Louisiana Anthology

Frances Fearn, ed.

Diary of a Refugee.

Edited By

Frances Fearn

Illustrated By

Rosalie Urquhart

COPYRIGHT 1910, By Frances Fearn

Published by New York Moffat, Yard & Company

Printed by The Quinn & Boden Co. Press in Rahway, NJ

TO CLARICE IN FIVE GENERATIONS

May the Clarice of to-day reincarnate the spirit and

the flesh of those four noble women of her name,

affiliating the child through her forbears with the soul

and body of her Great, Great Grandmother Clarice

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

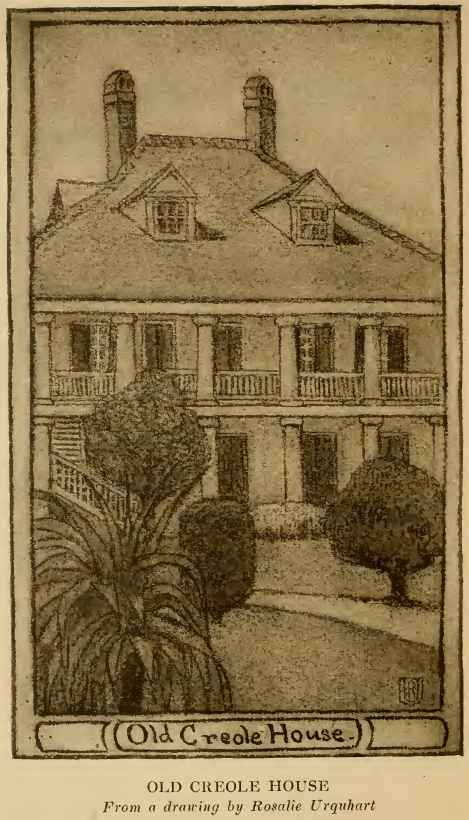

- The Old Creole House . . . . .

Frontispiece

- The Old Plantation House . . . . .

14

- Evangeline Oak . . . . .

22

- The Dark Forest . . . . . 32

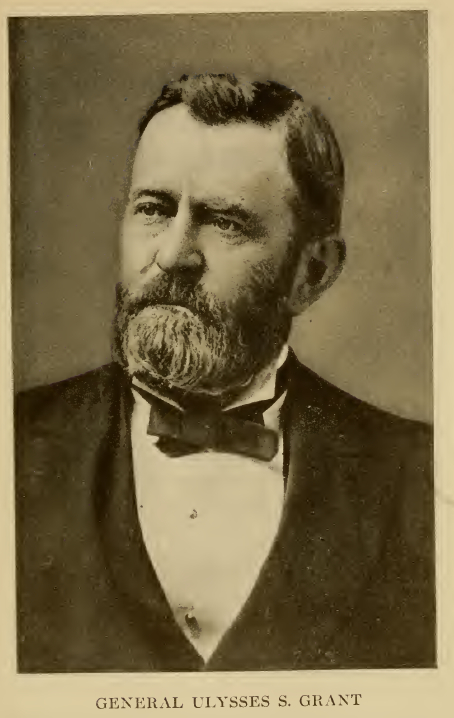

- Gen. U. S. Grant . . . . .

40

- The Camp on the Plains . . . . .

54

- Mexican Water Jars . . . . .

72

- Havana Harbor . . . . .

78

- Clarice . . . . . 84

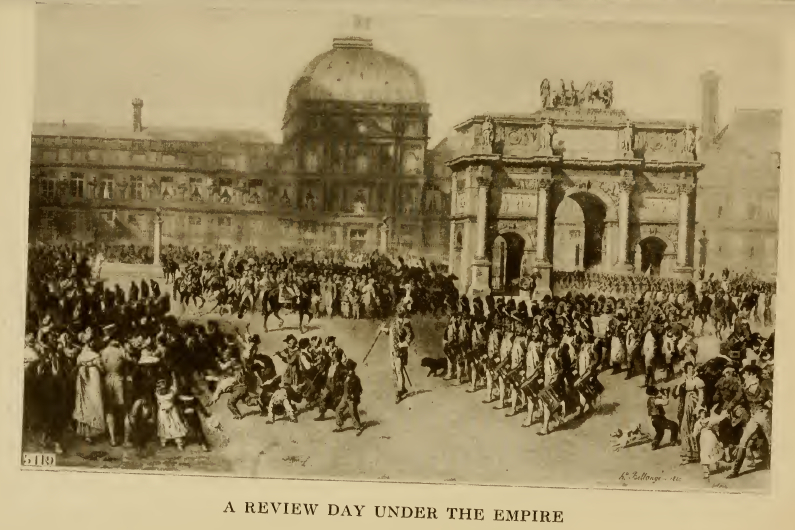

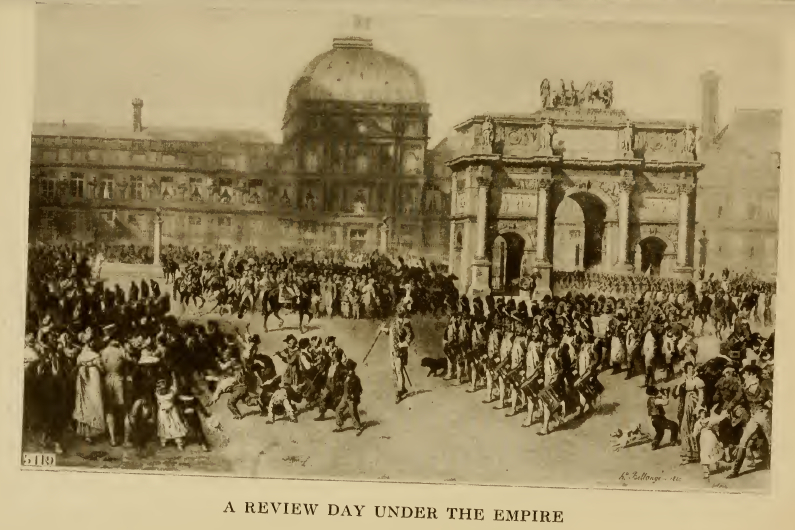

- A Review Day under the Empire . . . . .

94

- Napoleon III . . . . .100

- Christine Nilsson . . . . .102

- The Empress Eugénie . . . . .

