Lafcadio Hearn.

“Saint Malo.”

SAINT MALO

a lacustrine

village in lousiana.

For nearly fifty years there has existed in the southeastern swamp lands of Louisiana a certain strange settlement of Malay fishermen — Tagalas from the Philippine Islands. The place of their lacustrine village is not precisely mentioned upon maps, and the world in general ignored until a few days ago the bare fact of their aniphibious existence. Even the United States mail service has never found its way thither, and even in the great city of New Orleans, less than a hundred miles distant, the people were far better informed about the Carboniferous Era than concerning the swampy affairs of this Manila village. Occasionally vague echoes of its mysterious life were borne to the civilized centre, but these were scarcely of a character to tempt investigation or encourage belief. Some voluble Italian luggermen once came to town with a short cargo of oysters, and a long story regarding a ghastly “Chinese” colony in the reedy swamps south of Lake Borgne. For many years the inhabitants of the Oriental settlement had lived in peace and harmony without the presence of a single woman, but finally had managed to import an oblique-eyed beauty from beyond the Yellow Sea. Thereupon arose the first dissensions, provoking much shedding of blood. And at last the elders of the people had restored calm and fraternal feeling by sentencing the woman to be hewn in pieces and flung to the alligators of the bayou.

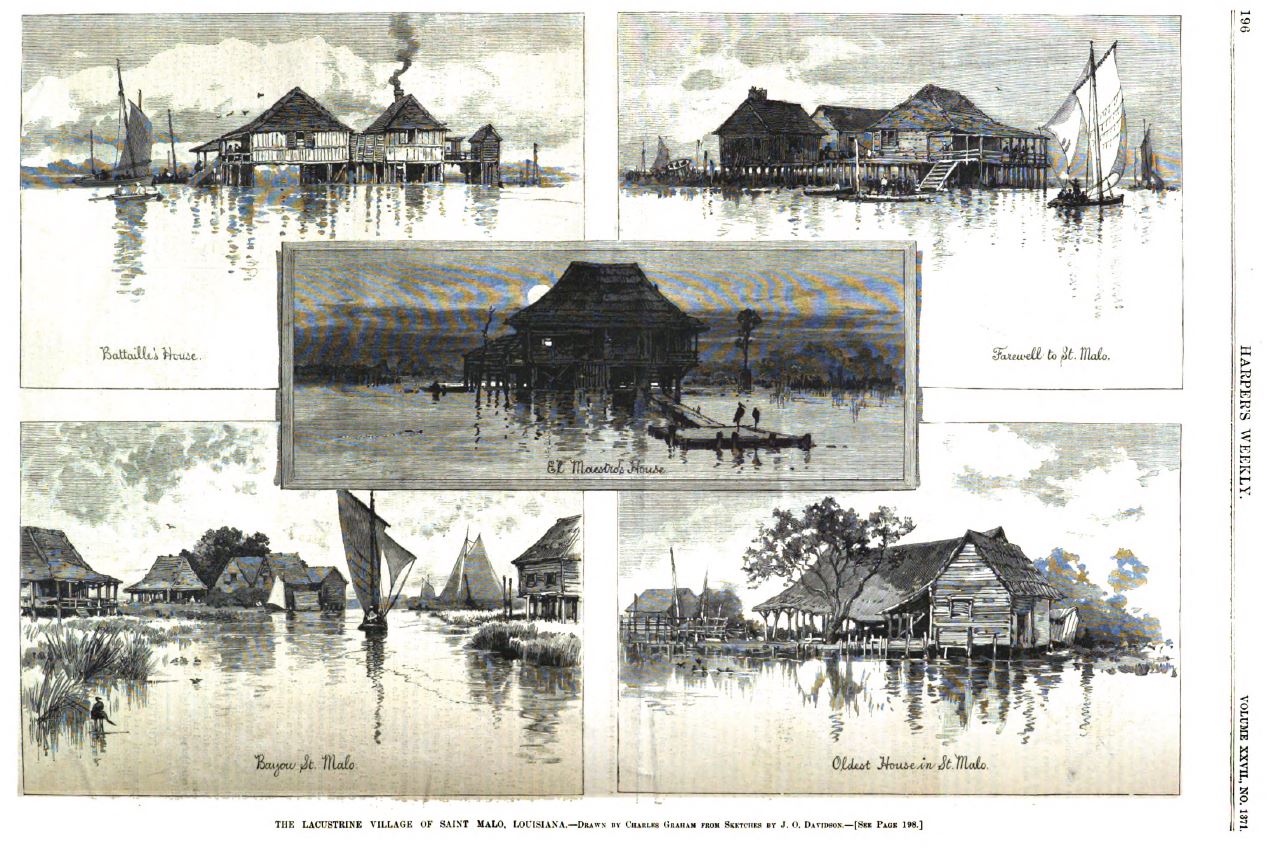

Possible the story is; probable it is not. Partly for the purpose of investigating it, but principally in order to offer Harper’s artist a totally novel subject of artistic study, the Times-Democrat of New Orleans chartered and fitted out an Italian bigger for a trip to the unexplored region in question — to the fishing station of Saint Malo. And a strange voyage it was. Even the Italian sailors knew not whither they were going, none of them had ever beheld the Manila village, or were aware of its location.

