Gary D. Joiner.

“The Red River Campaign:

March 10 - May 22, 1864.”

© Gary D Joiner.

Used by permission.

All rights reserved.

At the time of the Red River Campaign in April 1864, the outcome of the Civil War appeared to be decided. The agricultural South had fought long and hard against the industrial North, but the zeal and military prowess of the Confederates was not enough to prevail against the vast resources of the North. The Red River Campaign, which included the largest combined army-navy operation of the war, was the last decisive Confederate victory of the war.

The target of the campaign was Shreveport, the capital of Confederate Louisiana and the headquarters for the Army of the Trans-Mississippi. The town was the nexus of a small military-industrial complex that included armories, foundries, and a naval shipyard. Outlying facilities were located in eastern Texas and southern Arkansas. It was also the gateway for a potential invasion of Texas, a tactic that President Abraham Lincoln was desperately seeking to employ.

The conduct of the campaign was flawed, however, with each side making serious tactical errors. The behavior of Union leaders raised such concerns in Washington that a congressional investigation was called. And one of the North’s leading generals was so incensed with the errors of his fellow officers that he called it, “one damn blunder from beginning to end.”

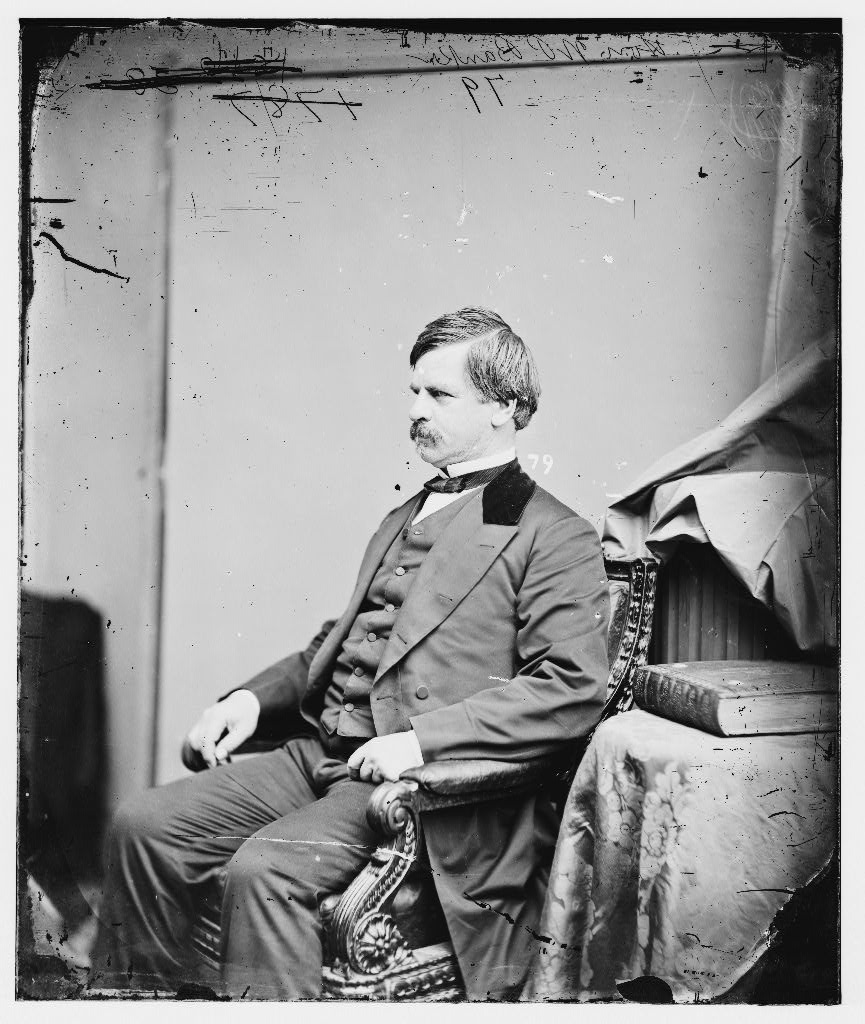

Union Major General Nathaniel P. Banks was the commander of the Department of the Gulf based in New Orleans. Banks was a contender for the Republican nomination for the presidency in 1864. He was a native of Massachusetts and had served as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. He was an ally and confidant of several wealthy New England textile mill owners. A political general with no formal military training, Banks needed a battlefield victory to cement support for his run for the presidency. He outranked every Union general west of the Appalachians. General Ulysses S. Grant had faced problems with Banks’ lack of cooperation during the Vicksburg Campaign the previous year. Both Henry Halleck, the army’s Chief-of-Staff, and the president wanted a campaign up the Red River and Banks decided to use it as his best opportunity for military success. Major General William T Sherman wanted to lead the campaign, but Grant could not spare him from the upcoming Atlanta Campaign. The naval commander, Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter, had committed to the campaign under the assumption that Sherman would lead it. Sherman loaned Porter 10,000 of his best veterans to protect the fleet from the Confederates. Sherman frankly told Porter that the men were there in case Banks abandoned the fleet, which Banks had implied he would do if his force got into trouble.

