THE CROSSING

BOOK I.

the borderland

I WAS born under the Blue Ridge, and under that side which is

blue in the evening light, in a wild land of game and forest and

rushing waters. There, on the borders of a creek that runs into

the Yadkin River, in a cabin that was chinked with red mud, I came

into the world a subject of King George the Third, in that part of

his realm known as the province of North Carolina.

The cabin reeked of corn-pone and bacon, and the odor of pelts.

It had two shakedowns, on one of which I slept under a bearskin. A

rough stone chimney was reared outside, and the fireplace was as

long as my father was tall. There was a crane in it, and a bake

kettle; and over it great buckhorns held my father’s rifle when it

was not in use. On other horns hung jerked bear’s meat and venison

hams, and gourds for drinking cups, and bags of seed, and my

father’s best hunting shirt; also, in a neglected corner, several

articles of woman’s attire from pegs. These once belonged to my

mother. Among them was a gown of silk, of a fine, faded pattern,

over which I was wont to speculate. The women at the Cross-Roads,

twelve miles away, were dressed in coarse butternut wool and huge

sunbonnets. But when I questioned my father on these matters he

would give me no answers.

My father was — how shall I say what he was? To this day I can

only surmise many things of him. He was a Scotchman born, and I

know now that he had a slight Scotch accent. At the time of which

I write, my early childhood, he was a frontiersman and hunter. I

can see him now, with his hunting shirt and leggings and

moccasins; his powder horn, engraved with wondrous scenes; his

bullet pouch and tomahawk and hunting knife. He was a tall, lean

man with a strange, sad face. And he talked little save when he

drank too many “horns,” as they were called in that country. These

lapses of my father’s were a perpetual source of wonder to

me, — and, I must say, of delight. They occurred only when a passing

traveller who hit his fancy chanced that way, or, what was almost

as rare, a neighbor. Many a winter night I have lain awake under

the skins, listening to a flow of language that held me

spellbound, though I understood scarce a word of it.

“Virtuous and vicious every man must be,

Few in the extreme, but all in a degree.”

The chance neighbor or traveller was no less struck with wonder.

And many the time have I heard the query, at the Cross-Roads and

elsewhere, “Whar Alec Trimble got his larnin’?”

The truth is, my father was an object of suspicion to the

frontiersmen. Even as a child I knew this, and resented it. He had

brought me up in solitude, and I was old for my age, learned in

some things far beyond my years, and ignorant of others I should

have known. I loved the man passionately. In the long winter

evenings, when the howl of wolves and “painters” rose as the wind

lulled, he taught me to read from the Bible and the “Pilgrim’s

Progress.” I can see his long, slim fingers on the page. They

seemed but ill fitted for the life he led.

The love of rhythmic language was somehow born into me, and

many’s the time I have held watch in the cabin day and night while

my father was away on his hunts, spelling out the verses that have

since become part of my life.

As I grew older I went with him into the mountains, often on his

back; and spent the nights in open camp with my little moccasins

drying at the blaze. So I learned to skin a bear, and fleece off

the fat for oil with my hunting knife; and cure a deerskin and

follow a trail. At seven I even shot the long rifle, with a rest.

I learned to endure cold and hunger and fatigue and to walk in

silence over the mountains, my father never saying a word for days

at a spell. And often, when he opened his mouth, it would be to

recite a verse of Pope’s in a way that moved me strangely. For a

poem is not a poem unless it be well spoken.

In the hot days of summer, over against the dark forest the

bright green of our little patch of Indian corn rippled in the

wind. And towards night I would often sit watching the deep blue

of the mountain wall and dream of the mysteries of the land that

lay beyond. And by chance, one evening as I sat thus, my father

reading in the twilight, a man stood before us. So silently had he

come up the path leading from the brook that we had not heard him.

Presently my father looked up from his book, but did not rise. As

for me, I had been staring for some time in astonishment, for he

was a better-looking man than I had ever seen. He wore a deerskin

hunting shirt dyed black, but, in place of a coonskin cap with the

tail hanging down, a hat. His long rifle rested on the ground, and

he held a roan horse by the bridle.

“Howdy, neighbor?” said he.

I recall a fear that my father would not fancy him. In such

cases he would give a stranger food, and leave him to himself. My

father’s whims were past understanding. But he got up.

“Good evening,” said he.

The visitor looked a little surprised, as I had seen many do, at

my father’s accent.

“Neighbor,” said he, “kin you keep me over night?”

“Come in,” said my father.

We sat down to our supper of corn and beans and venison, of all

of which our guest ate sparingly. He, too, was a silent man, and

scarcely a word was spoken during the meal. Several times he

looked at me with such a kindly expression in his blue eyes, a

trace of a smile around his broad mouth, that I wished he might

stay with us always. But once, when my father said something about

Indians, the eyes grew hard as flint. It was then I remarked, with

a boy’s wonder, that despite his dark hair he had yellow eyebrows.

After supper the two men sat on the log step, while I set about

the task of skinning the deer my father had shot that day.

Presently I felt a heavy hand on my shoulder.

“What’s your name, lad?” he said.

I told him Davy.

“Davy, I’ll larn ye a trick worth a little time,” said he,

whipping out a knife. In a trice the red carcass hung between the

forked stakes, while I stood with my mouth open. He turned to me

and laughed gently.

“Some day you’ll cross the mountains and skin twenty of an

evening,” he said. “Ye’ll make a woodsman sure. You’ve got the

eye, and the hand.”

This little piece of praise from him made me hot all over.

“Game rare?” said he to my father.

“None sae good, now,” said my father.

“I reckon not. My cabin’s on Beaver Creek some forty mile above,

and game’s going there, too.”

“Settlements,” said my father. But presently, after a few whiffs

of his pipe, he added, “I hear fine things of this land across the

mountains, that the Indians call the Dark and Bluidy Ground.”

“And well named,” said the stranger.

“But a brave country,” said my father, “and all tramped down

with game. I hear that Daniel Boone and others have gone into it

and come back with marvellous tales. They tell me Boone was there

alone three months. He’s saething of a man. D’ye ken him?”

The ruddy face of the stranger grew ruddier still.

“My name’s Boone,” he said.

“What!” cried my father, “it wouldn’t be Daniel?”

“You’ve guessed it, I reckon.”

My father rose without a word, went into the cabin, and

immediately reappeared with a flask and a couple of gourds, one of

which he handed to our visitor.

“Tell me aboot it,” said he.

That was the fairy tale of my childhood. Far into the night I

lay on the dewy grass listening to Mr. Boone’s talk. It did not at

first flow in a steady stream, for he was not a garrulous man, but

my father’s questions presently fired his enthusiasm. I recall but

little of it, being so small a lad, but I crept closer and closer

until I could touch this superior being who had been beyond the

Wall. Marco Polo was no greater wonder to the Venetians than Boone

to me.

He spoke of leaving wife and children, and setting out for the

Unknown with other woodsmen. He told how, crossing over our blue

western wall into a valley beyond, they found a “Warrior’s Path”

