Louisiana Anthology

William Bonny Glover.

“A History Of Caddo Indians.”

PREFACE

PREFACE

In a study of the history of Caddo Parish, Louisiana, an interest

was developed in the Caddo Indians who were aborigines of the parish, and

since no adequate study had been made of these interesting people it became

my purpose to give an account of them from the time when first met by the

white man until about 1845.

The region inhabited by the Caddo Indians when they were first

met by the whites, soon became the disputed territory between France and

Spain, and later between Spain and the United States. From the outset the

Caddoes were border Indians, therefore their relations with the Europeans

and later with the Americans were somewhat different from that of tribes

inhabiting undisputed territory. Because of the strategic importance of

the Caddo country, each of the different nations under whose jurisdiction

the natives lived, employed certain methods in dealing with them. Often

in order to maintain control of the natives, the nations involved in controversy

made a complete change in their policy and these policies had a decided

influence on the Indians.

Inasmuch as the native background as expressed in customs, traditions,

and location affected the general relations of the natives with the white

man it seems necessary to put together such in formation as is available

concerning the tribes for the period be fore the white man came into their

territory. The available in formation came largely through reports made

by the French and Spanish who first came in contact with these Indians.

Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University

of Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master

of Arts,

August, 1932.

Among those who have given me help in the preparation of this

work I wish to thank Miss Harriet Smither, archivist of the Texas State

Library, and I am especially grateful to Mrs. Mattie Austin Hatcher and

Miss Winnie Allen of the University of Texas Library staff for their kindness

and helpfulness in making avail able the materials of the library.

To Dr. William Campbell Binkley of Vanderbilt University, I

wish to express my gratitude for his scholarly advice and helpful criticisms

during the development of this study.

Note: Because of the ancient origin of this text, certain

words may appear mispelled; They are not; and some usage may appear awkward.

The seemingly mispelled words and strange useage are from the original

text "as is" and are not changed to modern spelling and usege.

|

|

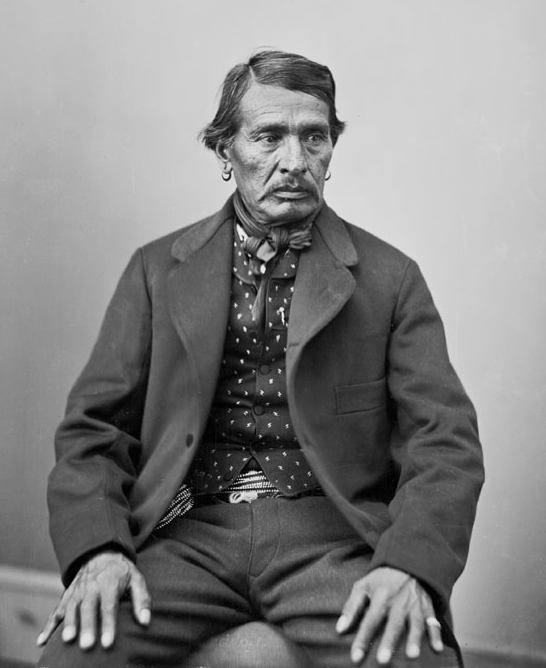

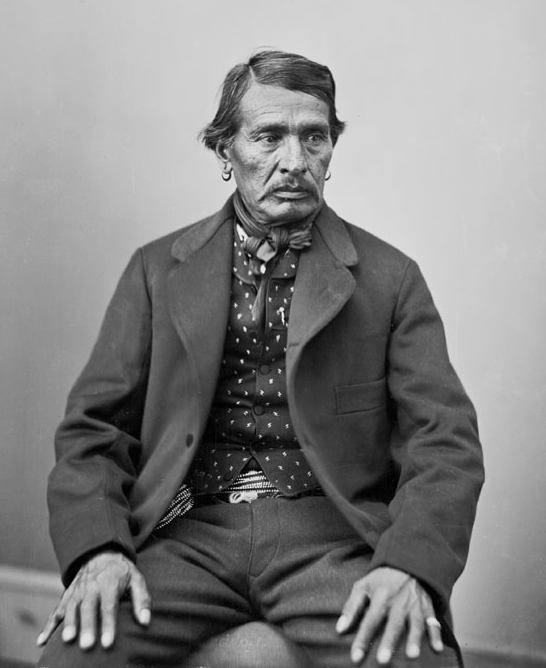

Sho-e-tat (Little Boy) or George Washington (1816-1883).

Louisiana Caddo leader.

|

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER I

EARLY HISTORY OF THE CADDO

1. Sketch of the Tribes

The Caddo Indians are the principal southern representatives of the

great Caddoan linguistic family, which include the Wichita, Kichai, Pawnee,

and Arikara. Their confederacy consisted of several tribes or divisions,

claiming as their original territory the whole of lower Red River and adjacent

country in Louisiana, eastern Texas, and Southern Arkansas.

Caddo is a popular name contracted from Kadohadacho, the name of the

Caddo proper, as used by themselves. It is extended by the whites to include

the Confederacy. Most of the early writers, and even many of the later

ones used different names for the Kadohadacho. Chevalier de Tonti, a French

explorer, called them Cadadoquis, M. Joutel, historian for La Salle's exploring

party, called them Cadaquis, and John Sibley, Indian agent at Natchitoches,

called them Caddoes. They were called Masep by the Kiowa, Nashonet or Nashoni

by the Commanche, Dashai by the Wichita, Otasitaniuw (meaning "pierced

nose people") by the Cheyenne, and Tanibanen by the Arapaho.

The number of tribes formerly included in the Caddo Confederacy can

not now be determined. Only a small number of the Caddo survive, and the

memory of much of their tribal organization is lost. In 1699 Iberville

obtained from his Taensa Indian guide a list of eight divisions; Linares

in 1716 gave the names of eleven; Gatschet procured from a Caddo Indian

in 1882 the names of twelve divisions, and the list was revised in 1896,

by Mooney, as follows: Kadohadacho (Caddo Proper), Nadako (Anadarko), Hainai

(Ioni), Nabaidacho (Nabedache), Nakohodotsi (Nacogdoches), Nashitosh (Natchitoches),

Nakanawan, Haiish (Eyeish, Aliche, Aes), Yatasi, Hadaii (Adai, Adaize),

Imaha, a small band of Kwaps, and Yowani, a band of Choctaw. A more recent

study by Dr. Herbert E. Bolton, of the University of California, reveals

the fact that there were two confederacies of the Caddoan linguistic stock

inhabiting northeastern Texas, in stead of one, as indicated by Mooney

and Fletcher. Bolton says that the Caddo whose culture was similar to the

Hasinai, lived along both banks of the Red River from the lower Natchitoches

tribe, in the vicinity of the present Louisiana city of that name, to the

Natsoos and Nassonites tribes, above the great bend of the Red River in

southwestern Arkansas and southeastern Oklahoma. The best known members

of this group were the Cadodacho Grand Cado, or Caddo proper, Petit Cado,

upper and lower Natchitoches, Adaes, Yatasi, Nassonites, and Natsoos. On

the Angelina and upper Neches rivers, lived the Hasinai, that comprised

some ten or more tribes, of which the best known were the Hainai, Nacogdoche,

Nabedache, Nasoni, and Nadaco.

Of the names mentioned by the different writers nine tribes named by

Mooney in his list are found under varying forms in the lists of 1699,

by Iberville, and 1716, by Linares. It will be noticed from the above lists

that both Mooney and Bolton included the Cadodacho, Natchitoches, Yatasi,

and Adai in the Caddo Con federacy. It appears from the evidence at hand

that during the eighteenth century two confederacies existed instead of

one as indicated by Mooney. In this paper the Yatasi, Adai, Natchitoches,

Natsoos, Nassonites, and Cadodacho will be considered as the tribes that

belonged to the Caddo Confederacy.

