Pisatuntema.

David I. Bushnell, Jr.

Myths of the Louisiana Choctaw.

Contents

II.

III.

IV. Okwa Falama, The ‘Returning Water,’ or Flood

V

Nalusa Falaya, or The Long Evil Being

Hashok Okwa Hui’ga

How The Snakes Aquired Their Poison

Turtle and Turkey

Turtle, Turkey, and the Ants

Raccoon and Opossum

The Geese, the Ducks, and Water

A FEW

miles north of Lake Pontchartrain, in St Tammany

parish, Louisiana, are living at the present time some ten

or twelve Choctaw, the last of the once numerous branch

of the tribe that formerly occupied that section. They are living

not far from Bayou Lacomb, near one of their early settlements

known in their language as Butchu’wa or “Squeezing,” probably

from the narrowing of the bayou at that point.

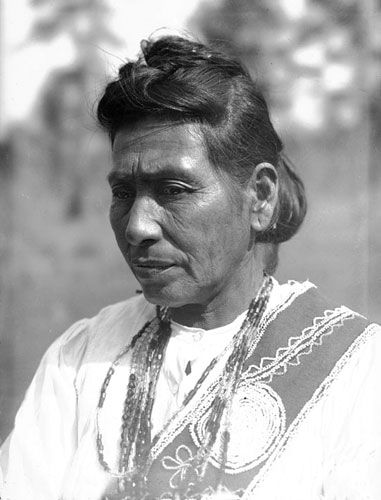

The oldest member of this small band is a woman, Pisatuntema, She is about fifty years of age, the daughter of one of the principal men of the last generation, who, at the time of his death some years ago, was recognized as a chief. From her father Pisatuntema learned many of the ancient tribal myths and legends, and on the following pages they are given as they were related by her to the writer. Often, however, while telling the legends, she would be interrupted by others who would suggest or add certain details; but all were familiar with the subjects and at no time did they differ on any essential points. The myths and legends here recorded were collected by the writer during January and February, 1910.

|

|

Pisatuntema in 1909.

Public domain photo at Wikipedia.

|

I. Nané Chaha

Nané chaha (nané, ‘hill’ ; chaha, ‘high’) is the sacred spot in the mountainous country to the northward, always regarded with awe and reverence by the Choctaw.

In very ancient times, before man lived on the earth, the hill was formed, and from the topmost point a passage led down deep into the bosom of the earth. Later, when birds and animals lived, and the surface of the earth was covered with trees and plants of many sorts, and lakes and rivers had been formed, the Choctaw came forth through the passageway in Nané chaha. And from that point they scattered in all directions but ever afterwards remembered the hill from the summit of which they first beheld the light of the sun.

II

Soon after the earth (yahne) was made, men and grasshoppers came to the surface through a long passageway that led from a large cavern, in the interior of the earth, to the summit of a high hill, Nané chaha. There, deep down in the earth, in the great cavern, man and the grasshoppers had been created by Aba, the Great Spirit, having been formed of the yellow clay.

For a time the men and the grasshoppers continued to reach the surface together, and as they emerged from the long passageway they would scatter in all directions, some going north, others south, east, or west.

But at last the mother of the grasshoppers who had remained in the cavern was killed by the men and as a consequence there were no more grasshoppers to reach the surface, and ever after those that lived on the earth were known to the Choctaw as eske ilay, or ‘mother dead.” However, men continued to reach the surface of the earth through the long passageway that led to the summit of Nané chaha, and, as they moved about from place to place, they trampled upon many grasshoppers in the high grass, killing many and hurting others.

The grasshoppers became alarmed as they feared that all would be killed if men became more numerous and continued to come from the cavern in the earth. They spoke to Aba, who heard them and soon after caused the passageway to be closed and no more men were allowed to reach the surface. But as there were many men remaining in the cavern he changed them to ants and ever since that time the small ants have come forth from holes in the ground.

