Anthology

of Louisiana Literature

Dora Richards Miller.

George Washington Cable, ed.

“War Diary of a Union Woman in the South: 1860-63.”

WAR DIARY OF A UNION WOMAN IN THE SOUTH

| I. |

Secession |

262 |

| II. |

The Volunteers.—Fort Sumter |

266 |

| III. |

Tribulation |

269 |

| IV. |

A Beleaguered City |

274 |

| V. |

Married |

279 |

| VI. |

How it was in Arkansas |

281 |

| VII. |

The Fight for Food and Clothing |

285 |

| VIII. |

Drowned out and starved out |

289 |

| IX. |

Homeless and Shelterless |

296 |

| X. |

Frights and Perils in Steele's Bayou |

302 |

| XI. |

Wild Times in Mississippi |

308 |

| XII. |

Vicksburg |

320 |

| XIII. |

Preparations for the Siege |

326 |

| XIV. |

The Siege itself |

334 |

| XV. |

Gibraltar falls |

343 |

|

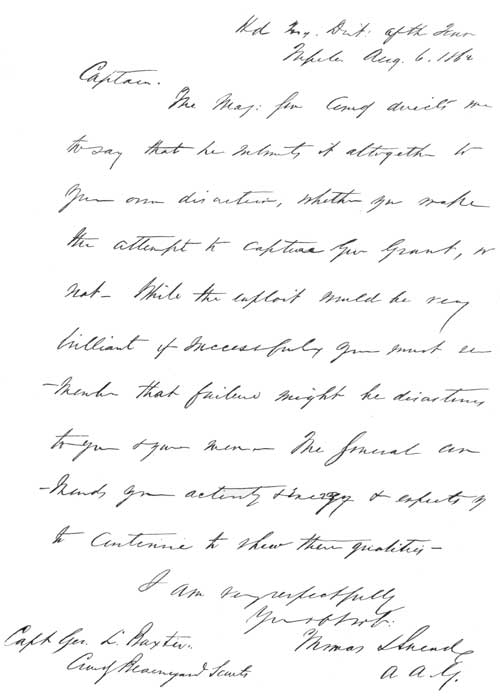

[The following diary was originally written in lead pencil and in

a book

the leaves of which were too soft to take ink legibly. I have it

direct

from the hands of its writer, a lady whom I have had the honor to

know for

nearly thirty years. For good reasons the

author's name is

omitted

and

the initials of people and the names of places are sometimes

fictitiously

given. Many of the persons mentioned were my own acquaintances and

friends. When some twenty years afterwards she first resolved to

publish

it, she brought me a clear, complete copy in ink. It had cost much

trouble, she said, for much of the pencil writing had been made

under such

disadvantages and was so faint that at times she could decipher it

only

under direct sunlight. She had succeeded, however, in making a

copy,

verbatim except for occasional improvement in the

grammatical form of a

sentence, or now and then the omission, for brevity's sake, of

something

unessential. The narrative has since been severely abridged to

bring it

within the limits of this volume.

In reading this diary one is much charmed with its constant

understatement

of romantic and perilous incidents and conditions. But the

original

penciled pages show that, even in copying, the strong bent of the

writer

to be brief has often led to the exclusion of facts that enhance

the

interest of exciting situations, and sometimes the omission robs

her own

heroism of due emphasis. I have restored one example of this in

the short

paragraph following her account of the night she spent fanning her

sick

husband on their perilous voyage down the Mississippi.]

G.W.C.

I.

SECESSION.

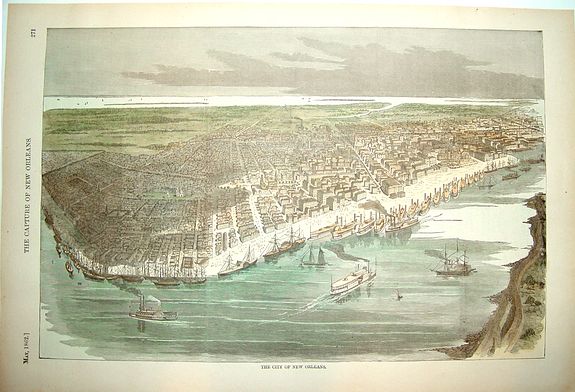

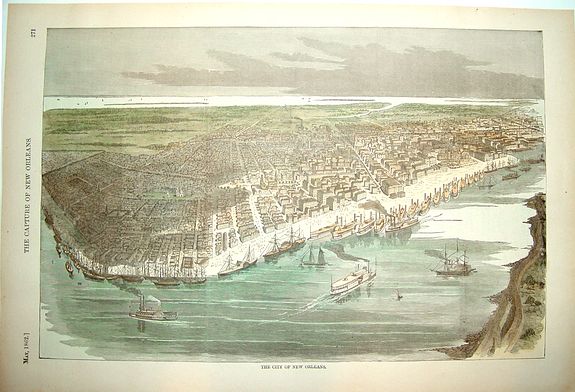

New Orleans, Dec. 1, 1860. — I understand it now. Keeping

journals is for

those who can not, or dare not, speak out. So I shall set up a

journal,

being only a rather lonely young girl in a very small and hated

minority.

On my return here in November, after a foreign voyage and absence

of many

months, I found myself behind in knowledge of the political

conflict, but

heard the dread sounds of disunion and war muttered in threatening

tones.

Surely no native-born woman loves her country better than I love

America.

The blood of one of its revolutionary patriots flows in my veins,

and it

is the Union for which he pledged his

"life, fortune, and sacred

honor"

that I love, not any divided or special section of it. So I have

been

reading attentively and seeking light from foreigners and natives

on all

questions at issue. Living from birth in slave countries, both

foreign

and American, and passing through one slave insurrection in early

childhood, the saddest and also the pleasantest features of

slavery have

been familiar. If the South goes to war for slavery, slavery is

doomed in

this country. To say so is like opposing one drop to a roaring

torrent.

This is a good time to follow St. Paul's advice that women should

refrain

from speaking, but they are speaking more than usual and forcing

others to

speak against their will.

Sunday, Dec. — , 1860. — In this season for peace I had hoped

for a lull

in the excitement, yet this day has been full of bitterness.

"Come, G.,"

said Mrs. F. at breakfast, "leave your church for to-day

and come with

us to hear Dr. —— on the situation. He will convince you." "It is

good to

be convinced," I said; "I will go." The church was crowded to

suffocation

with the élite of New Orleans. The preacher's text was, "Shall we

have

fellowship with the stool of iniquity which frameth mischief as a

law?"

. . . The sermon was over at last and then followed a prayer

. . . Forever

blessed be the fathers of the

Episcopal Church

for giving us a

fixed

liturgy! When we met at dinner Mrs. F. exclaimed, "Now, G., you

heard him

prove from the Bible that slavery is right and that therefore

secession

is. Were you not convinced?" I said, "I was so busy thinking how

completely it proved too that Brigham Young is right about

polygamy that

it quite weakened the force of the argument for me." This raised a

laugh,

and covered my retreat.

Jan. 26, 1861. — The solemn boom of cannon today announced

that the

convention have passed the ordinance of secession. We must take a

reef in

our patriotism and narrow it down to State limits. Mine still

sticks out

all around the borders of the State. It will be bad if New Orleans

should

secede from Louisiana and set up for herself. Then indeed I would

be

“cabined, cribbed, confined.”

The faces in the house are jubilant

to-day.

Why is it so easy for them and not for me to "ring out the old,

ring in

the new"? I am out of place.

Jan. 28, Monday. — Sunday has now got to be a day of special

excitement.

