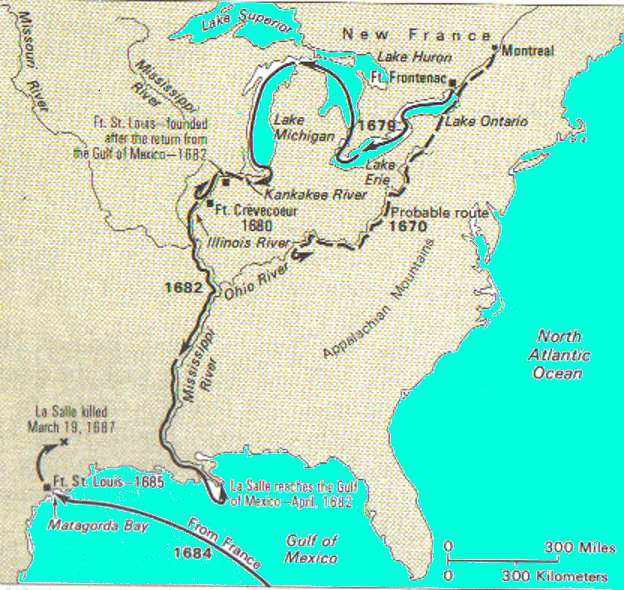

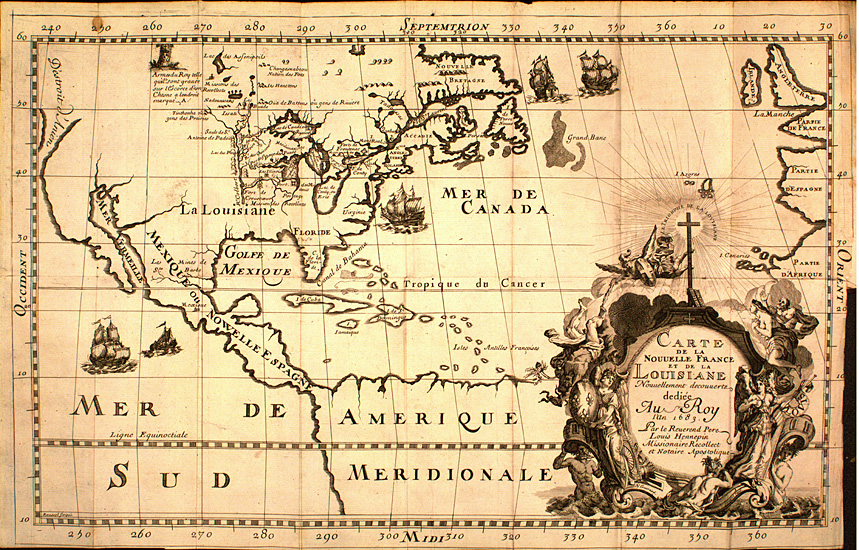

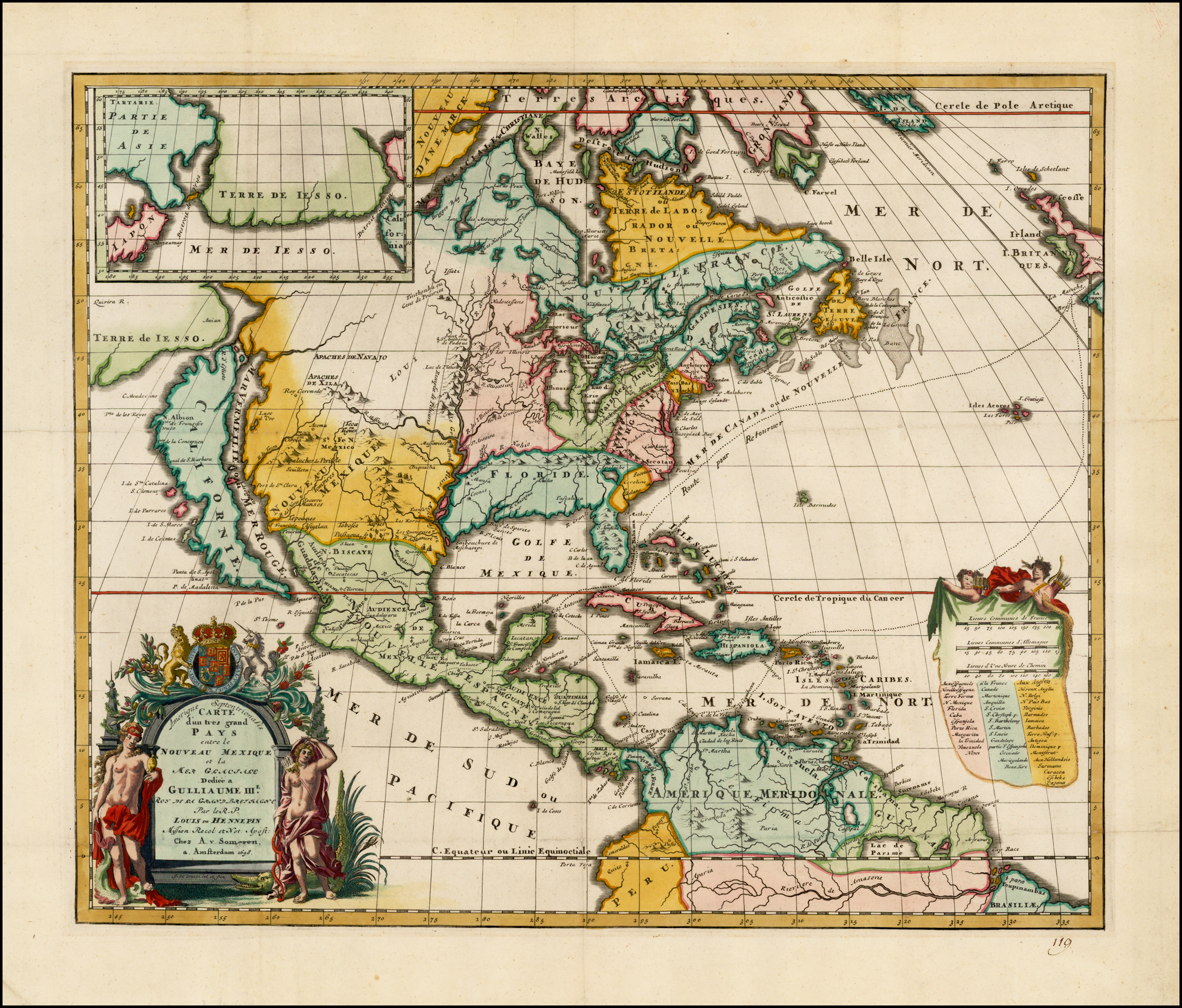

AT the time when M. de la Salle was preparing for his last voyage

into North America,

I happened

to be at Rouen, the place where he and I

were both born, being returned from the army, where I had served sixteen

or seventeen years.

The reputation gained by M. de la Salle, the greatness of his

undertaking, the natural curiosity which all men are possessed with, and

my acquaintance with his kindred, and with several of the inhabitants of

that city, who were to bear him company, easily prevailed with me to make

one of the number, and I was admitted as a volunteer.

Our rendezvous was appointed at Rochelle, where we were to embark.

MM. Cavelier, the one brother, the other nephew to M. de la Salle, MM.

Chedeville, Planteroze, Thibault, Ory, some others, and I, repaired

thither in July, 1684.

M. de la Salle having provided all things necessary for his voyage,

surmounted all the difficulties laid in his way by several ill-minded

persons, and received his orders from M. Arnoult, the Intendant at

Rochelle, pursuant to those he had received from the king, we sailed 01

the 24th of July, 1684, being twenty.four vessels, four of them for our

voyage, and the others for the islands and Canada.

The four vessels appointed for M. de la Salle’s enterprise, had on

board about two hundred and eighty persons, including the crews; of which

number there were one hundred soldiers, with their officers; one Talon,

with his Canada family, about thirty volunteers, some young women, and the

rest hired people and workmen of all sorts, requisite for making of a

settlement.

The first of the four vessels was a man-of-war, called Le Joly, of

about thirty-six or forty-guns, commanded by M. de Beaujeu, on which M. de

la Salle, his brother the priest, two Recollet friars, MM. Dainmaville and

Chedeville, priests, and I embarked. The next was a little frigate,

carrying six guns, which the king had given to M. de la Salle, commanded

by two masters; a flyboat of about three hundred tons burden, belonging to

the Sieur Massiot, merchant at Rochelle, commanded by the Sieur Aigron,

and laden with all the effects M. de la Salle had thought necessary for

his settlement, and a small ketch, on which M. de la Salle had embarked

thirty tons of ammunition, and some commodities designed for St. Domingo.

All the fleet, being under the command of M. de Beaujeu, was ordered

to keep together as far as Cape Finisterre, whence each was to follow his

own course; but this was prevented by an unexpected accident. We were

come into 45° 23′ of north latitude, and about 50 leagues from Rochelle,

when the bowsprit of our ship, the Joly, on a sudden broke short, which

obliged us to strike all our other sails, and cut all the rigging the

broken bowsprit hung by.

Every man reflected on this accident according to his inclination.

Some were of opinion it was a contrivance; and it was debated in council,

whether we should proceed to Portugal, or return to Rochelle or Rochefort;

but the latter resolution prevailed. The other ships designed for the

islands and Canada, parted from us, and held on their course. We made

back for the river of Rochefort, whither the other three vessels followed

us, and a boat was sent in to acquaint the Intendant with this accident.

The boat returned some hours after, towing along a bowsprit, which was

soon set in its place, and after M. de la Salle had conferred with the

Intendant, he left that place on the first of August, 1684.

We sailed again, steering W. and by S., and on the 8th of the same

month weathered Cape Finisterre, which is in 43° of north latitude,

without meeting anything remarkable. The 12th, we were in the latitude of

Lisbon, or about 39 north. The 16th, we were in 36, the latitude of the

Straits, and on the 20th, discovered the island of Madeira, which is in

32°, and where M. de Beaujeu

proposed to M. de la Salle to anchor, and take in water and some

refreshments.

