Louisiana Anthology

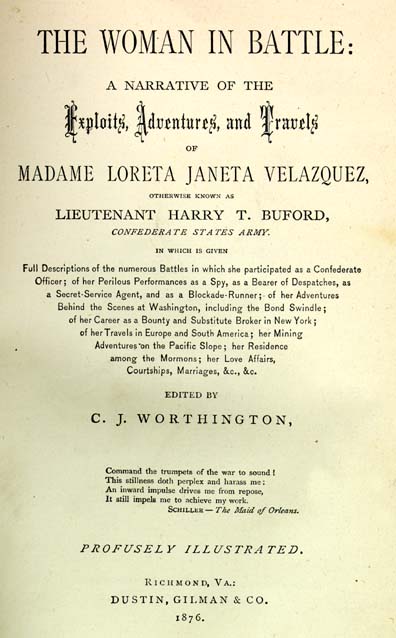

Velazquez, Loreta Janeta.

Ed. by C. J. Worthington.

The Woman in Battle.

AUTHOR'S PREFATORY NOTICE.

If I expected by this story of my adventures to achieve

any literary reputation, I might be disposed, on account of its

many faults of style, to ask the indulgence of those who will

do me the honor to undertake its perusal. As, however,

I only attempted authorship because I had, as others assured

me, and as I myself believed, something to tell that was worth

telling, I have been more concerned about the matter than

the manner of my book, and I hope that the narrative will prove

of sufficient interest to compensate for a lack of literary elegance

in setting forth. Mine has been a life too busily

occupied in other matters for me to cultivate the graces

of authorship; and the best I can hope to do is to relate my

story with simplicity and truth, and then let it find its fate,

whether it be praise or condemnation.

The composition of this book has been a labor of love, and

yet one of no ordinary difficulties. The loss of my notes has

compelled me to rely entirely upon my memory; and memory

is apt to be very treacherous, especially when, after a number

of years, one endeavors to relate in their proper sequence a

long series of complicated transactions. Besides, I have been

compelled to write hurriedly, and in the intervals of pressing

business, the necessities I have been under of earning my daily

bread being such as could not be disregarded, even for the

purpose of winning the laurels of authorship. To speak

plainly, however, I care little for laurels of any kind just now,

and am much more anxious for the money that I hope this

book will bring in to me than I am for the praises of either

critics or public. The money I want badly, while praise, although it will

not be ungratifying, I am sufficiently philosophical to get along very

comfortably without.

I do not know what the good people who will read this

book will think of me. My career has differed materially

from that of most women; and some things that I have done

have shocked persons for whom I have every respect, however

much my ideas of propriety may differ from theirs. I can only

say, however, that in my opinion there was nothing essentially

improper in my putting on the uniform of a Confederate officer

for the purpose of taking an active part in the war; and, as

when on the field of battle, in camp, and during long and

toilsome marches, I endeavored, not without success, to display

a courage and fortitude not inferior to the most courageous of

the men around me, and as I never did aught to disgrace the

uniform I wore, but, on the contrary, won the hearty

commendation of my comrades, I feel that I have nothing to be

ashamed of. Had I believed that my book needed any apologies

on this score, it would never have been written; and,

having written it, I am willing to submit my conduct to the

judgment of the public, with a confidence that I will at least

receive due credit for the motives by which I was animated.

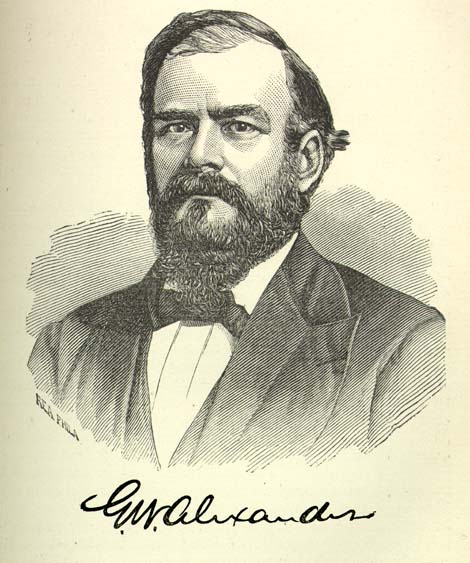

In the preparation of this book for the press, I have been greatly aided by the gentleman who has consented to act as my editor. Although during the war he was on the other side, he has interested himself most heartily in assisting me to get my narrative into the best shape for presentation to the public, and has shown a remarkable skill in detecting and correcting errors into which I had inadvertently fallen. I take pleasure in acknowledging my indebtedness to him.

The book, such as it is, mdash; and I have tried to make it all that such a

book should be by telling my story in as plain, straightforward, and

unpretending a style as I could command, mdash; is now, for good or ill, out

of my hands, and my adopted country people will have to decide for

themselves whether the writing of it was worth the while or not.

EDITOR'S PREFATORY NOTICE.

THE frank egotism of such a narrative as is contained in the volume

now in the hands of the reader needs no apology. Self-reliance, self-esteem,

and self-approbation, all were necessary for the

consummation of such adventures as those herein related; and, in the

opinion of the editor, a chief merit in the book is the perfect unreserve

with which its author gives to the world, not only the full particulars of

her numerous daring exploits and adventures, but the motives by

which she was influenced in undertaking them, and her impressions of

men and events. Since the author has not seen fit to do so, the editor

does not feel called upon to argue the question of propriety involved

in the appearance of a woman disguised in male attire on the battle-field;

but, with regard to some of the transactions in which Madame

Velazquez was engaged during the progress of the great civil war, a

few words of comment, explanatory rather than apologetic, seem to be

required.

Some of these transactions were of a character that, under ordinary

circumstances, would admit of no extenuation; but, in making up a

judgment concerning them, several important facts must be

constantly borne in mind. One of them is, that Madame Velazquez

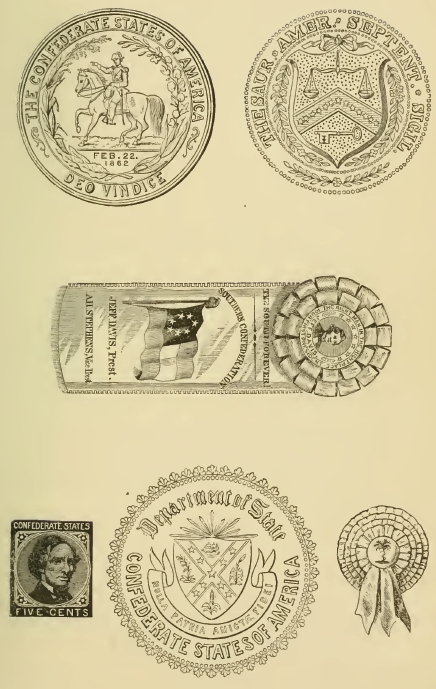

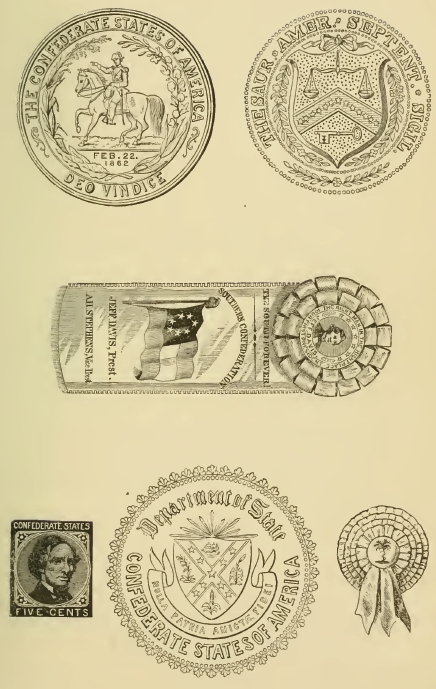

was acting as the agent of the only government to which she

acknowledged allegiance, and that she considered herself as justified

in aiding that government by every means in her power, as well by

fighting its enemies in the field, as by embarrassing them by such

attacks in the rear as are related in her narrative. This plea will, of

course, be

worth nothing to those who refuse to admit that for any

purposes the Confederacy had a right to exist. It is necessary,

however, to view matters of this kind from a different standpoint from

this. The fact that the Federal Government was compelled to

recognize the Confederates as belligerents, and was

compelled to hold official intercourse with them, renders

argument on this head unnecessary. Admitting that they

were belligerents, they were justified, within certain

limitations, in doing all in their power to defeat their enemies, not only by

opposing them with armies in the field, but by demoralizing

them by insidious attacks in the rear, and by hampering their

efforts to keep their ranks full, and to provide the ways and

means for maintaining the armies at the highest state of

efficiency. Whatever view non-combatants might have taken

of the war, the men who did the fighting were obliged to consider it,

in a great measure, as a trial of skill and valor, and

practically to disregard sentimental or political considerations.

From a military point of view, therefore, what was proper and

justifiable for one side, was proper and justifiable for the

other, and will so be considered by impartial critics.

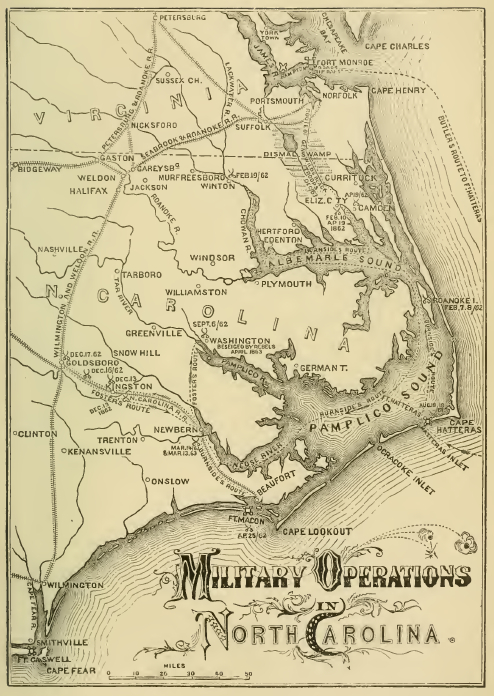

These remarks have particular reference to the portions of this

narrative which relate the experiences of Madame Velazquez as a

Confederate secret-service agent at the North during the last eighteen

or twenty months of the war. It will be noticed that she speaks with

undisguised contempt of some of her associates within the Federal

lines, mdash; associates without whose aid she could never have

accomplished the work she undertook. The unprejudiced reader will

have no difficulty in understanding that their position and hers were

vastly different. Some of these people were trusted officers of the

government, were sworn to loyalty and fidelity, and were in the

enjoyment of the full confidence of the public, as well as of their

immediate superiors. Others were men who were loud in their

protestations of loyalty, but who, while eager to be recognized as

stanch supporters of the Federal government, were, for the sake of

gain, secretly engaged in aiding

the enemy by every means in their power. These people, and the

shrewd, sharp woman who made use of them for the furtherance of the

work she undertook to perform for the purpose of aiding the

government to which she had given her allegiance in carrying on a

gigantic contest, are surely not to be judged by the same standard;

and that Madame Velazquez does not hesitate to relate the details of

her transactions as a Confederate agent and spy, proves that she, at

least, does not consider that she has done anything to be ashamed of,

and is willing that her conduct shall be freely criticised.

To many readers, the story of Madame Velazquez's experiences in

camp and on the battle-field while disguised as a Confederate officer,

will, from the peculiarities of her position, have a particular interest. In

the opinion of the editor, however, the most important part of the

book is that in which a revelation is made, now for the first time, of

the exact manner in which the Confederate secret-service system at

the North was managed. There is no feature of the civil war that more

needs to have light thrown on it than this; and, as the story which

the heroine of the adventures herein set down recites, is an

exceedingly curious one, it is deserving of the special consideration

of the public, both North and South.

The editor of this volume was in the United States naval service

from near the beginning to the end of the civil war; and as he gave his

adhesion to the Union cause from principle rather than passion, and

as he has never, either during the war or since its close, had other

than the kindest feelings towards those who took the other side,

under a sincere conviction that they were right, he not only had had no

hesitation in preparing the narrative of Madame Velazquez for the press,

but he feels that he can appreciate the motives which, from first to last,

seem to have actuated her. The Southern people made a great mistake

when they inaugurated the war; but it does not become those who

fought in the Federal ranks to doubt, at this late day, the sincerity or

honesty of purpose of the vast majority of them.

The great American civil war was an event that deserves to be

judged dispassionately; and to judge it dispassionately, it is

necessary that the people of both sections should understand each

other better than they did while the conflict was being waged, or,

indeed, than they do now. It is especially important that the people of

the North, being the victors, and being in a great measure responsible

for the present and future good government of the South, and for a

proper appreciation there of the advantages of a cordial and fraternal,

as well as a political union, should study the war from a Southern

point of view. The present volume, the editor believes, is not only a

most interesting narrative of adventure of a very exceptional kind, but

it is an important and valuable contribution to the history of the war.

Madame Velazquez, whose enthusiasm for the cause of Southern

independence induced her to discard the garments of her sex, and to

assume male attire for the purpose of appearing upon the battle-field,

is a typical Southern woman of the war period; and there are

thousands of officers and soldiers who fought in the Confederate

armies who can bear testimony, not only to the valor she displayed in

battle, and under many circumstances of difficulty and danger, but to

her integrity, her energy, her ability, and her unblemished reputation.

Upon these points, however, it is not necessary to dilate; her story

will speak for itself, and that it is a true story in every particular, there

are abundant witnesses whose testimony will not be disputed.

As Madame Velazquez is a typical Southern woman of the war

period, so her story furnishes a curious inside view of the

Confederacy, and it throws much light on a great number of obscure

points in its history. For this reason, if no other, it will deserve the

attention of Northern readers, who will find many things stated in it

which it is well for them to know. No commendation of any kind is

needed to command for it the consideration of the people of the

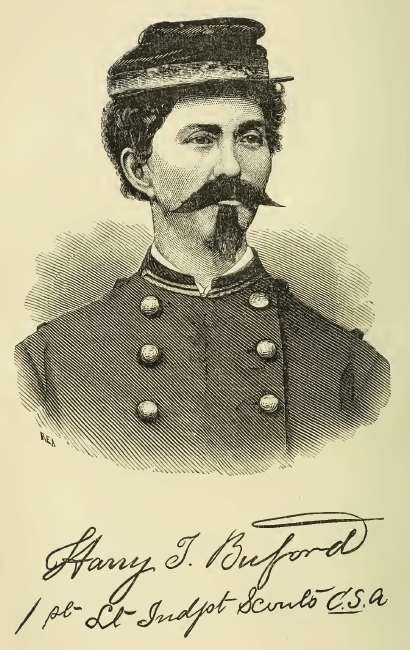

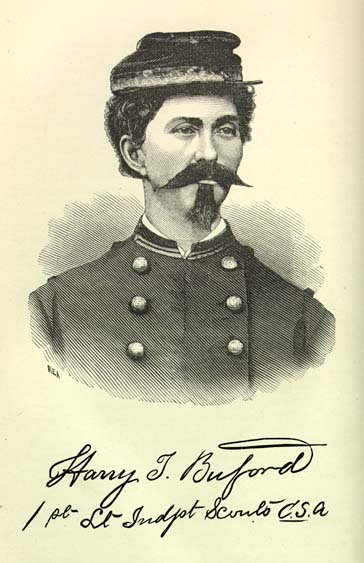

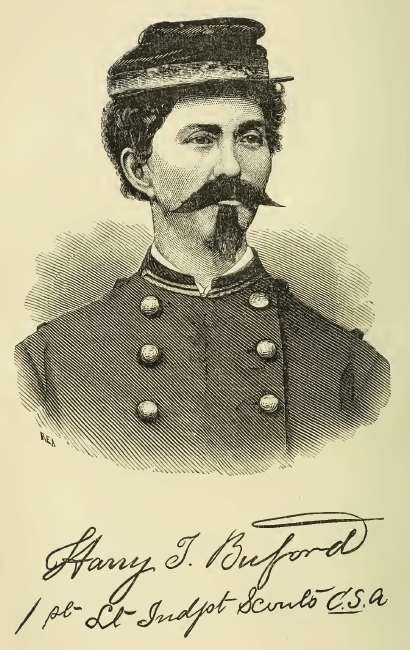

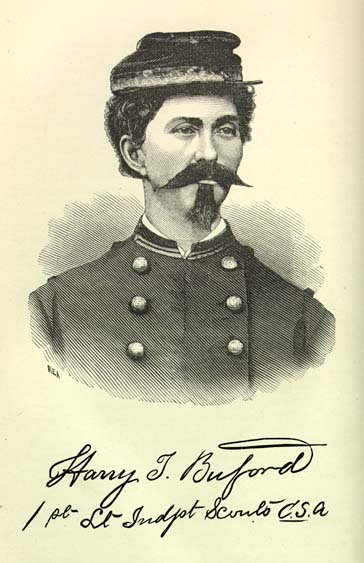

South. From the breaking out of the war to its close, the Confederate

cause had no more

enthusiastic or zealous supporter than the woman who was known as

Lieutenant Harry T. Buford. According to her opportunities, she

labored with unsurpassed zeal and efficiency, and with a

disinterestedness that cannot but be admired.

