Louisiana Anthology

Major Arséne Lacarriére Latour.

Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana in 1814-15.

DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA, to wit:

BE IT REMEMBERED, That on the sixth day of March, in the fortieth year of the independence of the United States of America, A. D. 1816,

Arsene Lac` arriere Latour,

of the said district, hath deposited in this office the title of a Book, the right whereof he claims as Author, in the words following, to wit:

Historical Memoir of the war in West Florida and Louisiana in 1814-15. with an Atlas. By major A. Lacarriere Latour, principal engineer in the late seventh military district United States' army. Written originally in French, and translated for the author, by H. P. Nugent, esqr.

Bis Tusci Rutulos egere ad contra reversos,

Bis rejecti armis respectant terga tegentes.

Turbati fugiunt Rutuli————————

Disjectique duces, desolatique mauipli,

Tula petunt——————————

Virg.

In conformity to the act of congress of the United States, entitled, "An act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books to the authors and proprietors of such copies during the times therein mentioned." And also to the act, entitled, "An act supplementary to an act, entitled, " An act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies during the times therein mentioned, and extending the benefits thereof to the arts of designing, engraving, and etching historical and other prints."

DAVID CALDWELL,

Clerk of the District of Pennsylvania.

TO

MAJ. GEN. ANDREW JACKSON.

Sir,

Allow me to offer you the following pages, in which I have endeavoured to record the events of that memorable campaign which preserved our country from conquest and desolation. The voice of the whole nation has spared me the task of showing how much of these important results are due to the energy, ability and courage of a single man.

Receive, sir, with this inadequate tribute to your high merits, the assurance of respect and devotion with which I have the honour to be,

Sir,

Your most obedient

and humble servant,

A. LACARRIERE LATOUR.

New

Orleans, August 16, 1815.

PREFACE.

The immense debt of Great Britain, and the expenses of a war carried on for nearly twenty years with hardly any intermission, having exhausted the ordinary sources of her riches, while the war continued to rage with greater fury than ever, she found herself compelled to create new resources to enable her to persevere in the arduous struggle in which she was engaged. For this purpose the rights of neutral nations, founded on the principles of natural equity, established for many ages by the unanimous consent of civilized nations, and secured by the faith of a long succession of treaties, were openly violated by the English government, which, prompted by its inordinate ambition, wished to appropriate to itself the lives and fortunes of their peaceable citizens. To accomplish this purpose, it became necessary to set aside those principles which, until then, had been universally acknowledged, and to substitute new political axioms in their stead. By the mere arbitrary declaration of the British cabinet, the right of blockade was extended over the most extensive coasts, which all the maritime power of the world combined could not have

blockaded

with effect. The obsolete right of searching neutral ships for enemy’s property, this absurd remnant of the barbarous jurisprudence of the dark ages, justly rejected by the more enlightened policy of later times, was revived and enforced with increased severity, and the right of pressing seamen on board of neutral vessels was claimed as a consequence of the same principle, while, by a further extension of the rights of belligerents, the trade of neutrals with the colonial possession of enemies, was at times entirely prohibited, and at others partially tolerated, by decrees which the belligerent government could construe at pleasure, and which only served to allure the unwary, and secure a certain prey to the hungry swarm of British cruisers. Thus the plunder of neutrals, and the impressment of their seamen, were erected into a system,

the true principles of which could only be discovered from its effects.

The United States of America, whose industrious citizens carried on a regular and immense commerce with all the nations of the globe, which had long excited the jealousy of their powerful rival, experienced more than any other nation the pernicious effects of the new system, conceived and executed by this overbearing state; and indeed it appeared to have been established principally with a view to check their commercial pursuits. The American vessels were plundered, detained, or confiscated. The mariners were impressed upon the most frivolous pretences, put on board the ships of war of His Britannic majesty, and subjected to the most rigorous treatment, in order to compel them to shed their blood in a cause in which they were not interested. On the high seas, in neutral harbours, upon the coasts, and even in the waters exclusively subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, the American seamen were seized by the petty officers of the British navy, who constituted themselves judges, de facto, of the most sacred prerogatives of man, and from the mere similarity of names, or, as their caprice dictated, transformed a free citizen into a slave, without regard to the place of his birth, or to the natural and unalienable right, that all men have to choose their country. The sacred flag of the government itself was no longer a sufficient protection; the sanctuary of a ship of war was violated — freemen were dragged by force and carried away, in savage triumph, from an American frigate sailing quietly, in the midst of a profound peace; — the most ignominious punishment —— But I forbear. — This unheard of outrage, which then, for the first time, astonished the world, lias been since sufficiently avenged.

The American government at first only opposed to these enormous violations of the law of nations mild and conciliating representations, and pacific measures, which produced only some partial and momentary disavowals and reparations. With the humane view of saving the country from the horrors of war, and in hopes of inducing England to adopt principles of equity and moderation, by making her government perceive that the people of America would never submit to measures so tyrannical and degrading, the national legislature resolved to interdict every sort of foreign commerce, and laid an embargo on all the ports of the United States.

This measure received the approbation of the whole nation. The citizens no longer deceived themselves with respect to the views and motives of the British government. They preferred submitting for a time to the inconveniences which the stagnation of commerce would naturally produce, to seeing their country exposed to endless humiliations, or compelled to engage in a war, the effects of which could not be calculated. For it was believed by many, that the constitution of the United States was only suited for a state of peace, and that war would infallibly produce a dissolution of the union. These considerations were weighty, and might well induce a nation to pause before it involved itself in a contest which seemed to threaten such a fatal issue. — The embargo was then a wise measure, as there appeared no alternative between it and war. Indeed it is probable that if it had been continued, we might have avoided a recourse to arms, and compelled Great Britain to return to the practice, if not to the principles of justice.

But it was not so ordered, and after little more than one year thte embargo was removed. Let us throw a patriotic veil over the causes which produced this unexpected step. It does not belong to me to inquire into its expediency or its motives. Such an inquiry is entirely foreign to the purposes of this work. As it was to be expected, the resumption of maritime commerce was followed by a renewal of spoliations on the part of Great Britain, who mistook our patience for weakness, and ascribed to timidity and other unworthy motives, a conduct which merely arose from an earnest and laudable desire to preserve peace, and avoid the effusion of human blood. Far from foreseeing the privations and hardships to which the people of America would submit, and the exertions which they were capable of making, if driven to extremity, Britain, blinded by her pride, saw in the removal of the embargo nothing else than the result of an inordinate thirst for maritime commerce, and an effeminate attachment to the luxuries with which she had been in the habit of supplying us. As little she foresaw how much she would have to suffer before she discovered her mistake — how much of her treasure was to be spent, and of her blood was to be spilt, before she should be taught to know the spirit and perseverance of a nation which she affected to view with contempt. At last the repetition of injuries filled the measure of American longanimity, and War was solemnly declared by the United States, on the 18th of June, 1812. So little premeditated was this measure — so much was it produced by a sudden burst of the national indignation, that no preparations had been made to support the dreadful contest that was now about to take place. Our military establishment was hardly sufficient to afford garrisons for the most exposed points of our widely-extended frontier — the numerous ports upon our sea-board were left exposed, unguarded and unfortified, and our marine consisted only of a few ships of war. But the bravery and energy of our citizens promised abundant resources for our military operations on the land side, and the skill and martial ardour of our seamen, and particularly their excellent commanders, presaged certain and glorious triumphs on the ocean. The riches of an immense soil, and the activity and patriotism of its inhabitants, gave a sufficient pledge to the government to justify the reliance which they had placed on the aid and co-operation of the nation, which, on another and ever-memorable occasion, had proved to the world that there are no sacrifices that it is not ready to make in support of its independence, and in the defence of its just rights.

