Alfred Roman. Military Operations of General Beauregard in the war Between the States, 1861 to 1865, vol. II.

Stopped at beginning of Chapter 28: Fix the mdashes (review dashes at top of chapter 27); Add itailics and quotation marks when needeed; indent blocks of quotes; make sure paragraphs break correctly;(note: footnotes have not been formatted)

MILITARY OPERATIONS

OF

GENERAL BEAUREGARD.

CHAPTER XXVI.

When it was learned in Richmond that General Beauregard had reported for duty a strong effort was made to obtain for him a command suitable to his rank. A personal friend of his, the Hon. C. J. Villeré, Member of Congress from Louisiana, and brother-in-law to General Beauregard. on September 1st, telegraphed him as follows: “Would you prefer the Trans-Mississippi to Charleston?” His characteristic reply was: “Have no preference to express. Will go wherever ordered. Do for the best.”

The War Department had already issued orders assigning him to duty in South Carolina and Georgia, with Headquarters at Charleston; but he did not become aware of the fact until the 10th of September.* See General Cooper's despatch, in the Appendix to this chapter. He left the next day for his new field of action, and, in a telegram apprising General Cooper of his departure, asked that copies of his orders and instructions should be sent to meet him in Charleston.

Thus it is shown that the petition to President Davis, spoken of in the preceding chapter, was presented while General Beauregard was on his way to his new command, in obedience to orders from Richmond, and that he knew nothing of the step then being taken in his behalf.

Charleston was a familiar spot to General Beauregard, and one much liked and appreciated by him. With the certainty he now had of not being reinstated in his former command, no other appointment could have given him so much pleasure. He arrived there on the 15th of September, and received a warm and cordial greeting both from the people and from the authorities. It was evident that grave apprehensions were felt for the safety of the city—“that cradle of the rebellion,” as it was called by the Northern press. And all the more was General Beauregard welcomed to Charleston because General Pemberton, whom he was to relieve, did not enjoy the confidence and esteem of the Carolinians. General Pemberton was a brave and zealous officer, but was wanting in polish, and was too positive and domineering in manner to suit the sensitive and polite people among whom he had been thrown. He commenced his administration of affairs there by removing the guns from Cole's Island, and opening the Stono River to the invasion of the Federal fleet and, army; after which there was no quiet for Charleston.

Two unfortunate circumstances had further contributed to the distrust of General Pemberton. Shortly before General Beauregard's arrival he had proclaimed martial law in the city of Charleston without authority, it was alleged, from the President. and contrary to the wishes of the Governor of the State. This added to his unpopularity. He had also officially advised the abandonment of the whole coast-line of defences, and commenced preparations therefore.* See, in Appendix, General Thomas Jordan's letter on the subject. This was done in apprehension of the attack of the new monitors and ironclads, highly extolled at that time by all the Northern newspapers. This act had so exasperated the State and city authorities that Governor Pickens had written to the War Department, demanding the immediate removal of General Pemberton. He had also telegraphed to General Beauregard, requesting him to come again to fight our batteries. His despatch ended thus: “We must now defend Charleston. Please come, as the President is willing—at least for the present. Answer.” And, as has been already shown, General Beauregard, believing that such a transfer would take him permanently from Department No. 2 and his army at Tupelo, declined to accept Governor Pickens's proposal.

Governor Pickens's despatch, here alluded to, and General Beauregard's answer, were given in the Appendix to the preceding chapter.

In writing upon this phase of the war we are met by two serious obstacles: first, the necessity of condensing into a few chapters a narrative of events which of itself would furnish material for a separate work; second, the loss of most of General Beauregard's official papers, from September, 1862, to April, 1864; in other words, all those that referred to the period during which he remained in command of the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. It may be of interest to tell how that loss occurred.

When, in the spring of 1864, General Beauregard was ordered to Virginia, to assist General Lee in the defence of Richmond, he sent to General Howell Cobb, at Macon, for safe-keeping, all his official books and papers collected since his departure from the West. After the surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston's army at Greensboroa, North Carolina, in April, 1865, he telegraphed General Cobb to forward these important documents to Atlanta, through which city he knew he would have to pass on his way to Louisiana. They never reached that point. General Wilson, commanding the Federal cavalry in Georgia, took possession of them while in transitu to Atlanta, with a portion of General Beauregard's personal baggage. Immediate efforts were made to secure their restoration, but in vain: baggage and papers were sent to Washington by order, it was said, of Mr. Stanton, Secretary of War. At a later date General Beauregard succeeded in recovering his baggage; but, despite his endeavors and the promise of high Federal officials, he could not get his papers. These were finally placed in the War Records office, and through the attention of the gentlemanly officers in charge he has been able to procure such copies of them as were indispensable for the purposes of this work. We are credibly informed that military papers and documents belonging to General A. S. Johnston, and embracing only six or seven months of the beginning of the war, were bought, a few years ago, from his heirs for the sum of ten thousand dollars; while General Beauregard's papers, relating to upwards of twenty months of a most interesting part of our struggle, are kept and used by the Government with no lawful claim to them and in violation, as we hold, of the articles of surrender agreed upon by Generals Johnston and Sherman. We may add that General Beauregard is not only deprived of his property, but is forced to pay for copies of his own papers whenever the necessity arises to make use of them.