106

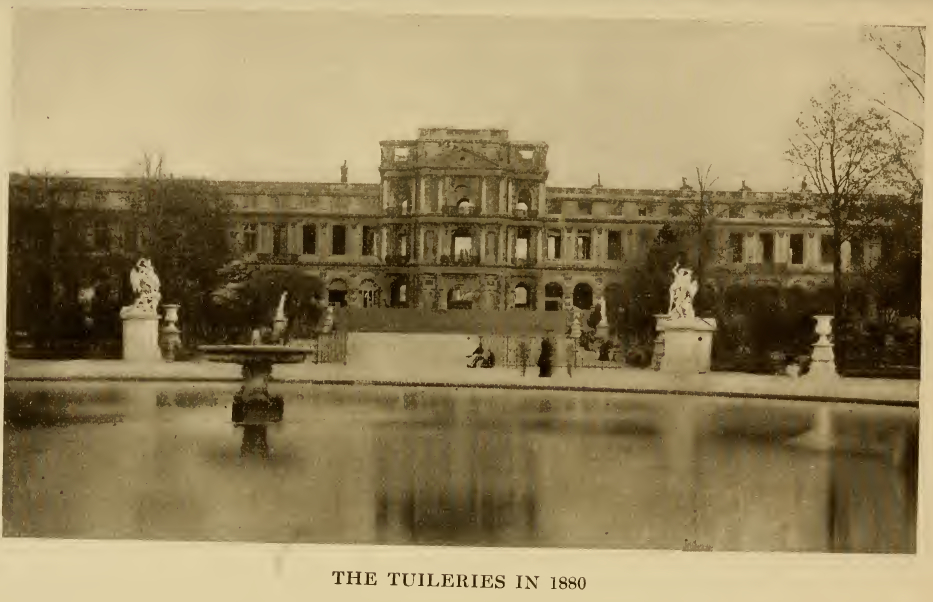

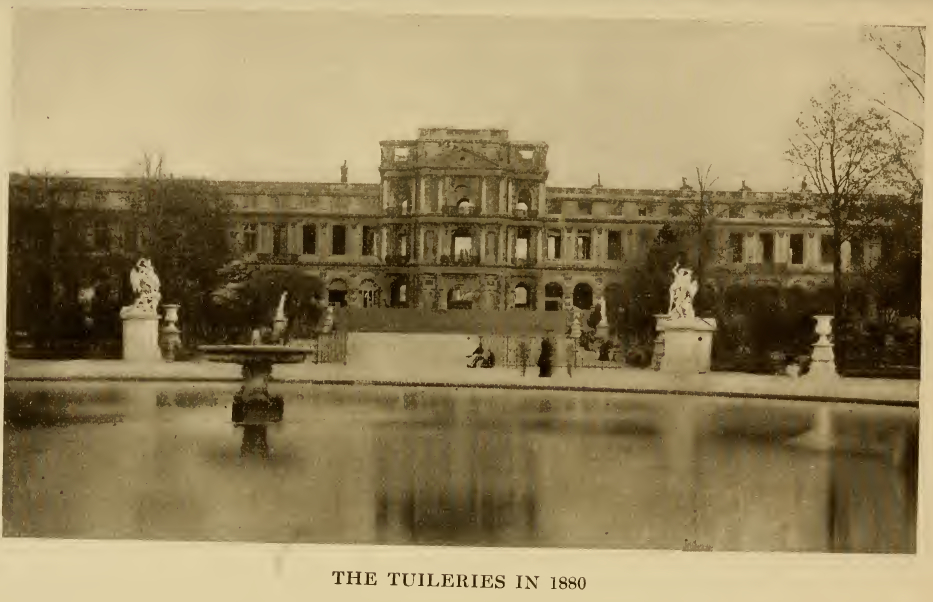

- The Tuileries in 1880 . . . . .116

- The Writer of the Diary . . . . .

124

- The Clarice of To-day . . . . .

140

INTRODUCTION

IT was while I was spending the summer in

Virginia, where I had gone in search of quiet

and rest, after my extensive tour through the

country, that I saw in one of the papers an

appeal from a Historical Society, to those who

had any real data in regard to the Civil War to

publish it, as so many who were connected with

the war on both sides were rapidly dying off.

I remembered a diary kept during the war

by a member of my family, who was a woman

of rare qualities of brain, and heart, with an

unusually just mind. I felt sure that anything

written by her would be so liberal and fair that

it could not fail but prove interesting reading,

for the people of both the North and the South.

From what she had told me, and remembering

as a child many things myself, I am able to fill

in the gaps when necessary.

While preparing the Diary for publication,

I saw the possibility of making an interesting

drama from it, so I have dramatized it,

giving the play as title the famous words of

General Grant, “Let us have peace.” I have also

obtained permission of General Frederick

Grant to have his father, General U. S. Grant,

impersonated on the stage.

Several years ago I read a book called

“Ground Arms,” by an Austrian noblewoman,

which made a strong impression upon me, for it

was written with great power and ability, and

was an eloquent protest against the evils of war.

If either “The Diary of a Refugee” or the play

can in any way convey the horrors of war to the

public and make them feel as I do in regard

to the terrible suffering and misery which it

entails upon so many innocent people, then

indeed I shall feel that my work has not been in

vain. This is the spirit that has prompted me to

edit the Diary and to dramatize it. I hope the

public, on reading the book and seeing the play,

will take my representation of Southern life as a

true one, and after following the family through

their trials and troubles, will understand with

what

great sincerity and thankfulness they echo

General Grant's famous words, “Let us have

peace.”

It is with great pleasure that I give a letter

received from Admiral Dewey expressing his

approval of the description given in the “Diary

of a Refugee” of the battle of Port Hudson, as

the Admiral was on the“Mississippi” at the

time.

OFFICE OF

ADMIRAL OF THE NAVY,

WASHINGTON.

April 14, 1910.

My dear Mrs. Fearn:

I have read the extract from your mother's diary

with the greatest interest. I would suggest that you

publish it just as she saw it at the time, and it will form

a very interesting history of that part of the Civil War.

With sincere regards,

Faithfully yours,

George Dewey.

This was in answer to a letter that I wrote

asking him if he could suggest any changes or

additions to the account of the battle given in

the Diary.

Frances Fearn.

DIARY OF A REFUGEE

crescent plantation,

bayou lafourche, la.,

april, 1862.

Saturday.

WITH

a sad heart and a feeling of great

depression I went on my usual round of visits

to-day. First to the negroes’ hospital, then to

see the young mothers who have recently been

confined; afterwards to the children’s ward,

where they are kept during the day under the

care of an old mammy, while their mothers are

at work in the fields. These and many other

daily duties incumbent upon the mistress of a

plantation, leave one few spare hours.

I found the inmates of the hospital awaiting

me with great impatience and eagerness, but I

fear they missed my usual cheerfulness in spite

of the effort I made to bring all the cheer and

comfort I could to the poor suffering ones. It

was impossible not to feel the

foreshadowing of the evil days that must

inevitably come to us with the fall of New

Orleans.

One of my greatest pleasures is in

distributing the delicacies from our own table

to the invalids. As coming from the master’s

table they are greatly appreciated.

To-day, as I sat and talked with the different

ones, I must have shown in my face or manner

the great anxiety that I was feeling, and perhaps

I was a little more tender over them than usual,

for they looked up into my face, and one said,

“Ole missus, what is ailin’ yo’? Yo’ ain’t never

looked so sad befo’.” My usual gayety and

light-heartedness must indeed have left me; how

could it be otherwise, feeling as I do the sense

of coming danger? With the fall of New

Orleans in the course of a short time we must

leave our dear old home, and what will then

become of the hospital and its inmates? This is

my special work; I organized it and have carried

it on under the direction of our excellent family

physician, who attends and cares for the

slaves as well as for the family. We have had

some of the more intelligent negro women

trained and taught to be nurses, for they make

very good ones. Apart from any illness that the

slaves are subject to, we often have accidents

of a more or less serious nature, which must

inevitably be the case where there is such a

great variety of work. The plantation is really

like a village, with its carpenter and blacksmith

shops, its brick masons, and other trades, in

which many of them show great skill and

ability.

As it is Saturday, the day on which the

women and children come to me for any

clothes that they may need, I have had great

pleasure in giving out to many of them the

things that they ask for; of my many duties the

one I enjoy most is the privilege my husband

gives me of distributing the clothes to the

women and children. The materials are bought

in large quantities at wholesale prices. A

certain number of seamstresses are detailed

to make them up into all kinds of necessary

garments for the men and women and children.

After they are made, they are put in sets

and kept in a large room, used only for that

purpose. Each person is allowed a certain

number of every necessary article of clothing. I

am always pleased when I can reward a young

woman, girl, or child for good conduct by

giving an extra pretty dress, handkerchief, or

perhaps a string of bright beads, as the latter is

greatly prized.

When the crops have been good, my husband

distributes a sum of money to the negroes in

proportion to the extra amount of work that

they have done during the grinding season. It

is the occasion for great rejoicing and gayety.

Everyone puts on their best clothes and a

general feeling of good humor prevails. The

gallery is gayly decorated where my husband

sits at the table on which is placed the gold

coin, and as each negro comes up in line, their

name is called by the overseer and they receive

the amount due to them according to the work

that they have done and their good conduct

during the year. The women and children are

included. The young mothers receive a present

for their babies and it is not an unusual

occurrence for a mother to borrow an extra

baby to present, so as to receive an additional

present! When found out, this creates no end

of joking and amusement. We all know it is

sometimes difficult for white mothers to

recognize their own offspring, but how much

more difficult must it be for a man to know the

difference between two black babies. Poor

James is often fooled! It makes a picturesque

scene, with the decorations of the gallery, the

mixture of gay colors, the costumes of the

negroes, and the vivid greens and bright

tropical coloring of plants and flowers in the

garden that surrounds the house.