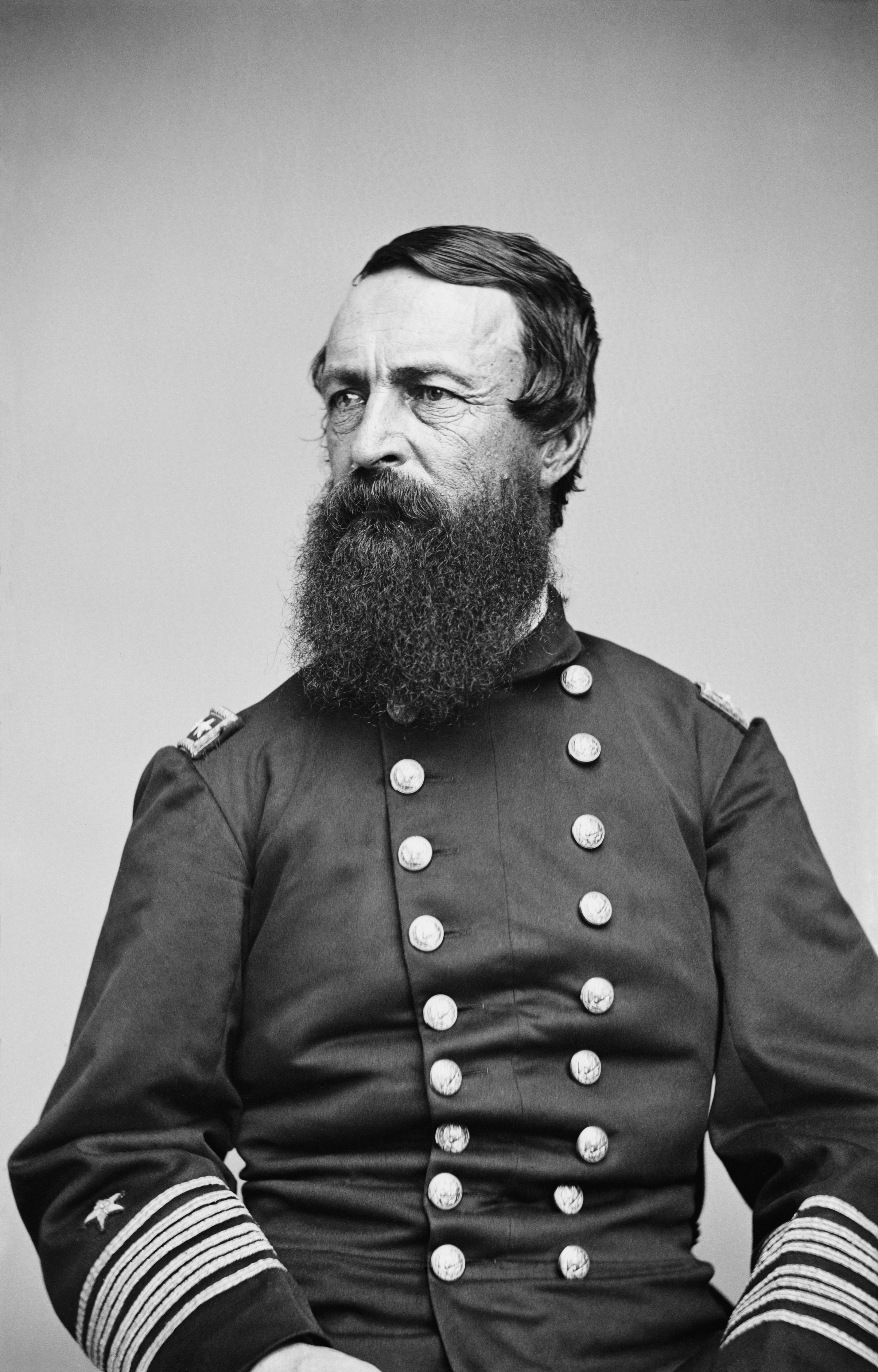

Porter designed a formidable battle fleet. It consisted of ironclads, tinclads (lightly armored gunboats), a timberclad (which used wood as armor plating), high-speed rams, three river monitors (with revolving turrets), and support vessels. Porter’s fleet carried 210 heavy guns. Sherman’s men brought their own troop transports and supply vessels. Banks also used some steamboats. The entire fleet numbered 90 boats.

In addition to the northward voyage of troops, Banks expected a force to descend upon Shreveport from Arkansas. After much debate and haggling, Major General Frederick Steele was selected to command a force from Little Rock to join Banks and the fleet in the attack on the Confederate capital.

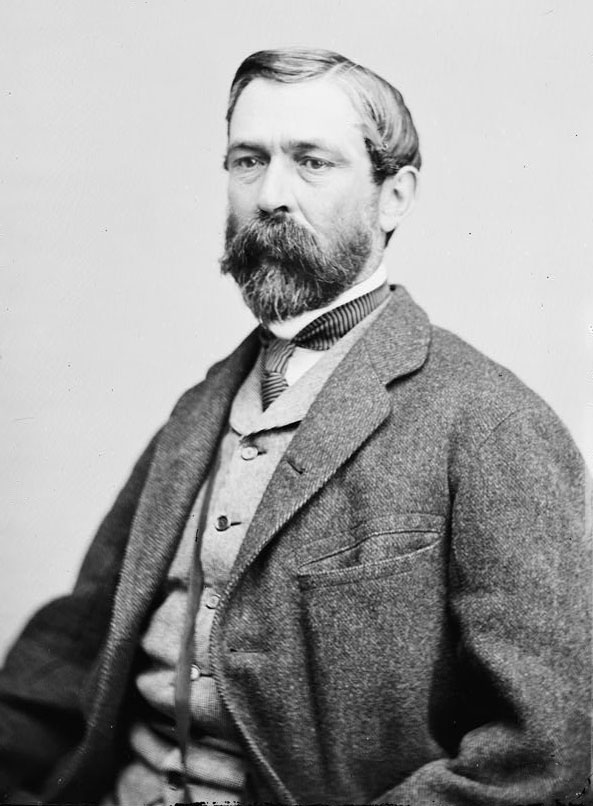

The plan appeared unstoppable. Banks would bring 20,000 troops across southern Louisiana from bases in and near New Orleans. These men of the Thirteenth and Nineteenth Corps would march overland from the railhead at Brashear (Morgan) City to Opelousas and then trek north to Alexandria. Admiral Porter and the fleet would accompany Sherman’s 10,000 veterans of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Corps under Brigadier General Andrew Jackson Smith. This contingent, traveling on transports, would enter the Red River, eliminate any Rebel forces or fortifications in its lower reaches and join Banks at Alexandria. From there, the two forces would approach Shreveport using the river roads. After the two southern forces were underway, Steele and 10,000 men, mostly cavalry, would leave Little Rock, cut across Rebel-held territory and approach Shreveport from the north or east.

Banks’ plan was complex, relying on three separate forces that were unable to contact each other. At the beginning of the campaign, the distance from Banks to Steele was 400 miles. Success would depend upon each force performing its tasks in the allotted time according to a fairly stringent schedule. The degree of complexity was an immediate problem, but Banks faced others as well. Neither President Lincoln nor his chief of staff appointed an overall commander for the operation. Banks, Steele, and Porter all held separate commands and were, to a great degree, not answerable to one another.

