What more formidable combatant than one’s own stubbornness, turned to

confront him, in his children?

The initial munificence of chartering one of the great Mississippi

steamboats for the first stage of the journey set the pace for the

entire occasion. Host and hostess met their guests at the river landing

with carriages and cane wagons gaily bedecked with evergreens, mosses,

and dogwood branches in flower, and a merry drive through several miles

of forest brought them to the banks of the bayou, where a line of

rowboats awaited them.

The negro boatmen, two to man each skiff, wearing jumpers of the Harvard

crimson, stood uncovered in line at the bayou’s edge, and as the party

alighted, they served black coffee from a fire in the open.

The negro with a cup of coffee his own hue and clear as wine is ever an

ubiquitous combination in the Louisiana lowlands. He bobs up so

unexpectedly in strange places balancing his tiny tray upon his hand,

that a guest soon begins to look for him almost anywhere after an

interval of about three dry hours, and with a fair chance of not being

disappointed.

Before this intangible emotion had time to crystallize into fear,

however, each pilot who manipulated the rudder astern had drawn from

under his seat a great torch of pine and set it ablaze.

Under festoons of gray Spanish moss, often swung so low that heads and

torches were obliged to defer to them, and between flowering banks which

seemed sometimes almost to meet in the floating growths which the

dividing bows of the boats plowed under, the little crafts sped lightly

along.

Occasionally a heavy plunging thing would strike the water with a thud,

so near a boat that a girlish shriek would pierce the wood, spending

itself in laughter. A lazy alligator, sleepily enjoying a lily-pool,

might have been startled by the light, or a line of turtles, clinging

like knots to a log over the water, suddenly let go.

Streaks of darting incandescence marked the eccentric flights of a

million fireflies flecking the deep wood whose darkness they failed to

dispel; and once or twice two reflected lights a few inches apart,

suggesting a deer in hiding, increased the tremulous interest of this

super-safe but most exciting journey.

But presently, before impressions had time to repeat themselves, and

objects dimly discerned to become familiar, a voice from the leading

boat started a song.

It was a great voice, vibrant, strong, and soft as velvet, and when

presently it was augmented by another, insidiously thrown in, then

another in the next boat, until all the untutored Harvard oarsmen were

bravely singing and the dipping oars fell into the easy measure, all

sense of fear or place was lost in the great uplift of the rhythmic

melody.

At special turns through the wood ringing echoes gave back the strains.

A mocking-bird, excited by the unusual noise, poured forth a rival

disputatious song, and an owl hooted, and something barked like a fox;

but it was the great singing of the men which filled the wood.

Common songs of the plantation followed one another — songs of love, of

night and bats, of devils and hobgoblins, selected according to the will

of the leader — all excepting the opening song, which, although of the

same repertoire, was “by request,” and for obvious reasons.

Then, changing to a solemn, staccato measure, it went on:

Ole Marse Adam! Ole Marse Adam!

Et de lady’s apple up an’ give her all de blame.

Greedy-gut, greedy-gut, whar is yo’ shame?

Ole Marse Adam, man, whar is yo’ shame?

Ole Marse Adam! Ole Marse Adam!

Caught de apple in ’is neck an’ made it

mighty so’e,

An’ so we po’ gran’chillen has to swaller

roun’ de co’e.

Ole Marse Adam, man, whar is yo’ shame?

Ole Marse Adam! Ole Marse Adam!

Praised de lady’s attitudes an’ compliment

’er figur’ —

Didn’t have de principle of any decent

nigger.

Ole Marse Adam, man, whar is yo’ shame?

It was a long pull of five miles up the winding stream, but the spirit

of jollity had dispelled all sense of time, and when at last the

foremost boat, doubling a jutting clump of willows, came suddenly into

the open at the foot of the hill, the startling presentment of the white

house illuminated with festoons of Chinese lanterns, which extended

across its entire width and down to the landing, was like a dream of

fairyland.

It was indeed a smiling welcome, and exclamations of delight announced

the passage of the boats in turn as they rounded the willow bend.

The firing of a single cannon, with a simultaneous display of

fireworks, and music by the plantation band, celebrated the landing of

the last boat.

Servants in the simple old-fashioned dress — checked homespun with white

accessories, to which were added for the occasion, great rosettes of

crimson worn upon the breast — took care of the party at the landing,

bringing up the rear with hand-luggage, which they playfully balanced

upon their heads or shifted with fancy steps.

The old-time supper — of the sort which made the mahogany groan — was

served on the broad back “gallery,” while the plantation folk danced in

the clearing beyond, a voice from the basement floor calling out the

figures.

This was a great sight.

Left here to their own devices as to dress, the negroes made so dazzling

a display that, no matter how madly they danced, they could scarcely

answer the challenge of their own riotous color schemes.

Single dancers followed; then “ladyes and gentiles” in pairs, taking

fantastic steps which would shame a modern dancing-master without once

awakening a blush in a maiden’s cheek.

The dancing was refined, even dainty, to-night, the favorite achievement

of the women being the mincing step taken so rapidly as to simulate

suspension of effort, which set the dancers spinning like so many tops,

although there was much languid posing, with exchange of salutations and

curtsying galore.

Yet not a twirl of fan or dainty lift of flounce — to grace a figure or

display a dexterous foot — but expressed a primitive idea of high

etiquette.

The “fragments” left over from the banquet of the upper porch — many of

them great unbroken dishes, meats, game, and sweets — provided a great

banquet for the dancers below, and the gay late feasters furnished

entertainment, fresh and straight from life, to the company above, for

whose benefit many of their most daring sallies were evidently thrown

out — and who, after their recent experiences, were pleased to be so

restfully entertained.

Toasts, drunk in ginger-pop and persimmon beer innocent of guile, were

offered after grace at the beginning of the supper, the toaster stepping

out into the yard and bowing to the gallery while he raised his glass

or, literally, his tin cup — the passage of the master’s bottle among the

men, later in the evening, being a distinct feature.

The first toast was offered to the ladies — “Mistus an’ Company-ladies”;

and the next, following a suggestion of the first table, where the host

had been much honored, was worded about in this wise:

“We drinks to de health, an’ wealth, an’ de long life of de leadin’

gentleman o’ Brake Island, who done put ’isself to so much pains an’

money to give dis party. But to make de toast accordin’ to manners, so

hit’ll fit de gentleman’s visitors long wid hisself, I say let’s drink

to who but ‘Ole Marse Adam!’”

It is easy to start a laugh when a festive crowd is primed for fun, and

this toast, respectfully submitted with a low bow by an ancient and

privileged veteran of the rosined bow, was met with screams of delight.

V

ARESOURCEFUL

little island it was that could provide entertainment for

a party of society folk for nearly a fortnight with never a repetition

to pall or to weary.

The men, equipped for hunting or fishing, and accompanied by several

negro men-servants with a supplementary larder on wheels, — which is to

say, a wagon-load of bread, butter, coffee, condiments, and wines, with

cooking utensils, — left the house early every morning, before the ladies

were up.

They discussed engineering schemes over their fishing-poles and

game-bags, explored the fastnesses of the brake, eavesdropped for the

ultimate secret of the woods, and plumbed for the bayou’s heart,

bringing from them all sundry tangible witnesses of geologic or other

conditions of scientific values.

Most of these “witnesses,” however, it must be confessed, were

immediately available for spit or grill, while many went — so bountiful

was the supply — to friends in the city with the cards of their captors.

There are champagne bottles even yet along the marshes of Brake Island,

bottles whose bellies are as full of suggestion as of mud, and whose

tongueless mouths fairly whistle as if to recount the canards which

enlivened the swampland in those halcyon days of youth and hope and

inexperience.

Until the dressing-hour, in the early afternoons which they frankly

called the evening, the young women coddled their bloom in linen cambric

night-gowns, mostly, reading light romance and verse, which they quoted

freely under the challenge of the masculine presence.

Or they told amazing mammy-tales of voudoo-land and the ghost-country

for the amused delectation of their gentle hostess, who felt herself

warmed and cheered in the sunshine of these Southern temperaments. It

seemed all a part of the poetry and grace of a novel and romantic life.

Here were a dozen young women, pretty and care-free as flowers, any one

of whom could throw herself across the foot of a bed and snatch a

superfluous “beauty-sleep” in the midst of all manner of jollity and

laughter.

Most of them spoke several languages and as many dialects, frequently

passing from one to another in a single sentence for easy subtlety or

color, and with distinct gain in the direction of music.

Possibly they knew somewhat of the grammar of but a single tongue beside

their own, their fluency being more of a traditional inheritance than an

acquisition. Such is the mellow equipment of many of our richest

speakers.

