Louisiana Anthology

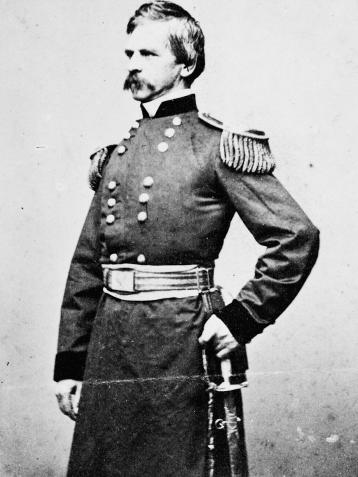

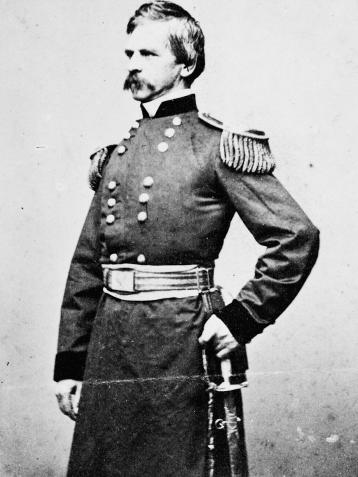

Wickham Hoffman.

Camp, Court, and Seige.

Colonel Wickham Hoffman

CAMP COURT AND SIEGE

A NARRATIVE OF PERSONAL ADVENTURE AND

OBSERVATION DURING TWO WARS

1861-1865 1870-1871

By WICKHAM HOFFMAN

ASSISTANT ADJ.-GEN. U. S. VOLS. AND

SECRETARY U. S. LEGATION AT PARIS

LONDON

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE, & RIVINGTON

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188 FLEET STREET.

1877

CONTENTS.

Hatteras. — “Black Drink.” — Fortress Monroe. — General Butler. — Small-pox. — “L’Isle des Chats.” — Lightning. — Farragut. — Troops land. — Surrender of Forts …

Page 11

New Orleans. — Custom-house. — Union Prisoners. — The Calaboose. — “Them Lincolnites.” — The St. Charles. — “Grape-vine Telegraph.” — New Orleans Shop-keepers. — Butler and Soulé. — The Fourth Wisconsin. — A New Orleans Mob. — Yellow Fever

… Page 23

Vicksburg. — River on Fire. — Baton Rouge. — Start again for Vicksburg. — The Hartford. — The Canal. — Farragut. — Captain Craven. — The Arkansas. — Major Boardman. — The Arkansas runs the Gauntlet — Malaria … Page 35

Sickness. — Battle of Baton Rouge. — Death of Williams. — “Fix Bayonets!” — Thomas Williams. — His Body. — General T. W. Sherman. — Butler relieved. — General Orders, No. 10. — Mr. Adams and Lord Palmerston. — Butler’s Style … Page 47

T. W. Sherman. — Contrabands. — Defenses of New Orleans. — Exchange of Prisoners. — Amenities in War. — Port Hudson. — Reconnoissance in Force. — The Fleet. — Our Left. — Assault of May 27th. — Sherman wounded. — Port Hudson surrenders … Page 59

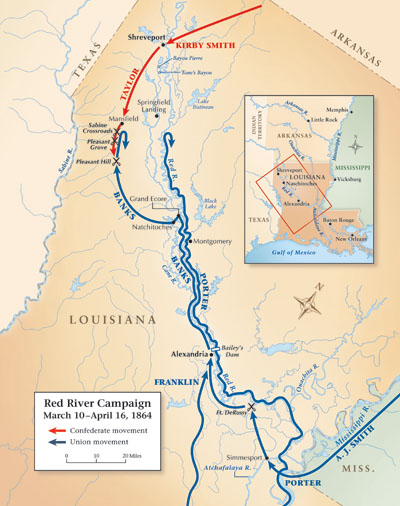

Major-general Franklin. — Sabine Pass. — Collision at Sea. — March through Louisiana. — Rebel Correspondence. — “The Gypsy’s Wassail.” — Rebel Women. — Rebel Poetry. — A Skirmish. — Salt Island. — Winter Climate. — Banks’s Capua. — Major Joseph Bailey

