Alexander Walker.

Jackson and New Orleans.

Table of Contents

- Jackson’s First Entry into New Orleans

- Lafitte, “the Pirate”

- Lafitte, the Patriot

- Jackson clears his flanks

- The British review and embarkation

- Battle of Lake Borgne

- The British landing and bivouac

- The alarm — the rally — the march

- Battle of the twenty-third of December, 1814

- Sir Edward Packenham

- A demonstration and a debate

- The British bring up their big guns

- Battle of the batteries

- The notable warriors and revolutionists

- Preparation for the final conflict

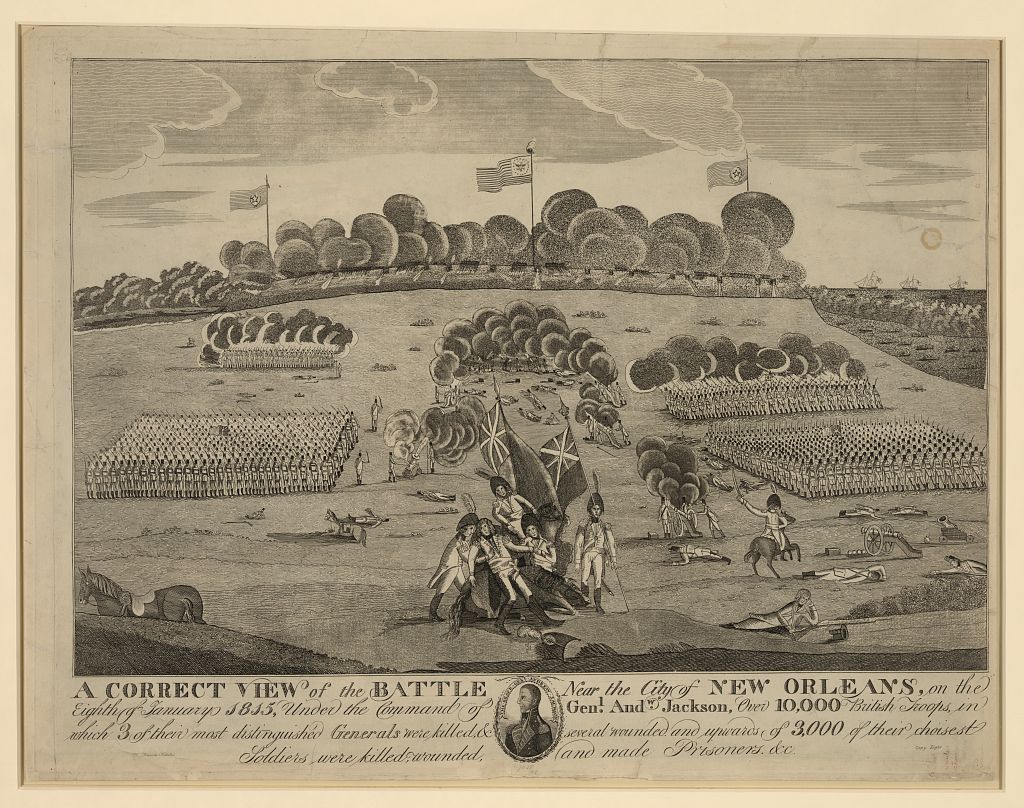

- The Battle of New Orleans — the victory

- The Battle of New Orleans — the disaster

- Closing Incidents

- The finale

Introduction

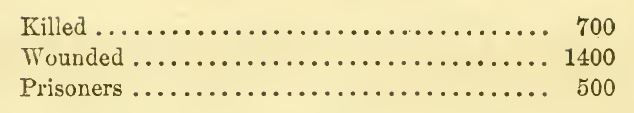

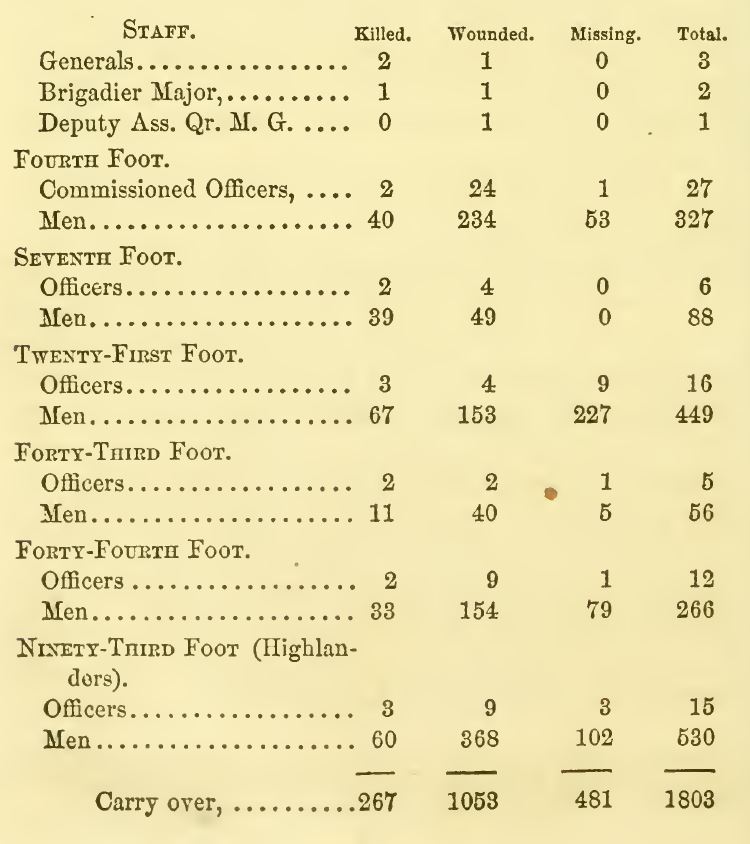

THERE is no campaign in modern military history, which, for Its extent, was more complete in all its parts, and more brilliant in its results, than that conducted by Andrew Jackson in 1814-15, in the defence of New Orleans. In the brief period of twenty-six days, a town of less than eighteen thousand inhabitants, including all sexes and ages, without forts — natural or artificial defences — exposed to approach and attack on all sides, by land and water — with an en masse, and illy armed and accoutred — was not only successfully defended against a veteran army of ten thousand of the best soldiers in the world, but was made forever glorious by the most brilliant victory, which has been achieved since the invention of gunpowder. The peculiarities of this victory are the astonishing and unprecedented disparity of loss between the combatants, and the marvellous proofs of steadiness, of skill and rapidity in the use of fire-arms, displayed by the American militia. The splendor of the closing victory has obscured many features of this campaign, which contributed largely to the final result, and, as valuable lessons and glorious illustrations of the valor of our citizen soldiers, and of the genius of the great Chief and Hero — whose lofty soul was the fountain of inspiration, from which all engaged in that defence, drew courage, confidence, and patriotic resolution — ought not to be forgotten or hastily glanced over. These sketches have been written with the hope of preventing such unpatriotic lapses of memory in the present generation.

It is believed that the campaign of 1814-15 has not received full justice, in the narratives, which have been published, the numerous merits of which have been marred by serious errors. By comparing these various versions and by constant consultations with those, who played prominent parts on both sides in this drama, it is believed that the following account, which does not aspire to the dignity of history, and is divested of cumbrous details and of military technicalities, is as faithful and exact as it is practicable to render a narrative of this description.

There are in most of the histories of this campaign, errors of a serious character, which ought to be corrected before the evidence thereof has perished or disappeared. Personal and political feeling and prejudice, which, in so many histories, have warped and tinged the facts of this epoch, have been studiously excluded from the mind of the writer of these sketches. His sole desire has been to do full justice to American valor and patriotism, and to present truthful and vivid pictures of that memorable defence, and of the conduct of the great Chief, who, springing from the people, a frontier warrior, without science, art or experience in military affairs, was enabled through the smiles of Providence, by his stout heart, his sagacious intellect, and ardent patriotism, to repel, punish, and nearly destroy one of the best appointed armies ever sent forth by the greatest Power of the earth. Ought such deeds to be permitted to fade from the memories of a patriotic people? Is it not a reproach to the present generation, that modern events of far less splendor and importance should occupy their minds, to the exclusion of memories like these we have invoked? It is demonstratable that in every aspect in which it may be viewed, the defence of Sevastopol in 1854-55 by the Russians, against the allied armies of Great Britain and France, is far less remarkable as a military exploit, than the defence of New Orleans in 1814-15; whilst the operations of the Allies have displayed less resolution and energy than were evinced by the veteran army of Packenham. The occurrence of the former operations presents a favorable occasion for the reproduction of the facts of the last-named campaign, in which will be found some remarkable coincidences, with the events of the Crimean Expedition. Thus, it will be perceived that the failure of the one, and the disastrous delays of the other expedition, may be traced to the same cause, namely the lack of promptitude and decision in the commander of the attacking party. It is conceded on all sides that if the Allied Army had advanced upon, and stormed Sevastopol immediately after the victory at Alma, it could have entered and captured the town. So, it is equally clear that General Keane could have marched into New Orleans after the battle of the 23rd December 1814. The strength of earth-works against the most powerful batteries, which was so strongly shown in Jackson’s defence, was again illustrated on the southern side of Sevastopol, against the same British Engineering-officer who constructed the redoubts which Jackson’s Artillery destroyed in three hoars on the plains of Chalmette, on the first of January 1814; this unfortunate officer is Sir John Burgoyne, Inspector of Fortifications in the British army. The lesson at New Orleans should have taught another wholesome truth to the projectors of the Crimean Expedition — that of the great peril and difficulty of all attempts to capture a town, the communication of which, with the interior, is left open and unobstructed. In this respect the positions of New Orleans and Sevastopol were identical. Finally these two campaigns have demonstrated this other valuable and encouraging truth; that in the most remote and exposed points of a united Nation, we often find the most brilliant proofs of patriotism, courage, and devotion.

