Chapter I

Chapter I

1814

ON THE OCEAN

Strictness of the blockade — Cruise of

Rodgers — Cruise of the

Constitution — Her unsuccessful chase of La Pique — Attack

on the

Alligator — The Essex captured — The Frolic captured — The

Peacock captures the Epervier — Commodore Barney’s

flotilla — The

British in the Chesapeake — The Wasp captures the

Reindeer and

sinks the Avon — Cruise and loss of the Adams — The

privateer

General Armstrong — The privateer Prince de Neufchâtel — Loss

of

the gunboats in Lake Borgne — Fighting near New Orleans — Summary.

DURING

this year the blockade of the American coast

was kept up

with ever increasing rigor. The British frigates hovered like

hawks

off every seaport that was known to harbor any fighting craft;

they

almost invariably went in couples, to support one another and to

lighten, as far as was possible, the severity of their work. On

the

northern coasts in particular, the intense cold of the furious

winter

gales rendered it no easy task to keep the assigned stations; the

ropes were turned into stiff and brittle bars, the hulls were

coated

with ice, and many, both of men and officers, were frost-bitten

and

crippled. But no stress of weather could long keep the stubborn

and

hardy British from their posts. With ceaseless vigilance they

traversed

continually the allotted cruising grounds, capturing the

privateers,

harrying the coasters, and keeping the more powerful ships

confined

to port; “no American frigate could proceed singly to sea without

imminent risk of being crushed by the superior force of the

numerous

British

squadrons.”

But the sloops of war, commanded by officers

as skillful as they were daring, and manned by as hardy seamen as

ever sailed salt water, could often slip out; generally on some

dark

night, when a heavy gale was blowing, they would make the attempt,

under storm canvas, and with almost invariable success. The harder

the weather, the better was their chance; once clear of the coast

the greatest danger ceased, though throughout the cruise the most

untiring vigilance was needed. The new sloops that I have

mentioned

as being built proved themselves the best possible vessels for

this

kind of work; they were fast enough to escape from most cruisers

of

superior force, and were overmatches for any British flush-decked

ship, that is, for any thing below the rank of the frigate-built

corvettes of the Cyane’s class. The danger of recapture

was too

great to permit of the prizes being sent in, so they were

generally

destroyed as soon as captured; and as the cruising grounds were

chosen

right in the track of commerce, the damage done and consternation

caused were very great.

Besides the numerous frigates cruising along the

coast in couples

or small squadrons, there were two or three places that were

blockaded

by a heavier force. One of these was New London, before which

cruised

a squadron under the direction of Sir Thomas Hardy, in the 74

gun-ship

Ramillies. Most of the other cruising squadrons off the

coast contained

razees or two-deckers. The boats of the Hogue, 74, took

part in

the destruction of some coasters and fishing-boats at Pettipauge

in

April; and those of the Superb, 74, shared in a similar

expedition

against Wareham in

June.

The command

on

the coast of North America was now given to Vice-Admiral Sir

Alexander

Cochrane. The main British force continued to lie in the

Chesapeake,

where about 50 sail were collected. During the first part of this

year these were under the command of Sir Robert Barrie, but in May

he was relieved by Rear-Admiral

Cockburn.

The President, 44, Commodore Rodgers, at the

beginning of 1814

was still out, cruising among the Barbadoes and West Indies, only

making a few prizes of not much value. She then turned toward the

American coast, striking soundings near St. Augustine, and thence

proceeding north along the coast to Sandy Hook, which was reached

on Feb. 18th. The light was passed in the night, and shortly

afterward

several sail were made out, when the President was at once

cleared

for

action.

One of these strange sail was the Loire, 38 (British),

Captain Thomas

Brown, which ran down to close the President, unaware of

her force;

but on discovering her to be a 44, hauled to the wind and made

off.

The President did not pursue,

another

frigate and a gunbrig being in

sight.

This rencontre gave rise to nonsensical boastings on both

sides; one American writer calls the Loire the Plantagenet,

74;

James, on the other hand, states that the President was

afraid to

engage the 38-gun frigate, and that the only reason the latter

declined

the combat was because she was short of men. The best answer to

this

is a quotation from his own work (vol. vi, p. 402), that “the

admiralty

had issued an order that no 18-pounder frigate was voluntarily to

engage one of the 24-pounder frigates of America.” Coupling this

order with the results of the combats that had already taken place

between frigates of these classes, it can always be safely set

down

as sheer bravado when any talk is made of an American 44 refusing

to give battle to a British 38; and it is even more absurd to say

that a British line-of-battle ship would hesitate for a minute

about

engaging any frigate.

On Jan. 1st, the Constitution, which had

been lying in Boston harbor

undergoing complete repairs, put out to sea under the command of

Captain Charles Stewart. The British 38-gun frigate Nymphe

had been

lying before the port, but she disappeared long before the

Constitution was in condition, in obedience to the order

already

mentioned. Captain Stewart ran down toward the Barbadoes, and on the

14th of February captured and destroyed the British 14-gun

schooner

Pictou, with a crew of 75 men. After making a few other

prizes

and reaching the coast of Guiana she turned homeward, and on the

23d of the same month fell in, at the entrance to the Mona

passage,

with the British 36-gun frigate Pique (late French Pallas),

Captain

Maitland. The Constitution at once made sail for the Pique,

steering

free;

the

latter

at first hauled to the wind and waited for her antagonist, but

when

the latter was still 3 miles distant she made out her force and

immediately made all sail to escape; the Constitution,

however,

gained steadily till 8 P.M., when the night and thick squally

weather

caused her to lose sight of the chase. Captain Maitland had on

board

the prohibitory order issued by the

admiralty,

and acted correctly. His ship was altogether too light

for his antagonist. James, however, is not satisfied with this,

and

wishes to prove that both ships were desirous of avoiding

the combat.

He says that Captain Stewart came near enough to count “13 ports and

a bridle on the Pique’s main-deck,” and “saw at once that

she was

of a class inferior to the Guerrière or Java,” but

“thought the

Pique’s 18’s were 24’s, and therefore did not make an

effort to

bring her to action.” He portrays very picturesquely the grief of

the Pique’s crew when they find they are not going to

engage; how

they come aft and request to be taken into action; how Captain

Maitland

reads them his instructions, but “fails to persuade them that

there

had been any necessity of issuing them“; and, finally, how the

sailors,

overcome by woe and indignation, refuse to take their supper-time

grog, — which was certainly remarkable. As the Constitution

had

twice captured British frigates “with impunity,” according to

James

himself, is it likely that she would now shrink from an encounter

with a ship which she “saw at once was of an inferior class” to

those

already conquered? Even such abject cowards as James’ Americans

would

not be guilty of so stupid an action. Of course neither Captain

Stewart

nor any one else supposed for an instant that a 36-gun frigate was

armed with 24-pounders.

It is worth while mentioning as an instance of how

utterly untrustworthy

James is in dealing with American affairs, that he says (p. 476)

the Constitution had now “what the Americans would call a

bad crew,”

whereas, in her previous battles, all her men had been “picked.”

Curiously enough, this is the exact reverse of the truth. In no

case

was an American ship manned with a “picked” crew, but the nearest

approach to such was the crew the Constitution carried in

this

and the next cruise, when “she probably possessed as fine a crew

as ever manned a frigate. They were principally New England men,

and it has been said of them that they were almost qualified to

fight

the ship without her

officers.”

The statement that such men, commanded by one of the bravest and most

skilful captains of our navy, would shrink from attacking a

greatly

inferior foe, is hardly worth while denying; and, fortunately,

such

denial is needless, Captain Stewart’s account being fully

corroborated

in the Memoir of Admiral Durham, written by his nephew, Captain

Murray, London, 1846.

The Constitution arrived off the port of

Marblehead on April 3d,

and at 7 A.M. fell in with the two British 38-gun frigates Junon,

Captain Upton, and Tenedos, Captain Parker. “The American

frigate

was standing to the westward with the wind about north by west and

bore from the two British frigates about northwest by west. The

Junon and Tenedos quickly hauled up in chase, and

the Constitution

crowded sail in the direction of Marblehead. At 9.30, finding the

Tenedos rather gaining upon her, the Constitution

started her

water and threw overboard a quantity of provisions and other

articles.

At 11.30 she hoisted her colors, and the two British frigates, who

were now dropping slowly in the chase, did the same. At 1.30 P.M.

the Constitution anchored in the harbor of Marblehead.

Captain

Parker was anxious to follow her into the port, which had no

defences;

but the Tenedos was recalled by a signal from the

Junon.”

Shortly afterward the Constitution

again put out, and reached Boston unmolested.

On Jan. 29, 1814, the small U.S. coasting schooner Alligator,

of

4 guns and 40 men, Sailing-master R. Basset, was lying at anchor

in the mouth of Stone River, S. C., when a frigate and a brig were

perceived close inshore near the breakers. Judging from their

motions

that they would attempt to cut him out when it was dark, Mr.

Basset

made his preparations

accordingly.

At half-past seven six boats were observed

approaching cautiously under cover of the marsh, with muffled

oars;

on being hailed they cheered and opened with boat carronades and

musketry, coming on at full speed; whereupon the Alligator

cut

her cable and made sail, the wind being light from the southwest;

while the crew opened such a heavy fire on the assailants, who

were

then not thirty yards off, that they stopped the advance and fell

astern. At this moment the Alligator grounded, but the

enemy had

suffered so severely that they made no attempt to renew the

attack,

rowing off down stream. On board the Alligator two men

were killed

and two wounded, including the pilot, who was struck down by a

grape-shot while standing at the helm; and her sails and rigging

were much cut. The extent of the enemy’s loss was never known;

next

day one of his cutters was picked up at North Edisto, much injured

and containing the bodies of an officer and a

seaman.

For his skill

and

gallantry Mr. Basset was promoted to a lieutenancy, and for a time

his exploit put a complete stop to the cutting-out expeditions

along

that part of the coast. The Alligator herself sank in a

squall on

July 1st, but was afterward raised and refitted.

It is much to be regretted that it is almost

impossible to get at

the British account of any of these expeditions which ended

successfully for the Americans; all such cases are generally

ignored

by the British historians; so that I am obliged to rely solely

upon

the accounts of the victors, who, with the best intentions in the

world, could hardly be perfectly accurate.

