Catharine Cole.

Martha Field.

"The Story of Old French Market."

HOUGH

America boasts but few antiquities, there are to be found, here and there, spots hallowed by age and romance. Localities where one feels the littleness of

the span of human life. Where are memories that go back far

beyond our ken. Where the waves of birth, and life, and death

have time and again risen and passed, leaving untouched some

age-old, hoary monument to a time that once was but will never

be again.

HOUGH

America boasts but few antiquities, there are to be found, here and there, spots hallowed by age and romance. Localities where one feels the littleness of

the span of human life. Where are memories that go back far

beyond our ken. Where the waves of birth, and life, and death

have time and again risen and passed, leaving untouched some

age-old, hoary monument to a time that once was but will never

be again.

Such is the French Market of New Orleans.

Not old when measured by the span of the world of Phoenicia, Egypt or Rome. But gray and wrinkled with its weight of years in contrast with the pulsing modern life about it.

Here, to those who can appreciate it, is something better than paths electric-lighted. A quaint, picturesque survival of a strange traffic feature of early days, when the lilies of France were native to the city that bears the name of the old Regent.

I love the paths that lead to the old French Market. And I love the entrancing perfumes that carry me back to those quaint old days when it was in the heyday of its glory.

The dominant note is the spicy, fragrant accent that comes from the dark, delicious coffee that, more than any other one thing, is bound up with the traditions of the historic old building. I sit in a dim corner, where the tide of life passes me by, and muse and dream of days that are gone when all was unlike its present form save for the old Market and the selfsame aroma of the only coffee in all the world that has lived and thrived while the centuries passed, swiftly and silently, down the pathway of time.

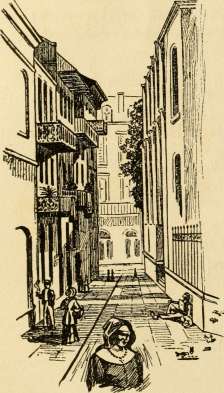

To find the old French Market one must go to the very cornerstone of the old town's history; to the gay, green remnant of the Place d'Armes, and even farther, where the river wraps the town in its tawny scarf as the mane of a lion caresses his neck.

Down in the neighborhood of that old, gray-garbed Cathedral St. Louis, whose bulging, sharp-angled shoulders and belfried Breton towers lean far across the noon-sweet sky, is the way to the place we seek.

As I look out at it from the dusk-collared corridor, with its lazy pretense of bustle of the Rue Chartres, I have corner-wise glimpses of stone alleys and damp flagged passages; and balconied streets line old Florentine loggias that lead the way past historic buildings toward the tumbled perspective of that King, Queen and Royal Family of markets — the French Market of New Orleans.

Come with me along a footpath trodden by Atolycus no less than Saint, where the cool Cathedral closes are, past the tiny religious shops that sprout about the church.

In a sort of monastic repose they pray under the shadow of the dull, granite cloud of the great Cathedral. In their window shrines pale virgins flower divinely sweet on their tall pedestals.

Opposite a little oasis of green let into this Sahara of stone, banana trees wave their broad green flags; and the airily-petaled olive distills its sweeter than incense on the air.

Across the passage St. Antoine, named a century ago in loving memory of that old, sweet Capuchin whose bones are dust under the altars Don Almonaster built, a great tropic wistaria swings its purple flowers like a new sort of Jacob's ladder.

It reaches from the Cathedral garden across the air, and up to the green jalousies behind which live the Cathedral priests. When services are dumb in the church they live there with their birds and books and missals; environed in priceless pieces of old-world furniture, and — like modern Robinson Crusoes — amused by the tongue-deep gossip of poll parrots. ¶In their doorways sit old sentinels of concierges, sharp-eyed and jealous, giving entrance only to those who come for shriving and prayer.

The gay, town birds hop all the day long up and down that airy ladder of vines that binds the old church to the vestry house. One might think them feathered nuns telling their beads on this floral rosary.

At the one side is the Cathedral like a hooded friar in frock of gray. On the other is the rich Spanish architecture of the old Cabildo, built in 1794 by Don Andres Almonaster y Roxas, founder and builder of the Cathedral.

Most famous of all the famous landmarks of the "Crescent City" is the old Cabildo. "Cabildo" is Spanish for Governing Council, and here the laws were made in those dim old days, before the Stars and Stripes — aye! even before the tri-color of France — floated over the city.

It was here that Spain handed over her sovereignty over Louisiana to France. And here a few weeks later France, in turn, relinquished the "Louisiana Purchase" to the United States.

La Fayette lived here in 1825. The much - loved McKinley considered himself honored to be invited to speak from its quaint balconies.

Later the Supreme Court of Louisiana found here an abode rich in historic suggestions of those earlier law makers. This is a law court to this day.

