"The boundaries of Louisiana are towards east Florida and Carolina, towards north Virginia and Canada. The northern limits are entirely unknown. In 1700, a Canadian, M. le Sieur, ascended the Mississippi over 700 miles. But there is still another district known of over 100 miles, for which reason it is almost to be supposed that this country extends to the 'Polum Arcticum.'"

The soil, the author says, is "extremely pleasant." Four crops a year can be raised. The abundance of the country cannot be easily imagined. There is also game, which every person is permitted to kill: leopards, bears, buffaloes, deer, whole swarms of Indian hens, snipe, turtle-doves, partridges, wood-pigeons, quail, beavers, martens, wild cats, parrots, buzzards, and ducks. Deer is the most useful game, and the French carry on a great "negotium" in doeskins, which they purchase from the savages. Ten to twelve leaden bullets are given in exchange for such a skin.

The principal things, however, are the mines:

"The land is filled with gold, silver, copper, and lead mines. If one wishes to hunt for mines, he need only go into the country of the Natchitoches. There we will surely 'draw pieces of silver mines out of the earth.' After these mines we will hunt for herbs and plants for the apothecaries. The savages will make them known to us. Soon we shall find healing remedies for the most dangerous wounds, yes, also, so they say, infallible ones for the fruits of love."

Of the spring floods in "Februario and Martio" the author says that they are sometimes so high that the water rises over 100 feet, so that the tops of the pine trees on the seashore can no longer be seen.

About New Orleans a man writes to his wife in Europe:

"I betook myself to where they are beginning now to build the capital. New Orleans. Its circumference will be one mile. The houses are poor and low, as at home with us in the country. They are covered with large pieces of bark and strong reeds. Everybody dresses as he pleases, but all very poorly. One's outfit consists of a suit of clothes, bed, table, and trunks. Tapestry and fine beds are entirely unknown. The people sleep the whole night in the open air. I am as safe in the most distant part of the town as in a citadel. Although I live among savages and Frenchmen, I am in bo danger. People trust one another so much that they leave gates and doors open."

The productiveness of the investment in land, and the value of the shares are thus made clear to the people:

"If one gets 300 acres of land for 100 Reichstalers, then three acres cost one Taler; but, if the benefit to be derived and other 'prerogatives' of such lands are considered then an acre of this land, even if not cultivated, is worth about roc Talers. From this basis it follows that 300 acres, which, as stated already, cost 100 Talers when purchased, are really worth 30,000 Talers. For this reason one can easily understand why these shares may yet rise very high."

No wonder that the agitation on both banks of the river Rhine, from Switzerland to Holland, bore fruit, and that thousands of people got themselves ready to emigrate to Louisiana.

Ten Thousand Germans on the Way to Louisiana.

German historians state that, as a result of this agitation, 10,000 Germans emigrated to Louisiana. This seems a rather large number of people to be enticed by the promoter's promises to leave their fatherland and emigrate to a distant country; but we must consider the pitiable condition under which these people lived at home. No part of Germany had-suffered more through the terrible "Thirty Years' War" (1618-1648), than the country on the Rhine, and especially the Palatinate; and after the Thirty Years' War came the terrible period of Louis XIV., during which large portions of Alsace and Lorraine, with the city of Strass-burg, were forcibly and against the protestations of the people taken away from the German empire, and the Palatinate particularly was devastated in the most terrible manner. Never before nor afterwards were such barbarous deeds perpetrated as by Turenne, Melac, and other French generals in the Palatinate; and whether French troops invaded Germany or Germans marched against the French, it was always the Palatinate and the other countries on both banks of the Rhine that suffered most through war and its fearful consequences; pestilence, famine, and often also religious persecution,—for the ruler of a country then often prescribed which religion his subjects must follow.

These people on the Rhine had at last lost courage, and, as

in 1709/10, at the time of the great famine, 15,000 inhabitants of the Palatinate had Hstened to the EngHsh agents and had gone down the Rhine to England to seek passage for the English colonies in America, so they were again only too eager to listen to the Louisiana promoter, promising them peace, political and religious freedom, and wealth in the new world. So they went forth, not only from the Palatinate, but also from Alsace, Lorraine, Baden, Wiirtemberg, the electorates of Mayence and Treves (Mainz and Trier), and even from Switzerland, some of whose sons were already serving in the Swiss regiments of Halwyl and Karer, sent by France to Louisiana.

The statement that 10,000 Germans left their homes for Louisiana is also supported by unimpeachable French testimony. The Jesuit Charlevoix, who came from Canada to Louisiana in December, 1721, and passed "the mournful wrecks" of the settlement on John Law's grant on the Arkansas River, mentions in his letter "these 9,000 Germans, who were raised in the Palatinate."

How Many of These 10,000 Germans Reached Louisiana?

Only a small portion of these 10,000 Germans ever reached the shores of Louisiana. We read that the roads leading to the French ports of embarkation were covered with Germans, but that many broke down on their journey from hardships and privations. In the French ports, moreover, where no preparations had been made for the care of so many strangers, and where, while waiting for the departure of the vessels, the emigrants lay crowded together for months, and were insufficiently fed, epidemic diseases broke out among them and carried ofif many. Indeed, the church registers of Louisiana contain proofs of this fact. In the old marriage records, which always give the names of the parents of the contracting parties, the writer has often found the remark that the parents of the bride or of the bridegroom had died in the French ports of L'Orient, La Rochelle, or Brest. Others tired of waiting in port, and, perhaps,

becoming discouraged, gave up the plan of emigrating to Louisiana, looked for work in France, and remained there.

Then came the great loss of human life on the voyage across the sea. Such a voyage often lasted several months, long stops often being made in San Domingo, vi^here the people virere exposed to infection from tropical diseases. When even strong and healthy people succumbed to diseases brought on by the privations and hardships of such a voyage, by the miserable fare, by the lack of drinking water and disinfectants, and by the terrible odors in the ship's hold,—how must these emigrants have fared, weakened as they were from their journey through France and from sickness in the French ports? At one time only forty Germans landed in Louisiana of 200 who had gone on board. Martin speaks of 200 Germans who landed out of 1200.

Sickness and starvation, however, were not the only dangers of the emigrant of those days. At that time the buccaneers, who had been driven from Yucatan by the Spaniards in 1717, were yet in the Gulf of Mexico, and pursued European vessels because these, in addition to emigrants, usually carried large quantities of provisions, arms, ammunition, and money; and many a vessel that plied between France and Louisiana was never heard of again. In 1721 a French ship with "300 very sick Germans" on board was captured by buccaneers near the Bay of Samana in San Domingo.

After considering all this we are ready to approach the question of how many Germans really left France for Louisiana. Chevalier Guy Soniat Dufifosat, a French naval officer who settled in Louisiana about 1751, in his "Synopsis of the History of Louisiana" (page 15) says, that 6000 Germans left Europe for Louisiana. This statement, if not correct, comes evidently so near to the truth that we may accept it.

To this it may be added that according to my own searching inquiries, and after the examination of all the well-known authorities, as well as of copies of many official documents until recently imavailable, I have come to the conclusion that of those 6000 Germans who left Europe for Louisiana, only about one-third—

2000—actually reached the shores of the colony. By this I do not mean to say that 2000 Germans settled in Louisiana, but only that 2000 reached the shores and were disembarked in Biloxi and upon Dauphine Island, in the harbor of Mobile. How many of them perished in those two places will be told in another part of this work.

French Colonists.

Besides John Law, who enlisted Germans, the Western Company and the other concessioners also carried on an agitation for the enlistment of engages. How this was done, and what results were obtained with the French colonists, is described by the Jesuit Charlevoix, an eye witness, who came to Louisiana in 1721 to report on the condition of the colony. He says:

"The people who are sent there are miserable wretches driven from France for real or supposed crimes, or bad conduct, or persons who have enlisted in the troops or enrolled as emigrants, in order to avoid the pursuit of their creditors. Both classes regard the country as a place of exile. Everything disheartens them; nothing interests them in the progress of a colony of which they are only members in spite of themselves." (Marbois, page 115.)