… Page 74

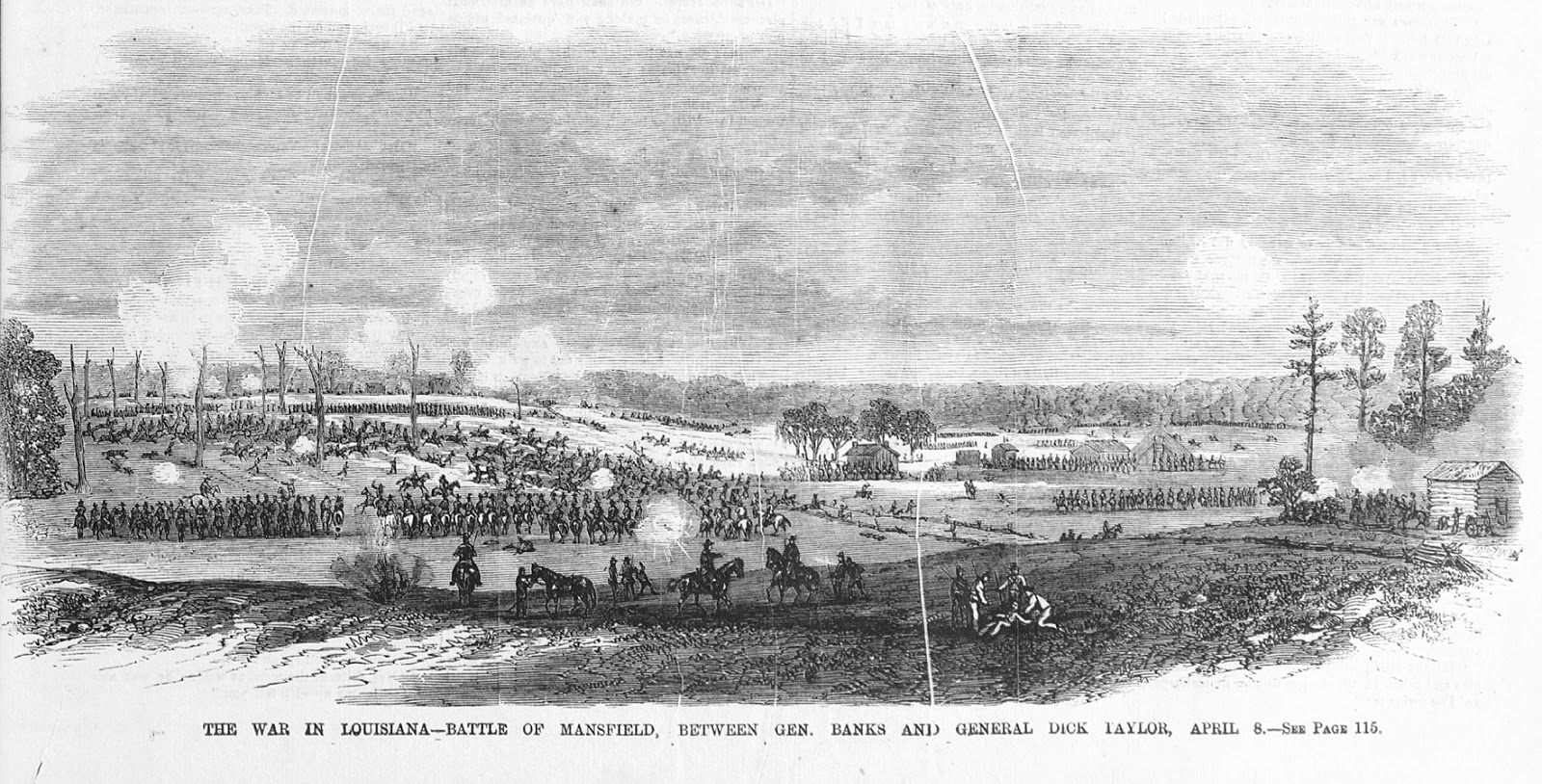

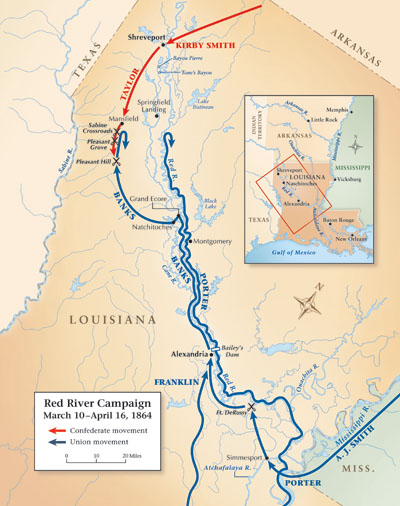

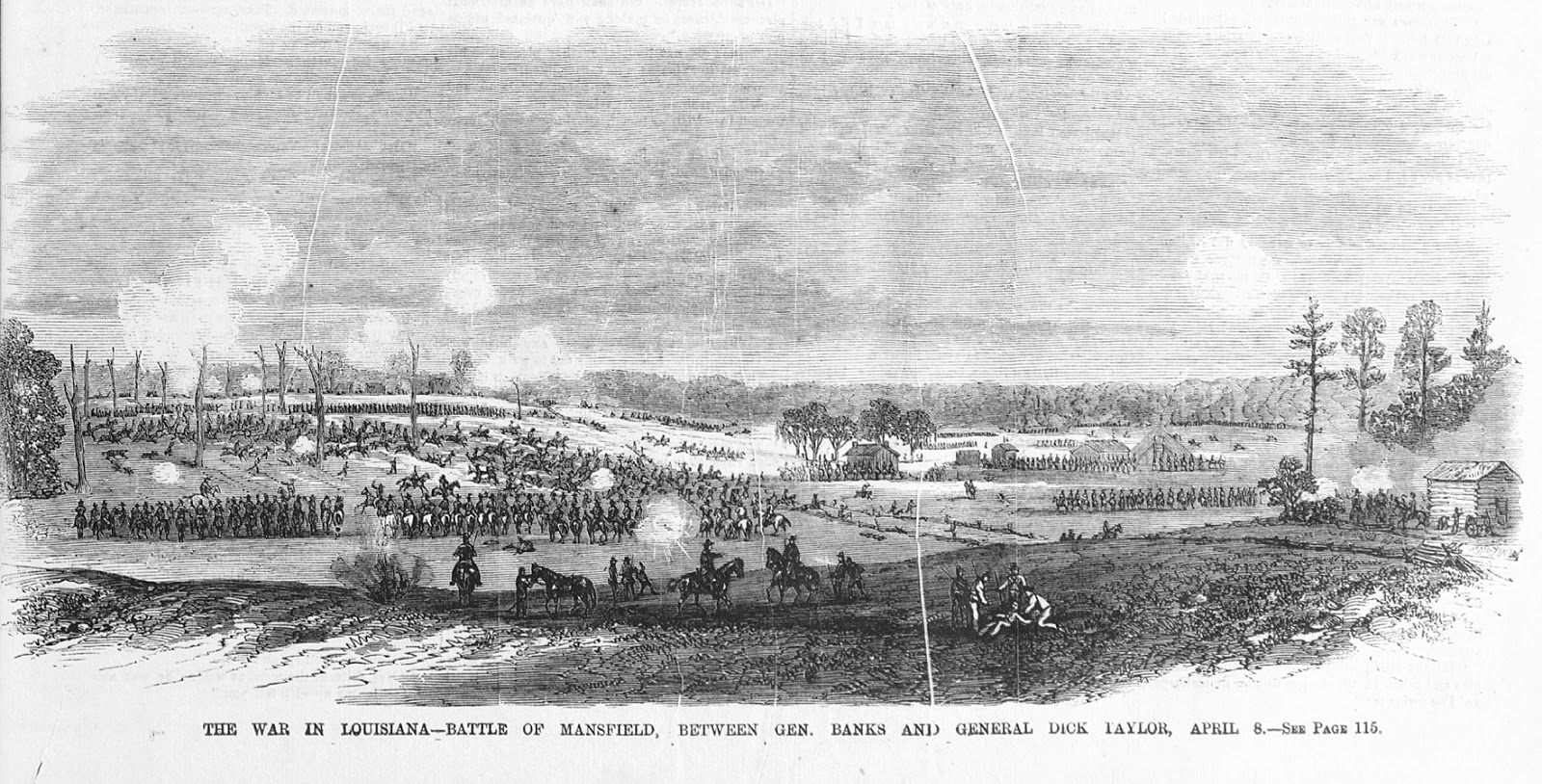

Mistakes. — Affair at Mansfield. — Peach Hill. — Freaks of the Imagination. — After Peach Hill. — General William Dwight. — Retreat to Pleasant Hill. — Pleasant Hill. — General Dick Taylor. — Taylor and the King of Denmark. — An Incident

… Page 87

Low Water. — The Fleet in Danger. — We fall back upon Alexandria. — Things look Gloomy. — Bailey builds a Dam in ten Days. — Saves the Fleet. — A Skirmish. — Smith defeats Polignac. — Unpopularity of Foreign Officers. — A Novel Bridge. — Leave of Absence.

— A Year in Virginia. — Am ordered again to New Orleans

… Page 98

Visit to Grant’s Head-quarters. — His Anecdotes of Army Life. — Banks relieved. — Canby in Command. — Bailey at Mobile. — Death of Bailey. — Canby as a Civil Governor. — Confiscated Property. — Proposes to rebuild Levees. — Is stopped by Sheridan. — Canby appeals.

— Is sustained, but too late. — Levees destroyed by Floods. — Conflict of Jurisdiction. — Action of President Johnson. — Sheridan abolishes Canby’s Provost Marshal’s Department. — Canby asks to be recalled. — Is ordered to Washington. — To Galveston. — To Richmond.

— To Charleston. — Is murdered by the Modocs. — His Character

… Page 105

CAMP, COURT, AND SIEGE.

Hatteras. — “Black Drink.” — Fortress Monroe. — General Butler. — Small-pox. — “L’Isle

des Chats.” — Lightning. — Farragut. — Troops

land. — Surrender of Forts.

IN

February, 1862, the writer of the following

pages, an officer on the staff of Brigadier-general

Thomas Williams, was stationed at Hatteras. Of all

forlorn stations to which the folly and wickedness

of the Rebellion condemned our officers, Hatteras

was the most forlorn. It blows a gale of wind half

the time. The tide runs through the inlet at the

rate of five miles an hour. It was impossible to unload

the stores for Burnside’s expedition during

more than three days of the week. After an easterly

blow — and there are enough of them — the waters

are so piled up in the shallow sounds between Hatteras

and the Main, that the tide ebbs without intermission

for twenty-four hours.

The history of Hatteras is curious. There can

be little doubt that English navigators penetrated

into those waters long before the Pilgrims landed at

Plymouth. But the colony was not a success. Of

the colonists some returned to England; others died

of want. The present inhabitants of the island are

a sickly, puny race, the descendants of English convicts.

When Great Britain broke up her penal settlement

at the Bermudas, she transported the most

hardened convicts to Van Diemens Land; those who

had been convicted of minor offenses, she turned

loose upon our coast. Here they intermarried; for

the inhabitants of the Main look down upon them as

an inferior race, and will have no social intercourse

with them. The effect of these intermarriages is

seen in the degeneracy of the race.

Until within a few years their principal occupation

was wrecking. Hatteras lies on the direct route of

vessels bound from the West Indies to Baltimore,

Philadelphia, and New York. The plan adopted by

these guileless natives to aid the storm in insuring

a wreck was simple, but effective. There is a half-wild

pony bred upon the island called “marsh pony.”

One of these animals was caught, a leg tied up Rarey

fashion, a lantern slung to his neck, and the

animal

driven along the beach on a stormy night. The

effect was that of a vessel riding at anchor. Other

vessels approached, and were soon unpleasantly aware

of the difference between a ship and a marsh pony.

The dwellings bear witness to the occupation of

their owners. The fences are constructed of ships’

knees and planks. In their parlors you may see on

one side a rough board door, on the other an exquisitely

finished rose-wood or mahogany cabin door,

with silver or porcelain knobs. Contrast reigns everywhere.

But the place is not without its attractions to the

botanist. A wild vine, of uncommon strength and

toughness, grows abundantly, and is used in the

place of rope. The iron-tree, hard enough to turn

the edge of the axe, and heavy as the metal from

which it takes its name, is found in abundance, and

the tea-tree, from whose leaves the inhabitants draw

their tea when the season has been a bad one for

wrecks. This tea-tree furnishes the “black drink,”

which the Florida Indians drank to make themselves

invulnerable. They drank it with due religious ceremonies

till it nauseated them, when it was supposed

to have produced the desired effect. What a pity

that we can not associate some such charming superstition

with the

maladie de mer!

It would so comfort

us in our affliction!

But we were not to stay long on this enchanted

isle. Butler had organized his expedition against

New Orleans, and it was now ready to sail. He had

applied for Thomas Williams, who had been strongly

recommended to him by Weitzel, Kenzel, and other

regular officers of his staff. Early in March we received

orders to report to Butler at Fortress Monroe.

We took one of those rolling tubs they call “propellers,”

which did the service between the fortress and

Hatteras for the Quartermaster’s Department; and,

after nearly rolling over two or three times, we reached

Old Point. Here we found the immense steamer

the Constitution, loaded with three regiments, ready

to sail. Williams had hoped to have two or three

days to run North and see his wife and children,

whom he had not seen for months. But with him

considerations of duty were before all others. He

thought that three regiments should be commanded

by a brigadier, and he determined to sail at once.

It was a disappointment to us all. To him the loss

was irreparable. He never saw his family again.

It has always appeared to me that General Butler

has not received the credit to which he is entitled

for the capture of New Orleans. Without him New

Orleans would not have been taken in 1862, and a

blow inflicted upon the Confederacy, which the London

Times characterized as the heaviest it had yet

received — “almost decisive.” The writer has no

sympathy with General Butler’s extreme views, and

no admiration for his protégés; but he was cognizant

of the New Orleans expedition from its inception,

he accompanied it on the day it set sail, he landed

with it in New Orleans, he remained in that city or

its neighborhood during the whole of Butler’s command;

and a sense of justice compels him to say that

Butler originated the expedition, that he carried it

through, under great and unexpected difficulties,

that he brought it to a successful termination, and

that his government of the city at that time, and under

the peculiar circumstances, was simply admirable.

General Benjamin F. Butler

It is not perhaps generally known that it was Butler

who urged this enterprise upon the President.

He was answered that no troops could be spared;

M’Clellan wanted them all for his advance upon

Richmond. Butler thereupon offered to raise the

troops himself, provided the Government would

give him three old regiments. The President consented.

The troops were raised in New England,

and three old regiments — the Fourth Wisconsin,

the Sixth Michigan, and the Twenty-first Indiana — designated

to accompany them. At the last moment

M’Clellan opposed the departure of the Western

troops, and even applied for the “New England

Division.” It was with some difficulty that, appealing

to the President, and reminding him of his

promise, Butler was able to carry out the design for

which the troops had been raised.