Following the continental custom, when court is in session, heavy chain barriers are festooned across each of the streets before the court; and all bare, silent and stately it becomes for the time "No Thoroughfare." So silent is it that the old maman on her skinny knees in the dim, dark church can hear above her own orisons, like the droning of a sawmill wheel, some "avocat" pleading before a human judge.

Across the way I can see the broad, green smile of the public square.

It is the old Place d'Armes, the tenting ground and bivouac of those first Creole colonists who gathered about their young French-Canadian commander, Sieur Jean Baptise Le Moyne de Bienville, and here slacked their arms and piled palms and palmettos for their sleeping couches.

Here, too, stands the great bronze horse, superbly poised in the air, bearing in imperishable fame the hero of Chalmette. It is on almost the exact spot where, years before, Count O'Reilly, Governor of Louisiana, ordered to be shot five heroes whose crime was a cry for liberty.

And it was here he burned all their books, with strange ceremonial, because in them they had dared to write the incendiary and disloyal word.

It is an odd, prim, old-fashioned plaisance — this military square. I can shut my eyes and see it now.

Its fences of fabulous wrought iron; its shining white shell walks performing stiff, geometrical figures; its lush luxuriance of vine and tree boundaried and confined by the pruning knife, where petisporum bushes perform feats in millinery, and hedges of box conform to the shapes of arm-chairs and divans.

|

|

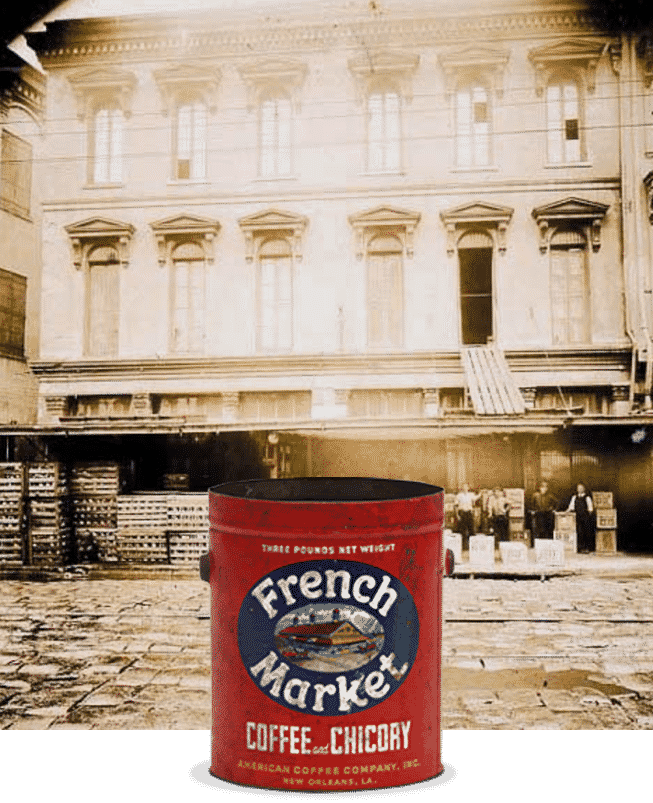

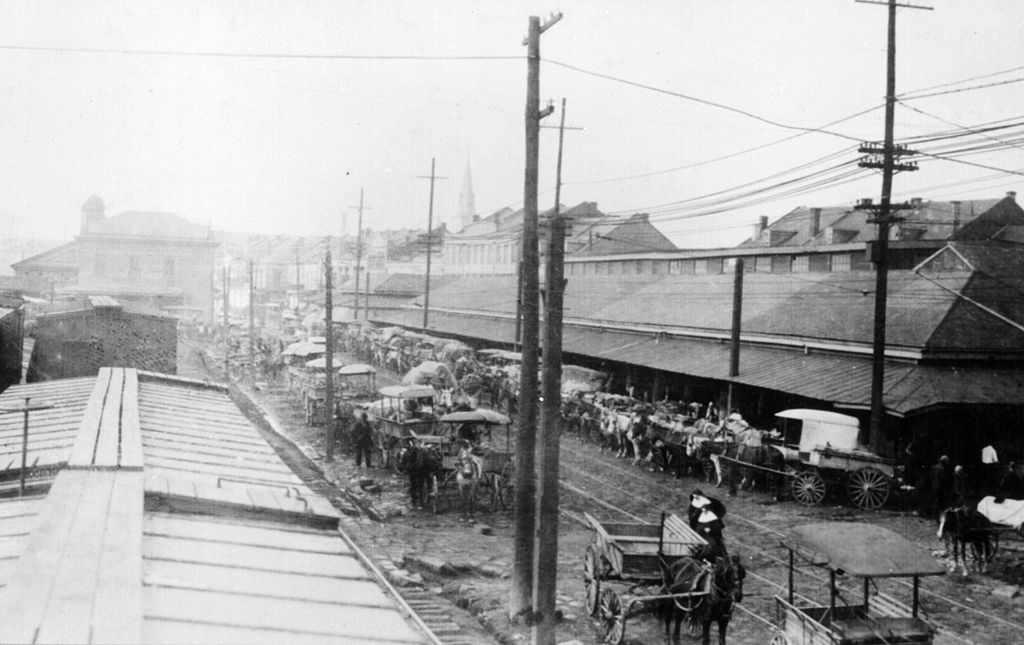

French Market, 1910.