It is impossible at the present time to identify all the tribes that

belonged to the Caddo Confederacy, but a sketch of the best known tribes

that inhabited the Louisiana territory will be under taken. The Natchitoches

lived on Red River, near the present city of Natchitoches, Louisiana. Whether

the army of De Soto came in contact with them is unknown, but the companions

of La Salle, after his death, traversed their country, and Douay speaks

of them as a powerful nation." In 1730 according to Du Pratz, the Natchitoches

villages near the trading post at Natchitoche numbered about two hundred

cabins. The population rapidly declined as a result of the wars in which

they were forced to take part, and the introduction of new diseases, particularly

small pox and measles.

In 1805 Dr. John Sibley, Indian agent at Natchitoches, in a report to

Thomas Jefferson relative to the Indian tribes in his territory said:

There is now remaining of the Natchitoches but twelve men and nineteen

women, who live in a village about twenty five miles by land above the

town which bears their name near the lake, called by the French Lac de

Muire. Their original language is the same as the Yattassee, but speak

Caddo, and most of them French.

The French inhabitants have great respect for this nation, and a

number of very decent families have a mixture of their blood in them. They

claim but a small tract of land, on which they live, and I am informed,

have the same rights to it from Government, that other inhabitants in their

neighborhood have. They are gradually wasting away; the small pox has been

their great destroyer. They still preserve their Indian dress and habits;

raise corn and those vegetables common in their neighborhood.

The Yatasi tribe is first spoken of by Tonti, who states that in 1690

their village was on the Red River, northwest of Natchitoches. In the first

part of the eighteenth century, St. Denis invited them to locate near Natchitoches,

in order that they might be protected from the attacks of the Chickasaw

who were then waging war along Red River. A part of the tribe moved near

Natchitoches, while others migrated up the river to the Kadohadacho and

to the Nanatsoho and the Nasoni.

At a later date the Yatasi must have returned to their old village site.

John Sibley, in a report from Natchitoches, states that they lived on Bayou

River (Stony Creek), which falls into Red River, Western division, about

fifty miles above Natchitoches. According to Sibley's report they settled

in a large prairie, about half way between the Caddoques (Cadodacho) and

the Natchitoches, surrounded by a settlement of French families. Of the

ancient Yattassees (Yatasi) there were then but eight men and twenty-five

women remaining. Their original language differed from any others, but

all of them spoke Caddo. They lived on rich land, raised plenty of corn,

beans, pumpkins, and tobacco. They also owned horses, cattle, hogs, and

poultry.

The Adai village was located on a small creek near the present town

of Robeline, Louisiana, about twenty-five miles west of Natchitoches. This

was also the site of the Spanish Mission, Los Adaes. The first historical

mention of the Adai was made by Cabeca de Vaca, who in his "Naufragios",

referring to his stay in Texas, about 1530, called them

Atayos.

Mention

was also made of them by Iberville, Joutel, and some other early French

explorers. In 1792 there was a partial emigration of the Adai, numbering

fourteen families, to a site south of San Antonio de Pejar, southwest Texas,

where it is thought they blended with the surrounding Indian population.

The Adai who were left in their old homes at Adayes, numbered about one

hundred in 1802. According to John Sibley's report in 1805 there were only

twenty men of them remaining, but more women than men. Their language differed

from that of all other tribes and was very difficult to speak, or understand.

They all spoke Caddo, and most of them spoke French also. They had a strong

attachment to the French, as is shown by the fact that they joined them

in war against the Natchez Indians.

The Cadodacho (real Caddo, Caddo proper), seem to have lived as a tribe

on Red River of Louisiana from time immemorial. According to tribal traditions

the lower Red River of Louisiana was their original home, from which they

migrated west and northwest. Penicaut reported in 1701 that the Caddo lived

on the Sabloniere, or Red River, about one hundred and seventy leagues

above Natchitoches, which places them a little above the big bend of Red

River near the present towns of Fulton, Arkansas, and Texarkana. In 1800

the Caddo moved down the Red River near Caddo Lake, which placed them about

one hundred and twenty miles from the present town of Natchitoches. Sibley

says:

They formerly lived on the south bank of the river, by the course

of the river 376 miles higher up, at a beautiful prairie, which has a clear

lake of good water in the middle of it, surrounded by a pleasant and fertile

country, which had been the residence of their ancestors for time immemorial.

They have a traditionary tale, which not only the Caddoes, but half a dozen

other smaller nations believe in, who claim the honor of being descendants

of the same family; they say, when all the world was drowning by a flood,

that inundated the whole country, the Great Spirit placed on an eminence,

near this lake, one family of Caddoques, who alone were saved; from that

family all the Indians originated.

In 1719 the Assonites (Nassonites), and Natsoos, dwelt along Red River,

often on both sides of the channel about one hundred and fifty leagues

northwest of Natchitoches. They lived near the Cadodacho and were related

to them.

The Cadodacho was the leading tribe in the Caddo Confederacy. This nation

wielded a great influence over many of the tribes belonging to the Southern

Caddoan family. In 1805 their influence extended over the Yatasi, Nandakoes,

Nebadaches, Inies, or Tackies, Nacogdoches, Keychies, Adai, and Natchitoches,

who looked up to them as their father, visited and intermarried among them,

and joined them in all their wars.

It is impossible to determine with exactness the population of the Caddo

during the early period, for no record of a census is available until after

the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Fletcher says that before the coming of

the French and Spanish they were no doubt a thrifty and numerous people.

One writer states that during their early history they must have numbered

about ten thousand. No doubt this estimate included both the Caddo and

Hasinai Confederacies. According to a report from the Indian agent at Natchitoches

made in 1805 the tribes of the Caddo confederacy at that time numbered

approximately six hundred, not including children.

All the tribes of the Confederacy spoke the Caddoan language. However,

the language of the Adai differed from all the others and was very difficult

to speak. The Caddoes had a very convenient way of communicating with each

other and with other tribes, through the medium of a sign language. Their

tribal sign was made "by passing the extended index finger, pointing under

the nose from right to left." When they wanted to accuse some one of telling

a lie, or falsehood, they did that "by passing the extended index and second

fingers separated toward the left, over the mouth".

2. The Manners and Customs of the Caddo

The Caddoes were cultivators of the soil. They planted fields around

their villages in corn, pumpkins and vegetables that furnished their staple

food. They would not allow idleness; there was always something to be done,

and those who would not work were punished. They worked hard in their fields

when the weather was good, but when the cold rain fell and the north wind

blew they would not come out of their houses. Yet they were not idle; they

sat around the fire employing themselves with handiwork. It was then that

they made their bows and arrows, their necessary clothing and tools with

which to work. The women worked making mats out of reeds and leaves, and

pots and bowls out of clay.

Joutel gives an interesting account of the agriculture of the Caddo

tribes in his day. He says:

I noticed a very good method in this nation (Cenis), which is to

form a sort of assembly when they want to turn the soil in the fields belonging

to a certain cabin, an assembly in which may be found more than a hundred

per sons of both sexes. When the day has been appointed, all those who

were notified come to work with a kind of Mattock made of a buffalo's shoulder-l:

lade, and some of a piece of wood, hafted with the aid of cords made of

the bark of trees. While the workers labor, the women of the cabin for

which the work is being done, take pains to prepared food; when they have

worked for a time, that is, about midday, they quit, and the women serve

them the best they have. When someone coming in from the hunt brings meat,

it serves for the feast; if there is none, they bake Indian bread in the

ashes, or boil it, mixing it with beans, which is not a very good dish,

but it is their custom. They envelop the bread that they boil with the

leaves of the corn. After the repast, the greater part amuse themselves

the rest of the day, so that, when they have worked for one cabin, they

go the next day to another. The women of the cabin have to plant the corn,

beans, and other things, as the men do not occupy themselves with this

work. These Indians have no iron tools, so they can only scratch the ground,

and can not pick it deep; nevertheless, everything grows there marvelously.