At the close of 1813 Captain Porter was still

cruising in the Pacific.

Early in January the Essex, now with 255 men

aboard, made the South

American coast, and on the 12th of that month anchored in the

harbor

of Valparaiso. She had in company a prize, re-christened the Essex

Junior, with a crew of 60 men, and 20 guns, 10 long sixes

and 10

eighteen-pound carronades. Of course she could not be used in a

combat

with regular cruisers.

On Feb. 8th, the British frigate Phœbe, 36,

Captain James Hilyar,

accompanied by the Cherub, 18, Captain Thomas Tudor

Tucker, the

former carrying 300 and the latter 140

men,

made their appearance,

and apparently proposed to take the Essex by a coup de

main.

They hauled into the harbor on a wind, the Cherub falling

to leeward;

while the Phœbe made the port quarter of the Essex,

and then,

putting her helm down, luffed up on her starboard bow, but 10 or

15 feet distant. Porter’s crew were all at quarters, the

powder-boys

with slow matches ready to discharge the guns, the boarders

standing

by, cutlass in hand, to board in the smoke; every thing was

cleared

for action on both frigates. Captain Hilyar now probably saw that

there was no chance of carrying the Essex by surprise,

and, standing

on the after-gun, he inquired after Captain Porter’s health; the

latter returned the inquiry, but warned Hilyar not to fall foul.

The British captain then braced back his yards, remarking that if

he did fall aboard it would be purely accidental. “Well,” said

Porter, “you have no business where you are; if you touch a

rope-yarn

of this ship I shall board

instantly.”

The Phœbe, in her then position, was completely

at the

mercy of the American ships, and Hilyar, greatly agitated, assured

Porter that he meant nothing hostile; and the Phœbe

backed down,

her yards passing over those of the Essex without touching

a rope,

and anchored half a mile astern. Shortly afterward the two

captains

met on shore, when Hilyar thanked Porter for his behavior, and, on

his inquiry, assured him that after thus owing his safety to the

latter’s forbearance, Porter need be under no apprehension as to

his breaking the neutrality.

The USS Essex.

Painting by Joseph Howard.

The British ships now began a blockade of the port.

On Feb. 27th,

the Phœbe being hove to close off the port, and the Cherub

a

league to leeward, the former fired a weather-gun; the Essex

interpreting this as a challenge, took the crew of the Essex

Junior

aboard and went out to attack the British frigate. But the latter

did

not await the combat; she bore up, set her studding-sails, and ran

down to the Cherub. The American officers were intensely

irritated

over this, and American writers have sneered much at "a British 36

refusing combat with an American 32.” But the armaments of the two

frigates were so wholly dissimilar that it is hard to make

comparison.

When the fight really took place, the Essex was so crippled and

the

water so smooth that the British ships fought at their own

distance;

and as they had long guns to oppose to Porter’s carronades, this

really made the Cherub more nearly suited to contend with

the Essex

than the latter was to fight the Phœbe. But when the Essex

in

fairly heavy weather, with the crew of the Essex Junior

aboard,

was to windward, the circumstances were very different; she

carried

as many men and guns as the Phœbe, and in close combat,

or in

a hand-to-hand struggle, could probably have taken her. Still,

Hilyar’s

conduct in avoiding Porter except when the Cherub was in

company

was certainly over-cautious, and very difficult to explain in a

man

of his tried courage.

On March 27th Porter decided to run out of the

harbor on the first

opportunity, so as to draw away his two antagonists in chase, and

let the Essex Junior escape. This plan had to be tried

sooner than

was expected. The two vessels were always ready, the Essex

only

having her proper complement of 255 men aboard. On the next day,

the 28th, it came on to blow from the south, when the Essex

parted

her port cable and dragged the starboard anchor to leeward, so she

got under way, and made sail; by several trials it had been found

that she was faster than the Phœbe, and that the Cherub

was

very slow indeed, so Porter had little anxiety about his own ship,

only fearing for his consort. The British vessels were close in

with

the weather-most point of the bay, but Porter thought he could

weather

them, and hauled up for that purpose. Just as he was rounding the

outermost point, which, if accomplished, would have secured his

safety,

a heavy squall struck the Essex, and when she was nearly

gunwale

under, the main-top-mast went by the board. She now wore and stood

in for the harbor, but the wind had shifted, and on account of her

crippled condition she could not gain it; so she bore up and

anchored

in a small bay, three miles from Valparaiso, and half a mile from

a detached Chilian battery of one gun, the Essex being

within

pistol-shot of the

shore.

The Phœbe and Cherub now bore down

upon her,

covered with ensigns, union-jacks, and motto flags; and it became

evident that Hilyar did not intend to keep his word, as soon as he

saw that Porter was disabled. So the Essex prepared for

action,

though there could be no chance whatever of success. Her flags

were

flying from every mast, and every thing was made ready as far as

was possible. The attack was made before springs could be got on

her cables. She was anchored so near the shore as to preclude the

possibility of Captain Hilyar’s passing ahead of

her;

so his two ships

came cautiously down, the Cherub taking her position on

the

starboard bow of the Essex, and the Phœbe under

the latter’s

stern. The attack began at

4 P.M.

Some of the bow-guns of the American frigate bore upon the

Cherub, and, as soon as she found this out, the sloop ran

down

and stationed herself near the Phœbe. The latter had

opened with

her broadside of long 18’s, from a position in which not one of

Porter’s guns could reach her. Three times springs were got on the

cables of the Essex, in order to bring her round till her

broadside

bore; but in each instance they were shot away, as soon as they

were

hauled taut. Three long 12’s were got out of the stern-ports, and

with these an animated fire was kept up on the two British ships,

the aim being especially to cripple their rigging. A good many of

Porter’s crew were killed during the first five minutes, before he

could bring any guns to bear; but afterward he did not suffer

much,

and at 4.20, after a quarter of an hour’s fight between the three

long 12’s of the Essex, and the whole 36 broadside guns of

the

Phœbe and Cherub, the latter were actually driven

off. They

wore, and again began with their long guns; but, these producing

no visible effect, both of the British ships hauled out of the

fight

at 4.30. “Having lost the use of main-sail, jib, and main-stay,

appearances looked a little inauspicious,” writes Captain Hilyar.

But the damages were soon repaired, and his two ships stood back

for the crippled foe. Both stationed themselves on her

port-quarter,

the Phœbe at anchor, with a spring, firing her broadside,

while

the Cherub kept under way, using her long bow-chasers.

Their fire

was very destructive, for they were out of reach of the Essex’s

carronades, and not one of her long guns could be brought to bear

on them. Porter now cut his cable, at 5.20, and tried to close

with

his antagonists. After many ineffectual efforts sail was made. The

flying-jib halyards were the only serviceable ropes uncut. That

sail

was hoisted, and the foretop-sail and fore-sail let fall, though

the

want of sheets and tacks rendered them almost useless. Still the

Essex drove down on her assailants, and for the first time

got

near enough to use her carronades; for a minute or two the firing

was tremendous, but after the first broadside the Cherub

hauled

out of the fight in great haste, and during the remainder of the

action confined herself to using her bow-guns from a distance.

Immediately afterward the Phœbe also edged off, and by

her

superiority of sailing, her foe being now almost helpless, was

enabled

to choose her own distance, and again opened from her long 18’s,

out of range of Porter’s

carronades.

The

carnage

on board the Essex had now made her decks look like

shambles. One

gun was manned three times, fifteen men being slam at it; its

captain

alone escaped without a wound. There were but one or two instances

of flinching; the wounded, many of whom were killed by flying

splinters

while under the hands of the doctors, cheered on their comrades,

and themselves worked at the guns like fiends as long as they

could

stand. At one of the bow-guns was stationed a young Scotchman,

named

Bissly, who had one leg shot off close by the groin. Using his

handkerchief as a tourniquet, he said, turning to his American

shipmates: “I left my own country and adopted the United States,

to fight for her. I hope I have this day proved myself worthy of

the country of my adoption. I am no longer of any use to you or to

her, so good-by!” With these words he leaned on the sill of the

port,

and threw himself

overboard.

Among the very few men who flinched was one named William Roach;

Porter sent one of his midshipmen to shoot him, but he was not to

be found. He was discovered by a man named William Call, whose leg

had been shot off and was hanging by the skin, and who dragged the

shattered stump all round the bag-house, pistol in hand, trying to

get a shot at him. Lieutenant J. G. Cowell had his leg shot off above

the knee, and his life might have been saved had it been amputated

at once; but the surgeons already had rows of wounded men waiting

for them, and when it was proposed to him that he should be

attended

to out of order, he replied: “No, doctor, none of that; fair

play’s

a jewel. One man’s life is as dear as another’s; I would not cheat

any poor fellow out of his turn.” So he stayed at his post, and

died from loss of blood.

Captain David Porter.

Painting possibly by John Trumbull.

Finding it hopeless to try to close, the Essex

stood for the land,

Porter intending to run her ashore and burn her. But when she had

drifted close to the bluffs the wind suddenly shifted, took her

flat

aback and paid her head off shore, exposing her to a raking fire.

At

this moment Lieutenant Downes, commanding the Junior,

pulled out

in a boat, through all the fire, to see if he could do any thing.

