Catherine Cole.

“In the West Countree.”

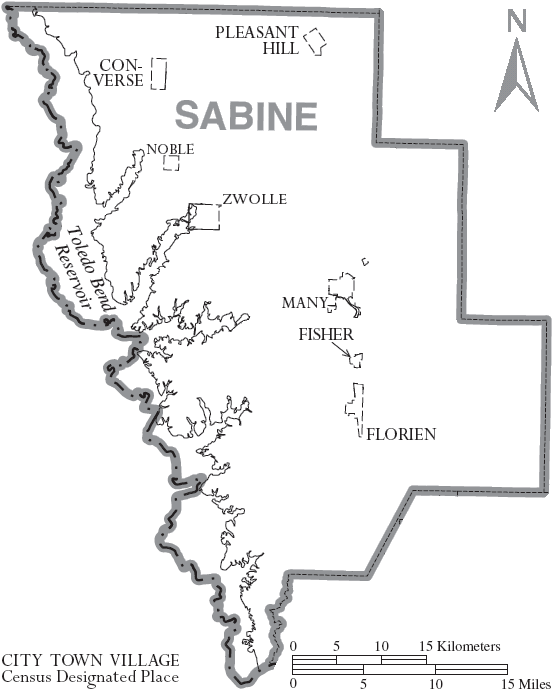

Sabine Parish La

Robeline — Many — Sodus — Hamilton

The Masonic Institute at Historic Fort Jesup

A Town of Widowers and a Night at Wigginses.

I wonder if any one beside myself regards as a trifle out of the perpendicular of the common-place for a lone woman, accompanied only by a very small darky boy, to be making in a buggy the tour of a grand, lonesome and underpopulated state: It is true this modest journey lacks the �clat that might attend a voyage around the world, but while it is happily free from accidents, it at least has compensation in the shape of an endless chain of homey incident, that is, after all, the charm of travel.

In the first place I am always put to the necessity of explaining myself. Naturally, even the most unsuspecting have their small and innocent curiosities concerning a lady who avoids railways as she would a plague and who scours the interior country as persistently as a drummer. I am constantly asked “who am I drumming for;” while no sooner do I insert into the supposable gray matter of my driver’s cranium the fact that I am only traveling to see the land than I must change drivers and begin all over again. For the fast five days my small Jehu has been one who regarded it as a personal injury that I resisted all his temptations to “drum.” Every day he would say to me “Ain’t you gwine to drum today?” and, “I’se in the habit of driving drummers, I is.” Last night when I dismissed him at Robeline with a well earned pour boire, I heard him, as he drove away from the hotel, inform an idler that he and the lady had been drumming for a newspaper.

Edward and I had some rare talks on that trip. Often there would be a stretch of fifteen miles through unbroken forest, and the boy had much to say. I learned lessons in physics I never knew before, as for instance: When lightning strikes a tree, at the end of seven years the thunderbolt rises out of the ground by the tree. “My uncle has got one,” said Ned, “It is like an iron aig, and if you keep it in a barrel of meal, no matter if the rain does leak into the barrel, the meal won’t never sour.”

But flattering things happen also. The other afternoon, after a ride of forty miles, I crawled, benumbed from this long sitting in one position, into the parlor of a country hotel. “As soon as I saw you,” said my hostess, who had a baby on her hip, “I thought you might be ‘Catherine Cole.’ They say she’s a-buggy-riding all over the state.”: After that I modestly admitted my own identity.

On another occasion — that was two nights since — we drove up in a blinding storm to a log-cabin home in the heart of the forest, where the same name got me a doubly warm welcome. After an hour we had supper. In the center of the table stood a tin pan as large around as the full moon looks to be. “ I made that there pie especially for you,” said my hostess. To say that the pie was huge, hardly expresses it. Why, you could have buried a 10-month-old baby under its blanket of paste. Interiorly it was composed of apples, pears, peaches, home-made molasses and other handy ingredients held down by a coverlid of dough that would have exhausted Gargantua. I smiled and ate all of the pie I could possible hold. We had the rest of it for breakfast the next morning.

It was also a log-cabin home that I came out early in the soft fog of 5 o’clock in the morning to take my bath. A basin on a bench, a bucket of sparkling well water, cool and crisp as frost, a hastily doffed pillow case for a trowel, were the all-sufficient conveniences. The family stood around sedately while I “used Pear’s soap,” violet water and tooth paste. I was as dignified as they, and I must add, as unembarrassed. There’s nothing to be ashamed of in being clean, is there? Nothing like roughing it to take the mock out of one.

