General Leonidas Polk.

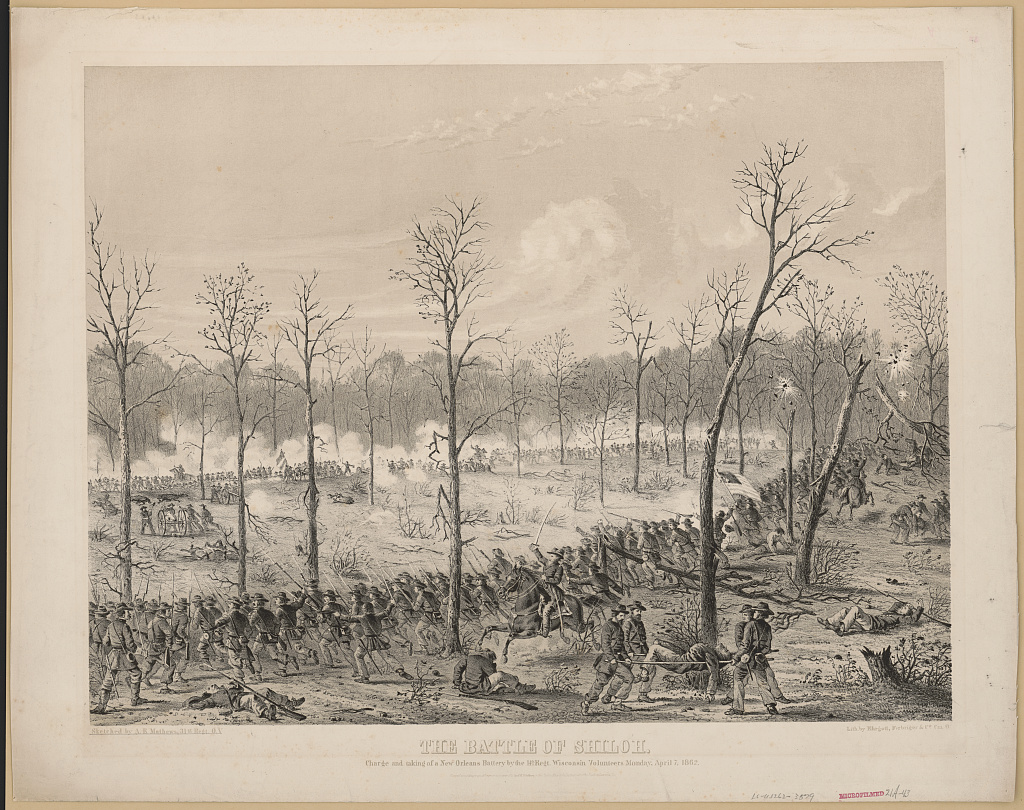

“The Battle of Shiloh.”

No. 140.

Report of Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk, C. S. Army, Commanding First Corps.

Hdqrs. Polk’s Corps, Army of the Tennessee,

February 4, 1863.

Sir: In reply to your note I have the honor to send you herewith my official report of the operatins of the First Corps of the Army of the Mississippi, commanded by me at the battle of Shiloh. It has been delayed Much beyond the time when it should have been forwarded; but the pressing nature of my engagements since that battle has been such as to make it impracticable to complete and forward it sooner.

I am, respectfully, your obediant servant,

L. Polk,

Lieutenant-General, Commanding.

General S. Cooper,

Adjutant and Inspector-General C. S. Army, Richmond, Va.

Hdqrs. Right Wing, Army of the Mississippi,

September —, 1862.

I beg leave to submit the following report of the part taken by the troops comprising my corps in the battle of Shiloh:

It was resolved by our commander-in-chief (General Johnston) to attack the enemy in his position on the Tennessee River, if possible, at daybreak on April 5.

My corps consisted of two divisions, of two brigades each, commanded, respectively, by Major-General Cheatham and Brigadier-General Clark, and, with the exception of three regiments — one from Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas, respectively — was composed of Tennesseeans.

Major-General Cheatham’s division was on outpost duty at and near Bethel, on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad, and was ordered to proceed to a point near Pittsburg Landing, on the river, for the purpose of joining in the contemplated attack.

On April 3 I was directed to march so much of my corps as was still at Corinth toward the same point. The route to be taken was that pursued by the corps of General Hardee over the Ridge and Bark roads, and I was ordered to march so as to allow an interval of half an hour between the two corps.

This order I was directed to observe until I reached Mickey’s. On reaching Mickey’s my instructions were to halt, to allow the corps of General Bragg — whose route fell into ours at that point — to fall in and follow in the immediate rear of General Hardee. The plan of battle was that the corps of General Hardee should form the front line, that of General Bragg the second, my corps and that of General Breckinridge to constitute the third or reserve.