A. W.

JACKSON AND NEW ORLEANS

I

JACKSON’S FIRST ENTRY INTO NEW ORLEANS.

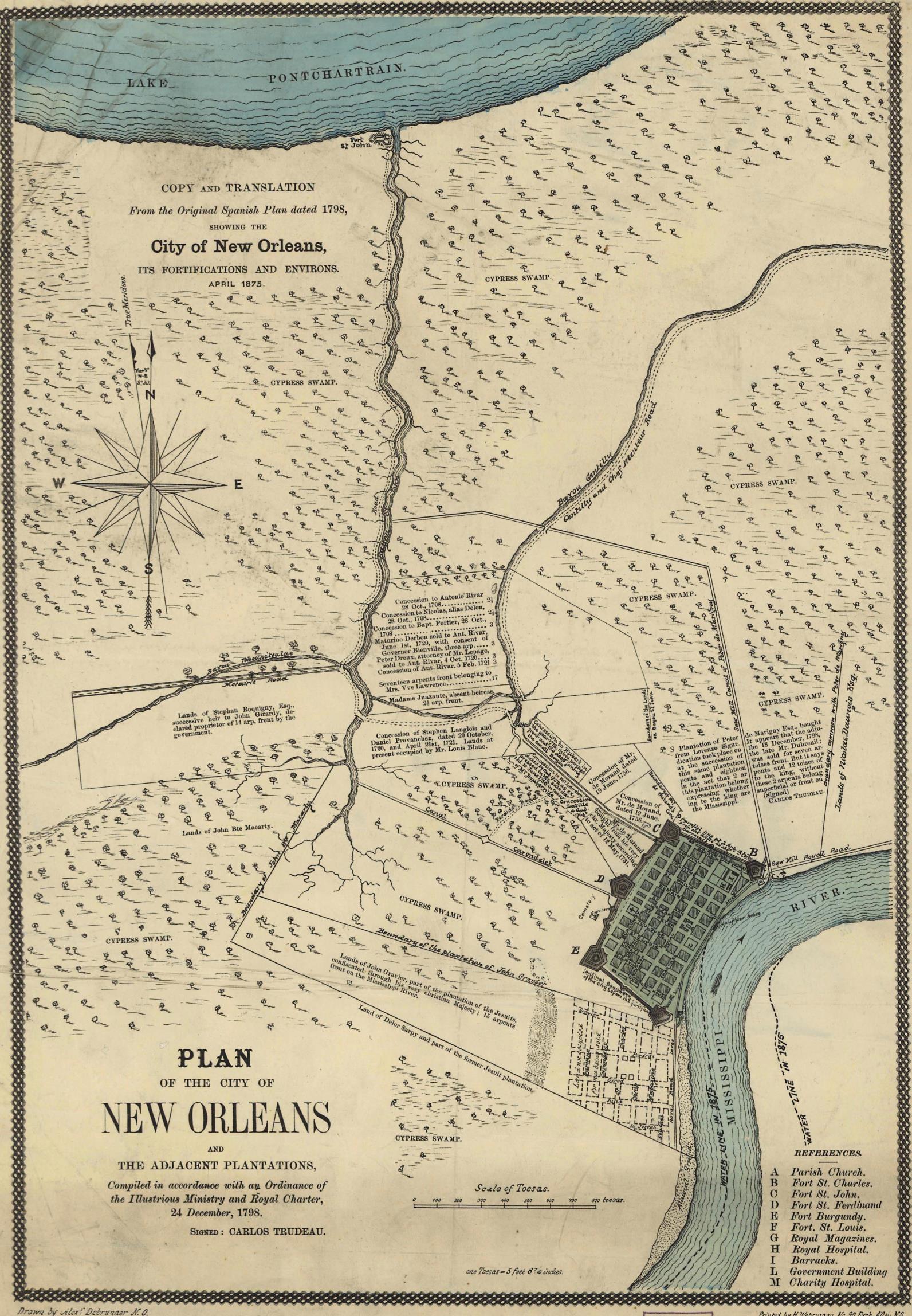

IN the rear of the city of New Orleans, and about a mile from its centre, there is a small, narrow, winding, and still stream, called, in the South, a Bayou, which communicates with Lake Pontchartrain. This bayou, no doubt, once flowed from the Mississippi, but in the progress of time and in the process of accretion, its source has been thrown some distance from the river, and now starting in the swamp above the city, it steals through an indentation of the delta, winds along the base of the Metairie Kidge (a curious protrusion from the level plain in which New Orleans is built), and, approaching the suburbs of the city, turns abruptly to the east, and then, with sluggish current, meanders towards the lake. A canal, commenced by that great benefactor of New Orleans, Baron Carondelet, the labor of which was performed by slaves belonging to the citizens, who were levied upon for that purpose, which was completed in 1796, connects the bayou with the city, and thus supplies the latter with an excellent water communication with the lake, through which, in the early days of its history, much of the commerce of New Orleans was conducted. Biloxi, the Bay of Saint Louis and Pass Christian were then nourishing settlements, where the French established their first colonies, before the mouth of the Mississippi had been discovered, and where most of the shipping engaged in the foreign and coastwise trade came to anchor, and transshipping their cargoes into smaller crafts, sent them to New Orleans through the Bayou Saint John (the name of the stream we have described), and the canal Carondelet. There, at the head of navigation on the bayou, and about half a mile from the mouth of the canal, is the old settlement of Saint John, which existed when the present site of New Orleans was an unbroken swamp, the favorite retreat of alligators and other reptiles. But time has wrought a striking change in the character and aspect of these localities. The seashore settlements no longer resorted to for purposes of trade, are now only known as places of summer sojourn and recreation. Thither flock the jaded denizens of the city, to refresh their wearied frames, to invigorate broken constitutions, to relieve their minds of the oppression of all business cares, and to inhale an atmosphere of luxurious and exhilarating salubrity.

Alas! this ancient canal and bayou followed the fortunes of the ancient population of New Orleans, and, in the march of Anglo-American enterprise, lost its value and importance as a vehicle of commerce, when a new canal of larger dimensions was constructed in another part of the city, where the all-conquering invaders from Northern climes had “pitched their tents.”

The fame and history of this old bayou and canal had become classical, as relics of a past age and generation. They were intimately associated with the early glories of New Orleans, and were, therefore, held in warm veneration by the old inhabitants. Several attempts have been made to restore the fortunes of the old bayou, and render it what it appears to be so admirably designed for, an additional means of transit for the great and rapidly increasing commerce between New Orleans and the growing towns and settlements on the Lake and Gulf shore; but thus far they have not proved successful.

The Bayou St. John empties into Lake Pontchartrain at a distance of seven miles from the city. Here, at its mouth, may be seen the remains, in an excellent state of preservation, of an old Spanish fort, which was built many years ago by one of the Spanish Governors, as a protection of this important point; for, by glancing at the map of New Orleans and its vicinity, it will be seen that a maritime power could find no easier approach to the city than through the Bayou St. John. This fort was built, as the Spaniards built all their fortifications in this State, where stone could not be procured, of small brick, imported from Europe, cemented with a much more adhesive and permanent material than is now used for building, and with walls of great thickness and solidity. The foundation and walls of the fort still remain, interesting vestiges of the old Spanish dominion. On the mound and within the walls, stands a comfortable hotel, where, in the summer season, may be obtained healthful cheer, generous liquors, and a pleasant view of the placid and beautiful lake, over whose gentle bosom the sweet south wind comes with just power enough to raise a gentle ripple on its mirror-like surface, bringing joy and relief to the wearied townsman, and debilitated invalid. What a different scene did this fort present forty years ago! Then there were large cannon looking frowningly through those embrasures, which are now tilled up with dirt and rubbish, and around them clustered glittering bayonets and tierce-looking men, full of military ardor and determination. There, too, was much of the reality, if not of “the pomp and circumstance” of war. High above the fort, from the summit of a lofty staff, floated not the showy banner of Old Spain, with its glittering and mysterious emblazonry, but that simplest and most beautiful of all national standards, the Stars and Stripes of the Republic of the United States.