The Chevalier Champigny in his Memoire (La Haye, 1776) expresses himself stronger:

"They gathered up the poor, mendicants and prostitutes, and embarked them by force on the transports. On arriving in Louisiana they were married and had lands assigned to them to cultivate, but the idle life of three-fourths of these folks rendered them unfit for farming. You cannot find twenty of these vagabond families in Louisiana now. Most of them died in misery or returned to France, bringing back such ideas which their ill success had inspired. The most frightful accounts of the country of the Mississippi soon began to spread among the public, at a time when German colonists were planting new and most successful establishments on the banks of the Mississippi, within five or seven leagues from New Orleans. This tract, still occupied by their descendants, is the best cultivated and most thickly settled part of the colony, and I regard the Germans and the Canadians as the founders of all our establishments in Louisiana."

Franz, in his "Kolonisation des Mississippitales" (Leipzig, 1906), writes:

"The company even kept a whole regiment of archers (band-ouillers de Mississippi) which cleaned Paris of its rabble and adventurers, and received for this a fixed salary and 100 livres a head, and even honest people were not safe from them. Five thousand people are said to have disappeared from Paris in April, 1721, alone." (Page 124.)

And again:

"Prisoners were set free in Paris in September, 1719, and

later, under the condition that they would marry prostitutes and

go with them to Louisiana. The newly married couples were

chained together and thus dragged to the port of embarkation." (Page 121.)

The complaints of the concessioners and of the company itself concerning this class of French immigrants and engages were soon so frequent and so pressing, that the French government, in May, 1720, prohibited such deportations. This, however, did not prevent the shipping of a third lot of lewd women in 1721, the first and the second having been sent in 1719 and 1720.

Arrival of the First Immigration en Masse.

The first immigration en masse took place in the year 1718. There landed then in Louisiana, which at that time had only 700 inhabitants, on one day 800 persons, so that the population on that one day was more than doubled.

How many Germans were among these I cannot say; but, as several concessions are mentioned to which some of these immigrants were sent, and as the church registers of Louisiana mention names of Germans who served on these concessions, we may assume that there were some Germans among them.

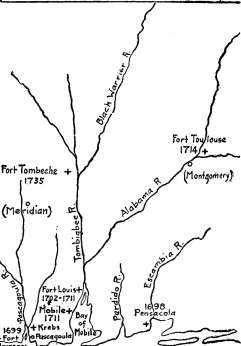

In the spring and summer of 1719 immigration to Louisiana was suspended on account of the war which had broken out between France and Spain. The Louisiana troops took Pensacola from Spain, lost it again, and retook it. In front of Dauphine Island, in the harbor of Mobile, where there were some concessioners with their engages, a Spanish flotilla appeared, shutting off the island for ten days. The crew of a

Spanish gunboat plundered the property of the concessioners lying on the shore, but were repulsed in a second attempt by the French solders, some Indians, and the people engaged by the concessioners.

In the fall of 1719 the French ship "Les Deux Freres" came to Ship Island with "a great number of Germans." The ship was laden with all sorts of merchandise and effects "which belonged to them." These people could not have been intended for John Law; for, judging from what they brought along with them, they must have been people of some means, who intended to become independent settlers.

A Misstatement.

This report is taken from "Relation Penicaut." Penicaut was a French carpenter who lived for twenty-two years (1699 to October, 1721) in the colony, and his "Relation" is an important source for the history of Louisiana. Mr. French, whose "Historical Collection of Louisiana" is well known, translated it and published it in the first volume of his "Louisiana and Florida." In this translation (N. Y., 1889, I., 151) we read concerning the German immigrants of the ship "Les Deux Freres," mentioned before, the following:

"This was the first installment of twelve thousand Germans purchased by the Western Company from one of the princes of Germany to colonize Louisiana."

This is not true. For in the first place, the original text of "Relation Penicaut" which Margry printed in his volume V. does not contain a single word about an installment nor about a German prince who had sold his subjects to the Western Company; and secondly, people who come "with all sorts of merchandise and effects, which belong to them," are not people who have been sold.

In November, 1719, when the headquarters of the company were no longer on Dauphine Island, in the harbor of Mobile,* but had been again transferred to Fort Maurepas (Ocean

'A sand bar formed by a storm in 1717 having ruined the entrance to that harbor.

Springs), a part of this fort was burned,^ whereupon the woods on the other side of the Biloxi Bay were cut down, and Dumont reports that "a company of stout German soldiers" were busy at that work. Whence these German soldiers came we are informed by the "Memoire pour Duverge" (Margry V., 6i6), where it is stated that a company of 210 Swiss "soldats ouv-riers" had been sent to the colony. They cleared the land at the site of the present Biloxi, built a fort, houses, and barracks for officers and soldiers, magazines, and "even a cistern." This place was called "New Biloxi," and thither the Compagnie des Indes, on the 20th of December, 1720, decided to transfer its headquarters. Governor Bienville also took up his residence there on the 9th of September, 1721, but transferred it to New Orleans in the month of August, 1722.

From this time until the beginning of the Spanish period, in 1768, the Swiss formed an integral part of the French troops in Louisiana. There were always at least four companies of fifty men each in the colony. They regularly received new additions, and, at the expiration of their time of service, they usually took up a trade, or settled on some land contiguous to the German coast. It was even a rule to give annually land, provisions, and rations to two men from each Swiss company to facilitate their settling.

According to the church records of Louisiana (marriage and death registers), the great majority of these Swiss soldiers were Germans from all parts of the fatherland under Swiss or Alsatian officers. Of the latter, Philip Grondel, of Zabern, became celebrated as the greatest fighter and most feared duellist of the whole colony. He was made chevalier of the military order of St. Louis, and commander of the Halwyl regiment of Swiss soldiers.

As to the general reputation these Swiss-German soldiers established for themselves in Louisiana, it is interesting to read that

"Governor Kerlerec even begged that Swiss troops be sent to him in place of the French, not only on account of their superior

^ A drunken sergeant dropping his lighted pipe had set fire to it.

discipline and fighting qualities, but because the colonists had as great a dread of the violence, cruelty, and debauchery of the troops ordinarily sent out from France as they had of the savages." (Albert Phelps' "Louisiana," page 95.)

In the beginning of the year 1720, says Penicaut, seven ships came with more than 4000 persons, "French as well as Germans and Jews." They were the ships "La Gironde," "L'Elephant," "La Loire," "La Seine," "Le Dromadaire," "La Traversier," and "La Venus." As "Le Dromadaire" brought the whole outfit for John Law's concession, the staff of Mr. Elias,® the Jewish business manager of Law, may have been on board this vessel. For the same reason we may assume that the German people on board, or at least a large part of them, were so-called "Law People."

On the i6th of September, 1720, the ship "Le Profond" brought more than 240 Germans "for the concession of Mr. Law," '' and on the 9th of November, 1720, the ship "La Marie" brought Mr. Levens, the second director of Law's concessions, and Mr. Maynard, "conducteur d'ouvriers."

The Germans who came on the seven ships mentioned by Penicaut and those who arrived on board the "Le Profond" seem to have been the only ones of the thousands recruited for Law in Germany who actually reached the Arkansas River, traveling from Biloxi by way of the inland route—Lake Borgne, Lake Pontchartrain, Lake Maurepas, Amite River, Bayou Manchac and the Mississippi River.

How THE Immigrants Were Received and Provided for. A Terrible State of Affairs.

A rapid increase of the population, especially a doubling of it on one day, would at all times, even in a well regulated community, be a source of embarrassment; and it would need the most careful preparations and the purchasing and storing of a great quantity of provisions in order to solve the problem of subsistence in a satisfactory manner.

'Terrage calls him "Elias Stultheus". 'La Harpe.

On Dauphine Island and on Biloxi Bay, nevertheless, where the officials of the Compagnie des Indes ruled, nothing was done for the reception of so many newcomers. Everybody seems to have lived there like unto the lilies of the field: "They toiled not, neither did they spin." Nobody sowed, nobody harvested, and all waited for the provision ships from France and from San Domingo, which often enough did not arrive when needed most, so that the soldiers had to be sent out to the Indians in the woods to make a living there as best they could by fishing and hunting. Penicaut says that the Indians, especially the Indian maidens, enjoyed these visits of the soldiers as much as the French did. This statement seems to be confirmed by the baptismal records of Mobile, where the writer found entries saying that Indian women "in the pains of childbirth" gave the names of the officers and soldiers whom they claimed as the fathers of their children. There are prominent names among these fathers.