I maintained the interval ordered between General Hardee’s and my corps during the night of the 3d and during the following day, and halted the head of my column at the cross-roads at Mickey’s about dark on the 4th, according to instructions, my column being well up.

At Mickey’s we were about 21⁄2 miles from the place at which our line of battle was to be formed, and here the head of General Bragg’s corps also bivouacked on the same night.

At 3 o’clock on the following morning (Saturday, the 5th) the whole of my command was under arms in waiting on the road, which it could not take, as it was occupied by the troops of General Bragg, which were filing into the rear of those of General Hardee.

It was now manifest that the attack at daybreak could not be made; that the troops could not reach their position in time, and that the failure was owing to the condition of the roads, which were exceedingly bad in consequence of the heavy rains which had fallen.

I took a position early in the morning near the forks of the road, to wait for the troops of General Bragg to pass. While there in waiting, at 10 a.m. Generals A. S. Johnston and Beauregard, with their staffs, rode up from the rear, and, halting opposite me, gave me orders to move promptly in rear of General Bragg, so that I might give the road to General Breckinridge, who was to follow me, coming in from General Bragg’s route. I was also ordered to halt my column 11⁄2 miles in rear of the place at which General Bragg’s line of battle crossed the road, and to deploy my corps to the left on a line parallel to that of General Bragg, General Breckinridge having been ordered to halt at the same point and deploy his corps to the right, with his left resting on my right.

It was near 2 o’clock before the whole of General Bragg’s corps had passed. I then put my column in motion and rode to the front. Proceeding half a mile, I sent Lieutenant Richmond, my aide-de-camp, forward to ascertain the point at which General Bragg’s line would cross the road and to measure back for the place at which I was to halt and deploy. This he did, and on reaching the place Lieutenant Richmond informed me that the road I was pursuing ran into that across which General Bragg was forming at an obtuse angle. It became necessary then, before I could form, to ascertain the general direction of the line in front of me. To effect this I sent forward my inspector-general (Blake), and leaving a staff officer to halt my column at the proper place, I proceeded myself to aid in the reconnaissance. I had not advanced far before I came upon General Ruggles, who commanded General Bragg’s left, deploying his troops. Having ascertained the direction of the line, I did not wait for him to complete it, but returned to the head of my column to give the necessary orders.

By this time it was near 4 o’clock, and on arriving I was informed that General Beauregard desired to see me immediately. I rode forward to his headquarters at once, where I found General Bragg and himself in conversation. He said, with some feeling, “I am very much disappointed at the delay which has occurred in getting the troops into position.” I replied, “So am I, sir; but so far as I am concerned my orders are to form on another line, and that line must first be established before I can form upon it.” I continued, “I reached Mickey’s at night-fall yesterday, from whence I could not move, because of the troops which were before me, until 2 p.m. to-day. I then promptly followed the column in front of me, and have been in position to form upon it so soon as its line was established.” He said he regretted the delay exceedingly, as it would make it necessary to forego the attack altogether; that our success depended upon our surprising the enemy; that this was now impossible, and we must fall back to Corinth.

Here General Johnston came up and asked what was the matter. General Beauregard repeated what he had said to me. General Johnston remarked that this would never do, and proceeded to assign reasons for that opinion. He then asked what I thought of it. I replied that my troops were in as good condition as they had ever been; that they were eager for the battle; that to retire now would operate injuriously upon them, and I thought we ought to attack.

General Breckinridge, whose troops were in the rear and by this time had arrived upon the ground, here joined us, and after some discussion it was decided to postpone further movement until the following day, and to make the attack at daybreak. I then proceeded to dispose of my divisions — Cheatham having arrived — according to an alteration in the programme, and we bivouacked for the night.

At the appointed hour on the morning of the 6th my troops were moved forward, and so soon as they were freed from an obstruction, formed by a thicket of underbrush, they were formed in column of brigades, and pressed onward to the support of the second line.

General Clark’s division was in front. We had not proceeded far before the first line, under General Hardee, was under fire throughout its length, and the second, under General Bragg, was also engaged.

The first order received by me was from General Johnston, who had ridden to the front to watch the opening operations, and who, as commander-in-chief, seemed deeply impressed with the responsibilities of his position. It was observed that he entered upon his work with the ardor and energy of the true soldier, and the vigor with which he pressed forward his troops gave assurance that his persistent determination would close the day with a glorious victory.