Three of the men with him, including an old boatswain’s mate,

named

Kingsbury, had come out expressly “to share the fate of their old

ship” so they remained aboard, and, in their places, Lieutenant

Downes took some of the wounded ashore, while the Cherub kept up a

tremendous fire upon him. The shift of the wind gave Porter a

faint

hope of closing; and once more the riddled hulk of the little

American

frigate was headed for her foes. But Hilyar put his helm up to

avoid

close quarters; the battle was his already, and the cool old

captain

was too good an officer to leave any thing to chance. Seeing he

could not close, Porter had a hawser bent on the sheet-anchor and

let go. This brought the ship’s head round, keeping her

stationary;

and from such of her guns as were not dismounted and had men

enough

left to man them, a broadside was fired at the Phœbe. The

wind

was now very light, and the Phœbe, whose main- and

mizzen-masts

and main-yard were rather seriously wounded, and who had suffered

a great loss of canvas and cordage aloft, besides receiving a

number

of shot between wind and

water,

and was thus a good

deal

crippled, began to drift slowly to leeward. It was hoped that she

would drift out of gun-shot, but this last chance was lost by the

parting of the hawser, which left the Essex at the mercy

of the

British vessels. Their fire was deliberate and destructive, and

could

only be occasionally replied to by a shot from one of the long

12’s

of the Essex. The ship caught fire, and the flames came

bursting

up the hatchway, and a quantity of powder exploded below. Many of

the crew were knocked overboard by shot, and drowned; others

leaped

into the water, thinking the ship was about to blow up, and tried

to swim to the land. Some succeeded; among them was one man who

had

sixteen or eighteen pieces of iron in his leg, scales from the

muzzle

of his gun. The frigate had been shattered to pieces above the

water-line, although from the smoothness of the sea she was not

harmed

enough below it to reduce her to a sinking

condition.

The

carpenter reported that he alone of his crew was fit for duty;

the others were dead or disabled. Lieutenant Wilmer was knocked

overboard by a splinter, and drowned; his little negro boy,

“Ruff,”

came up on deck, and, hearing of the disaster, deliberately leaped

into the sea and shared his master’s fate. Lieutenant Odenheimer

was also knocked overboard, but afterward regained the ship. A

shot,

glancing upward, killed four of the men who were standing by a

gun,

striking the last one in the head and scattering his brains over

his comrades. The only commissioned officer left on duty was

Lieutenant

Decatur McKnight. The sailing-master, Barnwell, when terribly

wounded,

remained at his post till he fainted from loss of blood. Of the

255

men aboard the Essex when the battle began, 58 had been

killed,

66 wounded, and 31 drowned (“missing”), while 24 had succeeded in

reaching shore. But 76 men were left unwounded, and many of these

had been bruised or otherwise injured. Porter himself was knocked

down by the windage of a passing shot. While the young midshipman,

Farragut, was on the ward-room ladder, going below for

gun-primers,

the captain of the gun directly opposite the hatchway was struck

full in the face by an 18-pound shot, and tumbled back on him.

They

fell down the hatch together, Farragut being stunned for some

minutes.

Later, while standing by the man at the wheel, an old

quartermaster

named Francis Bland, a shot coming over the fore-yard took off the

quartermaster’s right leg, carrying away at the same time one of

Farragut’s coat tails. The old fellow was helped below, but he

died

for lack of a tourniquet, before he could be attended to.

Nothing remained to be done, and at 6.20 the Essex

surrendered

and was taken possession of. The Phœbe had lost 4 men

killed,

including her first lieutenant, William Ingram, and 7 wounded; the

Cherub, 1 killed, and 3, including Captain Tucker, wounded.

Total,

5 killed and 10

wounded.

The difference in loss was natural, as, owing to

their having long guns and the choice of position, the British had

been able to fire ten shot to the Americans’ one.

The conduct of the two English captains in attacking

Porter as soon

as he was disabled, in neutral waters, while they had been very

careful

to abstain from breaking the neutrality while he was in good

condition,

does not look well; at the best it shows that Hilyar had only been

withheld hitherto from the attack by timidity, and it looks all

the

worse when it is remembered that Hilyar owed his ship’s previous

escape entirely to Porter’s forbearance on a former occasion when

the British frigate was entirely at his mercy, and that the

British

captain had afterward expressly said that he would not break the

neutrality. Still, the British in this war did not act very

differently

from the way we ourselves did on one or two occasions in the Civil

War, — witness the capture of the Florida. And after the

battle

was once begun the sneers which most of our historians, as well as

the participators in the fight, have showered upon the British

captains for not foregoing the advantages which their entire masts

and better artillery gave them by coming to close quarters, are

decidedly foolish. Hilyar’s conduct during the battle, as well as

his treatment of the prisoners afterward, was perfect, and as a

minor

matter it may be mentioned that his official letter is singularly

just and fair-minded. Says Lord Howard

Douglass:

“The action displayed all that can reflect

honor

on the science and admirable conduct of Captain Hilyar and his

crew,

which, without the assistance of the Cherub, would have

insured

the same termination. Captain Porter’s sneers at the respectful

distance the Phœbe kept are in fact acknowledgments of

the ability

with which Captain Hilyar availed himself of the superiority of

his

arms; it was a brilliant affair.” While endorsing this criticism,

it may be worth while to compare it with some of the author’s

comments

upon the other actions, as that between Decatur and the Macedonian.

To make the odds here as great against Garden as they were against

Porter, it would be necessary to suppose that the Macedonian

had

lost her main-top-mast, had but six long 18’s to oppose to her

antagonist’s 24’s, and that the latter was assisted by the

corvette

Adams; so that as a matter of fact Porter fought at fully

double

or treble the disadvantage Garden did, and, instead of

surrendering

when he had lost a third of his crew, fought till three fifths of

his men were dead or wounded, and, moreover, inflicted greater

loss

and damage on his antagonists than Garden did. If, then, as Lord

Douglass says, the defence of the Macedonian brilliantly

upheld

the character of the British navy for courage, how much more did

that of the Essex show for the American navy; and if

Hilyar’s

conduct was “brilliant,” that of Decatur was more so.

This was an action in which it is difficult to tell

exactly how to

award praise. Captain Hilyar deserves it, for the coolness and

skill

with which he made his approaches and took his positions so as to

destroy his adversary with least loss to himself, and also for the

precision of his fire. The Cherub’s behavior was more remarkable

for extreme caution than for any thing else. As regards the mere

fight, Porter certainly did every thing a man could do to contend

successfully with the overwhelming force opposed to him, and the

few guns that were available were served with the utmost

precision.

As an exhibition of dogged courage it has never been surpassed

since

the time when the Dutch captain, Klaesoon, after fighting two long

days, blew up his disabled ship, devoting himself and all his crew

to death, rather than surrender to the hereditary foes of his

race,

and was bitterly avenged afterward by the grim “sea-beggars” of

Holland; the days when Drake singed the beard of the Catholic

king,

and the small English craft were the dread and scourge of the

great

floating castles of Spain. Any man reading Farragut’s account is

forcibly reminded of some of the deeds of “derring do” in that,

the

heroic age of the Teutonic navies. Captain Hilyar in his letter

says:

“The defence of the Essex, taking into consideration our

superiority

of force and the very discouraging circumstances of her having

lost

her main-top-mast and being twice on fire, did honor to her brave

defenders, and most fully evinced the courage of Captain Porter

and

those under his command. Her colors were not struck until the loss

in killed and wounded was so awfully great and her shattered

condition

so seriously bad as to render all further resistance

unavailing.”

He also bears very candid testimony to

the defence of the Essex having been effective enough to

at one

time render the result doubtful, saying: “Our first attack * * *

produced no visible effect. Our second * * * was not more

successful;

and having lost the use of our main-sail, jib, and main-stay,

appearances looked a little inauspicious.” Throughout the war no

ship was so desperately defended as the Essex, taking into

account

the frightful odds against which she fought, which always enhances

the merit of a defence. The Lawrence, which suffered even

more,

was backed by a fleet; the Frolic was overcome by an equal

foe;

and the Reindeer fought at far less of a disadvantage, and

suffered

less. None of the frigates, British or American, were defended

with

any thing like the resolution she displayed.

But it is perhaps permissible to inquire whether

Porter’s course,

after the accident to his top-mast occurred, was altogether the

best

that could have been taken. On such a question no opinion could

have

been better than Farragut’s, although of course his judgment was

ex post facto, as he was very young at the time of the

fight.

“In the first place, I consider our original and

greatest error was

in attempting to regain the anchorage; being greatly superior in

sailing powers we should have borne up and run before the wind.

If we had come in contact with the Phœbe we should have

carried

her by boarding; if she avoided us, as she might have done by her

greater ability to manoeuvre, then we should have taken her fire

and passed on, leaving both vessels behind until we had replaced

our top-mast, by which time they would have been separated, as

unless

they did so it would have been no chase, the Cherub being

a dull

sailer.”

“Secondly, when it was apparent to everybody that we

had no chance

of success under the circumstances, the ship should have been run

ashore, throwing her broadside to the beach to prevent raking, and

fought as long as was consistent with humanity, and then set on

fire.

But having determined upon anchoring we should have bent a spring

on to the ring of the anchor, instead of to the cable, where it

was

exposed, and could be shot away as fast as put on.”

But it must be remembered that when Porter decided

to anchor near

shore, in neutral water, he could not anticipate Hilyar’s

deliberate

and treacherous breach of faith. I do not allude to the mere

disregard

of neutrality. Whatever international moralists may say, such

disregard is a mere question of expediency. If the benefits to be

gained by attacking a hostile ship in neutral waters are such as

to

counterbalance the risk of incurring the enmity of the neutral

power, why then the attack ought to be made. Had Hilyar, when he

first made his appearance off Valparaiso, sailed in with his two

ships, the men at quarters and guns out, and at once attacked

Porter, considering the destruction of the Essex as

outweighing

the insult to Chili, why his behavior would have been perfectly

justifiable. In fact this is unquestionably what he intended to

do,

but he suddenly found himself in such a position, that in the even

of hostilities, his ship would be the captured one, and he

owed

his escape purely to Porter’s over-forbearance, under great

provocation

Then he gave his word to Potter that he would not infringe on the

neutrality; and he never dared to break it, until he saw Porter

was

disabled and almost helpless! This may seem strong language to use

about a British officer, but it is justly strong. Exactly as any

outsider must consider Warrington’s attack on the British brig

Nautilus in 1815, as a piece of needless cruelty; so any

outsider

must consider Hilyar as having most treacherously broken faith

with

Porter.

After the fight Hilyar behaved most kindly and

courteously to the

prisoners; and, as already said, he fought his ship most ably, for

it would have been quixotic to a degree to forego his advantages.

But previous to the battle his conduct had been over-cautious. It

was to be expected that the Essex would make her escape as

soon

as practicable, and so he should have used every effort to bring

her to action. Instead of this he always declined the fight when

alone; and he owed his ultimate success to the fact that the Essex

instead of escaping, as she could several times have done, stayed,

hoping to bring the Phœbe to action single-handed. It

must be

remembered that the Essex was almost as weak compared to

the

Phœbe, as the Cherub was compared to the Essex.