I look back with something of amazement, a good deal of pride and a vast deal of pleasure, on my travel record over the past five days. In a buggy, in company of the redoubtable Ned, I have been to one side of Sabine parish to the other guided by various cir...[cumstances and priveleged to].....journey it enough to laugh at the fogy statisticians who are ominously croaking in the great magazines about the overpopulation of the world. The world is not coming to an end for want of elbow room — at least not yet awhile. Such splendid, beautiful and rich parishes as Sabine are holding less than fifty persons to the square mile. If, say, the state had some practical was of inducing or attracting immigration, say from Belgium or our own northwest, why, the newcomers landed in the lovely country of Sabine would think they had been carried to a new El Dorado. With the building of a single log railway through this parish its superb pine forest and upland, that now find little or no sale at from 50 cents to $3 and acre, would become of almost fabulous value, the trees being on the best varieties and of uniform enormous size. Cleared, these lands are productive, and yield the farmers an easy and comfortable living. Of course a sensible man does not expect to make a lottery fortune at farming anywhere, but the farmer in Louisiana even on the poorest land, can live better on less work, and make more money at t smaller outlay, than he can in Minnesota, Dakota or California on the best lands. It is impossible for me or any other newspaper writer to make a statement more incontrovertible or more easily proved than this.

The other day I stopped in the road to talk to a small farmer, attracted by the homely comfort and thrift of his home. It was a neat little board and log house, with a mud chimney, as red as Etruscan gold, at one end; a slanting porch in front, and drooping from the pent roof a curtain of delicate fern-like cypress vine. A woman was spinning on the porch, now and then stopping to give the cradle a rock. A lot of peaches were drying in the sun. Huge watermelons lolled in the patch at the end of an orchard. Cotton in full glory of pink and straw colored bloom stretched away behind the rail fences and lads in the corn field were pulling fodder. He told me he had eighty acres of land and had paid for it, house and all, $300. He would make this year 6 bales of cotton and 300 bushels of corn. He used no fertilizer. Nobody did in the parish, and an average crop was three-quarters of a bale to the acre. The chief trouble was getting his crop to market. The nearest railway was twenty miles.

With the exception of a small cut across the northeastern corner of the parish made by the Texas Pacific Railroad, Sabine parish has within its limits neither railway, telephone nor telegraph.

Many, the largest town and parish seat, has a cultured, wealthy and most hospitable people, but even Many is sixteen miles from a railway. At picturesque Fort Jesup is located one of the finest male and female schools in the state. It was founded by the Masons of Sabine parish and is under their direct care. It is called the Masonic Institute for boys and girls, and its president, assistant and chief teachers are all graduates of Sewanee University. This is enough to establish its claim as a school for excellence, deserving the patronage of the best people in west Louisiana, and its maintenance is a source of pride not only to the Masonic lodge of Sabine, but to the people of a state where education is not always the matter of primal importance it should be.

I may say that my outing in Sabine parish really began with Many, and though it was necessarily preceded by the 16-mile drive from Robeline. The sun was hardly free of the pine tree tops that fringe on the new railroad town of Robeline before we were on the way. In my notebook I find these lines, beginning: “Bundled out of sleeper more dead than alive with sleep. Stumbled up a red hill to a hotel. Dozed on a hair cloth sofa, in a parlor full of untidiness left over from Sunday night, while a young man slicked up a freshly vacated bedroom for me. Went to bed for a half-hour in order to wake up. Imagined the bed was still warm and human smelling from whomever had slept there last. Got up and tried to build a castle in the air over the five days carriage ride before me. Castle wouldn’t build. Had a country breakfast of hot soda biscuit, fried chicken, country butter and delicious cantaloup. This heartened me up. Paid my bill and started; felt like a peddler when I saw how funny my steamer trunk looked tied with a rope on behind the buggy. Crossed the railway track in safety, thank heaven! Took a long breath when I recollected we couldn’t possibly do such a thing again for four days, but expect in the end to have the horses run away. What a curious combination of character it is that makes a woman who is afraid of horses, storms, snakes, water, lightning, bears, wildcats, etc., love to go roughing it alone all over the wilds that almost no man knows.”

