Custer, Elizabeth B.

Tenting on the Plains: General Custer in Kansas and Texas.

CHAPTER I | PAGE |

| Good-by to the Army of the Potomac | 17 |

CHAPTER II | |

| New Orleans After the War | 41 |

CHAPTER III | |

| A Military Execution | 59 |

CHAPTER IV | |

| Marches Through Pine Forests | 83 |

CHAPTER V | |

| Out of the Wilderness | 95 |

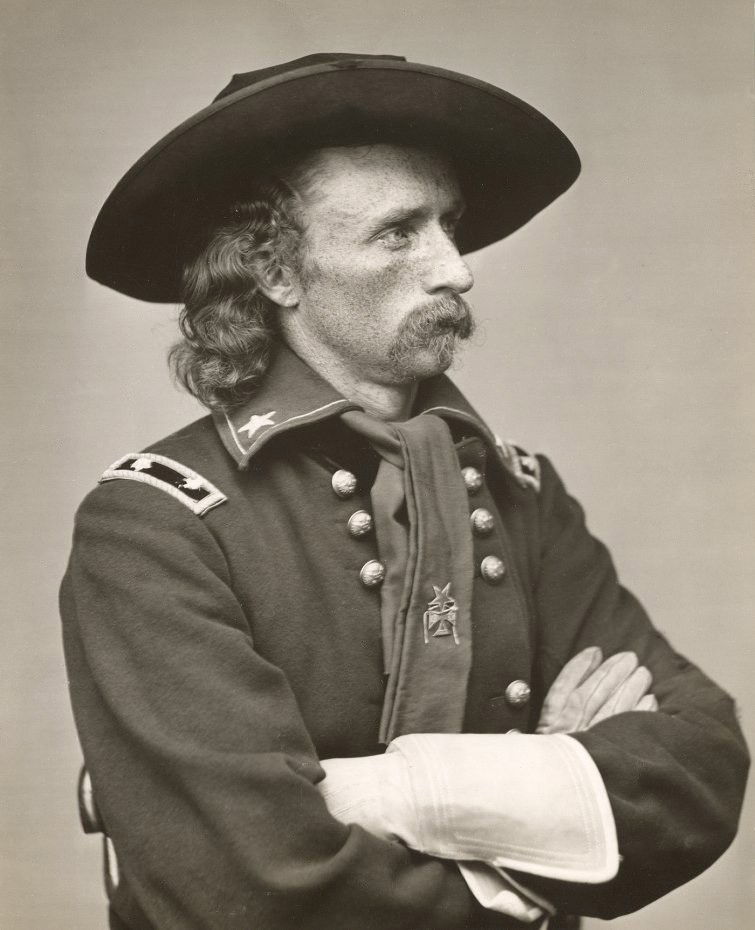

General Custer was given scant time, after the last gun of the war was fired, to realize the blessings of peace. While others hastened to discard the well-worn uniforms, and don again the dress of civilians, hurrying to the cars, and groaning over the slowness of the fast-flying trains that bore them to their homes, my husband was almost breathlessly preparing for a long journey to Texas. He did not even see the last of that grand review of the 23d and 24th of May, 1865. On the first day he was permitted to doff his hat and bow low, as he proudly led that superb body of men, the Third Division of Cavalry, in front of the grand stand, where sat the “powers that be.” Along the line of the division, each soldier straightened himself in the saddle, and felt the proud blood fill his veins, as he realized that he was one of those who, in six months, had taken 111 of the enemy’s guns, sixty-five battle-flags, and upward of 10,000 prisoners of war, while they had never lost a flag, or failed to capture a gun for which they fought.

In the afternoon of that memorable day General Custer and his staff rode to the outskirts of Washington, where his beloved Third Cavalry Division had encamped after returning from taking part in the review. The trumpet was sounded, and the call brought these war-worn veterans out once more, not for a charge, not for duty, but to say that word which we, who have been compelled to live in its mournful sound so many years, dread even to write. Down the line rode their yellow-haired “boy general,” waving his hat, but setting his teeth and trying to hold with iron nerve the quivering muscles of his speaking face; keeping his eyes wide open, that the moisture dimming their vision might not gather and fall. Cheer after cheer rose on that soft spring air. Some enthusiastic voice started up afresh, before the hurrahs were done, “A tiger for old Curley!” Off came the hats again, and up went hundreds of arms, waving the good-by and wafting innumerable blessings after the man who was sending them home in a blaze of glory, with a record of which they might boast around their firesides. I began to realize, as I watched this sad parting, the truth of what the General had been telling me; he held that no friendship was like that cemented by mutual danger on the battle-field.

The soldiers, accustomed to suppression through strict military discipline, now vehemently expressed their feelings; and though it gladdened the General’s heart, it was still the hardest sort of work to endure it all without show of emotion. As he rode up to where I was waiting, he could not, dared not, trust himself to speak to me. To those intrepid men he was indebted for his success. Their unfailing trust in his judgment, their willingness to follow where he led — ah! he knew well that one looks upon such men but once in a lifetime. Some of the soldiers called out for the General’s wife. The staff urged me to ride forward to the troops, as it was but a little thing thus to respond to their good-by. I tried to do so, but after a few steps, I begged those beside whom I rode to take me back to where we had been standing. I was too overcome, from having seen the suffering on my husband’s face, to endure any more sorrow.

As the officers gathered about the General and wrung his hand in parting, to my surprise the soldiers gave me a cheer. Though very grateful for the tribute to me as their acknowledged comrade, I did not feel that I deserved it. Hardships such as they had suffered for a principle require a far higher order of character than the same hardships endured when the motive is devotion individualized.

Once more the General leaped into the saddle, and we rode rapidly out of sight. How glad I was, as I watched the set features of my husband’s face, saw his eyes fixed immovably in front of him, listened in vain for one word from his overburdened heart, that I, being a woman, need not tax every nerve to suppress emotion, but could let the tears stream down my face, on all our silent way back to the city.

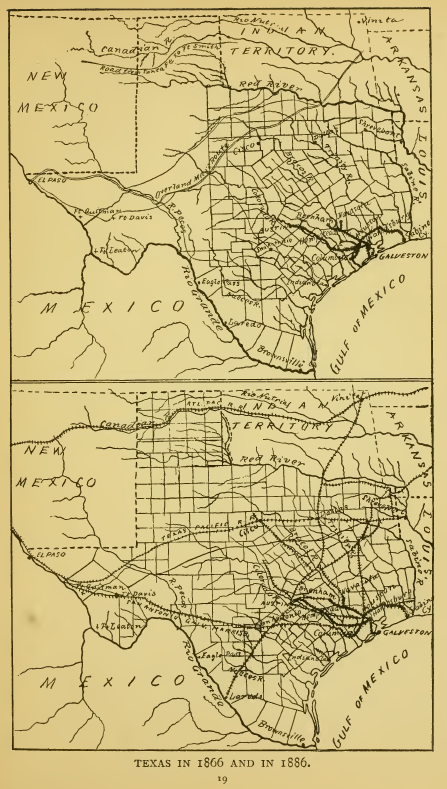

Then began the gathering of our “traps,” a hasty collection of a few suitable things for a Southern climate, orders about shipping the horses, a wild tearing around of the improvident, thoughtless staff — good fighters, but poor providers for themselves. Most of them were young men, for whom my husband had applied when he was made a brigadier. His first step after his promotion was to write home for his schoolmates, or select aides from his early friends then in service. It was a comfort, when I found myself grieving over the parting with my husband’s Division, that our military family were to go with us. At dark we were on the cars, with our faces turned southward. To General Custer this move had been unexpected. General Sheridan knew that he needed little time to decide, so he sent for him as soon as we encamped at Arlington, after our march up from Richmond, and asked if he would like to take command of a division of cavalry on the Red River in Louisiana, and march throughout Texas, with the possibility of eventually entering Mexico. Our Government was just then thinking it was high time the French knew that if there was any invasion of Mexico, with an idea of a complete “gobbling up” of that country, the one to do the seizure and gather in the spoils was Brother Jonathan. Very wisely, General Custer kept this latter part of the understanding why he was sent South from the “weepy” part of his family. He preferred transportation by steamer, rather than to be floated southward by floods of feminine tears. All I knew was, that Texas, having been so outside of the limit where the armies marched and fought, was unhappily unaware that the war was over, and continued a career of bushwhacking and lawlessness that was only tolerated from necessity before the surrender, and must now cease. It was considered expedient to fit out two detachments of cavalry, and start them on a march through the northern and southern portions of Texas, as a means of informing that isolated State that depredations and raids might come to an end. In my mind, Texas then seemed the stepping-off place; but I was indifferent to the points of the compass, so long as I was not left behind.