From the Fort St. John to the city, the distance is six or seven miles. Along the bayou, which twists its sinuous course like a huge dark green serpent, through the swamp, lies a good road, hardened by a pavement of shells, taken from the bottom of the lake. Hereon, city Jehus now exercise their fast nags, and lovely ladies take their evening airings. But at the time our narrative commences, it was a very bad road, being low, muddy, and broken. The ride, which now occupies some twenty minutes very delightfully, was then a wearisome two hours’ journey.

It was along this road, early on the morning of the 2d December, 1814, that a party of gentlemen rode at a brisk trot, from the lake towards the city. The mist, which during the night broods over the swamp, had not cleared off. The air was chilly, damp and uncomfortable. The travellers, however, were evidently hardy men, accustomed to exposure and intent upon purposes too absorbing to leave any consciousness of external discomforts. Though devoid of all military, display and even of the ordinary equipments of soldiers, the bearing and appearance of these men betokened their connection with the profession of arms. The chief of the party, which was composed of five or six persons, was a tall, gaunt man, of very erect carriage, with a countenance full of stern decision and fearless energy, but furrowed with care and anxiety. His complexion was sallow and unhealthy; his hair was iron grey, and his body thin and emaciated, like that of one who had just recovered from a lingering and painful sickness. But the fierce glare of his bright and hawk-like grey eye, betrayed a soul and spirit which triumphed over all the infirmities of the body. His dress was simple, and nearly threadbare. A small leather cap protected his head, and a short Spanish blue cloak his body, whilst his feet and legs were encased in high dragoon boots, long igorant of polish or blacking, which reached to the knees. In age, he appeared to have passed about forty-five winters, — the season for which his stern and hardy nature seemed peculiarly adapted.

The others of the party were younger men, wdiose spirits and movements were more elastic and careless, and who relieved the weariness of the journey with many a jovial story.

Arriving at the high ground near the junction of the Canal Carondelet with the Bayou St. John, where a bridge spanned the bayou, and quite a village had grown up, the travellers halted before an old Spanish villa, and, throwing their bridles to some grinning negro boys at the gates, dismounted and walked into the house. On entering the gallery, they were received in a very cordial and courteous manner, by J. Kilty Smith, Esq., then a leading New-Orleans merchant of enterprise and public spirit, aud who, a few months ago, still survived, one of the most venerable of that small band of the early American settlers, in the great commercial emporium of the South, who, out-living several generations, still linger in green old age, amid the scenes of their youthful struggles, and survey, with proud satisfaction, the greatness to which that city has grown, whose tender infancy they witnessed and helped to nurse and rear into a sturdy and robust maturity. On the bayou, in an agreeable suburban retreat, Mr. Smith had established himself. Here he dispensed a liberal hospitality, and lived in such a style as was regarded in those economical days, and by the more frugal Spanish and French populations, as quite extravagant and luxurious.

Ushering them into the marble-paved hall of his old Spanish villa, Mr. Smith soon made his guests comfortable. It was evident that they were not unexpected. Soon the company were all seated at the breakfast table, which fairly groaned with the abundance of generous viands, prepared in that style of incomparable cookery, for which the Creoles of Louisiana are so renowned. Of this rich and savory food, the younger guests partook quite heartily; but the elder and leader of the party was more careful and abstemious, confining himself to some boiled hominy, whose whiteness rivaled that of the damask table-cloth. In the midst of the breakfast, and whilst the company were engaged in discussing the news of the day, a servant whispered to the host, that he was wanted in the ante-room. Excusing himself to his guests, Mr. Smith retired to the ante-room, and there found himself in the presence of an indignant and excited Creole lady, a neighbor, who had kindly consented to superintend the preparations in Mr. Smith’s bachelor-establishment, for the reception of some distinguished strangers, and who, in that behalf, had imposed upon herself a severe responsibility and labor.

“Ah! Mr. Smith,” exclaimed the deceived lady, in a half-reproachful, half-indignant style, “how could you play such a trick upon me? You asked me to get your house in order to receive a great General. I did so, I worked myself almost to death to make your house comme il faut, and prepared a splendid dejeuner, and now I find that all my labor is thrown away upon an ugly, old Kaintuck-nat-boatman, instead of your grand General, with plumes, epaulettes, long sword, and moustache.”

It was in vain that Mr. Smith strove to remove the delusion from the mind of the irate lady, and convince her that that plainly-dressed, jaundiced, hard-featured, unshorn man, in the old blue coat, and bullet buttons, was that famous warrior, Andrew Jackson.

It was, indeed, Andrew Jackson, who had come, fresh from the glories and fatigues of his brilliant Indian campaigns, in this unostentatious manner, to the city which he had been sent to protect from one of the most formidable perils that ever threatened a community. Cheerfully and happily had he embraced this awful responsibility. He had come to defend a defenceless city, situated in the most remote section of the Union, — a city which had neither fleets nor forts, means nor men — a city, whose population were comparative strangers to that of the other States, who sprung from a different national stock, and spoke a different language from that of the overwhelming majority of their countrymen — a language entirely unknown to the General — to defend it, too, against a power then victorious over the conqueror of the world, at whose feet the mighty Napoleon lay a prostrate victim and chained captive.

After partaking of their breakfast, the General, taking out his watch, reminded his companions of the necessity of their early entrance into the city. In a few minutes, carriages were procured, and the whole party rode towards the city, by the old bayou road. The General was accompanied by Major Hughes, commander of the Fort St. John, by Major Butler, and Captain Eeid, his Secretary, who afterwards became one of his biographers, Major Chotard, and other officers of the staff. The cavalcade proceeded to the elegant residence of Daniel Clark, the first representative of Louisiana, in the Congress of the United States, a gentleman of Irish extraction, who had acquired great influence, popularity, and wealth, in the city, and died shortly after the commencement of the war of 1812. Here Jackson and his aids were met by a committee of the State and city authorities, and of the people, at the head of whom was the Governor of the State, who, in earnest but rather rhetorical terms, welcomed the General to the city, and proffered him every aid of the authorities and the people, to enable him to justify the title which they were already conferring upon him of “Savior of New Orleans.” His Excellency, W. C. C. Claiborne, the first American Governor of Louisiana, a Virginian, of good address, and fluent elocution, then in the bloom of life, was supported by the leading civil and military characters of the city. There, in the group was that redoubtable naval hero, Commodore Patterson, a stout, compact, gallant-bearing man, in the neat undress naval uniform. His manner was slightly marked by hauteur, but his movement and expression indicated the energy and boldness of a man of decided action, as well as confident bearing.

Here, too, was the then Mayor of New Orleans, Nicholas Girod, a rotund, affable, pleasant old French gentleman, of easy, polite manners. There, too, was Edward Livingston, then the leading civil character in the city, — a tall, high-shouldered man, of ungraceful figure and homely countenance, but whose high brow, and large, thoughtful eyes, indicated a profound and powerful intellect. By his side stood his youthful rival at the the bar — an elegant, graceful, and showily-dressed gentleman, whose figure combined the compact dignity and solidity of the soldier, with the ease and grace of the man of fashion and taste, and who, as the sole survivor of those named, retained, in a remarkable degree, the elegance and grace, which characterized his bearing forty years ago, to the day of his very recent and lamented decease. We refer to John R. Grymes, so long the veteran and chief ornament of the New Orleans bar.

Such were the leading personages in the assembly which greeted Jackson’s entrance into New Orleans.

The General replied briefly to the welcome of the Governor. He declared that he had come to protect the city, and he would drive their enemies into the sea, or perish in the effort. He called on all good citizens to rally around him in this emergency, and, ceasing all differences and divisions, to unite with him in the patriotic resolve to save their city from the dishonor and disaster, which a presumptuous enemy threatened to inflict upon it. This address was rendered into French by Mr. Livingston. It produced an electric effect upon all present. Their countenances cleared up. Bright and hopeful were the words and looks of all, who heard the thrilling tones, and caught the heroic glance of the hawk-eyed General. The General and staff then re-entered their carriages. A cavalcade was formed, and proceeded to the building, 106 Royal street — one of the few brick buildings then existing in New Orleans, which now stands but little changed or affected by the lapse of so many years. A flag unfurled from the third story, soon indicated to the population the headquarters of the General who had come so suddenly and quietly to their rescue.

It was true he had come almost alone, without troops, without arms, without money. Nor did he seek to supply these deficiencies with big words, large promises, and loud vauntings. He had a more efficient means of influencing men, a more powerful wand to wield over the minds and hearts of the people. His army and his armor, his strength and means, consisted in the prestige of a name and history, which were then as familiar as household words to all the people of the Valley of the Mississippi, a recurrence to which never failed to enkindle the enthusiasm and excite the pride of the emporium of that valley.

What were these glorious antecedents, that drew so much of popular admiration and confidence to Andrew Jackson, and constitute some of his titles to the renown, which history and all nations assign to him? Let us briefly sketch them.