through a gap across another range, and so down into the fairest

of promised lands. And as he talked he lost himself in the tale of

it, and the very quality of his voice changed. He told of a land

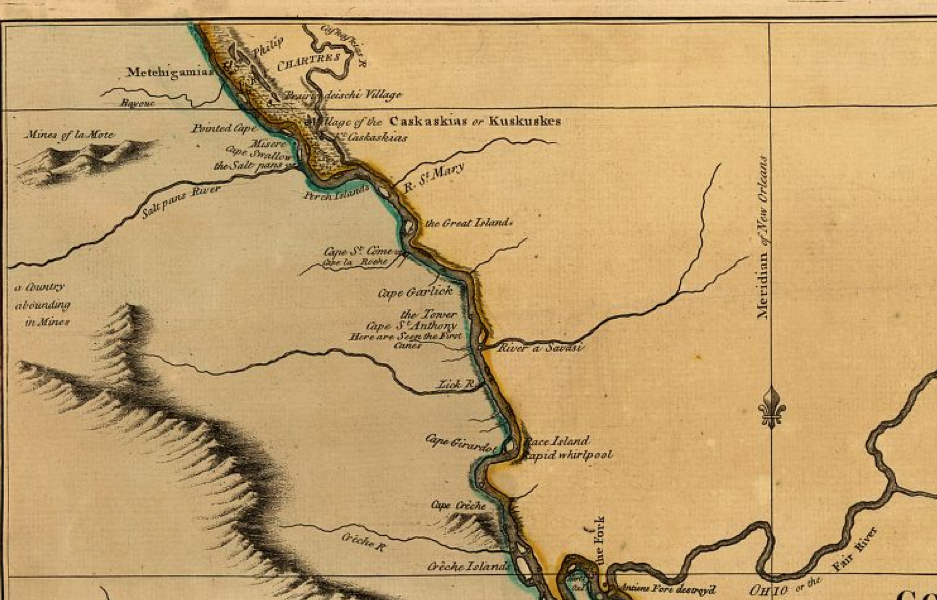

of wooded hill and pleasant vale, of clear water running over

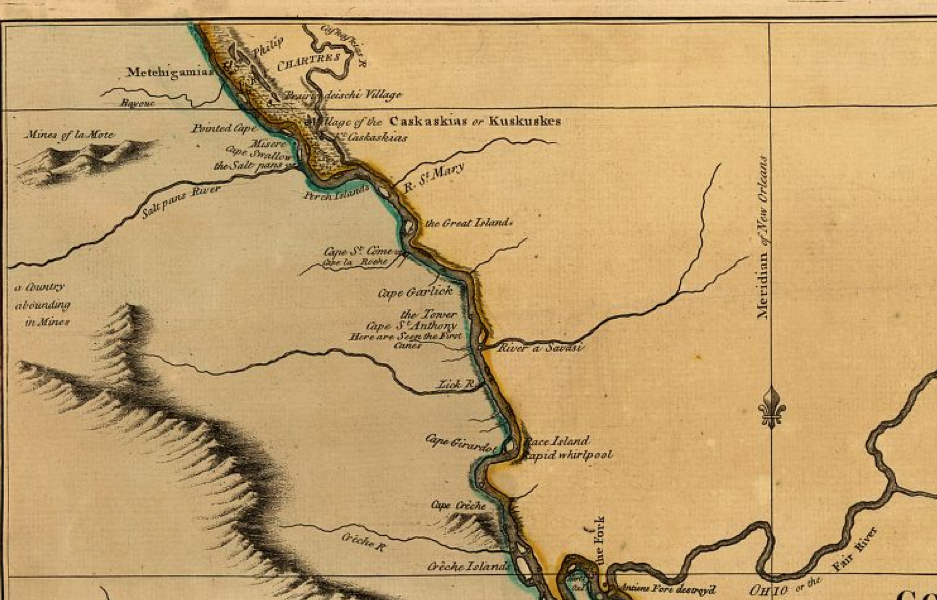

limestone down to the great river beyond, the Ohio — a land of

glades, the fields of which were pied with flowers of wondrous

beauty, where roamed the buffalo in countless thousands, where elk

and deer abounded, and turkeys and feathered game, and bear in the

tall brakes of cane. And, simply, he told how, when the others had

left him, he stayed for three months roaming the hills alone with

Nature herself.

“But did you no’ meet the Indians?” asked my father.

“I seed one fishing on a log once,” said our visitor, laughing,

“but he fell into the water. I reckon he was drowned.”

My father nodded comprehendingly, — even admiringly.

“And again!” said he.

“Wal,” said Mr. Boone, “we fell in with a war party of Shawnees

going back to their lands north of the great river. The critters

took away all we had. It was hard,” he added reflectively; “I had

staked my fortune on the venter, and we’d got enough skins to make

us rich. But, neighbor, there is land enough for you and me, as

black and rich as Canaan.”

“‘The Lord is my shepherd,’” said my father, lapsing into verse.

“‘The Lord is my shepherd. I shall not want. He leadeth me into

green pastures, and beside still waters.’”

For a time they were silent, each wrapped in his own thought,

while the crickets chirped and the frogs sang. From the distant

forest came the mournful hoot of an owl.

“And you are going back?” asked my father, presently.

“Aye, that I am. There are many families on the Yadkin below

going, too. And you, neighbor, you might come with us. Davy is the

boy that would thrive in that country.”

My father did not answer. It was late indeed when we lay down to

rest, and the night I spent between waking and dreaming of the

wonderland beyond the mountains, hoping against hope that my

father would go. The sun was just flooding the slopes when our

guest arose to leave, and my father bade him God-speed with a

heartiness that was rare to him. But, to my bitter regret, neither

spoke of my father’s going. Being a man of understanding, Mr.

Boone knew it were little use to press. He patted me on the head.

“You’re a wise lad, Davy,” said he. “I hope we shall meet

again.”

He mounted his roan and rode away down the slope, waving his

hand to us. And it was with a heavy heart that I went to feed our

white mare, whinnying for food in the lean-to.

CHAPTER II.

wars and rumors of wars

AND SO our life went on the same, but yet not the same. For I

had the Land of Promise to dream of, and as I went about my tasks

I conjured up in my mind pictures of its beauty. You will forgive

a backwoods boy, — self-centred, for lack of wider interest, and

with a little imagination. Bear hunting with my father, and an

occasional trip on the white mare twelve miles to the Cross-Roads

for salt and other necessaries, were the only diversions to break

the routine of my days. But at the Cross-Roads, too, they were

talking of Kaintuckee. For so the Land was called, the Dark and

Bloody Ground.

The next year came a war on the Frontier, waged by Lord Dunmore,

Governor of Virginia. Of this likewise I heard at the Cross-Roads,

though few from our part seemed to have gone to it. And I heard

there, for rumors spread over mountains, that men blazing in the

new land were in danger, and that my hero, Boone, was gone out to

save them. But in the autumn came tidings of a great battle far to

the north, and of the Indians suing for peace.

The next year came more tidings of a sort I did not understand.

I remember once bringing back from the Cross-Roads a crumpled

newspaper, which my father read again and again, and then folded

up and put in his pocket. He said nothing to me of these things.

But the next time I went to the Cross-Roads, the woman asked me: —

“Is your Pa for the Congress?”

“What’s that?” said I.

“I reckon he ain’t,” said the woman, tartly. I recall her dimly,

a slattern creature in a loose gown and bare feet, wife of the

storekeeper and wagoner, with a swarm of urchins about her. They

were all very natural to me thus. And I remember a battle with one

of these urchins in the briers, an affair which did not add to the

love of their family for ours. There was no money in that country,

and the store took our pelts in exchange for what we needed from

civilization. Once a month would I load these pelts on the white

mare, and make the journey by the path down the creek. At times I

met other settlers there, some of them not long from Ireland, with

the brogue still in their mouths. And again, I saw the wagoner

with his great canvas-covered wagon standing at the door, ready to

start for the town sixty miles away. ’Twas he brought the news of

this latest war.

One day I was surprised to see the wagoner riding up the path to

our cabin, crying out for my father, for he was a violent man. And

a violent scene followed. They remained for a long time within the

house, and when they came out the wagoner’s face was red with

rage. My father, too, was angry, but no more talkative than usual.

“Ye say ye’ll not help the Congress?” shouted the wagoner.

“I’ll not,” said my father.

“Ye’ll live to rue this day, Alec Trimble,” cried the man. “Ye

may think ye’re too fine for the likes of us, but there’s them in

the settlement that knows about ye.”

With that he flung himself on his horse, and rode away. But the

next time I went to the Cross-Roads the woman drove me away with

curses, and called me an aristocrat. Wearily I tramped back the

dozen miles up the creek, beside the mare, carrying my pelts with

me; stumbling on the stones, and scratched by the dry briers. For

it was autumn, the woods all red and yellow against the green of

the pines. I sat down beside the old beaver dam to gather courage

to tell my father. But he only smiled bitterly when he heard it.

Nor would he tell me what the word aristocrat meant.

That winter we spent without bacon, and our salt gave out at

Christmas. It was at this season, if I remember rightly, that we

had another visitor. He arrived about nightfall one gray day, his

horse jaded and cut, and he was dressed all in wool, with a great

coat wrapped about him, and high boots. This made me stare at him.

When my father drew back the bolt of the door he, too, stared and

fell back a step.

“Come in,” said he.

“D’ye ken me, Alec?” said the man.

He was a tall, spare man like my father, a Scotchman, but his

hair was in a cue.

“Come in, Duncan,” said my father, quietly. “Davy, run out for

wood.”

Loath as I was to go, I obeyed. As I came back dragging a log

behind me I heard them in argument, and in their talk there was

much about the Congress, and a woman named Flora Macdonald, and a

British fleet sailing southward.

“We’ll have two thousand Highlanders and more to meet the fleet.

And ye’ll sit at hame, in this hovel ye’ve made yeresel” (and he

glanced about disdainfully) “and no help the King?” He brought his

fist down on the pine boards.

“Ye did no help the King greatly at Culloden, Duncan,” said my

father, dryly.

Our visitor did not answer at once.

“The Yankee Rebels ’ll no help the House of Stuart,” said he,

presently. “And Hanover’s coom to stay. Are ye, too, a Rebel, Alec

Ritchie?”