M. de la Salle was not of that mind, on account that we had been but

twenty- one days from France, had sufficient store of water, ought to have

taken aboard refreshments enough, and it would be a loss of eight or ten

days to no purpose; besides, that our enterprise required secresy, whereas

the Spaniards might get some information, by means of the people of that

island, which was not agreeably to the King’s intention.

This answer was not acceptable to M. de Beaujeu, or the other

officers, nor even to the ship’s crew, who muttered at it very much; and

it went so far, that a passenger called Paget, a Huguenot of Rochelle, had

the insolence to talk to M. de la Salle in a very passionate and

disrespectful manner, so that he was fain to make his complaint to M. de

Beaujeu, and to ask of him whether he had given any encouragement to such

a fellow to talk to him after that manner. M. de Beaujeu made him no

satisfaction. These misunderstandings, with some others which happened

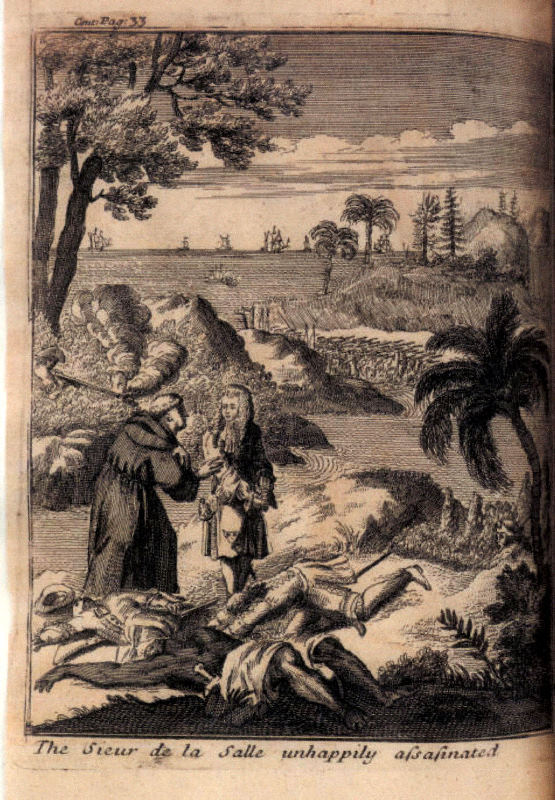

before, being no way advantageous to his majesty’s service, laid the

foundation of those tragical events which afterwards put an unhappy end to

M. de la Salle’s life and undertaking, and occasioned our ruin.

However, it was resolved not to come to an anchor at that island,

whereupon M. de Beaujeu said, that since it was so, we should put in

nowhere but at the island of St. Domingo. We held on our course,

weathered the island of Madeira, and began to see those little flying

fishes, which, to escape the dorados, or gilt-heads, that pursue them,

leap out of the water, take a little flight of about a pistol shot, and

then fall again into the sea, but very often into ships, as they are

sailing by. That fish is about as big as a herring, and very good to eat.

On the 24th we came into the trade wind, which continually blows from

east to west, and is therefore called by some authors ventus subsolanus,

because it follows the motion of the sun. The 28th, we were in 27° 44′ of

north latitude, and in 344° of longitude. The 30th, we had a storm, which

continued violent for two days, but being right astern of us, we only lost

sight of the ketch, for want of good steering, but she joined us again in

a few days after.

The 6th of September, we were under the tropic of Cancer, in 23° 30′

of north latitude, and 319° of longitude. There M. de la Salle’s

obstructing the ceremony the sailors call ducking, gave them occasion to

mutter again, and rendered himself privately odious. So

many have given an account of the nature of that folly, that it would be

needless to repeat it here; it may suffice to say, that there are three

things to authorize it:

- Custom;

- The oath administered to those who

are ducked, which is to this effect, that they will not permit any to pass

the tropics or the line, without obliging them to the same ceremony; and

- which is the most prevailing argument, the interest accruing to the

sailors upon that occasion, by the refreshments, liquors, or money, given

them by the passengers, to be excused from that ceremony.

M. de la Salle being informed that all things were preparing for that

impertinent ceremony of ducking, and that a tub full of water was ready on

the deck (the French duck in a great cask of water, the English in the

sea, letting down the person at the yard-arm), sent word that he would not

allow such as were under his command to be subject to that folly, which

being told to M. de Beaujeu, he forbid putting it in execution, to the

great dissatisfaction of the inferior officers and sailors, who expected a

considerable sum of money and quantity of refreshments, or liquors,

because there were many persons to duck, and all the blame was laid upon

M. de la Salle.

On the 11th of September we were in the latitude of the island of St.

Domingo, or Hispaniola, being 20° north, and the longitude of 320°. We

steered our course west, but the wind flatting, the ensuing calm quite

stopped our way. That same day M. Dainmaville, the priest, went aboard

the bark La Belle, to administer the sacraments to a gunner, who died a

few days after. M. de la Salle went to see him, and I bore him company.

The 21st, the ketch, which we had before lost sight of, joined us

again; and some complaints being made to M. de la Salle, by several

private persons who were aboard the flyboat, he ordered me to go thither

to accommodate those differences, which were occasioned only by some

jealousies among them.

The 16th, we sailed by the island Sombrero, and the 18th had hard

blowing weather, which made us apprehensive of a hurricane. The foul

weather lasted two days, during which time we kept under a main course,

and lost sight of the other vessels.

A council was called aboard our ship, the Joly, to consider whether

we should lie by for the others, or hold on our course, and it was

resolved that, considering our water began to fall short, and there were

above five persons sick aboard, of which number M. de la Salle and the

surgeon were, we should make all the sail we could, to reach the

first port of the island Hispaniola, being that called Port de Paix, or

Port Peace, which resolution was accordingly registered.

The 20th we discovered the first land of Hispaniola, being Cape

Samana, lying in 19° of north latitude, and of longitude 308°. The 25th

we should have put into Port de Paix, as had been concerted, and it was

not only the most convenient place for us to get refreshments, but also

the residence of M. de Cussy, Governor of the island of Tortuga, who knew

that M. de la Salle carried particular orders for him to furnish such

necessaries as he stood in need of.

Notwithstanding these cogent reasons, M. de Beaujeu was positive to

pass further on in the night, weathering the island of Tortuga, which is

some leagues distant from Port de Paix and the coast of Hispaniola. He

also passed Cape St. Nicolas, and the 26th of the said month we put into

the bay of Jaguana, coasting the island of Guanabo, which is in the middle

of that great bay or gulf, and in conclusion, on the 27th, we arrived at

Petit Gouave, having spent 58 days on our passage from the port of Chef de

Bois, near Rochelle.

This change of the place for our little squadron to put into, for

which no reason could be given, proved very disadvantageous; and it will

hereafter appear, as I have before observed, that those misunderstandings

among the officers insensibly drew on the causes from whence our

misfortune proceeded.

As soon as we had dropped anchor, a

piragua,

or great sort of canoe,

came out from the place, with twenty men, to know who we were, and hailed

us. Being informed that we were French, they acquainted us that M. de

Cussy was at Port de Paix, with the Marquis de St. Laurent,

Lieutenant-General of the American Islands, and M. Begon, the Intendant,

which very much troubled M. de la Salle, as having affairs of the utmost

consequence to concert with them; but there was no remedy, and he was

obliged to bear it with patience.

The next day, being the 28th, we sang Te Deum, in thanksgiving for

our prosperous passage. M. de la Salle being somewhat recovered of his

indisposition, went ashore with several of the gentlemen of his retinue,

to buy some refreshments for the sick, and to find means to send notice of

his arrival to MM. de St. Laurent, De Cussy, and Begon, and signify to

them how much he was concerned that we had not put into Port de Paix. He

wrote particularly to M. de Cussy, to desire he would come to him, if

possible, that he might be of assistance to him, and take the necessary

measures for rendering his enterprise successful, that it might prove to

the King’s honor and service.

In the meantime, the sick suffering very much aboard the ships by

reason of the heat, and their being too close together, the soldiers were

put ashore, on a little island, near Petit Gouaves, which is the usual

burial-place of the people of the pretended reformed religion, where they

had fresh provisions, and bread baked on purpose, distributed to them. As

for the sick, I was ordered by M. de la Salle to provide a house for them,

whither they were carried, with the surgeons, and supplied with all that

was requisite for them.

Some days after, M. de la Salle fell dangerously ill; most of his

family were also sick. A violent fever, attended with lightheadedness,

brought him almost to extremity. The posture of his affairs, want of

money, and the weight of a mighty enterprise, without knowing whom to

trust with the execution of it, made him still more sick in mind than he

was in his body, and yet his patience and resolution surmounted all those

difficulties. He pitched upon M. le Gros and me to act for him, caused

some commodities he had aboard the ships to be sold, to raise money; and

through our care, and the excellent constitution of his body, he recovered

health.

Whilst he was in that condition, two of our ships, which had been

separated from us on the 18th of September, by the stormy winds, arrived

at Petit Gouave on the 2d of October. The joy conceived on account of

their arrival, was much allayed by the news they brought of the loss of

the ketch, taken by two Spanish piraguas; and that loss was the more

grievous, because that vessel was laden with provisions, ammunition,

utensils, and proper tools for the settling of our new colonies; a

misfortune which would not have happened, had M. de Beaujeu put into Port

de Paix, and MM. de St. Laurent, De Cussy, and Begon, who arrived at the

same time, to see M. de la Salle, did not spare to signify as much to him,

and to complain of that miscarriage.

M. de la Salle being recovered, had several conferences with these

gentlemen, relating to his voyage. A consult of pilots was called to

resolve where we should touch before we came upon the coast of America,

and it was resolved to steer directly for the western point of the Island

of Cuba, or for Cape St. Antony, distant about 300 leagues from

Hispaniola, there to expect the proper season, and a fair wind to enter

the gulf or bay, which is but two hundred leagues over.

The next care was to lay in store of other provisions, in the room of

those which were lost, and M. de la Salle was the more pressing for us to

embark, because most of his men deserted, or were debauched by the

inhabitants of the place; and the vessel called L’Aimable,

being the worst sailer of our little squadron, it was resolved that she

should carry the light, and the others to follow it. M. de la Salle, M.