The distribution of this money takes place

immediately after the sugar is made. When the

grinding season is over a week’s holiday

follows, during which the negroes, with great

joy, prepare for the ball that is given at the end

of the week. The negro women are allowed to

go in the wagons used for hauling the cane to

Donaldsville, the nearest village,

where they are given the great pleasure of

spending their money on the necessary

adornment for the ball. Their great ambition

is to be able to disappear from the ballroom

several times during the evening, and to

reappear with some startling addition to their

toilets, thereby exciting the envy of the others.

We all take the greatest pride and pleasure

in decorating the ballroom with wreaths of

evergreen, flags, etc., and my husband gives

them carte blanche for their supper as regards

the killing of chickens and making of cakes, ice

creams, and sweets of all kinds, for which they

have a great weakness. The ball is opened by

members of the family dancing the first set of

Lancers. After that the floor is given up to the

negroes, who enter into the enjoyment most

heartily. Any stranger looking in upon this

scene would not believe that they were slaves.

But why should they not be light-hearted? They

have no responsibilities, they are well cared

for, and clothed and fed? If the war ends

unsuccessfully for us, will they, with their

freedom, remain thus?

The night of the ball was clear and beautiful,

the full moon bringing out all objects with a

distinctness more vivid even than by day. The

house and surrounding grounds were deserted,

all having gone to the ball. My husband had

been detained, so we were the last to leave the

house. The road to the low building where the

ball was going on was through a long avenue of

overarching trees. Not a sound was to be heard

or a moving object in sight, when suddenly

there appeared in the path before us, as though

coming up from the ground, a big negro, who

held in his hand one of the large formidable

knives used for cutting the cane. It glistened in

the moonlight as he advanced threateningly

towards my husband. He is the one vicious and

really bad negro on the plantation. Being very

lazy he had run off three months before, so as

to avoid the hard work necessary for all hands

during the grinding season.

My husband’s influence over the slaves is very

great, while they never question his authority,

and are ever ready to obey him implicitly,

they love him! It was only necessary for

him to command this negro to put down his

knife, for the darkey to fall at my husband’s feet

and beg for forgiveness. The negro’s reason for

returning at this time was in order to go to the

ball. He said, “Ole massa, do what yo’ will with

me, only le’ me go to the ball to-night!” My

husband gave his permission, but said, “I’ll

not punish you, as you will receive your

punishment at the hands of those whom you left

to do your share of the work.”

It was a terrible scene when he entered the

ballroom. His fellow-slaves fell upon him, and

it was with great difficulty that he was finally

rescued after a severe beating at their hands

and being put out of the ballroom. It is a curious

fact that the good workers have no sympathy

for those who run off and shirk their duty.

Sunday night.

The service that we had to-day in our little

church on the plantation seemed to me unusually

touching and pathetic. As I watched the

faces of the slaves who were so unconscious

of any impending evil in their lives, I felt

instinctively that it was the last service that we

should have together.

This church was built by my husband for the

benefit of the slaves. Our dear pastor is from

the North, he is very talented and a most

excellent man. Curiously enough, he came

South full of bitterness against all slave-owners.

To his great astonishment, my husband, on first

meeting him, employed him at a salary of five

thousand dollars a year to take care of the

religious education and training of the negroes.

He accepted, feeling he had found a field for

great missionary work; but not so much in

regard to the negroes as to what he hoped to be

able to accomplish with the wicked, benighted

Southern slave-owners! He came fully prepared

to preach a crusade against us, but he has

succeeded in making us all love him, and I have

every reason to believe that he has changed his

opinions in many respects regarding us.

Our plantation life has been a revelation to

him, so different is it from what he expected.

His influence over the slaves has been

wonderfully good. He has educated one of the

more intelligent men to become a preacher,

and we go often to hear him when he preaches

at the evening services. It is extraordinary what

remarkable musical talent many of the negroes

have, and also very sweet voices so that the

singing in church is really unusually good.

Monday.

Another anxious day! The steamboats “Mary

Tee” and “The Lafourche,” chartered by my

husband, are being loaded with sugar. The fires

are kept up day and night ready to start as soon

as the dreaded news reaches us that the Federal

gunboats have passed the forts. The conduct of

the negroes, and their evident desire to show

their sympathy and readiness to aid us in every

way in these trying times, is very touching. The

more so as they know that the

arrival of the Federals will mean their freedom.

Wednesday.

We were aroused in the middle of the night

by the arrival of Richard. He had ridden for

twenty-four hours, only stopping to change

horses; as he brought us the fatal and dread

tidings that New Orleans was in the possession

of the enemy. We were a sad little group that

gathered around the breakfast table, each one

trying to cheer the other with the hope that our

fate may not in reality be as dreadful as we

anticipated.

This beautiful spring morning, the season of

the year when the dear old place is at its best

with a great abundance of roses of many

varieties, none more lovely in the richness of

its color than the “Cloth of Gold”; these with

the greatest profusion of climbing roses that

cover the pillars of the galleries, the fences,

and run riot everywhere with a dark background

of all the rich greens of the tropical plants,

make a lovely scene, such as

one is loath to leave. Never did the old typical

Southern home, in its simplicity and comfort,

seem so attractive, with the large rooms,

high ceilings, and all that tends to make a

home beautiful and comfortable, filled with

interesting souvenirs of the many places that

we have visited in our extensive travels. The

most insignificant article seems to have a

special value, and as I look upon it all, I feel

instinctively that I shall never see it again.

Although I am a Virginian by birth and have

lived all my life in the South and West, I have

never approved of slavery. It has been one of

the greatest sorrows and trials of my life that

my husband should own so many slaves, both

in Louisiana and Kentucky. This has made me

feel the great responsibility resting upon us

in the care of them, and I am thankful to say

my husband has shared it with me, and always

been willing and anxious to mitigate their

condition as much as possible, by being kind,

considerate, and just in his treatment of them.

Their appreciation of what he has done for

them has been clearly

shown in their love and devotion to him and to

each member of the family.

Last year, on an occasion when my husband

had to leave us for many days, and there was no

white person living within several miles of the

house, before going he called the negroes

around him and told them that he was going off

to be absent some time, and to their care and

protection he entrusted their mistress and his

child. He felt that they would allow nothing to

harm his loved ones during his absence. The

night after he left was a beautiful, clear

moonlight night. The house is entirely

surrounded by a wide balcony on which all the

front rooms open with French windows. In the

middle of the night I heard an unusual sound and

got up to ascertain the cause of it. As I opened

my door I saw innumerable figures rise up in

the moonlight, and a chorus of voices called

out, “Don’t be afraid, ole missus, we are just

here guarding you and the child for ole massa.”

I went back to bed feeling that we were safe in

their keeping, but I lay awake many hours wondering

what freedom would do for these child-like

people. Would they be improved by it, or

would they lapse back into a savage condition

when the firm and guiding hand of the master

was taken from them?

My son’s news of the fall of New Orleans

was confirmed while we were at breakfast by a

man on horseback, riding rapidly down the

Bayou road, calling out as he went by, “The

Yankees are coming!” It was the signal for us

to gather up the things we most valued of our

belongings and to go on board “The

Lafourche,” which was waiting with steam up in

the Bayou, fronting the house, to carry

us off.

It was a sad little group that left the dear old

home. We were so overcome with sorrow and

terror as to our future fate that we gave no

thought of what we were taking with us. The

negroes were far more thoughtful for us; one

picked up my husband’s favorite sofa, another

his chair, one even went so far as to sweep the

silver on the breakfast table into a handy

clothes-basket and carry it on board.

Indeed, we had great cause afterwards to be

very thankful to them for their forethought in

the provision that they made for our comfort

and for the supplies that they put on board, the

latter were sadly needed before our journey

was over.

My heart was torn at the separation from my

son Richard, who had returned to join his

company. We Southern women need all our

strength and courage to give up our sons and

loved ones, our homes are taken from us, and

we must become refugees!

My husband has been able to put on board

the steamboat about one-half of this year’s

crop of sugar. The plantation is only three

miles from Donaldsville, at the mouth of the

Bayou Lafourche. When we entered the

Mississippi River, it had become a seething

mass of craft of all kinds and description that

could be made into possible conveyances to

carry away the terror-stricken people who were

flying from their homes with their loved ones

and treasures, all making a mad rush for the

mouth of Red River.