Not one but could pull to pieces her Olympe bonnet and nimbly retrim it

with pins, to match her face or fancy — or dance a Highland fling in her

’broidered nightie, or sing —

How they all did sing — and play! Several were accomplished musicians.

One knew the Latin names of much of the flora of the island, and found

time and small coins sufficient to interest a colony of eager

pickaninnies to gather specimens for her “herbarium.”

Without ever having prepared a meal, they could even cook, as they had

soon amply proven by the heaping confections which were always in

evidence at the man-hour — bon-bons, kisses, pralines, what not — all

fragrant with mint, orange-flower, rose-leaf, or violet, or heavy with

pecans or cocoanut.

In the afternoon, when the men came home, they frequently engaged in

contests of skill — in rowing or archery or croquet; or, following

nature’s manifold suggestions, they drifted in couples, paddling

indolently among the floating lily-pads on the bayou, or reclining among

the vines in the summer-houses, where they sipped iced orange syrup or

claret sangaree, either one a safe lubricator, by mild inspiration or

suggestion, of the tongue of young love, which is apt to become tied at

the moment of most need.

“Sipped iced orange syrup or claret sangaree”

With the poems of Moore to reinforce him with easy grace of words, a

broad-shouldered fellow would naïvely declare himself a peri, standing

disconsolate at the gate of his lady’s heart, while she quoted Fanny

Fern for her defense, or, if she were passing intellectual and of a

broader culture, she would give him invitation in form of rebuff from

“The Lady of the Lake,” or a scathing line from Shakspere. Of course,

all the young people knew their Shakspere — more or less.

They had their fortunes told in a half-dozen fashions, by withered old

crones whose dim eyes, discerning life’s secrets held lightly in

supension, mated them recklessly on suspicion.

Visiting the colored churches, they attended some of the novel services

of the plantation, as, for instance, a certain baptismal wedding, which

is to say a combined ceremony, which was in this case performed quite

regularly and decorously in the interest of a coal-black piccaninny,

artlessly named Lily Blanche in honor of two of the young ladies present

whom the bride-mother had seen but once out driving, but whose gowns of

flowered organdy, lace parasols, and leghorn hats had stirred her sense

of beauty and virtue to action.

Although there was much amusement over this incongruous function, the

absence of any sense of embarrassment in witnessing so delicate a

ceremony — one which in another setting would easily have become

indelicate — was no doubt an unconscious tribute to the primitive

simplicity of the contracting parties.

And always there were revival meetings to which they might go and hear

dramatic recitals of marvelous personal “experiences,” full of

imagery, — travels in heaven or hell, — with always the resounding human

note which ever prevails in vital reach for truth. Through it all they

discerned the cry which finds the heart of a listener and brings him

into indissoluble relation with his brother man, no matter how great the

darkness out of which the note may come. It is universal.

The call is in every heart, uttered or unexpressed, and one day it will

pierce the heavens, finding the blue for him who sends it forth, and for

the listener as well if his heart be attuned.

Let who will go and sit through one of these services, and if he does

not come away subdued and silent, more tender at heart, and, if need be,

stronger of hand to clasp and to lift, perhaps — well, perhaps his mind

is open only to the pictorial and the spectacular.

There is no telling how long the house-party would have remained in

Paradise but for the inexorable calendar which warned certain of its

members that they would be expected to answer the royal summons of Comus

at the approaching carnival; and of course the important fact that

certain bills from the legislature affecting the public weal were

awaiting the governor’s signature.

A surprising number of marriages followed this visit, seeming to confirm

a report of an absurd number of engagements made on the island.

There is a certain old black woman living yet “down by the old basin” in

French New Orleans, a toothless old crone who, by the irony of

circumstance, is familiarly known as “Ol’ Mammy Molar,” who “remembers”

many things of this time and occasion, which she glibly calls “de

silveringineer party,” and who likes nothing better than an audience.

If she is believed, this much too literal account of a far-away time is

most meager and unfaithful, for she does most strenuously insist that,

for instance, there was served at the servants’ table on that first

night?

But let her have her way of it for a moment — just a single breath:

“Why, honey,” she closes her eyes as she begins, the better to see

memory behind them. “Why, honey, de champagne wine was passed aroun’ to

de hands all dat indurin’ infair in water-buckets, an’ dipped out in

gou’d dippers-full, bilin’ over so fast an’ fizzin’ so it’d tickle yo’

mouf to drink it. An’ Marse Harol’ Le Duc, he stood on a pianner-stool

on de back gallery an’ th’owed out gol’ dollars by de hatful for any of

us niggers to pick up; an’ de guv’ner, ol’ Marse Abe Lincolm, he fired

off sky-rockers an’ read out freedom papers.

“An’ mids’ all de dance an’ reveltry, a bolt o’ thunder fell like a

cannon-ball outen a clair sky, an’ we looked up an’ lo an’ beholst, here

was a vision of a big hand writin’ on de sky, an’ a voice say, ‘Eat up

de balance ef anything is found wantin’!’ an’ wid dat, dey plunged in

like a herd o’ swine boun’ for de sea, an’ dey devoured de fragmints an’

popped mo’ corks, an’ dipped out mo’ champagne wine, an’ de mo’ dey

dipped out champagne wine, de mo’ dey ’d dance. An’ de mo’ dey ’d dance,

de mo’ de wine would flow.”

Possibly the old woman’s obvious confusion of thought has some

explanation in the fact of the presence of the governor of the State,

who, introduced as a high dignitary, did make a little speech late that

night, thanking the colored people in terms of compliment for their

dancing; and any impression made here was so quickly overlaid by the

deeper experiences of the war that a blending can easily be explained.

There was a shower of coins — “picayunes” only — thrown during the evening

by the master, a feature of the dance being to recover as many of them

as possible without breaking step. So the old woman’s memory is not so

far afield, although as a historian she might need a little editing. But

such even as this is much of the so-called “history” which, bound in

calf, dishonors the world’s libraries to-day.

It is so easy, seeing cobwebs upon a record, — cobwebs which may not be

quite construed as alphabet, — to interpret them as hieroglyphics of

import, instead of simply brushing them away, or relegating them, where

they belong, to the dusky domain of the myth out of which we may expect

only weird suggestion, as from the mold of pressed rosemary, typifying

remembrance dead.

The house-party, which in this poor retrospect seems to have devoted

itself almost wholly to pleasure, was nevertheless followed by immediate

work upon the project in behalf of which it was planned.

With this main motive was also the ulterior and most proper one in

Harold’s mind of introducing his wife in so intimate a fashion to some

of the important members of society, who would date life-friendships

from the pleasant occasion of helping him to open his own door to them.

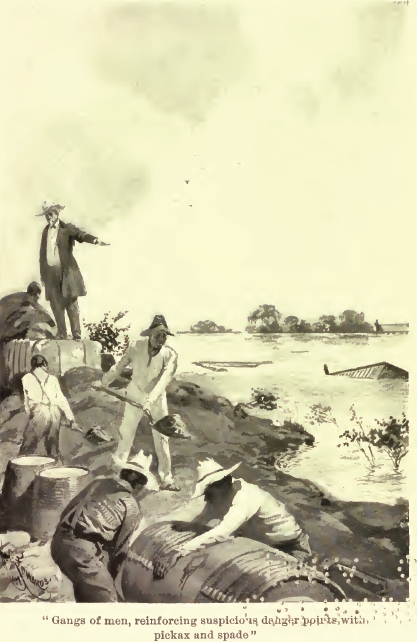

Some thousands of dollars went into the quicksands of the marshes before

the foundations were laid for the arch of a proposed great bridge,

beneath which his boats should sail to their landing. With the arrogant

bravado of an impulsive boy challenged to action, he began his arch

first. Its announcement of independence and munificence would express

the position he had taken. Sometimes it is well to put up a bold front,

even if one needs to work backward from it.

Harold moved fast — but the gods of war moved faster!

Scarcely had a single column of solid masonry risen above the palmetto

swamp when Fort Sumter’s guns sounded. The smell of gunpowder penetrated

the fastnesses of the brake, and yet, though his nostrils quivered like

those of an impetuous war-horse, the master held himself in rein with

the thought of her who would be cruelly alone without him. And he said

to himself, while he reared his arch: “Two out of three are enough! I

have taken their terror island for my portion. They may have garlands

upon my bridge — when they come sailing up my canal as heroes!”

But the next whiff from the battleground stopped work on the arch. The

brothers had fallen side by side.