And then follows a lot about ambling over the lovely hills, with the little liquid murmur of the running water cooling the air and soothing the ear with the uneven, picturesque red road unfolding in curves like a fairy story of nature around the tangled coverts of bloom and bramble, with the dense deep blue sky hung like an Arab’s tent on the feathery tops of tallest pines, and swinging down between them an azure far-off impenetrable curtain of exquisite and tender color.

I am afraid I shall have to be writing a vast deal about the pine forests and the sky. It seems I have seen almost nothing else. Surely nothing else as lovely. Shall I [ever ] forget those gentle [forests of] Sabine, set thick with giant pines, the sun casting long cross bars of shadow on their evergreen slopes with here and there a bent sapling as if giants had been putting up a wondrous set of croquet hoops for a game in the moonlight; the solemn stillness of the forests; the awful fear of them when storms come on; the little clearing that marked the complaisant yielding of nature to man? Why, the fences were pine, the houses were pine, where a traveler had camped out his bed had been pine boughs. If accidental death came it was likely to take the shape of a falling pine. Here and there a monster lay prone, digging his lone, dead arms into the earth; here and there a fat, bare trunk shone like a tower of gold in the sun, oozing resin like honey, or a more precious amber, that spilled itself in beads as if the old tree was telling off a rosary of resin drops, and finally thanked Providence for getting me out of it all to sit in the little hotel in Robeline, writing it up while waiting for my clothes to come home from the wash before starting off again.

Many a brave old soldier can tell you more, gentle reader, about Fort Jesup than can I, who only know that Taylor and Grant and our own Jefferson Davis have each held it. It is on the brow of a hill. The forests withdraw to make room for lovely, sloping meadows almost as broad as the moors of English Devonshire, and now all soft and tawny with long feathery, sun-burnished grasses. It was like being in Tennessee to see the long, low roofed houses built upon deep foundations of stone, slabs and cobbles of crude, gray and brown and purple rock easily quarried from some neighboring hill. We had a glimpse of the ivied ruins of the old fortress. They are now an historic beauty spot in the grounds of Mr. McIlwaine, and directly behind, on the highest point of the hill, with no air less sweet than that which teems with the balm of these beautiful pine trees that are the glory of Sabine, reaching its halls, stands the Masonic Institute. Its president, Mr. Colden, is a brave man He declines to rush pupils through school or to graduate them before they have something to graduate on. It is a pity every teacher in the state is not so stoutly opposed to a superficial top-dressing of education.

Many is a sweet, sleepy, rambling old town, blinking on the hills very much like a comfortable and handsome cat. I fairly luxuriated in its decent quiet. There are no saloons in the parish, and there is no drunkenness. Prohibition really seems to prohibit. The homes are pretty and flowerset, and the people are neighborly, kind and refined. the business is confined to three large stores of general merchandise. The editor of the Sabine Banner, Mr. Don E. SoRelle is also a prominent lawyer and two or three other legal men of note reside here. Mr. SoRelle’s genial wife, by the way, is one of the handsomest women in West Louisiana. In the heart of the town is a little Catholic church, whose beloved priest, Father Aubrie, has been for years a guiding spirit of good in the town. Only the other day, after a dreadful drought had ended in rain, the little church bell rang out calling the people to a thanksgiving mass. It is due to the efforts of the lovely young ladies of Many, that a Protestant Sunday school is maintained, and that the Protestant graveyard is kept in repair.

Once, while writing similar articles for the Picayune, I had a letter from an Iowa farmer which has been to me a sort of guiding star ever since. It was full of the intelligent questions of a possible immigrant. If I were answering him from Sabine I should say: “Dear Sir — Sabine parish is jam up to the Texas line. It is almost entirely composed of excellent pine uplands. The pine forests are large; the pine trees of mammoth size. Here and there are stretches of hilly meadows. The total assessment of whites is $926,125, of colored $5,200, total $961,875. Thirty five thousand two hundred and sixty acres of land are under cultivation; of uncultivated lands there are 496,924 acres! There are 2150 poll tax payers in the parish and 2924 white school children and only 894 black. The total parish taxation is 9 mils There are good public lands subject to homestead entry, plenty of school lands to be bought cheap. There is not a saloon in the parish. The public school system is poor. A man can buy all the land he wants at $2 an acre. There are many lakes and no finer fishing in the country. Peaches, apples and pears grow finely. Melons average 35 and 40 pounds each. A thrifty man can raise everything his family can use except tea and coffee. A good horse will cost forty or fifty dollars, a cow ten or fifteen. In the forests are oak, ash, elm and beech and walnut trees in great plenty. Thousands of bushels of walnuts go to waste each year. Game includes deer, foxes, bear, partridges, geese, etc., in abundance. Even in the towns no one has to pay for fuel. Sweet potatoes, corn, oats, rye, pumpkins grow profusely. Clay peas yield abundantly and sell at $2 a bushel. The chief fault of the people in the parish is a lack of progression. They need intercourse with a hustling colony such as could easily be introduced here. The parish is sown thickly with springs of pure water. There are also hot and cold springs, lime and sulfur in the northern part. Much land is owned by foreign owners. Millionaires in London, New York and Cinncinati dipping into the future far as human eye can see, have gobbled up thousands of acres. The health of the parish is excellent.”