The order was to send him a brigade to the right for the support of General Bragg’s line, then hotly engaged. The brigade of General Stewart, of General Clark’s division, was immediately dispatched to him, and was led by him in person to the point requiring support.

I was then ordered by General Beauregard to send one of the brigades of my rear division to the support of General Bragg’s left, which was pressed by the enemy. Orders were given to that effect to General Cheatham, who took charge of the brigade in person and executed the movement promptly. My two remaining brigades were held in hand until I received orders to move them directly to the front, to the support of General Bragg’s center. These were Colonel Russell’s, of General Clark’s division, which was directed by that officer, and General Bushrod R. Johnson’s, of General Cheatham’s division. They moved forward at once, and were both very soon warmly engaged with the enemy. The resistance at this point was as stubborn as at any other on the field.

The forces of the enemy to which we were opposed were understood to be those of General Sherman, supported by the command of General McClernand, and fought with determined courage and contested every inch of ground.

Here it was that the gallant Blythe, colonel of the Mississippi regiment bearing his own name, fell under my eye, pierced through the heart, while charging a battery. It was here that Brigadier-General Johnson, while leading his brigade, fell also, it was feared, mortally wounded; and General Clark, too, while cheering his command amid a shower of shot and shell, was struck down and so severely wounded in the shoulder as to disable him from further service, and compel him to turn over a command he had taken into the fight with such distinguished gallantry; and here also fell many officers of lesser grade, among them the gallant Capt. Marshall T. Polk, of Polk’s battery (who lost a leg), as well as a large number of privates, who sealed their devotion to our cause with their blood.

We, nevertheless, drove the enemy before us, dislodged him from his strong positions, and captured two of his batteries; one of them was taken by the Thirteenth Regiment Tennessee Volunteers, commanded by Colonel Vaughan, the other by the One hundred and fifty-fourth Senior Regiment Tennessee Volunteers, commanded by Col. Preston Smith-the former of Colonel Russell’s and the latter of General Johnson’s brigade.

After these successes the enemy retired in the direction of the river, and while they were being pressed I sought out General Bragg, to whose support I had been ordered, and asked him where he would have my command. He replied, “If you will take care of the center, I will go to the right.” It was understood that General Hardee was attending to the left. I accepted the arrangement, and took charge of the operations in that part of the general line for the rest of the day. It was fought by three of my brigades only — General Stewart’s, General Johnson’s (afterwards Col. Preston Smith’s), and Colonel Russell’s. My fourth brigade, that of Colonel Maney, under the command of General Cheatham, was on the right, with Generals Bragg and Breckinridge. These three brigades, with occasionally a regiment of some other corps which became detached, were fully employed in the field assigned me. They fought over the same ground three times, as the fortunes of the day varied, always with steadiness (a single instance only excepted, and that only for a moment), and with occasional instances of brilliant courage. Such was the case of the Thirty-third Regiment Tennessee Volunteers, under Col. A. W. Campbell, and the Fifth Tennessee, under Lieut. Col. C. D. Venable, both for the moment under command of Colonel Campbell.

Shortly after they were first brought forward as a supporting force they found themselves ordered to support two regiments of the line before them, which were lying down and engaging the enemy irregularly. On advancing they drew the enemy’s fire over the heads of the regiments in their front. It was of so fierce a character that they must either advance or fall back. Campbell called to the regiments before him to charge. This they declined to do. He then gave orders to his own regiments to charge, and led them in gallant style over the heads of the regiments lying in advance of him, sweeping the enemy before him and putting them completely to rout.

In this charge Colonel Campbell was severely wounded, but still retained his command.

Such, also, was the charge made by the Fourth Tennessee, Lieutenant-Colonel Strahl. This was against a battery of heavy guns, which was making sad havoc in our ranks, and was well supported by a large infantry force.

In reply to an inquiry by their cool and determined brigade commander, General Stewart, “Can you take that battery," their colonel said, “We will try,” and at the order forward they moved at a double-quick to within 30 paces of the enemy’s guns, halted, delivered one round, and with a yell charged the battery, and captured several prisoners and every gun. These prisoners reported their battery was supported by four Ohio and three Illinois regiments.

It was a brilliant achievement, but an expensive one. In making the charge the enemy [regiment] lost 31 killed on the spot and 150 wounded; yet it illustrated and sustained the reputation for heroism of the gallant State of which it was a representative.