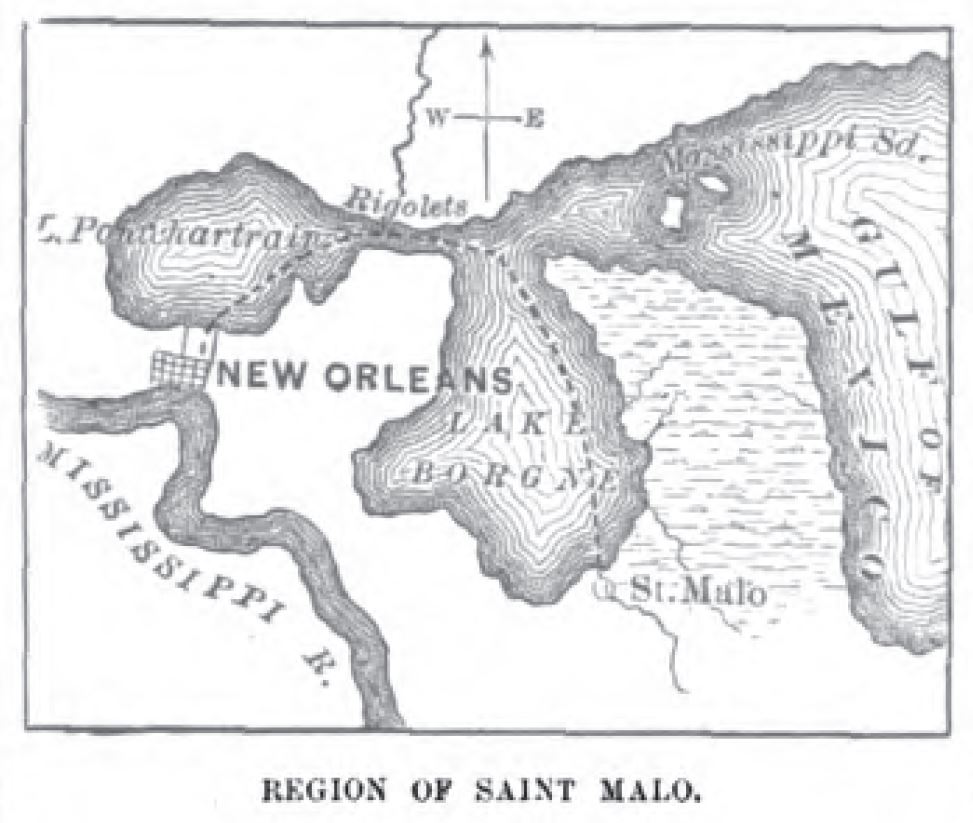

Starting from Spanish Fort northeastwardly across Lake Pontchartrain, after the first few miles sailed one already observes a change in the vegetation of the receding banks. The shore itself sinks, the lowland bristles with rushes and marsh grasses waving in the wind. A little further on and the water becomes deeply clouded with sap green — the myriad floating seeds of swamp vegetation. Banks dwindle away into thin lines; the greenish-yellow of the reeds changes into misty blue. Then it is all water and sky, motionless blue and heaving lazulite, until the reedy waste of Point-aux-Herbes thrusts its picturesque light-house far out into the lake. Above the wilderness of swamp grass and bulrushes this graceful building rises upon an open-work of wooden piles. Seven miles of absolute desolation separate the light-house keeper from his nearest neighbor. Nevertheless, there is a good piano there for the girls to play upon, comfortably furnished rooms, a good library. The pet cat has lost an eye in fighting with a moccasin, and it is prudent before descending from the balcony into the swamp about the house to reconnoitre for snakes. Still northeast. The sun is sinking above the rushy bank line; the west is crimsoning like iron losing its white heat. Against the ruddy light a cross is visible. There is a cemetery in the swamp. Those are the forgotten graves of light-house keepers. Our boat is spreading her pinions for flight through the Rigolets, that sinuous water-way leading to Lake Borgne. We pass by the defenseless walls of Fort Pike, a stronghold without a history, picturesque enough, but almost worthless against modern artillery. There is a solitary sergeant in charge, and a dog. Perhaps the taciturnity of the man is due to his long solitude, the vast silence of the land weighing down upon him. At last appears the twinkling light of the United States custom-house, and the enormous skeleton of the Rigolets bridge. The custom-house rises on stilts out of the sedge-grass. The pretty daughter of the inspector can manage a skiff as well as most expert oarsmen. Here let us listen awhile in the moonless night. From the south a deep sound is steadily rolling up like the surging of a thousand waves, like the long roaring of breakers. But the huge blind lake is scarcely agitated; the distant glare of a prairie fire illuminates no spurring of “white horse.” What, then, is that roar, as of thunder muffled by distance, as of the moaning that seamen hear far inland while dreaming at home of phantom seas? It is only a mighty chorus of frogs, innumerable millions of frogs, chanting in the darkness over unnumbered leagues of swamp and lagoon.

On the eastern side of the Rigolets Lake Borgne has scalloped out its grass-fringed bed in the form of a gigantic clover leaf — a shallow and treacherous sea, from which all fishing-vessels scurry in wild terror when a storm begins to darken. No lugger can live in those short chopping waves when Gulf winds are mad. To reach the Manila settlement one must steer due south until the waving bulrushes again appear, this time behind muddy shoals of immense breadth. The chart announces depths varying from six inches to three and a half feet. For a while we grope about blindly along to the banks. Suddenly the mouth of a bayou appears — “Saint Malo Pass.” With the aid of poles the vessel manages to shamble over a mud-har, and forth-with rocks in forty feet of green water. We reached Saint Mato upon a leaden-colored day, and the scenery in its gray ghastliness recalled to us the weird landscape painted with words by Edgar Poe — “Silence: a Fragment.”