Cavelier, his brother, the Fathers Zenobrius and Anastasius, both

Recollets, M. Chedeville, and I, embarked on the said Aimable, and all

sailed the 25th of November.

We met with some calms and some violent winds, which, nevertheless,

carried us in sight of the island of Cuba on the 30th of the same month,

and it then bore from us N. W. There we altered our course and steered W.

and by N. The 31st, the weather being somewhat close, we lost sight of

that island, then stood W. N. W., and the sky clearing up, made an

observation at noon, and found we were in 19° 45′ of north latitude; by

which we judged that the currents had carried us off to sea from the

island of Cuba.

On the first of December we discovered the island of Cayman. The 2d

we steered N. W. and by W. in order to come up with the island of Cuba, in

the northern latitude of 20° 32′. The 3d we discovered the little island

of Pines, lying close to Cuba. The 4th, we weathered a point of that

island, and the wind growing scant, were forced to ply upon a bowline, and

make several trips till the 5th, at night, when we anchored in a creek, in

15 fathom water, and continued there till the 8th.

During that short stay, M. de la Salle went ashore with several

gentlemen of his retinue on the island of Pines, shot an alligator dead,

and returning aboard, perceived he had lost two of his volunteers, who had

wandered into the woods, and perhaps lost their way. We fired several

musket shots to call them, which they did not hear, and I was ordered to

expect them ashore, with 30 musqueteers to attend me. They returned the

next morning with much trouble.

In the meantime our soldiers, who had good stomachs, boiled and eat

the alligator M. de la Salle had killed. The flesh of it was white, and

had a taste of musk, for which reason I could not eat it. One of our

hunters killed a wild swine, which the inhabitants of those islands call

maron. There are of them in the island of St. Domingo, or Hispaniola. They

are of the breed of those the Spaniards left in the islands when they

first discovered them, and run wild in the woods. I sent it to M. de la

Salle, who presented the one-half to M. de Beaujeu.

That island is all over very thick wooded, the trees being of several

sorts, and some of them bear a fruit resembling the acorn, but harder.

There are abundance of parrots, larger than those at Petit Gouave, a great

number of turtle doves and other birds, and a sort of creatures

resembling a rat, but as big as a cat, their hair reddish. Our men killed

many of them and fed heartily on them, as they did on a good quantity of

fish, wherewith that coast abounds.

We embarked again as soon as the two men who had strayed were

returned, and on the 8th, being the Feast of the Conception of the Blessed

Virgin, sailed in the morning, after having heard mass, and the wind

shifting, were forced to steer several courses. The 9th we discovered

Cape Corrientes, of the island of Cuba, where we were first becalmed, and

then followed a stormy wind, which carried us away five leagues to the

eastward. The 10th, we spent the night making several trips. The 11th,

the wind coming about, we weathered Cape Corrientes, to make that of St.

Antony; and at length, after plying a considerable time, and sounding, we

came to an anchor the 12th, upon good ground, in fifteen fathom water, in

the creek formed by that cape, which is in 22° of north latitude, and 288°

35′ of longitude.

We stayed there only till next day, being the 13th, when the wind

seemed to be favorable to enter upon the Bay of Mexico. We made ready and

sailed, steering N. W. and by N. and N. N. W. to weather the said cape,

and prosecute our voyage: but by the time we were five leagues from the

place of our departure, we perceived the wind shifted upon us, and not

knowing which way the currents sate, we stood E. and by N. and held that

course till the 14th, when M. de Beaujeu, who was aboard the Joly, joined

us again, and having conferred with M. de la Salle about the winds being

contrary, proposed to him to return to Cape St. Antony, to which M. de la

Salle consented, to avoid giving him any cause to complain, though there

was no great occasion for so doing, and accordingly we went and anchored

in the place from whence we came.

The next day, being the 15th, M. de la Salle sent some men ashore, to

try whether we could fill some casks with water. They brought word, they

had found some in the wood which was not much amiss, but that there was no

conveniency for rolling of the casks; for which reason rundlets were sent,

and as much water brought in them as filled six or seven of our water

casks.

The same men reported that they had found a glass bottle, and in it a

little wine, or some other liquor, almost dead. This was all the

provision we found in that place, by which it appears how much M. Tonty

was misinformed, since in his book, page 242, he says, we found in that

island several tuns [sic] of Spanish wine, good brandy, and

Indian wheat, which the Spaniards had left or abandoned; and it is a mere

invention, without anything of truth.

The 16th, the weather being still calm, the men went ashore again for

five or six more casks of water. I was to have gone with them, had not an

indisposition, which I first felt in the Island of Pines, and afterwards

turned to a

tertian ague,

prevented me. Therefore I can give no account

of that island, any further than what I could see from the ships, which

was abundance of that sort of palm-trees in French called lataniers, fit

for nothing but making of brooms, or scarce any other use. That day we

saw some smokes far within the island, and guessed they might be a signal

of the number of our ships, or else made by some of the country hunters

who had lost their way.

The next night preceding the 17th, the wind freshening from the N.

W., and starting up all on a sudden, drove the vessel called La Belle upon

her anchor, so that she came foul of the bowsprit of the Aimable, carrying

away the spritsail-yard and the spritsail-top-sail-yard; and had not they

immediately veered out the cable of the Aimable, the vessel La Belle would

have been in danger of perishing, but escaped with the loss of her mizen,

which came by the board, and of about a hundred fathoms of cable and an

anchor.

The 18th, the wind being fresh, we made ready, and sailed about ten

in the morning, stand N. and N. and by W., and held our course till noon;

the point of Cape St. Anthony bearing east and west with us, and so

continued steering north-west, till the 19th at noon, when we found

ourselves in the latitude of 22° 58′

north, and in 287° 54′ longitude.

Finding the wind shifting from one side to another, we directed our

course several ways, but that which proved advantageous to us was the fair

weather, and that was a great help, so that scarce a day passed without

taking an observation.

The 20th we found the variation of the needle was 5° west, and we

were in 26° 40′ of north latitude, and 285° 16′

longitude. The 23d it

grew very cloudy, which threatened stormy weather, and we prepared to

receive it, but came off only with the apprehension, the clouds dispersing

several ways, and we continued till the 27th in and about 28° 14′, and

both by the latitude and estimation it was judged that we were not far

from land.

The bark called La Belle was sent out to discover and keep before,

sounding all the way; and half an hour before sunset we saw the vessel La

Belle put out her colors and lie by for us. Being

come up with her, the master told us he had found an oozy bottom at

thirty-two fathom water. At eight of the clock we sounded also, and found

forty fathom, and at ten but twenty-five. About midnight, La Belle

sounding again, found only seventeen, which being a demonstration of the

nearness of the land, we lay by for the Joly, to know what M. de Beaujeu

designed, who being come up, lay by with us.

The 27th, M. de Beaujeu sent the Chevalier d’Aire, his lieutenant,

and two pilots to M. de la Salle, to conclude upon the course we were to

steer, and it was agreed we should stand W. N. W. till we came into six

fathom water; that then we should run west, and when we had discovered the

land, boats should be sent to view the country. Matters being thus agreed

on, we sailed again, sounding all the way for the more security, and about

ten were in ten or eleven fathoms water, the bottom fine greyish sand and

oozy. At noon, were in 26° 37′ of north latitude.

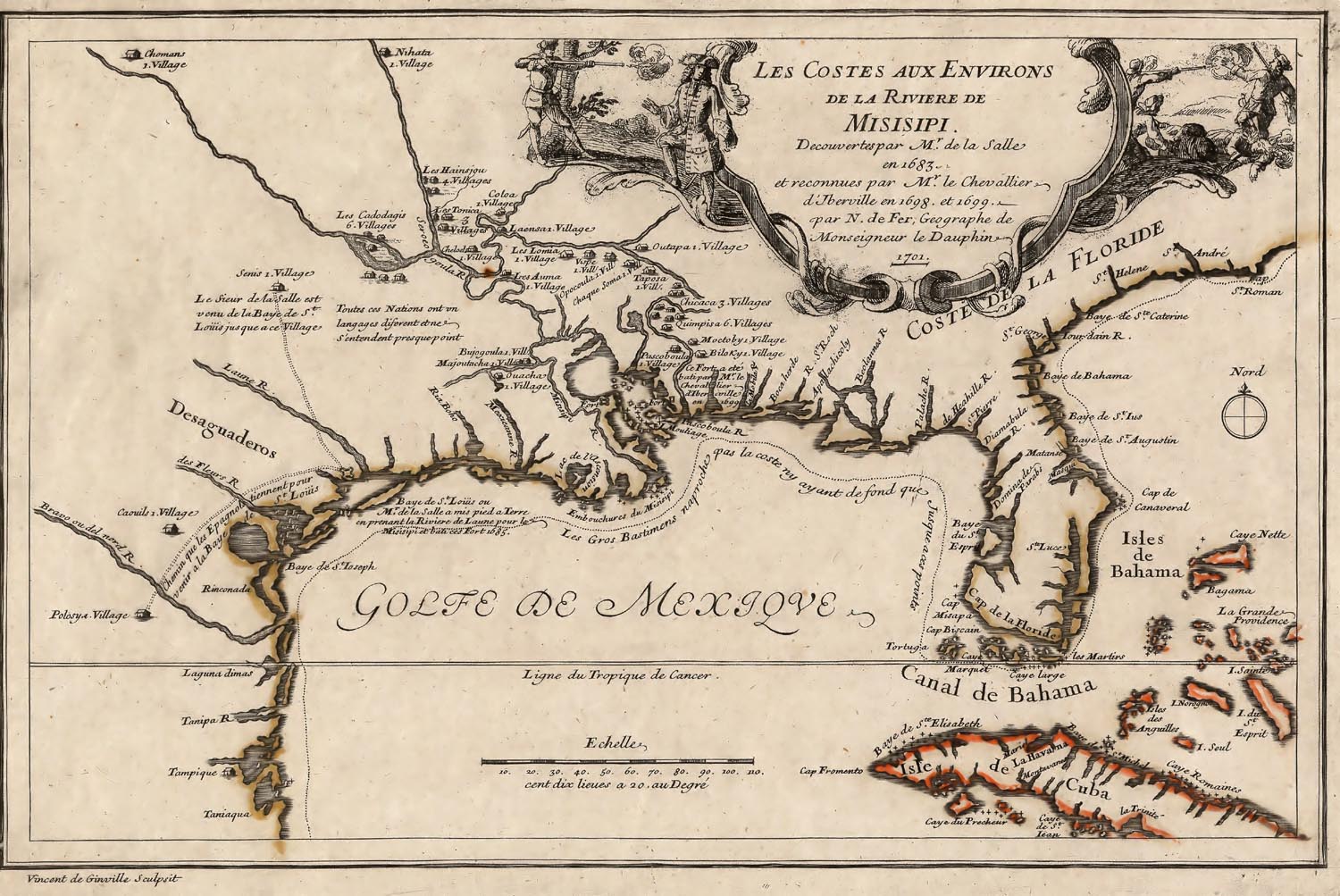

The 28th, being in eight or nine fathom water, we perceived the bark

La Belle, which kept ahead of us, put out her colors, which was the signal

of her having discovered something. A sailor was sent up to the main-top,

who descried the land, to the N. E., not above six leagues’ distance from

us, which being told to M. de Beaujeu, he thought fit to come to an

anchor.