A wild and desolate place called the Waxhaw Settlement, in a remote district of South Carolina, was the scene of Jackson’s birth and boyhood. Throughout the wide Union it would be difficult to find two more dreary and desert-looking localities, than those, which have been consecrated by the birth of the two most eminent men in the history of America — George Washington and Andrew Jackson.

Jackson was born on the 15th March, 1767. His parents were emigrants from the north of Ireland, but of Scotch descent. They had fled from the persecutions and dissensions of the Old World, in pursuit of peace and happiness in the New. They had been two years in the country when Andrew was born. Like most great men, he was blessed with a mother of uncommon intelligence and vigor of mind. With such an instructress and guardian, his intellect early developed, and his spirit expanded into premature manliness. He needed only the occasion to cast his thoughts and feelings in that heroic mould, which constitutes true greatness. Such opportunity was presented, when in beardless boyhood, he found himself in the very midst of some of the most gloomy scenes of the Revolution of 1776.

In old age, when time and infirmity pressed heavily upon that sanguine and dauntless spirit, and the impressions of youth came out upon the memory with more distinctness, that tottering old man of the Hermitage, with his shrivelled visage and snowy locks, but with eye still unclimmed and piercing as ever, would recall, with frightful accuracy, the horrible scenes of carnage, rapine, and desolation which had made that boyhood, to which most men recur as the bright period of their lives, the gloomiest and saddest epoch in his career.

When a stripling of thirteen, with scarcely the strength to raise a musket, he joined a party of patriots, under the heroic Sumpter, and in the action at Hanging Rock, and in various skirmishes, showed himself to be a boy only in years. His biographers relate several instances in which his ready courage and self-possession saved himself and his companions from death and capture. Even then he was a chief among men, and often assumed the leadership of those who were old enough to be his father.

Captured, at last, by the British, with his brother, he was subjected to the most cruel treatment. When, with characteristic spirit, he refused to perform some menial office for a British officer, he was dastardly cut down by the blow of a sabre, the mark of which was visible ever afterwards. A similar cruelty to his elder brother eventually produced his death. Closely confined in a British prison, Andrew contracted a disease from which he barely escaped with his life, and the effects of which were felt by him for many years after. It was whilst suffering with this disease, and nearly mad with fever and pain, that the young soldier, hearing that a battle was to be fought within view of the prison windows, contrived, by the exertion of all his strength, to climb up the wall to a small port-hole, which commanded a view of the field of strife. It was thus the boy warrior witnessed the first and only pitched battle that ever oc curred under his observation previous to the events we are about to relate..

This was the severely-contested battle of Camden, of which Jackson never failed to retain a clear, distinct, and vivid recollection.

Such were the scenes and sufferings amid which the boyhood of Jackson was passed. It was a severe school, and its effects were quite perceptible in that staunch, unyielding spirit, heroic fortitude, and dauntless resolution, which distinguished him through life.

At the close of the Revolution, Jackson found himself alone in the world, the solitary survivor of a family, which, twenty years before, had left Ireland, with bright hopes of finding in the forests of America, a peaceful, happy home. These circumstances were well calculated to impart to the character of, Jackson, that tinge of melancholy which it wore through life. This feeling of loneliness and keen sense of wrong, in the high-day of youth, broke out into reckless dissipation, which, however, was always redeemed and qualified by a spirit of generosity and chivalry. Conquering this tendency, after expending his patrimony, Jackson, with dauntless heart and iron will, threw himself among the hardy and reckless frontiersmen of Tennessee, and engaged in the perilous practice of law, at a time, and in a country, when and where a good eye, steady nerve, and prowess and courage in personal combat, were more essential to the success of a lawyer, than a knowledge of Coke and Blackstone. Jackson possessed these qualifications of “sharp practice” in an eminent degree. His professional career was a perilous and contentious one. It was better adapted to train and form the warrior than the jurisconsult. The courage, which had been so severely tested in the Revolution, was frequently required to repel the aggressions of those pestilent bullies, who always abound in frontier settlements. Through many dangerous conflicts, the impetuous young Carolinian had to fight his way to a position, which secured him the fear and awe of the disorderly, and the respect and confidence of the hardy settlers. Chivalrous and generous, as determined and ferocious, he was the leader in all enterprises to protect the weak and defenceless. Patriotic and high-toned, be was ever ready to risk his life, to maintain the laws of his country, and enforce justice and lawful authority. Thus the “Sharp Knife” and “Pointed Arrow” of the Indians, was not only a terror to the prowling aborigines, who hung around the settlements, but to the even more ferocious frontiersmen, who straggled from more populous and better organized districts, in the hope of getting beyond the reach of the law and justice, and finding larger and safer fields for their deeds of violence and crime.

Called by the people successively to the civil offices of member of the State Convention, Representative and Senator in Congress, and lastly Supreme Judge of the State, Jackson displayed in all these positions, the same firm spirit and fearless courage, united with great sagacity, and that remarkable courtesy and impressiveness of manner, which excited so much surprise in all persons, who never having before seen him, but familiar with his character and acts, were suddenly brought into his presence.

The life and character, we have thus imperfectly described, clearly indicate the man who would be selected from a million for high military command. And yet, when the war of 1812 broke out, Jackson sought a command in vain. His friends and neighbors understood and appreciated his merits; but those charged with the administration of the Federal Government did not. He only asked for a commission, offering to raise the command himself in thirty days. But he was no intriguer, and his pretensions were ignored. Others were appointed. Disaster after disaster followed. The tragedy of the River Raisin, and the disgraceful failure of the Northern Campaign, filled the whole country, and especially the gallant West, with grief and humiliation. Thousands panted to wipe out these blots from the escutcheon of the Union, with their heart’s blood. But alas! the Government at “Washington was in the hands of “closet warriors,” and political abstractionists, — “ideologists,” in the sense of Napoleon’s characterization of the Republicans of the Abbé Sièyes school. Slighted and rejected by the government, Jackson’s ardor and ambition to serve his country were not extinguished in the chagrin of personal disappointment. He determined to force himself into the service, by raising a large volunteer corps, and so organizing it, that the government would be compelled to recognize its value and muster it into service. The gallant youth of Tennessee quickly rallied to his call. Having soon collected, and organized the requisite force, he at once tendered his services, was accepted by the government, and ordered to proceed to Natchez, a distance of a thousand miles. This march was performed in the depth of winter, through a wild and difficult country, with new and young soldiers.

On his arrival at Natchez, he was destined to receive new mortifications. Suddenly there came an order to disband his troops, and deliver over the public stores, arms, and munitions to an agent of the government. It was a cruel and incomprehensible order. The soldiers were youths, the sons of his neighbors and friends. He was bound to them by stronger and dearer ties, than even those of the chief to his followers. He had pledged his honor to venerable fathers and mothers, to loving wives and sisters, to protect their sons, husbands, and brothers, and lead them back to their homes. Could he obey this revolting command, and then go home and face his old friends and neighbors, who had been thus shamefully deceived? To the soldier and citizen it was a severe alternative, but Jackson did not hesitate. He disregarded the order, and marched his whole command back to Tennessee, through incredible toils and sufferings. He had encountered no enemy, and yet, in that brief campaign, he had displayed higher and nobler traits, than those which shine through the smoke and carnage of battle. He had shown that iron firmness and fortitude, that heroic devotion to his companions, which secured him their lasting gratitude, affection, and confidence, to a degree that rendered his control and influence over them unlimited. When the war-blast sounded, the youth of Tennessee knew in whom to find a chief worthy to lead them.

It was not long before the tocsin rang throughout the West.

Tecumseh, the great Indian Chief, aided by the intrigues of the Spaniards in Florida, and the British, had succeeded in uniting the formidable tribes of Indians in the Mississippi Territory, the Chickasaws, Cherokees, and Creeks, into a powerful league and conspiracy to attack and destroy the most exposed white settlements. The fearful massacre at Fort Mimms was the first demonstration of this design. It fell like a thunder clap from a cloudless sky, on the southwest. A public meeting was held at Nashville, to devise means of arresting and punishing these depreciations. With one voice Jackson was designated by the people as the chief in such enterprise. He accepted the responsible duty, and issued a thrilling appeal to the young men of Tennessee to assemble around his standard. Twenty-five hundred gallant and patriotic men promptly responded to this call.

At the head of this force, though still suffering from a severe wound received in a personal rencontre with the Bentons, Jackson marched rapidly to the southward to the scene of the Indian cruelties. After many delays and difficulties, which would have crushed the energies of almost any other man, Jackson found his blood-thirsty enemy strongly posted at Tallahatchie. His “right arm,” the intrepid Coffee, was thrown forward with a portion of his force, with orders to dislodge the savages. The order was obeyed by Coffee with characteristic energy and promptitude, and after an obstinate conflict, the Indians were entirely routed, with a loss of two hundred killed and eighty-four prisoners. Thence, after issuing requisitions for reinforcements from Tennessee, and after establishing Fort Stockton, Jackson advanced rapidly to the relief of Fort Talladega, where a small force of Americans was surrounded and threatened with instant destruction by more than a thousand fierce warriors. Without resting his men, Jackson pushed forward and fell, with the fury of a tempest, on the surprised savages. The field for some distance around was strewn with the gory bodies of painted warriors. Those who survived the attack and escaped the vengeance of “Sharp Knife,” fled with terror into the deepest recesses of the forest. But these victories, prompt, brilliant, and decisive as they were, did not afford the best tests of Jackson’s military genius. His real trial was yet to come. He did not have to wait long for it.