I remember wondering why he said Ritchie.

“I’ll no take a hand in this fight,” answered my father.

And that was the end of it. The man left with scant ceremony, I

guiding him down the creek to the main trail. He did not open his

mouth until I parted with him.

“Puir Davy,” said he, and rode away in the night, for the moon

shone through the clouds.

I remember these things, I suppose, because I had nothing else

to think about. And the names stuck in my memory, intensified by

later events, until I began to write a diary.

And now I come to my travels. As the spring drew on I had had a

feeling that we could not live thus forever, with no market for

our pelts. And one day my father said to me abruptly: —

“Davy, we’ll be travelling.”

“Where?” I asked.

“Ye’ll ken soon enough,” said he. “We’ll go at crack o’ day.”

We went away in the wild dawn, leaving the cabin desolate. We

loaded the white mare with the pelts, and my father wore a woollen

suit like that of our Scotch visitor, which I had never seen

before. He had clubbed his hair. But, strangest of all, he carried

in a small parcel the silk gown that had been my mother’s. We had

scant other baggage.

We crossed the Yadkin at a ford, and climbing the hills to the

south of it we went down over stony traces, down and down, through

rain and sun; stopping at rude cabins or taverns, until we came

into the valley of another river. This I know now was the Catawba.

My memories of that ride are as misty as the spring weather in the

mountains. But presently the country began to open up into broad

fields, some of these abandoned to pines. And at last, splashing

through the stiff red clay that was up to the mare’s fetlocks, we

came to a place called Charlotte Town. What a day that was for me!

And how I gaped at the houses there, finer than any I had ever

dreamed of! That was my first sight of a town. And how I listened

open-mouthed to the gentlemen at the tavern! One I recall had a

fighting head with a lock awry, and a negro servant to wait on

him, and was the principal spokesman. He, too, was talking of war.

The Cherokees had risen on the western border. He was telling of

the massacre of a settlement, in no mild language.

“Sirs,” he cried, “the British have stirred the redskins to

this. Will you sit here while women and children are scalped, and

those devils” (he called them worse names) “Stuart and Cameron go

unpunished?”

My father got up from the corner where he sat, and stood beside

the man.

“I ken Alec Cameron,” said he.

The man looked at him with amazement.

“Ay?” said he, “I shouldn’t think you’d own it. Damn him,” he

cried, “if we catch him we’ll skin him alive.”

“I ken Cameron,” my father repeated, “and I’ll gang with you to

skin him alive.”

The man seized his hand and wrung it.

“But first I must be in Charlestown,” said my father.

The next morning we sold our pelts. And though the mare was

tired, we pushed southward, I behind the saddle. I had much to

think about, wondering what was to become of me while my father

went to skin Cameron. I had not the least doubt that he would do

it. The world is a storybook to a lad of nine, and the thought of

Charlestown filled me with a delight unspeakable. Perchance he

would leave me in Charlestown.

At nightfall we came into a settlement called the Waxhaws. And

there being no tavern there, and the mare being very jaded and the

roads heavy, we cast about for a place to sleep. The sunlight

slanting over the pine forest glistened on the pools in the wet

fields. And it so chanced that splashing across these, swinging a

milk-pail over his head, shouting at the top of his voice, was a

red-headed lad of my own age. My father hailed him, and he came

running towards us, still shouting, and vaulted the rails. He

stood before us, eying me with a most mischievous look in his blue

eyes, and dabbling in the red mud with his toes. I remember I

thought him a queer-looking boy. He was lanky, and he had a very

long face under his tousled hair.

My father asked him where he could spend the night.

“Wal,” said the boy, “I reckon Uncle Crawford might take you in.

And again he mightn’t.”

He ran ahead, still swinging the pail. And we, following, came

at length to a comfortable-looking farmhouse. As we stopped at the

doorway a stout, motherly woman filled it. She held her knitting

in her hand.

“You Andy!” she cried, “have you fetched the milk?”

Andy tried to look repentant.

“I declare I’ll tan you,” said the lady. “Git out this instant.

What rascality have you been in?”

“I fetched home visitors, Ma,” said Andy.

“Visitors!” cried the lady. “What ’ll your Uncle Crawford say?”

And she looked at us smiling, but with no great hostility.

“Pardon me, Madam,” said my father, “if we seem to intrude. But

my mare is tired, and we have nowhere to stay.”

Uncle Crawford did take us in. He was a man of substance in that

country, — a north of Ireland man by birth, if I remember right.

I went to bed with the red-headed boy, whose name was Andy

Jackson. I remember that his mother came into our little room

under the eaves and made Andy say his prayers, and me after him.

But when she was gone out, Andy stumped his toe getting into bed

in the dark and swore with a brilliancy and vehemence that

astonished me.

It was some hours before we went to sleep, he plying me with

questions about my life, which seemed to interest him greatly, and

I returning in kind.

“My Pa’s dead,” said Andy. “He came from a part of Ireland where

they are all weavers. We’re kinder poor relations here. Aunt

Crawford’s sick, and Ma keeps house. But Uncle Crawford’s good,

an’ lets me go to Charlotte Town with him sometimes.”

I recall that he also boasted some about his big brothers, who

were away just then.

Andy was up betimes in the morning, to see us start. But we

didn’t start, because Mr. Crawford insisted that the white mare

should have a half day’s rest. Andy, being hustled off unwillingly

to the “Old Field” school, made me go with him. He was a very

headstrong boy.

I was very anxious to see a school. This one was only a log

house in a poor, piny place, with a rabble of boys and girls

romping at the door. But when they saw us they stopped. Andy

jumped into the air, let out a war-whoop, and flung himself into

the midst, scattering them right and left, and knocking one boy

over and over. “I’m Billy Buck!” he cried. “I’m a hull regiment o’

Rangers. Let th’ Cherokees mind me!”

“Way for Sandy Andy!” cried the boys. “Where’d you get the new

boy, Sandy?”

“His name’s Davy,” said Andy, “and his Pa’s goin’ to fight the

Cherokees. He kin lick tarnation out’n any o’ you.”

Meanwhile I held back, never having been thrown with so many of

my own kind.

“He’s shot painters and b’ars,” said Andy. “An’ skinned ’em. Kin

you lick him, Smally? I reckon not.”

Now I had not come to the school for fighting. So I held back.

Fortunately for me, Smally held back also. But he tried skilful

tactics.

“He kin throw you, Sandy.”

Andy faced me in an instant.

“Kin you?” said he.

There was nothing to do but try, and in a few seconds we were

rolling on the ground, to the huge delight of Smally and the

others, Andy shouting all the while and swearing. We rolled and

rolled and rolled in the mud, until we both lost our breath, and

even Andy stopped swearing, for want of it. After a while the boys

were silent, and the thing became grim earnest. At length, by some

accident rather than my own strength, both his shoulders touched

the ground. I released him. But he was on his feet in an instant

and at me again like a wildcat.

“Andy won’t stay throwed,” shouted a boy. And before I knew it

he had my shoulders down in a puddle. Then I went for him, and

affairs were growing more serious than a wrestle, when Smally,

fancying himself safe, and no doubt having a grudge, shouted out: —

“Tell him he slobbers, Davy.”

Andy did slobber. But that was the end of me, and the beginning

of Smally. Andy left me instantly, not without an intimation that

he would come back, and proceeded to cover Smally with red clay

and blood. However, in the midst of this turmoil the schoolmaster

arrived, haled both into the schoolhouse, held court, and flogged

Andrew with considerable gusto. He pronounced these words

afterwards, with great solemnity: —

“Andrew Jackson, if I catch ye fightin’ once more, I’ll be

afther givin’ ye lave to lave the school.”

I parted from Andy at noon with real regret. He was the first

boy with whom I had ever had any intimacy. And I admired him:

chiefly, I fear, for his fluent use of profanity and his fighting

qualities. He was a merry lad, with a wondrous quick temper but a

good heart. And he seemed sorry to say good-by. He filled my

pockets with June apples — unripe, by the way — and told me to

remember him when I got till Charlestown.

I remembered him much longer than that, and usually with a shock

of surprise.

DOWN and down we went, crossing great rivers by ford and ferry,

until the hills flattened themselves and the country became a long

stretch of level, broken by the forests only; and I saw many

things I had not thought were on the earth. Once in a while I

caught glimpses of great red houses, with stately pillars, among

the trees. They put me in mind of the palaces in Bunyan, their

windows all golden in the morning sun; and as we jogged ahead, I

pondered on the delights within them. I saw gangs of negroes

plodding to work along the road, an overseer riding behind them

with his gun on his back; and there were whole cotton fields in

these domains blazing in primrose flower, — a new plant here, so my

father said. He was willing to talk on such subjects. But on

others, and especially our errand to Charlestown, he would say

nothing. And I knew better than to press him.