Thus the poor immigrants were put on land where there was always more or less of famine, sometimes even of starvation, and where the provisions which the concessioners had brought with them to feed their own engages were taken away from the ships by force to feed the soldiers, and the immigrants were told to subsist on what they might be able to catch on the beach, standing for the most part of the day in the salt water up to the waist—crabs, oysters, and the like—and on the corn which the Biloxi, the Pascagoula, the Chacta, and the Mobile Indians might let them have.

Governor Bienville repeatedly demanded that these immigrants should not be landed on the gulf coast at all, but should be taken up the Mississippi River to the place where he intended to esablish his headquarters and build the city of New Orleans; because thence they could easily reach the concessions, a majority of which were on the banks of the Mississippi. But the question whether large vessels could enter and ascend the great river—the French directors pretended not to know this yet, although the colony had been in existence for about twenty years—and the little and the big quarrels between the directors

and the governor, whom they would never admit to be right, did not permit this rational solution of the difficulty.

Furthermore, as a very large number of smaller boats, by which the immigrants might easily have been taken to the concessions by the inland route through Lake Pontchartrain, had been allowed to go to wreck on the sands of Biloxi, the newcomers, especially those who arrived in 1721, had to stay for many months in Biloxi and on Dauphine Island, where they starved in masses or died of epidemic diseases.

It may be taken for granted that at these two places more than one thousand Germans died.

"Many died," says Dumond, "because in their hunger they ate plants which they did not know and which instead of giving them strength and nourishment, gave them death, and most of those who were found dead among the piles of oyster shells were Germans."

In the spring of 1721 such a fearful epidemic raged in Biloxi among the immigrants that the priests at that place, having so many other functions to perform, were no longer able to keep the death register. (See "Etat Civil" for 1727, where a Capuchin priest records the death of a victim of the epidemic of 1721, in Biloxi, on the strength of testimony of witnesses, no other way of certifying to the death being possible.)

Thus, for many months, the effects of the concessioners and of the immigrants were exposed to the elements on the sand of the beach. Even the equipment for Law's concession, which had arrived in the beginning of 1720, a cargo valued at a million of livres, lay in the open air in Biloxi for fifteen months, before the ship "Le Dromadaire," in May, 1721, at the order of the governor, but against the protests of some of the directors of the company, sailed with it for the mouth of the Mississippi.

This ship, with its load, drew thirteen feet of water and, as the "Neptune," also drawing thirteen feet, had crossed the bar of the Mississippi and sailed up to the site of New Orleans as early as 1718, and as an English vessel carrying 16 guns had passed up to English Turn in September, 1699, there was no reason whatsoever for detaining "Le Dromadaire" for fifteen

months. A proper use of the "Neptune" alone, which had been stationed permanently in the colony since 1718, would have relieved the congestion in Biloxi and saved thousands of human lives which were sacrificed by the criminal neglect of the officials of the Compagnie des Indes.

As "Le Dromadaire" carried the oufit for the Law concession and for the plantation of St. Catharine, this ship may also have had some passengers on board, German engages, so-called Law people; but perhaps not very many, as Bienville, in sending her to the Mississippi against the protests of some of the directors of the company, took a great responsibility upon himself, and could not afford to load her too heavily, lest there should be trouble in getting her over the bar of the river. The larger number of the German Law people, those who had arrived during the year 1720, had, no doubt, been sent to the Arkansas River by the inland route to clear the land and provide shelter for the great number of Germans who were expected to arrive in the spring of 1721.

No wonder that under such conditions as obtained in Biloxi a very low state of law and order reigned there, and that complete anarchy could be prevented only by drastic measures. A company of Swiss soldiers in the absence of their commander forced the captain of a ship to turn his vessel and to take them to Havana; and another company marched ofif to join the English in Carolina. The Swiss in Fort Toulouse, above Mobile, also rose and killed their captain; but these mutineers were captured and punished in Indian fashion by crushing their heads; one Swiss was packed into a barrel which was then sawed in two, and a German who had helped himself to something to eat in the warehouse in Biloxi was condemned by the Superior Council to be pulled five times through the water under the keel of a vessel.

But punishment which was meted out so severely to the small pilferer did not reach the guilty ones in high positions. Though the Germans on the other side of the bay died by the hundreds from starvation, Hubert, the commissioner general,

who, as an investigation proved, had not kept any books during the whole tenure of his office, did not even know that there was a shipload of provisions in the hull of a vessel stranded near Ocean Springs and left there for eleven months. Yet Hubert was not punished.

Even this description, perhaps, does not give the whole truth, as contemporary writers did not dare to say what they knew. Dupratz says (I. 166) :

"So delicate a matter is it to give utterance to the truth that the pen often falls from the hands of those who are most disposed to be accurate."

Germans in Pascagoula.

In January, 1721, 300 engages came to the concession of Madame Chaumont in Pascagoula. There were no Germans among them, as the census of 1725 shows, but Pensacola must be mentioned here, as there was a German colony at that place very early, arising, perhaps, on the ruins of this concession or of some other enterprise. The date of the founding of that German settlement is not known; but, in 1772, the English captain Ross found there, on the farm of "Krebs," cotton growing and a roller cotton gin, the invention of Krebs, and, perhaps, the first successful cotton gin in America.*

In the same year (1772) we hear of a great storm which raged most furiously "on the farm of Krebs and among the Germans of Pascagoula."

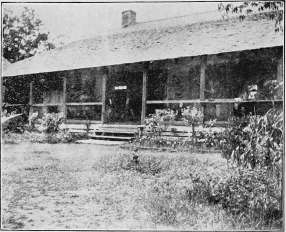

His last will and testament, written in New Orleans in the Spanish language in 1776, gives his full name as "Hugo Ernestus Krebs." He was from Neumagen on the Moselle, Germany, and left fourteen grown children, whose descendants still own the old Krebs farm, which the author visited in August, 1906. It is situated on a slight elevation on the border of "Krebs' Lake," near the mouth of the Pascagoula River, and a mile and a half north of the railroad station of Scranton (now incorporated with East Pascagoula), Mississippi.

* Cotton was planted in Louisiana much earlier. Charlevoix saw some in a garden in Natchez in 1721; and Dupratz constructed a machine for extracting the seed; but his machine was a failure.

The Creoles there call the Krebs home "the old fort," and the three front rooms forming the center of the house, the rest consisting of more recent additions, were evidently built with a view of affording protection against the Indians. The walls of this part of the house are eighteen inches thick, the masonry-consists of a very hard concrete of lime, unbroken large oyster shells, and clay. The post and sills are of heavy cypress, which, after serving at least 175 years, do not show any signs of decay. The floor is made of concrete similar to that of the walls, but a wooden floor has been laid upon it, taking away about eighteen inches from the original height of the rooms. All the wood work was hewn with the broad axe.

In front of the house lies an old mill stone which once upon a time served to crush the corn.

Near the house is the "Krebs Cemetery," with the tombs of the members of the Krebs family, of whom a great number are buried there. The accompanying pictures were taken on the spot.

According to the family traditions the old fort was built by "Commodore de la Pointe," who is said to have been a brother of Madame Chaumont. Hamilton, in his "Colonial Mobile," page 140, says that Joseph Simon de la Pointe received, on the i2th of November, 1715, from Governor Cadillac, a land concession on Dauphine Island for the purpose of enabling him to raise cattle. As Dauphine Island was practically abandoned, after the great storm of 1717, de la Pointe probably also gave up his concession, and a map, drawn about 1732 ("Colonial Mobile," page 86) shows "Habitation du Sieur Lapointe"®) on the very spot where the Krebs homestead now stands, near the mouth of the Pascagoula River.

La Pointe's daughter, Marie Simon de la Pointe, became the first wife of Hugo Ernestus Krebs. Thus the old fort came into possession of the Krebs family, where it still remains, the present owner and occupant being Mrs. J. T. Johnson, nee Cecile Krebs, an amiable and highly intelligent lady to whom

' Every concessioner was given the title of "Sieur".

KREBS CEMETERY.

KREBS CEMETERY.

the author's thanks are due. She is the great grand-daughter of Joseph Simon Krebs, the eldest son of Hugo Ernestus Krebs and Marie Simon de la Pointe.