We who had lived on the plantation, with the

greatest abundance of food and supplies of all

kinds, have not felt the effects of the war, but

now that we are refugees and in a part of the

country that has been drained of much that it

produced, and the white laboring man has

joined the army, leaving the fields but scantily

cultivated, we begin to feel the want of food.

Our party consists of seven in the family and

eighteen servants, and the officers and crew of

the steamboat, making many mouths to feed;

frequently we are not allowed to land if there

are few provisions in the place, and are met

at the wharf by men with shotguns, who not

politely, but very forcibly, request us to move

on, and it is not an unusual thing for us to have

nothing but sweet potatoes and corn bread to

eat for days at a time.

After months on board the steamboat, with

bad water as well as a lack of proper food, we

are all beginning to feel the effects, so that my

husband has decided to go to Alexandria for

the winter.

II

ALEXANDRIA, AUGUST.

We arrived here none too soon as two of

the family have typhoid fever, my daughter and

niece. It would be impossible to tell of all the

kindness and hospitality that we have received

at the hands of these dear kind people. Dr.

Davidson, not only a very skilled and

remarkable physician, but loved by all who

know him, is a most generous man, giving us

much that cannot be bought for any amount of

money. These are times when the possession

of money means nothing, for there is nothing

to buy with it. All the more one appreciates the

kind generous hearts who are willing to share

with others less fortunate than themselves

whatever they may possess in the way of

provisions.

A month later.

Now that my invalids are convalescent, my

husband has rented a hotel which was once a

favorite summer resort, twenty-five miles from

Alexandria, in a pine forest, where there is also

a very good spring of mineral water, which is

supposed to be a good tonic suitable for

strengthening our poor invalids.

Pine Forest.

What a remarkable place! The hotel which

could accommodate two or three hundred

people, has been abandoned and left to go to

ruin. The furniture has been taken away, only a

few beds remain with corn-shuck mattresses,

and chairs, the seats of which are made of

cowhide. It presented a forlorn appearance as

we drove up. I must say that my heart sank at

the prospect of making a home here. It seemed

so hopeless.

Tuesday.

Yesterday I drove for twenty miles with Jack

in the wagon drawn by four horses, carrying

with me several hundred dollars with which to

buy provisions. Imagine my despair and

disappointment when I returned

at night with one pint bottle of milk, a dozen

eggs, a small sack of corn meal, and one

chicken to feed twenty hungry mouths! What

really saves us from starvation is a beautiful

clear stream that runs through this forest. In it

are the most delicious freshwater trout, at least

they seem so to us. My husband delights in

awaking the children in the morning at an early

hour with the call, “Get up, girls, fish, or no

breakfast.” So he would have us all out fishing

most seriously for the food of the day. We

cook them out of doors (we have no stove) in

our only cooking utensil, — a frying-pan. There

is also a coffee-pot, which we look at with

longing eyes in anticipation of the day when we

shall have some coffee made in it, but as yet we

have not been able to find any coffee that we

could buy.

Ten days later.

Great excitement yesterday. We saw an

Indian coming from the forest with a deer on

his back. The shout that we sent up must

have reminded him forcibly of his tribe when

on the war path. He started to run, but there was

no escape for him, he was too quickly

surrounded by a hungry crowd. The gold pieces

that we held out to him very soon changed his

fears to amusement and wonder, for he had

never seen so much money before. The deer

was quickly dropped at our feet, and the money

grasped with great eagerness, for he was all

anxiety to get away, thinking perhaps that we

might regret our bargain. He little knew how

hungry we were, and what a feast that deer

represented to us. Never did anything taste so

good.

We had another piece of good luck. One of

the children found a tomato bush in an old,

abandoned vegetable garden. These, added to

the venison, made indeed a feast fit for the

gods in our eyes.

In spite of the lack of food and comforts we

are all improved in health, for the pure air of

this pine forest and the water have proved

such good tonics that our invalids have

entirely recovered.

With the approach of winter and the

condition of the house being such that it

affords no protection against the cold (no glass

in the windows and the roof open in many

places), my husband has decided to go back to

Alexandria for that season. The question of

clothes has become a very serious one; it is

not that we are concerned as to the latest

fashions. Oh, no. It is too serious for that small

consideration. I really do not know how we

could have got through the winter if we had not

had a great piece of good luck. While living on

the steamboat, my husband received a letter

from the owner of a country store on Bayou

Plaquemine, offering to sell him the contents

of the store, for what seemed a very large sum

of money, if my husband would pay him half of it in

sugar and the rest in gold. The Bayou was too

narrow for us to go in the steamboat, so we

rowed up in small boats, starting at dawn.

It was a day never to be forgotten. The

beauty and picturesqueness of the Bayou have

been made famous in Longfellow’s “Evangeline.”

In our imagination we passed the very

spot where Evangeline was asleep, and Gabriel,

her lover, went by not seeing her.

From the realms of poetic imagination we

were suddenly brought face to face with the stern

realities of life, for we were badly in need of

clothes. My husband had no list of the contents

of the store, so we were unable to form any idea

of what we might find. When we reached it, on

opening the door he said, “Now, girls, it is all

yours,” which was as welcome a sound to us as if

he was offering us a gold mine. Just imagine a lot

of women without sewing materials of any

kind! — no thread, needles, buttons, etc., to say

nothing of dress materials — turned loose even in

a country store. No words can describe the

excitement and exultant exclamations on opening

a box to find the very things that we needed most,

as we had become very simple in our wants and

tastes. There was no question of scorning

anything. Oh, no! We were overjoyed when we

found about sixty yards of old-fashioned plaid

barege, and such

a plaid! The size of the squares and odd

mixture of colors were very startling, but that

made no difference. We rose above such small

matters, it meant a dress.

We filled the boat with our newly acquired

possessions and returned to the steamer

feeling happier and much relieved in our

minds, in regard to the replenishing of our

wardrobes for the winter. One must see the

contents of an American country store to

appreciate the great variety and possibilities it

affords, as it contains a little of everything.

ALEXANDRIA.

We are now settled for the winter in rather a

well-furnished house, and are quite

comfortable. I have started the children to

school, my daughter and nephew. My husband’s

sugar is a blessing, not only to us, but

throughout this part of the country, as with it

he is able to get in exchange much that cannot

be bought with money. His great desire is to

get together by means of his sugar a supply of

provisions for some of our Army

posts that are beginning to feel the want of

food, owing to the blockade. How the Southern

women suffer, thinking of our dear brave young

sons, who have been brought up in the greatest

luxury and ease, many fighting in the ranks of

our Army, enduring the greatest hardships and

privations. We know that they are doing it

without a murmur and we are proud of their

brave and unselfish lives.

ALEXANDRIA.

APRIL, 1863.

Shall I ever be able to recall all that I have

gone through since I last made an entry in my

diary? It seems an eternity, so much have I

suffered and such terrible scenes have I

witnessed.

When my husband had succeeded in

collecting a sufficient quantity of provisions

he offered them to the Government for the

relief of the garrison at Port Hudson, where

my son Richard was stationed. The

Government gave him the use of a steamer and

the

permission to take us with him. He went with

the hope of being able to see Richard. The trip

down the river was made safely, without any

accident worth recording. But on the afternoon

of March 14th we felt the signs of excitement,

for when we got in sight of Port Hudson it was

evident that the Federal gunboats were getting

into line for the approaching battle. The Captain

felt a hesitation about landing, but we were too

anxious to see Richard, so after a consultation

we decided to risk it, and most thankful were

we for having done so.

Strangely enough the general in command

selected Richard (without knowing that we

were on the steamer), to bring the order to the

Captain telling him not to remain at the

landing, but to go around the bend of the river

in front of Port Hudson, to await the result of

the battle. In case the enemy passed we were to

go up the river to Port de Russy. The Captain

disobeyed the order to the extent of remaining

fifteen minutes, enabling us to have these

precious moments

with our dear boy. By this time it was dark. The

order was for all lights to be put out on the

boat. Even blankets were held up in front of the

engine fires as we crept around the bend. We

had not gone far, however, before the Federal

gunboats opened fire upon us, the shells falling

fast and thick. Had one of them struck our frail

wooden steamer it would have been

instantaneous death to all and complete

destruction of the steamer.