III

Aba, the good spirit above, created many men, all Choctaw, who spoke the language of the Choctaw, and understood one another. They came from the bosom of the earth, being formed of yellow clay, and no men had ever lived before them. One day all came together and, looking upwards, wondered what the clouds and the blue expanse above might be. They continued to wonder and talk among themselves and at last determined to endeavor to reach the sky. So they brought many rocks and began building a mound that was to have touched the heavens. That night, however, a wind blew strong from above and the rocks fell from the mound. The second morning they again began work on the mound, but while the men slept that night the rocks were again scattered by the winds. Once more, on the third morning, the builders set to their task. But once more, as they lay near the mound that night, wrapped in slumber, the winds came with such great force that the rocks were hurled down on them.

The men were not killed, but when daylight came and they made their way from beneath the rocks and began to speak to one another, all were astounded as well as alarmed — they spoke various languages and could not understand one another. Some continued to speak the original tongue, the language of the Choctaw, and from these sprang the Choctaw tribe. The others, who could not understand the language, began to fight among themselves. Finally they separated. The Choctaw remained the original people, the others scattered, some going north, some east, and others west, forming various tribes. This explains why there are so many tribes throughout the country at the present time.

IV. Okwa Falama, The ‘Returning Water,’ or Flood

On a certain day, many generations ago, and at a time when the earth was different from what it is now. Aba, the good spirit above, again appeared to the Choctaw. At first all who beheld him were startled and did not know how to act or what to say or do; but soon Aba told them to stop and listen, that he had appeared to them to deliver important words.

Soon all the Choctaw gathered to listen to the words of Aba. And he told them to build a large boat and when they had finished it to place in it all the birds and beasts of their country, and to gather food for the birds and the beasts together with a sufficient quantity to last themselves some days. They were then shown by Aba where to build the boat, and, as the spot he selected was high and dry and far from any water, the majority of the people lost confidence in what he told them and so went their ways, leaving only one family to build and stock the boat. Aba then told them that all must be in readiness within a certain time. The boat was at once begun, and while it was being built many strangers passed and asked the Choctaw why they were building a large boat there, far from any water. And the Choctaw replied and said they were following the commands of Aba : but why they had been so commanded they did not know.

The boat was completed long before the expiration of the specified time. Then the people went into the forests and swamps and collected all the animals, always getting two, a male and a female of each. And when all the animals had been gathered on board the boat, they called the birds and likewise took a male and a female of each. Next, food for all was gathered and placed aboard the craft. All being thus completed the Choctaw then went aboard the boat — thus fulfilling the commands of Aba.

That same night, after all the birds and beasts and likewise the builders of the boat were resting aboard the craft, rain began to fall and the wind blew with such force that the tallest pine trees were carried away. Thunder crashed in a manner such as had never before been heard, and the vivid flashes of lightning made all appear at times as bright as day.

All other people now realized that they too should have believed the words spoken by Aba. They hastened and endeavored to construct boats or rafts ; but it was too late and all were soon swept away by the gathering waters.

Soon the waters covered the land, and steadily it became deeper and deeper, and at last it surrounded the high land upon which the boat had been constructed. The water continued to gather and finally the boat floated; the water soon reached to the sky. The boat was blown about, first in one direction then in another, but neither it nor any of its many occupants experienced any damage.

On the morning of the fifth day the winds subsided and the sun shone forth bright and warm through the dark clouds. But when the people looked about them no land was visible, they were drifting on a broad expanse of water and often trees and dead animals floated on the surface near them, all bearing evidence of the severity of the storms and of the greatness of the catastrophe. And with the exception of the birds and beasts and people gathered in the boat, and the fishes in the water, all life had become extinct.

That same morning the crow and the dove were called and told to fly and endeavor to find land. They first went east, then south, and later west, but always returned without having seen any land. Crow then flew north and soon returned carrying with him a magnolia leaf and told of having seen an island. And as the boat was drifting in that direction they reached land before the sun had set that night.

As soon as the boat drifted to the shore of the island, the people and all the birds and animals went on land.