The latter

was just about midway between the British ships, as may be seen by

the following comparison. In the action the Essex fought

all six

of her long 12’s, and the Cherub both her long 9’s,

instead of

the corresponding broadside carronades which the ships regularly

used. This gives the Essex a better armament than she

would have

had fighting her guns as they were regularly used; but it can be

seen how great the inequality still was. It must also be kept in

mind, that while in the battles between the American 44’s and

British 38’s, the short weight 24-pounders of the former had in

reality no greater range or accuracy than the full weight 18’s of

their opponents, in this case the Phœbe’s full weight

18’s had

a very much greater range and accuracy than the short weight 12’s

of the Essex.

All accounts agree as to the armament of the Essex.

I have taken

that of the Phœbe and Cherub from James; but

Captain Porter’s

official letter, and all the other American accounts make the

Phœbe’s broadside 15 long 18’s and 8 short 32’s, and give

the

Cherub, in all, 18 short 32’s, 8 short 24’s, and two long

nines.

This would make their broadside 904 lbs., 288 long, 616 short. I

would have no doubt that the American accounts were right if the

question rested solely on James’ veracity; but he probably took

his

figures from official sources. At any rate, remembering the

difference

between long guns and carronades, it appears that the Essex

was

really nearly intermediate in force between the Phœbe and

the

Cherub. The battle being fought, with a very trifling

exception,

at long range, it was in reality a conflict between a crippled

ship

throwing a broadside of 66 lbs. of metal, and two ships throwing

273 lbs., who by their ability to manoeuvre could choose positions

where they could act with full effect, while their antagonist

could

not return a shot. Contemporary history does not afford a single

instance of so determined a defence against such frightful odds.

The official letters of Captains Hilyar and Porter

agree substantially

in all respects; the details of the fight, as seen in the Essex,

are found in the “Life of Farragut.” But although the British

captain

does full justice to his foe, British historians have universally

tried to belittle Porter’s conduct. It is much to be regretted

that

we have no British account worth paying attention to of the

proceedings

before the fight, when the Phœbe declined single combat

with the

Essex. James, of course, states that the Phœbe did

not decline

it, but he gives no authority, and his unsupported assertion would

be valueless even if uncontradicted. His account of the action is

grossly inaccurate as he has inexcusably garbled Hilyar’s report.

One instance of this I have already mentioned, as regards Hilyar’s

account of Porter’s loss. Again, Hilyar distinctly states that the

Essex was twice on fire, yet James (p. 418) utterly denies

this,

thereby impliedly accusing the British captain of falsehood. There

is really no need of the corroboration of Porter’s letter, but he

has it most fully in the “Life of Farragut,” p. 37: “The men came

rushing up from below, many with their clothes burning, which were

torn from them as quickly as possible, and those for whom this

could

not be done were told to jump overboard and quench the flames. * *

*

One man swam to shore with scarcely a square inch of his body

which

had not been burned, and, although he was deranged for some days,

he ultimately recovered, and afterward served with me in the West

Indies.” The third unfounded statement in James’ account is that

buckets of spirits were found in all parts of the main deck of the

Essex, and that most of the prisoners were drunk. No

authority

is cited for this, and there is not a shadow of truth in it. He

ends

by stating that “few even in his own country will venture to speak

well of Captain David Porter.” After these various paragraphs we

are certainly justified in rejecting James’ account in toto.

An

occasional mistake is perfectly excusable, and gross ignorance of

a good many facts does not invalidate a man’s testimony with

regard

to some others with which he is acquainted; but a wilful and

systematic

perversion of the truth in a number of cases throws a very strong

doubt on a historian’s remaining statements, unless they are

supported

by unquestionable authority.

But if British historians have generally given

Porter much less than

his due, by omitting all reference to the inferiority of his guns,

his lost top-mast, etc., it is no worse than Americans have done

in

similar cases. The latter, for example, will make great allowances

in the case of the Essex for her having carronades only,

but utterly

fail to allude to the Cyane and Levant as having

suffered under

the same disadvantage. They should remember that the rules cut

both ways.

The Essex having suffered chiefly above the

waterline, she was

repaired sufficiently in Valparaiso to enable her to make the

voyage

to England, where she was added to the British navy. The Essex

Junior

was disarmed and the American prisoners embarked in her for New

York,

on parole. But Lieutenant McKnight, Chaplain Adams, Midshipman

Lyman,

and 11 seamen were exchanged on the spot for some of the British

prisoners on board the Essex Junior. McKnight and Lyman

accompanied

the Phœbe to Rio Janeiro, where they embarked on a

Swedish vessel,

were taken out of her by the Wasp, Captain Blakely, and

were lost

with the rest of the crew of that vessel. The others reached New

York in safety. Of the prizes made by the Essex, some were

burnt

or sunk by the Americans, and some retaken by the British. And so,

after nearly two years’ uninterrupted success, the career of the

Essex terminated amid disasters of all kinds. But at least

her

officers and crew could reflect that they had afforded an example

of courage in adversity that it would be difficult to match

elsewhere.

The first of the new heavy sloops of war that got to

sea was the

Frolic, Master Commandant Joseph Bainbridge, which put out

early

in February. Shortly afterward she encountered a large

Carthagenian

privateer, which refused to surrender and was sunk by a broadside,

nearly a hundred of her crew being drowned. Before daylight on the

20th of April, lat. 24° 12’ N., long. 81° 25’ W., she fell in with

the British 36-gun frigate Orpheus, Captain Pigot, and the

12-gun

schooner Shelburne, Lieutenant Hope, both to leeward. The

schooner

soon weathered the Frolic, but of course was afraid to

close, and

the American sloop continued beating to windward, in the effort to

escape, for nearly 13 hours; the water was started, the anchors

cut

away, and finally the guns thrown overboard — a measure by means of

which both the Hornet, the Rattlesnake, and the Adams

succeeded

in escaping under similar circumstances, — but all was of no avail,

and she was finally captured. The court of inquiry honorably

acquitted

both officers and crew. As was to be expected James considers the

surrender a disgraceful one, because the guns were thrown

overboard.

As I have said, this was a measure which had proved successful in

several cases of a like nature; the criticism is a piece of petty

meanness. Fortunately we have Admiral Codrington’s dictum on the

surrender (“Memoirs,” vol. 1, p. 310), which he evidently

considered

as perfectly honorable.

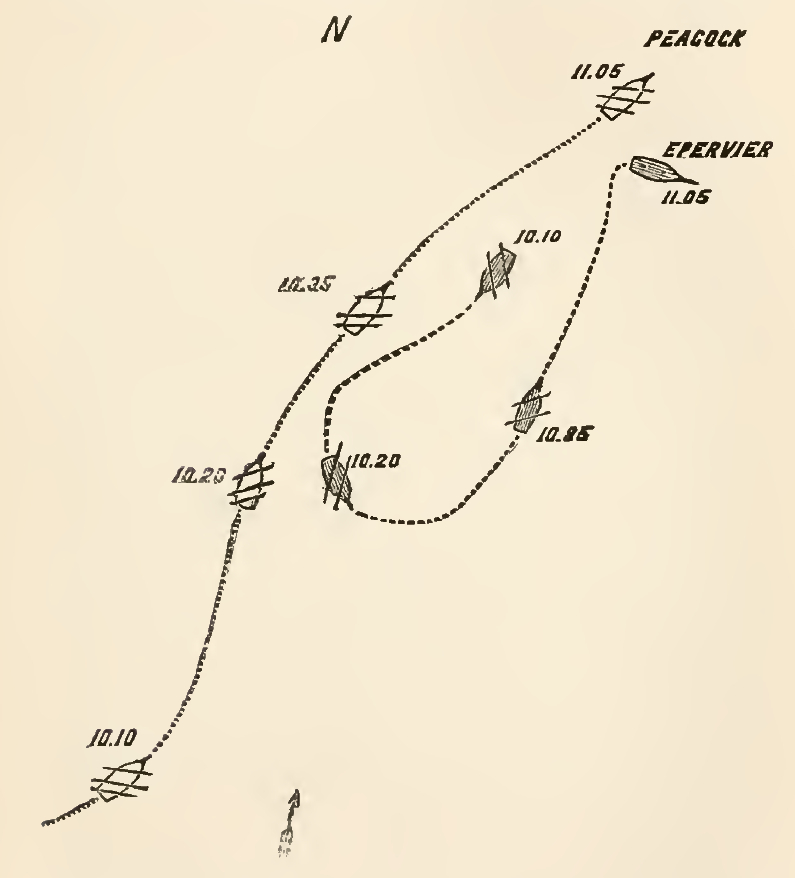

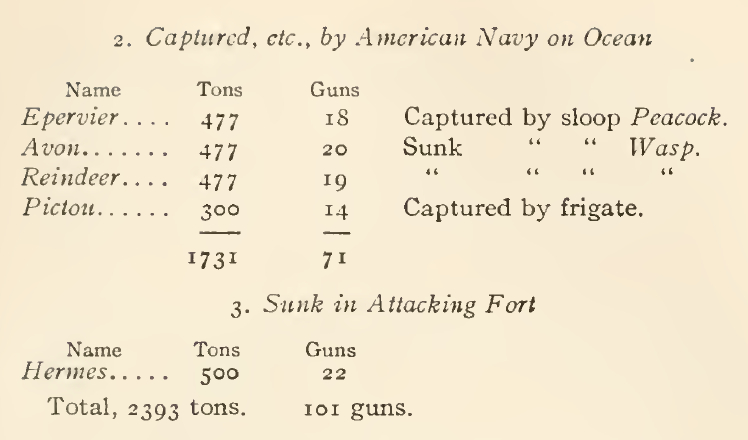

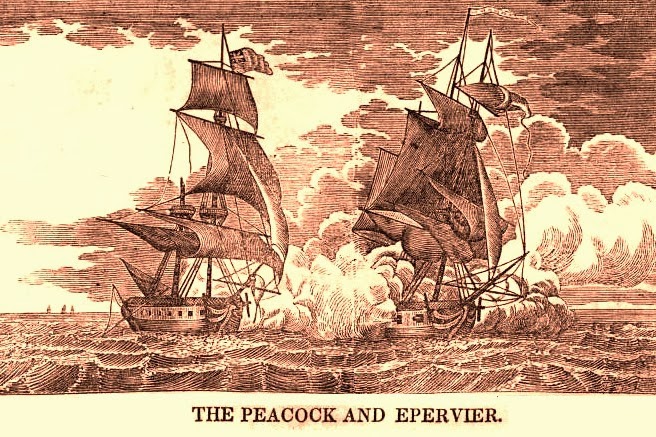

A sister ship to the Frolic, the Peacock,

Captain Lewis Warrington,

sailed from New York on March 12th, and cruised southward; on the

28th of April, at seven in the morning, lat. 17° 47’ N., long. 80°

7’ W., several sail were made to

windward.