Porter’s choice of vessels was centered on overwhelming firepower and did not take into account the vagaries of the tortuously winding, often shallow Red River. His heaviest ships carried too deep a draft for the sandy-bottomed, snag-filled river.

Banks’ political backers desperately needed cotton to run their textile mills so boatloads of buyers accompanied him on this military operation. Their presence angered Sherman’s troops, who thought they were now part of a cotton raid and not a proper military expedition. Porter and Banks did not like each other. Banks did not trust Porter because the admiral was a close friend of both Grant and Sherman and he was jealous of the powerful trio. Porter did not trust Banks because he thought the political general was a disaster waiting to happen — incompetent and unreliable.

Banks’ greatest problem was that he had no regard for his Confederate foes and openly said that they would not fight him before he arrived in Shreveport, if then. In fact, the Confederates had been planning a warm reception for him for more than a year.

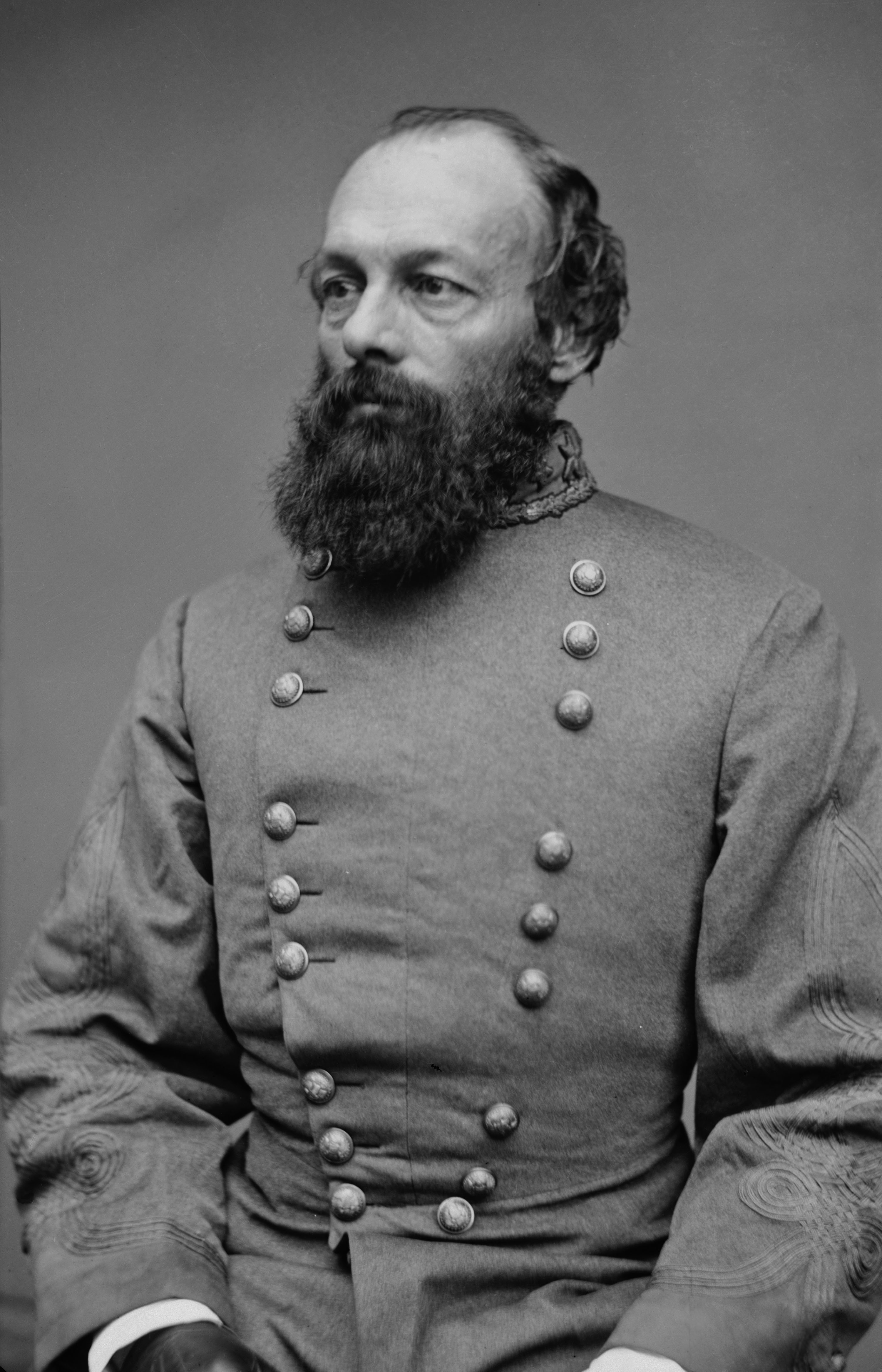

The Confederate army west of the Mississippi River was commanded by Major General Edmund Kirby Smith. Directly under him were three military districts. His commander for the Western District of Louisiana was Richard Taylor, the son of Mexican War hero and former President of the United States Zachary Taylor. Richard Taylor had served under Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley and had engaged Nathaniel Banks in that arena. He had little regard for the pompous political general from Massachusetts.

Kirby Smith and Taylor were at odds from the beginning. Smith ordered an extensive array of fortifications built along the Red River, even upstream in Arkansas. Near the mouth of the river he built Fort DeRussy. He fortified the bluffs at Grand Ecore, sixty miles south of Shreveport. He created an extensive series of fortifications at and near Shreveport. Below Shreveport his engineers prepared for the destruction of a dam, which would move most of the water from the Red River into an old channel. He also had a large steamboat placed to block the river just below this dam. Taylor believed the only defensive measure that made sense was the destruction of the dam. He had open disdain for the others.

The campaign had an inauspicious beginning on March 12 as the Eastport’ Porter’s largest ironclad, stuck on the sandbar at the mouth of the river and delayed the advance. Once freed, the fleet moved upriver four miles to the village of Simmesport. Porter and AJ. Smith used the site as a supply base. The Union officers knew that the Confederates had built a massive fort a short distance upriver and they decided to send Sherman’s veterans by land to approach Fort DeRussy from the rear while Porter’s fleet made their way upriver.