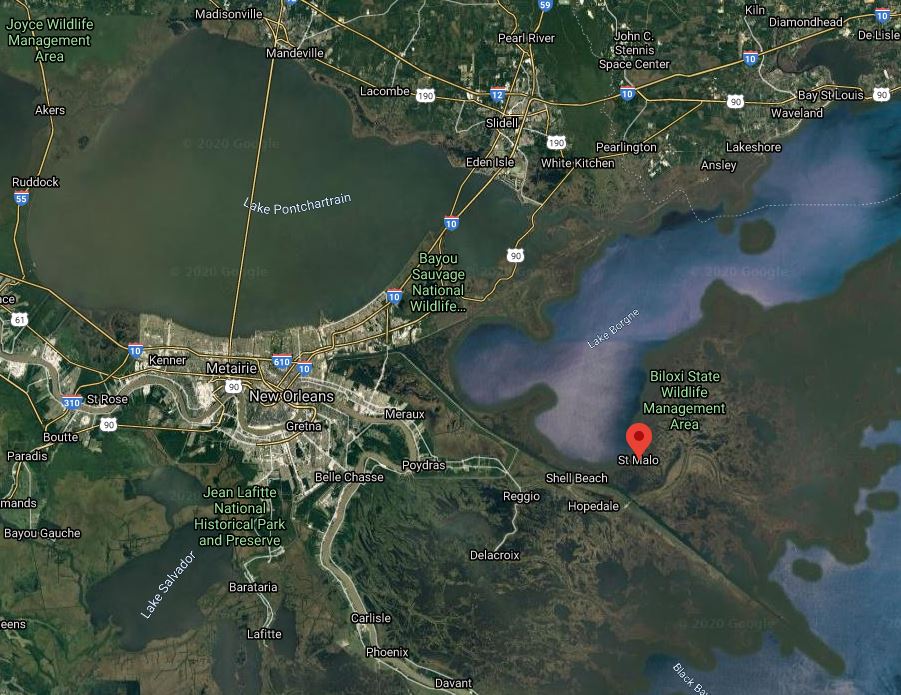

Out of the shuddering reeds and banneretted grass on either side rise the fantastic houses of the Malay fishermen, posed upon slender supports above the marsh, like cranes or bitterns watching for scaly prey. Hard by the slimy mouth of the bayou extends a strange wharf, as ruined and rotted and unearthly as the timbers of the spectral ship in the “Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” Odd craft huddle together beside it, fishing-nets make cobwebby drapery about the skeleton timber-work. Green are the banks, green the water is, green also with fungi every beam and plank and board and shingle of the houses upon stilts. All are built in true Manila style, with immense hat shaped eaves and balconies, but in wood; for it had been found that palmetto and woven cane could not withstand the violence of the climate. Nevertheless, an this wood had to be shipped to the bayou from a considerable distance, for large trees do not grow in the salty swamp. The highest point of land as far as the “Devil’s Elbow,” three or four miles away, and even beyond it, is only six inches above low-water mark, and the men who built those houses were compelled to stand upon ladders, or other wood frame-work, while driving down the piles, lest the quagmire should swallow them up.

Below the houses are patches of grass and pools of water and stretches of gray mud, pitted with the hoof-prints of hogs. Sometimes these hoof-prints are crossed with the tracks of the alligator, and a pig is missing. Chickens there are too — sorry-looking creatures; many have but one leg, others have but one foot; the crabs have bitten them off. All these domestic creatures of the place live upon fish.

Here is the home of the mosquito, and every window throughout all the marsh country must be closed with wire netting. At sundown the insects rise like a thick fog over the lowland; in the darkness their presence is signaled by a sound like the boiling of innumerable caldrons. Worse than these are the great green-headed tappanoes, dreaded by the fishermen. Sand-flies attack the colonists in warm weather; fleas are insolent at all hours; spiders of immense growth rival the net-weavers of Saint Malo, and hang their webs from the timbers side by side with seines and fishing-tackle. Wood-worms are busy undermining the supports of the dwellings, and wood-ticks attack the beams and joistings. A marvelous variety of creatures haunt the surrounding swamp — reptiles, insects, and birds. The prie-deau — “pray-god” — utters its soprano note; water-hens and plovers call across the marsh. Numberless snakes hide among the reeds, having little to fear save from the wild-cats, which attack them with savage recklessness. Rarely a bear or a deer finds its way near the bayou. There are many otters and musk-rats, minks and raccoons and rabbits. Buzzards float in the sky, and occasionally a bald-eagle sails before the sun.

