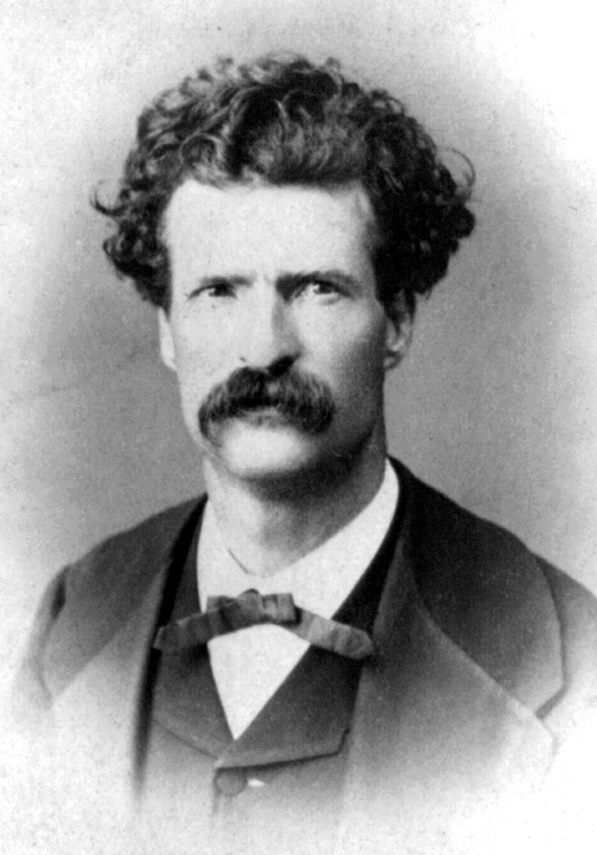

Sam Clemens.

To Pamela A. Moffett

9 and 11 March 1859

New Orleans, La.

[It’s the be]ginning of Lent, and all good Catholics

eat and drink freely of what they please, and, in fact, do

what they please, in order that they may

be the better able to keep sober and quiet during the coming fast.

It has been said that a Scotchman has not seen the world until he

has seen Edinburgh; and I think that I may say that an American

has not seen the United States until he has seen

Mardi-Gras

in New

Orleans.

[It’s the be]ginning of Lent, and all good Catholics

eat and drink freely of what they please, and, in fact, do

what they please, in order that they may

be the better able to keep sober and quiet during the coming fast.

It has been said that a Scotchman has not seen the world until he

has seen Edinburgh; and I think that I may say that an American

has not seen the United States until he has seen

Mardi-Gras

in New

Orleans.

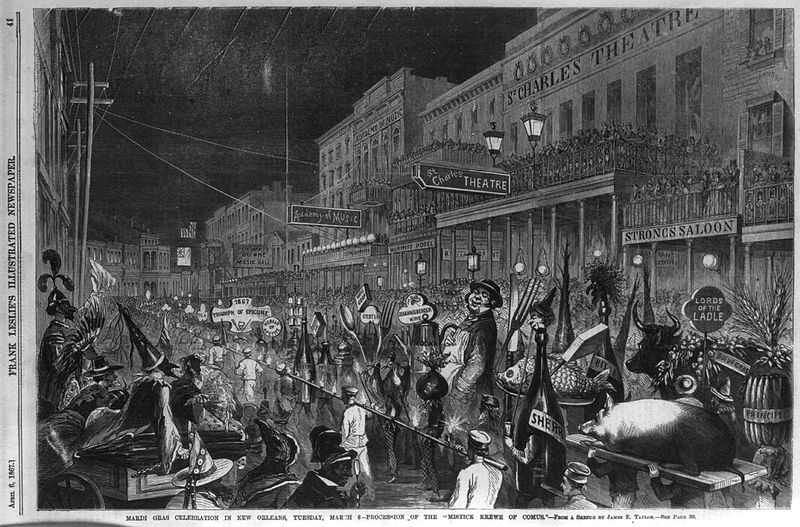

Mystick Krewe of Comus Parade, March 6, 1867,

by James E. Taylor.

(je parle américain).