The Caddo also hunted and fished for a living. M. de la Harpe mentions

the fact that the Cadodaquious (Cadodacho) and their associates prepared

a feast for him which included among other things, the meat of bear, buffalo,

and fish. Another evidence that they fished and hunted for a living, was

brought to light by Harrington, field worker for the Heye foundation, in

excavations made near Fulton, Arkansas, in the old Caddo villages. In their

digging they found the bones of deer, raccoons, turkeys, and many other

creatures, mixed with the ashes of ancient camp fires, showing that hunting

was one of their principal means of gaining a livelihood. They also found

fish and turtle bones and stone sinkers for nets, all of which indicated

that they used fishing as another means of making a living.

The tribal organization among the Caddo was similar to that of the Hasinai.

Fortunately, Father Jesus Maria left a good account of the Tejas or Aseney

(Hasinai) tribes. Each group of the Tejas Indians was apparently under

the command of a great chief called Xinesi. Each tribe had a chief or governor

called a Caddi, who ruled within the section of country occupied by his

tribe, no matter whether it was large or small. If large, they had a sub-chief

called Canahas. The number of sub-chiefs depended on the size of the tribe

ruled by the Caddi. The number ranged from three to eight. It was their

duty to relieve the Caddi and to publish his orders. One of these gave

orders for preparing the chief's sleeping place while on the buffalo hunt

and the war-path, and filled and lighted his pipe for him. They also frightened

the people by declaring that, if they did not obey orders, they would be

whipped and punished in other ways. There were other sub ordinate officers

called Chayas, who carried out orders issued by the Canahas. There were

petty officers under the Chayas, called jaumas, who promptly executed orders.

They whipped all the idlers with rods, by giving them strokes over the

legs and belly. When the Caddi wished to have a council meeting, the Canahas

had to summon the elders. This organization must have worked well, for

Father Jesus Maria states that during his stay of one year and three months

among them he had not heard any quarrels. It is certain from the evidence

at hand that their life was more or less communal, for we are told that

eight or ten families often lived in one dwelling, and cultivated the land

about it in common. It appears that the food supply was kept in common,

for Joutel says:

The mistress, who must have been the mother of the chief, for she was

aged, had charge of all the provisions, for that is the custom, that in

each cabin, one woman holds supremacy over the supplies, and makes the

distribution to each, although there may be several families in the cabin.

We are told by Jesus Maria that if the house and property of one of

the tribesman were destroyed, all the rest of the tribe joined in helping

provide him with a new home. This communistic practice was common among

the early white settlers, and will be found among the farmers in the rural

sections of Louisiana today.

The Caddo lived in two kinds of houses, the grass thatched, and earth

covered. The grass houses were conical in shape, made of a framework of

poles covered with a thatch of grass. They were grouped around an open

space which served for social and ceremonial purposes. Arranged around

the walls inside of the house were couches covered with mats, that served

as seats during the day and as beds at night. In the middle of the house

was the fire, which was kept burning day and night.

The earth houses were erected by constructing a frame, probably in the

form of a low dome of very stout poles upon which were placed smaller ones

at right angles. These in turn were covered with brush and cane, and then

with sage grass on which was placed a heavy coating of earth.

The Caddoes wore very few clothes during the early period as reported

by Joutel. During the winter months they covered themselves with animal

skins. They hung these skins around their bodies reaching about half way

down their legs. During the warm months nearly all of them went without

clothing.

They loved ornaments such as beads, ear-pendants, and ear plugs. Father

Jesus Maria states that at festive times they did not lack for ornaments

such as collars, necklaces, and amulets, which resembled those the Aztecs

wore, with the one difference that the Tejas Indians knew nothing of gold

and silver.

If a man wanted to marry, he took the maiden of his choice the best

and finest present he could afford. If the father and mother gave their

permission for her to receive the gift, it meant that the man had their

consent to take her. However, she was not taken away until notice was given

to the Caddi. If the woman was not a maiden, all that was necessary was

her consent to receive the presents. Often the agreement was made only

for a few days. At other times they declared it binding forever. Only a

few of them kept their word. When a woman found another man who was able

to give her better things she went with him and there was no punishment

for this conduct. Few men ever remained with their wives very long, but

they never had but one wife at a time.

Another custom of interest among the Hasinai was the war dance. Before

going to war they usually sang and danced for seven or eight days, offering

to their God such things as corn, tobacco, bows, and arrows. Each offering

was hung on a pole in front of the place where they were dancing, and near

the pole was a fire before which stood a wicked-looking person who made

the offering of incense by casting tobacco and buffalo fat into the fire.

Each man gathered around the fire collected smoke and rubbed his body with

it, believing that by performing this ceremony his God would give him whatever

he requested. They prayed to nature, and to the animals for courage and

strength to defeat the enemy. They asked the water to drown their enemies,

the fire to burn them, the arrows to kill them, and the wind to blow them

away. On the last day the Caddi came forward and encouraged the men by

telling them that if they really were men, they must think of the wives,

their parents, their children, but not to let them be a handicap to their

victory. Ethnologists agree that the Caddoes follow nearly the same mode

of burial as the Wichitas.

When a Wichita dies the town crier goes up and down through the village

and announces the fact. Preparations are immediately made for the burial,

and the body is taken without delay to the grave prepared for its reception.

If the grave is some distance from the village, the body is carried thither

on the back of a pony, being first wrapped in blankets and then laid prone

across the saddle, one person walking on either side to support it. The

grave is dug from three to four feet deep and long enough for the body.

First blankets and buffalo robes are laid in the bottom of the grave, then

the body, being taken from the horse and unwrapped, is dressed in its best

apparel and with ornaments is placed upon a couch of blankets and robes,

with the head toward the west and the feet to the east; the valuables belonging

to the deceased are placed with the body in the grave. With the man are

deposited his bows and arrows or gun, and with the woman her cooking utensils

and other implements of her toil. Over the body sticks are placed six or

eight inches deep and grass over these, so that when the earth is filled

in, it need not come in contact with the body or its trappings. After the

grave is filled with earth, a pen of poles is built around it as a protection

from the wild animals. The ground on and around the grave is left smooth

and clean.

If a Caddo is killed in battle, the body is never buried, but left to

be devoured by beasts or birds of prey, and the condition of such individuals

in the other world is considered to be far better than that of persons

dying a natural death. This practice resembles that of the ancient Persians

who threw out the bodies of their dead on the roads, and if they were promptly

devoured by wild beasts they esteemed it a great honor, and if not, a terrible

misfortune.

Not much is known about the religious beliefs of the Caddo, but the

early writers tell us that they believed in a "great spirit," known under

the name of Ayanat Caddi, or as Ayo-Caddi-Aymay. Manzanet says that their

ceremonial leader "had a house reserved for the sacrifices, and when they

entered therein they behaved very reverently, particularly during a sacrifice.

They never sacrificed to idols, but only to him of whom they said that

he has all power, and that from him came all things. Ayimat Caddi, in their

language, signifies the great captain. This was the name he gave to God.

In spite of these remarks there is evidence that the Caddo and their relatives

worshipped a number of minor spirits and powers. This may be inferred from

Douay's statement that the Caddo adored the Sun. He says, "Their gala dresses

bear two painted suns; on the rest of the body are representations of buffalo,

stags, serpents, and other animals." Harrington says, "it even appears

that they thought everything in nature had some sort of spirit or power,

which could be prayed to, reasoned with, and led to assist the supplicant,

so they 'solicited the deer and buffalo, that they should allow themselves

to be slain; the maize, that it would grow and let itself be eaten; the

air, that it would be pleasant and healthful.

