Heart of

Darkness

by

Joseph Conrad

"Heart of Darkness advances and

withdraws as in a succession of long dark waves borne by an incoming

tide. The waves encroach fairly evenly on the shore, and presently a

few more feet of sand have been won. But an occasional wave thrusts up

unexpectedly, much further than the others; even as far, say, as Kurtz

and his Inner Station"- Albert J. Guerard.

|

This electronic version of Heart of Darkness is a

scholarly edition. It includes links to vocabulary words, themes, and

other study information. The targeted audience for this project is high

school students or college freshmen reading the novel as part of an

English course. The text of the novel was taken from the web, and

although I thoroughly checked it, I cannot guarantee that it is one

hundred percent accurate.

The novel is divided up into three parts. To keep the

download time lower, I have put each chapter on a separate page. This

page is designed to run on a frames capable browser such as Netscape or

Internet Explorer. There is a no-frames option, however I recommend you

use the frames if possible. The screen is divided into two frames. The

larger top frame contains the text, while the lower small frame

contains footnotes such as definitions when links in the text are

followed. This allows you to keep your place in the text.

|

How

to use this site

When you click on one of the chapter links above, you

will be taken to a page with two frames, the larger top frame

will contain the text of the chapter you chose. Within the text

there are links which update the bottom frame. For example, if

you click on the underlined word "estuary" in the text,

the definition for estuary will appear in the bottom frame. The

links in the text will either be to definitions, themes, or

questions. Unless your browser is set to override the site

settings, un-followed links will be black and underlined, while

followed links will be gray and underlined. To return to the home

page, do not use the back button from your browser. At the bottom

of the top frame is a link to return home.

Within the text there are links to pages describing

some of the themes and structure of Heart of Darkness. While most

of themes can best be understood after reading the text, a few of

them are more helpful if read in advance. This page links to all

the theme pages: Themes

and

Structure of Heart of Darkness.

There is a page describing the life of Joseph Conrad: Life

of the Author

There are also pages for five of the more interesting

and symbolic characters in Heart of Darkness:

When you have finished reading the novel, there is a

page of questions that will help you study for possible essays on

Heart of Darkness: Questions

about the novel

Finally, there is a page listing outside resources for

studying and reading Heart of Darkness. They are somewhat listed

in order of relevance. There are several papers, lectures, web

sites, and a radio adaptation among them. A particularly good

resource is Professor Dintenfass' Freshman Lecture: Outside

links

In making this site, I used several resources:

- Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness: Complete,

Authoritative Text with Biographical and Historical Contexts, Critical

History and Essays from Five Contemporary Critical Perspectives, 2nd

ed. edited by Ross Murtin: Bedford Books of St. Martin's Press, NY

c.1996.

- Conrad the Novelist by Albert J. Guerard: Cambridge

Harvard University Press, c.1958.

- Heart of Darkness Cliff notes: Edited by Gary Carey,

c.1997

- Plus the sites listed in the outside links page.

All texts and images used belong to their

respective owners, and are reproduced here only for educational

purposes.

If you have any questions or comments

regarding this site, contact me, Coreen Csicseri, at: csicseri@acsu.buffalo.edu

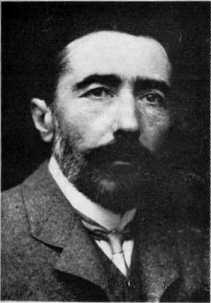

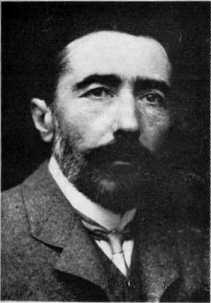

Life

of the Author

Joseph Conrad was born Teodor Jozef Konrad

Korzeniowski on December 3, 1857, the only child of a patriotic

Polish couple living in the southern Polish Ukraine. Conrad's

father was esteemed as a translator of Shakespeare, as well as a

poet and a man of letters in Poland, and Conrad's mother was a

gentle, well-born lady with a keen mind but frail health.

When Conrad was five, his father was arrested for

allegedly taking part in revolutionary plots against the Russians

and was exiled to Northern Russia; Conrad and his mother went

with him. His mother died from the hardships of prison life after

three years; she was only thirty-four.