About 3 o’clock intelligence reached me that the commander-in-chief (General Johnston) had fallen. He fell in the discharge of his duty, leading and directing his troops. His loss was deeply felt. It was an event which deprived the army of his clear, practical judgment and determined character, and himself of an opportunity which he had coveted for vindicating his claims to the confidence of his countrymen against the inconsiderate and unjust reproaches which had been heaped upon him. The moral influence of his presence had, nevertheless, been already impressed upon the army and an impulse given to its action, which the news of his death increased instead of abated. The operations of the day had now become so far developed as to foreshadow the result with a good degree of certainty, and it was a melancholy fate to be cut off when victory seemed hastening to perch upon his standard. He was a true soldier, high-toned, eminently honorable, and just. Considerate of the rights and feelings of others, magnanimous, and brave. His military capacity was also of a high order, and his devotion to the cause of the South unsurpassed by that of any of her many noble sons who have offered up their lives on her altar. I knew him well from boyhood — none knew him better — and I take pleasure in laying on his tomb, as a parting offering, this testimonial of my appreciation of his character as a soldier, a patriot, and a man.

The enemy in our front was gradually and successively driven from his positions and forced from the field back on the river bank.

About 5 p.m. my line attacked the enemy’s troops — the last that were left upon the field — in an encampment on my right. The attack was made in front and flank. The resistance was sharp, but short. The enemy, perceiving he was flanked and his position completely turned, hoisted the white flag and surrendered. It proved to be the commands of Generals Prentiss and William H. L. Wallace; the latter, who commanded the left of their line, was killed by the troops of General Bragg, who was pressing him at the same time from that quarter. The former yielded to the attack of my troops on their right and delivered his sword with his command to Colonel Russell, one of my brigade commanders, who turned him over to me. The prisoners turned over were about 2,000. They were placed in charge of Lieutenant Richmond, my aide-de-camp, and with a detachment of cavalry sent to the rear.

I take pleasure in saying that in this part of the operations of my troops they were aided by the Crescent Regiment of Louisiana, Col. M. J. Smith.

This command was composed chiefly of young men from the city of New Orleans, and belonged to General Bragg’s corps. It had been posted on the left wing in the early part of the day to hold an important position, where it was detained, and did not reach the field until a late hour. On arriving, it came to the point at which I was commanding, and reported to me for orders. The conduct of this regiment during the whole afternoon was distinguished for its gallantry both before and after the capture of the command of General Prentiss, in which it actively participated.

Immediately after the surrender I ordered Colonel Lindsay, in command of one of the regiments of cavalry belonging to my corps, to take command of all the cavalry at hand and pursue such of the enemy as were fleeing. He detached Lieutenant-Colonel Miller, of his own regiment, on that service immediately, while he proceeded to collect and take charge of other commands. Colonel Miller dashed forward and intercepted a battery within 150 yards of the river — the Second Michigan and captured it before it could unlimber and open fire. It was a six-gun battery, complete in all its equipments, and was captured — men, horses, and guns. A portion of this cavalry rode to the river and watered their horses.

By this time the troops under my command were joined by those of Generals Bragg and Breckinridge and my Fourth Brigade, under General Cheatham, from the right. The field was clear; the rest of the forces of the enemy were driven to the river and under its bank. We had one hour or more of daylight still left; were within from 150 to 400 yards of the enemy’s position, and nothing seemed wanting to complete the most brilliant victory of the war but to press forward and make a vigorous assault on the demoralized remnant of his forces.

At this juncture his gunboats dropped down the river, near the Landing, where his troops were collected, and opened a tremendous cannonade of shot and shell over the bank in the direction from where our forces were approaching. The height of the plain on which we were, above the level of the water, was about 100 feet, so that it was necessary to give great elevation to his guns to enable him to fire over the bank. The consequence was that shot could take effect only at points remote from the river’s edge. They were comparatively harmless to our troops nearest the bank, and became increasingly so as we drew near the enemy and placed him between us and his boats.

Here the impression arose that our forces were waging an unequal contest; that they were exhausted and suffering from a murderous fire, and by an order from the commanding general they were withdrawn from the field.

One of my divisions (that of General Clark), consisting of Stewart’s and Russell’s brigades, now under the command of General Stewart, bivouacked on the ground with the rest of the troops, and were among the first to engage the enemy on the following morning. They were actively engaged during the day, and sustained the reputation they had won the day before.

The other division, under General Cheatham — a brigade of which was separated from me at an early hour on the 6th and was fought throughout the day with a skill and courage which always distinguishes that gallant officer — was moved by him to his camp of the night before. They were taken there to obtain rations and to prepare for the work of the following day. Hearing they had gone thither, I informed General Beauregard I should follow them, to insure their being on the ground at an early hour in the morning. This I did, and gave orders that night in person to General Cheatham to be ready to move at daylight. Before day I dispatched my aide-de-camp (Lieutenant Richmond) to put them in motion.