The train in which we set out was crowded with a joyous, rollicking, irrepressible throng of discharged officers and soldiers, going home to make their swords into ploughshares. Everybody talked with everybody, and all spoke at once. The Babel was unceasing night and day; there was not a vein that was not bursting with joy. The swift blood rushed into the heart and out again, laden with one glad thought, “The war is over!” At the stations, soldiers tumbled out and rushed into some woman’s waiting arms, while bands tooted excited welcomes, no one instrument according with another, because of throats overcharged already with bursting notes of patriotism that would not be set music. The customary train of street gamins, who imitate all parades and promptly copy the pomp of the circus and other processions, stepped off in a mimic march, following the conquering heroes as they were lost to our sight down the street, going home.

Sometimes the voices of the hilarious crowd at the station were stilled, and a hush of reverent silence preceded the careful lifting from the car of a stretcher bearing a form broken and bleeding from wounds, willingly borne, that the home to which he was coming might be unharmed. Tender women received and hovered lovingly over the precious freight, strong arms carried him away; and we contrasted the devoted care, the love that would teach new ways to heal, with the condition of the poor fellows we had left in the crowded Washington hospitals, attended only by strangers. Some of the broken-to-pieces soldiers were on our train, so deftly mended that they stumped their way down the platform, and began their one-legged tramp through life, amidst the loud huzzas that a maimed hero then received. They even joked about their misfortunes. I remember one undaunted fellow, with the fresh color of buoyant youth beginning again to dye his cheek, even after the amputation of a leg, which so depletes the system. He said some grave words of wisdom to me in such a roguish way, and followed up his counsel by adding, “You ought to heed such advice from a man with one foot in the grave.”

We missed all the home-coming, all the glorification awarded to the hero. General Custer said no word of regret. He had accepted the offer for further active service, and gratefully thanked his chief for giving him the opportunity. I, however, should have liked to have him get some of the celebrations that our country was then showering on its defenders. I missed the bonfires, the processions, the public meeting of distinguished citizens, who eloquently thanked the veterans, the editorials that lauded each townsman’s deed, the poetry in the corner of the newspaper that was dedicated to a hero, the overflow of a woman’s heart singing praise to her military idol. But the cannon were fired, the drums beat, the music sounded for all but us. Offices of trust were offered at once to men coming home to private life, and towns and cities felt themselves honored because some one of their number had gone out and made himself so glorious a name that his very home became celebrated. He was made the mayor, or the Congressman, and given a home which it would have taken him many years of hard work to earn. Song, story and history have long recounted what a hero is to a woman. Imagination pictured to my eye troops of beautiful women gathering around each gallant soldier on his return. The adoring eyes spoke admiration, while the tongue subtly wove, in many a sentence, its meed of praise. The General and his staff of boys, loving and reverencing women, missed what men wisely count the sweetest of adulation. One weather-beaten slip of a girl had to do all their banqueting, cannonading, bonfiring, brass-banding, and general hallelujahs all the way to Texas, and — yes, even after we got there; for the Southern women, true to their idea of patriotism, turned their pretty faces away from our handsome fellows, and resisted, for a long time, even the mildest flirtation.

The drawing-room car was then unthought of in the minds of those who plan new luxuries as our race demand more ease and elegance. There was a ladies’ car, to which no men unaccompanied by women were admitted. It was never so full as the other coaches, and was much cleaner and better ventilated. This was at first a damper to the enjoyment of a military family, who lost no opportunity of being together, for it compelled the men to remain in the other cars. The scamp among us devised a plan to outwit the brakemen; he borrowed my bag just before we were obliged to change cars, and after waiting till the General and I were safely seated, boldly walked up and demanded entrance, on the plea that he had a lady inside. This scheme worked so well that the others took up the cue, and my cloak, bag, umbrella, lunch-basket, and parcel of books and papers were distributed among the rest before we stopped, and were used to obtain entrance into the better car. Even our faithful servant, Eliza, was unexpectedly overwhelmed with urgent offers of assistance; for she always went with us, and sat by the door. This plan was a great success, in so far as it kept our party together, but it proved disastrous to me, as the scamp forgot my bag at some station, and I was minus all those hundred-and-one articles that seem indispensable to a traveler’s comfort. In that plight I had to journey until, in some merciful detention, we had an hour in which to seek out a shop, and hastily make the necessary purchases.

At one of our stops for dinner we all made the usual rush for the dining-hall, as in the confusion of over-laden trains at that excited time it was necessary to hurry, and, besides, as there were delays and irregularities in traveling, on account of the home-coming of the troops, we never knew how long it might be before the next eating-house was reached. The General insisted upon Eliza’s going right with us, as no other table was provided. The proprietor, already rendered indifferent to people’s comfort by his extraordinary gains, said there was no table for servants. Eliza, the best-bred of maids, begged to go back dinnerless into the car, but the General insisted on her sitting down between us at the crowded table. A position so unusual, and to her so totally out of place, made her appetite waver, and it vanished entirely when the proprietor came, and told the General that no colored folks could be allowed at his table. My husband quietly replied that he had been obliged to give the woman that place, as the house had provided no other. The determined man still stood threateningly over us, demanding her removal, and Eliza uneasily and nervously tried to go. I trembled, and the fork failed to carry the food, owing to a very wobbly arm. The General firmly refused, the staff rose about us, and all along the table up sprang men we had supposed to be citizens, as they were in the dress of civilians. “General, stand your ground; we’ll back you; the woman shall have food.” How little we realize in these piping times of peace, how great a flame a little fire kindled in those agitating days. The proprietor slunk back to his desk; the General and his hungry staff went on eating as calmly as ever; Eliza hung her embarrassed head, and her mistress idly twirled her useless fork — while the proprietor made $1.50 clear gain on two women that were too frightened to swallow a mouthful. I spread a sandwich for Eliza, while the General, mindful of the returning hunger of the terrified woman, and perfectly indifferent as to making himself ridiculous with parcels, marched by the infuriated but subdued bully, with either a whole pie or some such modest capture in his hand. We had put some hours of travel between ourselves and the “twenty-minutes-for-dinner” place which came so near being a battle-ground, before Eliza could eat what we had brought for her.

I wonder if any one is waiting for me to say that this incident happened south of the Mason and Dixon line. It did not. It was in Ohio — I don’t remember the place. After all, the memory over which one complains, when he finds how little he can recall, has its advantages. It hopelessly buries the names of persons and places, when one starts to tell tales out of school. It is like extracting the fangs from a rattlesnake; the reptile, like the story, may be very disagreeable, but I can only hope that a tale unadorned with names or places is as harmless as a snake with its poison withdrawn.

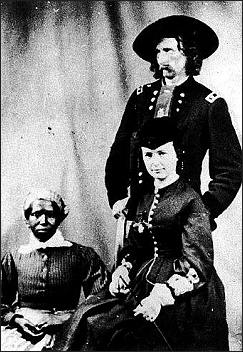

I must stop a moment and give our Eliza, on whom this battle was waged, a little space in this story, for she occupied no small part in the events of the six years after; and when she left us and took an upward step in life by marrying a colored lawyer, I could not reconcile myself to the loss; and though she has lived through all the grandeur of a union with a man “who gets a heap of money for his speeches in politics, and brass bands to meet him at the stations, Miss Libbie,” she came to my little home not long since with tears of joy illuminating the bright bronze of her expressive face. It reminded me so of the first time I knew that the negro race regarded shades of color as a distinctive feature, a beauty or a blemish, as it might be. Eliza stood in front of a bronze medallion of my husband when it was first sent from the artist’s in 1865, and amused him hugely, by saying, in that partnership manner she had in our affairs, “Why, Ginnel, it’s jest my color.” After that, I noticed that she referred to her race according to the deepness of tint, telling me, with scorn, of one of her numerous suitors: “Why, Miss Libbie, he needent think to shine up to me; he’s nothing but a black African.” I am thus introducing Eliza, color and all, that she may not seem the vague character of other days; and whoever chances to meet her will find in her a good war historian, a modest chronicler of a really self-dying and courageous life. It was rather a surprise to me that she was not an old woman when I saw her again this autumn, after so many years, but she is not yet fifty. I imagine she did so much mothering in those days when she comforted me in my loneliness, and quieted me in my frights, that I counted her old even then.

Eliza requests that she be permitted to make her little bow to the reader, and repeat a wish of hers that I take great pains in quoting her, and not represent her as saying, “like field-hands, whar and thar.” She says her people in Virginia, whom she reverences and loves, always taught her not to say “them words; and if they should see what I have told you they’d feel bad to think I forgot.” If whar and thar appear occasionally in my efforts to transfer her literally to these pages, it is only a lapsus linguæ on her part. Besides, she has lived North so long now, there is not that distinctive dialect peculiar to the Southern servant. In her excitement, narrating our scenes of danger or pleasure or merriment, she occasionally drops into expressions that belonged to her early life. It is the fault of her historian if these phrases get into print. To me they are charming, for they are Eliza in undress uniform — Eliza without her company manners.