Taylor had positioned his First Division of Texans under Major General John Walker near the fort. Upon hearing of the size of the force heading his way, Walker moved his men farther north and left a skeleton force of less than 300 to man the fort. AJ. Smith’s Federals, under Brigadier General Joseph Mower, stormed the fort with ease.

Porter then dispatched the monitor Osage to Alexandria in hopes of capturing or destroying any Confederate vessels moored there. He left two of his largest ironclads at the fort to destroy it and prepared the remainder of the fleet to follow the monitor. A.J. Smith’s men boarded their transports and joined the fleet. The Osage steamed into Alexandria unmolested. The Confederates had left the town only a short time before the monitor’s arrival, losing one vessel to the rapids or “falls” which gave the parish (county) the French name of “Rapides.” Lieutenant Commander Thomas O. Selfridge, commanding the Osage accepted the town’s surrender. Porter and Smith arrived shortly afterward.

But where was Banks? There was no word of his whereabouts. The navy had reached Alexandria on schedule but Porter and Smith waited for eight days before Banks’ first troops entered the city. Banks was not with them.

The tardy Banks finally arrived in Alexandria, not with his troops, but aboard the Black Hawk, a steamboat filled with cotton speculators. Banks was furious to learn that in the meantime, the navy had been stealing cotton he had promised to his benefactors. Porter was furious that the political general was more than a week late and that he arrived on a boat with the same name as his prized flagship Black Hawk. The egos of the admiral and the general were obliterating any real chance of cooperation between them. Banks was also greeted with the news that General Grant wanted Sherman’s 10,000 men back by April 15 to join in the Atlanta Campaign.

This lit a fire under Banks and his leisurely ascent of the river now took on an air of urgency. The army marched up the river road to the first high ground at Grand Ecore, the fleet steaming beside them. At Grand Ecore Banks had to decide on the best route to Shreveport. Porter wanted to perform a reconnaissance for about three days to see what defenses the Rebels had upriver. Banks believed he could not afford the time and told Porter to meet him at a place below Shreveport called Springfield Landing. Neither commander had maps that were trustworthy. The Sixteenth Corps contingent of 2,300 men under Brigadier General Thomas Kilby Smith remained with the fleet and the remaining 7,700 men under A. J. Smith went with Banks.

