining the prison discipline of those

countries. I was much gratified with his instructive

conversation, although I had some controversy with him on the

prison discipline, as he heard that I did not agree with his

views relative to the new penitentiary, of which he was one of

the most active promoters. Mr. Livingston, who has effected

the abolition of capital punishment in the state of Louisiana,

was here lauded to the skies by the philanthropists. God send

it success!

CHAPTER XIX.

Journey to New Orleans, and Residence in that City.

ON the 18th of January, we embarked in the schooner Emblem,

whose cabin was proportioned to her tonnage, (which was but

fifty tons,) but comfortably high, and well ornamented. The

sides were of mahogany and maple; on each side were two

staterooms, which two births each; the back part of the cabin,

being something higher than the forward part, contained a

birth on each side. Of these, the starboard was occupied by

Mr. Bowdoin, the other by myself.

The shores of Mobile Bay, which is very wide, are low and

overgrown with wood, before us lay a long island, called Isle

Dauphine, by the unfortunate Delasalle, who discovered it.

Mobile point lies to the left, where, after sunset, we beheld

the light in the light-house. There stood on this point in the

late war a small fort, called Fort Bowyer, which the present

Lieutenant- Colonel, then Major Lawrence, gallantly defended,

with a garrison of one hundred and thirty men, against eight

hundred disembarked English sailors and Seminole Indians,

under

Major

Nichols.

The assailants were defeated, after their

ordnance was dismounted, with considerable loss, and the

English corvette Hermes, which covered the

attack, was blown up by the well-directed fire of the fort. In

February, 1815, this brave officer found himself obliged to

yield to superior force, and to capitulate to Admiral

Cockburn, who was on his return from the unsuccessful

expedition to New Orleans. This was the last act of hostility

that occurred during that war. Fort Bowyer is since

demolished, and in its stead a more extensive fortress is

erecting, which we would willingly have inspected, had the

wind been more favourable, and brought us earlier. We steered

between Mobile Point and Dauphin Island, so as to reach the

Mexican gulf, and turning then to the right, southward of the

Sandy Islands, which laid along the coast, sailed towards Lake

Borgne. Scarcely were we at sea, when a strong wind rose from

the west which blew directly against us. We struggled nearly

the whole night to beat to windward, but in vain. The wind

changed to a gale, with rain, thunder, and lightning. The

main-topmast was carried away, and fell on deck. The mate was

injured by the helm striking him in the side, and was for a

time unfit for duty. On account of the great bustle on deck,

the passengers could hardly close an eye all night. The motion

of the cabin, so that the rain was admitted, and the furniture

was tossed about by the rolling.

On the morning of the 19th of January, we were driven back

to the strait between Dauphin Island and Mobile Point and the

anchor was dropt to prevent farther drifting. I was sea-sick,

but had the consolation that several passengers shared my

misfortune. The whole day continued disagreeable, cold, and

cloudy. As we lay not far from Dauphin Island, several of our

company went on shire, and brought back a few thrushes which

they had shot. I was too unwell to feel any desire of visiting

this inhospitable island, a mere strip of sand, bearing

nothing but everlasting pines. Upon it, strands some remains

of an old entrenchment and barrack. Besides the custom-house

officers, only three families live on the whole island. We saw

the light-house, and the houses at Mobile Point, not far from

us. I wished to have gone there to see the fortification

lately commenced, but it was too fat to go on a rough sea in a

skiff. On the 20th of January, the wind was more favourable;

it blew from the north-east, and dispersed the clouds, and we

set sail. After several delays, caused by striking on

sand-banks, we proceeded with a favourable wind, passed

Dauphin Island and the islands Petit Bois, Massacre, Horn, and

Ship Island.

These islands consist of high sand-hills, some of them

covered with pine, and remind one strongly of the coasts of

Holland and Flanders. Behind Horn and Massacre Islands lies a

bay, which is called Pascagoula, from a river rising in the

state of Mississipi, and emptying here into the sea. Ship

Island is about nine miles long, and it was here that the

English fleet which transported the troops sent on the

expedition agaist New Orleans, remained during the months of

December and January, 1814-15. At the considerable distance

from us to the left, were some scattered islands, called Les

Malheureux. Behind there were the islands De la Chandeleur,

and still farther La Clef du Francmacon. Afterwards we passed

a muddy shallow, upon which, luckily, we did not stick fast,

and arrived in the gulf Lac Borgne, which connects itself with

Lake Ponchartrain, lying back of it, by two communications,

each above a mile broad; of which one is called Chef Menteur,

and the other the Rigolets. Both are guarded by forts, the

first Coquilles, so called because it is built on a foundation

of muscle shells, and its walls are composed of a cement of

the same. We took this last direction, and passed the Rigolets

in the night with a fair wind. Night had already fallen when

we reached Lake Borgne. After we had passed the Rigolets in

the night, with a fair wind. Night had already fallen when we

reached Lake Borgne. After we have passed the Rigolets, we

arrived in Lake Ponchartrain, then turned left from the

light-house of Fort St. John, which protects the entrance of

the bayou of the same name, leading to New Orleans.

I awoke on the 21st of January, as we entered the bayou St.

John. This water is so broad, that we could not see the

northern shore. We remained at the entrance one hour, to give

the sailors a short rest, who had worked the whole night, and

whose duty it was now to tow the vessel to the city, six miles

distant. This fort, which has lost its importance since the

erection of Chef Menteur, and Petites Conquilles, is

abandoned, and a tavern is now building in its place. It lies

about five hundred paces distant from the sea, but on account

of the marshy banks cannot be thence attacked without great

difficulty. The bank is covered with thick beams, to make it

hold firm, which covering in this hot and damp climate

perishes very quickly. The causeway which runs along the

bayou, is of made earth on a foundation of timber. Behind the

fort is a public house, called Ponchartrain Hotel, which is

much frequented by persons from the city during summer. I

recognized the darling amusements of the inhabitants, in a

pharo and roulette table.