General Pemberton was anxious to turn over his command to General Beauregard, but the latter would not accept it until he had examined, in company with that officer, all the important points and defences of the Department as it then stood. Accordingly, on the 16th of September, they began a regular tour of inspection which lasted until the 21st. They were, at that date, in Savannah. On the 24th, having returned to Charleston, General Beauregard went through the usual formality of assuming command.

The result of his inspection is given in his official notes, to be found in the Appendix to the present chapter. He made his report as favorable as possible, and was not over-critical, especially in matters of engineering, as he well knew his predecessor had but a limited knowledge of that branch of the service, and had, besides, no experienced military engineer to assist him. Many changes, it was apparent to General Beauregard, were necessary, and he determined to effect them as soon as circumstances should permit.

It may not be out of place to mention here some of the defensive works constructed under General Pemberton's orders.

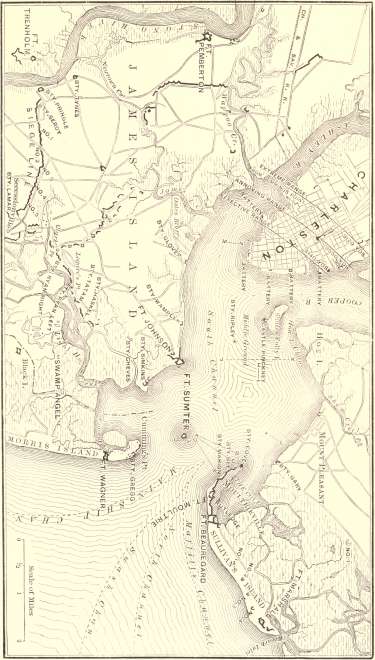

He had adopted a line from Secessionville, on the east, guarding the water approaches of Light-House Inlet, to Fort Pemberton, up the Stono River—a distance of fully five miles&mash;thus giving up to the enemy, for his offensive operations, a large extent of James Island. General Beauregard subsequently reduced that long and defective line to two and a quarter miles, from Secessionville to Fort Pringle, on the Stono, four miles below Fort Pemberton. This was not only a much shorter line, but a stronger and more advantageous one, as it greatly reduced the space the enemy could occupy in any hostile movement from the Stono.

In the defensive line originally constructed by General Pemberton the infantry cover had been put in front of his redoubts and redans, and the redans were before the redoubts; so that, when the lines were held by the infantry, the guns of the redoubts and redans could not be used, as the country there was perfectly level on all sides. Again, the redans, being in front of the redoubts, masked the fire of the latter&mash;thus completely reversing Rogniart's system of field-works, which requires that redans should be in rear of and between redoubts, and the infantry cover in rear of both&mash;thus leaving the artillery fire free, and the infantry in supporting distance, unexposed, and ready, if required, to repel any assault made upon the works.

On Morris Island, south of Sumter, an important position, a small open battery was commenced, distant about three-quarters of a mile south of Cummings's Point, and a mile and a half from Fort Sumter. It ran from the sea to Vincent Creek, on a very narrow part of the island, but had no guns bearing on the outer harbor, or ship-channel, as it was called. General Beauregard had that work considerably enlarged, gave it a bastioned front, closed its gorge or rear, added enormous bomb-proofs and traverses to it, and mounted several heavy guns pointing to the sea, or outer harbor. Indeed, he made it so strong that it successfully withstood, during some fifty-eight days, the heaviest land and naval attacks known in history.

On Sullivan's Island, north of Sumter, was old Fort Moultrie, and half a mile east of it Battery Beauregard, planned by General Beauregard and by him ordered to be built, as early as April, 1861. There were also three or four other batteries, west of Moultrie, some of which had taken a part in the attack on Fort Sumter at the opening of the war. A small work had likewise been commenced by General Pemberton on the extreme east of the island, which General Beauregard afterwards increased considerably, building besides four detached batteries between it and Battery Beauregard, to prevent a landing of the enemy's force in that quarter, though the danger of such an occurrence was much less than on Morris Island, in front of which was a good roadstead, where the Federal fleet lay till the end of the war.

See General Beauregard's report of the defence of Morris Island in July, August, and September, 1863.

In his first conference with General Pemberton, General Beauregard learned, with surprise and regret, that the system of coast defences he had devised in April, 1861, had been entirely abandoned, because of the anticipated attack of Federal monitors and ironclads, not yet completed; and that an interior system of defences, requiring much additional labor, armament, and expense, had been adopted, which opened many vulnerable points to an energetic and enterprising enemy. And yet, incredible as it may appear, this is the system which an over-zealous admirer of General Lee, and a former member of his staff, General A. L. Long,

See, in vol.

i., No. 2, February, 1876, Southern Historical Society Papers, General Long's article,

entitled Sea-coast Defences of South Carolina and Georgia, page 103. has been injudicious enough to attribute—no less than the other defences of South Carolina—to that distinguished Confederate general and engineer. If it were not that the utter insignificance of General Long's unsubstantiated statements shuts them out from serious notice, we could easily point out many unpardonable errors into which he has fallen; but the mere recital of what General Beauregard accomplished after his arrival in that Department, and the production of evidence, not drawn from imagination but from facts in its support, will satisfy the reader's mind and amply meet the requirements of history.