Our escape from destruction or capture was

owing to the fact that the gunboat “Mississippi”

which was detailed to capture us was struck

by a shell from our forts, and her machinery

being disabled she ran aground and caught fire.

We were near enough to hear the commands

given on the “Mississippi” and to witness the

terrible scenes that followed when she caught

fire. I shall never forget the terrors of it, and

not until we were safely around the bend of the

river in front of Port Hudson did we realize the

extent of our own danger, and how narrow an

escape we had made. We completely lost all

thought or consciousness of any personal

danger to ourselves. We could think of nothing

but Richard and the gallant defenders of our

forts. The fleet against them looked so grim

and formidable that our hearts were filled with

terror at the thought of what their fate might

be.

After we reached our point of refuge we

waited, according to our instructions, until

midnight, when we saw the Federal gunboat

“Hartford” pass the forts. This was to be the

signal for us to go on to Fort de Russy, seventy

miles up the river, the garrison there being in

great need of food. We were able to give

them some of the supplies, but it was not long

before the fort was taken and we were

compelled to return to Alexandria. I fear it will

be a long, anxious waiting before we can learn

Richard’s fate.

Several months later.

My husband has at last joined us after many

months of anxiety and uncertainty as to his

fate, being unable to communicate with

him or in any way get news of him. He returned

to the plantation, as he felt anxious about the

slaves and wanted to see what he could do for

them.

The plantation facing on the Bayou is three

miles in length, but extends many miles back to

the swamps. My husband returned to it from the

rear, and none too soon, for as he entered from

the swamps the Federals were approaching

from Donaldsville, coming by the Bayou road

in front of the plantation. He called the negroes

around him and told them that when the

Federals took possession of the place they

would be given their freedom, but if they

wanted to go with him, he would take them to

Texas where he would give them work and treat

them as he had always done, but they would still

be slaves. In answer a chorus of voices

exclaimed, “Ole Massa, we’ll go with yo’.” Out

of several hundred slaves only fifteen young

half-grown boys remained on the place. My

husband then ordered all the wagons to be made

ready, the very large

ones which are used for hauling sugar-cane

from the fields to the mill, each requiring four

mules. In these he put the old women, young

children, and the sick; the women and those

who were able followed on foot. The negroes

were allowed to take some of their belongings

with them, as they placed great value upon their

personal possessions, and would have been

very unhappy at leaving them. Of this fact my

husband realized the importance, as he did not

wish them to become dissatisfied so as to

regret their decision to go with him. It was not

many hours after they went off that the

Federals entered the plantation from the front

and took possession of the place. The Federal

officers of the regiment occupied the dear old

house for several months before they

destroyed it. One of the officers fell in love

with a Creole girl living near the place. He told

her that they were going to destroy the house

and what they could not carry off they would

break up or burn. If there was anything she

would like to have he would gladly give it

to her. She asked for my beautiful silver

tea-kettle that she knew I valued greatly, also the

piano which was much prized. He sent them to

her. In a letter which I have just received from

her she writes me that she is keeping them for

me, and regrets that she did not ask for more,

as everything has been taken away, silver,

pictures, and many things that I have been

collecting for years, and with which I have very

dear associations. Oh! this awful war. When

will it end? How many innocent ones must

suffer for the ambition of the terrible

politicians. If only those who caused the war

had to suffer, it would be more just.

My husband’s account of his experience

during the hundreds of miles he traveled with

his slaves is really most extraordinary. They

were often very short of food and had many

hardships to endure, but not once did the slaves

falter or cease in their vigilant care and

consideration of him.

After a long and fatiguing day their only

sleeping-place would be on the ground, and

those who could would sleep in the wagons,

but the negroes never failed to make a

comfortable place for him. It is a strange sight

to see these trains of wagons and negroes

going through the country often with only one

member of their master’s family, and not

infrequently there would be only a woman who

most confidingly intrusted herself to the

protection and care of her slaves when

escaping from home and seeking safety

wherever one could find it. In most cases it

was in Texas.

A touching instance of this was a beautiful

young girl of eighteen years of age, who was

an orphan with only two brothers. When they

went off to join the Army she was left in

charge of the plantation. One of her brothers

was killed, the younger one returned home

badly wounded, just as the Federals were

approaching their plantation, and they were

making their escape from the rear, as my

husband had done, with her brother in a wagon

made into an impromptu ambulance by the

negroes, all of whom faithfully

followed her. To their care she intrusted

herself and the wounded boy, for he was not

more than twenty; for weeks they traveled

through a country not seeing a white person for

days. She gave touching accounts of how the

negroes would take turns in helping her nurse

the wounded boy, carrying him often in their

arms when the road would be so rough that

they feared the jolting of the wagon might

increase his sufferings, showing always the

greatest love and loyalty to the two young

creatures who felt no fear in their care. After

reaching Texas they became our neighbors,

and I learned to know how much they owed to

the care and devotion of these blacks during

this long journey. But this brave dear young

girl was called upon to face the additional

sorrow of seeing her brother gradually pass

away.

III

SHREVEPORT, LA.

Alas! there seems no rest for us, as again we

must start on our wanderings. This time Texas

is our destination. It is urgent that we should

get there as soon as possible; owing to the fact

that James has bought a ranch on which he

wishes to settle the negroes, it is important

that he should be there to organize the work in

establishing them.

We reached here yesterday, coming by boat

from Alexandria. It was a sad trip for us all, but

oh! most touchingly sad for dear Mrs. General

Taylor, who was put under my husband’s care

with her four children, two of them bright,

promising boys, both handsome and fine

specimens of health. The elder was named for

his grandfather, President Zachary Taylor, and

the other for his father, General Richard

Taylor, familiarly

known to his friends as

“Dick” Taylor

a gallant

soldier and a most charming man.

The second day out.

One of the boys showed symptoms of

scarlet fever, but before it was really known

what was the matter with him he died very

suddenly.

Two days later.

I have been all day with Mrs. Taylor. It is

marvelous, her courage and sweet resignation

to the will of God, as both of her darling boys

are dead. The younger died this morning. In the

midst of her own overwhelming sorrow she is

unselfishly thinking what a terrible grief it

would be to her husband who is with the army,

fighting gallantly in defense of our country.

The two little girls are a great comfort to their

mother, as they are very sweet and attractive

children.

A week later.

It is a great temptation to linger on here as

everyone has been most kind and hospitable,

sharing generously with us whatever they have.

It is an attractive little city with its many pretty

and comfortable houses, and as the weather is

very hot they seem delightfully cool and most

suitable for this part of the State.

The friends who have taken us in have large

and beautiful grounds surrounding their

houses, the gardens of which are full of the

greatest profusion and variety of flowers, with

some fine old trees. It all seems so peaceful

and quiet that it is hard to realize the dreadful

war raging not far from us, the beautiful and

happy homes that have been destroyed, the

brokenhearted men and women who are

wandering from place to place in search of

safety and peace. Oh! the horrors of war and

most dreadful of all, of civil war; brother

fighting against brother and families divided.

God grant that it may not last long is the prayer

that is in the hearts

of the suffering women in the North as well as

in the South.

James just told me that all the arrangements

for our trip are completed and that we start

to-morrow, going in our own carriages, taking

an extra wagon to carry our few possessions in

the way of clothes and provisions; also the

servants. It is with really great regret that I

leave our dear, good, kind friends and this

attractive place where I had rest and peace.

kaufman ranch, texas.

A month later.

We reached here yesterday, glad to get to

even this wooden shanty, which is to be our

home for the next few months, but one could

not call it luxurious in its appointments, for

last night we were awakened by the rain falling

in on us, so much so that we spent the greater

part of the night sitting up under umbrellas.

I meant to keep an account of our trip, but I

was generally so tired when we stopped

for the night that I really could not write. The

trip was monotonous, nothing very exciting

happened. We usually made an early start in

the morning, sometimes before sunrise, and

we were well repaid for doing so, as it was

often very beautiful, the sun rising over the

plains and the air deliciously cool at that hour

in the morning. Then at midday, we were

generally fortunate enough to camp by the side

of a clear running stream, giving us the chance

of a bath, which we found most refreshing, as

it was always very hot in the middle of the day.