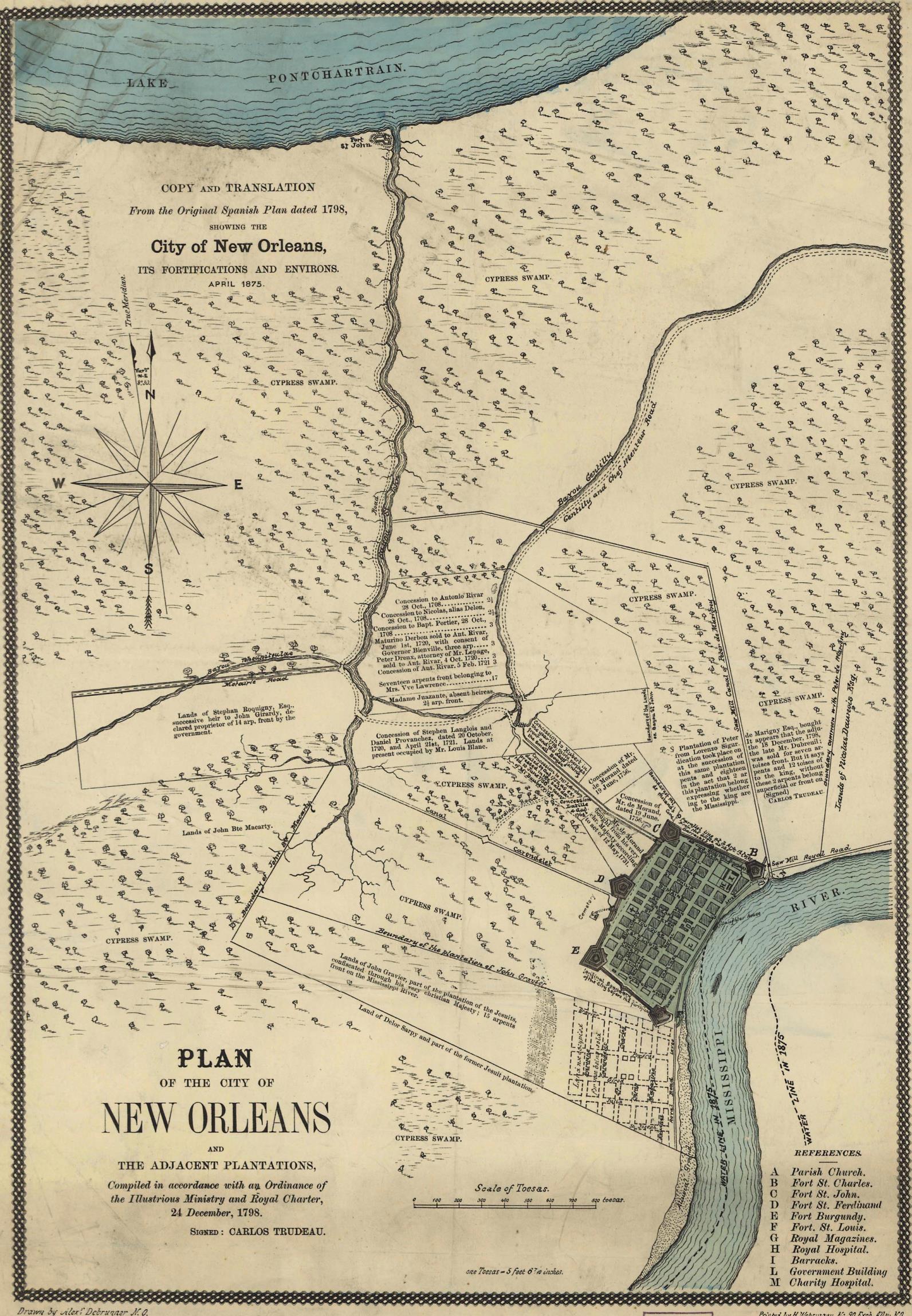

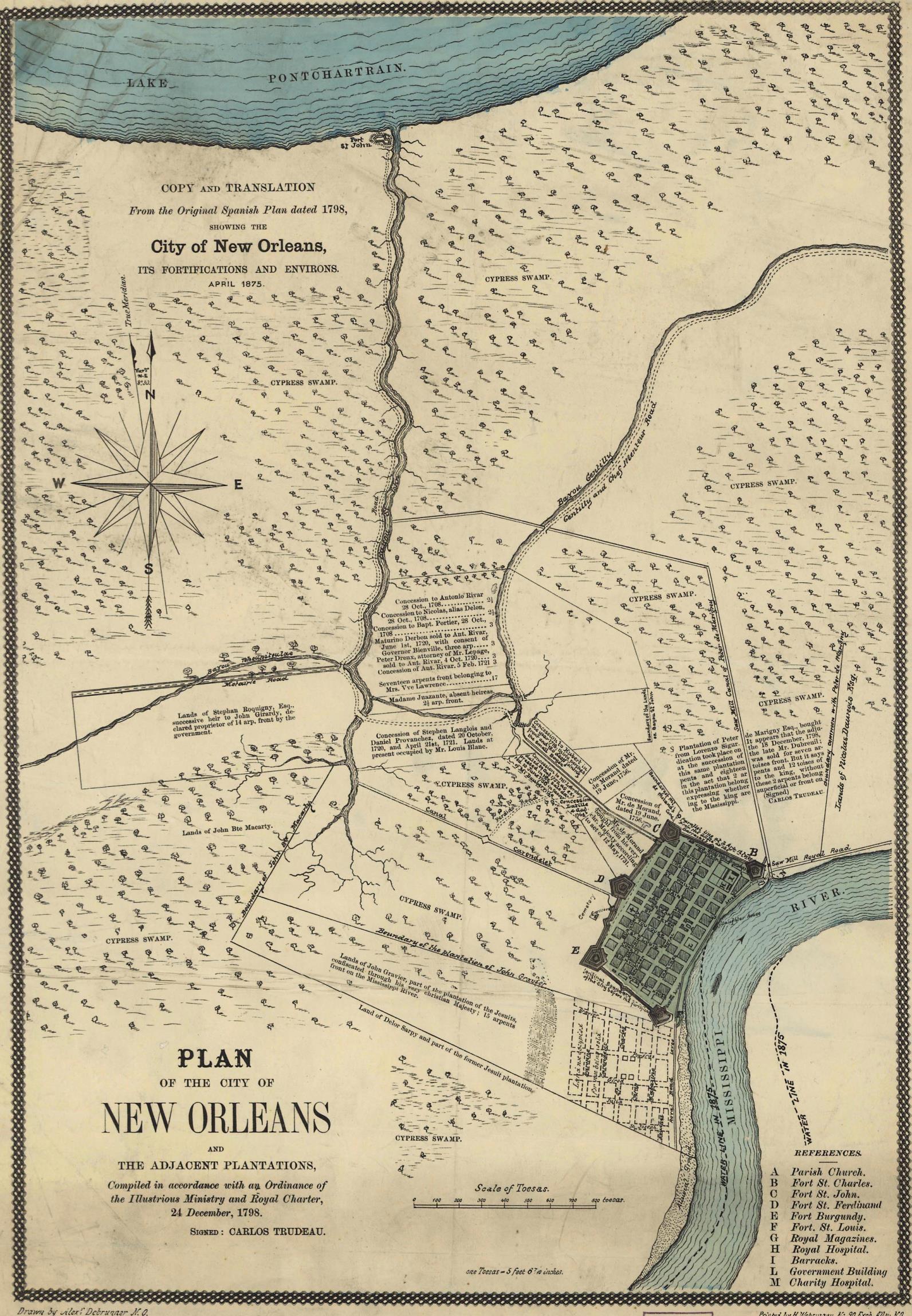

|

|

Map of New Orleans 1798.

|

As the passage hence to the city is very tedious in stages,

we proposed to hire a carriage, but there was none to be

found; six dollars was asked for a boat; we therefore, decided

to go on for. The Colonel, Mr. Huygens, Mr. Egbert, Mr. Chew,

and myself made up this walking party. The morning was

beautiful spring weather' we passed through a shocking marshy

country, along the right side of the bayou. The woods were

hanging full of the hateful Spanish moss, and a number of

palmettoes were the only variety afford. The causeway was very

muddy; there were good wooden bridges over little ditches,

which conveyed the water from the surrounding marshes into the

bayou.

After we have proceeded three miles in the manner, we came

into a cultivated district, passed a sort of gate, and found

ourselves quite in another world. Plantations, with handsome

buildings, fallowed in quick succession; noble live oaks,

which has been trimmed to regular shapes, young orange trees,

pride of China, and other tropical trees and bushes, along the

road. Several inns and public gardens were exhibited, for a

population that willingly seeks amusement. We noticed several

mansion-houses, ornamented with columns, piazzas, and covered

galleries; some of these were of ancient style in building. It

was naturally agreeable to me, after wandering a long time in

mere wildernesses, once more to come into a long civilized

country. We saw from afar, the white spires of the cathedral

of New Orleans, also the masts of the ships lying in the

Mississippi. The bayou unites itself, three miles from this

city, with a canal leading thither, which we passed upon a

turning bridge, to strike into the city by a nearer way.

This road carried us between well-built mansions, and over

the streets were hung reflecting lamps. The first view of the

city, as we reached, without knowing it, was really not

handsome; for we reached, without knowing it, war really not

handsome; for we came into the oldest section, which consisted

only of little one-story houses, with mud walls, and wide

projecting roofs. On the whole, the streets are regularly laid

out, part parallel with the river, the rest perpendicular to

it. The ancient town was surrounded by a wall, which is

destroyed, in its room there is a boulevard laid out, called

Rue de Remparts.

Next to the old town below, lies the suburb

Marigny, and above, that of St. Mary; then begins the most

elegant part of the city.

