Anthology

of Louisiana Literature

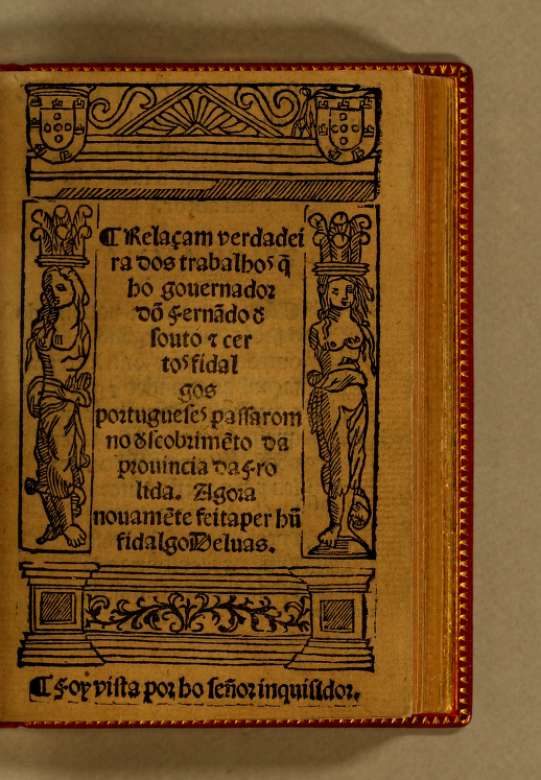

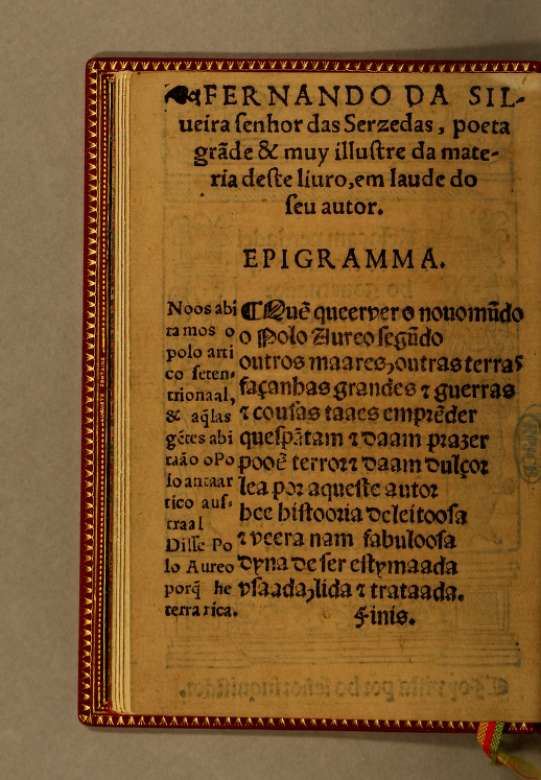

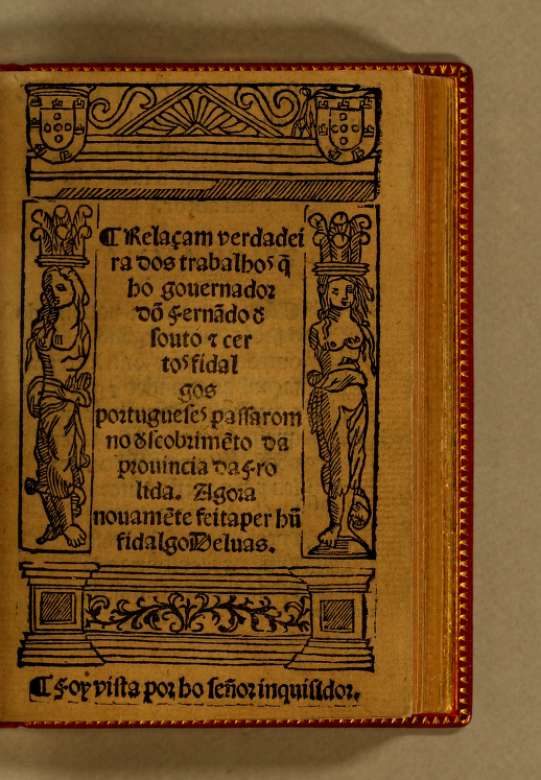

Fidalgo D'Elvas.

Richard Hackluyt, trans.

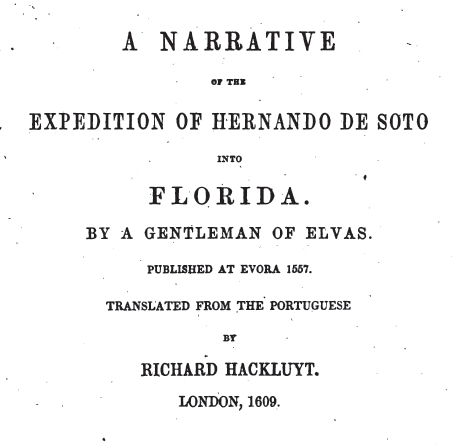

A Narrative of the

Expedition of Hernando de Soto into

Florida, by a Gentleman of Elvas, translated from the

Portuguese by Richard Hackluyt, in 1609.

Captain Soto was the son of a squire of Xerez of Badajoz. He went

into the Spanish Indies, when Peter Arias of Avila was Governor of the

West Indies. And there he was without anything else of his own, save his

sword and target: and for his good qualities and valor, Peter Arias made

him captain of a troop of horsemen, and by his commandment he went with

Fernando Pizarro to the conquest of Peru: where (as many persons of

credit reported, which were there present) as well at the taking of

Atabalipa, Lord of Peru, as at the assault of the city of Cusco, and in

all other places where they found resistance, wheresoever he was present,

he passed all other captains and principal persons. For which cause,

besides his part of the treasure of Atabalipa, he had a good share;

whereby in time he gathered a hundred and four score thousand ducats

together, with that which fell to his part; which he brought into Spain;

whereof the Emperor borrowed a certain part, which he repaid again with

60,000 rials of plate in the rent of the silks of Granada, and all the

rest was delivered him in the contractation house of Seville. He took

servants to wit, a steward, a gentleman usher, pages, a gentleman of the

horse, a chamberlain, lackeys, and all other officers that the house of a

noble may require. From Seville he went to the court, and in the

court, there accompanied him John Danusco of Seville, and Lewis Moscoso

D'Alvarado, Nuño de Touar, and John Rodriquez Lobillo.

Except John Danusco, all the rest came with him from Peru: and every one

of them brought fourteen or fifteen thousand ducats: all of them went well

and costly appareled. And although Soto of his own nature was not

liberal, yet because that was the first time that he was to show himself

in the court, he spent frankly, and went accompanied with those which I

have named, and with his servants, and many others which resorted unto

him. He married with Donna Isabella de Bobadilla, daughter of Peter Arias

of Avila, Earl of Punno en Rostro. The Emperor made him the Governor of

the Isle of Cuba, and Adelantado or President of Florida; with a title of

Marquis of certain part of the lands that he should conquer.

When Don Ferdinando had obtained the government, there came a

gentleman from the Indies to the court, named Cabeça de Vaca, which had

been with the Governor Pamphilo de Narvaez which died in Florida, who

reported that Narvaez was cast away at sea with all the company that went

with him. And how he with four more escaped and arrived in Nueva España.