We sailed from Old Point on the 6th of March

with the three regiments I have named. We numbered

three thousand souls in all on board. If any

thing were wanting at this day to prove the efficacy

of vaccination, our experience on board that ship

is sufficient. We took from the hospital a man who

had been ill with the small-pox. He was supposed

to be cured. Two days out, his disease broke out

again. The men among whom he lay were packed

as close as herring in a barrel, yet but one took the

disease. They had all been vaccinated within sixty

days. I commend this fact to the attention of those

parish authorities in England who still obstinately

refuse to enforce the Vaccination Act.

Five days brought us, in perfect health, to Ship

Island. Here was another Hatteras, with a milder

climate, and no “black drink;” a low, sandy island

in the Gulf, off Mobile. This part of the Gulf of

Mexico was discovered and settled by the French.

They landed on Ship Island, and called it “L’Isle

des Chats,” from the large number of raccoons they

found there. Not being personally acquainted with

that typical American, they took him for a species of

cat, and named the island accordingly. From Ship

Island and the adjacent coast, which they settled, the

French entered Lake Borgne and Lake Pontchartrain,

and so up the Amite River in their boats.

They dragged their boats across the short distance

which separates the upper waters of the Amite from

the Mississippi, embarked upon the “Father of Waters,”

and sailed down the stream. Here they played

a trick upon John Bull; for, meeting an English

fleet coming up, the first vessels that ever entered

the mouths of the Mississippi, they boarded

them, claimed to be prior discoverers, and averred

that they had left their ships above. There existed

in those days an understanding among maritime

nations that one should not interfere with the prior

discoveries of another. The English thereupon turned,

and the spot, a short distance below New Orleans,

is to this day called “English Turn.”

We remained at the “Isle of Cats” about six

weeks — the life monotonous enough. The beach

offered a great variety of shell-fish, devil-fish, horse-shoes,

and sea-horses. An odd thing was the abundance

of fresh, pure water. Dig a hole two feet

deep anywhere in the sand on that low island, rising

scarcely five feet above the sea, and in two hours

it was filled with fresh water. After using it a

week, it became brackish; when all it was necessary

to do was to dig another hole.

When on Ship Island, I witnessed a curious freak

of lightning. One night we had a terrible thunderstorm,

such as one sees only in those southern latitudes.

In a large circular tent, used as a guard-tent,

eight prisoners were lying asleep, side by side. The

sentry stood leaning against the tent-pole, the butt

of the musket on the ground, the bayonet against

his shoulder. The lightning struck the tent-pole,

leaped to the bayonet, followed down the barrel,

tearing the stock to splinters, but only slightly stunning

the sentry. Thence it passed along the ground,

struck the first prisoner, killing him; passed through

the six inside men without injury to them; and off

by the eighth man, killing him.

Finally, the expedition was complete. Stores,

guns, horses, all had arrived. Butler became impatient

for the action of the navy. He went to the

South-west Pass, where Farragut’s fleet was lying,

and urged his advance. Farragut replied that he

had no coal. Butler answered that he would give

him what he wanted, and sent him fifteen hundred

tons. He had had the foresight to ballast his sailing

ships with coal, and so had an ample supply. A

week passed, and still the ships did not ascend the

river. Again Butler went to the Pass, and again

Farragut said that he had not coal enough — that

once past the forts, he might be detained on the

river, and that it would be madness to make the attempt

unless every ship were filled up with coal.

Once again Butler came to his aid, and gave him

three thousand tons. We were naturally surprised

that so vital an expedition should be neglected by

the Navy Department. The opinion was pretty

general among us that the expedition was not a favorite

with the Department, and that they did not

anticipate any great success from it. They were

quite as surprised as the rest of the world when

Farragut accomplished his great feat.

At length all was ready. The troops were embarked,

and lay off the mouth of the river, waiting

for the action of the fleet. Farragut, after an idle

bombardment of three days by the mortar-boats,

which he told us he had no confidence in, but which

he submitted to in deference to the opinions of the

Department and of Porter (the firing ceased, by-the-way,

when it had set fire to the wooden barracks in

Fort Jackson, and might have done some good if

continued), burst through the defenses, silenced the

forts, and ascended the river. It is not my province

to describe this remarkable exploit. Its effect

was magical. An exaggerated idea prevailed at that

time of the immense superiority of land batteries

over ships. One gun on shore, it was said, was equal

to a whole ship’s battery. The very small results obtained

by the united English and French fleets during

the Crimean war were quoted in proof. Those

magnificent squadrons effected scarcely any thing,

for the capture of Bomarsund was child’s play to

them. The English naval officers, proud of their

service and its glorious history, were delighted to

find that, when daringly led, ships could still do

something against land batteries, and all England

rang with Farragut’s exploit.

The part played by the army in this affair was minor,

but still important. Our engineer officers, who

had assisted in building forts St. Philip and Jackson,

knew the ground well. Under their guidance

we embarked, first in light-draught gun-boats, then

in barges, and made our way through the shallow

waters of the Gulf, and up the bayou, till we landed

at Quarantine, between Fort St. Philip and the city,

cutting off all communication between them. As, in

the stillness of an April evening, we made our slow

way up the bayou amidst a tropical vegetation, festoons

of moss hanging from the trees and drooping

into the water, with the chance of being fired on at

any moment from the dark swamp on either side,

the effect upon the imagination was striking, and the

scene one not easily forgotten.

The Capture of New Orleans, 1862.

Farragut had passed up the river, but the forts

still held out, and the great body of the troops was

below them. When, however, they found themselves

cut off from any chance of succor, the men in

Fort St. Philip mutinied, tied their officers to the

guns, and surrendered. Fort Jackson followed the

example. No doubt our turning movement had hastened

their surrender by some days. I once suggested

to Butler that we had hastened it by a week. “A

month, a month, sir,” he replied.

It was here they told us that the United States

flag had been hauled down from the Mint by a mob

headed by that scoundrel Mumford, and dragged

through the mud. I heard Butler swear by all that

was sacred, that if he caught Mumford, and did not

hang him, might he be hanged himself. He caught

him, and he kept his oath. There never was a wiser

act. It quieted New Orleans like a charm. The

mob, who had assembled at the gallows fully expecting

to hear a pardon read at the last moment, and

prepared to create a riot if he were pardoned, slunk

home like whipped curs.

New Orleans. — Custom-house. — Union Prisoners. — The Calaboose. — “Them

Lincolnites.” — The St. Charles. — “Grape-vine Telegraph.” — New

Orleans Shop-keepers. — Butler and Soulé. — The Fourth

Wisconsin. — A New Orleans Mob. — Yellow Fever.

ON

the evening of the 1st of May, 1862, the leading

transports anchored off the city. Butler sent for

Williams, and ordered him to land at once. Williams,

like the thorough soldier he was, proposed to

wait till morning, when he would have daylight for

the movement, and when the other transports, with

our most reliable troops, would be up. “No, sir,”

said Butler, “this is the 1st of May, and on this day

we must occupy New Orleans, and the first regiment

to land must be a Massachusetts regiment.” So the

orders were issued, and in half an hour the Thirty-first

Massachusetts Volunteers and the Sixth Massachusetts

Battery set foot in New Orleans.

As we commenced our march, Williams saw the

steamer Diana coming up with six companies of the

Fourth Wisconsin. He ordered a halt, and sent me

with instructions for them to land at once, and fall

into the rear of the column. I passed through the

mob without difficulty, gave the orders, and we resumed

our march. The general had directed that

our route should be along the levee, where our right

was protected by the gun-boats. Presently we found

that the head of the column was turning up Julia

Street. Williams sent to know why the change had

been made. The answer came back that Butler was

there, and had given orders to pass in front of the

St. Charles Hotel, while the band played “Yankee

Doodle,” and “Picayune Butler’s come to Town,” if

they knew it. They did not know it, unfortunately,

so we had one unbroken strain of the martial air of

“Yankee Doodle” all the way.

Arrived at the Custom-house late in the evening,

we found the doors closed and locked. Williams

said to me, “What would you do?” “Break the

doors open,” I replied. The general, who could not

easily get rid of his old, regular-army habits, ordered

“Sappers and miners to the front.” No doubt the

sappers and miners thus invoked would have speedily

appeared had we had any, but two volunteer regiments

and a battery of light artillery were the extent

of our force that night. I turned to the adjutant

of the Fourth Wisconsin, and asked if he had any

axes in his regiment. He at once ordered up two

or three men. We found the weakest-looking door,

and attacked it. As we were battering it in, the major

of the Thirty-first came up, and took an axe from

one of the men. Inserting the edge in the crack

near the lock, he pried it gently, and the door flew

open. I said, “Major, you seem to understand this

sort of thing.” He replied, “Oh! this isn’t the first

door I have broken open, by a long shot. I was once

foreman of a fire-company in Buffalo.”

We entered the building with great caution, for

the report had been spread that it was mined. The

men of the Fourth Wisconsin had candles in their

knapsacks; they always had every thing, those fellows!

We soon found the meter, turned the gas on,

and then proceeded to make ourselves comfortable

for the night. I established myself in the postmaster’s

private room — the Post-office was in the Custom-house — with

his table for my bed, and a package

of rebel documents for a pillow. I do not remember

what my dreams were that night. We took the

letters from the boxes to preserve them, and piled

them in a corner of my room. They were all subsequently

delivered to their respective addresses.