The gentlemen save all the sensational papers to regale us with at

the

late Sunday breakfast. Rob opened the battle yesterday morning by

saying

to me in his most aggressive manner, "G., I believe these are your

sentiments"; and then he read aloud an article from the

"Journal des Debats"

expressing in rather contemptuous terms the fact that

France will

follow the policy of non-intervention. When I answered: "Well,

what do you

expect? This is not their quarrel," he raved at me, ending by a

declaration that he would willingly pay my passage to foreign

parts if I

would like to go. "Rob," said his father, "keep cool; don't let

that

threat excite you. Cotton is king. Just wait till they feel the

pinch a

little; their tone will change." I went to Trinity Church. Some

Union

people who are not Episcopalians go there now because the pastor

has not

so much chance to rail at the Lord when things are not going to

suit: but

yesterday was a marked Sunday. The usual prayer for the President

and

Congress was changed to the "governor and people of this

commonwealth and

their representatives in convention assembled."

The city was very lively and noisy this evening with rockets and

lights in

honor of secession. Mrs. F., in common with the neighbors,

illuminated. We

walked out to see the houses of others gleaming amid the dark

shrubbery

like a fairy scene. The perfect stillness added to the effect,

while the

moon rose slowly with calm splendor. We hastened home to dress for

a

soirée, but on the stairs Edith said, "G., first come and help me

dress

Phoebe and Chloe [the negro servants]. There is a ball to-night in

aristocratic colored society. This is Chloe's first introduction

to New

Orleans circles, and Henry Judson, Phoebe's husband, gave five

dollars for

a ticket for her." Chloe is a recent purchase from Georgia. We

superintended their very stylish toilets, and Edith said, "G., run

into

your room, please, and write a pass for Henry. Put Mr. D.'s name

to it."

"Why, Henry is free," I said. — "That makes no difference; all

colored

people must have a pass if out late. They choose a master for

protection

and always carry his pass. Henry chose Mr. D., but he's lost the

pass he

had." When the pass was ready, a carriage dashed up to the

back-gate and

the party drove off in fine style.

At the soirée we had secession talk sandwiched everywhere;

between the

supper, and the music, and the dance; but midnight has come, and

silence,

and a few too brief hours of oblivion.

II.

THE VOLUNTEERS. — FORT SUMTER.

Feb. 24, 1861. — The toil of the week has ended. Nearly a

month has

passed since I wrote here. Events have crowded upon one another. A

lowering sky closes in upon the gloomy evening, and a moaning wind

is

sobbing in every key. They seem in keeping with the national

sorrow, and

in lieu of other sympathy I am glad to have that of Nature

to-night. On

the 4th the cannon boomed in honor of Jefferson Davis's election,

and day

before yesterday Washington's Birthday was made the occasion of

another

grand display and illumination, in honor of the birth of a new

nation and

the breaking of that Union which he labored to cement. We drove to

the

racecourse to see the review of troops. A flag was presented to

the

Washington Artillery by ladies. Senator Judah Benjamin

made an impassioned speech. The banner was orange satin on one

side,

crimson silk on the other, the pelican and brood embroidered in

pale green

and gold. Silver crossed cannon surmounted it, orange-colored

fringe

surrounded it, and crimson tassels drooped from it. It was a

brilliant,

unreal scene; with military bands clashing triumphant music,

elegant

vehicles, high-stepping horses, and lovely women richly appareled.

Wedding cards have been pouring in till the contagion has reached

us;

Edith will be married next Thursday. The wedding dress is being

fashioned, and the bridesmaids and groomsmen have arrived. Edith

has

requested me to be special mistress of ceremonies on Thursday

evening, and

I have told this terrible little rebel, who talks nothing but

blood and

thunder, yet faints at the sight of a worm, that if I fill that

office no

one shall mention war or politics during the whole evening, on

pain of

expulsion. The clock points to ten. I must lay the pen aside.

March 10, 1861. — The excitement in this house has risen to

fever heat

during the past week. The four gentlemen have each a different

plan for

saving the country, and now that the bridal bouquets have faded,

the three

ladies have again turned to public affairs; Lincoln's inauguration

and the

story of the disguise in which he traveled to Washington is a

never-ending

source of gossip. The family board being the common forum, each

gentleman

as he appears first unloads his pockets of papers from all the

Southern

States, and then his overflowing heart to his eager female

listeners, who

in turn relate, inquire, sympathize, or cheer. If I dare express a

doubt

that the path to victory will be a flowery one, eyes flash, cheeks

burn,

and tongues clatter, till all are checked up suddenly by a warning

rap for

"Order, order!" from the amiable lady presiding. Thus we swallow

politics

with every meal. We take a mouthful and read a telegram, one eye

on table,

the other on the paper. One must be made of cool stuff to keep

calm and

collected. I say but little. There is one great comfort; this war

fever

has banished small talk. The black servants move about quietly,

never

seeming to notice that this is all about them.

"How can you speak so plainly before them?" I say.

"Why, what matter? They know that we shall keep the whip-handle."

April 13, 1861. — More than a month has passed since the

last date here.

This afternoon I was seated on the floor covered with loveliest

flowers,

arranging a floral offering for the fair, when the gentlemen

arrived (and

with papers bearing the news of the fall of Fort Sumter, which, at

her

request, I read to Mrs. F.).

April 20. — The last few days have glided away in a halo of

beauty. I

can't remember such a lovely spring ever before. But nobody has

time or

will to enjoy it. War, war! is the one idea. The children play

only with

toy cannons and soldiers; the oldest inhabitant goes by every day

with his

rifle to practice; the public squares are full of companies

drilling, and

are now the fashionable resorts. We have been told that it is best

for

women to learn how to shoot too, so as to protect themselves when

the men

have all gone to battle. Every evening after dinner we adjourn to

the back

lot and fire at a target with pistols.

Yesterday I dined at Uncle Ralph's. Some members of the bar were

present

and were jubilant about their brand-new Confederacy. It would soon

be the

grandest government ever known. Uncle Ralph said solemnly, "No,

gentlemen;

the day we seceded the star of our glory set." The words sunk into

my mind

like a knell, and made me wonder at the mind that could recognize

that

and yet adhere to the doctrine of secession.

In the evening I attended a farewell gathering at a friend's

whose

brothers are to leave this week for Richmond. There was music. No

minor

chord was permitted.

III.

TRIBULATION.

April 25, 1861. — Yesterday I went with Cousin E. to have

her picture

taken. The picture-galleries are doing a thriving business. Many

companies

are ordered off to take possession of Fort Pickens (Florida), and

all seem

to be leaving sweethearts behind them. The crowd was in high

spirits; they

don't dream that any destinies will be spoiled. When I got home

Edith was

reading from the daily paper of the dismissal of Miss G. from her

place as

teacher for expressing abolition sentiments, and that she would be

ordered

to leave the city. Soon a lady came with a paper setting forth

that she

has established a "company" — we are nothing if not military — for

making

lint and getting stores of linen to supply the hospitals.

My name went down. If it hadn't, my spirit would have been

wounded as with

sharp spears before night. Next came a little girl with a

subscription

paper to get a flag for a certain company. The little girls,

especially

the pretty ones, are kept busy trotting around with subscription

lists. A

gentleman leaving for Richmond called to bid me good-bye. We had a

serious

talk on the chances of his coming home maimed. He handed me a rose

and

went off gaily, while a vision came before me of the crowd of

cripples

that will be hobbling around when the war is over. It stayed with

me all

the afternoon while I shook hands with one after another in their

shining

gray and gold uniforms. Latest of all came little Guy, Mr. F.'s

youngest

clerk, the pet of the firm as well as of his home, a mere boy of

sixteen.

Such senseless sacrifices seem a sin. He chattered brightly, but

lingered

about, saying good-bye. He got through it bravely until Edith's

husband

incautiously said, "You didn't kiss your little sweetheart," as he

always

called Ellie, who had been allowed to sit up. He turned suddenly,

broke

into agonizing sobs and ran down the steps. I went right up to my

room.

Suddenly the midnight stillness was broken by the sound of

trumpets and

flutes. It was a serenade, by her lover, to the young lady across

the

street. She leaves to-morrow for her home in Boston, he joins the

Confederate army in Virginia. Among the callers yesterday she came

and

astonished us all by the change in her looks. She is the only

person I

have yet seen who seems to realize the horror that is coming. Was

this

pallid, stern-faced creature, the gentle, glowing Nellie whom we

had

welcomed and admired when she came early last fall with her

parents to

enjoy a Southern winter?