3. The Caddo Country and Range

According to a tradition of the Caddo which has parallels among other

tribes, their original home was on lower Red River in Louisiana. The story

says that they came up from under the ground through the mouth of a cave

on a lake close to the south bank of Red River, just at its junction with

the Mississippi. From this place they spread out toward the west, following

up the course of Red River, along which they made their principal settlements.

Bolton states that during the eighteenth century they extended along both

banks of the Red River from the present city of Natchitoches, Louisiana,

to the Natsoos and Nassonites tribes, above the great bend of the Red River

in southwestern Arkansas and southeastern Oklahoma.

No definite boundary lines can be given for the territory claimed by

the Caddo previous to eighteen hundred. Good authority establishes the

fact that they claimed a very extensive tract of country on both sides

of Red River extending from the present city of Shreveport to the cross

timber, a remarkable tract of woodland, which crosses Red River more than

a thousand miles above its mouth. This tract of country claimed by the

Caddo was one of the finest sections within the bounds of North America.

The topography of the country made it suitable for agriculture, stock

raising, fishing, and hunting. The Caddo uplands are marked by numerous

bayous and lakes and are undoubtedly excellent in quality. The river lands

are of the richest alluvial soil and of wonderful fertility. The soil of

the valley in many places is a black, deep soil of unsurpassed fertility.

At intervals along the Red River from Shreveport to the timber line there

are numerous lakes and spring-brooks, flowing over a fertile soil, here

and there interspersed with glades and small prairies, affording a fine

range for the wild animals that inhabited the Indians' happy hunting ground.

The range of the Caddo was far beyond the territory that they claimed.

It undoubtedly extended east from the Red River near the present city of

Shreveport to the Ouachita River, and north to the Arkansas River, northwest

to the source of the Red River and west to the Sabine River.

Since the Caddo hunted, traded, and often went to war with adjacent

tribes, it appears necessary at this time to give a sketch of the tribes

bordering on the territory claimed by the Caddo. To the west and southwest

of the Caddo on the Angelina and upper Neches rivers lived the Hasinai

Confederacy, that comprised some ten or more tribes, of which the best

known were the Hainai, Nacogdoche, Nabedache, Nasoni, and Nadaco. They

were a settled people, who had been living in the same region certainly

since the time of La Salle, and probably long before. They dwelt in scattered

villages, practiced agriculture to a great extent, and hunted buffalo on

the western prairies. In manners, customs, and social organization the

tribes of the confederacy were similar to those of the Caddo.

The Wichita, comprising another group of the Caddoan tribes, lived northwest

of the Caddo, on the upper Red, Brazos, and Trinity Rivers. They were known

to the Spaniards of New Mexico as Jumano and to the French as Panipiquet

or Panis. They are now collectively called by ethnologists the Wichita.

The civilization of the Wichita was essentially like that of the

Caddo and the Hasinai, though they were more war like, less fixed in their

habitat, and more barbarous, even practicing cannibalism extensively.

The Arkansas (Quapaw) lived north of the Caddo on the south side of

the Arkansas River about twelve miles above the Arkansas post. They claimed

all the land along the river for about three hundred miles above them.

They were friendly with the Caddo tribes, but at war with the Osage who

lived farther up the river. They were active tillers of the soil, and also

made pottery of the finest design.

East of the Caddo across Red River on Bayou Chicot was a Choctaw village.

Marshall says that as early as 1763, and perhaps earlier, some of the Choctaw

left their homes in Mississippi and Georgia, and migrated west of the Mississippi

where they evidently encroached upon the Caddo, for in 1780 some of them

were at war with that nation."

These are the principal tribes and confederacies found along the borders

of the territory claimed by the Caddo Indians during the eighteenth century.

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER II

CADDO RELATIONS WITH THE FRENCH AND SPANISH

1. French and Spanish Relations before 1762

In order to understand the history of the Caddo Indians it is not only

necessary to have a knowledge of their traditions, customs, and location

but also to know something about their relations with the Europeans. The

Caddo was one of the groups located on the frontier between Louisiana and

New Spain.

France and Spain began a contest to control these frontier tribes from

the first moment of contact until 1762 when Louisiana was ceded to Spain.

The principal weapon used by the French was the trader, and by the Spaniards,

the Franciscan missionary, each backed by a small display of military force.

One of the reasons for a desire to control the frontier tribes was to secure

possession of their territory. Both France and Spain realized that the

best way to accomplish this was to establish an influence over the natives

of the district desired. Another reason to control the tribes was to foster

trade. A third was a desire of the missionaries to bring them to the knowledge

of the Christian faith.

From the outset both the French and Spanish governments regarded the

Caddo country as a strategic point of great importance. Likewise, both

countries began to make a bid for control of the individual tribes before

the close of the seventeenth century. The first contact made by the French

was with the Cadodacho who were visited by the survivors of the La Salle

party in 1687, and the friendly relations established by this visit were

never abandoned. In 1689 Tonti, while searching for La Salle's colony,

visited the tribe and further strengthened the amicable relations already

existing between them and the French.

The first Spanish explorer to reach the Cadodacho country was Domingo

Teran. His attempt to explore the region was a complete failure and it

was not until 1717 when another unsuccessful attempt was made by Father

Margil to establish missions for the Cadodacho and the Yatasi.

In 1718 a large grant of land was made to Bernard de la Harpe, a French

colonizer, in the Cadodacho country. In 1719 a garrisoned trading post

was established on Red River by La Harpe between the Cadodacho and Nassonite

villages. This post was maintained part of the time with a garrison until

after the Louisiana cession. It checkmated every attempt made by the Spaniards

to penetrate the Cadodacho country. Later, depots were established at the

village of the Petit Cados and Yatasi.

Bolton says:

These trading establishments at Natchitoches and in the villages

of the Cadodacho, Petit Cado, and Yatasi, together with the influence of

the remarkable St. Denis, who in 1722 became commander at Natchitoches,

and who till his death in 1744 remained the master genius of the frontier,

were the basis of an almost undisputed French domination over the Caddo

tribes. More than once the Spanish authorities contemplated driving the

French out of the Cadodacho village and erecting there a Spanish post,

but each attempt failed.

The first relations with the Natchitoches began in 1690 when Tonti reached

these tribes from the Mississippi and made an alliance with them. In 1700

Iberville sent his brother, Bienville, on a visit to their country from

the Taensa villages. Bienville as an ambassador must have accomplished

his ultimate aim, for, from the date of his visit to the close of the eighteenth

century the tribe never broke faith with the French. In 1712 they helped

St. Denis establish a post on the Red River at Natchitoches as a protection

against the intrusions of the Spanish, and also in the hope of establishing

trade relations with Spain.

In 1701 Bienville and St. Denis visited the Yatasi tribes and made an

alliance with them. That the friendship formed by this alliance was permanent,

was shown by the fact that the Yatasi refused to close the road between

the Spanish province and the Red River settlement, after the Spanish had

demanded that it be closed.

The French maintained control over all of the Caddo tribes with the

exception of the Adai, among whom the Spanish were located from the very

beginning. In 1715 Domingo Ramon, a Spanish colonizer, with a company of

Franciscans, made settlements in the Adai territory. The mission of San

Miguel de Linares was founded among them in 1716.

In 1719, when France and Spain were at war, orders were given to Blondel,

the commandant at Natchitoches, to drive the Spaniards from Texas. In carrying

out these orders Blondel, with Natchitoches and Caddo allies, took possession

of Los Adaes, and the Indians were allowed to destroy the buildings. The

Adai tribe because of their allegiance to the Spanish, were removed from

their lands by the French and treated as enemies.