Also he brought a relation in writing, of that which he had seen in

Florida; which said in some places: In such a place I have seen this; and

the rest which here I saw, I leave to confer of between his Majesty and

myself. Generally he reported the misery of the country, and the troubles

which he passed: and he told some of his kinsfolk, which were desirous to

go into the Indies, and urged him very much to tell them whether he had

seen any rich country in Florida, that he might not tell them, because he

and another, whose name was Orantes, (who remained in Nueva España with

purpose to return into Florida: for which intent he came into Spain to beg

the government thereof of the Emperor) had sworn not to discover some of

those things which they had seen, because no man should prevent them in

begging the same. And he informed them that it was the richest country of

the world. Don Ferdinando de Soto was very desirous to have him with him,

and made him a favorable offer: and after they were agreed, because Soto

gave him not a sum of money which he demanded to buy a ship, they broke

off again. Baltasar de Gallegos, and Christopher de Spindola, the kinsmen

of Cabeça de Vaca, told him, that for that which he had imparted to them,

they were resolved to pass with Soto into Florida, and therefore they

prayed him to advise them what they were best to do. Cabeça de Vaca told

them, that the cause why he went not with Soto, was because he hoped to

beg another government, and that he was loth to go under the command of

another: and that he came to beg the conquest

of Florida: but seeing Don Ferdinando de Soto had gotten it already, for

his oath's sake he might tell them nothing of that which they would know:

but he counseled them to sell their goods and go with him, and that in so

doing they should do well. As soon as he had opportunity, he spake with

the Emperor, and related unto him whatsoever he had passed and seen, and

come to understand. Of this relation, made by word of mouth to the

Emperor, the Marquis of Astorga had notice, and forthwith determined to

send with Don Ferdinando de Soto his brother Don Antonio Osorio: and with

him two kinsmen of his prepared themselves, to wit, Francis Osorio, and

Garcia Osorio. Don Antonio dispossessed himself of 60,000 rials of rent

which he held by the church; and Francis Osorio of a town of vassals,

which he had in the country de Campos. And they made their rendezvous

with the Adelantado in Seville. The like did Nuñez de Touar, and Lewis de

Moscoso, and John Rodriguez Lobillo, each of whom had brought from Peru

fourteen or fifteen thousand ducats. Lewis de Moscoso carried with him

two brethren; there went also Don Carlos, which had married the governor's

niece, and took her with him. From Badajoz there went Peter Calderan, and

three kinsmen of the Adelantado, to wit, Arias Tinoco, Alfonso Romo, and

Diego Tinoco. And as Lewis de Moscoso passed through

Elvas

Andrew de

Vasconcelos spake with him, and requested him to speak to Don Ferdinando

de Soto concerning him, and delivered him certain warrants which he had

received from the Marquis of Villa Real, wherein he gave him the

captainship of Ceuta in Barbarie, that he might show them unto him. And

the Adelantado saw them; and was informed who he was, and wrote unto him,

that he would favor him in all things, and by all means, and would give

him a charge of men in Florida. And from Elvas went Andrew de

Vasconcelos, and Fernan Pegado, Antonio Martinez Sequrado, Men Roiz

Pereira, John Cordero, Stephen Pegado, Benedict Fernandez, and Alvaro

Fernandez. And out of Salamanca, and Jaen, and Valencia, and Albuquerque,

and from other parts of Spain, many people of noble birth, assembled at

Seville, insomuch that in Saint Lucar many men of good account, which had

sold their goods, remained behind for want of shipping, whereas for other

known and rich countries, they are wont to want men: and this fell out by

occasion of that which

Cabeça de Vaca

told the Emperor, and informed such

persons as he had conference

withal touching the state of that Country. Soto made him great offers,

and being agreed to go with him (as I have said before) because he would

not give him money to pay for a ship, which he had bought, they brake off,

and he went for governor to the river of Plate. His kinsmen,

Christopher de Spindola and Baltasar de Gallegos, went with Soto. Baltasar de

Gallegos sold houses and vineyards, and rent corn, and ninety ranks of

olive trees in the Xarafe of Seville. He had the office of Alcalde Mayor,

and took his wife with him. And there went also many other persons of

account with the President, and had the offices following by great

friendship, because they were offices desired of many, to wit, Antonie de

Biedma was factor, John Danusco was auditor, and John Gayton, nephew to

the Cardinal of Ciguenza, had the office of treasurer.

The Portuguese departed from Elvas the 15th of January, and came to

Seville the 19th of the same month, and went to the lodging of the

Governor, and entered into a court, over the which were certain galleries

where he was, who came down and received them at the stairs, whereby they

went up into the galleries. When he was come up, he commanded chairs to

be given them to sit on. And Andrew de Vasconcelos told him who he and

the other Portuguese were, and how they all were come to accompany him,

and serve him in his voyage. He gave him thanks, and made show of great

contentment for his coming and offer. And the table being already laid,

he invited them to dinner. And being at dinner, he commanded his steward

to seek a lodging for them near unto his own, where they might be lodged.

The Adelantado departed from Seville to Saint Lucar with all the people

which were to go with him. And he commanded a muster to be made, at the

which the Portuguese showed themselves armed in very bright armor, and the

Castellans very gallant with silk upon silk, with many pinkings and cuts.

The Governor, because these braveries in such an action did not like him,

commanded that they should muster another day, and every one should come

forth with his armor; at the which the Portuguese came as at the first

armed with very good armor. The Governor placed them in order near unto

the standard, which the ensign bearer carried. The Castellans, for the

most part, did wear very bad and rusty shirts of mail, and all of them

head- pieces and steel caps, and very bad lances. Some of them sought to

come among the Portuguese. So those passed and were counted and enrolled

which Soto liked and accepted of, and did accompany him into Florida;

which were in all six hundred men. He had already bought seven ships, and

had all necessary provision

aboard them. He appointed captains, and delivered to every one his ship,

and gave them in a roll what people every one should carry with them.

In the year of our Lord 1538, in the month of April, the Adelantado

delivered his ships to the captains which were to go in them; and took for

himself a new ship, and good of sail, and gave another to Andrew de

Vasconcelos, in which the Portuguese went; he went over the bar of St.

Lucar on Sunday, being St. Lazarus on Sunday, in the morning of the month

and year aforesaid, with great joy, commanding his trumpets to be sounded,

and many shots of the ordnance to be discharged. He sailed four days with

a prosperous wind, and suddenly it calmed; the calms continued eight days

with swelling seas, in such wise that we made no way. The fifteenth day

after his departure from St. Lucar, he came to Gomera, one of the

Canaries, on Easter day in the morning. The Earl of that island was

appareled all in white, cloak, jerkin, hose, shoes and cap, so that he

seemed a Lord of the Gipsies. He received the Governor with much joy; he

was well lodged, and all the rest had their lodgings gratis, and got great

store of victuals for their money, as bread, wine, and flesh; and they

took what was needful for their ships, and the Sunday following, eight

days after their arrival, they departed from the Isle of Gomera. The Earl

gave to Donna Isabella, the Adelantado's wife, a bastard daughter that he

had, to be her waiting-maid. They arrived at the Antilles, in the Isle of

Cuba, at the port of the city of St. Jago, upon Whit-Sunday. As soon as

they came thither, a gentleman of the city sent to the sea-side a very

fair roan horse, and well furnished, for the Governor, and a mule for

Donna Isabella, and all the horsemen and footmen that were in the town

came to receive him at the seaside. The Governor was well lodged,

visited, and served of all the inhabitants of the city, and all his

company had their lodgings freely: those which desired to go into the

country, were divided by four and four, and six and six, in the farms or

granges, according to the ability of the owners of the farms, and were

furnished by them with all things necessary.

The city of St. Jago hath fourscore houses, which are great and well

contrived. The most part have their walls made of boards, and are covered

with thatch; it hath some houses built with lime and stones, and covered

with tiles. It hath great orchards and many trees in them, differing from

those of Spain: there be fig trees which bear figs as big as one's fist,

yellow within, and of small taste; and other trees which bear a fruit

which they call Ananes, in making and bigness like to a small pineapple:

it is a fruit very sweet in taste: the shell being taken

away, the kernel is like a piece of fresh cheese. In the granges abroad

in the country there are other great pineapples, which grow on low trees,

and are like the Aloe tree: they are of a very good smell and exceeding

good taste. Other trees do bear a fruit which they call Mameis, of the

bigness of peaches. This the islanders do hold for the best fruit of the

country. There is another fruit which they call Guayabas, like filberts,

as big as figs. There are other trees as high as a javelin, having one

only stock without any bough, and the leaves as long as a casting dart;

and the fruit is of the bigness and fashion of a cucumber; one bunch

beareth twenty or thirty, and as they ripen the tree bendeth downward with

them: they are called in this country Plantanos, and are of a good taste,

and ripen after they be gathered; but those are the better which ripen

upon the tree itself; they bear fruit but once, and the tree being cut

down, there spring up others out of the but, which bear fruit the next

year. There is another fruit, whereby many people are sustained, and

chiefly the slaves, which are called Batatas. These grow now in the Isle

of Terçera, belonging to the kingdom of Portugal, and they grow within the

earth, and are like a fruit called Iname; they have almost the taste of a

chestnut. The bread of this country is also made of roots which are like

the

Batatas.