One day, as we were crossing a dike between rice swamps spread

with delicate green, I saw the white tops of wagons flashing in

the sun at the far end of it. We caught up with them, the wagoners

cracking their whips and swearing at the straining horses. And lo!

in front of the wagons was an army, — at least my boyish mind

magnified it to such. Men clad in homespun, perspiring and

spattered with mud, were straggling along the road by fours,

laughing and joking together. The officers rode, and many of these

had blue coats and buff waistcoats, — some the worse for wear. My

father was pushing the white mare into the ditch to ride by, when

one hailed him.

“Hullo, my man,” said he, “are you a friend to Congress?”

“I’m off to Charlestown to leave the lad,” said my father, “and

then to fight the Cherokees.”

“Good,” said the other. And then, “Where are you from?”

“Upper Yadkin,” answered my father. "And you?”

The officer, who was a young man, looked surprised. But then he

laughed pleasantly.

“We’re North Carolina troops, going to join Lee in Charlestown,”

said he. "The British are sending a fleet and regiments against

it.”

“Oh, aye,” said my father, and would have passed on. But he was

made to go before the Colonel, who plied him with many questions.

Then he gave us a paper and dismissed us.

We pursued our journey through the heat that shimmered up from

the road, pausing now and again in the shade of a wayside tree. At

times I thought I could bear the sun no longer. But towards four

o’clock of that day a great bank of yellow cloud rolled up,

darkening the earth save for a queer saffron light that stained

everything, and made our very faces yellow. And then a wind burst

out of the east with a high mournful note, as from a great flute

afar, filling the air with leaves and branches of trees. But it

bore, too, a savor that was new to me, — a salt savor, deep and

fresh, that I drew down into my lungs. And I knew that we were

near the ocean. Then came the rain, in great billows, as though

the ocean itself were upon us.

The next day we crossed a ferry on the Ashley River, and rode

down the sand of Charlestown neck. And my most vivid remembrance

is of the great trunks towering half a hundred feet in the air,

with a tassel of leaves at the top, which my father said were

palmettos. Something lay heavy on his mind. For I had grown to

know his moods by a sort of silent understanding. And when the

roofs and spires of the town shone over the foliage in the

afternoon sun, I felt him give a great sigh that was like a sob.

And how shall I describe the splendor of that city? The sandy

streets, and the gardens of flower and shade, heavy with the plant

odors; and the great houses with their galleries and porticos set

in the midst of the gardens, that I remember staring at wistfully.

But before long we came to a barricade fixed across the street,

and then to another. And presently, in an open space near a large

building, was a company of soldiers at drill.

It did not strike me as strange then that my father asked his

way of no man, but went to a little ordinary in a humbler part of

the town. After a modest meal in a corner of the public room, we

went out for a stroll. Then, from the wharves, I saw the bay

dotted with islands, their white sand sparkling in the evening

light, and fringed with strange trees, and beyond, of a deepening

blue, the ocean. And nearer, — greatest of all delights to

me, — riding on the swell was a fleet of ships. My father gazed at

them long and silently, his palm over his eyes.

“Men-o’-war from the old country, lad,” he said after a while.

"They’re a brave sight.”

“And why are they here?” I asked.

“They’ve come to fight,” said he, “and take the town again for

the King.”

It was twilight when we turned to go, and then I saw that many

of the warehouses along the wharves were heaps of ruins. My father

said this was that the town might be the better defended.

We bent our way towards one of the sandy streets where the great

houses were. And to my surprise we turned in at a gate, and up a

path leading to the high steps of one of these. Under the high

portico the door was open, but the house within was dark. My

father paused, and the hand he held to mine trembled. Then he

stepped across the threshold, and raising the big polished knocker

that hung on the panel, let it drop. The sound reverberated

through the house, and then stillness. And then, from within, a

shuffling sound, and an old negro came to the door. For an instant

he stood staring through the dusk, and broke into a cry.

“Marse Alec!” he said.

“Is your master at home?” said my father.

Without another word he led us through a deep hall, and out into

a gallery above the trees of a back garden, where a gentleman sat

smoking a long pipe. The old negro stopped in front of him.

“Marse John,” said he, his voice shaking, “heah’s Marse Alec

done come back.”

The gentleman got to his feet with a start. His pipe fell to the

floor, and the ashes scattered on the boards and lay glowing

there.

“Alec!” he cried, peering into my father’s face, “Alec! You’re

not dead.”

“John,” said my father, “can we talk here?”

“Good God!” said the gentleman, “you’re just the same. To think

of it — to think of it! Breed, a light in the drawing-room.”

There was no word spoken while the negro was gone, and the time

seemed very long. But at length he returned, a silver candlestick

in each hand.

“Careful,” cried the gentleman, petulantly, “you’ll drop them.”

He led the way into the house, and through the hall to a massive

door of mahogany with a silver door-knob. The grandeur of the

place awed me, and well it might. Boy-like, I was absorbed in

this. Our little mountain cabin would almost have gone into this

one room. The candles threw their flickering rays upward until

they danced on the high ceiling. Marvel of marvels, in the oval

left clear by the heavy, rounded cornice was a picture.

The negro set down the candles on the marble top of a table. But

the air of the room was heavy and close, and the gentleman went to

a window and flung it open. It came down instantly with a crash,

so that the panes rattled again.

“Curse these Rebels,” he shouted, “they’ve taken our window

weights to make bullets.”

Calling to the negro to pry open the window with a

walking-stick, he threw himself into a big, upholstered chair.

’Twas then I remarked the splendor of his clothes, which were

silk. And he wore a waistcoat all sewed with flowers. With a boy’s

intuition, I began to dislike him intensely.

“Damn the Rebels!” he began. "They’ve driven his Lordship away.

I hope his Majesty will hang every mother’s son of ’em. All

pleasure of life is gone, and they’ve folly enough to think they

can resist the fleet. And the worst of it is,” cried he, “the

worst of it is, I’m forced to smirk to them, and give good gold to

their government.” Seeing that my father did not answer, he asked:

"Have you joined the Highlanders? You were always for fighting.”

“I’m to be at Cherokee Ford on the twentieth,” said my father.

"We’re to scalp the redskins and Cameron, though ’tis not known.”

“Cameron!” shrieked the gentleman. "But that’s the other side,

man! Against his Majesty?”

“One side or t’other,” said my father, “’tis all one against

Alec Cameron.”

The gentleman looked at my father with something like terror in

his eyes.

“You’ll never forgive Cameron,” he said.

“I’ll no forgive anybody who does me a wrong,” said my father.

“And where have you been all these years, Alec?” he asked

presently. "Since you went off with — ”

“I’ve been in the mountains, leading a pure life,” said my

father. "And we’ll speak of nothing, if you please, that’s gone

by.”

“And what will you have me do?” said the gentleman, helplessly.

“Little enough,” said my father. "Keep the lad till I come

again. He’s quiet. He’ll no trouble you greatly. Davy, this is Mr.

Temple. You’re to stay with him till I come again.”

“Come here, lad,” said the gentleman, and he peered into my

face. "You’ll not resemble your mother.”

“He’ll resemble no one,” said my father, shortly.

“Good-by, Davy. Keep this till I come again.” And he gave me the

parcel made of my mother’s gown. Then he lifted me in his strong

arms and kissed me, and strode out of the house. We listened in

silence as he went down the steps, and until his footsteps died

away on the path. Then the gentleman rose and pulled a cord

hastily. The negro came in.

“Put the lad to bed, Breed,” said he.

“Whah, suh?”

“Oh, anywhere,” said the master. He turned to me.

“I’ll be better able to talk to you in the morning, David,” said

he.

I followed the old servant up the great stairs, gulping down a

sob that would rise, and clutching my mother’s gown tight under my

arm. Had my father left me alone in our cabin for a fortnight, I

should not have minded. But here, in this strange house, amid such

strange surroundings, I was heartbroken. The old negro was very

kind. He led me into a little bedroom, and placing the candle on a

polished dresser, he regarded me with sympathy.

“So you’re Miss Lizbeth’s boy,” said he. "An’ she dade. An’

Marse Alec rough an’ hard es though he been bo’n in de woods.

Honey, ol’ Breed’ll tek care ob you. I’ll git you one o’ dem night

rails Marse Nick has, and some ob his’n close in de mawnin’.”