Francesco Krebs, the second son of Hugo Ernestus Krebs and Marie Simon de la Pointe, received Round Island in the Bay of Pascagoula, containing about no acres of land, as a grant from the Spanish government, on the 13th of December, 1783, after having occupied it for many years. The family of his wife had received permission to settle there from the French governor Bienville, who left Louisiana in May, 1743.

Pest Ships.

On the 3d of February, 1721, the ship "La Mutine" arrived at Ship Island with 147 Swiss "Ouvriers" of the Compagnie des Indes, under the command of Sieur de Merveilleux and his brother. French speaks of 347 Swiss.

Shortly before, on the 24th of January, 1721, four ships had sailed from the French port of L'Orient for Louisiana with 875 Germans and 66 Swiss emigrants. The names of these ships were "Les Deux Freres," "La Garonne," "La Saonne," and "La Charante." Of these four ships the official passenger lists, signed by the authorities of L'Orient, have been preserved, and a copy of the same came into the possession of the "Louisiana Historical Society" in December, 1904. From these it appears that these emigrants, who had, perhaps, traveled in troops from their homes in Germany and Switzerland to the port of embarkation, were divided on board according to the parishes whence they had come. Each parish had a "prevot" or "maire," whilst the leader of the Swiss bears the title of "brigadier." We find the parishes of

Hoffen (there is one Hofen in Alsace, one in Hesse-Nassau, three in Wurtemberg, also five "Hoefen" in Germany) ;

Freiburg (Baden) ;

Augsburg (Bavaria) ;

Friedrichsort (near Kiel, Holstein) ;

Freudenfeld (some small place in Germany not contained even in Neumann's "Orts-und Verkehrs-Lexicon," which gives the names of all places of 300 inhabitants and upwards);

Neukirchen (many places of that name in Germany, but this seems to have been Neukirchen, electorate of Mayence) ;

Sinzheim (one Sinzheim and one Sinsheim, both in Baden) ;

Freudenburg (Treves [Trier], Rhenish Prussia) ;

Brettheim (Wurtemberg) ;

Wertheim (on the Tauber, Germany) ;

Sinken (one Singen near Durlach, another near Constance, both in Baden, Germany) ;

Ingelheim (near Mayence, Prussia);

Hochburg (Baden).

It would seem strange that, in spite of the great number of people whom these four vessels had on board for Louisiana, not one of our Louisiana historians should mention by name the arrival in the colony of more than one of these ships. There is a horrible cause for this: but few of these p4i emigrants survived the horrors of the sea voyage and landed on the coast of Louisiana!

The one ship mentioned as having arrived is "Les Deux Freres," which La Harpe reports as having reached Louisiana on the 1st of March, 1721, with only 40 Germans for John Law out of 200 who had gone on board in France. The official passenger list before me mentions 147 Germans and 66 Swiss, or 213 persons on board. Therefore i/j lives out of 21^ were lost on this ship alone on the sea!

And the other three vessels? Martin says that in March, 1721, only 200 Germans arrived in Louisiana out of 1200 embarked in France. Martin, no doubt, refers to the 875 Germans and 66 Swiss on board the four ships just mentioned, with, perhaps, one or two additional ships.

"La Garonne" was the ship with the 300 "very sick" Germans which was taken by the pirates near San Domingo.

What suffering must have been endured on board these pest ships, what despair! Fearful sickness must have raged with indescribable fury.

The history of European emigration to America does not record another death rate approaching this. The one coming nearest to it is that of the "Emanuel," "Juffer Johanna," and "Johanna Maria," three Dutch vessels which sailed from Helder,

the deep water harbor of Amsterdam, in 1817, with 1150 Germans destined for New Orleans. They arrived at the mouth of the Mississippi, after a voyage of five months, with only 597 passengers living, the other 503 having died on the sea from starvation and sickness, many also in their fever and utter despair having jumped overboard.^°

There is a document attached to the passenger lists of the four pest ships from L'Orient, giving the names of sixteen Germans who were put ashore by the ship "La Garonne" in the port of Brest, France, a few days after her departure from L'Orient, and left at Brest at the expense of the company "chez le Sieur Morel as sick until their recovery or death." All sixteen died between the loth and the 27th of February, 1721, proving the deadly character of their malady. This disease having broken out immediately after the departure of "La Garonne" from L'Orient, and evidently on all four vessels, we may assume that the passengers were already infected while still in port, and it must have broken out a second time on board "La Garonne" after her departure from Brest. The heartless treatment given the emigrants of that time, the lack of wholesome food, drinking water, medicines and disinfectants accounts for the rest.

Among the sixteen victims "chez le Sieur Morel" in Brest are found members of two families well known and very numerous in Louisiana at present:

Jacob Scheckschneider (Cheznaidre) whose parents, Hans Rein-hard and Cath. Scheckschneider, were on board La Garonne with two children; ^^

Hans Peter Schaf, whose parents, Hans Peter and Marie Lis-beth Schaf, were on board the same vessel with two children. The whole family seems to have perished, but there was a second family of that same name on board which will be mentioned presently.

Of other passengers of La Garonne on this terrible voyage should be mentioned:

" See the author's Das Redemptions system im Staate Louisiana, p. 14. " The surviving child, Albert Scheckschneider, became the progenitor of the Scheckschneider family in Louisiana.

Ernst Katzenberger and wife, founders of the Casbergue fam-

ily; Adam Trischl, wife and three children, founders of the Triche

family; Andreas Traeger, wife and child, founders of the Tregre fam-

ily; Jean Martin Traeger and wife, who seem to have perished; Joseph Keller, wife and two children, founders of the Keller

family; Jacob Schaf, his wife and six children (probably related to the

Schaf family mentioned above), the founders of the Chauffe

family.

On the passenger list of the other three pest ships are found:

Heidel (Haydel) Ship La Charante. Widow Jean Adam Heidel and two children. They were two sons, the elder of whom, "Ambros Heidel," married a daughter of Jacob Schaf (Chauffe) and became the progenitor of all the "Haydel" families in Louisiana. His younger brother is not mentioned after 1727.

Ziveig (Labranche) Ship Les Deux Freres. Two families: i) Jean Adam Zweig, wife and daughter; 2) Jean Zweig, wife and two children, a son and a daughter. The daughter married Jos. Verret, to whom she bore seven sons, and later she married Alexandre Baure. The son married Suzanna Marchand and became the progenitor of all the Labranche families. "Labranche" is a translation of the German "Zweig" and appears in the marriage record of the son of Jean Zweig.

Rommel (Rome) Ship Les Deux Freres. Jean Rommel, wife and two children.

Hofmann (Ocman) Ship Les Deux Freres. Jean Hofmann, wife and child. Ship La Saone. Michael Hofmann, wife and two children from Augsburg, Bavaria.

Schantz (Chance) Ship Les Deux Freres. Andreas Schantz and wife.

These vessels having arrived in Biloxi during March, 1721, the 200 survivors of the 1200 Germans no doubt were in Biloxi in the following month, when the greatest of all epidemics raged there, and, after their escape from the dangers of the sea voyage, they again furnished material for disease. Jean Adam Zweig is especially mentioned in the census of 1724 as having died in Biloxi.

Towards the end of May, 1721, the "St. Andre," which

sailed April 13th, 1721, from L'Orient with 161 Germans, arrived in Louisiana. Among them are named Jean George Huber (Oubre, Ouvre), wife and child. A few days later, the "La Durance," which sailed April 23d, from L'Orient with 109 Germans, reached Louisiana. On the passenger list of this ship appears "Caspar Dubs, wife and two children." Caspar Dubs was the progenitor of all the "Toups" families in Louisiana. He was from the neighborhood of Ziirich, Switzerland, where the "Dubs" family still has many branches in the Afifoltern district.

Finally there came, according to la Harpe, on the 4th of June, 1721, the "Portefaix" from France with 330 immigrants, mostly Germans, and originally intended for John Law's concessions. They were under the command of Karl Friedrich D'Arensbourg, a former Swedish officer, then in the service of the Compagnie des Indes. La Harpe says that thirty more Swedish officers came with him.

Charlotte Von Braunschweig-Wolfenbuettel.