With regard to the part performed by the editor in preparing this

work for the press, it may be proper to say a few words. The

manuscript, when it was placed in his hands, was found to be very

minute and particular in some places, and rather meagre in others,

where particularity seemed desirable. Having undertaken to get this

material into proper shape, correspondence was opened with

Madame Velazquez, and a number of interviews with her were had. A

general plan having been agreed upon, it was left entirely to the

judgment of the editor what to omit or what to insert, Madame

Velazquez agreeing to supply such information as was needed to make

the story complete, in a style suitable for publication. From her

correspondence, and from notes of her conversations, a variety of very

interesting details, not in the original manuscript, were obtained and

incorporated in the narrative. The editor, also, in several places has

corrected palpable errors of time and place, and has added a few facts

not supplied by the author. These corrections and additions have been

made after consultation with the author, and with her entire

approbation. In preparing her manuscript, Madame Velazquez seems to

have endeavored to narrate the incidents of her career in the fullest

manner possible; and it consequently contains a large amount of

matter which can be of but very little, if any, interest to the general

public. It has been necessary, therefore, while expanding in some

places, to make large excisions in others; but the story is such an

extraordinary one, in many of its aspects, that it has been judged

better to give it in too great fulness, rather than to omit what the

purchasers of the book would have a right to find in it. The excisions

have, therefore, been carefully made, and it is believed that nothing

has been omitted that is of value or importance. A few expressions that

might needlessly give

offence, have either been stricken out or altered, while some,

which persons of severe taste may object to, have been permitted

to remain as they were originally written, they being in some

way characteristic of the writer, or of the circumstances under

which she was placed. While Madame Velazquez does not

pretend to any literary accomplishments, her style has a certain

flavor which is far from unpleasant; and the editor has been

careful, in making such changes and alterations as have seemed

necessary, to retain the author's own words wherever practicable.

Owing to the loss of her diary, Madame Velazquez was

compelled to write her narrative entirely from memory, which will account

for the errors to which allusion has been made. Indeed, considering

the multiplicity of events, it is very remarkable that she has been able

to relate her story with any degree of accuracy. It is possible that,

despite the pains that have been taken to make the narrative exact in

every particular with regard to its facts, a few errors may have been

permitted to remain uncorrected. These errors, however, are not

material, and do not in any way impair the interest of the story.

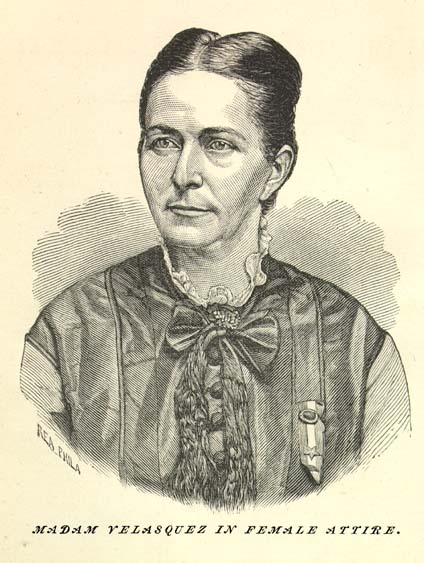

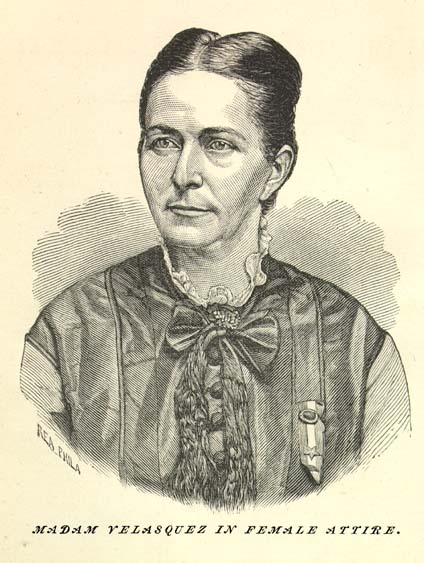

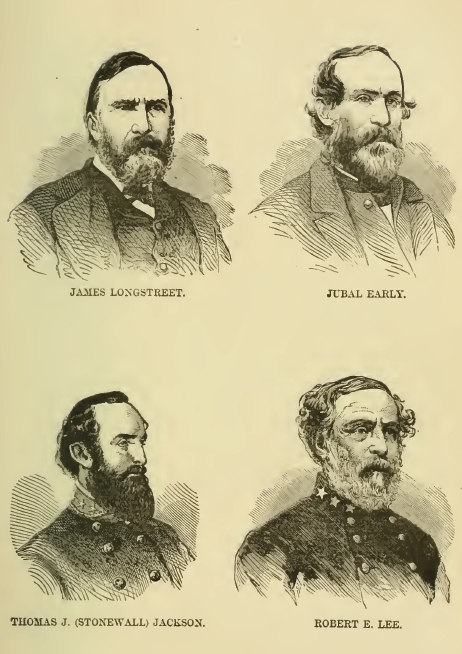

Madame Velazquez is a very remarkable woman, and some account

of her personal appearance, other than can be obtained from the

portraits of her which are given in this book, will doubtless be

appreciated by the reader. She is rather slender, something above

medium height, has more than the average of good looks, is

quick and energetic in her movements, and is very vivacious in

conversation. Her frame is firmly knit, and she is evidently endowed

with great powers of physical endurance. Those who have seen her

in male attire say that her skill in disguising herself was very great, and

that she readily passed for a man. At the same time she is anything

but masculine, either in appearance, manners, or address. She is a

shrewd, enterprising, and energetic business woman, and in society is

a brilliant and most entertaining conversationalist, abounding in a fund of racy

anecdotes, and endowed with a mimetic power that enables her to relate her

anecdotes in the most telling manner. In New York, Philadelphia, and

other Northern cities, as well as throughout the South and West, she

has a large number of very warm friends, who hold her in the highest

esteem on account of her eminent talents, her fascinating social

qualities, and her unblemished reputation. It is to be hoped that the

publication of the story of her checkered career will have the effect of

increasing, rather than of diminishing, the number of these friends.

Her story is a most remarkable one, in nearly every respect. During the

war a number of women, on both sides, from time to time, performed

spy duty, and several of them are said to have occasionally assumed

male attire. Madame Velazquez, however, it is believed, is the only one

of her sex, who, for any length of time, wore a masculine garb, or who

participated as a combatant in a series of hard-fought battles.

Narratives of the adventures of several heroines on the Federal side

have been published, but none of them will at all compare in extent and

variety of interest with the volume now before the reader, which has an

additional claim on the regards of the public as being the only

authentic account of the career of a Confederate heroine that has

issued from the press.

CONTENTS.

- CHAPTER I.

CHILDHOOD.

The Woman in Battle. — Heroines of History. — Joan of Arc. — A Desire to

emulate Her. — The Opportunity that was Offered. — Breaking out of the War

between the North and the South. — Determination to take Part in the Contest.

— A noble Ancestry. — The Velazquez Family. My Birth at Havana. — Removal

of my Family to Mexico. — The War between the United States and Mexico. —

Loss of my Father's Estates. — Return of the Family to Cuba. — My early

Education. — At School in New Orleans. — Castles in the Air. — Romantic

Aspirations. — Trying to be a Man. — Midnight Promenades before the Mirror in Male Attire. . . . . 33

-

CHAPTER II.

MARRIAGE.

My Betrothal. — Love Matches and Marriages of Convenience. — Some new

Ideas

picked up from my Schoolmates. — A new Lover appears upon the Field — I

Figure as a Rival to a Friend. — Love's Young Dream. — A new Way of

Popping

the Question. — A Clandestine Marriage. — Displeasure of my Family. — Life

as the Wife of an Army Officer. — The Mormon Expedition. — Birth of my

first

Child, and Reconciliation with my Family. — Commencement of the War

between the North and South. — Death of my Children. — Resignation of my

Husband from the Army. — My Determination to take Part in the coming

Conflict as a Soldier. — Opposition of my Husband to my Schemes. . . . . 43

-

CHAPTER III.

ASSUMING MALE ATTIRE.

A Wedding Anniversary. — Preparing for my Husband's Departure for the

Seat of War. — My Desire to accompany Him. — His Arguments to dissuade

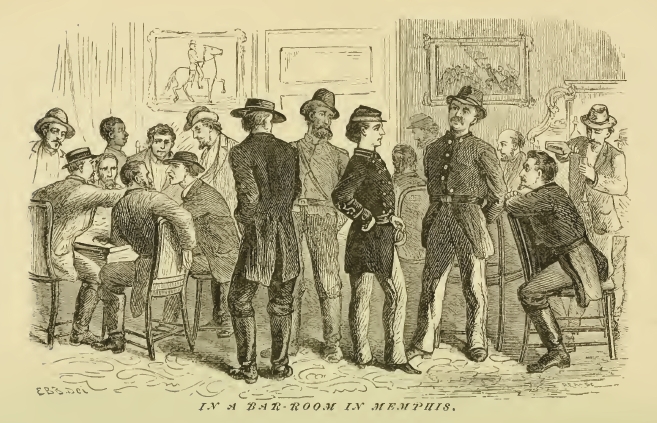

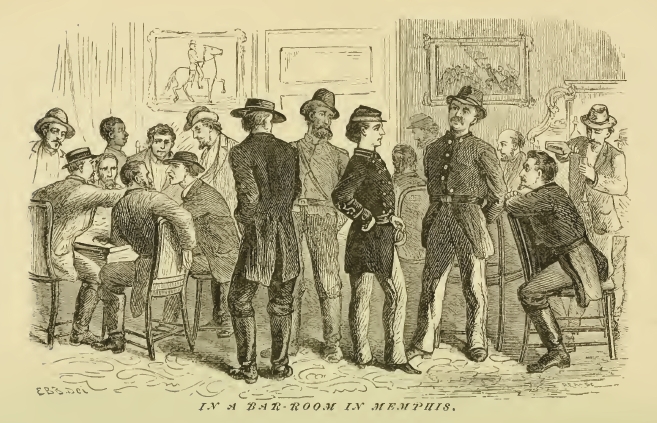

Me. — My First Appearance in Public in Male Attire. — A Barroom

Scene. — Drinking Success to the Confederacy. — My First Cigar.

— A Tour of the Gambling-Houses and Drinking-Saloons. — The

unpleasant Points of Camp Life set forth in strong Colors. — Departure of

my Husband. — Donning Male Attire. — My First Suit of Male Clothing.

— Description of my Disguise. — The Practicability of a Woman

disguising herself effectively. — Some of the Features of Army Life. —

What Men think of Women Soldiers . . . . .52

-

CHAPTER IV.

DISGUISED AS A CONFEDERATE OFFICER.

Preparing a Military Outfit. — Consultations with a Friend. — Argument

against my proposed Plan of Action — Assuming the Uniform of a

Confederate

Officer. — A Scene in a Barber's Shop. — How young Men try to make their

Beards Grow. — Taking a social Drink. — A Game of Billiards. — In a Faro

Bank. — Some War Talk. — Drinks all Around. — The End of an exciting

Day. — Making up a Complexion. — A false Mustache. — Final

Preparations. — Letters from Husband and Father. — Ready to start for the

Seat of War. . . . . 61

-

CHAPTER V.

RECRUITING.

My Plan of Action. — On the War Path. — In Search of Recruits in

Arkansas. — The Giles Homestead. — Sensation caused by a Soldier's

Uniform. — A prospective Recruit. — Bashful Maidens. — A nice little

Flirtation. — Learning how to be agreeable to the Ladies. — A Lesson in

Masculine Manners. — A terrible Situation. — Causeless Alarm. — The young

Lady becoming Sociable. — A few Matrimonial Hints. — The successful

Commencement of a Soldier's Career. — Anticipations of future

Glory. — Dreamless Slumbers. . . . . 70

-

CHAPTER VI.

-

A WIDOW.

-

Flirtation and Recruiting. — My brilliant Success in enlisting a

Company. —

Embarkation for New Orleans. — Letter from My Husband. — Change of

Plans. —

Cheered while passing through Mobile. — Arrival at

Pensacola. — Astonishment

of My Husband. — Sudden Death of my Husband by the Bursting of a

Carbine. —

Determination to go to the Front. — A fascinating Widow. — A Lesson in

Courtship. — Starting for the Seat of War. — Unpleasant Companions. — A bit

of Flirtation with a Columbia Belle. — In Charge of a Party of Ladies

and Children at Lynchburg. — Arrival in Richmond. — Another Lady in Love

with me. — The Major wants to make a Night of it. — A quiet Game of

Cards. — Off for the Battle-field. . . . . 82

-

CHAPTER VII.