She describes her leaving the old plantation during war times: “I jined the Ginnel at Amosville, Rappahannock County, in August, 1863. Everybody was excited over freedom, and I wanted to see how it was. Everybody keeps asking me why I left. I can’t see why they can’t recollect what war was for, and that we was all bound to try and see for ourselves how it was. After the ’Mancipation, everybody was a-standin’ up for liberty, and I wasent goin’ to stay home when everybody else was a-goin’. The day I came into camp, there was a good many other darkeys from all about our place. We was a-standin’ round waitin’ when I first seed the Ginnel.

“He and Captain Lyon cum up to me, and the Ginnel says, ‘Well, what’s your name!’ I told him Eliza; and he says, looking me all over fust, ‘Well, Eliza, would you like to cum and live with me?’ I waited a minute, Miss Libbie. I looked him all over, too, and finally I sez, ‘I reckon I would.’ So the bargain was fixed up. But, oh, how awful lonesome I was at fust, and I was afraid of everything in the shape of war. I used to wish myself back on the old plantation with my mother. I was mighty glad when you cum, Miss Libbie. Why, sometimes I never sot eyes on a woman for weeks at a time.”

Eliza’s story of her war life is too long for these pages; but in spite of her confession of being so “‘fraid,” she was a marvel of courage. She was captured by the enemy, escaped, and found her way back after sunset to the General’s camp. She had strange and narrow escapes. She says, quaintly: “Well, Miss Libbie, I set in to see the war, beginning and end. There was many niggers that cut into cities and huddled up thar, and laid around and saw hard times; but I went to see the end, and I stuck it out. I allus thought this, that I didn’t set down to wait to have ’em all free me. I helped to free myself. I was all ready to step to the front whenever I was called upon, even if I didn’t shoulder the musket. Well, I went to the end, and there’s many folks says that a woman can’t follow the army without throwing themselves away, but I know better. I went in, and I cum out with the respect of the men and the officers.”

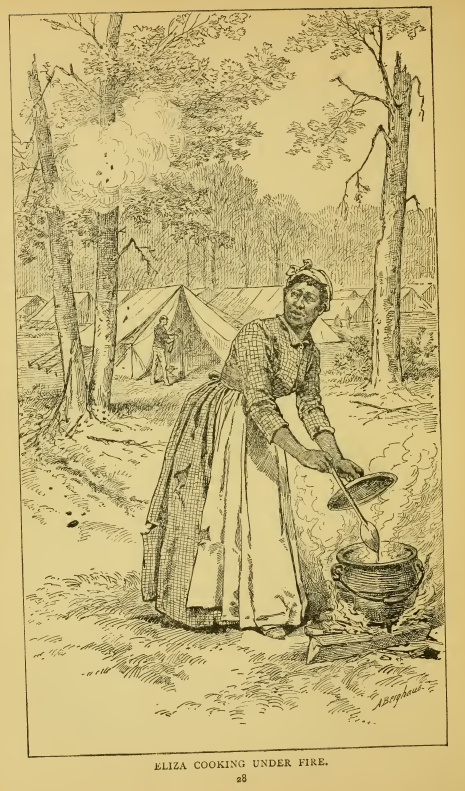

Eliza often cooked under fire, and only lately one of the General’s staff, recounting war days, described her as she was preparing the General’s dinner in the field. A shell would burst near her; she would turn her head in anger at being disturbed, unconscious that she was observed, begin to growl to herself about being obliged to move, but take up her kettle and frying-pan, march farther away, make a new fire, and begin cooking as unperturbed as if it were an ordinary disturbance instead of a sky filled with bits of falling shell. I do not repeat that polite fiction of having been on the spot, as neither the artist nor I had Eliza’s grit or pluck; but we arranged the camp-kettle, and Eliza fell into the exact expression, as she volubly began telling the tale of “how mad those busting shells used to make her.” It is an excellent likeness, even though Eliza objects to the bandana, which she has abandoned in her new position; and I must not forget that I found her one day turning her head critically from side to side looking at her picture; and, out of regard to her, will mention that her nose, of which she is very proud, is, she fears, a touch too flat in the sketch. She speaks of her dress as “completely whittled out with bullets,” but she would like me to mention that “she don’t wear them rags now.”

When Eliza reached New York this past autumn, she told me, when I asked her to choose where she would go, as my time was to be entirely given to her, that she wanted first to go to the Fifth Avenue Hotel and see if it looked just the same as it did “when you was a bride, Miss Libbie, and the Ginnel took you and me there on leave of absence.” We went through the halls and drawing-rooms, narrowly watched by the major-domo, who stands guard over tramps, but fortified by my voice, she “oh’d” and “ah’d” over its grandeur to her heart’s content. One day I left her in Madison Square, to go on a business errand, and cautioned her not to stray away. When I returned I asked anxiously, “Did any one speak to you, Eliza?” “Everybody, Miss Libbie,” as nonchalant and as complacent as if it were her idea of New York hospitality. Then she begged me to go round the Square, “to hunt a lady from Avenue A, who see’d you pass with me, Miss Libbie, and said she knowed you was a lady, though I reckon she couldn’t ‘count for me and you bein’ together.” We found the Avenue A lady, and I was presented, and, to her satisfaction, admired the baby that had been brought over to that blessed breathing-place of our city.

The Elevated railroad was a surprise to Eliza. She “didn’t believe it would be so high.” At that celebrated curve on the Sixth Avenue line, where Monsieur de Lesseps, even, exclaimed, “Mon Dieu! but the Americans are a brave people,” the poor, frightened woman clung to me and whispered, “Miss Libbie, couldn’t we get down anyway? Miss Libbie, I’se seed enough. I can tell the folks at home all about it now. Oh, I never did ’spect to be so near heaven till I went up for good.”

At the Brooklyn Bridge she demurred. She is so intelligent that I wanted to have her see the shipping, the wharves, the harbor, and the statue of Liberty; but nothing kept her from flight save her desire to tell her townspeople that she had seen the place where the crank jumped off. The police-man, in answer to my inquiry, commanded us in martial tones to stay still till he said the word; and when the wagon crossing passed the spot, and the maintainer of the peace said “Now!” Eliza shivered and whispered, “Now, let’s go home, Miss Libbie. I dun took the cullud part of the town fo’ I come; the white folks hain’t seen what I has, and they’ll be took when I tell ‘em;” and off she toddled, for Eliza is not the slender woman I once knew her.

Her description of the Wild West exhibition was most droll. I sent her down because we had lived through so many of the scenes depicted, and I felt sure that nothing would recall so vividly the life on the frontier as that most realistic and faithful representation of a Western life that has ceased to be, with advancing civilization. She went to Mr. Cody’s tent after the exhibition, to present my card of introduction, for he had served as General Custer’s scout after Eliza left us, and she was, therefore, unknown to him except by hearsay. They had twenty subjects in common; for Eliza, in her way, was as deserving of praise as was the courageous Cody. She was delighted with all she saw, and on her return her description of it, mingled with imitations of the voices of the hawkers and the performers, was so incoherent that it presented only a confused jumble to my ears. The buffalo were a surprise, a wonderful revival to her of those hunting-days when our plains were darkened by the herds. “When the buffalo cum in, I was ready to leap up and holler, Miss Libbie; it ’minded me of ole times. They made me think of the fifteen the Ginnel fust struck in Kansas. He jest pushed down his ole hat, and went after ’em linkety-clink. Well, Miss Libbie, when Mr. Cody come up, I see at once his back and hips was built precisely like the Ginnel, and when I come on to his tent, I jest said to him: ‘Mr. Buffalo Bill, when you cum up to the stand and wheeled round, I said to myself, “Well, if he ain’t the ’spress image of Ginnel Custer in battle I never seed any one that was!”’ I jest wish he’d come to my town and give a show! He could have the hull fairground there. My! he could raise money so fast ’twouldn’t take him long to pay for a church. And the shootin’ and ridin’! why, Miss Libbie, when I seed one of them ponies brought out, I know’d he was one of the hatefulest, sulkiest ponies that ever lived. He was a-prancin’ and curvin’, and he jest stretched his ole neck and throwed the men as fast as ever they got on.”