General Thomas Jordan, the able chief of staff, who so faithfully served in that capacity under General Beauregard from the first battle of Manassas to the latter part of April, 1864, has forcibly exposed what he very aptly terms “the wholly erroneous and wrongful conclusions” of General Long in regard to the sea-coast and other defences of South Carolina and Georgia.We quote the following passage from his reply to General Long:

“Pemberton, as I have always understood, had materially departed from General Lee's plan of defensive works for the Department. Be that so or not, the system which Beauregard found established upon the approaches to Charleston and Savannah he radically changed with all possible energy. * * * And so comprehensive were these changes that, had General Long chanced to visit those two places and the intermediate lines about the first day of July, 1863, he would have been sorely puzzled to point out, in all the results of engineering skill which must have met and pleased his eyes in the Department, any trace of what he had left there something more than one year before.”*

General Jordan's letter to the Rev. J. W. Jones, in vol. i., No. 6, June, 1876, Southern Historical Society Papers, page 403.

But General Long clung to his error. Instead of acknowledging the injustice he had committed, he wrote and forwarded to the Southern Historical Society Papers a second article, wherein, after declaring his intention not to recede from his former statement, he ventures upon the following extraordinary assertion:

“It is well known that after being battered down during a protracted siege, Fort Sumter was remodelled, and rendered vastly stronger than it had previously been, by the skilful hand of General Gilmer, Chief of the Confederate Engineer Corps, and that various points were powerfully strengthened to resist the formidable forces that threatened them.”

General Long's second article, Southern Historical Society Papers, vol.

II., No. 1, July, 1876, p. 239.

This stress laid upon Fort Sumter shows General Long's narrow appreciation of the subject. But as to Fort Sumter itself, General Gilmer had nothing to do with the remodelling of its battered walls, nor with the preparation and strengthening of the defences in and around Charleston and its harbor; nor has he ever made any such claim. The fact is, that he only reported for duty in that Department about the middle of August, 1863, shortly before the evacuation of Morris Island, which occurred on the 7th of September. At that time the works in South Carolina and Georgia were already planned, and in process of construction, almost all of them being entirely completed. General Gilmer was an educated Engineer, doubtless worthy of the rank he held in the Confederate service; and no one denies that, had General Lee been sent to Charleston, in the fall of 1862, instead of General Beauregard, he would have been equal to the task laid out before him. What is alleged is—and the proof in support is derived from the unvarying testimony of facts—that it was General Beauregard, and not General Lee, who conceived and built the “impenetrable barrier”, which, as General Long truthfully says, defeated the plans of “the combined Federal forces operating on the coast” of South Carolina and Georgia.

General Long had forgotten that General Beauregard was the first Confederate general sent to Charleston, and that he was, in fact, at that time, the only Confederate general in existence; that after he had taken Fort Sumter, and while it was being rehabilitated, he made, as early as 1861, by request of Governor Pickens, a thorough reconnoissance of the South Carolina coast, from Charleston to Port Royal; that he recommended, in a memoir written to that effect, the erection of important works at the mouths of the Stono, the two Edistos, and Georgetown Harbor.* For further details on this subject see Chapter V. of this book. But General Long further fails to remember that the different points he mentions as having particularly fixed General Lee's attention?the “most threatened points”—when he (December, 1861) assumed command of the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida (namely, the Stono, the Edisto, the Combahee, Coosawhatchie, the sites opposite Hilton Head, on the Broad, on the Salkahatchie, etc.) were not, after all, the points actually attacked by the united land and naval forces of the enemy—were not the sites of the “impenetrable barrier” against which the combined efforts of Admiral Dahlgren and General Gillmore were fruitlessly made. The real barrier that stopped them, and through which they could never break, consisted in the magnificent works on James, Sullivan's, and Morris Islands, and in different parts of the Charleston Harbor, and in the city proper—all due to the engineering capacity of General Beauregard, who conceived and executed them.

Unreflecting friends are worse at times than avowed enemies. They often belittle instead of elevating the object of their predilection. Groundless and fanciful praise of this kind could only lead to doubt of their subject's claim to merit in other matters, even where it is a just one. General Lee's reputation rests upon a more solid foundation than such formal eulogies, and he needs no borrowed laurels. The attempt of General Long to deprive General Beauregard See General Beauregard's letter to that effect, Appendix to this chapter. of his due in this instance is certainly not justifiable.

Before relieving General Pemberton, General Beauregard called on him for an estimate of the minimum forces, of all arms, in his opinion essential for a successful defence of Charleston and its dependencies, of the District of South Carolina, of Savannah and its dependencies, and of the District of Georgia.