These were a small convoy of

merchant-men, bound for the Bermudas, under the protection of the

18-gun brig-sloop Epervier, Captain Wales, 5 days out of

Havana,

and with $118,000 in specie on

board.

The Epervier when discovered was steering north by east,

the wind

being from the eastward; soon afterward the wind veered gradually

round to the southward, and the Epervier hauled up close

on the

port tack, while the convoy made all sail away, and the Peacock

came down with the wind on her starboard quarter. At 10 A.M. the

vessels were within gun-shot, and the Peacock edged away

to get

in a raking broadside, but the Epervier frustrated this by

putting

her helm up until close on her adversary’s bow, when she rounded

to

and fired her starboard guns, receiving in return the starboard

broadside of the Peacock at 10.20 A.M. These first

broadsides took

effect aloft, the brig being partially dismantled, while the

Peacock’s fore-yard was totally disabled by two round shot

in the

starboard quarter, which deprived the ship of the use of her

fore-sail

and fore-top-sail, and compelled her to run large. However, the

Epervier eased

away

when abaft her foe’s beam, and ran off

alongside

of her (using her port guns, while the American still had the

starboard battery engaged) at 10.35. The Peacock’s fire

was now

very hot, and directed chiefly at her adversary’s hull, on which

it told heavily, while she did not suffer at all in return. The

Epervier coming up into the wind, owing somewhat to the

loss of

head-sail, Captain Wales called his crew aft to try boarding, but

they

refused, saying “she’s too heavy for

us,”

and then, at 11.05 the colors were hauled

down.

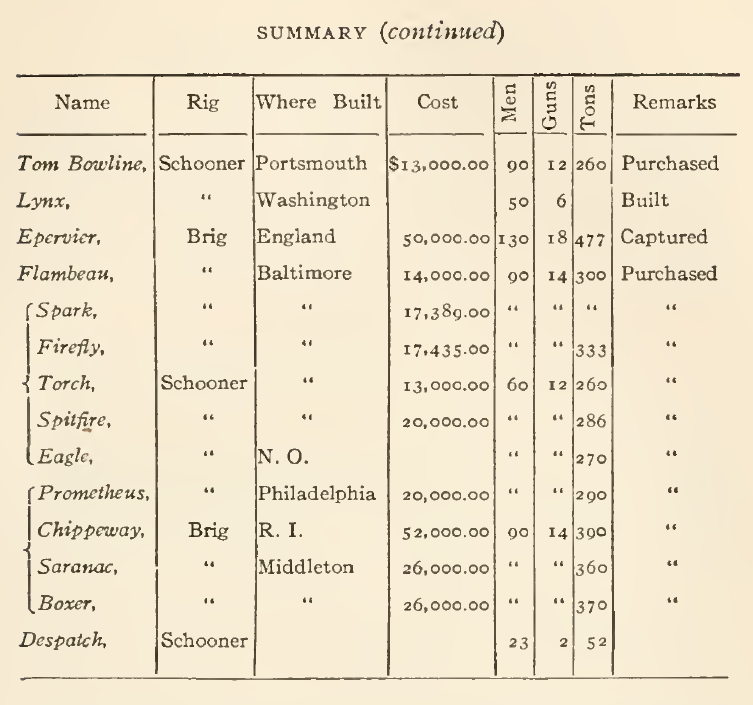

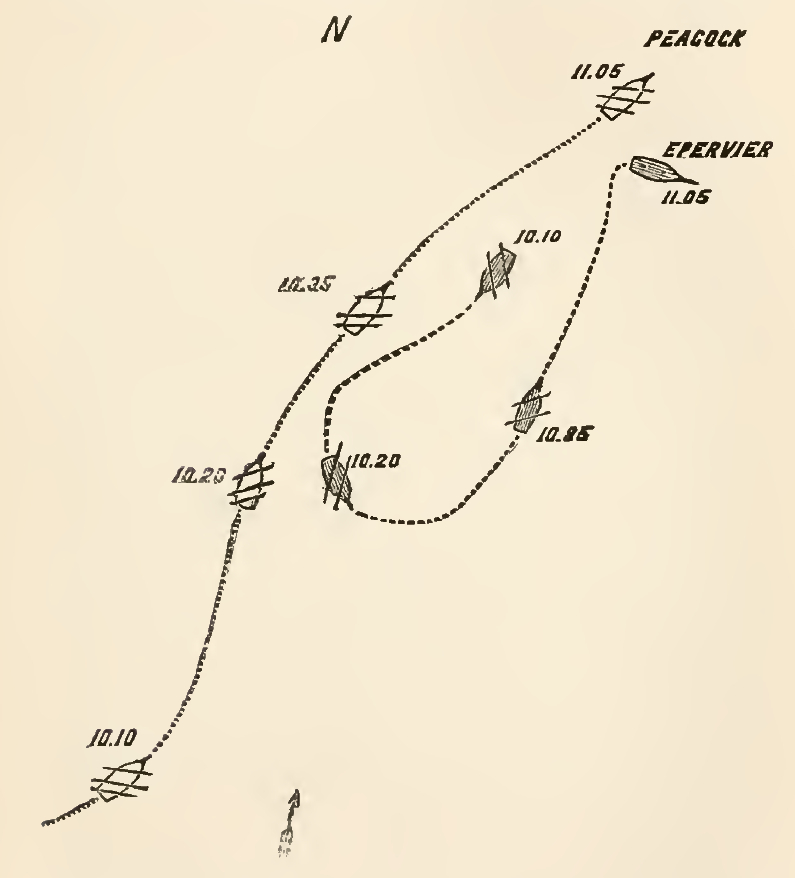

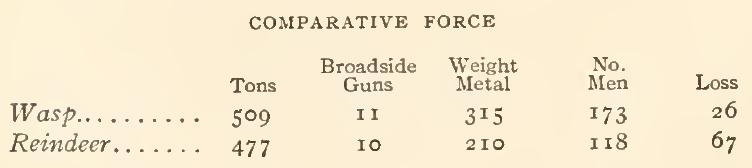

Illustrations of the action between Peacock and Epervier between

10.10 and 11.05.

Except the injury to her fore-yard, the Peacock’s

damages were

confined to the loss of a few top-mast and top-gallant backstays,

and some shot-holes through her sails. Of her crew, consisting,

all

told, of 166 men and

boys,

only two were wounded,

both

slightly. The Epervier, on the other hand, had 45

shot-holes in

her hull, 5 feet of water in her hold, main-top-mast over the

side,

main-mast nearly in two, main-boom shot away, bowsprit wounded

severely, and most of the fore-rigging and stays shot away; and of

her crew of 128 men (according to the list of prisoners given by

Captain Warrington; James says 118, but he is not backed up by any

official report) 9 were killed and mortally wounded, and 14

severely

and slightly wounded. Instead of two long sixes for bow-chasers,

and a shifting carronade, she had two 18-pound carronades

(according

to the American

prize-lists;

Captain Warrington says 32’s). Otherwise she was armed

as usual. She was, like the rest of her kind, very “tubby,” being

as broad as the Peacock, though 10 feet shorter on deck.

Allowing,

as usual, 7 per cent, for short weight of the American shot, we

get the

That is, the relative force being as 12 is to 10,

the relative

execution done was as 12 is to 1, and the Epervier

surrendered

before she had lost a fifth of her crew. The case of the Epervier

closely resembles that of the Argus. In both cases the

officers

behaved finely; in both cases, too, the victorious foe was

heavier,

in about the same proportion, while neither the crew of the Argus,

nor the crew of the Epervier fought with the determined

bravery

displayed by the combatants in almost every other struggle of the

war. But it must be added that the Epervier did worse than

the

Argus, and the Peacock (American) better than the Pelican.

The gunnery of the Epervier was extraordinarily poor; “the

most

disgraceful part of the affair was that our ship was cut to pieces

and the enemy hardly

scratched.”

James states that after the first two or

three

broadsides several carronades became unshipped, and that the

others

were dismounted by the fire of the Peacock; that the men

had not

been exercised at the guns; and, most important of all, that the

crew (which contained “several foreigners,” but was chiefly

British;

as the Argus was chiefly American) was disgracefully bad.

The

Peacock, on the contrary, showed skilful seamanship as well

as

excellent gunnery. In 45 minutes after the fight was over the

fore-yard

had been sent down and fished, the fore-sail set up, and every

thing

in complete order

again;

the prize was got in sailing order by dark, though

great

exertions had to be made to prevent her sinking. Mr. Nicholson,

first

of the Peacock, was put in charge as prize-master. The

next day

the two vessels were abreast of Amelia Island, when two frigates

were

discovered in the north, to leeward. Captain Warrington at once

directed

the prize to proceed to St. Mary’s, while he separated and made

sail

on a wind to the south, intending to draw the frigates after him,

as he was confident that the Peacock, a very fast vessel,

could

outsail

them.

The plan succeeded perfectly, the brig reaching Savannah on the

first

of May, and the ship three days afterward. The Epervier

was purchased

for the U.S. navy, under the same name and rate. The Peacock

sailed

again on

June 4th,

going first northward to the Grand Banks, then to the Azores; then

she stationed herself in the mouth of the Irish Channel, and

afterward

cruised off Cork, the mouth of the Shannon, and the north

of Ireland,

capturing several very valuable prizes and creating great

consternation.