Conrad's father sent him back to his mother's brother

for his education, and Conrad never saw him again. The

poet-patriot lived only four more years. Conrad was eleven years

old, but the emotional bond between him and his father was so

strong that a deep melancholy settled within the boy; much of his

writing as an adult is marked by a melancholy undercurrent.

Conrad received a good education in Cracow, Poland,

and after a trip through Italy and Switzerland, he decided not to

return to his father's homeland. Poland held no promise; already

Conrad had suffered too much from the country's Russian

landlords. Instead, the young lad decided on a career very

different from what one might expect of a boy brought up in

Poland; he chose the sea as his vocation.

Conrad reached Marseilles in October of 1874, when he

was seventeen, and for the next twenty years, he sailed almost

continually. Not surprisingly, most of his novels and short

stories have the sea as a background for the action ad as a

symbolic parallel for their heroes' inner turbulence. In fact,

most of Conrad's work concerns the sea. There is very little

old-fashioned romantic interest in his novels.

Part of this romantic void may be due to the fact that

while Conrad was in Marseilles and only seventeen, he had his

first love affair. I ended in disaster. For some time, Conrad

told people that he had been wounded in a duel, but now it seems

clear that he tried to commit suicide.

Conrad left Marseilles in April of 1878, when he was

twenty-one, and it was then that he first saw England. He knew no

English, but he signed on an English ship making voyages between

Lowestoft and Newcastle. It was on that ship that he began to

lean English.

At twenty-four, Conrad was made the first mate of a

ship that touched down in Singapore, and it was here that he

learned about an incident that would later contribute to the plot

of Lord Jim. Then,

four years later, while Conrad was aboard the Vidar,

he met Jim Lingard, the sailor who would become the physical

model for Lord Jim; in fact, all the men aboard the Vidar

called Jim "Lord Jim."

In 1886, when Conrad was twenty-nine, he became a

British subject, and in the same year, he wrote his first short

story, "The Black Mate." He submitted it to a literary

competition, but was unsuccessful. This failure, however, did not

stop him from continuing to write. During the next three years,

in order to fill empty, boring hours while he was at sea, Conrad

began his first novel, Almayer's Folly.

In addition, he continued writing diaries and journals when he

transferred onto a Congo River steamer the following year, taking

notes that would eventually become the basis for one of his

masterpieces, Heart of Darkness.

Conrad's health was weakened in Africa, and so he

returned to England to recover his strength. Then in 1894, when

Conrad was thirty-seven, he returned to sea; he also completed Almayer's

Folly. The novel appeared the following

year, and Conrad left the sea.He married Jessie George, a woman

seventeen years younger than he was. She was a woman with no

literary or intellectual interests, but Conrad continued to write

with intense, careful seriousness. Heart of

Darkness was first serialized in Blackwood's

Magazine; it appeared soon afterward as a

single volume, and Conrad then turned his time to Lord

Jim, his twelfth work of fiction.

After Lord Jim,

Conrad produced one major novel after another- Nostromo,

Typhoon, The Secret Agent, Under Western Eyes, Victory, and

Chance, perhaps his most

"popular" novel. He was no longer poor, and.

ironically, he was no longer superlatively productive. From 1911

until his death in 1924, he never wrote anything that equaled his

early works. His great work was done.

Personally, however, Conrad's life was full. He was

recognized widely, and he enjoyed dressing the part of a dandy;

it was something he had always enjoyed doing, and now he could

financially afford to. He played this role with great enthusiasm.

He was a short, tiny man and had a sharp Slavic face which he

accentuated with a short beard, and he was playing

"aristocrat," as it were. No one minded, for within

literary circles, Conrad was exactly that- a master.

When World War I broke out, Conrad was spending some

time in Poland with his wife and sons, and they barely escaped

imprisonment. Back in England, Conrad bean assembling his entire

body of work, which appeared in 1920, and immediately afterward,

he was offered a knighthood by the British government. He

declined, however, and continued to live without national honor,

but with literary honor instead. He suffered a heart attack in

August, 1924, and was buried at Canterbury.

Back

Home

This article was taken from

"Conrad's Heart of Darkness & Secret Sharer Cliff

Notes" c.1997

Themes

and Structure of Heart of Darkness

Throughout

the text there are links to most of these pages listed. The pages

describe some of the themes and structure present in the novel.