Before we searched for lodgings, we looked about a little

through the city, and went first to the Mississippi, to pay

our homage to this "father of rivers." It is about half a mile

wide, and must be above eighty fathoms deep; it is separated

from the city by a compost of muscle shells. This causeway

defends it from inundations. There are no wharves, they cannot

be fixed, as the river would sweep them away. The ships lay

four and five deep, in tiers along the bank, as in the Thames,

at London. Below them, were ten very large steam-boats,

employed in the river trade. In a line with the bank stood

houses, which were two or three stories high, and built of

brick, also ancient massive Spanish houses, known by their

heavy, solid style, and mostly white. We pass by a square, of

which the river formed one side, opposite stood the cathedral,

and on each side of it, a massive public edifice, with

areades. Along the bank stood the market-houses, built of

brick, modeled after the Propylae, in Athens, and divided into

separate blocks. We saw in these, fine pine-apples, oranges,

bananas, pecan-nuts, cocoa-nuts, and vegetables of different

descriptions; also several shops, in which coffee and oysters

were sold. The black population appeared very large; we were

informed, that above one-half of the inhabitants, forty-five

thousand in number, were of the darker colour. The

custom-house on the Levée, is a pretty building.

We met a merchant, Mr. Ogden, partner of Mr. William Nott,

to whose house I had letters, who had the politeness to take

charge of us, and assist us in out search for lodgings. We

obtained tolerable quarters in the boarding house of Madame

Herries, Rue de Chartes. The first person I encountered in

this house, was Count Vidus, with whom I had become aquainted

in New York and who since had travelled through Canada, the

western country, and down the Ohio and Mississippi.

My first excursion was to visit Mr. Grymes, who here

inhabits a large, massive, and splendidly furnished house. I

found only Mrs. Grymes at home, who after an exceedingly

fatiguing journey arrived here, and in fourteen days after had

given birth to a fine son. I found two elegantly arranged

rooms prepared for me, but I did not accept this hospitable

invitation. After some time Mr. Grymes came home, and

accompanied me back to my lodgings. As our schooner had not

yet arrived, we went to meet it and found it in the canal, a

mile and a half from town, where two cotton boats blocked up

the way. We had our baggage put into the skiff, and came with

it into the basin, where the canal terminates.

In the evening we paid our visit to the governor of the

state of Louisiana, Mr. Johnson, but did not find him

at home. After this we went to several coffee-houses, where

the lower class amused themselves, hearing are workman singing

in Spanish, which he accompanied with the guitar. Mr. Grymes

took me to the masked ball, which is held every evening during

the carnival at the French theatre. The saloon in which they

danced, was quit long, well planned, and adorned with large

mirrors. Round it were three rows of benches amphitheatrically

arranged. There were few masks, only a few dominos,

none in character. Cotillions and waltzes were the dances

performed. The dress of the ladies I observed to be very

elegant, but understood that most of those dancing did not

belong to the better class of society. There were several

adjoining rooms open, in which there is a supper when

subscription balls are given. In the ground floor of the

building are rooms, in which pharo and roulette are played.

These places were obscure, and resembled caverns: the company

playing there appeared from their dress, not to be of the best

description.

Next day, we made a new acquaintances, and renewed some old

ones. I remained in this city several weeks, for I was obliged

to give up my plan of visiting Mexico, as no stranger was

allowed to that country who was not a subject of such states

as had recognized the new government. There were too many

obstacles in my way, and therefore I determined to wait in New

Orleans for the mild season, and then to ascend the

Mississippi. The result was an extensive aquantance, a

succession of visits, a certain conformity in living, from

which one cannot refrain yielding to the city. No day passed

over this winder which did not produce something pleasant or

interesting, each day however, was nearly the same as its

predecessors. Dinners, evening parties, plays, masquerades,

and other amusements followed close on each other, and were

interrupted only by the little circumstances which accompany

life in this hemisphere, as well as in the other.

The cathedral in New Orleans is built in a dull and heavy

style of architecture externally, with a gable on which a

tower and two lateral cupolas are erected. The facade is so

confused, that I cannot pretend to describe it. Within, the

church resembles a village church in Flanders. The ceiling is

of wood, the pillars which support it, and divide the nave

into three aisles, are heavy, made of wood, covered with

plaster: as well as the walls, they are constructed without

taste. The three altars are distinguished by no remarkable

ornament. Upon one of the side altars strands an ugly wax

image of the virgin and child. Near the great altar is a

throne for the bishop. On Sundays and holy-days, this

cathedral is visited by beau monde; except on these

occasions, I found that most of the worshippers consisted only

of blacks, and coloured people, the chief part of them

females.

|

|

St. Louis Cathedral in 1838.

|

The sinking o of the Levée is guarded against in a peculiar

way. In Holland piles are driven in along the water for this

purpose, and geld together by watt ling. After the dam is

raised up, there are palisades of the same kind placed behind

each other. Here the twigs of the palmetto are inserted in the

ground close together, and their fan-like leaves form a wall,

which prevents the earth from rolling down.

There are only two streets paved in the city; but all have

brick side-walks. The paving stones are brought as ballast by

the ships from the northern states, and sell here very high.

Several sidewalks are also laid with broad flag stones. In the

carriage way of the streets there is a prodigious quantity of

mud. After a rain it is difficult even for a carriage to pass;

the walkers who to from one side to the other, have a severe

inconvenience before them; either they must make a long

digression, to find some stones that are placed in the abyss,

for the benefit of jumping over, or if they undertake to wade

through, run a risk of sticking fast.

Sunday is not observed with the puritanic strictness in New

Orleans, that it is in the North. The shops are open, and

there is singing and guitar playing in the streets. in New

York, or Philadelphia, such proceedings would be regarded as

outrageously indecent. On a Sunday we went for the first time,

to the French theatre, in which a play was performed every

Sunday and Thursday. The piece of this night, was the tragedy

of

Regulus,

and two vaudevilles. The dramatic corps was

merely

tolerable,

such as those of small French provincial

towns,

where they never presume to present tragedies, or

comedies of the highest class. "Regulus" was murdered; Mr.

Marchand and Madame Clozel, whose husband performed the comic

parts very well in the vaudevilles, alone distinguished

themselves. The saloon is not very large, but well ornamented;

below is the pit and parquet, a row of boxes each for four

persons, and before them a balcony. The boxes are not divided

by walls, but only separated by a low partition, so that the

ladies can exhibit themselves convenietly. Over the first row

of boxes is a second, to which the free colored people resort,

who are not admitted to any other part of the theatre, and

above this row is the gallary, in which slaves may go, with

the permission of their masters. Behind the boxes in a lobby,

where the gentlemen who do not wish to sit in a box, stand, or

or walk about, where they can see over the boxes. The theatre

was less attended, than we had supposed it would be; and it

was said, that the great shock felt in the commercial world,

on account of the bankruptcy of three of the

most distinguished houses, in consequence of unfortunate

speculations in cotton, and the failures in Liverpool, was the

cause of this desertion.

The garrison consists of two companies of infantry, of the

first and fourth regiments. This has been here since the last

insurrection

of

the negroes, and has been continued, to overawe them. In

case of serious alarm, this would prove but of little service!

and what security is there against such an alarm? The Chartres

streetm where we dwelt, there were two establishments, which

constantly revolt my feelings, to wit: shops in which negroes

were purchase and sold. These unfortunate beings, of both

sexes, stood or sat the whole day, in these shops, or in front

of them, to exhibit themselves, and wait for purchasers. The

abomination is shocking, and the barbarity and indifference,

produces by custom in white men, is indescribable.

There were subscription balls given in New Orleans, to which

the managers had the politeness to invite us. These balls took

place twice a week, Tuesdays and Fridays, at the French

theatre, where the masquerade had been, which I mentioned

before. None but a good society were admitted to these

subscription balls; the first that we attended was not

crowded, however, the generality of the ladies present were

very pretty , and had a very genteel French air. The dress was

extremely elegant, and after the latest Paris fashion. The

ladies danced, upon the whole, excellently, and did great

honour to their French teachers. Dancing, and some instruction

in music, is almost the whole education of the female creoles.

