C. C. Leigh.

“Slave Children.”

“White and Colored Slaves.”

SLAVE CHILDREN.

WHEN the war began two things were inevitable: first, that the loathsome secret history of the slave system in this Country would be exposed; and, second, that the appalled and indignant common sense of the people would see that no honorable peace was possible except upon condition of the annihilation of the system. Indeed all that the friends of liberty and human rights in this country ever asked is the freedom of speech. In the days when the Abolitionists were hunted as wild beasts they said calmly that if they were only allowed to speak and tell the truth their victory was sure. And because through fires of hate and rage they persisted in speaking they are the saviours of American liberty. The slave-drivers and their political allies at the North knew equally well that if the constitutional right of discussion were allowed the horrors of the system would be known, and the outraged decency and humanity of the American people would sweep away the iniquity in a flood of wrath. So at the South these gentry hung, and burned, and tarred and feathered, and mobbed every citizen who chose to speak or was suspected of wishing to speak; while at the North the panders of slavery denounced the discussion of the subject, incited mobs against the speakers, and driveled through all their papers and speeches, smooth and dreary slop about the Christianity, and fraternity, and simplicity of “the institution,” until people who were prevented by these same efforts from hearing the facts of the case really believed that a society planted upon slavery was a kind of scriptural idyl and patriarchal Arcadia.

The moment these gentry saw political power pass from their hands they knew that the terrible truth would be told, and annihilate their “institution,” and therefore they made their grand and desperate movement to destroy the Government and plunge us all into common ruin. And they are right so far as they anticipated the consequences of a popular knowledge of slavery. The war has brought the people of this country face to face with this unspeakable infamy of slavery. The working-men of the Free States, now soldiers in the field, no longer owe their knowledge of it to what Governor Seymour, or Mr. S. F. B. Morse, or Judge Woodward, or Bishop Hopkins, or any newspaper chooses to say of it to advance a political party; they see the thing itself as Mrs. Kemble describes it, as Mr. Olmsted describes it, as Thomas Jefferson describes it, as John Randolph describes it; they see it, indeed, as no human pen can describe it, exactly as General Butler, so long its apologist through ignorance and party-spirit, found it in New Orleans, and as it is in every State, in every city, on every plantation, a double-handed curse, smiting both slave and master.