Some of these pages are more helpful if read before reading the

novel, and others will not make sense unless you read the novel

first. Here is a list of links to these pages:

Before reading Heart of Darkness:

Themes in

Heart of Darkness

Patterns in Heart of Darkness- Three's

- Three chapters

- Three times Marlow breaks the story

- Three stations

|

- Three women (Aunt, Mistress,

Intended)

- Three central characters (Kurtz,

Marlow, Narrator)

- Three views of Africa (adventure,

religious, economic)

|

Russian

Doll Effect

"To [Marlow] the meaning of an

episode was not inside like a kernel, but outside, enveloping the tale

which brought it out as a glow brings out a haze."

The structure of Heart of Darkness is much

like that of the Russian nesting dolls, where you open each doll up,

and there is another doll inside. Much of the meaning in Heart of

Darkness is found not in the center of the book, the heart of Africa,

but on the periphery of the book. In what happens to Marlow in

Brussels, what is happening on the Nellie as Marlow tells the story,

and what happens to the reader as they read the book.

In Heart of Darkness, we have an outside

narrator telling us a story he has heard from Marlow. The story Marlow

tells seems to center around a man named Kurtz. However, most of what

Marlow knows about Kurtz, he has learned from other people, many of

whom have good reason for not being truthful to Marlow. Therefore

Marlow has to piece together much of Kurtz’s story. We gradually get to

know very little more about Kurtz. What we do learn, is only through

interpreting his actions by what we think we already know. Part of the

meaning in Heart of Darkness is that we learn about "reality" through

other people's accounts of it, many of which are, themselves,

twice-told tales. Part of the meaning of the novel, too, is the

possibly unreliable nature of our teachers; Marlow is the source of our

story, but he is also a character within the story we read, and a

flawed one at that. Marlow's macho comments about women and his

insensitive reaction to the "dead negro" with a "bullet hole in his

forehead" cause us to refocus our critical attention, to shift it from

the story being retold, to the storyteller whose supposedly

autobiographical yarn is being repeated.

Contrast

in Heart of

Darkness

Much

of the imagery in

Heart of Darkness is arranged in patterns of opposition and

contrast.

Examples:

Light/dark

Black/white

Civilized/savage

Outer/inner

As you read the novel, be aware of how

Conrad uses this device. What does Conrad accomplish by this contrast,

especially of light and dark?

Themes in

Heart of Darkness

Symbolism of black and

white/ light and dark

Black/dark- death, evil, ignorance,

mystery, savagery, uncivilized

White/light- life, goodness,

enlightenment, civilized, religion.

This symbolism is not new, these

connotations have been present in society for centuries. We refer to

the Middle Ages, when science and knowledge was suppressed, as the Dark

Ages. According to Christianity, in the beginning of time all was dark

and God created light. According to Heart of Darkness, before the

Romans came, England was dark. In the same way, Africa was considered

to be in the "dark stage".

Yet, when it is looked into deeper, the

usual pattern is reverse and "darkness means truth, whiteness means

falsehood" This reversal tells a political truth about races in the

Congo, a psychological truth about Marlow and all of us (the truth

within, therefore dark and obscure), and any number of moral truths

(the trade in ivory is dark and dirty).

Themes in

Heart of Darkness

Like a knight of the Round Table, Marlow

sets off in search of strange adventures. He only gradually acquires a

grail, as he picks up more and more hints about Kurtz. Like a knight he

is frequently tested by signs he must confront, question and interpret.

Signs are things you see or experience or are told which have meaning

beyond the literal: old women knitting black wool might simply be

relatives of the company personnel given some position of respect and

usefulness, or the somber color of their wool and clothing, and their

serious demeanor, might suggest that they mind the gateway to a

mysterious underworld. You might take as signs the following:

- The Inner Station, with it's barrels of

unused rivet, its needless blasting of a cliff as a railroad is built,

its valley of death and shackled prisoners, and its gleaming

white-suited Accountant, who frets over his figures while a man lies

groaning his last in his office.

- The Central Station, rivetless and

strawless, where the manager smiled his mysterious mean smile and the

idle brickmaker (the "paper-mache Mephistopheles") drinks champagne and

lights his privileged candle in its silver holder, where a man is

dragged out a random and beaten for having set a fire (regardless of

whether he did), and where Marlow's boat is sunk (meanwhile, the

Eldorado expedition passes through- this section provides the most

detail of Marlow's increasing fascination with the enigmatic Kurtz.)