I think in the foregoing facts I have told all any immigrant need know of a new land that appeals to his eye and pocket. For the statistics I am indebted to Mrs. James Tramel, late assessor of Sabine.

It was a dismal wet day when Ned and I and the ponies said good-by to Many, and set forth on our journey. Merely walking to the buggy depressed my rather indiscreet blue gingham into a sort of pulpy squashiness that made me bless the washerwoman who had put starch into it. My beautiful hostess, a living image of Niobes, without her tears, followed me to the gate with a box of lunch and pleadings that we would wait until the storm was over. Her old, black cook, Aunt Lucy, stood whining on the gallery prophesying a cyclone. I enjoyed their distress. It made the journey look so big and important. I was afraid to go for fear of the storm, and afraid not to go for fear I’d miss something happening. At every crack of thunder the ponies laid their ears back as if ready to run. I’m sure horses have taken a dozen years off my life.

In my luggage was included a candle, some matches, a clock, a map, a small frying-pan and a bottle of hartshorn. All these are for the emergencies of a night that never overtakes us, a sun that never really fails us, a road the has not as yet really evaded us,. a snake that has not bitten us, and a starvation that has not yet appeared. Although if we grew hungry in a pine forest I assume the only thing we could do would be to melt down the candle and fry young pine cones. Through the rain I piled in, and bunched myself up somehow amongst the traveling-bags, rain-coats, umbrellas, lunch-box, and a tarpaulin to keep off the rain. Ned turned to me for instructions. I pointed a vague finger northward. “Go that way” said I, as grandly as if I owned the universe and knew every cow path on it.

Winding over shallow hollow and gentle slope of hill our rough little phaeton and fat little ponies made their way. The rain got behind us, and the sky came out like a baby from its bath, all new, sweet and clean. All about were forests of ash, dogwood, elm and beech. These trees have a particularly airy and delicate foliage, mostly on the upper sides of the branches that spread out like pale green mists, and in the sunshine cast an exquisite tapestry of shadow over road and pool and moss grown logs. One could look far into the woods sleeping soft an sunny with perhaps a bird dumbly glancing on ashen wing under the shelf-like branches of a spreading beech. I have seen such forests in English Warwickshire. Not many realize that we have such beautiful scenes within a few hours of New Orleans.

After we had gayly trotted on for ten miles or more we stopped to ask the way to Marthaville. Not that we were going there, but simply to make talk with a native. The house was a cozy log cabin set under a cluster of oaks in the heart of a yellowing corn field. A little old man, with a faded underbrush of whiskers sprouting from beneath his chin, a fashion that always struck me as being particularly uncomfortable — like a ruching crowding out the neck of one’s dress — sat smoking on his porch. He was tilted back at that expressive don’t-care-a-continental angle that is not to be pictured in mere language. “Ef (puff) yuis goin’ to Marthy’s mill (puff) yuis air almyhty long ways (Puff) off. It’s about thutty-two mile I should surmise. But ef you air goin (puff) to Sodus (puff) keep on till you come to the sluice, turn ’round by the branch till you pass an old field and then take the second fork to your right.”

I had vaguely determined to sleep at Sodus that night, and following these primitive and pretty sounding directions, we kept on the Sodus road. The day wore on. We stopped under an elm just beyond a sharp-backed bridge made of pine logs and rails, to eat our lunch, the ponies meanwhile cropping the elm branches and the wild alfalfa. Ned drew them buckets of water from the branch brook that went whispering by over a bed of pebbles and mosses.

Then a farmhouse came into view. It was, of course made of pine logs, and on its old, loosely shingled roof grew patches of moss and lichen here and there, like an old pate going bald. A great many little log barns, a sort of toy colony of them, stood around in puddles, each one already bulging with fodder and sweet-scented hay.