Pretty well tired out with the labor and excitement

of the day, I was just making myself tolerably

comfortable for the night, when the officer of the

day reported that a woman urgently desired to see

the general on a matter of life or death. She was

admitted. She told us that her husband was a

Union man, that he had been arrested that day and

committed to the “Calaboose,” and that his life was

in danger. The general said to her, “My good woman,

I will see to it in the morning.” “Oh, sir,” she

replied, “in the morning he will be dead! They

will poison him.” We did not believe much in the

poison story, but it was evident that she did. Williams

turned to me, and said, “Captain, have you a

mind to look into this?” Of course I was ready,

and ordering out a company of the Fourth Wisconsin,

and asking Major Boardman, a daring officer

of that regiment, to accompany me, I started for

the Calaboose, guided by the woman. The streets

were utterly deserted. Nothing was heard but the

measured tramp of the troops as we marched along.

Arrived at the Calaboose, I ordered the man I was

in search of to be brought out. I questioned him,

questioned the clerk and the jailer, became satisfied

that he was arrested for political reasons alone, ordered

his release, and took him with me to the Custom-house,

for he was afraid to return home. Being

on the spot, it occurred to me that it would be as

well to see if there were other political prisoners in

the prison. I had the books brought, and examined

the entries. At last I thought I had discovered another

victim. The entry read, “Committed as a suspicious

character, and for holding communication with

Picayune Butler’s troops.” I ordered the man before

me. The jailer took down a huge bunch of keys,

and I heard door after door creaking on its hinges.

At last the man was brought out. I think I never

saw a more villainous countenance. I asked him

what he was committed for? He evidently did not

recognize the Federal uniform, but took me for a

Confederate officer, and replied that he was arrested

for talking to “them Lincolnites.” I told the jailer

that I did not want that man — that he might lock

him up again.

Having commenced the search for political prisoners,

I thought it well to make thorough work of it;

so I inquired if there were other prisons in the city.

There was one in the French quarter, nearly two

miles off; so we pursued our weary and solitary

tramp through the city. My men evidently did not

relish it. The prison was quiet, locked up for the

night. We hammered away at the door till we got

the officers up; went in, examined the books, found

no entries of commitments except for crime; put

the officers on their written oaths that no one was

confined there except for crime; and so returned to

our Post-office beds.

The next day was a busy one. Early in the

morning I went to the St. Charles Hotel to make

arrangements for lodging the general and his staff.

With some difficulty I got in. In the rotunda of

that fine building sat about a dozen rebels, looking

as black as a thunder-cloud. I inquired for the

proprietor or clerk in charge, and a young man stepped

forward: “Impossible to accommodate us; hotel

closed; no servants in the house.” I said, “At all

events, I will see your rooms.” Going into one of

them, he closed the door and whispered, “It would

be as much as my life is worth, sir, to offer to accommodate

you here. I saw a man knifed on Canal

Street yesterday for asking a naval officer the time

of day. But if you choose to send troops and open

the hotel by force, why, we will do our best to make

you comfortable.” Returning to the rotunda, I

found Lieutenant Biddle, who had accompanied me — one

of the general’s aids — engaged in a hot discussion

with our rebel friends. I asked him “What

use in discussing these matters?” and, turning to the

rebs, with appropriate gesture said, “We’ve got you,

and we mean to hold you.” “That’s the talk,” they

replied; “we understand that.” They told us that

the rebel army was in sight of Washington, and that

John Magruder’s guns commanded the Capitol.

Why they picked out Magruder particularly, I can

not say. This news had come by telegraph. We

used to call the rebel telegraphic lines “the grapevine

telegraph,” for their telegrams were generally

circulated with the bottle after dinner.

The shop-keepers in New Orleans, when we first

landed there, were generally of the opinion of my

friend the hotel-clerk. A naval officer came to us

one morning at the Custom-house, and said that the

commodore wanted a map of the river; that he had

seen the very thing, but that the shop-keeper refused

to sell it, intimating, however, that if he were compelled

to sell it, why then, of course, he couldn’t help

himself. We ordered out a sergeant and ten men.

The officer got his map, and paid for it.

But Butler was not the man to be thwarted in

this way. Finding this

parti pris

on the part of

the shop-keepers, he issued an order that all shops

must be opened on a certain day, or that he should

put soldiers in, and sell the goods for account “of

whom it might concern.” On the day appointed

they were all opened. So, too, with the newspapers.

They refused to print his proclamation. An order

came to us to detail half a dozen printers, and send

them under a staff officer to the office of the True

Delta, and print the proclamation. We soon found

the men. From a telegraph-operator to a printer,

bakers, engine-drivers, carpenters, and coopers, we

had representatives of all the trades. This was in

the early days of the war. Afterward the men

were of an inferior class. The proclamation was

printed, and the men then amused themselves by

getting out the paper. Next morning it appeared

as usual; this was enough. The editor soon came

to terms, and the other journals followed suit.

On the 2d of May Butler landed and took quarters

at the St. Charles. There has been much idle

gossip about attempts to assassinate him, and his

fears of it. In regard to the latter, he landed in

New Orleans, and drove a mile to his hotel, with

one staff officer, and one armed orderly only on the

box. When his wife arrived in the city, he rode

with one orderly to the levee, and there, surrounded

by the crowd, awaited her landing. As regards the

former, we never heard of any well-authenticated

attempt to assassinate him, and I doubt if any was

ever made.

That afternoon Butler summoned the municipal

authorities before him to treat of the formal surrender

of the city. They came to the St. Charles,

accompanied by Pierre Soulé as their counsel. A

mob collected about the hotel, and became turbulent.

Butler was unprotected, and sent to the

Custom-house for a company of “Massachusetts”

troops. The only Massachusetts troops there were

the Thirty-first, a newly raised regiment. They

afterward became excellent soldiers, but at that time

they were very young and very green. It so happened,

too, that the only company available was

composed of the youngest men of the regiment.

They were ordered out. The officer in charge did

not know the way to the St. Charles. No guide

was at hand, so I volunteered to accompany them.

We drew the troops up on Common Street, and I

entered the hotel to report them to Butler. I found

him engaged in a most animated discussion with

Soulé. Both were able and eloquent men, but

Butler undoubtedly got the better of the argument.

Perhaps the fact that he had thirteen thousand bayonets

to back his opinions gave point to his remarks.

Interrupting his discourse for a moment only, he

said, “Draw the men up round the hotel, sir; and

if the mob make the slightest disturbance, fire on

them on the spot,” and went on with the discussion.

Returning to the street, I found the mob apostrophizing

my youthful soldiers with, “Does your

mother know you’re out?” and like popular wit. It

struck me that the inquiry was well addressed. I

felt disposed to ask the same question. I reported

the matter to Williams, and he thought that it would

be well to counteract the effect. That evening he

sent the band of the Fourth Wisconsin to play in

front of the St. Charles, with the whole regiment,

tall, stalwart fellows, as an escort. In a few minutes

the mob had slunk away. An officer heard one

gamin

say to another, “Those are Western men,

and they say they do fight like h—— .” One of the

officers told me that his men’s fingers itched to fire.

I suppose that all mobs are alike, but certainly the

New Orleans mob was as cowardly as it was brutal.

When we first occupied the Custom-house, they collected

about us, and annoyed our sentries seriously.

The orders were to take no notice of what was said,

but to permit no overt act. I was sitting one day in

my office, the general out, when Captain Bailey, the

officer who distinguished himself so much afterward

in building the Red River dam — and a gallant fellow

he was — rushed in, and said, “Are we to stand

this?” I said, “What’s the matter, Bailey?” He replied

that “One of those d——d scoundrels has taken

his quid from his mouth, and thrown it into the sentry’s

face.” I said, “No; I don’t think that we are

to stand that: that seems to me an ‘overt act.’ Arrest

him.” Bailey rushed out, called to the guard to

follow him, and, jumping into the crowd, seized the

fellow by the collar, and jerked him into the lines.

The guard came up and secured him. The mob fell

back and scattered, and never troubled us from that

day. The fellow went literally down upon his

knees, and begged to be let off. We kept him locked

up that night, and the next day discharged him.

He laid it all to bad whisky.

As the course of this narrative will soon carry the

writer from New Orleans into the interior, he takes

this opportunity to say that he has often been assured

by the rebel inhabitants, men and women of

position and character, that never had New Orleans

been so well governed, so clean, so orderly, and so

healthy, as it was under Butler. He soon got rid of

the “Plug-uglies” and other ruffian bands: some

he sent to Fort Jackson, and others into the Confederacy.

There was no yellow fever in New Orleans

while we held it, showing as plainly as possible that

its prevalence or its absence is simply a question of

quarantine. (Butler had sworn he would hang the

health officer if the fever got up.) Before we arrived

there, the “back door,” as it was called — the

lake entrance to the city — was always open, and for

five hundred dollars any vessel could come up. In

1861, when our blockade commenced, and during the

whole of our occupation, yellow fever was unknown.

In 1866 we turned the city over to the civil authorities.

That autumn there were a few straggling

cases, and the following summer the fever was virulent.

Vicksburg. — River on Fire. — Baton Rouge. — Start again for Vicksburg. — The

Hartford. — The Canal. — Farragut. — Captain Craven. — The

Arkansas. — Major Boardman. — The Arkansas runs the Gauntlet. — Malaria.

ADMIRAL FARRAGUT

was anxious, after the capture

of New Orleans, to proceed at once against Mobile.