And the stock whereon those roots do grow is like an elder

tree: they make their ground in little hillocks, and in each of them they

thrust four or five stakes; and they gather the roots a year and a half

after they set them. If any one, thinking it is a batata or potato root,

chance to eat of it never so little, he is in great danger of death: which

was seen by experience in a soldier, which as soon as he had eaten a very

little of one of those roots, he died quickly. They pare these roots and

Stamp them, and squeeze them in a thing like a press: the juice that

cometh from them is of an evil smell. The bread is of little taste and

less substance. Of the fruits of Spain, there are figs and oranges, and

they bear fruit all the year, because the soil is very rank and fruitful.

In this country are many good horses, and there is green grass all the

year. There be many wild oxen and hogs, whereby the people of the island

are well furnished with flesh. Without the towns abroad in the Country are

many fruits. And it happeneth sometimes that a Christian goeth out of the

way and is lost fifteen or twenty days, because of the many paths in the

thick groves that cross to and fro made by the oxen; and being thus lost

they sustain themselves with fruits and palmîtos — for there be many

great groves of palm trees through all the island — they yield no other

fruit that is of any profit. The Isle of Cuba is three hundred leagues

long from the east to the west, and is in some places thirty, in others

forty leagues from north to south. It hath six towns of Christians, to

wit, St. Jago, Baracôa, Bayamo, Puerto de Principes,

S. Espirito, Havana.

Every one hath between thirty and forty households, except St. Jago and

Havana, which have about sixty or eighty houses. They have churches in

each of them, and a chaplain which confesseth them and saith mass. In St.

Jago is a monastery of Franciscan friars; it hath but few friars, and is

well provided of alms, because the country is rich. The Church of St.

Jago hath honest revenue, and there is a curate and prebends, and many

priests, as the church of that city, which is the chief of all the island.

There is in this country much gold and few slaves to get it; for many have

made away themselves, because of the Christians' evil usage of them in the

mines. A steward of Casquez Porcallo, which was an inhabitor in that

island, understanding that his slaves would make away themselves, stayed

for them with a cudgel in his hand at the place where they were to meet,

and told them that they could neither do nor think anything that he did

not know before, and that he came thither to kill himself, with them, to

the end, that if he had used them badly in this world, he might use them

worse in the world to come: and this was a means that they changed their

purpose, and turned home again to do that which he commanded them.

The Governor sent from St. Jago his nephew Don Carlos, with the ships

in company of Donna Isabella to tarry for him at Havana, which is a haven

in the west part toward the head of the island, one hundred and eighty

leagues from the city of St. Jago. The Governor, and those which stayed

with him, bought horses and proceeded on their journey. The first town

they came unto was Bayamo: they were lodged four and four, and six and

six, as they went in company, and where they lodged, they took nothing for

their diet, for nothing cost them aught save the maize or corn for their

horses, because the Governor went to visit them from town to town, and

seized them in the tribute and service of the Indians. Bayamo is

twenty-five leagues from the city of St. Jago. Near unto the town passeth

a great river which is called Tanto; it is greater than Guadiana, and in

it be very great crocodiles, which sometimes hurt the Indians, or the

cattle which passeth the river. In all the country are neither wolf, fox,

bear, lion, nor tiger. There are wild dogs which go from the houses into

the woods and feed upon swine. There be certain

snakes as big as a man's thigh or bigger; they are very slow, they do no

kind of hurt. From Bayamo to Puerto de los Principes are fifty leagues.

In all the island from town to town, the way is made by stubbing up the

underwood; and if it be left but one year undone, the wood groweth so much

that the way cannot be seen, and the paths of the oxen are so many, that

none can travel without an Indian of the country for a guide: for all the

rest is very high and thick woods. From Puerto de los Principes the

Governor went to the house of Vasquez Porcallo by sea in a boat (for it

was near the sea) to know there some news of Donna Isabella, which at that

instant (as afterwards was known) was in great distress, insomuch that the

ships lost one another, and two of them fell on the coast of Florida, and

all of them endured great want of water and victuals. When the storm was

over, they met together without knowing where they were: in the end they

descried the Cape of St. Anton, a country not inhabited of the island of

Cuba; there they watered, and at the end of forty days, which were passed

since their departure from the city of St. Jago, they arrived at Havana.

The Governor was presently informed thereof, and went to Donna Isabella.

And those which went by land, which were one hundred and fifty horsemen,

being divided into two parts, because they would not oppress the

inhabitants, traveled by St. Espirito, which is sixty leagues from Puerto

de los Principes. The food which they carried with them was Caçabe bread,

which is that whereof I made mention before: and it is of such a quality

that if it be wet it breaketh presently, whereby it happened to some to

eat flesh without bread for many days. They carried dogs with them, and a

man of the country, which did hunt; and by the way, or where they were to

lodge that night, they killed as many hogs as they needed. In this

journey they were well provided of beef and pork, and they were greatly

troubled with musquitoes, especially in a lake, which is called the mere

of Pia, which they had much ado to pass from noon till night. The water

might be some half league over, and to be swam about a crossbow shot; the

rest came to the waist, and they waded up to the knees in the mire, and in

the bottom were cockle shells, which cut their feet very sore, in such

sort that there was neither boot nor shoe sole that was whole at half way.

Their clothes and saddles were passed in baskets of palm trees. Passing

this lake, stripped out of their clothes, there came many mosquitoes, upon

whose biting there arose a wheal that smarted very much; they struck them

with their hands, and with the blow which they gave they killed so many

that the blood did run down the arms and bodies of the men. That

night they rested very little for them, and other nights also in the like

places and times. They came to Santo Espirito, which is a town of thirty

houses; there passeth by it a little river; it is very pleasant and

fruitful, having great store of oranges and citrons, and fruits of the

Country. One-half of the company were lodged here, and the rest passed

forward twenty-five leagues to another town called la Trinidad, of fifteen

or twenty households. Here is an hospital for the poor, and there is none

other in all the island. And they say that this town was the greatest in

all the country, and that before the Christians came into this land, as a

ship passed along the coast there came in it a very sick man, which

desired the captain to set him on shore, and the captain did so, and the

ship went her way. The sick man remained set on shore in that country,

which until then had not been haunted by Christians; whereupon the Indians

found him, carried him home, and looked unto him till he was whole; and

the lord of that town married him unto a daughter of his, and had war with

all the inhabitants round about, and by the industry and valor of the

Christian, he subdued and brought under his command all the people of that

island. A great while after, the Governor Diego Velasques went to conquer

it, and from thence discovered New Spain. And this Christian which was

with the Indians did pacify them, and brought them to the obedience and

subjection of the governor. From this town de la Trinidad unto Havana are

eighty leagues, without any habitation, which they traveled. They came to

Havana in the end of March, where they found the Governor, and the rest of

the people which came with him from Spain. The Governor sent from Havana

John Dannusco with a caravele and two brigantines with fifty men to

discover the haven of Florida, and from thence he brought two Indians

which he took upon the coast, wherewith (as well because they might be

necessary for guides and for interpreters, as because they said by signs

that there was much gold in Florida) the Governor and all the company

received much contentment, and longed for the hour of their departure,

thinking in himself that this was the richest country that unto that day

had been discovered.

