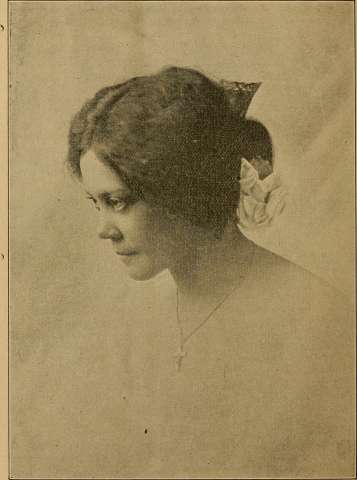

Alice Dunbar-Nelson.

“Brass Ankles Speaks.”

The “Race” question is paramount. A cloud of books, articles and pronunciamentos on the subject of the white man or girl who “passes” over to the other side of the racial fence, and either entirely forsakes his or her own race, to live in terror or misery all their days, or else come crawling back to do uplift work among their own people, hovers on the literary horizon. On the other hand, there is an increasing interest and sentimentality concerning the poor, pitiful black girl, whose life is a torment among her own people, because of their “blue vein” proclivities. It seems but fair and just now for some of the neglected light-skinned colored people, who have not “passed” to rise and speak a word in self-defense.

I am of the latter class, what E. C. Adams in “Nigger to Nigger” immortalizes in the poem, “Brass Ankles.” White enough to pass for white, but with a darker family background, a real love for the mother race, and no desire to be numbered among the white race.

My earliest recollections are miserable ones. I was born in a far Southern city, where complexion did, in a manner of speaking, determine one’s social status. However, the family being poor, I was sent to the public school. It was a heterogeneous mass of children which greeted my frightened eyes on that fateful morning in September, when I timidly took my place in the first grade. There were not enough seats for all the squirming mass of little ones, so the harassed young, teacher —I have reason to believe now that this was her first school — put me on the platform at her feet. I was so little and scared and homesick that it made no impression on me at the time. But at the luncheon hour I was assailed with shouts of derision — “Yah! Teacher’s pet! Yah! Just cause she’s yaller!” Thus at once was I initiated into the class of the disgraced, which has haunted and tormented my whole life — “Light nigger, with straight hair!”

This was the beginning of what was for nearly six years a life of terror, horror and torment. For in this monster public school, which daily disgorged about 2500 children, there were all shades and tints and degrees of complexions from velvet black to blonde white. And the line of demarcation was rigidly drawn — not by the fairer children, but by the darker ones. I had no color sense. In my family we never spoke of it. Indian browns and cafe au laits, were mingled with pale bronze and blonde yellows all in one group of cousins and uncles and aunts and brothers and sisters. For so peculiarly does the Mendelian law work in mixed bloods, that four children of two parents may show four different degrees of mixture, brown, yellow, tan, blonde.

In the school, therefore, I felt at first the same freedom concerning color. So I essayed friendship with Esther. Esther was velvet dark, with great liquid eyes. She could sing, knew lots of forbidden lore, and brought lovely cakes for luncheon. Therefore I loved Esther, and would have been an intimate friend of hers. But she repulsed me with ribald laughter — “Half white nigger! Go on wid ya kind!”, and drew up a solid phalanx of little dark girls, who thumbed noses at me and chased me away from their ring game on the school playground.

Bitter recollections of hair ribbons jerked off and trampled in the mud. Painful memories of curls yanked back into the ink bottle of the desk behind me, and dripping ink down my carefully washed print frocks. That alone was a tragedy, for clothes came hard, and a dress ruined by ink-dripping curls meant privation for the mother at home. How I hated those curls! Charlie, the neighbor-boy and I were of an age, a complexion and the same taffy-colored curls. So bitter were his experiences that his mother had his curls cut off. But I was a girl and must wear curls. I wept in envy of Charles, the shorn one. However, long before it was the natural time for curls to be discarded, my mother, for sheer pity, braided my hair in a long heavy plait down my back. Alas! It, too, was ink-soaked, pulled, yanked and twisted.