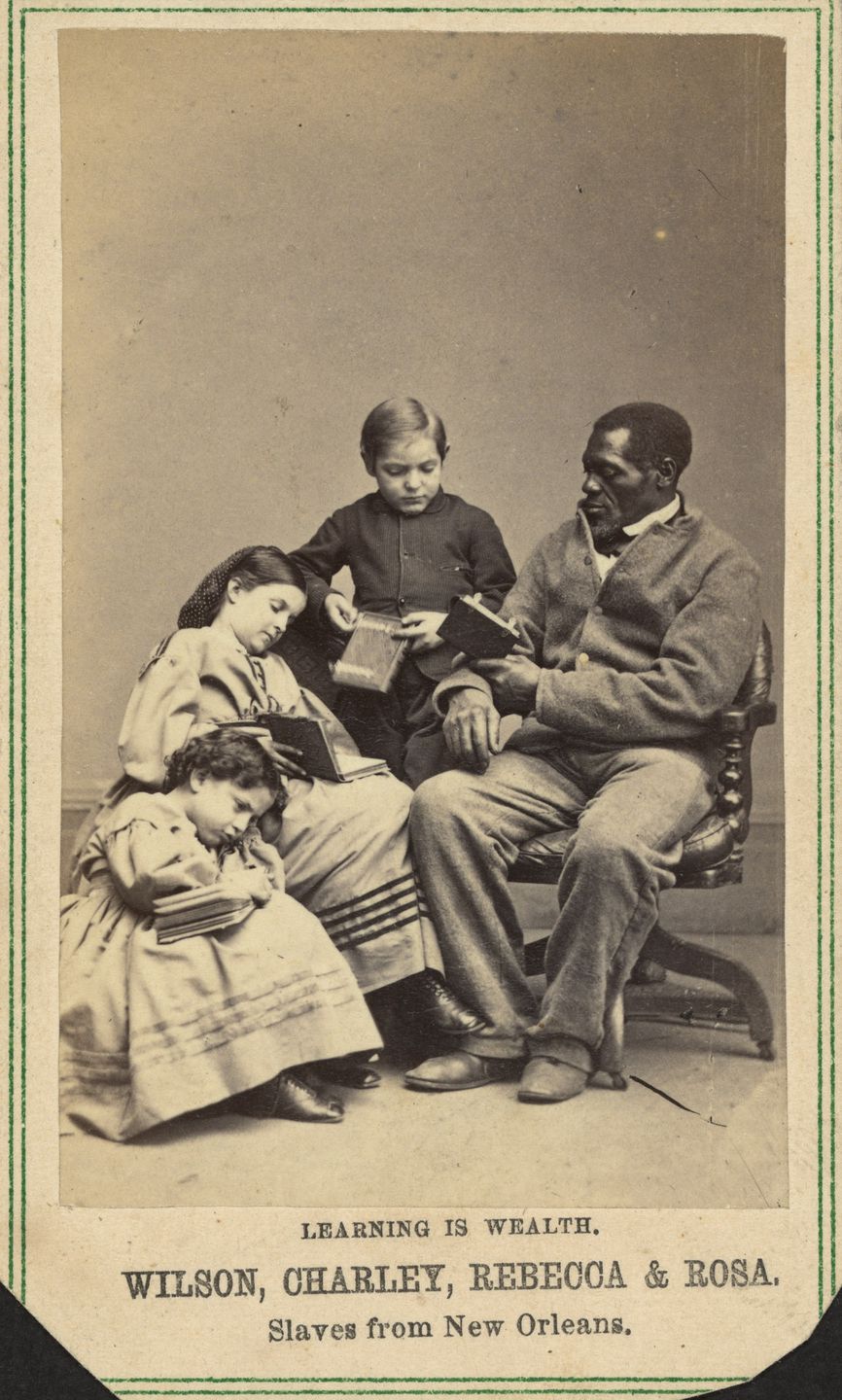

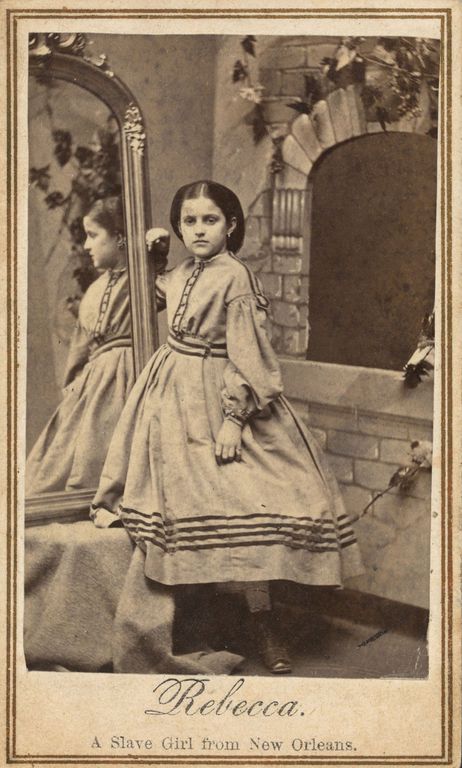

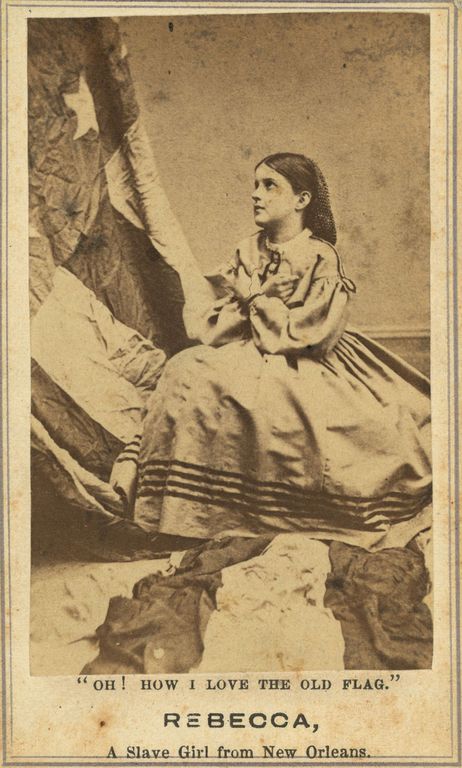

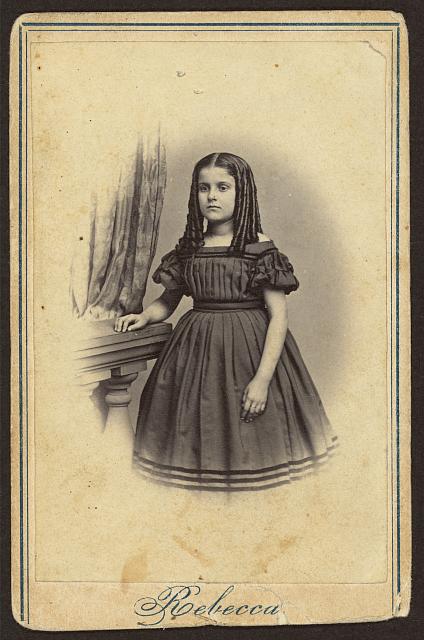

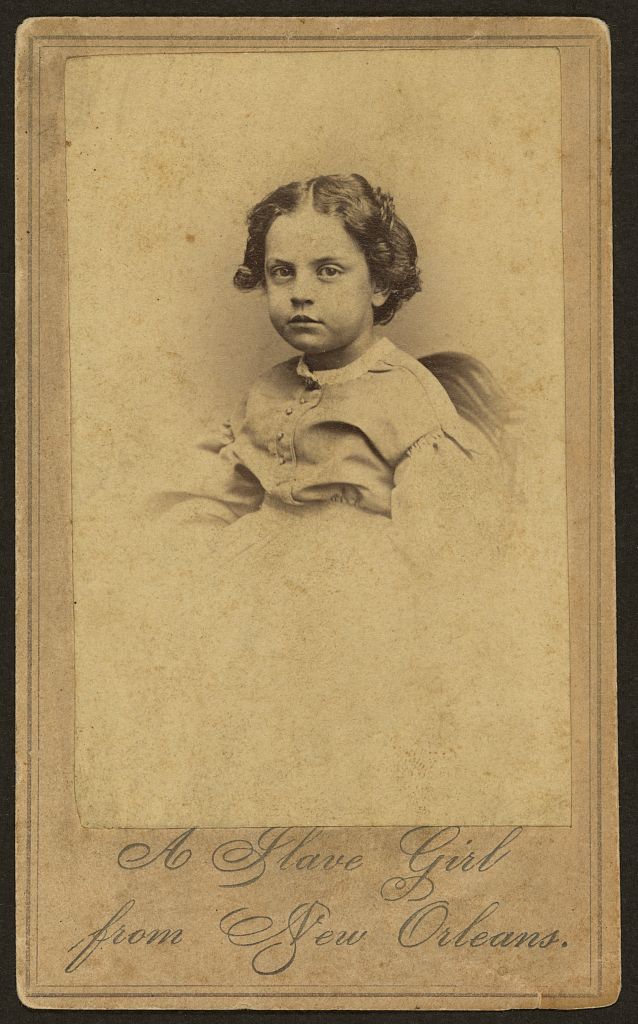

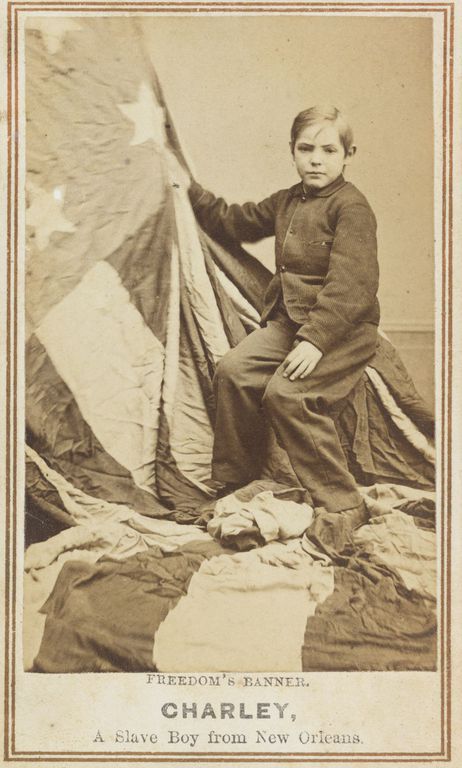

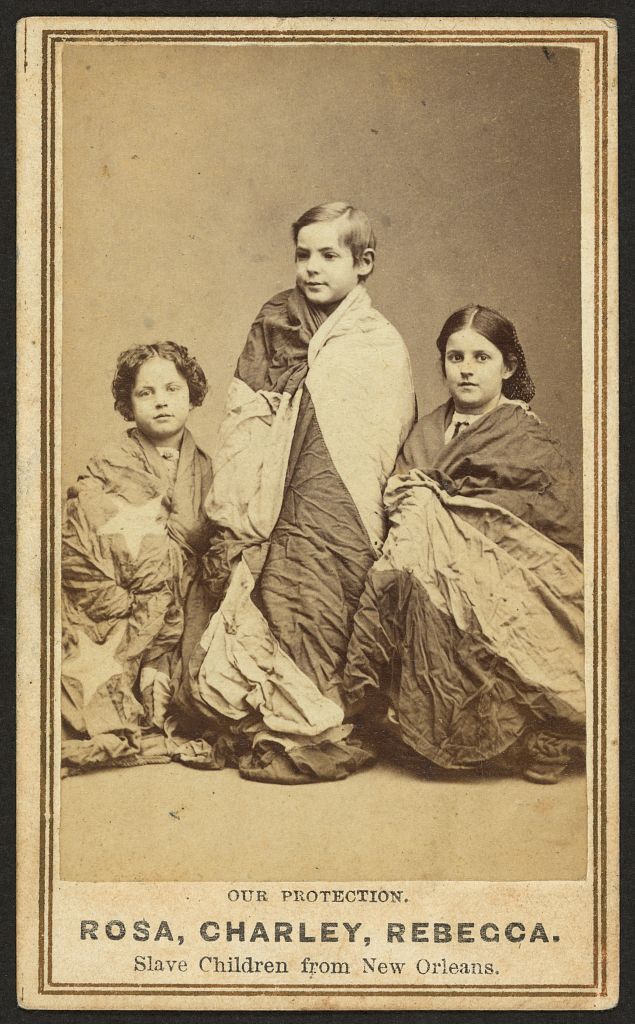

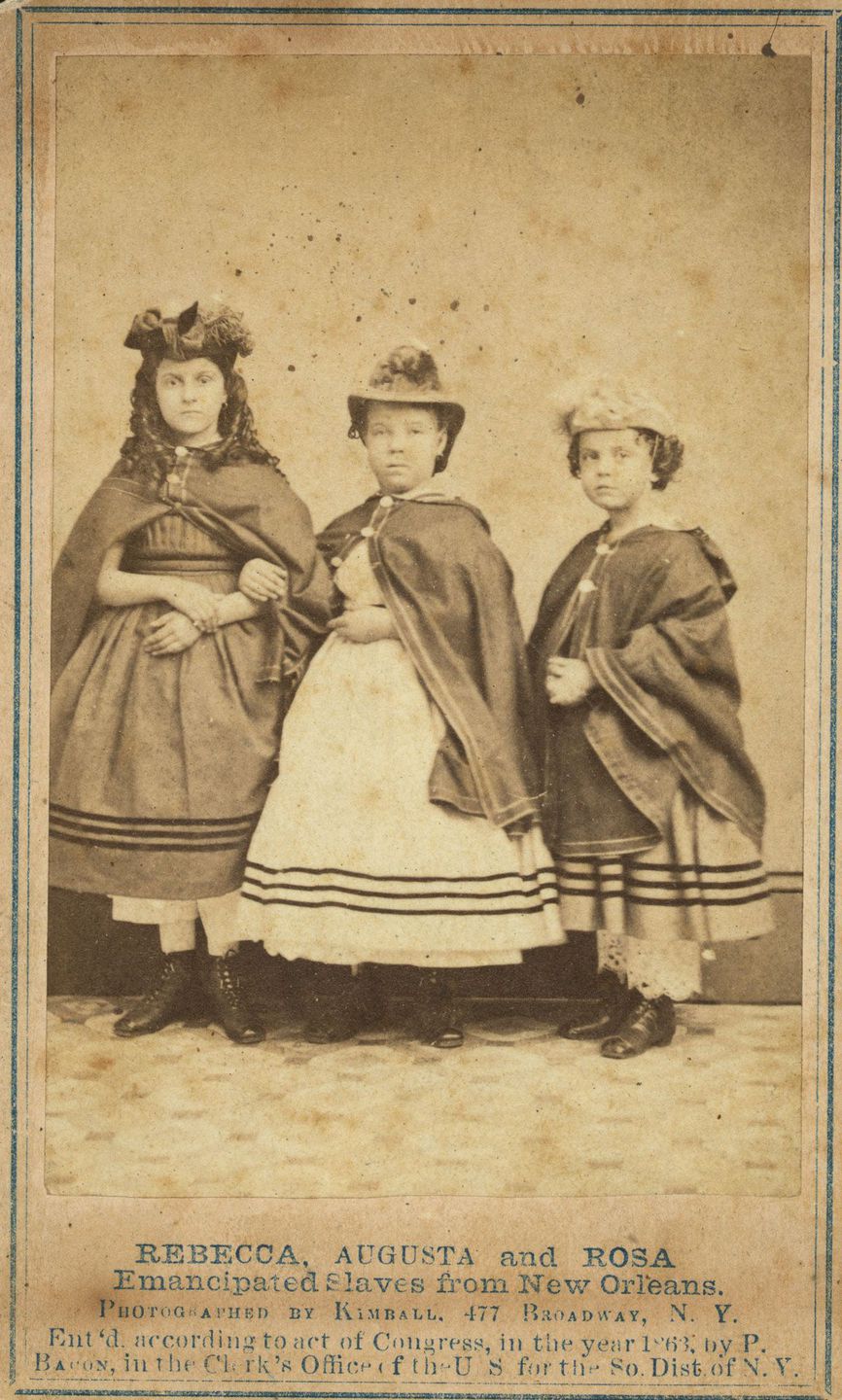

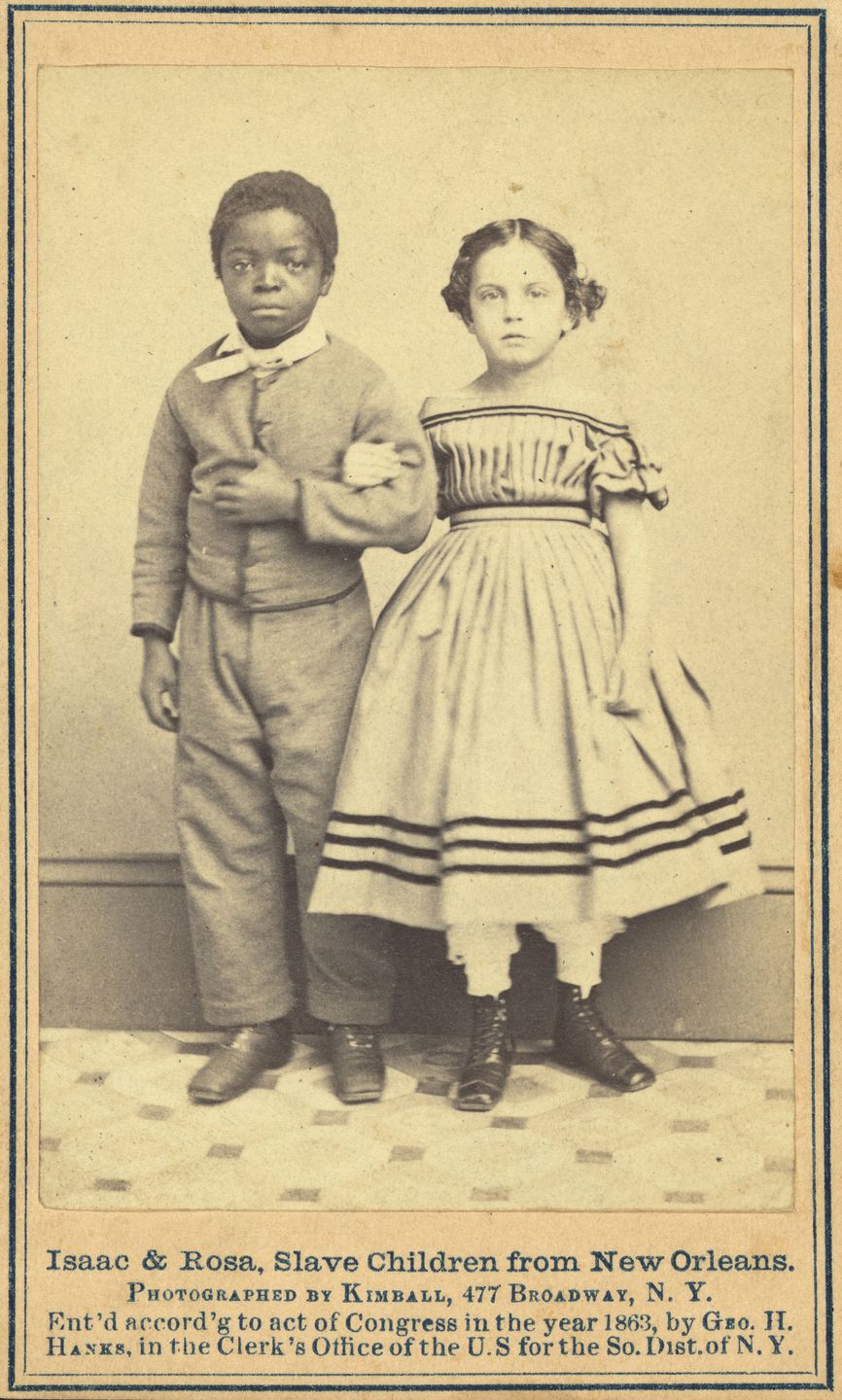

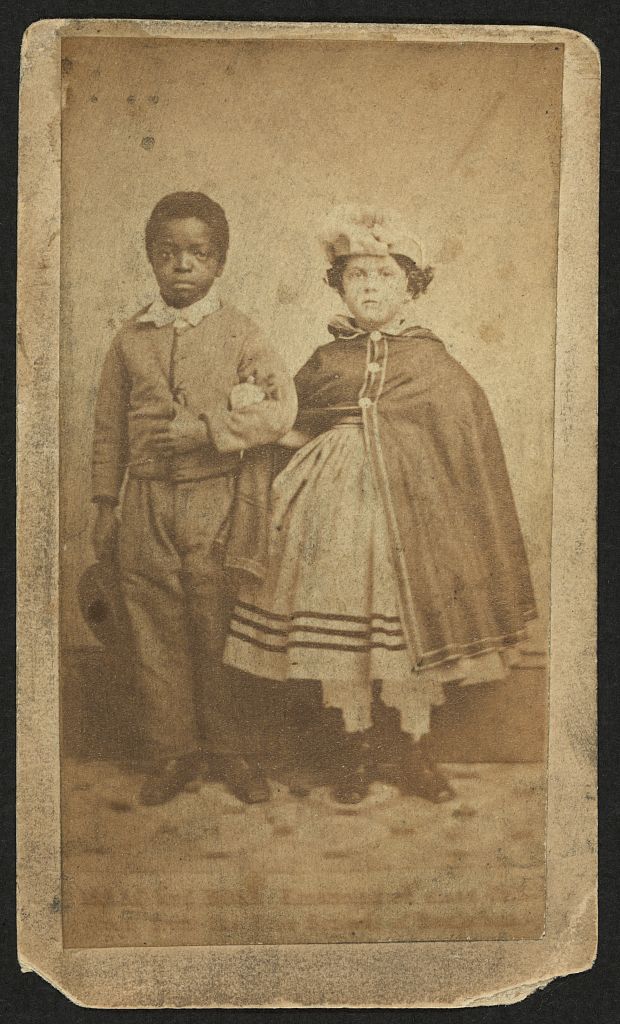