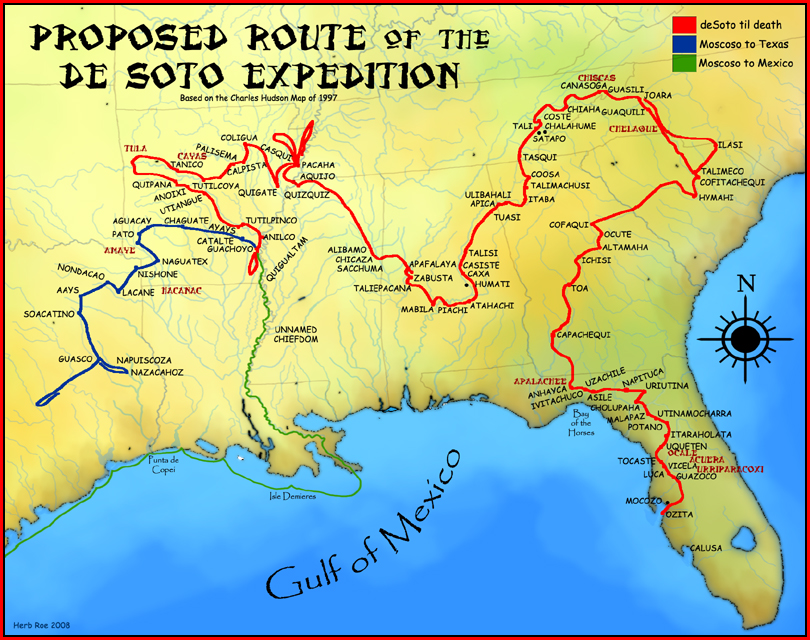

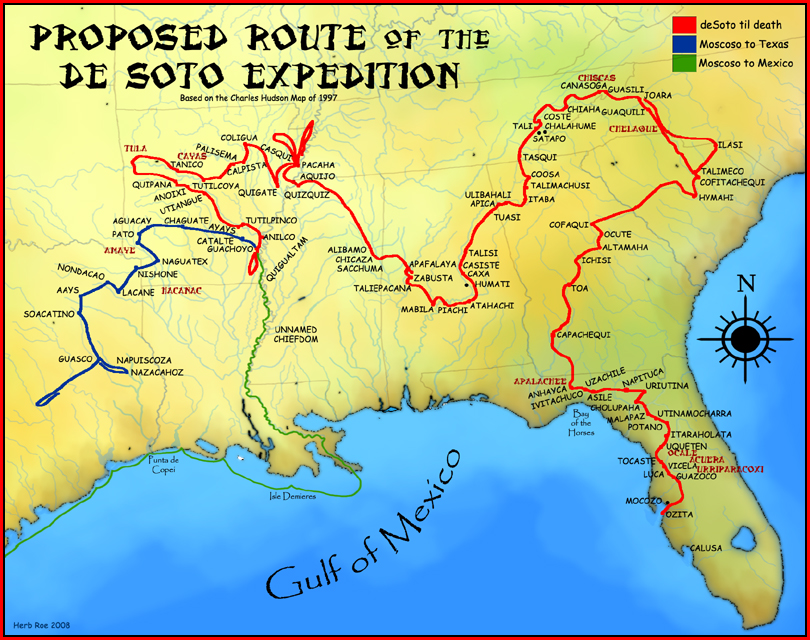

Heironymous Rowe. Proposed Route of the de Soto Expedition.

Before our departure the Governor deprived Nuño de Touar of the

office of Captain-general, and gave it to Porcallo de Figueroa, an

inhabitant of Cuba, which was a mean that the ship was well furnished with

victuals; for he gave a great many loads of Casabe bread and many hogs.

The Governor took away this office from Nuño de Touar, because he had

fallen in love with the daughter of the

Earl of Gomera, Donna Isabella's waiting- maid, who, though his office

were taken from him (to return again to the Governor's favor), though she

were with child by him, yet took her to his wife, and went with Soto into

Florida. The Governor left Donna Isabella in Havana, and with her

remained the wife of Don Carlos, and the wives of Baltasar de Gallegos,

and of Nuño de Touar. And he left for his lieutenant a gentleman of

Havana, called John de Poias, for the government of the island.

On Sunday the 18th of May, in the year of our Lord 1539, the

Adelantado or president departed from Havana in Cuba with his fleet, which

were nine vessels, five great ships, two caravels, and two brigantines.

They sailed seven days with a prosperous wind. The 25th day of May, the

day de

Pasca de Spirito Santo

(which we call Whitson Sunday), they saw

the land of Florida, and because of the shoals, they came to an anchor a

league from the shore. On Friday the 30th of May they landed in Florida,

two leagues from a town of an Indian lord called Ucita. They set on land

two hundred and thirteen horses, which they brought with them to unburden

the ships, that they might draw the less water. He landed all his men,

and only the seamen remained in the ships, which in eight days, going up

with the tide every day a little, brought them up unto the town. As soon

as the people were come on shore, he pitched his camp on the sea-side,

hard upon the bay which went up unto the town. And presently the

Captain-general, Vasquez Porcallo, with other seven horsemen foraged the

country half a league round about, and found six Indians, which resisted

him with their arrows, which are the weapons which they used to fight

withal. The horsemen killed two of them, and the other four escaped;

because the country is cumbersome with woods and hogs, where the horses

stuck fast, and fell with their riders, because they were weak with

traveling upon the sea. The same night following, the Governor with an

hundred men in the brigantines lighted upon a town, which he found without

people, because that as soon as the Christians had sight of land, they

were descried, and saw along the coast many smokes, which the Indians had

made to give advice the one to the other. The next day Luys de Moscoso,

master of the camp, set the men in order, the horsemen in three squadrons,

the vanguard, the battalion, and the rereward; and so they marched that

day and the day following, compassing great creeks which came out of the

bay. They came to the town of Ucita,

where the Governor was on Sunday the first of June, being Trinity Sunday.

The town was of seven or eight houses. The lord's house stood near the

shore upon a very high mount, made by hand for strength. At another end

of the town stood the church, and on the top of it stood a fowl made of

wood with gilded eyes. Here were found some pearls of small value,

spoiled with the fire, which the Indians do pierce and string them like

beads, and wear them about their necks and handwrists, and they esteem

them very much. The houses were made of timber, and covered with palm

leaves. The Governor lodged himself in the lord's houses, and with him

Vasquez Porcallo, and Luys de Moscoso; and in others that were in the

midst of the town, was the chief Alcalde or justice, Baltasar de Gallegos

lodged; and in the same houses was set in a place by itself all the

provision that came in the ships; the other houses and the church were

broken down, and every three or four soldiers made a little cabin wherein

they lodged. The Country round about was very fenny, and encumbered with

great and high trees. The Governor commanded to fell the woods a crossbow

shot round about the town, that the horses might run, and the Christians

might have the advantage of the Indians, if by chance they should set upon

them by night. In the ways and places convenient they had their sentinels

of footmen by two and two in every stand, which did watch by turns, and

the horsemen did visit them, and were ready to assist them if there were

any alarm. The Governor made four captains of the horsemen and two of the

footmen. The captains of the horsemen were one of them Andrew de

Masconcelos, and another Pedro Calderan de Badajoz; and the other two were

his kinsmen, to wit, Arias Timoco, and Alfonso Romo, born likewise in

Badajoz. The captains of the footmen, the one was Francisco Maldonado of

Salamanca, and the other Juan Rodriquez Lobillo. While we were in this

town of Ucita, the two Indians which John Danusco had taken on that coast,

and the Governor carried along with him for guides and interpreters,

through carelessness of two men which had the charge of them escaped away

one night; for which the Governor and all the rest were very sorry, for

they had already made some roads, and no Indians could be taken, because

the country was full of marsh grounds, and in some places full of very

high and thick woods.

From the town of Ucita the Governor sent the Alcalde Mayor, Baltasao

de Gallegos, with forty horsemen and eighty footmen into the country to

see if they could take any Indians; and the Captain John Rodriquez Lobillo

another way with fifty footmen: the most of

them were swordsmen and targeters, and the rest were shot and crossbowmen.

They passed through a country full of hogs, where horses could not travel.

Half a league from the camp they lighted upon certain cabins of Indians

near a river. The people that were in them leaped into the river, yet they

took four Indian women. And twenty Indians charged us and so distressed

us, that we were forced to retire to our camp, being, as they are,

exceeding ready with their weapons. It is a people so warlike and so

nimble, that they care not a whit for any footmen. For if their enemies

charge them they run away, and if they turn their backs they are presently

upon them. And the thing that they most flee is the shot of an arrow.

They never stand still, but are always running and traversing from one

place to another, by reason whereof neither crossbow nor arquebuss can aim

at them; and before one crossbowman can make one shot an Indian will

discharge three or four arrows, and he seldom misseth what he shooteth at.

An arrow where it findeth no armor, pierceth as deeply as a crossbow.

Their bows are very long, and their arrows are made of certain canes like

reeds, very heavy, and so strong that a sharp cane passeth through a

target. Some they arm in the point with a sharp bone of a fish like a

chisel, and in others they fasten certain stones like points of diamonds.

For the most part when they light upon an armor they break in the place

where they are bound together. Those of cane do split and pierce a coat

of mail, and are more hurtful than the other. John Rodriquez Lobillo

returned to the camp with six men wounded, whereof one died; and brought

the four Indian women which Baltasar Gallegos had taken in the cabins or

cottages. Two leagues from the town, coming into the plain field, he

espied ten or eleven Indians, among whom was a Christian, which was naked

and scorched with the sun, and had his arms razed after the manner of the

Indians, and differed nothing at all from them. And as soon as the

horsemen saw them they ran toward them. The Indians fled, and some of them

hid themselves in a wood, and they overtook two or three of them which

were wounded; and the Christian seeing a horseman run upon him with his

lance, began to cry out, "Sirs, I am a Christian, slay me not, nor these

Indians, for they have saved my life." And straight-way he called them and

put them out of fear, and they came forth of the wood unto them. The

horsemen took both the Christian and the Indians up behind them, and

toward night came into the camp with much joy; which thing being known by

the Governor, and them that remained in the camp, they were received with

the like.