In 1721 the Marquis de Aguayo, a Spanish general, was sent with the

strongest military force that had ever entered Texas to re-establish the

presidios of Texas and the abandoned missions. He established a new presidio

in the Adai tribe beside the Mission of San Miguel. This new presidio was

located where the present town of Robeline, Louisiana, now stands. About

1735 a military post called Nuestra Senora del Pilar was established, and

five years later this garrison became the Presidio de los Adayes. Afterwards,

when the country was districted for the jurisdiction of the Indians, the

Adai tribe was placed under the division having its official headquarters

at Nacogdoches. Although Spain had established the political rule over

the Adai, she had not stopped the French trade that had won the hearts

of the natives. These Indians and associated tribes along the frontier

looked to the French for their weapons, ammunition, and other articles

of trade, for which they exchanged their peltry, and often their agricultural

products.

As a result of the wars between France and Spain the Adai had suffered

severely, one portion of their villages being under French control, the

other being under Spanish control. The ancient trail between their villages

became the noted "contraband trail" along which traders and travelers journeyed

between the French and Spanish provinces. One of their villages was on

the road between the French fort at Natchitoches and the Spanish fort at

San Antonio. The adverse influences of the whites, together with the conflict

between France and Spain, almost exterminated this ancient tribe of Indians.

2. The Spanish Indian Policy after 1762

From this time the Caddo tribes were under Spanish control; therefore

the outcome of the Indians will be largely determined by the Spanish Indian

policy. The three fundamental purposes of the early Spanish policy were

to convert the natives to the Christian faith, to civilize them, and to

use them in the development of the frontier. In order to accomplish these

desires the encomienda system was devised. It was soon learned that before

the savage could be civilized, converted, or made a useful being, he must

first be controlled. To provide such control, the land and Indians were

distributed among the colonizers who held them in trust, or in encomienda.

It was the duty of the trustee to provide for the protection, the conversion,

and the civilization of his subjects; in return he was given the privilege

to exploit them. The encomendero, or guardian, was required to support

friars, whose duty it was to instruct the Indians in the Christian religion,

in citizenship, and in the industrial arts. This plan led to the establishing

of great monasteries in the territory conquered by the Spanish colonizers.

It was also learned that in order to instruct and exploit the Indian

properly, he must be made to remain in a specified place of residence.

Thus it soon became a law that Indians must be congregated in pueblos,

and kept there by force if necessary. The encomienda system was so badly

abused that it placed the Indians in a state of slavery. The trustees,

yielding to the desire of the flesh, thought only of the usefulness of

the natives in terms of dollars and cents. They disregarded the primary

objects for which the system was designed; to convert and civilize the

natives. The encomienda system was gradually replaced by the missions.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries many missions were planted

on the expanding frontiers of Spanish America. These missions were in the

hands of priests whose first duty was to teach the Christian religion to

the heathen, and to teach the Spanish language and civilization. The missionaries

were not only religious agents but they also served as political agents

for Spain. They explored the frontiers, promoted their occupation, de fended

them and the interior settlements from foreign influences and savage tribes,

and often served as diplomatic agents. The Spanish Indian policy prior

to the Louisiana cession, although tinged with mercenary aspirations, was

designed for the preservation of the Indians rather than for their destruction.

In 1762 France ceded Louisiana to Spain but the transaction was not

complete]y carried into effect until 1769.l7 The Indians were very angry

when they learned of the treaty of cession. They did not believe that the

King of France had a right to transfer them to any white or red chief in

the world, and to dispose of them like cattle; thus they threatened resistance

to the execution of the treaty.

Spain now had a new Indian problem. She had the difficult task of winning

the loyalty of the Indian tribes that had been living peaceably under the

influence of the French in the contested territory. The new policy adopted

was similar to that employed by the French, a "method of control," Bolton

says, "Through the fur trades and presents, a good many modifications in

the directions of greater equity for the white men and greater humanity

to ward the natives.

3. Relations with the Spanish after the Louisiana

Cession

After the Louisiana cession Antonio de Ulloa, first Spanish governor

in Louisiana, and Hugo O'Conor, ad interim governor in Texas, issued proclamations

threatening death to any French man trading in Texas. Later, O'Conor claimed

that by this means all such trade was suppressed. Ulloa soon concluded,

however, that the French system of trade and presents for the friendly

Indians must be continued. He reached this conclusion in December, 1767,

after an attempt was made to suppress the trade with the Yatasi tribe.

On his way to the village, Du Buche, a trader who had been stopped by orders

of O'Conor, caused the tribe to rise in rebellion. They held a meeting

and planned to attack one of the Texas presidios, but were deterred by

Guakan, head chief of the Yatasi nation. Guakan was pacified and trade

allowed to continue. French traders were allowed to go freely to the tribes

of Louisiana and Texas without restrictions as to time or place.

When Alexander O'Reilly became governor of Louisiana in 1769, he continued

the trade with the friendly tribes, but attempted to discontinue trade

with the enemies. Athanase de Mezieres, lieutenant governor at Natchitoches,

was instructed by O'Reilly to continue the annual presents to the Cadodacho,

Petit Cado, and Yatasi tribes. De Mezieres was also instructed to choose

traders of good habits to send into the Indian villages and to encourage

the savages to work and not to remain idle. He selected Alexis Grappe,

Dupin, and Fazende Moriere to reside in the villages of the Cadodacho and

Yatasi. The instructions which they were to observe specified that the

savages must be furnished satisfactory merchandise for the ordinary trade

price; no English merchandise should be introduced among the Indians; goods

should be sold and distributed only to friendly nations; the traders should

arrest all French and Spanish wanderers or vagabonds, and confiscate their

effects, demanding, if necessary, the forcible aid of the Indians; the

chiefs were requested to bring such rovers to the post; English traders

should not be allowed to trade with the Indians or even to go into their

villages; they were pledged to maintain peace and harmony among the tribes

allied with Spain; they were to teach the natives to be loyal subjects;

they were to tell the hostile nations that the French and Spanish were

united and if they did not refrain from violence they would be treated

as their cruel enemies; but if they made true signs of repentance they

would be added to their list of allies; it was recommended to the traders

that no adult or infant Indian in danger of death should be without the

blessing of holy baptism.

Traders having been selected, and instructions having been given to

the traders, De Mezieres proceeded to make an agreement with the Caddo

tribes. He informed Tinhiouen, chief of the Cadodacho, and Cocay, chief

of the Yatasi, of their selection as medal chiefs, and arranged for a meeting

at Natchitoches. The chiefs of the Cadodacho and Yatasi met De Mezieres

at Natchitoches on April 21, 1770. They ceded their lands to the king,

agreed to receive the presents and the traders, and to use their influence

in controlling and making peace with the tribes of the north In writing

about this agreement De Mezieres said:

. . . They have ceded him (the King) all proprietorship in the land

which they inhabit, have promised him blind fidelity and obedience, and

have received his royal emblem and his august medal with the very greatest

veneration. They have engaged to aid with their good offices and their

persuasion, in maintaining the general peace, and, in consequence, not

to furnish any arms or munitions of war to the Naytanes, Taovayaches, Tuacanas,

Quitseys, etc.; to employ themselves peaceably in their hunting, both for

their entertainment and for their subsistence; and to arrest and conduct

to this post all coureurs de bois and persons with out occupation whom

they may meet in the future, protesting that they will never forget their

promise, which is just and very conformable to the harangue which has been

brought to them by us, in the name of the captain-general of this province.

. . .

On February 3, 1770, De Mezieres made a contract with Juan Piseros to

furnish the goods for the traders. He was to deliver them at Natchitoches

on a year's credit, and to receive in payment deer skins of good quality

at thirty-five sous apiece, bear's fat at twenty-five sous a pot, and buffalo

hides, good and market able, at ten livres each. Piseros purchased the

goods in New Orleans, and on their arrival at Natchitoches, they were divided

among the licensed traders who had been appointed to distribute them.

In the fall of 1770, De Mezieres went to the village of the Cadodacho,

on the Red River, to undertake the task of winning the friendship of the

nations of the north. On his journey from Natchitoches he passed through

the villages of the Adai, Yatasi, and Petit Cado. The Caciques and principal

men of these villages, gladly accompanied him to the Cadodacho village.