Thus the United States were forced into a war which they had not provoked; — America took up arms in support of her rights, and for the preservation of her national honour, with a firm determination not lay them down until the object should be attained. Providence blessed our efforts, and our arms were crowned with the most brilliant triumphs over those of our enemy. The army and navy exhibited a noble rivalship of zeal, devotion, and glory. In the one Lawrence, Bainbridge, Decatur, Perry, M‘Donough, Porter; — in the other Pike, Scott, Brown, Jackson, and many more, proved to the enemy, and to the world, that we possessed resolution to defend our rights, and power to avenge our injuries.

The relation of these various exploits is the proper province of history. An abler pen than mine will one day consecrate to posterity this monument of American fame. My humble task has been to collect a part of the materials that may serve to erect it, and which I offer in the present work.

The volume which I present to the public is devoted to the relation of the campaign of the end of 1814 and beginning of 1815: that is to say, from the first arrival of the British forces on the coast of Louisiana, in September, until the total evacuation, in consequence of the treaty of peace, including a period of about seven months. During that space of time, particularly from the 14th of December to the 19th of January, events of the highest importance succeeded each other with rapidity; but it was in the short period, from the 23d of December, the day of the landing of the British troops, to the memorable 8th of January, that the American arms acquired that lustre which no time can efface.

Nec poterit tempus, nec edax abolere vetustas.

The preparations which the British government had made for the conquest of Louisiana were immense. So certain were they of complete success, that a full set of officers, for the administration of civil government, from the judge down to the tide-waiter, had embarked on board of the squadron with the military force. The British speculators, who are always found in the train of military expeditions, had freighted a part of the transports for conveying the expected booty, which they estimated beforehand at more than fourteen millions of dollars. The British government well knew that they could not keep Louisiana, even if they should obtain the possession of it. They were not ignorant that the western states could pour down, if necessary, one hundred thousand men to repel the invaders; they therefore could only rely on a momentary occupation, which they hoped, nevertheless, to prolong sufficiently to give them time to pillage and lay waste the country. Therefore they had neglected no means of securing the plunder which they expected to make. Such, indeed, was their certainty of success that it was not thought necessary in Europe to conceal the object of the expedition. At Bordeaux, at the time of the embarkation of the troops, the conquest of Louisiana was publicly spoken of as an enterprize that could not fail of succeeding, and the British officers spoke of that campaign as of a party of pleasure, in which there was to be neither difficulty nor danger. It is even asserted, (though I will not vouch for the truth of the assertion) that the prime minister of Great Britain, lord Castlereagh, being at Paris when the news of the capture of Washington arrived there, boasted publicly that New Orleans and Louisiana would soon be in the power of his

countrymen.

Yet this formidable expedition had already sailed from Europe when its precise object and destination were not known in America. It will be seen, in the course of this memoir, that about the beginning of December, the greatest part of the British force had arrived on our coast, when general Jackson had hardly sufficient time to make the first preparations for defence. Without fearing to be accused of flattery, we may justly call him (under God) the saviour of Louisiana: for, in the space of a few days, with discordant and heterogeneous elements, he created and organized the little army which succeeded so well in humbling the British pride. It is true, that the love of country, the hatred of England, the desire of avenging the outrages which we had suffered from that haughty power, fired every heart; — but all this would have availed nothing without the energy of the commander-in-chief: which will appear so much the more extraordinary, when it is considered that he was constantly sick during this memorable campaign, so much so that he was on the point of being obliged to resign his command. Although his body was ready to sink under the weight of sickness, fatigue, and continual watching, his mind, nevertheless, never lost for a moment that energy which he knew so well how to communicate to all that surrounded him. To obstacles, which to others would have appeared insurmountable — to the want of the most indispensable supplies for the army, he opposed the most constant perseverance, until he succeeded either in obtaining what was required, or in creating supplementary resources.

I have already said, that the energy manifested by general Jackson spread, as it were, by contagion, and communicated itself to the whole army. I shall add, that there was nothing which those who composed it did not feel themselves capable of performing, if he ordered it to be done; it was enough that he expressed a wish, or threw out the slightest intimation, and immediately a crowd of volunteers offered themselves to carry his views into execution. Such perfect harmony — so entire and reciprocal a confidence between the troqps and their commander, could not fail to produce the happiest effects. Therefore, although our army was, as I have already observed, composed of heterogeneous elements, of men speaking different languages, and brought up in different habits, the most perfect union and harmony never ceased for a moment to prevail in our camp. No one can better than myself bear testimony to the good understanding that reigned among our troops. In the course of the labours at the fortifications, which were erected under my direction, I had occasion to employ soldiers in fatigue duty, who were drafted by detachments from each of the several corps. These men were kept hard at work even to the middle of the night, and by that means lost the little portion of sleep which they could have snatched in the interval of their military duties. I was almost constantly with them, superintending their labours; but I may truly say, that I never heard among them the least murmur of discontent, nor saw the least sign of impatience. Nay, more, four-fifths of our army were composed of militia-men or volunteers, who, it might be supposed, would with difficulty have submitted to the severe discipline of a camp, and of course would often have incurred punishment; yet nothing of the kind took place; and I solemnly declare, that not the smallest military punishment was inflicted. This is a fact respecting which I defy contradiction in the most formal manner. What, then, was the cause of this miracle? The love of country, the love of liberty. It was the consciousness of the dignity of man — it was the noblest of feelings, which pervaded and fired the souls of our defenders — which made them bear patiently with their sufferings, because the country required it of them. They felt that they ought to resist an enemy who had come to invade and to subdue their country; — they knew that their wives, their children, their nearest and dearest friends were but a few miles behind their encampment, who, but for their exertions, would inevitably become the victims and the prey of a licentious soldiery. A noble city and a rich territory looked up to them for protection; those whom their conduct was to save or devote to perdition, were in sight, extending to them their supplicating hands. Here was a scene to elicit the most latent sparks of courage. What wonder, then, that it had so powerful an effect on the minds of American soldiers — of Louisianian patriots! Every one of those brave men felt the honour and importance of his station, and exulted in the thought of being the defender of his fellow citizens, and the avenger of his country’s wrongs. Such are the men who will always be found, by those who may again presume to insult a free nation, determined to maintain and preserve her rights.

I have in this work endeavoured to relate in detail, with the utmost exactness and precision, the principal events which took place in the course of this campaign. I have related facts as I myself saw them, or as they were told me by credible eye-witnesses. I do not believe, that through the whole of this narrative I have swerved from the truth in a single instance; if, however, by one of those unavoidable mistakes to which every man is subject, I have involuntarily mis-stated, or omitted to state, any material circumstance, I shall be ready to acknowledge my error whenever it shall be pointed out to me. I therefore invite those of my readers, who may observe any error in my narrative, to be so good as to inform me of it, that I may correct it in a subsequent edition.

Although several documents contained in the Appendix have been already published, I have nevertheless thought proper to insert them as necessary parts of the whole, and as the vouchers of the facts which I have related. I might, indeed, have reduced some of them to the form of an extract, but they would thereby have lost something of their original character. Some might, perhaps, have doubted their authenticity. I therefore preferred giving them entire.

HISTORICAL MEMOIR

OF THE

WAR IN WEST FLORIDA AND LOUISIANA.

INTRODUCTION.