Jackson had moved so rapidly, and penetrated so far from the base of his operations, that he soon found himself in great stress for provisions and munitions. The promised supplies had failed. There was no evidence in the Southwest, of the existence of a central Government, to aid and further military operations. Thus far, he had maintained himself by his own credit. This resource was exhausted, and now Jackson found himself in the severest strait of the military commander. He had to keep up the spirits and discipline of raw volunteer troops, under the pressure of hunger, want, and sickness. Never did his heroic soul shine out with greater splendor than in this emergency. Cheerfully he shared the bitterest trials and sufferings of his men, selecting the offal of the few cattle left to them for his rations, and allowing his sick men the wholesome meat, dividing his acorns with a fellow-soldier, and giving his blankets, so much needed for his own wasted frame, to some wounded companion. But even this example of heroic fortitude could not prevail over the gnawings of hunger. His men grew clamorous and mutinous. What he would not concede to violence, he cheerfully yielded to reason. He consented to return, until they could meet some supplies. The troops had not proceeded far before they met a large drove of cattle, which had been dispatched to them by some of Jackson’s agents. Oh, with what zest and eagerness did those famished men devour the fresh meat, which the foresight and energy of their General had thus procured for them! But satiety did not restore their spirits, nor invigorate their sense of duty. They still longed for their homes, and persisted in returning. Jackson, ordered them to retrace their steps, and pursue the enemy. They sullenly refused to obey, and, forming the column, were about to resume their march homeward.

Now was the time for action, for resolution, for heroic, sublime courage. Mounting his charger, Jackson rode to the front, and seizing a musket from one of the men, levelled it at the head of the column, and swore, “by the Eternal,” he would shoot the first man who advanced a step. The men were astounded by his audacity and resolution. They knew he was a man of his word. Two thousand impatient, fiery, self-willed frontiersmen, who were little accustomed to restraint or control, thus awed, by one emaciate, weak, broken-armed man! Presently, some of the men, ashamed of their conduct, went over to him and pledged their lives to sustain him. Finally, they yielded to Jackson’s resolution, and agreed to resume their march forward.

New difficulties and sufferings again aroused the spirit of mutiny, and another attempt to depart homeward was made and resisted in the same prompt and decisive manner. At last, Jackson having carried his point, and entirely suppressed the rebellious tendencies of his men, deemed it best to send home the greater part of his troops, and defer further operations for some months. With a few faithful officers and soldiers, he established himself at Fort Stockton.

In January, 1814, having been joined by a force of raw troops, Jackson pushed forward to Emuckfaw, on the Tallapoosa. Near this place he was suddenly attacked with great fury, by a powerful force of Indians, whom he defeated in a close hand-to-hand fight. But his force was too weak to follow up this advantage, so he determined to return to Fort Stockton. It was on his return march, that the enemy surprised Jackson’s rear guard, at Enotchhopo. A momentary panic was created, and the Indians were rapidly breaking into the very centre of the column, when the gallant Armstrong (the late General Robert Armstrong, of the Washington Union), arrested their advance by the effective discharge of a small piece of ordnance, of which he had charge, and by the side of which he fell, desperately wounded. As he lay bleeding on the ground, with crowds of savage enemies pressing around him impatient for his scalp, Armstrong called out, “Some of us must fall, but save the gun!” Carroll, too, a young and intrepid officer, rushed to the relief of Armstrong. He was followed by the famous spy-captain of Duck River, Gordon, who, pressing closely on the left of the enemy, held them in check until Jackson could bring up the main body, which he rapidly effected, and falling upon them, soon put them to flight with great loss, causing their precipitate dispersion through the country in the most destitute and panic-stricken condition.

This affair concluded Jackson’s second campaign. He returned to Fort Stockton, and discharged his men with high testimonials to their good conduct. Soon after, he was joined by a fresh army of nearly three thousand men, with which he determined to advance, and annihilate, at one blow, the hostile tribes. Learning that the Indians had collected in large force, in a spot regarded by them as holy ground, situated in the bend of the Tallapoosa Eiver, called from its shape Tohopeka, or the Horse-shoe, he marched thither.

The Indians were stationed behind a well-constructed breastwork thrown across the neck. Sending Coffee to surround the bend, Jackson opened a cannonade upon their defences in front. This plan not succeeding against so agile and wary a foe, Jackson resolved to storm their works. This was clone with the greatest ardor and heroism by the intrepid Tennesseans. It was a close and bloody fight, of man to man. The Indians, instigated by superstition, as well as by their natural blood-thirstiness, fought with more than usual desperation. They bared their breasts to the gleaming knives, and with their small tomahawks fearlessly threw themselves on the bayonets of their pale-face enemies. It was as terrible, and for the numbers engaged, as destructive a conflict as ever occurred. The breastwork was stormed by the Tennesseans; the charm of invincibility was broken, and the “sacred ground” of the Red Sticks was strewn with eight hundred dead warriors. There were no wounded in those battles. The Red Stick was only conquered in battle when life was extinct.

Thus Jackson redeemed his pledge. The Red Sticks, as a tribe, were annihilated. The few survivors lied to the Spanish settlements in Florida. Some humbly sought for peace and pardon, which Jackson, as generous as brave, cheerfully granted.

This victory for ever destroyed the power of the warlike tribes of the Southwest, and made them ever afterwards, either friends or very timid foes of the whites. It was a brilliant conclusion of Jackson’s Indian campaign. He began now to be known abroad. The people all over the country applauded his heroic bearing, under all circumstances, against starvation, mutiny, desertion and disaffection, as well as against the rifles and tomahawks of his savage enemies. Even the torpid Government at Washington, which had failed to recognize his rights before, now hastened to redeem its error, by appointing him to the Major-Generalship, made vacant by the resignation of William Henry Harrison. Jackson’s first duty, in his new command was, to negotiate a treaty of peace with the Indians, and to guard generally the Southwestern frontier.

It was in the discharge of this duty he approached the Gulf shore, to observe the intrigues of the Spaniards, who were charged with giving aid and comfort to the Indians in their inroads on the white settlements. A much more formidable and important enemy, was also implicated in that infamous alliance with barbarians. The British were virtually in possession of Pensacola. The soul of Jackson fired with the recollection of the cruelties his family had suffered at the hands of his hereditary enemy, in the Revolution of 1776. He longed to avenge those wrongs, not by like cruelties, but by legitimate victories obtained in manly warfare. “We shall soon see, whether he was disappointed in this honorable revenge; whether the military genius, which had been nursed amid the fearful struggles of the War of Independence, which had been trained and disciplined by the trying scenes and perils of frontier life, and in warfare against brave and desperate savages, will not shine even more brilliantly and gloriously in a higher sphere, and on a grander scale of warlike achievement.

II

LAFITTE, “THE PIRATE.”

ABOUT one mile above New Orleans, opposite the flourishing City of Jefferson, and on the right bank of the Mississippi, there is a small canal, now used by fishermen and hunters, which approaches within a few hundred yards of the river’s bank.

The small craft that ply on this canal are taken up on cars, which run into the water by an inclined plane, and are then hauled by mules to the river. Launched upon the rapid current of the Mississippi, these boats are soon borne into the Crescent port of New Orleans. Following this canal, which runs nearly due west for five or six miles, we reach a deep, narrow, and tortuous bayou. Descending this bayou, which for forty miles threads its sluggish course through an impenetrable swamp, we pass into a large lake, girt with sombre forests and gloomy swamps, and resonant with the hoarse croakings of alligators, and the screams of swamp fowls.

From this lake, by a still larger bayou, we pass into another lake, and from that to another, until we reach an island, on which are discernible, at a considerable distance, several elevated knolls, and where a scant vegetation and a few trees maintain a feeble existence. At the lower end of this island, there are some curious aboriginal vestiges, in the shape of high monnds of shells, which are thought to mark the burial of some extinct tribes. This surmise has been confirmed by the discovery of human bones below the surface of these mounds. The elevation formed by the series of mounds, is known as the Temple, from a tradition that the Natchez Indians used to assemble there to offer sacrifices to their chief deity, the “Great Sun.” This lake or bayou finally disembogues into the Gulf of Mexico by two outlets, between which lies the beautiful island of Grand Terre.

This island is a pleasant sea-side resort, having a length of six miles, and an average breadth of a mile and a-half. Towards the sea it presents a fine beach, where those who love “the rapture of the lonely shore,” who delight in the roar and dash of the foaming billows, and in the ecstasy of a bath in the pure, bracing surge, may find abundant means of pleasure and enjoyment.