De Mezieres met at the appointed place the chiefs of the Taovayas, Tawakoni,

Yscanis, and Kichai tribes who were hostile to the Spanish and made peace

with them. De Mezieres said, "I am indebted to the Cacique Tinhiouen and

that of the Yatasi, called Cocay, both decorated with his majesty's medals,

and alike devoted to our Dation, for seconding my discourse with forceful

arguments.

In 1779 the first chief of the Cadodacho decided to visit New Orleans.

De Mezieres informed Governor Bernardo de Galvez of the chief's intention

of visiting him. He said:

The first chief of the Cadauz-dakioux, who has never gone down to

that capital, has decided to make this long journey, attracted by your

reputation and moved by the strongest desire to see you and know you. This

Indian (of whom I have had the honor of reporting to you) is friendly,

and is very commendable both because of an inviolable fidelity to us as

well as by reason of a courage which never fails. It is to him principally

that we owe in this district a constant barrier against the incursions

of the Osages; moreover, it is to the love and respect which the villages

of the surrounding district show him that we owe the fact that they generally

entertain the same sentiments for us. . . . As the Cadaudakious nation is

very much enfeebled by the continual war of the Osages, and since the last

epidemic has still more diminished its numbers, it has created a faction

amongst them who desire to abandon the great village. This would leave

the interior of the country exposed to incursions of foreigners and its

Indian enemies, a design so fatal that it will not succeed if Monsieur

the Governor uses his prodigious influence to frustrate it. . . . The medal

chief being accompanied by all the principal men of the nation. . . it will

be well for your Lordship to treat them kindly, and to recommend them to

love both our nation and their chief. . . . Since many hunters of the Arkansas

River are introducing themselves among the Cadaudakioux, to the prejudice

of their creditors; I pray your Lordship to remedy this abuse by intimating

to the medal chief not to receive them in the future, and even to force

them to appear in this post, because this sort of hunters, seeking only

to flatter the Indians, very often give them very bad impressions. . . .

Your Lordship will make known how interested you are in maintaining peace

among the Caddodoukioux, the Arkan as, and other allies.

On June 1, 1779, Galvez replied to De Mezieres' letter as follows:

The head chief of the Cados nation who came to this capitol to visit

me, I received with all the affection and kindness merited by the fidelity,

love, and other qualities which you indicate, I keeping in mind in the

conversation which I had with him, everything which you suggested to me;

and after remaining here some days he returned to his country with a present

of considerable importance which I gave him, and decorated with the large

medal.

The Caddo tribes were satisfied with the new Spanish Indian policy as

advocated and put into operation by De Mezieres. They were loyal to the

Spanish government, and served faithfully to maintain peace at all times.

The Spanish had won their support by making money and presents the basis

of all negotiations with them.

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER III

THE CADDO IN LOUISIANA, 1803-1835

In 1803 the Caddo Indians after having been under the jurisdiction of

the French and Spanish for nearly a century passed under the yoke of American

domination. The French, who were the first whites to come in contact with

the Caddo, had controlled them from the first quarter of the eighteenth

century until Spain actually took possession of Louisiana in 1768. The

Spanish exercised control over them until the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

At the time of this transaction the Caddoes were living in the same territory

that they had inhabited when first met by the white man. The different

tribes of the confederacy had wandered up and down Red River at different

periods, and finally during the first quarter of the nineteenth century

consolidated in the Sodo Creek region in the present state of Louisiana.

1. Migration of the Cadodacho and Amalgamation of

the Tribes

During the last quarter of the eighteenth century the Cadodacho abandoned

their villages in the prairies along the great bend in Red River, descended

the river, and settled about thirty-five miles west of the main branch

of Red River, on a bayou, called by them, Sodo. The new settlement was

about one hundred and twenty miles by land in nearly a northwest direction

from Natchitoches. They were driven from their old homes by the Osages

who were constantly making excursions into their territory, killing their

warriors, and stealing their horses.

The land on which they now lived was a prairie of a white clay soil.

The country around them was hilly, covered with a growth of oak, hickory,

and pine trees, interspersed with prairies of a rich soil, very suitable

for cultivation. They raised corn, beans, and pumpkins, as they had done

in their old villages.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century the importance of the Cadodacho

as a distinct tribe was at an end; the people be came merged with the other

tribes of the confederacy and shared their misfortune. In 1776 De Mezieres

recommended that presents no longer be given to the Natchitoches and Yatasi

tribes, since they had disbanded and scattered among other bands. In 1805

the Natchitoches numbered fifty. Shortly afterwards, they ceased to exist

as a distinct tribe, having been completely amalgamated with the other

tribes of the Caddo Confederacy. The Yatasi tribe was practically destroyed

by the wars and new diseases of the eighteenth century. These had such

an effect on the Yatasi that by 1805, according to Sibley, they had been

reduced to eight men and twenty women and children. They, too, merged with

the other members of the Caddo Confederacy. All of the Adai, Natsoos, and

Nasonnites disappeared as distinct tribes by the close of the eighteenth

century. The Adai were absorbed by the Caddo, and it is thought the Natsoos,

and Nasonnites were also merged with their kindred. By the close of the

eighteenth century with the exception of a few scattered bands, the Caddo

villages in the vicinity of the present Caddo Parish, Louisiana, represented

the remnants of the old Caddo Confederacy. Tribal wars and diseases had

spread havoc among them, and they, who were once a thrifty and numerous

people had become demoralized and were more or less wanderers in their

native land.

The peaceful Caddoes who had lived under the French and Spanish regimes

soon learned that they were subjects of a new master. Before the Americans

took possession of Louisiana, Sibley reported the Caddoes as anxiously

inquiring about their coming, for their presence meant higher prices for

furs.

2. Caddo Relations with the United States

On February 4, 1804, Edward Turner was given a commission as civil commandant

of the District of Natchitoches. He was placed in full charge of the post

by Governor William C. C. Claiborne. In the letter informing him of his

appointment, Claiborne said, "On the waters of the Red River there reside

two small nations of Indians the Paunies (Panis) and Caddoes, who trade

at the post of Natchitoches. You will receive these people with friendly

attention and have a regard to their interest. No person is to be permitted

to trade with them, who has not been heretofore licensed under the Spanish

Authority, and the period for which such license was granted has not expired,

or who shall not produce a license in writing from myself.

A few months after Captain Turner took charge of the post, he wrote

Governor Claiborne that he had received a visit from the Caddo Indians,

who had said that the Spaniards gave them a present each year, and they

wished the same from the Americans. Turner further stated that he gave

them a few presents that satisfied them temporarily, and promised to let

the chief know later what he could expect in the way of presents. Turner

also suggested that it would not be a wise policy to let the Indians become

dissatisfied, for the Spaniards were exerting every means to induce them

to be unfriendly. On November 3, Claiborne advised Turner to do everything

in his power to gain the good will of the Caddoes and keep them friendly

with the United States. He advised him to furnish rations to the honest,

well disposed Indians that visited the post, but stated that he had not

been authorized to make presents to them generally. He instructed Turner

to give presents to the Caddo chief and his principal men, but these presents

were not to exceed two hundred dollars in value.

While the Caddo Indians were under Spanish control they had been given

presents annually from the post at Natchitoches, and they expected the

American government to continue this system. Inasmuch as the United States

government was making a bid for the control of the Caddo who were again

living within contested territory, it was imperative that it continue the

Spanish policy of giving presents.

In 1803 Turner recommended the immediate establishment of American factories

at Natchitoches to attract the Indians from the Spaniards. Turner and Sibley

informed Claiborne of the privilege enjoyed by Murphy and Davenport in

trading with the Spanish Indians. As this trade included the privilege

of supplying them with ammunition, the Americans, in case of difficulty

with the Spaniards, might feel its evil effects. Accordingly they thought

that if the trade could be turned into the proper channel, and be supplied

from a post on Red River the Indians might be come loyal friends of the

Americans.