The abdication of the emperor of the French, and the temporary pacification of Europe, consequent on that event, enabled Great Britain to dispose of the numerous forces which she had till then employed against France. The British cabinet resolved that the war against the United States should be vigorously prosecuted. The British presses were set to work, in order to prepare the mind of the nation, and give it a bias favourable to the views of the government. The same journals which for several years had been filled with invectives against the emperor Napoleon, now began to vilify the chief magistrate of the United States. The artifices so long employed to alienate the French nation from her chief, were now resorted to against Mr. Madison. The friends, or rather the agents of Britain, in die United States, repeated the same calumnies, invented the same fictions, advanced the same specious falsehoods, to destroy the President’s popularity, and incite the nation to an insurrection against the government, which, according to British writers and emissaries, had drawn her into an impolitic, unjust, parricidal and sacrilegious war. It was, they maintained, become necessary to punish the inhabitants of the United States, for having preferred a free government, of their own choice, to that of a British king: nay, the United States must be reduced to their original colonial subjection, as a chastisement for their having dared to declare war against Great Britain, rather than suffer the lives and fortunes of their citizens to be forcibly employed in support of die British flag; and for their having presumed to oppose those pretended maritime rights, to which all the governments of Europe had thought proper to submit.

The ministerial papers denounced the Americans as rebels, the devoted objects of vengeance. British publications now breathed the same rage as at the period of the declaration of our independence; and the ministerial writers had recourse to the grossest scurrilities in their endeavours to vilify our government. As they pretended that it was not against France that they had waged so long a war, but against the chief who presided over her councils; so now they affected to proclaim that their hostilities were not directed against the people of the United States, nor against the American nation, but merely against the leader of a dominant faction. It was to restore to our nation the enjoyment of prosperity, that they were determined to overturn our government! It was obvious that the cessation of hostilities in Europe, would afford Britain the means of executing a part of her threats; and reflecting men considered the fall of the emperor of the French (so long wished for by the friends of Britain) as a sure presage that we should soon have to contend with a formidable British force by sea and land; nor was it long before these apprehensions were realized.

On the frontiers of Canada, the British had hitherto conducted the war with much dexterity and intrigue, but without any considerable number of troops. The courage of our soldiers could not remedy the faults of our generals, and the two first campaigns produced nothing more than some brilliant exploits, some particular instances of bravery, that could have no influence on great military operations. Courage without military tactics, an ill-disciplined army conducted without any fixed plan, with a defective system of organization, were the means with which we long opposed the British troops; and it may be truly said that the two first campaigns in Canada were consumed in a war of observation, and in the taking and retaking of a few posts. The British, by all possible means of seduction, had stirred up against us a great number of Indians on the north-western confines of the United States, and excited them to commit depredations on our frontiers, and massacre our citizens. History cannot record all the atrocities committed by those allies of Great Britain, some of which are of such a description that the most credulous would disbelieve them, were not the facts supported by the most creditable witnesses and the most authentic proofs.

Experience at last opened the eyes of our government, and more numerous armies, under able and faithful officers, were sent into Canada, to carry on the war more effectually. It is foreign from the design of this work, to enter into any discussion on that subject; and I will merely observe that it was in some measure owing to a defect in the law then in force for calling out the militia, that our military operations in Canada, during the two first campaigns, were attended with so little success. I allude to the law which called out certain portions of the militia for six months only, at the expiration of which term the men were allowed to return home. Independently of the time necessary to repair from the middle states to the frontiers of Canada, or to Louisiana, six months are hardly sufficient to train a soldier to military discipline and evolutions, so as to render him fit to contend in the field against veteran troops. A subsequent law has, indeed, partly remedied this evil, by prolonging the time of service to twelve months; but even this term would probably be insufficient, had we to carry on a war with vigour.

The arrival of reinforcements to the British army in Canada, was the prelude to more extensive operations. The taking of Washington, and the several attacks made on different points of the Chesapeake, sufficiently evinced the intention of the British government, to endeavour to execute the threats denounced against us through their newspapers. The burning of Havre-de-Grace, the excesses committed at Hampton, and at Frenchtown, enabled us to form a just idea of the men who professed the intention of delivering us from a "government ridiculously despotic," and who in the meantime insulted our wives and daughters, destroyed or plundered our property, and indiscriminately set fire to humble cottages and stately palaces. The capitol itself, that noble monument that might have commanded respect even from barbarians, became a prey to the flames; and that we should not remain in doubt as to the fate we were to expect, the commander of the British naval forces, in an official communication to the secretary of state, explicitly avowed his determination to continue the same system of inhuman warfare, and to lay waste and destroy the American coast,

wherever assailable.

From that moment all eyes were opened; the cry of indignation was heard from one extremity of the union to the other, and all minds were now bent on an obstinate and determined resistance. It was evident to all that we had no longer to contend for the precarious possession of an inconsiderable extent of country, but that we were called on to defend our wives and children from British insult and brutality; our fortunes from the rapacity of British invaders, and our homes from pillage, fire and devastation. Those who had hitherto considered the war only as an honourable contest between two nations, mutually esteeming each other, but set at variance by conflicting interests, were now convinced that our enemies were determined to wage against us a war of extermination, and that we had to repel a savage foe, who came to cover our country with mourning and desolation. The Halifax papers announced the embarkation of troops that had composed part of lord Wellington’s army. In the list of the regiments and of the general officers, appear several of the former and of the latter who since came to the banks of the Mississippi. The expedition against New Orleans was to consist of eighteen thousand men. The same papers predicted that the calamities of war would be severely and extensively felt by the inhabitants of the United States.

From that time it was generally believed that the British would attack the southern states in the ensuing autumn or winter, and Louisiana was particularly pointed out as their most probable object of invasion: yet so ill does the general government appear to have been served by its agents in that remote part of the union, that as late as in the month of September, nothing had been done in the way of effectual preparations, to put that country in a state of defence.

Louisiana, which was particularly marked out as the principal point against which was to be directed a formidable British force, with a considerable extent of coast, numerous communications by water, and with hardly any fortified points, open on all sides, having in its neighbourhood a Spanish settlement freely admitting the enemy’s ships, and a great proportion of whose population was disposed to aid him, had no force on which to rely for the defence of her shores, except six gun-boats and a sloop of war. From the gallant defence made by the brave crews of these vessels, we may judge what would have been effected by a number proportionate to the extent of coast to be defended. Fort Plaquemines, that of Petites Coquilles, and fort Bowyer at Mobile point, were the only advanced points fortified; and none of them capable of standing a regular siege.

It may now be made known, without any other danger than that of its appearing incredible, that Louisiana, whose coasts are accessible to such flat-bottomed vessels as are used in conveying mortars, had but two of these engines which belonged to the navy, and which were landed from bomb-ketches that had been condemned. Nor is this all: there were not a hundred bombs of the calibre of those mortars; nor, indeed, could much advantage be derived from them, however well served or supplied. Professional men will understand, that from the construction of their carriages, they were only fit to be mounted on board of vessels, and by no means calculated for land batteries.

