Thomas Ruys Smith.

“Mark Twain on Mardi Gras.”

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 2013

© Thomas Ruys Smith.

Used by permission.

All rights reserved.

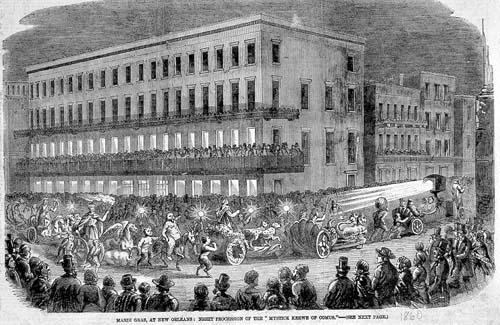

London Illustrated News, May 8 1858, via)

On March 8 1859, a 23 year old trainee steamboat pilot named Samuel Clemens, a month away from getting his full pilot’s license, arrived in New Orleans after a week’s voyage down the Mississippi from St. Louis. But when the young man who would soon become Mark Twain stepped off the Aleck Scott, looking forward to some rest and recuperation in the South’s premier city, he was unprepared for the spectacle that met his eyes: he had alighted in the middle of Mardi Gras.

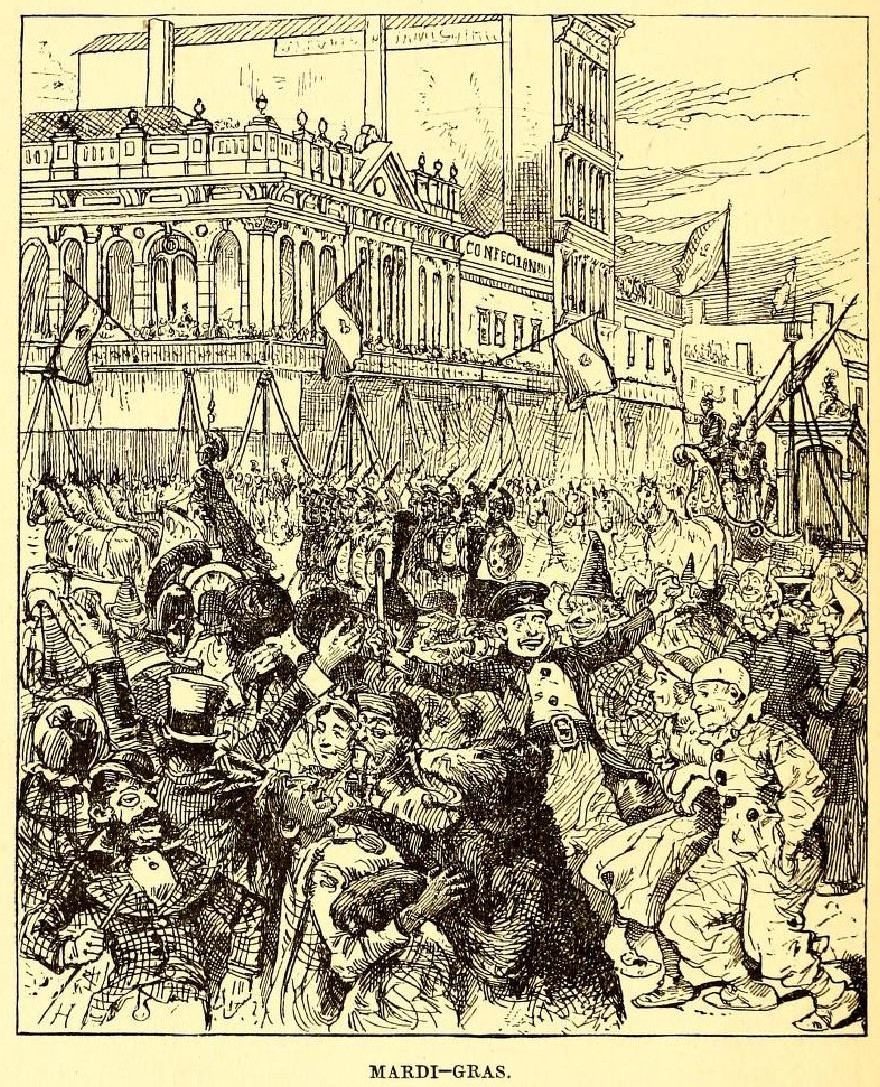

Twain’s vivid and enthusiastic account of his experiences survives in a long (and rather consciously literary) letter that he wrote to his sister Pamela the next day, available in full at the Mark Twain Project’s database of Twain’s correspondence. The whole thing's worth your time. “I think that I may say,” he declared by way of opening, “that an American has not seen the United States until he has seen Mardi-Gras in New Orleans.” He was astonished by all the costumed revelers he encountered — “I saw a hundred men, women and children in fine, fancy, splendid, ugly, coarse, ridiculous, grotesque, laughable costumes” — though singled out one group for particular attention: “The ‘free-and-easy’ women turned out en masse — and their costumes and actions were very trying to modest eyes.” But even these delights soon seemed “insignificant” in comparison to the sights he witnessed that evening.

The Mistick Krewe of Comus, a secret organization, had successfully reinvigorated the city’s Mardi Gras celebrations in 1857 by introducing a torch-lit, night time parade (essentially, the foundations of modern carnival). Word had spread far and wide about this extraordinary spectacle — The Illustrated London News published an illustration of the event in 1858 (above), and travelers from outside of town had already begun to make their way to New Orleans in expectation of the day. In 1859, Comus based its lavish entertainments around the theme of “The English Holidays” — and Sam Clemens was one of the thousands of spectators who (after much “impatience and anxiety”) was transported by what he saw. After a long and detailed description of the parade — “I don’t remember half” — he concluded his letter to Pamela appreciatively, “Certainly New Orleans seldom does things by halves.”