This Christian's name was John Ortiz, and he was born in Seville,

of worshipful parentage. He was twelve years in the hands of the Indians.

He came into this country with Pamphilo de Narvaez, and returned in the

ships to the Island of Cuba, where the wife of the Governor Pamphilo de

Narvaez was, and by his commandment with twenty or thirty others in a

brigantine returned back again to Florida, and coming to the port in the

sight of the town, on the shore they saw a cane sticking in the ground,

and riven at the top, and a letter in it; and they believed that the

governor had left it there to give advertisement of himself when he

resolved to go up into the land, and they demanded it of four or five

Indians which walked along the sea-shore, and they bade them by signs to

come on shore for it, which against the will of the rest John Ortiz and

another did. And as soon as they were on land, from the houses of the

town issued a great number of Indians, which compassed them about and took

them in a place where they could not flee; and the other, which sought to

defend himself, they presently killed upon the place, and took John Ortiz

alive, and carried him to Ucita their lord. And those of the brigantine

sought not to land, but put themselves to sea, and returned to the Island

of Cuba. Ucita commanded to bind John Ortiz hand and foot upon four

stakes aloft upon a raft, and to make a fire under him, that there he

might be burned. But a daughter of his desired him that he would not put

him to death, alleging that one only Christian could do him neither hurt

nor good, telling him that it was more for his honor to keep him as a

captive. And Ucita granted her request, and commanded him to be cured of

his wounds; and as soon as he was whole he gave him the charge of the

keeping of the temple, because that by night the wolves did carry away the

dead corpses out of the same — who commended himself to God and took upon

him the charge of his temple. One night the wolves got from him the

corpse of a little child, the son of a principal Indian, and going after

them he threw a dart at one of the wolves, and struck that carried away

the corpse, who, feeling himself wounded left it, and fell down dead near

the place; and he not woting what he had done, because it was night, went

back again to the temple; the morning being come and finding not the body

of the child, he was very sad. As soon as Ucita knew thereof he resolved

to put him to death, and sent by the track which he said the wolves went,

and found the body of the child, and the wolf dead a little beyond,

whereat Ucita was much contented with the Christian, and with the watch

which he kept in the temple, and from thenceforward esteemed him much.

Three years after he fell into his hands there came another lord called

Mocoço, who dwelleth two days' journey from the port, and burnt his town.

Ucita fled to another town that he had in another sea-port. Thus John

Ortiz lost his office and favor that he had with him. These people being

worshipers of the devil, are wont to offer up unto him the lives and blood

of their Indians, or of any other people they can come by; and they report

that when he will have them do that sacrifice unto him, he speaketh with

them, and telleth them that he is athirst, and willeth them to sacrifice

unto him. John Ortiz had notice by the damsel that had delivered him from

the fire, how her father was determined to sacrifice him the day

following, who willed him to flee to Mocoço, for she knew that he would

use him well; for she heard say that he had asked for him and said he

would be glad to see him, and because he knew not the way she went with

him half a league out of the town by night and set him in the way, and

returned because she would not be discovered. John Ortiz traveled all

that night, and by the morning came to a river which is the territory of

Mocoço, and there he saw two Indians fishing; and because they were in war

with the people of Ucita, and their languages were different, and he knew

not the language of Mocoço, he was afraid, because he could not tell them

who he was, nor how he came thither, nor was able to answer anything for

himself, that they would kill him, taking him for one of the Indians of

Ucita, and before they espied him he came to the place where they had laid

their weapons; and as soon as they saw him they fled toward the town, and

although he willed them to stay, because he meant to do them no hurt, yet

they understood him not, and ran away as fast as ever they could. And as

soon as they came to the town with great outcries, many Indians came forth

against him, and began to compass him to shoot at him. John Ortiz seeing

himself in so great danger, shielded himself with certain trees, and began

to shriek out and cry very loud, and to tell them that he was a Christian,

and that he was fled from Ucita, and was come to see and serve Mocoço his

lord. It pleased God that at that very instant there came thither an

Indian that could speak the language and understood him, and pacified the

rest, who told them what he said. Then ran from thence three or four

Indians to bear the news to their lord, who came forth a quarter of a

league from the town to receive him, and was very glad of him. He caused

him presently to swear according to the custom of the Christians, that he

would not run away from him to any other lord, and promised him to entreat

him very well; and that if at any time there came any Christians into that

country, he would freely let him go, and give him leave to go to

them; and likewise took his oath to perform the same according to the

Indian custom. About three years after certain Indians, which were

fishing at sea two leagues from the town, brought news to Mocoço that they

had seen ships, and he called John Ortiz and gave him leave to go his way,

who taking his leave of him, with all the haste he could came to the sea,

and finding no ships he thought it to be some deceit, and that the

cacique

had done the same to learn his mind. So he dwelt with Mocoço nine years,

with small hope of seeing any Christians. As soon as our Governor arrived

in Florida, it was known to Mocoço, and straightway he signified to John

Ortiz that Christians were lodged in the town of Ucita; and he thought he

had jested with him as he had done before, and told him that by this time

he had forgotten the Christians, and thought of nothing else but to serve

him. But he assured him that it was so, and gave him license to go unto

them, saying unto him that if he would not do it, and if the Christians

should go their way, he should not blame him, for he had fulfilled that

which he had promised him. The joy of John Ortiz was so great, that he

could not believe that it was true; notwithstanding he gave him thanks,

and took his leave of him, and Mocoço gave him ten or eleven principal

Indians to bear him company; and as they went to the port where the

Governor was, they met with Baltasar de Gallegos, as I have declared

before. As soon as he was come to the camp, the Governor commanded to

give him a suit of apparel, and very good armor, and a fair horse; and

inquired of him whether he had notice of any country where there was any

gold or silver. He answered, No, because he never went ten leagues

compass from the place where he dwelt; but that

thirty leagues from thence

dwelt an Indian lord, which was called Paracossi, to whom Mocoço

and Ucita, with all the rest of that coast paid tribute, and that he

peradventure might have notice of some good country, and that his land was

better than that of the sea-coast, and more fruitful and plentiful of

maize. Whereof the Governor received great contentment, and said that he

desired no more than to find victuals, that he might go into the main

land, for the land of Florida was so large, that in one place or other

there could not choose but be some rich country.

The Cacique Mocoço came

to the port to visit the Governor, and made this speech following.

"Right high and mighty lord, I being lesser in mine own conceit for

to obey you, than any of those which you have under your command,

and greater in desire to do you greater services, do appear before your

lordship with so much confidence of receiving favor, as if in effect this

my good will were manifested unto you in works; not for the small service

I did unto you touching the Christian which I had in my power, in giving

him freely his liberty (for I was bound to do it to preserve mine honor,

and that which I had promised him), but because it is the part of great

men to use great magnificences. And I am persuaded that as in bodily

perfections, and commanding of good people, you do exceed all men in the

world, so likewise you do in the parts of the mind, in which you may boast

of the bounty of nature. The favor which I hope for of your lordship is,

that you would hold me for yours, and bethink yourself to command me

anything wherein I may do you service."

The Governor answered him, "That although in freeing and sending him

the Christian, he had preserved his honor and promise, yet he thanked him,

and held it in such esteem as it had no comparison; and that he would

always hold him as his brother, and would favor all things to the utmost

of his power." Then he commanded a shirt to be given him, and other

things, wherewith the cacique being very well contented, took his leave of

him, and departed to his own town.

From the Port de Spirito Santo where the Governor lay, he sent the

Alcalde Mayor Baltasar de Gallegos with fifty horsemen, and thirty or

forty footmen to the province of Paracossi, to view the disposition of the

country, and inform himself of the land farther inward, and to send him

word of such things as he found. Likewise he sent his ships back to the

Island of Cuba, that they might return within a certain time with

victuals. Basque Porcallo de Figueroa, which went with the Governor as

Captain-general, (whose principal intent was to send slaves from Florida

to the Island of Cuba, where he had his goods and mines,) having made some

inroads, and seeing no Indians were to be got, because of the great hogs

and woods that were in the country, considering the disposition of the

same, determined to return to Cuba. And though there was some difference

between and the Governor, whereupon they neither dealt nor conversed

together with good countenance, yet notwithstanding with loving words he

asked him leave and departed from him. Baltasar de Gallegos came to the

Paracossi. There came to him thirty Indians from the cacique, which was

absent from his town, and one of them made this speech:

"Paracossi, the lord of this province, whose vassals we are, sendeth

us unto your worship, to know what it is that you seek in this his

country, and wherein he may do you service."