I heard him say that, in the panic excited by the

capture of New Orleans, Mobile would fall an easy

prey. The Government, however, for political as

well as military reasons, was anxious to open the

Mississippi. Farragut was ordered against Vicksburg,

and Williams, with two regiments and a battery,

was sent to accompany and support him.

When one reflects upon the great strength of Vicksburg,

and the immense resources it afterward took

to capture it, it seems rather absurd to have sent us

against it with two regiments and a battery. The

excursion, however, if it is to be looked upon in this

light, was delightful. We had two fine river boats.

The plantations along the banks were in the highest

state of cultivation; the young cane, a few inches

above the ground, of the most lovely green. Indeed,

I know no more beautiful green than that of the

young sugar-cane. Our flag had not been seen in

those parts for over a year, and the joy of the negroes

when they had an opportunity to exhibit it

without fear of their overseers was quite touching.

The river was very high, and as we floated along

we were far above the level of the plantations, and

looked down upon the negroes at work, and into the

open windows of the houses. The effect of this to

one unused to it — the water above the land — was

very striking. Natchez, a town beautifully situated

on a high bluff, was gay with the inhabitants who

had turned out to see us. The ladies, with their

silk dresses and bright parasols, and the negro women,

with their gaudy colors, orange especially, which

they affect so much, and which, by-the-way, can be

seen at a greater distance than any other color I

know of.

One often hears of “setting a river on fire,” metaphorically

speaking: I have seen it done literally.

The Confederate authorities had issued orders to

burn the cotton along the banks to prevent its falling

into our hands. But as the patriotism of the

owners naturally enough needed stimulating, vigilance

committees were organized, generally of those

planters whose cotton was safe at a distance. These

men preceded us as we ascended the river; and

burned their neighbors’ cotton with relentless patriotism.

The burning material was thrown into the

stream, and floated on the surface a long time before

it was extinguished. At night it was a very beautiful

sight to see the apparently flaming water. We

had to exercise some care to steer clear of the burning

masses.

Arrived opposite Vicksburg, we boarded the flag-ship

to consult for combined operations. We found

Farragut holding a council of his captains, considering

the feasibility of passing the batteries of Vicksburg

as he had passed the forts. We apologized for

our intrusion, and were about to withdraw, when he

begged us to stay, and, turning to Williams, he said,

“General, my officers oppose my running by Vicksburg

as impracticable. Only one supports me. So

I must give it up for the present. In ten days they

will all be of my opinion; and then the difficulties

will be much greater than they are now.” It turned

out as he had said. In a few days they were nearly

all of his opinion, and he did it.

But we found no dry place for the soles of our

feet. “The water was down,” as the Scotchmen

say (down from the hills), and the whole Louisiana

side of the river was flooded. It would have been

madness to land on the Vicksburg side with two

regiments only. Nothing could be done, and we

returned to Baton Rouge, where, finding a healthy

and important position, a United States arsenal, and

Union men who claimed our protection, Williams

determined to remain and await orders.

Here cotton was offered us, delivered on the levee,

at three cents a pound. It was selling at one dollar

in New York. I spoke to Williams about it, and he

said that there was no law against any officer speculating

in cotton or other products of the country (one

was subsequently passed), but that he would not have

any thing to do with it, and advised me not to. I

followed his advice and example. A subsequent

post-commander did not. He made eighty thousand

dollars out of cotton, and then went home and was

made a brigadier-general; I never knew why.

But the Government was determined to open the

river at all hazards. Farragut was re-enforced.

Butler was ordered to send all the troops he could

spare. Davis was ordered down with the Upper

Mississippi fleet. Early in June we started again

for Vicksburg, with six regiments and two batteries.

It was a martial and beautiful sight to see the long

line of gun-boats and transports following each other

in Indian file at regular intervals. Navy and army

boats combined, we numbered about twenty sail — if

I may apply that word to steamers. On our way

up, the flag-ship, the famous Hartford, was nearly

lost. She grounded on a bank in the middle of the

river, and with a falling stream. Of course there

was the usual talk about a rebel pilot; but no vessel

with the draught of the Hartford, a sloop-of-war, had

ever before ventured to ascend above New Orleans.

The navy worked hard all the afternoon to release

her, but in vain. The hawsers parted like pack-thread.

I was on board when a grizzled quartermaster,

the very type of an old man-of-warsman,

came up to the commodore on the quarter-deck, and,

pulling his forelock, reported that there was a six-inch

hawser in the hold. Farragut ordered it up at

once. Two of our army transports, the most powerful,

were lashed together, the hawser passed round

them, and slackened. They then started with a jerk.

The Hartford set her machinery in motion, the gun-boat

lashed along-side started hers, and the old ship

came off, and was swept down with the current. It

required some seamanship to disentangle all these

vessels.

We found that the waters had subsided since our

last visit to Vicksburg, and so landed at Young’s

Point, opposite the town. Some years previously

there had been a dispute between the State authorities

of Louisiana and of Mississippi, and the Legislature

of the former had taken steps to turn the river,

and cut off Vicksburg by digging a canal across the

peninsula opposite. This we knew, and decided to

renew the attempt. We soon found traces of the

engineers’ work. The trees were cut down in a

straight line across the Point. Here we set to work.

Troops were sent to the different plantations both

up and down the river, and the negroes pressed into

the service. It was curious to observe the difference

of opinion among the old river captains as to the feasibility

of our plan. Some were sure that the river

would run through the cut; others swore that it

would not, and could not be made to. The matter

was soon settled by the river itself; for it suddenly

rose one night, filled up our ditch, undermined the

banks, and in a few hours destroyed our labor of

days. A somewhat careful observation of the Mississippi

since has satisfied me that if a canal be cut

where the stream impinges upon the bank, it will

take to it as naturally as a duck does to water. But

when the current strikes the opposite bank, as it

does at Young’s Point, you can not force it from

its course. Had we attempted our canal some miles

farther up, where the current strikes the right bank,

we should have succeeded. Grant, the next year,

renewed our ditch-digging experiment in the same

place, and with infinitely greater resources, but with

no better success.

Farragut had now made his preparations to run

by the batteries. He divided his squadron into three

divisions, accompanying the second division himself.

The third was under command of Captain Craven, of

the Brooklyn. We stationed Nim’s light battery — and

a good battery it was — on the point directly opposite

Vicksburg, to assist in silencing the fire of one

of the most powerful of the shore batteries. Very

early in the morning Farragut got under way;

two of his divisions passed, completely silencing the

rebel batteries. The third division did not attempt

the passage. This led to an angry correspondence

between the commodore and Craven, and resulted in

Craven’s being relieved, and ordered to report to

Washington. There was a great difference of opinion

among naval officers as to Craven’s conduct.

He was as brave an officer as lived. He contended

that it was then broad daylight, that the gunners on

shore had returned to their guns, and that his feeble

squadron would have been exposed to the whole fire

of the enemy, without any adequate object to be

gained in return. Farragut replied that his orders

were to pass, and that he should have done it at all

hazards.

And now an incident occurred which mortified

the commodore deeply. His powerful fleet, re-enforced

by Davis, lay above Vicksburg. The weather

was intensely hot, and the commodore, contrary to

his own judgment, as he told Williams, but on the

urgent request of his officers, had permitted the fires

to be extinguished. Early one morning we had sent

a steamboat with a party up the river to press negroes

into our canal work. Suddenly a powerful

iron-clad, flying the Confederate colors, appeared

coming out of the Yazoo River. There was nothing

for our unarmed little boat to do but to run for

it. The Arkansas opened from her bow-guns, and

the first shell, falling among the men drawn up on

deck, killed the captain of the company, and killed

or wounded ten men. It is so rarely that a shell

commits such havoc, that I mention it as an uncommon

occurrence.

The firing attracted the attention of the fleet, and

they beat to quarters. But there was no time to get

up steam. The Arkansas passed through them all

almost unscathed, receiving and returning their fire.

The shells broke against her iron sides without inflicting

injury. The only hurt she received was

from the Richmond. Alden kept his guns loaded

with powder only, prepared to use shell or shot as

circumstances might require. He loaded with solid

shot, and gave her a broadside as she passed. This

did her some damage, but nothing serious.

In the mean time the alarm was given to the transports.

Farragut had sent us an officer to say that

the Arkansas was coming, that he should stop her if

he could, but that he feared that he could not. The

troops were got under arms, and our two batteries

ordered to the levee. A staff officer said to General

Williams, “General, don’t let us be caught here like

rats in a trap; let us attempt something, even if we

fail.” “What would you do?” said the general.

“Take the Laurel Hill, put some picked men on

board of her, and let us ram the rebel. We may

not sink her, but we may disable or delay her, and

help the gun-boats to capture her.” “A good idea,”

said the general; “send for Major Boardman.”

Boardman, the daring officer to whom I have before

referred, had been brought up as a midshipman. He

was known in China as the “American devil,” from

a wild exploit there in scaling the walls of Canton

one dark night when the gates were closed; climbing

them with the help of his dagger only, making holes

in the masonry for his hands and feet. He was afterward

killed by guerrillas, having become colonel

of his regiment. Boardman came; the Laurel Hill

was cleared; twenty volunteers from the Fourth

Wisconsin were put on board, and steam got up.

The captain refused to go, and another transport

captain was put in command. We should have attempted

something, perhaps failed; but I think one

or other of us would have been sunk. But our preparations

were all in vain. The Arkansas had had

enough of it for that day. She rounded to, and took

refuge under the guns of Vicksburg.

Reporting this incident to Butler subsequently, he

said, “You would have sunk her, sir; you would

have sunk her.”