The fort of Petites Coquilles was not finished at the time of the invasion, nor was it in a condition to make an ordinary resistance. As to fort Bowyer, at Mobile point, it will appear from the particular account given in this work of the two attacks it sustained, that the brave garrison defending it did all that could be reasonably expected from its local situation and means of resistance. Such was the inconsiderable defence that protected the shores of Louisiana, and covered a country that has an extent of coast of upwards of six hundred miles, and of which even a temporary possession by an enemy might be attended with consequences baneful to the future prosperity of the western states. The general government might and ought to have been well informed of the vulnerable points of Louisiana. Accurate maps of the country on a large scale had been made, by the engineer B. Lafon and myself, and delivered to brigadier-general Wilkinson, who, it is presumable, did not fail to forward them to the secretary of war. That part of the state, in particular, by which the enemy penetrated, was there laid down, and in 1813 brigadier-general Flournoy ordered major Lafon, then chief engineer of the district, to draw up an exact account of all the points to be fortified for the general defence of Louisiana. The draughts, which were numerous, and formed an atlas, were accompanied with very particular explanatory notes. That work, which reflects great credit on its author, pointed out in the most precise and clear manner what was expedient to be done, in order to put the country in a state of security against all surprise. I have always understood that those draughts were ordered and executed for the purpose of being sent to the then secretary of war, to enable the government to determine in their wisdom the points proper to be fortified. To what fatality then was it owing, that Louisiana, whose means of defence were so inadequate; which had but a scanty white population, composed, in a great proportion, of foreigners speaking various languages; so remote from any succours, though one of the keys of the union — was so long left without the means of resisting the enemy? I shall be told that to fortify the coast in time of peace, were to incur an unnecessary expense. This position I by no means admit; but I further observe that the war had already existed two years; and we ought to have presumed, had positive proof been wanting, that the British, having numerous fleets, and every means of transporting troops to all points of the coast of the United States, would not fail to make an attempt against Louisiana; — a country which already by its prodigious and unexampled progress in the culture of sugar, was become a dangerous rival to the British colonies. The city of New Orleans contained produce to a vast amount. The cotton crops of the state of Louisiana and the Mississippi territory, accumulated during several years, were stored in that city, surrounded with considerable plantations, having numerous gangs of slaves. It was, in a word, the emporium of the produce of a great portion of the western states. The Mississippi on which it lies, receives the streams that water upwards of a million of square miles, and wafts to New Orleans the annually increasing productions of their fertile banks. — It is by the Mississippi and the rivers emptying into it, that the communication is kept up between the western and northern states. — And by the Mississippi and the Missouri, there will, at no distant period, be carried on, without difficulty, or with very little obstruction, the most extensive inland navigation on the globe.

All these advantages were calculated to excite the cupidity of the British, and inspire them with the desire of getting possession of a country which, besides its territorial wealth, insured to whoever might hold it, an immediate control over the western states. In possessing themselves of Louisiana, the least favourable prospect of the enemy was the plunder of a very considerable quantity of produce, the destruction of a city destined to become commercial, and opulent in the highest degree, and the ruin of numerous plantations which must one day rival in their productions, those of the finest colonies of European nations. Their other prospects, less certain indeed, but in which they were not a little sanguine, were the separation of the western states from the rest of the union; the possibility of transferring the theatre of war to the westward, by the possession of the Mississippi, and effecting a junction with their army in Canada; and lastly, being masters of Louisiana, to import by the river their various manufactures, and secure to themselves the monopoly of the fur trade.

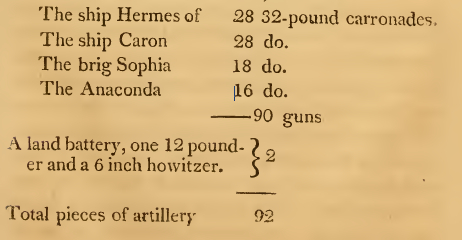

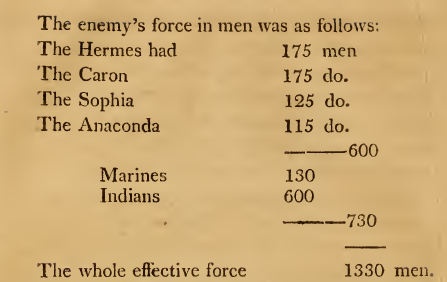

Let us now see in what manner the British began to execute their hostile designs against Louisiana: In the course of the summer of 1814, the brig Orpheus had landed arms and officers in the bay of Apalachicola, and entered into arrangements with the Creeks, to act against fort Bowyer at Mobile point, justly looked upon as a place the possession of which was of the greatest importance towards the execution of the grand operations projected against Louisiana. The British officers diligently executed the object of their instructions, and had completely succeeded in rallying under their standard all the tribes of Indians living to the cast of the Chactaws, when an expedition of some troops, on board the sloops of war Hermes and Caron, sailed from Bermuda under the command of colonel Nicholls, of the artillery, an enterprising, active, and brave officer, and on the 4th of August touched at the Havanna, in hopes of obtaining the co-operation of the Spanish governor, the assistance of some gun-boats and small vessels, with permission to land their troops and artillery at Pensacola. On the refusal of the captain-general, they sailed for Pensacola, determined to land there; although the captain-general had positively refused to grant them permission. (See Appendix, No. 2.)

Colonel Nicholls accordingly landed at Pensacola, where he established his head-quarters, and enlisted and publicly drilled Indians, who wore the British uniform in the streets.

The object of that inconsiderable expedition appears to have been to sound the disposition of the inhabitants of the Floridas and Louisiana; to procure the information necessary for more important operations, and to secure pilots to conduct the expedition on our coast and in our waters, rather than to attempt any thing of importance.

Colonel Nicholls directed captain Lockyer of the brig Sophia, to convey an officer to Barataria with a packet for Mr. Lafitte, or whoever else might be at the head of the privateers on Grande Terre.

To give a correct idea of that establishment at Barataria, of which so much has been said, it is necessary to enter into some details, by a digression which will naturally bring us back to our subject.

BARATARIA.

At the period of the taking of Guadaloupe by the British, most of the privateers commissioned by the government of that island, and which were then on a cruise, not being able to return to any of the West India islands, made for Barataria, there to take in a supply of water and provisions, recruit the health of their crews, and dispose of their prizes, which could not be admitted into any of the ports of the United States; we being at that time in peace with Great Britain. Most of the commissions granted to privateers by the French government at Guadaloupe, having expired some time after the declaration of the independence of Carthagena, many of the privateers repaired to that port, for the purpose of obtaining from the new government, commissions for cruising against Spanish vessels. They were all received by the people of Carthagena with the enthusiasm which is ever observed in a country that for the first time shakes off the yoke of subjection; and indeed a considerable number of men, accustomed to great political convulsions, inured to the fatigues of war, and who by their numerous cruises in the gulf of Mexico and about the West-India islands, had become well acquainted with all those coasts, and possessed the most effectual means of annoying the royalists, could not fail to be considered as an acquisition to the new republic.

Having duly obtained their commissions, they in a manner blockaded for a long time all the ports belonging to the royalists, and made numerous captures, which they carried into Barataria. Under this denomination is comprised part of the coast of Louisiana to the west of the mouths of the Mississippi, comprehended between Bastien bay on the east, and the mouths of the river or bayou la Fourche on the west. Not far from the sea are lakes called the great, the small, and the larger lake of Barataria, communicating with one another by several large bayous with a great number of branches. There is also the island of Barataria, at the extremity of which is a place called the Temple, which denomination it owes to several mounds of shells thrown up there by the Indians, long before the settlement of Louisiana, and which from the great quantity of human bones, are evidently funereal and religious monuments.

The island is formed by the great and the small lakes of Barataria, the bayou Pierrot, and the bayou or river of Ouatchas, more generally known by the name of bayou of Barataria; and finally the same denomination is given to a large basin which extends the whole length of the Cypress swamps, lakes, prairies and bayous behind the plantations on the right bank of the river, three miles above New Orleans, as far as the gulf of Mexico, being about sixty miles in length and thirty in breadth, bounded on the west by the highlands of la Fourche, and on the east by those of the right bank of the Mississippi. These waters disembogue into the gulf by two entrances of the lake or rather the bayou Barataria, between which lies an island called Grande Terre, six miles in length and from two to three miles in breadth, running parallel with the coast. In the western entrance is the great pass of Barataria, which has from nine to ten feet of water. Within this pass, about two leagues from the open sea, lies the only secure harbour on all that coast, and accordingly this is the harbour frequented by the privateers, so well known by the name of

Baratarians.