In 1804 Sibley was asked by Secretary of War Henry Dear born to act

occasionally as agent for the United States in holding conferences with

the various Indians of his vicinity. He was to keep them friendly toward

the American government by the distribution of some three thousand dollars

worth of merchandise. On May 23, 1805, Secretary Dearborn instructed Sibley

to use all means, at all times, to conciliate the Indians, and especially

those natives that might, in case of a rupture with Spain, be useful, or

mischievous to the government. He said "they may be assured that . . . (they)

will be treated with undeviating friendship as long as they shall conduct

themselves fairly and with good faith to wards the government and the citizens

of the United States."

As Indian agent, Sibley was very active, holding numerous conferences

with the Indians of his territory, and counter acting the efforts of the

Nacogdoches traders to move the Caddo and other friendly Indians into Spanish

territory.

In 1805 Governor Claiborne informed Thomas Jefferson that, in his opinion,

the Indians west of the Mississippi would give them very little trouble.

He said that the Caddo nation had a decided influence over most of the

tribes in lower Louisiana, and they would be easily managed. He stated

also that their disposition toward the United States was already friendly,

and with the proper treatment, he was persuaded their friendship could

be preserved. Sibley in a report to President Jefferson in 1805 said, "The

whole number of what they call Warriors of the Ancient Caddo, is now reduced

to about one hundred, who are looked upon somewhat like Knights of Malta,

or some distinguished military order. They are brave, despise danger or

death, and boast that they have never shed white men's blood." The Caddo

Indians were so brave, peaceful, diplomatic, and influential that it is

not surprising the Spanish officials refused to admit that they lived on

American soil or to give them up without a controversy. On one side of

the border Sibley was working faithfully to keep the Caddoes friendly,

while on the other side Captain-General Salcedo was issuing instructions

to prevent the removal of Indians from Texas into Louisiana, and by every

means possible to keep them faithful to Spanish allegiance. In 1805 from

each group of frontier officials, came accusations against the unfair dealings

of the other in dealing with the Indians in the disputed territory.

The Spanish officials disliked the fact that the Caddoes rendered assistance

to the Freeman-Custis expedition in exploring Red River. They also disliked

the fact that the Caddoes, instead of displaying the Spanish flag in their

villages, had replaced it with an American flag given them by members of

the Freeman-Custis party. The Spanish force sent to stop the Freeman-Custis

exploring party entered the Caddo village, cut down the American flag,

insulted their chief, and threatened to kill the Americans if they resisted

their attempt to stop them. In consequence, Claiborne immediately communicated

with Simon de Herrera, commander of the Spanish troops east of the Sabine

River, saying,

On my arrival at this port, (Natchitoches), I learned with certainty

that a considerable Spanish force had crossed the Sabine, and advanced

within the territory claimed by the United States. It was hoped, Sir, that

pending the negotiations between our respective Governments for an amicable

adjustment of the Limits of Louisiana, that no additional settlement would

be formed, or new Military Positions assumed be (by) either Power, within

the disputed territory; a Policy which a conciliatory disposition would

have suggested and Justice sanctioned; but since a contrary conduct has

been observed on the part of certain officers of his Catholic Majesty,

they alone will be answerable for the consequences which may ensue.

The above proceeding, Sir, is not the only evidence of an unfriendly

disposition which certain officers of Spain have afforded. I have to complain

of the Outrage lately committed by a Detachment of Spanish Troops, acting

under your Instructions, toward Mr. Freeman and his party, who were ascending

the Red River under the Orders of the President of the United States. . . .

Mr. Freeman and his party were assailed by a Battalion of Spanish Troops,

and commanded to return. . . .

This Detachment of Spanish Troops. . . (committed) another outrage, toward

the United States, of which it is my duty to ask an explanation. In the

Caddo Nation of Indians, the Flag of the United States was displayed and

commanded from the chief (and) warriors all the respectful venerations,

to which it is entitled. But your troops are stated to have cut down the

Staff on which the Pavilion waved; and to have menaced the Peace and safety

of the Caddo's should they continue their respect for the American Government,

or their friendly Intercourse with Citizens of the United States.

I experience the more difficulty, in accounting for this transaction,

since it cannot be unknown to your Excellency that while Louisiana appertained

to France, that the Caddo Indians were under the protection of the French

Government, and that a French Garrison was actually established in one

of their villages: hence it follows, Sir, that the cession of Louisiana

to the United States, with the same extent which it had when France possessed

it, is sufficient authority for the display of the American Flag in the

Caddo village, and that the disrespect which that Flag has recently experienced,

subjects your Excellency to a serious responsibility.

On August 28 Herrera replied to Claiborne's letter in part as follows:

"I think as your Excellency does that all the country which his Catholic

Majesty has ceded to France belongs to the United States, but the Caddo's

nation is not upon it and on the contrary the place which they inhabit

is very far from it and be longs to Spain. . . . " Herrera further stated

that he informed the Caddoes that if they wished to continue to live under

the domination of the United States, they would have to pass into their

territory, but if they wanted to remain where they were, they would have

to take down the American colors. On August 31, Claiborne replied to Herrera's

letter, as follows: "You have not denied, Sir, that the French when in

possession of Louisiana, had established a garrison on the Red River, far

beyond the place where Mr. Freeman and his associates were arrested on

their voyage, or that the Caddo Indians were formerly considered as under

the protection of the French Government. The silence of your Excellency

on these points, proceeds probably from a knowledge on your part of the

correctness of my statements." It appears that this letter ended the official

correspondence between Claiborne and the Spanish relative to the control

of the Caddo Indians. It also appears that the American agents were making

progress in their bid for the control of the Caddoes. The Americans were

now put to the task of holding the advantages they had already gained.

Governor Claiborne had invited the chief of the Caddo nation to meet

him in Natchitoches. On September 5, 1806, the grand chief of the Caddoes,

accompanied by twelve or fifteen of his warriors, arrived at Natchitoches,

and on the following day Governor Claiborne, in the presence of the officers

of the army, and many respectable citizens, gave an address to the chief

of the Caddo Nation. In this address he said:

That great and Good Man, the president of the United States esteems

you and your people. Like the rising sun that gives light and comfort to

the world, expands the cares of the American chief, and his desire is to

promote the happiness of all mankind. He is particularly solicitous to

better the condition of his red children; he wishes them to know war no

more; to live in peace with their neighbors; to pursue the deer in safety;

to cultivate their little fields of corn without fear, and that no enemy

should disturb their sleep at night. . . .

Brother! Let your people continue to hold the Americans by the hand

with sincerity and Friendship, and the chain of peace will be bright and

strong, our children will smoke together, and the path will never be colored

with blood. . . .

The talk (at this time) is not straight between the United States

and Spain; but I hope no mischief will ensue, for a council fire is now

burning, and the beloved men of the two nations are endeavoring to settle

the dispute. But if it should so happen that the Americans must bid their

Swords to leap from the scabbard, we wish not your tomahawks to rise. When

white people enter into disputes, let the red men keep quiet, and join

neither side.

Claiborne further told the chief that the Americans and Spaniards were

disputing over the boundary line, and that the Americans purchased the

country from the French and claimed all the land which the French formerly

possessed. He requested the chief to tell what he had heard to the traveler

and to the hunter.

After the ceremonies of smoking the pipe were solemnized, the chief

returned the following answer:

I am highly gratified at meeting today with your Excellency and so

respectable a number of American officers, and shall forever remember the

words you have spoken.

I have heard, before, the words of the President, though not from

his own mouth:-his words are always the same; but what I have this day

heard will cause me to sleep more in peace.

Your words resemble the words my forefathers have told me they used

to receive from the French in ancient times. My ancestors from chief to

chief were always well pleased with the French; they were well received

and well treated by them, when they met to hold talks together, and we

can now say the same of you, our new friends.