Farragut, as I have said, was deeply mortified.

He gave orders at once to get up steam, and prepared

to run the batteries again, determined to destroy

the rebel ram at all hazards. He had resolved

to ram her with the Hartford as she lay under the

guns of Vicksburg. It was with great difficulty he

was dissuaded from doing so, and only upon the

promise of Alden that he would do it for him in the

Richmond. Farragut, in his impulsive way, seized

Alden’s hand, “Will you do this for me, Alden?

will you do it?” The rapidity of the current, the

unusual darkness of the night, and the absence of

lights on the Arkansas and on shore, prevented the

execution of the plan. To finish with the Arkansas,

she afterward came down the river to assist in the

attack on Baton Rouge. Part of her machinery gave

out; she turned and attempted to return to Vicksburg,

was pursued by our gun-boats, run ashore,

abandoned, and burned.

The rebels never had any luck with their gun-boats.

They always came to grief. They were

badly built, badly manned, or badly commanded.

The Louisiana, the Arkansas, the Manassas, the

Tennessee, the Albemarle — great things were expected

of them all, and they did nothing.

But we were as far from the capture of Vicksburg

as ever. Fever attacked our men in those

fatal swamps, and they became thoroughly discouraged.

The sick-list was fearful. Of a battery of

eighty men, twenty only were fit for duty. The

Western troops, and they were our best, were homesick.

Lying upon the banks of the Mississippi,

with transports above Vicksburg convenient for

embarkation, they longed for home. The colonels

came to Williams, and suggested a retreat up the

river, to join Halleck’s command. Williams held a

council of war. He asked me to attend it. The

colonels gave their opinions, some in favor of, and

others against, the proposed retreat. When it came

to my turn, I spoke strongly against it. I urged

that we had no right to abandon our comrades at

New Orleans; that it might lead to the recapture

of that city; that if our transports were destroyed,

we should at least attempt to get back by land. I

do not suppose that Williams ever entertained the

least idea of retreating up the river, but thought it

due to his officers to hear what they had to say in

favor of it. The plan was abandoned.

Sickness. — Battle of Baton Rouge. — Death of Williams. — “Fix Bayonets!” — Thomas

Williams. — His Body. — General T. W. Sherman. — Butler

relieved. — General Orders, No. 10. — Mr. Adams and Lord

Palmerston. — Butler’s Style.

OF

the events which immediately followed the

council of war referred to in the last chapter, the

writer knows only by report. He was prostrated

with fever, taken to a house on shore, moved back

to head-quarters boat, put on board a gun-boat,

and sent to New Orleans. Farragut, with his usual

kindness, offered to take him on board the Hartford,

give him the fleet-captain’s cabin, and have the fleet-surgeon

attend him. But Williams declined the

offer. Farragut then offered to send him to New

Orleans in a gun-boat. This Williams accepted.

The writer was taken to New Orleans, sent to military

hospital, an assistant-surgeon’s room given up

to him, and every care lavished upon him; for one

of Williams’s staff — poor De Kay — wounded in a

skirmish, had died in hospital. Butler had conceived

the idea — erroneous, I am sure — that he had

been neglected by the surgeons. When I was

brought down he sent them word that if another of

Williams’s staff died there, they would hear from

him. I did not die.

Meantime, unable to effect any thing against

Vicksburg, with more than half his men on the sick-list,

Williams returned to Baton Rouge. The rebel

authorities, with spies everywhere, heard of the condition

of our forces, and determined to attack them.

Early one foggy morning twelve thousand men, under

Breckenridge, attacked our three or four thousand

men fit for duty. But they did not catch

Williams napping. He had heard of the intended

movement, and was prepared to meet it. Our forces

increased, too, like magic. Sick men in hospital,

who thought that they could not stir hand or foot,

found themselves wonderfully better the moment

there was a prospect of a fight. Happily a thick

mist prevailed. Happily, too, they first attacked

the Twenty-first Indiana, one of our stanchest regiments,

holding the centre of the position. This fine

regiment was armed with breech-loaders, the only

ones in the Gulf. Lying on the ground, they could

see the legs of the rebels below the mist, and fire

with a steady aim upon them, themselves unseen.

On the right the Thirtieth Massachusetts was engaged,

but not hotly. The left was but slightly

pressed. Williams had carefully reconnoitred the

ground the afternoon before, and marked out his

different positions. As the battle progressed, he fell

back upon his second position, contracting his lines.

As it grew hotter, he issued orders to fall back upon

the third position. As he gave the order, the lieutenant-colonel

of the Twenty-first, Colonel Keith, as

plucky a little fellow as lived, came to him and said,

“For God’s sake, general, don’t order us to fall back!

We’ll hold this position against the whole d—d rebel

army.” “Do your men feel that way, colonel?” replied

Williams; and turning to the regiment, he said,

“Fix bayonets!” As he uttered these words, he was

shot through the heart. The men fixed bayonets,

charged, and the rebels gave way. But there was

no one competent to take command. The Fourth

Wisconsin, on our left, waited in vain for the orders

Williams had promised them, eager to advance, for

he had meant that this regiment should take the

rebels in flank. The victory was won, but its fruits

were not gathered.

I think that grander words were never uttered by

a commander on the field of battle as he received

his death-wound than these words of Williams’s.

“Fix bayonets!” means business, and in this instance

they meant victory.

Thomas Williams was a noble fellow. Had he

lived, he would have been one of the great generals

of our war. Butler told the writer that, had Williams

survived Baton Rouge, it was his intention to

have turned over the whole military command to

him, and confined himself to civil matters. The

“General Order” he issued on Williams’s death is a

model of classic and pathetic English. It is quoted

as such by Richard Grant White in his “Miscellany.”

I give it entire, for it can not be too widely

circulated, both on account of its style and its subject.

“Head-quarters, Department of the Gulf,

“New Orleans, August 7th, 1862.

“General Orders, No. 56:

“The commanding general announces to the

Army of the Gulf the sad event of the death of

Brigadier-general Thomas Williams, commanding

Second Brigade, in camp at Baton Rouge.

“The victorious achievement, the repulse of the division

of Major-general Breckenridge by the troops

led on by General Williams, and the destruction of

the mail-clad Arkansas by Captain Porter, of the

navy, is made sorrowful by the fall of our brave,

gallant, and successful fellow-soldier.

“General Williams graduated at West Point in

1837; at once joined the Fourth Artillery in Florida,

where he served with distinction; was thrice

breveted for gallant and meritorious services in

Mexico as a member of General Scott’s staff. His

life was that of a soldier devoted to his country’s

service. His country mourns in sympathy with his

wife and children, now that country’s care and precious

charge.

“We, his companions in arms, who had learned to

love him, weep the true friend, the gallant gentleman,

the brave soldier, the accomplished officer, the

pure patriot and victorious hero, and the devoted

Christian. All, and more, went out when Williams

died. By a singular felicity, the manner of his death

illustrated each of these generous qualities.

“The chivalric American gentleman, he gave up

the vantage of the cover of the houses of the city,

forming his lines in the open field, lest the women

and children of his enemies should be hurt in the

fight.

“A good general, he made his dispositions and prepared

for battle at the break of day, when he met

his foe!

“A brave soldier, he received the death-shot leading

his men!

“A patriot hero, he was fighting the battle of

his country, and died as went up the cheer of victory!

“A Christian, he sleeps in the hope of a blessed

Redeemer!

“His virtues we can not exceed; his example we

may emulate, and, mourning his death, we pray,

’May our last end be like his.’

“The customary tribute of mourning will be worn

by the officers in the department.

“By command of Major-general Butler.

"R. T. Davis, Captain and A. A. A. G.”

Williams was an original thinker. He had some

rather striking ideas about the male portion of the

human race. He held that all men were by nature

cruel, barbarous, and coarse, and were only kept in

order by the influence of women — their wives, mothers,

and sisters. “Look at those men,” he would

say. “At home they are respectable, law-abiding

citizens. It’s the women who make them so. Here

they rob hen-roosts, and do things they would be

ashamed to do at home. There is but one thing

will take the place of their women’s influence, and

that is discipline; and I’ll give them enough of it.”

I used to think his views greatly exaggerated, but I

came to be very much of his opinion before the war

was over.

A curious thing happened to his body. It was

sent down in a transport with wounded soldiers.

She came in collision with the gun-boat Oneida coming

up, and was sunk. Various accounts were given

of the collision. It was of course reported that the

rebel pilot of the transport had intentionally run

into the gun-boat. I think this improbable, for I

have observed that rebel pilots value their lives as

much as other people. Captain (afterward Admiral)

Lee lay by the wreck, and picked up the wounded:

none were lost. Shortly afterward Gun-boat No. 1,

commanded by Crosby, a great friend of Williams,

came up. Lee transferred the men to her, ordered

her to New Orleans, and himself proceeded to Baton

Rouge. Crosby heard that Williams’s body

was on board. He spent several hours in searching

for it, but without success. He reluctantly concluded

to abandon the search. Some hours later

in the day, and several miles from the scene of the

disaster, a piece of the wreck was seen floating

down the current, with a box upon it. A boat was

lowered, and the box was picked up. It turned out

to be the coffin containing the body. His portmanteau

too floated ashore, fell into honest hands, and

was returned to me by a gentleman of the coast.