A terrible illustration of this truth of the outrage of all natural human affections we present to-day in the engravings, from photographs, of slave children upon page 69 of this paper. These are, of course, the offspring of white fathers through two or three generations. They are as white, as intelligent, as docile, as most of our own children. Yet the “chivalry,” the “gentlemen” of the Slave States, by the awful logic of the system, doom them all to the fate of swine; and, so far as they can, the parents and brothers of these little ones destroy the light of humanity in their souls, Then, lest the “chivalry” that sells its children, and the “gentlemen” who seduce the most friendless and defenseless of women, should withdraw their custom, the St. Lawrence Hotel, in Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, turns the children — flying not for life only, but the girls for their honor, and the boys for their manhood — into the street; upon which they were received and kindly welcomed at the Continental. At a time when, to perpetuate the system which defies the law of God and the instinct of man, the slaveholders are destroying loyal men, noble sons of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania with the rest, the St. Lawrence Hotel strives to propitiate those at the South who do this iniquity, and those at the North who support them in it, by refusing to receive the children whose portraits we give. So every where humanity falls at the touch of this “institution.” And so, by God’s blessing, the humanity and wisdom of the American People is at this moment touching Slavery to its destruction. Little children like these in the picture this country no longer turns away into untold horrors and despair; but its heart whispers to them, gently, “Suffer little children to come unto me!”

WHITE AND COLORED SLAVES.