Social order has indeed to regret that those men, mostly aliens, and cruising under a foreign flag, so audaciously infringed our laws as openly to make sale of their goods on our soil; but what is much more deplorable and equally astonishing is, that the agents of government in this country so long tolerated such violation of our laws, or at least delayed for four years to take effectual measures to put a stop to these lawless practices. It cannot be pretended that the country was destitute of the means necessary to repress these outrages. The troops stationed at New Orleans were sufficient for that purpose, and it cannot be doubted but that a well conducted expedition would have cleared our waters of the privateers, and a proper garrison stationed at the place they made their harbour, would have prevented their return. The species of impunity with which they were apparently indulged, inasmuch as no rigorous measures were resorted to against them, made the contraband trade carried on at Barataria, be considered as tacitly tolerated. In a word, it is a fact no less true than painful for me to assert, that at Grande Terre, the privateers publicly made sale, by auction, of the cargoes of their prizes. From all parts of Lower Louisiana people resorted to Barataria, without being at all solicitous to conceal the object of their journey. In the streets of New Orleans it was usual for traders to give and receive orders for purchasing goods at Barataria, with as little secrecy as similar orders are given for Philadelphia or New York. The most respectable inhabitants of the state, especially those living in the country, were in the habit of purchasing smuggled goods coming from Barataria. The frequent seizures made of those goods, were but an ineffectual remedy of the evil, as the great profit yielded by such parcels as escaped the vigilance of the custom-house officers, indemnified the traders for the loss of what they had paid for the goods seized; their price being always very moderate, by reason of the quantity of prizes brought in, and of the impatience of the captors to turn them into money, and sail on a new cruise. This traffic was at length carried on with such scandalous notoriety, that the agents of government incurred very general and open reprehension, many persons contending that they had interested motives for conniving at such abuses, as smuggling was a source of confiscation, from which they derived considerable benefit.

It has been repeatedly asserted in the public prints throughout the union, that most of those privateers had no commissions, and were really pirates. This I believe to be a calumny, as I am persuaded they all had commissions either from Carthagena or from France, of the validity of which it would seem the government of those respective countries were alone competent judges.

The privateers of Barataria committed indeed a great offence against the laws of the United States in smuggling into their territory goods captured from nations with which we were at peace; and for this offence they justly deserved to be punished. But in addition to this acknowledged guilt, to charge them with the crime of piracy, when on the strictest inquiry no proof whatsoever of any act amounting to this species of criminality has been discovered, and though since the pardon granted to them by the president of the United States, they have shown their papers and the exact list of the vessels captured by them, to every one who chose to see them, seems evidently unjust. Without wishing to extenuate their real crime, that of having for four years carried on an illicit trade, I again assert that the agents of government justly merit the reproach of having neglected their duty. The government must surely have been aware of the pernicious consequences of this contraband trade; and they had the means of putting a stop to it. It is true that partial expeditions had been fitted out for that purpose; but whether through want of judgment in the plan, or through the fault of the persons commanding those expeditions, they answered no other purpose than to suspend this contraband trade in one part, by making it take a more western direction. Cat island, at the mouth of the bayou or river la Fourche, became the temporary harbour of the privateers, whose vessels were too well armed to apprehend an attack from land troops in ordinary transports. Hence the troops stationed at Grande Terre, la Fourche, &c. could do no more than prevent the continuance of the illegal trade, while they were on the spot; but on their departure, the Baratarians immediately returned to their former station.

There have been those who pretended that the privateers of Barataria were secretly encouraged by the English, who were glad to see a commerce carried on that must prove so injurious to the revenue of the United States. But this charge is fully refuted by this fact, that at different times the English sought to attack the privateers at Barataria, in hopes of taking their prizes, and even their armed vessels. Of these attempts of the British, suffice it to instance that of the 23d of June, 1813, when two privateers being at anchor off Cat island, a British sloop of war anchored at the entrance of the pass, and sent her boats to endeavour to take the privateers; but they were repulsed after having sustained considerable loss.

Such was the state of affairs when on the 2d of September 1814, there appeared an armed brig on the coast opposite the pass. She fired a gun at a vessel about to enter and forced her to run aground; she then tacked and shortly after came to an anchor at the entrance of the pass. It was not easy to understand the intentions of this vessel, who having commenced with hostilities on her first appearance, now seemed to announce an amicable disposition. Mr. Lafitte, the younger, went off in a boat to examine her, venturing so far that he could not escape from the pinnace sent from the brig and making towards the shore, bearing British colours and a flag of truce. In this pinnace were two British naval officers, captain Lockyer, commander of the brig, and an officer who interpreted for him, with captain Williams of the infantry. The first question they asked was, where was Mr. Lafitte? He, not choosing to make himself known to them, replied that the person they inquired for was on shore. They then delivered him a packet directed "To Mr. Lafitte — Barataria;" requesting him to take particular care of it, and to deliver it into Mr. Lafitte’s own hands. He prevailed on them to make for the shore, and as soon as they got near enough to be in his power, he made, himself known, recommending to them at the same time to conceal the business on which they had come. Upwards of two hundred persons lined the shore, and it was a general cry amongst the crews of the privateers at Grande Terre, that those British officers should be made prisoners and sent to New Orleans, as being spies who had come under feigned pretences to examine the coast and the passages, with intent to invade and ravage the country. It was with much difficulty that Mr. Lafitte succeeded in dissuading the multitude from this intent, and led the officers in safety to his dwelling. He thought, very prudently, that the papers contained in the packet might be of importance towards the safety of the country, and that the officers, being closely watched, could obtain no intelligence that might turn to the detriment of Louisiana. He took the earliest opportunity, after the agitation among the crews had subsided, to examine the contents of the packet; in. which he found a proclamation addressed by colonel Edward Nicholls, in the service of his Britannic Majesty and commander of the land forces on the coast of Florida, to the inhabitants of Louisiana, dated Headquarters, Pensacola, 29th August, 1814; a letter from the same, directed to Mr. Lafitte, or to the commandant at Barataria; an official letter from the honourable W. H. Percy, captain of the sloop of war Hermes, and commander of the naval forces in the gulf of Mexico, dated September 1st, 1814, directed to himself; and finally, a letter containing orders from the same captain Percy, written on the 30th of August on board the Hermes, in the road of Pensacola, to the same captain Lockyer commanding the sloop of war Sophia. (For these different papers see Appendix, No. 3.)

When Mr. Lafitte had perused these papers, captain Lockyer enlarged on the subject of them, and proposed to him to enter into the service of his Britannic majesty with all those who were under his command, or over whom he had sufficient influence; and likewise to lay at the disposal of the officers of his Britannic majesty the armed vessels he had at Barataria, to aid in the intended attack of the fort of Mobile. He insisted much on the great advantages that would thence result to himself and his crews; offered him the rank of captain in the British service, and the sum of thirty thou sand dollars, payable, at his option, in Pensacola or New Orleans, and urged him not to let slip this opportunity of acquiring fortune and consideration. On Mr. Lafitte’s requiring a few days to reflect upon these proposals, captain Lockyer observed to him that no reflection could be necessary, respecting proposalsthatobviously precluded hesitation, as he was a Frenchman, and of course now a friend to Great Britain, proscribed by the American government, exposi d to infamy, and had a brother at that very time loaded with irons in the jail of New-Orleans. He added, that in the British service he would have a fair prospect of promotion; that having such a knowledge of the country, his services would be of the greatest importance in carrying on the operations which the British government had planned against lower Louisiana; that, as soon as possession was obtained, the army would penetrate into the upper country, and act in concert with the forces in Canada; that every thing was already prepared for carrying on the war against the American government in that quarter with unusual vigour; that they were nearly sure of success, expecting to find little or no opposition from the French and Spanish population of Louisiana, whose interests, manners and customs were more congenial with theirs than with those of the Americans; that finally, the insurrection of the negroes, to whom they would offer freedom, was one of the chief means they intended to emplov, being confident of its success.