After we had strolled through the streets for many days, Eliza always amusing me by her droll comments, she said to me one day: “Miss Libbie, you don’t take notice, when me and you’s walking on, a-lookin’ into shop-windows and a-gazin’ at the new things I never see before, how the folks does stare at us. But I see ‘em a-gazin’, and I can see ‘em a-ponderin’ and sayin’ to theirsel’s, ‘Well, I do declar’! that’s a lady, there ain’t no manner of doubt. She’s one of the bong tong; but whatever she’s a-doin’ with that old scrub nigger, I can’t make out.’” I can hardly express what a recreation and delight it was to go about with this humorous woman and listen to her comments, her unique criticisms, her grateful delight, when she turned on the street to say: “Oh, what a good time me and you is having, Miss Libbie, and how I will ’stonish them people at home!” The best of it all was the manner in which she brought back our past, and the hundred small events we recalled, which were made more vivid by the imitation of voice, walk, gesture she gave in speaking of those we followed in the old marching days.

On this journey to Texas some accident happened to our engine, and detained us all night. We campaigners, accustomed to all sorts of unexpected inconveniences, had learned not to mind discomforts. Each officer sank out of sight into his great-coat collar, and slept on by the hour, while I slumbered till morning, curled up in a heap, thankful to have the luxury of one seat to myself. We rather gloried over the citizens who tramped up and down the aisle, groaning and becoming more emphatic in their language as the night advanced, indulging in the belief that the women were too sound asleep to hear them. I wakened enough to hear one old man say, fretfully, and with many adjectives: “Just see how those army folks sleep; they can tumble down anywhere, while I am so lame and sore, from the cramped-up place I am in, I can’t even doze.” As morning came we noticed our scamp at the other end of the car, with his legs stretched comfortably on the seat turned over in front of him. All this unusual luxury he accounted for afterward, by telling us the trick that his ingenuity had suggested to obtain more room. “You see,” the wag said, “two old codgers sat down in front of my pal and me, late last night, and went on counting up their gains in the rise of corn, owing to the war, which, to say the least, was harrowing to us poor devils who had fought the battles that had made them rich and left us without a ‘red.’ I concluded, if that was all they had done for their country, two of its brave defenders had more of a right to the seat than they had. I just turned to H—— and began solemnly to talk about what store I set by my old army coat, then on the seat they occupied; said I couldn’t give it up, though I had been obliged to cover a comrade who had died of small-pox, I not being afraid of contagion, having had varioloid. Well, I got that far when the eyes of the old galoots started out of their heads, and they vamoosed the ranche, I can tell you, and I saw them peering through the window at the end of the next car, the horror still in their faces.” The General exploded with merriment. How strange it seems, to contrast those noisy, boisterous times, when everybody shouted with laughter, called loudly from one end of the car to the other, told stories for the whole public to hear, and sang war-songs, with the quiet, orderly travelers of nowadays, who, even in the tremor of meeting or parting, speak below their breath, and, ashamed of emotion, quickly wink back to its source the prehistoric tear.

We bade good-by to railroads at Louisville, and the journeying south was then made by steamer. How peculiar it seemed to us, accustomed as we were to lake craft with deep hulls, to see for the first time those flat-bottomed boats drawing so little water, with several stories, and upper decks loaded with freight. I could hardly rid myself of the fear that, being so top-heavy, we would blow over. The tempests of our western lakes were then my only idea of sailing weather. Then the long, sloping levees, the preparations for the rise of water, the strange sensation, when the river was high, of looking over the embankment, down upon the earth! It is a novel feeling to be for the first time on a great river, with such a current as the Mississippi flowing on above the level of the plantations, hemmed in by an embankment on either side. Though we saw the manner of its construction at one point where the levee was being repaired, and found how firmly and substantially the earth was fortified with stone and logs against the river, it still seemed to me an unnatural sort of voyaging to be above the level of the ground; and my tremors on the subject, and other novel experiences, were instantly made use of as a new and fruitful source of practical jokes. For instance, the steamer bumped into the shore anywhere it happened to be wooded, and an army of negroes appeared, running over the gang-plank like ants. Sometimes at night the pine torches, and the resinous knots burning in iron baskets slung over the side of the boat, made a weird and gruesome sight, the shadows were so black, the streams of light so intense, while the hurrying negroes loaded on the wood, under the brutal voice of a steamer’s mate. Once a negro fell in. They made a pretense of rescuing him, gave it up soon, and up hurried our scamp to the upper deck to tell me the horrible tale. He had good command of language, and allowed no scruples to spoil a story. After that I imagined, at every night wood-lading, some poor soul was swept down under the boat and off into eternity. The General was sorry for me, and sometimes, when I imagined the calls of the crew to be the despairing wail of a dying man, he made pilgrimages, for my sake, to the lower deck to make sure that no one was drowned. My imaginings were not always so respected, for the occasion gave too good an opportunity for a joke, to be passed quietly by. The scamp and my husband put their heads together soon after this, and prepared a tale for the “old lady,” as they called me. As we were about to make a landing, they ran to me and said, “Come, Libbie, hurry up! hurry up! You’ll miss the fun if you don’t scrabble.” “Miss what?” was my very natural question, and exactly the reply they wanted me to make. “Why, they’re going to bury a dead man when we land.” I exclaimed in horror, “Another man drowned? how can you speak so irreverently of death?” With a “do you suppose the mate cares for one darkey more or less?” they dragged me to the deck. There I saw the great cable which was used to tie us up, fastened to a strong spar, the two ends of which were buried in the bank. The ground was hollowed out underneath the centre, and the rope slipped under to fasten it around the log. After I had watched this process of securing our boat to the shore, these irrepressibles said, solemnly, “The sad ceremony is now ended, and no other will take place till we tie up at the next stop.” When it dawned upon me that “tying up” was called, in steamer vernacular, “burying a dead man,” my eyes returned to their proper place in the sockets, breath came back, and indignation filled my soul. Language deserts us at such moments, and I resorted to force.

The Ruth was accounted one of the largest and most beautiful steamers that had ever been on the Mississippi River, her expenses being $1,000 a day. The decorations were sumptuous, and we enjoyed every luxury. We ate our dinners to very good music, which the boat furnished. We had been on plain fare too long not to watch with eagerness the arrival of the procession of white-coated negro waiters, who each day came in from the pastry-cook with some new device in cake, ices, or confectionery. There was a beautiful Ruth gleaning in a field, in a painting that filled the semicircle over the entrance of the cabin. Ruths with sheaves held up the branches of the chandeliers, while the pretty gleaner looked out from the glass of the stateroom doors. The captain being very patient as well as polite, we pervaded every corner of the great boat. The General and his boy-soldiers were too accustomed to activity to be quiet in the cabin. Even that unapproachable man at the wheel yielded to our longing eyes, and let us into his round tower. Oh, how good he was to me! The General took me up there, and the pilot made a place for us, where, with my bit of work, I listened for hours to his stories. My husband made fifty trips up and down, sometimes detained when we were nearing an interesting point, to hear the story of the crevasse. Such tales were thrilling enough even for him, accustomed as he then was to the most exciting scenes. The pilot pointed out places where the river, wild with the rush and fury of spring freshets, had burst its way through the levees, and, sweeping over a peninsula, returned to the channel beyond, utterly annihilating and sinking out of sight forever the ground where happy people had lived on their plantations. It was a sad time to take that journey, and even in the midst of our intense enjoyment of the novelty of the trip, the freedom from anxiety, and the absence of responsibility of any kind, I recall how the General grieved over the destruction of plantations by the breaks in the levee. The work on these embankments was done by assessment, I think. They were cared for as our roads and bridges are kept in order, and when men were absent in the war, only the negroes were left to attend to the repairing. But the inundations then were slight, compared with many from which the State has since suffered. In 1874 thirty parishes were either wholly or partly overflowed by an extraordinary rise in the river. On our trip we saw one plantation after another submerged, the grand old houses abandoned, and standing in lakes of water, while the negro quarters and barns were almost out of sight. Sometimes the cattle huddled on a little rise of ground, helpless and pitiful. We wished, as we used to do in that beautiful Shenandoah Valley, that if wars must come, the devastation of homes might be avoided; and I usually added, with one of the totally impracticable suggestions conjured up by a woman, that battles might be fought in desert places.

A Southern woman, who afterward entertained us, described, in the graphic and varied language which is their gift, the breaking of the levee on their own plantation. How stealthily the small stream of water crept on and on, until their first warning was its serpent-like progress past their house. Then the excitement and rush of all the household to the crevasse, the hasty gathering in of the field-hands, and the homely devices for stopping the break until more substantial materials could be gathered. It was a race for life on all sides. Each one, old or young, knew that his safety depended on the superhuman effort of the first hour of danger. In our safe homes we scarcely realize what it would be to look out from our windows upon, what seemed to me, a small and insufficient mound of earth stretching along the frontage of an estate, and know that it was our only rampart against a rushing flood, which seemed human in its revengeful desire to engulf us.