Public domain photo at Wikipedia

|

All is as stiff and prim as if cut out of pink and green glazed paper into silhouettes representing an old court garden of La Belle France. But all is violet sweet, as if powdered over with the fetching fragrance of olive and myrtle, verbena and rose, magnolia and bay, sweet basil and sweet alyssum, petunia and magnolia frescati, lemon and geranium.

All these with roses galore spice the air with perfume and splash the sunshine with their vivid colors.

To the right and left the huge Pontalba buildings are set against: the sky like cameos. And beyond these, riverward, where the blue bodied, red sailed luggers from the Barataria country tug at their tethers, I glimpse the picturesquely huddled colony of roofs and once gilded cupolas of the old market.

The French folk say "Les Halles des Boucheries" — which in English means "The Meat Shops" — and that was the very first name of the old French Market.

It was built much more than a hundred years ago by the town council for the convenience of the people.

Built by the river, for the sake of the huntsmen and trappers who brought their heavily laden boats to rest in the still lagoons of the fallen tide. Built by the church for the sake of the entire community, who congregated there for every service.

When the high-pooped, three-story Spanish galleons sailed into the harbor, the merchants displayed their cargoes of "corn and wine and oil," and silks and laces, in the market stalls. Then here came to buy, the governor's titled dame in stiff brocades; the shaven monk with sack on his back, and all the varied people of a city that was born cosmopolitan.

|

|

French Market, 1915.

Public domain photo at Wikipedia

|

Here, from the beginning, all the small cuisiniers set up on the black, cozy flagstones their braziers of charcoal and brewed over them that all but immortal decoction, fit to be bottled and sold as perfume from Araby the blest — French Market Coffee.

It was and always will be the libation poured by poets and romancers who would tell the story of the old French Market, or paint the bizarre pictures of this historic old place of sales.

At the very entrance to it all is a coffee stall. It instantly gives one the impression that the keynote of the whole French Market is coffee. Coffee is in the very air.

"Cafe!" "Toujours Cafe!"

It is called in satire the Cafe Rapido. From one end to the other of these long halls are marble slab counters with glass backs, filled with impossible pies and still more impossible cakes.

Before these at intervals, are stationary, pewter-lidded bowls filled with white and brown sugar. Farther on are the coffee urns and the shiny tin heaters in which are kept hot and crisp those tasteless, melting crullers of puff paste, three of which go with each cup of coffee.

But it is early for coffee. The delicate-nosed companion by my side objects to even French Market Coffee and puff paste crullers when accompanied by an obligato of Gargantuan rounds of beef and dear little pig babies, beautifully cleaned to be sure, and all ready for roasting, but looking awfully cannibalistic.

And so we stroll on through the dim aisles of the old market.

Time is not old enough to lay the ghosts that haunt the romance-strewn halls of the French Market.

The mellow sunshine that dapples the river with silver, and flecks all the grim, gloomy eaves of the market roof with radiance, seems an oddly present-day setting for the tragedies and legends that cling to the history of the market like musk about Fontainebleau.

At yonder rude bench where those tourist lovers are sitting, laughingly sipping their cafe noir or cafe au lait, once appeared the cowled head and sandaled feet of that old Pere Antoine — Antonio de Sedilla, Spanish priest — whose history is a picture page in the records of the town.

For nigh onto a score of years this sweet, old ascetic, who humbled every desire of his life to the duties of his habit, performed all the marriages, absolved all the dying, buried all the dead, christened and confirmed all the young, and confessed all the living. As he threaded his way along the muddy streets, the people kneeled for his blessing and for the alms he was sure to bestow from the buckskin bag at his girdle.

As he passed across the marketplace or stopped to rest under its cool and cloister-like arches of stone, the people held out to him their vapory cups of French Market Coffee, begging him to touch it with his lips that it might bring them luck.

Twice through his zeal he was suspended, and at last, after he had been absent for many days, he was found praying in a swamp surrounded by alligators, the long, gray Spanish moss tangled in his beard, while the rain dripped from his shaven head.

His people brought him back, and forced his re-installation. When he died he was buried under the altar of the great Cathedral, and to this day tourists stop to whisper softly at his grave and, Protestant or Catholic, breathe a prayer for good luck's sake.