- The Russian's cabin, then the Russian

himself, a Shakespearean Fool with his motley clothes, his icon which

is dull text (language pored over reverently in spite of content), and

his ambivalent relationship with Kurtz.

- The "gateposts" which become heads on

poles, shrunken and dried and made to face Kurtz's house: signs not of

domestic order but of terror.

Even before he sets out, omens present

themselves to Marlow; old women knitting black wool in the Belgian

office, the phrenologist measuring Marlow's skull and warning of

changes to take place inside, the tale of how his predecessor died in

an uncharacteristic dispute over black hens.

After reading Heart of Darkness:

Themes in

Heart of Darkness

Civilization vs. Savagery

A major theme of Heart of Darkness is

civilization versus savagery. The book implies that civilizations are

created by the setting of laws and codes that encourage men to achieve

higher standards. It acts as a buffer to prevent men from reverting

back to their darker tendencies

Civilization, however, must be learned.

London itself, in the book a symbol of enlightenment, was once "one of

the darker places of the earth" before the Romans forced civilization

upon them.

While society seems to restrain these

savage tendencies, it does not get rid of them. These primeval

tendencies will always be like a black cloth lurking in the background.

The tendency to revert to savagery is seen

in Kurtz. When Marlow meets Kurtz, he finds a man that has totally

thrown off the restraints of civilization and has de-evolved into a

primitive state.

Marlow and Kurtz are two opposite examples

of the human condition. Kurtz represents what every man will become if

left to his own intrinsic desires without a protective, civilized

environment. Marlow represtens the civilized soul that has not been

drawn back into savagery by a dark, alienated jungle.

The book implies that every man has a heart

of darkness that is usually drowned out by the light of civilization.

However, when removed from civilized society, the raw evil of untamed

lifestyles within his soul will be unleashed.

The underlying theme of Heart of Darkness

is that civilization is superficial. The level of civilization is

related to the physical and moral environment they are presently in. It

is a much less stable or permanent state than society may think.

Themes in

Heart of Darkness

Views of the Wilderness

There are three basic views of the

African wilderness in Heart of Darkness:

- Some, like Marlow’s Aunt, see Africa

as full of savages that need to be saved. This view is demonstrated in

the famous poem White Man’s

Burden.

- To others, like the Belgians in the

Outer Station, Africa represents economic prospects such as free slave

labor and ivory. This is the underlying reasoning of colonialism.

- To those such as Marlow, Africa

represents a chance for adventure and self exploration.

Themes in

Heart of Darkness

Deception

Conrad recognized that deception is most

sinister when it becomes self-deception and the individual takes

seriously his own fictions. Kurtz "could get himself to believe

anything- anything." His benevolent words of his report for the

International Society for the Suppression of Savage customs was meant

sincerely enough, but a deeper sincerity spoke through his scrawled

postscript "Exterminate all the brutes!"

Themes in

Heart of Darkness

Protective Society

We are protected from ourselves by society

with its laws and watchful neighbors, Marlow observes. We are also

protected by work. "You wonder I didn’t go ashore for a howl and a

dance? Well, no- I didn’t. Fine sentiments, you say? Fine sentiments be

hanged! I had no time, I had to mess about with white-lead and strips

of woolen blanket helping to put bandages on those leaky steampipes"

But when the external restraints of society and work are removed we

must meet the challenge with our "own inborn strength. Principles won’t

do." This inborn strength appears to include restraint, the restraint

that Kurtz lacked and the cannibal crew of the Roi des Belges

surprisingly possessed. The hollow man, whose evil is the evil of

vacancy, succumbs. In their different degrees the pilgrims and Kurtz

share this hollowness. "Perhaps there was nothing within [the manager

of the Central Station]. Such a suspicion made one pause -- for out

there there were no external checks." And there was nothing inside the

Brickmaker, "but a little loose dirt, maybe." As for Kurtz, the

wilderness "It echoed loudly within him because he was hollow at the

core."