Most of the gentlemen here are far behind the ladies in

elegance. They did not remain long at the ball, but hasted

away to the quadroon ball ball, so called,

where they amused themselves more, and were more at their

ease. This was the reason why there were more ladies than

gentlemen present at the ball, and that many were onliged to

form "tapestry." When a lady is left sitting, she is said to

be "bredouillè."

Two cotillations and a waltz, are danced in succession, and

there is hardly an interval of two or three minutes between

the dances, The music was performed by negroes and coloured

people, and was pretty good. The governor was also at the

ball, and introduced me to several gentlemen, among others, a

Frenchman, General Garrigues de Flaugeac,

who, having emigrated from here from St. Domingo, had married,

and given the world some very handsome daughters. Several of

the French families here settled, and indeed, the most

respectable, were emigrants from that island, who wait for the

idemnification due to them, but without any great hope of

receiving it.

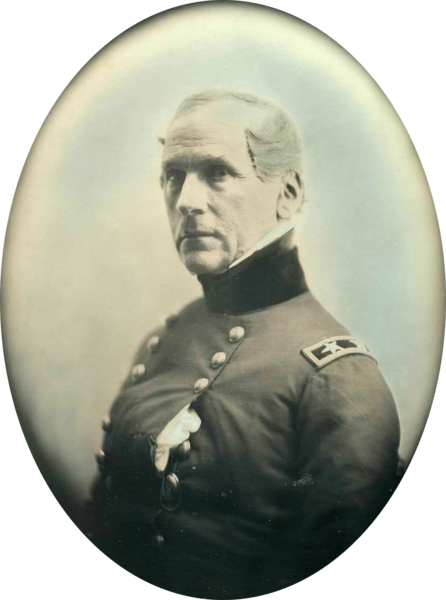

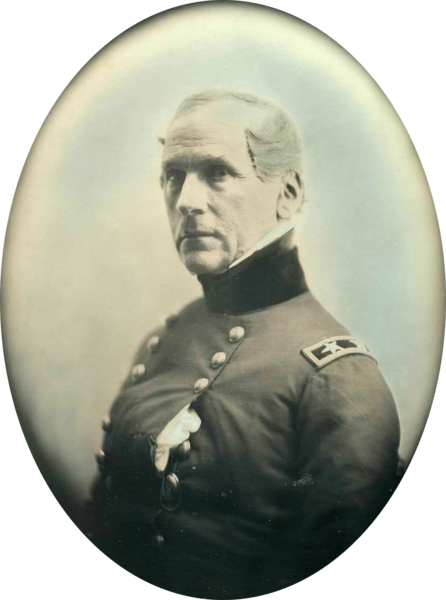

Colonel Wool inspected the two companies of the first

and fourth regiments, under Major Twiggs

stationed here; both together made at the most, eighty men under arms. The inspection took place before the Cathedral. I admired the good order and great propriety of these companies, as well as their uniformity of march and dressing, which I had no opportunity to observe before, in the 'troops' of the United States. There was indeed many things to be wished for; as for example, the coats of the men did not fit, and many were too short; the grey cloth pantaloons were of different shades, and much too short; no bayonet sheaths, nor gun straps; the belt intended for the bayonet sheath over that of the cartridge box: the privates had wooden flints in their guns, and none in their cartridge boxes, also no spare flints, files, screwdrivers, nor oil flasks. From the false maxim, that the second rank, if they are shorter men, cannot fire over the front, the lesser men are ranged in the first, and the taller in the second rank through the whole army of the United States, and this produces a great eye-sore. There was some manual exercise, and manœuvres in battalion training: all good. The soldiers were mostly young, handsome and strong men, well fed and healthy looking natives of the western states; there were some Germans and Irish among them. The Irish, however, since their conduct is often in nowise commendable, are no longer admitted. Governor Johnson remained during the review, which lasted above an hour or more; there were also several members of the legislature now assembling, present. I formed an acquaintance here with General La Coste, who formerly had been engaged in the Spanish service, and at present commanded a division of the Louisiana militia.

Colonel Croghan also attended the

review.

When the review was over, the governor showed me the two

extensive buildings joining the Cathedral, with arcades, as

before-mentioned. One of them is devoted to the use of the

several courts of jusice, and the other is the City Hall. In

the first, the United States court was holding its sessions,

and as it was rather cold, the judge had removed himself to

the fire-place, there to have the business transacted before

him. The suit in controversy related to the sale of a negro.

The buyer had purchased him as a slave for life; after the

bargain had been concluded, and payment made, he discovered,

by the declaration of his former masster, the seller, that at

a certain period he was to be free. I could not remain long

enough in the court, to wait for the decision.

John Ellis Wool

John Ellis Wool

We passed then to the City Hall. In the lower story, is the

guard-house of the city guard, besides a

prison

for runaways, or negroes punished by order of their masters,

who are here incarcerated, and employed in all servile labours

for the city; they are termed negres marrons. The

masters receive a daily recompense of twenty-five cents for

each imprisoned negro. Near the guard-house stands a small

piece of ordance, from which the signal tatoo is fired. After

this shot, no negro can tread the streets without a

without a

pass.

The upper stories of this building contains the

offices and court halls of the magistrates. Part of them were

ornamented very richly, as these chambers served as quarters

for General La Fayette, who was here in the month of April

last. Before the chambers, the whole length of the building,

ran a gallery with very large windows, which being raised in

summer, change the gallery into an airy balcony: an

arrangement which I had remarked to exist also in the other

buiding, where the courts of justice sat.

Hence the governor next conducted me to the old

Spanish government house, in which the senators and

representatives of the state of Louisiana were now assembled.

The building is ancient and crazy, otherwise situated in a

handsome spot on the Levée, surrounded by a balcony. There is

nothing more done for the repair of this building, as in a few

years the legislature will be removed to Donaldsonville. The

reason given for this is , that many members of the

legislature are plain people, who feel embarrased in New

Orleans, and hope to be more at their ease in Donaldsonville.

The office of the governor is in the yard, in a small house,

where the secretary of the Spanish governor formerly had his

office.

|

|

The Cabildo.

|

In a magazine belonging to the state, there are still several

articles which belonged to the former navy-yard, and which,

here-after, are to be sent to Pensacola. Among these, I

remarked brass and iron cannon of various calibres, and from

different countries, English, Spanish, and French. There were

some ancient ones among the French, with beautiful ornaments

and inscriptions. On one was, “ultima ratio regum;” on

others, the darling “liberté, egalité.”

These pieces were found in the trifting fortifications that

formerely surrounded the city, when the United States took

possession of Louisiana, in 1803.

During the last of January, it rained uncommonly hard and

steady. The streets became bottomless: holes formed in them,

where carriages and carts were in constant peril of upsetting.

At first it was cold; while the rain continued, there followed

such an oppressive heat, that it was feared an earthquake was

about to take place: it thundered and lightened also very

heavily.

At the masked balls, each paid a dollar for admission. As I

visited it for the second time, I observed, however, many

present by free tickets, and I was told that the company was

very much mixed. The unmasked ladies belonging to good

society, sat in the recesses of the windows, which were higher

than the saloon, and furnished with galleries. There were some

masks in character, but none worthy of remark. Two quarrels

took place, which commenced in the ball-room with blows, and

terminated in the vastibule, with pocket-pistols and kicking,

without any interuption from the police.

On the same evening, what was called a quadroon ball took

place. A quadroon is the child of a mestize mother and a white

father, as a mestize is the child of a mulatto mother and a

white father. The quadroons are almost entirely white: from

their skin no one would detect their origin; nay many of them

have as fair a complexion as many of the haughty creole

females. Such of them as frequent these balls are free.

Formerely they were known by their black hair and eyes, but at

present there are completely fair quadroon males and females.

Still, however, the strongest prejudice reigns against them on

account of their black blood, and the white ladies maintain,

or affect to maintain, the most violent aversion towards them.