The country was not particularly interesting,

some parts were made pretty and attractive by

the beautiful wild flowers, and the growth of

trees following the stream, but as a rule it was

monotonous, sometimes we could not even

see the sign of a house during the whole way.

When we reached one at night we were always

offered the hospitality of the place, and not

infrequently the house would be too small to

take us all in, so the men would sleep on the

balcony and the women

were given the beds; but I preferred the balcony

and fresh air. They offered most

generously to share with us whatever food they

had prepared for themselves, but unfortunately

the frying-pan was the one cooking utensil in

which all their food was cooked, so I took milk

and boiled eggs. These country people are very

simple and kind-hearted. Many of them have

had very tragic lives coming to this State from

all parts of the country, often for tragic

reasons. They welcome strangers, as in them

they feel a connecting link with the world

which they have left behind.

A month later.

Nothing has happened during these weary

weeks of anxiety that is worthy to be recorded

here. I fear I am allowing myself to get into a

most despondent state of mind, which is not

usual with me, but how can it be otherwise

when I am so anxious about Richard, who is a

prisoner on Johnson’s Island. He was

captured at the fall of Port Hudson. I

am indeed most grateful to have seen him, and

how merciful it was that I was permitted to

have those few moments with him before the

battle began and we were ordered off!

Now we have just heard that my son James

has been given command of the Second

Kentucky Regiment, having recovered from

the wound he received at Fort Donaldson.

Louis, too, is a captain in one of the Louisiana

regiments. My three boys! It is so sad!

Tuesday.

I have just written to General Grant, asking

him to do what he can for Richard for the sake

of old associations, for as boy and girl we

were much together, and I have always loved

him. The great soldier will never be to me

anything but the shy boy with a big, loving,

generous heart, and a simple nature. I feel sure

he will use his influence for Richard, his

cousin. What makes it so dreadful is that we

have no mail service. The post office is fifteen

miles away, and the letters are brought there by

any chance rider who may

be going through the country, passing that way,

and who will kindly take the letters from one

post office to another, leaving them at his

convenience. We have an occasional

excitement in an encounter with the much

dreaded tarantulas, but we get out of their way

as quickly as possible, for they are difficult to

kill, and the bite is generally fatal.

In spite of our efforts to make our wooden

shanty even habitable, we find it impossible. It

is not a question of money, for we have plenty,

but the necessary materials are not to be had at

any price. We are grateful for any distraction,

even the smallest incident is made much of. So

we enjoy the excitement of sending men on

horseback in every direction to the country

stores within twenty or thirty miles to hunt for

shoes, as we are all sadly in need of them. One

of the searchers came back very triumphant, as

he had found one pair in a country store twenty

miles away, but as they asked him seventy-five

dollars for them, he hesitated about bringing

the shoes; he was promptly sent back to fetch

them.

Great was the excitement when he returned

with the shoes. As they were of a small size we

all wished that our feet might not prove too

large! It was an anxious moment when our turn

came to try them on, but I am glad that they fit

one of the girls, whose pretty little feet made

her the Cinderella of the occasion.

Our only neighbor is the young girl that I

spoke of before, who came here alone with her

wounded brother.

TOWN OF FAIRFIELD.

A month later.

I opened you, my dear little book, to pour

out the despairing cry of a broken-hearted

mother. Since I last wrote, I have suffered too

much to be able to record it. Now I feel that I

must, that perhaps it will help me, and I want to

write an account of what my brave little

daughter has done.

James was away. He had come here on

business, when someone riding through the

country brought a letter to the ranch, as he

had been well paid to deliver it. The letter was

from an officer of James’ regiment. He wrote

describing my brave boy’s death on September

the 19th, at the battle of Chickamauga; how he

was killed at the head of his regiment charging

a battery. When I realized what it meant, I

became unconscious, and passed from one

fainting spell into another, and then into a state

of torpor. The only person with me was my

little daughter. She realized that I must have the

comfort and help of being with my husband,

also that I was in a very desperate mental

condition. Her first thought was to get me here.

The ranch is twenty miles away. My husband

had the carriage, so there was nothing to bring

me in but the buggy, and she was unwilling to

send me with one of the negroes, owing to my

terrible mental condition. But even children in

such times imbibe the spirit of fearlessness. So

she, losing all sense of danger, started with me

lying by her side in a helpless condition. She

drove through the dark night, going through

forests, crossing

streams that were swollen by the recent rains,

sometimes over the prairie, where the howls of

the prairie dogs seemed to bring them close

upon us. On, on, on she drove; the little white

face peering eagerly through the darkness for

the first glimpse of the dawn, and shortly after

it appeared, she brought me safely to the house

where my husband was staying. Poor little one!

They told me she was so exhausted by the

fatigue and excitement of the night that she fell

asleep at once upon entering the house. There

were many days that they despaired of my life,

but being able to have the best medical

attention, and with the tender nursing and care

of my husband, I am now able to be about, but,

oh, so anxious about Louis and Richard. I am

most thankful that my youngest son Charles,

who, owing to his delicate health, was

compelled to remain North, has thus been

removed from danger.

FAIRFIELD.

Later on.

Poor James is in a most terrible state of

mind, as he has heard that one of his partners in

New York, fearing that our home there may be

confiscated, has sold the house with the

furniture and all it contains at auction.

Intending this to be the home of our old age, we

had spared no expense in making it luxurious in

all its appointments. It is very hard to think that

all the beautiful works of art which we had been

years collecting, old pictures, and rare

manuscripts have all been sold. My husband

does not believe that it was necessary. He

thinks Mr. Adams became panic-stricken, and

did it without consulting his older and wiser

friends in New York.

This has made him very anxious about other

valuable property and large interests which he

has in the North, and has made him decide to

start for England at once, where he could get

into communication with his friends. It will be

several days before we can get sufficient

provisions together and make other

necessary preparations. We must travel in the

same way as we came here, at least as far as

San Antonio.

IV

SAN ANTONIO.

Nothing could equal our joy at reaching this

haven of rest. Never did a place seem more

enchanting and offer to the weary travelers so

much that was enticing and refreshing. After

our long and fatiguing journey of weeks, when

during the latter part of it we slept nearly

always on the ground with nothing but a blanket

under us, we truly appreciated the luxury of a

bed.

The place itself is fascinating and

picturesque, with many of the old Spanish

houses still remaining. The river running

through parts of the city, with gardens leading

down to it in the rear of the dwellinghouses,

makes it most attractive. These gardens are

well kept and have a great variety of flowers

and plants peculiar to this latitude.

We are overwhelmed with the kindness

and hospitality of the people. Mr. Hunton

and

his wife, with whom we are staying, are

charming and delightful. They are doing

everything to make our stay an enjoyable one

for us, but what we are most in need of is rest,

for we are all worn out by the trip. We also

need to replenish our wardrobe, as we can buy

some materials here and it is the first time that

we have been able to do so since we emptied

the country store on Bayou Plaquemine, more

than a year ago!

We hear that the Federal troops are in

possession of Brownsville. This will make it

necessary for us to change our plan of route,

and instead of going South through Texas, we

must cross into Mexico at Laredo. This will

take us across the plains of Texas, where there

is danger of the Indians, for lately they have

been making raids on the wagons loaded with

bales of cotton passing that way, killing the

drivers and carrying off the cotton. Now we

must wait here until we can get together a

sufficient number of men as a protection in

case of an encounter with the Indians.

I regret the necessity of giving up our own

carriages and the fact that we must go in public

stages, the old-fashioned ones, carrying nine

persons; three on the back seat, three in the

middle with only a strap at their backs, and

three with their backs to the horses. As the

weather is hot, we are buying only the simplest

thin materials for our dresses and other

garments. They tell us that we shall have to

leave them en route, for to have them washed

would be impossible.

Our supply of provisions is to be limited to

smoked beef and corn bread and tea, if we are

lucky enough to get, first, the water to boil, and

then the wood to make a fire, as alcohol is out

of the question. Our friends are trying to

persuade me not to go with James, and

reproach him for being willing to expose us to

such great danger. They little know how

impossible it would be for me to stay, that

nothing could separate me from my husband

under the circumstances. These are heroic

times! They call for heroic action on the part

of the women as well as the men.