These things I remember, and likewise sobbing myself to sleep in

the four-poster. Often since I have wished that I had questioned

Breed of many things on which I had no curiosity then, for he was

my chief companion in the weeks that followed. He awoke me bright

and early the next day.

“Heah’s some close o’ Marse Nick’s you kin wear, honey,” he

said.

“Who is Master Nick?” I asked.

Breed slapped his thigh.

“Marse Nick Temple, Marsa’s son. He’s ’bout you size, but he

ain’ no mo’ laik you den a Jack rabbit’s laik an’ owl. Dey ain’

none laik Marse Nick fo’ gittin’ into trouble-and gittin’ out

agin.”

“Where is he now?” I asked.

“He at Temple Bow, on de Ashley Ribber. Dat’s de Marsa’s

barony.”

“His what?”

“De place whah he lib at, in de country.”

“And why isn’t the master there?”

I remember that Breed gave a wink, and led me out of the window

onto a gallery above the one where we had found the master the

night before. He pointed across the dense foliage of the garden to

a strip of water gleaming in the morning sun beyond.

“See dat boat?” said the negro. "Sometime de Marse he tek ar

ride in dat boat at night. Sometime gentlemen comes heah in a

pow’ful hurry to git away, out’n de harbor whah de English is at.”

By that time I was dressed, and marvellously uncomfortable in

Master Nick’s clothes. But as I was going out of the door, Breed

hailed me.

“Marse Dave,” — it was the first time I had been called

that, — "Marse Dave, you ain’t gwineter tell?”

“Tell what?” I asked.

“Bout’n de boat, and Marsa agwine away nights.”

“No,” said I, indignantly.

“I knowed you wahn’t,” said Breed. "You don’ look as if you’d

tell anything.”

We found the master pacing the lower gallery. At first he barely

glanced at me, and nodded. After a while he stopped, and began to

put to me many questions about my life: when and how I had lived.

And to some of my answers he exclaimed, “Good God!” That was all.

He was a handsome man, with hands like a woman’s, well set off by

the lace at his sleeves. He had fine-cut features, and the white

linen he wore was most becoming.

“David,” said he, at length, and I noted that he lowered his

voice, “David, you seem a discreet lad. Pay attention to what I

tell you. And mark! if you disobey me, you will be well whipped.

You have this house and garden to play in, but you are by no means

to go out at the front of the house. And whatever you may see or

hear, you are to tell no one. Do you understand?”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

“For the rest,” said he, “Breed will give you food, and look out

for your welfare.”

And so he dismissed me. They were lonely days after that for a

boy used to activity, and only the damp garden paths and lawns to

run on. The creek at the back of the garden was stagnant and

marshy when the water fell, and overhung by leafy boughs. On each

side of the garden was a high brick wall. And though I was often

tempted to climb it, I felt that disobedience was disloyalty to my

father. Then there was the great house, dark and lonely in its

magnificence, over which I roamed until I knew every corner of it.

I was most interested of all in the pictures of men and women in

quaint, old-time costumes, and I used during the great heat of the

day to sit in the drawing-room and study these, and wonder who

they were and when they lived. Another amusement I had was to

climb into the deep windows and peer through the blinds across the

front garden into the street. Sometimes men stopped and talked

loudly there, and again a rattle of drums would send me running to

see the soldiers. I recall that I had a poor enough notion of what

the fighting was all about. And no wonder. But I remember chiefly

my insatiable longing to escape from this prison, as the great

house soon became for me. And I yearned with a yearning I cannot

express for our cabin in the hills and the old life there.

I caught glimpses of the master on occasions only, and then I

avoided him; for I knew he had no wish to see me. Sometimes he

would be seated in the gallery, tapping his foot on the floor, and

sometimes pacing the garden walks with his hands opening and

shutting. And one night I awoke with a start, and lay for a while

listening until I heard something like a splash, and the scraping

of the bottom-boards of a boat. Irresistibly I jumped out of bed,

and running to the gallery rail I saw two dark figures moving

among the leaves below. The next morning I came suddenly on a

strange gentleman in the gallery. He wore a flowered dressing-gown

like the one I had seen on the master, and he had a jolly, round

face. I stopped and stared.

“Who the devil are you?” said he, but not unkindly.

“My name is David Trimble,” said I, “and I come from the

mountains.”

He laughed.

“Mr. David Trimble-from-the-mountains, who the devil am I?”

“I don’t know, sir,” and I started to go away, not wishing to

disturb him.

“Avast!” he cried. "Stand fast. See that you remember that.”

“I’m not here of my free will, sir, but because my father wishes

it. And I’ll betray nothing.”

Then he stared at me.

“How old did you say you were?” he demanded.

“I didn’t say,” said I.

“And you are of Scotch descent?” said he.

“I didn’t say so, sir.”

“You’re a rum one,” said he, laughing again, and he disappeared

into the house.

That day, when Breed brought me my dinner on my gallery, he did

not speak of a visitor. You may be sure I did not mention the

circumstance. But Breed always told me the outside news.

“Dey’s gittin’ ready fo’ a big fight, Marse Dave,” said he.

"Mister Moultrie in the fo’t in de bay, an’ Marse Gen’l Lee tryin’

for to boss him. Dey’s Rebels. An’ Marse Admiral Parker an’ de

King’s reg’ments fixin’ fo’ to tek de fo’t, an’ den Charlesto’n.

Dey say Mister Moultrie ain’t got no mo’ chance dan a treed

’possum.”

“Why, Breed?” I asked. I had heard my father talk of England’s

power and might, and Mister Moultrie seemed to me a very brave man

in his little fort.

“Why!” exclaimed the old negro. "You ain’t neber read no hist’ry

books. I knows some of de gentlemen wid Mister Moultrie. Dey ain’t

no soldiers. Some is fine gentlemen, to be suah, but it’s jist

foolishness to fight dat fleet an’ army. Marse Gen’l Lee hisself,

he done sesso. I heerd him.”

“And he’s on Mister Moultrie’s side?” I asked.

“Sholy,” said Breed. "He’s de Rebel gen’l.”

“Then he’s a knave and a coward!” I cried with a boy’s

indignation. "Where did you hear him say that?” I demanded,

incredulous of some of Breed’s talk.

“Right heah in dis house,” he answered, and quickly clapped his

hand to his mouth, and showed the whites of his eyes. "You ain’t

agwineter tell dat, Marse Dave?”

“Of course not,” said I. And then: "I wish I could see Mister

Moultrie in his fort, and the fleet.”

“Why, honey, so you kin,” said Breed.

The good-natured negro dropped his work and led the way

upstairs, I following expectant, to the attic. A rickety ladder

rose to a kind of tower (cupola, I suppose it would be called),

whence the bay spread out before me like a picture, the white

islands edged with the whiter lacing of the waves. There, indeed,

was the fleet, but far away, like toy ships on the water, and the

bit of a fort perched on the sandy edge of an island. I spent most

of that day there, watching anxiously for some movement. But none

came.

That night I was again awakened. And running into the gallery, I

heard quick footsteps in the garden. Then there was a lantern’s

flash, a smothered oath, and all was dark again. But in the flash

I had seen distinctly three figures. One was Breed, and he held

the lantern; another was the master; and the third, a stout one

muffled in a cloak, I made no doubt was my jolly friend. I lay

long awake, with a boy’s curiosity, until presently the dawn

broke, and I arose and dressed, and began to wander about the

house. No Breed was sweeping the gallery, nor was there any sign

of the master. The house was as still as a tomb, and the echoes of

my footsteps rolled through the halls and chambers. At last,

prompted by curiosity and fear, I sought the kitchen, where I had

often sat with Breed as he cooked the master’s dinner. This was at

the bottom and end of the house. The great fire there was cold,

and the pots and pans hung neatly on their hooks, untouched that

day. I was running through the wet garden, glad to be out in the

light, when a sound stopped me.

It was a dull roar from the direction of the bay. Almost

instantly came another, and another, and then several broke

together. And I knew that the battle had begun. Forgetting for the

moment my loneliness, I ran into the house and up the stairs two

at a time, and up the ladder into the cupola, where I flung open

the casement and leaned out.

There was the battle indeed, — a sight so vivid to me after all

these years that I can call it again before me when I will. The

toy men-o’-war, with sails set, ranging in front of the fort. They

looked at my distance to be pressed against it. White puffs, like

cotton balls, would dart one after another from a ship’s side,

melt into a cloud, float over her spars, and hide her from my

view. And then presently the roar would reach me, and answering

puffs along the line of the fort. And I could see the mortar

shells go up and up, leaving a scorched trail behind, curve in a

great circle, and fall upon the little garrison. Mister Moultrie

became a real person to me then, a vivid picture in my boyish

mind — a hero beyond all other heroes.