“The brave, unthinking fellow, after embracing his

beloved,

dashed to the front”

Madly seizing both the recovered swords, declaring he would “fight as

three,” the brave, unthinking fellow, after embracing his beloved, put

one of her hands in Hannah’s and the other in Israel’s, and, commending

them to God by a speechless lift of his dark eyes, mounted his horse and

dashed, as one afraid to look back, to the front.

VI

EVERY ONE

knows the story of “poor Harold Le Duc” — how, captured,

wounded, he lay for more than a year on the edge of insanity in a

Federal hospital. Every one knows of the birth of his child on the

lonely island, with only black hands to receive and tend it, and how the

waiting mother, guarded by the faithful two, and loved by the three

hundred loyal slaves who prayed for her life, finally passed out of it

on the very day of days for which she had planned a great Christmas

banquet for them in honor of their master’s triumphant return.

The story is threadbare. Everyone knows how it happened that “the old

people,” Colonel and Madame Le Duc, having taken flight upon report of a

battle, following their last son, had crossed the lines and been unable

from that day to communicate with the island; of the season of the

snake-plague in the heart of the brake, when rattlers and copperheads,

spreading-adders, moccasins, and conger-eels came up to the island,

squirming, darting, or lazily sunning themselves in its flowering

grounds and lily-ponds, some even finding their way into the very beds

of the people; when the trees were deserted of birds, and alligators

prowled across the terraces, depredating the poultry-yard and even

threatening the negro children.

In the presence of so manifold disaster many of the negroes returned to

voodooism, and nude dances by weird fires offered to Satan supplanted

the shouting of the name of Christ in the churches. A red streak in the

sky over the brake was regarded as an omen of blood — the thunderbolt

which struck the smoke-stack of the sugar-house a command to stop work.

Old women who had treated the sick with savory teas of roots and herbs

lapsed into conjuring with bits of hair and bones. A rabbit’s foot was

more potent than medicine; a snake’s tooth wet with swamp scum and dried

in the glare of burning sulphur more to be feared than God.

War, death and birth and death again, followed by scant provender

threatening famine, and then by the invasion of serpents, had struck

terror into hearts already tremulous and half afraid.

The word “freedom” had scarcely reached the island and set the air

vibrating with hope, commingled with dread, when the reported death of

the master came as a grim corroboration of the startling prospect.

All this is an open story.

But how Israel and Hannah, aided in their flight by a faithful few,

slipped away one dark night, carrying the young child with them to bear

her safely to her father’s people, knowing nothing of their absence,

pending the soldier’s return — for the two never believed him dead; how,

when they had nearly reached the rear lands of the paternal place, they

were met by an irresistible flood which turned them back; and how,

barely escaping with their lives, they were finally rowed in a skiff

quite through the hall of the great house — so high, indeed, that Mammy

rescued a family portrait from the wall as they passed; how the baby

slept through it all, and the dog followed, swimming.

This is part of the inside history never publicly told.

The little party was taken aboard a boat which waited midstream, a tug

which became so overcrowded that it took no account of passengers whom

it carried safely to the city. Of the poor forlorn lot, a few found

their way back to the plantations in search of survivors, but in most

instances, having gone too soon, they returned disheartened.

Madame Le Duc, who, with her guests and servants, had fled from the

homestead at the first warning, did not hear for months of the flight of

the old people with her grandchild, and of their supposed fate. No one

doubted that all three had perished in the river, and the news came as

tardy death tidings again — tidings arriving after the manner of war

news, which often put whole families in and out of mourning, in and out

of season.

VII

THERE

is not space here to dwell upon Harold’s final return to Brake

Island, bent and broken, unkempt, — disguised by the marks of sorrow,

unrecognized, as he had hoped to be, of the straggling few of his own

negroes whom he encountered camping in the wood, imprisoned by fear.

These, mistaking him for a tramp, avoided him. He had heard the news en

route, — the “news,” then several years old, — and had, nevertheless,

yielded to a sort of blind, stumbling fascination which drew him back to

the scene of his happiness and his despair. Here, after all, was the

real battle-field — and he was again vanquished.

When he reached the homestead, he found it wholly deserted. The “big

house,” sacred to superstition through its succession of tragedies, was

as Mammy and Israel had left it. Even its larder was untouched, and the

key of the wine-cellar lay imbedded in rust in sight of the cob-webbed

door.

It was a sad man, prematurely gray, and still gaunt — and white with the

pallor of the hospital prison — who, after this sorrowful pilgrimage to

Brake Island, appeared, as from the grave, upon the streets of New

Orleans. When he was reinstated in his broken home, and known once more

of his family and friends, he would easily have become the popular hero

of the hour, for the gay world flung its gilded doors open to him.

The Latin temperament of old New Orleans kept always a song in her

throat, even through all the sad passages of her history; and there was

never a year when the French quarter, coquette that she was, did not

shake her flounces and dance for a season with her dainty toes against

the lower side of Canal Street.

But Harold was not a fellow of forgetful mind. The arch of his life was

broken, it is true, but like that of the bridge he had begun — a bridge

which was to invite the gay world, yes, but which would ever have

dominated it, letting its sails pass under — he could be no other than a

worthy ruin. Had his impetuous temper turned upon himself on his return

to the island, where devastation seemed to mock him at every turn, there

is no telling where it might have driven him. But a lonely mother, and

the knowledge that his father had died of a broken heart upon the report

of his death, the last of his three sons — the pathetic, dependence of

his mother upon him — the appeal of her doting eyes and the exigencies of

an almost hopeless financial confusion — all these combined as a

challenge to his manhood to take the helm in the management of a wrecked

estate.

It was a saving situation. How often is work the great savior of men!

Once stirred in the direction of effort, Harold soon developed great

genius for the manipulation of affairs. Reorganization began with his

control.

Square-shouldered and straight as an Indian, clear of profile,

deep-eyed, and thoughtful of visage, the young man with the white hair

was soon a marked figure. When even serious men “went foolish over him,”

it is not surprising that ambitious mothers of marriageable daughters,

in these scant days of dearth of men, should have exhibited occasional

fluttering anxieties while they placed their broken fortunes in his

hands.

Reluctantly at first, but afterward seeing his way through experience,

Harold became authorized agent for some of the best properties along the

river, saving what was left, and sometimes even recovering whole estates

for the women in black who had known before only how to be good and

beautiful in the romantic homes and gardens whose pervading perfume had

been that of the orange-blossom.

It was on returning hurriedly from a trip to one of these places on the

upper river — the property of one Marie Estelle Josephine Ramsey de La

Rose, widowed at “Yellow Tavern” — that he sought the ferry skiff on the

night old man Israel answered the call.

VIII

LITTLE

the old man dreamed, while he waited, midstream, trying to think

out his problem, that the solution was so near at hand.

We have seen how the old wife waited and prayed on the shore; how with

her shaded mind she groped, as many a wiser has done, for a comforting,

common-sense understanding of faith, that intangible “substance of

things hoped for,” that elusive “evidence of things not seen.”

In a moment after she heard the creaking of the timbers as the skiff

chafed the landing, even while she rose, as was her habit, to see who

might be coming over so late, she dimly perceived two men approaching,

Israel and another; and presently she saw that Israel held the man’s

hand and that he walked unsteadily.

She started, fearing that her man was hurt; but before she could find

voice of fear or question, Israel had drawn the stranger to her and was

saying in a broken voice:

“Hannah! Hannah! Heah Mars’ Harol’!”

Only a moment before, with her dim eyes fixed upon the sky, she had

experienced a realization of faith, and believed herself confidently

awaiting her master’s coming. And yet, seeing him now in the flesh

before her, she exclaimed:

“What foolishness is dis, ole man? Don’t practice no jokes on me

to-night, Isrul!”

Her voice was almost gruff, and she drew back as she spoke. But even

while she protested, Harold had laid his hand upon her arm.

“Mammy,” he whispered huskily,

“don’t you know your ’indurin’ devil’ — ?”

(This had been her last, worst name for her favorite during his mischief

period.)

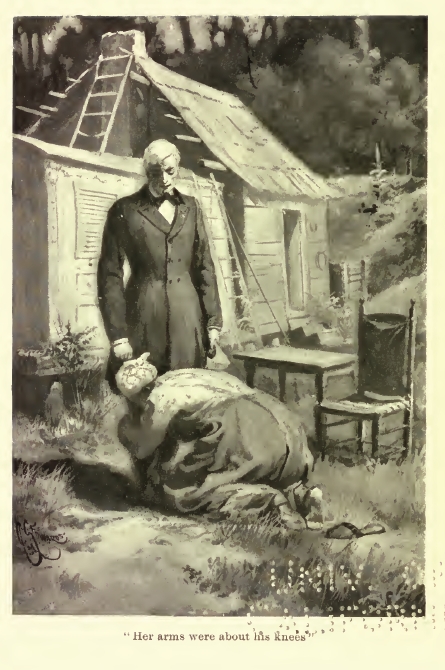

Harold never finished his sentence. The first sound of his voice had

identified him, but the shock had confused her. When at last she sobbed

“Hush! I say, hush!” her arms were about his knees and she was crying

aloud.