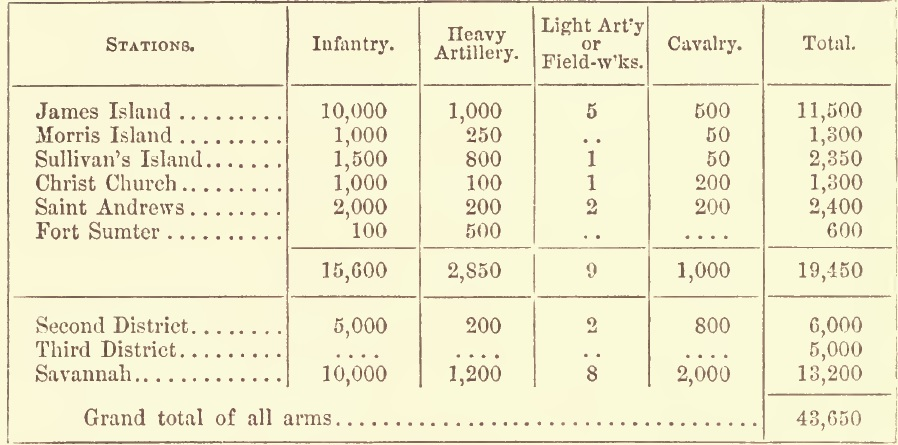

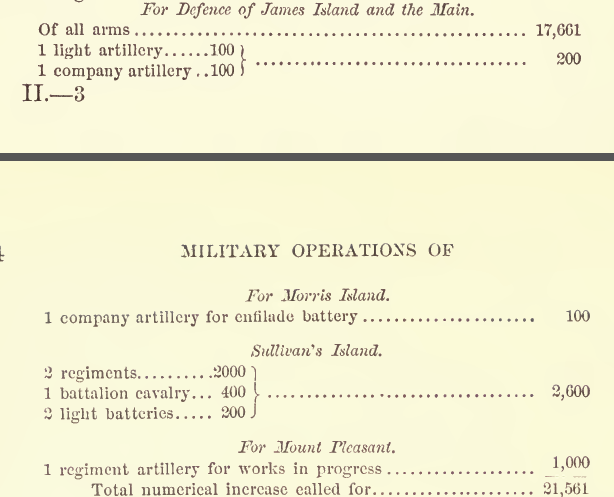

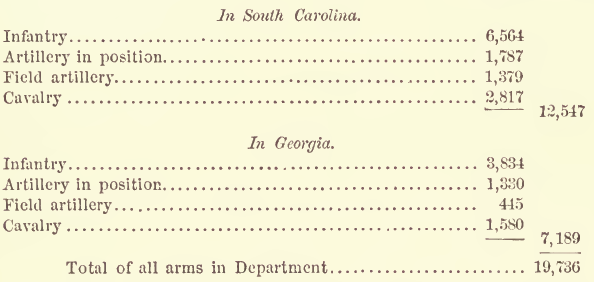

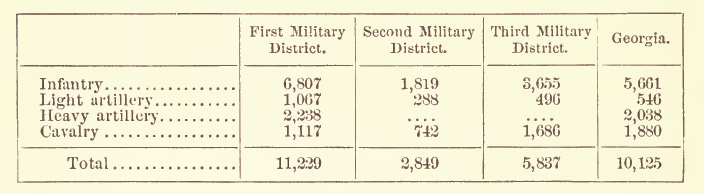

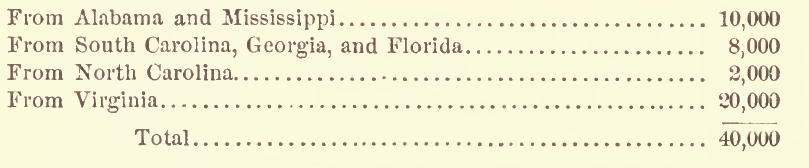

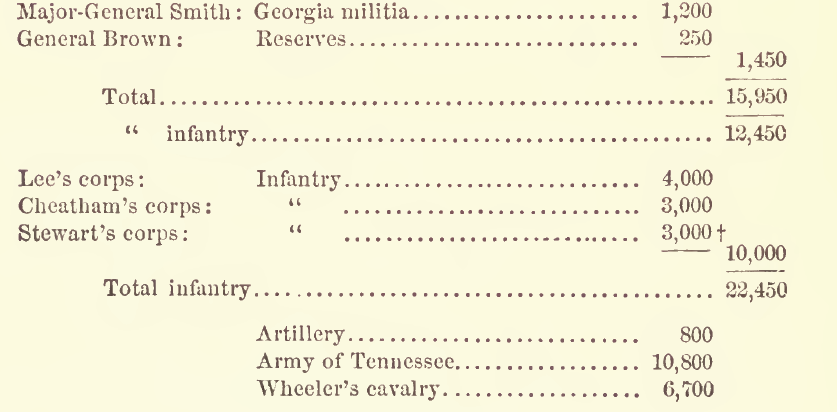

This was the estimate furnished. It bore date September 24th, 1862:

Seven companies of cavalry, three batteries of artillery, and three companies of infantry, for the defence of Georgetown and Winyaw Bay, and to prevent marauding, were also mentioned in General Pemberton's estimate.

See General Pemberton's letter, in Appendix to this chapter.

General Beauregard adopted this estimate as a basis for his future calculations, and on that day assumed command in an order which ran as follows:

“Headquarters, Dept. S. C. & Ga.,

Charleston, Sept. 24th, 1862.

“I assume command of this Department pursuant to Paragraph XV., Special Orders No. 202, Adjutant and Inspector-General's Office, Richmond, August 29th, 1862. All existing orders will remain in force until otherwise directed from the headquarters.

“In entering upon my duties, which may involve at an early day the defence of two of the most important cities in the Confederate States against the most formidable efforts of our powerful enemy, I shall rely on the ardent patriotism, the intelligence, and unconquerable spirit of the officers and men under my command to sustain me successfully. But to maintain our posts with credit to our country and our own honor, and avoid irremediable disaster, it is essential that all shall yield implicit obedience to any orders emanating from superior authority.

“Brigadier-General Thomas Jordan is announced as Adjutant and Inspector-General, and Chief of Staff of the Department.