The General was intensely interested in those portions of the country where both naval and land warfare had been carried on. At Island No. 10, and Fort Pillow especially, there seemed, even then, no evidence that fighting had gone on so lately. The luxuriant vegetation of the South had covered the fortifications; nature seemed hastening to throw a mantle over soil that had so lately been reddened with such a precious dye. The fighting had been so desperate at the latter point, it is reported the Confederate General Forrest said: “The river was dyed with the blood of the slaughtered for two hundred yards.”

At one of our stops on the route, the Confederate General Hood came on board, to go to a town a short distance below, and my husband, hearing he was on the boat, hastened to seek him out and introduce himself. Such reunions have now become common, I am thankful to say, but I confess to watching curiously every expression of those men, as it seemed very early, in those times of excited and vehement conduct, to begin such overtures. And yet I did not forget that my husband sent messages of friendship to his classmates on the other side throughout the war. As I watched this meeting, they looked, while they grasped each other’s hand, as if they were old-time friends happily united. After they had carried on an animated conversation for awhile, my husband, always thinking how to share his enjoyment, hurried to bring me into the group. General Custer had already taught me, even in those bitter times, that he knew his classmates fought from their convictions of right, and that, now the war was over, I must not be adding fuel to a fire that both sides should strive to smother.

General Hood was tall, fair, dignified and soldierly. He used his crutch with difficulty, and it was an effort for him to rise when I was presented. We three instantly resumed the war talk that my coming had interrupted. The men plied each other with questions as to the situation of troops at certain engagements, and the General fairly bombarded General Hood with inquiries about the action on their side in different campaigns. At that time nothing had been written for Northern papers and magazines by the South. All we knew was from the brief accounts in the Southern newspapers that our pickets exchanged, and from papers captured or received from Europe by way of blockade-runners. We were greatly amused by the comical manner in which General Hood described his efforts to suit himself to an artificial leg, after he had contributed his own to his beloved cause. In his campaigns he was obliged to carry an extra one, in case of accident to the one he wore, which was strapped to his led horse. He asked me to picture the surprise of the troops who captured all the reserve horses at one time, and found this false leg of his suspended from the saddle. He said he had tried five, at different times, to see which of the inventions was lightest and easiest to wear; “and I am obliged to confess, Mrs. Custer, much as you may imagine it goes against me to do so, that of the five — English, German, French, Yankee and Confederate — the Yankee leg was the best of all.” When General Custer carefully helped the maimed hero down the cabin stairs and over the gangway, we bade him good-by with real regret — so quickly do soldiers make and cement a friendship when both find the same qualities to admire in each other.

The novelty of Mississippi travel kept even our active, restless party interested. One of our number played guitar accompaniments, and we sang choruses on deck at night, forgetting that the war-songs might grate on the ears of some of the people about us. The captain and steamer’s crew allowed us to roam up and down the boat at will, and when we found, by the map or crew, that we were about to touch the bank in a hitherto unvisited State, we were the first to run over the gang-plank and caper up and down the soil, to add a new State to our fast-swelling list of those in which we had been. We rather wondered, though, what we would do if asked questions by our elders at home as to what we thought of Arkansas, Mississippi and Tennessee, as we had only scampered on and off the river bank of those States while the wooding went on. We were like children let out of school, and everything interested us. Even the low water was an event. The sudden stop of our great steamer, which, large as it was, drew but a few feet of water, made the timbers groan and the machinery creak. Then we took ourselves to the bow, where the captain, mate and deck-hands were preparing for a siege, as the force of the engines had ploughed us deep into a sand-bar. There was wrenching, veering and struggling of the huge boat; and at last a resort to those two spars which seem to be so uselessly attached to each side of the forward deck of the river steamers. These were swung out and plunged into the bank, the rope and tackle put into use, and with the aid of these stilts we were skipped over the sand-bar into the deeper water. It was on that journey that I first heard the name Mr. Clemens took as his nom de plume. The droning voice of the sailor taking soundings, as we slowly crept through low water, called out, “Mark twain!” and the pilot answered by steering the boat according to the story of the plumb-line.

The trip on a Mississippi steamer, as we knew it, is now one of the things of the past. It was accounted then, and before the war, our most luxurious mode of travel. Every one was sociable, and in the constant association of the long trip some warm friendships sprung up. We had then our first acquaintance with Bostonians as well as with Southerners. Of course, it was too soon for Southern women, robbed of home, and even the necessities of life, by the cruelty of war, to be wholly cordial. We were more and more amazed at the ignorance in the South concerning the North. A young girl, otherwise intelligent, thawed out enough to confess to me that she had really no idea that Yankee soldiers were like their own physically. She imagined they would be as widely different as black from white, and a sort of combination of gorilla and chimpanzee. Gunboats had but a short time before moored at the levee that bounded her grandmother’s plantation, and the negroes ran into the house crying the terrible news of the approach of the enemy. The very thought of a Yankee was abhorrent; but the girl, more absorbed with curiosity than fear, slipped out of the house to where a view of the walk from the landing was to be had, and, seeing a naval officer approaching, raced back to her grandmother, crying out in surprise at finding a being like unto her own people, “Why, it’s a man!”

As we approached New Orleans the plantations grew richer. The palmetto and the orange, by which we are “twice blessed” in its simultaneous blossom and fruit; the oleander, treasured in conservatories at home, here growing to tree size along the country roads, all charmed us. The wide galleries around the two stories of the houses were a delight. The course of our boat was often near enough the shore for us to see the family gathered around the supper-table spread on the upper gallery, which was protected from the sun by blinds or shades of matting.

We left the steamer at New Orleans with regret. It seems, even now, that it is rather too bad we have grown into so hurried a race that we cannot spare the time to travel as leisurely or luxuriously as we did then. Even pleasure-seekers going off for a tour, when they are not restricted by time nor mode of journeying, study the time-tables closely, to see by which route the quickest passage can be made.

We were detained, by orders, for a little time in New Orleans, and the General was enthusiastic over the city. All day we strolled through the streets, visiting the French quarter, contrasting the foreign shopkeepers — who were never too hurried to be polite — with our brusque, business-like Northern clerk; dined in the charming French restaurants, where we saw eating made a fine art. The sea-food was then new to me, and I hovered over the crabs, lobsters and shrimps, but remember how amused the General was by my quick retreat from a huge live green turtle, whose locomotion was suspended by his being turned upon his back. He was unconsciously bearing his own epitaph fastened upon his shell: “I will be served up for dinner at 5 p. m.” We of course spent hours, even matutinal hours, at the market, and the General drank so much coffee that the old mammy who served him said many a “Mon Dieu!” in surprise at his capacity, and volubly described in French to her neighbors what marvels a Yankee man could do in coffee-sipping. For years after, when very good coffee was praised, or even Eliza’s strongly commended, his ne plus ultra was, “Almost equal to the French market.” We here learned what artistic effects could be produced with prosaic carrots, beets, onions and turnips. The General looked with wonder upon the leisurely creole grandee who came to order his own dinner. After his epicurean selection he showed the interest and skill that a Northern man might in the buying of a picture or a horse, when the servant bearing the basket was entrusted with what was to be enjoyed at night. We had never known men that took time to market, except as our hurried Northern fathers of families sometimes made sudden raids upon the butcher, on the way to business, and called off an order as they ran for a car.

The wide-terraced Canal Street, with its throng of leisurely promenaders, was our daily resort. The stands of Parma violets on the street corners perfumed the whole block, and the war seemed not even to have cast a cloud over the first foreign pleasure-loving people we had seen. The General was so pleased with the picturesque costumes of the servants that Eliza was put into a turban at his entreaty. In vain we tried for a glimpse of the creole beauties. The duenna that guarded them in their rare promenades, as they glided by, wearing gracefully the lace mantilla, bonnetless, and shaded by a French parasol, whisked the pretty things out of sight, quick as we were to discover and respectfully follow them. The effects of General Butler’s reign were still visible in the marvelous cleanliness of the city. We drove on the shell road, spent hours in the horse-cars, went to the theatres, and even penetrated the rooms of the most exclusive milliners, for General Custer liked the shops as much as I did. Indeed, we had a grand play-day, and were not in the least troubled at our detention.