May 10, 1861. — I am tired and ashamed of myself. Last week

I attended a

meeting of the lint society to hand in the small contribution of

linen I

had been able to gather. We scraped lint till it was dark. A paper

was

shown, entitled the "Volunteer's Friend," started by the girls of

the high

school, and I was asked to help the girls with it. I positively

declined.

To-day I was pressed into service to make red flannel

cartridge-bags for

ten-inch columbiads. I basted while Mrs. S. sewed, and I felt

ashamed to

think that I had not the moral courage to say, "I don't approve of

your

war and won't help you, particularly in the murderous part of it."

May 27, 1861. — This has been a scenic Sabbath. Various

companies about

to depart for Virginia occupied the prominent churches to have

their flags

consecrated. The streets were resonant with the clangor of drums

and

trumpets. E. and myself went to Christ Church because the

Washington

Artillery were to be there.

June 13. — To-day has been appointed a Fast Day. I spent the

morning

writing a letter on which I put my first Confederate

postage-stamp. It is

of a brown color and has a large 5 in the center. To-morrow must

be

devoted to all my foreign correspondents before the expected

blockade cuts

us off.

June 29. — I attended a fine luncheon yesterday at one of

the public

schools. A lady remarked to a school official that the cost of

provisions

in the Confederacy was getting very high, butter, especially,

being scarce

and costly. "Never fear, my dear madame," he replied. "Texas alone

can

furnish butter enough to supply the whole Confederacy; we'll soon

be

getting it from there." It's just as well to have this sublime

confidence.

July 15, 1861. — The quiet of midsummer reigns, but ripples

of excitement

break around us as the papers tell of skirmishes and attacks here

and

there in Virginia. "Rich Mountain" and "Carrick's Ford" were the

last.

"You see," said Mrs. D. at breakfast to-day, "my prophecy is

coming true

that Virginia will be the seat of war." "Indeed," I burst out,

forgetting

my resolution not to argue, "you may think yourselves lucky if

this war

turns out to have any seat in particular."

So far, no one especially connected with me has gone to fight.

How glad I

am for his mother's sake that Rob's lameness will keep him at

home. Mr.

F., Mr. S., and Uncle Ralph are beyond the age for active service,

and

Edith says Mr. D. can't go now. She is very enthusiastic about

other

people's husbands being enrolled, and regrets that her Alex is not

strong

enough to defend his country and his rights.

July 22. — What a day! I feel like one who has been out in a

high wind,

and cannot get my breath. The news-boys are still shouting with

their

extras, "Battle of Bull's Run! List of the killed! Battle of

Manassas!

List of the wounded!" Tender-hearted Mrs. F. was sobbing so she

could not

serve the tea; but nobody cared for tea. "O G.!" she said, "three

thousand

of our own, dear Southern boys are lying out there." "My dear

Fannie,"

spoke Mr. F., "they are heroes now. They died in a glorious cause,

and it

is not in vain. This will end it. The sacrifice had to be made,

but those

killed have gained immortal names." Then Rob rushed in with a new

extra,

reading of the spoils captured, and grief was forgotten. Words

cannot

paint the excitement. Rob capered about and cheered; Edith danced

around

ringing the dinner bell and shouting, "Victory!" Mrs. F. waved a

small

Confederate flag, while she wiped her eyes, and Mr. D. hastened to

the

piano and in his most brilliant style struck up "Dixie," followed

by "My

Maryland" and the "Bonnie Blue Flag."

"Do not look so gloomy, G.," whispered Mr. S. "You should be

happy

to-night; for, as Mr. F. says, now we shall have peace."

"And is that the way you think of the men of your own blood and

race?" I

replied. But an utter scorn choked me, and I walked out of the

room. What

proof is there in this dark hour that they are not right? Only the

emphatic answer of my own soul. To-morrow I will pack my trunk and

accept

the invitation to visit at Uncle Ralph's country-house.

Sept. 25, 1861. (Home again from "The Pines.") — When

I opened the door

of Mrs. F.'s room on my return, the rattle of two sewing-machines

and a

blaze of color met me.

"Ah! G., you are just in time to help us; these are coats for

Jeff

Thompson's men. All the cloth in the city is exhausted; these

flannel-lined oilcloth table-covers are all we could obtain to

make

overcoats for Thompson's poor boys. They will be very warm and

serviceable."

"Serviceable, yes! The Federal army will fly when they see those

coats! I

only wish I could be with the regiment when these are shared

around." Yet

I helped make them.

Seriously, I wonder if any soldiers will ever wear these

remarkable coats.

The most bewildering combination of brilliant, intense reds,

greens,

yellows, and blues in big flowers meandering over as vivid

grounds; and as

no table-cover was large enough to make a coat, the sleeves of

each were

of a different color and pattern. However, the coats were duly

finished.

Then we set to work on gray pantaloons, and I have just carried a

bundle

to an ardent young lady who wishes to assist. A slight gloom is

settling

down, and the inmates here are not quite so cheerfully confident

as in

July.

IV.

A BELEAGUERED CITY.

Oct. 22, 1861. — When I came to breakfast this morning Rob

was capering

over another victory — Ball's Bluff. He would read me, "We pitched

the

Yankees over the bluff," and ask me in the next breath to go to

the

theater this evening. I turned on the poor fellow: "Don't tell me

about

your victories. You vowed by all your idols that the blockade

would be

raised by October 1, and I notice the ships are still serenely

anchored

below the city."

"G., you are just as pertinacious yourself in championing your

opinions.

What sustains you when nobody agrees with you?"

I would not answer.

Oct. 28, 1861. — When I dropped in at Uncle Ralph's last

evening to

welcome them back, the whole family were busy at a great

center-table

copying sequestration acts for the Confederate Government. The

property of

all Northerners and Unionists is to be sequestrated, and Uncle

Ralph can

hardly get the work done fast enough. My aunt apologized for the

rooms

looking chilly; she feared to put the carpets down, as the city

might be

taken and burned by the Federals. "We are living as much packed up

as

possible. A signal has been agreed upon, and the instant the army

approaches we shall be off to the country again."

Great preparations are being made for defense. At several other

places

where I called the women were almost hysterical. They seemed to

look

forward to being blown up with shot and shell, finished with cold

steel,

or whisked off to some Northern prison. When I got home Edith and

Mr. D.

had just returned also.

"Alex," said Edith, "I was up at your orange-lots to-day and the

sour

oranges are dropping to the ground, while they cannot get lemons

for our

sick soldiers."

"That's my kind, considerate wife," replied Mr. D. "Why didn't I

think of

that before? Jim shall fill some barrels to-morrow and take them

to the

hospitals as a present from you."

Nov. 10. — Surely this year will ever be memorable to me for

its

perfection of natural beauty. Never was sunshine such pure gold,

or

moonlight such transparent silver. The beautiful custom prevalent

here of

decking the graves with flowers on All Saint's day was well

fulfilled, so

profuse and rich were the blossoms. On All-hallow Eve Mrs. S. and

myself

visited a large cemetery. The chrysanthemums lay like great masses

of snow

and flame and gold in every garden we passed, and were piled on

every

costly tomb and lowly grave. The battle of Manassas robed many of

our

women in mourning, and some of these, who had no graves to deck,

were

weeping silently as they walked through the scented avenues.

A few days ago Mrs. E. arrived here. She is a widow, of Natchez,

a friend

of Mrs. F.'s, and is traveling home with the dead body of her

eldest son,

killed at Manassas. She stopped two days waiting for a boat, and

begged me

to share her room and read her to sleep, saying she couldn't be

alone

since he was killed; she feared her mind would give way. So I read

all the

comforting chapters to be found till she dropped into

forgetfulness, but

the recollection of those weeping mothers in the cemetery banished

sleep

for me.