“G. T. Beauregard, General Commanding.

“Official.

“Thomas Jordan, Chief of Staff, and A. A. G.

“Official.

“J. J. Stoddard, A. D. C.”

General Pemberton was regularly relieved on the same day, and, in obedience to orders, repaired to Richmond, where, shortly afterwards, he was made a lieutenant-general, and, to the astonishment of all men, even the President's own partisans, sent to take command of the Department of the Mississippi, with headquarters at Vicksburg, one of the most important posts in the South.

General Pemberton, as was well known, had not been engaged in any of the battles or actions of the war. He had not been under fire, and was looked upon not only as a new man but as an officer of little merit. He had accompanied General Lee to the Department of South Carolina and Georgia, with the rank of brigadier-general, and had succeeded him some time in December, 1861, receiving additional promotion soon afterwards, for he was made a major-general in January of the following year. Thus, in scarcely more than a year, and merely because he enjoyed the support of the Administration, General Pemberton, who was only a colonel when he joined the Confederate service, became first a brigadier-general, then a major-general, and then again a lieutenant-general, over the heads of many Confederate officers who had already distinguished themselves, and given unquestioned evidence of capacity, efficiency, and other soldierly qualities.

As soon as he had sufficiently familiarized himself with the condition of his Department, which was divided into four districts? South Carolina having three, and Georgia one?General Beauregard determined to bring the question of the defence of Charleston and its harbor before a council, composed of the principal military and naval officers who had long been stationed there. His object was, not only to gain enlightenment, but to create self-confidence in those officers, and increase their importance in the eyes of their subordinates. He prepared a series of questions, which were officially submitted to them, and thoroughly discussed at his headquarters. The conclusions arrived at were as follows:

“In the Office of the General Commanding the Department, Charleston, Sept. 29th, 1862.

“At a conference to which General Beauregard had invited the following officers; Com. D. N. Ingraham and Capt. J. R. Tucker, C. S. N., Brigadier-Gen'ls S. R. Gist and Thos. Jordan, Cols. G. W. Lay, Inspector-Genl., and A. J. Gonzales, Chief of Artillery, and Capt. F. D. Lee, Engrs., Capt. W. H. Echols, Chief Engineer, being absent from the city:

“The Genl. Commanding proposed for discussion a number of queries, prepared by himself, in relation to the problem of the defence of the Harbor, Forts, and City of Charleston, against the impending naval attacks by a formidable ironclad fleet.

“It was agreed to separate the consideration of these questions, so as to discuss—

“1st. The entrance, i. e., all outside of a line drawn from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter; thence to Cummings's Point, including, also — outside of this line — Battery Beauregard, at the entrance of the Maffit Channel.

“2d. The Gorge, i. e., the section included between that line and the line of a floating boom from Fort Sumter, to the west end of Sullivan's Island.

“3d. The Harbor, comprising all of the bay within the second line.

“4th. The City, its flanks and rear.

“In the discussion no guns were classed as heavy, if not above the calibre of 32, except rifled 32-pounders.

“The following conclusions were arrived at:

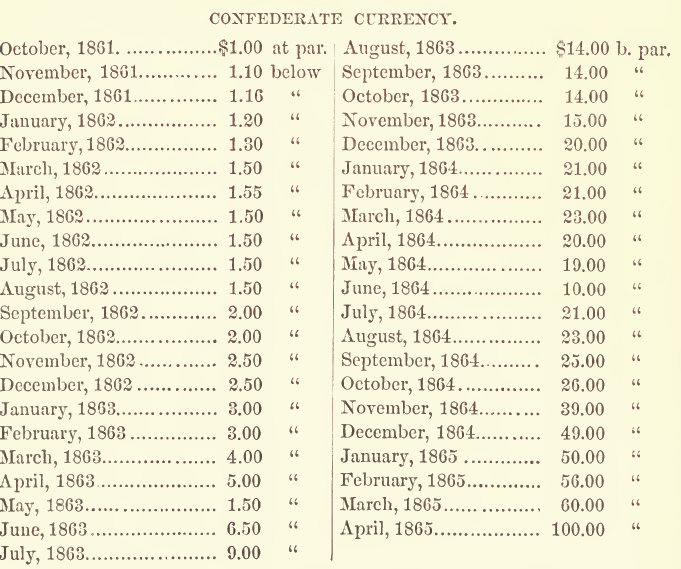

“1st. The existing defences of the entrance are: Beauregard battery, with two heavy guns; Fort Moultrie, with nine; the Sand Batteries on the west end of Sullivan's Island, with but four yet mounted; and Fort Sumter, with thirty-eight.

“Of the Gorge, say nine guns in Fort Moultrie, thirty-two in Fort Sumter (not including seven 10-inch mortars), and as yet but four in the Sand batteries.

“Of the Harbor, say fourteen guns of Fort Sumter, and the four guns in the new Sand batteries. Fort Johnson has one rifled 32-pounder, but it is not banded, and is unsafe.

“For the City defence, some batteries have been arranged and commenced, but heavy guns are neither mounted nor disposable.

“2d. The floating boom is incomplete.

“3d. It is no barrier now.