I was a timid, scared, rabbit sort of a child, but out of desperation I learned to fight. My sister, a few years older, was in an upper grade, through those six, fearsome years. She had learned early to defend herself with well-aimed rocks, ink bottles and a scientific use of sharp finger-nails. She taught me some valuable lessons, and came to my rescue when my nerve had given out. She had something of the spirit of an organizer, too, and had a gang of “yellow niggers” that could do valiant service in the organized warfare between the dark ones and the light ones.

I used to watch the principal of the school, and her fellow teachers with considerable interest as I grew older and the situation unfolded itself to me. As far as I can remember now, they were all mulattoes or very light brown. If their sympathies were with the little fair children, who were so bitterly persecuted, they never gave any evidence. The principal punished the belligerents with an impartiality that was heart-breaking. Years afterward, I learned that she had told my mother and the mothers of other girls of our class and complexion that she understood and appreciated our sorrows and troubles, but if she gave any evidence of sympathy, or in any way placed the punishment where she knew it rightfully belonged, the parents of the darker children would march in a body to the Board of Education, and protest against her as being unfit for the job.

Time went on, and a long spell of illness took me out of the school. That too, was due to color prejudice. There wasn’t a small-pox scare, and the Board of Health ordered one of those wholesale vaccinations that are sometimes worse than the disease. My mother sent a note to the principal asking her not to have me vaccinate. on the day selected, but that she would take me to the family physician that night, and send the certificate to school in the morning. The principal read the note, shook her head, looked at me sorrowfully, “You should have stayed at home today,” was her terse comment. So I was dragged, screaming and protesting to have my arm scratched with a scalpel instead of a vaccine point. Terror and rage helped the infection which followed, and for a long while my life was despaired of. It seemed certain that I would lose my arm. Somehow, I did not, and when I was well enough, about eighteen months later, to think of education, my mother sent me to a private school.

The bitterness that had been ingrained in me through those six fateful years, from six to twelve years of age, stayed. The new school was one of those American Missionary Schools founded shortly after the war, as an experiment in Negro education. Later, these same schools became the aristocratic educational institutions of the race. Though the fee was only a nominal one, it was successful in keeping out many a proletariat. Thus gradually, all over the South these very schools which were founded in a missionary spirit by the descendents of abolitionists for the hordes of knowledge-seeking freedmen, became in the second and third generations, the exclusive stamping grounds of the descendents of those who were never slaves, or of the aristocrats among freedmen.

And because here I found boys and girls like myself, fair, light brown, with educated parents, descendents of office holders under the reconstruction regime or of free antebellum Negroes, with traditions — therefore was I happy until the end of my high and normal school career.

Except for Eddie. I loved Eddie. He represented to me the unattainable, for he was in the college department, and he won prizes in oratory and debate and one day smiled at me understandingly when I was only a high school freshman. I walked on air for days. But Eddie was of a deep darkness, and refused to allow me to love him. With stern dignity he checked my fluttering advances. He would not demean himself by walking with a mere golden butterfly; far rather would he walk alone, he told me. It broke my heart for nearly a month.

Out in life, I found myself confronted, as did most of my friends and associates, with the same problems which had confronted the principal of that public school. I became a public school teacher. There were little dark children in my school. I had to watch them tormenting the little fair children, and not lift my hand to protect them, at the risk of a severe reprimand from my principal or supervisor, induced by complaints from parents. I had to endure in hot, shamed silence the innuendos constantly printed in the weekly colored newspaper — a sort of local Smart Set — against the fair teachers, every time one was seen with a new coat or hat. How could they afford to dress so well? was the constant query. Light colored girls, it was well known, were the legitimate prey of white men. Were not the members of the Board of Education helping out the meagre salaries of the better looking teachers? What price shame? Protest? The editor was a black man and owed allegiance to no proprietary. His daughter had failed to pass the teachers’ examination; she had failed in the normal school; she had failed in the high school. She was really stupid. But her father would not believe it. There were some darker girls who had made brilliant records in in school; were brilliant teachers. He shut his eyes to their prowess and vented his spleen upon the light ones who had succeeded.