At one time, mayhap half a century ago, each morning at a stated hour there came slowly across the flag-stones of the Rue Hospital, her slaves at her heels like trailing hounds, a stern, set-faced woman with sharp, hard eyes and a regal manner. She wore the hooped skirts, the shining silk flounces and the rich lace mantle of the gentry of that day.

When she stopped to order purple fillets of beef even the butcher's hand trembled as he did her bidding.

"Ma foi" said one, "I should think it would remind her too much of how she cuts off them poor niggers' ears!"

Even then the city whispered of her cruelty.

She was the lady of the grand mansion on Royal and Hospital streets. The whole town knew that she tortured her slaves, cut off their ears, nailed them to the floors in dungeons and garrets — why! the blood stains are there to this day!

After her round of buying for the day she would seat herself at one of the many coffee stands — doubtless often at this very spot. Oh! Do not shrink! It was long ago, my dear!

And here she would sip and sip the clear, dark decoction. Tradition has credited her with always using cafe noir. While all about a whisper fell among the market men and chance early morning visitors. Like one might see the shadow of a passing cloud obscure the cheery sun of noon.

Cable has told, with tragic force, the story of the haunted house of the Rue Royal, and of its monster-hearted mistress, the Madame La Laurie.

At last, when the outraged mob set on her to destroy her, she slipped stealthily from huge pillar to pillar, finally reaching her boat, which carried her across the river, whence she fled to France; the most hated, reviled, dishonored woman who had ever lived in the French quarter.

In the years before the war, when to be Southern was to be proud, rich and gay, the great amusement was the French opera.

The great works of Meyerbeer, Rossini and other masters were given in their entirety. As is yet the custom in many parts of Europe, the opera began at half-past six in the evening and lasted five or six hours.

At its close it was the custom for the beaux and belles, well chaperoned by mothers, cousins and aunts, to come trooping across the narrow Passage St. Antoine to the French Market coffee stalls for the elixir of life dear to the Creole soul, cafe au lait or cafe noir.

What a pretty picture it must have been, these dim stalls whose midnight gloom seems only acccentuated by the broad flare lights fastened near the salmon-tinted walls; the high, round arches festooned with garlands of silver-skinned garlic; green cabbages piled like so many decapitated heads across the stalls; and at the marble counter, perched on high stools, Angele and Elmire and Doudouce, laughing, rose-sweet, little French phrases escaping their red lips as broken pearls might pour from a vase, their young, fair faces rising from their opera hoods like a new lily slips from its sheath of green.

Today, as we sit here, out in the noisy entrance to the bazaar market, a forlorn, toothless, grizzled negro, tremulous and foolish with age, tries to sell some very bad pineapples, which the fruit-dealer across the way has cast at him for alms.

He arranges them on a board and lifts up his little, thin, cracked voice, as he cries:

"Oh-he! Come Mamzelle-zelle-zelle! Vein ma petite! Oh, come! Whar is you mamzelle Elmire? Whar is you, ma petite Doudouce?"

Across the stalls, where sit those New York tourists sipping their French Market Coffee, comes the perfume of Java and Mocha — or the richer, fuller fascination of the berry from the Pan-American tropics — and over it on that airy bridge that perfumes so often build for me, to carry me back to the "once upon a time," I see again the rose-sweet faces under the salmon and gray arches. I hear again the strains of "Robert," and glimpse the jasmines and violets lying on innocent girlish hearts.

"Ah! Mamzelle-zelle-zelle! Where are you, ma petite"?

But a little further down the paths of time we can in fancy hear the tread of horsemen in the sunny street. And through the stone arches of the old market — had we been there — we might have seen in brilliant but mud-stained uniforms, impetuous Jackson — Andrew Jackson — and his officers fresh from the field of Chalmette. Out there, dead, in the blood-soaked trenches lay Pakenham, the English general, brother-in-law of the Duke of Wellington, with thousands of his men.

But here the victorious leader stops his tired, yet happy officers and men, and calls loudly for every drop the market affords of French Market coffee, hot from the fire. Well have the troopers earned it.

On another summer evening came a laughing, jesting group slipping across from the old Hotel St. Louis. The dark-haired, eagle-visaged man whose every syllable was music in the soft summer air was Henry Clay, he of the silver tongue and entrancing speech. Escaping from the great banquet given in his honor after his glowing tribute to the beauty of the women and the bravery of the men of the South, he had bethought him of his cup of French Market coffee, and inveigled a few of his friends to accompany him on a schoolboy escapade to get it.

Small wonder these gray old walls are soaked and steeped in romance! Small wonder that the spicy fragrance of that historic old coffee blend should raise the ghosts of years that have gone!

Would you like to go through the market? As one might have done a century agone?