It had been General Butler’s intention, on my recovery,

to give me command of the Second Louisiana,

a regiment he was raising in New Orleans, mostly

from disbanded and rebel soldiers. My recovery

was so long delayed, however, that he was compelled

to fill the vacancy otherwise. Shortly afterward

General T. W. Sherman was ordered to New Orleans,

and I was assigned to duty on his staff. He

was sent to Carondelet to take charge of the post

at the Parapet, and of all the northern approaches

to New Orleans. This was done under orders from

Washington; but of this Sherman was not aware, for

no copy of the orders had been sent him. He never

knew to what an important command it was the intention

of the Government to assign him till some

years later, when the writer, having become Adjutant-general

of the Department of the Gulf, found

the orders in the archives of the Department.

But the days of Butler’s command were brought

to a close. Banks arrived with re-enforcements, and

exhibited his orders to take command of the Department.

No one was more surprised than Butler.

He had supposed that Banks’s expedition was directed

against Texas. His recall seemed ungrateful on

the part of the Government, for it was to him that

the capture of New Orleans at that early date was

principally due. It is probable that the consuls in

that city had complained of him, and our Government,

thinking it all-important to give no cause of

complaint to foreign governments, Great Britain and

France especially, recalled him.

General Nathaniel P. Banks

As General Butler will not again appear in these

pages, I can not close this part of my narrative without

endeavoring to do him justice in regard to one

or two points on which he has been attacked. The

silver-spoon story is simply absurd. Butler confiscated

and used certain table-silver. When Banks relieved

him, he turned it over to him. When a howl

was made about it toward the close of the war, and

the Government referred the papers to Butler, for a

report, he simply forwarded a copy of Banks’s quartermaster’s

receipt. I was amused once at hearing

that inimitable lecturer, Artemus Ward, get off a joke

upon this subject in New Orleans. He was describing

the Mormons, and a tea-party at Brigham Young’s,

and said that Brigham Young probably had a larger

tea-service than any one in the world, “except,” said

he, and then paused as if to reflect — “except, perhaps,

General Butler.” Imagine the effect upon a

New Orleans audience. It is perhaps needless to

observe that Butler was not at that time in command.

The only charge against Butler which was never

thoroughly disproved was that he permitted those

about him to speculate, to the neglect of their duties

and to the injury of our cause and good name. He

must have been aware of these speculations, and

have shut his eyes to them. But that he himself

profited pecuniarily by them, I do not believe.

The famous General Orders, No. 10, “The Woman’s

Order,” was issued while I was in New Orleans,

and excited much and unfavorable comment. Butler

ordered that ladies insulting United States officers

should be treated “as women of the town plying

their trade.” Strong, his adjutant-general, remonstrated,

and begged him to alter it. He said that

he meant simply that they should be arrested and

punished according to the municipal law of the city,

i.e., confined for one night and fined five dollars.

Strong replied, “Why not say so, then?” But Butler

has much of the vanity of authorship. He was

pleased with the turn of the phrase, thought it happy,

and refused to surrender it.

In this connection, when in London, I heard an

anecdote of Mr. Adams and Lord Palmerston which

is not generally known. It was not often that any

one got the better of old “Pam,” but Mr. Adams

did. When Butler’s order reached England, Lord

Palmerston was the head of the Government; Lord

John Russell was Secretary of State for Foreign

Affairs. Lord Palmerston wrote to Mr. Adams to

know if the order as printed in the London papers

was authentic. Mr. Adams asked if he inquired officially

or privately. Lord Palmerston replied rather

evasively. Mr. Adams insisted. Lord Palmerston

answered that if Mr. Adams must know, he

begged him to understand that he inquired officially.

Mr. Adams had the correspondence carefully copied

in Moran’s best handwriting, and inclosed it to

Lord John with a note inquiring, who was Her

Majesty’s Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs; was

it Lord Palmerston, or was it Lord John? A quick

reply came from Lord John, asking him to do nothing

further in the matter till he heard from him

again. The next day a note was received from

Lord Palmerston withdrawing the correspondence.

I have given two specimens of Butler’s style.

Here is another, and of a different character. At

the request of a naval officer in high command, Farragut

applied to Butler for steamboats to tow the

mortar vessels to Vicksburg. Butler replied that

he regretted that he had none to spare. The officer

answered that if Butler would prevent his

brother from sending quinine and other contraband

stores into the Confederacy, there would be boats

enough. This came to Butler’s ears. He answered.

After giving a list of his boats, and stating their different

employments, he proceeded substantially as

follows. I quote from memory. “Now, there are

two kinds of lying. The first is when a man deliberately

states what he knows to be false. The second

is when he states what is really false, but what

at the time he believes to be true. For instance,

when Captain —— reports that the ram Louisiana

came down upon his gun-boats, and a desperate

fight ensued, he stated what is in point of fact false;

for the Louisiana was blown up and abandoned,

and was drifting with the current, as is proved by

the report of the rebel commander, Duncan: but

Captain —— believed it to be true, and acted accordingly;

for he retreated to the mouth of the

river, leaving the transports to their fate.”

T. W. Sherman. — Contrabands. — Defenses of New Orleans. — Exchange

of Prisoners. — Amenities in War. — Port Hudson. — Reconnoissance

in Force. — The Fleet. — Our Left. — Assault of May 27th. — Sherman

wounded. — Port Hudson surrenders.

THE

autumn of 1862 passed without any special

incident. Sherman rebuilt the levees near Carrollton,

repaired and shortened the Parapet, pushed his

forces to the north, and occupied and fortified Manchac

Pass. All these works were constructed by

Captain Bailey, to whom I have already alluded,

and of whom I shall have much to say hereafter;

for he played a most important and conspicuous part

in the Louisiana campaigns. At Manchac he constructed

a

bijou

of a work built of mud and clamshells.

He had the most remarkable faculty of making

the negroes work. I have seen the old inhabitants

of the coast (French côte, bank of the river)

stopping to gaze with surprise at the “niggers"

trundling their wheelbarrows filled with earth on the

double-quick. Such a sight was never before seen

in Louisiana, and probably never will be again.

Sherman was the first officer, too, to enroll the

blacks, set them to work, and pay them wages. He

was no professed friend of the negro, but he did

more practically for their welfare to make them useful,

and save them from vagabondage, than Phelps

or any other violent abolitionist, who said that the

slaves had done enough work in their day, and so

left them in idleness, and fed them at their own

tables. Every negro who came within our lines — and

there were hundreds of them — was enrolled

on the quartermaster’s books, clothed, fed, and paid

wages, the price of his clothing being deducted.

The men worked well. They were proud of being

paid like white men.

Later in the season, Sherman sent out successful

expeditions into the enemy’s territory. One to Ponchitoula

destroyed a quantity of rebel government

stores; another, across Lake Pontchartrain, captured

a valuable steamer. Sherman employed an admirable

spy, the best in the Department. As a rule, both

Butler’s and Banks’s spies were a poor lot, constantly

getting up cock-and-bull stories to magnify their

own importance, and thus misled their employers.

Sherman’s spy was a woman. Her information

always

turned out to be reliable, and, what is perhaps

a little remarkable, was never exaggerated.

Butler had now left the Department, and Banks

was in command. About this time Holly Springs

was occupied by Van Dorn, and our dépôts burned,

Grant falling back. The attack upon Vicksburg, too,

from the Yazoo River had failed. Banks’s spies exaggerated

these checks greatly, and reported that the

enemy was in full march upon New Orleans. There

was something of a stampede among us. A new

command was created, called the “Defenses of New

Orleans,” and given to Sherman. In a fortnight the

face of these defenses was vastly changed. When

he took command, the city was undefended to the

east and south. In a few days the rebel works were

rebuilt, guns mounted, light batteries stationed near

the works, each supported by a regiment of infantry.

New Orleans, with our gun-boats holding the river

and lake, was impregnable.

No commanding officer in our army was more

thorough in his work than Sherman. I remember

an instance of this in an exchange of prisoners which

took place under his orders. The arrangements

were admirable. We were notified that a schooner

with United States soldiers on board lay at Lakeport,

on Lake Pontchartrain. Within an hour of receiving

the report I was on my way to effect the exchange.

I was accompanied by our quartermaster, to insure

prompt transportation to New Orleans; by our commissary,

to see that the men were fed, for our prisoners

were always brought in with very insufficient

supplies, the rebel officers assuring us that they had

not food to give them; and by our surgeon, to give

immediate medical assistance to those requiring it.

Sherman told me to give the rebel officers in charge

a breakfast or dinner, and offered to pay his share.

We reached Lakeport about sunset. I went on

board at once, and made arrangements for the exchange

at six o’clock in the morning. I inquired of

the men if they had had any thing to eat. “Nothing

since morning.” The officer in charge explained

that they had been delayed by head-winds; but they

were always delayed by head-winds. We sent food

on board that night. At six in the morning the

schooner was warped along-side of the pier. A train

was run down, a line of sentries posted across the

pier, and no stranger permitted to approach. The

roll was called, and as each man answered to his

name, he stepped ashore and entered the train.

Meantime I had ordered down a breakfast from the

famous French restaurant at Lakeport; and while

the necessary arrangements were being completed by

the quartermaster, we gave the Confederate officers

a breakfast. It was easy to see, from the manner

in which they attacked it, that they did not fare so

sumptuously every day. Colonel Szymanski, who

commanded, an intelligent and gentlemanly officer,

asked permission to buy the remnants from the restaurant

for lunch and dinner on the return voyage.

The train was now ready, the schooner set sail, and

we started for New Orleans. On our arrival, we

bought out a baker’s shop and one or two orange-women.

It was a long time since the prisoners had

tasted white bread. They formed, and marched to

the barracks. Before noon that day they were in

comfortable quarters, and seated at a bountiful dinner,

prepared in advance for them. This was Sherman’s

organization. I had an opportunity to contrast

it, not long after, with an exchange effected under

direct orders from head-quarters. The contrast

was not in Banks’s favor.