As we halted a lady came to the open door and eyed us incuriously. Real country people betray no more emotional curiosity than Indians. This lady wore in the corner of her mouth a ruminative stick. Over the front of her dress was a little trail of fine brown powder, as if a boring worn or a small mole had been casting up a burrow; small settlements of the same lodged in the corners of her mouth. When she spoke she did so carefully, so as not to spill any of her saliva.

“Could I have some milk?” Oh, yes. But what was I going to do with it? “Drink it.” I said promptly. In a few moments she brought out a large white bowl nearly full. I managed to lift it to my mouth, for a good, thirsty drink. Bah! It was stalely sour, and Ned finished it for me.

Two hours later we saw an old lady looking out at us through a palisade of pine saplings. “Howdy!” I said cheerily. “Please,” said I, “How far is it to Sodus?”

“This ain’t no way to git to Sodus. You are dretlful close to Marthysville. Sodus is 16 miles off. Jest turn down the red hill, keep on till the schoolhouse, turn to your left, and ef you don’t go astray you are bound to fetch up at Sodus some time or ruther.”

It was almost dark when we fetched up at Sodus. In a drive of at least 38 miles — for we were lost several times — we had not passed a dozen houses. Truly it seemed an entire European country might be housed in this one big, peopleless parish of Sabine.

The daintiest of little country hotels, the wholesomest of country suppers, made me in love with this pretty little railway town. If anybody isn’t satisfied with the hotels at Sodus and Marthaville, to which we came later on, he is hard to please. It was at Sodus I fell in with a scholarly little gray English gentleman, Prof. Hoskyns, who has charge of the school. Prof. Hoskyns is an admirable learned and intellectual man, a thoroughbred gentleman, under whose care the school children showed progress in manners, as well as learning. At night, they say, he writes books up in his quiet room, a quiet gray little gentleman leading a quiet gray little life in the day, struggling patiently with the chubby lads and lassies who have more love for him than fear of him.

I think that I could conveniently skip the next 40 miles. We left Sodus early, and, keeping west, came at noon to Mr. John Parrott’s, whose young son, a graduate of Tulane Medical College, has already a heavy practice in Sabine. A country physician, by the way, gets a dollar mile, and perhaps is paid in land, cotton or live stock. Now and then we passed a country school, where the majority of the pupils were of the olive-skinned, dark-eyed, picturesque Spanish type that told me as plainly as my map did that we were rapidly traveling Texasward.

“It looks mighty stormy, lady,” warned an old man as we drove away from Parrott’s. At that time I wasn’t much afraid of a storm, because I didn’t know. We pushed on through the forest, and I sat idly adoring the lovely luminous blue sky, all sprayed with the delicate tracery of the pine needles telling myself it was the most beautiful thing eye could look upon. A pine forest has such a clean, cheerful, bare, deceptive look; you always feel as if the next turn in the road will bring you to a camp or house. It was a general tumbilification of little hills, with now and then a dank hollow, where a bronze and green moss, thick as plush for the queen, was woven over everything, and where all manner of fungi grew. Never was anything more charming. From the sides of the pines the pale ivory shelves jutted out in scalloped tiers; on the ground lay clusters like crumpled combs, splendid bulbs of satiny shining gold and saffron and salmon, inverted cones like teacups of brittle milk-white porcelain; airy, papery-like Japanese umbrellas, all fluted and dashed on their gray-white roofs with vivid scarlet, and most beautiful of all, a log of green moss fretted and frothed all over with a pink and pearl growth on which there was a velvety bloom, such as one sees on the petals of a tea rose. I opened my bag and took out a little picture — the little roseleaf [f]ace of her who is the cricket on my hearth. Surely it was the sweetest thing in all that grandly lonesome forest!