Nov. 26, 1861. — The lingering summer is passing into those

misty autumn

days I love so well, when there is gold and fire above and around

us. But

the glory of the natural and the gloom of the moral world agree

not well

together. This morning Mrs. F. came to my room in dire distress.

"You

see," she said, "cold weather is coming on fast, and our poor

fellows are

lying out at night with nothing to cover them. There is a wail for

blankets, but there is not a blanket in town. I have gathered up

all the

spare bed-clothing, and now want every available rug or

table-cover in the

house. Can't I have yours, G.? We must make these small sacrifices

of

comfort and elegance, you know, to secure independence and

freedom."

"Very well," I said, denuding the table. "This may do for a

drummer boy."

Dec. 26, 1861. — The foul weather cleared off bright and

cool in time for

Christmas. There is a midwinter lull in the movement of troops. In

the

evening we went to the grand bazaar in the St. Louis Hotel, got up

to

clothe the soldiers. This bazaar has furnished the gayest, most

fashionable war-work yet, and has kept social circles in a flutter

of

pleasant, heroic excitement all through December. Everything

beautiful or

rare garnered in the homes of the rich was given for exhibition,

and in

some cases for raffle and sale. There were many fine paintings,

statues,

bronzes, engravings, gems, laces — in fact, heirlooms, and

bric-?-brac of

all sorts. There were many lovely Creole girls present, in

exquisite

toilets, passing to and fro through the decorated rooms, listening

to the

band clash out the Anvil Chorus.

This morning I joined the B.'s and their party in a visit to the

new

fortifications below the city. It all looks formidable enough, but

of

course I am no judge of military defenses. We passed over the

battle-ground where Jackson fought the English, and thinking of

how he

dealt with treason, one could almost fancy his unquiet ghost

stalking

about.

Jan. 2, 1862. — I am glad enough to bid '61 goodbye. Most

miserable year

of my life! What ages of thought and experience have I not lived

in it.

Last Sunday I walked home from church with a young lady teacher

in the

public schools. The teachers have been paid recently in

"shin-plasters." I

don't understand the horrid name, but nobody seems to have any

confidence

in the scrip. In pure benevolence I advised my friend to get her

money

changed into coin, as in case the Federals took the city she would

be in a

bad fix, being in rather a lonely position. She turned upon me in

a rage.

"You are a black-hearted traitor," she almost screamed at me in

the

street, this well-bred girl! "My money is just as good as coin

you'll see!

Go to Yankee land. It will suit you better with your sordid views

and want

of faith, than the generous South."

"Well," I replied, "when I think of going, I'll come to you for a

letter

of introduction to your grandfather in Yankee land." I said

good-morning

and turned down another street in a sort of a maze, trying to put

myself

in her place and see what there was sordid in my advice.

Luckily I met Mrs. B. to turn the current of thought. She was

very merry.

The city authorities have been searching houses for fire-arms. It

is a

good way to get more guns, and the homes of those men suspected of

being

Unionists were searched first. Of course they went to Dr. B.'s. He

met

them with his own delightful courtesy. "Wish to search for arms?

Certainly, gentlemen." He conducted them through all the house

with

smiling readiness, and after what seemed a very thorough search

bowed them

politely out. His gun was all the time safely reposing between the

canvas

folds of a cot-bed which leaned folded up together against the

wall, in

the very room where they had ransacked the closets. Queerly, the

rebel

families have been the ones most anxious to conceal all weapons.

They have

dug pits quietly at night in the back yards, and carefully

wrapping the

weapons, buried them out of sight. Every man seems to think he

will have

some private fighting to do to protect his family.

V.

MARRIED.

Friday, Jan. 24, 1862. (On steamboat W., Mississippi River.) — With

a

changed name I open you once more, my journal. It was a sad time

to wed,

when one knew not how long the expected conscription would spare

the

bridegroom. The women-folk knew how to sympathize with a girl

expected to

prepare for her wedding in three days, in a blockaded city, and

about to

go far from any base of supplies. They all rallied round me with

tokens of

love and consideration, and sewed, shopped, mended, and packed, as

if

sewing soldier clothes. They decked the whole house and the church

with

flowers. Music breathed, wine sparkled, friends came and went. It

seemed a

dream, and comes up now and again out of the afternoon sunshine

where I

sit on deck. The steamboat slowly plows its way through lumps of

floating

ice, — a novel sight to me, — and I look forward wondering whether the

new

people I shall meet will be as fierce about the war as those in

New

Orleans. That past is to be all forgiven and forgotten; I

understood thus

the kindly acts that sought to brighten the threshold of a new

life.

Feb. 15, 1862. (Village of X.) — We reached Arkansas Landing

at

nightfall. Mr. Y., the planter who owns the landing, took us right

up to

his residence. He ushered me into a large room where a couple of

candles

gave a dim light, and close to them, and sewing as if on a race

with time,

sat Mrs. Y. and a little negro girl, who was so black and sat so

stiff and

straight she looked like an ebony image. This was a large

plantation; the

Y.'s knew H. very well, and were very kind and cordial in their

welcome

and congratulations. Mrs. Y. apologized for continuing her work;

the war

had pushed them this year in getting the negroes clothed, and she

had to

sew by dim candles, as they could obtain no more oil. She asked if

there

were any new fashions in New Orleans.

Next morning we drove over to our home in this village. It is the

county-seat, and was, till now, a good place for the practice of

H.'s

profession. It lies on the edge of a lovely lake. The adjacent

planters

count their slaves by the hundreds. Some of them live with a good

deal of

magnificence, using service of plate, having smoking-rooms for the

gentlemen built off the house, and entertaining with great

hospitality.

The Baptists, Episcopalians, and Methodists hold services on

alternate

Sundays in the court-house. All the planters and many others, near

the

lake shore, keep a boat at their landing, and a raft for crossing

vehicles

and horses. It seemed very piquant at first, this taking our boat

to go

visiting, and on moonlight nights it was charming. The woods

around are

lovelier than those in Louisiana, though one misses the moaning of

the

pines. There is fine fishing and hunting, but these cotton estates

are not

so pleasant to visit as sugar plantations.

But nothing else has been so delightful as, one morning, my first

sight of

snow and a wonderful, new, white world.

Feb. 27, 1862. — The people here have hardly felt the war

yet. There are

but two classes. The planters and the professional men form one;

the very

poor villagers the other. There is no middle class. Ducks and

partridges,

squirrels and fish, are to be had. H. has bought me a nice pony,

and

cantering along the shore of the lake in the sunset is a panacea

for

mental worry.

VI.

HOW IT WAS IN ARKANSAS.

March 11, 1862. — The serpent has entered our Eden. The

rancor and

excitement of New Orleans have invaded this place. If an

incautious word

betrays any want of sympathy with popular plans, one is

"traitorous,"

"ungrateful," "crazy." If one remains silent, and controlled, then

one is

"phlegmatic," "cool-blooded," "unpatriotic." Cool-blooded!

Heavens! if

they only knew. It is very painful to see lovable and intelligent

women

rave till the blood mounts to face and brain. The immediate cause

of this

access of war fever has been the battle of Pea Ridge. They scout

the idea

that Price and Van Dorn have been completely worsted. Those who

brought

the news were speedily told what they ought to say. "No, it is

only a

serious check; they must have more men sent forward at once. This

country

must do its duty." So the women say another company must

be raised.

We were guests at a dinner-party yesterday. Mrs. A. was very

talkative.

"Now, ladies, you must all join in with a vim and help equip

another

company."

"Mrs. L.," she said, turning to me, "are you not going to send

your

husband? Now use a young bride's influence and persuade him; he

would be

elected one of the officers." "Mrs. A.," I replied, longing to

spring up

and throttle her, "the Bible says, 'When a man hath married a new

wife, he

shall not go to war for one year, but remain at home and cheer up

his

wife.'" . . .