To all these splendid promises, all these ensnaring insinuations, Mr. Lafitte replied, that in a few days he would give a final answer; his object in this procrastination being to gain time to inform the officers of the state government of this nefarious project. Having occasion to go to some distance for a short time, the persons who had proposed to send the British officers prisoners to New-Orleans, went and seized them in his absence, and confined both them and the crew of the pinnae-. , in a secure place, leaving a guard at the door. The British officers sent for Mr. Lafitte; but he, fearing an insurrection of the crews of the privateers, thought it advisable not to see them, until he had first persuaded their captains and officers to desist from the measures on which they seemed bent. With this view he represented to the latter that, besides the infamy that would attach to them, if they treated as prisoners, persons who had come with a flag of truce, they would lose the opportunity of discovering the extent of the projects of the British against Louisiana, and learning the names of their agents in the country. While Mr. Lafitte was thus endeavouring to bring over his people to his sentiments, the British remained prisoners the whole night, the sloop of war continuing at anchor before the pass, waiting for the return of the officers. Early the next morning, Mr. Lafitte caused them to be released from their confinement, and saw them safe aboard their pinnace, apologizing for the disagreeable treatment they had received, and which it had not been in his power to prevent. Shortly after their departure, he wrote to captain Lockyer the letter that may be seen in the Appendix, No. 4.

His object in writing that letter was, by appearing disposed to accede to their proposal, to give time to communicate the affair to the officers of the state government, and to receive from them instructions how to act, under circumstances so critical and important for the country. He accordingly wrote on the 4th of September to Mr. Blanque, one of the representatives of the state, sending him all the papers delivered to him by the British officers, with a letter addressed to his excellency W. C. C. Claiborne, governopof the state of Louisiana. (See Appendix, No. 5.) The contents of these letters do honour to Mr. Lafitte’s judgment, and evince his sincere attachment to the American cause.

Persuaded that the country was about to be vigorously attacked, and knowing that at that time it was little prepared for resistance, he did what his duty prescribed; apprising government of the impending danger; tendering his services, should it be thought expedient to employ the assistance of his crews, and desiring instructions how to act; and in case of his offers being rejected, he declared his intention to quit the country, lest he should be charged with having cooperated with the invading enemy. On the receipt of this packet from Mr. Lafitte, Mr. Blanque immediately laid its contents before the governor, who convened the committee of defence lately formed, of which he was president; and Mr. Rancher, the bearer of Mr. Lafitte’s packet, was sent back with a verbal answer, of which it is understood that the purport was to desire him to take no steps until it should be determined what was expedient to be done; it is added, that the message contained an assurance that, in the meantime, no steps should be taken against him for his past offences against the laws of the United States.

At the expiration of the time agreed on with captain Lockver, his ship appeared again on the coast with two others, and continued standing off and on before the pass for several days.

Mr. Lafitte now wrote a second letter to Mr. Blanque, urging him to send him an answer and instructions. (See Appendix No. 6.) In the mean, time he appeared not to perceive the return of the sloop of war, who, tired of waiting to no purpose, and mistrusting Mr. Lafitte’s intentions, put out to sea and disappeared.

About this time, Mr. Lafitte received information that instead of accepting his services, and endeavouring to take advantage of the confidence the British had in him, to secure the country against an invasion, and defeat all their projects, the constituted authorities were fitting out at New-Orleans a formidable expedition against Barataria. He then retired to the German coast, where, strictly adhering to the principles he had professed, he warned the inhabitants of the danger with which they were threatened from the means intended to be employed by the enemy.

About this time, there fell into Mr. Lafitte’s hands an anonymous letter directed to a person in New-Orleans, the contents of which left no doubt as to the intentions of the British, and which is the more interesting, as all that it announced has since been fully verified. (See Appendix, No. 2.)

Such are the particulars of the first attempt made by the British against Louisiana — an attempt in which they employed such unjustifiable arts, that it may fairly be inferred that the British government scruples not to descend to the basest means, when such appear likely to contribute to the attainment of its ends. Notwithstanding the solemn professions of respect for the persons and property of the inhabitants, so emphatically made in the proclamation of colonel Nicholls, we see that one of their chief reliance for the success of operations in Louisiana, was on the insurrection of the negroes. Is it not then evident from this, that the British were bent on the destruction of a country whose rivalship they feared in their colonial productions, and that the cabinet of St. James had determined to carry on a war of plunder and devastation against Louisiana?

In coming to Barataria, to endeavour to gain over the privateers to their interests, they acted consistently with their known principles, and on a calculation of probabilities; for it was an obvious presumption that a body of men proscribed in a country whose laws they had violated, reflecting on their precarious existence, would embrace so favourable an opportunity of recovering an erect attitude in society, by ranging themselves under the banners of a powerful nation. But this calculation of the British proved fallacious; and in this instance, as in every other, they found in every individual in Louisiana, an enemy to Britain, ever ready to take up arms against her; and those very men, whose aid they so confidently expected to obtain, signally proved throughout the campaign, particularly in the service of the batteries at Jackson’s lines, that the agents of the British government had formed a very erroneous opinion of them. (See

Note No. 1,

at the end of the volume.)

The British finding themselves disappointed in their expectation of drawing over to their interests the privateersmen of Barataria, concentrated their preparations at Pensacola and Apalachicola. In this latter place, they had landed not only troops, but also twenty-two thousand stand of arms, with ammunition, blankets, aiid clothing, to be distributed among the Indians; and it was generally reported at that time, that several of their vessels had already sailed for Jamaica, to take in black troops.

General Armstrong, the then secretary of war, by a circular letter of the 4th of July, had informed the different state governments of the quota of militia they were respectively to furnish, pursuant to the president’s requisition of the same date. (See Appendix, No. 7.) On the 6th of August, the go-v vernor of the state of Louisiana published, conformably to that requisition, militia general orders, in which, after having laid before his constituents the views and intentions of the general government, to employ an adequate force to maintain with honour the contest in which our country was engaged, he exhorted the citizens of the state zealously to Stand the necessary draught for completing the thousand men demanded by the above mentioned requisition. (See Appendix, No. 8.)

All the western and southern newspapers were at that time loudly inveighing against the shameful assistance afforded by the governor of Pensacola to the British, at least inasmuch as he suffered the character of his nation to be sullied, by permitting them publicly to make hostile preparations in that town, where they had established their head-quarters, and where they were, if not the nominal, at least the virtual masters. Such repeated violations, and the succours constantly furnished to the Indians, who were evidently the allies of our enemy, contributed not a little to rouse the national spirit in that part of the union. I cannot refrain from giving here an extract from one of the papers that appeared about that time, in which the writer, after having enumerated all the grievances that the United States had to complain of against the Spanish governor of Florida, says: "who of us would not prefer to take his fortune as a common soldier, to remaining at home in affluence, while the community of which he is a member, submits tamely, silently and unresistingly to such indignities."