“Her arms were about his knees”

“Glo-o-o — oh — glo-o-o — glo-o-ry! Oh, my Gord!” But presently, wiping her

eyes, she stammered: “What kep’ you so, Baby? Hol’ me up, chile — hol’

me!”

She was falling, but Harold steadied her with strong arms, pressing her

into her chair, but retaining her trembling hand while he sat upon the

low table beside her.

He could not speak at once, but, seeing her head drop upon her bosom, he

called quickly to Israel. For answer, a clarion note, in no wise muffled

by the handkerchief from which it issued, came from the woodpile. Israel

was shy of his emotions and had hidden himself.

By the time he appeared, sniffling, Hannah had rallied, and was pressing

Harold from her to better study his face at long range.

“What happened to yo’ hair, Baby?” she said presently. “Hit looks as

bright as dat flaxion curl o’ yoze I got in my Testamen’. I was lookin’

at it only a week ago las’ Sunday, an’ wishin’ I could read de book

’long wid de curl.”

“It is much lighter than that, Mammy. It is whiter than yours. I have

lived the sorrows of a long life in a few years.”

Israel still stood somewhat aside and was taking no note of their

speech, which he presently interrupted nervously:

“H-how you reckon Mars’ Harol’ knowed me, Hannah? He — he reco’nized his

horn! You ricollec’ when I fotched dat horn f’om de islan’ roun’ my

neck, clean ’crost de flood, you made game o’ me, an’ I say I mought

have need of it? But of co’se I didn’t ca’culate to have it ac-chilly

call Mars’ Harol’ home! I sho’ didn’t! But dat’s what it done. Cep’n’

for de horn’s call bein’ so familius, he’d ’a’ paid me my dime like a

stranger an’ passed on.”

At this Harold laughed.

“Sure enough, Uncle Israel; you didn’t collect my ferriage, did you? I

reckon you’ll have to charge that.”

Israel chuckled:

“Lord, Hannah, listen! Don’t dat soun’ like ole times? Dey don’t charge

nothin’ in dese han’-to-mouf days, Marse Harol’ — not roun’ heah.”

“But tell me, Uncle Israel, how did you happen to bring that old horn

with you — sure enough?” Harold interrupted.

“I jes fotched it ’ca’se I couldn’t leave it — de way Hannah snatched

yo’ po’trit off de wall — all in dat deluge. Hit’s heah in de cabin now

to witness de trip. But in co’se o’ time de horn, hit come handy when I

tuk de ferry-skift.

“Well, Hannah, when he stepped aboa’d, he all but shuk de ole skift to

pieces. I ought to knowed dat Le Duc high-step, but I didn’t. I jes felt

his tread, an’ s’luted him for a gentleman, an’ axed him for Gord sake

to set down befo’ we’d be capsided in de river. I war n’t cravin’ to

git drownded wid no aristoc’acy.

“De moon she was hidin’, dat time, an’ we couldn’t see much; but he

leant over an’ he say, ‘Uncle,’ he say, ‘who blowed dat horn ’crost de

river?’ An’ I say, ’Me, sir. I blowed it.’ Den he say, ’Whose horn is

dat?’ An’ I ’spon’, ’Hit’s my horn, sir.’ Den my conscience begin to

gnaw, an’ I sort o’ stammered, ’Leastways, it b’longs to a frien’ o’

mine wha’ look like he ain’t nuver gwine to claim it.’ I ain’t say who

de frien’ was, but d’rec’ly he pushed me to de wall. He ax me p’intedly

to my face, ’What yo’ frien’ name, uncle?’ An at dat I got de big head

an’ I up an’ snap out:

“’Name Le Duc, sir, Harry Le Duc.’

“Jes free an’ easy, so, I say it. Lord have mussy! Ef I’d s’picioned dat

was Mars’ Harol’ settin’ up dar listenin’ at me callin’ his name so

sociable an’ free, I’d ’a’ drapped dem oa’s overbo’ad. I sho’ would.

“Well, when I say ‘Harry Le Duc,’ seem like he got kind o’ seasick, de

way he bent his head down, an’ I ax him how he come on — ef he got de

miz’ry anywhars. An’ wid dat he sort o’ give out a dry laugh, an’ den

what you reckon he ax me? He say, ‘Uncle, is you married?’ An’ wid dat

I laughed. ’T war n’t no trouble for me to laugh at dat. I ’spon’,

’Yas, sirree! You bet I is! Does I look like air rovin’ bachelor?’ I was

jes about half mad by dis time.

“Well, so he kep’ on quizzifyin’ me: ax me whar I live, an’ I tol’ ’im I

was a ole risidenter on de levee heah for five years past; an’ so we run

on, back an’ fo’th, tell we teched de sho’. An’ time de skift bumped de

landin’ he laid his han’ on me an’ he say, ’Unc’ Isrul, whar’s Mammy

Hannah?’ An’ den — bless Gord! I knowed him! But I ain’t trus’ myself to

speak. I des nachelly clawed him an’ drug him along to you. I seen de

fulfilment o’ promise, an’ my heart was bustin’ full, but I ain’t got no

halleluiah tongue like you. I jes passed him along to you an’ made for

de woodpile!”

It was a great moment for Harold, this meeting with the only people

living who could tell all there was to know of those who were gone.

Hannah’s memory was too photographic for judicious reminiscence. The

camera’s great imperfection lies in its very accuracy in recording

non-essentials, with resulting confusion of values. So the old woman,

when she turned her mental search-light backward, “beginning at the

beginning,” which to Harold seemed the end of all — the day of his

departure, — recounted every trivial incident of the days, while Harold

listened through the night, often suffering keenly in his eagerness to

know the crucial facts, yet fearing to interrupt her lest some precious

thing be lost.

A reflected sunrise was reddening the sky across the river when she

reached the place in the story relating to the baby. Her description

needed not any coloring of love to make it charming, and while he

listened the father murmured under his breath:

“And then to have lost her!”

“What dat you say, Marse Harol’?” Hannah gasped, her quick ears having

caught his despairing tone.

“Oh, nothing, Mammy. Go on. It did seem cruel to have the little one

drowned. But I don’t blame you. It is a miracle that you old people

saved yourselves.”

The old woman turned to her husband and threw up her hands.

“Wh-why, Isrul!” she stammered.

“What’s de matter wid you — to set heah all night an’ listen at me

talkin’ all roun’ de baby — an’ ain’t named her yit!”

She rose and, drawing Harold after her, entered the door at her back. As

she pulled aside the curtain a ray of sunlight fell full upon the

sleeping child.

“Heah yo’ baby, Baby!” Her low voice, steadied by its passages through

greater crises, was even and gentle.

She laid her hand upon the child.

“Wek up, baby! Wek up!” she cried. “Yo’ pa done come! Wek up!”

Without stirring even so much as a thread of her golden hair upon the

pillow, the child opened a pair of great blue eyes and looked from

Mammy’s face to the man’s. Then, — so much surer is a child’s faith than

another’s, — doubting not at all, she raised her little arms.

Her father, already upon his knees beside her, bent over, bringing his

neck within her embrace, while he inclosed her slender body with his

arms. Thus he remained, silent, for a moment, for the agony of his joy

was beyond tears or laughter. But presently he lifted his child, and,

sitting, took her upon his lap. He could not speak yet, for while he

smoothed her beautiful hair and studied her face, noting the blue depths

of her darkly fringed eyes, the name that trembled for expression within

his lips was “Agnes — Agnes.”

“How beautiful she is!” he whispered presently; and then, turning to

Hannah, “And how carefully you have kept her! Everything — so sweet.”

“Oh, yas!” the old woman hastened to answer. “We ain’t spared no pains

on ’er, Marse Harol’. She done had eve’ything we could git for her, by

hook or by crook. Of co’se she ain’t had no white kin to christen her,

an’ dat was a humiliation to us. She didn’t have no to say legal person

to bring ’er for’ard, so she ain’t nuver been ca’yed up in church; but

she’s had every sort o’ christenin’ we could reach.