"Well, H.," I questioned, as we walked home after crossing the

lake, "can

you stand the pressure, or shall you be forced into volunteering?"

"Indeed," he replied, "I will not be bullied into enlisting by

women, or

by men. I will sooner take my chance of conscription and feel

honest about

it. You know my attachments, my interests are here; these are my

people.

I could never fight against them; but my judgment disapproves

their

course, and the result will inevitably be against us."

This morning the only Irishman left in the village presented

himself to H.

He has been our woodsawyer, gardener, and factotum, but having

joined the

new company, his time recently has been taken up with drilling. H.

and Mr.

R. feel that an extensive vegetable garden must be prepared while

he is

here to assist or we shall be short of food, and they sent for him

yesterday.

"So, Mike, you are really going to be a soldier?"

"Yes, sor; but faith, Mr. L., I don't see the use of me going to

shtop a

bullet when sure an' I'm willin' for it to go where it plazes."

March 18, 1862. — There has been unusual gayety in this

little village

the past few days. The ladies from the surrounding plantations

went to

work to get up a festival to equip the new company. As Annie and

myself

are both brides recently from the city, requisition was made upon

us for

engravings, costumes, music, garlands, and so forth. Annie's heart

was in

the work; not so with me. Nevertheless, my pretty things were

captured,

and shone with just as good a grace last evening as if willingly

lent. The

ball was a merry one. One of the songs sung was "Nellie Gray," in

which

the most distressing feature of slavery is bewailed so pitifully.

To sing

this at a festival for raising money to clothe soldiers fighting

to

perpetuate that very thing was strange.

March 20, 1862. — A man professing to act by General

Hindman's orders is

going through the country impressing horses and mules. The

overseer of a

certain estate came to inquire of H. if he had not a legal right

to

protect the property from seizure. Mr. L. said yes, unless the

agent could

show some better credentials than his bare word. This answer soon

spread

about, and the overseer returned to report that it excited great

indignation, especially among the company of new volunteers. H.

was

pronounced a traitor, and they declared that no one so untrue to

the

Confederacy should live there. When H. related the circumstance at

dinner,

his partner, Mr. R., became very angry, being ignorant of H.'s

real

opinions. He jumped up in a rage and marched away to the village

thoroughfare. There he met a batch of the volunteers, and said,

"We know

what you have said of us, and I have come to tell you that you are

liars,

and you know where to find us."

Of course I expected a difficulty; but the evening passed, and we

retired

undisturbed. Not long afterward a series of indescribable sounds

broke the

stillness of the night, and the tramp of feet was heard outside

the house.

Mr. R. called out, "It's a serenade, H. Get up and bring out all

the wine

you have." Annie and I peeped through the parlor window, and lo!

it was

the company of volunteers and a diabolical band composed of bones

and

broken-winded brass instruments. They piped and clattered and

whined for

some time, and then swarmed in, while we ladies retreated and

listened to

the clink of glasses.

March 22, 1862. — H., Mr. R., and Mike have been very busy

the last few

days getting the acre of kitchen-garden plowed and planted. The

stay-law

has stopped all legal business, and they have welcomed this work.

But

to-day a thunderbolt fell in our household. Mr. R. came in and

announced

that he has agreed to join the company of volunteers. Annie's

Confederate

principles would not permit her to make much resistance, and she

has been

sewing and mending as fast as possible to get his clothes ready,

stopping

now and then to wipe her eyes. Poor Annie! She and Max have been

married

only a few months longer than we have; but a noble sense of duty

animates

and sustains her.

VII.

THE FIGHT FOR FOOD AND CLOTHING.

April 1, 1862. — The last ten days have brought changes in

the house. Max

R. left with the company to be mustered in, leaving with us his

weeping

Annie. Hardly were her spirits somewhat composed when her brother

arrived

from Natchez to take her home. This morning he, Annie, and Reeney,

the

black handmaiden, posted off. Out of seven of us only H., myself,

and Aunt

Judy are left. The absence of Reeney will not be the one least

noted. She

was as precious an imp as any Topsy ever was. Her tricks were

endless and

her innocence of them amazing. When sent out to bring in eggs she

would

take them from nests where hens were hatching, and embryo chickens

would

be served up at breakfast, while Reeney stood by grinning to see

them

opened; but when accused she was imperturbable. "Laws, Mis' L., I

nebber

done bin nigh dem hens. Mis' Annie, you can go count dem dere

eggs." That

when counted they were found minus the number she had brought had

no

effect on her stolid denial. H. has plenty to do finishing the

garden all

by himself, but the time rather drags for me.

April 13, 1862. — This morning I was sewing up a rent in

H.'s

garden-coat, when Aunt Judy rushed in.

"Laws! Mis' L., here's Mr. Max and Mis' Annie done come back!" A

buggy was

coming up with Max, Annie, and Reeney.

"Well, is the war over?" I asked.

"Oh, I got sick!" replied our returned soldier, getting slowly

out of the

buggy.

He was very thin and pale, and explained that he took a severe

cold almost

at once, had a mild attack of pneumonia, and the surgeon got him

his

discharge as unfit for service. He succeeded in reaching Annie,

and a few

days of good care made him strong enough to travel back home.

"I suppose, H., you've heard that Island No. 10 is gone?"

Yes, we heard that much, but Max had the particulars, and an

exciting talk

followed. At night H. said to me, "G., New Orleans will be the

next to go,

you'll see, and I want to get there first; this stagnation here

will kill

me."

April 28, 1862. — This evening has been very lovely, but

full of a sad

disappointment. H. invited me to drive. As we turned homeward he

said:

"Well, my arrangements are completed. You can begin to pack your

trunks

to-morrow, and I shall have a talk with Max."

Mr. R. and Annie were sitting on the gallery as I ran up the

steps.

"Heard the news?" they cried.

"No! What news?"

"New Orleans is taken! All the boats have been run up the river

to save

them. No more mails."

How little they knew what plans of ours this dashed away. But our

disappointment is truly an infinitesimal drop in the great waves

of

triumph and despair surging to-night in thousands of hearts.

April 30. — The last two weeks have glided quietly away

without incident

except the arrival of new neighbors — Dr. Y., his wife, two

children, and

servants. That a professional man prospering in Vicksburg should

come now

to settle in this retired place looks queer. Max said:

"H., that man has come here to hide from the conscript officers.

He has

brought no end of provisions, and is here for the war. He has

chosen well,

for this county is so cleaned of men it won't pay to send the

conscript

officers here."

Our stores are diminishing and cannot be replenished from

without;

ingenuity and labor must evoke them. We have a fine garden in

growth,

plenty of chickens, and hives of bees to furnish honey in lieu of

sugar.

A good deal of salt meat has been stored in the smoke-house, and,

with

fish in the lake, we expect to keep the wolf from the door. The

season for

game is about over, but an occasional squirrel or duck comes to

the

larder, though the question of ammunition has to be considered.

What we

have may be all we can have, if the war last five years longer;

and they

say they are prepared to hold out till the crack of doom. Food,

however,

is not the only want. I never realized before the varied needs of

civilization. Every day something is "out." Last week but two bars

of soap

remained, so we began to save bones and ashes. Annie said: "Now,

if we

only had some china-berry trees here we shouldn't need any other

grease.

They are making splendid soap at Vicksburg with china-balls. They

just put

the berries into the lye and it eats them right up and makes a

fine soap."

I did long for some china-berries to make this experiment. H. had

laid in

what seemed a good supply of kerosene, but it is nearly gone, and

we are

down to two candles kept for an emergency. Annie brought a receipt

from

Natchez for making candles of rosin and wax, and with great

forethought

brought also the wick and rosin. So yesterday we tried making

candles. "We

had no molds, but Annie said the latest style in Natchez was to

make a

waxen rope by dipping, then wrap it round a corn-cob. But H. cut

smooth

blocks of wood about four inches square, into which he set a

polished

cylinder about four inches high. The waxen ropes were coiled round

the

cylinder like a serpent, with the head raised about two inches; as

the

light burned down to the cylinder, more of the rope was unwound.