Grand Terre is now occupied and cultivated by a Creole family, as a sugar plantation, producing annually four or five hundred hogsheads of sugar. At the western extremity of the island stands a large and powerful fortification, which has been quite recently erected by the United States, and named after one of the most distinguished benefactors of Louisiana, Edward Livingston. This fort commands the western entrance or strait leading from the Gulf into the lake or bay of Barataria. Here, safely sheltered, some two or three miles from the gulf, is a snug little harbor, where vessels drawing from d to eight feet water, may ride in safety, out of reach of the fierce storms that so often sweep the Gulf of Mexico.

Here may be found, even now, the foundations of houses, the brickwork of a rude fort, and other evidences of an ancient settlement. This is the spot which has become so famous in the history and romances of the Southwest, as the “Pirate’s Home,” the retreat of the dread Corsair of the Gulf, whom the genius of Byron, and of many succeeding poets and novelists, has consecrated as one who

Linked with one virtue and a thousand crimes.”

Such is poetry — such is romance. But authentic history, by which alone these sketches are guided, dissipates all these fine flights of the poet and romancer.

Jean Laiitte, the so-called Pirate and Corsair, was a blacksmith from Bordeaux, France, who, within the recollection of several old citizens now living in New Orleans, kept his forge at the corner of Bourbon and St. Phillip streets. He had an older brother, Pierre, who was a seafaring character, and had served in the French Navy. Neither were pirates, and Jean knew not enough of the art of navigation to manage a jolly boat. But he was a man of good address and appearance, of considerable shrewdness, of generous and liberal heart, and adventurous spirit.

Shortly after the cession of Louisiana to the United States, a series of events occurred which made the Gulf of Mexico the arena of the most extensive and profitable privateering. First came the war between France and Spain, wdiich afforded the inhabitants of the French islands a good pretence to depredate upon the rich commerce of the Spanish possessions — the most valuable and productive in the New World. The Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea swarmed with privateers, owned and employed by men of all nations, who obtained their commissions (by purchase) from the French authorities at Martinique and Guadalupe. Among these were not a few neat and trim crafts belonging to the staid citizens of New England, who, under the tri-color of France, experienced no scruples in perpetrating acts which, though not condemned by the laws of nations, in their spirit as well as in their practical results, bear a strong resemblance to piracy. The British capture and occupation of Guadalupe and Martinique, in 1806, in which expeditions Col. Ed. Packenham, who will figure conspicuously in these sketches, distinguished himself, and received a severe wound, broke up a favorite retreat of these privateers. Shortly after this, Columbia declared her independence of Spain, and invited to her port of Carthagena, the patriots and adventurers of all nations, to aid her struggle against the mother country. Thither nocked all the privateers and buccaneers of the Gulf. Commissions were promptly given or sold to them, to sail under the Columbian flag, and to prey upon the commerce of poor old Spain, who, invaded and despoiled at home, had neither means nor spirit to defend her distant possessions.

The success of the privateers was brilliant. It is a narrow line, at the best, which divides piracy from privateering, and it is not at all wonderful that the reckless sailors of the Gulf sometimes lost sight of it. The shipping of other countries was, no doubt, frequently mistaken for that of Spain. Rapid fortunes were made in this business. Capitalists embarked their means in equipping vessels for privateering. Of course they were not responsible for the excesses which were committed by those in their employ, nor did they trouble themselves to inquire into all the acts of their agents. Finally, however, some attention was excited by this wholesale system of legalized pillage. The privateers found it necessary to secure some safe harbor, into which they could escape from the ships of war, where they could be sheltered from the northers, and where, too, they could establish a depot for the sale and smuggling of their spoils. It was a sagacious thought which selected the little bay or cove of Grand Terre for this purpose. It was called Barataria, and several huts and store-houses were built there, and cannon planted on the beach. Here rallied the privateers of the Gulf, with their fast-sailing schooners, armed to the teeth and manned by fierce-looking men, who wore sharp cutlasses, and might be taken anywhere for pirates, without offence. They were the desperate men of all nations, embracing as well those who had occupied respectable positions in the naval or merchant service, who were instigated to their present pursuit by the love of gain, as those who had figured in the bloody scenes of the buccaneers of the Spanish Main. Besides its inaccessibility to vessels of war, the Bay of Barataria recommended itself by another important consideration: it was near to the city of New Orleans, the mart of the growing valley of the Mississippi, and from it the lakes and bayous afforded an easy water communication, nearly to the banks of the Mississippi, within a short distance of the city. A regular organization of the privateers was established, officers were chosen, and agents appointed in New Orleans to enlist men, and negotiate the sale of goods.

Among the most active and sagacious of these town agents, was the blacksmith of St. Phillip street, who, following the example of much greater and more pretentious men, abandoned his sledge and anvil, and embarked in the lawless and more adventurous career of smuggling and privateering. Gradually by his success, enterprise, and address, Jean Lafitte obtained such ascendancy over the lawless congregation at Bara-taria, that they elected him their Captain or Commander.

There is a tradition that this choice gave great dissatisfaction to some of the more warlike of the privateers, and particularly to Gambio, a savage, grim Italian, who did not scruple to prefer the title and character of “Pirate,” to the puling, hypocritical one of “Privateer.” But it is said, and the story is verified by an aged Italian, one of the only two survivors of the Baratarians, now resident in Grand Terre, who rejoices in the “nom de guerre” indicative of a ghastly sabre cut across the face, of “Nez Coupé” that Lafitte found it necessary to sustain his authority by some terrible example, and when one of Gambio’s followers resisted his orders, he shot him through the heart before the whole band. Whether this story be true or not, there can be no doubt that in the year 1813, when the association had attained its greatest prosperity, Lafitte held undisputed authority and control over it. He certainly conducted his administration with energy and ability. A large fleet of small vessels rode in the harbor, besides others that were cruising. Their store-houses were filled with valuable goods. Hither resorted merchants and traders from all parts of the country, to purchase goods, which, being cheaply obtained, could be retailed at a large profit. A number of small vessels were employed in transporting goods to New Orleans, through the bayou we have described, just as oysters, fish and game are now brought.

On reaching the head of the bayou, these goods would be taken out of the boats and placed on the backs of mules — to be carried to the river banks — whence they would be ferried across into the city, at night. In the city they had many agents, who disposed of these goods. By this profitable trade, several citizens of New Orleans laid the foundations of their fortunes. But though profitable to individuals, this trade was evidently detrimental to regular and legitimate commerce, as well as to the revenue of the Federal Government. Accordingly, several efforts were made to break up the association, but the activity and influence of their city friends generally enabled them to hush up such designs.

Legal prosecutions were commenced on 7th April, 1813, against Jean and Pierre Lafitte, in the United States District Court for Louisiana, charging them with violating the Revenue and Neutrality Laws of the United States. Nothing is said about piracy — the gravest offence charged, being simply a misdemeanor. Even these charges were not sustained, for, although both the Lafittes, and many others of the Baratarians, were captured by Captain Andrew Holmes, in an expedition down the bayou, about the time of the filing of these informations against them, yet it appears they were released, and the prosecutions never came to trial, the warrants for their arrest being returned “not found.” These abortive proceedings appear to have given encour agement and vigor to the operations of the Baratarians.. Accordingly, we find on the 28th July, 1814, the Grand Jury of New Orleans making the following terrible exposure of the audacity and extent of these unlawful transactions:

“The Grand Jury feel it a duty they owe to society to state that piracy and smuggling, so long established and so systematically pursued by many of the inhabitants of this State, and particularly in this city and vicinity, that the Grand Jury find it difficult legally to establish facts, even where the strongest presumptions are offered.

“The Grand Jury, impressed with a belief that the evils complained of have impaired public confidence and individual credit, injured the honest fair trader, and contributed to drain our country of its specie, corrupted the morals of many poor citizens, and finally stamped disgrace on our State, deem it a duty incumbent on them, by this public presentation, again to direct the attention of the public to this serious subject, calling upon all good citizens for their most active exertions to suppress the evil, and by their pointed disapprobation of every individual who maybe concerned, directly or indirectly in such practices, in some measure to remove the stain that has fallen on all classes of society in the minds of the good people of our sister States.”

The Report concludes with a severe reproof of the Executive of the State, and of the United States, for neglecting the proper measures to suppress these evil practices.

The tenor of this presentment leads to the belief that the word “piracy,” as used by the Grand Jury, was intended to include the more common offences of fitting out privateers within the United States, to operate against the ships of nations with which they were at peace, and that of smuggling. Certainly the grave fathers of the city would not speak of a crime, involving murder and robbery, in such mild and measured terms, as one “calculated to impair public confidence, and injure public credit, to defraud the fair dealer, to drain the country of specie, and to corrupt the morals of the people.” Such language, applied to the enormous crime of piracy, would appear quite inappropriate, not to say ridiculous. It is evident from this, as well as other proofs, that the respectable citizens, several of whom now survive, who made this report, had in view the denunciation of the offence of smuggling into New Orleans, goods captured on the high seas, by privateers, which, no doubt, seriously interfered with legitimate trade, and drew off a large amount of specie.