Such is the land; its human inhabitants are not less strange, wild, picturesque. Most of them are cinnamon-colored men; a few are glossily yellow, like that bronze into which a small proportion of gold is worked by the molder. Their features are irregular without being actually repulsive; some have the cheek-bones very prominent and the eyes of several are set slightly aslant. The hair is generally intensely black and straight, but with some individuals it is curly and browner. In Manila there are several varieties of the Malay race, and these Louisiana settlers represent more than one type. None of them appeared tall; the greater number were under-sized, but all well knit, and supple as fresh-water eels. Their hands and feet were small; their movements quick and easy, but sailorly likewise, as of men accustomed to walk upon rocking decks in rough weather. They speak the Spanish language; and a Malay dialect is also used among them. There is only one white man in the settlement — the ship-carpenter, whom all the Malays address as “Maestro.” He has learned to speak their Oriental dialect, and has conferred upon several the sacrament of baptism according to the Catholic rite; for some of these men were not Christians at the time of their advent into Louisiana. There is but one black man in this lake village — a Portuguese Negro, perhaps a Brazilian maroon. The Maestro told us that communication is still kept up with Manila, and money often sent there to aid friends in emigrating. Such emigrants usually ship as seamen on board some Spanish vessel bound for American ports, and desert at the first opportunity. It is said that the colony was founded by deserters — perhaps also desperate refugees from Spanish justice.

Justice within the colony itself, however, is of a curiously primitive kind; for there are neither magistrates nor sheriffs, neither prisons nor police. Although the region is included within the parish of St. Bernard, no Louisiana official has ever visited it; never has the tax-gatherer attempted to wend thither his unwelcome way. In the busy season a hundred fierce men are gathered together in this waste and watery place, and these must be a law unto themselves. If a really grave quarrel arises, the trouble is submitted to the arbitration of the oldest Malay in the colony, Padre Carpio, and his decisions are usually accepted without a murmur. Should a man, on the other hand, needlessly seek to provoke a difficulty, he is liable to be imprisoned within a fish-car, and left there until cold and hunger have tamed his rage, or the rising tide forces him to terms. Naturally all these men are Catholics; but a priest rarely visits them, for it costs a considerable sum to bring the ghostly father into the heart of the swamp that he may celebrate mass under the smoky rafters of Hilario’s house — under the strings of dry fish.