General Scott was then in our hotel, about to set out for the North. He remembered Lieutenant Custer, who had reported to him in 1861, and was the bearer of despatches sent by him to the front, and he congratulated my husband on his career in terms that, coming from such a veteran, made his boy-heart leap for joy. General Scott was then very infirm, and, expressing a wish to see me, with old-time gallantry begged my husband to explain to me that he would be compelled to claim the privilege of sitting. But it was too much for his etiquettical instincts, and, weak as he was, he feebly drew his tall form to a half-standing position, leaning against the lounge as I entered. Pictures of General Scott, in my father’s home, belonged to my earliest recollections. He was a colossal figure on a fiery steed, whose prancing forefeet never touched the earth. The Mexican War had hung a halo about him, and my childish explanation of the clouds of dust that the artist sought to represent was the smoke of battle, in which I supposed the hero lived perpetually. And now this decrepit, tottering man — I was almost sorry to have seen him at all, except for the praise that he bestowed upon my husband, which, coming from so old a soldier, I deeply appreciated.

General Sheridan had assumed command of the Department of the Mississippi, and the Government had hired a beautiful mansion for headquarters, where he was at last living handsomely after all his rough campaigning. When we dined with him, we could but contrast the food prepared over a Virginia camp-fire, with the dainty French cookery of the old colored Mary, who served him afterward so many years. General Custer was, of course, glad to be under his chief again, and after dinner, while I was given over to some of the military family to entertain, the two men, sitting on the wide gallery, talked of what it was then believed would be a campaign across the border. I was left in complete ignorance, and did not even know that an army of 70,000 men was being organized under General Sheridan’s masterly hand. My husband read the Eastern papers to me, and took the liberty of reserving such articles as might prove incendiary in his family. If our incorrigible scamp spoke of the expected wealth he intended to acquire from the sacking of palaces and the spoils of churches, he was frowned upon, not only because the General tried to teach him that there were some subjects too sacred to be touched by his irreverent tongue, but because he did not wish my anxieties to be aroused by the prospect of another campaign. As much of my story must be of the hardships my husband endured, I have here lingered a little over the holiday that our journey and the detention in New Orleans gave him. I hardly think any one can recall a complaint of his in those fourteen years of tent-life; but he was taught, through deprivations, how to enjoy every moment of such days as that charming journey and city experience gave us.

The steamer chartered to take troops up the Red River was finally ready, and we sailed the last week in June. There were horses and Government freight on board. The captain was well named Greathouse, as he greeted us with hospitality and put his little steamer at our disposal. Besides the fact that this contract for transportation would line his pockets well, he really seemed glad to have us. He was a Yankee, and gave us his native State (Indiana) in copious and inexhaustible supplies, as his contribution to the talks on deck. Long residence in the South had not dimmed his patriotism; and in the rapid transits from deck to pilot-house, of this tall Hoosier, I almost saw the straps fastening down the trousers of Brother Jonathan, as well as the coat-tails cut from the American flag, so entirely did he personate in his figure our emblematic Uncle Sam. It is customary for the Government to defray the expenses of officers and soldiers when traveling under orders; but so much red-tape is involved that they often pay their own way at the time, and the quartermaster reimburses them at the journey’s end. The captain knew this, and thought he would give himself the pleasure of having us as his guests. Accordingly, he took the General one side, and imparted this very pleasing information. Even with the provident ones this would be a relief; while we had come on board almost wrecked in our finances by the theatre, the tempting flowers, the fascinating restaurants, and finally, a disastrous lingering one day in the beguiling shop of Madam Olympe, the reigning milliner. The General had bought some folly for me, in spite of the heroic protest that I made about its inappropriateness for Texas, and it left us just enough to pay for our food on our journey, provided we ordered nothing extra, and had no delays. Captain Greathouse little knew to what paupers he was extending his hospitality. No one can comprehend how carelessly and enjoyably army people can walk about with empty pockets, knowing that it is but a matter of thirty days’ waiting till Richard shall be himself again. My husband made haste to impart the news quietly to the staff, that the captain was going to invite them all to be his guests, and so relieve their anxiety about financial embarrassment. The scamp saw a chance for a joke, and when the captain again appeared he knew that he was going to receive the invitation, and anticipated it. In our presence he jingled the last twenty-six cents he had in the world against the knife in his almost empty pockets, assumed a Crœsus-like air, and begged to know the cost of the journey, as he loftily said he made it a rule always to pay in advance. At this, the General, unable to smother his laughter, precipitated himself out of the cabin-door, nearly over the narrow guard, to avoid having his merriment seen. When the captain said blandly that he was about to invite our party to partake of his hospitality, our scamp bowed, and accepted the courtesy as if it were condescension on his part, and proceeded to take possession, and almost command, of the steamer.

It was a curious trip, that journey up the Red River. We saw the dull brownish-red water from the clay bed and banks mingling with the clearer current of the Mississippi long before we entered the mouth of the Red River. We had a delightful journey; but I don’t know why, except that youth, health and buoyant spirits rise superior to everything. The river was ugliness itself. The tree trunks, far up, were gray and slimy with the late freshet, the hanging moss adding a dismal feature to the scene. The waters still covered the low, muddy banks strewn with fallen trees and underbrush. The river was very narrow in places, and in our way there were precursors of the Red River raft above. At one time, before Government work was begun, the raft extended forty-five miles beyond Shreveport, and closed the channel to steamers. Sometimes the pilot wound us round just such obstructions — logs and driftwood jammed in so firmly, and so immovable, they looked like solid ground, while rank vegetation sprung up through the thick moss that covered the decaying tree trunks. The river was very crooked. The whistle screeched when approaching a turn; but so sudden were some of these, that a steamer coming down, not slackening speed, almost ran into us at one sharp bend. It shaved our sides and set our boat a-quivering, while the vituperations of the boat’s crew, and the loud, angry voices of the captain and pilot, with a prompt return of such civilities from the other steamer, made us aware that emergencies brought forth a special and extensive set of invectives, reserved for careless navigation on the Red River of the South. We grew to have an increasing respect for the skill of the pilot, as he steered us around sharp turns, across low water filled with branching upturned tree trunks, and skillfully took a narrow path between the shore and a snag that menacingly ran its black point out of the water. A steamer in advance of us, carrying troops, had encountered a snag, while going at great speed, and the obstructing tree ran entirely through the boat, coming out at the pilot-house. The troops were unloaded and taken up afterward by another steamer. Sometimes the roots of great forest trees, swept down by a freshet, become imbedded in the river, and the whole length of the trunk is under water, swaying up and down, but not visible below the turbid surface. The forest is dense at some points, and we could see but a short distance as we made our circuitous, dangerous way.

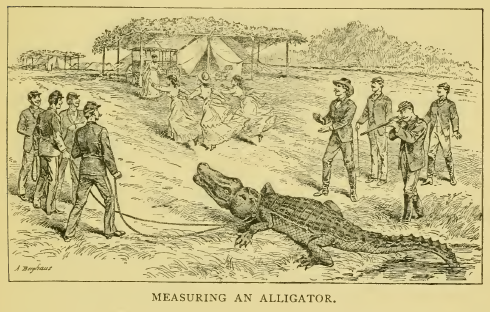

The sand-bars, and the soft red clay of the river-banks, were a fitting home for the alligators that lay sunning themselves, or sluggishly crawled into the stream as the General aimed at them with his rifle from the steamer’s guards. They were new game, and gave some fresh excitement to the long, idle days. He never gave up trying, in his determined way, for the vulnerable spot in their hide just behind the eye. I thought the sand-hill crane must have first acquired its tiresome habit of standing on one leg, from its disgust at letting down the reserve foot into such thick, noisome water. It seemed a pity that some of those shots from the steamer’s deck had not ended its melancholy existence. Through all this mournful river-way the guitar twanged, and the dense forest resounded to war choruses or old college glees that we sent out in happy notes as we sat on deck. I believe Captain Greathouse bade us good-by with regret, as he seemed to enjoy the jolly party, and when we landed at Alexandria he gave us a hogshead of ice, the last we were to see for a year.

A house abandoned by its owners, and used by General Banks for headquarters during the war, was selected for our temporary home. As we stepped upon the levee, a tall Southerner came toward me and extended his hand. At that time the citizens were not wont to welcome the Yankee in that manner. He had to tell me who he was, as unfortunately I had forgotten, and I began to realize the truth of the saying, that “there are but two hundred and fifty people in the world,” when I found an acquaintance in this isolated town. He proved to be the only Southerner I had ever known in my native town in Michigan, who came there when a lad to visit kinsfolk. In those days his long black hair, large dark eyes and languishing manner, added to the smooth, soft-flowing, flattering speeches, made sad havoc in our school-girl ranks. I suppose the youthful and probably susceptible hearts of our circle were all set fluttering, for the boy seemed to find pleasure in a chat with any one of us that fell to him in our walks to and from school. The captivating part of it all was the lines written on the pages of my arithmetic, otherwise so odious to me — “Come with me to my distant home, where, under soft Southern skies, we’ll breathe the odor of orange groves.” None of us had answered to his “Come,” possibly because of the infantile state of our existence, possibly because the invitation was too general. And here stood our youthful hero, worn prematurely old and shabby after his four years of fighting for “the cause.” The boasted “halls of his ancestors,” the same to which we had been so ardently invited, were a plain white cottage. No orange groves, but a few lime-trees sparsely scattered over the prescribed lawn. In the pleasant visit that we all had, there was discreet avoidance of the poetic license he had taken in early years, when describing his home under the southern sky.