Marriage between the white and coloured population is

forbidden by the law of the state. As the quadoons on their

part regard the negroes and mulattoes with contempt, and will

not mix them, so nothing remains for them but to be the

friends, as it is termed, of the white men. The female

quadroon looks upon such an engagement as matrimonial

contract, though it goes no farther than a formal contract by

which the "friend" engages to pay the father or mother of the

quadroon a specified sum. The quadroons both assume of the

name of their friends, and as I am assured preserve their

engagement with as much fidelity as ladies espoused at the

altar. Several of these girls have inherited property from

their fathers or friends, and possess handsome fortunes.

Notwithstanding this, their situation is always very

humiliating. They cannot drive through the streets in a

carriage, and their "friends" are forced to bring them in

their own conveyances after dark to the ball: they dare not

sit in the presence of white ladies, and cannot enter their

apartments without especially permission. The whites have the

privilege to procure these unfortunate creatures a whipping

like that inflicted on slaves, upon an accusation, proved by

two witnesses. Several of these females have enjoyed the

benefits of as careful an education as most of the whites;

they conduct themselves ordinarily with more propriety and

decorum, and confer more happiness on their "friends," than

many of the white ladies to their married lords. Still, the

white ladies constantly speak with the greatest contempt, and

even with animosity, of these unhappy and oppressed beings.

The strongest language of high nobility in the monarchies of

the old world, cannot be more haughty, overweening or

contemptuous towards their fellow creatures, than the

expressions of the creole females with regard to the

quadroons, in one of the much vaunted states of the free

Union. In fact, such comparison strikes the mind of a thinking

being very singularly! Many wealthy fathers, on account of the

existing prejudices send daughters of this description to

France, where these girls with a good education and property,

find no difficulty in forming a legitimate establishment. At

the quadroon ball, only coloured ladies are admitted, the men

of that caste, be it understand, are shut vulgarity, the price

of admission is fixed at two dollars, so that only persons of

the better class can appear there.

As a stranger in my situation should see every thing, to

acquire a knowledge of the habits, customs, opinions and

prejudices of the people he is among, therefore I accepted the

offer of some gentlemen who proposed to carry me to this

quadroon ball. And I must avow I found it much more decent

than the masked ball. The coloured ladies were under the eyes

of their mothers, they were well and gracefully dressed, and

conducted themselves with much propriety and modesty.

Cotillions and waltzes were danced, several of the ladies

performed elegantly. I did not remain long there that I might

not utterly destroy my standing in New Orleans, but returned

to the masked ball and took great care not to the white ladies

where I had been. I could nothowever refrain from making

comparisons, which in now wise redounded to the advantage of

the white assembly. As soon as I entered I found a state of formality.

At the end of January, a contagious disorder prevailed,

called the varioloid. It was said to be a species of

small-pox, and was described as malignant in the highest

degree. Even persons who had undergone vaccination, and those

who had passed through the natural small-pox, were attacked by

the disorder. The garrison were placed in the barracks to

preserve them from this malady. It was thought that it was

imported by some negro slaves from the north. Many owners of

slaves in the slave states of Maryland and Virginia have

real?(pardon the loathsome expression, I not how otherwise to

designate the beastly idea,) stud nurseries for slaves, whence

the planters of Louisiana, Mississippi, and the other southern

states draw their supplies which increase every day in price.

Such a disease as the varioloid is a fit present, in return

for

slaves thus obtained!

We paid the late governor of the stage, Mr.

Robinson, a visit. It gave me much pleasure to cultivate

his acquaintance. Mr. Robinson is regarded with universal

respect, and I meg in him a highly interesting and well

informed man, who converses with wit and spirit. At a dinner,

given by the acting governor, I became acquainted with the

former governor and militia general Villaret, as well as with

Dr. Herman, from Cassel, who was employed in the navy of the

United States as surgeon-general. From this dinner we went to

the child's ball, which was given in the customary ball room

if the French theatre, for the benefit of the dancing master.

Most of the children were white charming and danced very

prettily: only the little girls from ten to eleven years if

age, were dressed and tricked off like full grown ladies.

About eight o'clock the little children left off dancing and

were mostly sent home, and in their place the lather girls

resumed the dance. The costume of the ladies was very elegant.

To my discomfiture, however, a pair of tobacco-chewing

gentlemen engaged me in conversation, from which I received

such a sensation if disgust, that u was nearly in the

situation of one sea-sick.

On the 1st of February, to my great sorrow, the brave Colonel

Wool, who had become exceedingly dear and valuable to me, took

leave. I accomplished him to his steam-boat, which departed at

eleven o'clock, and gazed after him for a long time.

I paid a visit to the bishop of Louisiana, Mr. Dubourg, and was very politely received. He is a Jesuit, a native of St. Domingo, and appears to be about sixty years old. He delivers himself very well, and conversed with me concerning the disturbances in the diocese of Ghent, in the time of the Prince Broglio, in which he, as friend and counsellor of that prince, whom he accompanied in his progress through his diocese, took an active part. In his chamber, I saw a very fine portrait of Pope Pius VII. a copy of one painted by Camuccini, and given by the pope to the deceased duke of Saxe-Gotha. The bishop inhabited a quondam nunnery, the greater part of which he had assigned for, and established as a school for boys. The bishop returned my visit on the next day.

At a dinner, which Mr. Grymes gave with the greatest display

of magnificence, after the second course, large folding doors

opened and we beheld another dining room, in which stood a

table with the dessert. We withdrew from the first table, and

seated ourselves at the second, in the same order in which we

had partaken of the first. As the variety of wines began to

set the tongues of the guests at liberty, the ladies rose,

retired to another apartment, and resorted to music for

amusement. Some of the gentlemen remained with the bottle,

while others, among who I was one, followed the ladies, and

regaled ourselves with harmony. We had waltzing until ten

o’clock, when we went to the masquerade in the theatre of St.

Phillip’s street, a small building, in which, at other times,

Spanish dramas were exhibited. The female company consisted of

quadroons, who, however, were masked. Several of them

addressed me, and coquetted with me sometime, in the mist

subtle and amusing manner.

A young lawyer from Paris, of the name Souliez, paid me a

visit. He was involved in unpleasant circumstances in his

native country on account of some liberal publications which

he had made against the Jesuits in the newspapers. On this

account he, full of the liberal ideas, had left his home, and

gone to Hayti, with recommendatory letters from bishop

Gregoire to President Boyer. There, however, he found the

state of things widely different from what he had fancied them

at home. The consequence was he had come to the United States,

and he now candidly confessed that he was completely cured of

his fine dreams of liberty.

Dr. Herman gave a dinner at which were more than twenty

guests. Among them were the governor, Colonel Croghan, and

several of the public characters here. Mr. Bowdoin, who was

slowly recovering from his gout, and Count Vidya, were also

there. Except our hostess there was no lady unwell, and

obliged to leave the table soon. The dinner was very splendid.

I paid a visit to the bishop of Louisiana,

Mr.

Dubourg,

and was very politely received. He is a Jesuit,

a native of St. Domingo, and appears to be about such heads

old. He delivers himself very well, and conversed with me

concerning the disturbances in the diocese I'd Ghent, in the

time if the Prince Broglio, in which he, as friend and

counselor of that prince, whom he accompanied in his progress

through his diocese, took an active part. In his chamber, I

saw a very fine portrait is Pope Pius VII. a copy of one

painted by Canuccini, and given by the pope to the deceased

duke if Saxed-Gotha. The bishop inhabited a quondam nunnery,

the greater part of which he had assigned for, and established

as a school for boys. The bishop returned my visit on the next

day.