We must not know what fear means. I have

long since driven all sense of it from my heart.

It does not exist for me, and the same is the

case with our daughter since we received our

baptism of fire at Port Hudson.

The party is gradually being gathered

together. To-day James tells me that a

Scotchman, two Irishmen, a Swede, three or

four Englishmen, also some Texans are going!

There are sixteen in all. The necessary number

must be eighteen, so we have to wait for two

more to be found. They will all be well armed

and carry a good supply of ammunition. It all

seems very exciting, but they are gradually

reducing our allowance of luggage to a most

distressingly small amount. All spare space

must be given up to carrying fodder and food

for the mules. Our allowance is one trunk for

three of us, as it must be carried at the back of

the stage. We have our handbags, a pillow, and

a blanket to sleep on, for the chances are that

we shall seldom find a house or shelter of any

kind.

With this trip in prospect we have so enjoyed

our rest here. The house that we are

staying in is most comfortable and luxurious in

many respects. I think it seems doubly so to us

after the many trying experiences we have had

since we left our own dear old home on the

plantation. My dear little companion, I am

afraid that I shall not be able to write you up en

route, as traveling all day in the fresh air makes

me very sleepy when night comes on, and then

I am often very tired, though fortunately I am

strong and well.

In a few minutes we are off; the party is

complete in number and the awful stagecoach

is at the door, awaiting our party of four and

our few possessions. It does not take long to

store them away.

Several weeks later.

This is the first time that I have felt like

writing since we left San Antonio, more than

two weeks ago. Indeed, until the night before

last I have had nothing of special interest to

record. The days have succeeded each

other with the same routine, only varied by

more or less of hardship, fatigue, and lack of

food and water. The latter is the most terrible,

for at times we had to go many hours before

reaching a place where we could get water fit

to drink.

The weather is hot, the roads are dusty, so we

have suffered intensely at times from the most

parching thirst. When we were able to find

good drinking water we filled every available

bucket, bottle, or anything in which we could

carry it. The tin buckets and bottles we have

covered with flannel, and they are hanging

outside of the coach so as to catch any breath

of wind that there may be, as this is our only

method of cooling the water.

We always make a very early start so as to

get the benefit of the freshness of the

morning, stopping for several hours in the

middle of the day to rest the mules and

ourselves. I cannot say that we look forward

with any eagerness to our midday meal unless

by chance we have passed through a village

and been able to buy some eggs and milk. But

as we are a large party, whatever we are

fortunate enough to get has to be divided

among so many that it makes each portion very

small, but we were grateful for any change

from dried beef and corn bread.

I cannot say that we always get our midday

rest under the most favorable conditions, as

frequently the only shade we can find is in the

shade of the stage-coaches, not a tree or

vegetation of any kind being in sight. The first

five nights after leaving San Antonio were

beautifully clear, so mild that we could sleep

most comfortably out of doors. Only one night

did we have rain. Then we had to sleep as best

we could, literally sitting up all night in the

coaches. My daughter gave a very amusing

account of how she had spent the night,

refusing to allow an Irishman on one side of

her and a Scotchman on the other to make a

pillow of her soft young shoulders. Her

remonstrances at first called forth abject

apologies on their part, but as the night wore

on, it became a war of defense on her part and

perfectly unconscious recklessness on theirs.

As they are good friends of hers and

exceedingly nice men, they all had a hearty

laugh over it next morning.

The life that we are living draws us very

closely together, so much so that we have

become like one large family. I am glad to say

there is not a disagreeable or objectionable

member. It is the more remarkable as we are of

different nationalities and walks of life,

therefore, have different tastes and habits. But

what unites us in a strange bond of friendship

and makes us equals, is the sharing of hardships

and the threatening danger that we have in

common. This was forcibly shown the night

before last, when we had such an alarming

experience which brought out the true mettle

of all the members of our party.

Always before settling down for the night we

sent out scouts to see if there were any Indians

near enough to us to disturb our peace during

the night. We had that day

passed scalps by the roadside, and there were

evidences of there having recently been a

conflict between the Indians and a number of

those who accompanied a train of cotton

wagons. They had undoubtedly been killed and

the cotton carried off by the Indians. We

traveled far into the night until our mules

became so exhausted that we had to stop on

their account. We hoped to get away from a

neighborhood where there might still be some

Indians lurking about. Our worst fears were

confirmed by the scouts returning with the

account of a camp of Indians not far from us.

We could go no farther, our mules were

exhausted, so there was nothing for us to do but

to make our means of defense as strong as

possible. I cannot say too much in praise of the

brave and gallant men who were to be our

defenders. To add to the difficulties of the

situation the night was dark, so that all our

preparations had to be made in silence and by

starlight, no one speaking above a whisper. No

fires could be made for fear of attracting the

notice of

the much-dreaded Indians. The stars were the

only witnesses of the solemn and hasty means

of defense made by this little group of weary

travelers. The only other women in the party

were Clarice, Belle, my daughter-in-law, and

her little girl. We were to stay in the center of

the camp, the stage-coaches forming a

barricade around us. There was a thick growth

of underbrush not far from where we camped;

this was cut and brought in large quantities and

arranged in piles so as to form an outside

barricade behind which our defenders stood.

We also hoped it would serve to conceal from

those who were attacking us how few we were

in number. Belle and I were to have charge of

the extra ammunition, giving it to the men

when they needed it. After all possible means

of defense had been completed, we said our

prayers and waited silently and motionless,

feeling sure that the Indians must know how

near we were to them. It was a night of

inexpressible horror. What we suffered is

beyond description. When the first break of

dawn

came we were a weary, exhausted little band,

and on looking at each other were shocked to

find every face around us showing great lines

and traces of the anxiety and suffering of the

night. When we realized that we had passed

safely through it, we all knelt, and from every

heart went up a prayer of great thankfulness for

what seemed to us a miraculous escape. As the

day wore on we took turns in resting, for we

were not at all sure but what we might still hear

from the neighboring camp, and about one

o’clock we did, but in a very different way from

what we had expected.

One of their scouts came over to our camp,

and to our surprise and joy we found that those

whom we had taken for Indians were the drivers

and scouts of a train of cotton wagons. Their

relief on finding out about us was as great as

ours, for they too had stayed up all night under

arms, supposing our camp to be one of Indians,

and expecting an attack from us!

After an evening of rejoicing we took a

good rest, and started next day for Laredo, our

next destination.

LAREDO.

We reached here late last evening with the

hope of finding some decent place where we

might be moderately comfortable and rest for

a few days before starting for Mexico.

Alas! Alas! Our hopes soon vanished, and

great was our disappointment when we saw the

only accommodation that we could get. There

is no hotel and the town is crowded, not a spare

bed to be found. We drove around the place,

stopped before every decent-looking house,

my husband offering a large sum of money if

they would only take us in. We were always

met with the same answer, and were very

politely informed that nothing would give them

more pleasure than to have us, but they really

had not a spare bed! Finally, in despair, we had

to take the only room which we could get, it is

in an adobe house. The floor is simply of earth.

The

bunks in which we sleep are like those of

immigrants on board transport ships. On each

side of the room are six berths in a row. One side

is supposed to be for the men and the other for

the women, the latter having a thin cotton

curtain in front of them. Not a chair or piece of

furniture of any kind, nor the tiniest bit of a

looking-glass! For all toilet purposes we have

to go to the public fountain in the patio! We

have succeeded after a great deal of coaxing

and bribing in getting our landlady to partition

off a corner of the patio, and after searching in

the town we finally found a wooden wash-tub,

which we put in this reserved corner and that

serves as our bathtub. We take our baths under

some difficulties, as the curiosity of the

smaller members of the family and their little

friends is so great that we have to place

someone on guard to protect us from the

invasion of curious eyes.

We are feeling really very sad at parting

with our friends with whom we have shared so

many trials, difficulties, and dangers, which

has cemented a strong and lasting friendship

between us, even if we never meet again.

We are buying a small supply of provisions

that can be easily carried. It is, however, a

great relief to us to hear that in the Mexican

towns we can always get a good cup of

chocolate and fresh eggs. Now it is a greater

joy that we can have our own carriages and

in every way be more comfortable. Our

party will consist of ourselves and only two

others, both of them very agreeable and good

traveling companions.