Baltasar de Gallegos said unto him that he thanked them very much for

their offer, willing them to warn their lord to come to his town, and that

there they would talk and confirm their peace and friendship, which he

much desired. The Indians went their way and returned next day, and said

that their lord was ill at ease, and therefore could not come; but that

they came on his behalf to see what he demanded. He asked them if they

knew or had notice of any rich country where there was gold or silver.

They told him they did, and that towards the west there was a province

which was called Cale; and that others that inhabited other countries had

war with the people of that country, where the most part of the year was

summer, and that there was much gold; and that when those their enemies

came to make war with them of Cale, these inhabitants of Cale did wear

hats of gold, in manner of head-pieces. Baltasar de Gallegos seeing that

the cacique came not, thinking all that they said was feigned, with intent

that in the meantime they might set themselves in safety, fearing that if

he did let them go, they would return no more, commanded the thirty

Indians to be chained, and sent word to the Governor by eight horsemen

what had passed; whereof the Governor with all that were with him at the

Port de Spirito Santo received great comfort, supposing that that which

the Indians reported might be true. He left Captain Calderan at the port,

with thirty horsemen and seventy footmen, with provision for two years,

and himself with all the rest marched into the main land, and came to the

Paracossi, at whose town Baltasar de Gallegos was; and from thence with

all his men took the way to Cale. He passed by a little town called

Acela, and came to another called Tocaste; and from thence he went before

with thirty horsemen and fifty footmen towards Cale. And passing by a

town whence the people were fled, they saw Indians a little distance from

thence in a lake, to whom the interpreter spoke. They came unto them and

gave them an Indian for a guide; and he came to a river with a great

current, and upon a tree which was in the midst of it, was made a bridge,

whereon the men passed; the horses swam over by a hawser, that they were

pulled by from the other side; for one, which they drove in at the first

without it, was drowned. From thence the Governor sent two horsemen to his

people that were behind, to make haste after him; because the way grew

long, and their victuals short. He came to Cale, and found the town

without people. He took three Indians which were spies, and tarried

there for his people that came after, which were sore vexed with hunger

and evil ways, because the country was very barren of maize, low, and full

of water, bogs, and thick woods; and the victuals which they brought with

them from the Port de Spirito Santo, were spent. Wheresoever any town was

found, there were some beets, and he that came first gathered them, and

sodden with water and salt, did eat them without any other thing; and such

as could not get them, gathered the stalks of maize and eat them, which

because they were young had no maize in them. When they came to the river

which the Governor had passed, they found palmitos upon low palm trees

like those of Andalusia. There they met with the two horsemen which the

Governor sent unto them, and they brought news that in Cale there was

plenty of maize, at which news they all rejoiced. As soon as they came to

Cale, the Governor commanded them to gather all the maize that was ripe in

the field, which was sufficient for three months. At the gathering of it

the Indians killed three Christians, and one of them which were taken told

the Governor, that within seven days' journey there was a very great

province, and plentiful of maize, which was called Apalache. And

presently he departed from Cale with fifty horsemen, and sixty footmen.

He left the master of the camp, Luys de Moscoso, with all the rest of the

people there, with charge that he would not depart thence until he had

word from him. And because hitherto none had gotten any slaves, the bread

that every one was to eat he was fain himself to beat in a mortar made in

a piece of timber, with a pestle, and some of them did sift the flour

through their shirts of mail. They baked their bread upon certain

tileshares which they set over the fire, in such sort as heretofore I have

said they used to do in Cuba. It is so troublesome to grind their maize,

that there were many that would rather not eat it than grind it; and did

eat the maize parched and sodden.

The second day of August, 1539, the Governor departed from Cale; he

lodged in a little town called Ytara, and the next day in another called

Potano, and the third day at Utinama, and came to another town which they

named the town of Evil peace; because an Indian came in peace, saying,

that he was the cacique, and that he with his people would serve the

Governor, and that if he would set free twenty-eight persons, men and

women, which his men had taken the night before, he would command

provision to be brought him, and would give him a guide to instruct him in

his way. The Governor commanded them to be set at liberty, and to keep

him in safeguard. The next day in the morning there came many Indians, and

set

themselves round about the town near to a wood. The Indian wished them to

carry him near them, and that he would speak unto them, and assure them,

and that they would do whatsoever he commanded them. And when he saw

himself near unto them he broke from them, and ran away so swiftly from

the Christians that there was none that could overtake him, and all of

them fled into the woods. The Governor commanded to loose a greyhound,

which was already fleshed on them, which passing by many other Indians,

caught the counterfeit cacique which had escaped from the Christians, and

held him till they came to take him. From thence the Governor lodged at a

town called Cholupaha, and because it had store of maize in it, they named

it Villa farta. Beyond the same there was a river, on which he made a

bridge of timber, and traveled two days through a desert. The 17th of

August he came to Caliquen, where he was informed of the province of

Apalache. They told him that Pamphilo de Narvaez had been there, and that

there he took shipping, because he could find no way to go forward. That

there was none other town at all; but that on both sides was all water.

The whole company were very sad for this news, and counseled the Governor

to go back to the Port de Spirito Santo, and to abandon the country of

Florida, lest he should perish as Narvaez had done; declaring that if he

went forward, he could not return back when he would, and that the Indians

would gather up that small quantity of maize which was left. Whereunto

the Governor answered that he would not go back, till he had seen with his

eyes that which they reported; saying that he could not believe it, and

that we should be put out of doubt before it were long. And he sent to

Luys de Moscoso to come presently from Cale, and that he tarried for him

there. Luys de Moscoso and many others thought that from Apalache they

should return back; and in Cale they buried their iron tools, and divers

other things. They came to Caliquen with great trouble; because the

country which the Governor had passed by, was spoiled and destitute of

maize. After all the people were come together, he commanded a bridge to

be made over a river that passed near the town. He departed from Caliquen

the 10th of September, and carried the cacique with him. After he had

traveled three days, there came Indians peaceably to visit their lord, and

every day met us on the way playing upon flutes; which is a token that

they use, that men may know that they come in peace. They said that in

our way before there was a cacique whose name was Uzachil, a kinsman of

the cacique of Caliquen their lord, waiting for him with many presents,

and they

desired the Governor that he would loose the cacique. But he would not,

fearing that they would rise, and would not give him any guides, and sent

them away from day to day with good words He traveled five days; he passed

by some small towns; he came to a town called Napetuca, the 15th day of

September. Thither came fourteen or fifteen Indians, and besought the

Governor to let loose the cacique of Caliquen, their lord. He answered

them that he held him not in prison, but that he would have him to

accompany him to Uzachil. The Governor had notice by John Ortiz, that an

Indian told him how they determined to gather themselves together, and

come upon him, and give him battle, and take away the cacique from him.