We crossed the Mississippi in a boat, like a small chest,

such a boat is styled a "ferry-boat." This was the only stated

means if communication supported between the city and the

right bank. Formerly there was a steam ferry-boat, and

afterwards a horse-boat, but neither the one nor the other

could be supported by the business. The stream is nearly

three-fourths of a mile broad. Arrived in the right back, we

found a little inconsiderable place called Macdonaldville,

that did not appear very thriving. Kng the bank runs a

levée, to protect the land from inundation. Several

vessel safe laid up here. The country is exceedingly level,

and is composed of swampy meadows, and in the back ground, of

forest, partly of live oaks, which is much concealed, however,

by long hgly miss. Farther inward is a sugar plantations

belonging to Baron Marigny. The rivet makes a remarkable bend

opposite New Orleans, and the city, with its white spires, and

crowds of vessels lying in the stream, looks uncommonly well

from the right bank.

General Villaret invited us to dinner at his country-house,

which is eight miles distant from New Orleans, and had the

politeness to bring us in his carriage. At half past eleven

o'clock, I sent out with Count Vidua, and Mr. Huygens. The

habitation, as the mansion-houses lying in sugar plantation

are termed, Is upon the left back of the Mississippi, about a

short mile from the river. In December, 1814, it served the

English army for headquarters. The road to it led along the

levée, past country houses, which succeeded each other

rapidly for five miles. Devaluation display the comfort and

good taste of their owners. The mansion-house, commonly, is

situated about one hundred paces from the entrance, and an

avenue if laurel trees, which are cut in a pyramidical form,

and pride of China trees, leads to the door. The most of these

houses are two stories high, and are surrounded with piazzas

and covered galleries. Back if the elegant mansion-house stand

the negrk cabins, like a camp, and behind the sugarcane

fields, which extend to the marshy cypress woods about a mile

back, called the cypress swamp. Among these country-houses is

a nunnery of Ursulines, the inhabitants of which the employed

in the education of female youth.

The Battle of New Orleans.

The Battle of New Orleans.

Five miles from the city we reached the former plantation of

M'Carthy, now belonging to Me. Montgomery, in whichever

General Jackson had his head quarters. About one hundred laces

father, commences the right if the line, to the defense of

which this general owes great renown. I left the carriage

here, and went along the remainder of the line, at most a mile

in length, with the right wing in the rivet, and the left

resting on the cypress swamp.

The English landed in Lake Borgne, which is about three miles

distant from General Villaret's dwelling. On the 23d of

December, a company of soldiers attacked this house, and took

two if the general's sons prisoners. The third of his sons

escaped, and brought to General Jackson, whose headquarters

were at the time in the city, the intelligence of the landing

and progress of the British. Immediately the alarm guns were

fired, and the general marched with the few troops and militia

under his command, not two thousand in number, against the

habitation of Villaret. The English had established themselves

here, with the intent to attack the city directly, which was

without the least protection. The general advanced along the

line of the woods, and neatly surprised the English. He would

probably have captured them, if he had had time to despatch a

few riflemen through the generally passable cypress swamp to

the right wing: and had not the night come on, and a sudden

fog also prevented it. He judged it more prudent to fall back,

and stationed his troops at the narrowest point between the

river and the cypress swamp, while he took up his headquarters

in the habitation of M'Carthy.

There was a small ditch in front of his line, and on the next

day some young men of the militias commenced on their own

motion to throw up a little breast-work, with the spades and

shovels they found in the habitation. This suggested to the

general the idea of forming a line here. This line was,

however, the very feeblest an engineer could have devised,

that is, a strait one. There was not sufficient earth to

make the breast work of the requisite height and strength,

since, if the ground gets was dig two feet, water flowed out.

To remedy this evil in some measure, a number of cotton bales

were brought from the ware-houses if the city, and the

breast-work was strengthened by them. Behind these bales artillery

was placed, mostly ship's cannon, and they endeavored, by a

redoubt erected on the right wing at the levée, to

render if more susceptible of defense; especially as no time

was to be lost, and the offensive operations of the British

were daily perceptible; still the defensive preparations with

general Jackson could effect were very imperfect. The English

force strengthened itself constantly, they threw up batteries,

widened the canal leading from Villaret's to Lake Borgne, so

as to admit their boats into the Mississippi, and covered

this canal by several detached entrenchments.

A cannonade was maintained by their batteries did several

days on the American line, but they could not reach it, and

had several of their own pieces dismounted by the

well-directed fire of the American artillery. Finally, on the

8th of January, after General Jackson had time to procure

reinforcements, of which the best were the volunteer riflemen

of Tennessee, who were distributed along the line, well

covered by the cotton bales, and each of which had one or two

men behind him, to load the rifles, the English commenced

storming the line, under Sir Edward Packenham's personal

direction. The should in front of the line consisted of

perfectly leveled sugar cane fields, which had been cut down,

not a single tree or bush was to be found. The unfortunate

Englishmen, whose force in the field was reckoned at from

eight to ten thousand men, were obliged to advance without ant

shelter, and remain a long time, first under fire of

well-directed cannon, afterwards under the fire of rifles and

small arms of the Americans, without being able to effect

anything in return against them. The first attack was made

upon the left wing of the line. The British did not reach the

ditch, but began soon to give way. Sir Edward attempted to

lead them on again; cannon shot, however, killed his horse and

wounded him in both his legs. The soldiers carried him off,

but he unluckily received some rifle shots, that put an end to

his life, having five balls in his body. The Major-generals

Gibbs and Keane were struck at the same time, the first killed

and latter mortally wounded. By this the troops, ago had

continually supported a most murderous fire, were at length

obliged completely to give way. Major-general Lambert, who

commanded the reserve, and upon whom also at the period the

whole command of the army devolved, made a last ability to

force the line. He led this troops in a run upon the batture,

between the levée and the river, (which at the time was

very low,) against the right wing of the line, where the small

redoubt was placed, stormed, and took possession of if, but

was forced, by the well-supported fire of the riflemen behind

the line, to evacuate it again. The English colones of

engineers, Rennee, met with a glorious death, upon the

breast-work, in this affair. After this unsuccessful attempt,

the English retreated to their entrenchments at Villaret's,

and in a few days re-embarked.

During the failure of this principal attack, the English had

conveyed right hundred men to their right shore of the river,

who gained some advantages there against insignificant

entrenchments. These advantages, when they heard of the bad

results if the main attack, they were obliged to abandon, and to

return to the left bank. Had the storm of the right wing, and

the feigned assault on the left been successful, in all

probability General Jackson would have been obliged to

evacuate not only his lines, but the city itself. Providence

surely took the city under its protection; for the English

were promised the plunder of New Orleans in case of success,

as was asserted in that city: General Jackson moreover had

given orders, in case of his retreat, not only to blow up the

powder magazine of the city on the right bank, but to destroy

the public buildings, and set the city on fire at the four

corners. The general himself so fully recognized the hand of

Providence in the event, that in the day after his victory, he

expressed himself to Bishop Dubourg thus: that he knew the

city owed its preservation to a merciful Providence alone,

and that his first step should be on his return to the city,

to thank God in his temple did the victory so wonderfully

obtained. The bishop immediately gave directions did a

thanksgiving, and it was unanimously celebrated with a sincere

feeling of gratitude.

From the battle ground to General Villaret's dwelling, we had

three miles still to go over. For some days back, we had dry

weather, and the road, which after a hard rain, must be

bottomless, was on that account, hard and good. The

Mississippi has a peculiarity possessed by several streams in

Holland, of changing its bed. The house of General Villaret,

was once much nearer the river; for some years, however, it

had inclined so much to the right, that it constantly wears

away the soils there, while it forms new deposits to the left.

The general's possessions are therefrom increased, and that

with very good soil. The visit of the English nearly ruined

the general. Their landing on this side was so entirely

unexpected, that he, being employed in collecting the militia

in the districts above the city, had not been able to remove

the least of his property. The English took all the cattle

away, as well as above sixty negroes. There has not been any

intelligence of what was the fate of negroes, probably they

were sold in the West Indies. All the fences, bridges, and

negro cabins were destroyed. The mansion-house was only

spared, as it was occupied as head-quarters. The youngest son

of the general, between thirteen and fourteen years old, was

obliged to remain in the house the whole home it was retained,

and was very well treated by the English generals and

officers. As the English were on the living of re-embarking,

General Lambert gave young Villaret four hundred dollars in

silver to carry to his father, as indemnification for the

cattle carried off. The young man went to the city and

delivered the money to his father. General Villaret requested

General Jackson to send a flag to truce on board the English

fleet, to carry the money back to General Lambert, with a

letter from General Villaret. This was done, but the general

never received an answer.