After teaching a year or two, I had saved enough to embark upon my cherished ambition — to go to college, and so I came North. Here I found a condition just as bitter, but more subtle. You come up against a dead wall of hate and prejudice and misunderstanding, and you cannot tell what causes it.

During the summer session I had lived with a colored family in the town. The room was uncomfortable, the food not good, and the prices as high as in the school. Therefore, when I decided to return for the winter, I applied for and secured a place in one of the college cottages. This branded me at once among the colored students. I was said to be “passing,” though nothing was further from my mind — especially as there were no race restrictions in the dormitories. I tried to make friends among the colored girl students — all of whom that year were brown. Success came only after the hardest kind of hard work, and it was only a truce. I had to batter down a wall, which had doubtless been erected by my erstwhile dark-skinned landlady.

I had registered from my own religious creed. The rector of the white church in town called at once, made me welcome, and asked me to connect myself with his church. I waited three weeks for the colored minister to make a like overture. I would have preferred the colored church, for I had always taken an active part in our little church at home among my own people. But no gesture was made, so I went to the white church. Then an entertainment was given at the colored church. I saw a flier for the first time on the day of the affair, with my name down for a recitation. Naturally, I did not go on such slight notice, and forever afterwards was branded among the colored townspeople as a “half white strainer, with no love for the Race.”

And yet, in spite of all the tragedy of my childhood and young womanhood, I had not been able to develop that color sense. When I say this to my darker friends, they simply laugh at me. They may like me personally; they may even become my very good friends; but there is always a barrier, a veil — nay, rather a vitrified glass wall, which I can neither break down, batter down, nor pierce. I have to see dear friends turn from a talk with me, to exchange a glance of comprehension and understanding one with another which I, nor anyone of my complexion, can ever hope to share.

In the course of my peregrinations, after college days, I came to teach in a small city on the Middle Atlantic Seaboard. A little city where hate is a refined art, where bitterness is rife, and where prejudice is a thing so vital and potent that it makes all other emotions seem pale and insignificant. I shall never forget the day that I was introduced by the principal to the faculty of the high school where I was to teach. There were two other faces like mine in the group of thirty. The two who looked like me, exchanged glances of pity — the others measured me with cold contempt and grim derision. A sweat broke out on me. I knew what I was up against and an icy hand clutched my heart. I felt I could never break this down; this unreasoning prejudice against my mere personal appearance.

With the children it was the same. The day I walked into my classroom, I head a whisper run through the aisles, “Half white nigger!” For a moment I was transplanted to that first day at school twenty odd years ago.

The agony of that first semester! The nerve-racking terror of never knowing where there would be an outbreak of unreasoning prejudice among those dark children, venting itself in a spiteful remark, and undoing in a moment what I had spent weeks to create. The heart-breaking rebuffs when I tried to be cordial with my fellow-teachers; the curt refusals to walk home with me, or to go to church or places of amusement. The scathing denunciations of irate parents when their children did not get the undeserved marks they wanted. I was accused of everything except infanticide. Mine had been the experiences of the other two teachers, I was told. The principal protected as far as he could, but what can a busy man do against a whole community? If I had a dollar for every bitter, scalding, hopeless tear that I shed that first school year, I should be independently wealthy. It was only sheer grit and determination not to be beaten that kept me from throwing up the job and going back home.

Small wonder, then, that the few lighter persons in the community drew together; we were literally thrown upon each other, whether we liked or not. But when we began going about together and spending our time in each other’s society, a howl went up. We were organizing a “blue vein” society. We were mistresses of white men. We were Lesbians. We hated black folk and plotted against them. As a matter of fact, we had no other recourse but to cling together.