To-day

the vinegar was found to be all gone and we have started to make

some. For

tyros we succeed pretty well."

VIII.

DROWNED OUT AND STARVED OUT.

May 9, 1862. — A great misfortune has come upon us all. For

several days

every one has been uneasy about the unusual rise of the

Mississippi and

about a rumor that the Federal forces had cut levees above to

swamp the

country. There is a slight levee back of the village, and H. went

yesterday to examine it. It looked strong and we hoped for the

best. About

dawn this morning a strange gurgle woke me. It had a pleasing,

lulling

effect. I could not fully rouse at first, but curiosity conquered

at last,

and I called H.

"Listen to that running water; what is it?" He sprung up,

listened a

second, and shouted: "Max, get up! The water is on us!" They both

rushed

off to the lake for the

skiff.

The levee had not broken. The water

was

running clean over it and through the garden fence so rapidly that

by the

time I dressed and got outside Max was paddling the pirogue they

had

brought in among the pea-vines, gathering all the ripe peas left

above the

water. We had enjoyed one mess and he vowed we should have

another.

H. was busy nailing a raft together while he had a dry place to

stand on.

Annie and I, with Reeney, had to secure the chickens, and the back

piazza

was given up to them. By the time a hasty breakfast was eaten the

water

was in the kitchen. The stove and everything there had to be put

up in the

dining-room. Aunt Judy and Reeney had likewise to move into the

house,

their floor also being covered with water. The raft had to be

floated to

the store-house and a platform built, on which everything was

elevated. At

evening we looked round and counted the cost. The garden was

utterly gone.

Last evening we had walked round the strawberry beds that fringed

the

whole acre and tasted a few just ripe. The hives were swamped.

Many of the

chickens were drowned. Sancho had been sent to high ground where

he could

get grass. In the village every green thing was swept away. Yet we

were

better off than many others; for this house, being raised, we have

escaped

the water indoors. It just laves the edge of the galleries.

May 26, 1862. — During the past week we have lived somewhat

like

Venetians, with a boat at front steps and a raft at the back.

Sunday H.

and I took skiff to church. The clergyman, who is also tutor at a

planter's across the lake, preached to the few who had arrived in

skiffs.

We shall not try it again, it is so troublesome getting in and out

at the

court-house steps. The imprisonment is hard to endure. It

threatened to

make me really ill, so every evening H. lays a thick wrap in the

pirogue,

I sit on it and we row off to the ridge of dry land running along

the

lake-shore and branching off to a strip of woods also out of

water. Here

we disembark and march up and down till dusk. A great deal of the

wood got

wet and has to be laid out to dry on the galleries, with clothing,

and

everything that must be dried. One's own trials are intensified by

the

worse suffering around that we can do nothing to relieve.

Max has a puppy named after General Price. The gentlemen had both

gone up

town yesterday in the skiff when Annie and I heard little Price's

despairing cries from under the house, and we got on the raft to

find and

save him. We wore light morning dresses and slippers, for shoes

are

becoming precious. Annie donned a Shaker and I a broad hat. We got

the

raft pushed out to the center of the grounds opposite the house

and could

see Price clinging to a post; the next move must be to navigate

the raft

up to the side of the house and reach for Price. It sounds easy;

but poke

around with our poles as wildly or as scientifically as we might,

the raft

would not budge. The noonday sun was blazing right overhead and

the muddy

water running all over slippered feet and dainty dresses. How long

we

staid praying for rescue, yet wincing already at the laugh that

would come

with it, I shall never know. It seemed like a day before the

welcome boat

and the "Ha, ha!" of H. and Max were heard. The confinement tells

severely

on all the animal life about us. Half the chickens are dead and

the other

half sick.

The days drag slowly. We have to depend mainly on books to

relieve the

tedium, for we have no piano; none of us like cards; we are very

poor

chess-players, and the chess-set is incomplete. When we gather

round the

one lamp — we dare not light any more — each one exchanges the gems of

thought or mirthful ideas he finds. Frequently the gnats and the

mosquitoes are so bad we cannot read at all. This evening, till a

strong

breeze blew them away, they were intolerable. Aunt Judy goes about

in a

dignified silence, too full for words, only asking two or three

times,

"W'at I dun tole you fum de fust?" The food is a trial. This

evening the

snaky candles lighted the glass and silver on the supper-table

with a pale

gleam and disclosed a frugal supper indeed — tea without milk (for

all the

cows are gone), honey, and bread. A faint ray twinkled on the

water

swishing against the house and stretching away into the dark

woods. It

looked like civilization and barbarism met together. Just as we

sat down

to it, some one passing in a boat shouted that Confederates and

Federals

were fighting at Vicksburg.

Monday, June 2, 1862. — On last Friday morning, just three

weeks from the

day the water rose, signs of its falling began. Yesterday the

ground

appeared, and a hard rain coming down at the same time washed off

much of

the unwholesome débris. To-day is fine, and we went out without a

boat for

a long walk.

June 13. — Since the water ran off, we have, of course, been

attacked by

swamp fever. H. succumbed first, then Annie, Max next, and then I.

Luckily, the new Dr. Y. had brought quinine with him, and we took

heroic

doses. Such fever never burned in my veins before or sapped

strength so

rapidly, though probably the want of good food was a factor. The

two or

three other professional men have left. Dr. Y. alone remains. The

roads

now being dry enough, H. and Max started on horseback, in

different

directions, to make an exhaustive search for supplies. H. got back

this

evening with no supplies.

June 15, 1862. — Max got back to-day. He started right off

again to cross

the lake and interview the planters on that side, for they had not

suffered from overflow.

June 16. — Max got back this morning. H. and he were in the

parlor

talking and examining maps together till dinner-time. When that

was over

they laid the matter before us. To buy provisions had proved

impossible.

The planters across the lake had decided to issue rations of

corn-meal and

peas to the villagers whose men had all gone to war, but they

utterly

refused to sell anything. "They said to me," said Max, "' We will

not see

your family starve, Mr. K.; but with such numbers of slaves and

the

village poor to feed, we can spare nothing for sale.'" "Well, of

course,"

said H., "we do not purpose to stay here and live on charity

rations. We

must leave the place at all hazards. We have studied out every

route and

made inquiries everywhere we went. We shall have to go down the

Mississippi in an open boat as far as Fetler's Landing (on the

eastern

bank). There we can cross by land and put the boat into Steele's

Bayou,

pass thence to the Yazoo River, from there to Chickasaw Bayou,

into

McNutt's Lake, and land near my uncle's in Warren County."

June 20, 1862. — As soon as our intended departure was

announced, we

were besieged by requests for all sorts of things wanted in every

family — pins, matches, gunpowder, and ink. One of the last cases H.

and

Max had before the stay-law stopped legal business was the

settlement of

an estate that included a country store. The heirs had paid in

chattels of

the store. These had remained packed in the office. The main

contents of

the cases were hardware; but we found treasure indeed — a keg of

powder, a

case of matches, a paper of pins, a bottle of ink. Red ink is now

made out

of poke-berries. Pins are made by capping thorns with sealing-wax,

or

using them as nature made them. These were articles money could

not get

for us. We would give our friends a few matches to save for the

hour of

tribulation. The paper of pins we divided evenly, and filled a

bank-box

each with the matches. H. filled a tight tin case apiece with

powder for

Max and himself and sold the rest, as we could not carry any more

on such

a trip. Those who did not hear of this in time offered fabulous

prices

afterwards for a single pound. But money has not its old

attractions. Our

preparations were delayed by Aunt Judy falling sick of swamp

fever.