“4th. The boom, even if completed on the present plan, might be forced, although it would serve as a check, but it cannot be depended upon, if attacked by the enemy on a scale commensurate with his means. It has already been broken in parts by the force of the tides and currents. On account of its having to bear the strain of the depth of water (up to 70 feet) and the difficulties of the anchorage ground, of the limited means at disposal in anchors and chains, the indifferent quality of the iron, and the deficient buoyancy of the whole (the pine being green and sappy and getting heavier with time), a modification of the construction is required.

“5th. We have no means or material at hand for the construction of a better boom. It is thought, however, that the one now under construction will be materially improved by discarding the continuous chain of bar and railroad iron and links; and by linking together the logs, as they are now arranged, by short chains, so as to make a continuous chain of each section of the spars, there will be a saving of iron and greater buoyancy attained by this.

“6th. A rope barrier has been devised and constructed to place in advance of the spar-boom, but has not been placed in position, as the rope will rot in the water, and some anchors are still wanting. They are being searched for.

“7th.

Ironclads in forcing the harbor must pass the gorge or throat everywhere within point-blank range of our batteries, and must consequently be in great danger of damage from the concentration of the metal that can be brought to bear upon them, especially from the elevation of Fort Sumter.

“Note. — Distance between Sumter and Moultrie, 1775 yards; air-line of obstruction, 1550 yards.

“8th. The plan of naval attack apparently best for the enemy would be to dash with as many ironclads as he can command, say fifteen or twenty, pass the batteries and forts, without halting to engage or reduce them. Corn. Ingraham thinks they will make an attack in that way by daylight.

“9th. Ironclad vessels cannot approach or pass so close to the walls of Fort Sumter as not to be within the reach of the barbette guns. Those guns may be depressed to strike the water at a distance of 154 yards of the walls. Vessels of the probable draught of gunboats cannot be brought closer than 200 yards.

“10th. After forcing the passage of the forts and barriers, and reaching the inner harbor, gunboats may lay within 600 yards of the city face of Fort Sumter, exposed to the fire of about fifteen guns.

The magazines would be unsafe as now situated, or until counter-forts shall have been extended sufficiently along the city face.

“11th.

If ironclads pass the forts and batteries at the gorge or throat of the harbor, then the guns at Forts Ripley and Johnson and Castle Pinckney would be of no avail to check them. In consequence of the exposed condition of the foundations of Fort Ripley, and the general weakness of Castle Pinckney, it would not be advisable to diminish the armament of the exterior works to arm them; and this necessarily decides that Fort Johnson cannot be armed at the expense of the works covering the throat of the harbor. Fort Johnson must be held, however, to prevent the possibility of being carried by the enemy by a land attack, and the establishment there of breaching batteries against Fort Sumter. The batteries at White Point Garden, Halfmoon, Lawton's, and McLeod's, for the same reason, cannot be prudently armed at present with heavy guns.

“12th. The line of pilings near Fort Ripley is of no service, and is rapidly falling to pieces.

“13th. The city could not be saved from bombardment by any number of batteries along the city front, if the enemy reach the interior harbor with ironclads. It can then only be defended by infantry against landing of troops.

“14th. We have no resources at present for the construction of efficient obstructions at the mouth of, or in, the Ashley and Cooper rivers, and we have no guns disposable for the armament of interior harbor defences.

“15th. Should gunboats effect a lodgment in the harbor and in the Stono, the troops and armaments on James Island may be withdrawn, especially after the construction of a bridge and road across James Island Creek, about midway the island, near Holmes house. From the western part they can be withdrawn under cover of Fort Pemberton. McLeod's battery is intended to protect the mouth of Wappoo Creek, and Lawton's battery the mouth of James Island Creek, when armed.

“16th. With the harbor in the hands of the enemy, the city could still be held by an infantry force by the erection of strong barricades, and with an arrangement of traverses in the streets. The line of works on the neck could also be held against a naval and land attack by the construction of frequent and long traverses. The approaches thereto are covered by woods in front; possibly a more advanced position might have been better, though also protected by the woods, but so much has been done that it were best to retain the line, remedying the defects by long and numerous traverses.

“Two ironclad gunboats, carrying four guns each, will be ready for service in two weeks, as an important auxiliary to the works defending all parts of the harbor, and in that connection it will be important to secure for them a harbor of refuge and a general depot up the Cooper River as soon as the guns for its protection can be secured.

“G. T. Beauregard, Genl. Comdg.

“ D. N. Ingraham,

“Com. Comdg. C. S. Naval Forces, Charleston Harbor.”

That sketch of the situation, together with General Beauregard's Notes of Inspection, dated September 24th, and General Pemberton's minimum estimate of men and guns required for a proper defence of the Department, give so complete and correct a statement of its condition and needs, at that time, that we deem it unnecessary to add anything further.

On the day following this conference of officers General Beauregard began to carry out its conclusions, as to the armament of the different forts and the completion of the modified boom and rope obstructions in the main pass, between Forts Sumter and Moultrie. He determined also to make an extensive use of floating torpedoes for the defence of the harbors of his Department, particularly that of Charleston, which he placed in charge of Captain F. D. Lee, an efficient and energetic young officer, whose former profession had been that of civil engineer. The construction of the boom above alluded to was already under the superintendence of Doctor J. R. Cheves.