Alexandria had been partly burned during the war, and was built up mostly with one-story cottages. Indeed, it was always the popular mode of building there. We found everything a hundred years behind the times. The houses of our mechanics at home had more conveniences and modern improvements. I suppose the retinue of servants before the war rendered the inhabitants indifferent to what we think absolutely necessary for comfort. The house we used as headquarters had large, lofty rooms separated by a wide hall, while in addition there were two wings. A family occupied one-half of the house, caring for it in the absence of the owners. In the six weeks we were there, we never saw them, and naturally concluded they were not filled with joy at our presence. The house was delightfully airy; but we took up the Southern custom of living on the gallery. The library was still intact, in spite of its having been headquarters for our army; and evidently the people had lived in what was considered luxury for the South in its former days, yet everything was primitive enough. This great house, filled as it once was with servants, had its sole water supply from two tanks or cisterns above ground at the rear. The rich and the poor were alike dependent upon these receptacles for water; and it was not a result of the war, for this was the only kind of reservoir provided, even in prosperous times. But one well was dug in Alexandria, as the water was brackish and impure. Each house, no matter how small, had cisterns, sometimes as high as the smaller cottages themselves. The water in those where we lived was very low, the tops were uncovered, and dust, leaves, bugs and flies were blown in, while the cats strolled around the upper rim during their midnight orchestral overtures. We found it necessary to husband the fast lowering water, as the rains were over for the summer. The servants were enjoined to draw out the home-made plug (there was not even a Yankee faucet) with the utmost care, while some one was to keep vigilant watch on a cow, very advanced in cunning, that used to come and hook at the plug till it was loosened and fell out. The sound of flowing water was our first warning of the precious wasting. No one could drink the river-water, and even in our ablutions we turned our eyes away as we poured the water from the pitcher into the bowl. Our rain-water was so full of gallinippers and pollywogs, that a glass stood by the plate untouched until the sediment and natural history united at the bottom, while heaven knows what a microscope, had we possessed one, would have revealed!

Eliza was well primed with stories of alligators by the negroes and soldiers, who loved to frighten her. One measuring thirteen feet eight inches was killed on the river-bank, they said, as he was about to partake of his favorite supper, a negro sleeping on the sand. It was enough for Eliza when she heard of this preference for those of her color, and she duly stampeded. She was not well up in the habits of animals, and having seen the alligators crawling over the mud of the river banks, she believed they were so constituted that at night they could take long tramps over the country. She used to assure me that she nightly heard them crawling around the house. One night, when some fearful sounds issued from the cavernous depths of the old cistern, she ran to one of the old negroes of the place, her carefully braided wool rising from her head in consternation, and called out, “Jest listen! jest listen!” The old mammy quieted her by, “Oh la, honey, don’t you be skeart; nothin’s goin’ to hurt you; them’s only bull-toads.” This information, though it quieted Eliza’s fears, did not make the cistern-water any more enjoyable to us.

The houses along Red River were raised from the ground on piles, as the soil was too soft and porous for cellars. Before the fences were destroyed and the place fell into dilapidation, there might have been a lattice around the base of the building, but now it was gone. Though this open space under the house gave vent for what air was stirring, it also offered free circulation to pigs, that ran grunting and squealing back and forth, and even the calves sought its grateful shelter from the sun and flies. And, oh, the mosquitoes! Others have exhausted adjectives in trying to describe them, and until I came to know those of the Missouri River at Fort Lincoln, Dakota, I joined in the general testimony, that the Red River of the South could not be outdone. The bayous about us, filled with decaying vegetable matter, and surrounded with marshy ground, and the frequent rapid fall of the river, leaving banks of mud, all bred mosquitoes, or gallinippers, as the darkies called them. Eliza took counsel as to the best mode of extermination, and brought old kettles with raw cotton into our room, from which proceeded such smudges and such odors as would soon have wilted a Northern mosquito; but it only resulted in making us feel like a piece of dried meat hanging in a smoke-house, while the undisturbed insect winged its way about our heads, singing as it swirled and dipped and plunged its javelin into our defenseless flesh. There were days there, as at Fort Lincoln, when the wind, blowing in a certain direction, brought such myriads of them that I was obliged to beat a retreat under the netting that enveloped the high, broad bed, which is a specialty of the extreme South, and with my book, writing or sewing, listened triumphantly to the clamoring army beating on the outside of the bars. The General made fun of me thus enthroned, when he returned from office work; but I used to reply that he could afford to remain unprotected, if the greedy creatures could draw their sustenance from his veins without leaving a sting.

At the rear of our house were two rows of negro quarters, which Eliza soon penetrated, and afterward begged me to visit. Only the very old and worthless servants remained. The owners of the place on which we were living had three other sugar plantations in the valley, from one of which alone 2,300 hogsheads of sugar were shipped in one season, and at the approach of the army 500 able-bodied negroes were sent into Texas. Eliza described the decamping of the owner of the plantation thus, “Oh, Miss Libbie, the war made a mighty scatter.” The poor creatures left were in desperate straits. One, a bed-ridden woman, having been a house-servant, was intelligent for one of her race. After Eliza had taken me the rounds, I piloted the General, and he found that, though the very old woman did not know her exact age, she could tell him of events that she remembered when she was in New Orleans with her mistress, which enabled him to calculate her years to be almost a hundred. Three old people claimed to remember “Washington’s war.” I look back to our visit to her little cabin, where we sat beside her bed, as one of vivid interest. The old woman knew little of the war, and no one had told her of the proclamation until our arrival. We were both much moved when, after asking us questions, she said to me, “And, Missey, is it really true that I is free?” Then she raised her eyes to heaven, and blessed the Lord for letting her live to see the day. The General, who had to expostulate with Eliza sometimes for her habit of feeding every one out of our supplies, whether needy or not, had no word to say now. Our kitchen could be full of grizzly, tottering old wrecks, and he only smiled on the generous dispenser of her master’s substance. Indeed, he had them fed all the time we stayed there, and they dragged their tattered caps from their old heads, and blessed him as we left, for what he had done, and for the food that he provided for them after we were gone.

It was at Alexandria that I first visited a negro prayer-meeting. As we sat on the gallery one evening, we heard the shouting and singing, and quietly crept round to the cabin where the exhorting and groaning were going on. My husband stood with uncovered head, reverencing their sincerity, and not a muscle of his face moved, though it was rather difficult to keep back a smile at the grotesqueness of the scene. The language and the absorbed manner in which these old slaves held communion with their Lord, as if He were there in person, and told Him in simple but powerful language their thanks that the day of Jubilee had come, that their lives had been spared to see freedom come to His people, made us sure that a faith that brought their Saviour down in their midst was superior to that of the more civilized, who send petitions to a throne that they themselves surround with clouds of doctrine and doubt. Though they were so poor and helpless, and seemingly without anything to inspire gratitude, evidently there were reasons in their own minds for heartfelt thanks, as there was no mistaking the genuineness of feeling when they sang:

Old as some of these people were, their religion took a very energetic form. They swayed back and forth as they sat about the dimly lighted cabin, clapped their hands spasmodically, and raised their eyes to heaven in moments of absorption. There were those among the younger people who jumped up and down as the “power” possessed them, and the very feeblest uttered groans, and quavered out the chorus of the old tunes, in place of the more active demonstrations for which their rheumatic old limbs now unfitted them. When, afterward, my husband read to me newspaper accounts of negro camp-meetings or prayer-meetings graphically written, no description seemed exaggerated to us; and he used to say that nothing compared with that night when we first listened to those serious, earnest old centenarians, whose feeble voices still quavered out a tune of gratitude, as, with bent forms and bowed heads, they stood leaning on their canes and crutches.