Their march was stopped for some time to arrest a stampede which came from the front. They then moved, under the command of General Cheatham, to the field. I sent forward a staff officer to General Beauregard to inform him of their approach, and was directed to post them in the rear of Shiloh Church and hold them until further orders. This was about 8 a.m.

It was not long before an order from the commanding general was received to move these troops to the support of the line in my front. They were formed in line of battle, and moved forward half a mile to the position held by General Breckinridge. Finding he was able to hold his position without assistance, they were moved by the left flank past Shiloh Church to form on left of our line. Here they were formed, under the supervision of General Cheatham, immediately in front of a very large force of the enemy, now pressing vigorously to turn our left flank. They engaged the enemy so soon as they were formed, and fought him for four hours one of the most desperately-contested conflicts of the battle. The enemy was driven gradually from his position, and though re-enforced several times during the engagement, he could make no impression on that part of our line.

During this engagement the command of General Cheatham was re-enforced by a Louisiana brigade, under Colonel Gibson, the Thirty-third Tennessee, under Colonel Campbell, and the Twenty-seventh Tennessee, under Major Love; all of whom did admirable service, and the last fell mortally wounded. Col. Preston Smith, commanding a brigade, was at the same time severely wounded, but retained his command.

This force maintained the position it had held for so many hours up to 2.30 o’clock, the time at which orders were received from the general commanding to withdraw the troops from the field. I gave orders accordingly, and the command was retired slowly and in good order in the direction of our camp, the enemy making no advance whatever.

In the operations of this morning, as well as the day before, those of my troops who acted under the immediate orders of Major-General Cheatham bore themselves with conspicuous gallantry. One charge particularly was made under the eye of the commander-in-chief and his staff, and drew forth expressions of the most unqualified applause.

For the details of these operations, as well as for those of the troops under General Clark, I beg leave to refer to the reports of those generals, herewith submitted; also to those of their brigade, regimental, and battery commanders.

The conduct of the troops of my corps, both officers and men, was of the most gratifying character; many of them had never been under fire before, and one company of artillery — that of Captain Stanford — from the scarcity of ammunition, had never before heard the report of their own guns. Yet, from that facility which distinguishes our Southern people, under the inspiration of the cause which animates them, they fought with the steadiness and gallantry of well-trained troops. The fact that the corps lost within a fraction of one-third of its number in killed and wounded attests the nature of the service in which it was engaged.

To my division commanders, Major-General Cheatham and Brigadier-General Clark, I feel greatly indebted for their cordial co-operation and efficient support; also to Brigadier-Generals Stewart and Johnson, and Colonels Russell, Maney, Stephens, and Preston Smith, commanders of brigades.

My obligations are also due to my personal and general staff. To Maj. George Williamson, my adjutant-general, who had his horse shot under him, and was himself wounded; to my inspector-general, Lieutenant-Colonel Blake; to my chief of artillery, Major Bankhead; to Captain Champney’s, my chief of ordnance, to whose vigilance and activity, in conjunction with the energetic and vigorous administration of my chief of artillery, I am indebted for taking off from the field thirteen of the fourteen guns reported by the general commanding to have been secured by the army from the enemy.

To my aides-de-camp, Lieuts. W. B. Richmond and A. H. Polk, I am particularly indebted for the promptitude and fidelity with which they performed the duties of their office. Their fearless bearing was eminently conspicuous. The former had two horses shot under him.

I am under obligations also to Lieutenants Spence, Lanier, and Rawle, who acted on my staff during the battle; also to Lieut. W. M. Porter, who acted as volunteer aide during the operations of the 6th; also to my quartermaster, Maj. Thomas Peters, and my medical director, Dr. W. D. Lyles.

Above all, I feel I am indebted to Almighty God for the courage with which he inspired our troops and for the protection and defense with which he covered our heads in the day of battle.

I remain, respectfully, your obedient servant,

L. POLK,

Maj. Gen., Comdg. First Corps, Army of the Mississippi.

General S. Cooper,

Adjutant and Inspector-General C. S. Army, Richmond, Va.

Notes

- Bivouac (/'biv.u.æk/, /'biv.wæk/)(verb) To stay in a temporary camp without cover.

Text prepared by:

- Michael Bearden

- Bruce R. Magee

- Rachel Smith

- Ainsley Terrill

Source

Polk, Leonidas. “No. 140.” Comp. Robert N. Scott. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of The Official Records of The Union and Confederate Armies. Ser. 1. Vol. 10. Part 1. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1884. 405-412. Web. Google Books. 21 June 2017 <https:// books. google.com/ books?id= _0Y4AQAAMAAJ>.