Our week here has done us good

notwithstanding that we have been so very

uncomfortable in our lodgings, but the food

has been good. Fortunately we all like Mexican

cooking. I am particularly fond of their

frijoles.

Just a line before we start, for I know that I

shall not feel like writing en route. It is a most

beautiful morning and we are all starting off in

hopeful spirits.

A few days later.

The days have passed by quickly and the trip

so far has not been disagreeable, although

not interesting as the country is flat and dusty.

The Mexican towns are dirty and most

monotonous, so that we have preferred

sleeping on the ground away from the villages.

Two days later.

While it is fresh in my mind I must write

down the remarkable experience which we had

yesterday. It was late in the afternoon, we had

driven all day without seeing a habitation of any

kind, or heard a sound, or seen any living thing,

when we suddenly heard in the distance a weird

sound, and as we approached the direction from

which it came, we could distinguish human

voices, singing with great fervor a religious

chant. Then there appeared from behind the

underbrush a low adobe hut, and from this hut

came the voices. My daughter begged to be

allowed to enter the hut. Her father, who is ever

ready to grant any wish of hers, the more so if

it shows

courage, consented, thinking that in this

instance it might be an act of devotion. We

stopped the carriage some distance away,

fearing that the noise of our approach might

disturb those who were attending some

religious rite. As the girl disappeared over the

threshold, we all thought how ethereal she

looked, more like a vision than a reality in her

simple white muslin. She is very fair, her long

hair is golden, falling in curls down her back,

then her beautiful eyes are a heavenly blue! As

she entered the hut we all held our breath. I was

inclined to be provoked with her father for

letting her go, for though tall for her age she is

nothing more than a child. After waiting some

time, I became anxious, and asked one of the

men of the party, who speaks Spanish, to go

after her. When they joined us we saw that they

were both very much moved and overcome by

something that had happened. When we were

able to be alone with Mr. Cushing he told us of

the very remarkable scene that he had witnessed

on entering the hut. When the

child first went into the hut about twenty dark

swarthy Catholic Indians were there, down on

their knees, praying with extraordinary fervor

to the Virgin. The child, feeling no fear, went to

the middle of the room before they noticed

her, and when they looked up and saw her, it

happened that just at that moment a ray of

sunshine fell upon her, and as they had never

seen so fair a person before, they took her for a

vision come to them in answer to their prayer.

They crawled on hands and knees to her, kissing

the hem of her garment. The child put her

hands on their black swarthy heads and prayed

that some day God would allow her to devote

her life to the uplifting of the poor and

suffering ones of this world, such as these. It

has evidently made a great impression upon

her, and I pray with all my heart that her prayer

may be answered, and that she will feel the

responsibility that all good women should feel

in the use of the great power that is given to us

to be an influence for good in a woman’s way

on all who came in contact with us.

V

We had hardly recovered from the excitement

of the visit to the hut, when three days

afterwards we met on the road a very handsome

young Mexican, wearing the picturesque

costume usually worn by the swells of the

country, consisting of a light-colored cloth

suit, with trousers rather large at the feet,

and many rows of buttons down the side; the

jacket had also brass buttons and was elaborately

embroidered. With this they wear the

national sombrero. His saddle and bridle

were richly ornamented with gold and silver,

and the saddle-blanket heavily embroidered in

gold and silver to match. Some time after he

had passed us, we saw him returning at full

gallop with something blue in his hand which

he waved at us. We stopped, and when he

drew his horse up by the side of the carriage

he pressed the blue veil that he held in his

hand, first to his lips and then to his heart, and

with a profound bow handed it to Clarice,

looking at her with the most intense

admiration. She was so overjoyed at recovering

her veil, that she was very profuse in her

thanks — and not knowing where to stop for the

night, we asked his advice. As it was late in the

afternoon, he advised us not to go on much

further; as a mile or two beyond was the gate to

his ranch he begged that we would accept of his

hospitality for the night, or for many days,

weeks or months, saying that every moment

that we honored his home with our presence

would be to him a joy and happiness beyond

words.

We declined his most pressing and generous

invitation with many thanks and proceeded on

our way. We passed his gate, and drove some

distance further on; as the road was in good

condition and it was a beautiful night, we were

glad of the chance to drive as late as possible.

We found a good place, and settled ourselves

for the night; being very tired we were all

sleeping when the noise of

approaching horses awoke us. It was our young

Mexican; he had two carriages, each drawn by

four horses, and had come to fetch us to a

dance that he was giving to the beautiful

Se�orita. While very profuse in his apologies

he was very earnest in his determination to

have us go with him. My husband finally

consented to let the young people go, as Mr.

Cushing was willing to go with them. They

returned as the day was dawning, and gave a

most enthusiastic account of the house, the

great courtesy and politeness of their host and

of his mother, whom they described as a most

charming woman, who received them very

cordially, as did all the girls and young men. It

must have been a most beautiful entertainment,

as the patio (which all Mexican houses have)

was illuminated, and with all the flowers and

wonderful plants, was an enchanting sight.

If Clarice had accepted all the things the

young Mexican offered her (including his heart

and his hand) she would have found it difficult

to have brought them with her.

He begged permission to write to her, and

assured her that he would never forget her — and

would go to Paris to see her.

MATAMORAS.

The days following the dance were

uneventful, nothing happening of any interest

until we reached here, when it was with a great

sigh of relief that we entered this very

unpromising town, for it meant to us the end of

our wearisome and long journey. We had our

usual experience of driving around in search of

rooms, and were feeling very discouraged as

every available place was full, when my husband

met someone whom he had known in New

Orleans. On hearing of our difficulties, he

kindly offered to give us the use of a room at

the back of a shop, where his clerks slept in

cots such as the soldiers use. When my husband

asked him, “What will they do?” “Oh,” he said,

“they can sleep on the counters of the shop.” We

were not very cordially received by these young

men when they were told that they had to

move out and give us the use of their not very

luxurious quarters, though these were little

better than the shop would be. The partition

between the two rooms is only of paper, not

meeting the wall on either side by several

inches. This makes it rather difficult as the

occupants of both rooms must avoid the sides

while dressing. We have the cots as close

together as possible in the middle of the room,

and the girls dress standing on theirs. All

conversation must be scrupulously avoided; we

were constantly calling out to our neighbors,

warning them of our near presence, which they

occasionally forgot.

Our baths we take in the patio; it is not quite

such a struggle with difficulties as we had in

Lareda. For among these. young men there are

two or three Englishmen who have made a very

decent bathroom on the side of the patio,

where they can have their “tub” very

comfortably, and they have graciously given us

the use of it during certain hours of the day.

We have reached

that condition of mind that nothing disturbs us

very much; fortunately, most of the party are

young; they only see fun in it, and I

unconsciously imbibe some of their youthful

spirits! We take our meals at a most excellent

restaurant where our long privation from good

food enables us to appreciate and do justice to

the well-prepared dishes by a first-class French

chef. We have been so long removed from all

contact with the outside world that to be once

more in touch with it, and hear of the events

that have taken place, makes me feel as though I

had been asleep, and all the terrible scenes and

suffering that I have gone through might be

some hideous nightmare. Oh! if I could only

awake and find it so. My darling boy alive,

Richard out of prison, and feel that I could go

back to our dear old home, with our loved ones

around us once more.

But I must not allow myself to dwell on my

own sorrows, for it unnerves me and unfits me

for my duty to others — my husband needs all

the help and comfort that I can

give him, my other children all the love and

devotion that I can bestow upon them. Should it

not be our first duty as well as our pleasure to

make those we love and all those we come in

contact with happy? With all my sorrows, I am

thankful that one distress has been spared me,

and that is the feeling of remorse, and I pray

God that it may never enter into my life.

It seems to me that it must be the most

terrible of all sufferings to know that we have

neglected or failed in our duty to some loved

one who has been taken from us. What a

terrible memory it would be to have caused

them pain or have been unkind and unjust to

them when they depended upon us for their

happiness. How dreadful to have turned away

from them seeking our own selfish pleasures,

forgetting how they need our love and

sympathy — anything but that in my life. There

is no sacrifice too great that I would not gladly

make for those I love, so that when God calls