The day that it was agreed upon, the Governor commanded his men to be in

readiness, and that the horsemen should be ready armed and on horse-back

every one in his lodging, because the Indians might not see them, and so

more confidently come to the town. There came four hundred Indians in

sight of the camp with their bows and arrows, and placed themselves in a

wood, and sent two Indians to bid the Governor to deliver them the

cacique. The Governor with six footmen leading the cacique by the hand,

and talking with him, to secure the Indians, went toward the place where

they were. And seeing a fit time, commanded to sound a trumpet; and

presently those that were in the town in the houses, both horse and foot,

set upon the Indians, which were so suddenly assaulted, that the greatest

care they had was which way they should flee. They killed two horses; one

was the Governor's, and he was presently horsed again upon another. There

were thirty or forty Indians slain. The rest fled to two very great

lakes, that were somewhat distant the one from the other. There they were

swimming, and the Christians round about them. The calivermen and

crossbowmen shot at them from the bank; but the distance being great, and

shooting afar off, they did them no hurt. The Governor commanded that the

same night they should compass one of the lakes, because they were so

great, that there were not men enough to compass them both; being beset,

as soon as night shut in, the Indians, with determination to run away,

came swimming very softly to the bank; and to hide themselves they put a

water lily leaf on their heads. The horsemen, as soon as they perceived

it to stir, ran into the water to the horses' breasts, and the Indians

fled again into the lake. So this night passed without any rest on both

sides. John Ortiz persuaded them that seeing they could not escape, they

should yield themselves to the Governor; which they did, enforced

thereunto by the coldness of the water; and one by one, he first whom the

cold did

first overcome, cried to John Ortiz, desiring that they would not kill

him, for he came to put himself into the hands of the Governor. By the

morning watch they made an end of yielding themselves; only twelve

principal men, being more honorable and valorous than the rest, resolved

rather to die than to come into his hands. And the Indians of Paracossi,

which were now loosed out of chains, went swimming to them, and pulled

them out by the hair of their heads, and they were all put in chains, and

the next day were divided among the Christians for their service. Being

thus in captivity, they determined to rebel; and gave in charge to an

Indian which was interpreter, and held to be valiant, that as soon as the

Governor did come to speak with him, he should cast his hands about his

neck, and choke him: who, when he saw opportunity, laid hands on the

Governor, and before he cast his hands about his neck, he gave him such a

blow on the nostrils, that he made them gush out with blood, and presently

all the rest did rise. He that could get any weapons at hand, or the

handle wherewith he did grind the maize, sought to kill his master, or the

first he met before him; and he that could get a lance or sword at hand,

bestirred himself in such sort with it, as though he had used it all his

lifetime. One Indian in the market-place enclosed between fifteen or

twenty footmen, made a way like a bull, with a sword in his hand, till

certain halbardiers of the Governor came, which killed him. Another got

up with a lance to a loft made of canes, which they build to keep their

maize in, which they call a barbacoa, and there he made such a noise as

though ten men had been there defending the door; they slew him with a

partizan. The Indians were in all about two hundred men. They were all

subdued. And some of the youngest the Governor gave to them which had good

chains, and were careful to look to them that they got not away. All the

rest he commanded to be put to death, being tied to a stake in the midst

of the market-place; and the Indians of the Paracossi did shoot them to

death.

The Governor departed from Napetuca the 23d of September; he lodged

by a river, where two Indians brought him a buck from the cacique of

Uzachil. The next day he passed by a great town called Hapaluya, and

lodged at Uzachil, and found no people in it, because they durst not tarry

for the notice the Indians had of the slaughter of Napetuca. He found in

that town great store of maize, French beans, and pompions, which is their

food, and that wherewith the Christians there sustained themselves. The

maize is like coarse millet, and the pompions are better and more savory

than those of

Spain. From thence the Governor sent two captains each a sundry way to

seek the Indians. They took an hundred men and women; of which as well

there as in other place where they made any inroads, the captain chose one

or two for the Governor, and divided the rest to himself, and those that

went with him. They led these Indians in chains with iron collars about

their necks; and they served to carry their stuff, and to grind their

maize, and for other services that such captives could do. Sometimes it

happened that going for wood or maize with them, they killed the Christian

that led them, and ran away with the chain; others filed their chains by

night with a piece of stone, wherewith they cut them, and use it instead

of iron. Those that were perceived paid for themselves, and for the rest,

because they should not dare to do the like another time. The women and

young boys, when they were once an hundred leagues from their country, and

had forgotten things, they let go loose, and so they served; and in a very

short space they understood the language of the Christians. From Uzachil

the Governor departed toward Apalache, and in two days' journey he came to

a town called Axille, and from thence forward the Indians were careless,

because they had as yet no notice of the Christians. The next day in the

morning, the first of October, he departed from thence, and commanded a

bridge to be made over a river which he was to pass. The depth of the

river where the bridge was made, was a stone's cast, and forward a

cross-bow shot the water came to the waist; and the wood whereby the

Indians came to see if they could defend the passage, and disturb those

which made the bridge, was very high and thick. The crossbowmen so

bestirred themselves that they made them give back; and certain planks

were cast into the river, whereon the men passed, which made good the

passage. The Governor passed upon Wednesday, which was St. Francis' day,

and lodged at a town which was called Vitachuco, subject to Apalache: he

found it burning, for the Indians had set it on fire. From thence forward

the country was much inhabited, and had great store of maize. He passed

by many granges like hamlets. On Sunday, the 25th of October, he came to

a town which is called Uzela, and upon Tuesday to Anaica Apalache, where

the lord of all that country and province was resident; in which town the

camp master, whose office is to quarter out, and lodge men, did lodge all

the company round about within a league, and half a league of it. There

were other towns, where was great store of maize, pompions, French beans,

and plums of the country, which are better than those of Spain, and they

grow in the fields without planting.

The victuals that were thought necessary to pass the winter, were gathered

from these towns to Anaica Apalache. The Governor was informed that the

sea was ten leagues from thence. He presently sent a captain thither with

horsemen and footmen. And six leagues on the way he found a town which

was named Ochete, and so came to the sea; and found a great tree felled,

and cut into pieces, with stakes set up like mangers, and saw the skulls

of horses. He returned with this news. And that was held for certain,

which was reported of Pamphilo de Narvaez, that there he had built the

barks wherewith he went out of the land of Florida, and was cast away at

sea. Presently the Governor sent John Danusco with thirty horse-men to

the Port de Spirito Santo where Calderan was, with order that they should

abandon the port, and all of them come to Apalache. He departed on

Saturday the 17th of Novemher. In Uzachil and other towns that stood in

the way he found great store of people already careless. He would take

none of the Indians, for not hindering himself, because it behooved him to

give them no leisure to gather themselves together. He passed through the

towns by night, and rested without the towns three or four hours. In ten

days he came to the Port de Spirito Santo. He carried with him twenty

Indian women, which he took in Ytara,

and Potano, near unto Cale, and sent

them to Donna Isabella in the two caravels, which he sent from the Port de

Spirito Santo to Cuba. And he carried all the footmen in the brigantines,

and coasting along the shore came to Apalache. And Calderan, with the

horsemen, and some crossbowmen on foot, went by land; and in some places

the Indians set upon him, and wounded some of his men. As soon as he came

to Apalache, presently the Governor sent sawed planks and spikes to the

seaside, wherewith was made a piraqua or bark, wherein were embarked

thirty men well armed, which went out of the bay to the sea, looking for

the brigantines. Sometimes they fought with the Indians, which passed

along the harbor in their canoes. Upon Saturday, the 29th of November,

there came an Indian through the watch undiscovered, and sat the town on

fire, and with the great wind that blew two parts of it were consumed in a

short time. On Sunday the 28th of December, came John Danusco with the

brigantines. The Governor sent Francisco Maldonado, a captain of footmen,

with fifty men to discover the coast westward, and to seek some port,

because he had determined to go by land, and discover that part. That day

there went out eight horsemen by commandment of the Governor into the

field, two leagues about the town, to seek Indians; for they were

now so emboldened, that within two crossbow shot of the camp, they came

and slew men. They found two men and a woman gathering French beans; the

men, though they might have fled, yet because they would not leave the

woman, which was one of their wives, they resolved to die fighting; and

before they were slain, they wounded three horses, whereof one died within

a few days after. Calderan going with his men by the sea-coast, from a

wood that was near the place, the Indians set upon him, and made him

forsake his way, and many of them that went with him forsook some

necessary victuals, which they carried with them. Three or four days

after the limited time given by the Governor to Maldonado for his going

and coming, being already determined and resolved, if within eight days he

did not come, to tarry no longer for him, he came, and brought an Indian

from a province which was called Ochus, sixty leagues westward from

Apalache; where he had found a port of good depth, and defence against

weather. And because the Governor hoped to find a good country forward,

be was very well contented. And he sent Maldonado for victuals to Havana,

with order that he should tarry for him at the port of Ochus, which he

had discovered, for he would go seek it by land; and if he should chance

to stay, and not come thither that summer, that then he should return to

Havana, and should come again the next summer after, and tarry for him at

that port; for he said he would do none other thing but go to seek Ochus

Francisco Maldonado departed, and in his place for captain of the footmen

remained John de Guzman. Of those Indians which were taken in Napetuca,

the Treasurer John Gayton had a young man, which said that he was not of

that country, but of another far off toward the sun rising, and that it

was long since he had traveled to see countries; and that his country was

called Yupaha, and that a woman did govern it; and that the town where she

was resident was of a wonderful bigness, and that many lords round about

were tributaries to her; and some gave her clothes, and others gold in

abundance; and he told how it was taken out of the mines, and was molten

and refined, as if he had seen it done, or the devil had taught it him.

So that all those which knew anything concerning the same, said that it

was impossible to give so good a relation, without having seen it; and all

of them, as if they had seen it, by the signs that he gave, believed all

that he said to be true.