Let us then have first just a soupcon of the famous coffee to sur our imagination, so that in place of modern clothes and modern faces we may, perhaps, see the people of the days gone by. For the French Market itself is as it always was. Time has not changed its gray arches. The centuries have passed lightly over its jumbled roofs. It will look to us as it looked to old Pere Antoine, to Madame La Laurie, Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, and sweet Elmire, Angele and Doudouce.

Are you ready? ¶ Here on the shallow stone step of the Place d'Armes one finds the real beginning of the French Market.

Here a Sicilian in her native costume looks at you from slumbrous eyes that hold no hint of mafia, and tempts you to let her twittering parrakeets tell your fortune.

Here an old crone, sitting in the sun, holds up a curved palm, so hard, bony and polished it might be taken for a bit of cocoanut shell. In its hollow are two sea beans. "Dey is de male and de female! Dey is sholy good luck! One sinks while de odder swims!"

It is true. Put in water one sinks, and the other precisely like it, swims. As for the good luck! Quien sabe? Who knows?

At the corner, where a sort of delicatessen shop evades or ignores the Sunday law, a dago offers bananas at ten cents a dozen; and a beggar with an old, ramshackle organ wheens and wheezes out a persistent, if sadly frayed and tattered Trovatore.

The pile of buildings that composes the French Market consists of several different edifices — the Meat Market, the Bazaar Market, the Fruit Market and the Vegetable and Fish Market. All of these are under different roofs. The medley throng of life that goes on is as picturesque, as unique and as vari-colored as if overhead were the gay tents of Constantinople stalls.

What a mingling of people it is!

Mistresses with their maids; quadroon dames still mumbling prayers left over on their lips from early mass in the old Cathedral; black- veiled sisters, aye! and black-skinned, too, with crucifixes hanging over their broad white linen collarettes and rosaries slinging on their wrists. Orphan children carrying baskets from the markets, tourists trying and pricing everything, young girls in bevies, fathers even at this early hour treating their flocks to huge wedges of yellow pound cake with great glasses of sarsaparilla soda.

Here is an old woman with news-stand neatly arranged, showing all the journals of the day with, of course, the place of prominence given to that Nestor of all journals — "L'Abeille de la Nouvelle Orleans."

But here is the Meat Market.

The roof is supported by a forest of huge, square brick pillars that divide it into a center and two double side aisles. Around these pillars the stalls are built, with big lockers underneath, and by each one is a section of a cypress tree of enormous size which is used as a cutting and chopping block. Overhead are pulleys, ropes, hoops and grappling tackle for handling the half of a huge beef or hanging it up when the market closes, as the law requires, at mid-day.

After each day's sales are over the wooden blocks are scraped clean, and by this process many of them have in the course of years been worn down into deep basins.

Here at one stall, dainty as a dainty chatelaine, in his linen blouse and linen apron, a butcher is deftly trimming mutton chops. With a turn of his wrist he loosens the meat in a long strip from the bone, and ties it around it, thus leaving a neat handle to be decorated with a paper frill after it has been broiled.

Near him a iittle crowd of boys stand, anxious eyed, while another man slips a noose over their pet goat's horns and lifts the struggling animal to weigh it on the scales. He offers to pay them so much for the beast, which he may or may not palm off on his customers as: "Real spring lamb, so help me, ma'am!"

In the ear is a babel of voices mingled in a shrill, untranslatable Volapuk. The air is filled with all the perfume of Araby, strained through carcasses of beef, goats, sheep and pigs. Before the eye is a moving throng of all sorts and conditions of people, filling the long aisles, with their apparently endless vista of beef in fillets, sirloins and sweetbreads; cutlets ready larded for beef a la mode, or "daube" as the Creoles call it.

At the end of the meat market a tiny flagged plaza spreads its twenty feet of width between the butcher stalls and the bazaar of the dry goods market.

This little gray bit of foreground is one of the most picturesque places along the market side.

It is here the Indian comes, that stolid, surly, usurped Queen of the St. Tammany Choctaws, accompanied by her women. And it is here they defer — but only for money's sake — to the appetites and esthetic tastes of the white woman and the white man, and sell them their garnerings of forest lore.

They sit on their fat haunches, their wiry black locks hanging over their flabby jowls. All about them are the wares they have for sale. Pounded leaves of sassafras and laurel, forming that dark green powder, "Gumbo File." Bricks of palmetto roots that the conservative minority of housewives still prefer for scrubbing brushes. Fragrant fagots of sassafras, so good for a tisane in springtime; with bunches of dried bay leaves for flavoring soups and sauces and so delicious to place among one's linen and let it grow lavender-sweet as the days go by.

Last and best of all, about them lie in green and bronze and amber piles, the sweet swamp canes and ribbon grasses woven into wonderful shapes and delicately dyed with the vegetable dyes, whose formula none but these Indians know.