“I knowed yo’ pa’s ma, ole Ma’am Toinette, she’d turn in her grave

lessen her gran’chil’ was christened Cat’lic, so I had her christened

dat way. Dat ole half-blind priest, Father Some’h’n’ other, wha’ comes

from Bayou de Glaise, he was conductin’ mass meetin’ or some’h’n’ other,

down here in Bouligny, an’ I took de baby down, an’ he sprinkled her in

Latin or some’h’n’ other, an’ ornamented behind her ears wid unctious

ile, an’ crossed her little forehead, an’ made her eat a few grains o’

table salt. He done it straight, wid all his robes on, an’ I g’in him

a good dollar, too. An’ dat badge you see on her neck, a sister o’

charity, wid one o’ dese clair-starched ear-flap sunbonnets on, she put

dat on her. She say she give it to her to wear so ’s she could n’t git

drownded — like as ef I’d let her drownd. Yit an’ still I lef’ it so,

an’ I even buys a fresh blue ribbin for it, once-t an’a while. I hear

’em say dat blue hit’s de Hail Mary color — an’ it becomes her eyes, too.

Dey say what don’t pizen fattens, an’ I know dem charms couldn’t do her

no hurt, an’, of ’co’se, we don’t know all. Maybe dey mought ketch de

eye of a hoverin’ angel in de air an’ bring de baby into Heavenly

notice. Of co’se, I wouldn’t put no sech as dat on her. I ain’t been

raised to it, an’ I ain’t no beggin’ hycoprite. But I wouldn’t take it

off, nuther.

“Den, I knowed ole Mis’, yo’ ma, she was ’Pistopal, an’ Miss Aggie she

was Numitarium; so every time a preacher’d be passin’ I’d git him to

perform it his way. Me bein’ Baptis’ I didn’t have no nigger baptism to

saddle on her.

“So she’s bounteously baptized — yas, sir. I reasoned it out dat ef dey’s

only one true baptism, an’ I war n’t to say shore which one it was,

I better git ’em all, an’ only de onlies’ true one would count; an’

den ag’in, ef all honest baptisms is good, den de mo’ de merrier, as de

Book say. Of co’se I knowed pyore rain-water sprinkled on wid a blessin’

couldn’t hurt no chile.

“You see, when one side de house is French distraction an’ de yether

is English to-scent, an’ dey’s a dozen side-nations wid blood to

tell in all de branches, — well, hit minds me o’ dis ba’m of a thousan’

flowers dat ole Mis’ used to think so much of. Hits hard to ’stinguish

out any one flagrams.

“But talkin’ about de baby, she ain’t been deprived, no mo’ ’n de Lord

deprived her, for a season, of her rights to high livin’ an’ — an’

aristoc’acy — an’ — an’ petigree, an’ posterity, an’ all sech as dat.

“An’ —

“What dat you say, Mars’ Harol’? What name is we?’

“We ain’t dast to give ’er no name, Baby, no mo’ ’n jes Blossom. I got

’er wrote down in five citificates ‘Miss Blossom,’ jes so. No, sir. I

knows my colored place, an’ I’ll go so far, an’ dat’s all de further.

She was jes as much a blossom befo’ she was christened as she was

arterwards, so my namin’ ’er don’t count. I was ’mos’ tempted to call

out ’Agnes’ to de preachers, when dey’d look to me for a name, seem’ it

was her right — like as ef she was borned to it; but — I ain’t nuver

imposed on her. No, sir, we ain’t imposed on her noways.

“De on’iest wrong I ever done her — an’ Gord knows I done it to save her

to my arms, an’ for you, marster — de on’iest wrong was to let her go

widout her little sunbonnet an’ git her skin browned up so maybe nobody

wouldn’t s’picion she was clair white an’ like as not try to wrest her

from me. An’ one time, when a uppish yo’ng man ast me her name, I

said it straight, but I see him look mighty cu’yus, an’ I spoke up an’

say, ‘What other name you ’spect’ her to have? My name is Hannah Le Duc,

an’ I’s dat child’s daddy’s mammy.’ Excuse me, Mars’ Harold, but you

know I is yo’ black mammy — an’ I was in so’e straits.

“So de yo’ng man, well, he didn’t seem to have no raisin’. He jes sort

o’ whistled, an’ say I sho is got one mighty blon’ gran’chil’ — an’ I

’spon’, ‘Yas, sir; so it seems.’

“An’ dat’s de on’ies’ wrong I ever done her. She sets up at her little

dinner-table sot wid a table-cloth an’ a white napkin, — an’ I done buyed

her a ginuine silver-plated napkin-ring to hold it in, too, — an’ she

says her own little blessin’ — dat short ‘Grace o’ Gord — material

binefets,’ one o’ Miss Aggie’s; I learned it to her. No, she ain’t been

handled keerless, ef she is been livin’ on de outside o’ de levee, like

free niggers. But we ain’t to say lived here, ’not perzackly,

marster. We jes been waitin’ along, so, dese five years — waitin’ for

to-night.

“I ain’t nuver sorted her clo’es out into no bureau; I keeps ’em all in

her little trunk, perpared to move along.”

For a moment the realization of the culmination of her faith seemed to

suffuse her soul, and as she proceeded, her voice fell in soft, rhythmic

undulations.

“Ya-as, Mars’ Harol’, Mammy’s baby boy, yo’ ol’ nuss she been waitin’,

an’ o-ole man Isrul he been waitin’, an’ de Blossom she been

waitin’. I ’spec’ she had de firmes’ faith, arter all, de baby did. Day

by day we all waited — an’ night by night. An’ sometimes when courage

would burn low an’ de lamp o’ faith grow dim, seem like we’d a’ broke

loose an’ started a-wanderin’ in a sort o’ blind search, ’cep’n’ for de

river.

“Look like ef we’d ever went beyan’ de river’s call, we’d been same as

de chillen o’ Isrul lost in de tanglement o’ de wilderness. All we river

chillen, we boun’ to stay by her, same as toddlin’ babies hangs by a

mammy’s skirts. She’ll whup us one day, an’ chastise us severe; den

she’ll bring us into de light, same as she done to-night — same as reel

mammies does.

“An’, Mars’ Harol’?”

She lowered her voice.

“Mars’ Harol’, don’t tell me she don’t know! I tell yer, me an’ dis

River we done spent many a dark night together under de stars, an’ we

done talked an’ answered one another so many lonely hours — an’ she done

showed us so many mericles on land an’ water?

“I tell yer, I done found out some’h’n’ about de River, Mars’ Harol’.

She’s — why, she’s —

“Oh, ef I could only write it all down to go in a book! We been th’ough

some merac’lous times together, sho’ ’s you born — sho’ ’s you born.

“She’s a mericle mystery, sho’!

“You lean over an’ dip yo’ han’ in her an’ you take it up an’ you say

it’s wet. You dig yo’ oars into her, an’ she’ll spin yo’ boat over her

breast. You dive down into her, an’ you come up — or don’t come up.

Some eats her. Some drinks her. Some gethers wealth outen her. Some

draps it into her. Some drownds in her.

“An’ she gives an’ takes, an’ seem like all her chillen gits

satisfaction outen her, one way an’ another; but yit an’ still, she

ain’t nuver flustered. On an’ on she goes — rain or shine — high

water — low water — all de same — on an’ on.

“When she craves diamonds for her neck, she reaches up wid long

onvisible hands an’ gethers de stars out’n de firmamint.

“De moon is her common breastpin, an’ de sun?

“Even he don’t faze her. She takes what she wants, an’ sends back his

fire every day.

“De mists is a veil for her face, an’ de showers fringes it.

“Sunrise or dusklight, black night or midday, every change she answers

whilst she’s passin’.

“But who ever inticed her to stop or to look or listen? Nobody, Baby.

An’ why?

“Oh, Lord! ef eve’ybody only knowed!

“You see, all sech as dat, I used to study over it an’ ponder befo’ we

started to talk back an’ fo’th — de River an’ me.

“One dark night she heared me cryin’ low on de bank, whilst de ole man

stepped into de boat to row ’crost de water, an’ she felt Wood-duck

settle heavy on her breast, an’ she seen dat we carried de same

troublous thought — searchin’ an’ waitin’ for the fulfilment o’ promise.

“An’ so we started to call — an’ to answer, heart to heart.”

The story is nearly told. No doubt many would be willing to have it stop

here. But a tale of the river is a tale of greed, and must have

satisfaction.

While father and child sat together, Israel came, bringing fresh chips.

He had been among the woodpiles again. This time there followed him the

dog.

“Why, Blucher!” Harold exclaimed. “Blucher, old fellow!” And at his

voice the dog, whining and sniffing, climbed against his shoulder, even

licking his face and his hand. Then, running off, he barked at Israel

and Hannah, telling them in fine dog Latin who the man was who had come.