Friday, June 27. — As soon as the cook was up again, we

resumed

preparations. We put all the clothing in order and had it nicely

done up

with the last of the soap and starch. "I wonder," said Annie,

"when I

shall ever have nicely starched clothes after these? They had no

starch in

Natchez or Vicksburg when I was there." We are now furbishing up

dresses

suitable for such rough summer travel. While we sat at work

yesterday the

quiet of the clear, calm noon was broken by a low, continuous roar

like

distant thunder. To-day we are told it was probably cannon at

Vicksburg.

This is a great distance, I think, to have heard it — over a hundred

miles.

H. and Max have bought a large yawl and are busy on the lake bank

repairing it and fitting it with lockers. Aunt Judy's master has

been

notified when to send for her; a home for the cat Jeff has been

engaged;

Price is dead, and Sancho sold. Nearly all the furniture is

disposed of,

except things valued from association, which will be packed in

H.'s office

and left with some one likely to stay through the war. It is

hardest to

leave the books.

Tuesday, July 8, 1862. — We start to-morrow. Packing the

trunks was a

problem. Annie and I are allowed one large trunk apiece, the

gentlemen a

smaller one each, and we a light carpet-sack apiece for toilet

articles. I

arrived with six trunks and leave with one! We went over

everything

carefully twice, rejecting, trying to shake off the bonds of

custom and

get down to primitive needs. At last we made a judicious

selection.

Everything old or worn was left; everything merely ornamental,

except good

lace, which was light. Gossamer evening dresses were all left. I

calculated on taking two or three books that would bear the most

reading

if we were again shut up where none could be had, and so, of

course, took

Shakspere first. Here I was interrupted to go and pay a farewell

visit,

and when we returned Max had packed and nailed the cases of books

to be

left. Chance thus limited my choice to those that happened to be

in my

room — "Paradise Lost," the "Arabian Nights," a volume of Macaulay's

History that I was reading, and my prayer-book. To-day the

provisions for

the trip were cooked: the last of the flour was made into large

loaves of

bread; a ham and several dozen eggs were boiled; the few chickens

that

have survived the overflow were fried; the last of the coffee was

parched

and ground; and the modicum of the tea was well corked up. Our

friends

across the lake added a jar of butter and two of preserves. H.

rode off to

X. after dinner to conclude some business there, and I sat down

before a

table to tie bundles of things to be left. The sunset glowed and

faded and

the quiet evening came on calm and starry. I sat by the window

till

evening deepened into night, and as the moon rose I still looked a

reluctant farewell to the lovely lake and the grand woods, till

the sound

of H.'s horse at the gate broke the spell.

IX.

HOMELESS AND SHELTERLESS.

Thursday, July 10, 1862. ( —— Plantation.) — Yesterday

about 4 o'clock

we walked to the lake and embarked. Provisions and utensils were

packed in

the lockers, and a large trunk was stowed at each end. The

blankets and

cushions were placed against one of them, and Annie and I sat on

them

Turkish fashion. Near the center the two smaller trunks made a

place for

Reeney. Max and H. were to take turns at the rudder and oars. The

last

word was a fervent God-speed from Mr. E., who is left in charge of

all our

affairs. We believe him to be a Union man, but have never spoken

of it to

him. We were gloomy enough crossing the lake, for it was evident

the

heavily laden boat would be difficult to manage. Last night we

staid at

this plantation, and from the window of my room I see the men

unloading

the boat to place it on the cart, which a team of oxen will haul

to the

river. These hospitable people are kindness itself, till you

mention the

war.

Saturday, July 12, 1862. (Under a cotton-shed on the bank of

the

Mississippi River.) — Thursday was a lovely day, and the sight

of the

broad river exhilarating. The negroes launched and reloaded the

boat, and

when we had paid them and spoken good-bye to them we felt we were

really

off. Every one had said that if we kept in the current the boat

would

almost go of itself, but in fact the current seemed to throw it

about, and

hard pulling was necessary. The heat of the sun was very severe,

and it

proved impossible to use an umbrella or any kind of shade, as it

made

steering more difficult. Snags and floating timbers were very

troublesome.

Twice we hurried up to the bank out of the way of passing

gunboats, but

they took no notice of us. When we got thirsty, it was found that

Max had

set the jug of water in the shade of a tree and left it there. We

must dip

up the river water or go without. When it got too dark to travel

safely we

disembarked. Reeney gathered wood, made a fire and some tea, and

we had a

good supper. We then divided, H. and I remaining to watch the

boat, Max

and Annie on shore. She hung up a mosquito-bar to the trees and

went to

bed comfortably. In the boat the mosquitoes were horrible, but I

fell

asleep and slept till voices on the bank woke me. Annie was

wandering

disconsolate round her bed, and when I asked the trouble, said,

"Oh, I

can't sleep there! I found a toad and a lizard in the bed." When

dropping

off again, H. woke me to say he was very sick; he thought it was

from

drinking the river water. With difficulty I got a trunk opened to

find

some medicine. While doing so a gunboat loomed up vast and gloomy,

and we

gave each other a good fright. Our voices doubtless reached her,

for

instantly every one of her lights disappeared and she ran for a

few

minutes along the opposite bank. We momently expected a shell as a

feeler.

At dawn next morning we made coffee and a hasty breakfast, fixed

up as

well as we could in our sylvan dressing-rooms, and pushed on, for

it is

settled that traveling between eleven and two will have to be

given up

unless we want to be roasted alive. H. grew worse. He suffered

terribly,

and the rest of us as much to see him pulling in such a state of

exhaustion. Max would not trust either of us to steer. About

eleven we

reached the landing of a plantation. Max walked up to the house

and

returned with the owner, an old gentleman living alone with his

slaves.

The housekeeper, a young colored girl, could not be surpassed in

her

graceful efforts to make us comfortable and anticipate every want.

I was

so anxious about H. that I remember nothing except that the cold

drinking-water taken from a cistern beneath the building, into

which only

the winter rains were allowed to fall, was like an elixir. They

offered

luscious peaches that, with such water, were nectar and ambrosia

to our

parched lips. At night the housekeeper said she was sorry they had

no

mosquito-bars ready and hoped the mosquitoes would not be thick,

but they

came out in legions. I knew that on sleep that night depended

recovery or

illness for H. and all possibility of proceeding next day. So I

sat up

fanning away mosquitoes that he might sleep, toppling over now and

then on

the pillows till roused by his stirring. I contrived to keep this

up till,

as the chill before dawn came, they abated and I got a short

sleep. Then,

with the aid of cold water, a fresh toilet, and a good breakfast,

I braced

up for another day's baking in the boat.

[If I had been well and strong as usual the discomforts of such a

journey

would not have seemed so much to me; but I was still weak from the

effects

of the fever, and annoyed by a worrying toothache which there had

been no

dentist to rid me of in our

village.]

Having paid and dismissed the boat's watchman, we started and

traveled

till eleven to-day, when we stopped at this cotton-shed. When our

dais was

spread and lunch laid out in the cool breeze, it seemed a blessed

spot. A

good many negroes came offering chickens and milk in exchange for

tobacco, which we had not. We bought some milk with money.

A United States transport just now steamed by and the men on the

guards

cheered and waved to us. We all replied but Annie. Even Max was

surprised

into an answering cheer, and I waved my handkerchief with a very

full

heart as the dear old flag we have not seen for so long floated

by; but

Annie turned her back.

Sunday, July 13, 1862. (Under a tree on the east bank of the

Mississippi.) — Late on Saturday evening we reached a

plantation whose

owner invited us to spend the night at his house. What a

delightful thing

is courtesy! The first tone of our host's welcome indicated the

true

gentleman. We never leave the oars with the watchman; Max takes

those,

Annie and I each take a band-box, H. takes my carpet-sack, and

Reeney

brings up the rear with Annie's. It is a funny procession. Mr.

B.'s family

were absent, and as we sat on the gallery talking it needed only a

few

minutes to show this was a "Union man." His home was elegant and

tasteful,

but even here there was neither tea nor coffee.