On this occasion I had gone down as a spectator,

and to see if I could be of use. I was going on

board the cartel, when I was stopped by a lady who

asked me to take a young girl on board to see her

brother. Of course I was compelled to refuse. She

then asked if I would not tell her brother that she

was on the end of the pier, that they might at least

see each other. This I promised to do. On board

I found a number of sailors, part of the crew of the

Mississippi, which had been recently lost at Port

Hudson. As usual, they had had nothing to eat

since the previous evening.

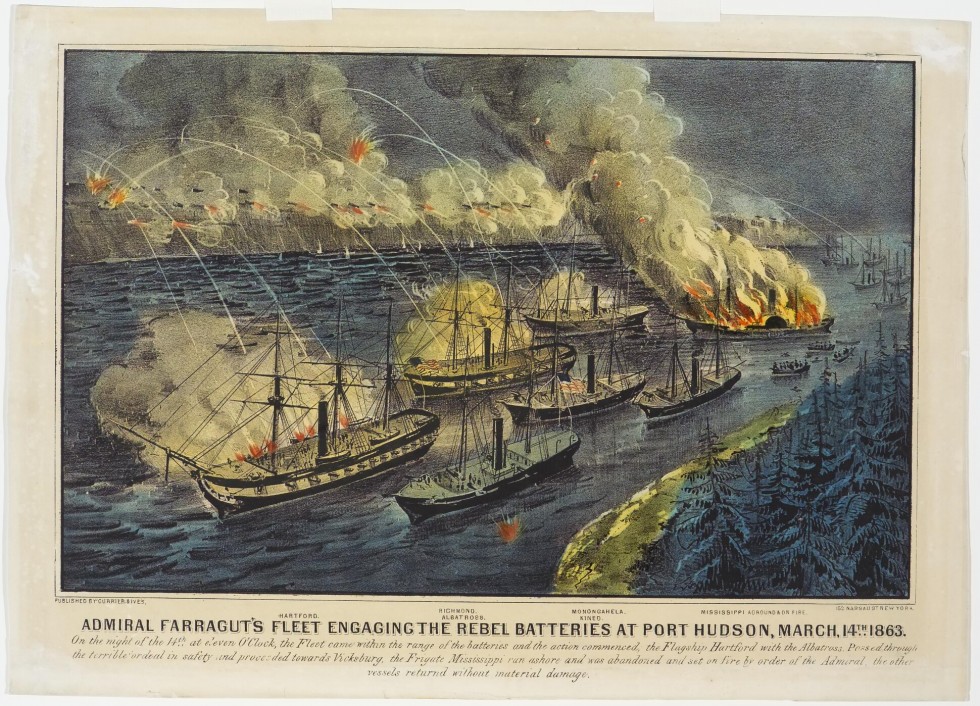

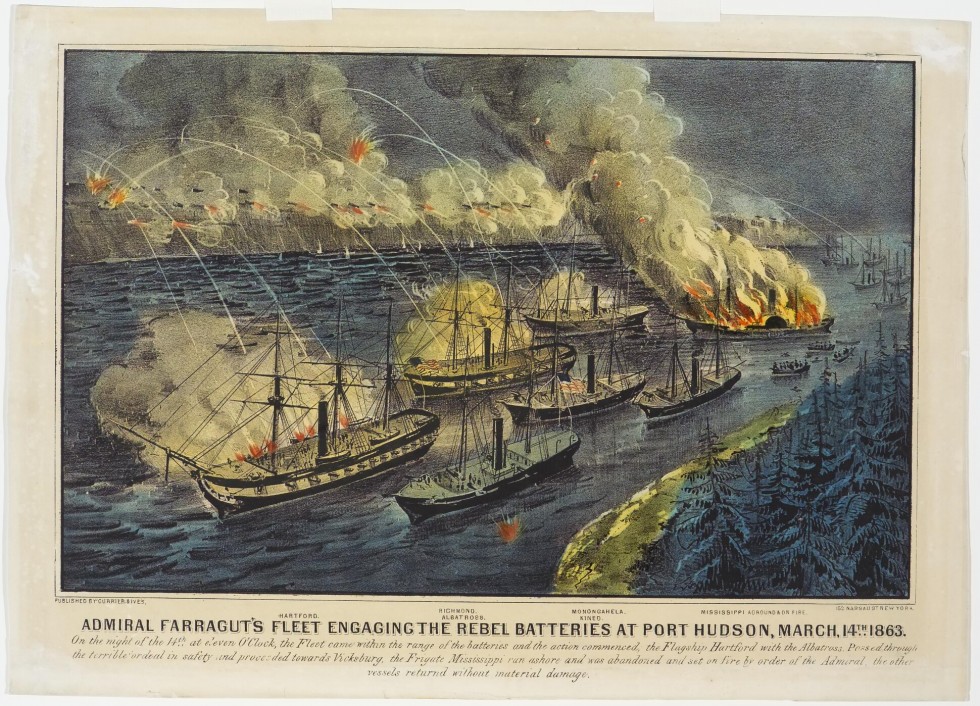

Battle of Port Hudson, March 14th, 1863

Before leaving the vessel, I inquired for Lieutenant

Adams. They told me that he was in “that

boat,” pointing to one, having pulled ashore, hoping

to see his sister. As I approached the shore I met

his boat returning; I stopped it, and asked him if he

had seen his sister. He had not. I told him to get

in with me, and I would take him to her. He did

so, and I pulled to within a few yards of the spot

where she was standing. Scarcely a word passed

between them, for both were sobbing. We remained

there about three minutes, and then pulled back.

We were all touched, officers and men, by this little

display of the home affections in the midst of war.

I think it did us all good.

General Banks was not pleased when he heard of

this incident. Perhaps it was reported to him incorrectly.

But Sherman thought that I had done

right. I always found that our regular officers

were more anxious to soften the rigors of war, and

to avoid all unnecessary severity, than our volunteers.

On our march through Louisiana under Franklin, a

strong provost guard preceded the column, whose

duty it was to protect persons and property from

stragglers till the army had passed. If planters in

the neighborhood applied for a guard, it was always

furnished. On one occasion such a guard was captured

by guerrillas. General Franklin wrote at once

to General Taylor, protesting against the capture of

these men as contrary to all the laws of civilized

warfare. Taylor promptly released them, and sent

them back to our lines. General Lee did the same

in Virginia.

And so the winter wore through, and the spring

came. Banks made a successful expedition to Alexandria,

winning the battle of Irish Bend. I am the

more particular to record this, as his reputation as a

commander rests rather upon his success in retreat

than in advance. And the month of May found us

before Port Hudson.

Vicksburg is situated eight hundred miles above

New Orleans. In all this distance there are but five

commanding positions, and all these on the left or

east bank of the river. It was very important to

the rebels to fortify a point below the mouth of the

Red River, in order that their boats might bring

forward the immense supplies furnished by Louisiana,

Texas, and Arkansas. They selected Port Hudson,

a miserable little village not far below the Red

River, and fortified it strongly. Sherman had seen

the importance of attacking this place when the

works were commenced, but Butler told him, very

truly, that he had not troops enough in the Department

to justify the attempt.

I think that it was the 24th of May when we

closed in upon Port Hudson. Sherman’s command

held the left. He had a front of three miles, entirely

too much for one division. The country

was a terra incognita to us, and we had to feel our

way. Of course there was much reconnoitring to

be done — exciting and interesting work — but not

particularly safe or comfortable. Sherman did

much of this himself. He had a pleasant way of

riding up in full sight of the enemy’s batteries, accompanied

by his staff. Here he held us while he

criticised the manner in which the enemy got his

guns ready to open on us. Presently a shell would

whiz over our heads, followed by another somewhat

nearer. Sherman would then quietly remark, “They

are getting the range now: you had better scatter.”

As a rule we did not wait for a second order.

I remember his sending out a party one day to

reconnoitre to our extreme left, and connect with

the fleet, which lay below Port Hudson. We knew

it was somewhere there; but how far off it lay, or

what was the character of the country between us,

we did not know. A company of cavalry reconnoitring

in the morning had been driven in. Sherman

determined to make a reconnoissance in force. He

sent out the cavalry again, and supported it with a

regiment of infantry. I asked permission to accompany

them. He gave it, and added, “By-the-way,

captain, when you are over there, just ride up and

draw their fire, and see where their guns are. They

won’t hit you.” I rode up and drew their fire, and

they did not hit me; but I don’t recommend the

experiment to any of my friends.

This reconnoissance was successful. We passed

through a thickly wooded country, intersected by

small streams, for about two miles, when we emerged

upon the open in full view of the works of Port

Hudson. This we had to cross, exposed to their

fire. We thus gained the road, running along the

top of the bluff; and, following this, we came in

view of the fleet. Our arrival produced a sensation.

They had been looking out for us for two or three

days. The men swarmed up the rigging and on to

the yards. Fifty telescopes were leveled at us; and

as we galloped down the bluff and along the levee to

the ships, cheer after cheer went up from the fleet.

We went on board the nearest gun-boat, and got

some bread-and-cheese and Bass — which tasted remarkably

good, by-the-way. I staid but a little

while, for I was anxious about my men. On our

homeward march the enemy opened on us, and we

lost two or three men. I felt saddened at the loss

of any men while in some measure under my command,

and reported this loss first to the general. I

was much comforted when he replied, “Lose men!

of course you lost men. Reconnoissances in force

always lose men!”