The removal of the negroes was a severe stroke for the

General, from which, as he told me himself, it cost him much

trouble gradually to recover. The canal or bayou, which ran

from his plantation to Lake Borgue, was shut up by order, of

General Jackson after the retreat of the English, and there

were not labourers sufficient left with General Villaret to

reinstate it; it was of great importance to him for the

conveyance of wood and other necessaries.

We found at the general's, his sons, his son-in-law, Mr.

Lavoisne, and several gentlemen from the city, among them

Governor Johnson. We took some walks in the adjacent grounds.

The house was not very large, and was not very much

ornamented, for reasons already mentioned. Behind it was a

brick sugar-boiling house, and another one for the sugar mill.

Near that was a large yard, with stables and neat negro cabins

for the house-servants. The huts of the field slaves were

removed farther off. The whole is surrounded by cane fields,

of which some were then brought in, and others all cut down. A

field of this description must rest fallow for five years, and

be manured, before being again set out in plants. For manure,

a large species of bean is sown, which is left to rot in the

field, and answers the purpose very well. The cane is commonly

cut in December, and brought to the mill. These mills consists

of three iron cylinders, which stand upright, the centre on of

which is put in motion, by a horse-mill underneath, so as to

turn the other by crown-wheels. The cane is shoved in between

these, and must pass twice through to be thoroughly squeezed

out. The fresh juice thus pressed out, runs through a groove

into a reservoir. From this it is drawn off into the kettles,

in which it is boiled, to expel the watery part by

evaporation. There are three of these kettles close together,

so as to pour the juice when it boils from one to the other,

and thus faciliate the evaporation of the water. The boiling

in these kettles lasts one hour; one set gives half a hogshead

of brown sugar. In several of the plantations there is a steam

engine employed in place of the horse power:the general's

misfortunes have not yet permitted him to incur this expense.

After dinner we walked in the yard, where we remarked several

Guinea fowls, which are common here, a pair of Mexican

pheasants, and a tame fawn. Before the house stood a number of

lofty nut tress, called peccan tress. At the foot of one, Sir

Edward Packenham's bowels are interred: his body was embalmed

and sent to England. In the fields there are numbers of

English buried, and a place was shown to me where forty

officers alone were laid. We took leave of our friendly host

at sundown, and returned to the city.

On

Shrove Tuesday,

all the ball rooms in the city were

opened. I went to the great masked ball in the French theatre.

The price of admission was raissed to two dollars for a

gentleman, and one dollar for a lady. There was dancing, not

only in the ball room, but also in the theatre itself, and on

this occasion, the

parterre

was raised to a level with the

stage. The illumination of the house was very good, and

presented a handsome view. Many of the ladies were in masks

and intrigued as well as they were able. I could not restrain

my curiosity, and visited the quadroom ball in the theatre of

St. Philippe. It however was too late when I arrived there,

many of the ladies had left the ball, and the gentlemen, a

motly society, were for the most part drunk. This being the

case, I returned after a quarter of an hour to the principal

ball. But here too, some gentlemen had slipped too deep in the

glass, and several quarrels with fists and canes took place.

The police is not strict enough here to prvent gentlemen from

bring canes with them to balls. The balls continue through

lent, when they were but little frequented.

On the 12th of February the intelligence of the death of the

Emperor Alexander was spread abroad, which had been recieved

by the ship Mogul, yesterday arrived from Liverpool, and by

London gazettes of the 24th of December. I could not believe

this to be a fact, and betook myself to the office of one of

the public papers. I was here given the English gazette to

read, and I found, to my no small terror, the detailed account

of this sorrowful event. Consternation entered into my mind,

on refecting what effect this must have produced in Weimar,

and increased my troubled state of feeling!

The volunteer battalion of artillery of this place is a

handsome corps, uniformed as the artillery of the old French

guard. It is above one hundred men strong, and presents a very

military front. This corps maneuvered about half an hour in

the square before the cathedral, and then marched to the City

Hall, to recieve a standard. Upon the right wing of the

battalion, a detachment of flying artillery was placed. The

corps had done essential service on the 8th of January, 1815,

in the defence of the line, and stands here in high respect.

About four miles below the city Mr. Grymes has a

country-seat, or habitation. The house is entirely new, and

situated on a piece of ground formerly employed as a sugar

cane field. The new plantings made in the garden, consisted of

young orange tress and magnolias. Behind the house is an

artificial hill, with a temple upon it, and within the hill

itself, a grotto, arranged artifically with shells. At the the

entrance stands a banana tree, and this, with several creeping

plants, will conceal it very well in summer. I observed in the

garden several singular heaps of carth, which are hollow

within, and stand over a hole in the ground. They are said to

be formed by a species of land crab for their residence. If a

stone be thrown into the hole, you hear that it immediately

falls into water. Generally, in this country, you cannot dig

more than a foot deep in the earth, without meeting water.

It was pure curiosity that carried me a third time to the

masquerade, in St. Philippe's theatre. It was, however, no

more agreeable than the one eight days previous. There were

but few masks; and among the tobacco-chewing gentry, several

Spanish visages slipped about, who carried sword-canes, and

seemed to have no good design in carrying them. Some of these

visiters were intoxicated, and there appeared a willing

disposition for disturbance. The whole aspect was that of a

den of ruffians. I did not remain here a half hour, and

learned next day that I was judicious in going home early, as

later, battle with canes and dirks had taken place. Twenty

persons were more or less dangerously wounded!

It rained very frequently during the first half of the month

of February; in the middle it was warm, and for a time, about

the 20th, an oppressive heat prevailed, which made me quite

lethargic, and operated equally unpleasantly on every one.

Indeed a real sirocco blew at this time. It surprised me very

much, that with such extraordinary weather, not at all

uncommon here, that there should be so many handsome, healthy,

and robust children. This climate, so unhealthy, and almost

mortal to strangers, seems to produce no injurious effect upon

the children born here.

In the vacant space, where the walls of New Orleans formerly

stood, are at present the Esplanade rue des Remparts, and rue

du canal. The city proper forms a parallelogram, and was once

surrounded by a palisade and a ditch. At each of the four

corners stood a redoubt. The last of these redoubts, which

stood at the entrance of the Fauxbourg Marigny, was demolished

only since the last war. It would be important for the

security of the present inhabitants, to have a fortress on the

bank of the river, so that in case of an insurrection of the

negroes, not only the trifling garrison, but the white women

and children should possess a place of refuge, which is now

totally wanting. The ditch is filled up, and planted with

trees; there no buildings newly erected here, and these open

spaces are the worst parts of the city.

On the night of the 22d of Febrary, the alarm bell was

sounded: a fire had broken out in the warehouse of a merchant.

There was time to save every thing, even the wooden building

was not consumed, but in the course of two hours the fire was

extinguished.

On the same day, we celebrated the birth of the great

Washington. All the vessels lying in the river were adorned

with flags, and fired salutes. The volunteer legion of

Louisiana was called out in full uniform, to fire volleys in

honour of the day. The artillery before mentioned, which gave

thirteen discharges from two pieces, distinguished themselves

again by their excellent discipline. The infantry was very

weak, not exceeding fifty men, with a most monstrous standard.

A company of riflemen of thirty men, who had sone good service

on the 8th of January, 1815, appeared very singular in their

costume: it consisted of a skyblue frock and pantaloons, with

white fringe and borders, and fur hoods. This legion was

established in the last war, and considering itself

independent of the militia, it has clothed itself after the

French taste, and is officered by Frenchmen.

In the evening there was a subscription ball, in the

ball-room of the French theatre. This ball was given also, on

account of the festival celebrated this day. In former years,

each person had subscribed ten dollars for this ball; the

saloon had been decorated with Washington's portrait, and a

number of standards, and a splendid supper spread for the

ladies. This year the subscription had been reduced to three

dollars for a ticket, and hardly filled up at that price. It

was attempted to be accounted for, by the critical juncture of

commercial affairs, in which the city placed; the true cause,

however, might be traced to the imcomprehensible want of

attachment among the creoles to the United States. Although

the city of New Orleans, and the whole state of Louisiana, has

benefited extremely by its union with the United States and

daily increases; yet the creoles appear rather to wish their

country should be a French colony, than annexed to the Union.

From their conversations, one would conclude that they do not

regard the Americans as their countrymen. This aversion

certainly will lessen, as the better part of the young people

acquire their scientific education in the northern states; at

this moment, however, it is very powerful. Under this state of

things, Mr. Davis, the manager of the French theatre, the

balls, and several gaming houses, announced a masked ball, at

one dollar admission, for Washington's birth-night. The young

ladies, however, to whom a subscription ball was in

anticipation, and on account of it had prepared a fresh set of

ornaments, to assist their toliet, felt themselves exceedingly

dissapointed by this arrangement; as there would be a very

mixed company at the masked ball, and they would not be able

to distinguish themselves by individual ornament. For this

reason, their parents and relations had exerted themselves,

and happily brought it to pass, that instead of a ticket ball,

there shoud be one by sucscription. In fact, this ball was

very splendid, so far as the dress of the ladies contributed

there to. Moreover, no battles took place.

In the neighbourhood of the city, some Choctaw Indians

hunted, and lived a wandering life. They frequently resorted

to the city to sell the produce of their hunting, also canes,

palmetto baskets, and many other articles. The money for these

was afterwards consumed in liquor. They are of very dark

colour, have coats made of woollen blankets; wear mocassins,

and undressed leather leggings, necklaces of checkered glass

beads, with a large shell in the form of a collar, silver

rings in the nose and ears, and smooth copper rings on the

wrists. The children until four years old are quite naked;

only wearing mocassins, leggings, and the rings round the

wrists.

In a tavern on the Levée, there was a collection of fossil

bones, which had been dug out of a swamp, not far from the

mouth of the Mississippi, the preceding year, and must have

have belonged to a colossal amphibious animal. The single

piece of the spine remaining appeared to be that of a whale: a

single rib however, also found, was too much curved ever to

have been the rib of a whale. The largest piece of those that

were dug up, appeared to be a jaw bone. Unfortunately I

understand too little of these things, to be able to venture

upon a description of these remarkable remains of an

apparently antideluvian animal; certainly it would be worth

the trouble of having them examined and described by a

scientific person. Two of the bones appeared to have belonged

to the legs, and from these alone, some would determine, that

the animal was a crocodile. I was informed at this time--I

say, with Herodotus, that I only now what others have told

me, and perhaps some may either believe it, or know it,--I was

told that a perfect skeleton of a mammoth was collected years

ago in one of the meadows, on the banks of the Mississippi, not

far from its mouth, and was conveyed to London, and that very

old inhabitants had heard as a tradion from their ancestors,

that this mammoth had been thrown ashore by the sea, part

rotted, and in part was devoured by the buzzards.

There is no particular market day in New Orleans, as in other

places, but every morning market is open for all kinds of

vegatables, fruits, game, &c. This market is very well

provided on Sunday, as the slaves have permisssion to offer

for sale on this day all they desire to dispose of.

I visited Captain Harney of the first regiment of infantry,

who in the year 1825, as lieutenant to General Atkinson; had

accompanied the expedition to Yellow Stone river, and had

brought back with him several of the curiosities of those

western regions, so little known. These curiosities consisted

of a variety of skins of bears, for example, of the grizzled

bear, also skins of buffalo, foxes, of a white wolf, (which is

a great rarity,) of a porcupine,

whose quills are much shorter than those of the African

species, and of wild cats. Besides these, Mr Harney has

procured pieces of Indian habiliments, coats and leggings made

of deer skin. The warriors among these Indians wear the mark

of their dignity — the scalps — on the leggings, those of the

inferior grade on one leg, those higher, on both. The coats

are made with a checkered sewing, ornamented partly with glass

beads, and partly with split porcupine quills. The Indian

women, who are designated by the universal name of squaw, work

these ornaments very ingeniously. Mr. Harney showed me also a

quiver made of cougar's skin with different sorts of arrows, a

bow of elk's horn, strung with tendons drawn from the elk;

several tobacco pipes, with heads of serpentine stone, of

which I had seen some on Lake Ontario already, hunting

pouches, a head dress of eagle's feathers for the great chief

of the Crow nation, a set of the claws of the grizzled bear,

which also were worn for ornament, and a tomahawk of flint

with a variety of bunches of human hair: for every time a

warrior has killed his enemy with his tomahawk, he fastens a

bunch of his hair, with a piece of the scalp on his weapon. He

farther showed me a pipe made of a sheep's rib, adorned with

glass beads, upon which the Indians blow all the time they are

engaged in a fight, as as not to loose themselves in the

woods; a spoon made of the horn of a wild mountain ram;

various minerals, and among them petrified wood, which is

found in great quantities in that western region; serpentine,

and other curiosities. The coats of the squaws are trimmed

with long thin strips of leather, on one of these a bunch of

yellow moss and grass was tied, which the Indians regard as a

sort of amulet or talisman.

On the 28th of February, in the forenoon, I went with Mr.

Huygens to pay General Villaret a visit at his country-house.

A pretty strong west wind moderated the great heat outside of

the city; within it, the thermometer of Fahrenheit had stood

at eighty-one degress in the shade. Most of the fruit trees

were in blossom. Every where we saw fresh green and bloom; all

was fresh and lively. In a sugar-cane field, there were oats a

foot and a half high, cut as green fodder. The general and his

son were occupied in managing the labours of the field. We

went with them to walk in the garden. The soil is very

fruitful, that, however, is the most so, which is reclaimed

from the swamp of the Mississippi, or the Bayou. In this soil,

nevertheless the germ of a real land plague, the coco, as it

is called, shows itself, the same which was made use of on the

continent of Europe, as a substitue for coffee, during the

existence of the vexatious continental system. This knotty

growth is principally found in the mud; and one lump or knot

of it multiplies itself so extremely quick, that it kills all

the plants growing near it, and covers the whole field, in

which it has taken root. It is very difficult to extirpate,

since the smallest knot, that remains in the earth, serves for

the root of a new plant, and several hundred new knots. The

legislature of Louisiana, has offered a considerable reward to

whoever shall succeed in the discovery of an efficient remedy

against this pest of the soil. No one has yet obtained the

desired object.

The general explained to me, the manner in which the

sugarcane fields were managed. Parallel furrows are made

through them at intervals of three feet. In these furrows, the

cane is laid lengthwise, and covered with earth. Some planters

lay two cane joints together, others content themselves with

but one. The end of the successive piece of cane, is so placed,

that it lies about six inches above the end of the first. From

each joint of the cane, there shoot up new sprouts, and form

new stalks. In St. Domingo, there is another method of

arranging the cane field. The field is digged in square holes,

placed checkerwise at the distance of three feet apart, in

which four pieces of cane are laid in the square and then

covered up. This method is judged the best.

The tragedy of Marie Stuart by Le Brun from Schiller, and a

vaudeville, la Demoiselle et la Dame, were produced at the

theatre, to which I went. The first piece was announced at the

request of several American families, of course there were

numbers of ladies of that nation in the boxes. The tragedy of

Le Brun is changed very little from that by Schiller; it is

only curtailed, and two parts, those of Shrewsbury and

Mellvil, are thrown into one. Many scenes in it particularly

the meeting of the two queens, is translated almost word for

word. Madam Clozel undertook the part of Marie Stuart, and