She then changed her station, to elude the numerous vessels that

had been sent after her, and sailed southward, off Cape Ortegal,

Cape Finisterre, and finally among the Barbadoes, reaching New

York,

Oct. 29th. During this cruise she encountered no war vessel

smaller

than a frigate; but captured 14 sail of merchant-men, some

containing

valuable cargoes, and manned by 148 men.

On April 29th, H.M.S. schooner Ballahou, 6,

Lieutenant King, while

cruising off the American coast was captured by the Perry,

privateer,

a much heavier vessel, after an action of 10 minutes’ duration.

The general peace prevailing in Europe allowed the

British to turn

their energies altogether to America; and in no place was this

increased vigor so much felt as in Chesapeake Bay where a great

number of line-of-battle ships, frigates, sloops, and transports

had assembled, in preparation for the assault on Washington and

Baltimore. The defence of these waters was confided to Captain

Joshua

Barney,

with a flotilla of gun-boats. These

consisted

of three or four sloops and schooners, but mainly of barges, which

were often smaller than the ship’s boats that were sent against

them.

These gun-boats were manned by from 20 to 40 men each, and each

carried, according to its size, one or two long 24-, 18-, or

12-pounders.

They were bad craft at best; and, in addition, it is difficult to

believe that they were handled to the fullest advantage.

On June 1st Commodore Barney, with the block sloop Scorpion

and

14 smaller “gun-boats,” chiefly row gallies, passed the mouth of

the Patuxent, and chased the British schooner St. Lawrence

and

seven boats, under Captain Barrie, until they took refuge with the

Dragon, 74, which in turn chased Barney’s flotilla into the

Patuxent,

where she blockaded it in company with the Albion, 74.

They were

afterward joined by the Loire, 38, Narcissus, 32,

and Lasseur,

18, and Commodore Barney moved two miles up St. Leonard’s Creek,

while the frigates and sloop blockaded its mouth. A deadlock now

ensued; the gunboats were afraid to attack the ships, and the

ships’

boats were just as afraid of the gun-boats. On the 8th, 9th, and

11th skirmishes occurred; on each occasion the British boats came

up till they caught sight of Barney’s flotilla, and were promptly

chased off by the latter, which, however, took good care not to

meddle with the larger vessels. Finally, Colonel Wadsworth, of the

artillery, with two long 18-pounders, assisted by the marines,

under

Captain Miller, and a few regulars, offered to cooperate from the

shore while Barney assailed the two frigates with the flotilla. On

the 26th the joint attack took place most successfully; the Loire

and Narcissus were driven off, although not much damaged,

and the

flotilla rowed out in triumph, with a loss of but 4 killed and 7

wounded. But in spite of this small success, which was mainly due

to Colonel Wadsworth, Commodore Barney made no more attempts with

his gun-boats. The bravery and skill which the flotilla men showed

at Bladensburg prove conclusively that their ill success on the

water

was due to the craft they were in, and not to any failing of the

men.

At the same period the French gun-boats were even more

unsuccessful,

but the Danes certainly did very well with theirs.

Barney’s flotilla in the Patuxent remained quiet

until August 22d,

and then was burned when the British advanced on Washington. The

history of this advance, as well as of the unsuccessful one on

Baltimore, concerns less the American than the British navy, and

will be but briefly alluded to here. On August 20th Major-General

Ross and Rear-Admiral Cockburn, with about 5,000 soldiers and

marines,

moved on Washington by land; while a squadron, composed of the

Seahorse, 38, Euryalus, 36, bombs Devastation,

Ætna, and

Meteor, and rocket-ship Erebus, under Captain James

Alexander

Gordon, moved up the Potomac to attack Fort Washington, near

Alexandria; and Sir Peter Parker, in the Menelaus, 38, was

sent

“to create a diversion” above Baltimore. Sir Peter’s “diversion”

turned out most unfortunately for him: for, having landed to

attack

120 Maryland militia, under Colonel Reade, he lost his own life,

while fifty of his followers were placed hors de combat

and the

remainder chased back to the ship by the victors, who had but

three

wounded.

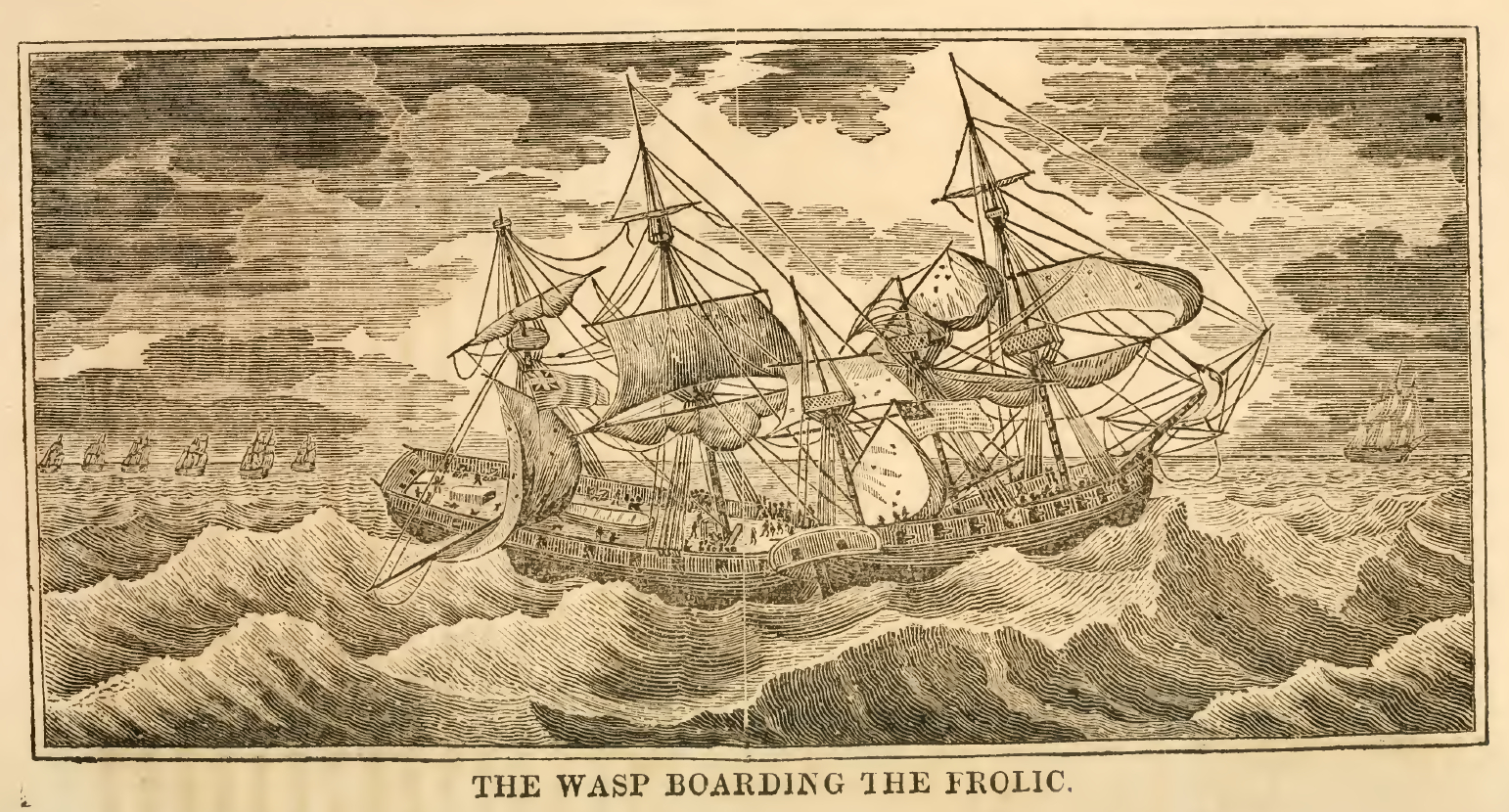

The American army, which was to oppose Ross and

Cockburn, consisted

of some seven thousand militia, who fled so quickly that only

about

1,500 British had time to become engaged. The fight was really

between

these 1,500 British regulars and the American flotilla men. These

consisted of 78 marines, under Captain Miller, and 370 sailors,

some

of whom served under Captain Barney, who had a battery of two 18’s

and three 12’s, while the others were armed with muskets and

pikes,

and acted with the marines. Both sailors and marines did nobly,

inflicting most of the loss the British suffered, which amounted

to 256 men, and in return lost over a hundred of their own men,

including the two captains, who were wounded and captured, with

the

guns.

Ross took Washington and burned the public buildings;

and the panic-struck Americans foolishly burned the Columbia,

44,

and Argus, 18, which were nearly ready for service.

Captain Gordon’s attack on Fort Washington was

conducted with great

skill and success. Fort Washington was abandoned as soon as fired

upon, and the city of Alexandria surrendered upon most humiliating

conditions. Captain Gordon was now joined by the Fairy,

18, Captain

Baker, who brought him orders to return from Vice-Admiral

Cochrane;

and the squadron began to work down the river, which was very

difficult

to navigate. Commodore Rodgers, with some of the crew of the two

44’s, Guerrière and Java, tried to bar their

progress, but had

not sufficient means. On September 1st an attempt was made to

destroy

the Devastation by fire-ships, but it failed; on the 4th

the attempt

was repeated by Commodore Rodgers, with a party of some forty men,

but they were driven off and attacked by the British boats, under

Captain Baker, who in turn was repulsed with the loss of his

second

lieutenant killed, and some twenty-five men killed or wounded. The

squadron also had to pass and silence a battery of light

field-pieces

on the 5th, where they suffered enough to raise their total loss

to

seven killed and thirty-five wounded. Gordon’s inland expedition

was

thus concluded most successfully, at a very trivial cost; it was

a most venturesome feat, reflecting great honor on the captains

and

crews engaged in it.

Baltimore was threatened actively by sea and land

early in September.