To the Editor of Harper’s Weekly:

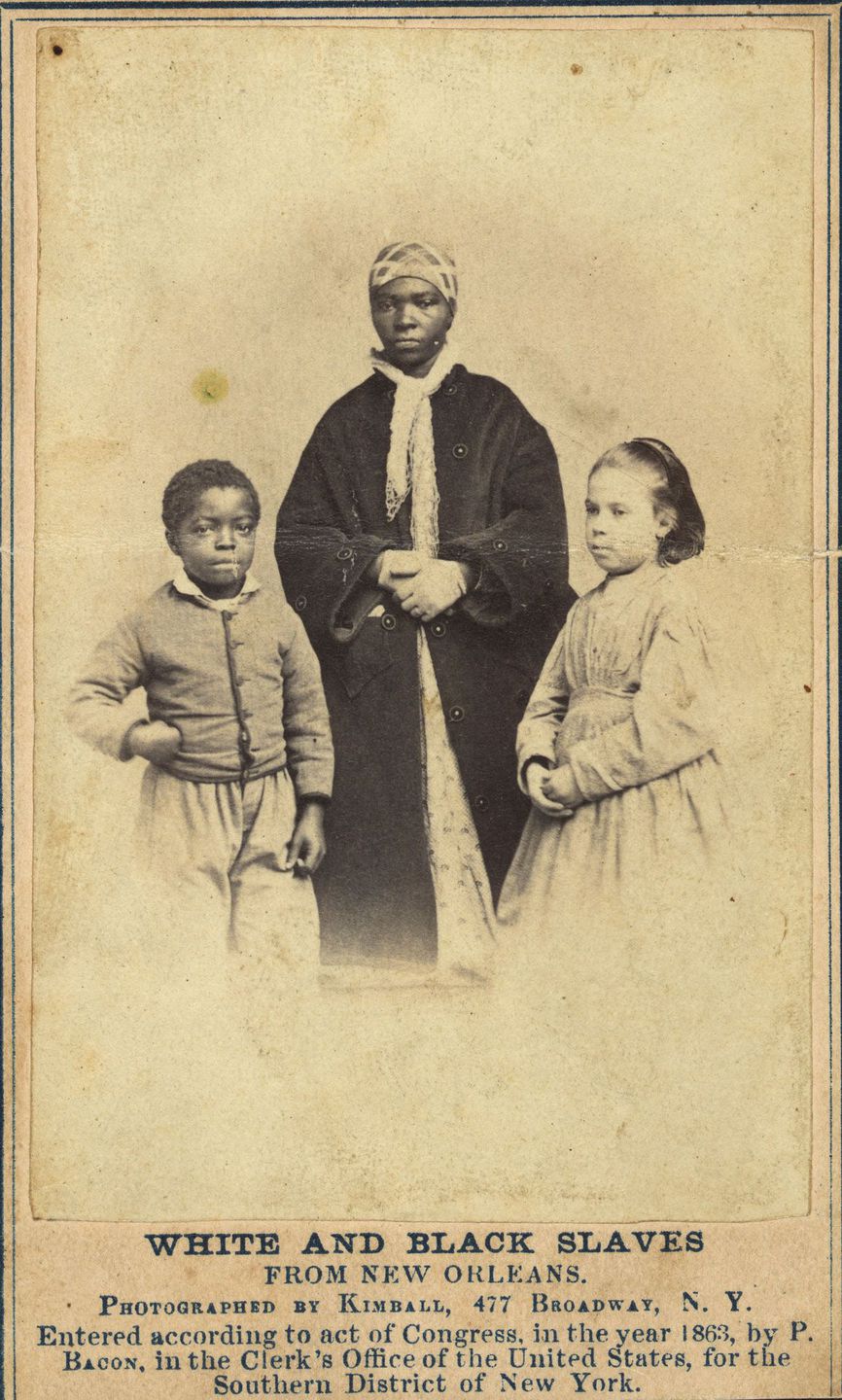

THE group of emancipated slaves whose portraits I send you were brought by Colonel Hanks and Mr. Philip Bacon from New Orleans, where they were set free by General Butler. Mr. Bacon went to New Orleans with our army, and was for eighteen months employed as Assistant Superintendent of Freedmen, under the care of Colonel Hanks. He established the first school In Louisiana for emancipated slaves, and these children were among his pupils. He will soon return to Louisiana to resume his labor.