A very romantic legend has come down to us from that time. It is said that with the German immigrants of the four pest ships who arrived in Louisiana in March, 1721, there came also Charlotte Christine Sophie, a German princess of the house of Braunschweig-Wolfenbuettel, who had been the wife of the Czarevitch Alexis, the oldest son of Czar Peter the Great of Russia. She is said to have suffered so much from the brutality and infidelity of her husband that, in 1715, four years after her marriage, she simulated death, and while an official burial was arranged for her, she escaped from Russia, and later came to Louisiana, where she married the Chevalier d'Aubant, a French officer, whom she had met in Europe.

Gayarre (Vol. I, page 263) made a very pretty story of this legend, and added a touching introductory chapter. According to him the Chevalier d'Aubaut, a young Frenchman, was attached to the court of Braunschweig as an officer in the duke's household.

"He had gazed so on the star of beauty, Charlotte, the paragon of virtue and of talent in her ambrosial purity of heaven, that he had become mad—mad with love!

Now the princess is on her way to St. Petersburg and her bridegroom is with her, and fast travelers are these horses of the Ukraine, the wild Mazeppa horses that are speeding away with her.

In her escort is a young Cossack officer riding closely to the carriage door, with watchful care and whenever the horses of the vehicle which carried Alexis and his bride threatened to become unruly, his hand was always first to interfere and to check them; and all other services which chance threw in his way, he would render with meek and unobtrusive eagerness; but silent he was as the tomb.

Once on such an occasion, no doubt as an honorable reward for his submissive behavior and faithful attendance, the princess beckoned to him to lend her the help of his arm to come down the steps of her carriage. Slight was the touch of the tiny hand; light was the weight of that sylphlike form: and yet the rough Cossack trembled like an aspen leaf, and staggered under the convulsive effort which shook his bold frame."

It was d'Aubant, of course, the Chevalier of the Braunschweig court, her lover in disguise.

"On the day of their arrival in St. Petersburg he received a sealed letter with two papers. One was a letter; it read thus: 'D'Aubant.

'Your disguise was not one for me. It could not deceive my heart. Now that I am the wife of another, know for the first time my long kept secret—I love you. Such a confession is a declaration that we must never meet again. The mercy of God be on us both.'

The other paper was a passport signed by the Emperor himself, and giving to the Chevalier d'Aubant permission to leave the empire at his convenience.

In 1718 he arrived in Louisiana with the grade of captain in the colonial troops. Shortly after he was stationed at New Orleans, where he shunned the contact of his brother officers and lived in the utmost solitude.

On the bank of the Bayou St. John, on the land known in our day as the Allard plantation, there was a small village of friendly Indians, and beginning where the bridge now spans the bayou, a winding path connected it with New Orleans. There the chevaHer lived, and his dwelling contained a full length portrait of a female surpassingly beautiful, in the contemplation of which he would frequently remain absorbed, as in a trance, and on a table lay a crown, resting not on a cushion, as usual, but on a heart, which it crushed with its weight, and at which the lady from out of the

picture gazed with intense melancholy. Every one felt that it was sacred ground out there on the Bayou St. John.

It was on a vernal evening, in March, 1721, the last rays of the sun were lingering in the west, and d'Aubant was sitting in front of the portrait, his eyes rooted to the ground—when suddenly he looked up—gracious heaven! it was no longer an inanimate representation of fictitious life which he saw—it was flesh and blood—the dead was alive again and confronting him with a smile so sweet and sad—with eyes moist with rapturous tears—and with such an expression of concentrated love as can only be borrowed from the abode of bliss above.

Next day they were married, and in commemoration of this event they planted those two oaks, which, looking like twins, and interlocking their leafy arms, are, to this day, to be seen standing side by side on the bank of the Bayou St. John, and bathing their feet in the stream, a little to the right of the bridge as you pass in front of Allard's plantation."

Such is Gayarre's account. It is a pity to destroy such a pretty legend, but the historian is not the man of sentiment— lie seeks truth.

Let us examine this story critically, first acquainting ourselves with conditions in Russia, whence it emanated.

Alexis, the husband of the German princess, was at the head of the old Russian pai'ty which violently opposed the reforms introduced by the Czar Peter the Great, the father of Alexis. A conspiracy was foi-med by this party to frustrate the reforms, and the Czar, fearing for the success of his plans, forced Alexis, the heir apparent, to resign his claims to the Russian succession and to promise to become a monk. When Peter the Great was on his second tour through Western Europe, however, Alexis, with the aid of his party, escaped and fled to Austria. Very unwisely he allowed himself to be persuaded by Privy Counsellor Tolstoi to return from Vienna to Russia, whereupon those who had aided him suffered severe punishment, and Alexis himself was condemned to death. It is true, the sentence was commuted by the Czar, but Alexis died, in 1718, from mental anguish, it was said, but according to others he was beheaded in the prison. To meet the accusations of unjust treatment of his son, the Czar published the records of the court proceedings, proving the conspiracy.

There can be no doubt that the enemies of the Czar, especially the very strong and influential old Russian party, did everything in their power to make the treatment Alexis had received at the hands of his father appear as one of the blackest crimes, and that the Czar's party retaliated by blackening the character of the Czarevitch as much as lay in their power.

At that time, and for the purpose of defaming the character of the dead prince, the story that the German princess, his wife, had simulated death to escape from the martyrdom of a supposedly wretched married life, must have been invented by the partisans of the Czar. Why should she have gone to Louisiana, and nowhere else? Because everybody went to Louisiana at that time. It was the year 1718. That was the very time when John Law and the Western Company were spreading their Louisiana pamphlets broadcast over Europe; it was the time when thousands of the countrymen of the dead princess were preparing themselves to emigrate to the paradise on the Mississippi; it was the time when the name of Louisiana was in the mouth of every one. Moreover, Louisiana was at a safe distance—far enough away to discourage any attempt to disprove the story.

The tale, too, was repeated with such persistency that many European authors printed it, that thousands believed it, and that even official inquiries seem to have been instituted.

As to the princess' alleged Louisiana husband, the Chevalier d'Aubant, who was said to have married her in New Orleans in March, 1721, the present writer desires to say that he has carefully and repeatedly examined the marriage records of New Orleans, Mobile and Biloxi from 1720 to 1730 without meeting with such a name, or any name similar to it. Moreover, Mr. Hamilton, of Mobile, the author of "Colonial Mobile," ^^ who examined the Mobile records completely and with infinite care, found only a French officer "d'Aubert" (not d'Aubant), who, in 1759, thirty-eight years later, commanded at Fort Toulouse; but this d'Aubert was married to one Louise Marg. Bernoudy, a daughter of a numerous and well-authenticated French pioneer family of Mobile.

" See pages 89 and 164 of that work.

The story of the romantic Louisiana marriage is therefore without foundation, and so the legend is a myth, although Allard's plantation, near New Orleans, is pointed out to us as the dwelling place of the lovers, and the two "leaflocked oak trees right by the bridge still bear witness to their happiness."

Pickett, in his "History of Alabama," claims the couple as residents of Mobile. Zschokke, the German novelist, makes them residents of "Christinental on the Red River," and others place them in the Illinois district; i. e., the country north of the Yazoo River.

Martin says the King of Prussia called Charlotte's alleged lover "Maldeck." How the King of Prussia was hauled into the story can easily be explained. Louisiana was a French province, and (as will be shown in the chapter "Koly") the Prussian ambassador at the court of France was either for his own account, or as a representative of his king, financially interested in the St. Catherine enterprise in Louisiana; and he was therefore believed to be in a better position and nearer to the channels of information to make inquiries about affairs and people in Louisiana than any other German official in Paris. If, therefore, the family of Braunschweig-Wolfenbuettel desired to investigate the rumors current at that time, they had no better means of doing so than to request the King of Prussia to instruct his ambassador in Paris to make researches. The Prussian ambassador possibly reported that there was a man in Louisiana, by the name of "Maldeck" who claimed his wife to be the princess.

As to the name of "Maldeck," the writer will say that he found that name, or, rather, a name so similar to it that it may have stood for the same. In the passenger lists received by the "Louisiana Historical Society" from Paris in 1904 (see page 106), a laborer named "Guillaume Madeck" is mentioned, a passenger on the ship "Le Profond," who, from the 8th of May, 1720, to the 9th of June, 1720, the day of the departure of the vessel for Louisiana, had received thirty-three rations. A man of such humble station, however, would certainly not have suited a princess for a husband, and so, if the story was ever circulated in Louisiana, either Wilhelm Maldeck, or his Louisiana wife, claiming to be a princess, must have imposed upon the people.