Themes in

Heart of Darkness

Self-Discovery

Heart of Darkness concerns Marlow (a

projection to whatever degree great or small of Conrad) and his journey

of self. Marlow reiterates often enough that he is recounting a

spiritual voyage of self-discovery. He remarks casually but crucially

that he did not know himself before setting out, and that he liked work

for the chance it provides to "find yourself in what no other man can

know." The Inner Station "was the farthest point of navigation and the

culminating point of my experience." At a superficial level, the

journey is a temptation to revert, a record of "remote kinship" with

the "wild and passionate uproar," of a "trace of a response" to it, of

a final rejection of the "fascination of the abomination." And why

should there not be a response? "The mind of man is capable of

anything- because everything is in it, all the past as well as all the

future." Marlow’s temptation is made concrete through his exposure to

Kurtz, a white man and sometime idealist who had fully responded to the

wilderness; a potential and fallen self. "I had turned to the

wilderness really, not to Mr. Kurtz." Marlow returns to Europe a

changed and more knowing man. Ordinary people are now "intruders whose

knowledge of life was to me an irritating pretense, because I felt so

sure they could not possibly know the things I knew."

Themes in

Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness as a Night Journey

Heart of Darkness explores something truer,

more fundamental, and distinctly less material than just a personal

narrative. It is a night journey into the unconscious, and

confrontation of an entity within the self. Certain circumstances of

Marlow’s voyage, looked at in these terms, take on a new importance.

The true night journey can occur only in sleep or in a waking dream of

a profoundly intuitive mind. Marlow insists on the dreamlike quality of

his narrative. "It seems to me I am trying to tell you a dream - making

a vain attempt, because no relation of a dream can convey the dream -

sensation." Even before leaving Brussels, Marlow felt as though he "was

about to set off for center of the earth," not the center of a

continent. The introspective voyager leaves his familiar rational

world, is "cut off from the comprehension" of his surroundings, his

steamer toils "along slowly on the edge of a black and incomprehensible

frenzy." As the crisis approaches, the dreamer and his ship moves

through a silence that "seemed unnatural, like a state of trance; then

enter a deep fog." The approach to this Kurtz grubbing for ivory in the

wretched bush was beset by as many dangers as though he had been an

enchanted princess sleeping in a fabulous castle." Later, Marlow’s task

is to try "to break the spell" of the wilderness that holds Kurtz

entranced.

Characters

Marlow

Charlie Marlow, thirty-two years old, has always

"followed the sea", as the novel puts it. His voyage up

the Congo river, however, is his first experience in freshwater

travel. Conrad uses Marlow as a narrator in order to enter the

story himself and tell it out of his own philosophical mind.

When Marlow arrives at the station he is shocked and

disgusted by the sight of wasted human life and ruined supplies .

The manager's senseless cruelty and foolishness overwhelm him

with anger and disgust. He longs to see Kurtz- a fabulously

successful ivory agent and hated by the company manager. More and

more, Marlow turns away from the white people (because of their

ruthless brutality) and to the dark jungle ( a symbol of reality

and truth.) He begins to identify more and more with Kurtz- long

before he even sees him or talks to him. In the end, the affinity

between the two men becomes a symbolic unity. Marlow and Kurtz

are the light and dark selves of a single person. Marlow is what

Kurtz might have been, and Kurtz is what Marlow might have

become.

Characters

Kurtz

Kurtz, like Marlow,originally came to the Congo with

noble intentions. He thought that each ivory station should stand

like a beacon light, offering a better way of life to the

natives. Kurtz mother was half-English and his father was

half-French. He was educated in England and speaks English. The

culture and civilization of Europe have contributed to the making

of Kurtz; he is an orator, writer, poet, musician, artist,

politician, ivory procurer, and chief agent of the ivory

company's Inner Station at Stanley Falls. In short, he is a

"universal genius"; however, he also described as a

"hollow man," a man without basic integrity or any

sense of social responsibility.

At the end of his descent into the lowest pit of

degradation, Kurtz is also a thief, murderer, raider, persecutor,

and to climax all his other shady practices, he allows himself to

be worshipped as a god. Marlow does not see Kurtz, however, until

Kurtz is so emaciated by disease that he looks more like a ruined

piece of a man than a whole human being.There is no trace of

Kurtz' former good looks nor his former good health. Marlow

remarks that Kurtz' head is as bald as an ivory ball and that he

resembles "an animated image of death carved out of old

ivory."

Kurtz wins control of men through fear and adoration.