About eleven we stopped here in this shady place. While eating

lunch the

negroes again came imploring for tobacco. Soon an invitation came

from the

house for us to come and rest. We gratefully accepted, but found

the idea

of rest for warm, tired travelers was for us to sit in the parlor

on stiff

chairs while the whole family trooped in, cool and clean in fresh

toilets,

to stare and question. We soon returned to the trees; however,

they

kindly offered corn-meal pound-cake and beer, which were

excellent. If we

reach Fetler's Landing to-night, the Mississippi-River part of the

journey

is concluded. Eight gunboats and one transport have passed us.

Getting out

of their way has been troublesome. Our gentlemen's hands are badly

blistered.

Tuesday, July l5, 1862. — Sunday night about ten we reached

the place

where, according to our map, Steele's Bayou comes nearest to the

Mississippi, and where the landing should be, but when we climbed

the

steep bank there was no sign, of habitation. Max walked off into

the woods

on a search, and was gone so long we feared he had lost his way.

He could

find no road. H. suggested shouting and both began. At last a

distant

halloo replied, and by cries the answerer was guided to us. A

negro said

"Who are you? What do you want?" "Travelers seeking shelter for

the

night." He came forward and said that was the right place, his

master kept

the landing, and he would watch the boat for five dollars. He

showed the

road, and said his master's house was one mile off and another

house two

miles. We mistook and went to the one two miles off. There a

legion of

dogs rushed at us, and several great, tall, black fellows

surrounded us

till the master was roused. He put his head through the window and

said, — "I'll let nobody in. The Yankees have been here and took

twenty-five of my negroes to work on their fortifications, and

I've no

beds nor anything for anybody." At 1 o'clock we reached Mr.

Fetler's, who

was pleasant, and said we should have the best he had. The bed

into whose

grateful softness I sank was piled with mattresses to within two

or three

feet of the ceiling, and, with no step-ladder, getting in and out

was a

problem. This morning we noticed the high-water mark, four feet

above the

lower floor. Mrs. Fetler said they had lived up-stairs several

weeks.

X.

FRIGHTS AND PERILS IN STEELE'S BAYOU.

Wednesday, July 16, 1862. (Under a tree on the bank of

Steele's

Bayou.) — Early this morning our boat was taken out of the

Mississippi and

put on Mr. Fetler's ox-cart. After breakfast we followed on foot.

The walk

in the woods was so delightful that all were disappointed when a

silvery

gleam through the trees showed the bayou sweeping along, full to

the

banks, with dense forest trees almost meeting over it. The boat

was

launched, calked, and reloaded, and we were off again. Towards

noon the

sound of distant cannon began to echo around, probably from

Vicksburg

again. About the same time we began to encounter rafts. To get

around them

required us to push through brush so thick that we had to lie down

in the

boat. The banks were steep and the land on each side a bog. About

1

o'clock we reached this clear space with dry shelving banks and

disembarked to eat lunch. To our surprise a neatly dressed woman

came

tripping down the declivity bringing a basket. She said she lived

above

and had seen our boat. Her husband was in the army, and we were

the first

white people she had talked to for a long while. She offered some

corn-meal pound-cake and beer, and as she climbed back told us to

"look

out for the rapids." H. is putting the boat in order for our start

and

says she is waving good-bye from the bluff above.

Thursday, July 17, 1862. (On a raft in Steele's Bayou.) — Yesterday

we

went on nicely awhile and at afternoon came to a strange region of

rafts,

extending about three miles, on which persons were living. Many

saluted

us, saying they had run away from Vicksburg at the first attempt

of the

fleet to shell it. On one of these rafts, about

twelve feet

square,

bagging had been hung up to form three sides of a tent. A bed was

in one

corner, and on a low chair, with her provisions in jars and boxes

grouped

round her, sat an old woman feeding a lot of chickens. They were

strutting

about oblivious to the inconveniences of war, and she looked

serenely at

ease.

Having moonlight, we had intended to travel till late. But about

ten

o'clock, the boat beginning to go with great speed, H., who was

steering;

called to Max:

"Don't row so fast; we may run against something."

"I'm hardly pulling at all."

"Then we're in what she called the rapids!"

The stream seemed indeed to slope downward, and in a minute a

dark line

was visible ahead. Max tried to turn, but could not, and in a

second more

we dashed against this immense raft, only saved from breaking up

by the

men's quickness. We got out upon it and ate supper. Then, as the

boat was

leaking and the current swinging it against the raft, H. and Max

thought

it safer to watch all night, but told us to go to sleep. It was a

strange

spot to sleep in — a raft in the middle of a boiling stream, with a

wilderness stretching on either side. The moon made ghostly

shadows and

showed H., sitting still as a ghost, in the stern of the boat,

while

mingled with the gurgle of the water round the raft beneath was

the boom

of cannon in the air, solemnly breaking the silence of night. It

drizzled

now and then, and the mosquitoes swarmed over us. My fan and

umbrella had

been knocked overboard, so I had no weapon against them. Fatigue,

however,

overcomes everything, and I contrived to sleep.

H. roused us at dawn. Reeney found light-wood enough on the raft

to make a

good fire for coffee, which never tasted better. Then all hands

assisted

in unloading; a rope was fastened to the boat, Max got in, H. held

the

rope on the raft, and, by much pulling and pushing, it was forced

through

a narrow passage to the farther side. Here it had to be calked,

and while

that was being done we improvised a dressing-room in the shadow of

our big

trunks. (During the trip I had to keep the time, therefore

properly to

secure belt and watch was always an anxious part of my toilet.)

The boat

is now repacked, and while Annie and Reeney are washing cups I

have

scribbled, wishing much that mine were the hand of an artist.

Friday morning, July 18, 1862. (House of Col. K., on Yazoo

River.) — After leaving the raft yesterday all went well till

noon, when

we came to a narrow place where an immense tree lay clear across

the

stream. It seemed the insurmountable obstacle at last. We sat

despairing

what to do, when a man appeared beside us in a pirogue. So sudden,

so

silent was his arrival that we were thrilled with surprise. He

said if we

had a hatchet he could help us. His fairy bark floated in among

the

branches like a bubble, and he soon chopped a path for us, and was

delighted to get some matches in return. He said the cannon we

heard

yesterday were in an engagement with the ram Arkansas,

which ran out of

the Yazoo that morning. We did not stop for dinner to-day, but ate

a hasty

lunch in the boat, after which nothing but a small piece of bread

was

left. About two we reached the forks, one of which ran to the

Yazoo, the

other to the Old River. Max said the right fork was our road; H.

said the

left, that there was an error in Max's map; but Max steered into

the right

fork. After pulling about three miles he admitted his mistake and

turned

back; but I shall never forget Old River. It was the vision of a

drowned

world, an illimitable waste of dead waters, stretching into a

great,

silent, desolate forest. A horror chilled me and I begged them to

row fast

out of that terrible place.

Just as we turned into the right way, down came the rain so hard

and fast

we had to stop on the bank. It defied trees or umbrellas and

nearly took

away the breath. The boat began to fill, and all five of us had to

bail

as fast as possible for the half-hour the sheet of water was

pouring down.

As it abated a cold breeze sprung up that, striking our wet

clothes,

chilled us to the bone. All were shivering and blue — no, I was

green.

Before leaving Mr. Fetler's Wednesday morning I had donned a

dark-green

calico. I wiped my face with a handkerchief out of my pocket, and

face and

hands were all dyed a deep green. When Annie turned round and

looked at me

she screamed and I realized how I looked; but she was not much

better, for

of all dejected things wet feathers are the worst, and the plumes

in her

hat were painful.

About five we reached Colonel K.'s house, right where Steele's

Bayou

empties into the Yazoo. We had both to be fairly dragged out of

the boat,

so cramped and weighted were we by wet skirts. The family were

absent, and

the house was headquarters for a squad of Confederate cavalry,

which was

also absent. The old colored housekeeper received us kindly and

lighted

fires in our rooms to dry the clothing. My trunk had got cracked

on top,

and all the clothing to be got at was wet. H. had dropped his in

the river