A river pilot told Banks that a good road went west from Grand Ecore through Natchitoches and eventually turned north. It ran through the village of Pleasant Hill then the town of Mansfield and approached Shreveport through an unguarded southwest entrance to the city. The pilot knew the area well, but what he neglected to tell Banks was what Porter discovered on his way up river — there was another road, flat, paralleling the river, and adjacent to pastures full of enough Confederate cattle to feed the army. It turns out that the pilot, Wellington W Withenbury, leased several hundred acres of cotton land between Grand Ecore and Shreveport. He misdirected the Federals to keep his cotton from being discovered and confiscated or burned.

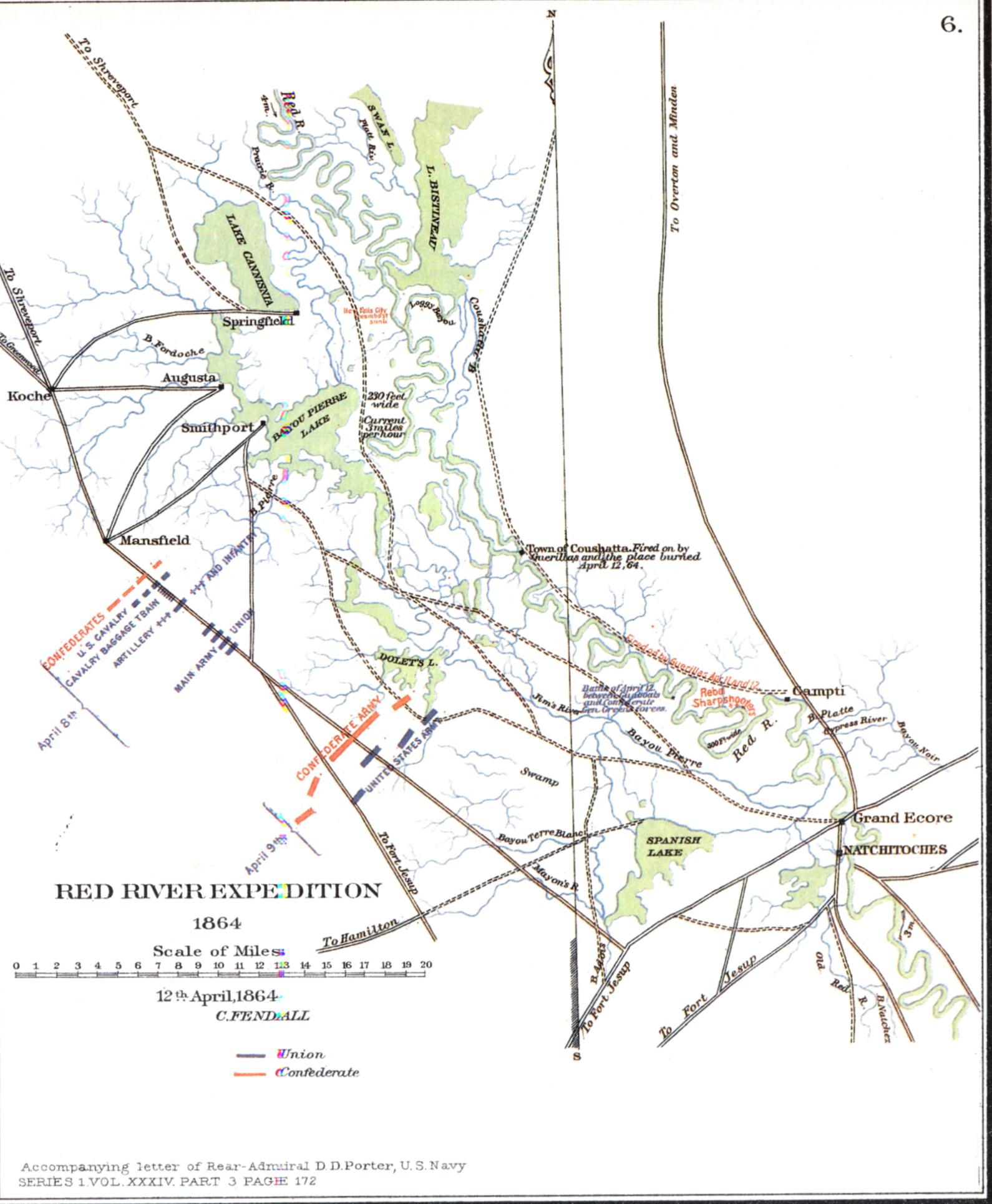

On April 6, Banks ordered his force west using a single road. His column stretched more than 20 miles. At the lead was his cavalry division of about 4,000 troopers led by Brigadier General Albert L. Lee. Half of Lee’s men were recently mounted infantry and did not know how to care for their horses, much less how to ride with confidence. Lee called them his “amateur equestrians.” Following this were the division’s 300 supply wagons, artillery units, an infantry division, 700 additional wagons, and the bulk of the Thirteenth and Nineteenth Corps. Following this long procession were A. J. Smith’s veterans, relegated to eat the dust of the whole column. The long column marched west to Los Adaes and then turned north on the Shreveport-Natchitoches stagecoach road. As the lead elements were encamping at Pleasant Hill, the tail of the column had not yet left Natchitoches.

The next morning the cavalry began the day’s march, as always, slowed by the wagons. Lee requested that the wagons be moved back and that infantry be moved up to support him, but Banks and his Nineteenth Corps commander, Major General William Buel Franklin, refused.

Three miles north of Pleasant Hill, Lee encountered Texas cavalry at Wilson’s farm, slowing his progress. At the end of the day he met them again at Carroll’s Mill and halted the column for the night.

On the morning of April 8, Lee moved forward. About 9:30 he crossed a ridge and descended into a small stream bottom. From there he crossed intermittent bands of trees and fields until he saw a long sloping ridge ahead. On it was Confederate cavalry. As Lee prepared to meet them, they fled. He cautiously approached the top of the ridge and, once there, he saw ahead of him the Confederate army arrayed about three-quarters of a mile on both