As the sun got up in the heavens and the wind fell, the cupola

became a bake-oven. But I scarcely felt the heat. My whole soul

was out in the bay, pent up with the men in the fort. How long

could they hold out? Why were they not all killed by the shot that

fell like hail among them? Yet puff after puff sprang from their

guns, and the sound of it was like a storm coming nearer in the

heat. But at noon it seemed to me as though some of the ships were

sailing. It was true. Slowly they drew away from the others, and

presently I thought they had stopped again. Surely two of them

were stuck together, then three were fast on a shoal. Boats, like

black bugs in the water, came and went between them and the

others. After a long time the two that were together got apart and

away. But the third stayed there, immovable, helpless.

Throughout the afternoon the fight, kept on, the little black

boats coming and going. I saw a mast totter and fall on one of the

ships. I saw the flag shot away from the fort, and reappear again.

But now the puffs came from her walls slowly and more slowly, so

that my heart sank with the setting sun. And presently it grew too

dark to see aught save the red flashes. Slowly, reluctantly, the

noise died down until at last a great silence reigned, broken only

now and again by voices in the streets below me. It was not until

then that I realized that I had been all day without food — that I

was alone in the dark of a great house.

I had never known fear in the woods at night. But now I trembled

as I felt my way down the ladder, and groped and stumbled through

the black attic for the stairs. Every noise I made seemed louder

an hundred fold than the battle had been, and when I barked my

shins, the pain was sharper than a knife. Below, on the big

stairway, the echo of my footsteps sounded again from the empty

rooms, so that I was taken with a panic and fled downward, sliding

and falling, until I reached the hall. Frantically as I tried, I

could not unfasten the bolts on the front door. And so, running

into the drawing-room, I pried open the window, and sat me down in

the embrasure to think, and to try to quiet the thumpings of my

heart.

By degrees I succeeded. The still air of the night and the

heavy, damp odors of the foliage helped me. And I tried to think

what was right for me to do. I had promised the master not to

leave the place, and that promise seemed in pledge to my father.

Surely the master would come back — or Breed. They would not leave

me here alone without food much longer. Although I was young, I

was brought up to responsibility. And I inherited a conscience

that has since given me much trouble.

From these thoughts, trying enough for a starved lad, I fell to

thinking of my father on the frontier fighting the Cherokees. And

so I dozed away to dream of him. I remember that he was skinning

Cameron, — I had often pictured it, — and Cameron yelling, when I was

awakened with a shock by a great noise.

I listened with my heart in my throat. The noise seemed to come

from the hall, — a prodigious pounding. Presently it stopped, and a

man’s voice cried out: —

“Ho there, within!”

My first impulse was to answer. But fear kept me still.

“Batter down the door,” some one shouted.

There was a sound of shuffling in the portico, and the same

voice: —

“Now then, all together, lads!”

Then came a straining and splitting of wood, and with a crash

the door gave way. A lantern’s rays shot through the hall.

“The house is as dark as a tomb,” said a voice.

“And as empty, I reckon,” said another. "John Temple and his spy

have got away.”

“We’ll have a search,” answered the first voice.

They stood for a moment in the drawing-room door, peering, and

then they entered. There were five of them. Two looked to be

gentlemen, and three were of rougher appearance. They carried

lanterns.

“That window’s open,” said one of the gentlemen. "They must have

been here to-day. Hello, what’s this?” He started back in

surprise.

I slid down from the window-seat, and stood facing them, not

knowing what else to do. They, too, seemed equally confounded.

“It must be Temple’s son,” said one, at last. "I had thought the

family at Temple Bow. What’s your name, my lad?”

“David Trimble, sir,” said I.

“And what are you doing here?” he asked more sternly.

“I was left in Mr. Temple’s care by my father.”

“Oho!” he cried. "And where is your father?”

“He’s gone to fight the Cherokees,” I answered soberly. "To skin

a man named Cameron.”

At that they were silent for an instant, and then the two broke

into a laugh.

“Egad, Lowndes,” said the gentleman, “here is a fine mystery. Do

you think the boy is lying?”

The other gentleman scratched his forehead.

“I’ll have you know I don’t lie, sir,” I said, ready to cry.

“No,” said the other gentleman. "A backwoodsman named Trimble

went to Rutledge with credentials from North Carolina, and has

gone off to Cherokee Ford to join McCall.”

“Bless my soul!” exclaimed the first gentleman. He came up and

laid his hand on my shoulder, and said: —

“Where is Mr. Temple?”

“That I don’t know, sir.”

“When did he go away?”

I did not answer at once.

“That I can’t tell you, sir.”

“Was there any one with him?”

“That I can’t tell you, sir.”

“The devil you can’t!” he cried, taking his hand away. "And why

not?”

I shook my head, sorely beset.

“Come, Mathews,” cried the gentleman called Lowndes.

“We’ll search first, and attend to the lad after.”

And so they began going through the house, prying into every

cupboard and sweeping under every bed. They even climbed to the

attic; and noting the open casement in the cupola, Mr. Lowndes

said: —

“Some one has been here to-day.”

“It was I, sir,” I said. "I have been here all day.”

“And what doing, pray?” he demanded.

“Watching the battle. And oh, sir,” I cried, “can you tell me

whether Mister Moultrie beat the British?”

“He did so,” cried Mr. Lowndes. "He did, and soundly.”

He stared at me. I must have looked my pleasure.

“Why, David,” says he, “you are a patriot, too.”

“I am a Rebel, sir,” I cried hotly.

Both gentlemen laughed again, and the men with them.

“The lad is a character,” said Mr. Lowndes.

We made our way down into the garden, which they searched last.

At the creek’s side the boat was gone, and there were footsteps in

the mud.

“The bird has flown, Lowndes,” said Mr. Mathews.

“And good riddance for the Committee,” answered that gentleman,

heartily. "He got to the fleet in fine season to get a round shot

in the middle. David,” said he, solemnly, “remember it never pays

to try to be two things at once.”

“I’ll warrant he stayed below water,” said Mr. Mathews.

“But what shall we do with the lad?”

“I’ll take him to my house for the night,” said Mr. Lowndes,

"and in the morning we’ll talk to him. I reckon he should be sent

to Temple Bow. He is connected in some way with the Temples.”

“God help him if he goes there,” said Mr. Mathews, under his

breath. But I heard him.

They locked up the house, and left one of the men to guard it,

while I went with Mr. Lowndes to his residence. I remember that

people were gathered in the streets as we passed, making merry,

and that they greeted Mr. Lowndes with respect and good cheer. His

house, too, was set in a garden and quite as fine as Mr. Temple’s.

It was ablaze with candles, and I caught glimpses of fine

gentlemen and ladies in the rooms. But he hurried me through the

hall, and into a little chamber at the rear where a writing-desk

was set. He turned and faced me.

“You must be tired, David,” he said.

I nodded.

“And hungry? Boys are always hungry.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You had no dinner?”

“No, sir,” I answered, off my guard.

“Mercy!” he said. "It is a long time since breakfast.”

“I had no breakfast, sir.”

“Good God!” he said, and pulled the velvet handle of a cord. A

negro came.

“Is the supper for the guests ready?”

“Yes, Marsa.”

“Then bring as much as you can carry here,” said the gentleman.

"And ask Mrs. Lowndes if I may speak with her.”

Mrs. Lowndes came first. And such a fine lady she was that she

frightened me, this being my first experience with ladies. But

when Mr. Lowndes told her my story, she ran to me impulsively and

put her arms about me.

“Poor lad!” she said. "What a shame!”

I think that the tears came then, but it was small wonder. There

were tears in her eyes, too.

Such a supper as I had I shall never forget. And she sat beside

me for long, neglecting her guests, and talking of my life.

Suddenly she turned to her husband, calling him by name.

“He is Alec Ritchie’s son,” she said, “and Alec has gone against

Cameron.”

Mr. Lowndes did not answer, but nodded.

“And must he go to Temple Bow?”

“My dear,” said Mr. Lowndes, “I fear it is our duty to send him

there.”

In the morning I started for Temple Bow on horseback behind one

of Mr. Lowndes’ negroes. Good Mrs. Lowndes had kissed me at

parting, and tucked into my pocket a parcel of sweetmeats. There

had been a few grave gentlemen to see me, and to their questions I

had replied what I could. But tell them of Mr. Temple I would not,

save that he himself had told me nothing. And Mr. Lowndes had

presently put an end to their talk.

“The lad knows nothing, gentlemen,” he had said, which was true.

“David,” said he, when he bade me farewell, “I see that your

father has brought you up to fear God. Remember that all you see

in this life is not to be imitated.”