At that moment a mournful howl fairly went in a coil around the woods. Overhead the blue had contracted. It was now framed in with a sulphurous smoke gray, like a blue cup in a gray saucer. The howl coiled around us again. Soon, dried pine needles began to rain down from the trees, thicker and faster they fell, until off in the woods was one brown bevy of them. The war of the wind was now terrific. The treetops bent like bunches of green feathers. The blue was all gone. A blinding flash, a deafening explosion, and one of Ned’s “thunder-bolts” plowed into the ground on the crest of the not distant hill. The horses fairly squatted on their haunches like rabbits with fright. Here and there a dead tree fell. I watched ahead in an agony of fear to see if any stood near the road and when one did we fairly galloped past it. No storm at sea has wilder terrors than a storm in August in a piney wood forest. It was an hour before we came to a clearing in either the sky or the forest, and I drew my first long breath. Such a clearing, too, overhead the forget-me-not sky; all about rolling pasture lands knee-deep in a rich pale grass, where cows cropped; off in the distance the rambling roof and big wheels, all rust red, of a country saw and grist mill. A house stood nearer the road. I went in to rest. A woman sat up in bed with a day-old baby in her arms. “How many have you?” I asked presently. She halted. “I think about 10,” she said finally. “Who takes care of you now?” was my next question. “Oh, just my little girl. She’s 10 years old.” was the patient answer of this Madonna of the forest. Think of that, you tenderly cared-for mothers whose infants are not swaddled in rags and whose beds of pain are downy couches!.

It was near this house, on the return journey, I spent the night at Squire Darnel’s. The squire has lived in Sabine parish for 58 years. He knows every foot of it, and his quaint old home of pine logs and weather-boarding, set down behind bloomy banks of lady slipper, petunias and four o’clocks has passed into the maps of the state as Darnel’s Gin. Now, with blinded eyes this fine old gentleman sits on his vine-covered porch, his weather-beaten face like a fine Cellini bronze framed in with silver, the patriarch of the “west countree.” It was here a dear old lady, Mrs. Tuggles — delicious, Dickensy name! — sat knitting socks against the winter and reminding me of things I had written ten years ago, or quoting poetry; no nowadays verse, but Thomson’s “Seasons” and Pope, and even earlier song-birds. A neighbor or two dropped in from a distance of 3 or four miles or so , and I got all the homely gossip, interjected between lines of Virgil, in a thin, quavering voice, that when it faltered was gently prodded by the squire’s keener memory.

It was 6 o’clock and already sundown below the crowding hills when we came to the Sabine river. From a tree hung a rusty plow blade and an old hatchet. I struck sharply on this primitive gong. It rang out as beautifully as the voice of some deep-mouthed abbey bell, and presently a flatboat came creeping on its creaking ropes across the umber river. Opposite was the tiny village of Hamilton, Texas, the only place within 10 miles where I could stay all night.

I stood on the porch of Brittin’s store, and around me was a half-moon of puzzled, confused-looking men. “And so,” said I desperately, “you mean to tell me I can’t stay here all night; that I must either sleep in my buggy or camp out on that flatboat?”

“You see,” answered one, clearing his throat as if trying to swallow a phlegm of embarrassment, “the truth is, we are all widowers in this town, and we don’t think it fitten’ and proper or doing right by you, ma’am.” I laughed outright, and I determined then and there to make known to the world the condition of this womanless town, this Eveless Eden.

The widowers withdrew to a corner of the store for a consultation. They, however, politely detailed one of their number to entertain me in conversation while they conferred with each other. Presently one of them went out the back door. He was gone a few minutes and came back with a beaming countenance. They all surrounded me again. “Ma’am,” said the spokesman, “deferring to your comfort we have decided you shall go to Wigginses. It’s a mile and a half further on; but Mr. Wiggins has a mighty good wife and a mighty nice farm, and you will be well cared for.”

Need I tell how glad I was to reach Wigginses, to strike a house that had a good wife in it, to hear a cheerful voice inviting me to “’light” to hear the last funeral squawk of a fat chicken, to smell coffee boiling in the big log kitchen; to eat hot pumpkin bread and yellow butter, and afterwards to rest for a while on the porch, in a chair of deer thongs?

I think during my forest drive I had accumulated at least a million little wood ticks that unanimously decided that my God should be their God, and that where I lodged, there they would lodge also. But when I blew out my flaring tin lamp, and climbed into that huge feather bed at Wiggin’s , with the windows set wide to give entrance to the sweet, dewy silence of the Texas night, chorded with the melancholy hoot of owl, the far off baying of a deer hound, and the sleepy note of a wood dove, I do not think all the ticks from all the forests could have kept me out of the lotus land of sleep.

Catherine Cole

Notes

- Drummer. A traveling sales person. So called because they “drummed up” business as they travelled.

- Pour boire. A tip. Lit., “for drinking,” French.

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Cole, Catharine. “In the West Countree.” Times Picayune [New Orleans] 25 Apr. 1983: 3. Print.