On the 13th an indecisive conflict took place between the British

regulars and American militia, in which the former came off with

the honor, and the latter with the profit. The regulars held the

field, losing 350 men, including General Ross; the militia

retreated

in fair order with a loss of but 200. The water attack was also

unsuccessful. At 5 A.M. on the 13th the bomb vessels Meteor,

Ætna, Terror, Volcano, and Devastation,

the rocket-ship

Erebus, and the frigates Severn, Euryalus,

Havannah, and

Hebrus opened on Fort McHenry, some of the other

fortifications

being occasionally fired at. A furious but harmless cannonade was

kept up between the forts and ships until 7 A.M. on the 14th, when

the British fleet and army retired.

I have related these events out of their natural

order because they

really had very little to do with our navy, and yet it is

necessary

to mention them in order to give an idea of the course of events.

The British and American accounts of the various gun-boat attacks

differ widely; but it is very certain that the gun-boats

accomplished

little or nothing of importance. On the other hand, their loss

amounted

to nothing, for many of those that were sunk were afterward

raised,

and the total tonnage of those destroyed would not much exceed

that

of the British barges captured by them from time to time or

destroyed

by the land batteries.

The purchased brig Rattlesnake, 16, had been

cruising in the

Atlantic with a good deal of success; but in lat. 40° N., long.

33° W.,

was chased by a frigate from which Lieutenant Renshaw, the brig’s

commander, managed to escape only by throwing overboard all his

guns except two long nines; and on June 22d he was captured by

the Leander, 50, Captain Sir George Ralph Collier, K. C.

B.

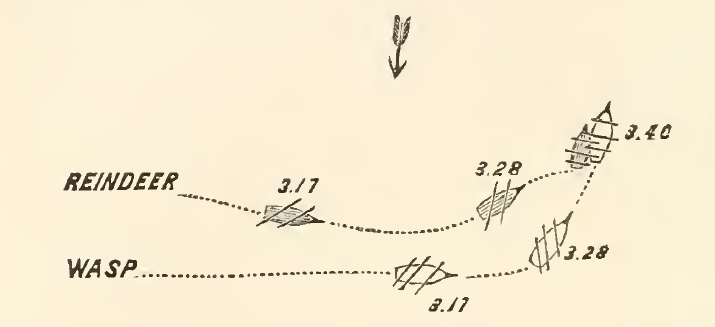

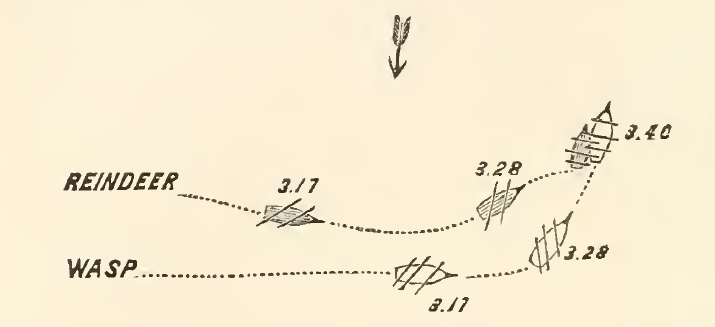

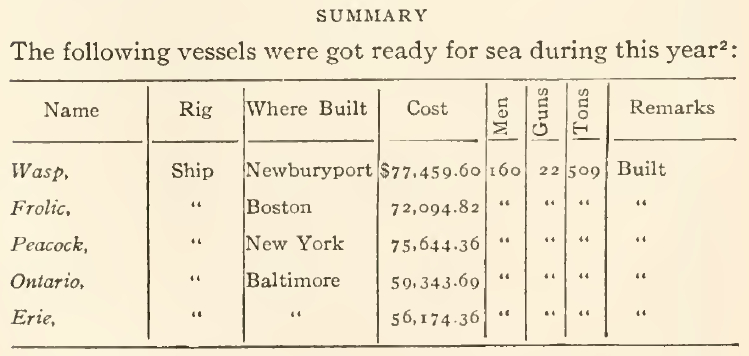

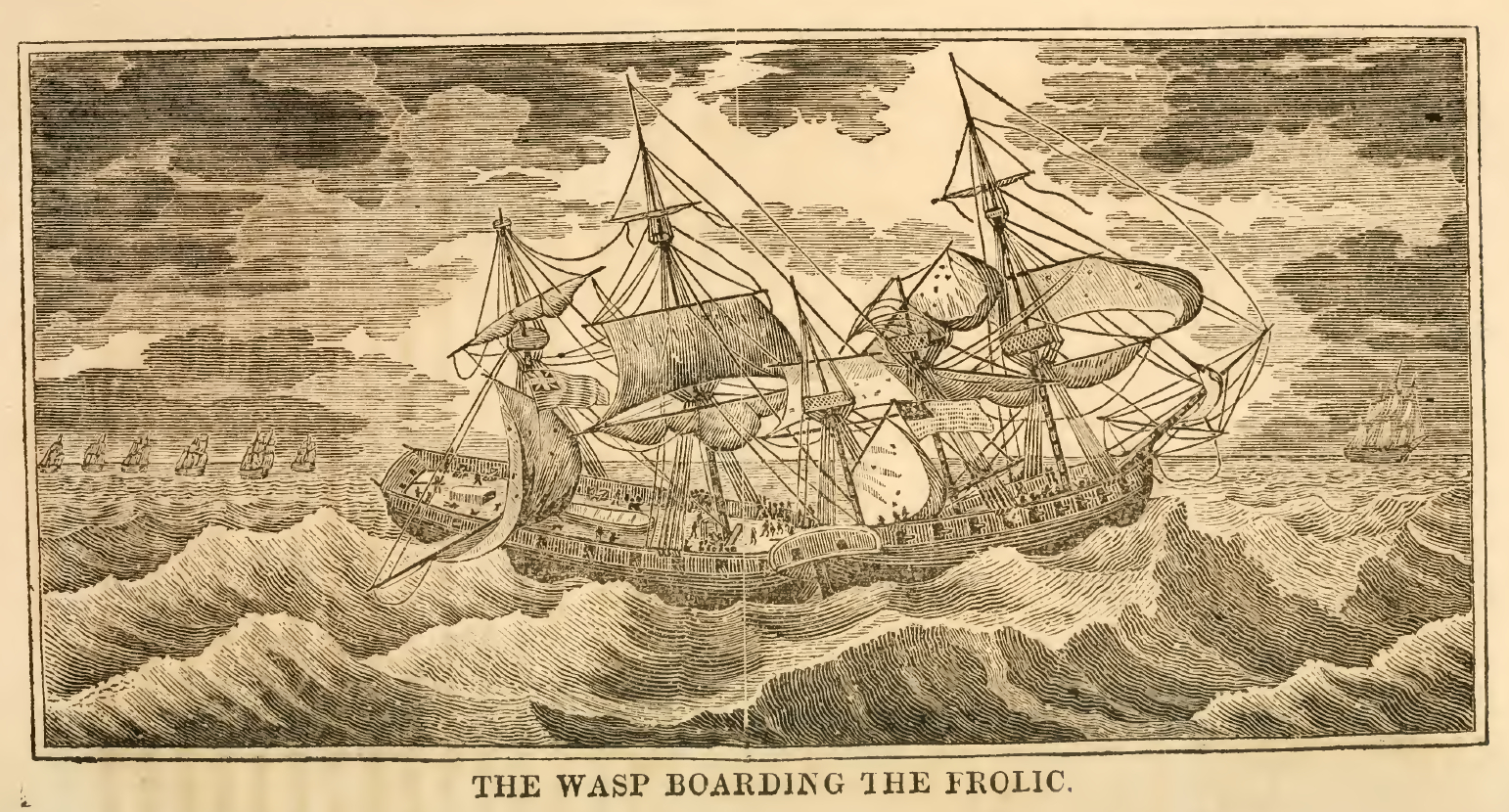

The third of the new sloops to get to sea was the Wasp,

22, Captain

Johnston Blakely, which left Portsmouth on May 1st, with a very

fine

crew of 173 men, almost exclusively New Englanders; there was said

not to have been a single foreign seaman on board. It is, at all

events, certain that during the whole war no vessel was ever

better

manned and commanded than this daring and resolute cruiser. The Wasp

slipped unperceived through the blockading frigates, and ran into

the mouth of the English Channel, right in the thick of the

English

cruisers; here she remained several weeks, burning and scuttling

many ships. Finally, on June 28th, at 4 A.M., in lat. 48° 36’ N.,

long. 11° 15’ W.,

while in chase of two merchant-men, a sail was made on the

weather-beam. This was the British brig-sloop Reindeer,

18,

Captain William

Manners,

with a crew

of 118, as brave men as ever sailed or fought on the narrow seas.

Like the Peacock (British) the Reindeer was only

armed with

24-pounders, and Captain Manners must have known well that he was

to do battle with a foe heavier than himself; but there was no

more

gallant seaman in the whole British navy, fertile as it was in men

who cared but little for odds of size or strength. As the day

broke,

the Reindeer made sail for the Wasp, then lying in

the west-southwest.

The sky was overcast with clouds, and the smoothness

of the sea was

hardly disturbed by the light breeze that blew out of the

northeast.

Captain Blakely hauled up and stood for his antagonist, as the

latter

came slowly down with the wind nearly aft, and so light was the

weather

that the vessels kept almost on even keels. It was not till

quarter

past one that the Wasp’s drum rolled out its loud

challenge as

it beat to quarters, and a few minutes afterward the ship put

about

and stood for the foe, thinking to weather him; but at 1.50 the

brig

also tacked and stood away, each of the cool and skilful captains

being bent on keeping the weather-gage. At half past two the Reindeer

again tacked, and, taking in her stay-sails, stood for the Wasp,

who furled her royals; and, seeing that she would be weathered, at

2.50, put about in her turn and ran off, with the wind a little

forward

the port beam, brailing up the mizzen, while the Reindeer

hoisted

her flying-jib, to close, and gradually came up on the Wasp’s

weather-quarter. At 17 minutes past three, when the vessels were

not sixty yards apart, the British opened the conflict, firing the

shifting 12-pound carronade, loaded with round and grape. To this

the Americans could make no return, and it was again loaded and

fired,

with the utmost deliberation; this was repeated five times, and

would

have been a trying ordeal to a crew less perfectly disciplined

than

the Wasp’s. At 3.26 Captain Blakely, finding his enemy did

not

get on his beam, put his helm a-lee and luffed up, firing his guns

from aft forward as they bore. For ten minutes the ship and the

brig

lay abreast, not twenty yards apart, while the cannonade was

terribly

destructive. The concussion of the explosions almost deadened what

little way the vessels had on, and the smoke hung over them like a

pall. The men worked at the guns with desperate energy, but the

odds

in weight of metal (3 to 2) were too great against the Reindeer,

where both sides played their parts so manfully. Captain Manners

stood at his post, as resolute as ever, though wounded again and

again. A grape-shot passed through both his thighs, bringing him

to the deck; but, maimed and bleeding to death, he sprang to his

feet, cheering on the seamen. The vessels were now almost

touching,

and putting his helm aweather, he ran the Wasp aboard on

her

port

quarter, while the

boarders

gathered forward, to try it with the steel. But the Carolina

captain

had prepared for this with cool confidence; the marines came aft;

close under the bulwarks crouched the boarders, grasping in their

hands the naked cutlasses, while behind them were drawn up the

pikemen.

As the vessels came grinding together the men hacked and thrust at

one another through the open port-holes, while the black smoke

curled

up from between the hulls. Then through the smoke appeared the

grim

faces of the British sea-dogs, and the fighting was bloody enough;

for the stubborn English stood well in the hard hand play. But

those

who escaped the deadly fire of the topmen, escaped only to be

riddled

through by the long Yankee pikes; so, avenged by their own hands,

the foremost of the assailants died, and the others gave back. The

attack was foiled, though the Reindeer’s marines kept

answering

well the American fire. Then the English captain, already mortally

wounded, but with the indomitable courage that nothing but death

could conquer, cheering and rallying his men, himself sprang,

sword

in hand, into the rigging, to lead them on; and they followed him

with a will. At that instant a ball from the Wasp’s

main-top

crashed through his skull, and, still clenching in his right hand

the sword he had shown he could wear so worthily, with his face to

the foe, he fell back on his own deck dead, while above him yet

floated the flag for which he had given his life. No Norse Viking,

slain over shield, ever died better. As the British leader fell

and

his men recoiled, Captain Blakely passed the word to board; with

wild hurrahs the boarders swarmed over the hammock nettings, there

was a moment’s furious struggle, the surviving British were slain

or driven below, and the captain’s clerk, the highest officer

left,

surrendered the brig, at 3.44, just 27 minutes after the Reindeer

had fired the first gun, and just 18 after the Wasp had

responded.

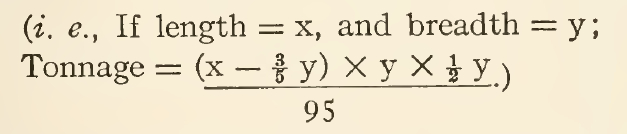

Capture of the Reindeer by the Wasp

Both ships had suffered severely in the short

struggle; but, as with

the Shannon and Chesapeake, the injuries were much less

severe

aloft than in the hulls. All the spars were in their places. The

Wasp’s hull had received 6 round, and many grape; a

24-pound shot

had passed through the foremast; and of her crew of 173, 11 were

killed or mortally wounded, and 15 wounded severely or slightly.

The Reindeer was completely cut to pieces in a line with

her ports;

her upper works, boats, and spare spars being one entire wreck. Of

her crew of 118 men, 33 were killed outright or died later, and 34

were wounded, nearly all severely.

It is thus seen that the Reindeer

fought at a greater disadvantage

than any other of the various British sloops that were captured in

single action during the war; and yet she made a better fight than

any of them (though the Frolic, and the Frolic

only, was defended

with the same desperate courage); a pretty sure proof that heavy

metal is not the only factor to be considered in accounting for

the

American victories. “It is difficult to say which vessel behaved

the

best in this short but gallant

combat.”

I doubt if the war produced two better single-ship commanders than

Captain Blakely and Captain Manners; and an equal meed of praise

attaches to both crews. The British could rightly say that they

yielded purely to heavy odds in men and metal; and the Americans,

that the difference in execution was fully proportioned to the

difference in force. It is difficult to know which to admire most,

the wary skill with which each captain manoeuvred before the

fight,

the perfect training and discipline that their crews showed, the

decision and promptitude with which Captain Manners tried to

retrieve

the day by boarding, and the desperate bravery with which the

attempt

was made; or the readiness with which Captain Blakely made his

preparations, and the cool courage with which the assault was

foiled.

All people of the English stock, no matter on which side of the

Atlantic they live, if they have any pride in the many feats of

fierce prowess done by the men of their blood and race, should

never

forget this fight; although we cannot but feel grieved to find

that

such men — men of one race and one speech; brothers in blood, as

well

as in bravery — should ever have had to turn their weapons against

one another.

The day after the conflict the prize’s foremast went

by the board,

and, as she was much damaged by shot, Captain Blakely burned her,

put a portion of his wounded prisoners on board a neutral, and

with

the remainder proceeded to France, reaching l’Orient on the 8th

day

of July.

On July 4th Sailing-master Percival and 30

volunteers of the New York

flotilla

concealed

themselves on board a fishing-smack, and carried by surprise the

Eagle tender, which contained a 32-pound howitzer and 14

men, 4

of whom were wounded.

On July 12th, while off the west coast of South

Africa, the American

brig Syren was captured after a chase of 11 hours by the Medway,

74, Captain Brine. The chase was to windward during the whole time,

and made every effort to escape, throwing overboard all her boats,

anchors, cables, and spare

spars.

Her commander, Captain

Parker,

had died, and she was in charge of Lieutenant N. J. Nicholson. By a

curious

coincidence, on the same day, July 12th, H. M. cutter Landrail,

4

of 20 men, Lieutenant Lancaster, was captured by the

American

privateer Syren, a schooner mounting 1 long heavy gun,

with a crew

of 70 men; the Landrail had 7, and the Syren 3 men

wounded.

On July 14th Gun-boat No. 88, Sailing-master George

Clement, captured

after a short skirmish the tender of the Tenedos frigate,

with

her second lieutenant, 2 midshipmen, and 10

seamen.

The Wasp stayed in l’Orient till she was

thoroughly refitted, and

had filled, in part, the gaps in her crew, from the American

privateers

in port. On Aug. 27th, Captain Blakely sailed again, making two

prizes

during the next three days. On Sept. 1st she came up to a convoy

of

10 sail under the protection of the Armada, 74, all bound

for

Gibraltar; the swift cruiser hovered round the merchant-men like

a hawk, and though chased off again and again by the

line-of-battle

ship, always returned the instant the pursuit stopped, and finally

actually succeeded in cutting off and capturing one ship, laden

with

iron and brass cannon, muskets, and other military stores of great

value. At half past six on the evening of the same day, in lat.

47°

30’ N., long. 11° W., while running almost free, four sail, two on

the starboard bow, and two on the port, rather more to leeward,

were

made

out.

Captain Blakely at once made sail for the most weatherly of the four

ships in sight, though well aware that more than one of them might

prove to be hostile cruisers, and they were all of unknown force.

But the determined Carolinian was not one to be troubled by such

considerations. He probably had several men less under his command

than in the former action, but had profited by his experience with

the Reindeer in one point, having taken aboard her

12-pounder

boat carronade, of whose efficacy he had had very practical proof.

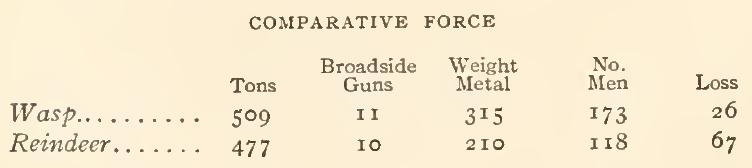

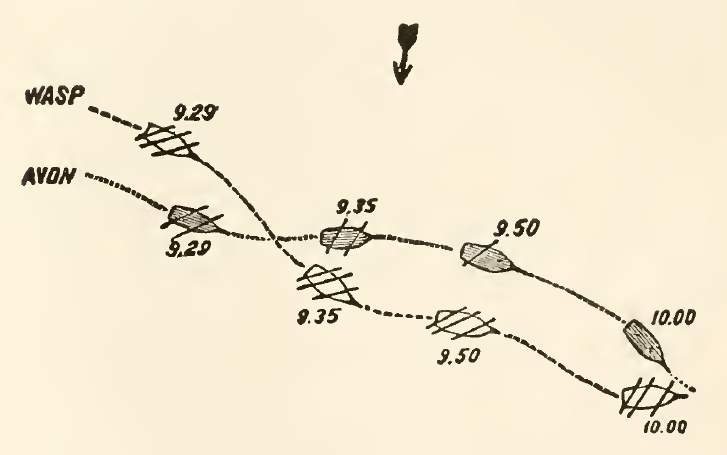

The chase, the British brig-sloop Avon, 18,

Captain the Honorable

James

Arbuthnot,

was steering almost

southwest; the wind, which was blowing fresh from the southeast,

being a little abaft the port beam. At 7.00 the Avon began

making

night signals with the lanterns, but the Wasp,

disregarding these,

came steadily on; at 8.38 the Avon fired a shot from her

stern-chaser,

and shortly afterward another from one

of her lee or starboard guns. At 20 minutes past 9, the Wasp

was

on the port or weather-quarter of the Avon, and the

vessels interchanged

several hails; one of the American officers then came forward on

the forecastle and ordered the brig to heave to, which the latter

declined doing, and set her port foretop-mast studding sail. The

Wasp then, at 9.29, fired the 12-pound carronade into her,

to which

the Avon responded with her stern-chaser and the aftermost

port

guns. Captain Blakely then put his helm up, for fear his adversary

would try to escape, and ran to leeward of her, and then ranged up

alongside, having poured a broadside into her quarter. A close and

furious engagement began, at such short range that the only one of

the Wasp’s crew who was wounded, was hit by a wad; four

round shot

struck her hull, killing two men, and she suffered a good deal in

her rigging. The men on board did not know the name of their

antagonist;

but they could see through the smoke and the gloom of the night,

as her black hull surged through the water, that she was a large

brig; and aloft, against the sky, the sailors could be discerned,

clustering in the

tops.

In

spite of the darkness the Wasp’s fire was directed with

deadly

precision; the Avon’s gaff was shot away at almost the

first