The willow was the only tree found growing on the island, and the people by rubbing two pieces of this wood together soon kindled a fire. While some were looking about the island they discovered a quantity of small white grains, unlike any they had ever before seen. Taking some of the grains, they placed them in the ground and from them grew the first corn ever raised by the Choctaw. Thus Aba had provided them with food.

V

Many generations hence the country will become crowded with people. Then there will be tribes that do not now exist. They will so increase in numbers that the land will scarcely sustain them. And they will become wicked and cruel and so fight among themselves, until at last Aba will cause the earth to be again covered with water. Thus mankind will be overwhelmed and all life will become extinct.

Time will pass, and the waters will subside, the rivers will flow between their banks as before. Forests of pine with grass and flowers will again cover the spots of land thus left dry by the receding waters. Later man and birds and beasts will again live.

In some of these myths missionary influence is so patent as to require no comment. The sacred hill of Nané chaha, however, has been mentioned by various writers in the past. Claiborne has recorded a very interesting reference to the hill, and has also identified the site. After referring to the legendary wanderings of the early people he continues:

“The main body traveled nearly due south, until they came to the Stooping Hill, Nane-wy-yah, now in the county of Winston, Mississippi, on the head waters of Pearl River. There they encamped and still continued to die. Finally, all perished but the book-bearer. He could not die. The Nane-wy-yah opened and he entered it and disappeared. After the lapse of many years, the Great Spirit created four infants, two of each sex, out of the ashes of the dead, at the foot of Nane-wy-yah. They were suckled by a panther. When they grew strong and were ready to depart, the book-bearer presented himself, and gave them bows and arrows and an earthen pot, and stretching his arms, said, ‘I give you these hunting grounds for your homes. When you leave them you die.’ With these words he stamped his foot — the Nane-wy-yah opened, and, holding the book above his head, he disappeared forever. The four then separated, two going to the left and two to the right, thus constituting the two Ik-sas, or clans, into which the Choctaws are divided. All the very aged Choctaws, on being interrogated as to where they were born, insist that they came out of Nane-wy-yah.”

In a footnote on the same page, Claiborne says:

“It [the hill] is on the head waters of Pearl River, and not far from the geographical center of the State. From information derived from Mr James Welsh and Dr S. P. Nash, of Neshoba county, the mound is described as some fifty feet high, covering about three-quarters of an acre, the apex level, with an area of about one fourth of an acre. On the north side of the mound are the remains of a circular earthwork or embankment, that must have been constructed for defensive objects. Many of the Choctaws examined by the Commissioners regard this mound as the mother, or birth-place of the tribe, and more than one claimant declared that he would not quit the country as long as the Nana-wy-yah remained. It was his mother, and he could not leave her.”

Such was the belief of the Choctaw of past generations, and the statements also serve as a verification of the antiquity of the myth as related by Pisa tun tema.

Thus, like many other primitive tribes, the Choctaw regarded the earth as their mother, and so held in reverence and awe the spot, Nané chaha, from whose summit they claimed to have first beheld the light of the sun.

The next section of the myth, III, appears to be a Choctaw rendition of the story of the building of Babel as told in the Old Testament. The Choctaw undoubtedly heard the story from the early missionaries, but certain parts of this version appear to be of native conception, consequently it may be that we have here their own ancient myth combined with, or modified by, the story told them by the missionaries.

The legend of the flood, IV, likewise shows strong evidence of having been influenced by the early teachings of the missionaries, although the majority of the American tribes are known to have had a somewhat similar myth of purely native origin.

Two versions of the Choctaw myths as they were told many years ago are recorded in The History of the Choctaw, Chickasaw and Natchez Indians, by H. B. Cushman, 1899, p. 282 et seq. Brinton omitted the Choctaw from his list of American tribes possessing a well-authenticated legend of the flood, nevertheless it is evident that that tribe did possess such a myth, although the version related by Pisatuntema may show to a marked degree the influence of her Catholic instructor, Pere Adrian Rouquette, who died some twenty years ago. In the last section, V, is given the Choctaw belief of the coming destruction of the world — a belief held by many primitive people.