Then he crouched at his feet, and, after watching his face a moment,

laid his head upon his master’s right foot, a trick Harold had taught

him as a pup.

IX

OF

course Harold wished to take the entire family home with him at once,

and would hear to nothing else until Hannah, serving black coffee to him

from her furnace, in the dawn, begged that she and Israel might have “a

few days to rest an’ to study” before moving.

It was on the second evening following this, at nightfall, while her man

was away in his boat, that the old woman rose from her chair and, first

studying the heavens and then casting about her to see that no one was

near, she went down to the water, slowly picking her way to a shallow

pool between the rafts and the shore. She sat here at first, upon the

edge of the bank, frankly dropping her feet into the water while she

seemed to begin to talk — or possibly she sang, for the low sound which

only occasionally rose above the small noises of the rafts was faintly

suggestive of a priest’s intoning.

For a moment only, she sat thus. Then she began to lower herself into

the water, until, leaning, she could lay her face against the sod, so

that a wave passed over it, and when, letting her weight go, she

subsided, with arms extended, into the shallow pool, a close listener

might have heard an undulating song, so like the river’s in tone as to

be separable from it only through the faint suggestion of words,

interrupted or drowned at intervals by the creaking and knocking of the

rafts and the gurgling of the sucking eddies about them.

The woman’s voice — song, speech, or what not — seemed intermittent, as

if in converse with another presence.

Suddenly, while she stood thus, she dropped bodily, going fully under

the water for a brief moment, as if renewing her baptism, and when she

presently lifted herself, she was crying aloud, sobbing as a child sobs

in the awful momentary despair of grief at the untwining of

arms — shaken, unrestrained.

While she stood thus for a few minutes only, — a pathetic waste of

sorrow, wet, dark and forlorn, alone on the night-shore, — a sudden wind,

a common evening current, threw a foaming wave over the logs beside her

so that its spray covered her over; while the straining ropes, breaking

and bumping timbers, with the slow dripping of the spent wave through

the raft, seemed to answer and possibly to assuage her agitation; for,

as the wind passed and the waters subsided, she suddenly grew still,

and, climbing the bank as she had come, walked evenly as one at peace,

into her cabin.

No one will ever know what, precisely, was the nature of this last

communion. Was it simply an intimate leave-taking of a faithful

companionship grown dear through years of stress? Or had it deeper

meaning in a realization — or hallucination — as to the personality of the

river — the “secret” to which she only once mysteriously referred in a

gush of confidence on her master’s return?

Perhaps she did not know herself, or only vaguely felt what she could

not tell. Certainly not even to her old husband, one with her in life

and spirit, did she try to convey this mystic revelation. We know by

intuition the planes upon which our minds may meet with those of our

nearest and dearest. To the good man and soldier, Israel, — the prophet,

even, who held up the wavering hands of the imaginative woman when her

courage waned, pointing to the hour of fulfilment, — the great river,

full of potencies for good or ill, could be only a river. As a mirror it

had shown him divinity, and in its character it might typify to his

image-loving mind another thing which service would make it precious.

But what he would have called his sanity — had he known the word — would

have obliged him to stop there.

The stars do not tell, and the poor moon — at best only hinting what the

sun says — is fully half-time off her mind. And the

soul of the

River — if, indeed, it has once broken silence — may not speak again.

And, so, her secret is safe — safe even if the broken winds did catch a

breath, here and there, sending it flurriedly through and over the logs

until they trembled with a sort of mad harp-consciousness, and were set

a-quivering for just one full strain — one coherent expression of

soul-essence — when the wave broke. Perhaps the arms of the twin spirits

were untwined — and they went their separate ways smiling — the woman and

the river.

When, after a short time, the old wife came out, dressed in fresh

clothing, her white, starched tignon shining in the moonlight, to sit

and talk with her husband, her composure was as perfect as that of the

face of the water which in its serenity suggested the voice of the

Master, when Peter would have sunk but for his word.

This was to be their last night here. Harold was to bring a carriage on

the next day to take them to his mother and Blossom, and, despite the

joy in their old hearts, it cost them a pang to contemplate going away.

Every woodpile seemed to hold a memory, each feature of the bank a

tender association. Blucher lay sleeping beside them.

Israel spoke first.

“Hannah!” he said.

“What, Isrul?”

“I ready to go home to-night, Hannah. Marse Harol’ done come. We done

finished our ’sponsibility — an’ de big river’s a-flowin’ on to de

sea — an’ settin’ heah, I ’magines I kin see Mis’ Aggie lookin’ down on

us, an’ seem like she mought want to consult wid us arter our meetin’

wid Marse Harol’ an’ we passin’ Blossom along. What you say, Hannah?”

“I been tired, ole man, an’ ef we could ’a’ went las’ night, like you

say, seem like I ’d ’a’ been ready — an’, of co’se, I’m ready now, ef

Gord wills. Peace is on my sperit. Yit an’ still, when we rests off a

little an’ studies freedom free-handed, we won’t want to hasten along

maybe. Ef we was to set heah an’ wait tell Gord calls us, — He ain’t ap’

to call us bofe together, an’ dey’d be lonesome days for the last one.

But ef we goes ’long wid Marse Harol’, he an’ Blossom’ll be a heap o’

comfort to de one what’s left.”

“Hannah!”

“Yas, Isrul.”

“We’s a-settin’ to-night close to de brink — ain’t dat so?”

“Yas, Isrul.”

“An’ de deep waters is in sight, eh, Hannah?”

“Yas, Isrul.”

“An’ we heah it singin’, ef we listen close, eh, Hannah?”

“Yas, Isrul.”

“Well, don’t let ’s forgit it, dat ’s all. Don’t let’s forgit, when we

turns our backs on dis swellin’ tide, dat de river o’ Jordan is jes

befo’ us, all de same — an’ it can’t be long befo’ our crossin’-time.”

“Amen!” said the woman.

The moon shone full upon the great river, making a shimmering path of

light from shore to shore, when the old couple slowly rose and went to

rest.

Toward morning there was a quick gurgling sound in front of the cabin.

Blucher caught it, and, springing out, barked at the stars. The sleepers

within the levee hut slept on, being overweary.

The watchman in the Carrollton garden heard the sound, — heard it swell

almost to a roar, — and he ran to the new levee, reaching its summit just

in time to see the roof of the cabin as it sank, with the entire point

of land upon which it rested, into the greedy flood.

When Harold Le Duc arrived that morning to take the old people home, the

river came to meet him at the brim of the near bank, and its face was as

the face of smiling innocence.

While he stood awe-stricken before the awful fact so tragically

expressed in the river’s bland denial, a wet dog came, and, whining,

crouched at his feet. He barked softly, laid his head a moment upon his

master’s boot, moaned a sort of confidential note, and, looking into the

air, barked again, softly.

Did he see more than he could tell? Was he trying to comfort his master?

He had heard all the sweet converse of the old people on that last

night, and perhaps he was saying in his poor best speech that all was

well.

Mammy Hannah and Uncle Israel, having discharged their responsibility,

had crossed the River together.

PART THIRD

“Oh, it ’s windy,

Sweet Lucindy,

On de river-bank to-night,

An’ de moontime

Beats de noontime,

When de trimblin’ water ’s white.”

SO

runs the plantation love-song, and so sang a great brown fellow as,

with oars over his shoulder, he strolled down “Lovers’ Lane,” between

the bois d’arcs, toward the Mississippi levee.

He repeated it correctly until he neared the gourd-vine which marked the

home of his lady, when he dropped his voice a bit and, eschewing rhyme

for the greater value, sang:

“Oh, it ’s windy,

Sweet Maria,

On de river-bank to-night —”

And slackening his pace until he heard footsteps behind him, he stopped

and waited while a lithe yellow girl overtook him languidly.

“Heah, you take yo’ sheer o’ de load!” he laughed as he handed her one

of the oars. “Better begin right. You tote half an’ me half.” And as she

took the oar he added, “How is you to-night, anyhow, sugar-gal?”

While he put his right arm around her waist, having shifted the

remaining oar to his left side, the girl instinctively bestowed the one

she carried over her right shoulder, so that her left arm was free for

reciprocity, to which it na?vely devoted itself.

“I tell yer, hit ’s fine an’ windy to-night, sho’ enough,” he said. “De

breeze on de levee is fresh an’ cool, an’ de skift she’s got a new

yaller-buff frock, an’ she?”

“Which skift? De Malviny? Is you give her a fresh coat o’ paint? An’

dat’s my favoryte color — yaller-buff!” This with a chuckle.