John Law, a Bankrupt and a Fugitive. ^^

With the ship "Portefaix," so La Harpe informs us, the news of the failure of John Law and his flight from Paris reached the colony of Louisiana.^* The news of Law's flight seems to have paralyzed the Compagnie des Lides, for it took them many months to decide what should be done with Law's concessions on the Arkansas River and below English Turn." The German engages on the Arkansas River, who probably arrived there about the end of 1720, or in the spring of 1721, had not yet been able to make a crop, as the preparatory work of clearing the ground and providing shelter for themselves had occupied most of their time, and much sickness also prevailing among them, they were unable to begin farming operations on a larger scale before August, 1721.

These Germans therefore needed assistance until they could help themselves, for not another livre was to be expected from the bankrupt John Law; and the concession must be given up unless the company or some one else should step in to provide for those people.

It seems incomprehensible that the directors of the company in Louisiana, under these circumstances, should have waited from the 4th of June to beyond the middle of November of the same year to decide to take Law's concessions over; and even after they had decided to manage the concessions in the future for their own account, the resolution was not carried out, as Law's agent on the Arkansas, Levens, refused to transfer the

" Law left Paris on the loth of December, 1720, for one of his estates six miles distant. There Madame Brie lent him her coach, and the Regent furnished the relays and four of his men for an escort. Thus Law travelled towards the Belgian frontier. Returning her coach, Law sent the lady a letter containing a ring valued at 100,000 livres. (Schuetz, Lehen und Char-akter der Elisabeth Charlotte, Herzogin von Orleans, Leipzig, 1820.)

"This statement of La Harpe cannot be accepted as correct. Law left France about the middle of December and the news of his flight spread rapidly. The ship La Mutine arrived in Louisiana on the 3d of February; the four pest ships which sailed from L'Orient on the 24th of January— six weeks after Law's flight—arrived in March; the ship St. Andre, which sailed April 13th, came towards the end of May, and a few days later came La Durance, which sailed April 23d, and still no news of the disaster? The ship Portefaix with D'Arensbourg on board, which arrived on the 4th of June, may have brought some instructions concerning the steps to be taken in the matter, but the first news must have reached the colony much earlier.

business to the company or to continue it in the company's name. Furthermore, as this man, in spite of his refusal to carry out orders, was left undisturbed in his position,^^ it happened that the German engages in the meantime received help neither from one side nor from the other to bridge them over to the harvesting time of their first crop, but v^rere forced to ask help of their only friends, the Arkansas and the Sothui Indians. Finally, when help from this last source failed, and small-pox broke out among the Indians and the Germans, they were forced to give up all and abandon the concession.

The Germans Leave Law's Concessions en Masse, Appear IN New Orleans, and Demand Passage for Europe. According to tradition, the Germans on the Arkansas resolved ^® to abandon Law's concession and to go down the Mississippi to New Orleans. Only forty-seven persons remained behind, whom La Harpe met there on the 20th of March, 1722, when he installed Dudemaine Dufresne, but when La Harpe returned from his other mission, viz., the search for the imaginary "Smaragd Rock" in Arkansas, these too had departed.

The arrival of the flotilla of the Germans from the Arkansas River must have been a great surprise for the people of New Orleans. This city was at that time in its very infancy, and seems to have looked more like a mining camp than a town. The engineer Fauget, who went there in March, 1721, to lay out the streets, found in the bush only a small number of huts covered with palmetto leaves or cypress bark; and the Jesuit Charlevoix wrote from New Orleans on the loth of January, 1722, i. e., immediately before the arrival of the Germans from the Arkansas, that New Orleans was a wild, lonely place of about a hundred huts, and almost completely covered by trees and bushes. He found two or three houses, it is true, but such as would not have been a credit to any French village, a large wooden warehouse, and a miserable store, one-half of which had been lent to the Lord for religious services; but, he said, the

" He was replaced only in March, 1722, by Dudemaine Dufresne. " It seems to have been at the end of January or in February, 1722.

people want the Lord to move out again and to accept shelter in a tent. Indeed, New Orleans contained at the taking of the census of November 24th, 1721, excluding soldiers and sailors, only 169 white persons, and the Germans who came down from the Arkansas must have outnumbered them considerably.

The surprise created by their arrival must have been a very unpleasant one for the officials of the Compagnie des Indes. Indeed, the Germans did not come to thank them for favors, and is it to be imagined that some very plain words were spoken by the Germans to the officials of the company; in fact, it is said that Governor Bienville interceded, and when they demanded passage back to Europe, tried his best to induce them to remain.

The results of the conferences were: first, that the Germans from the Arkansas were now given rich alluvial lands on the right bank of the Mississippi River about twenty-five miles above New Orleans, on what is now known as "the German Coast,'' comprising the parishes of St. Charles and St. John the Baptist, where, in 1721, two German villages, of which we shall hear more, already existed; secondly, that the agent on the Arkansas, Levens, was deposed; and, thirdly, that provisions were sent to the Germans who still remained there.

The Family of D'Arensbourg.

The family of Charles Fred. D'Arensbourg is very important in the history of the German Coast, and as doubts existed until now as to its real descent, it will be treated here at some length.

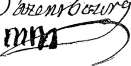

The former Swedish officer who had charge of the German immigrants of the ship "Portefaix" and who became the commander of the German Coast, signed his name:

^hiom^^

and the tradition among his descendants is that he was a nobleman.

Examining his signature, we notice at the end of the first letter a decided downward stroke, making it appear as if this downward stroke was intended to serve as an apostrophe, and that the man really intended to write "D'arensbourg", a form of name which would support the tradition of noble lineage.

The names of the older nobility being usually names of places, we shall now consider the only two places by the name of "Arensburg", which exist in Europe: one in the principality of Schaumburg-Lippe, Germany, and the other on the island of Oesel in the Bay of Riga, province of Livonia, Russia. As the principality of Schaumburg-Lippe is in Germany, and as the Russian province of Livonia was founded by Germans at Riga, in 1200, and belonged to the territory of the "German Knights" for centuries, and as the nobility of Livonia and the other Baltic provinces have kept their German blood pure to the present day, a noble family of that name would in either case be of the German nobility, and the original form of the name would be "von Arensburg".

As our Louisiana D'Arensbourg was a former Swedish officer, and as the town of Arensburg on the island of Oesel in the Bay of Riga, together with the whole province of Livonia, belonged to Sweden up to the year 1721, the year of Chas. Fred. D'Arensbourg's emigration to Louisiana, and as thirty other Swedish officers are said to have come with him to Louisiana in 1721, it might be assumed that our Louisiana D'Arensbourg belonged to the Riga branch of the German noble family "von Arensburg", and that, at the cession of Livonia to Russia, in 1721, our D'Arensbourg, together with thirty compatriots, who all had fought on the Swedish side against Russia, preferred exile to Russification, and emigrated to. Louisiana in the year 1721.

Wishing to obtain more definite, and, if possible, official information as to the descent of this D'Arensbourg, the present writer addressed the Imperial German Consul in Riga, and this gentleman, "Herr Generalconsul Dr. Ohneseit", kindly submitted the questions to the chancellory of the "Livlaendische Ritterschaft, Ritterhaus, Riga", where the resident "Landrat" ordered re-

searches with the result that the name of "von Arensburg" could be found neither in the church records of Livonia nor in the records of the "Livlaendische Hofgericht", to whose jurisdiction the island of Oesel belonged during the Swedish dominion and even later. Both the archivist and the notary of the "Livlaendische Ritterschaft" write furthermore that no family by the name of "von Arensburg" can be found in the literature relating to the Swedish, the Baltic, the Finnish or the German nobility. This settles the question of noble lineage.

"Herr von Bruningh," the archivist of the "Ritterschaft," however, agrees with the author, that "D'Arensbourg" points to the island of Oesel as the home of the man. It was also suggested that the man may have added "d'Arensbourg" to his family name (which must have been "Karl Friedrich") in order to indicate his birth place, or place of last residence or garrison, or in order to distinguish his family (there being many Fried-richs) from other branches of the same name, "which was not seldom done." Indeed, there were even several Friedrich families in Louisiana, and the census of 1724 mentions two of them, Nos. 2 and 42 in that census. In this case the change of name must have taken place before the departure from France, since the commission held by the Swedish officer was issued in the name of "Charles Fred. D'Arensbourg."