General Beauregard soon found that he would have to be his own chief-engineer, as the officers of that branch of the service he then had under him, although intelligent and prompt in the discharge of their duties, did not possess sufficient experience. He hastened, therefore, to apply for Captain D. B. Harris, who had been so useful to him in the construction of the works at Centreville, Va., and on the Mississippi River, from Island No.10 to Vicksburg, and who, he was sure, would greatly relieve him of the close supervision required for the new works to be erected, and the many essential alterations to be made in the old ones. His chiefs of artillery and of ordnance were also wanting in experience, but they soon came up to the requirements of their responsible positions, and eventually proved of great assistance to him. Not so with the officers in charge of the Commissary Department. These, in many instances, were not directly under General Beauregard's orders, but under those of Colonel Northrop, who, despite requests and remonstrances, continued to follow his own bent, which was to mismanage the affairs of his Department and set at naught the authority of generals commanding in the field or elsewhere. The worst feature of the case was that, in doing so, he invariably counted upon — and almost always obtained — the full support of the Administration.

The scarcity of iron just then was very great — so much so, that it became all but impossible to procure what was needed, not only for the construction of the boom across the main channel, but also for the anchors required to maintain it in position. At the suggestion of Governor Pickens, large granite blocks, collected at Columbia for the erection of the State House, were brought to Charleston, and used as substitutes for the anchors.* See, in Appendix, General Jordan's letter to Captain Echols, ChiefEn-gineer. The expedient proved quite a success, for a time, but the stone anchors could not long withstand the force of the tide.

General Beauregard now caused the following instructions to be given to his chief of ordnance:

“Headquarters, Department of S. C. And Ga.,

Charleston, S. C., October 1st, 1862.

“Major J. J. Pope, Chief of Ordnance, etc.:

“Major, — The commanding general instructs me to direct that the order of 25th ult. stands thus: That you cause the immediate transfer of the 10-inch, columbiad (old pattern), now in the Water Battery, to the left of Fort Pemberton, to Fort Sumter, with carriage, implements, and ammunition. Also that three 32-pounders, smooth, from Fort Sumter, and on barbette carriages, be moved to the said Water Battery, to the left of Fort Pemberton.

“You will likewise transfer to the new batteries, on Sullivan's Island, the 8-inch columbiad, now at Fort Johnson, with its implements, carriage, and ammunition, and report the execution of the foregoing.

“The 8-inch gun in Fort Ripley, and casemate 32-pounder in Fort Sumter, near Condenser, and the one on the wharf, referred to by you, will be assigned eventually to other positions.

“Very respectfully, your obdt. servt.,

“Thomas Jordan, Chief of Staff.”

Thus it appears that, immediately after his arrival in Charleston, General Beauregard began to concentrate as many heavy guns as were available in the first line of works, including Fort Sumter, so that they might be used with greater advantage against any naval attack. And the War Department was called upon to allow the transfer to Charleston of other heavy pieces from Ovenbluff, on the Tombigbee River, and Choctaw Bluff, on the Alabama River, where they could be of no use and might be easily dispensed with. The application was granted, provided no objection should be made by the commander of the Department of Alabama and Western Florida. No objection was made.

But General Beauregard's efforts did not stop there. He asked the War Department for additional guns, which he considered indispensable for the safety of Charleston, as he placed no great reliance upon the strength and stability of the boom then being constructed. His letter to Colonel Miles, M. C., Chairman of the Military Committee of the House (extracts from which are given in the Appendix to this chapter), fully explains his views on the subject. So do his communications, dated September 30th and October 2d, to General Cooper.*

See Appendix to this chapter.

The Northern newspapers were filled with indications of an approaching attack upon Charleston. The preparatory measures for such an expedition were represented as very formidable. Without entirely believing those rumors, General Beauregard used every endeavor to put himself in a state of readiness. He advised Governor Pickens, if it were the intention of the people and State to defend the city to the last extremity — as he was disposed to do — to prepare, out of its limits, a place of refuge for non-combatants. He ordered his chief-engineer to obstruct and defend the mouths of the Cooper and Ashley rivers. That officer was also instructed closely to examine both banks of the Stono, from Church Flats to the Wappoo Cut, and place there such obstructions as might impede the progress of the enemy, and prevent him from turning our works in that vicinity.

But the enemy, not being sufficiently prepared to make his projected attack on Charleston or Savannah, determined to strike a blow farther south, on the St. John's River, in the Department of Florida, commanded by Brigadier-General Joseph Finegan. General Finegan had only a small force under him, and, when he realized the extent of his danger, immediately telegraphed the War Department for reinforcements. The Secretary of War ordered General Beauregard to send two regiments of infantry to his assistance. They were to be withdrawn from Georgia, General Mercer's command. Although fears were still entertained of an offensive movement against South Carolina and Georgia, General Beauregard, whose forces were also very limited, complied promptly with the order, but took occasion to call the attention of the War Department to his numerical weakness, and to the fact that the enemy's lodgment in Florida, even if really intended — which was doubtful — would be of less gravity than an assault, at this juncture, upon either Charleston or Savannah. General Beauregard was accordingly authorized to recall his regiments, which he did without delay. They would have arrived too late to be of any assistance to General Finegan, as, upon that officer reaching St. John's Bluff, on the 3d, he found it already abandoned, though, in his opinion, there was a sufficient force to hold it, had Lieutenant-Colonel C. F. Hopkins, commanding the post, shown more spirit and determination.* A court of inquiry, held October 11, at Colonel Hopkins's demand, exonerated him, however, from all blame in regard to this matter. Six days later General Finegan informed the War Department that the enemy had embarked on their transports and gunboats, and were moving down the river.