-

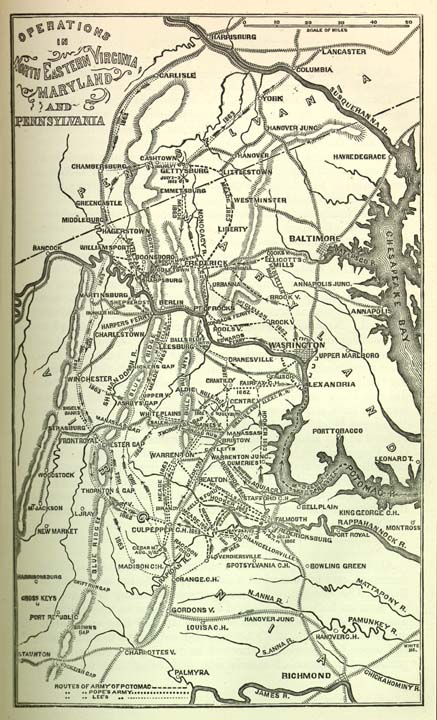

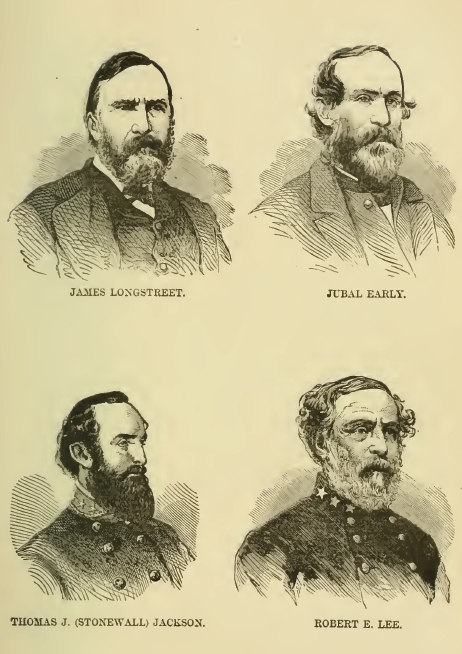

THE BATTLE OF BULL RUN.

-

Joining the Army in the Field. — Trying to get a Commission. — The

Skirmish at Blackburn's Ford. — Burying the Dead. — I attach myself to

General Bee's Command. — The Night before the Battle of Bull Run. —

A sound Sleep. — The Morning of the Battle. — A magnificent Scene. —

The Approach of the Enemy. — Commencement of the Fight. — An Exchange of

Compliments between old Friends. — Bee's Order to fall back, and his

Rally. — "Stonewall" Jackson. — The Battle at its Fiercest. — The Scene at

Midday. — Huge Clouds of Dust and Smoke. — Some

tough Fighting. — How Beauregard and Johnston rallied their Men. — The

Contest for the Possession of the Plateau. — Bee and Bartow

Killed. — Arrival of Kirby Smith with Re-enforcements. — The Victory

Won. — Application for Promotion. — Return to Richmond. . . . . 95

-

CHAPTER VIII.

-

AFTER THE BATTLE.

-

Erroneous Ideas about the War. — Some of the Effects of the Battle of

Bull

Run. — The Victory not in all Respects a Benefit to the Cause of the

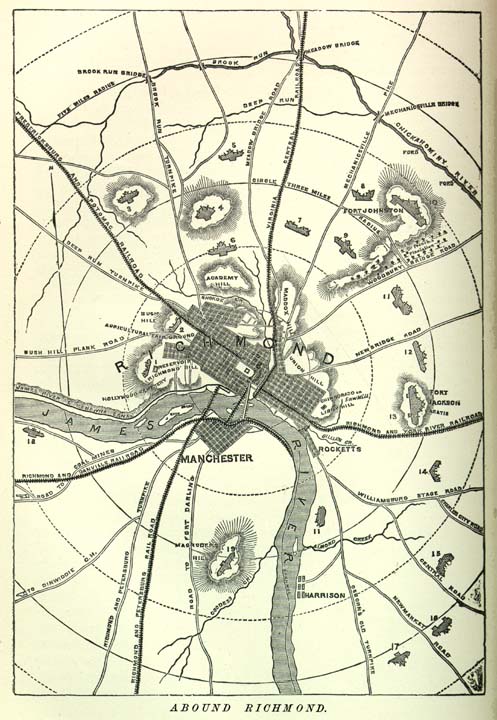

Confederacy. — Undue Elation of Soldiers and Civilians. — Richmond

Demoralized. — A Quarrel with a drunken Officer. — An Insult Resented. — I

leave Richmond. — Prospect of another Battle. — Cutting a Dash in

Leesburg. — A little Love Affair. — Stern Parents. — A clandestine

Meeting. — Love's young Dream. — Disappointed Affections. — In front of the

Enemy once More. — A Battle expected to come off. . . . . 107

-

CHAPTER IX.

-

THE BATTLE OF BALL'S BLUFF.

-

An Appetite for Fighting. — The Sensations of the Battle-field. — My

second

Battle. — The Conflict at Ball's Bluff. — My Arrival at General Evans's

Headquarters. — Meeting an old Acquaintance. — Hospitalities of the

Camp. —

The Morning of the Battle. — Commencement of the Fight. — A fierce

Struggle. — In Charge of a Company. — A suspicious Story. — Bob figures as a

Combatant. — Rout of the Enemy. — The Federals driven over the Bluff into

the River. — I capture some Prisoners. — A heart-rending

Spectacle. — Escape of Colonel Devens, of the Fifteenth Massachusetts

Regiment, by swimming

across the River. — Sinking of the Boats with the wounded Federals in

Them. —

Night, and the End of the Battle. . . . . 115

-

CHAPTER X.

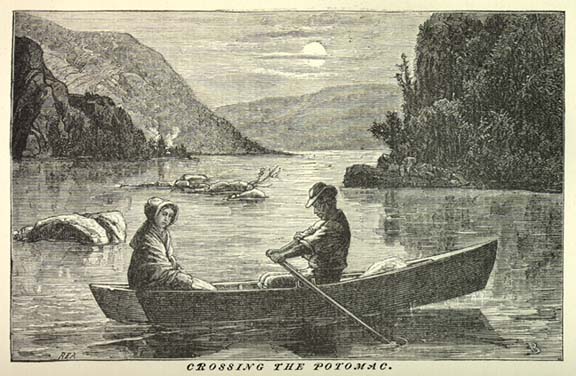

FIRST EXPERIENCES AS A SPY.

Reaction after the Excitements of a Battle. — The Necessity for mental

and

bodily Occupation. — I form a new Project. — War as we imagine it, and as

it

Is. — Fighting not the only Thing to be Done. — The Dreams of Youth, and

the Realities of Experience. — The Secret of Success. — The Difficulties

which the Confederate Commanders experienced in obtaining Information of

the

Movements of the Enemy. — What a Woman can do that a Man Cannot. — A

Visit to Mrs. Tyree. — The only Way of keeping a Secret. — I assume the

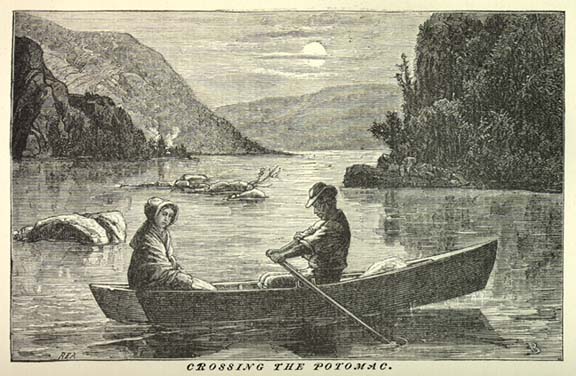

Garments of my own Sex again as a Disguise. — Getting across the Potomac

at

Night. — Asleep in a Wheat-Stack. — A suspicious Farmer. — A Friend in

Need. — Maryland Hospitality. — Off for Washington. . . . . 126

-

CHAPTER XI.

IN WASHINGTON.

Inside the Enemy's Lines. — Arrival at the Federal Capital. — Renewing an

Acquaintance with an old Friend. — What I found out by a judicious

System of Questioning. — The Federal Plans with regard to the

Mississippi. —

An Attack on New Orleans Surmised. — A Tour around Washington. — Visit to

the War Department, and Interview with Secretary Cameron and General

Wessells. — An Introduction to the President. — Impressions of Mr.

Lincoln. — I succeed in finding out a Thing or two at the

Post-Office. — Sudden Departure from Washington. — Return to

Leesburg. — Departure for Columbus, Kentucky. . . . . 136

-

CHAPTER XII.

ACTING AS MILITARY CONDUCTOR.

At Memphis Again. — Ending my first Campaign. — My Friend the

Captain and I

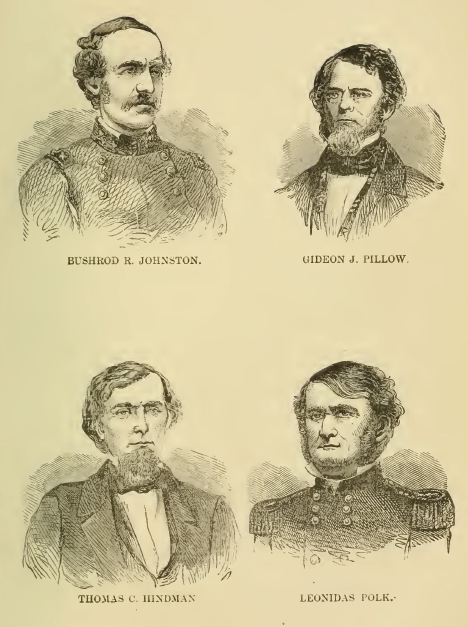

exchange Notes. — I reach Columbus, and report to General Leonidas

Polk. — Assigned to Duty as Military Conductor. — Unavailing

Blandishments of the

Women. — A mean Piece of Malice. — General Lucius M. Polk tries

to play a

Trick on Me. — The Path of Duty. — The General put under

Arrest. — An

Explanation concerning a one-sided Joke. — I become dissatisfied, and

tender

my Resignation. — A Request to Return to Virginia and enter the Secret

Service. — Acceptance of my Resignation. — The Lull before the

Storm. . . . . 145

-

CHAPTER XIII.

A MERRY-MAKING.

In Search of active Employment. — On the Road to Bowling Green,

Kentucky. —

My travelling Companions. — A Halt at Paris. — A hog-killing and

corn-shucking Frolic. — Dancing all Night in the School-house. — A

Quilting-Party. — My particular Attentions to a Lady. — The other Girls

Unhappy. — The Reward of Gallantry. — What General Hardee had to say to

Me. — The Woodsonville Fight. — On the back Track for Fort Donelson. . . .

. 154

-

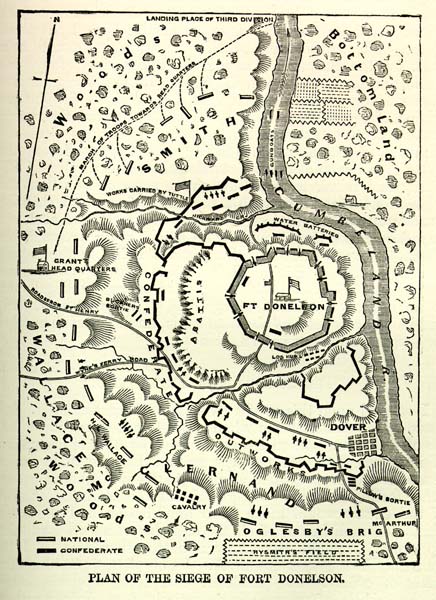

CHAPTER XIV.

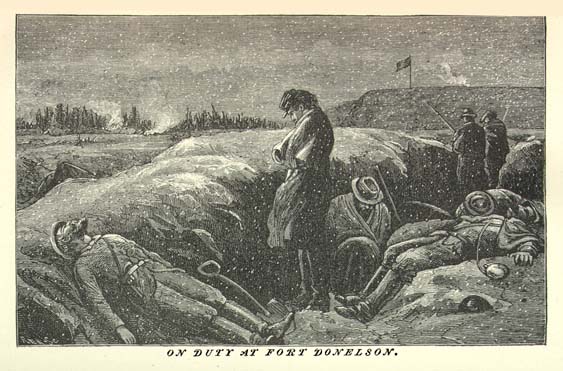

THE FALL OF FORT DONELSON.

The Spirit of Partisanship. — My Opinions with regard to the

Invincibility of the Southern Soldiers. — Unprepared to sustain the

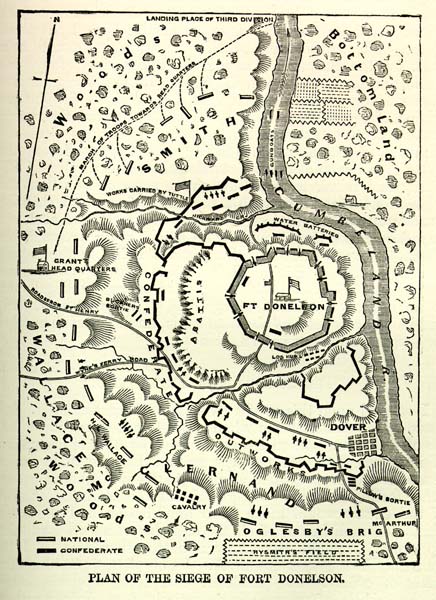

Humiliation of Defeat. — The Beginning of the End. — At Fort

Donelson. — The Federal Attack Expected. — Preparations for the

Defence. — The Garrison confident of their Ability to

hold the Fort. — The Difference between Summer and Winter Campaigning. —

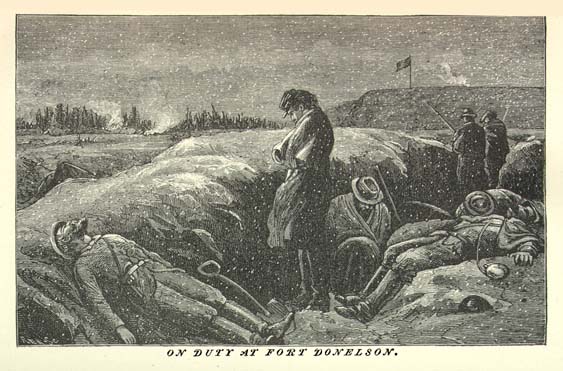

Enthusiasm supplanted by Hope and Determination. — My Boy Bob and I go

to Work in the Trenches. — Too much of a Good Thing. — Dirt-digging not

exactly in my Line. — The Federals make their Appearance. — The Opening of

the Battle. — On Picket Duty in the Trenches at Night. — Storm of Snow and

Sleet. — The bitter Cold. — Cries and Groans of the Wounded — My Clothing

stiff with Ice. — I find Myself giving Way, but manage to endure until

the

Relief Comes. — Terrible Suffering. — Singular Ideas. — A Four Days'

Battle. — The Confederate Successes on the first and second Days. — The

Gunboats driven Off. — Desperate Fighting on the third Day. — A breathing

Spell. — The Confederates finally driven back into the Fort. — It is

resolved to Surrender. — Generals Floyd and Pillow make their

Escape. — General Buckner surrenders to General Grant. — Terrible Scenes

after the Battle is Over. — The Ground strewn for Miles with Dead and

Dying. — Wounded Men crushed by the Artillery Wagons. — The Houses of

the Town of Dover filled with Wounded. — My Depression of Spirits on

Account of the Terrible Scenes I had Witnessed. . . . . 161

-

CHAPTER XV.

DETECTION AND ARREST IN NEW ORLEANS.

Taking a Rest at Nashville. — Again on the March. — I join General A. S.

Johnston's Army. — Wounded in a Skirmish. — Am afraid of having my Sex

discovered, and leave suddenly for New Orleans. — In New Orleans I am

suspected of being a Spy, and am Arrested. — The Officer who makes the

Arrest in Doubt. — The Provost Marshal orders my Release. — I am again

arrested by the Civil Authorities on suspicion of being a Woman. — No Way

out of the Scrape but to reveal my Identity. — Private Interview with Mayor

Monroe. — The Mayor Fines and Imprisons Me. — I enlist as a Private

Soldier. — On arriving at Fort Pillow, obtain a Transfer to the Army of East

Tennessee. . . . . 174

-

CHAPTER XVI.

AN UNFORTUNATE LOVE AFFAIR.

Again at Memphis. — Public and private Difficulties. — Future Prospects.