Rebecca Huger is eleven years old, and was a slave in her father’s house, the special attendant of a girl a little older than herself. To all appearance she is perfectly white. Her complexion, hair, and features show not the slightest trace of negro blood. In the few months during which she has been at school she has learned to read well, and writes as neatly as most children of her age. Her mother and grandmother live in New Orleans, where they support themselves comfortably by their own labor. The grandmother, an intelligent mulatto, told Mr. Bacon that she had “raised” a large family of children, but these are all that are left to her.

Rosina Downs is not quite seven years old. She is a fair child, with blonde complexion and silky hair. Her father is in the rebel army. She has one sister as white as herself, and three brothers who are darker. Her mother, a bright mulatto, lives in New Orleans in a poor hut, and has hard work to support her family.

Charles Taylor is eight years old. His complexion is very fair, his hair light and silky. Three out of five boys in any school in New York are darker than he. Yet this white boy, with his mother, as he declares, has been twice sold as a slave. First by his father and “owner,” Alexander Wethers, of Lewis County, Virginia, to a slave-trader named Harrison, who sold them to Mr. Thornhill of New Orleans. This man fled at the approach of our army, and his slaves were liberated by General Butler. The boy is decidedly intelligent, and though he has been at school less than a year he reads and writes very well. His mother is a mulatto; she had one daughter sold into Texas before she herself left Virginia, and one son who, she supposes, is with his father in Virginia.

These three children, to all appearance of unmixed white race, came to Philadelphia last December, and were taken by their protector, Mr. Bacon, to the St. Lawrence Hotel on Chestnut Street. Within a few hours, Mr. Bacon informed me, he was notified by the landlord that they must leave. The children, he said, had been slaves, and must therefore be colored persons, and he kept a hotel for white people. From this hospitable establishment the children were taken to the “Continental,” where they were received without hesitation.

Wilson Chinn is about 60 years old, he was “raised” by Isaac Howard of Woodford County, Kentucky. When 21 years old he was taken down the river and sold to Volsey B. Marmillion, a sugar planter about 45 miles above New Orleans. This man was accustomed to brand his negroes, and Wilson has on his forehead the letters “V. B. M.” Of the 210 slaves on this plantation 105 left at one time and came into the Union camp. Thirty of them had been branded like cattle with a hot iron, four of them on the forehead, and the others on the breast or arm.

Augusta Broujey is nine years old. Her mother, who is almost white, was owned by her half-brother, named Solamon, who still retains two of her children.

Mary Johnson was cook in her master’s family in New Orleans. On her left arm are scars of three cuts given to her by her mistress with a rawhide. On her back are scars of more than fifty cuts given by her master. The occasion was that one morning she was half an hour behind time in bringing up his five o’clock cup of coffee. As the Union army approached she ran away from her master, and has since been employed by Colonel Hanks as cook.

Isaac White is a black boy of eight years; but none the less intelligent than his whiter companions. He has been in school about seven mouths, and I venture to say that not one boy in fifty would have made as much improvement in that space of time.

Robert Whitehead. — the Reverend Mr. Whitehead perhaps we ought to style him, since he is a regularly ordained preacher — was born in Baltimore. He was taken to Norfolk, Virginia, by a Dr. A. F. N. Cook, and sold for $1525; from Norfolk he was taken to New Orleans, where he was bought for $1175 by a Dr. Leslie, who hired him out as house and ship painter. When he had earned and paid over that sum to his master, he suggested that a small present for himself would be quite appropriate. Dr. Leslie thought the request reasonable, and made him a donation of a whole quarter of a dollar. The reverend gentleman can read and write well, and is a very stirring speaker. Just now he belongs to the church militant, having enlisted in the United States army.

A large photograph of the whole group which you reproduce has been taken, and cartes de visite of the separate figures. They are for sale at the rooms of the National Freedman’s Relief Association, No. 1 Mercer Street, New York, or I will send them by mail on receipt of the price: $1 for the large picture, 25 cents each for the small ones. The profits to go to the support of the schools in Louisiana.

C. C. Leigh.

Text prepared by:

- L’Niya Burrell

- Kanishea Chambers

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Leigh, C. C. “Slave Children,” and “White and Colored Slaves.” Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization 30 Jan. 1864: 66+. Internet Archive. 4 Apr. 2012. Web. 15 Aug. 2021. <https:// archive.org/ details/ harpers weekly v8bonn>.