These baskets are of curious shapes. Here is one made in the sharp, three-cornered design, cut like a triangle. There is another like an elbow of a stovepipe; a third fashioned into a wall pocket for some lady's dressing case. Towering over all these are the huge Ali Baba baskets, square at the bottom, round at the top, and fitted with square covers that pull down like a Dutch smoker's cap. Each basket is amply large to hold a portly member of the Forty Thieves.

These Indians are staunch Catholics, made so by a good priest of blessed memory, one Pere Roquets, who died awhile ago. To this day they hang his grave with bay leaves, wild lavender and sassafras.

They sit here stolid and dull, in true savage taciturnity, their babies on their breasts and backs; a queer row of amber idols interpreted into the heart of modern civilization.

When the market house bell rings at eleven-thirty to give notice that all must get ready for the closing, they rise, load up with their wares like typical beasts of burden, and — huge mountains of baskets, sacks of file, powdered sassafras leaves and bunches of bay — trudge off to their camp on the brown Tchefuncta river.

But here is a coffee stall, dropped down in this cozy corner for just such passers-by as we two.

Why, nonsense! Have another cup!

Hurt you? Not a bit of it ! The market men drink it all day long — ten to fifteen cups a day. Sweet Angele and petite Doudouce would drink many cups at midnight, after the opera, and sleep like the babies they were, all through the soft summer night.

This is French Market coffee, you must remember, not a bit like the ordinary coffee you have at home. They do say that in France and Austria there is coffee resembling French Market coffee. Of that I do not know. I only know there is only one real French Market coffee for me.

Let us cross into the Bazaar — the Dry Goods Market. Isn't it queer? Its old French name was Bon Marche — "Cheap Sales." And many a modern department store has appropriated the name. But not in all the world is there such another as this delicious spot.

Many a rich merchant of olden days had here his beginning. Time was when these small shops were stocked with silks, laces and real linens. Even now it is a place of pretty confections, to tempt the picayune from one's purse.

What a land of dry goods it is, to be sure!

It is as if one went into a wonderland where everything was linen and lace and pins and needles and combs and calicoes and threads of cotton. It seems like a giant case wherein are hung hundreds of gay bandannas while pyramids of canvas and hose and ribbon are set all about. Where shopkeepers seemed condemned to eternal measuring and snipping of "Guinea Blue" calico, and where pretty, laughing girls are forever trying on dainty, ruffled sun-bonnets. Where the gay scalloped oilcloths for Marie's kitchen shelves glow like red flowers and where the "real Madras turbans" are kept.

These are the genuine, old-time, gorgeous bandannas, all purple and green and gold — the royal colors of our Carnival king — and sacredly are they preserved for those high-toned old mammies, who can tell real Madras by the feel of it, and who would no more wear an imitation than a queen would wear a spurious crown.

How slowly one penetrates these linen tunnels, where even the voice falls back, unreverberative, until at the distant end a gray eye of daylight looks in and feebly burnishes the ever-delightful crockery stalls, where are the quaintly shaped jugs and absurd cups, with marvelous magnificence in the way of cheap basins and gorgeous bowls that to the uninitiated might pose for the ancientest delft that ever sailed from Holland with the Pilgrim Fathers.

These delicious crockery stalls are like the pottery market of Weisbaden, the damaged delft sale at Doulton, or the wonderful Swiss shops of Swiss Thun. Fancy a whole toilet set for a dollar, a dozen pieces of glassware for half that sum, or a real imitation cut crystal rose bowl for a couple of picayunes. Surely no curio collector's cabinet is complete without a fascinating hideousity from the china stalls of this market of markets!

The outer edge of the bazaar wears a fringe of flowers, a sort of marginal note of bloom, in bouquets and potted plants.

Here are street fakirs, fortune tellers, and venders of those sea shells that under all the market clamor still whisper the low music of the sea that lingers on their coral-pink lips, a memory of the green Adriatic or the blue Mediterranean.

Near here are also the first of the fruit stalls, but these are only the approaches of the fruit market, the "little fruit market," as it were; just as in the ante-bellum days the red-brick town of St. Martinville on the banks of the Teche was called the "little Paris."

One must cross the muddy streets to the market house number three for the real fruit market of the town, passing en route the old pineapple peddler, who keeps up all the time his mournful call for those mythical "Mam'zelles Elmire and Doudouce!"

What a piece of color it is, this fruit market of the old faubourg. Tadema might have spilled here his palette with all its waste of gold and saffron and yellow, for one sees his colors on orange and lemon and banana, with all its rust-red dyes on cocoanuts, mangoes, guavas, dates and plantains, and all its vivid greens and scarlets glowing on apple and pineapple.