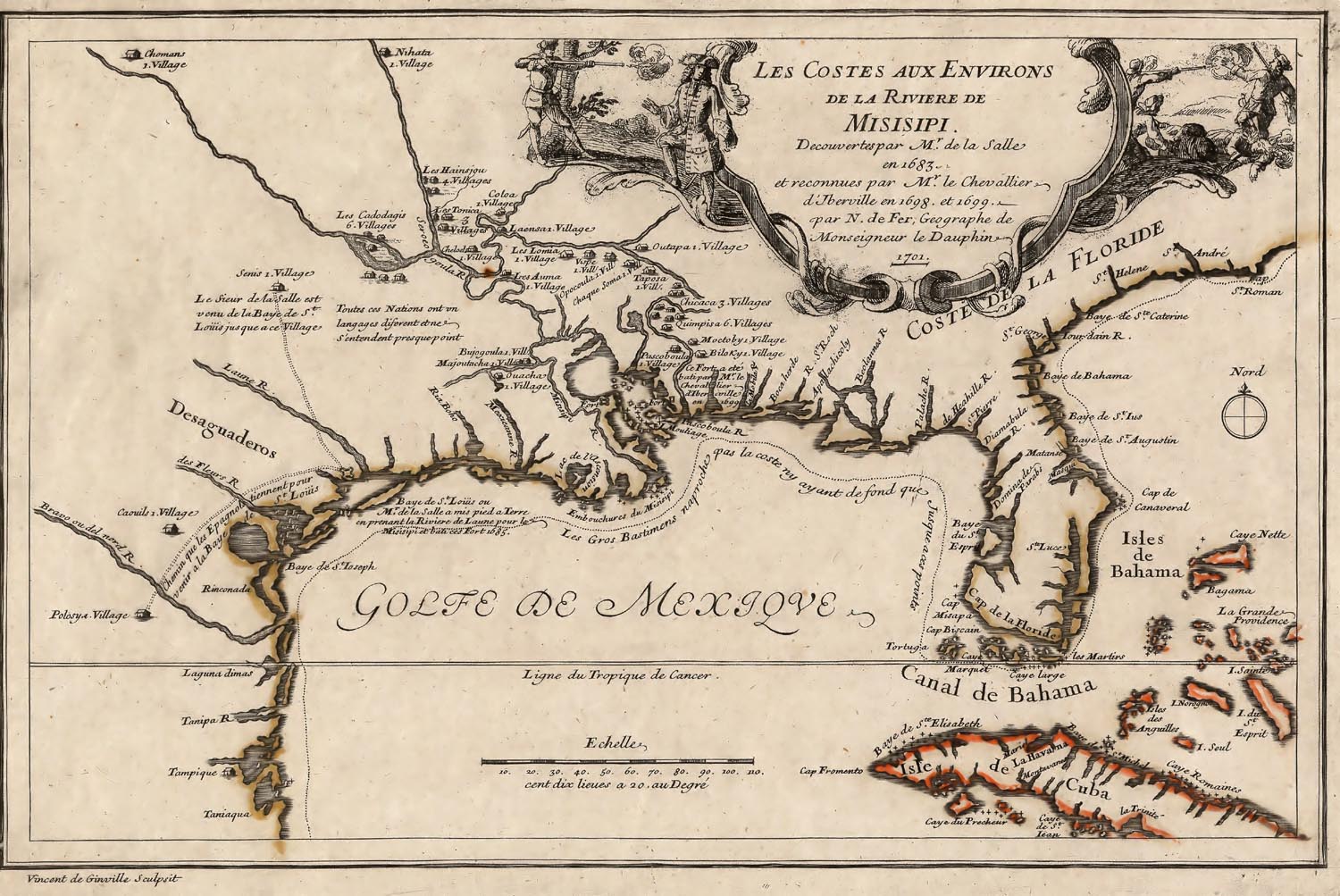

There being no man among us who had any knowledge of that bay, where

we had been told the currents were strong, and sate swiftly to the

eastward, it made us suspect that we were fallen off, and that the land we

saw must be the Bay of Apalache, which obliged us on the 29th to steer W.

N. W., still keeping along the land, and it was agreed that the Joly

should follow us in six fathom water.

The 30th, the Chevalier d’Aire and the second pilot of the Joly came

aboard us to confer and adjust by our reckonings what place we might be

in, and they all agreed, according to M. de la Salle’s opinion, that the

currents had set us to the eastward, for which reason we held on our

course, as we had done the day before, to the N.W., keeping along the

shore till the 1st of January, 1685, when we perceived that the currents

forced us towards the land, which obliged us to come to an anchor in six

fathom water.

We had not been there long before the bark La Belle made a signal

that she had discovered land, which we descried at about four leagues’

distance from us. Notice was given to M. de Beaujeu who drew near to us,

and it was resolved to send some person to discover and take an account of

the land that appeared to us.

Accordingly a boat was manned, and into it went M. de la Salle, the

Chevalier d’Aire, and several others; another boat was also put out,

aboard which I went with ten or twelve of our gentlemen, to join M. de la

Salle, and the bark La Belle was ordered to follow, always keeping along

the shore; to the end that if the wind should rise we might get aboard

her, to lose no time.

Some of those who were in M. de la Salle’s boat, and the foremost,

went ashore and saw a spacious plain country of much pasture ground, but

had not the leisure to make any particular discovery, because, the wind

freshening, they were obliged to return to their boat, to come aboard

again; which was the reason why we did not go quite up to the shore, but

returned with them to our ship. All that could be taken notice of was a

great quantity of wood along the coast. We took an observation, and found

29° 10′ of north latitude.

The 2nd, there arose a fog, which made us lose sight of the Joly. The

next day, the weather clearing up, we fired some cannon-shot, and the Joly

answered; and towards the evening we perceived her to the windward of us.

We held on our course, making several trips till the 4th, in the evening,

when, being in sight and within two leagues of the land, we came to an

anchor to expect the Joly, for which we were in pain.

The 5th, we set sail, and held on our course, W. S. W., keeping along

the shore till about six in the evening, when we stood away to the

southward, and anchored at night in six fathom water.

The 6th, we would

have made ready to sail, but the pilot perceiving that the sea broke

astern of us, and that there were some shoals, it was thought proper to

continue at anchor till the wind changed, and we accordingly stayed there

the 6th and all the 7th. The 8th, the wind veering about, we stood out a

little to sea, to avoid those shoals, which are very dangerous, and

anchored again a league from thence. Upon advice that the bark La Belle

had discovered a small island, which appeared between the two points of a

bay, M. de la Salle sent a man up to the round-top, from whence both the

one and the other were plainly to be seen, and according to the sea charts

we had with us, that was supposed to be the bay of the Holy Ghost.

The 9th, M. de la Salle sent to view those shoals. Those who went

reported there was a sort of bank which runs along the coast; that they

had been in one fathom water, and discovered the little island before

mentioned, and as for the sand-bank there is no such thing marked down in

the charts. M. de la Salle having examined the

reckonings, was confirmed in his opinion that we were in the Bay of

Apalache, and caused us to continue the same course.

The 10th, he took an observation and found 29° 23′ north latitude.

The 11th, we were becalmed, and M. de la Salle resolved to go ashore, to

endeavor to discover what he was looking for; but as we were making ready,

the pilot began to mutter because five or six of us were going with M. de

la Salle, who too lightly altered his design, to avoid giving offence to

brutish people. In that particular he committed an irretrievable error;

for it is the opinion of judicious men who, as well as I, saw the rest of

that voyage, that the mouth of one of the branches of the Mississippi

River, and the same whose latitude M. de la Salle had taken when he

travelled to it from Canada, was not far from that place, and that we must

of necessity be near the Bay of the Holy Ghost.

It was M. de la Salle’s design to find that bay, and having found it,

he had resolved to have set ashore about thirty men, who were to have

followed the coast on the right and left, which would infallibly have

discovered to him that fatal river, and have prevented many misfortunes;

but Heaven refused him that success, and even made him regardless of an

affair of such consequence, since he was satisfied with sending thither

the pilot, with one of the masters of the bark La Belle, who returned

without having seen anything, because a fog happened to rise; only the

master of the bark said he believed there was a river opposite to those

shoals, which was very likely; and yet M. de la Salle took no notice of

it, nor made any account of that report.

The 12th, the wind being come about, we weighed and directed our

course S. W., to get further from the land. By an observation found

25°

50′ north latitude, and the wind shifting, and the currents which set from

the seaward driving us ashore, it was found convenient to anchor in four

or five fathom water, where we spent all the night.

The 13th, we perceived our water began to fall short, and therefore

it was requisite to go ashore to fill some casks. M. de la Salle proposed

it to me to go and see it performed, which I accepted of, with six of our

gentlemen who offered their service. We went into the boat, with our

arms; the boat belonging to the bark La Belle followed ours, with five or

six men; and we all made directly for the land.