There is no woman in the settlement, nor has the treble of a female voice been heard along the bayou for many a long year. Men who have families keep them at New Orleans, or at Proctorville, or at La Chinche; it would seem cruel to ask any woman to dwell in such a desolation, without comfort and without protection, during the long absence of the fishing-boats. Only two instances of a woman dwelling there are preserved, like beloved traditions, in the memory of the inhabitants. The first of these departed upon her husband's death; the second left the village after a desperate attempt had been made to murder her spouse. In the dead of night the man was unexpectedly assailed; his wife and little boy helped to defend him. The assailant was overcome, tied hand and foot with fish lines, and fastened to a stake deep driven into the swamp. Next morning they found him dead; the mosquitoes and tappanoes had filled the office of executioner. No excitement was manifested; the maestro dug a grave deep in the soft gray mud, and fixed above it a rude wooden cross, which still shows its silhouette against the sky just above the reeds.

But for the possession of modern fire-arms and one most ancient clock, the lake-dwellers of Saint Malo would seem to have as little in common with the civilization of the nineteenth century as had the inhabitants of the Swiss lacustrine settlements of the Bronze Epoch. Here time is measured rather by the number of alligator-skins sent to market, or the most striking incidents of successive fishing seasons, than by ordinary reckoning; and did not the Maestro keep a chalk record oft days of the week, none might know Sunday from Monday. There is absolutely no furniture in the place; not a chair, a table, or a bed can be found in all the dwellings of this aquatic village. Mattresses there are, filled with dry “Spanish beard”; but these are laid upon tiers of enormous shelves braced against the walls, where the weary fishermen slumber at night among barrels of flour and folded sails and smoked fish. Even the clothes (purchased at New Orleans or Proctorville) become as quaint and curiously tinted in that moist atmosphere as the houses of the village, and the broad hats take a greenish and grotesque aspect in odd harmony with the appearance of the ancient roofs. All the art treasures the colony consist of a circus poster immemorially old, which is preserved with much reverence, and two photographs jealously guarded in the Maestro's sea-chest. These represent a sturdy young woman with creole eyes, and a grim-looking Frenchman with wintry beard — the wife and father of the ship-carpenter. He pointed to them with a display of feeling made strongly pathetic by contrast with the wild character of the man, and his eyes, keen and hard as those of an eagle, softened a little as he kissed the old man's portrait, and murmured, “Mon chere vieux père.”

And nevertheless this life in the wilderness of reeds is connected mysteriously with New Orleans where the head-quarters of the Manila benevolent society are — La Union Philipina A fisherman dies; he is buried under the rustling reeds, and a pine cross planted above his grave; but when the flesh has rotted from the bones, these are taken up and carried by some lugger to the metropolis, where they are shelved away in those curious niche tombs which recall the Roman columbaria.

How, then, comes it that in spite of this connection with civilized life the Malay settlement of Lake Borgne has been so long unknown? Perhaps because of the natural reticence of the people. There is still in the oldest portion of the oldest quarter of New Orleans a certain Manila restaurant hidden away in a court, and supported almost wholly by the patronage of Spanish West Indian sailors. Few people belonging to the business circles of New Orleans know of its existence. The menu is printed in Spanish and English; the fare is cheap and good. Now it is kept by Chinese, for the Manila man and his oblique-eyed wife, comely as any figure upon a Japanese vase, have gone away. Doubtless his ears, like sea-shells, were haunted by the moaning of the sea, and the Gulf winds called to him by night, so that he could not remain.