— Arrival of my Negro Boy and Baggage from Grand Junction. — A new

uniform Suit. — Prepared once more to face the World. — I fall in with an

old Friend. — An Exchange of Compliments. — Late Hours. — Some of the

Effects of Late Hours. — Confidential Communications. — The Course of true

Love runs not Smooth. — I renew my Acquaintance with General Lucius M.

Polk. — The General disposed to be Friendly. — My Friend and I call on his

Lady-love and her Sister. — Surprising Behavior of the young Lady. —

A genuine Love-letter. — A Secret Disclosed. — Incidents of a

Buggy Ride. — A Declaration of Love. — Lieutenant H. T. Buford as

a

Lady-killer. — Why should Women not pop the Question as well as Men? — A

melancholy Disclosure for my Friend. — I endeavor to encourage Him. — A

Visit to the Theatre and an enjoyable Evening. — I meet a Friend from New

Orleans, and endeavor to

remove any Suspicions with regard to my Identity from his

Mind. — Progress

of my Love-affair with Miss M. — The young Lady and I have our Pictures

Taken. — I proceed to Corinth for the Purpose of taking Part in the

expected

Battle. — The Confederate Army advances from Corinth towards Pittsburg

Landing. . . . . 183

-

CHAPTER XVII.

THE BATTLE OF SHILOH.

A Surprise upon the Federal Army at Pittsburg Landing Arranged. — A brilliant

Victory Expected. — I start for the Front, and encamp for the Night at

Monterey. — My Slumbers disturbed by a Rain-storm. — I find General Hardee

near Shiloh Church, and ask Permission to take a Hand in the Fight. — The

Opening of the Battle. — Complete Surprise of the

Federals. — I see my Arkansas Company, and join It. — A Lieutenant being

killed, I take his Place, amid a hearty Cheer from the Men. — A Secret

Revealed. — I fight through the Battle under the Command of my

Lover. — Furious Assaults on the Enemy's Lines. — The Bullets fly Thick and

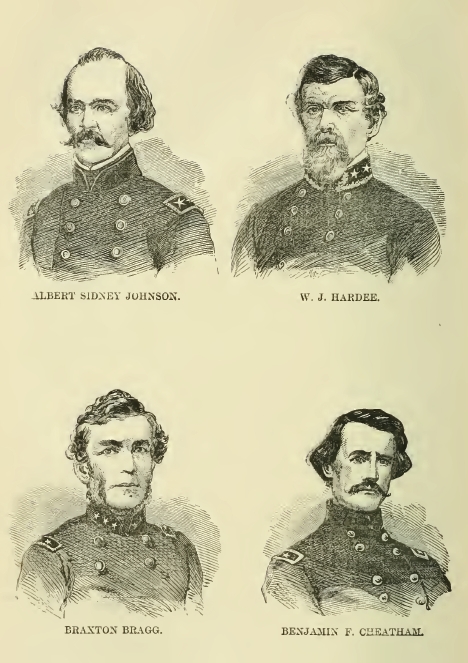

Fast. — General Albert Sydney Johnston Killed. — End of the First Day's

Battle, and Victory for the Confederates. — Beauregard's Error in not pursuing

his Advantage. — I slip through the Lines after Dark, and watch what is going

on at Pittsburg Landing. — The Gunboats open Fire. — Unpleasant Effect of

Shells from big Guns. — Utter Demoralization of the Federals. — Arrival of

Buell with Re-enforcements. — General Grant and another general Officer pass

near Me in a Boat, and I am tempted to take a Shot at Them. — I return to

Camp, and wish to report what I had seen to General Beauregard, but am dissuaded

from doing so by my Captain. — Uneasy Slumbers. — Commencement of the Second

Day's Fight. — The Confederates unable to contend with the Odds against

Them. — A lost Opportunity. — The Confederates defeated, and compelled to

retire from the Field. — I remain in the Woods near the Battle-field all

Night. . . . . 200

-

CHAPTER XVIII.

WOUNDED.

The Morning after the Battle of Shiloh. — My Return to Camp. — A Letter from

my Memphis Lady-love. — A sad Case. — My Boy Bob Missing. — I start out to

search for Him. — A runaway Horse, and a long Tramp through the Mud. —

Return to the Battle-field. — Horrible Scenes along the Road. — Out on a

Scouting Expedition. — Burying the Dead. — I receive a severe Wound. — A

long and painful Ride back to Camp. — My Wound dressed by a Surgeon, and my

Sex discovered. — A Fugitive. — Arrival at Grand Junction. — Crowd of

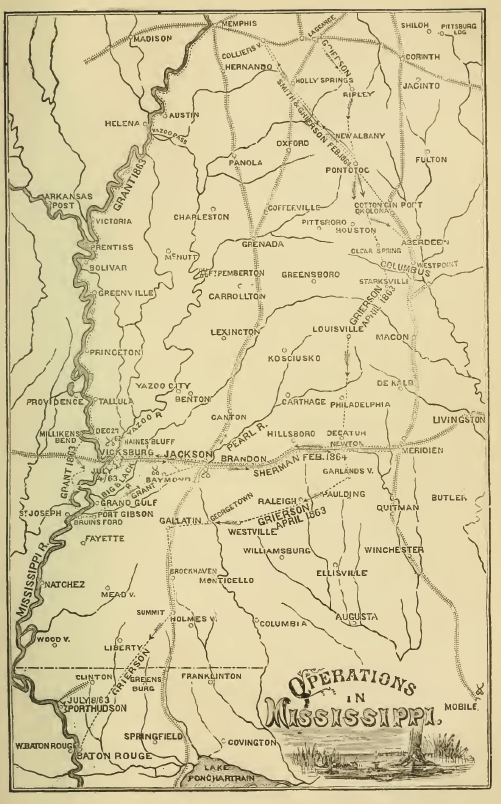

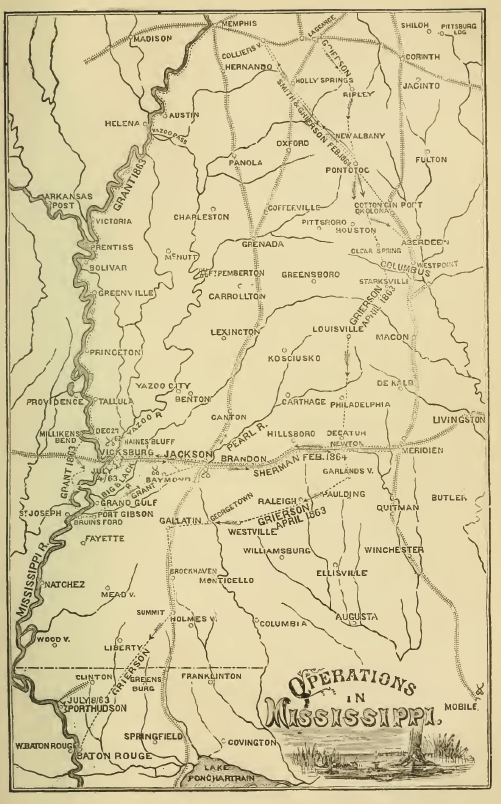

anxious Inquirers. — Off for New Orleans. — Stoppages at Grenada, Jackson,

and Osyka on Account of my Wound. — The Kindness of Friends. — Fresh Attempt

to reach New Orleans. — Unsatisfactory Appearance of the Military Situation.

— The Passage of the Forts by the Federal Fleet. — A new Field of

Employment opened for Me. — I resume the Garments of my Sex. . . . . 219

-

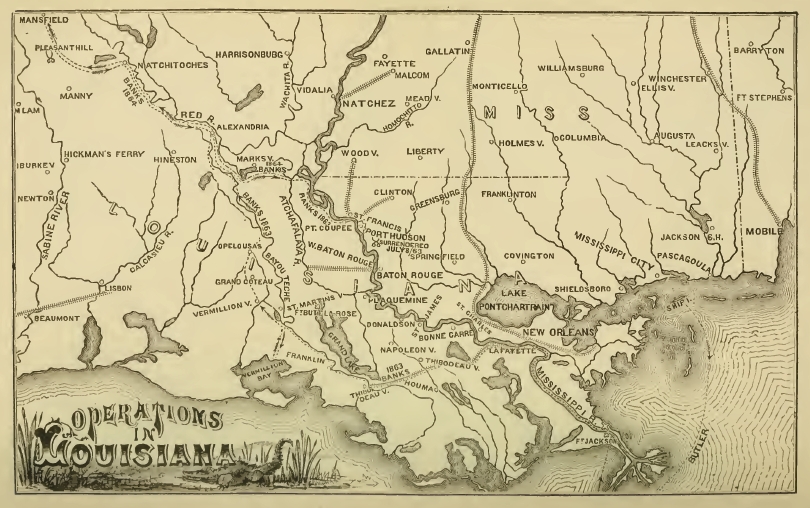

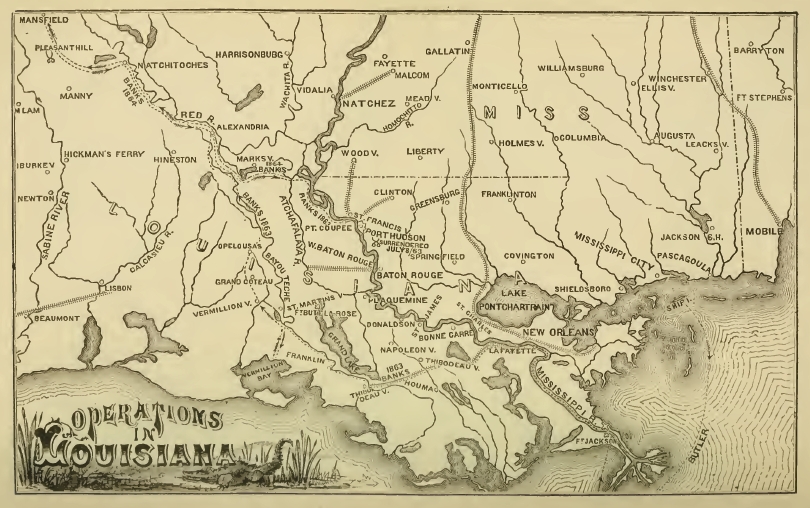

CHAPTER XIX.

THE CAPTURE OF NEW ORLEANS, AND BUTLER'S ADMINISTRATION.

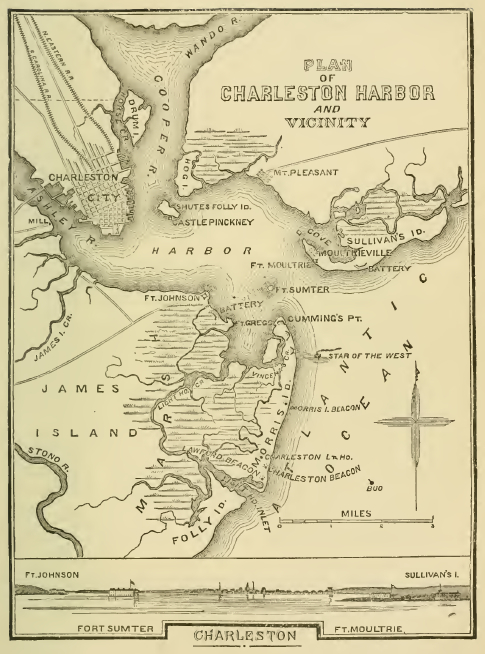

Capture of Island No. 10. — The impending Attack on New Orleans. — The

unsatisfactory Military Situation. — Confidence of Everybody in the River

Defences. — My Apprehensions of Defeat. — The Fall of New

Orleans. — Excitement in the City on the News of the Passage of the Forts

being Received. — I resolve to abandon the Career of a Soldier, and to resume

the Garments of my own Sex. — Appearance of the Fleet opposite the

City. — Immense Destruction of Property. — My Congratulations to Captain

Bailey of the Navy. — Mayor Monroe's Refusal to raise the Federal

Flag. — General Butler assumes Command of the City. — Butler's Brutality. —

I procure the foreign Papers of an English Lady, and strike up an Acquaintance

with the Provost Marshal. — Am introduced to other Officers, and through

them gain Access to Headquarters. — Colonel Butler furnishes me with the

necessary Passes to get through

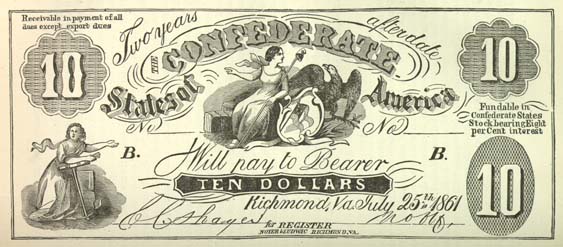

the Lines. — I drive an active Trade in Drugs and Confederate Money while

carrying Information to and Fro. — Preparations for a grand final Speculation

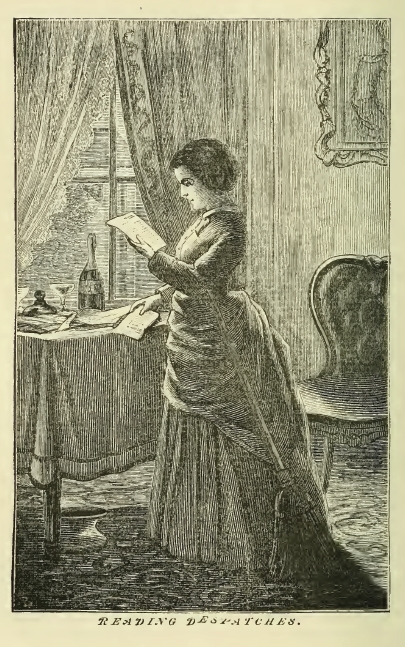

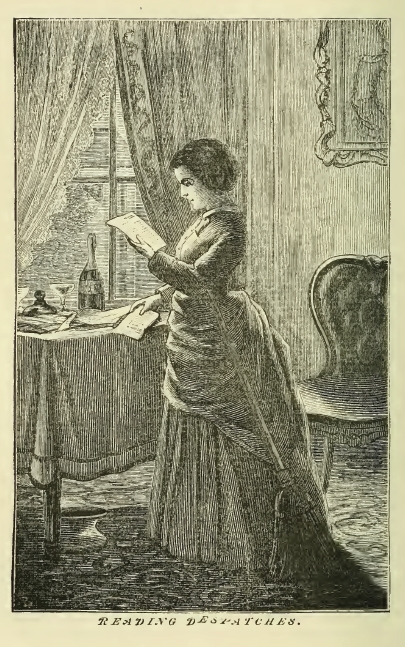

in Confederate Money. — I am intrusted with a Despatch for the "Alabama," and

am started for Havana. . . . . 232

-

CHAPTER XX.

A VISIT TO HAVANA.