His power over the natives almost destroys Marlow and the party

aboard the steamboat. Kurtz is the lusty, violent devil whom

Marlow describes at the beginning. He is contrasted with the

manager, who is weak and flabby- the weak and flabby devil also

described by Marlow. Kurtz is a victim of the manager's murderous

cruelty; stronger men than Kurtz would have found virtuous

behavior difficult under the manager's criminal neglect. It is

possible that Kurtz might never have revealed his evil nature if

he had not been cornered and tortured by the manager.

Characters

The Manager

This character, based upon a real person,

Camille Delcommne, is the ultimate villian of the plot. He is

directly or indirectly to blame for all the disorder, waste,

cruelty, and neglect that curses all three stations. He is in

charge of everything. Marlow suggests that the manager arranged

to wreck Marlow's steamboat in order to delay sending help to

Kurtz. He also deliberately prevents rivets from coming up the

coast to complete the steamboat's repairs.

At the manager's command, a native black

boy is beaten unmercifully for a fire which burnd up a shed full

of "trash." (The boy is probably innocent.) The

manager's conversation with his uncle reveals the full,

treacherous nature of both men. His physical appearance is

ordinary; his talents are few. Excellent health gives him an

advantage over other men. He seems to "have no

entrails" and has been in the Congo for nine years. His blue

eyes look remarkably cold, and his look can fall on a man

"like an axe-blow."

Characters

The Brickmaker

Despite his title, he is a man who seemingly makes no

bricks; instead, he acts as the manager's secretary, and he is

responsible for a good deal of the plot's entangling elements.

For example:

- He reveals the reason why the manager hates Marlow

- He shows Marlow the painting which Kurtz left at the

Central Station (one of the important symbols of the book).

- He reveals the reason why the manager hates Kurtz

- He unwillingly and indirectly lets Marlow know that the

delay in getting rivets is intentional

- He lets Marlow know that the white men at the Central

Station identify Marlow with Kurtz, as members of the "new gang of

virtue."

Characters

The Accountant

He is the keeper of all the company books; he gives

Marlow his first information about Kurtz, and he also reveals the

general hatred which the white men bear toward the blacks. In

addition, he confides his conviction that there is shady business

at the Central Station.

Questions

Here are some questions to ask yourself after reading

the novel:

- Why are most of the novel's characters given only

descriptive titles, and not actual names? (ex. brickmaker, accountant)

- Why is the framing narrator unnamed?

- What do the three women in the novel represent?

(Marlow's Aunt, Kurtz Intended, and his Mistress) What does Marlow mean

in Chapter 1 when he says that women are "out of touch with truth" and

live in a beautiful world of their own?

- What does it mean to have a "choice of nightmares"

(Chapter 3)?

- What is "the horror" (Chapter 3)?

- In chapter 1, Marlow states, "You know I hate, detest,

and can't bear a lie, not because I am straighter than the rest of us,

but simply because it appalls me. There is a taint of death, a flavor

of mortality in lies which is exactly what I hate and detest in the

world." Yet in Chapter 3, he lies to Kurtz' Intended. Why do you think

that is?

- Early in Chapter 1, Marlow says, "The conquest of the

earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a

different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a

pretty thing when you look into it too much. What redeems it is the

idea only...something you can set up, and bow down before, and offer a

sacrifice to." What do you think he means by this? Is this passage a

criticism of colonialism in general?

- Conrad uses the term "nigger" in Heart of Darkness. Do

you feel that Conrad is being racist in these remarks? Why or why not?

- What does Marlow think of the futility and waste that

goes on in the Company? Give some examples.

- Often throughout the novel, when Marlow describes a

black object or person, he then points out something light or white

about it. For example, in chapter 1 he describes one of the workers at

the Outer Station saying, "It looked startling round his black neck,

this bit of white thread." What does Conrad accomplish by this

contrast, what is he trying to express?

- The unnamed narrator breaks the story only a few times.

Why do you think he broke the story where he did?

- Early in Chapter 3, Marlow describes Kurtz' house and

the gateposts around it. He is startled by the shrunken heads atop the

posts that are turned toward the house. He remarks that they would be

more impressive if turned outward. Why did Kurtz have them turned

towards the house?

- Near the end of Chapter 3, Marlow, talking about Kurtz

states, "True, he had made that last stride, he had stepped over the

edge, while I had been permitted to draw back my hesitating foot." To

what is he referring?