However, indictments for piracy were found against several of the Baratarians. One against Johnness, for piracy on the Santa, a Spanish vessel, which was captured nine miles from Grand Isle, and nine thousand dollars taken from her; also, against another, who went by the name of Johannot, for capturing another Spanish vessel with her cargo, worth thirty thousand dollars, off Trinidad. Pierre Lafitte was charged as aider and abettor in these crimes before and after the fact, as one who did, “upon land, to wit: in the city of New Orleans, within the District of Louisiana, knowingly and willingly aid, assist, procure, counsel and advise the said piracies and robberies.” It is quite evident from the character of the ships captured, that had the indictments been prosecuted to a trial, they would have resulted in modifying the crime of piracy into the offence of privateering, or that of violating the Neutrality Laws of the United States, by bringing prizes taken from Spain into its territory and selling the same.

Pierre Lafitte was arrested on these indictments. An application for bail was refused, and he was incarcerated in the Calaboose, or city prison, now occupied by the Sixth District Court of New Orleans.

These transactions, betokening a vigorous determination on the part of the authorities, to break up the establishment at Barataria, Jean Lafitte proceeded to that place and was engaged in collecting the vessels and property of the association, with a view of departing to some more secure retreat, when an event occurred, which he thought would afford him an opportunity of propitiating the favor of the government, and securing for himself and his companions a pardon for their offences.

It was on the morning of the second of September, 1814, that the settlement of Barataria was aroused by the report of cannon in the direction of the gulf. Lafitte immediately ordered out a small boat, in which, rowed by four of his men, he proceeded toward the mouth of the strait. Here he perceived a brig of war, lying just outside of the inlet, with the British colors flying at the mast-head. As soon as Lafitte’s boat was perceived, the gig of the brig shot off from her side and approached him.

In this gig were three officers, clad in naval uniform, and one in the scarlet of the British army. They bore a white signal in the bows, and a British flag in the stern of their boat. The officers proved to be Captain Lockyer, of his Majesty’s navy, with a Lieutenant of the same service, and Captain McWilliams, of the army. On approaching the boat of the Baratarians, Captain Lockyer called out his name and style, and inquired if Mr. Lafitte was at home in the bay, as he had an important communication for him. Lafitte replied, that the person they desired could be seen ashore, and invited the officers to accompany him to their settlement. They accepted the invitation, and the boats were rowed through the strait into the Bay of Barataria. On their way Lafitte confessed his true name and character; whereupon Captain Lockyer delivered to him a paper package. Lafitte enjoined upon the British officers to conceal the true object of their visit from his men, who might, if they suspected their design, attempt some violence against them. Despite these cautions, the Baratarians, on recognizing the uniform of the strangers, collected on the shore in a tumultuous and threatenino; manner, and clamored loudly for their arrest. It required all Lafitte’s art, address, and influence to calm them. Finally, however, he succeeded in conducting the British to his apartments, where they were entertained in a style of elegant hospitality, which greatly surprised them.

The best wines of old Spain, the richest fruits of the West Indies, and every variety of fish and game were spread out before them, and served on the richest carved silver plate. The affable manner of Lafitte gave great zest to the enjoyment of his guests. After the repast, and when they had all smoked cigars of the finest Cuban flavor, Lafitte requested his guests to proceed to business. The package directed to “Mr. Lafitte,” was then opened and the contents read. They consisted of a proclamation, addressed by Colonel Edward Nichols, in the service of his Britannic Majesty, and commander of the land forces on the coast of Florida, to the inhabitants of Louisiana, dated, Headquarters, Pensacola, 29th August, 1814; also a letter from the same, directed to Mr. Lafitte, as the commander at Barataria; also a letter from the Hon. Sir W. H. Percy, captain of the sloop of war Hermes, and commander of the Naval Forces in the Gulf of Mexico, dated September 1, 1814, to Lafitte; and one from the same captain Percy, written on 30th August, on the Hermes, in the Bay of Pensacola, to Captain Lockyer of the Sophia, directing him to proceed to Barataria, and attend to certain affairs there, which are fully explained.

The originals of these letters may now be seen in the records of the United States District Court in New Orleans, where they were filed by Lafitte. They contain the most flattering offers to Lafitte, on the part of the British officials, if he would aid them, with his vessels and men, in their contemplated invasion of the State of Louisiana. Captain Lockyer proceeded to enforce the offers by many plausible and cogent arguments. He stated that Lafitte, his vessels and men would be enlisted in the honorable service of the British Navy, that he would receive the rank of Captain (an offer which must have brought a smile to the face of the unnautical blacksmith of St. Philip street), and the sum of thirty thousand dollars: that being a Frenchman, proscribed and persecuted by the United States, with a brother then in prison, he should unite with the English, as the English and French were now fast friends; that a splendid prospect was now opened to him in the British navy, as from his knowledge of the Gulf Coast, he could guide them in their expedition to New Orleans, which had already started; that it was the purpose of the English Government to penetrate the upper country and act in concert with the forces in Canada; that everything was prepared to carry on the war with unusual vigor; that they were sure of success, expecting to find little or no opposition from the French and Spanish population of Louisiana, whose interests and manners were opposed and hostile to those of the Americans; and, finally, it was declared by Captain Lockyer to be the purpose of the British to free the slaves, and arm them against the white people, who resisted their authority and progress.

Lafitte, affecting an acquiescence in these propositions, begged to be permitted to go to one of the vessels lying out in the bay to consult an old friend and associate, in whose judgment he had great confidence. “Whilst he was absent, the men who had watched suspiciously the conference, many of whom were Americans, and not the less patriotic because they had a taste for privateering, proceeded to arrest the British officers, threatening to kill or deliver them up to the Americans. In the midst of this clamor and violence, Lafitte returned and immediately quieted his men, by reminding them of the laws of honor and humanity, which forbade any violence to persons who come among them with a flag of truce. He assured them that their honor and rights would be safe and sacred in his charge. He then escorted the British to their boats, and after declaring to Captain Lockyer, that he only required a few days to consider the flattering proposals, and would be ready at a certain time to deliver his final reply, took a respectful leave of his guests, and escorting them to their boat, kept them in view until they were out of reach of the men on shore.

Immediately after the departure of the British, Lafitte sat down and addressed a long letter to Mr. Blanque, a member of the House of Representatives of Louisiana, which he commenced by declaring that “though proscribed in my adopted country, I will never miss an occasion of serving her, or of proving that she has never ceased to be dear to me.” He then details the circumstances of Captain Lockyer’s arrival in his camp, and encloses the letters to him. He then proceeds to say: “I may have evaded the payment of duties to the Customhouse, but I have never ceased to be a good citizen, and all the offences I have committed have been forced upon me by certain vices in the laws.” He then expresses the hope that the service he is enabled to render the authorities, by delivering the enclosed letters, “may obtain some amelioration of the situation of an unhappy brother,” adding with considerable force and feeling, “our enemies have endeavored to work upon me, by a motive which few men would have resisted. They represented to me a brother in irons, a brother who is to me very dear, whose deliverer I might become, and I declined the proposal, well persuaded of his innocence. I am free from apprehension as to the issue of a trial, but he is sick, and not in a place where he can receive the assistance he requires.” Through Mr. Blanque, Lafitte addressed a letter to Governor Claiborne, in which he stated very distinctly his position and desires. He says:

“I offer to you to restore to this State several citizens, who, perhaps, in your eyes, have lost that sacred title; I offer you them, however, such as you could wish to find them, ready to exert their utmost efforts in defence of the country. This point of Louisiana which I occupy is of great importance in the present crisis. I tender my services to defend it, and the only reward I ask is, that a stop be put to the prosecutions against me and ray adherents, by an act of oblivion for all that has been done hitherto. I am the stray sheep wishing to return to the sheepfold. If you are thoroughly acquainted with the nature of my offences, I should appear to you much less guilty, and still worthy to discharge the duties of a good citizen. I have uever sailed under any flag but that of the Republic of Carthagena, and my vessels are perfectly regular in that respect. If I could have brought my lawful prizes into the ports of this State, I should not have employed the illicit means that have caused me to be proscribed. Should your answer not be favorable to my ardent desires, I declare to you that I will instantly leave the country to avoid the imputation of having cooperated towards an invasion on that point, which cannot fail to take place, and to rest secure in the acquittal of my own conscience.”

Upon the receipt of these letters, Governor Claiborne convoked a council of the principal officers of the army, navy and militia, then in New Orleans, to whom he submitted the letters, asking their decision on these two questions: 1st. Whether the letters were genuine? 2d. Whether it was proper that the Governor should hold intercourse or enter into any correspondence with Mr. Lafitte and his associates? To each of these questions a negative answer was given, Major General Villeré alone dissenting — this officer being (as well as the Governor, who, presiding in the council, could not give his opinion), not only satisfied as to the authenticity of the letters of the British officers, but believing that the Baratarians might be employed in a very effective manner in case of an invasion.