The following is offered as a possible solution: The former Swedish officer "Karl Friedrich," a German and a native or former resident of Arensburg on the island of Oesel, having determined to emigrate to Louisiana rather than become a Russian subject, applied to the Compagnie des Indes for a position in the colony, and in his petition, written in French, signed his name "Charles Friedrich," and added to it "d'Arensbourg" to indicate his birthplace, or place of last residence or garrison. The French officials, mistaking "d'Arensbourg" for his family name, issued his commission to "Charles Frederic d'Arensbourg;" and it being thus entered on the books of the company, and the man being known and addressed officially in that way, he was forced to adopt this as his family name.

The wife of D'Arensbourg, too, is said to have been a

Swedish lady, and her name, according to our historians, was "Catherine Mextrine." This is surely an error, for the author finds that D'Arensbourg was a single man when he came to Louisiana, in 1721. At least the census of 1724 mentions him as a bachelor, aged thirty-one, though the census of 1726 reports him as having a wife and one child. D'Arensbourg was, therefore, married in Louisiana, and we shall prove that his wife's name was neither "Catherine" nor "Mextrine," and that she was not from Sweden, but from "Schwaben" (Wiirtem-bsrg).

The last three letters "ine" of the name "Mextrine" alone betray her as a German woman. It is the suffix "in," which was formerly added to the family names of married ladies in Germany. We had a German poetess by the name of "Kar-schin," the wife of a tailor named "Karsch;" the wife of a Mr. Meyer used to be called "Frau Meyerin," and I still remember that old people used to call my good mother "Frau Deilerin."

The French officials in Louisiana used to add an "e" to the

"in" in order to retain the German pronunciation of the suffix.

Thus the church records of Louisiana have:

Folsine, i. e., the wife of Foltz, Lauferine, i. e., the wife of Laufer, and Cheffcrine, i. e., the wife of Schaefer.

The "x" in Mextrine is a makeshift for the German hissing sound of "z" or "tz," for which there is no special sign in French, "z" in French sounding always like a soft "s."

In proof of all this a facsimile of the signature of "Catherine Mextrine" is given here, which the author found in the marriage contract entered into between her granddaughter, Marie de la Chaise, and Frangois Chauvin de Lery on the 23d of July, 1763:

It will be noticed that she signed her name without the final French "e," just as a German woman of that time would have written the feminine form of the name "Metzer."

Her family name, then, was "Metzer," and according to family tradition she was from Wurtemberg. The present writer is inclined to think that she was the daughter of one Jonas "Mes-quer" (French spelling), who, according to the passenger lists, sailed with his wife and five children on the 13th of April, 1721, on board the ship "St. Andre" from L'Orient for Louisiana.

In the marriage contract of her eldest son, who married FranQoise de la Vergne on the i8th of June, 1766, the mother of the bridegroom is called by the French notary "Marguerite Mettcherine." Here we also have her Christian name which corresponds with the initial of her own signature. It is not "Catherine" but "Marguerite," a favorite German name for women.

Karl Friedrich D'Arensburg served for more than forty years as commander and judge of the German Coast of Louisiana, sharing alike the joys and hardships of his people, and on one occasion, at least, taking an important part in political matters.

It is the proper place here to mention the part he, then a man of seventy-six years of age, played in the rebellion against the Spanish in 1768.

UUoa, the Spanish governor, who had come to Louisiana in March, 1766, to take possession of the colony in the name of the King of Spain, to whom France had ceded Louisiana in 1763, had found the population very hostile; and, as he had only ninety soldiers with him, he did not formally take possession of Louisiana, but requested the French commander to hold over and act under Spanish authority until more Spanish troops should arrive. This interim lasted until the 28th of October, 1768, when the people rose and UUoa was forced to retire to Havana.

During this year Ulloa had taken from the Germans of the German Coast provisions to the value of 1500 piastres to feed the Acadians, who had but recently come into the colony, and were not able yet to sustain themselves.^'^

"On the 28th of February, 1765, 230 persons, natives of Acadia (Nova Scotia) arrived in Louisiana. They came from San Domingo, where they had found the climate too hot, and were in great misery. Their whole for-

Hearing of the ferment all over the colony, and fearing that the Germans might make the nonpayment of their claims a pretext to join tlie conspirators, Ulloa, on the 2Sth of October, 1768, sent a man by the name of Maxant with 1500 piastres to the German Coast to settle the indebtedness of the Spanish government.

In a letter dated Havana, December 4th, 1768, one day after his arrival from New Orleans ("Notes and Documents," page 892) Ulloa says:

"In the early morning after Maxant's departure Lafreniere and Marquis sent Villere and Andre Verret in pursuit of Maxant to prevent the remitting of the money to the Germans, fearing that if he should satisfy them they might no longer have any motive to join the cause of the conspirators.

"Maxant arrived at the habitation of D'Arensbourg for whom I had given him a letter and when he delivered it to him he found him to be so different a man from what he expected him to be—in spite of his great age determined to defend liberty and neither wanting to be a subject of the king (of Spain), nor the country to belong to the king.

"Maxant was arrested by Verret on the place of Cantrelle, the father-in-law of another Verret and Commander of the Acadians, where he was much maltreated. Verret declared later that he received the order to arrest Maxant from Villere, Lafreniere and Marquis."

Ulloa in this letter expresses the belief that D'Arensbourg had been influenced by his relatives, Villere, the commander of the German militia, and de Lery, the commander of the militia in Chapitoulas. It is true that Villere was married to Louise de la Chaise, and Frangois Chauvin de Lery to Marie de la Chaise, both granddaughters of D'Arensbourg, that de Lery was a first cousin to Chauvin Lafreniere, the attorney general of the col-tune consisted of only 47,000 livres in Canadian paper, which the people of Louisiana refused to accept. Focault demanded permission from Paris to reimburse them, gave them 14,000 livres worth of merchandise and provisions, and sent them to Opelousas and the country of the Attakapas.

On the 4th of May, 1765, 80 persons from Acadia arrived and went to Opelousas.

On the Sth of May, 1765, 48 Acadian families arrived and were sent to Opelousas.

On the l6th of November, 1766, 216 Acadians arrived from Halifax. They were sent to "Cahabanoce," the present parish of St. James. These were the ones who received the provisions which the Spanish government took from the Germans on the German Coast.

ony and orator of the rebellion, whose daughter was the wife of Noyan, the leader of the Acadians.

But it needed no persuasion to make D'Arensbourg take the stand which he took, for Ulloa himself had furnished more than sufficient grounds to make him do so:

Ulloa had forbidden the flourishing trade with the English neighbors (September 6th, 1766);

He had closed the mouths of the Mississippi, except one where the passage for vessels was most difficult and dangerous;

He had refused to pay the costs of administration since the transfer of Louisiana to Spain (1763), and wanted to be responsible only for the obligations incurred since his arrival (March, 1766), thereby repudiating the salaries of officials, officers, and soldiers for three years;

He had imposed crushing burdens on export and import—vessels from Louisiana must offer their cargoes for sale first in Spain, and only when there were no purchasers in Spain were they allowed to go to the ports of other countries, whence they had to return to Spain in ballast, for only there could they load for Louisiana;

And, finally, by ordinance published May 3d, 1768, he prohibited commerce with France and the French West Indies.

This last ordinance was the most terrible blow of all for the colony. The flourishing lumber trade with San Domingo and Martinique was ruined thereby, and, with the ports of France closed, and only those of Spain open, the Louisiana products were at once thrown into direct and absolutely ruinous competition with those of Spanish America; for Guatemala furnished better indigo, the Isle of Pines more tar and resin, and Havana better tobacco than Louisiana.

All this tended to depress prices for the Louisiana products. Furthermore, would the colonists find a market fpr their goods in Spain as they had in France? Louisiana peltries received in trade from the Indians, the chief staple of the Indian trade, had less value in Spain, because they were used less there than in France; and the industries of Spain, much inferior to those of France, could not furnish the colonists with the class of goods which they needed to compete with the English traders in the Indian trade. Add to this the uncertainty as to the fate of the French paper circulating in Louisiana, and it will be easily understood that values of all kinds depreciated fully fifty per cent.