Each stall has a remarkable decoration of oranges piled up like cannon balls on a parade ground, or like the imposing front of an Egyptian Cheops. A nutty fragrance floats in the air from the bunches of bananas that swing like pendulums from the eaves, or which is emitted from the wedges of juice-dripping pineapples that, cut in sample slices, retail at a picayune apiece.

Here is another coffee stand. Hear the familiar monotone, "Cafe noir" or "Cafe au lait!" Almost one is tempted at so short an interval to sense again that delicious coffee memory that has come down to us across the centuries.

But let us first investigate the squawking, calling poultry stalls. After awhile I will take you to a coffee stall where you shall have a farewell cup of such coffee as can be had nowhere on earth but in this old French Market. See those great, fat capons hanging by the legs, above platters of giblets for gourmands! How those cages of geese and Creole spring chickens knit their continuous scream and chatter into the warp and woof of the human voices about!

Such a noise! Let us go into the bread stalls. Here is a fit and proper accompaniment to possible pate de foi gras! What a mountain of crusty loaves! Truly the breads of all nations are to be had here!

Here can be had French rolls delicately small; huge rusks as big as Cheshire cheeses and as heavy; long, slender braids of bread that must be pulled apart, never cut; black bread, brown bread, Dutch cakes, American bread, mixed with milk; French bread, raised with only a flour and water yeast; bread without any yeast at all; every loaf smoking hot from the oven, piled on shelves, or in big willow baskets, and giving out a wheaty smell that is better than caviar for the appetite.

Very curious are the grocery stalls of this old market. They form a pyramid of color and at the same time a study in comestibles. At some of them even "quartee brade" is still solicited. That is, five cents can be used to purchase four different articles; say a little garlic, a pinch of cayenne, salt, and enough barley to flavor broth. That is the meaning of "quartee."

On these stalls are sold more varieties of macaroni than there are days in the week, from a fine, red-shredded sort up to a broad flat band, and a paste cut, as Juliet wanted her Romeo — "into a little star."

The list of grocery "sundries" is really more curious than inviting. There are dried capers, dried shrimps from the Malay camps on the Grand Chenier, olives in bulk and pickles in brine, mushroom chips and cocoa chips, salted black "gaspagou," and a curious black olive that has been boiled in olive oil, and that is perhaps the greatest thing under the sun.

You do not "know beans" even if Breton bred, unless you have investigated the beans of the French Market. They range from black- eyed peas — which are really a kind of bean — to the kind that go so well in a "Jambalaya," or are so fine made into a salad, on which, after the recipe of the elder Dumas, you have expended "vinegar like a miser, oil like a spendthrift, and the strength of a maniac in the wrist."

It is in the grocery stalls, too, that the thrifty Creole house-wife, who believes in buying groceries in small quantities, gets her ham by the slice, breakfast bacon by the rasher, enough cheese to sprinkle her spaghetti, and enough caviar to spread those dainty sandwiches of salted cracker that precede dinner in good society and whet its appetite.

Beyond the grocery stalls in the last of the "Halles" of the old market, are the vegetable stalls, the fish stalls, the flower women and the principal coffee stands, where the finest coffee is to be had.

The aroma of a foreign country is in these last "Halles". Fat French women potter over the damp flagstones. The endless click of their carved wooden sabots taps the pavement like the delicate croak of rain frogs.

On the vegetable stalls one may find color enough and detail enough to have satisfied a Teniers.

The faded red column that helps to support the roof wears at its capital a gray drapery of cobwebs looped loosely over the graceful iron brackets that spring toward the roof. All the rich wonders of an almost tropic garden are piled about this column.

Shallots savory enough to tempt one to become a very unTennysonian "Lady of Shallot," hang in bouquets; crisp salads, chickory, lentil, leek, lettuce, are placed in dewy bunches next radishes, beets, carrots, butter-beans, alligator pears (a sort of mallow or squash), Brussels sprouts (idealized cabbage); posies of thyme and bay and sage and parsley; a bunch of pumpkins; and overhead, like big silver bells strung on cords, those everlasting garlics braided on their own beards. Often in the market, in order to further a sale, a pretty dago girl hangs across her shoulders half-a-dozen yards of garlic rope. Deftly she twists it over her arm as if it were a cobra, making a picture pretty enough to paint.

On the flower stalls are tall, green tin hoods spiked all over with hollow handles, in which the flower women stick the stems of their stiff bouquets. The ones that are superlatively fine are set in a gay petticoat of paper lace and are perhaps sold to little grisette brides.

It is an amusing picture to see a sedate gentleman standing meekly while a coquette of a flower girl — fifty years old if she is a day — leans puffing over her own stomach to fasten in his buttonhole a boutonniere of Parma violets whose fragrance floats like a benediction over the noisy stalls.

The fish market is a charming study in grays and salmons and pinks and silver. It is perhaps the greatest fish market on the continent — almost I had said in the world.