Much water has passed under the bridge since those days, and I have lived in many other communities. Save for size, virulence, and local conditions, the situation duplicates itself. Once I planned a pageant in one community. “You’ll never put it over,” my friends adjured me; “You haven’t enough pull with the darker people.” But I planned my committees always to be headed up by black or brown men or women, who in turn selected their aides, thus relieving me of all responsibility. It went over big, in spite of misfits on committees. But had I actually placed thereon men and women of real ability, who could have handled the situation more efficiently, the whole thing would have fallen to the ground if they were light in color.

I have served on boards and committees of schools, institutions, projects. I have seen the chairmen, or those with appointing power, look at me apologetically, and name someone whom they knew and I knew was unfit for a place, where I could have best helped and worked. But they did not dare be accused of partiality on account of color. I have had my offers of help in charity affairs refused, or if accepted grudgingly, credit withheld or services forgotten. I have been turned down by my own race far more often than many a brown-skinned person has been similarly treated by the white race. I have been snubbed and ostracized with subtle cruelties that I am safe to assert have hardly been duplicated by the experiences of dark people in their dealings with Caucasians. I say more cruel, for I have been foolishly optimistic enough to expect sympathy, understanding and help from my own people — and that I receive rarely outside of individuals of my own or allied complexion.

As if there is not enough stupid cruelty among my own, I have had to suffer at the hands of white people because of my likeness to them. On two occasions when I was seeking a position, I was rejected because I was “too white,” and not typically racial enough for the particular job. Once when I was employed in a traveling position during the war, I came into headquarters from a particularly exhausting trip through the South. There I had twice been put off Jim Crow cars, because the conductor insisted that I was a white woman, and three times refused food in the dining-car, because the colored waiters, “tipped off” the white stewards. When I reached headquarters I found three of my best so-called brown skinned friends protesting against sending me out to work among my own people because I looked too much like white.

Once I “passed” and got a job in a department store in a large city. But one of the colored employees “spotted” me, for we always know each other, and reported that I was colored, and I was fired in the middle of the day. The joke was that I had applied for a job in the stock room where all the employees are colored, and the head of the placing bureau told me that was no place for me — “Only colored girls work there,” so he placed me in the book department, and then fired me because I had “deceived” him.

I have had my friends meet me downtown — in city streets and turn their heads away, so positive that I do not want to speak to them. Sometimes I have to go out of my way and pluck at their sleeves to force them to speak. If I do not, then it is reported around that I “pass” when I am downtown — and sad is my case among my own kind then.

There are a thousand subtleties of refined cruelty which every fair colored person must suffer at the hands of his or her own people. And every fair colored woman or man, girl or boy who reads this knows that I have not exaggerated. If it be true that thousands of us pass over into the white group each year, it is due not only to the wish for economic ease and convenience, but often to the bitterness of one’s own kind. It is not to be wondered at that lighter skinned Negroes cling together in their respective communities. It is not so much that they dislike the darker brethren, but the darker brethren DO NOT LIKE THEM.

So I raise my tiny voice in all this hub-bub of “Race” clamor; all this wishy-washy sentimentalism about the persecuted black ones of the race, and their inability to get on with their own kind. As in Haiti, as in Africa, the bitterness and prejudice have always come from the blacks to the yellows. They have been the greatest sufferers, because they have had, perforce, to suffer in silence. To complain would be only to bring upon themselves another storm of abuse and fury.

The “yaller niggers,” the “Brass Ankles” must bear the hatred of their own and the prejudice of the white race. If they do not choose to go over to the other side — and tens of thousands feel, like myself, that there is no gain socially in so doing, though there may be some economic convenience — then they are forced to draw together in a common cause against their blood brothers who visit upon them hatred and persecution.

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Dunbar-Nelson, Alice. “Brass Ankles Speaks.”