The Choctaw appear to possess a vast number of folk tales, all of which have probably been told and retold through many generations. From Pisatuntema and others at Bayou Lacomb, the writer collected the tales recorded on the following pages.

Nalusa Falaya, or The Long Evil Being

The Nalusa Falaya somewhat resembles man. It is of about the size of a man and walks upright, but its face is shriveled, its eyes are very small and it has quite long, pointed ears. Its nose is likewise long. It lives in the densest woods, near swamps, away from the habitations of men. In some respects it resembles Kashehotapalo.

Often when hunters are in the woods, far from their homes, late in the day when the shadows have grown long beneath the pine trees, a Nalusa Falaya will come forth. Getting quite near a hunter it will call in a voice resembling that of a man. And some hunters, when they turn and see the Nalusa Falaya, are so affected that they fall to the ground and even become unconscious.

And while the hunter is thus prostrated on the ground, it approaches and sticks a small thorn into his hand or foot, and by so doing bewitches the hunter and transmits to him the power of doing evil to others; but a person never knows when he has been so bewitched by the Nalusa Falaya until his actions make it evident.

The Nalusa Falaya have many children which, when quite young, possess a peculiar power. They possess the power of removing their viscera at night, and in this lightened condition they become rather small, luminous bodies that may often be seen, along the borders of marshes.

Hashok Okwa Hui’ga

There is a certain spirit that lives in marshy places — often along the edges of swamps. It is never seen during the day, only at night, and even then its heart is the only part visible. Its heart appears as a small ball of fire that may be seen moving about, a short distance above the surface of the water.

At night, when a person is passing along a trail or going through the woods, and meets the Hashok Okwa Hui’ga he must immediately turn away and not look at it, otherwise he will certainly become lost and not arrive at his destination that night, but instead, travel in a circle.

The name is derived from the three words: hashok, grass; okwa, water; hui’ga, drop.

The two preceding tales refer to the ignis fatuus often seen along the swamps of St Tammany parish.

How The Snakes Acquired Their Poison

Long ago a certain vine grew along the edges of bayous, in shallow water. This vine was very poisonous, and often when the Choctaw would bathe or swim in the bayous they would come in contact with the vine and often become so badly poisoned that they would die as the result.

Now the vine was very kind and liked the Choctaw and consequently did not want to cause them so much trouble and pain. He would poison the people without being able to make known to them his presence there beneath the water. So he decided to rid himself of the poison. A few days later he called together the chiefs of the snakes, bees, wasps, and other similar creatures and told them of his desire to give them his poison, for up to that time no snake, bee or wasp had the power it now possesses, namely that of stinging a person.

The snakes and bees and wasps, after much talk, agreed to share the poison. The rattlesnake was the first to speak and he said: “I shall take the poison, but before I strike or poison a person I shall warn him by the noise of my tail, intesha; then if he does not heed me I shall strike.”

The water moccasion was the next to speak: “I also am willing to take some of your poison; but I shall never poison a person unless he steps on me.”

The small ground rattler was the last of the snakes to speak: “Yes I will gladly take of your poison and I will also jump at a person whenever I have a chance.” And so it has continued to do ever since.

Turtle and Turkey

Turkey met Turtle on the road one day and said to him: “Why are you so hard, without any fat?” “I was born that way,” replied Turtle. “But you cannot run fast,” said Turkey. “Oh yes I can; just watch me.” And with that Turtle walked along the road. “Well, even if you walk you are not able to run.” And then Turtle raised his head and went, as fast as he was able, down the path, but Turkey by walking only slowly could easily overtake him and so passed him. That being so easily accomplished Turkey laughed at Turtle and said to him: “You are too slow let me have your shell; I will put it on and run with the other turtles and easily beat them in a race.

Turkey then took Turtle’s shell and, getting in it, assumed the appearance of a Turtle. Soon meeting four other turtles all decided to race, and, of course, Turkey was victorious.