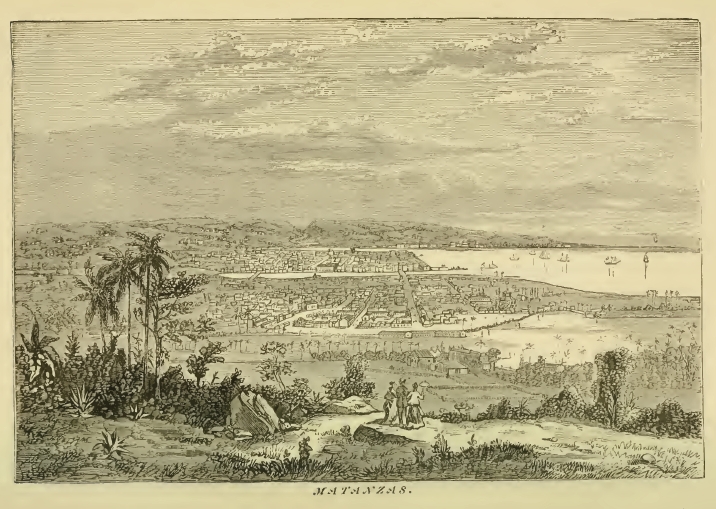

A Trip to Havana. — My Purposes in making the Journey. — The Results of a

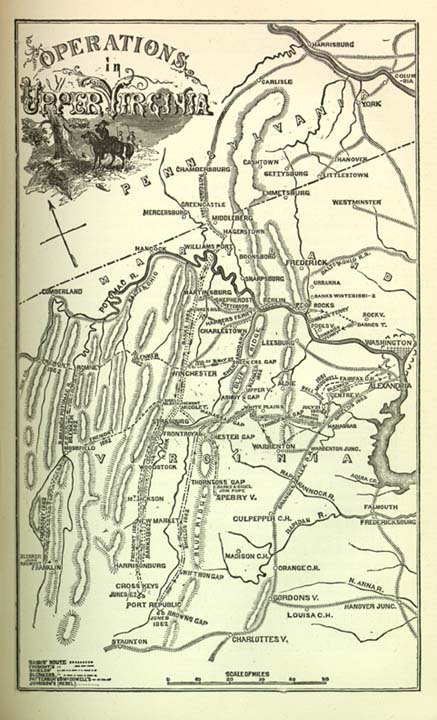

Year of Warfare. — Gloomy Prospects. — A Gleam of Hope in Virginia. — The

Delights of a Voyage on the Gulf of Mexico. — The Island of Cuba in

Sight. — The Approach to Havana. — I communicate with the Confederate

Agents and deliver my Despatches. — An Interchange of valuable

Information. — The Business of Blockade-running and its enormous

Profits. — The Injury to the Business caused by the Capture of New

Orleans. — My Return to New Orleans and Preparation for future Adventures. . .

. . 244

-

CHAPTER XXI.

A DIFFICULTY WITH BUTLER. — ESCAPE FROM NEW ORLEANS.

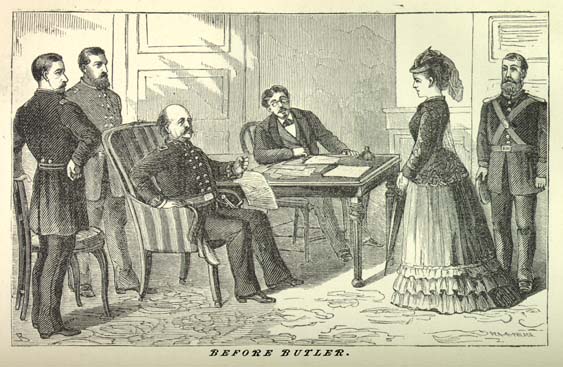

Butler's Rule in New Orleans. — A System of Terrorism. — My Acquaintance

with Federal Officers. — I resume the Business of carrying Information

through the Lines. — A Trip to Robertson's Plantation for the Purpose of

carrying a Confederate Despatch. — A long Tramp after Night. — Some of the

Incidents of My Journey. — The Alligators and Mosquitoes. — Arrival at my

Destination, and Delivery of the Despatch to a Confederate Officer. — My

hospitable Entertainment by Friends of the Confederacy. — My Return to

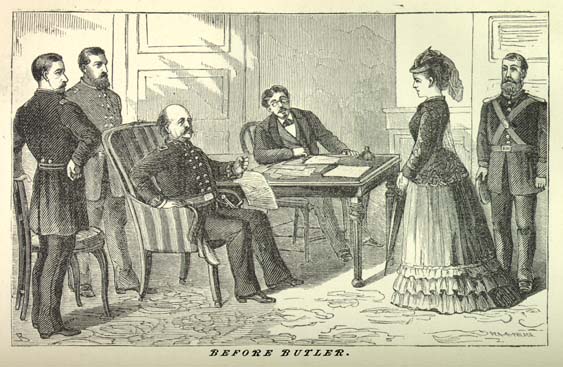

New Orleans. — Capture of the Bearer of my Despatch, and my Arrest. — I am

taken before Butler, who endeavors to extort a Confession from Me. — Butler

as a Bully. — I refuse to confess, and am ordered to be imprisoned in

the

Custom-House. — My Release, through the Intercession of the British

Consul. — I resolve to leave New Orleans, for fear of getting into further

Trouble. — A Bargain with a Fisherman to take me across Lake Pontchartrain. —

My Escape from Butler's Jurisdiction. . . . . 253

-

CHAPTER XXII.

CARRYING DESPATCHES.

Uncertainties of the Military Situation. — I go to Jackson,

Mississippi. —

Burning of the Bowman House in that Place by Breckenridge's Soldiers.

— The unpleasant Position in which Non-combatants were Placed. — A Visit

to the Camp of General Dan. Adams, and Interview with that Officer. — I

visit Hazlehurst, and carry a Message to General Gardner at Port

Hudson. — Recovery of my Negro Boy Bob. — General Van Dorn's Raid on

Holly Springs. — I resolve to return to Virginia. — The Results of two

Years of Warfare. — Dark Days for the Confederacy. — Fighting against

Hope. . . . . 268

-

CHAPTER XXIII.

UNDER ARREST AGAIN.

Commencement of a new Campaign. — Return to Richmond, and Arrest on

Suspicion of being a Woman. — Imprisonment in Castle Thunder. — Kindness

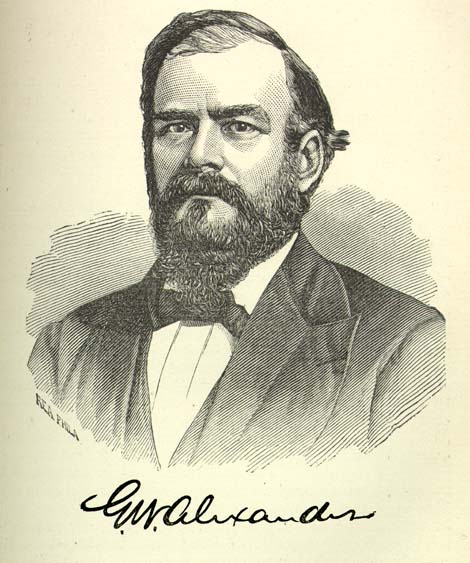

to Me of

Major J. W. Alexander and his Wife. — I refuse to resume the

Garments of

my Sex. — I am released, and placed on Duty in the Secret Service

Corps. — General Winder, the Chief of the Secret Service

Bureau. — A

remarkable Character. — General Winder sends me with blank Despatches to

General Van Dorn to try Me. — A Member of the North Carolina Home Guards

attempts to arrest Me at Charlotte. — I resist the Arrest, and am

permitted to

Proceed. — The Despatches delivered to Van Dorn in Safety. — My Arrest in

Lynchburg. — The Rumors that were in Circulation about Me. — I am pestered

with curious Visitors. — A Couple of Ladies deceived by a simple Trick. —

A comical Interview with an old Lady. — She declares herself insulted. —

An insulting Letter from a general Officer. — My indignant Reply, and

Offer

to fight Him. — I obtain my Release, and leave Lynchburg. . . . . 276

-

CHAPTER XXIV.

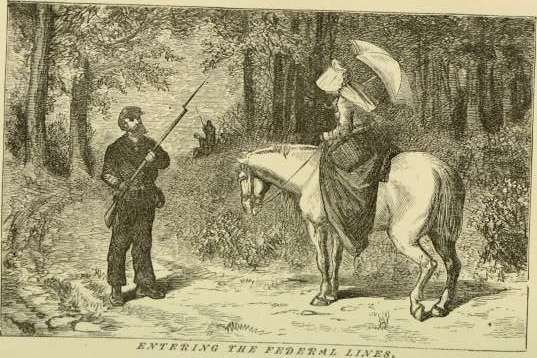

RUNNING THROUGH THE FEDERAL LINES.

At Charlotte, North Carolina. — Arrival of Longstreet's Corps, on its

Way to re-enforce Bragg's Army. — I obtain Permission for Myself and

other Officers to go on the Train Southward. — I arrive in Atlanta,

Georgia, and receive Letters from several Members of my Family. — I

learn for the first Time that my Brother is in the Confederate Army. —

I receive Information of the Officer to whom I am engaged to be

married, and whom I have not seen since the Battle of Shiloh. — I make an

Attempt to reach Him, but am unable to do so. — Failing in an Endeavor

to become attached to General Armstrong's Command, I determine

to undertake an Expedition through the Lines. — Finding a Supply

of female Garments in a deserted Farm-house, I attire Myself as a

Woman. — My Uniform hid in an Ash-barrel. — An Invasion of the

Dairy. — I start for the Federal Lines. . . . . 288

-

CHAPTER XXV.

THE MILITARY SECRET SERVICE. — RETURN FROM A SPYING EXPEDITION.

The Duties of Spies. — The Necessity for their Employment. — The Status of

Spies, and the extraordinary Perils they Run. — Some Remarks about the

Secret Service, and the Necessity for its Improvement. — I reach the Federal

Lines, and obtain a Pass to go North from General Rosecrans. — On my

Travels in search of Information. — Arrival at Martinsburg, and am put in the

Room of a Federal Officer. — A Disturbance in the Night. — "Who is that

Woman?" — I make an advantageous Acquaintance. — A polite

Quartermaster. — All about a pretended dead Brother. — How Secret Service

Agents go about their Work. — A Visit to my pretended Brother's Grave, and

what I gained by It. — I succeed in giving one of Mosby's Pickets an important

Bit of Information. — The polite Attention of Federal Officers. — I return to Chatanooga, and

resume my Confederate Uniform. — A perilous Attempt to reach the

Confederate Lines. — What a Drink of Whiskey can do. — I become lame in

my wounded Foot, and am sent to Atlanta for medical Treatment. . . . . 298

-

CHAPTER XXVI.

IN THE HOSPITAL.

The Kind of People an Army is made up Of. — Gentlemen and

Blackguards. — The Demoralization of Warfare. — How I managed to keep out

of Difficulties. — The Value of a fighting Reputation. — A Quarrel with a

drunken General. — I threaten to shoot Him. — My Illness, and the kind

Attentions received from Friends. — I am admitted to the Empire

Hospital. — The Irksomeness of a Sick-bed. — I learn that my Lover is in the

same Hospital, and resolve to see him as soon as I am Convalescent. . . . . 310

-

CHAPTER XXVII.

A STRANGE STORY OF TRUE LOVE.

Sick-bed Fancies. — Reflections on my military Career. — I almost resolve to

abandon the Garb of a Soldier. — Difficulties in the Way of achieving

Greatness. — Warfare as a laborious Business. — The Favors of Fortune

sparingly Bestowed. — Prospective Meeting with my Lover. — Anxiety to

know what he would think of the Course I had been pursuing in figuring in the

Army as a Man. — A strange Courtship. — More like a Chapter of Romance

than a grave Reality. — My Recollections of an old Spanish Story, read in my

Childhood, that in some Respects reminds me of my own Experiences[.] — The

Story

of Estela. — How the Desires of a Pair of Lovers were opposed by stern

Parents. — An Elopement Planned. — The Abduction of Estela through the

Instrumentality of a Rival. — She is carried off by Moorish Pirates, and

sold as a Slave. — Her Escape from Slavery, and how she entered the Army

of the

Emperor disguised as a Man. — Estela saves the Emperor's Life, and is

promoted to a high Office[.] — Her Meeting with her Lover, and her Endeavors

to make him confess his Faith in her Honor. — The Appointment of Estela as

Governor of her native City. — The Trial of her Lover on the Charge of

having murdered her. — Happy Ending of the Story. — I am inspired, by my

Recollections of the Story of Estela, to hear from the Lips of my Lover his

Opinion of me before I reveal myself to him. — Impatient Waiting for the

Hour of Meeting. . . . . 317

-

CHAPTER XXVIII.

AGAIN A WIFE AND AGAIN A WIDOW.

Convalescence. — I pay a Visit to my Lover. — A Friendly Feeling. — A

Surprise in Store for him. — I ask him about his Matrimonial Prospects, and

endeavor to ascertain the State of his Affections towards me. — An affecting

Scene. — The Captain receives a Letter from his Lady-love. — "She has come!

She has come!" — The Captain prepares for a Meeting with his Sweetheart. —

A Question of Likeness. — A puzzling Situation. —

I reveal my Identity. — Astonishment and Joy of my Lover.

— Preparations for our Wedding. — A very quiet Affair Proposed. — The

Wedding. — A short Honeymoon. — Departure of my Husband for the

Front. — My Apprehensions for his Health. — My Apprehensions justified in

the News of his Death in a Federal Hospital in Chatanooga. — Once more a

Widow. . . . . 326

-

CHAPTER XXIX.

IN THE CONFEDERATE SECRET SERVICE.

Altered Circumstances. — The Result of two Years and a half Experience in

Warfare. — The Difference between the Emotions of a raw Recruit and a

Veteran. — Difficulties in the Way of deciding what Course it was best to

pursue for the Future. — I resolve to go to Richmond in Search of active

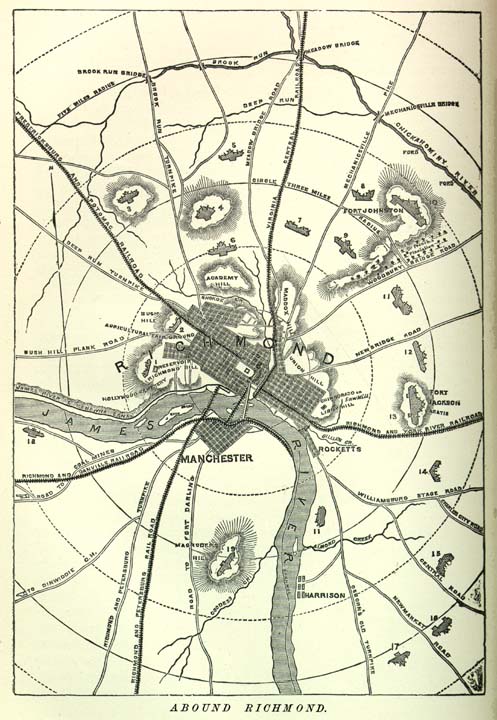

Employment of some Kind. — The Military Situation in the Autumn of

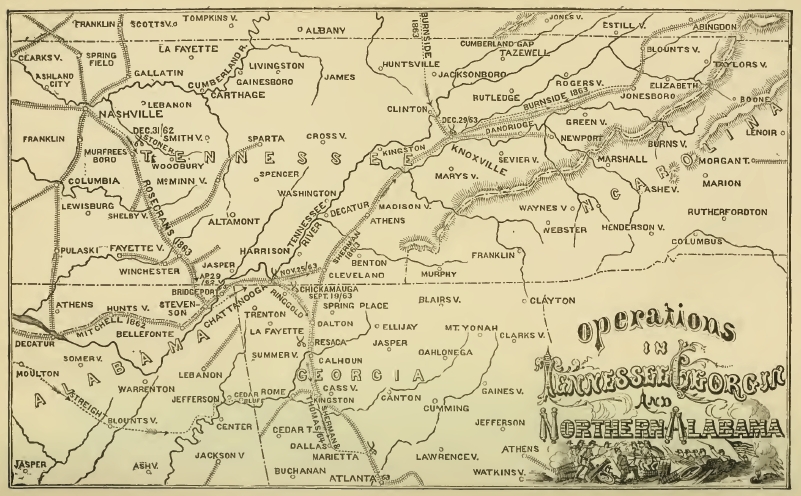

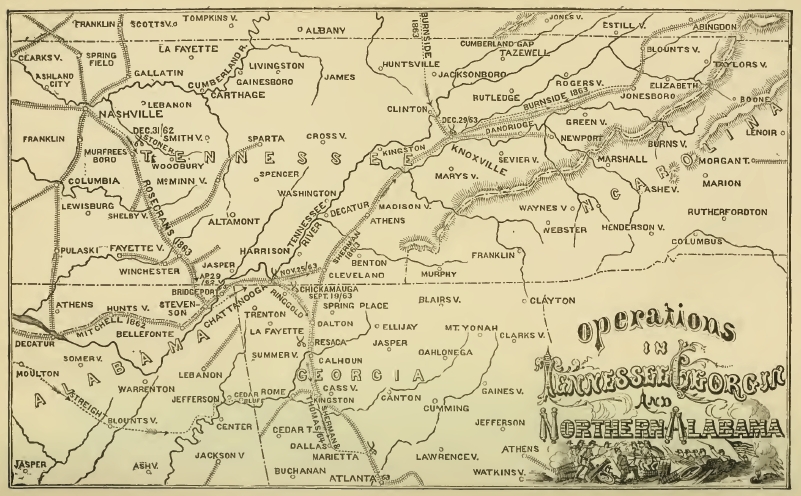

1863. — Concentration of the Armies at Richmond and Chatanooga. —

Richmond safe from Capture. — The Results of the Battle of

Chickamauga. — Rosecrans penned up in Chatanooga by Bragg. — The Pinch of

the Fight Approaching. — Hopes of foreign Intervention. — An apparently

encouraging Condition of Affairs. — I go to Richmond, and have Interviews

with President Davis and General Winder. — I am furnished by the Latter with a

Letter of Recommendation, and start on a grand Tour through the

Confederacy. — Arrival at Mobile, and Meeting with old Army Friends. . . . . 339

-

CHAPTER XXX.

ON DUTY AS A SPY.

I receive a mysterious Note, requesting me to meet the Writer. — I go to the

appointed Place, and find an Officer of the Secret Service Corps, who wants

me to go through the Lines with Despatches. — I accept the

Commission, and the next Day go to Meridian for the Purpose of completing

my Arrangement and receiving my Instructions. — A Visit to General Ferguson's

Headquarters. — Final Instructions from the General, who presents me with a

Pistol. — I start for the Federal Lines, and ride all Night and

all the next Day. — A rough and toilsome Journey. — I spend the Night in a

Negro's Cabin. — Off again at three o'clock in the Morning with an old Negro

Man for a Guide. — We reach the Neighborhood of the Federal Pickets, and I

send my Guide back. — I bury my Pistol in a Church. — I am halted by a

Picket-guard, and am taken to Moscow. — A Cross-examination by the Colonel in

Command. — Satisfactory Result for Myself. — On the Train for

Memphis. — Insulting Remarks from the Soldiers. — A Major interferes for my

Protection. — Off for General Washburn's Headquarters. . . . . 348

-

CHAPTER XXXI.

SENDING INFORMATION TO THE CONFEDERATES FROM MEMPHIS.

My Friend, the Lieutenant, concludes that he will make himself better

acquainted with me. — Indiscreet Confidences. — Some of the Traits of

Human Nature. — The Kind of Secrets Women can Keep. — Women better

than Men for certain Kinds of Secret Service Duty. — The Lieutenant wants to

know all about me. — I suspect that he has Matrimonial Inclinations. — He is

anxious to discover whether I have any wealthy Relations. — I am induced to

think that I can make him useful in obtaining Information with regard to the

Federal Movements. — The Lieutenant expresses his Opinion about the

War. — Arrival at Memphis. — Visit to the Provost Marshal's Office. —

General Washburn too ill to see me. — I enclose him the bogus Despatch I have

for him, with an explanatory Note. — The Lieutenant escorts me to the

Hardwick House, and I request him to call in the Morning. — Procuring a Change

of Dress through One of the Servants, I slip out, and have an Interview with my

Confederate, and give him the Despatch for General Forrest.

— On returning to the Hotel, I meet the Lieutenant on the Street, but manage

to pass him without being observed. — Satisfactory Accomplishment of my

Errand. . . . . 362

-

CHAPTER XXXII.

FORREST'S GREAT RAID. — GOING NORTH ON A MISSION OF MERCY.

A Friend in Need is a Friend Indeed. — The Lieutenant aids me in procuring a

new Wardrobe. — I succeed in finding out all I want to know about the

Number and the Disposition of the Federal Troops on the Line of the

Memphis and Charleston Railroad. — A Movement made in accordance with

the bogus Despatch which I had brought to General Washburn. — Forrest makes

his Raid, and I pretend to be alarmed lest the Rebels should capture me. — The

Lieutenant continues his Attentions, and Something occurs to induce me to

change my Plans. — I have an Interview with an Officer of my Brother's

Command, and learn that he is a Prisoner. — I resolve to go to him, and leave

North on a Pass furnished by General Washburn. — At Louisville I have

an Interview with a mysterious secret Agent of the Confederacy, who supplies

me with Funds. — On reaching Columbus, Ohio, I obtain a Permit to see my

Brother. — Through the Agency of Governor Brough my Brother is released,

and we go East together, — he to New York, I to Washington. . . . . 373

-

CHAPTER XXXIII.

SECRET SERVICE DUTY AT THE NORTH.

New Scenes and new Associations. — My first Visit to the North. — The Wealth

and Prosperity of the North contrasted with the Poverty and Desolation of

the South. — Much of the northern Prosperity fictitious. — The anti-war

Party and its Strength. — How some of the People of the

North made Money during the War. — "Loyal" Blockade-runners and

Smugglers. — Confederate Spies and Emissaries in the Government

Offices. — The Opposition to the Draft. — The bounty-jumping Frauds. — My

Connection with them. — Operations of the Confederate Secret Service

Agents. — Other Ways of fighting the Enemy than by Battles in the Field. — I

arrange a Plan of Operations, and place myself in communication with the

Confederate Authorities at Richmond, and also with Federal Officials at

Washington and Elsewhere. — I abandon Fighting for Strategy. . . . . 383

-

CHAPTER XXXIV.

PLAYING A DOUBLE GAME.

Studying the Situation. — I renew my Acquaintance with old Friends of

The Federal Army. — Half-formed Plans. — I obtain an Introduction to

Colonel Lafayette C. Baker, Chief of the United States Secret Service

Corps. — Colonel Baker and General Winder of the Confederate Secret

Service compared. — Baker a good Detective Officer, but far inferior to

Winder as the Head of a Secret Service Department. — I solicit Employment

from Baker as a Detective, and am indorsed by my Friend General

A. — Baker gives a rather indefinite Answer to my Application. — I go

to New York, and fall in with Confederate Secret Service Agents, who

employ me to assist them in various Schemes. — Learning the Ropes. —

I send Intelligence of my Movements to Richmond, and am enrolled as

a Confederate Agent. — I have several Interviews with Baker, and succeed

in gaining his Confidence. — Baker's Surprise and Disgust at various

Times at his Plans leaking Out. — The Secret of the Leakage Revealed. . .

. . 392

-

CHAPTER XXXV.

VISIT TO RICHMOND AND CANADA.

An Attack on the Rear of the Enemy in Contemplation. — The Difficulties

in the Way of its Execution. — What it was expected to Accomplish. —

The Federals to be placed between two Fires. — I have an Interview

with Colonel Baker, and propose a Trip to Richmond. — He assents,

and furnishes me with Passes and Means to make the Journey. — I run

through the Lines, and reach Richmond in Safety. — I return by a

roundabout Route, laden with Despatches, Letters, Commercial Orders,

Money Drafts, and other valuable Documents. — I am delayed in

Baltimore,

and fall short of Money. — The Difficulties I had in getting my

Purse filled. — Sickness. — I visit Lewes, Delaware, and deliver

Instructions to a Blockade-runner. — On reaching New York I learn that a

Detective is after me. — I start for Canada, and meeting the

Detective in the

Cars, strike up an Acquaintance with him. — He shows me a Photograph,

supposed

to be of myself, and tells me what his Plans are. — The Detective

baffled, and

my safe Arrival in Canada. — Hearty Welcome by the Confederates

there. — I

transact my Business, and prepare to return. . . . . 403

-

CHAPTER XXXVI.

ARRANGEMENTS FOR A WESTERN TRIP.

I return to Washington for the Purpose of reporting to Colonel Baker. —

Apprehensions with regard to the Kind of Reception I am likely to have

from him. — The Colonel amiable, and apparently unsuspicious. — I

give him an Account of my Richmond Trip, and receive his Congratulations.

— General A. calls on me, and he, Baker, and I go to the Theatre. —

A Supper at the Grand Hotel. — Baker calls on me the next

Morning, and proposes that I shall visit the Military Prisons at Johnson's

Island and elsewhere, for the Purpose of discovering whether the

Confederate Prisoners have any Intentions of Escaping. — I accept the

Commission, and start for the West. — Reflections on the Military and

Political Situations. . . . . 420

-

CHAPTER XXXVII.

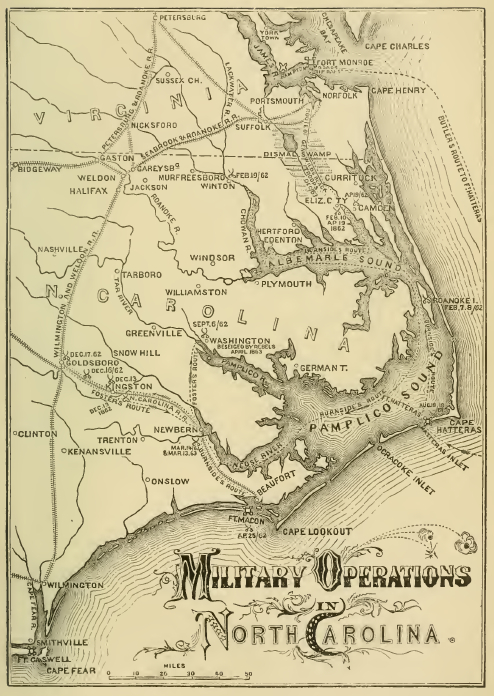

JOHNSON'S ISLAND. — PREPARATIONS FOR AN ATTACK ON THE FEDERAL REAR.

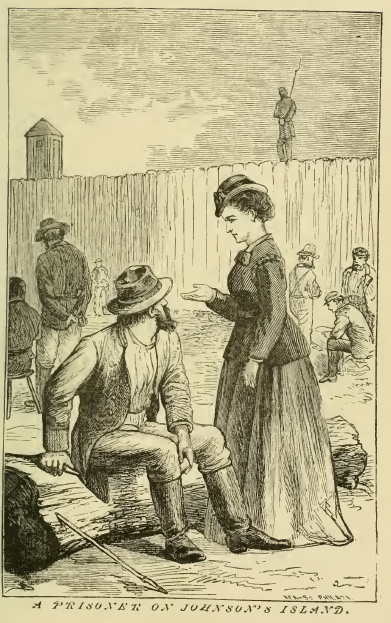

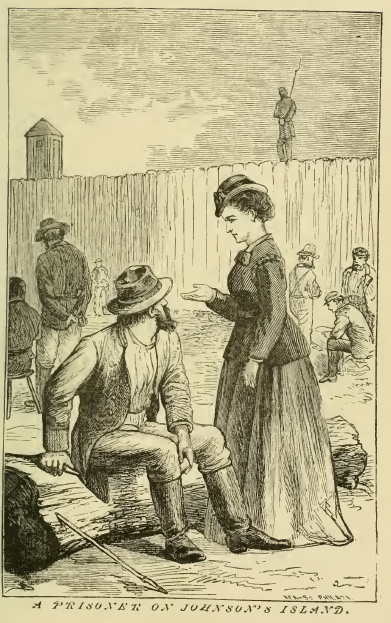

On the Way to Sandusky. — I am introduced to a Federal Lieutenant on the

Cars, who is conducting Confederate Prisoners to Johnson's Island. — He

permits me to converse with the Prisoners, and I distribute some Money

among them. — Arrival at Sandusky. — First View of Johnson's Island. — I

visit the Island, and, on the strength of Colonel Baker's Letter, am

permitted

to go into the Enclosure and converse with the Prisoners. — I have a Talk

with

a young Confederate Officer, and give him Money and Despatches, and

explain what

is to be done for the Liberation of himself and his

Companions. — Returning to Sandusky, I send Telegraphic Despatches to the

Agents in Detroit, Buffalo, and Indianapolis. — How the grand Raid was

to have been made. — Its Failure

through the Treason or Cowardice of one Man. . . . . 433

-

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

IN THE INDIANAPOLIS ARSENAL. — FAILURE OF THE PROJECTED RAID.

I deliver Despatches to Agents in Indianapolis. — Waiting for Orders. —

I obtain Access to the Prison Camp, and confer with a Confederate Officer

confined there. — I apply to Governor Morton for Employment, and

am sent by him to the Arsenal. — I obtain a Situation in the Arsenal,

and am set to work packing Cartridges. — I form a Project for blowing

up the Arsenal. — Reasons for its Abandonment. — I receive a suspicious

Number of Letters. — How I obtained my Money Package from

the Express Office. — I go to St. Louis, and endeavor to obtain Employment

at the Planters' House, for the Purpose of enabling me to gain

Information from the Federal Officers lodging there. — Failing in this,

I strike up an Acquaintance with a Chambermaid, and by Means of her

Pass Key gain Access to several Rooms. — I gain some Information

from Despatches which I find, and am very nearly detected by a Bell

Boy. — I go to Hannibal to deliver a Despatch relating to the Indians. —

Hearing of the Failure Of the Johnson's Island Raid, I return East, and

send in my Resignation to Colonel Baker. . . . . 444

-

CHAPTER XXXIX.

BLOCKADE-RUNNING.

Making Preparations for going into Business as a Blockade-runner. — The Trade

in Contraband Goods by Northern Manufacturers and Merchants. — Profits

versus Patriotism. — The secret History of the War yet to be told. — This

Narrative a Contribution to it. — Some dark Transactions of which I was

Cognizant. — Purchasing Goods for the Southern Market, and shipping them on

Board of a Schooner in the North River. — How such Transactions were

managed. — The Schooner having sailed, I go to Havana by Steamer. —

On reaching Havana I meet some old Friends. — The Condition of the

blockade-running Business during the last Year of the War. — My Acquaintances

in Havana think that the Prospects of the Confederacy are rather gloomy. —

I visit Barbadoes,

and afterwards St. Thomas. — While at St. Thomas the Confederate Cruiser

Florida comes in, coals, and gets to Sea again, despite the Federal Fleet

watching her. . . . . 454

-

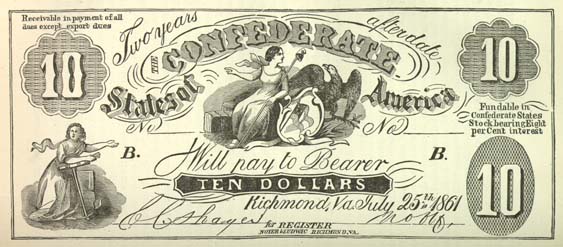

CHAPTER XL.