The commander-in-chief of the 7th district, wrote to the governor of the state, from fort Jackson, on the 15th of August, announcing to him the necessity of holding all the forces of Louisiana militia in readiness to march at the first signal, in consequence of the preparations making at Pensacola, of which he had received certain information. (See Appendix, No. 9.) Conformably to this order, the governor published in militia general orders, an extract from his letter to the commanders of the two divisions of state militia, in which he gave them instructions and regulations for their respective divisions. Commodore Patterson, commanding the station of New Orleans and its dependencies, received intelligence of the appearance of five British ships of war, which had landed a small number of men on the point at Dauphine island.

General Jackson had at this time removed his head-quarters to Mobile, from which place he wrote to the governor, on the 22d of August, a letter of which the following is an extract:

"I have no power to stipulate with any particular corps, as to particular or local service; but it is not to be presumed at present, that the troops of Louisiana will have to extend their services beyond the limits of their own state. Yet circumstances might arise, which would make it necessary they should be called to face an invading enemy beyond the boundary of the state, to stop his entry into their territory."

In consequence of this letter, the governor published, on the 5th of September, militia general orders, and afterwards general orders, directing the militia of the two divisions of the state, to hold themselves in readiness to march, the first division under major-general Villeré, being to be reviewed on the 10th of the same month, by major Hughes, assistant inspector-general of the district, in the city of New Orleans; and the second, under the command of major-general Thomas, to be reviewed at Baton Rouge on the first of October. (See Appendix, No. 10.)

By another general order, dated New Orleans, 8th September, governor Claiborne ordered the different militia companies in the city and suburbs of New Orleans, to exercise twice, and those of the other parts of the state, once a week. He also recommended to fathers of families, and men whose advanced age exempted them from active service in the field, to form themselves into corps of veterans, choose their own officers, procure arms, and to exerpjfje occasionally. The governor announces to his fellow citizens the dangers with which the country is threatened, urging to them that the preservation of their property, the repose and tranquillity of their families, call on every individual to exert all his efforts and vigilance; his order enters into minute details as to the precautions and police to be observed in the existing circumstances; it recommends the greatest diligence to be exerted in procuring arms, and the greatest care to be taken of them; and finally prescribes the conduct to be observed by all the militia officers, in case of the enemy’s penetrating into the state. (See Appendix, No. 11.)

About that time, there appeared a Spanish translation of an order of the day published at Pensacola, addressed to a detachment of the royal marines at the moment of their landing. This piece, written in a style of importance that might be used in addressing a numerous army, from which might be expected the most brilliant military achievements, breathes inveterate hatred against the Americans, loudly announcing that the object of the expedition is to avenge the Spaniards for the pretended insults offered them by the United States.

That document, replete with invectives against the American character, contains moreover a strong recommendation to sobriety; and from the earnest manner in which the author insists on that subject, one would be led to believe that the soldiers whom he addresses, stood in great need of his exhortations. This piece requires no further comment, as it speaks for itself; the tone of falsehood and duplicity that pervades it, lias induced me to publish it, especially as it may furnish some features in the portrait of our enemy. (See Appendix, No. 12.)

On the 16th of September, a meeting of a great number of the citizens of New Orleans was held at 'the Exchange Coffee-house, in that city, and by them was appointed a committee of defence to co-operate with the constituted authorities of the state, and with the general government, towards the defence of the country. The president of that committee, Mr. Edward Livingston, after an eloquent speech, in which he showed the expediency of making a solemn declaration of the patriotic sentiments which prevailed among the inhabitants of Louisiana, who had, on several occasions, been calumniated, and represented as disaffected to the American government, and disposed to transfer their allegiance to a foreign power, proposed a spirited resolution which was unanimously adopted. (See Appendix, No. 13.)

This resolution was, within a few days, followed by an address from the committee of defence to their fellow citizens. The patriotic sentiments expressed in this address, were such as need no comment, as the mere perusal of it will suffice to evince the spirit which animated the people, of whom the committee of defence were on that occasion the organ. (See Appendix, No. 14.)

FIRST ATTACK ON FORT BOWYER.

The preparations which the British had been long making at Pensacola, where, regardless of the rights of neutrality, the Spanish governor permitted the enemy of a nation with which his government was at peace, publicly to recruit, nay, even exercise his troops and the savage Indians whom he had enlisted, and whom he excited by every means of seduction, to renew the horrid scenes exhibited at fort Mims; the little care they took in their proud and frantic spirit to conceal their projects; the advantageous situation of the point of Mobile, as a military post, were among the circumstances which made it probable that fort Bowyer was the object of the expedition the British were fitting out at Pensacola.

Major Lawrence, who commanded that fort, was well aware of the means which the enemy intended to employ against him; and accordingly he made the utmost exertions to put the post confided to him, in a condition to make a vigorous resistance; while the brave garrison under his command ardently longed for an opportunity of evincing their zeal and devotedness for the honour and interest of their beloved country.

Before I enter on the glorious defence made by that garrison, it seems proper that I describe the situation of fort Bowyer, and that of Mobile point. It is indeed unnecessary to show how important the occupation of that spot must necessarily have been towards the success of military operations intended against Louisiana, as that will sufficiently appear from the bare inspection of the map. I will, therefore, merely observe that the point of the Mobile commands the passes at the entrance of the bay, and consequently the navigation of the rivers which empty into it; that on the eastern side it commands the species of archipelago which extends in a parallel direction as far as the passes Mariana and Christiana; that from its situation advancing into the gulf, it must ever afford to those who hold it, the means of exercising an almost exclusive control over the navigation of the coast of West Florida; and that its proximity to Pensacola secures to it a prompt and easy communication with that town.

This point, forming the extremity of a peninsula, joined to the continent by an isthmus four miles wide, between the river and bay of Bonsecours and the bay Perdido, extends in an east and west direction, inclining a little towards the south, for the space of twenty-nine miles in length, from the mouth of the Perdido. A large oblong lake, called Borgne, occupies the greater portion of its interior towards the east, which, independently of the narrow neck of land formed by the two bays, affords in several points the facility of cutting off all communication with the continent. The breadth of the peninsula decreases as it extends towards the west, so that three miles from the point it is only half a mile wide. This part affords another means of defence, of which the British availed themselves when they encamped on the peninsula during their last attack; I mean a ditch or coulée,

communicating with a lagoon, the whole occupying upwards of half the breadth of the peninsula. Some briars and stunted fir trees and live oaks grow here and there on a soil almost entirely formed of sand and shells, which mixture gives it a very firm consistency. Within two miles of the point vegetation ceases almost entirely, and the soil becomes a succession of downs, ditches, ravines, and hillocks of sand, arid and moving in some places, and in others as hard as beaten ground. These ditches are from four to eight feet deep, forming several sinuosities, where one sees here and there a few tufts of grass. It is nearly at the extremity of this tongue of land, on the point rounding towards the northeast, that fort Bowyer is situated. The part that is nearest the shore is the angle of the north curtain and the semicircular battery facing the pass, and opening a little at the distance of fifty yards, contiguous to a bluff which skirts the peninsula on both sides, nearly in its whole length.

Fort Bowyer is a redoubt formed on the seaside, by a semi-circular battery of four hundred feet in development, flanked with two curtains sixty feet in length, and joined to a bastion whose capital line passes through the centre of the circular battery. This bastion has but thirty-five feet in its gorge, with two flanks, each capable of receiving but one piece of artillery, and fifty feet in length on its front and rear aspects.

Its interior dimensions are one hundred and eighty feet in length from the summit of the bastion to the parapet of the circular battery, and two hundred feet for the length of tlie cord of the arc described by the battery. The receding angles formed by the curtains with the flanks of the bastion and those of the battery, considerably diminish the dimensions of this fort, the superficies of which may be estimated at twenty-two thousand feet.