The only result of this council was to hasten the steps which had been previously commenced, to fit out an expedition to Barataria to break up Lafitte’s establishment. In the meantime, the two weeks asked for by Lafitte to consider the British proposal, having expired, Captain Lockyer appeared off Grand Terre, and hovered around the inlet several days, anxiously awaiting the approach of Lafitte. At last, his patience being exhausted, and mistrusting the intentions of the Baratarians, he retired. It was about this time that the spirit of Lafitte was sorely tried by the intelligence, that the constituted authorities, whom he had supplied with such valuable information, instead of appreciating his generous exertions in behalf of his country, were actually equipping an expedition to destroy his establishment. This was truly an ungrateful return for services, which, may now be justly estimated. Nor is it satisfactorily shown that mercenary motives did not mingle with those which prompted some of the parties engaged in this expedition.

The rich plunder of the “Pirate’s Retreat,” the valuable fleet of small coasting vessels that rode in the Bay of Barataria, the exaggerated stories of a vast amount of treasure, heaped up in glittering piles, in dark, mysterious caves, of chests of Spanish doubloons, buried in the sand, contributed to inflame the imagination and avarice of some of the individuals who were active in getting up this expedition.

A naval and land force was organized under Commodore Patterson and Colonel Ross, which proceeded to Barataria, and with a pompous display of military power, entered the Bay. The Baratarians at first thought of resisting with all their means, which were considerable. They collected on the beach armed, their cannon were placed in position, and matches were lighted, when lo! to their amazement and dismay, the stars and stripes became visible through the mist.

Against the power which that banner proclaimed, they were unwilling to lift their hands. They then surrendered; a few escaping up the Bayou in small boats. Lafitte, conformably to his pledge, on hearing of the expedition, had gone to the German coast — as it is called — above New Orleans. Commodore Patterson seized all the vessels of the Baratarians, and, filling them and his own with the rich goods found on the island, returned to New Orleans loaded with spoils. The Baratarians, who were captured, were ironed and committed to the Calaboose. The vessels, money and stores taken in this expedition were claimed as lawful prizes by Commodore Patterson and Colonel Ross. Out of this claim grew a protracted suit, which elicited the foregoing facts, and resulted in establishing the innocence of Lafitte of all other offences but those of privateering, or employing persons to privateer against the commerce of Spain under commissions from the Republic of Columbia, and bringing his prizes to the United States, to be disposed of, contrary to the provisions of the Neutrality Act.

The charge of piracy against Lafitte, or even against the men of the association, of which he was the chief, remains to this day unsupported by a single particle of direct and positive testimony. All that was ever adduced against them, of a circumstantial or inferential character, was the discovery among the goods taken at Barataria, of some jewelry, which was identified as that of a Creole lady, who had sailed from New Orleans seven years before, and was never heard of afterwards.

Considering the many ways in which such property might have fallen into the hands of the Baratarians, it would not be just to rest so serious a charge against them on this single fact. It is not at all improbable — though no facts of that character ever came to light — that among so many desperate characters attached to the Baratarian organization, there were not a- few who would, if the temptation were presented, “scuttle ship, or cut a throat” to advance their ends, increase their gains, or gratify a natural bloodthirstiness.

But such deeds cannot be associated with the name of Jean Lafitte, save in the idle fictions by which the taste of the youth of the country is vitiated, and history outraged and perverted. That he was more of a patriot than a pirate, that he rendered services of immense benefit to his adopted country, and should be held in respect and honor, rather than defamed and calumniated, will, we think, abundantly appear in the chapter which follows.

III

LAFITTE, THE PATRIOT

THOUGH repudiated and persecuted by the authorities of the State and Federal Government, Jean Lafitte did not cease to perform his duties as a citizen, and to warn the people of the approaching invasion. The people, as is often the case, were more sagacious on this occasion than their chief officials. They confided in the representations of Lafitte, and in the authenticity of the documents forwarded by him to Gov. Claiborne. One of the first manifestations of these feelings was the convocation of an assembly of the people at the City Exchange, on St. Louis street. This was after the tenor of Lafitte’s documents and the character of his developments had become known, to wit: on the 16th of December, 1814. This assembly was numerous and enthusiastic. It was eloquently addressed by Edward Livingston, who, in manly and earnest tones, and with telling appeals, urged the citizens to organize for the defence of their city, and thus, in a conspicuous manner, refute the calumnies which had been circulated against their fidelity to the new Republic, of which they had so recently become “part and parcel.”

These appeals met a warm response from the people. Nor did the enthusiasm which they excited vent itself in mere applause and noisy demonstrations. They produced practical results. A Committee of Public Safety was formed, to aid the authorities in the defence of the city and supply those deficiencies wliicli the exigency should develop, in the organization of the Government, as well as in the characters of those charged with its administration. This committee was composed of the following citizens: Edward Livingston, Pierre Foucher, Dussau de la Croix, Benjamin Morgan, George Ogden, Dominique Bouligny, J. A. Destrehan, John Blanque, and Augustin Macarté. They were all men of note and influence.

The leading spirit of the committee was Edward Livingston, a native of New York, and once Mayor of that great city. He had emigrated to New Orleans shortly after the cession and organization of the territory. Of profound learning, various attainments, great sagacity and industry, possessing a style of earnest eloquence and admirable force, which even now render the productions of his pen the most readable of the effusions of any of the public men, who have figured largely in political or professional spheres in the United States, Edward Livingston could not but be a leading man in any community.

The talents which many years afterwards adorned some of the highest offices under the Federal Government, and reflected so much distinction on Louisiana in the United States Senate, were eminently conspicuous and serviceable in rallying the spirits, and giving confidence and harmony of action to the people of New Orleans, during the eventful epoch to which these sketches relate. He was ably supported by his associates. Destrehan was a native of France, a man of science, resolution and intelligence, though somewhat eccentric. Benjamin Morgan was one of the first and most popular of the class of American merchants, then composing a rising party in New Orleans. P. Foucher was a Creole of Louisiana, of great ardor and activity in the defence of his natal soil. Dussau de la Croix, was a Frenchman of the ancien régime, an exile, who found in Louisiana the only sovereignty and the only soil which he deemed worth fighting for. A. Macarté was a planter of spirit, patriotism and energy. George M. Ogden was a leader of the Young America of that day, and possessed great zeal, activity, and influence among the new population. John Blanque was an intelligent, industrious and prominent member of the State Legislature. Dominique Bouligny represented the old Spanish and French colonists, who in turn had possessed Louisiana, his family being one of the oldest in the State. He was a staid, solid and true man, who afterwards filled a seat in the United States Senate, and held other offices of dignity and trust in the State.

Such was the composition of the Committee of Public Safety in New Orleans. The first act of the commitee was to send forth an address to the people. This document bears unmistakably the imprint of Edward Livingston’s genius. It is a fervid and thrilling appeal, which produced, wherever it was read among the excitable population of Louisiana, the effect of a trumpet blast, rallying the people to the defence “of their sovereignty, their property, their lives, and the dearer existence of their wives and children.”

There can be little doubt that this highly important movement and effective address were induced by the information supplied by Lafitte. Edward Livingston, the chief in the movement, had been the confidential adviser and counsellor of Lafitte since 1811. His intercourse with that much maligned individual had dispelled all doubts as to his honorable purposes. The date of the address, being about the time of Lafitte’s retirement from Barataria, and the absence of other information of the designs of the British, whose army had not then left the Chesapeake and England, all tend to the conclusion that Lafitte’s representations aroused the people to take the defence of the city into their own hands. But the value of Lafitte’s intelligence did not end here. Claiborne, persevering in his reliance in the verity of the documents dispatched to him by Lafitte, sent copies of them to General Jackson, who was then stationed at Mobile, watching the movements of the Spanish aud British at Pensacola.

The perusal of these letters, under the popular impression as to the character of the parties from which they were obtained, drew from the stern and ardent Jackson a fiery proclamation, in which he indignantly denounced the British, for their perfidy and baseness, and appealed in fervid language to all Louisianians, to repel “the calumnies which that vain-glorious boaster, Colonel Nichols, had proclaimed in his insiduous address.” The calumnies referred to were the assertions that the Creoles were crushed and oppressed by the Yankees and that they would be restored to their rightful dominion by the British. Herein we may observe the germ of that feeling which led even Jackson into some errors, and the British into the most ridiculous delusions. It was the apprehension or doubt as to the fidelity and ardor of the French settlers and Creoles of Louisiana, in the defence of the State. Subsequent events will show, despite the grossest misrepresentations of ignorant or designing persons, that in no part of the United States did there exist greater hostility to the British, or a more earnest determination to resist their approach to the city, than among the descendants of that race, which had been from time immemorial England’s national, if not natural enemy.