If your nation has purchased what the French formerly possessed,

you have purchased the country that we occupy, and we regard you in the

same light as we did them. . . .

This speech from the grand chief of the Caddo nation assured Claiborne

that the United States could rely on the Caddoes being friendly and loyal

subjects.

The Caddo chief acted as ambassador for Sibley to the other Indian tribes

of east Texas and north Louisiana by inviting and conducting a delegation

composed of the head men of seven different nations to a council meeting

at Natchitoches. After the delegation had been seated in the great council

room, and the calumet and council fire had been lighted, Sibley delivered

a talk, and in the course of this talk he said:

By the treaty with France and Spain we have become your neighbors,

and all the great country called Louisiana as formerly claimed by France

belongs to us; the President of the United States is your friend and will

be as long as you are friendly to him; we should live together in peace;

the boundaries between our country and Spain are not yet fixed, but you

may rest assured whether your lands fall within our boundaries or not,

it will always be our wish to be at peace and friendship with you; we are

not at war with Spain, and do not ask you to be unfriendly to Spain; I

caution you against opening your ears to bad talks of any people who wish

to make us enemies, but remember that we have not come to this country

to do harm to any of our Red brothers, but to help them; it is the wish

of your great and good father, the President of the United States, that

you should live together in peace.

Sibley gave presents to the different delegations, and extended them

an invitation to trade at Natchitoches, promising to exchange articles

of merchandise for horses, mules, robes, and silver ore.

During the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain the

allegiance of the Caddoes to the United States was tested. The Creeks who

had attacked the Americans sent war talks to the Caddoes and other tribes

along the Louisiana-Texas frontier endeavoring to stir up an insurrection.

Claiborne, realizing the gravity of the situation, visited Natchitoches

and delivered a war talk to the Caddoes saying that seven years ago they

had held a conference at Natchitoches and had mutually agreed to keep the

path between their two nations white, and he hoped that they and the chiefs

who followed would endeavor to keep the chain of friendship bright and

so strengthen it that their children would live together as neighbors and

friends. He further told them that Doctor Sibley was agent for the president

and whatever he said they should receive as the president's own words.

He reminded them also that seven years ago they had told him they had but

one enemy, the Osages, and he was sorry to learn that they were still at

war with them. He further said, "In the vast hunting grounds where the

great Spirit has placed a sufficiency of Buffalo, Bear and Deer for all

the red men, the Osages, I hear have already robbed the hunters of all

the nations, and their chiefs wage war to acquire more skins." The English,

whom he said were like the Osages, were taking many Americans who were

peacefully navigating the seas, and compelling them to serve on board of

war canoes and fight against their friends and countrymen. Claiborne further

told them that the English were unwilling to fight the Americans man to

man but had appealed to the red people for assistance by telling them lies

and making unfair promises which they would not and could not fulfill.

He warned them that the English would be unable to shield the Creeks whom

they had already incited to acts of hostility against the Americans. In

conclusion he said:

I hear the Creeks have sent runners with war talks, to the Conchattas

and other tribes, your neighbors, but I hope all these people will look

up to you, as an elder brother, and hold fast your good advice. When your

father was a chief, the paths from your Towns to Natchitoches was clean,

and if an Indian struck the people of Natchitoches — It was the same as to

strike him. To a chief, a man and warrior, nothing could be more acceptable

than a sword. . . . I have therefore directed, that a sword be purchased

at New Orleans, and forwarded to Doctor Sibley, who will present it to

you (Caddo Chief) in my name.

Although war talks had been sent to the Caddoes by the Creeks, their

friendship and loyalty could not be shaken in their determination to remain

at peace with the United States.

It appears that Claiborne not only suspected the English of meddling

with the border Indians, but also anticipated trouble again from the Spanish.

On October 21, 1814, he wrote John Perkins, that, according to information

ascertained at Natchitoches, the Spanish authorities of the province of

Texas had made peace with several of the Indian tribes, lately their enemies,

and were again likely to acquire an influence in their councils; also,

it was reported that eight hundred Spanish regulars were advancing toward

Nacogdoches, and no doubt would attempt to occupy the post at Bayou Pierre.

He further added, that in case of an invasion of Louisiana, the Caddo and

other Indian friends would be needed and. . . . "I pray you to keep them

prepared for a prompt cooperation." In a letter to Andrew Jackson, who

was at this time commander of the American forces at New Orleans, Claiborne

said, "The chief of the Caddoes, is a man of great merit, he is brave,

sensible and prudent. -But I advise, that you address a talk immediately

to the chief, he is the most influential Indian on this side of the River

Grande, and his friendship sir, will give much security to the western

frontier of Louisiana."

The Caddoes and other friendly tribes had already informed Sibley that

they were willing to take up arms in defense of their American brothers

and had been ordered by General Jackson to assemble at Natchitoches. Thomas

Gale, late judge advocate of the seventh military district, succeeded Sibley

as Indian agent, and, being a military man, was appointed commander of

the Caddoes, and other Indians assembled at Natchitoches. From further

information it was learned that the Caddoes and other friendly Indians

were held in readiness at Natchitoches to be used against the English,

if needed, or to help maintain peace along the Spanish border.

In 1816 John Jamison was appointed Indian agent at Natchitoches and

was informed by Claiborne that "the policy of the government has been to

keep the Indians at their homes, to guard against those impositions to

which they were exposed by an indiscriminate trade and intercourse with

the whites, to introduce among them, husbandry and the art of civilization,

finally by supplying all their wants to impress them with grateful and

friendly sentiments." After this policy was stated, Jamison was further

instructed to enforce strictly the act of Congress regulating trade and

intercourse with the Indian tribes; to permit no traders to re side among

the Indians, but such as had been licensed according to law; to impress

upon the minds of the Indians the benefit de rived by exclusively trading

with the factory; to discourage and try to prevent the Indians from exchanging

their peltry with the whites for ardent spirits; to prosecute those who

should willfully sell ardent spirits to the Indians; to encourage the tribe

to live in peace with all nations; to protect and treat with kindness not

only their own Indians but individuals of other tribes who lived outside

the bounds of the United States that might visit the agency; to endeavor

to ascertain the policy observed by the Spanish authorities toward the

Indians residing on Red River. It appears that the continued success of

the federal Indian policy among the tribes along the Red River depended

on the enforcement of these regulations, for if the unlicensed traders

were allowed to carry on commerce without restrictions the natives would

soon be looking to them for advice instead of looking to the Indian agents.

In as much as the war Department expected the Indian Agents to enforce

the trade and intercourse laws, and inasmuch as it expected the factories

to supply the goods necessary to keep the Indians friendly and satisfied,

it became necessary to establish agencies nearer the Caddo villages. With

this in mind, George Grey, who had been appointed agent in 1819, established

an agency in 1821 at Sulphur Fork, Red River, in the vicinity of Long prairie.

In 1825 the agency was moved to Caddo prairie and remained there about

six years when, on account of overflows caused by the great raft in Red

River, it was removed below Lodo Lake (Sodo Lake) near the Caddo villages,

only a short distance west of the present city of Shreveport. The agency

remained at this place until the Caddo Treaty in 1835 after which it was

no longer needed and was abolished.

Soon after George Grey became agent he was informed by the Secretary

of War that the law of intercourse should be rigidly enforced against

all white persons trespassing upon the Indians' lands. Those hunting were

liable to prosecutions, fines, and imprisonment, and could be removed by

military force. The agent had the authority to get soldiers to aid in the

execution of his duty from the nearest military post. Although rigid

enforcement of the intercourse laws was required, and the use of military

force was suggested, it seemed almost impossible to stop the liquor traffic.

The character of the illegal traders was portrayed in a communication from

Brooks to Judge E. Herring, commissioner of Indian affairs, in which Brooks

said: