Anthology

of Louisiana Literature

Mark Twain.

Life on the Mississippi.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER I.

The Mississippi is Well worth Reading about.—It is Remarkable.—

Instead of Widening towards its Mouth, it grows Narrower.—It Empties

four hundred and six million Tons of Mud.—It was First Seen in 1542.

—It is Older than some Pages in European History.—De Soto has

the Pull.—Older than the Atlantic Coast.—Some Half-breeds chip

in.—La Salle Thinks he will Take a Hand.

CHAPTER II.

La Salle again Appears, and so does a Cat-fish.—Buffaloes also.

—Some Indian Paintings are Seen on the Rocks.—“The Father of

Waters” does not Flow into the Pacific.—More History and Indians.

—Some Curious Performances—not Early English.—Natchez, or

the Site of it, is Approached.

CHAPTER III.

A little History.—Early Commerce.—Coal Fleets and Timber Rafts.

—We start on a Voyage.—I seek Information.—Some Music.—The

Trouble begins.—Tall Talk.—The Child of Calamity.—Ground

and lofty Tumbling.—The Wash-up.—Business and Statistics.—

Mysterious Band.—Thunder and Lightning.—The Captain speaks.

—Allbright weeps.—The Mystery settled.—Chaff.—I am Discovered.

—Some Art-work proposed.—I give an Account of Myself.—Released.

CHAPTER IV.

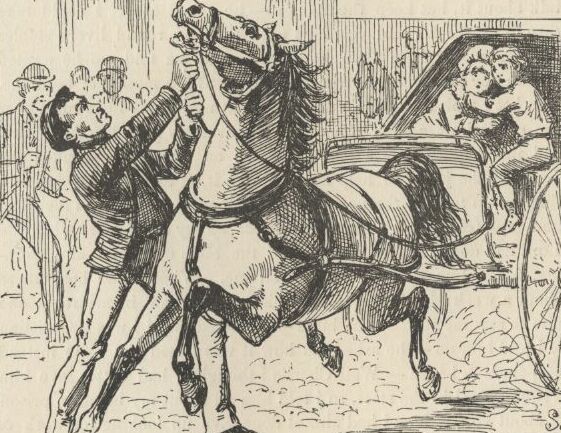

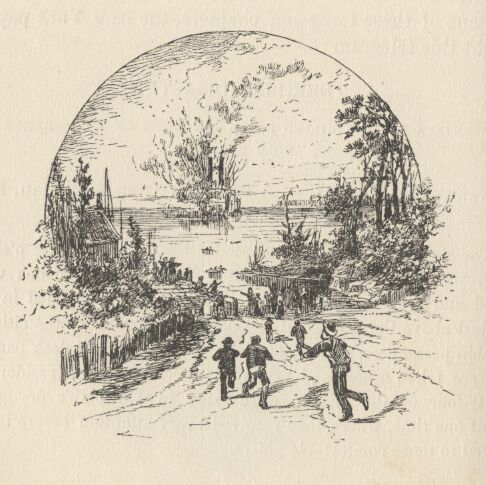

The Boys’ Ambition.—Village Scenes.—Steamboat Pictures.

—A Heavy Swell.—A Runaway.

CHAPTER V.

A Traveller.—A Lively Talker.—A Wild-cat Victim.

CHAPTER VI.

Besieging the Pilot.—Taken along.—Spoiling a Nap.—Fishing for a

Plantation.—“Points” on the River.—A Gorgeous Pilot-house.

CHAPTER VII.

River Inspectors.—Cottonwoods and Plum Point.—Hat-Island Crossing.

—Touch and Go.—It is a Go.—A Lightning Pilot.

CHAPTER VIII.

A Heavy-loaded Big Gun.—Sharp Sights in Darkness.—Abandoned to

his Fate.—Scraping the Banks.—Learn him or Kill him.

CHAPTER IX.

Shake the Reef.—Reason Dethroned.—The Face of the Water.

—A Bewitching Scene.-Romance and Beauty.

CHAPTER X.

Putting on Airs.—Taken down a bit.—Learn it as it is.—The River

Rising.

CHAPTER XI.

In thg Tract Business.—Effects of the Rise.—Plantations gone.

—A Measureless Sea.—A Somnambulist Pilot.—Supernatural Piloting.

—Nobody there.—All Saved.

CHAPTER XII.

Low Water.—Yawl sounding.—Buoys and Lanterns.—Cubs and

Soundings.—The Boat Sunk.—Seeking the Wrecked.

CHAPTER XIII.

A Pilot’s Memory.—Wages soaring.—A Universal Grasp.—Skill and

Nerve.—Testing a “Cub.”—“Back her for Life.”—A Good Lesson.

CHAPTER XIV.

Pilots and Captains.—High-priced Pilots.—Pilots in Demand.

—A Whistler.—A cheap Trade.—Two-hundred-and-fifty-dollar Speed.

CHAPTER XV.

New Pilots undermining the Pilots’ Association.—Crutches and Wages.

—Putting on Airs.—The Captains Weaken.—The Association Laughs.

—The Secret Sign.—An Admirable System.—Rough on Outsiders.

—A Tight Monopoly.—No Loophole.—The Railroads and the War.

CHAPTER XVI.

All Aboard.—A Glorious Start.—Loaded to Win.—Bands and Bugles.

—Boats and Boats.—Racers and Racing.

CHAPTER XVII.

Cut-offs.—Ditching and Shooting.—Mississippi Changes.—A Wild

Night.—Swearing and Guessing.—Stephen in Debt.—He Confuses

his Creditors.—He makes a New Deal.—Will Pay them Alphabetically.

CHAPTER XVIII.

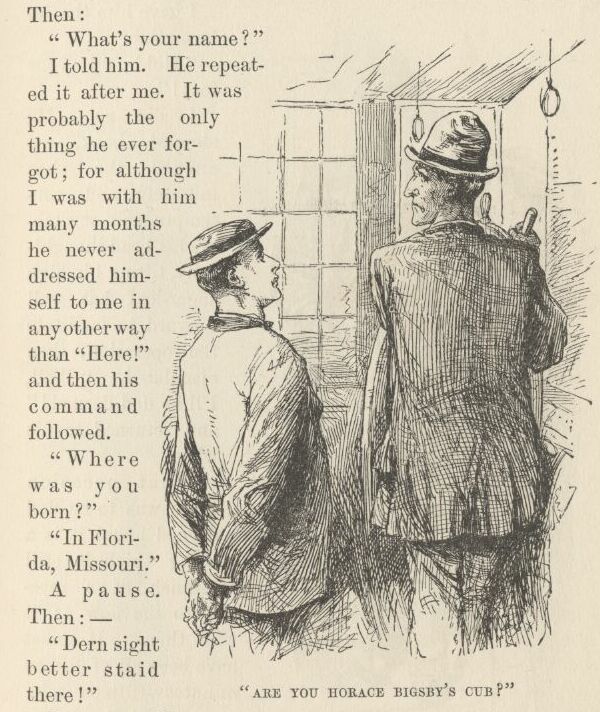

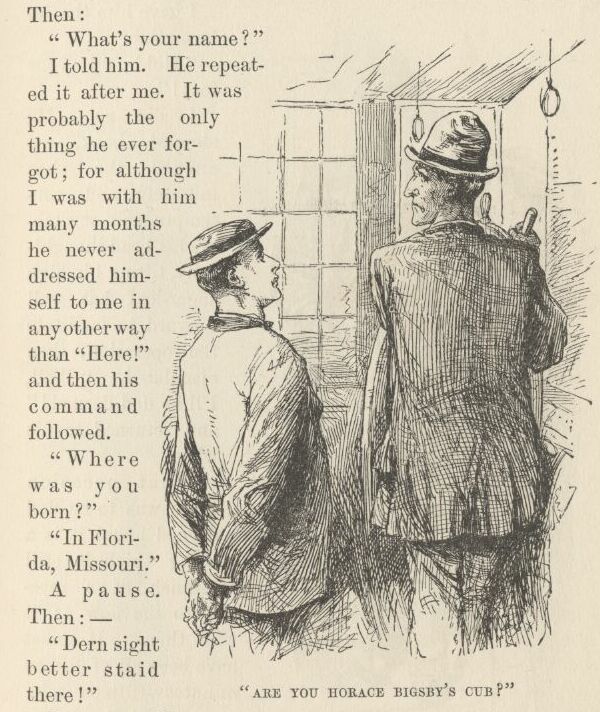

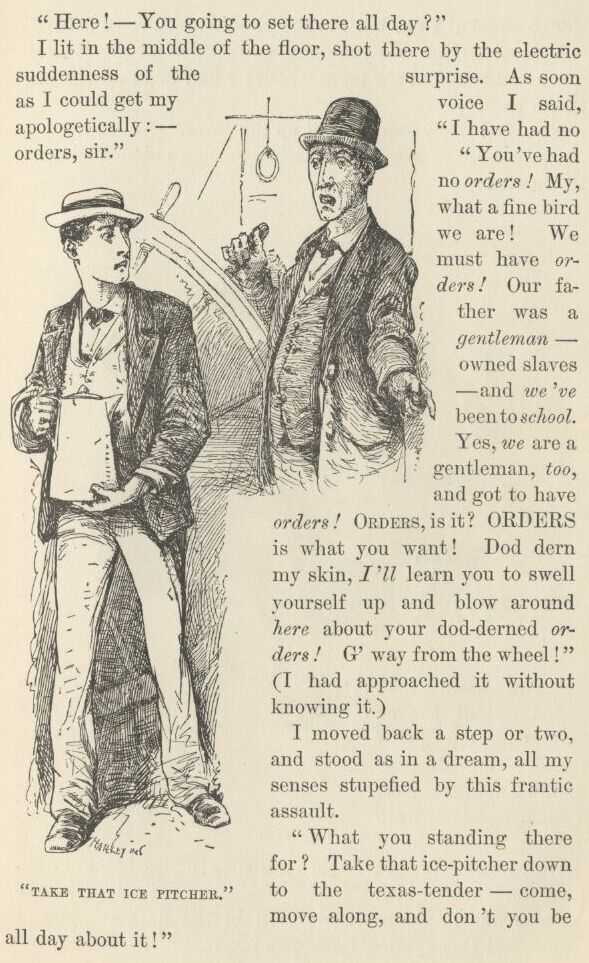

Sharp Schooling.—Shadows.—I am Inspected.—Where did you get

them Shoes?—Pull her Down.—I want to kill Brown.—I try to run

her.- I am Complimented.

CHAPTER XIX.

A Question of Veracity.—A Little Unpleasantness.—I have an

Audience with the Captain.—Mr. Brown Retires.

CHAPTER XX.

I become a Passenger.—We hear the News.—A Thunderous Crash.

—They Stand to their Posts.—In the Blazing Sun.—A Grewsome

Spectacle.—His Hour has Struck.

CHAPTER XXI.

I get my License.—The War Begins.—I become a Jack-of-all-trades.

CHAPTER XXII.

I try the Alias Business.—Region of Goatees—Boots begin to Appear.

—The River Man is Missing.—The Young Man is Discouraged.—

Specimen Water.—A Fine Quality of Smoke.—A Supreme Mistake.

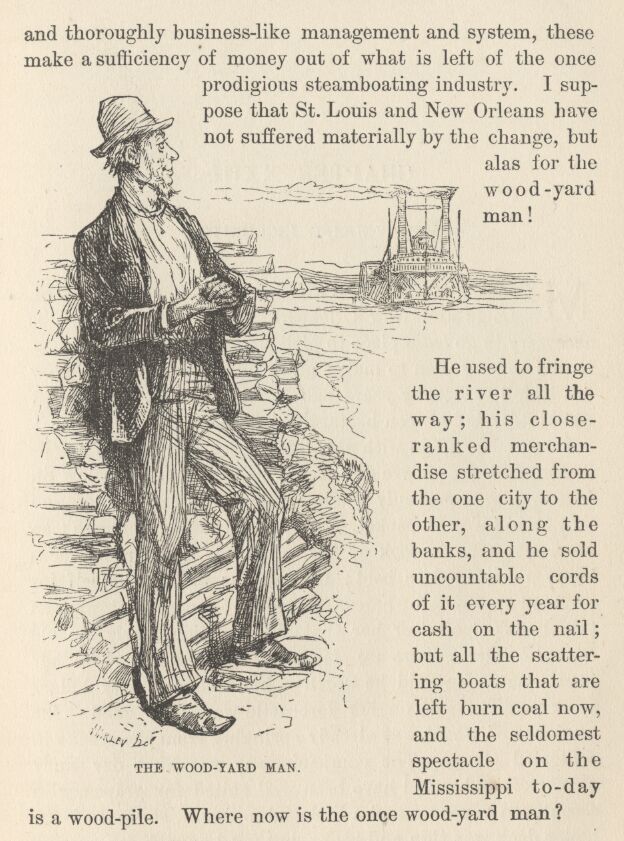

—We Inspect the Town.—Desolation Way-traffic.—A Wood-yard.

CHAPTER XXIII.

Old French Settlements.—We start for Memphis.—Young Ladies and

Russia-leather Bags.

CHAPTER XXIV.

I receive some Information.—Alligator Boats.—Alligator Talk.

—She was a Rattler to go.—I am Found Out.

CHAPTER XXV.

The Devil’s Oven and Table.—A Bombshell falls.—No Whitewash.

—Thirty Years on the River.-Mississippi Uniforms.—Accidents and

Casualties.—Two hundred Wrecks.—A Loss to Literature.—Sunday-

Schools and Brick Masons.

CHAPTER XXVI.

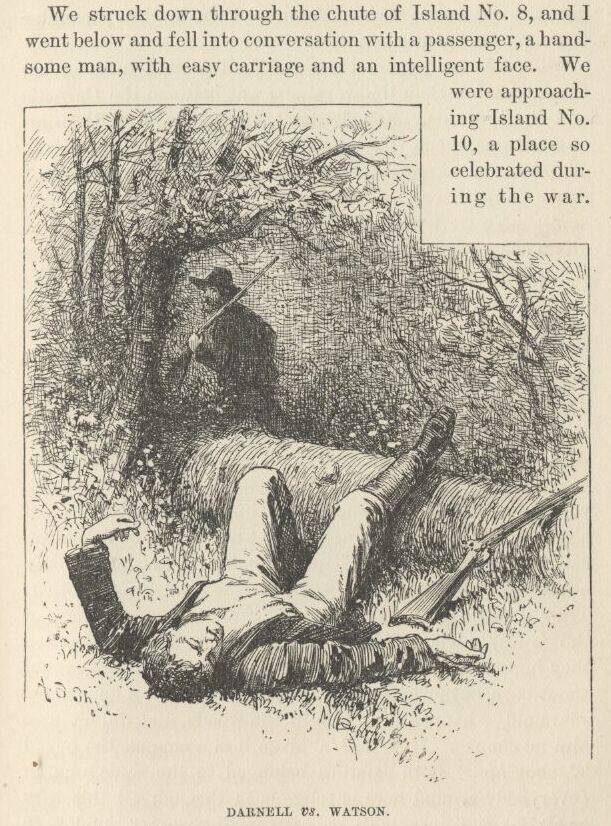

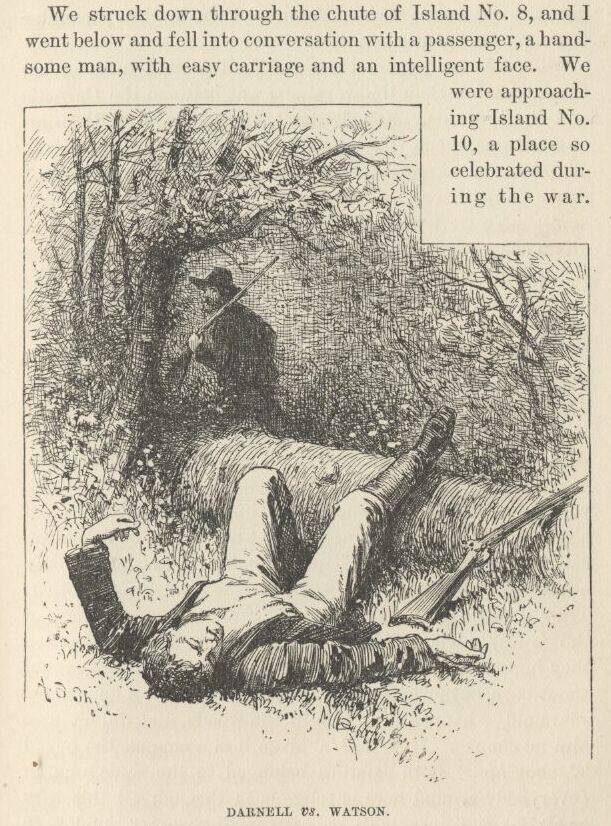

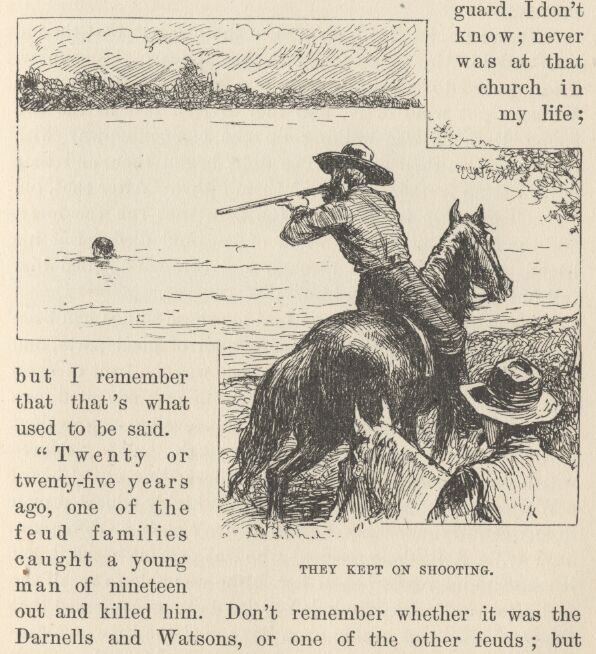

War Talk.—I Tilt over Backwards.—Fifteen Shot-holes.—A Plain

Story.—Wars and Feuds.—Darnell versus Watson.—A Gang and

a Woodpile.—Western Grammar.—River Changes.—New Madrid.

—Floods and Falls.

CHAPTER XXVII.

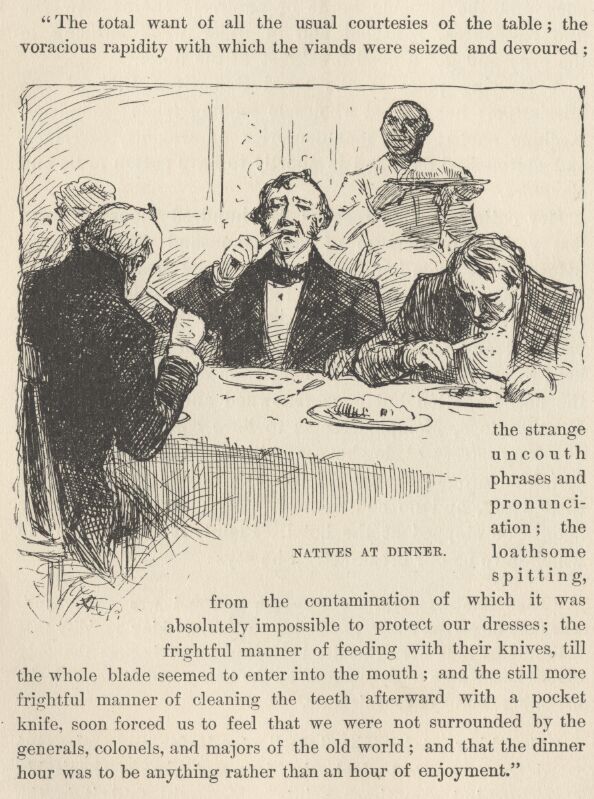

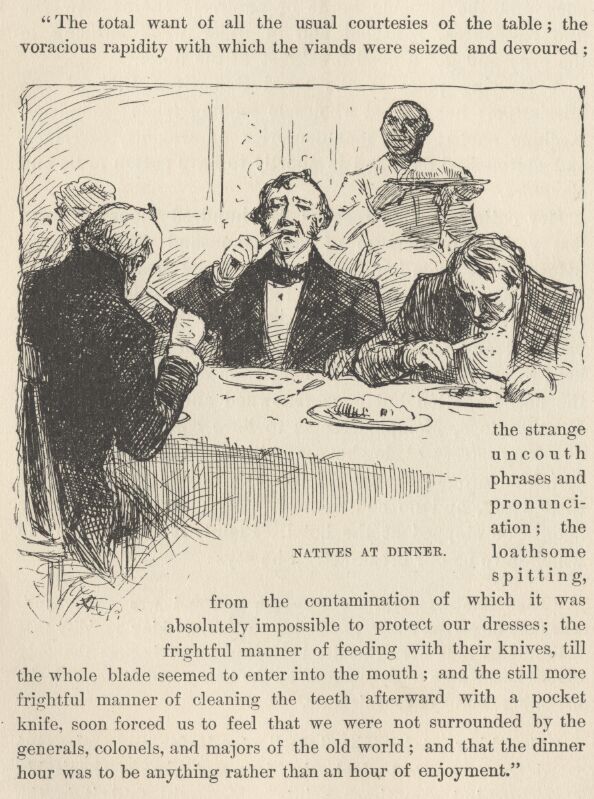

Tourists and their Note-books.—Captain Hall.—Mrs. Trollope’s

Emotions.—Hon. Charles Augustus Murray’s Sentiment.—Captain

Marryat’s Sensations.—Alexander Mackay’s Feelings.

—Mr. Parkman Reports.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

Swinging down the River.—Named for Me.—Plum Point again.

—Lights and Snag Boats.—Infinite Changes.—A Lawless River.

—Changes and Jetties.—Uncle Mumford Testifies.—Pegging the

River.—What the Government does.—The Commission.—Men and

Theories.—“Had them Bad.”—Jews and Prices.

CHAPTER XXIX.

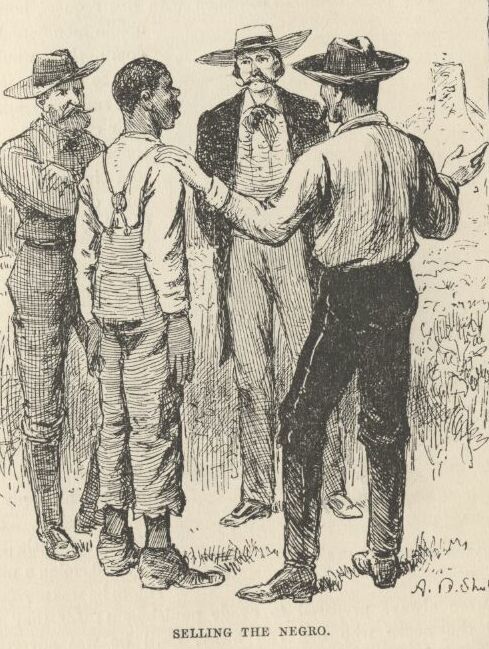

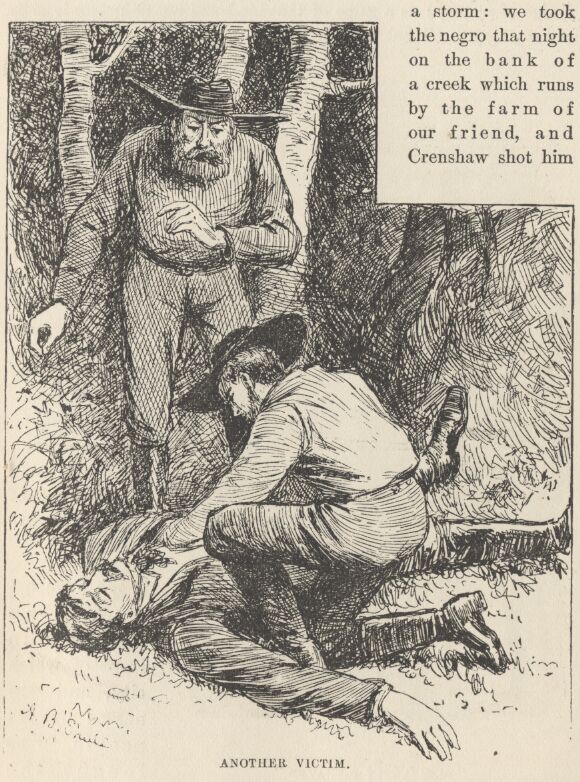

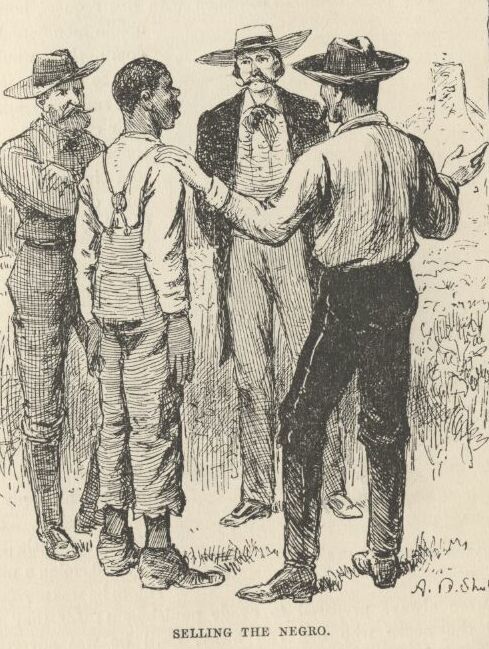

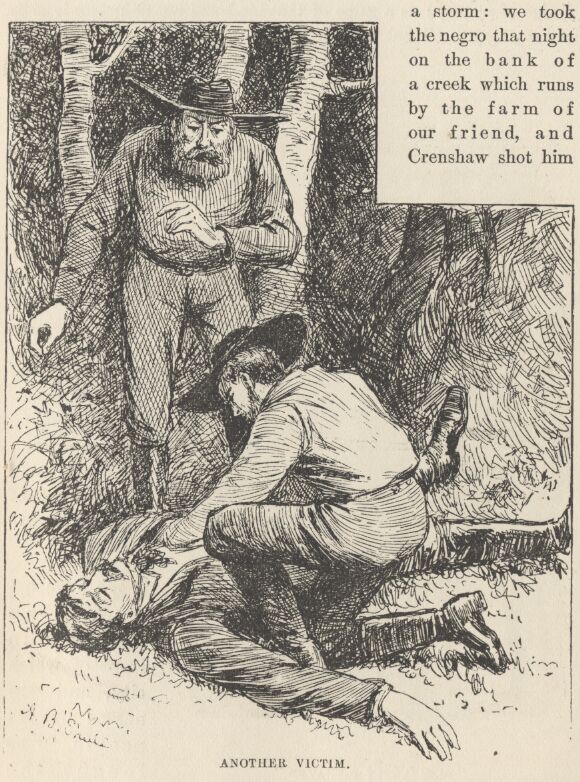

Murel’s Gang.—A Consummate Villain.—Getting Rid of Witnesses.

—Stewart turns Traitor.—I Start a Rebellion.—I get a New Suit

of Clothes.—We Cover our Tracks.—Pluck and Capacity.—A Good

Samaritan City.—The Old and the New.

CHAPTER XXX.

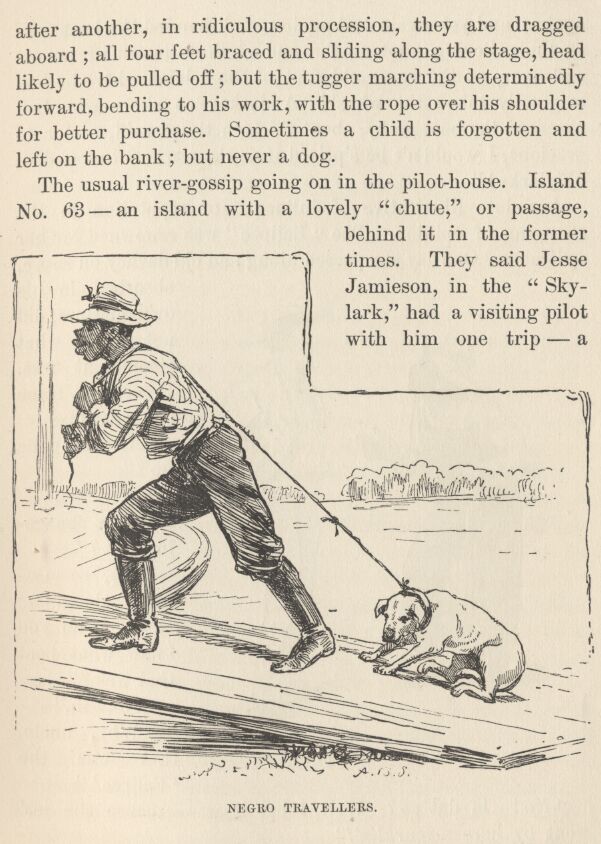

A Melancholy Picture.—On the Move.—River Gossip.—She Went By

a-Sparklin’.—Amenities of Life.—A World of Misinformation.—

Eloquence of Silence.—Striking a Snag.—Photographically Exact.

—Plank Side-walks.

CHAPTER XXXI.

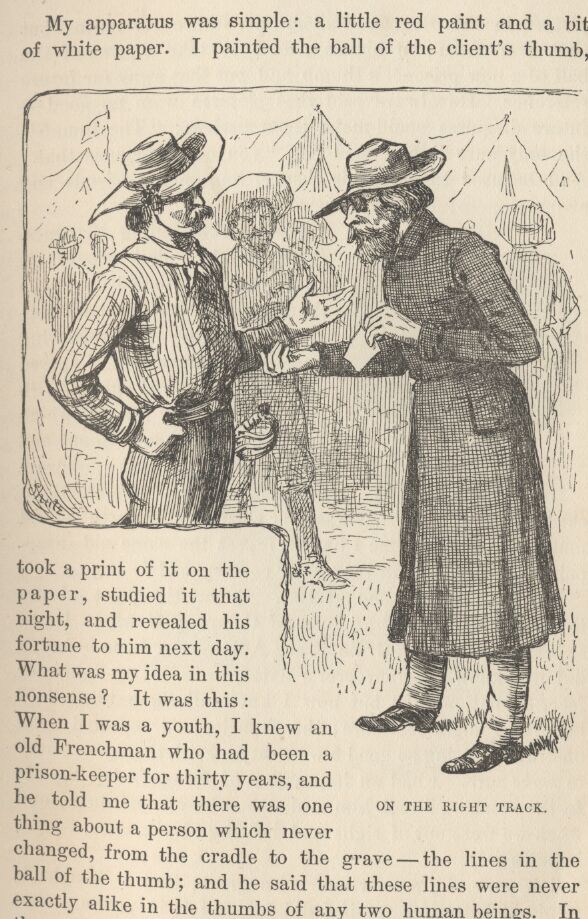

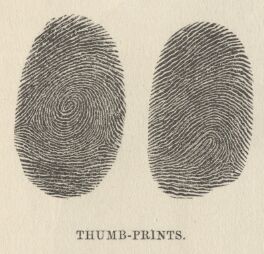

Mutinous Language.—The Dead-house.—Cast-iron German and Flexible

English.—A Dying Man’s Confession.—I am Bound and Gagged.

—I get Myself Free.—I Begin my Search.—The Man with one Thumb.

—Red Paint and White Paper.—He Dropped on his Knees.—Fright

and Gratitude.—I Fled through the Woods.—A Grisly Spectacle.

—Shout, Man, Shout.—A look of Surprise and Triumph.—The Muffled

Gurgle of a Mocking Laugh.—How strangely Things happen.

—The Hidden Money.

CHAPTER XXXII.

Ritter’s Narrative.—A Question of Money.—Napoleon.—Somebody

is Serious.—Where the Prettiest Girl used to Live.

CHAPTER XXXIII.

A Question of Division.—A Place where there was no License.—The

Calhoun Land Company.—A Cotton-planter’s Estimate.—Halifax

and Watermelons.—Jewelled-up Bar-keepers.

CHAPTER XXXIV.

An Austere Man.—A Mosquito Policy.—Facts dressed in Tights.

—A swelled Left Ear.

CHAPTER XXXV.

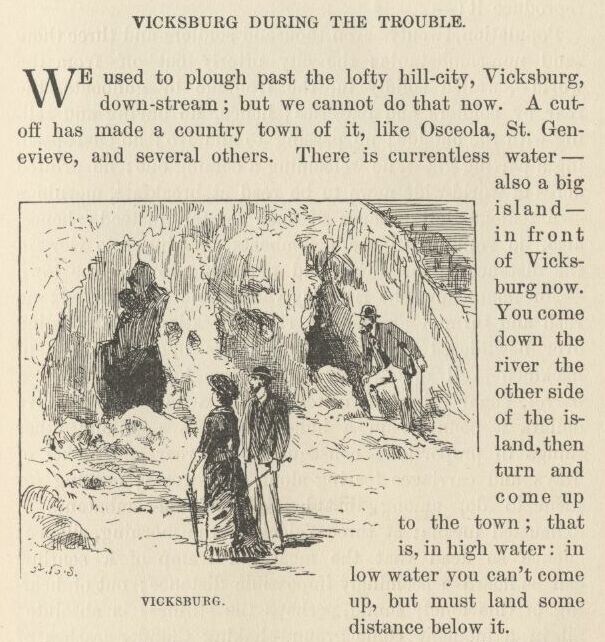

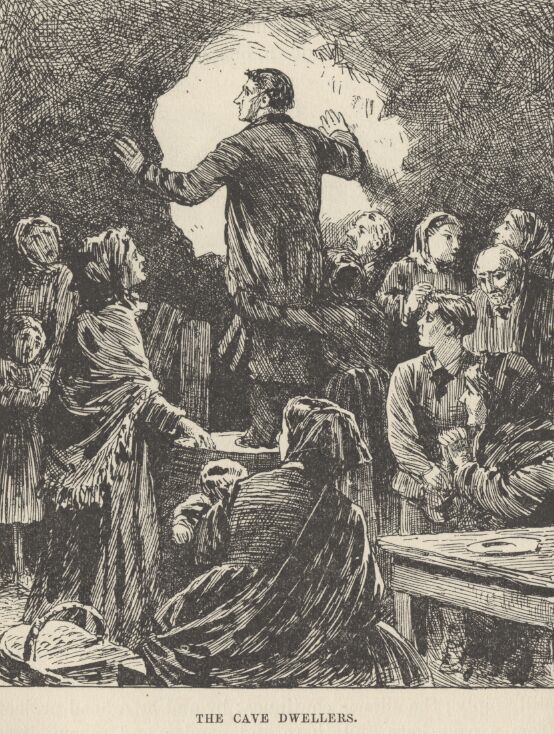

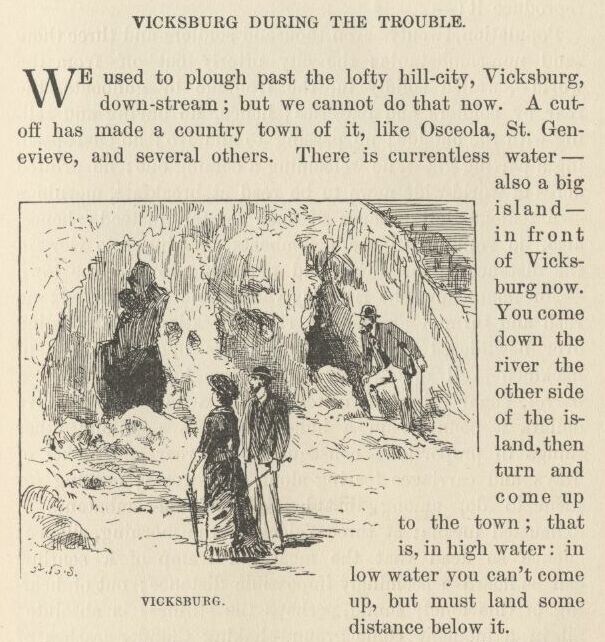

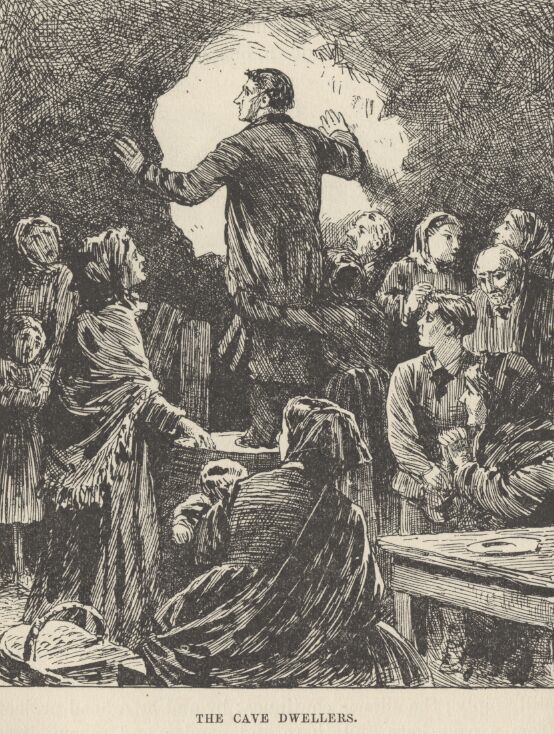

Signs and Scars.—Cannon-thunder Rages.—Cave-dwellers.

—A Continual Sunday.—A ton of Iron and no Glass.—The Ardent

is Saved.—Mule Meat—A National Cemetery.—A Dog and a Shell.

—Railroads and Wealth.—Wharfage Economy.—Vicksburg versus The

"Gold Dust.”—A Narrative in Anticipation.

CHAPTER XXXVI.

The Professor Spins a Yarn.—An Enthusiast in Cattle.—He makes a

Proposition.—Loading Beeves at Acapulco.—He was n’t Raised to it.

—He is Roped In.—His Dull Eyes Lit Up.—Four Aces, you Ass!

—He does n’t Care for the Gores.

CHAPTER XXXVII.

A Terrible Disaster.—The "Gold Dust” explodes her Boilers.

—The End of a Good Man.

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

Mr. Dickens has a Word.—Best Dwellings and their Furniture.—Albums

and Music.—Pantelettes and Conch-shells.—Sugar-candy Rabbits

and Photographs.—Horse-hair Sofas and Snuffers.—Rag Carpets

and Bridal Chambers.

CHAPTER XXXIX.

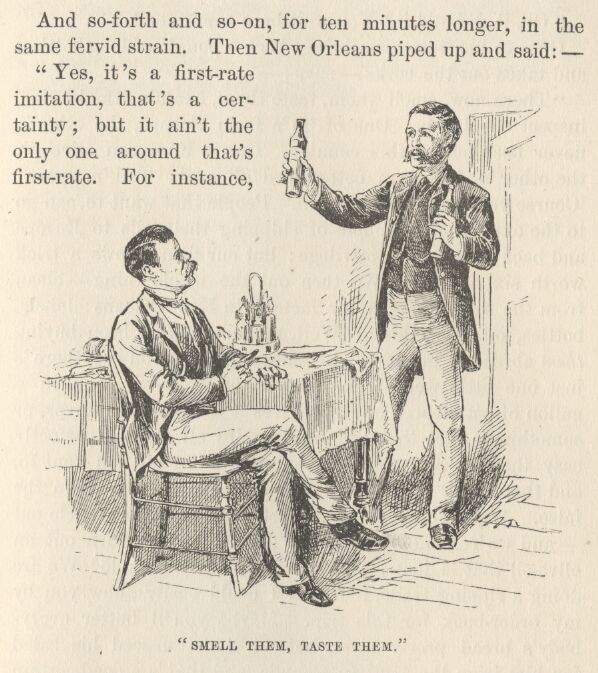

Rowdies and Beauty.—Ice as Jewelry.—Ice Manufacture.—More

Statistics.—Some Drummers.—Oleomargarine versus Butter.

—Olive Oil versus Cotton Seed.—The Answer was not Caught.

—A Terrific Episode.—A Sulphurous Canopy.—The Demons of War.

—The Terrible Gauntlet.

CHAPTER XL.

In Flowers, like a Bride.—A White-washed Castle.—A Southern

Prospectus.—Pretty Pictures.—An Alligator’s Meal.

CHAPTER XLI.

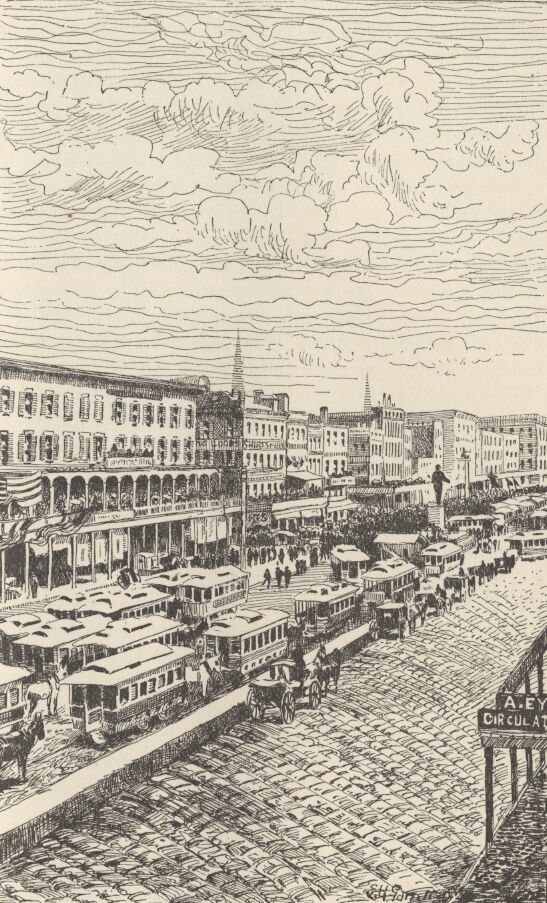

The Approaches to New Orleans.—A Stirring Street.—Sanitary

Improvements.—Journalistic Achievements.—Cisterns and Wells.

CHAPTER XLII.

Beautiful Grave-yards.—Chameleons and Panaceas.—Inhumation and

Infection.—Mortality and Epidemics.—The Cost of Funerals.

CHAPTER XLIII.

I meet an Acquaintance.—Coffins and Swell Houses.—Mrs. O’Flaherty

goes One Better.—Epidemics and Embamming.—Six hundred for a

Good Case.—Joyful High Spirits.

CHAPTER XLIV.

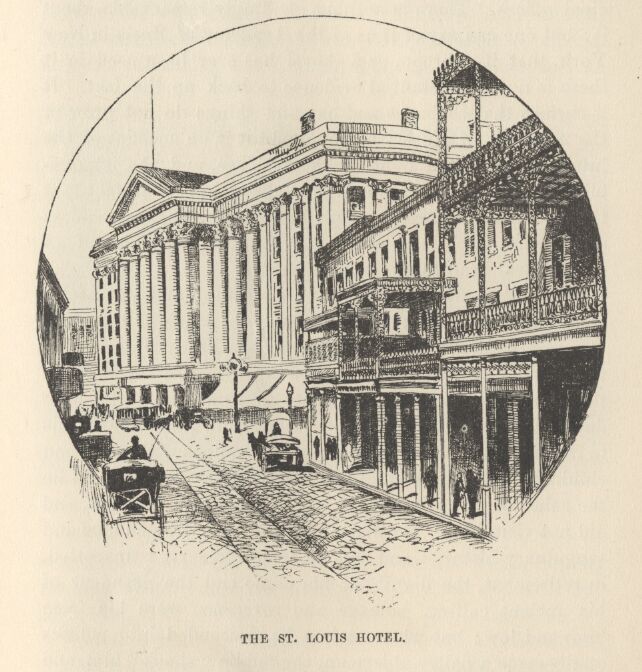

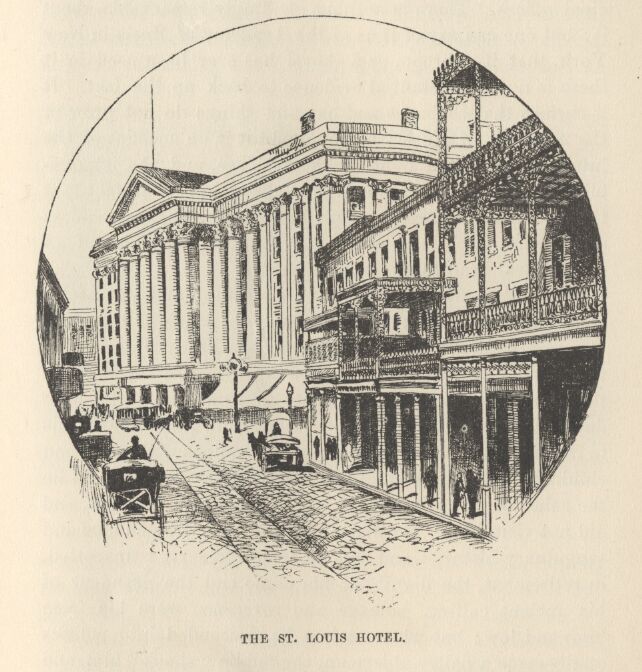

French and Spanish Parts of the City.—Mr. Cable and the Ancient

Quarter.—Cabbages and Bouquets.—Cows and Children.—The Shell

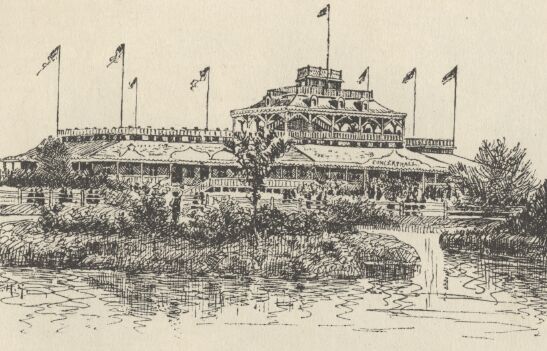

Road. The West End.—A Good Square Meal.—The Pompano.—The Broom-

Brigade.—Historical Painting.—Southern Speech.—Lagniappe.

CHAPTER XLV.

"Waw” Talk.—Cock-Fighting.—Too Much to Bear.—Fine Writing.

—Mule Racing.

CHAPTER XLVI.

Mardi-Gras.—The Mystic Crewe.—Rex and Relics.—Sir Walter Scott.

—A World Set Back.—Titles and Decorations.—A Change.

CHAPTER XLVII.

Uncle Remus.—The Children Disappointed.—We Read Aloud.

—Mr. Cable and Jean au Poquelin.—Involuntary Trespass.—The Gilded

Age.—An Impossible Combination.—The Owner Materializes and Protests.

CHAPTER XLVIII.

Tight Curls and Springy Steps.—Steam-plows.—“No. I.” Sugar.

—A Frankenstein Laugh.—Spiritual Postage.—A Place where there are

no Butchers or Plumbers.—Idiotic Spasms.

CHAPTER XLIX.

Pilot-Farmers.—Working on Shares.—Consequences.—Men who Stick

to their Posts.—He saw what he would do.—A Day after the Fair.

CHAPTER L.

A Patriarch.—Leaves from a Diary.—A Tongue-stopper.—The Ancient

Mariner.—Pilloried in Print.—Petrified Truth.

CHAPTER LI.

A Fresh "Cub” at the Wheel.—A Valley Storm.—Some Remarks on

Construction.—Sock and Buskin.—The Man who never played

Hamlet.—I got Thirsty.—Sunday Statistics.

CHAPTER LII.

I Collar an Idea.—A Graduate of Harvard.—A Penitent Thief.

—His Story in the Pulpit.—Something Symmetrical.—A Literary Artist.

—A Model Epistle.—Pumps again Working.—The "Nub” of the Note.

CHAPTER LIII.

A Masterly Retreat.—A Town at Rest.—Boyhood’s Pranks.—Friends

of my Youth.—The Refuge for Imbeciles.—I am Presented with

my Measure.

CHAPTER LIV.

A Special Judgment.—Celestial Interest.—A Night of Agony.

—Another Bad Attack.—I become Convalescent.—I address a

Sunday-school.—A Model Boy.

CHAPTER LV.

A second Generation.—A hundred thousand Tons of Saddles.—A Dark

and Dreadful Secret.—A Large Family.—A Golden-haired Darling.

—The Mysterious Cross.—My Idol is Broken.—A Bad Season of

Chills and Fever.—An Interesting Cave.

CHAPTER LVI.

Perverted History—A Guilty Conscience.—A Supposititious Case.

—A Habit to be Cultivated.—I Drop my Burden.—Difference in Time.

CHAPTER LVII.

A Model Town.—A Town that Comes up to Blow in the Summer.

—The Scare-crow Dean.—Spouting Smoke and Flame.—An Atmosphere

that tastes good.—The Sunset Land.

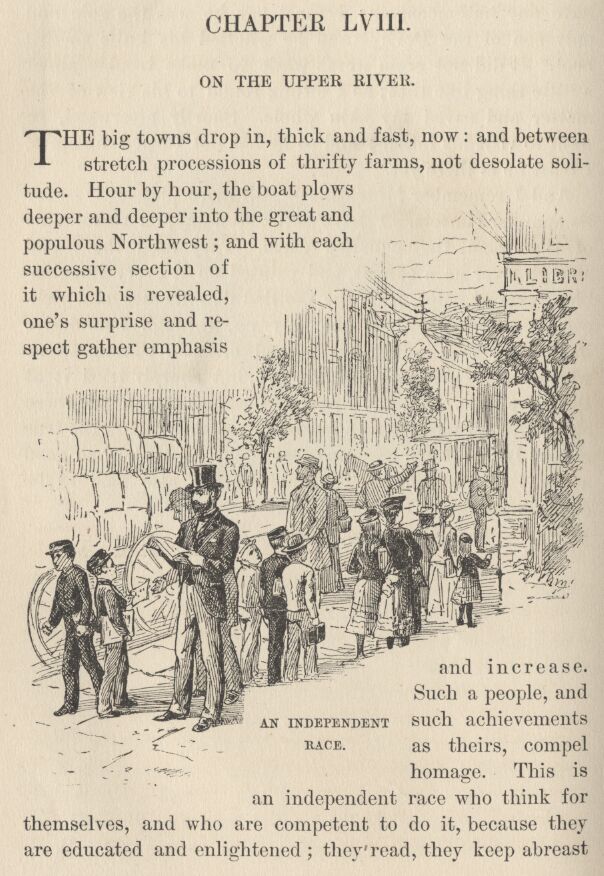

CHAPTER LVIII.

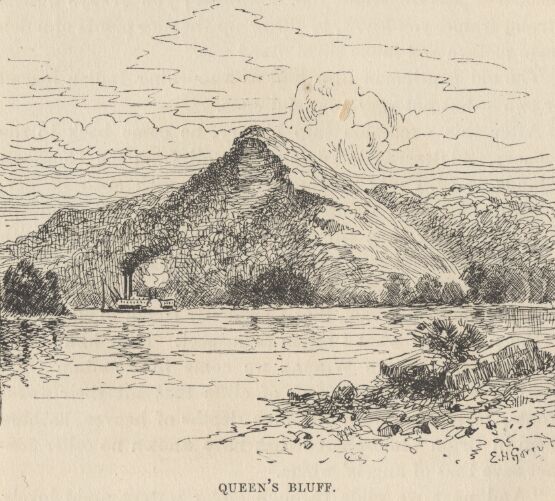

An Independent Race.—Twenty-four-hour Towns.—Enchanting Scenery.

—The Home of the Plow.—Black Hawk.—Fluctuating Securities.

—A Contrast.—Electric Lights.

CHAPTER LIX.

Indian Traditions and Rattlesnakes.—A Three-ton Word.—Chimney

Rock.—The Panorama Man.—A Good Jump.—The Undying Head.

—Peboan and Seegwun.

CHAPTER LX.

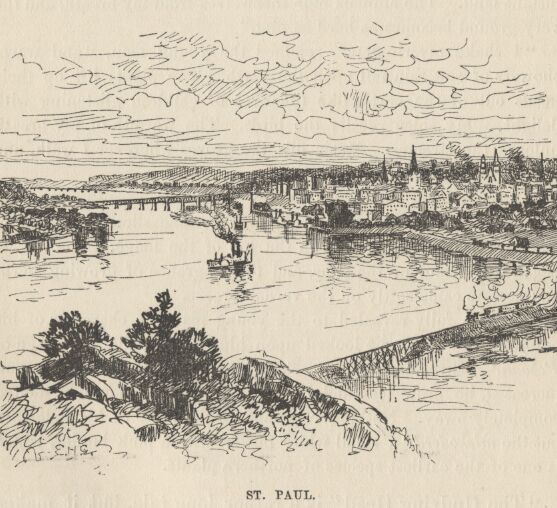

The Head of Navigation.—From Roses to Snow.—Climatic Vaccination.

—A Long Ride.—Bones of Poverty.—The Pioneer of Civilization.

—Jug of Empire.—Siamese Twins.—The Sugar-bush.—He Wins his Bride.

—The Mystery about the Blanket.—A City that is always a Novelty.

—Home again.

APPENDIX.

A

B

C

D

THE “BODY OF THE NATION”

BUT the basin of the Mississippi is the

Body of the Nation.

All the other parts are but members, important in themselves, yet

more important in their relations to this. Exclusive of the Lake

basin and of 300,000 square miles in Texas and New Mexico, which

in many aspects form a part of it, this basin contains about

1,250,000 square miles. In extent it is the second great valley

of the world, being exceeded only by that of the Amazon. The

valley of the frozen Obi approaches it in extent; that of La

Plata comes next in space, and probably in habitable capacity,

having about

8⁄9 of its area; then comes that of the

Yenisei, with about

7⁄9;

the Lena, Amoor, Hoang-ho,

Yang-tse-kiang, and Nile,

5⁄9; the Ganges, less than

1⁄2; the Indus, less than

1⁄3; the Euphrates,

1⁄5; the Rhine,

1⁄15.

It exceeds in extent the

whole of Europe, exclusive of Russia, Norway, and Sweden.

It

would contain Austria four times, Germany or Spain five times,

France six times, the British Islands or Italy ten times.

Conceptions formed from the river-basins of Western Europe are

rudely shocked when we consider the extent of the valley of the

Mississippi; nor are those formed from the sterile basins of the

great rivers of Siberia, the lofty plateaus of Central Asia, or

the mighty sweep of the swampy Amazon more adequate. Latitude,

elevation, and rainfall all combine to render every part of the

Mississippi Valley capable of supporting a dense population.

As a dwelling-place for civilized man it is by

far the first upon our globe. —

Editor’s Table,

Harper’s Magazine, February, 1863.

Chapter I

The River and Its History

THE Mississippi is well worth reading about. It is not a

commonplace river, but on the contrary is in all ways remarkable.

Considering the Missouri its main branch, it is the longest river

in the world—four thousand three hundred miles. It seems safe to

say that it is also the crookedest river in the world, since in

one part of its journey it uses up one thousand three hundred

miles to cover the same ground that the crow would fly over in

six hundred and seventy-five. It discharges three times as much

water as the St. Lawrence, twenty-five times as much as the

Rhine, and three hundred and thirty-eight times as much as the

Thames. No other river has so vast a drainage-basin: it draws its

water supply from twenty-eight States and Territories; from

Delaware, on the Atlantic seaboard, and from all the country

between that and Idaho on the Pacific slope—a spread of

forty-five degrees of longitude. The Mississippi receives and

carries to the Gulf water from fifty-four subordinate rivers that

are navigable by steamboats, and from some hundreds that are

navigable by flats and keels. The area of its drainage-basin is

as great as the combined areas of England, Wales, Scotland,

Ireland, France, Spain, Portugal, Germany, Austria, Italy, and

Turkey; and almost all this wide region is fertile; the

Mississippi valley, proper, is exceptionally so.

It is a remarkable river in this: that instead of widening

toward its mouth, it grows narrower; grows narrower and deeper.

From the junction of the Ohio to a point half way down to the

sea, the width averages a mile in high water: thence to the sea

the width steadily diminishes, until, at the “Passes,” above the

mouth, it is but little over half a mile. At the junction of the

Ohio the Mississippi’s depth is eighty-seven feet; the depth

increases gradually, reaching one hundred and twenty-nine just

above the mouth.

The difference in rise and fall is also remarkable—not in the

upper, but in the lower river. The rise is tolerably uniform down

to Natchez (three hundred and sixty miles above the mouth)—about

fifty feet. But at Bayou La Fourche the river rises only

twenty-four feet; at New Orleans only fifteen, and just above the

mouth only two and one half.

An article in the New Orleans “Times-Democrat,” based upon

reports of able engineers, states that the river annually empties

four hundred and six million tons of mud into the Gulf of

Mexico—which brings to mind Captain Marryat’s rude name for the

Mississippi—“the Great Sewer.” This mud, solidified, would make

a mass a mile square and two hundred and forty-one feet high.

The mud deposit gradually extends the land—but only

gradually; it has extended it not quite a third of a mile in the

two hundred years which have elapsed since the river took its

place in history. The belief of the scientific people is, that

the mouth used to be at Baton Rouge, where the hills cease, and

that the two hundred miles of land between there and the Gulf was

built by the river. This gives us the age of that piece of

country, without any trouble at all—one hundred and twenty

thousand years. Yet it is much the youthfullest batch of country

that lies around there anywhere.

The Mississippi is remarkable in still another way—its

disposition to make prodigious jumps by cutting through narrow

necks of land, and thus straightening and shortening itself. More

than once it has shortened itself thirty miles at a single jump!

These cut-offs have had curious effects: they have thrown several

river towns out into the rural districts, and built up sand bars

and forests in front of them. The town of Delta used to be three

miles below Vicksburg: a recent cutoff has radically changed the

position, and Delta is now

two miles above

Vicksburg.

Both of these river towns have been retired to the country by

that cut-off. A cut-off plays havoc with boundary lines and

jurisdictions: for instance, a man is living in the State of

Mississippi to-day, a cut-off occurs to-night, and to-morrow the

man finds himself and his land over on the other side of the

river, within the boundaries and subject to the laws of the State

of Louisiana! Such a thing, happening in the upper river in the

old times, could have transferred a slave from Missouri to

Illinois and made a free man of him.

The Mississippi does not alter its locality by cut-offs alone:

it is always changing its habitat bodily—is always moving bodily

sidewise. At Hard Times, La., the river is two miles west of the

region it used to occupy. As a result, the original site of that

settlement is not now in Louisiana at all, but on the other side

of the river, in the State of Mississippi.

Nearly the whole of that

one thousand three hundred miles of old Mississippi River

which La Salle floated down in his canoes, two hundred years

ago, is good solid dry ground now.

The river lies to the right of it,

in places, and to the left of it in other places.

Although the Mississippi’s mud builds land but slowly, down at

the mouth, where the Gulfs billows interfere with its work, it

builds fast enough in better protected regions higher up: for

instance, Prophet’s Island contained one thousand five hundred

acres of land thirty years ago; since then the river has added

seven hundred acres to it.

But enough of these examples of the mighty stream’s

eccentricities for the present—I will give a few more of them

further along in the book.

Let us drop the Mississippi’s physical history, and say a word

about its historical history—so to speak. We can glance briefly

at its slumbrous first epoch in a couple of short chapters; at

its second and wider-awake epoch in a couple more; at its

flushest and widest-awake epoch in a good many succeeding

chapters; and then talk about its comparatively tranquil present

epoch in what shall be left of the book.

The world and the books are so accustomed to use, and

over-use, the word “new” in connection with our country, that we

early get and permanently retain the impression that there is

nothing old about it. We do of course know that there are several

comparatively old dates in American history, but the mere figures

convey to our minds no just idea, no distinct realization, of the

stretch of time which they represent. To say that De Soto, the

first white man who ever saw the Mississippi River, saw it in

1542, is a remark which states a fact without interpreting it: it

is something like giving the dimensions of a sunset by

astronomical measurements, and cataloguing the colors by their

scientific names;—as a result, you get the bald fact of the

sunset, but you don’t see the sunset. It would have been better

to paint a picture of it.

The date 1542, standing by itself, means little or nothing to

us; but when one groups a few neighboring historical dates and

facts around it, he adds perspective and color, and then realizes

that this is one of the American dates which is quite respectable

for age.

For instance, when the Mississippi was first seen by a white

man, less than a quarter of a century had elapsed since Francis I.’s defeat at Pavia; the death of Raphael; the death of Bayard,

sans peur et sans reproche; the driving out of the

Knights-Hospitallers from Rhodes by the Turks; and the placarding

of the Ninety-Five Propositions,—the act which began the

Reformation. When De Soto took his glimpse of the river, Ignatius

Loyola was an obscure name; the order of the Jesuits was not yet

a year old; Michael Angelo’s paint was not yet dry on the Last

Judgment in the Sistine Chapel; Mary Queen of Scots was not yet

born, but would be before the year closed. Catherine de Medici

was a child; Elizabeth of England was not yet in her teens;

Calvin, Benvenuto Cellini, and the Emperor Charles V. were at the

top of their fame, and each was manufacturing history after his

own peculiar fashion; Margaret of Navarre was writing the

“Heptameron” and some religious books,—the first survives, the

others are forgotten, wit and indelicacy being sometimes better

literature preservers than holiness; lax court morals and the

absurd chivalry business were in full feather, and the joust and

the tournament were the frequent pastime of titled fine gentlemen

who could fight better than they could spell, while religion was

the passion of their ladies, and classifying their offspring into

children of full rank and children by brevet their pastime.

In fact, all around, religion was in a peculiarly blooming

condition: the Council of Trent was being called; the Spanish

Inquisition was roasting, and racking, and burning, with a free

hand; elsewhere on the continent the nations were being persuaded

to holy living by the sword and fire; in England, Henry VIII. had

suppressed the monasteries, burnt Fisher and another bishop or

two, and was getting his English reformation and his harem

effectively started. When De Soto stood on the banks of the

Mississippi, it was still two years before Luther’s death; eleven

years before the burning of Servetus; thirty years before the St.

Bartholomew slaughter; Rabelais was not yet published; “Don

Quixote” was not yet written; Shakespeare was not yet born; a

hundred long years must still elapse before Englishmen would hear

the name of Oliver Cromwell.

Unquestionably the discovery of the Mississippi is a datable

fact which considerably mellows and modifies the shiny newness of

our country, and gives her a most respectable outside-aspect of

rustiness and antiquity.

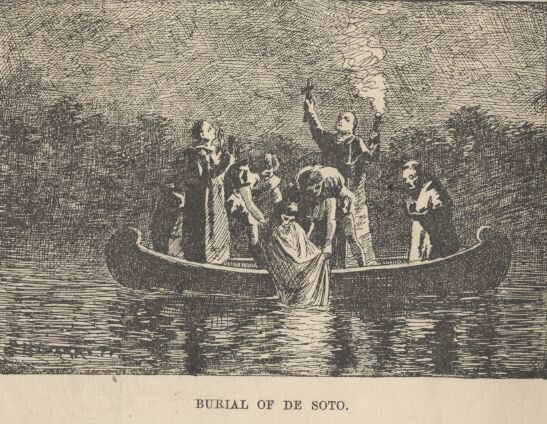

De Soto merely glimpsed the river, then died and was buried in

it by his priests and soldiers. One would expect the priests and

the soldiers to multiply the river’s dimensions by ten—the

Spanish custom of the day—and thus move other adventurers to go

at once and explore it. On the contrary, their narratives when

they reached home, did not excite that amount of curiosity. The

Mississippi was left unvisited by whites during a term of years

which seems incredible in our energetic days. One may “sense” the

interval to his mind, after a fashion, by dividing it up in this

way: After De Soto glimpsed the river, a fraction short of a

quarter of a century elapsed, and then Shakespeare was born;

lived a trifle more than half a century, then died; and when he

had been in his grave considerably more than half a century, the

second white man saw the Mississippi. In our day we don’t allow a

hundred and thirty years to elapse between glimpses of a marvel.

If somebody should discover a creek in the county next to the one

that the North Pole is in, Europe and America would start fifteen

costly expeditions thither: one to explore the creek, and the

other fourteen to hunt for each other.

For more than a hundred and fifty years there had been white

settlements on our Atlantic coasts. These people were in intimate

communication with the Indians: in the south the Spaniards were

robbing, slaughtering, enslaving and converting them; higher up,

the English were trading beads and blankets to them for a

consideration, and throwing in civilization and whiskey, “for

lagniappe;” and in Canada the French were schooling them in a

rudimentary way, missionarying among them, and drawing whole

populations of them at a time to Quebec, and later to Montreal,

to buy furs of them. Necessarily, then, these various clusters of

whites must have heard of the great river of the far west; and

indeed, they did hear of it vaguely,—so vaguely and

indefinitely, that its course, proportions, and locality were

hardly even guessable. The mere mysteriousness of the matter

ought to have fired curiosity and compelled exploration; but this

did not occur. Apparently nobody happened to want such a river,

nobody needed it, nobody was curious about it; so, for a century

and a half the Mississippi remained out of the market and

undisturbed. When De Soto found it, he was not hunting for a

river, and had no present occasion for one; consequently he did

not value it or even take any particular notice of it.

But at last La Salle the Frenchman conceived the idea of

seeking out that river and exploring it. It always happens that

when a man seizes upon a neglected and important idea, people

inflamed with the same notion crop up all around. It happened so

in this instance.

Naturally the question suggests itself, Why did these people

want the river now when nobody had wanted it in the five

preceding generations? Apparently it was because at this late day

they thought they had discovered a way to make it useful; for it

had come to be believed that the Mississippi emptied into the

Gulf of California, and therefore afforded a short cut from

Canada to China. Previously the supposition had been that it

emptied into the Atlantic, or Sea of Virginia.

Chapter 2

The River and Its Explorers

LA SALLE

himself sued for certain high privileges, and they

were graciously accorded him by Louis XIV of inflated memory.

Chief among them was the privilege to explore, far and wide, and

build forts, and stake out continents, and hand the same over to

the king, and pay the expenses himself; receiving, in return,

some little advantages of one sort or another; among them the

monopoly of buffalo hides. He spent several years and about all

of his money, in making perilous and painful trips between

Montreal and a fort which he had built on the Illinois, before he

at last succeeded in getting his expedition in such a shape that

he could strike for the Mississippi.

And meantime other parties had had better fortune. In 1673

Joliet the merchant, and Marquette the priest, crossed the

country and reached the banks of the Mississippi. They went by

way of the Great Lakes; and from Green Bay, in canoes, by way of

Fox River and the Wisconsin. Marquette had solemnly contracted,

on the feast of the Immaculate Conception, that if the Virgin

would permit him to discover the great river, he would name it

Conception, in her honor. He kept his word. In that day, all

explorers traveled with an outfit of priests. De Soto had

twenty-four with him. La Salle had several, also. The expeditions

were often out of meat, and scant of clothes, but they always had

the furniture and other requisites for the mass; they were always

prepared, as one of the quaint chroniclers of the time phrased

it, to “explain hell to the savages.”

On the 17th of June, 1673, the canoes of Joliet and Marquette

and their five subordinates reached the junction of the Wisconsin

with the Mississippi. Mr. Parkman says: “Before them a wide and

rapid current coursed athwart their way, by the foot of lofty

heights wrapped thick in forests.” He continues: “Turning

southward, they paddled down the stream, through a solitude

unrelieved by the faintest trace of man.”

A big cat-fish collided with Marquette’s canoe, and startled

him; and reasonably enough, for he had been warned by the Indians

that he was on a foolhardy journey, and even a fatal one, for the

river contained a demon “whose roar could be heard at a great

distance, and who would engulf them in the abyss where he dwelt.”

I have seen a Mississippi cat-fish that was more than six feet

long, and weighed two hundred and fifty pounds; and if

Marquette’s fish was the fellow to that one, he had a fair right

to think the river’s roaring demon was come.

“At length the buffalo began to appear, grazing in herds on

the great prairies which then bordered the river; and Marquette

describes the fierce and stupid look of the old bulls as they

stared at the intruders through the tangled mane which nearly

blinded them.”

The voyagers moved cautiously: “Landed at night and made a

fire to cook their evening meal; then extinguished it, embarked

again, paddled some way farther, and anchored in the stream,

keeping a man on the watch till morning.”

They did this day after day and night after night; and at the

end of two weeks they had not seen a human being. The river was

an awful solitude, then. And it is now, over most of its

stretch.

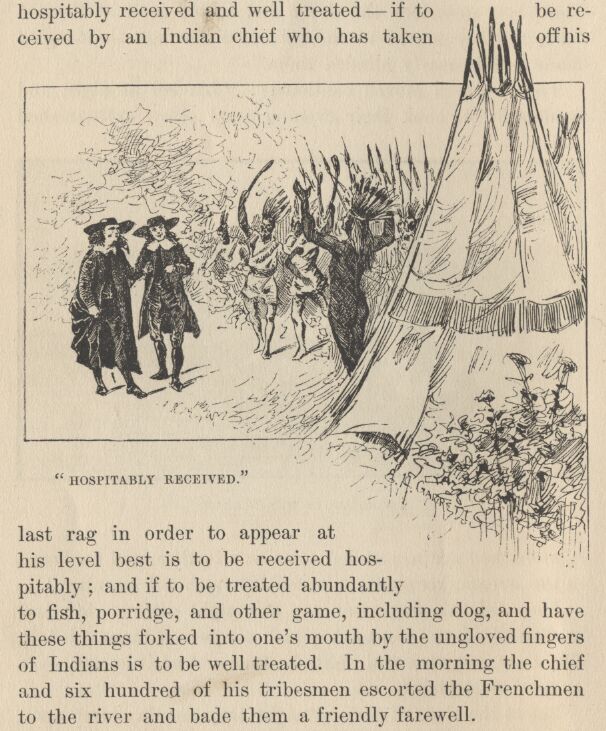

But at the close of the fortnight they one day came upon the

footprints of men in the mud of the western bank—a Robinson

Crusoe experience which carries an electric shiver with it yet,

when one stumbles on it in print. They had been warned that the

river Indians were as ferocious and pitiless as the river demon,

and destroyed all comers without waiting for provocation; but no

matter, Joliet and Marquette struck into the country to hunt up

the proprietors of the tracks. They found them, by and by, and

were hospitably received and well treated—if to be received by

an Indian chief who has taken off his last rag in order to appear

at his level best is to be received hospitably; and if to be

treated abundantly to fish, porridge, and other game, including

dog, and have these things forked into one’s mouth by the

ungloved fingers of Indians is to be well treated. In the morning

the chief and six hundred of his tribesmen escorted the Frenchmen

to the river and bade them a friendly farewell.

On the rocks above the present city of Alton they found some

rude and fantastic Indian paintings, which they describe. A short

distance below “a torrent of yellow mud rushed furiously athwart

the calm blue current of the Mississippi, boiling and surging and

sweeping in its course logs, branches, and uprooted trees.” This

was the mouth of the Missouri, “that savage river,” which

“descending from its mad career through a vast unknown of

barbarism, poured its turbid floods into the bosom of its gentle

sister.”

By and by they passed the mouth of the Ohio; they passed

cane-brakes; they fought mosquitoes; they floated along, day

after day, through the deep silence and loneliness of the river,

drowsing in the scant shade of makeshift awnings, and broiling

with the heat; they encountered and exchanged civilities with

another party of Indians; and at last they reached the mouth of

the Arkansas (about a month out from their starting-point), where

a tribe of war-whooping savages swarmed out to meet and murder

them; but they appealed to the Virgin for help; so in place of a

fight there was a feast, and plenty of pleasant palaver and

fol-de-rol.

They had proved to their satisfaction, that the Mississippi

did not empty into the Gulf of California, or into the Atlantic.

They believed it emptied into the Gulf of Mexico. They turned

back, now, and carried their great news to Canada.

But belief is not proof. It was reserved for La Salle to

furnish the proof. He was provokingly delayed, by one misfortune

after another, but at last got his expedition under way at the

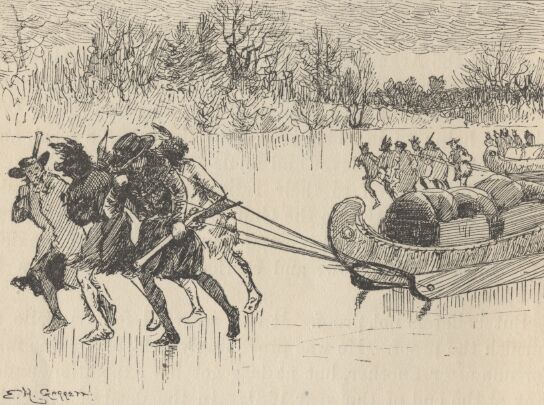

end of the year 1681. In the dead of winter he and Henri de

Tonty, son of Lorenzo Tonty, who invented the tontine, his

lieutenant, started down the Illinois, with a following of

eighteen Indians brought from New England, and twenty-three

Frenchmen. They moved in procession down the surface of the

frozen river, on foot, and dragging their canoes after them on

sledges.

At Peoria Lake they struck open water, and paddled thence to

the Mississippi and turned their prows southward. They plowed

through the fields of floating ice, past the mouth of the

Missouri; past the mouth of the Ohio, by-and-by; “and, gliding by

the wastes of bordering swamp, landed on the 24th of February

near the Third Chickasaw Bluffs,” where they halted and built

Fort Prudhomme.

“Again,” says Mr. Parkman, “they embarked; and with every

stage of their adventurous progress, the mystery of this vast new

world was more and more unveiled. More and more they entered the

realms of spring. The hazy sunlight, the warm and drowsy air, the

tender foliage, the opening flowers, betokened the reviving life

of nature.”

Day by day they floated down the great bends, in the shadow of

the dense forests, and in time arrived at the mouth of the

Arkansas. First, they were greeted by the natives of this

locality as Marquette had before been greeted by them—with the

booming of the war drum and the flourish of arms. The Virgin

composed the difficulty in Marquette’s case; the pipe of peace

did the same office for La Salle. The white man and the red man

struck hands and entertained each other during three days. Then,

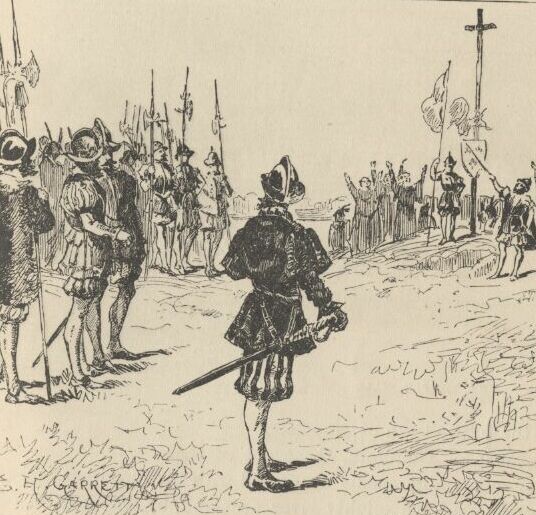

to the admiration of the savages, La Salle set up a cross with

the arms of France on it, and took possession of the whole

country for the king—the cool fashion of the time—while the

priest piously consecrated the robbery with a hymn. The priest

explained the mysteries of the faith “by signs,” for the saving

of the savages; thus compensating them with possible possessions

in Heaven for the certain ones on earth which they had just been

robbed of. And also, by signs, La Salle drew from these simple

children of the forest acknowledgments of fealty to Louis the

Putrid, over the water. Nobody smiled at these colossal

ironies.

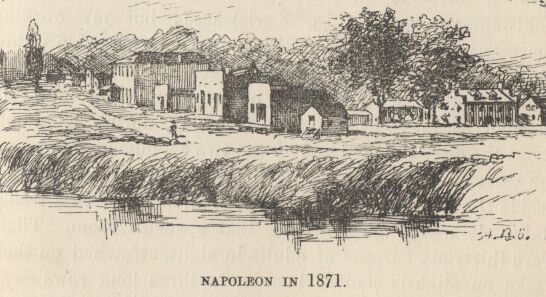

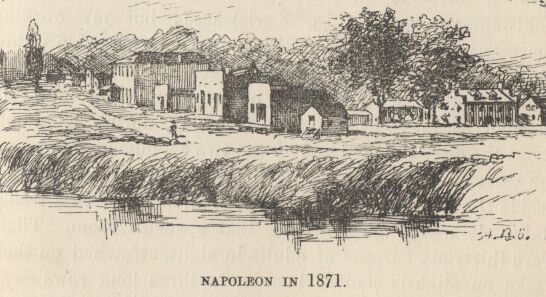

These performances took place on the site of the future town

of Napoleon, Arkansas, and there the first confiscation-cross was

raised on the banks of the great river. Marquette’s and Joliet’s

voyage of discovery ended at the same spot—the site of the

future town of Napoleon. When De Soto took his fleeting glimpse

of the river, away back in the dim early days, he took it from

that same spot—the site of the future town of Napoleon,

Arkansas. Therefore, three out of the four memorable events

connected with the discovery and exploration of the mighty river,

occurred, by accident, in one and the same place. It is a most

curious distinction, when one comes to look at it and think about

it. France stole that vast country on that spot, the future

Napoleon; and by and by Napoleon himself was to give the country

back again!—make restitution, not to the owners, but to their

white American heirs.

The voyagers journeyed on, touching here and there; “passed

the sites, since become historic, of Vicksburg and Grand Gulf,”

and visited an imposing Indian monarch in the Teche country,

whose capital city was a substantial one of sun-baked bricks

mixed with straw—better houses than many that exist there now.

The chiefs house contained an audience room forty feet square;

and there he received Tonty in State, surrounded by sixty old men

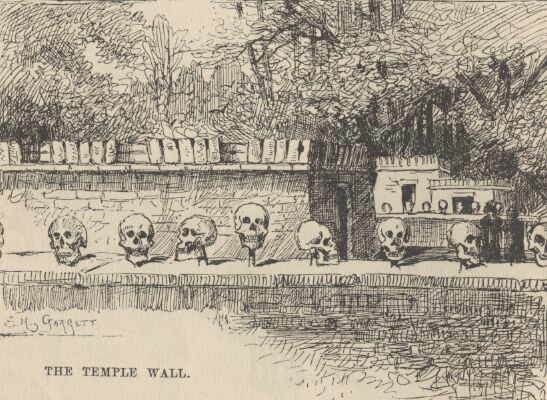

clothed in white cloaks. There was a temple in the town, with a

mud wall about it ornamented with skulls of enemies sacrificed to

the sun.

The voyagers visited the Natchez Indians, near the site of the

present city of that name, where they found a “religious and

political despotism, a privileged class descended from the sun, a

temple and a sacred fire.” It must have been like getting home

again; it was home with an advantage, in fact, for it lacked

Louis XIV.

A few more days swept swiftly by, and La Salle stood in the

shadow of his confiscating cross, at the meeting of the waters

from Delaware, and from Itaska, and from the mountain ranges

close upon the Pacific, with the waters of the Gulf of Mexico,

his task finished, his prodigy achieved. Mr. Parkman, in closing

his fascinating narrative, thus sums up:

“On that day, the realm of France received on parchment a

stupendous accession. The fertile plains of Texas; the vast basin

of the Mississippi, from its frozen northern springs to the

sultry borders of the Gulf; from the woody ridges of the

Alleghanies to the bare peaks of the Rocky Mountains—a region of

savannas and forests, sun-cracked deserts and grassy prairies,

watered by a thousand rivers, ranged by a thousand warlike

tribes, passed beneath the scepter of the Sultan of Versailles;

and all by virtue of a feeble human voice, inaudible at half a

mile.”

Chapter 3

Frescoes from the Past

APPARENTLY

the river was ready for business, now. But no, the

distribution of a population along its banks was as calm and

deliberate and time-devouring a process as the discovery and

exploration had been.

Seventy years elapsed, after the exploration, before the

river’s borders had a white population worth considering; and

nearly fifty more before the river had a commerce. Between La

Salle’s opening of the river and the time when it may be said to

have become the vehicle of anything like a regular and active

commerce, seven sovereigns had occupied the throne of England,

America had become an independent nation, Louis XIV. and Louis

XV. had rotted and died, the French monarchy had gone down in the

red tempest of the revolution, and Napoleon was a name that was

beginning to be talked about. Truly, there were snails in those

days.

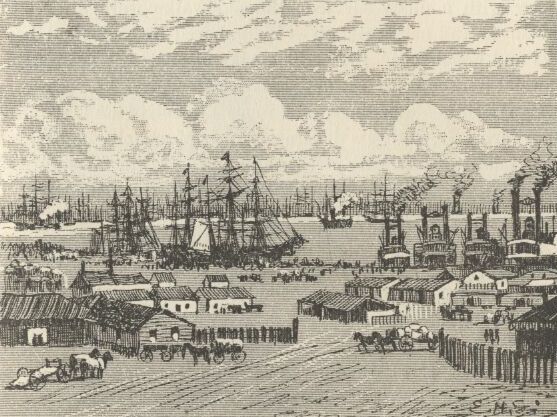

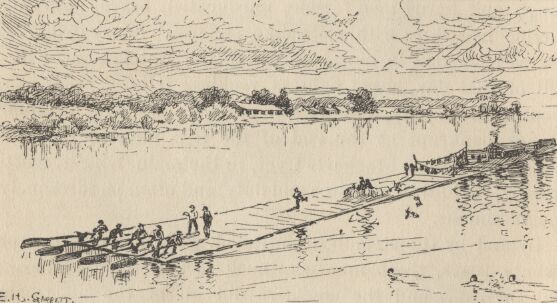

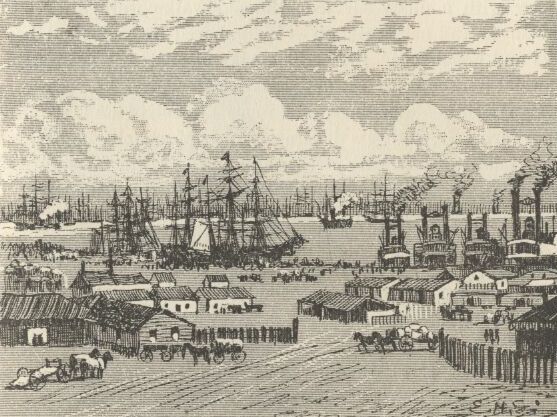

The river’s earliest commerce was in great barges—keelboats,

broadhorns. They floated and sailed from the upper rivers to New

Orleans, changed cargoes there, and were tediously warped and

poled back by hand. A voyage down and back sometimes occupied

nine months. In time this commerce increased until it gave

employment to hordes of rough and hardy men; rude, uneducated,

brave, suffering terrific hardships with sailor-like stoicism;

heavy drinkers, coarse frolickers in moral sties like the

Natchez-under-the-hill of that day, heavy fighters, reckless

fellows, every one, elephantinely jolly, foul-witted, profane;

prodigal of their money, bankrupt at the end of the trip, fond of

barbaric finery, prodigious braggarts; yet, in the main, honest,

trustworthy, faithful to promises and duty, and often

picturesquely magnanimous.

By and by the steamboat intruded. Then for fifteen or twenty

years, these men continued to run their keelboats down-stream,

and the steamers did all of the upstream business, the

keelboatmen selling their boats in New Orleans, and returning

home as deck passengers in the steamers.

But after a while the steamboats so increased in number and in

speed that they were able to absorb the entire commerce; and then

keelboating died a permanent death. The keelboatman became a deck

hand, or a mate, or a pilot on the steamer; and when

steamer-berths were not open to him, he took a berth on a

Pittsburgh coal-flat, or on a pine-raft constructed in the

forests up toward the sources of the Mississippi.

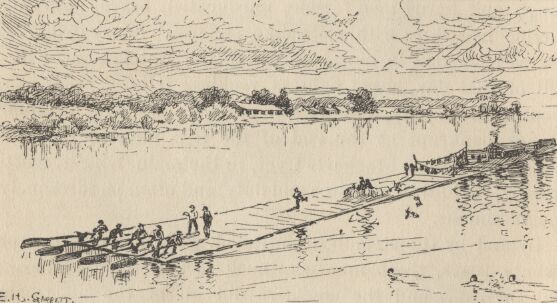

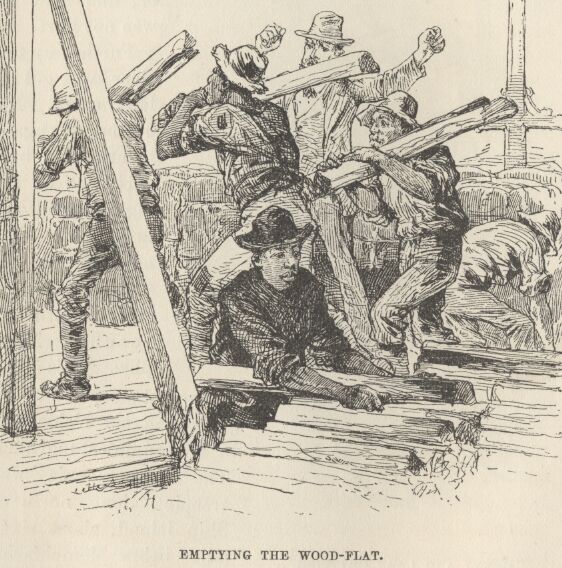

In the heyday of the steamboating prosperity, the river from

end to end was flaked with coal-fleets and timber rafts, all

managed by hand, and employing hosts of the rough characters whom

I have been trying to describe. I remember the annual processions

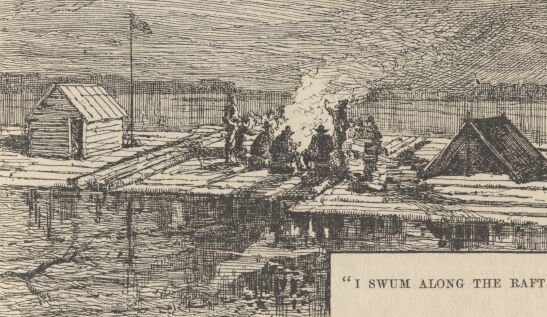

of mighty rafts that used to glide by Hannibal when I was a

boy,—an acre or so of white, sweet-smelling boards in each

raft, a crew of two dozen men or more, three or four wigwams

scattered about the raft’s vast level space for

storm-quarters,—and I remember the rude ways and the tremendous

talk

of their big crews, the ex-keelboatmen and their admiringly

patterning successors; for we used to swim out a quarter or third

of a mile and get on these rafts and have a ride.

By way of illustrating keelboat talk and manners, and that

now-departed and hardly-remembered raft-life, I will throw in, in

this place, a chapter from a book which I have been working at,

by fits and starts, during the past five or six years, and may

possibly finish in the course of five or six more. The book is a

story which details some passages in the life of an ignorant

village boy, Huck Finn, son of the town drunkard of my time out

west, there. He has run away from his persecuting father, and

from a persecuting good widow who wishes to make a nice,

truth-telling, respectable boy of him; and with him a slave of

the widow’s has also escaped. They have found a fragment of a

lumber raft (it is high water and dead summer time), and are

floating down the river by night, and hiding in the willows by

day,—bound for Cairo,—whence the negro will seek freedom in the

heart of the free States. But in a fog, they pass Cairo without

knowing it. By and by they begin to suspect the truth, and Huck

Finn is persuaded to end the dismal suspense by swimming down to

a huge raft which they have seen in the distance ahead of them,

creeping aboard under cover of the darkness, and gathering the

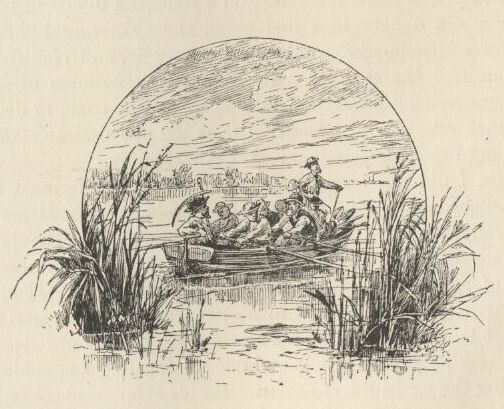

needed information by eavesdropping:—

But you know a young person can’t wait very well when he is

impatient to find a thing out. We talked it over, and by and by

Jim said it was such a black night, now, that it wouldn’t be no

risk to swim down to the big raft and crawl aboard and

listen—they would talk about Cairo, because they would be

calculating to go ashore there for a spree, maybe, or anyway they

would send boats ashore to buy whiskey or fresh meat or

something. Jim had a wonderful level head, for a nigger: he could

most always start a good plan when you wanted one.

I stood up and shook my rags off and jumped into the river,

and struck out for the raft’s light. By and by, when I got down

nearly to her, I eased up and went slow and cautious. But

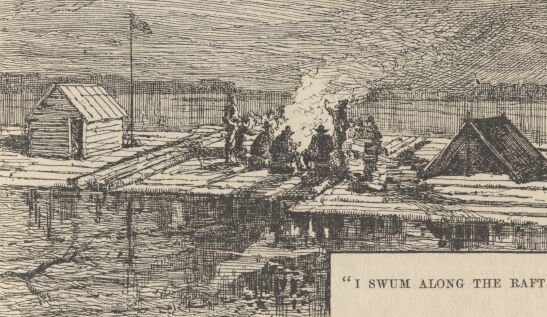

everything was all right—nobody at the sweeps. So I swum down

along the raft till I was most abreast the camp fire in the

middle, then I crawled aboard and inched along and got in amongst

some bundles of shingles on the weather side of the fire. There

was thirteen men there—they was the watch on deck of course. And

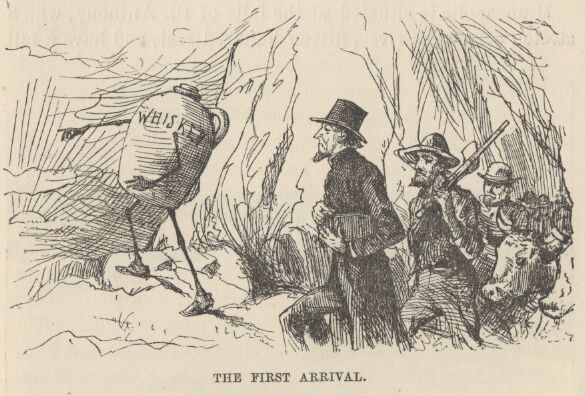

a mighty rough-looking lot, too. They had a jug, and tin cups,

and they kept the jug moving. One man was singing—roaring, you

may say; and it wasn’t a nice song—for a parlor anyway. He

roared through his nose, and strung out the last word of every

line very long. When he was done they all fetched a kind of Injun

war-whoop, and then another was sung. It begun:—

“There was a woman in our towdn,

In our towdn did dwed’l (dwell,)

She loved her husband dear-i-lee,

But another man twyste as wed’l.

Singing too, riloo, riloo, riloo,

Ri-too, riloo, rilay—

She loved her husband dear-i-lee,

But another man twyste as wed’l.”

And so on—fourteen verses. It was kind of poor, and when he

was going to start on the next verse one of them said it was the

tune the old cow died on; and another one said, “Oh, give us a

rest.” And another one told him to take a walk. They made fun of

him till he got mad and jumped up and begun to cuss the crowd,

and said he could lame any thief in the lot.

They was all about to make a break for him, but the biggest

man there jumped up and says—

“Set whar you are, gentlemen. Leave him to me; he’s my

meat.”

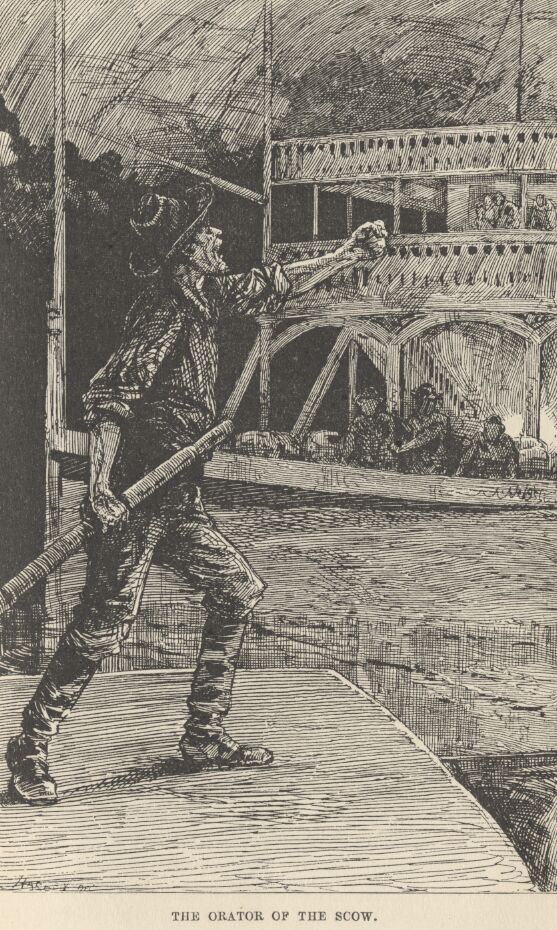

Then he jumped up in the air three times and cracked his heels

together every time. He flung off a buckskin coat that was all

hung with fringes, and says, “You lay thar tell the chawin-up’s

done;” and flung his hat down, which was all over ribbons, and

says, “You lay thar tell his sufferin’s is over.”

Then he jumped up in the air and cracked his heels together

again and shouted out—

“Whoo-oop! I’m the old original iron-jawed, brass-mounted,

copper-bellied corpse-maker from the wilds of Arkansaw!—Look at

me! I’m the man they call Sudden Death and General Desolation!

Sired by a hurricane, dam’d by an earthquake, half-brother to the

cholera, nearly related to the small-pox on the mother’s side!

Look at me! I take nineteen alligators and a bar’l of whiskey for

breakfast when I’m in robust health, and a bushel of rattlesnakes

and a dead body when I’m ailing! I split the everlasting rocks

with my glance, and I squench the thunder when I speak! Whoo-oop!

Stand back and give me room according to my strength! Blood’s my

natural drink, and the wails of the dying is music to my ear!

Cast your eye on me, gentlemen!—and lay low and hold your

breath, for I’m bout to turn myself loose!”

All the time he was getting this off, he was shaking his head

and looking fierce, and kind of swelling around in a little

circle, tucking up his wrist-bands, and now and then

straightening up and beating his breast with his fist, saying,

“Look at me, gentlemen!” When he got through, he jumped up and

cracked his heels together three times, and let off a roaring

“Whoo-oop! I’m the bloodiest son of a wildcat that lives!”

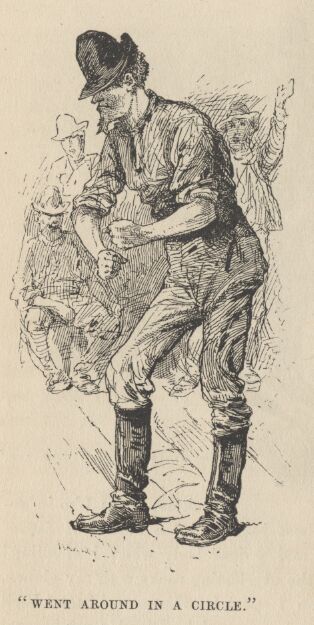

Then the man that had started the row tilted his old slouch

hat down over his right eye; then he bent stooping forward, with

his back sagged and his south end sticking out far, and his fists

a-shoving out and drawing in in front of him, and so went around

in a little circle about three times, swelling himself up and

breathing hard. Then he straightened, and jumped up and cracked

his heels together three times, before he lit again (that made

them cheer), and he begun to shout like this—

“Whoo-oop! bow your neck and spread, for the kingdom of

sorrow’s a-coming! Hold me down to the earth, for I feel my

powers a-working! whoo-oop! I’m a child of sin, don’t let me get

a start! Smoked glass, here, for all! Don’t attempt to look at me

with the naked eye, gentlemen! When I’m playful I use the

meridians of longitude and parallels of latitude for a seine, and

drag the Atlantic Ocean for whales! I scratch my head with the

lightning, and purr myself to sleep with the thunder! When I’m

cold, I bile the Gulf of Mexico and bathe in it; when I’m hot I

fan myself with an equinoctial storm; when I’m thirsty I reach up

and suck a cloud dry like a sponge; when I range the earth

hungry, famine follows in my tracks! Whoo-oop! Bow your neck and

spread! I put my hand on the sun’s face and make it night in the

earth; I bite a piece out of the moon and hurry the seasons; I

shake myself and crumble the mountains! Contemplate me through

leather—don’t use the naked eye! I’m the man with a petrified

heart and biler-iron bowels! The massacre of isolated communities

is the pastime of my idle moments, the destruction of

nationalities the serious business of my life! The boundless

vastness of the great American desert is my enclosed property,

and I bury my dead on my own premises!” He jumped up and cracked

his heels together three times before he lit (they cheered him

again), and as he come down he shouted out: “Whoo-oop! bow your

neck and spread, for the pet child of calamity’s a-coming!”

Then the other one went to swelling around and blowing

again—the first one—the one they called Bob; next, the Child of

Calamity chipped in again, bigger than ever; then they both got

at it at the same time, swelling round and round each other and

punching their fists most into each other’s faces, and whooping

and jawing like Injuns; then Bob called the Child names, and the

Child called him names back again: next, Bob called him a heap

rougher names and the Child come back at him with the very worst

kind of language; next, Bob knocked the Child’s hat off, and the

Child picked it up and kicked Bob’s ribbony hat about six foot;

Bob went and got it and said never mind, this warn’t going to be

the last of this thing, because he was a man that never forgot

and never forgive, and so the Child better look out, for there

was a time a-coming, just as sure as he was a living man, that he

would have to answer to him with the best blood in his body. The

Child said no man was willinger than he was for that time to

come, and he would give Bob fair warning, now, never to cross his

path again, for he could never rest till he had waded in his

blood, for such was his nature, though he was sparing him now on

account of his family, if he had one.

Both of them was edging away in different directions, growling

and shaking their heads and going on about what they was going to

do; but a little black-whiskered chap skipped up and says—

“Come back here, you couple of chicken-livered cowards, and

I’ll thrash the two of ye!”

And he done it, too. He snatched them, he jerked them this way

and that, he booted them around, he knocked them sprawling faster

than they could get up. Why, it warn’t two minutes till they

begged like dogs—and how the other lot did yell and laugh and

clap their hands all the way through, and shout “Sail in,

Corpse-Maker!” “Hi! at him again, Child of Calamity!” “Bully for

you, little Davy!” Well, it was a perfect pow-wow for a while.

Bob and the Child had red noses and black eyes when they got

through. Little Davy made them own up that they were sneaks and

cowards and not fit to eat with a dog or drink with a nigger;

then Bob and the Child shook hands with each other, very solemn,

and said they had always respected each other and was willing to

let bygones be bygones. So then they washed their faces in the

river; and just then there was a loud order to stand by for a

crossing, and some of them went forward to man the sweeps there,

and the rest went aft to handle the after-sweeps.

I laid still and waited for fifteen minutes, and had a smoke

out of a pipe that one of them left in reach; then the crossing

was finished, and they stumped back and had a drink around and

went to talking and singing again. Next they got out an old

fiddle, and one played and another patted juba, and the rest

turned themselves loose on a regular old-fashioned keel-boat

break-down. They couldn’t keep that up very long without getting

winded, so by and by they settled around the jug again.

They sung “jolly, jolly raftman’s the life for me,” with a

musing chorus, and then they got to talking about differences

betwixt hogs, and their different kind of habits; and next about

women and their different ways: and next about the best ways to

put out houses that was afire; and next about what ought to be

done with the Injuns; and next about what a king had to do, and

how much he got; and next about how to make cats fight; and next

about what to do when a man has fits; and next about differences

betwixt clear-water rivers and muddy-water ones. The man they

called Ed said the muddy Mississippi water was wholesomer to

drink than the clear water of the Ohio; he said if you let a pint

of this yaller Mississippi water settle, you would have about a

half to three-quarters of an inch of mud in the bottom, according

to the stage of the river, and then it warn’t no better than Ohio

water—what you wanted to do was to keep it stirred up—and when

the river was low, keep mud on hand to put in and thicken the

water up the way it ought to be.

The Child of Calamity said that was so; he said there was

nutritiousness in the mud, and a man that drunk Mississippi water

could grow corn in his stomach if he wanted to. He says—

“You look at the graveyards; that tells the tale. Trees won’t

grow worth chucks in a Cincinnati graveyard, but in a Sent Louis

graveyard they grow upwards of eight hundred foot high. It’s all

on account of the water the people drunk before they laid up. A

Cincinnati corpse don’t richen a soil any.”

And they talked about how Ohio water didn’t like to mix with

Mississippi water. Ed said if you take the Mississippi on a rise

when the Ohio is low, you’ll find a wide band of clear water all

the way down the east side of the Mississippi for a hundred mile

or more, and the minute you get out a quarter of a mile from

shore and pass the line, it is all thick and yaller the rest of

the way across. Then they talked about how to keep tobacco from

getting moldy, and from that they went into ghosts and told about

a lot that other folks had seen; but Ed says—

“Why don’t you tell something that you’ve seen yourselves? Now

let me have a say. Five years ago I was on a raft as big as this,

and right along here it was a bright moonshiny night, and I was

on watch and boss of the stabboard oar forrard, and one of my

pards was a man named Dick Allbright, and he come along to where

I was sitting, forrard—gaping and stretching, he was—and

stooped down on the edge of the raft and washed his face in the

river, and come and set down by me and got out his pipe, and had

just got it filled, when he looks up and says—

“Why looky-here," he says, "ain’t that Buck Miller’s place,

over yander in the bend."

“Yes," says I, "it is—why." He laid his pipe down and leant

his head on his hand, and says—

“I thought we’d be furder down." I says—

“I thought it too, when I went off watch”—we was standing

six hours on and six off—“but the boys told me," I says, "that

the raft didn’t seem to hardly move, for the last hour," says I,

"though she’s a slipping along all right, now," says I. He give a

kind of a groan, and says—

“I’ve seed a raft act so before, along here," he says,

"’pears to me the current has most quit above the head of this

bend durin” the last two years," he says.

“Well, he raised up two or three times, and looked away off

and around on the water. That started me at it, too. A body is

always doing what he sees somebody else doing, though there

mayn’t be no sense in it. Pretty soon I see a black something

floating on the water away off to stabboard and quartering behind

us. I see he was looking at it, too. I says—

“What’s that?" He says, sort of pettish,—

“Tain’t nothing but an old empty bar’l."

“An empty bar’l!" says I, "why," says I, "a spy-glass is a

fool to your eyes. How can you tell it’s an empty bar’l?" He

says—

“I don’t know; I reckon it ain’t a bar’l, but I thought it

might be," says he.

“Yes," I says, "so it might be, and it might be anything

else, too; a body can’t tell nothing about it, such a distance as

that," I says.

“We hadn’t nothing else to do, so we kept on watching it. By

and by I says—

“Why looky-here, Dick Allbright, that thing’s a-gaining on

us, I believe."

“He never said nothing. The thing gained and gained, and I

judged it must be a dog that was about tired out. Well, we swung

down into the crossing, and the thing floated across the bright

streak of the moonshine, and, by George, it was bar’l. Says

I—

“Dick Allbright, what made you think that thing was a bar’l,

when it was a half a mile off," says I. Says he—

“I don’t know." Says I—

“You tell me, Dick Allbright." He says—

“Well, I knowed it was a bar’l; I’ve seen it before; lots has

seen it; they says it’s a haunted bar’l."

“I called the rest of the watch, and they come and stood

there, and I told them what Dick said. It floated right along

abreast, now, and didn’t gain any more. It was about twenty foot

off. Some was for having it aboard, but the rest didn’t want to.

Dick Allbright said rafts that had fooled with it had got bad

luck by it. The captain of the watch said he didn’t believe in

it. He said he reckoned the bar’l gained on us because it was in

a little better current than what we was. He said it would leave

by and by.

“So then we went to talking about other things, and we had a

song, and then a breakdown; and after that the captain of the

watch called for another song; but it was clouding up, now, and

the bar’l stuck right thar in the same place, and the song didn’t

seem to have much warm-up to it, somehow, and so they didn’t

finish it, and there warn’t any cheers, but it sort of dropped

flat, and nobody said anything for a minute. Then everybody tried

to talk at once, and one chap got off a joke, but it warn’t no

use, they didn’t laugh, and even the chap that made the joke

didn’t laugh at it, which ain’t usual. We all just settled down

glum, and watched the bar’l, and was oneasy and oncomfortable.

Well, sir, it shut down black and still, and then the wind begin

to moan around, and next the lightning begin to play and the

thunder to grumble. And pretty soon there was a regular storm,

and in the middle of it a man that was running aft stumbled and

fell and sprained his ankle so that he had to lay up. This made

the boys shake their heads. And every time the lightning come,

there was that bar’l with the blue lights winking around it. We

was always on the look-out for it. But by and by, towards dawn,

she was gone. When the day come we couldn’t see her anywhere, and

we warn’t sorry, neither.

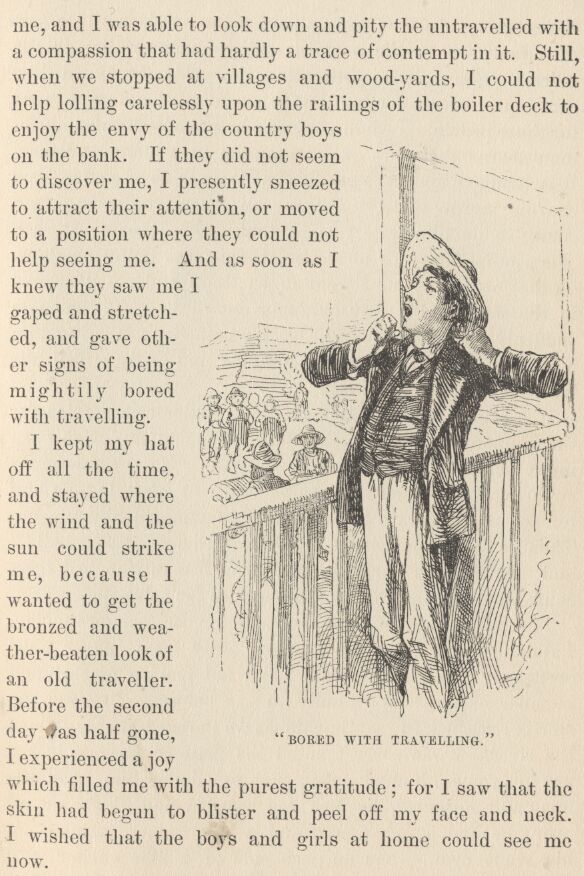

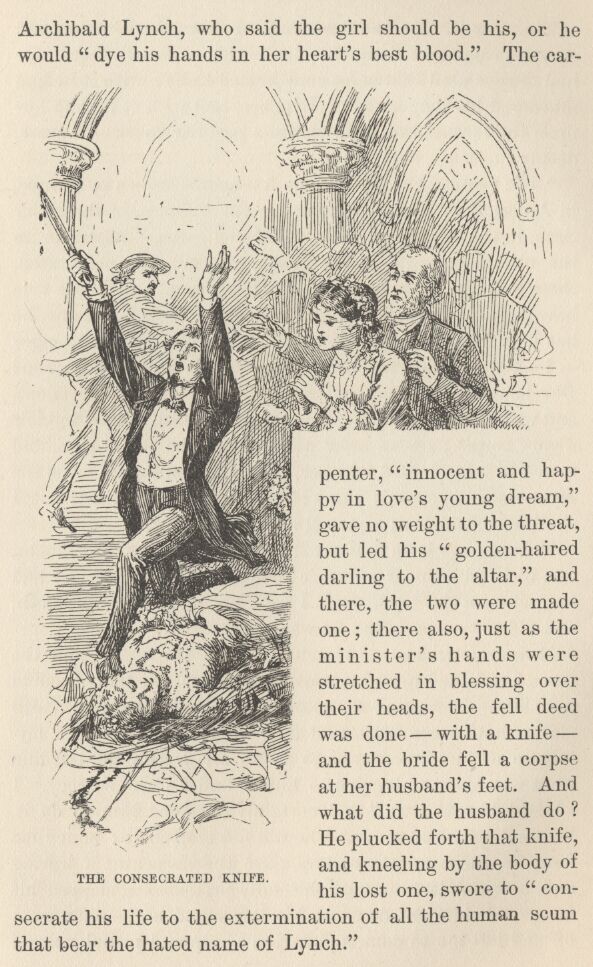

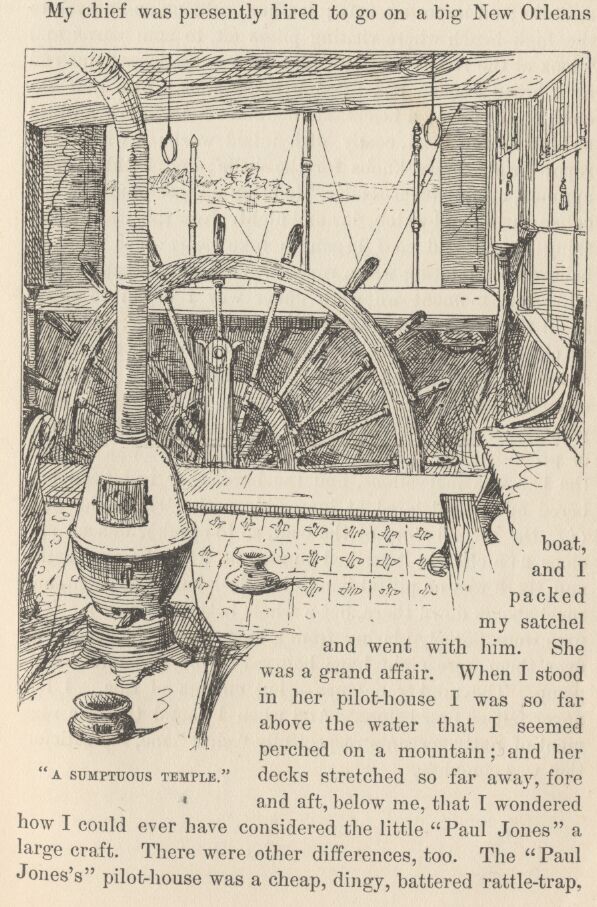

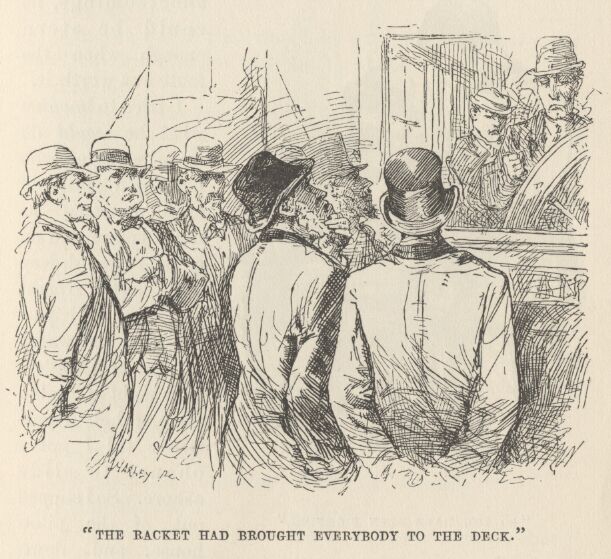

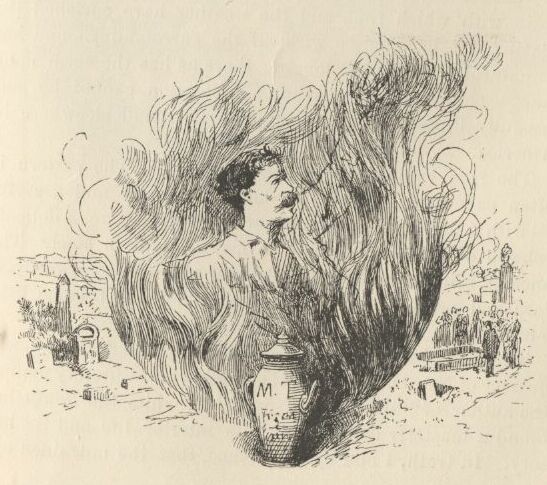

![]()

“But next night about half-past nine, when there was songs and

high jinks going on, here she comes again, and took her old roost

on the stabboard side. There warn’t no more high jinks. Everybody

got solemn; nobody talked; you couldn’t get anybody to do

anything but set around moody and look at the bar’l. It begun to

cloud up again. When the watch changed, the off watch stayed up,

“stead of turning in. The storm ripped and roared around all

night, and in the middle of it another man tripped and sprained

his ankle, and had to knock off. The bar’l left towards day, and

nobody see it go.

“Everybody was sober and down in the mouth all day. I don’t

mean the kind of sober that comes of leaving liquor alone—not

that. They was quiet, but they all drunk more than usual—not

together—but each man sidled off and took it private, by

himself.

“After dark the off watch didn’t turn in; nobody sung, nobody

talked; the boys didn’t scatter around, neither; they sort of

huddled together, forrard; and for two hours they set there,

perfectly still, looking steady in the one direction, and heaving

a sigh once in a while. And then, here comes the bar’l again. She

took up her old place. She staid there all night; nobody turned

in. The storm come on again, after midnight. It got awful dark;

the rain poured down; hail, too; the thunder boomed and roared

and bellowed; the wind blowed a hurricane; and the lightning

spread over everything in big sheets of glare, and showed the

whole raft as plain as day; and the river lashed up white as milk

as far as you could see for miles, and there was that bar’l

jiggering along, same as ever. The captain ordered the watch to

man the after sweeps for a crossing, and nobody would go—no more

sprained ankles for them, they said. They wouldn’t even walk aft.

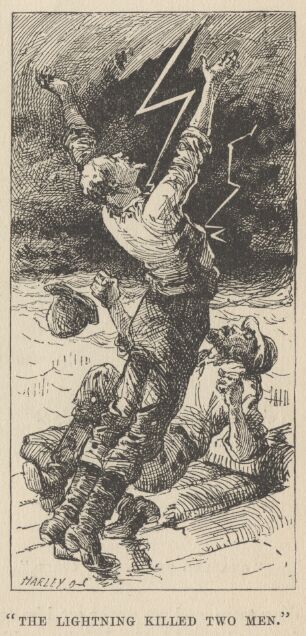

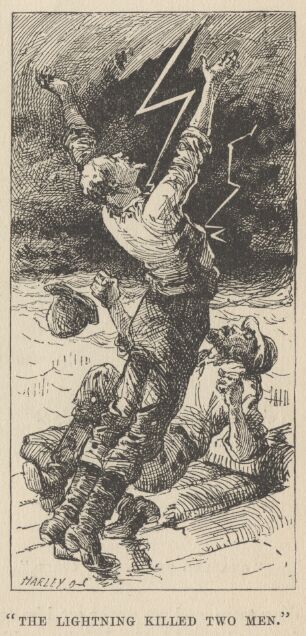

Well then, just then the sky split wide open, with a crash, and

the lightning killed two men of the after watch, and crippled two

more. Crippled them how, says you? Why, sprained their

ankles!

“The bar’l left in the dark betwixt lightnings, towards dawn.

Well, not a body eat a bite at breakfast that morning. After that

the men loafed around, in twos and threes, and talked low

together. But none of them herded with Dick Allbright. They all

give him the cold shake. If he come around where any of the men

was, they split up and sidled away. They wouldn’t man the sweeps

with him. The captain had all the skiffs hauled up on the raft,

alongside of his wigwam, and wouldn’t let the dead men be took

ashore to be planted; he didn’t believe a man that got ashore

would come back; and he was right.

“After night come, you could see pretty plain that there was

going to be trouble if that bar’l come again; there was such a

muttering going on. A good many wanted to kill Dick Allbright,

because he’d seen the bar’l on other trips, and that had an ugly

look. Some wanted to put him ashore. Some said, let’s all go

ashore in a pile, if the bar’l comes again.

“This kind of whispers was still going on, the men being

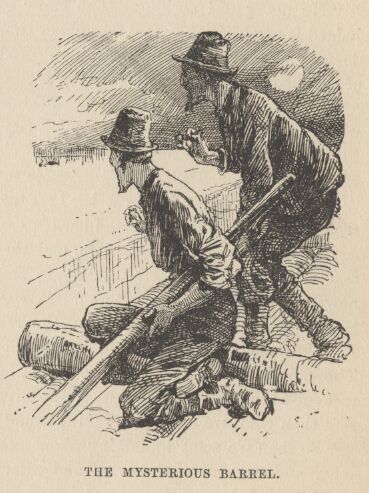

bunched together forrard watching for the bar’l, when, lo and

behold you, here she comes again. Down she comes, slow and

steady, and settles into her old tracks. You could a heard a pin

drop. Then up comes the captain, and says:—

“Boys, don’t be a pack of children and fools; I don’t want

this bar’l to be dogging us all the way to Orleans, and you

don’t; well, then, how’s the best way to stop it? Burn it

up,—that’s the way. I’m going to fetch it aboard," he says. And

before anybody could say a word, in he went.

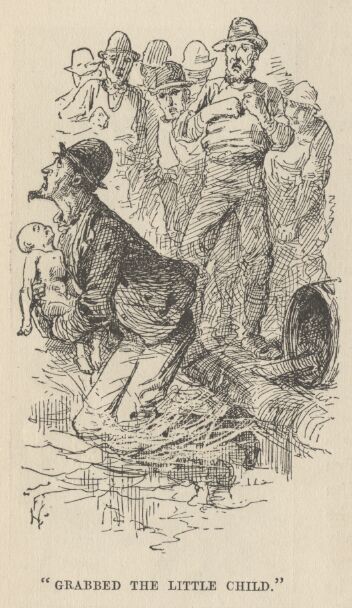

“He swum to it, and as he come pushing it to the raft, the men

spread to one side. But the old man got it aboard and busted in

the head, and there was a baby in it! Yes, sir, a stark naked

baby. It was Dick Allbright’s baby; he owned up and said so.

“Yes," he says, a-leaning over it, "yes, it is my own

lamented darling, my poor lost Charles William Allbright

deceased," says he,—for he could curl his tongue around the

bulliest words in the language when he was a mind to, and lay

them before you without a jint started, anywheres. Yes, he said

he used to live up at the head of this bend, and one night he

choked his child, which was crying, not intending to kill

it,—which was prob’ly a lie,—and then he was scared, and buried

it in a bar’l, before his wife got home, and off he went, and

struck the northern trail and went to rafting; and this was the

third year that the bar’l had chased him. He said the bad luck

always begun light, and lasted till four men was killed, and then

the bar’l didn’t come any more after that. He said if the men

would stand it one more night,—and was a-going on like

that,—but the men had got enough. They started to get out a boat

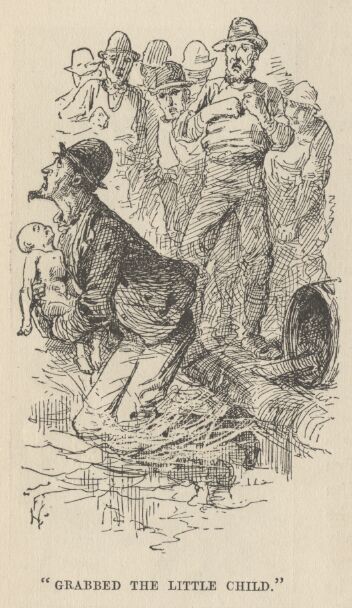

to take him ashore and lynch him, but he grabbed the little child

all of a sudden and jumped overboard with it hugged up to his

breast and shedding tears, and we never see him again in this

life, poor old suffering soul, nor Charles William neither.”

“Who was shedding tears?” says Bob; “was it Allbright or the

baby?”

“Why, Allbright, of course; didn’t I tell you the baby was

dead. Been dead three years—how could it cry?”

“Well, never mind how it could cry—how could it keep all that

time?” says Davy. “You answer me that.”

“I don’t know how it done it,” says Ed. “It done it

though—that’s all I know about it.”

“Say—what did they do with the bar’l?” says the Child of

Calamity.

“Why, they hove it overboard, and it sunk like a chunk of

lead.”

“Edward, did the child look like it was choked?” says one.

“Did it have its hair parted?” says another.

“What was the brand on that bar’l, Eddy?” says a fellow they

called Bill.

“Have you got the papers for them statistics, Edmund?” says

Jimmy.

“Say, Edwin, was you one of the men that was killed by the

lightning.” says Davy.

“Him? O, no, he was both of “em,” says Bob. Then they all

haw-hawed.

“Say, Edward, don’t you reckon you’d better take a pill? You

look bad—don’t you feel pale?” says the Child of Calamity.

“O, come, now, Eddy,” says Jimmy, “show up; you must a kept

part of that bar’l to prove the thing by. Show us the

bunghole—do—and we’ll all believe you.”

“Say, boys,” says Bill, “less divide it up. Thar’s thirteen of

us. I can swaller a thirteenth of the yarn, if you can worry down

the rest.”

Ed got up mad and said they could all go to some place which

he ripped out pretty savage, and then walked off aft cussing to

himself, and they yelling and jeering at him, and roaring and

laughing so you could hear them a mile.

“Boys, we’ll split a watermelon on that,” says the Child of

Calamity; and he come rummaging around in the dark amongst the

shingle bundles where I was, and put his hand on me. I was warm

and soft and naked; so he says “Ouch!” and jumped back.

“Fetch a lantern or a chunk of fire here, boys—there’s a

snake here as big as a cow!”

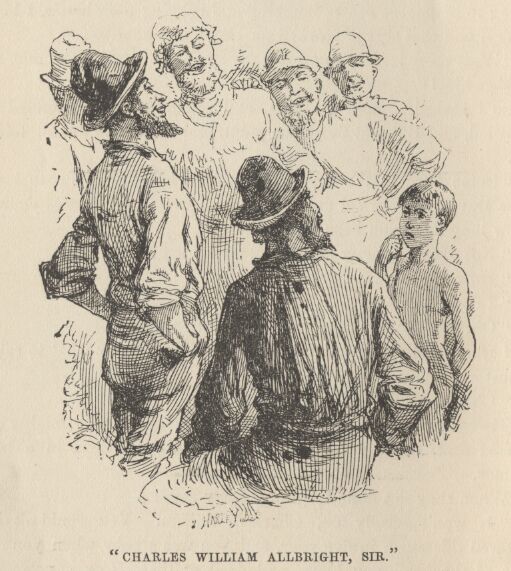

So they run there with a lantern and crowded up and looked in

on me.

“Come out of that, you beggar!” says one.

“Who are you?” says another.

“What are you after here? Speak up prompt, or overboard you

go.”

“Snake him out, boys. Snatch him out by the heels.”

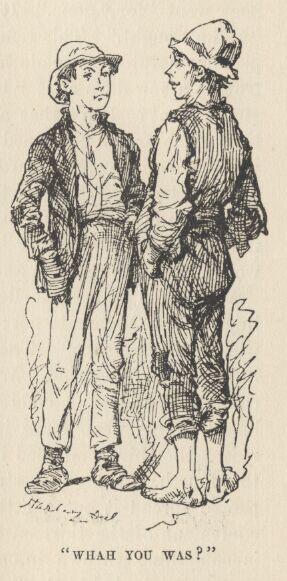

I began to beg, and crept out amongst them trembling. They

looked me over, wondering, and the Child of Calamity says:—

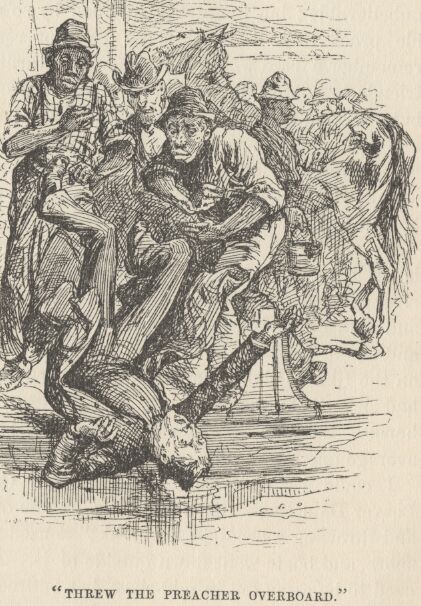

“A cussed thief! Lend a hand and less heave him

overboard!”

“No,” says Big Bob, “less get out the paint-pot and paint him

a sky blue all over from head to heel, and then heave him over!”

“Good, that’s it. Go for the paint, Jimmy.”

When the paint come, and Bob took the brush and was just going

to begin, the others laughing and rubbing their hands, I begun to

cry, and that sort of worked on Davy, and he says—

“’Vast there! He’s nothing but a cub. I’ll paint the man

that tetches him!”

So I looked around on them, and some of them grumbled and

growled, and Bob put down the paint, and the others didn’t take

it up.

“Come here to the fire, and less see what you’re up to here,”

says Davy. “Now set down there and give an account of yourself.

How long have you been aboard here?”

“Not over a quarter of a minute, sir,” says I.

“How did you get dry so quick?”

“I don’t know, sir. I’m always that way, mostly.”

“Oh, you are, are you. What’s your name?”

I warn’t going to tell my name. I didn’t know what to say, so

I just says—

“Charles William Allbright, sir.”

Then they roared—the whole crowd; and I was mighty glad I

said that, because maybe laughing would get them in a better

humor.

When they got done laughing, Davy says—

“It won’t hardly do, Charles William. You couldn’t have growed

this much in five year, and you was a baby when you come out of

the bar’l, you know, and dead at that. Come, now, tell a straight

story, and nobody’ll hurt you, if you ain’t up to anything wrong.

What is your name?”

“Aleck Hopkins, sir. Aleck James Hopkins.”

“Well, Aleck, where did you come from, here?”

“From a trading scow. She lays up the bend yonder. I was born

on her. Pap has traded up and down here all his life; and he told

me to swim off here, because when you went by he said he would

like to get some of you to speak to a Mr. Jonas Turner, in Cairo,

and tell him—”

“Oh, come!”

“Yes, sir; it’s as true as the world; Pap he says—”

“Oh, your grandmother!”

They all laughed, and I tried again to talk, but they broke in

on me and stopped me.

“Now, looky-here,” says Davy; “you’re scared, and so you talk

wild. Honest, now, do you live in a scow, or is it a lie?”

“Yes, sir, in a trading scow. She lays up at the head of the

bend. But I warn’t born in her. It’s our first trip.”

“Now you’re talking! What did you come aboard here, for? To

steal?”

“No, sir, I didn’t.—It was only to get a ride on the raft.

All boys does that.”

“Well, I know that. But what did you hide for?”

“Sometimes they drive the boys off.”

“So they do. They might steal. Looky-here; if we let you off

this time, will you keep out of these kind of scrapes

hereafter?”

“’Deed I will, boss. You try me.”

“All right, then. You ain’t but little ways from shore.

Overboard with you, and don’t you make a fool of yourself another

time this way.—Blast it, boy, some raftsmen would rawhide you

till you were black and blue!”

I didn’t wait to kiss good-bye, but went overboard and broke

for shore. When Jim come along by and by, the big raft was away

out of sight around the point. I swum out and got aboard, and was

mighty glad to see home again.

The boy did not get the information he was after, but his

adventure has furnished the glimpse of the departed raftsman and

keelboatman which I desire to offer in this place.

I now come to a phase of the Mississippi River life of the

flush times of steamboating, which seems to me to warrant full

examination—the marvelous science of piloting, as displayed

there. I believe there has been nothing like it elsewhere in the

world.

Chapter 4

The Boys” Ambition

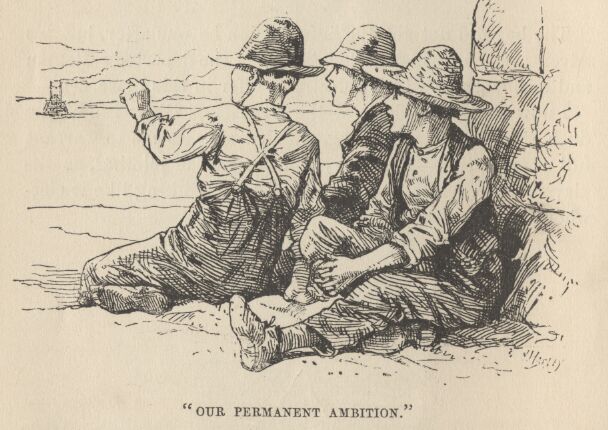

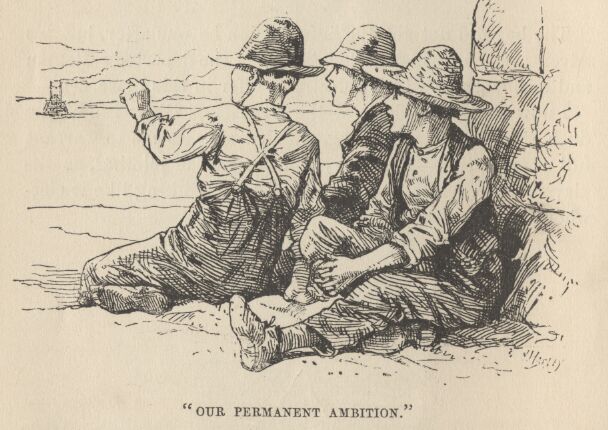

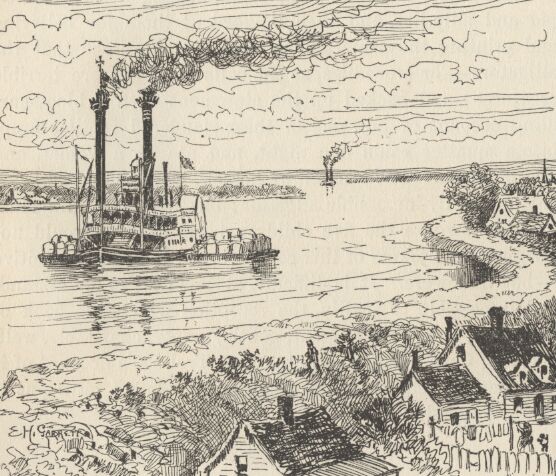

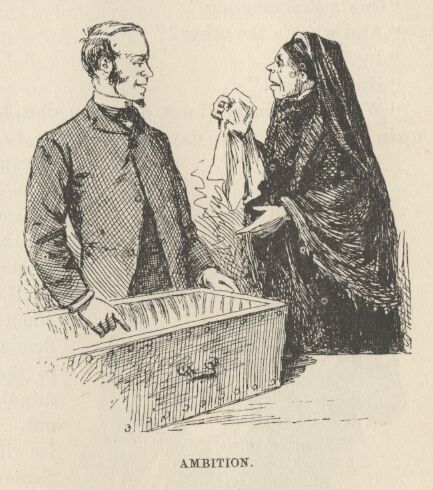

WHEN

I was a boy, there was but one permanent ambition among

my comrades in our

village

on

the west bank of the Mississippi River. That was, to be a

steamboatman. We had transient ambitions of other sorts, but they

were only transient. When a circus came and went, it left us all

burning to become clowns; the first negro minstrel show that came

to our section left us all suffering to try that kind of life;

now and then we had a hope that if we lived and were good, God

would permit us to be pirates. These ambitions faded out, each in

its turn; but the ambition to be a steamboatman always

remained.

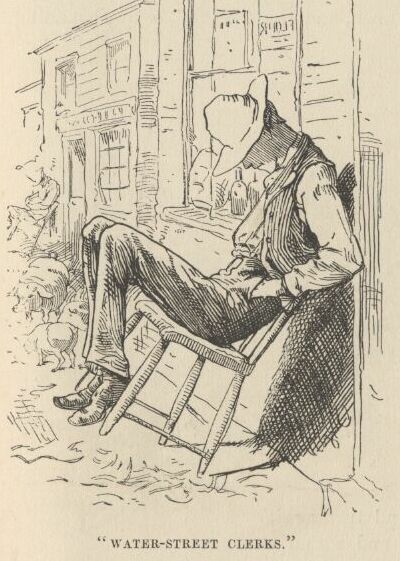

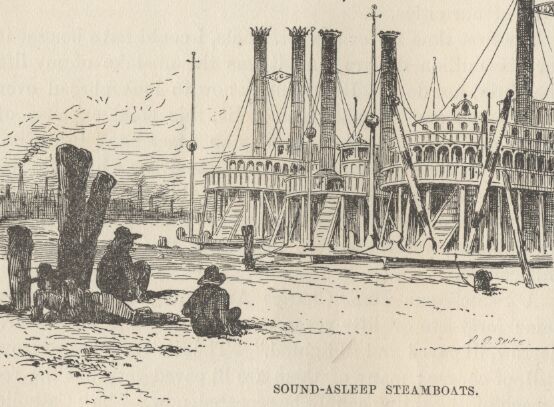

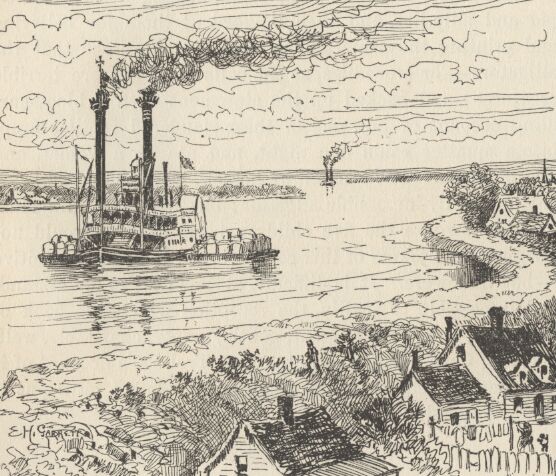

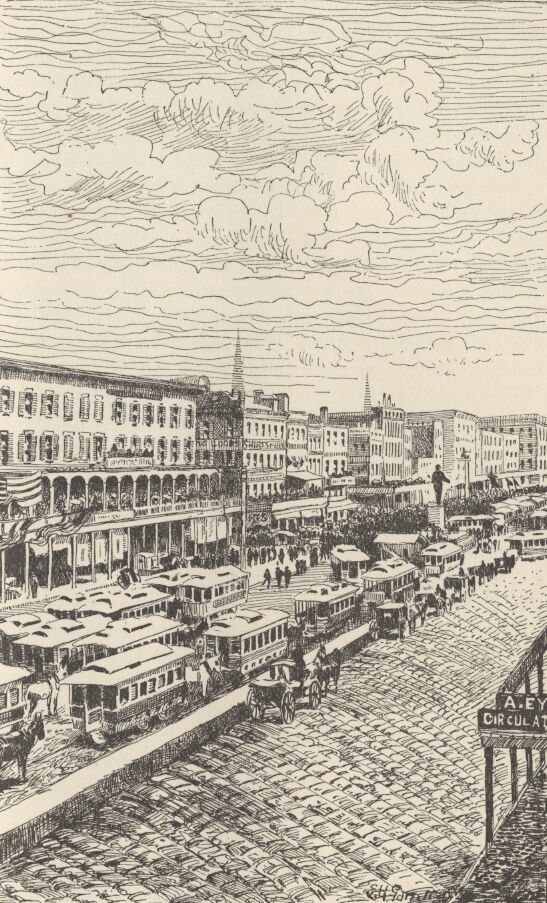

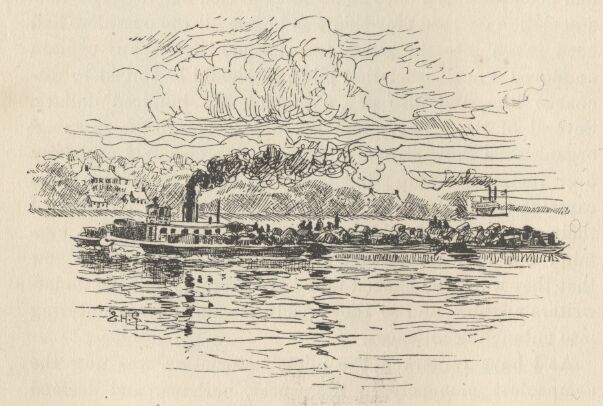

Once a day a cheap, gaudy packet arrived upward from St.

Louis, and another downward from Keokuk. Before these events, the

day was glorious with expectancy; after them, the day was a dead

and empty thing. Not only the boys, but the whole village, felt

this. After all these years I can picture that old time to myself

now, just as it was then: the white town drowsing in the sunshine

of a summer’s morning; the streets empty, or pretty nearly so;

one or two clerks sitting in front of the Water Street stores,

with their splint-bottomed chairs tilted back against the wall,

chins on breasts, hats slouched over their faces, asleep—with

shingle-shavings enough around to show what broke them down; a

sow and a litter of pigs loafing along the sidewalk, doing a good

business in watermelon rinds and seeds; two or three lonely

little freight piles scattered about the “levee;” a pile of

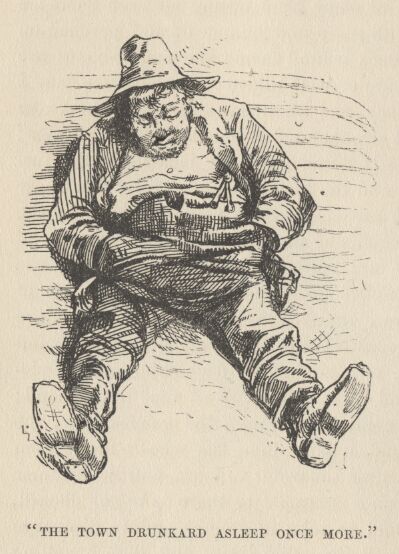

“skids” on the slope of the stone-paved wharf, and the fragrant

town drunkard asleep in the shadow of them; two or three wood

flats at the head of the wharf, but nobody to listen to the

peaceful lapping of the wavelets against them; the great

Mississippi, the majestic, the magnificent Mississippi, rolling

its mile-wide tide along, shining in the sun; the dense forest

away on the other side; the “point” above the town, and the

“point” below, bounding the river-glimpse and turning it into a

sort of sea, and withal a very still and brilliant and lonely

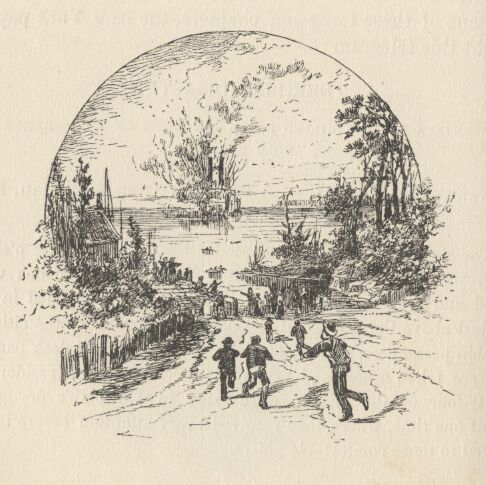

one. Presently a film of dark smoke appears above one of those

remote “points;” instantly a negro drayman, famous for his quick

eye and prodigious voice, lifts up the cry, “S-t-e-a-m-boat

a-comin’!” and the scene changes! The town drunkard stirs, the

clerks wake up, a furious clatter of drays follows, every house

and store pours out a human contribution, and all in a twinkling

the dead town is alive and moving.

Drays, carts, men, boys, all

go hurrying from many quarters to a common center, the wharf.

Assembled there, the people fasten their eyes upon the coming

boat as upon a wonder they are seeing for the first time. And the

boat is rather a handsome sight, too. She is long and sharp and

trim and pretty; she has two tall, fancy-topped chimneys, with a

gilded device of some kind swung between them; a fanciful

pilot-house, a glass and “gingerbread’, perched on top of the

“texas” deck behind them; the paddle-boxes are gorgeous with a

picture or with gilded rays above the boat’s name; the boiler

deck, the hurricane deck, and the texas deck are fenced and

ornamented with clean white railings; there is a flag gallantly

flying from the jack-staff; the furnace doors are open and the

fires glaring bravely; the upper decks are black with passengers;

the captain stands by the big bell, calm, imposing, the envy of

all; great volumes of the blackest smoke are rolling and tumbling

out of the chimneys—a husbanded grandeur created with a bit of

pitch pine just before arriving at a town; the crew are grouped

on the forecastle; the broad stage is run far out over the port

bow, and an envied deckhand stands picturesquely on the end of it

with a coil of rope in his hand; the pent steam is screaming

through the gauge-cocks, the captain lifts his hand, a bell

rings, the wheels stop; then they turn back, churning the water

to foam, and the steamer is at rest. Then such a scramble as

there is to get aboard, and to get ashore, and to take in freight

and to discharge freight, all at one and the same time; and such

a yelling and cursing as the mates facilitate it all with! Ten

minutes later the steamer is under way again, with no flag on the

jack-staff and no black smoke issuing from the chimneys. After

ten more minutes the town is dead again, and the town drunkard

asleep by the skids once more.

My father was a justice of the peace, and I supposed he

possessed the power of life and death over all men and could hang

anybody that offended him. This was distinction enough for me as

a general thing; but the desire to be a steamboatman kept

intruding, nevertheless. I first wanted to be a cabin-boy, so

that I could come out with a white apron on and shake a

tablecloth over the side, where all my old comrades could see me;

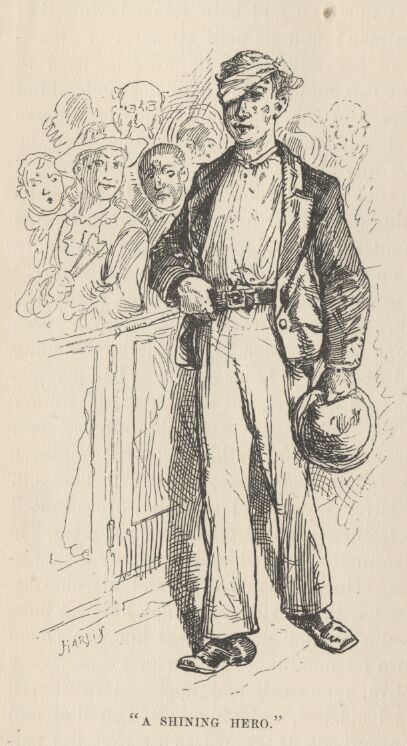

later I thought I would rather be the deckhand who stood on the

end of the stage-plank with the coil of rope in his hand, because

he was particularly conspicuous. But these were only

day-dreams,—they were too heavenly to be contemplated as real

possibilities. By and by one of our boys went away. He was not

heard of for a long time. At last he turned up as apprentice

engineer or “striker” on a steamboat. This thing shook the bottom

out of all my Sunday-school teachings. That boy had been