In addition to these hardships it must not be forgotten that, if this ordinance had been put in force, every man, woman, and child in the colony would have been compelled to give up their beloved Bordeaux wine and drink the "vin abominable de Catalogue."

All these reasons combined were surely enough to determine D'Arensbourg, who before the publication of the ordinance prohibiting trade with France seems to have acquiesced in the Spanish dominion, to take the stand he took. Indeed he did not need the persuasion of his relatives. No other stand was possible.

It was on the German Coast that the Revolution of 1768 began. D'Arensbourg, the patriarch of the Germans, defied the messenger of the Spanish governor; and it was surely D'Arensbourg's word and D'Arensbourg's influence that enabled Villere to march two days later with 400 Germans upon New Orleans where the Germans took the Chapitoulas Gate on the morning of October 28th. The Acadians under Noyan, the militia of Chapitoulas under de Lery and the people of the town followed; and on the morning of the 29th they marched upon the public square (Jackson Square) before the building of the Superior Council to support the demand of Lafreniere to give Ulloa three days' time to leave Louisiana. The resolution was carried, and the people greeted the news with shouts of: "Vive le roi"! "Vive Louis le bien aime!" "Vive le vin de Bordeaux!" "A bas le poison de Catalogue!"^* Ulloa left on the ist of November on a French vessel for Havana.

The success of the revolution was due chiefly to Lafreniere, the Canadian orator, to Marquis, a Swiss and the commander of the revolutionary forces, who wanted to found a republic after the pattern of Switzerland, and to D'Arensbourg and the German and the Canadian militia.

A few Spanish officers having remained when Ulloa sailed, and Ulloa's frigate having been left behind "for repairs," the colonists frequently gave vent to their hostility to the Spanish;

'Franz in his "Kolonisation des Mississippitales" (Leipzig, 1906).

and in December a petition to the Superior Council was circulated demanding the removal of both the Spanish officers and the ship. A resolution to that effect was adopted by the Council, but it was never put into effect.

Meanwhile the news expected from France, where a commission of prominent Louisianians had petitioned the king to take possession of the colony again, did not arrive, and the hopes of the leaders of the rebellion against Spanish rule began to waver. They did not wish now to risk an attack on the Spanish frigate, and when the Germans of the German Coast threatened to march again to New Orleans to drive out the Spaniards, Lafreniere himself became alarmed and persuaded them to desist.

On the 24th of July, 1769, the news reached the city that the Spanish general O'Reilly had arrived at the mouth of the Mississippi with large forces to take possession of Louisiana. Again Marquis called the people to the public square, and implored them to defend their liberties; and again the Germans from the German Coast entered the city to oppose O'Reilly's entrance. But most of the others had already resolved to surrender, and so the Germans too had to give up their design.

Six of the leaders of the revolution were condemned to death, among them Villere, Lafreniere, Marquis, and Noyan. Tradition informs us that O'Reilly intended also to have D'Arens-bourg included, but that the latter was saved through the intercession of Forstall, under whose uncle O'Reilly is said to have served in the Hibernian regiment in Spain.

D'Arensbourg was made a chevalier of the French military order of St. Louis on the 31st of August, 1765, and died on November i8th, 1777. His wife died December 13th, 1776. They left numerous descendants.

The German Coast.

The district to which Law's Germans from the Arkansas River were sent after their descent to New Orleans begins about twenty-five miles (by river) above New Orleans, and extends about forty miles up the Mississippi on both banks.

The land is perfectly level; at the banks of the river, how-

ever, it is a little, almost imperceptibly, higher, because of the deposit the Mississippi had left there at every overflow. At a distance from one to three miles from the river it becomes lower, and gradually turns into cypress swamps, so that on each side of the Mississippi only a strip from two to three miles in width is capable of being cultivated. For this reason land there is estimated only according to the arpent river front, to each arpent front belonging forty arpents in depth. This is what is called in deeds "the usual depth." An arpent is about 182 feet.

Large dikes, called "levees," now restrain the Mississippi from spreading over the lands in time of high water; but as the sediment deposited continually raises the river bed, the levees, too, must be made higher and higher. They are now from twenty to thirty feet high, the celebrated Morganza levee measuring even thirty-five feet. On this account, only the roofs of two-story houses can be seen from the middle of the river.

The crown of the levee, where a delightful breeze is found even during the hottest part of the day, is from six to ten feet wide, affording, besides a beautiful view of the Mississippi and the vast area of level land back to the cypress swamps, a very pleasant promenade where the people love to gather.

Along the inland base of the levee runs the only wagon road up the coast/® and still farther inland, between majestic shade trees or groves, stand the palatial mansions of the planters with their numerous outhouses. Some distance in the rear are the sugar houses with their big chimneys; and from these a wide street, lined with a double row of little white cabins with two or four rooms each, leads to the fields. In the days of slavery this was the negro quarters, but now the free laborers and field hands, mostly Italians, live there.

The fields, whose furrows run invariably at right angles with the river, extend as far as the eye can see, to the cypress forests in the swamps. Every fifty or sixty feet a narrow but deep and well kept ditch runs in the same direction; little railroads lead from the fields, whence they carry the sugar cane to the sugar houses, and in the month of November, when the grinding

"The banks of the Mississippi River are called "coast." Hence the "German Coast."

season begins, these fields, with the waving sugar cane, afford a beautiful sight. Four important railroads, running parallel to the Mississippi, intersect the rear of the plantations, the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley and the Louisiana Railway and Navigation Co.'s line on one side of the Mississippi, and the Southern and the Texas Pacific on the other. Between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, the people plant mostly sugar cane, but also some rice and com. Beyond Baton Rouge, cotton takes the place of the sugar cane.

In some places wide strips of torn up land, with hollows and trenches scooped out, and with little hills of deposit extend from the river to the swamp. These are places where the Mississippi has broken through the levee, its mighty waters rushing with a roar heard for miles down upon the land twenty or thirty feet below, wrecking houses, uprooting trees, carrying off fences, and inundating and devastating hundreds of miles of the richest lands.

Little crawfishes from the river sometimes crawl up to the base of the levee and work their way through the earth masses. The water follows them, and all of a sudden a little spring bubbles up on the inland slope of the levee. If this is not discovered at once by the guards watching at high water time day and night, it widens rapidly until the earth from the top tumbles down, and a "crevasse" results. However small this opening may be in the beginning, it will, through the crumbling away of both ends, soon extend hundreds of feet, and so great is the force of the current that even large Mississippi steamers have been carried through such breaks.

Woe to the planter who does not, at the first warning, flee with his people and his stock to some safe place on the crown of the levee where rescue steamers can reach them.

Sometimes also defective rice flumes, laid through the levee to obtain water for the rice fields, have caused crevasses.

On the left bank of the German Coast, between Montz and La Place, two stations of the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley Railway, such a strip of torn up land may be seen. Here was "Bonnet Carre Crevasse (April nth, 1874) which was 1370 feet wide, from twenty-five to fifty-two feet deep and which

remained open for eight years. Further up the river, and on the same side, near Oneida (Welham station of the same railroad) was "Nita Crevasse," which occurred on the 13th of March, 1890, and was 3000 feet wide. Both these crevasses did immense damage even to the German farmers near Frenier, more than ten miles distant from the break, where the crevasse water entered Lake Pontchartrain and washed so much land into the lake that houses which stood 150 feet from the shore had to be moved back.

This is the German Coast of to-day. At the time of the settling of the German pioneers, in 1721, it was quite different. There were no levees then, and the whole country was a howling wilderness.

This district was called "La Cote des Allemands," but usually only "Aux Allemands." During the Spanish period (after 1768) it was called "El Puerto des Alemanes," and when the district was divided there were a "Primera Costa de los Alemanes" and a "Segunda Costa." Since 1802 the lower part has been called "St. Charles Parish," and the upper "St. John the Baptist Parish."

50 The Settlement of the German Coast of Louisiana

The First Villages on the German Coast.

The weight of authority and tradition among our Creole population of German descent up to the present time has favored the legend that Karl Friedrich D'Arensbourg, who came to Louis-ana on the ship "Portefaix" on the fourth of June, 1721, was the leader of the Germans already on the Arkansas River, and that he came down from there with Law's Germans to the German Coast.