On Wednesday, the third of March, of the year 1540, the Governor

departed from Anaica Apalache to seek Yupaha.

He commanded his men to go

provided with maize for sixty leagues of desert.

The horsemen carried their maize on their horses, and the foot men at

their sides; because the Indians that were for service, with their

miserable life that they led that winter, being naked and in chains, died

for the most part. Within four days' journey they came to a great river;

and they made a piragua or ferry boat, and because of the great current,

they made a cable with chains, which they fastened on both sides of the

river; and the ferry boat went along by it, and the horses swam over,

being drawn with capstans. Having passed the river in a day and a half,

they came to a town called Capachiqui. Upon Friday the 11th of March, they

found Indians in arms. The next day five Christians went to seek mortars,

which the Indians have to beat their maize, and they went to certain

houses on the back side of the camp environed with a wood. And within the

wood were many Indians which came to spy us; of the which came other five

and set upon us. One of the Christians came running away, giving an alarm

unto the camp. Those which were most ready answered the alarm. They

found one Christian dead, and three sore wounded. The Indians fled unto a

lake adjoining near a very thick wood, where the horses could not enter.

The Governor departed from Capachiqui and passed through a desert. On

Wednesday, the twenty-first of the month, he came to a town called Toalli;

and from thence forward there was a difference in the houses. For those

which were behind us were thatched with straw, and those of Toalli were

covered with reeds, in manner of tiles. These houses are very cleanly.

Some of them had walls daubed with clay, which showed like a mud-wall. In

all the cold country the Indians have every one a house for the winter

daubed with clay within and without, and the door is very little; they

shut it by night, and make fire within; so that they are in it as warm as

in a stove, and so it continueth all night that they need not clothes; and

besides these they have others for summer; and their kitchens near them,

where they make fire and bake their bread; and they have barbacoas wherein

they keep their maize; which is a house set up in the air upon four

stakes, boarded about like a chamber, and the floor of it is of cane

hurdles. The difference which lords or principal men's houses have from

the rest, besides they be greater, is, that they have great galleries in

their fronts, and under them seats made of canes in manner of benches; and

round about them they have many lofts, wherein they lay up that which the

Indians do give them for tribute, which is maize, deers' skins, and

mantles of the country, which are like blankets; they make them of the

inner rind of the barks of trees, and some of a kind of grass like unto

nettles, which being

beaten, is like unto flax. The women cover themselves with these mantles;

they put one about them from the waist downward, and another over their

shoulder, with their right arm out, like unto the Egyptians. The men wear

but one mantle upon their shoulders after the same manner; and have their

secrets hid with a deer's skin, made like a linen breech, which was wont

to be used in Spain. The skins are well curried, and they give them what

color they list, so perfect, that if it be red, it seemeth a very fine

cloth in grain, and the black is most fine, and of the same leather they

make shoes; and they dye their mantles in the same colors. The Governor

departed from Toalli the 24th of March; he came on Thursday at evening to

a small river, where a bridge was made whereon the people passed, and

Benit Fernandez, a Portuguese, fell off from it, and was drowned. As soon

as the Governor had passed the river, a little distance thence he found a

town called Achese. The Indians had no notice of the Christians: they

leaped into a river: some men and women were taken, among which was one

that understood the youth which guided the Governor to Yupaha; whereby

that which he had reported was more confirmed. For they had passed through

countries of divers languages, and some which he understood not. The

Governor sent by one of the Indians that were taken to call the cacique,

which was on the other side of the river. He came, and made this speech

following:

"Right high, right mighty, and excellent lord, those things which

seldom happen do cause admiration. What then may the sight of your

lordship and your people do to me and mine, whom we never saw? especially

being mounted on such fierce beasts as your horses are, entering with such

violence and fury into my country, without my knowledge of your coming. It

was a thing so strange, and caused such fear and terror in our minds, that

it was not in our power to stay and receive your lordship with the

solemnity due to so high and renowned a prince as your lordship is. And

trusting in your greatness and singular virtues, I do not only hope to be

freed from blame, but also to receive favors; and the first which I demand

of your lordship is, that you will use me, my Country, and subjects as

your own; and the second, that you will tell me who you are, and whence

you come, and whither you go, and what you seek, that I the better may

serve you therein."

The Governor answered him, that he thanked him as much for his offer

and good-will as if he had received it, and as if he had offered him a

great treasure; and told him that he was the son of the Sun, and came from

those parts where he dwelt, and traveled through that

country, and sought the greatest lord and richest province that was in it.

The cacique told him that farther forward dwelt a great lord, and that his

dominion was called Ocute. He gave him a guide and an interpreter for

that province. The Governor commanded his Indians to be set free, and

traveled through his country up a river very well inhabited. He departed

from his town the first of April; and left a very high cross of wood set

up in the midst of the market-place; and because the time gave no more

leisure, he declared to him only that that cross was a memory of the same

whereon Christ, which was God and man, and created the heavens and the

earth, suffered for our salvation; therefore he exhorted them that they

should reverence it, and they made show as though they would do so. The

fourth of April the Governor passed by a town called Altamaca, and the

tenth of the month he came to Ocute. The cacique sent him two thousand

Indians with a present, to wit, many conies and partridges, bread of

maize, two hens, and many dogs; which among the Christians were esteemed

as if they had been fat wethers, because of the great want of flesh meat

and salt, and hereof in many places, and many times was great need; and

they were so scarce, that if a man fell sick, there was nothing to cherish

him withal; and with a sickness, that in another place easily might have

been remedied, he consumed away till nothing but skin and bones were left;

and they died of pure weakness, some of them saying, "If I had a slice of

meat or a few corns of salt, I should not die. The Indians want no flesh

meat; for they kill with their arrows many deer, hens, conies, and other

wild fowl, for they are very cunning at it, which skill the Christians had

not; and though they had it, they had no leisure to use it; for the most

of the time they spent in travel, and durst not presume to straggle aside.

And because they were thus scanted of flesh, when six hundred men that

went with Soto came to any town, and found thirty or forty dogs, he that

could get one and kill it thought himself no small man; and he that killed

it and gave not his captain one quarter, if he knew it he frowned on him,

and made him feel it in the watches, or in any other matter of labor that

was offered, wherein he might do him a displeasure. On Monday, the twelfth

of April, 1540, the Governor departed from Ocute. The cacique gave him

two hundred Tamenes, to wit, Indians to carry burdens; he passed through a

town, the lord whereof was named Cofaqui, and came to a province of an

Indian lord called Patofa, who because he was in peace with the lord of

Ocute, and with the other bordering lords, had many days before notice of

the Governor, and desired to see him. He came to visit him, and made this

speech following.

"Mighty lord, now with good reason I will crave of fortune to requite

this my so great prosperity with some small adversity; and I will count

myself very rich, seeing that I have obtained that which in this world I

most desired, which is to see and be able to do your lordship some

service. And although the tongue be the image of that which is in the

heart, and that the contentment which I feel in my heart I cannot

dissemble, yet is it not sufficient wholly to manifest the same. Where

did this your country, which I do govern, deserve to be visited of so

sovereign and so excellent a prince, whom all the rest of the world ought

to obey and serve? And those which inhabit it being so base, what shall

be the issue of such happiness, if their memory do not represent unto them

some adversity that may betide them, according to the order of fortune?

If from this day forward we may be capable of this benefit, that your

lordship will bold us for your own, we cannot fail to be favored and

maintained in true justice and reason, and to have the name of men. For

such as are void of reason and justice, may be compared to brute beasts.

For mine own part, from my very heart with reverence due to such a prince,

I offer myself unto your lordship, and beseech you, that in reward of this

my true good will, you will vouchsafe to make use of mine own person, my

Country, and subjects."

The Governor answered him, that his offers and good-will declared by

the effect, did highly please him, whereof he would always be mindful to

honor and favor him as his brother. This country, from the first

peaceable cacique, unto the province of Patofa, which were fifty leagues,

is a fat country, beautiful, and very fruitful, and very well watered, and

full of good rivers. And from thence to the Port de Spirit Santo, where

we first arrived in the land of Florida (which may be three hundred and

fifty leagues, little more or less), is a barren land, and the most of it

groves of wild pine trees, low and full of lakes, and in some places very

high and thick groves, whither the Indians that were in arms fled, so that

no man could find them, neither could any horses enter into them, which

was an inconvenience to the Christians, in regard of the victuals which