I posted off up town yesterday morning as soon as the boat landed, in blissful ignorance of the great day. At the corner of Good-Children and Tchoupitoulas streets, I beheld an apparition! — and my first impulse was to dodge behind a lamp-post. It was a woman — a hay-stack of curtain calico, ten feet high — sweeping majestically down the middle of the street (for what pavement in the world could accommodate hoops of such vast proportions?) Next I saw a girl of eighteen, mounted on a fine horse, and dressed as a Spanish Cavalier, with long rapier, flowing curls, blue satin doublet and half-breeches, trimmed with broad white lace — (the balance of her dainty legs cased in flesh-colored silk stockings) — white kid gloves — and a nodding crimson feather in the coquettishest little cap in the world. She removed said cap and bowed low to me, and nothing loath, I bowed in return — but I could n’t help murmuring, “By the beard of the Prophet, Miss, but you’ve mistaken your man this time — for I never saw your silk mask before, — nor the balance of your costume, either, for that matter.” And then I saw a hundred men, women and children in fine, fancy, splendid, ugly, coarse, ridiculous, grotesque, laughable costumes, and the truth flashed upon me — “This is Mardi-Gras!” It was Mardi-gras — and that young lady had a perfect right to bow to, shake hands with, or speak to, me, or any body else she pleased. The streets were soon full of “Mardi-gras,” representing giants, Indians, nigger minstrels, monks, priests, clowns, — birds, beasts, — everything, in fact, that one could imagine. The “free-and-easy” women turned out en masse — and their costumes and actions were very trying to modest eyes. The finest sight I saw during the day was a band of twenty stalwart men, splendidly arrayed as Comanche Indians, flying and yelling down the street on horses as finely decorated as themselves. It was worth going a long distance to see the performances of the day — but bless me! how insignificant they seemed in comparison with those of the night, when the grand torchlight procession of the “Mystic Krewe of Comus” was added. At half past seven in the evening I went up to St. Charles street, and found both its pavements, for many squares, packed and jammed with thousands of men and women, waiting to see the Mystic Krewe. I managed to get an eligible place near the middle of the street opposite the St. Charles Hotel, where I waited — yes, I waited — standing on both feet as long as I could — then on one — then on tother — and was just preparing to stand on my head awhile, when a shout of “Here they come!” kept me still in the proper position of a box of glassware. But it was a false alarm — and after a while we had another false alarm — and then another — each repetition stirring up the impatience and anxiety of the crowd & setting it to heaving and surging at a fearful rate. At last the distant tinkling of lively music was heard — and then the tag-end of a great huzza that had battered nearly all the life out of itself by butting against many squares of hard brick houses before it reached us — and again the tinkling music, and again the faint huzza — and five thousand people near me were tip-toeing & bobbing & peeping down the long street, & wondering why the devil it didn’t come along faster — if it ever expected to get in sight. Impatience was growing, now — for ever so far away down the street we could see a flare of light seeming some a little sun spreading away from a line of dancing colored spots. They approached faster, then, & pretty soon, we took up the fainting huzza, & breathed new life into it. And here was the procession at last. The torches were of all colors, but their shapes represented the spots on a pack of cards-an endless line of hearts, and clubs, &c. The procession was led by a mounted Knight Crusader in blazing gilt armor from head to foot, and I think one might never tire of looking at the splendid picture. Then followed tall, grotesque maskers representing some ancient game — then an odd figure covered with checks, with a huge chess board & chessmen for a hat-then another quaint fellow gleaming in backgammon stripes, with two great dice for a hat — then the kings of each suit of cards dressed in royal regalia of ermine, satin & gold — then queer figures representing various other games, — then the Queen of the Fairies, with a winged troop of beauties, in airy costumes at her heels-then the King & Queen of the Genii, I suppose (eight or ten feet high,) with vast rolls of flaxen curls, bowing majestically to the crowd-followed by a couple of infinitesimal dwarfs, — and again by other genii, in costumes grotesque, hideous & beautiful in turn-then figures whose bodies were vast drums, trumpets, clarinets, fiddles, &c., — followed by others whose bodies were pitchers, punch-bowls, goblets, &c., terminated by two tremendous & very unsteady black wine bottles — then gigantic chickens, turkeys, bears, & other beasts & birds — then a big Christmas tree, followed by Santa Claus, with fur cap, short pipe, &c., and surrounded by a great basket filled with toys-and then-well, I don’t remember half. There were transparencies, marking the divisions, with a band of music to each. Under “May-day” was a beautifully decorated May-tree & a May-pole; — after “Twelfth-Night” followed a troupe of the most outrageously hideous figures, half-beast, half-human, that one could imagine; — Santa Claus & his crew followed “Christmas” — the games, &c., followed “Comus at his old English tricks, again,” and if there were any other transparencies, I have forgotten them. The long procession blazed with brand-new silk and satin, and the whole thing seemed to have been gotten up without any regard to cost.

Certainly New Orleans seldom does things by halves.

New Orleans, Friday 11th.

I saw our little Princesses, Countesses, or whatever they are — the Piccolominis — in St. Charles street yesterday. They came down from Memphis in the cars, I believe. Their first concert takes place to-night, and we shall leave this afternoon. So we shall not hear the young lady sing. We had a souvenir of the warbler written on our old slate, but some sacrilegious scoundrel rubbed it out. It was “Je suis fachèr qu’il faut que nous allons de ce batteau à la Memphis.” (“I am sorry that we must leave the boat at Memphis.”) To which I replied en mauvais française, “Nous seront nous aussi très fachèr.” (We shall be very sorry, also.) Ben was going to “head” it “The Lament of the Irish Emigrant,” & sell the old slate to Barnum for five hundred dollars. Ben said he had a very interesting conversation with the “old dowager,” Madame Pic. He remarked — “I imagine, Madame, that if it would only drizzle a little more, the weather would soon be in splendid condition for young ducks!” And she replied — “Ah, mio, mio, — une petè — I not can ondersthand not!” “Yes’m, it’s a great pity you can’t ondersthand not, for it has cost you the loss of a very sage remark.” And she followed with a tremendous gush of the musical language. Then Benjamin — “Yes, madame, you’re very right — very right indeed. I acknowlege the justice of your remarks, but the devil of it is, I’m a little in the dark as to what you’ve been saying all the time!”

In eight days from this, I shall be in Saint Louis, but I am afraid if I am not careful I’ll beat this letter there.

|

My love to all, Your brother Sam |

Notes

- Mardi-Gras. Mardi Gras fell on March 8 in 1859.

- “Mystic Krewe of Comus”. Founded in 1856, the Krewe of Comus is the oldest Mardi Gras Krewe and is still active today. The organization spelled "crew" as "krewe" to sound archaic. By the time Twain saw the parade, it was already beginning to attract tourists.

- Piccolominis. An Italian noble family that rose to prominence in the 1200s.

- En mauvais française. In poor French.

Source

Clemens, Samuel L. “SLC to Pamela A. Moffett, 9 and 11 March 1859, New Orleans, La. (UCCL 00019).” In Mark Twain’s Letters, 1853 — 1866. Edited by Edgar Marquess Branch, et al. Mark Twain Project Online. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 1988, 2007. Web. 29 Aug. 2012 <http:// www. mark twain project. org/xtf/ view?docId= letters/ UCCL00019. xml;style= letter; brand=mtp>.