“No; dey ain’t no Malviny skift no mo’ — not on dis plantation. I done

changed her name.”

“You is, is yer? What is you named her dis time?”

She was preparing to express surprise in the surely expected. Of course

the boat was renamed the Maria. What else, in the circumstances?

“I painted her after a lady-frien’s complexion, a bright, clair yaller;

but as to de name — guess!” said the man, with a lunge toward the girl,

as the oar he carried struck a tree — a lunge which brought him into

position to touch her ear with his lips while he repeated: “What you

reckon I named her, sweetenin’?”

“How should I know? I ain’t in yo’ heart!”

“You ain’t, ain’t yer? Ef you ain’t, I’d like mighty well to know who

is. You’s a reg’lar risidenter, you is — an’ you knows it, too! Guess

along, gal. What you think de boat’s named?”

“Well, ef you persises for me to guess, I’ll say Silv’ Ann. Dat ’s a

purty title for a skift.”

“Silv’ Ann!“ contemptuously. “I ’clare, M’ria, I b’lieve you ’s

jealous-hearted. No, indeedy! I know I run ’roun’ wid Silv’ Ann awhile

back, jes to pass de time, but she can’t name none o’ my boats! No; ef

you won’t guess, I’ll tell yer — dat is, I’ll give you a hint. She named

for my best gal! Now guess!“

“I never was no hand at guessin’.” The girl laughed while she tossed her

head. “Heah, take dis oah, man, an’ lemme walk free. I ain’t ingaged to

tote no half-load yit — as I knows on. Lordy, but dat heavy paddle done

put my whole arm to sleep. Ouch! boy. Hands off tell de pins an’ needles

draps out. I sho’ is glad to go rowin’ on de water to-night.”

So sure was she now of her lover, and of the honor which he tossed as a

ball in his hands, never letting her quite see it, that she whimsically

put away the subject.

She had been to school several summers and could decipher a good many

words, but most surely, from proud practice, she could spell her own

name. As they presently climbed the levee together, she remarked, seeing

the water: “Whar is de boat, anyhow — de What-you-may-call-it? She ain’t

in sight — not heah!”

“No; she’s a little piece up de current — in de willer-clump. I didn’t

want nobody foolin’ wid ’er — an’ maybe readin’ off my affairs. She got

her new intitlemint painted on her stern — every letter a different

color, to match de way her namesake treats me — in a new light every

day.”

The girl giggled foolishly. She seemed to see the contour of her own

name, a bouquet of color reaching across the boat, and it pleased her.

It would be a witness for her — to all who could read.

“I sho’ does like boats an’ water,” she generalized, as they walked on.

“Me, too,” agreed her lover; “but I likes anything — wid my chosen

company. What is dat whizzin’ past my face? Look like a honey-bee.”

“’T is a honey-bee. Dey comes up heah on account o’ de chiny-flowers.

But look out! Dat’s another! You started ’em time you drug yo’ oah in de

mids’ o’ dem chiny-blossoms. Whenever de chiny-trees gits too sickenin’

sweet, look out for de bees!”

“Yas,” chuckled de man; “an’ dey’s a lesson in dat, ef we’d study over

it. Whenever life gits too sweet, look out for trouble! But we won’t

worry ’bout dat to-night. Is you ’feared o’ stingin’ bees?”

“No, not whilst dey getherin’ honey — dey too busy. Hit ’s de idlers dat

I shun. An’ I ain’t afeared o’ trouble, nuther. Yit an’ still, ef

happiness is a sign, I better look sharp.”

“Is you so happy, my Sugar?”

The girl laughed.

“I don’t know ef I is or not — I mus’ see de name on dat skift befo’ I

can say. Take yo’ han’ off my wais’, boy! Ef you don’t I’ll be ’feared

o’ stingin’ bees, sho’ enough! Don’t make life too sweet!”

They were both laughing when the girl dashed ahead into the

willow-clump, Love close at her heels, and in a moment the Maria, in

her gleaming dress of yellow, darted out into the sunset.

A boat or two had preceded them, and another followed presently, but it

takes money to own a skiff, or even to build one of the driftwood, which

is free to the captor. And so most of the couples who sought the river

strolled for a short space, finding secluded seats on the rough-hewn

benches between the acacia-trees or on the drift-dogs which lined the

water’s edge. It was too warm for continued walking.

From some of the smaller vessels, easily recognizable as of the same

family as the fruit-luggers which crowd around “Picayune Tier” at the

French market, there issued sweet songs in the soft Italian tongue,

often accompanied by the accordeon.

Young Love sang on the water in half a dozen tongues, as he sings there

yet at every summer eventide.

The skiffs for the most part kept fairly close to the shore, skirting

the strong current of the channel, avoiding, too, the large steamboats,

whose passage ever jeopardized the small craft which crossed in their

wake.

Indeed, the passage of one of these great “packets” generally cleared

the midstream, although a few venturesome oarsmen would often dare fate

in riding the billows in her wake. These great steamboats were known

among the humble river folk more for their wave-making power than for

the proud features which distinguished them in their personal relations.

There were those, for instance, who would watch for a certain great boat

called the Capitol, just for the bravado of essaying the bubbling

storm which followed her keel, while some who, enjoying their fun with

less snap of danger, preferred to have their skiffs dance behind the

Laurel Hill. Or perhaps it was the other way: it may have been the

Laurel Hill, of the sphere-topped smoke-stacks, which made the more

sensational passage.

It all happened a long time ago, although only about thirteen years had

passed since the events last related, and both boats are dead. At least

they are out of the world of action, and let us hope they have gone to

their rest. An old hulk stranded ashore and awaiting final dissolution

is ever a pathetic sight, suggesting a patient paralytic in his chair,

grimly biding fate — the waters of eternity at his feet.

At intervals, this evening, fishermen alongshore — old negroes

mostly — pottered among the rafts, setting their lines, and if the

oarsmen listened keenly, they might almost surely have caught from these

gentle toilers short snatches of low-pitched song, hymns mostly, of

content or rejoicing.

There was no sense of the fitness of the words when an ancient fisher

sang “Sweet fields beyan’ de swelling flood,” or of humor in “How firm

a foundation,” chanted by one standing boot-deep in suspicious sands.

The favorite hymn of several of the colored fishermen, however, seemed

to be “Cometh our fount of every blessin’,” frankly so pronounced with

reverent piety.

At a distant end of his raft, hidden from its owner by a jutting point

from which they leaped, naked boys waded and swam, jeering the deaf

singer as they jeered each passing boat, while occasionally an

adventurous fellow would dive quite under a skiff, seizing his

opportunity while the oars were lifted.

None of the little rowboats carried sail as a rule, although sometimes a

sloop would float by with an air of commanding a squadron of the sparse

fleet which extended along the length of the river.

The sun was fallen nearly to the levee-line this evening when one of the

finest of the “river palaces” hove in sight.

The sky-hour for “dousing the great glim” was so near — and the actual

setting of the sun is always sudden — that, while daylight still

prevailed, all the steamer’s lights were lit, and although the keen sun

which struck her as a search-light robbed her thousand lamps of their

value, the whole scene was greater for the full illumination.

The people along shore waved to the passing boat — they always do it — and

the more amiable of the passengers answered with flying handkerchiefs.

As she loomed radiant before them, an aged negro, sitting mending his

net, remarked to his companion:

“What do she look like to you, Br’er Jones?”

“’What she look like to me?’” The man addressed took his pipe from his

lips at the question. “What she look like — to me?” he repeated again.

“Why, tell the trufe, I was jes’ studyin’ ’bout dat when you spoke. She

’minds me o’ Heaven; dat what she signifies to my eyes — Heavenly

mansions. What do she look like to you?”

“Well,” the man shifted the quid in his mouth and lowered his shuttle as

he said slowly, “well, to my observance, she don’t answer for Heaven; I

tell yer dat: not wid all dat black smoke risin’ outen ’er ’bominable

regions. She’s mo’ like de yether place to me. She may have Heavenly

gyarments on, but she got a hell breath, sho’. An’ listen at de band o’

music playin’ devil-dance time inside her! An’ when she choose to let it

out, she’s got a-a-nawful snort — she sho’ is!”

“Does you mean de cali-ope?”

“No; she ain’t got no cali-ope. I means her clair whistle. Hit’s got a

jedgment-day sound in it to my ears.”