AN ATTACK ON THE FEDERAL TREASURY.

The Bounty-jumping and Substitute-brokerage Business. — Rascalities in

high Life and low Life. — Bounty-jumpers and Substitute-brokers not

the worst Rogues of the Period. — High Officials of the Government

implicated in Swindles. — Baker's Raid on the Treasury Ring, and the

Charges of Conspiracy brought against him by Members of Congress

and others. — A Committee of Congress exonerates the guilty Parties,

and blames Baker for exposing them. — What I know about these

Transactions. — Money needed to carry on the Confederate Operations

at the North. — Federal Officials countenancing the Issue of counterfeit

Confederate Bonds and Notes. — I go to Washington for the Purpose of

getting in with the Treasury Ring. — A rebel Clerk introduces me to a

high Official, who, on condition of sharing in the Profits, introduces

me to the Printing Bureau of the Treasury. — The Trade with England

in bogus Federal and Confederate Securities. — Making Johnny Bull

pay some of the Expenses of the War. . . . . 464

-

CHAPTER XLI.

COUNTERFEITING AND BOGUS BOND SPECULATIONS.

Introduction to an Official of the Printing Bureau of the Treasury Department.

— The Chief of the Treasury Ring. — I am referred by him to

another Person in the Bureau, who arranges for a private Interview

with me under a Cedar Tree in the Smithsonian Grounds. — The Influence

of certain Rascals in the Treasury Department with Secretary Chase and other

high Officials. — The Scandals about the Women Employees in the Department. —

Baker's Investigation baffled. — The Case of Dr. Gwynn. — The Conference

under the Cedar Tree. — A grand Scheme for speculating with Government Funds.

— I obtain Possession of an Electrotype Fac-Simile of a One-Hundred Dollar

Compound Interest Plate. — A Package of Money left for me under the Cedar

Tree. — Speculation in bogus Confederate and Federal Notes and Bonds. — How

the Thing was Managed. — Increase of illicit Speculation as the War

Progressed. — Bankers, Brokers, and other Men of High Reputation implicated in

it. — Counterfeiting, to a practically unlimited Extent, carried on with the

Aid of Electrotypes furnished from the Treasury Department. — Advantages taken

by the Confederate Agent of the general Demoralization. . . . . 476

-

CHAPTER XLII.

BOUNTY-JUMPING.

The Bounty-jumping and Substitute-brokerage Frauds, and their Origin.

— New York the Headquarters of the Bounty and Substitute-Brokers. —

Prominent Military Officers and Civilians implicated in the Frauds. — How

newly-enlisted Men managed to escape from Governor's Island. —

Castle Garden the great Resort of Substitute-brokers. — How the poor

Foreigners were entrapped by lying Promises made to them. — How these

Frauds could have been prevented by an impartial Conscription Law

impartially administered. — Colonel Baker arrives in New York for the

Purpose of commencing an Investigation. — He asks me to assist him, which I

consent to do, after warning my Associates. — How Baker went to

Work. — Striking up an Acquaintance with Jim Fisk. — Fisk gives me Money

for a Charitable Object, and Railroad Passes for poor Soldiers. — An Oil

Stock Speculation. . . . . 488

-

CHAPTER XLIII.

THE SURRENDER OF LEE.

Another Expedition to the West. — Hiring out as a House Servant. — A

Termagant Mistress. — Obtaining a Situation in a Copperhead Family.

— Introduction to Confederate Sympathizers. — A Contribution to the

Fund for the Relief of Confederate Prisoners. — I go to Canada, and from there

to New York, with Orders for various Confederate Agents. — Sherman's March

through the Carolinas. — I am induced to go to London on a financial

Mission. — Unsatisfactory News received, and I hasten Home. — The News of

Lee's Surrender brought on board the Steamer by the Pilot. — Excitement in

Wall Street. — A Settlement with my Partner, and the last of my secret

Banking. . . . . 499

-

CHAPTER XLIV.

THE ASSASSINATION OF PRESIDENT LINCOLN, AND END OF THE WAR.

Another Western Trip. — Delivering Despatches to Quantrell's Courier.

— A Stoppage at Columbus, Ohio. — News of the Assassination of President

Lincoln. — Return to New York. — Derangement of Plans caused by the

Assassination. — I again go West. — Mr. Lincoln's Body lying in State

at Columbus. — Return to Washington, and Interview with Baker. — I meet a

Confederate Officer, and get him to take a Message for me

to the South. — An aged Admirer. — Colonel Baker proposes that I shall start

on an Expedition in Search of myself. — A Letter from my Brother, and a

Request to meet him in New York. — A Determination to visit Europe. — I

accept Baker's Commission, and start for New York. . . . . 508

-

CHAPTER XLV.

A TOUR THROUGH EUROPE.

Off for Europe. — Seasickness. — An over-attentive

Doctor. — Advantages of

knowing more Languages than one. — A young Spaniard in

Love. — Arrival in

London. — Paris and its Sights. — Rheims and the Champagne

Country. —

Frankfort on the Main. — A beautiful Country, and a thriving

People. — A Visit to Poland. — Return to Paris, and Meeting

with old Confederates. — Friends who knew me, and who did not know

me. — Finding out what my old Army Associates thought of

Me. — Back to

London. — A Visit to Hyde Park, and a Sight of Queen

Victoria. — Manchester

and its Mills. — Homeward Bound. — Return to New York, and

Separation from

my Brother and his Family. . . . . 519

-

CHAPTER XLVI.

SOUTH AMERICAN EXPEDITION.

A Southern Tour. — Visit to Baltimore and Washington. — The

Desolations

of War as visible in Richmond, Columbia, and Charlotte. — A Race with

a

Federal Officer at Charleston. — Meeting with old Friends at

Atlanta. — A

Surprise for one of them. — Travelling over my old Campaigning

Ground. — The

Forlorn Appearance of Things in New Orleans. — Emigration

Projects. — I make

some Investigation into them, and decide to go to South America for the

Purpose

of looking at the Country, and reporting to my Friends. — The

Venezuelan

Expedition and its Projector. — I suspect that it is a mere

Speculation, but

conclude to accompany it. — My third Marriage. — I endeavor to

persuade my

Husband to seek a Home in the Far West, but on his Refusal, sail with him

for

Venezuela. — Forty-nine Persons packed in a small Schooner, with no

Conveniences, and with scanty Provisions. — A horrible

Voyage. — Sighting

the Mouth of the River Orinoco. . . . . 531

-

CHAPTER XLVII.

VENEZUELA.

Taking a Pilot on board. — A perplexing Predicament. — Beautiful

Scenery

along the Orinoco. — Negro Officials. — Disgust of some of the

Emigrants. —

Frightened Natives. — Arrival at the City of Bolivar. — The

United States

Consul ashamed of the Expedition. — Death of my

Husband. — Another

Expedition makes its Appearance. — Sufferings of the

Emigrants. — I write a

Letter to my Friends in New Orleans, warning them not to come to

Venezuela. —

Rival Lovers. — I conclude that I have had enough of Matrimony, and

encourage

neither of them. — A Trip by Sea to La Guyra and Caraccas. — I

prepare to

leave. — What I learned in Venezuela. — The Resources of the

Country. . . . . 542

-

CHAPTER XLVIII.

DEMERARA, TRINIDAD, BARBADOES, AND ST. LUCIA

From Venezuela to Demerara. — The Hotels of Georgetown,

Demerara. — The

United States Consul at Georgetown. — A Visit to a Coffee

Plantation. — A

Cooly murders his Wife. — Excitement in the Streets of

Georgetown. — The

Products of Demerara. — Fort Spain, Trinidad. — A very dirty

Town. —

Bridgetown, Barbadoes. — Having a good Time among old

Friends. — A Drive to

Speightstown. — St. Lucia. — The old

Homestead. — Reminiscences of

Childhood. — The Past, the Present, and the Future. — The Family

Burying-ground. . . . . 553

-

CHAPTER XLIX.

ST. THOMAS AND CUBA.

St. Thomas. — A cordial Welcome. — A Reception at the

Hotel. — Points of

Interest at St. Thomas. — The Escape of the Florida. — Santiago

de Cuba. —

Hospitalities. — Havana. — Visits from my

Relatives. — Courtesies from

Spanish Officials and others. — I take part in a Procession,

attired as a Spanish Officer. — General Mansana taken sick. — A

Steamer in

the Harbor, with Emigrants from the United States on board, bound for

Para. —

I endeavor to persuade them to Return. — Death of General

Mansana. — I start

for New York. . . . . 562

-

CHAPTER L.

ACROSS THE CONTINENT.

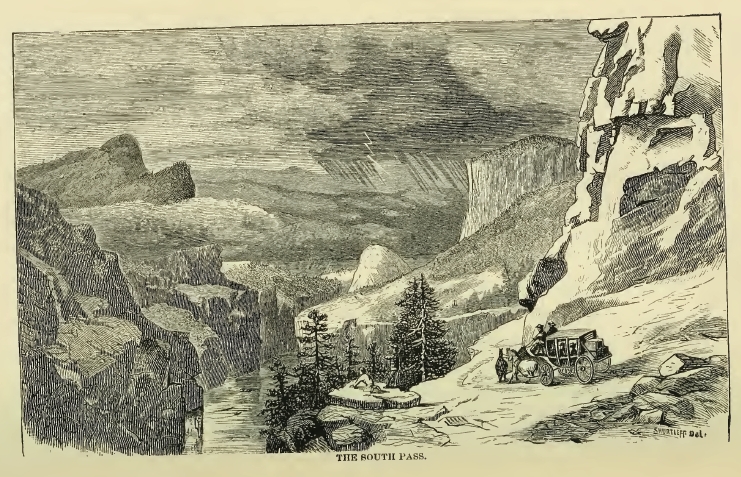

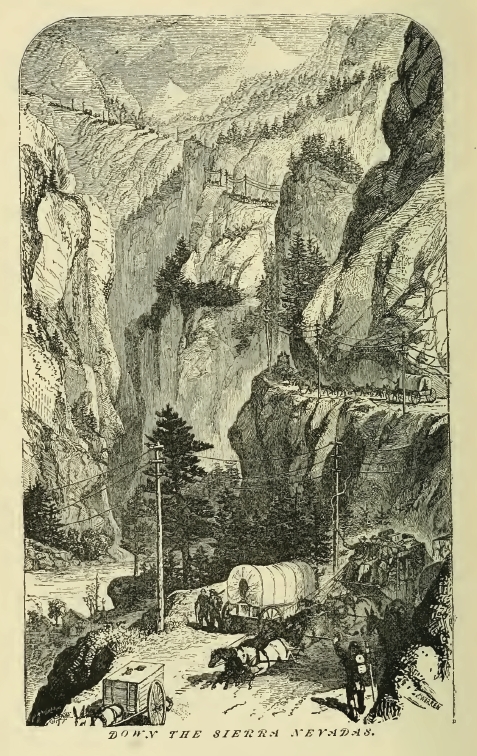

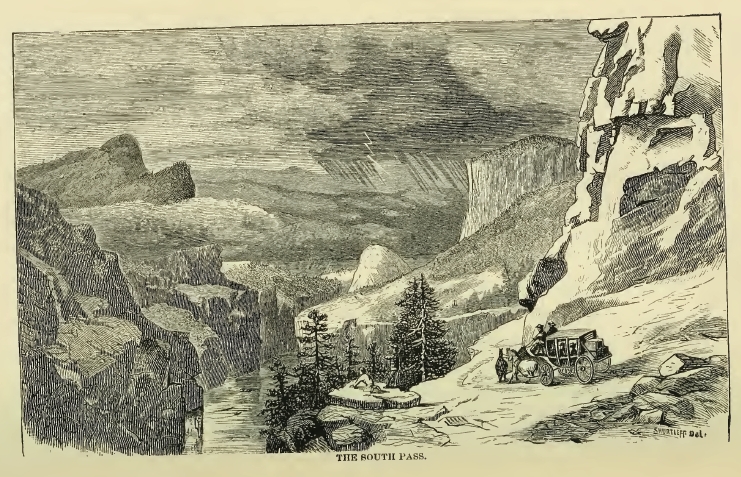

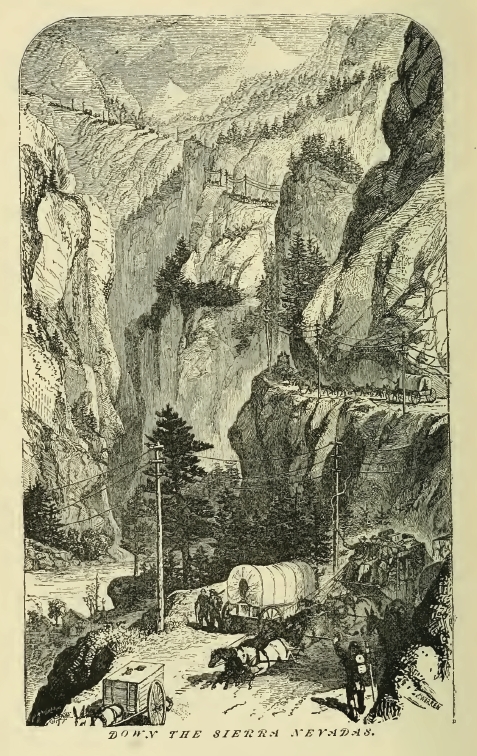

Across the Continent in search of a Fortune. — Omaha. — A Meeting

with the

veteran General Harney. — Governor C. asks me to introduce him to the

General. — The Backwoodsman and the veteran Soldier. — The

General induces

me to tell the Story of my Career, and gives me some good

Advice. — Off for a

long Stage-coach Ride. — Rough Fellow-Travellers. — An unmannerly

Army

Officer taught Politeness. — Julesburg. — An undesirable Place

for a

permanent Residence. — An atrocious Murder. — More unpleasant

travelling

Companions. — Cheyenne. — A Frontier Hotel. — Lack of even

decent

Accommodations. — An undesirable Bedfellow. — A Visit to

Laporte. — Again

on the Road. — A Water-Spout in Echo Canon. — The Coach caught in

a

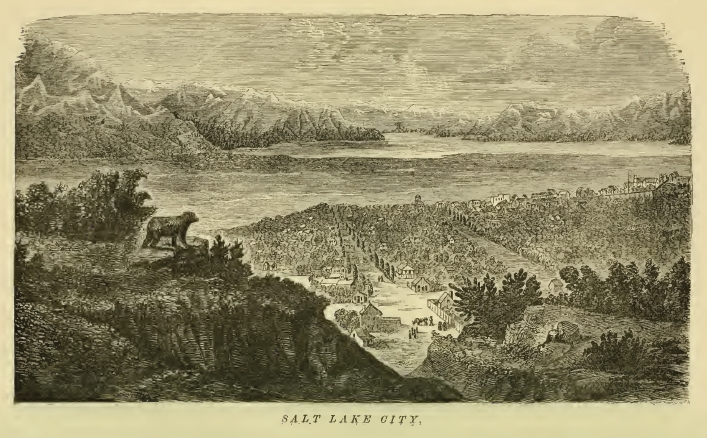

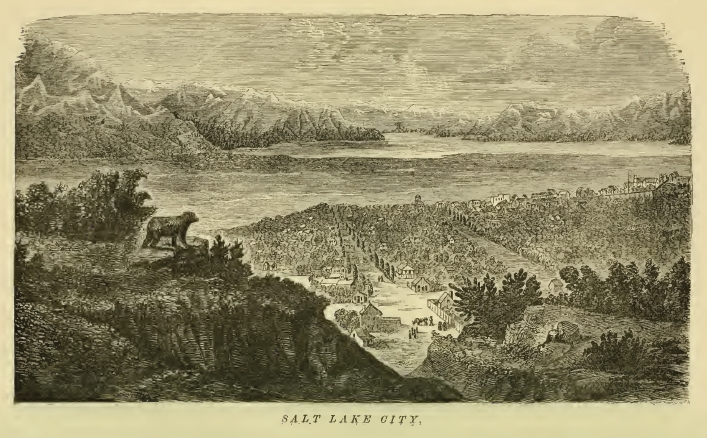

Quicksand. — Mormon Hospitalities. — Salt Lake

City. — Arrival at the City

of Austin, Nevada. . . . . 570

-

CHAPTER LI.