And so I went off behind his negro. He was a merry lad, and

despite the great heat of the journey and my misgivings about

Temple Bow, he made me laugh. I was sad at crossing the ferry over

the Ashley, through thinking of my father, but I reflected that it

could not be long now ere I saw him again. In the middle of the

day we stopped at a tavern. And at length, in the abundant shade

of evening, we came to a pair of great ornamental gates set

between brick pillars capped with white balls, and turned into a

drive. And presently, winding through the trees, we were in sight

of a long, brick mansion trimmed with white, and a velvet lawn

before it all flecked with shadows. In front of the portico was a

saddled horse, craning his long neck at two panting hounds

stretched on the ground. A negro boy in blue clutched the bridle.

On the horse-block a gentleman in white reclined. He wore shiny

boots, and he held his hat in his hand, and he was gazing up at a

lady who stood on the steps above him.

The lady I remember as well — Lord forbid that I should forget

her. And her laugh as I heard it that evening is ringing now in my

ears. And yet it was not a laugh. Musical it was, yet there seemed

no pleasure in it: rather irony, and a great weariness of the

amusements of this world: and a note, too, from a vanity never

ruffled. It stopped abruptly as the negro pulled up his horse

before her, and she stared at us haughtily.

“What’s this?” she said.

“Pardon, Mistis,” said the negro, “I’se got a letter from Marse

Lowndes.”

“Mr. Lowndes should instruct his niggers,” she said. "There is a

servants’ drive.” The man was turning his horse when she cried:

"Hold! Let’s have it.”

He dismounted and gave her the letter, and I jumped to the

ground, watching her as she broke the seal, taking her in, as a

boy will, from the flowing skirt and tight-laced stays of her

salmon silk to her high and powdered hair. She must have been

about thirty. Her face was beautiful, but had no particle of

expression in it, and was dotted here and there with little black

patches of plaster. While she was reading, a sober gentleman in

black silk-breeches and severe coat came out of the house and

stood beside her.

“Heigho, parson,” said the gentleman on the horse-block, without

moving, “are you to preach against loo or lansquenet to-morrow?”

“Would it make any difference to you, Mr. Riddle?”

Before he could answer there came a great clatter behind them,

and a boy of my own age appeared. With a leap he landed sprawling

on the indolent gentleman’s shoulders, nearly upsetting him.

“You young rascal!” exclaimed the gentleman, pitching him on the

drive almost at my feet; then he fell back again to a position

where he could look up at the lady.

“Harry Riddle,” cried the boy, “I’ll ride steeplechases and beat

you some day.”

“Hush, Nick,” cried the lady, petulantly, “I’ll have no nerves

left me.” She turned to the letter again, holding it very near to

her eyes, and made a wry face of impatience. Then she held the

sheet out to Mr. Riddle.

“A pretty piece of news,” she said languidly. "Read it, Harry.”

The gentleman seized her hand instead. The lady glanced at the

clergyman, whose back was turned, and shook her head.

“How tiresome you are!” she said.

“What’s happened?” asked Mr. Riddle, letting go as the parson

looked around.

“Oh, they’ve had a battle,” said the lady, “and Moultrie and his

Rebels have beat off the King’s fleet.”

“The devil they have!” exclaimed Mr. Riddle, while the parson

started forwards. "Anything more?”

“Yes, a little.” She hesitated. "That husband of mine has fled

Charlestown. They think he went to the fleet.” And she shot a

meaning look at Mr. Riddle, who in turn flushed red. I was

watching them.

“What!” cried the clergyman, “John Temple has run away?”

“Why not,” said Mr. Riddle. "One can’t live between wind and

water long. And Charlestown’s — uncomfortable in summer.”

At that the clergyman cast one look at them — such a look as I

shall never forget — and went into the house.

“Mamma,” said the boy, “where has father gone? Has he run away?”

“Yes. Don’t bother me, Nick.”

“I don’t believe it,” cried Nick, his high voice shaking.

"I’d — I’d disown him.”

At that Mr. Riddle burst into a hearty laugh.

“Come, Nick,” said he, “it isn’t so bad as that. Your father’s

for his Majesty, like the rest of us. He’s merely gone over to

fight for him.” And he looked at the lady and laughed again. But I

liked the boy.

As for the lady, she curled her lip. "Mr. Riddle, don’t be

foolish,” she said. "If we are to play, send your horse to the

stables.” Suddenly her eye lighted on me. "One more brat,” she

sighed. "Nick, take him to the nursery, or the stable. And both of

you keep out of my sight.”

Nick strode up to me.

“Don’t mind her. She’s always saying, ‘Keep out of my

sight.’”

His voice trembled. He took me by the sleeve and began pulling me

around the house and into a little summer bower that stood there;

for he had a masterful manner.

“What’s your name?” he demanded.

“David Trimble,” I said.

“Have you seen my father in town?”

The intense earnestness of the question surprised an answer out

of me.

“Yes.”

“Where?” he demanded.

“In his house. My father left me with your father.”

“Tell me about it.”

I related as much as I dared, leaving out Mr. Temple’s double

dealing; which, in truth, I did not understand. But the boy was

relentless.

“Why,” said he, “my father was a friend of Mr. Lowndes and Mr.

Mathews. I have seen them here drinking with him. And in town. And

he ran away?”

“I do not know where he went,” said I, which was the truth.

He said nothing, but hid his face in his arms over the rail of

the bower. At length he looked up at me fiercely.

“If you ever tell this, I will kill you,” he cried. "Do you

hear?”

That made me angry.

“Yes, I hear,” I said. "But I am not afraid of you.”

He was at me in an instant, knocking me to the floor, so that

the breath went out of me, and was pounding me vigorously ere I

recovered from the shock and astonishment of it and began to

defend myself. He was taller than I, and wiry, but not so rugged.

Yet there was a look about him that was far beyond his strength. A

look that meant, never say die. Curiously, even as I fought

desperately I compared him with that other lad I had known, Andy

Jackson. And this one, though not so powerful, frightened me the

more in his relentlessness.

Perhaps we should have been fighting still had not some one

pulled us apart, and when my vision cleared I saw Nick, struggling

and kicking, held tightly in the hands of the clergyman. And it

was all that gentleman could do to hold him. I am sure it was

quite five minutes before he forced the lad, exhausted, on to the

seat. And then there was a defiance about his nostrils that showed

he was undefeated. The clergyman, still holding him with one hand,

took out his handkerchief with the other and wiped his brow.

I expected a scolding and a sermon. To my amazement the

clergyman said quietly: —

“Now what was the trouble, David?”

“I’ll not be the one to tell it, sir,” I said, and trembled at

my temerity.

The parson looked at me queerly.

“Then you are in the right of it,” he said. "It is as I thought;

I’ll not expect Nicholas to tell me.”

“I will tell you, sir,” said Nicholas. "He was in the house with

my father when — when he ran away. And I said that if he ever spoke

of it to any one, I would kill him.”

For a while the clergyman was silent, gazing with a strange

tenderness at the lad, whose face was averted.

“And you, David?” he said presently.

“I — I never mean to tell, sir. But I was not to be frightened.”

“Quite right, my lad,” said the clergyman, so kindly that it

sent a strange thrill through me. Nicholas looked up quickly.

“You won’t tell?” he said.

“No,” I said.

“You can let me go now, Mr. Mason,” said he. Mr. Mason did. And

he came over and sat beside me, but said nothing more.

After a while Mr. Mason cleared his throat.

“Nicholas,” said he, “when you grow older you will understand

these matters better. Your father went away to join the side he

believes in, the side we all believe in — the King’s side.”

“Did he ever pretend to like the other side?” asked Nick,

quickly.

“When you grow older you will know his motives,” answered the

clergyman, gently. "Until then; you must trust him.”

“You never pretended,” cried Nick.

“Thank God I never was forced to do so,” said the clergyman,

fervently.

It is wonderful that the conditions of our existence may wholly

change without a seeming strangeness. After many years only vivid

snatches of what I saw and heard and did at Temple Bow come back

to me. I understood but little the meaning of the seigniorial life

there. My chief wonder now is that its golden surface was not more

troubled by the winds then brewing. It was a new life to me, one

that I had not dreamed of.