The circular parts and the flanks which join it to the curtains, have a parapet fifteen feet thick at the summit, and in all the rest of the perimeter of the fort, the parapet does not exceed the thickness of three feet above the platforms; a fosse twenty feet wide surrounds the fort, and a very insufficient glacis without a covered way completes the fortification. The interior front of the parapet is formed of pine, a resinous wood which a single shell would be sufficient to set on fire. The fort is destitute of casemates (the only shelter from bombs) even for the sick, the ammunition or provisions. To these inconveniencies may be added the bad situation of the fort, commanded by several mounds of sand, as above described, at the distance of from two to three hundred yards. On the summit of those mounds it would be very easy to mount pieces of artillery, whose slanting fire would command the inside of the fort.

From the first information of the preparations making by the British at Pensacola, until the 12th of September, on which day four large vessels were discovered in the offing, the garrison of the fort had been constantly employed in putting the fortifications in a condition to resist the enemy. Major Lawrence now ordered all the men of the garrison to enter within the fort, and to keep themselves in readiness for action. From that moment the garrison passed each night under arms, every man at his post.

Before I enter on the particulars of the events posterior to the 12th, it may be proper to give a statement of the strength of the garrison, and of the means of defence.

The garrison consisted of one hundred and thirty men including officers, and the whole artillery of the fort was twenty pieces of cannon, distributed in the following manner: two twenty-fours, six twelves, eight nines, and four fours; the twenty-fours and twelves being alone mounted on coast carriages, and all the others on Spanish carriages little fit for service. One nine-pounder and three fours were mounted on the bastion, all the rest on the circular battery and its flanks. Those guns in the rear bastion and on the flanks, were on temporary platforms, and the men exposed from their knees upwards.

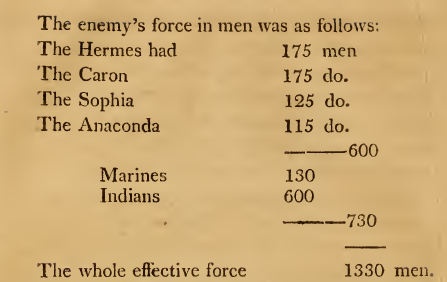

On the 12th of September, the sentinel stationed towards lake Borgne, reported that on the morning of that day the enemy had landed six hundred Indians or Spaniards, and one hundred and thirty marines, and on the evening of the same day, two English sloops of war, with two brigs, came to anchor on the coast, within six miles east of the fort.

On the 13th, the enemy sent reconnoitring parties towards the back of the fort, who approached to within three quarters of a mile of it. At half after twelve, the enemy approached within the distance of seven hundred yards, whence they threw against the fort three shells and one cannon ball. The shells did no injury, having exploded in the air; but the ball, which was a twelve pound shot, struck a piece of timber that crowned the rampart of the curtain, part of which it carried away and then rebounded. The fort returned a few shots in the direction of the smoke of the enemy’s guns, they being covered by the mounds of sand.

Meanwhile, the enemy, under cover of those mounds, retired a mile and a half behind the fort, and appeared to be employed in raising intrenchments. Three discharges of cannon were once more sufficient to disperse them. In the afternoon, several light boats having attempted to sound the channel nearest the point, were forced, by the balls and grape-shot fired against them, to return to their ships.

On the 14th, at six in the morning, the enemy still continued at the same distance, apparently employed in some works of fortification; the ships likewise remained at the same anchorage.

On the 15th of September, a day ever memorable for the garrison of fort Bowyer, the enemy by his movements gave early indications of his intention to attack; for by break of day, a very active communication was perceived between the ships and the troops on shore.

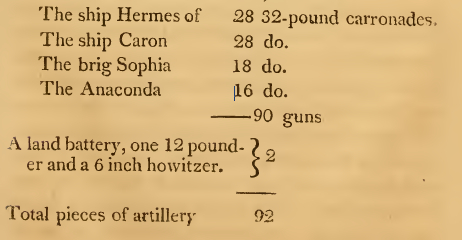

Towards noon, the wind having slackened to a light breeze from the southeast, the ships weighed anchor and stood out to sea: at two o’clock they tacked and bore down against the fort before the wind in line of battle, in the channel, the foremost ship being the Hermes, on board of which was the commodore, captain Percy.

Major Lawrence seeing the enemy determined on making a regular attack, called a council of all his officers. They unanimously agreed to make the most obstinate resistance, vigorously exerting every means of defence, and came to the following resolution:

"That in case of being, by imperious necessity, compelled to surrender (which could only happen in the last extremity, on the ramparts being entirely battered down, and the garrison almost wholly destroyed, so that any further resistance would be evidently useless,) no capitulation should be agreed on, unless it had for its fundamental article that the officers and privates should retain their arms and their private property, and that on no pretext should the Indians be suffered to commit any outrage on their persons or property; and unless full assurance were given them that they would be treated as prisoners of war, according to the custom established among civilized nations."

A11 the officers of the garrison unanimously swore, in no case, nor on any pretext, to recede from the above conditions; and they pledged themselves to each other, that in case of the death of any of them, the survivors would still consider themselves bound to adhere to what had been resolved on.

By 4 o’clock in the afternoon, the commodore’s ship being within the reach of our great guns, a fire was opened on her from two twenty-four-pounders, but with little effect. The ship then fired one of her fore guns, but her shot did not reach the fort. As the ships appeared, all the guns that could be brought to bear opened on them a brisk fire.

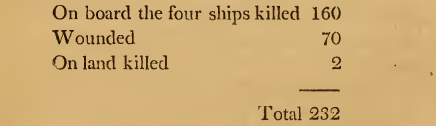

At half past four, the Hermes came to anchor under our battery, within musket shot of the fort; and the other three took their station behind that ship, forming a line of battle in the channel. The engagement now became general, and the circular, battery kept up a dreadful fire against the most advanced ships, whilst, on the other hand, the four ships discharged against the fort whole broadsides, besides frequent single shots. Meanwhile captain Woodbine, the person who had enlit ed and trained the Indians in Pensacola, opened the fire of a battery that he had established behind the bluff on the southeast shore, at the distance of seven hundred yards from the fort. That battery had one twelve-pounder and a six-inch howitzer, firing balls and shells: these the south battery of the fort soon silenced. It was now that the fire on both sides raged with the greatest fury; the fort and the ships being enveloped in a blaze of fire and smoke, until half past five, when the haliards of the commodore’s flag were carried away by a ball, and the flag fell.

On this major Lawrence, with his characteristic humanity, instantly caused the firing to cease, with a view to ascertain the real intention of the enemy, who discontinued firing for five minutes; at the expiration of which, the brig next to the Hermes, discharged a whole broadside against the fort, and at the same time the commodore hoisted a new flag. All the guns of the battery being at that moment loaded, they were all fired at once, and produced such a commotion that it shook the ground. A few moments of silence succeeded. The enemy began to perceive the effect his conduct had on the minds of the garrison, who indignant at the manner in which the British made war, resolved, from the moment of the flag’s being replaced, to bury themselves under the ruins of the fort, rather than surrender. The fire being renewed, continued for some time on both sides with the same violence. The Hermes having had her cable cut, was carried away by the current, and presented her head to the fort, and in that position she remained from fifteen to twenty minutes, whilst the raking fire of the fort swept fore and aft almost every thing on deck. At the moment when the fire was most intense, the flagstaff was carried away. This the British plainly perceived; but instead of following the example of major Lawrence, in suspending their fire, they redoubled it, and each of the ships discharged her whole broadside against the fort.

Major Lawrence immediately hoisted another flag on the edge of the parapet, having fastened it to a sponge-staff.