The most intelligent person in Saint Malo is a Malay half-breed, Valentine. He is an attractive figure, a supple dwarfish lad almost as broad as tall, brown as old copper, with a singularly bright eye. He was educated in the great city, but actuallly abandoned a fine situation in the office of a judge to return to his swarthy father in the weird swamps. The old man is still there — Thomas de los Santos. He married a white woman, by whom he had two children, this boy and a daughter, Winnie, who is dead. Valentine is the best perogue oarsman in the settlement, and a boat bears his name. But opposite the house of Thomas de los Santos rides another graceful boat, rarely used, and whitely christened with the name of the dead Winnie. Latin names prevail in the nomenclature of boats and men; Marcellino, Francesco, Serafino, Florenzo, Victorio, Paosto, Hilario, Marcetto, are common baptismal names. The solitary creole appellation Aristide offers an anomaly. There are luggers and sloops bearing equally romantic names: Manrico de Aragon, Maravilla, Joven Imperatriz. Spanish piety has baptized several others with sacred words and names of martyrs.

Of the thirteen or fourteen large edifices on piles, the most picturesque is perhaps that of Carpio — old Carpio, who deserts the place once a year to play monte in Mexico. His home consistes of three wooden edifices so arranged that the outer two advance like wings, and the wharf is placed in the central structure. Smoked fish black with age hang from the roof, chickens squeak upon the floor, pigs grunt under the planking. Small, squat, swart dry, and grimy as his smoked fish is old Carpio, but his eye is bright and quick as a lizard’s.

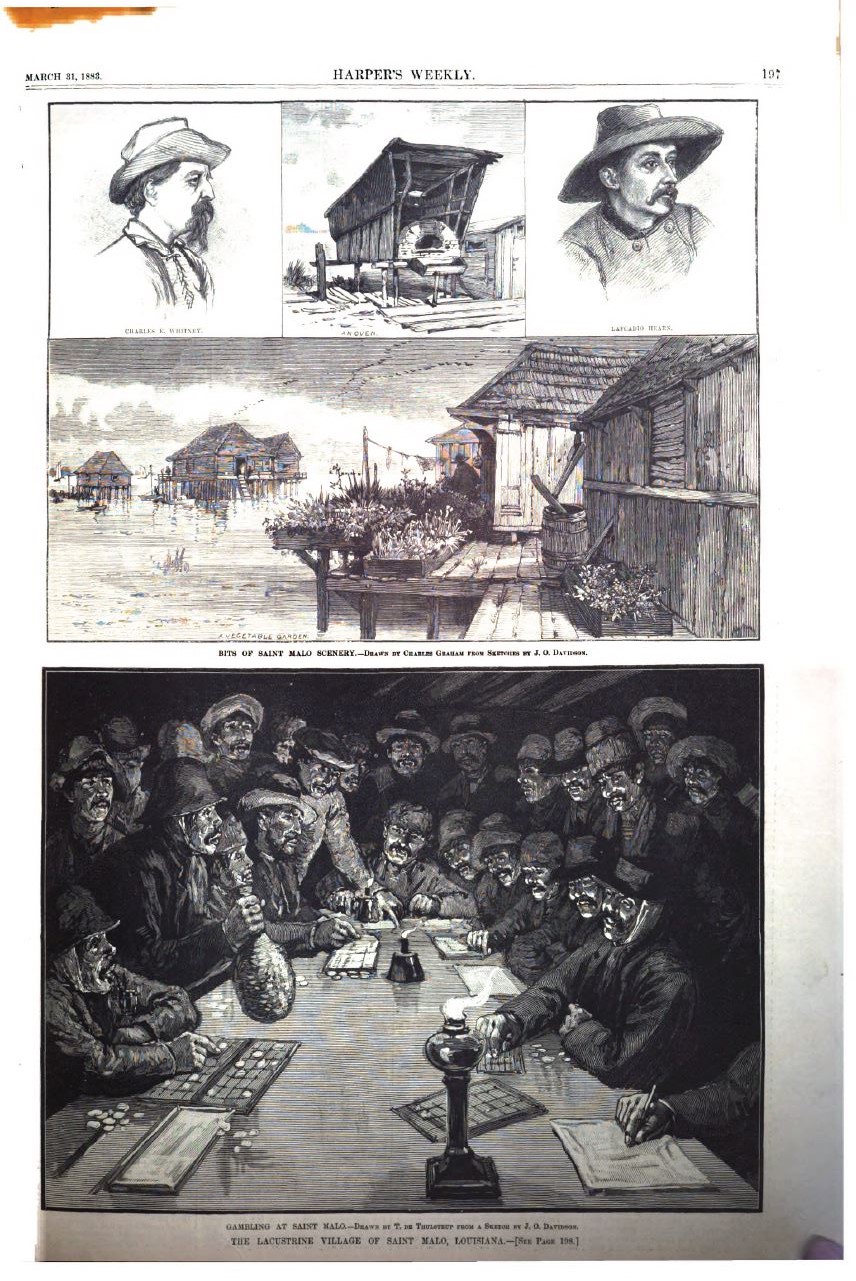

It is at Hilario’s great casa that the Manila men pass stormy evenings, playing monte or a species of Spanish keno. when the cantador, (the caller) sings out the numbers, he always accompanies the annunciation with some rude poetry characteristic of fisher life or Catholic faith:

Dos piquetes de rivero —

a pair of one (11); the two stakes to which the fish-car is fastened.