Turtle, Turkey, and the Ants

Turtle was asleep in some high grass when along came Turkey, who stepped upon him, crushing his shell, but not killing him. Turtle became angry and asked Turkey if he was not able to see him in the grass. “No,” replied Turkey, “you are so low; you should learn to walk as I do and hold your head up, that you might be seen.” But Turtle said he was not able to do so.

And then Turtle told Turkey to call the ants to come and repair him. Soon the ants arrived with many strands of colored thread. First they gnawed away the flesh and fat and so cleaned the broken bones. Then, with their colored threads, they sewed together the fragments of bones, thus making a hard bone covering on the outside of Turtle. The colored threads used by the ants may still be seen as colored streaks on the outside of Turtle’s shell.

Raccoon and Opossum

One day, long ago, Coon and ’Possum met in the woods. ’Possum then had a very large, bushy tail similar to Coon’s, but it was quite white, not with stripes upon it and dark, as was Coon’s. And when they met ‘Possum said to Coon: “Why is your tail dark, with stripes upon it, while mine is only white?” Then Coon answered him saying: “I was born so, but if you will do as I tell you, yours will also be dark.” “But what am I to do?” asked ’Possum. “I am willing to do as you tell me.” Thereupon Coon told ’Possum to make a fire and hold his tail near it, and that soon the white hairs would turn brown, but to be very careful. And together they kindled a fire of leaves and twigs. But ’Possum, very eager to turn the hairs brown, went too near the fire and actually burned the hairs off of his tail, and it has remained bare ever since.

The Geese, the Ducks, and Water

The geese and ducks were created before there was any water on the surface of the earth. They wanted water so as to be able to swim and dive as was their nature, but Aba objected and said he would not allow water on the earth as it was dangerous, and he then said to the geese and ducks: “What is the good of water, and why do you want it?” And together they answered “We want it to drink on hot days.” Then Aba asked how much water they wanted and the ducks replied: “We want a great deal of water; we want swamps and rivers and lakes to be scattered all over the surface of the earth. And also we want grass and moss to grow in the water, and frogs and snakes to live there.”

Aba asked the geese and ducks why they wanted frogs and snakes to live in the water and they answered that frogs and snakes were their food, and they told Aba how they could dive and swim beneath the water and catch them. And then Aba told them how he had made the sun, the air, and the earth and asked if that was not enough. “No,” was the reply of all, “we want water.”

The alligators then spoke to Aba and likewise asked for water. The alligators told of their desire to live in dark places, deep in the waters of bayous, among the roots of cypress and black gum trees, for there the water was the best.

Aba then spoke to all saying he would give them all the water they desired, but that he had talked with them to hear what they would have to say.

And even now the ducks and geese claim the swamps and marshes.

The preceding may be regarded as fair examples of the primitive folk-tales of the Choctaw. They are free from any indications of having been derived from stories of European origin. Environment has been the chief factor in the development of these tales. The dense swamps and forests surrounding the homes of the Choctaw were regarded by them as the haunts of mysterious beings to whom they attributed any injury that befell their hunters while away from home. To these same “spirits” were attributed any unusual sounds as well as natural phenomena. Thus in the mind of the Choctaw they were at all times surrounded by spiritual beings, some of which would make themselves visible to the hunters, while others only manifested their presence by weird sounds.

Notes

- Claiborne. J. F. H. Claiborne, Mississippi as a Province, Territory and State, Jackson, Miss., 1880, vol. I, p. 519.

- Aba. For other versions of this myth consult Charles Lanman, Adventures in the Wilds of the United States, Philadelphia, 1856, vol. 11, p. 429; and George Catlin, Letters and Notes, London, 1841.

Prepared by:

- Erica Clark

- Cole Crowder

- Philip Elliott

- Hoang Ho

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Bushnell, David I. “Myths Of The Louisiana Choctaw.” American Anthropologist 12 12 (1910): 526-535. Web. 6 Nov. 2013. https:// archive.org/ details/ jstor-659795.