The glistening slabs of gray marble reflect the overhanging pent roofs, and Spanish mosses are twisted about the slender bars of iron on the stands. In baskets of latannier lie blue and scarlet crabs; in others are dark red crawfish looking like miniature lobsters. On beds of moss, like smaller lobsters still, the delicate river shrimps are fighting for life. They may be still powdered with the grits that tempted them into the fisherman's net. Croakers hang in silver bunches; flat pompanos, their sleek skins shining, lie side by side with bluefish, Spanish mackerel, and trout for tenderloining. A large sea turtle has just been cut up, and the still quivering steaks and leaping golden eggs lie in the mammoth shell that the women of the sea coaSt would use as a cradle for their babies.

Flounders caught at night by torchlight, and which are as delicate as an English sole, hang next to the queer sling-rays whose harpoon Stroke is poisonous. Nearby is an immense grouper that, weighing three hundred pounds, acts as an advertisement and attracts the cheap custom of darkies and dagos.

At one Stall porky-looking chunks of meat are being eagerly bought by colored people. It is from a nice, fat alligator that, well boiled, would deceive a cannibal, it is said, so like is it to human flesh.

On the game Stalls hang papabotes — which is Creole for "upland plover" — ducks, pelicans, grassets, sea snipe, ’possum — dried or freshly killed.

If you buy crabs, by the way, the dealer throws over them a handful of Spanish moss in which they tangle their claws and cannot get away.

Hereabout are most of the market eating Stalls. At some of them elaborate meals are served, while others are solely for the serving of French Market coffee and cakes.

Big, round furnaces Stand on tripods and are filled with fires of charcoal. Over these, in skillets, women fry fish, cook oysters, or ham and eggs. In reserve are dishes of potato salad, corn beef, mutton (that may be the boys’ goat), and a mass called plum pudding.

On a separate fire the coffee-pot steams.

And now for that farewell pot of coffee I promised you! This is the spot where we will get in it perfection!

Here, or hereabouts, "Old Rose," whose memory is embalmed in the amber of many a song and picture and story, kept the most famous coffee stall of the old French Market. She was a little negress who had earned the money to buy her freedom from slavery. Her coffee was like the benediction that follows after prayer; or if you prefer it, like the benedictine after dinner.

It was something to see that black "Old Rose" pile the golden powder of ground French Market coffee into her French strainer — a heaping tablespoonful for each cup — and then when the pot was well heated, pour in just two tablespoonfuls, no more, of boiling water.

In ten minutes this had soaked the coffee, and then, half a cup at a time, the boiling water was poured on and allowed to drip slowly. The result would be coffee, black, clear and sparkling — ideal French Market coffee!

"What is it that you will have, madam?" Hark! Here comes the courtly old servitor. And then for fear we may not have understood him he repeats his question in musical French:

"Que voules vous, Madame?"

All about us is the din of the old market.

Across the stalls is a French lady knuckling the cheese to see if it is fresh.

The sedate, elderly gentleman is still being pinned with his boutonniere of violets.

Old Sister Mary Josephine, who has just come from the convent and asylum fingers anxiously the yellow yams on the counter. They would be fine — she thinks, no doubt — for the children's feast day.

A parrot, tumbling on his tin hoop, screams: "Comme sa va?" (how are you?), at every passer-by.

Opposite, at another coffee stall, a beautiful young Creole belle has seated herself with her mamma. Mamma is on one side, her prayer book and rosary on the other. Truly she is safe between the law and the prophet. Something glistens on her forehead. It is the cross of holy water she has just dipped in the gray cathedral yonder.

"What will you have, madam?" again re-questions the old, stately proprietor of the French Market Stalls.

"Shall it be black coffee, or coffee with milk? Cafe noir or cafe au lait?"

The steam curls up about your cup as if you had invoked a genie; and as you sit and sip, and sip, across the noisy chatter of the town and the French Market you hear again the sad, quaint, tremulous cry of the old negro with his pineapples:

"Oh! Mamzelle Angele, whar is you? Whar is you, ma petite Doudouce?"

Notes

- Atolycus. Autolycus, son of the Greek god Hermes, was a hero best known as the grandfather of Odysseus. Like his more famous father and grandson, he was known as a trickster, liar, and thief.

- Place d'Armes. Now called Jackson Square.

- Royal and Hospital streets.The infamous Madame LaLaurie, widely considered to be America's first serial killer.

Text prepared Winter 2013-2014 by:

- Denver Davis

- Kurt Farlee

- Carli Kinman

- Bruce R. Magee

- Kristen Reed

- John Lewis Sams

Source

Cole, Catharine. The Story of the Old French Market. New Orleans: The New Orleans Coffee Company, 1916. Internet Archive. 19 Dec. 2008. Web. 31 Jul. 2013. <https:// archive.org/ details/ storyofold french00 field>.