A quarter of a century later, in April 1882, Mark Twain was back in New Orleans. Now well established as a popular writer, Twain was travelling along the river again to gather material together for Life on the Mississippi (1883). Though this time he arrived in town too late to experience the annual festivities, inevitably the memory of Mardi Gras in 1859 came back to him as “a startling and wonderful sort of show.” But the passage of time meant that Twain’s account of carnival and what it represented had shifted considerably, and was far more complicated than the enjoyment he expressed as a young man.

The contrast tells us a lot about the journey that Twain had undergone in the decades that took him from steamboat pilot to author. Having witnessed (from afar) the Civil War and Reconstruction, having declared himself an enemy of “romance” in all its forms, and having established himself as an adoptive New Englander, Twain was no longer able to give himself over to what he now saw as a distinctly Southern, rather than American, spectacle. Mardi Gras, he asserted, “could hardly exist in the practical North.” And he felt that its “girly-girly romance” would “kill it […] in London”, where “Punch, and the press universal, would fall upon it and make merciless fun of it.” Indeed, Mardi Gras had become for Twain a perfect symbol of everything that he found wrong with the dominant culture of the American South — in his words, “sillinesses and emptinesses, sham grandeurs, sham gauds, and sham chivalries of a brainless and worthless long-vanished society.” And who did Twain think was to blame, at root, for the “love” of these kinds of “dreams and phantoms” exemplified by Mardi Gras? Why, none other than the works of Walter Scott — or, as Twain would have it, “the Sir Walter disease.” It would, I feel, be nice to know what Scott what have made of a Fat Tuesday in New Orleans.

Not that Twain found nothing to love in his return to the city. His sometime-friend the New Orleans author George Washington Cable took him on tours of the French Quarter that he found “a vivid pleasure.” But nothing seems to have pleased him as much as his attendance at a “mule race”: “I enjoyed it more than I remember having enjoyed any other animal race I ever saw.” A silliness, perhaps — but, at least as far as Twain was concerned, certainly one with fewer “sham grandeurs” than a Mardi Gras parade.

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Smith, Thomas Ruys. “Mark Twain on Mardi Gras.” American Scrapbook. 12 Feb. 2013. Web. 24 Nov. 2020. <http:// americanscrapbook. blogspot.com/ 2013/02/ mark-twain-on-mardi-gras.html>. © Thomas Ruys Smith. Used by permission. All rights reserved.