We were very near the shore when we discovered a number of naked men

marching along the banks, whom we supposed to be native

savages. We drew within two musket shots of the land, and the shore being

flat, the wind setting from the offing, and the sea running high, dropped

our anchors, for fear of staving our boats.

When the savages perceived we had stopped, they made signs to us with

skins, to go to them, showed us their bows, which they laid down upon the

ground, and drew near to the edge of the shore; but because we could not

get ashore, and still they continued their signals, I put my handkerchief

on the end of my firelock, after the manner of a flag, and made signs to

them to come to us. They were some time considering of it, and at last

some of them ran into the water up to their shoulders, till perceiving

that the waves overwhelmed them, they went out again, fetched a large

piece of timber, which they threw into the sea, placed themselves along

both sides of it, holding fast to it with one arm and swimming with the

other; and in that manner they drew near to our boat.

Being in hopes that M. de la Salle might get some information from

those savages, we made no difficulty of taking them into our boat, one

after another, on each side, to the number of five, and then made signs to

the rest to go to the other boat, which they did, and we carried them on

board.

M. de la Salle was very well pleased to see them, imagining they

might give him some account of the river he sought after; but to no

purpose, for he spoke to them in several of the languages of the savages,

which he knew, and made many signs to them, but still they understood not

what we meant, or if they did comprehend anything, they made signs that

they knew nothing of what he asked; so that having made them smoke and

eat, we showed them our arms and the ship, and when they saw at one end of

it some sheep, swine, hens, and turkeys, and the hide of a cow we had

killed, they made signs that they had of all those sorts of creatures

among them.

We gave them some knives and strings of beads, after which, they were

dismissed, and the waves hindering us from coming too near the shore, they

were obliged to leap into the water, after we had made fast about their

necks, or to the tuft of hair they have on the top of the head, the knives

and other small presents M. de la Salle had given them.

They went and joined the others who expected them, and were making

signs to us to go to them; but not being able to make the shore, we stood

off again and returned to our ship. It is to be observed, that when we

were carrying them back, they made some signs

to us, by which we conceived they would signify to us that there was a

great river that way we were passed, and that it occasioned the shoals we

had seen.

The wind changing the same day, we weighed anchor and stood to the

southward, to get into the offing, till the 14th, in the morning, when we

were becalmed. At noon we were in 28° 51′ of north latitude. The wind

freshened, and in the evening we held on our course, but only for a short

time, because the wind setting us towards the shore, we were obliged to

anchor again, whereupon M. de la Salle again resolved to send ashore, and

the same persons embarked in the same boats to that effect.

We met with the same obstacles that had hindered us the day before,

that is, the high sea, which would not permit us to come near the shore,

and were obliged to drop anchor in fourteen feet water. The sight of

abundance of goats and bullocks, differing in shape from ours, and running

along the coast, heightened our earnestness to be ashore. We therefore

sounded to see whether we might get to land by stripping, and found we

were on a flat, which had four feet water, but that beyond it there was a

deep channel. Whilst we were consulting what to do, a storm arose, which

obliged M. de la Salle to fire a gun for us to return aboard, which we did

against our inclination.

M. de la Salle was pleased with the report we made him, and by it

several were encouraged to go ashore to hunt, that we might have some

fresh meat. We spent all that night, till the next morning, in hopes of

returning soon to that place; but the wind changing, forced us to weigh

and sail till the evening, when we dropped anchor in six fathom water.

The land, which we never departed from very far, appeared to us very

pleasant, and having lain there till the 16th, that morning we sailed W.

S. W. We weathered a point, keeping a large offing, because of the sea’s

beating upon it, and stood to the southward. At noon we were in 28 20

of north latitude, and consequently found the latitude declined, by which

we were sensible that the coast tended to the southward. At night we

anchored in six fathom water.

The 17th, the wind continuing the same, we held on our course S. W.,

and having about then [cr] discovered a sort of river, M. de la Salle

caused ten of us to go into a boat to take a view of that coast, and see

whether there was not some place to land. He ordered me, in case we found

any convenient place, to give him notice either by fire or smoke.

We set out, and found the shoals obstructed our descent. One of

our men went naked into the water to sound that sand bank, which lay

between us and the land; and having shown us a place where we might pass,

we with much difficulty forced our boat into the channel, and six or seven

of us landed, after ordering the boat to go up into that which had

appeared to us to be a river, to see whether any fresh water could be

found.

As soon as we were landed, I made a smoke to give notice to M. de la

Salle, and then we advanced both ways, without straggling too far, that we

might be ready to receive M. de la Salle, who was to come, as he did, soon

after, but finding the surges run high, he returned, and our boat finding

no fresh water, came back and anchored to wait for us.

We walked about every way, and found a dry soil, though it seemed to

be overflowed at some times; great lakes of salt water, little grass, the

track of goats on the sand, and saw herds of them, but could not come near

them; however, we killed some ducks and bustards. In the evening, as we

were returning, we missed an English seaman; fired several shots to give

him notice, searched all about, waited till after sunset, and at last,

hearing no tidings of him, we went into the boat to return aboard.

I gave M. de la Salle an account of what we had seen, which would

have pleased him had the river we discovered afforded fresh water. He was

also uneasy for the lost man; but about midnight we saw a fire ashore, in

the place we came from, which we supposed to be made by our man, and the

boat went for him as soon as it was day on the 18th.

After that we made several trips, still steering towards the S. W.,

and then ensued a calm, which obliged us to come to an anchor. Want of

water made us think of returning towards the river, where we had been the

day before. M. de la Salle resolved to set a considerable number of men

ashore, with sufficient ammunition, and to go with them himself, to

discover and take cognizance of that country, and ordered me to follow

him. Accordingly we sailed back, and came to an anchor in the same place.

All things necessary for that end being ordered on the 19th, part of

the men were put into a boat; but a very thick fog rising, and tak ing

away the sight of land, the compass was made use of, and the fog

dispersing as we drew near the land, we perceived a ship making directly

towards us, and that it was the Joly, where M. de Beaujeu commanded, which

rejoiced us; but our satisfaction was not lasting, and it will appear by

the sequel, that it were to have been wished that

M. de Beaujeu had not joined us again, but that he had rather gone away

for France, without ever seeing of us.

His arrival disconcerted the execution of our enterprise. M. de la

Salle, who was already on his way, and those who were gone before him,

returned aboard, and some hours after, M. de Beaujeu sent his Lieutenant,

M. de Aire, attended by several persons, as well clergymen as others,

among whom was the Sieur Gabaret, second pilot of the Joly.

M. de Aire complained grievously to M. de la Salle, in the name of M.

de Beaujeu, for that, said he, we had left him designedly; which was not

true, for, as I have said, the Joly lay at anchor ahead of us when we were

separated from her; we fired a gun to give her notice of our departure, as

had been concerted, and M. de Beaujeu answered it; besides that, if we had

intended to separate from him, we should not have always held our course

in sight of land, as we had done, and that had M. de Beaujeu held the same

course, as had been agreed, he had not been separated from us.

There were afterwards several disputes between the Captains and the

pilots, as well aboard M. de la Salle as aboard M. de Beaujeu, when those

gentlemen returned, about settling exactly the place we were in, and the

course we were to steer; some positively affirming we were farther than we

imagined, and that the currents had carried us away; and the others, that

we were near the Magdalen River.

The former of those notions prevailed, whence, upon reflection, M. de

la Salle concluded that he must be past his river, which was but too true;

for that river emptying itself in the sea by two channels, it followed

that one of the mouths fell about the shoals we had observed on the 6th of

the month; and the rather because those shoals were very near the latitude

that M. de la Salle had observed when he came by the way of Canada to

discover the mouth of that river, as he told me several times.

This consideration prevailed with M. de la Salle to propose his

design of returning towards those shoals. He gave his reasons for so

doing, and exposed his doubts; but his ill fortune made him not be

regarded. Our passage had taken up more time than had been expected, by

reason of the calms; there was a considerable number of men aboard the

Joly, and provisions grew short, insomuch that they said it would not hold

out to return, if our departure were delayed. For this reason M. de

Beaujeu demanded provisions of M. de la Salle; but he asking enough for a

long time, M. de la Salle answered he could only give him enough for a

fortnight, which was

more time than was requisite to reach the place he intended to return to;

and that besides he could not give him more provisions, without rummaging

all the stores to the bottom of the hold, which would endanger his being

cast away. Thus nothing was concluded, and M. de Beaujeu returned to his

own ship.

In the meantime, want of water began to pinch us, and M. de la Salle

resolved to send to look for some about the next river. Accordingly he

ordered the two boats that had been made ready the day before, to go off.

He was aboard one of them himself, and directed me to follow him. M. de

Beaujeu also commanded his boat to go for wood. By the way, we met the

said Sieur de Beaujeu in his yawl returning from land, with the Sieur

Minet, an engineer, who told us they had been in a sort of salt pool, two

or three leagues from the place where the ships were at anchor; we held on

our way and landed.

One of our boats, which was gone ahead of us, had been a league and a

half up the river, without finding any fresh water in its channel; but

some men wandering about to the right and left, had met with divers

rivulets of very good water, wherewith many casks were filled.

We lay ashore, and our hunters having that day killed a good store of

ducks, bustards, and teal, and the next day two goats, M. de la Salle sent

M. de Beaujeu part. We feasted upon the rest, and that good sport put

several gentlemen that were then aboard M. de Beaujeu, among whom were M.

du Hamel, the ensign and the king’s clerk, upon coming ashore to partake

of the diversion; but they took much pains and were not successful in

their sport.

In the meantime many casks were filled with water, as well for our

ship as for M. de Beaujeu’s. Some days after M. d’Aire, the lieutenant,

came ashore to confer with M. de la Salle, and to know how he would manage

about the provisions; but both of them persisting in their first

proposals, and M. de la Salle perceiving that M. de Beaujeu would not be

satisfied with provisions for fifteen days, which he thought sufficient to

go to the place where he expected to find one of the branches of the

Mississippi, which he with good reason believed to be about the shoals I

have before spoken of, nothing was concluded as to that affair. M. d’Aire

returned to his captain, and M. de la Salle resolved to land his men;

which could not be done for some days, because of the foil weather; but in

the meantime we killed much game.