“Dat music you heah’, dat ain’t no dance-music. She plays dat for de

passengers to eat by, so dey tell me. But I reckon dey jes p’onounces

supper dat-a-way, same as you’d ring a bell. An’ when de people sets

down to de table, dey mus’ sho’ly have de manners to stop long enough to

let ’em eat in peace. Yit an’ still, whilst she looks like Heaven, I’d a

heap ruther set heah an’ see her go by ’n to put foot in her, ’ca’se I’d

look for her to ’splode out de minute I landed in her an’ to scatter my

body in one direction an’ my soul somewhars else. No; even ef she was

Heaven, I’d ruther ’speriment heah a little longer, settin’ on de sof’

grass an’ smellin’ de yearnin’ trees an’ listenin’ at de bumblebees

a-bumblin’, an’ go home an’ warm up my bacon an’ greens for supper, an’

maybe go out foragin’ for my Sunday chicken to-night in de dark o’ de

moon. Hyah! My stomach hit rings de dinner-bell for me, jes as good as a

brass ban’.”

“Me, too!” chuckled the smoker. “I’ll take my chances on dry lan’, every

time. I know I’ll nuver lead a p’ocession but once-t, and dat’ll be at

my own fun’al, an’ I don’t inten’ to resk my chances. But she is sho’

one noble-lookin’ boat.”

By this time the great steamboat — the wonderful apparition so aptly

typifying Heaven and hell — had passed.

She carried only the usual number of passengers, but at this evening

hour they crowded the guards, making a brilliant showing. Family parties

they were mostly, with here and there groups of young folk, generally

collected about some popular girl who formed a center around which

coquetry played mirthfully in the breeze. A piquant Arcadian bride,

“pretty as red shoes,” artlessly appearing in all her white wedding

toggery, her veil almost crushed by its weight of artificial

orange-flowers, looked stoically away from the little dark husband who

persisted in fanning her vigorously, while they sat in the sun-filled

corner which they had taken for its shade while the boat was turned into

the landing to take them aboard. And, of course, there was the usual

quota of staid couples who had survived this interesting stage of life’s

game.

Nor was exhibition of rather intimate domesticity entirely missing.

Infancy dined in Nature’s own way, behind the doubtful screening of

waving palmetto fans. While among the teething and whooping-cough

contingents the observer of life might have found both tragedy and

comedy for his delectation.

Mild, submissive mothers of families, women of the Creole middle class

mainly, — old and withered at thirty-five, all their youthful magnolia

tints gone wrong, as in the flower when its bloom is passed — exchanged

maternal experiences, and agreed without dissent that the world was full

of trouble, but “God was good.”

Even a certain slight maternal wisp who bent over a tiny waxen thing

upon her lap, dreading each moment to perceive the flicker in her breath

which would show that a flame went out — even she, poor tear-dimmed soul,

said it while she answered sympathetic inquiry:

“Oh, yas; it is for her we are taking de trip. Yas, she is very sick,

mais God is good. It is de eye-teet’. De river’s breath it is de bes’

medicine. De doctor he prescribe it. An’ my father he had las’ winter

such a so much trouble to work his heart, an’ so, seeing we were coming,

he is also here — yas, dat’s heem yonder, asleep. ’T is his most best

sleep for a year, lying so. De river she give it. An’ dose ferryboat dey

got always on board too much whooping-cough to fasten on to eye-teet.”

Somewhat apart from the other passengers, their circle loosely but

surely defined by the irregular setting of their chairs toward a common

center, sat a group, evidently of the great world — most conspicuous

among them a distinguished-looking couple in fresh mid-life, who led the

animated discussion, and who were seen often to look in the direction of

a tall and beautiful girl who stood in the midst of a circle of young

people within easy call. It was impossible not to see that their

interest in the girl was vital, for they often exchanged glances when

her laughter filled the air, and laughed with her, although they knew

only that she had laughed.

The girl stood well in sight, although “surrounded six deep” by an

adoring crowd; nor was this attributable alone to her height which set

her fine little head above most of her companions. A certain distinction

of manner — unrelated to haughtiness, which may fail in effect, or

arrogance, which may over-ride but never appeal; perhaps it was a

graciousness of bearing — kept her admirers ever at a tasteful distance.

There was an ineffable charm about the girl, a thing apart from the

unusual beauty which marked her in any gathering of which she became a

part.

Descriptions are hazardous and available words often inadequate to the

veracious presentment of beauty, and yet there is ever in perfection a

challenge to the pen.

As the maiden stood this evening in the sunlight, her radiant yellow

hair complementing the blue of her sea-deep eyes, her fair cheeks

aglow, and one color melting to another in her quick movements, the

effect was almost like an iridescence. Tender in tints as a sea-shell,

there might have been danger of lapse into insipidity but for the accent

of dark rims and curled lashes which individualized the eyes, and, too,

the strong, straight lines of her contour, which, more than the note of

dark color, marked her a Le Duc.

There are some women who naturally hold court, no matter what the

conditions of life, and to whom tribute comes as naturally as the air

they breathe. It often dates back into their spelling-class days, and I

am not sure that it does not occasionally begin in the “perambulator.”

This magnetic quality — one hesitates to use an expression so nervously

prostrated by strenuous overwork, and yet it is well made and to

hand — this magnetic quality, then, was probably, in Agnes Le Duc, the

gift of the Latin strain grafted upon New England sturdiness and

reserve, the one answering, as one might say, for ballast, while the

other lent sail for the equable poising of a safe and brilliant

life-craft.

So, also, was her unusual beauty markedly a composite and of elements so

finely contrasting that their harmonizing seemed rather a succession of

flashes, as of opposite electric currents meeting and breaking through

the caprice of temperamental disturbance; as in the smile which won by

its witchery, or the illumination with which rapid thought or sudden

pity kindled her eye.

Educated alternately in Louisiana where she had recited her history

lessons in French, and in New England, the pride and pet of a charmed

Cambridge circle, with occasional trips abroad with her “parents,” she

was emerging, all unknowingly, a rather exceptional young woman for any

place or time.

Seeing her this evening, an enthusiast might have likened her to the

exquisite bud of a great tea-rose, regal on a slender stem — shy of

unfolding, yet ultimately unafraid, even through the dewy veil of

immaturity — knowing full well, though she might not stop to remember,

the line of court roses in her pedigree.

Watching her so at a safe distance, one could not help wondering that

she thought it worth her while to listen at all, seeing how her admirers

waited upon her every utterance. To listen well has long been considered

a grace — just to listen; but there is a still higher art, perhaps, in

going a step beyond. It is to listen with enthusiasm, yes, even with

eloquence. One having a genius for this sort of oratory, speaking

through the inspired utterance of another, and of course supplying the

inspiration, gains easily the reputation of “delightful conversational

powers.”

And this was precisely an unsuspected quality which made for the sweet

girl much of the popularity which she had never analyzed or questioned.

She could talk, and in several languages, familiarly, and when the

invitation arrived, she did — upward, with respect, to her elders (she

had learned that both in New Orleans and in Boston); downward to her

inferiors — with gentle directness, unmixed with over-condescension; to

right and to left among her companions, quite as a free-hearted girl,

with spirit and camaraderie.

A quality, this, presaging social success certainly, and, it must be

admitted, it is a quality which sometimes adorns natures wanting in

depth of affection. That this was not true of Agnes Le Duc, however,

seems to be clearly shown in an incident of this trip.

As she stood with her companions this evening, while one and another

commented upon this or that feature of the shore, they came suddenly

upon a congregation of negroes encircling an inlet between two curves in

the levee, and, as the low sun shone clearly into the crowd, it became

immediately plain that a baptism was in progress.

A line of women, robed in white, stood on one side; several men,

likewise in white, on the other, while the minister, knee-deep in the

water, was immersing a subject who shouted wildly as he went under and

came up struggling as one in a fit, while two able-bodied men with

difficulty bore him ashore.

The scene was scarcely one to inspire reverence to a casual observer,

and there was naturally some merriment at its expense. One playful

comment led to another until a slashing bit of ridicule brought the

entire ceremony into derision, and, as it happened, the remark with its

accompanying mimicry was addressed to Agnes.

“Oh, please!” she pleaded, coloring deeply. “I quite understand how it

may affect you; but — oh, it is too serious for here — too personal and

too sacred?”

While she hesitated, the culprit, ready to crawl at her feet, — innocent,

indeed, of the indelicacy of which he had become technically

guilty, — begged to be forgiven. He had quite truly “meant no harm.”

“Oh, I am quite sure of it,” the girl smiled; “but now that I have

spoken, — and really I could not help it; I could not wish to let it

pass, understand, — but now that I have spoken — oh, what shall I say!

“Perhaps you will understand me when I tell you that I should not be

with you here to-day but for the devoted care of two old Christian

people who dated their joy in the spiritual life from precisely such a

ceremony as this. They are in Heaven now.