La casa del gato —

number 4; the cat’s house.

Arribe y abajo —

six with its nine (69); up and down.

Dos paticos en laguna —

pair of two (22); two ducklings in the lagoon or marsh — the Arabic numerals conveying by their shape this idea to the minds of fishermen. Picturesque? The numbers 77 suggest an almost similar idea — dos gansos en laguna (two geese in the lagoon):

Edad de Cristo —

thirty-three; the age of Christ.

Buena noche pasado —

twenty-five (Christmas-eve); the “Good-night” past.

El mas viejo —

ninety, “the oldest one.” Fifty-five is called the “two boats moored” together, as the figures placed thus 55 convey that idea to the mind — dos gálibos amarrados. Very musical is the voice of the cantador as he continues, shaking up the numbers in a calabash:

Veinte y nuéve — 29.

Seis con su cuatro:

Sesenta y cuatro — 64.

Ocho y seis:

Borrachenta y seis — 86 (drunken eighty -six),

Nina de quince (girl of fifteen);

Uno y cinco — 15.

Polite, too, these sinsiter-eyed men; there was not a single person in the room who did not greet us with a hearty buenas noches. The Artist made his sketch of that grotesque scene upon the rude plank-work which served as a gambling table by the yellow flickering of the lamps fed with fish-oil.

There is no liquor in the settlement, and these hardy fishers and alligator-hunters seem noe of the worse therefor. Their flesh is as hard as oarwood, and sickness rarely affect them, although they know little of comfort, and live largely upon raw fish, seasoned with vinegar and oil. There is but one chimmey — wooden structure — in the village, fires are hardly ever lighted, and in the winter the cold and damp would soon undermine feeble constitutions.

A sunset viewed from the balcony of the Maestro’s house seemed to us enchantment. The steel blue of the western horizon heated into furnace yellow, then cooled off into red splendors of astounding warmth and transparency. The bayou blushed crimson, the green of the marsh pools, of the shivering reeds of the decaying timberwork, took fairy bronze tints, and then, immense with march mist, the orange vermillion face of the sun peered luridly for the last time through marvelous choruses of frogs; the whole lowland throbbed and laughed with the wild music — a swamp-hymn deeper and mightier than even the surge sounds heard from the Rigolets bank; the world seemed to shake with it!

We sailed away just as the cast began to flame again, and saw the sun arise with reeds sharply outlined against the vivid vermilion of his face. Long fish-formed clouds sailed above him through the blue, green backed and iridescent bellied like denizens of the green water below. Valentine hailed us from the opposite bank holding up a struggling poule-d’eau can which he just rescued from a wild cat. A few pirogues were already flashing over the bayou, ribbing the water with wavelets half emerald, half orange gold. Brighter and brighter the eastern fires grew, oranges and vermilion's faded out into fierce yellow and against the blaze all the ragged ribs of Hilario’s elfish wharf stood out in black. Somebody fired a farewell shot as we reached the mouth of the bayou; there was a waving of picturesque hands and hats; and fair in our wake an alligator plashed his scaly body, making for the whispering line of reeds upon the opposite bank.

Lafcadio Hearn

.Notes

- Lacustrine. Having to do with a lake.

- Banneretted grass. Grass that looks like a small banner.

- Tappanoes. Horse flies. — Origin uncertain

- Spanish Beard. Early French explorers called Spanish moss Barbe Espagnol, or Spanish Beard.

- Columbaria. A columbarium is a building like a mausoleum, but it holds urns with ashes rather than bodies.

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Hearn, Lafcadio. “Saint Malo. A Lacustrine Village in Louisiana.” Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization 31 Mar. 1883: 196-99. Haithi Trust. Web. 20 July 2020. <https:// babel. hathitrust. org/ cgi/pt? id=pst.000020243272 &view=1up &seq=208>.