During this little interval, M. de la Salle being impatient to get

some intelligence of what he sought after, resolved to go himself upon

discovery, and to seek out some more useful and commodious river than that

where they were. To this purpose he took five or six of us along with

him. We set out one morning in so thick a fog, that the hindmost could

not perceive the track of the foremost, so that we lost M. de la Salle for

some time.

We travelled till about three in the afternoon, finding the country

for the most part sandy, little grass, no fresh water, unless in some

sloughs, the track of abundance of wild goats, lakes full of ducks, teals,

water-hens, and having taken much pains returned without success.

The next morning M. de la Salle’s Indian, going about to find wild

goats, came to a lake which had a little ice upon it, the weather being

cold, and abundance of fish dying about the edges of it. He came to

inform us; we went to make our provision of them, there were some of a

prodigious magnitude, and among the rest extraordinary large trouts, or

else they were some sort of fish very like them. We caused some of each

of a sort to be boiled in salt water, and found them very good. Thus

having plenty of fish and flesh, we began to use ourselves to eat them

both without bread.

Whilst we lived thus easy enough, M. de la Salle expected with

impatience to know what resolution M. de Beaujeu would take, that he might

either go to the place where he expected to find the Mississippi, or

follow some other course; but at last, perceiving that his affairs did not

advance, he resolved to put his own design in execution, the purport

whereof was to land one hundred and twenty, or one hundred and thirty men,

to go along the coast, and continue it till they had found some other

river, and that at the same time the bark La Belle should hold the same

course at sea, still keeping along the coast, to relieve those ashore in

time of need.

He gave me and M. Moranget, his nephew, the command of that small

company, he furnished us with all sorts of provisions for eight or ten

days, as also arms, tools, and utensils, we might have occasion for, of

which every man made his bundle. He also gave us written instructions of

what we were to do, the signals we were to make; and thus we set out on

the 4th of February.

We took our way along the shore. Our first day’s journey was not

long; we encamped on a little rising ground, heard a cannon shot, which

made us uneasy, made the signals that had been appointed, and the next

day, being the 5th, we held on our march, M. Moranget bringing up the

rear, and I leading the van.

I will not spend time in relating several personal accidents,

inconsiderable in themselves, or of no consequence, the most considerable

of them being the want of fresh water; but will proceed to say, that after

three days’ march we found a great river, where we halted and made the

signals agreed on, encamping on a commodious spot of ground till we could

hear of the boat, which was to follow us, or of our ships.

But our provisions beginning to fall short, and none of our ships

appearing, being, besides, apprehensive of some unlucky accident

occasioned by the disagreement between M. de la Salle and M. de Beaujeu,

the chief of our company came together to know what resolution we should

take. It was agreed that we should spare our provisions to endeavor to go

on to some place where we might find bullocks; but it was requisite to

cross the river, and we knew not how, because we were too many of us; and

therefore it was decreed to set some carpenters there were among us at

work to build a little boat, which took them up the eleventh and twelfth

of February.

The 13th we were put out of our pain by two vessels we discovered at

sea, which we knew to be the Joly and La Belle, to whom we made our

signals with smoke. They came not in then, because it was late, but the

next day, being the 14th, in the morning, the boat, with the Sieur

Barbier, and the pilot of the bark La Belle, came up, and both sounded the

mouth of the river.

They sounded on the bar from ten to twelve feet water, and within it

from five to six fathom; the breadth of the river being about half a

quarter of a league. They sounded near the island, which lies between the

two points of the bay, and found the same depth. The boat of the Joly

came and sounded on the other side of the channel, and particularly along

the shoals, I know not to what purpose. The same day M. de la Salle, for

whom we were much in pain, came also, and as soon as he arrived he caused

the boat to be laden with such provisions as we stood in need of, but the

wind being contrary, it could not come to us till the next day, being the

15th.

That same day M. de la Salle came ashore to view the place and

examine the entrance into the river, which he found to be very good.

Having considered all particulars, he resolved to send in the barks La

Belle and L’Aimable, that they might be under shelter, to which purpose he

ordered to sound, and to know whether those two vessels could both come in

that same bay. M. de Beaujeu caused also the place to be sounded, and lay

ashore on the other side of the river, where he took notice there were

vines which run up the trees like

our wall vines, some woods, and the carcasses of bullocks, which he

supposed to have died with thirst.

The 16th, the pilots of the Joly, L’Aimable, and La Belle, went again

to sound. They found the entrance easy, and gave it under their hands.

The 17th, they fixed stakes to mark out the way, that the vessels might

come safe in. All things seemed to promise a happy event.

The 18th the Chevalier d’Aire came ashore to confer with M. de la

Salle, who, being desirous to have the flyboat L’Aimable come in that day,

ordered the most weighty things in her to be unloaded, as the cannon, the

iron, and some other things. It was my good fortune that my chest stood

in the way, and was also unloaded, but that unlading could not be done

till the next day, being the 19th. That being performed, the Captain

affirmed it would go in at eight feet water.

The 20th M. de la Salle sent orders to that Captain to draw near the

bar, and to come in at high water, of which a signal should be given him;

he also ordered the pilot of the bark La Belle to go aboard the flyboat,

to be assisting when it came in. The Captain would not receive him

aboard, saying he could carry in his ship without his help. All these

precautions proved of no use; M. de la Salle could not avert his ill fate.

He having taken notice of a large tree on the bank of the river, which he

judged fit to make a canoe, sent 7 or 8 workmen to hew it down, two of

whom returned some time after, in a great fright, and told him they had

narrowly escaped being taken by a company of savages, and that they

believed the others had fallen into their hands. M. de la Salle ordered

us immediately to handle our arms, and to march with drums beating against

the savages, who seeing us in that posture, faced about and went off.

M. de la Salle being desirous to join those savages, to endeavor to

get some information from them, ordered ten of us to lay down our arms and

draw near them, making signs to them at the same time, to come to us.

When they saw us in that posture and unarmed, most of them also laid down

their bows and arrows and came to meet us, caressing us after their

manner, and stroking first their own breasts and then ours, then their own

arms and afterwards ours. By these signs they gave us to understand that

they had a friendship for us, which they expressed by laying their hands

on their hearts, and we did the same on our part.

Six or seven of those savages went along with us, and the rest kept

three of our men in the nature of hostages. Those who went

with us were made much of, but M. de la Salle could learn nothing of them,

either by signs or otherwise; all they could make us understand was, that

there was good hunting of bullocks in the country. We observed that their

yea consisted in a cry, fetched from the bottom of the throat, not unlike

the call of a hen to gather her chickens. M. de la Salle gave them some

knives, hatchets, and other trifles, with which they seemed well pleased,

and went away.

M. de la Salle was glad to be rid of those people, because he was

willing to be present when the flyboat came in; but his ill fate would not

permit it. He thought fit to go himself along with those savages, and we

followed him, thinking to have found our men in the same place where we

left them; but perceived, on the contrary, that the savages had carried

them away to their camp, which was a league and a half from us, and M. de

la Sablonniere, lieutenant of foot, being one of those the savages had

taken with them, M. de la Salle resolved to go himself to fetch him away,

an unhappy thought which cost him dear.

As we were on our way towards the camp of the savages, happening to

look towards the sea, we saw the flyboat L’Aimable under sail, which the

savages who were with us admired, and M. de la Salle observing it

narrowly, told us those people steered wrong, and were standing towards

the shoals, which made him very uneasy, but still we advanced. We arrived

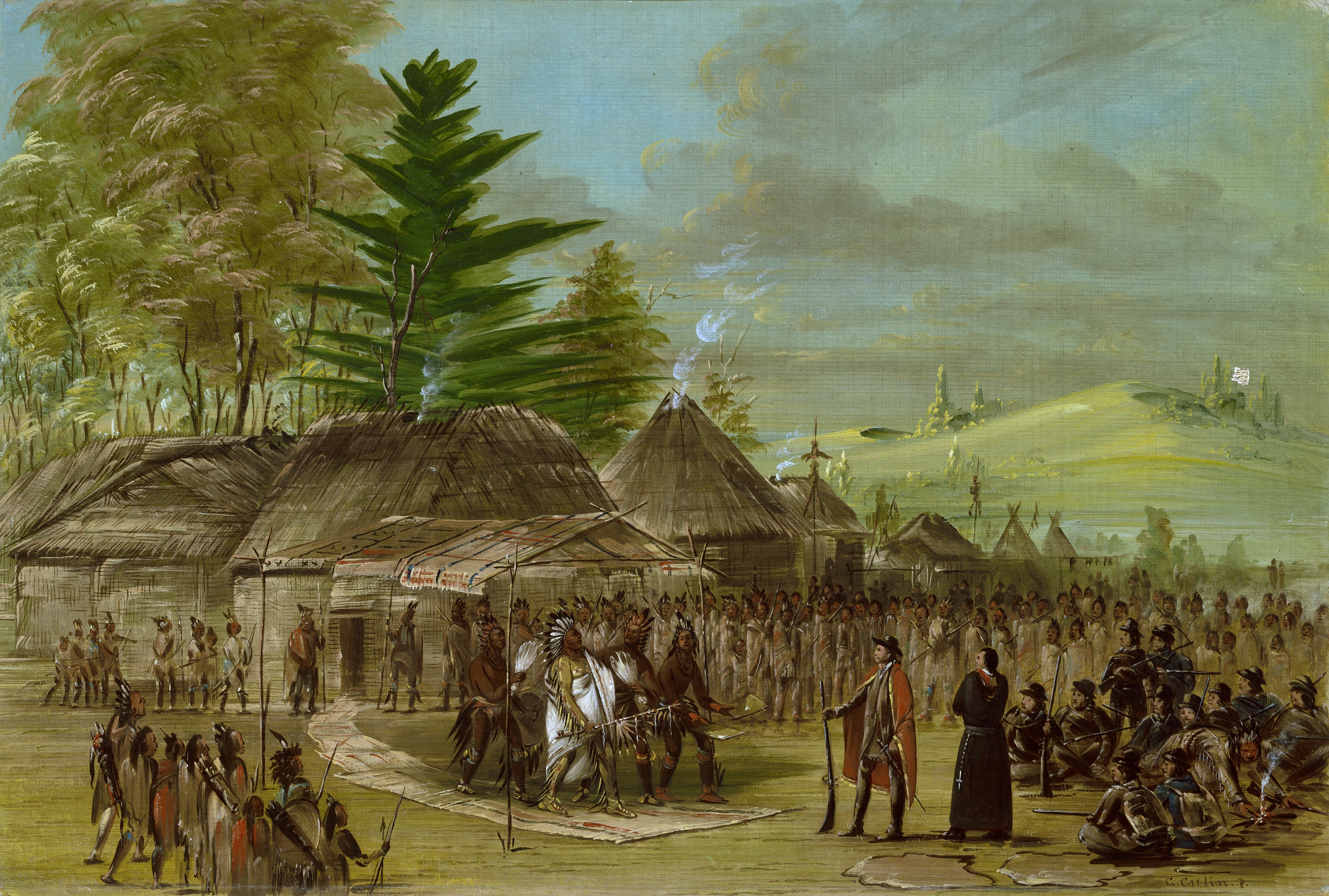

at the camp of the savages, which stood upon an eminence, and consisted of

about fifty cottages made of rush mats, and others of dried skins, and

built with long poles bowed round at the top, like great ovens, and most

of the savages sitting about, as if they were upon the watch.

We were still advancing into the village when we heard a cannonshot,

the noise whereof struck such a dread among the savages, that they all

fell flat upon the ground; but M. de la Salle and we were too sensible it

was a signal that our ship was aground, which was confirmed by seeing them

furl their sails; however, we were gone too far to return, our men must be

had, and to that purpose we must proceed to the hut of the

commander-in-chief.

As soon as we arrived there M. de la Salle was introduced; many of

the Indian women came in, they were very deformed, and all naked,

excepting a skin girt about them which hung down to their knees. They

would have led us to their cottages, but M. de la Salle had ordered us not

to part, and to observe whether the Indians did not draw together, so that

we kept together, standing upon our guard, and I was always with him.

They brought us some pieces of beef, both fresh and dried in the air

and smoke, and pieces of porpoise, which they cut with a sort of knife

made of stone, setting one foot upon it and holding with one hand whilst

they cut with the other. We saw nothing of iron among them. They had

given our men, that came with them, to eat, and M. de la Salle being

extraordinary uneasy we soon took leave of them to return. At our going

out we observed about forty canoes, some of them like those M. de la Salle

had seen on the Mississippi, which made him conclude he was not far from

it.

We soon arrived at our camp, and found the misfortune M. de la Salle

had apprehended was but too certain. The ship was stranded on the shoals.

The ill management of the captain, or of the pilot, who had not steered by

the stakes placed for that purpose; the cries of a sailor posted on the

main-top, who cried amain, “luff,” which was to steer towards the passage

marked out, whilst the wicked captain cried out “Come no nearer,” which

was to steer the contrary course; the same captain’s carelessness in not

dropping his anchor as soon as the ship touched, which would have

prevented her sticking aground; the folly of lowering his main-sheet and

hoisting out his sprit-sail, the better to fall into the wind and secure

the shipwreck; the captain’s refusing to admit the pilot of the bark La

Belle, whom M. de la Salle had sent to assist him; the sounding upon the

shoals to no purpose, and several other circumstances reported by the

ship’s crew, and those who saw the management, were infallible tokens and

proofs that the mischief had been done designedly and advisedly, which was

one of the blackest and most detestable actions that man could be guilty

of.

This misfortune was so much the greater, because that vessel

contained almost all the ammunition, utensils, tools, and other

necessaries for M. de la Salle’s enterprise and settlement. He had need

of all his resolution to bear up against it; but his intrepidity did not

forsake him, and he applied himself, without grieving, to remedy what

might be. All the men were taken out of the ship; he desired M. de

Beaujeu to lend him his long boat, to help save as much as might be. We

began with powder and meal. About thirty hogs-heads of wine and brandy

were saved, and fortune being incensed against us, two things contributed

to the total loss of all the rest.

The first was, that our boat which hung at the stern of the ship run

aground, was maliciously staved in the night, so that we had none left but

M. de Beaujeu’s. The second, that the wind blowing in from the offing

made the waves run high, which beating violently

against the ship split her, and all the light goods were carried out at

the opening by the water. This last misfortune happened also in the

night. Thus everything fell out most unhappily, for had that befallen in

the day abundance of things might have been saved.

Whilst we were upon this melancholy employment, about a hundred or a

hundred and twenty of the natives came to our camp with their bows and

arrows. M. de la Salle ordered us to handle our arms and stand upon our

guard. About twenty of those Indians mixed themselves among us to observe

what we had saved of the shipwreck, upon which there were several

sentinels to let none come near the powder.

The rest of the Indians stood in parcels, or peletons. M. de la

Salle, who was acquainted with their ways, ordered us to observe their

behavior, and to take nothing from them, which nevertheless did not hinder

some of our men from receiving some pieces of meat. Some time after, when

the Indians were about departing, they made signs to us to go a hunting

with them; but, besides that there was sufficient cause to suspect them,

we had enough other business to do. However, we asked whether they would

barter for any of their canoes, which they agreed to. The Sieur Barbier

went along with them, purchased two for hatchets, and brought them.

Some days after, we perceived a fire in the country, which spread

itself and burnt the dry weeds, still drawing towards us; whereupon M. de

la Salle made all the weeds and herbs that were about us be pulled up, and

particularly all about the place where the powder was. Being desirous to

know the occasion of that fire, he took about twenty of us along with him,

and we marched that way, and even beyond the fire, without seeing anybody.

We perceived that it run towards the W. S. W., and judged it had begun

about our first camp, and at the village next the fire.

Having spied a cottage near the bank of a lake, we drew towards it,

and found an old woman in it, who fled as soon as she saw us; but having

overtaken and given her to understand that we would do her no harm, she

returned to her cottage, where we found some pitchers of water, of which

we all drank. Some time after we saw a canoe coming, in which were two

women and a boy, who being landed, and perceiving we had done the old

woman no harm, came and embraced us in a very particular manner, blowing

upon our ears, and making signs to give us to understand that their people

were a hunting.

A few minutes after seven or eight of the Indians appeared, who, it

is likely, had hid themselves among the weeds when they saw us

coming. Being come up, they saluted us after the same manner as the women

had done, which made us laugh. We stayed there some time with them. Some

of our men bartered knives for goats’ skins, after which we returned to

our camp. Being come thither, M. de la Salle made me go aboard the bark

La Belle, where he had embarked part of the powder, with positive orders

not to carry or permit any fire to be made there, having sufficient cause

to fear everything after what had happened. For this reason they carried

me and all that were with me, our meat every day.

During this time it was that L’Aimable opening in the night, the next

morning we saw all the light things that were come out of it floating

about, and M. de la Salle sent men every way, who gathered up about 30

casks of wine and brandy, and some of flesh, meal, and grain.

When we had gathered all, as well what had been taken out of the

shipwrecked vessel as what could be picked up in the sea, the next thing

was to regulate the provisions we had left proportionably to the number of

men we were; and there being no more biscuit, meal was delivered out, and

with it we made hasty pudding with water, which was none of the best; some

large beans and Indian corn, part of which had taken wet; and everything

was distributed very discreetly. We were very much incommoded for want of

kettles, but M. de Beaujeu gave M. de la Salle one, and he ordered another

to be brought from the bark La Belle, by which means we were all served.

We were still in want of canoes. M. de la Salle sent to the camp of

the Indians to barter for some, and they who went thither observed that

those people had made their advantage of our shipwreck, and had some bales

of Normandy blankets, and they saw several women had cut them in two and

made petticoats of them. They also saw bits of iron of the ship that was

cast away, and returned immediately to make their report to M. de la

Salle, who said we must endeavor to get some canoes in exchange, and

resolved to send thither again the next day. M. du Hamel, ensign to M. de

Beaujeu, offered to go up in his boat, which M. de la Salle agreed to, and

ordered MM. Moranget, his nephew, Desloges, Oris, Gayen, and some others

to bear him company.

No sooner were those gentlemen, who were more hot than wise, landed,

but they went up to the camp of the Indians with their arms in their

hands, as if they had intended to force them, whereupon several of those

people fled. Going into the cottages they found others, to whom M. du

Hamel endeavored to signify by signs that he would

have the blankets they had found restored; but the misfortune was, that

none of them understood one another. The Indians thought it their best

way to withdraw, leaving behind them some blankets and skins of beasts,

which those gentlemen took away, and finding some canoes in their return,

they seized two, and got in to bring them away.

But having no oars, none of them, knowing how to manage those canoes,

and having only some pitiful poles, which they could not tell the right

use of, and the wind being also against them, they made little way, which

the Sieur du Hamel, who was in his boat, perceiving, and that night drew

on, he made the best of his way, forsook them, and returned to the camp.

Thus night came upon them, which obliged those inexperienced

canoe-men, being thoroughly tired, to go ashore to take some rest, and the

weather being cold, they lighted a fire, about which they laid them down

and fell asleep; the sentinel they had appointed doing the same. The

Indians returning to their camp, and perceiving our men had carried away

two canoes, some skins, and blankets, took it for a declaration of war,

resolved to be revenged, and discovering an unusual fire, presently

concluded that our men had halted there. A considerable number of them

repaired to the place, without making the least noise, found our careless

people fast asleep, wrapped up in their blankets, and shot a full volley

of their arrows upon them altogether on a sudden, having first given their

usual shout before they fall on.

The Sieur Moranget awaking with the noise, and finding himself

wounded, started up and fired his piece successfully enough; some others

did the same, whereupon the natives fled. The Sieur Moranget came to give

us the alarm, though he was shot through one of his arms, below the

shoulder, and had another slanting wound on the breast. M. de la Salle

immediately sent some armed men to the place, who could not find the

Indians, but when day appeared they found the Sieurs Oris and Desloges

dead upon the spot, the Sieur Gayen much hurt, and the rest all safe and

sound.

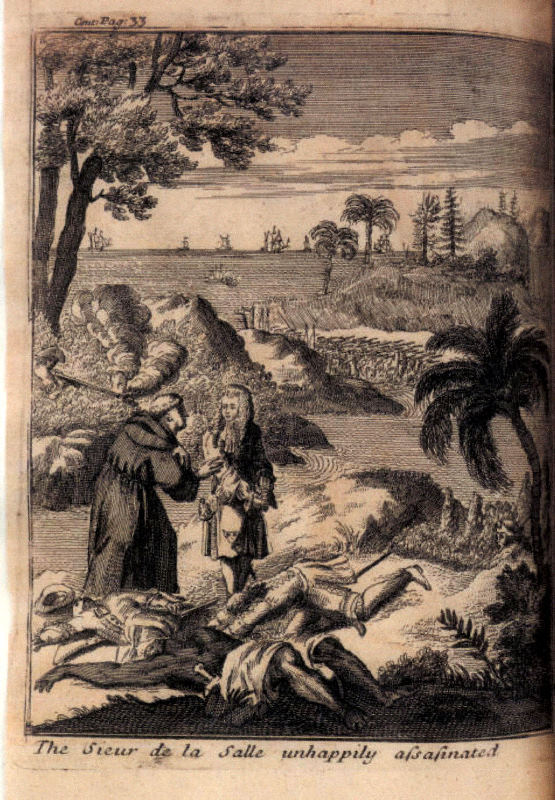

This disaster, which happened the night of the 5th of March, very

much afflicted M. de la Salle; but he chiefly lamented M. Desloges, a

sprightly youth, who served well; but in short, it was their own fault,

and contrary to the charge given them, which was to be watchful, and upon

their guard. We were under apprehensions for MM. Moranget and Gayen, lest

the arrows should be poisoned. It

afterwards appeared they were not; however, M. Moranget’s cure proved

difficult, because some small vessel was cut.

The consequences of this misfortune, together with the concern most

of the best persons who had followed M. de la Salle were under, supported

the design of those who were for returning to France, and forsaking him,

of which number were M. Dainmaville, a priest of the seminary of St.

Sulpice, the Sieur Minet, engineer, and some others. The common

discourses of M. de la Salle’s enemies tending to discredit his conduct,

and to represent the pretended rashness of his enterprise, contributed

considerably towards the desertion; but his resolution prevailing, he

heard and waited all events with patience, and always gave his orders

without appearing the least discomposed.

He caused the dead to be brought to our camp, and buried them

honorably, the cannon supplying the want of bells, and then considered of

making some safer settlement. He caused all that had been saved from the

shipwreck to be brought together into one place, threw up intrenchments

about it to secure his effects, and perceiving that the water of the

river, where we were, rolled down violently into the sea, he fancied that

might be one of the branches of the Mississippi, and proposed to go up it,

to see whether he could find any tokens of it, or of the marks he had left

when he went down by land to the mouth of it.

In the mean time M. de Beaujeu was preparing to depart: the Chevalier

de Aire had many conferences with M. de la Salle about several things; the

latter demanded of M. de Beaujeu particularly the cannon and ball which

were aboard the Joly, and had been designed for him, which M. de Beaujeu

refused, alleging that all those things lay at the bottom of the hold, and

that he could not rummage it without evident danger of perishing; though,

at the same time, he knew we had eight pieces of cannon, and not one

bullet.

I know not how that affair was decided between them, but am sure he

suffered the captain of the flyboat L’Aimable to embark aboard M. de

Beaujeu, though he deserved to be most severely punished, had justice been

done him. His crew followed him, contrary to what M. de Beaujeu had

promised, that he would not receive a man of them. All that M. de la

Salle could do, though so much wronged, was to write to France to M. de

Saignelay, minister of state, whom he acquainted with all the particulars,

as I was informed when I returned, and he gave the packet to M. de

Beaujeu, who sailed away for France.

Having lost the notes I took at that time, and being forced to rely

much upon memory for what I now write, I shall not pretend to be any

longer exact in the dates, for fear of mistaking, and therefore I cannot

be positive as to the day of M. de Beaujeu’s departure, but believe it was

the 14th of March, 1685.

When M. de Beaujeu was gone, we fell to work to make a fort of the

wreck of the ship that had been cast away, and many pieces of timber the

sea threw up; and during that time several men deserted, which added to M.

de la Salle’s affliction. A Spaniard and a Frenchman stole away and fled,

and were never more heard of. Four or five others followed their example,

but M. de la Salle, having timely notice, sent after them, and they were

brought back. One of them was condemned to death, and the others to serve

the King ten years in that country.

When our fort was well advanced, M. de la Salle resolved to clear his

doubts, and to go up the river, where we were, to know whether it was not

an arm of the Mississippi, and accordingly ordered fifty men to attend

him, of which number were M. Cavelier, his brother, and M. Chedeville,

both priests; two Recollet Friars, and several volunteers, who set out in

five canoes we had, with the necessary provisions. There remained in the

fort about a hundred and thirty persons, and M. de la Salle gave me the

command of it, with orders not to have any commerce with the natives, but

to fire at them if they appeared.

Whilst M. de la Salle was absent, I caused an oven to be built, which

was a great help to us, and employed myself in finishing the fort, and

putting it in a posture to withstand the Indians, who came frequently in

the night to range about us, howling like wolves and dogs; but two or

three musket shots put them to flight. It happened one night that, having

fired six or seven shot, M. de la Salle, who was not far from us, heard

them, and being in pain about it, he returned with six or seven men, and

found all things in a good posture.

He told us he had found a good country, fit to sow and plant all

sorts of grain, abounding in beeves and wild fowl; that he designed to

erect a fort farther up the river, and accordingly he left me orders to

square out as much timber as I could get, the sea casting up much upon the

shore. He had given the same orders to the men he had left on the spot,

seven or eight of whom, detached from the rest, being busy at that work,

and seeing a number of the natives, fled, and unadvisably left their tools

behind them. M. de la Salle returning thither, found a paper made fast to

a reed which gave him

notice of that accident, which he was concerned at, because of the tools;

not so much for the value of the loss, as because it was furnishing the

natives with such things as they might afterwards make use of against us.

About the beginning of April, we were alarmed by a vessel which

appeared at sea, near enough to discern the sails, and we supposed they

might be Spaniards who had heard of our coming, and were ranging the coast

to find us out. That made us stand upon our guard, to keep within the

fort, and see that our arms were fit for service. We afterwards saw two

men in that vessel, who, instead of coming to us, went towards the other

point, and by that means passed on without perceiving us.

Having one day observed that the water worked and bubbled up, and

afterwards perceiving it was occasioned by the fish skipping from place to

place, I caused a net to be brought, and we took a prodigious quantity of

fish; among which were many dorados, or gilt-heads, mullets, and others

about as big as a herring, which afforded us good food for several days.

This fishery, which I caused to be often followed, was a great help

towards our subsistence.

About that time, and on Easter-day that year, an unfortunate accident

befel M. le Gros. After divine service, he took a gun to go kill snipes

about the fort. He shot one, which fell into a marsh; he took off his

shoes and stockings to fetch it out, and returning, through carelessness

trod upon a rattle-snake, so called, because it has a sort of scale on the

tail, which makes a noise. The serpent bit him a little above the ankle;

he was carefully dressed and looked after, yet after having endured very

much, he died at last, as I shall mention in its place. Another more

unlucky accident befel us, one of our fishermen swimming about the net to

gather the fish, was carried away by the current, and could not be helped

by us.

Our men sometimes went about several little salt water lakes, that

were near our fort, and found on the banks a sort of flat fishes, like

turbots, asleep, which they struck with sharp pointed sticks, and they

were good food. Providence also showed us that there was salt made by the

sun, upon several little salt water pools there were in divers places, for

having observed that there grew on them a sort of white substance, like

the cream upon milk, I took care every day to send and fetch that scum

off, which proved to be a very white and good salt, whereof I gathered a

quantity, and it did us good service.

Some of our hunters having seen a parcel of wild goats running as if

they were frighted, judged they were pursued by the Indians,

and came for refuge to the fort, and to give me notice. Accordingly some

time after, we discovered a parcel of natives, who came and posted

themselves on an eminence, within cannon shot; some of them drew off from

the rest, and approached the fort by the way of the downs. I caused our

men immediately to handle their arms, and wet blankets to be laid on our

huts, to prevent their being burnt by the fire the savages sometimes shoot

with their arrows. All this time those who had separated themselves from

the rest, being three in number, still drew nearer, making signs for us to

go to them; but M. de la Salle had forbidden me having any commerce with

them; however, since they had neither bows nor arrows, we made signs to

them to draw near, which they did without hesitating.

We went out to meet them, M. Moranget made them sit down, and they

gave us to understand by signs, that their people were hunting near us;

being able to make no more of what they said, M. Moranget was for knocking

out their brains, to revenge their having murdered our companions, but I

would not consent to it, since they had come confiding in us. I made

signs to them to be gone, which they did as fast as they could, some small

shot we fired into the air making them run, and a cannon shot, I pointed

towards the rising ground, where the rest were, put them all to flight.

These accidents made us double our guards, since we were at open war

with that crafty nation, which let slip no opportunity to surprise us, and

therefore penalties were appointed for such as should be found asleep upon

sentinel; the wooden-horse was set up for them without remission; and by

means of such precautions we saved our lives.

Thus we spent the rest of the month, till the beginning of June. In

the meantime, M. de la Salle had begun to make another settlement, in the

place he before told us of, looking upon it as better, because it was

further up the country. To that purpose he sent to us the Sieur de

Villeperdry, with two canoes and orders for the Sieur Moranget to repair

to him, if he were recovered, and that all the men should march, except

thirty of the ablest to make a good defence, who were to stay with me in

the fort. The rest being seventy persons, as well men and women, as

children, set out with the Sieur Moranget; and we being but a small number

remaining, I caused the fort to be brought into a less compass, to save

posting so many sentinels.

Our little company began to take satisfaction in the ease of getting,

and the nature of our provisions, which a greater number has more

difficulty to be supplied with, and which we had plenty of, by means of

hunting and fishing, those being our principal employments, and we lived

well enough contented, expecting to be removed. However, there were some