As the heat became more overpowering, I began to make excuses for the slip-shod manner of living of the Red River people. Active as was my temperament, climatic influences told, and I felt that I should have merited the denunciation of the antique woman in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” of “Heow shiftless!” It was hard to move about in the heat of the day, but at evening we all went for a ride. It seemed to me a land of enchantment. We had never known such luxuriance of vegetation. The valley of the river extended several miles inland, the foliage was varied and abundant, and the sunsets had deeper, richer colors than any at the North. The General, getting such constant pleasure out of nature, and not in the least minding to express it, was glad to hear even the prosaic one of our number, who rarely cared for color or scenery, go into raptures over the gorgeous orange and red of that Southern sky. We sometimes rode for miles along the country roads, between hedges of osage-orange on one side, and a double white rose on the other, growing fifteen feet high. The dew enhanced the fragrance, and a lavish profusion was displayed by nature in that valley, which was a constant delight to us. Sometimes my husband and I remained out very late, loth to come back to the prosy, uninteresting town, with its streets flecked with bits of cotton, evidences of the traffic of the world, as the levee was now piled up with bales ready for shipment. Once the staff crossed with us to the other side of the river, and rode out through more beautiful country roads, to what was still called Sherman Institute. General Sherman had been at the head of this military school before the war, but it was subsequently converted into a hospital. It was in a lonely and deserted district, and the great empty stone building, with its turreted corners and modern architecture, seemed utterly incongruous in the wild pine forest that surrounded it. We returned to the river, and visited two forts on the bank opposite Alexandria. They were built by a Confederate officer who used his Federal prisoners for workmen. The General took in at once the admirable situation selected, which commanded the river for many miles. He thoroughly appreciated, and endeavored carefully to explain to me, how cleverly the few materials at the disposal of the impoverished South had been utilized. The moat about the forts was the deepest our officers had ever seen. Closely as my husband studied the plan and formation, he said it would have added greatly to his appreciation, had he then known, what he afterward learned, that the Confederate engineer who planned this admirable fortification was one of his classmates at West Point, of whom he was very fond. In 1864 an immense expedition of our forces was sent up the Red River, to capture Shreveport and open up the great cotton districts of Texas. It was unsuccessful, and the retreat was rendered impossible by low water, while much damage was done to our fleet by the very Confederate forts we were now visiting. A dam was constructed near Alexandria, and the squadron was saved from capture or annihilation by this timely conception of a quick-witted Western man, Colonel Joseph Bailey. The dam was visible from the walls of the forts, where we climbed for a view.

As we resumed our ride to the steamer, the General, who was usually an admirable pathfinder, proposed a new and shorter road; and liking variety too much to wish to travel the same country twice over, all gladly assented. Everything went very well for a time. We were absorbed in talking, noting new scenes on the route, or, as was our custom when riding off from the public highway, we sang some chorus; and thus laughing, singing, joking, we galloped over the ground thoughtlessly into the very midst of serious danger. Apparently, nothing before us impeded our way. We knew very little of the nature of the soil in that country, but had become somewhat accustomed to the bayous that either start from the river or appear suddenly inland, quite disconnected from any stream. On that day we dashed heedlessly to the bank of a wide bayou that poured its waters into the Red River. Instead of thinking twice, and taking the precaution to follow its course farther up into the country, where the mud was dryer and the space to cross much narrower, we determined not to delay, and prepared to go over. The most venturesome dashed first on to this bit of dried slough, and though the crust swayed and sunk under the horses’ flying feet, it still seemed caked hard enough to bear every weight. There were seams and fissures in portions of the bayou, through which the moist mud oozed; but these were not sufficient warning to impetuous people. Another and another sprang over the undulating soil. Having reached the other side, they rode up and down the opposite bank shouting to us where they thought it the safest to cross, and of course interlarded their directions with good-natured scoffing about hesitation, timidity, and so on. The General, never second in anything when he could help it, remained behind to fortify my sinking heart and urge me to undertake the crossing with him. He reminded me how carefully Custis Lee had learned to follow and to trust to him, and he would doubtless plant his hoofs in the very tracks of his own horse. Another of our party tried to bolster up my courage, assuring me that if the heavy one among us was safely on the other bank, my light weight might be trusted. I dreaded making the party wait until we had gone further up the bayou, and might have mustered up the required pluck had I not met with trepidation on the part of my horse. His fine, delicate ears told me, as plainly as if he could speak, that I was asking a great deal of him. We had encountered quicksands together in the bed of a Virginia stream, and both horse and rider were recalling the fearful sensation when the animal’s hindlegs sank, leaving his body engulfed in the soil. With powerful struggles with his forefeet and muscular shoulders, we plunged to the right and left, and found at last firm soil on which to escape. With such a recollection still fresh, as memory is sure to retain terrors like that, it was hardly a wonder that we shrank from the next step. His trembling flanks shook as much as the unsteady hand that held his bridle. He quivered from head to foot, and held back. I urged, and patted his neck, while we both continued to shiver on the brink. The General laughed at the two cowards we really were, but still gave us time to get our courage up to the mark. The officer remaining with us continued to encourage me with assurances that there was “not an atom of danger,” and finally, with a bound, shouting out, “Look how well I shall go over!” sprang upon the vibrating crust. In an instant, with a crack like a pistol, the thin layer of solid mud broke, and down went the gay, handsomely caparisoned fellow, engulfed to his waist in the foul black crust. There was at once a commotion. With no ropes, it was hard to effect his release. His horse helped him most, struggling frantically for the bank, while the officers, having flung themselves off from their animals to rush to his rescue, brought poles and tree branches, which the imbedded man was not slow to grasp and drag himself from the perilous spot when only superhuman strength could deliver him, as the mud of a bayou sucks under its surface with great rapidity anything with which it comes in contact. As soon as the officer was dragged safely on to firm earth, a shout went up that rent the air with its merriment. Scarcely any one spoke while they labored to save the man’s life, but once he was out of peril, the rescuers felt their hour had come. They called out to him, in tones of derision, the vaunting air with which he said just before his engulfment, “Look at me; see how I go over!” He was indeed a sorry sight, plastered from head to foot with black mud. Frightened as I was — for the trembling had advanced to shivering, and my chattering teeth and breathless voice were past my control — I still felt that little internal tremor of laughter that somehow pervades one who has a sense of the ludicrous in very dangerous surroundings.

I had certainly made a very narrow escape, for it would have been doubly hard to extricate me. The riding habits in those days were very long, and loaded so with lead to keep them down in high winds — and, I may add, in furious riding — that it was about all I could do to lift my skirt when I put it on.

I held my horse with a snaffle, to get good, smooth going out of him, and my wrists became pretty strong; but in that slough I would have found them of little avail, I fear. There remained no opposition to seeking a narrower part of the bayou, above where I had made such an escape, and there was still another good result of this severe lesson after that: when we came to such ominous-looking soil, Custis Lee and his mistress were allowed all the shivering on the brink that their cowardice produced, while the party scattered to investigate the sort of foundation we were likely to find, before we attempted to plunge over a Louisiana quagmire.

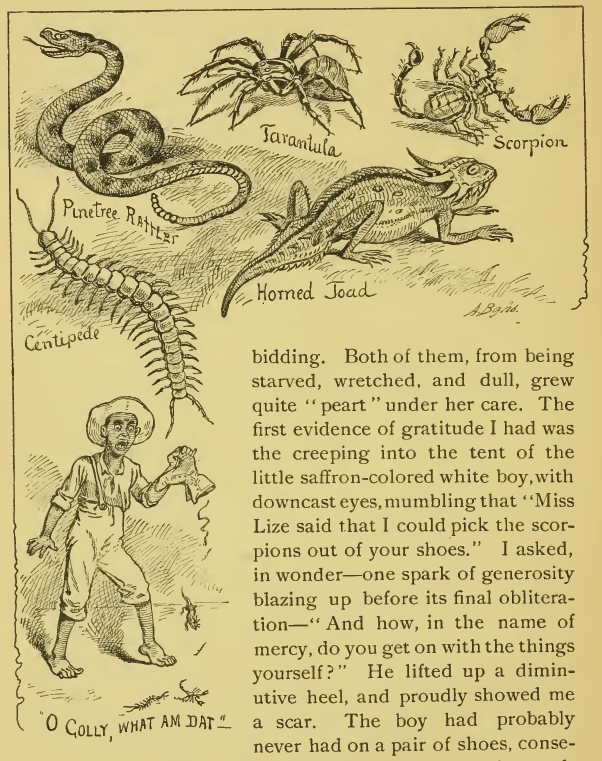

The bayous were a strange feature of that country. Often without inlet or outlet, a strip of water appeared, black and sluggish, filled with logs, snags, masses of underbrush and leaves. The banks, covered with weeds, noisome plants and rank tangled vegetation, seemed the dankest, darkest, most weird and mournful spots imaginable, a fit home for ghouls and bogies. There could be no more appropriate place for a sensational novelist to locate a murder. After a time I became accustomed to these frequently occurring water-ways, but it took me a good while to enjoy going fishing on them. The men were glad to vary their days by dropping a line in that vile water, and I could not escape their urging to go, though I was excused from fishing.