After that first falling out, Nick and I became inseparable. Far

slower than he in my likes and dislikes, he soon became a passion

with me. Even as a boy, he did everything with a grace

unsurpassed; the dash and daring of his pranks took one’s breath;

his generosity to those he loved was prodigal. Nor did he ever

miss a chance to score those under his displeasure. At times he

was reckless beyond words to describe, and again he would fall

sober for a day. He could be cruel and tender in the same hour;

abandoned and freezing in his dignity. He had an old negro mammy

whose worship for him and his possessions was idolatry. I can hear

her now calling and calling, “Marse Nick, honey, yo’ supper’s done

got cole,” as she searched patiently among the magnolias. And

suddenly there would be a shout, and Mammy’s turban go flying from

her woolly head, or Mammy herself would be dragged down from

behind and sat upon.

We had our supper, Nick and I, at twilight, in the children’s

dining room. A little white room, unevenly panelled, the silver

candlesticks and yellow flames fantastically reflected in the

mirrors between the deep windows, and the moths and June-bugs

tilting at the lights. We sat at a little mahogany table eating

porridge and cream from round blue bowls, with Mammy to wait on

us. Sometimes there floated in upon us the hum of revelry from the

great drawing-room where Madame had her company. Often the good

Mr. Mason would come in to us (he cared little for the parties),

and talk to us of our day’s doings. Nick had his lessons from the

clergyman in the winter time.

Mr. Mason took occasion once to question me on what I knew. Some

of my answers, in especial those relating to my knowledge of the

Bible, surprised him. Others made him sad.

“David,” said he, “you are an earnest lad, with a head to learn,

and you will. When your father comes, I shall talk with him.” He

paused — "I knew him,” said he, “I knew him ere you were born. A

just man, and upright, but with a great sorrow. We must never be

hasty in our judgments. But you will never be hasty, David,” he

added, smiling at me. "You are a good companion for Nicholas.”

Nicholas and I slept in the same bedroom, at a corner of the

long house, and far removed from his mother. She would not be

disturbed by the noise he made in the mornings. I remember that he

had cut in the solid shutters of that room, folded into the

embrasures,

“Nicholas Temple, His Mark,”

and a long, flat sword.

The first night in that room we slept but little, near the whole

of it being occupied with tales of my adventures and of my life in

the mountains. Over and over again I must tell him of the

"painters" and wildcats, of deer and bear and wolf. Nor was he

ever satisfied. And at length I came to speak of that land where I

had often lived in fancy — the land beyond the mountains of which

Daniel Boone had told. Of its forest and glade, its countless

herds of elk and buffalo, its salt-licks and Indians, until we

fell asleep from sheer exhaustion.

“I will go there,” he cried in the morning, as he hurried into

his clothes; "I will go to that land as sure as my name is Nick

Temple. And you shall go with me, David.”

“Perchance I shall go before you,” I answered, though I had

small hopes of persuading my father.

He would often make his exit by the window, climbing down into

the garden by the protruding bricks at the corner of the house; or

sometimes go shouting down the long halls and through the gallery

to the great stairway, a smothered oath from behind the closed

bedroom doors proclaiming that he had waked a guest. And many days

we spent in the wood, playing at hunting game — a poor enough

amusement for me, and one that Nick soon tired of. They were

thick, wet woods, unlike our woods of the mountains; and more than

once we had excitement enough with the snakes that lay there.

I believe that in a week’s time Nick was as conversant with my

life as I myself. For he made me tell of it again and again, and

of Kentucky. And always as he listened his eyes would glow and his

breast heave with excitement.

“Do you think your father will take you there, David, when he

comes for you?”

I hoped so, but was doubtful.

“I’ll run away with you,” he declared. "There is no one here who

cares for me save Mr. Mason and Mammy.”

And I believe he meant it. He saw but little of his mother, and

nearly always something unpleasant was coupled with his views.

Sometimes we ran across her in the garden paths walking with a

gallant, — oftenest Mr. Riddle. It was a beautiful garden, with

hedge-bordered walks and flowers wondrously massed in color, a

high brick wall surrounding it. Frequently Mrs. Temple and Mr.

Riddle would play at cards there of an afternoon, and when that

musical, unbelieving laugh of hers came floating over the wall,

Nick would say: —

“Mamma is winning.”

Once we heard high words between the two, and running into the

garden found the cards scattered on the grass, and the couple

gone.

Of all Nick’s escapades, — and he was continually in and out of

them, — I recall only a few of the more serious. As I have said, he

was a wild lad, sobered by none of the things which had gone to

make my life, and what he took into his head to do he generally

did, — or, if balked, flew into such a rage as to make one believe

he could not live. Life was always war with him, or some semblance

of a struggle. Of his many wild doings I recall well the time

when — fired by my tales of hunting — he went out to attack the young

bull in the paddock with a bow and arrow. It made small difference

to the bull that the arrow was too blunt to enter his hide. With a

bellow that frightened the idle negroes at the slave quarters, he

started for Master Nick. I, who had been taught by my father never

to run any unnecessary risk, had taken the precaution to provide

as large a stone as I could comfortably throw, and took station on

the fence. As the furious animal came charging, with his head

lowered, I struck him by a good fortune between the eyes, and

Nicholas got over. We were standing on the far side, watching him

pawing the broken bow, when, in the crowd of frightened negroes,

we discovered the parson beside us.

“David,” said he, patting me with a shaking hand, “I perceive

that you have a cool head. Our young friend here has a hot one.

Dr. Johnson may not care for Scotch blood, and yet I think a wee

bit of it is not to be despised.”

I wondered whether Dr. Johnson was staying in the house, too.

How many slaves there were at Temple Bow I know not, but we used

to see them coming home at night in droves, the overseers riding

beside them with whips and guns. One day a huge Congo chief, not

long from Africa, nearly killed an overseer, and escaped to the

swamp. As the day fell, we heard the baying of the bloodhounds hot

upon his trail. More ominous still, a sound like a rising wind

came from the direction of the quarters. Into our little

dining-room burst Mrs. Temple herself, slamming the door behind

her. Mr. Mason, who was sitting with us, rose to calm her.

“The Rebels!” she cried. "The Rebels have taught them this, with

their accursed notions of liberty and equality. We shall all be

murdered by the blacks because of the Rebels. Oh, hell-fire is too

good for them. Have the house barred and a watch set to-night.

What shall we do?”

“I pray you compose yourself, Madame,” said the clergyman. "We

can send for the militia.”

“The militia!” she shrieked; "the Rebel militia! They would

murder us as soon as the niggers.”

“They are respectable men,” answered Mr. Mason, “and were at

Fanning Hall to-day patrolling.”

“I would rather be killed by whites than blacks,” said the lady.

"But who is to go for the militia?”

“I will ride for them,” said Mr. Mason. It was a dark, lowering

night, and spitting rain.

“And leave me defenceless!” she cried. "You do not stir, sir.”

“It is a pity,” said Mr. Mason — he was goaded to it, I

suppose — "’tis a pity Mr. Riddle did not come to-night.”

She shot at him a withering look, for even in her fear she would

brook no liberties. Nick spoke up: —

“I will go,” said he; "I can get through the woods to Fanning

Hall — "

“And I will go with him,” I said.

“Let the brats go,” she said, and cut short Mr. Mason’s

expostulations. She drew Nick to her and kissed him. He wriggled

away, and without more ado we climbed out of the dining-room

windows into the night. Running across the lawn, we left the

lights of the great house twinkling behind us in the rain. We had

to pass the long line of cabins at the quarters. Three overseers

with lanterns stood guard there; the cabins were dark, the

wretches within silent and cowed. Thence we felt with our feet for

the path across the fields, stumbled over a sty, and took our way

through the black woods. I was at home here, and Nick was not to

be frightened. At intervals the mournful bay of a bloodhound came

to us from a distance.

“Suppose we should meet the Congo chief,” said Nick, suddenly.

The idea had occurred to me.

“She needn’t have been so frightened,” said he, in scornful

remembrance of his mother’s actions.

We pressed on. Nick knew the path as only a boy can. Half an

hour passed. It grew brighter. The rain ceased, and a new moon

shot out between the leaves. I seized his arm.

“What’s that?” I whispered.

“A deer.”

But I, cradled in woodcraft, had heard plainly a man creeping

through the underbrush beside us. Fear of the Congo chief and pity

for the wretch tore at my heart. Suddenly there loomed in front of

us, on the path, a great, naked man. We stood with useless limbs,

staring at him.

Then, from the trees over our heads, came a chittering and a

chattering such as I had never heard. The big man before us

dropped to the earth, his head bowed, muttering. As for me, my

fright increased. The chattering stopped, and Nick stepped forward

and laid his hand on the negro’s bare shoulder.

“We needn’t be afraid of him now, Davy,” he said. "I learned

that trick from a Portuguese overseer we had last year.”

“You did it!” I exclaimed, my astonishment overcoming my fear.

“It’s the way the monkeys chatter in the Canaries,” he said.