sides of the road and extending at a right angle to his right. Surveying to his right, he discovered the Rebel cavalry. Lee requested help. Banks, several miles behind the position, was slow to give aid. Lee dismounted his division and formed them in an “L” to match the Confederates. He urgently requested help and it arrived in the form of the small Thirteenth Corps. With Lee’s wagons still on the road, it was difficult for reinforcements to reach him. He deployed his two artillery units, Nims’ Battery and the Chicago Mercantile Battery. Banks decided to come forward to see what the fuss was about; still believing the Confederates would only offer token resistance.

Taylor had chosen his place of battle well. He mustered perhaps as many as 10,000 men on the field. He hoped that Banks would react in a rash manner and charge him. He waited almost six hours and at four o’clock, whether by direct order or a misinterpreted comment (we will never know), his left flank began a slow elegant charge in echelon. This was not Taylor’s preferred method of attack. The Louisiana units on his left attacked Lee’s position and in short order collapsed it. The Louisiana officers decided to ride on horseback so that men could see them. It was a brave gesture, but fatal. Eleven of fourteen officers were lost within 20 minutes. Among the dead was Brigadier General Alfred Mouton, their beloved leader. Taking Mouton’s lead was Brigadier General Camille Armand Jules Marie, the Prince de Polignac, a French prince fighting for the Confederacy. As the Union right flank crumbled, Taylor’s Texas troops advanced in a line and in short order destroyed the Union left flank. Banks arrived and tried to rally the troops but they ignored him. Taylor’s men ripped through a secondary Union line at Sabine Crossroads, three-quarters of a mile behind their front line. Darkness ended the fighting as Taylor’s men pushed the Union soldiers behind Chapman’s Bayou. The Union line stiffened on the crest of the ridge above the stream. The Battle of Mansfield had been a resounding Confederate victory.

Banks ordered a retreat that night, having lost all of the cavalry wagons, many of his Nineteenth Corps wagons and several artillery pieces. Taylor thought he was just fighting the Nineteenth Corps and decided to attack along the road and to the right into the woods. He did not know about the retreat. The next morning he prepared his attack, but once he examined the ridge, he found no enemy present. The fight would take place 17 miles down the road in the village of Pleasant Hill.