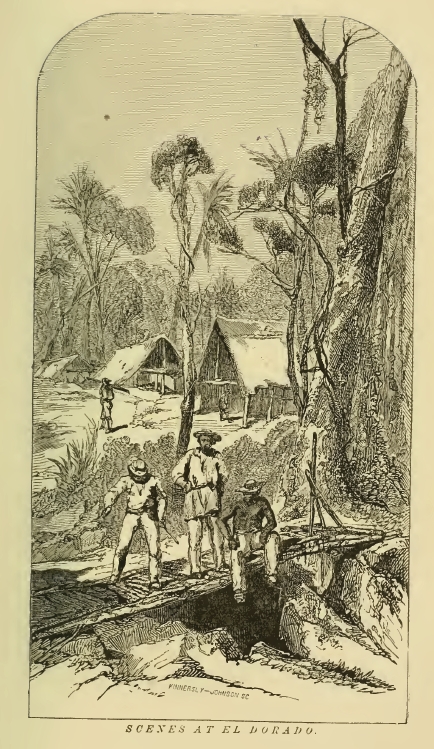

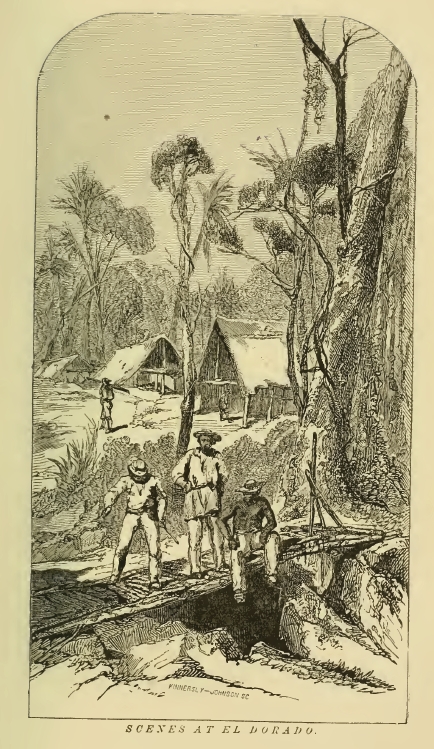

MINING IN UTAH AND NEVADA. — THE MORMONS AND THEIR COUNTRY.

Noisy Neighbors. — A Nevada Desperado. — The Aristocracy of

Austin. — My

Marriage. — Speculation in Mines and Mining Stock. — Removal to

Sacramento

Valley, California. — Off for the Gold Regions again. — A

characteristic

Fraud. — "Salting" a Mine. — The Wellington

District. — A Description of

the Country, and its Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral Products. — A

Residence in

Salt Lake City. — Acquaintance with prominent Mormons, and Inquiries

into the

Nature of their Belief. — Mormon Principles and Practices. — Salt

Lake City

and its Surroundings. — The Mineral Wealth of Utah. — Preparing

to Return to

the East. . . . . 584

-

CHAPTER LII.

COLORADO, NEW MEXICO, AND TEXAS. — CONCLUSION.

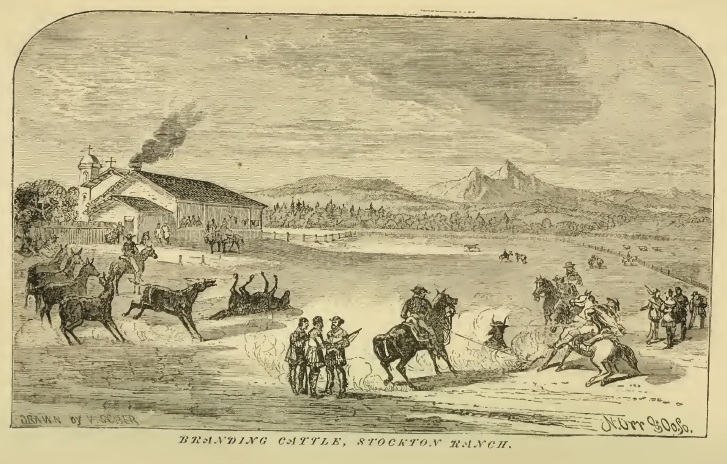

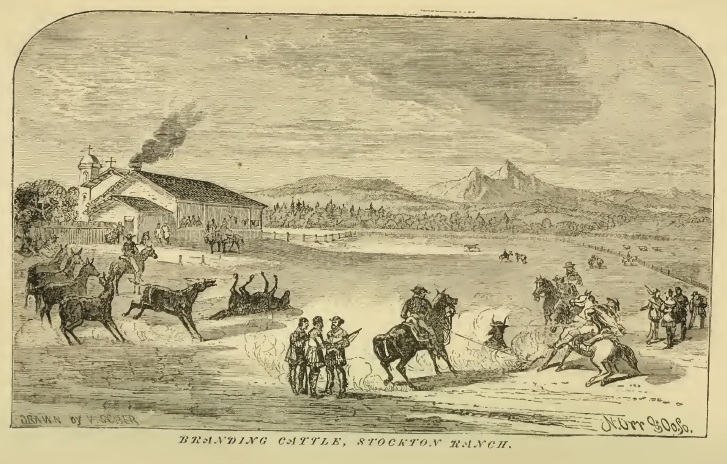

Denver. — Pueblo. — Trinidad. — Stockton's Ranche. — A

Headquarters for

Desperadoes. — Cattle Stealing. — A private

Graveyard. — Maxwell's

Ranche. — Dry Cimmaron. — Fort Union. — Santa Fe. — The

oldest City in

New Mexico. — A Wagon Journey down the Valley of the Rio

Grande. — Evidences

of Ancient Civilization. — Fort McRae and the Hot Spring. — Mowry

City. —

The Gold Mining Region of New Mexico and Arizona. — El Paso. — A

thriving

Town. — A Stage Ride through Western Texas. — Fort

Bliss. — Fort Quitman

and Eagle Spring. — The Leon Holes. — Fort Stockton. — The

Rio Pecos. —

A fine Country. — Approaching Civilization. — The End of the

Story. . . . . 597

THE WOMAN IN BATTLE.

CHAPTER I.

CHILDHOOD.

The Woman in Battle. — Heroines of History. — Joan

of Arc. — A Desire to emulate Her. — The Opportunity that was

offered. — Breaking out of the War between the North and

the South. — Determination to take part in the Contest. — A noble

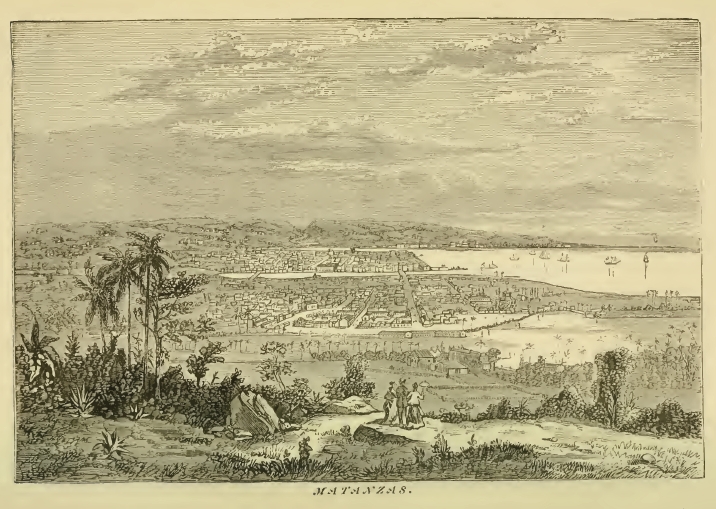

Ancestry. — The Velazquez Family. — My Birth at

Havana. — Removal of my Family to Mexico. — The War

between The United States and Mexico. — Loss of my Father's

Estates. — Return of the Family to Cuba. — My early

Education. — At School in New Orleans. — Castles in the

Air. — Romantic Aspirations. — Trying to be a Man. — Midnight

Promenades before the Mirror in Male Attire.

HE

woman in battle is an infrequent figure on the pages of history, and

yet, what would not history lose were the glorious records of the

heroines, — the great-souled women, who have stood in the front rank

where

the battle was hottest and the fray most deadly, — to be obliterated?

When women have rushed to the battle-field they have invariably

distinguished themselves; and their courage, their enthusiasm, and their

devotion to the cause espoused, have excited the brave among the men

around them to do and to dare to the utmost, and have shamed the

cowards into believing that it was worth while to peril life itself in a noble

cause, and that

honor to a soldier ought to be more valuable than even life. The

records of the women who have taken up arms in the cause of

home and country; who have braved the scandals of the camp;

who have hazarded reputation, — reputation dearer than

life, — and who have stood in the imminent

deadly breach, defying the enemy, if not so imposing in

numbers as those in which the deeds of male warriors are

recited, are glorious nevertheless; and if steadfast courage,

true-hearted loyalty, and fiery enthusiasm go for anything, women

have nothing to blush for in the martial deeds of those of their

sex who have stood upon the battle-field.

HE

woman in battle is an infrequent figure on the pages of history, and

yet, what would not history lose were the glorious records of the

heroines, — the great-souled women, who have stood in the front rank

where

the battle was hottest and the fray most deadly, — to be obliterated?

When women have rushed to the battle-field they have invariably

distinguished themselves; and their courage, their enthusiasm, and their

devotion to the cause espoused, have excited the brave among the men

around them to do and to dare to the utmost, and have shamed the

cowards into believing that it was worth while to peril life itself in a noble

cause, and that

honor to a soldier ought to be more valuable than even life. The

records of the women who have taken up arms in the cause of

home and country; who have braved the scandals of the camp;

who have hazarded reputation, — reputation dearer than

life, — and who have stood in the imminent

deadly breach, defying the enemy, if not so imposing in

numbers as those in which the deeds of male warriors are

recited, are glorious nevertheless; and if steadfast courage,

true-hearted loyalty, and fiery enthusiasm go for anything, women

have nothing to blush for in the martial deeds of those of their

sex who have stood upon the battle-field.

Far back in the early days of the Hebrew commonwealth

Deborah rallied the despairing warriors of Israel, and led them

to victory. Semiramis, the Queen of the Assyrians, commanded

her armies in person. Tomyris, the Scythian queen, after the

defeat of the army under the command of her son, Spargopises,

took the field in person, and outgeneralling the Persian king,

Cyrus, routed his vastly outnumbering forces with great

slaughter, the king himself being among the slain. Boadicea, the

British queen, resisted the Roman legions to the last, and fought

the invaders with fury when not a man could be found to lead the

islanders to battle. Bona Lombardi, an Italian peasant girl, fought

in male attire by the side of her noble husband, Brunaro, on more

than one hotly contested field; and on two occasions, when he had

been taken prisoner and placed in close confinement, she

effected his release by her skill and valor.

The Nun-Lieutenant.

Catalina de Eranso, the Monja

Alferez, or the nun-lieutenant,

who was born in the city of Sebastian, Spain, in 1585, was

one of the most remarkable of the heroines who have

distinguished themselves by playing the masculine rôle, and

venturing into positions of deadly peril. This woman,

becoming disgusted with the monotony of convent life, made

her escape, and in male garb joined one of the numerous

expeditions then fitting out for the New World. Her intelligence

and undaunted valor soon attracted the notice of her superior

officers, and she was rapidly promoted. Participating in a

number of hard-fought battles, she won the reputation of being

an unusually skilful and daring soldier, and would have

achieved both fame and fortune, were it not that her fiery temper

embroiled her

in frequent quarrels with her associates. One of her many

disagreements resulted in a duel, in which she had the

misfortune to kill her antagonist, and, to escape the vengeance

of his friends, she was compelled to fly. After traversing a

large portion of the New World, and encountering innumerable

perils, she returned to Europe, where she found that the

trumpet of fame was already heralding her name, and that

there was the greatest curiosity to see her. Travelling through

Spain and Italy, she had numerous exceedingly romantic

adventures; and while in the last named country she managed to obtain an

interview with Pope Urban VIII., who was so pleased with

her appearance and her conversation that he granted her

permission to wear male attire during the balance of her life.

Within the past hundred years more than one heroine has

stamped her name indelibly upon the role of fame. All

Amercans know how brave Molly Pitcher, at the battle of

Monmouth, busied herself in carrying water to the parched and

wearied soldiers, and how, when her husband was shot down

at his gun, instead of woman fashion, sorrowing for him with

unavailing tears, she sprang to take his place, and through the

long, hot summer's day fought the foreign emissaries who were

seeking to overthrow the liberties of her country, until, with

decimated ranks they fled, defeated from the field.

At the seige of Saragossa, in 1808, when Palafox, and the

men under his command, despaired of being able to resist the

French, Agostino, "the maid of Saragossa," appeared upon the

scene, and with guerra al cuchillo — "war to the knife" — as

her battle-cry, she inspired the general and his soldiers to fight

to the last in resisting the French invaders, and by her words

and deeds became the leading spirit in one of the most heroic

defences of history.

Appolonia Jagiello.

Nearer our own time Appolonia Jagiello fought valiantly for

the liberation of Poland and Hungary. She had kingly blood in

her veins, and her heart burned within her at the

wrongs which her native country, Poland, suffered at the hands

of her oppressors. When the insurrection at Cracow took

place, in 1846, she assumed male attire, and went into the

thickest of the fight. The insurrection was a failure, although

it might not have been had the men who began it been as

stout-hearted and as enthusiastic in a great cause as Appolonia

Jagiello. In 1848 she participated in another outbreak at

Cracow, and distinguished herself as one of the most valorous

of the combatants. After the failure of this attempt at

rebellion she went to Vienna, where she took part in an

engagement in the faubourg Widen. Her object in visiting the

Austrian capital, however, was chiefly to ascertain the exact

character of the struggle which was in progress, in order to

carry information to the Hungarians. After numerous perilous

adventures she joined the Hungarian forces, and fought

at the battle of Enerzey, in which the Austrians were defeated,

and on account of the valor she displayed was promoted

to the rank of lieutenant. After this she joined an

expedition under General Klapka, which assaulted an took

the city of Raab. When the Hungarians were finally defeated

and there was no longer any hope that either Hungary or

Poland would gain their independence, Mademoiselle Jagiello

came to the United States, in 1848, with other refugees, and for

a number of years resided in the city of Washington, respected

and beloved by all who knew her. No braver soldier than this