Like the previous day’s fight, the Battle of Pleasant Hill began at four in the afternoon. Taylor’s right flank, advancing through heavy woods, became disoriented and wheeled to the left too soon. His Louisiana and Texas troops charged down the road and ripped through the Nineteenth Corps. The Arkansans and Missourians ran into A. J. Smith’s veterans, now rested. Four hours of intense fighting led to a bloody draw, but Banks decided to withdraw to Grand Ecore, yielding a strategic victory from a tactical tie. Taylor requested that reinforcements be sent to him to chase Banks, but Kirby Smith denied him, opting to use Taylor’s Arkansas, Missouri, and some Texas troops to counter Steele. Taylor was left with cavalry and some very weary infantry units much reduced by casualties. He dispatched 2,500 of his Texas cavalry to block the fleet at Blair’s Landing.

Porter arrived at Springfield Landing and, as usual, there was no sign of Banks. He continued upstream a short distance and saw a steamer placed across the river, blocking his progress. He also noticed that the river was falling quickly, though he could not understand why. The Rebels had blown their dam. He received word of Banks’ defeat and began his withdrawal to safer waters. Most of his fleet had passed Blair’s Landing when the Rebel cavalry arrived, but they engaged in one of the strangest battles of the Civil War. At this point 2,500 horsemen fought a river monitor, a timberclad and a transport. The fighting lasted two hours and ended in a draw with only seven casualties, though the chief of cavalry, Tom Green, was killed.

In Arkansas, Kirby Smith squandered his resources and allowed Steele to retreat to Little Rock after an inept advance on the part of the Federal troops. At the Battle of Jenkins’ Ferry, Smith lost two of three brigade commanders from the Texas Division.

The fleet arrived at Grand Ecore to meet the army and watch the river fall. After much bickering, the combined force left for Alexandria. Taylor tried to capture Banks’ men again when the Union army crossed to Cane River Island south of Natchitoches. He had too few men and, after a poor showing by Brigadier General Hamilton Bee at the south end of the island, the Union forces escaped at Monett’s Ferry.

The water at Alexandria was so low that the largest vessels of the fleet could not cross. A lieutenant colonel from Wisconsin, Joseph Bailey, came forward and described a dam he could build to raise the water level. Though Porter and Banks were skeptical, they allowed him to try it. The dam — actually as series of structures — worked, raising the water level so the fleet could pass the rapids. Taylor could only watch the escape. He had too few men to make an attack.

The Union army began its retreat. Taylor tried valiantly to trap them without success. An artillery duel was fought at Mansura, near Fort DeRussy on May 16. Few casualties resulted. A last effort to halt the retreat was made at Yellow Bayou on May 18. Bailey again came to the fleet’s rescue. This time high water had flooded the Atchafalaya River so he created a pontoon bridge of transports moored side-by-side to allow the army to cross.

Banks was humiliated by the debacle and lost any possibility of running for the presidency. He spent the remainder of the war in New Orleans or in Washington testifying before Congress. Taylor and Kirby Smith continued to have heated arguments and Smith attempted to have Taylor removed from command. However the Confederate High Command promoted Taylor to lieutenant general and gave him a command east of the Mississippi River. Kirby Smith held the last Confederate command to surrender. A. J. Smith never did rejoin Sherman, but fought in Tennessee. Sherman was denied the use of his 10,000 men. Porter, who asked to never again be on a river command, was named commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Prince Camille de Polignac was knighted by Emperor Napoleon for heroism and was presented to Queen Victoria of England on the emperor’s behalf. He named his son Mansfield.

Gary Joiner is a cartographer and historian in Louisiana. He is the co-author of Historic Shreveport-Bossier City with Marguerite R. Plummer and co-author of Red River Steamboats with Eric J. Brock. His book One Damn Blunder from Beginning to End: The Red River Campaign of 1864 was published in February 2003 by Scholarly Resources.

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Joiner, Gary D. “The Red River Campaign: March 10 - May 22, 1864.” Civil War Trust: Saving America's Civil War Battlefields. Web. 20 Sept. 2015. <http:// www.civilwar. org/ battlefields/ mansfield/ mansfield-history-articles/ redriver joiner.html>. © Gary D Joiner. Used by permission. All rights reserved.