Being much concerned about the security and efficiency of the boom which was being built in the Charleston Harbor,* A full description of it is given in General Beauregard's Notes of Inspection, to be found in Appendix to this chapter. General Beauregard ordered his chief-engineer to alter its construction so as to increase its floating capacity, and reduce the resistance it offered to the strong flood and ebb tides. He also instructed him to protect the pile foundations of Fort Ripley, which were exposed to view at low-water.

At that time he forwarded to the Adjutant-General's office at Richmond the official report of his inspection of the Department. It is entirely similar to the notes of inspection inserted by us in the Appendix to this chapter, and need not, therefore, be transcribed here. It had been somewhat hurriedly made, however, and did not include all the defensive points of the Department, nor was General Beauregard's criticism of the works visited so comprehensive then as at a later period, when based upon more thorough knowledge. The many and great alterations effected by him show how defective most of the works were, and how wellfounded were the concluding remarks of his report to General Cooper: “Adaptation ‘of means to an end’ has not always been consulted in the works around this city and Savannah. Much unnecessary work has been bestowed upon many of them.”

The Third Military District of South Carolina, with headquarters at McPhersonville, under Colonel (afterwards General) W. S. Walker, was not then in a very promising condition. Reports, considered trustworthy, indicated the enemy's early intention of taking the offensive in that quarter. The lines of defence and the detached works constructed in that district were calculated for the occupation of fully ten thousand men — the number assembled there during the preceding winter, with a proportionate artillery force. General Beauregard had had nothing to do in the establishment of these lines, nor had he either planned or recommended the erection of the works spoken of. The abandonment by the Government of the plan of defending the coast with heavy artillery, and the consequent reduction of the force thus employed to a corps of observation, chiefly of cavalry, rendered the greater part of these works useless. Colonel Walker was alive to the danger of such a state of affairs, and had addressed a communication to General Beauregard asking that reinforcements should be sent him to remedy the evil, and, as far as possible, secure that region of country.

See Colonel Walker's letter, in Appendix to this chapter.

General Beauregard's answer was as follows:

“Headquarters, Dept. S. C. and Ga.,

Charleston, S. C., Oct. 8th, 1862.,

“Col. W. S. Walker, Comdg. Third Mil. Dist., McPhersonville, S. C.:

Colonel, — Your letter of 3d instant, with its enclosures, has been received.

Your instructions to the Commanding Officer at Hardeeville and to your pickets are approved of; hone more in detail can be furnished you from here. Our means are so limited at present, that it is impossible to guard effectually the whole country and line of railroad, from here to Savannah, against a determined attack of the enemy; but we must endeavor to make up in zeal and activity what we lack in numbers. I shall, however, send you a light battery of artillery, to be posted by you wherever most advantageous. Being still unacquainted with the district of country under your command, I must rely greatly, in this and other corresponding matters, on your judgment and thorough knowledge of its topography. * * *

“Respectfully, your obdt. servt.,

“G. T. Beauregard, Genl. Comdg.”

The forthcoming chapter will show what occurred in Colonel Walker's district a fortnight after this letter was written. In the mean time it is proper here to remark that on General Beauregard's arrival in Charleston he found no regular system by which news of the movements of the enemy along the coast of South Carolina and Georgia could be ascertained with any degree of certainty, and he determined to correct so great a deficiency in the service, rendered all the more necessary by the fact that his Department, as will soon be seen, had just been enlarged. The system inaugurated may be thus explained: He established signal (flag) stations at the most important points along the coast of South Carolina (from Georgetown), Georgia, and Florida, where the enemy's ships or fleets could be observed. An exact register was kept in his office of all Federal vessels plying along the coast and their precise whereabouts. Whenever any change took place among them it was reported at once to Department Headquarters, and a minute account kept of it. And when an accumulation of the enemy's ships occurred at any point, indicating an attack, the small reserves General Beauregard had at Charleston or Savannah were prepared to move by rail in that direction, with the usual amount of provisions and ammunition, one or more trains being always held in readiness to receive the detachment. Thus was inferiority of number, to a certain extent, remedied by unremitting vigilance. The flag-stations above described communicated with the nearest railroad stations by sub-flag-stations, or by couriers, as circumstances required. The result was that clear and trustworthy information of the enemy's ships, or of his landforces, was given to General Beauregard, once in every twentyfour hours, from all the various quarters of his extensive Department. It is satisfactory to state that, during the twenty months he remained in command there, he was never, on any occasion, taken by surprise. His reinforcements always arrived at the threatened point as soon as our limited means of transportation would permit.

Chapter 27:

Extension of General Beauregard's command. Grave errors in the construction of the fortifications around Charleston. alterations ordered by General Beauregard. his desire for additional torpedo-rams. he foresees the Federal movement in Colonel Walker's District. Sends Captain F. D. Lee to Richmond. Prepares himself for the enemy's attack. bank of Louisiana. effort to save its funds. Secretary of War orders their seizure. instructions to General Ripley. memoranda on the defences of Savannah. minute instructions to General Mercer. suggestion for a conference of Southern Governors. Captain Lee's report of his visit to Richmond. attack of the Federals on Pocotaligo. Colonel Walker repulses them with loss. Federal force engaged in the affair. General Beauregard recommends Colonel Walker for promotion. estimate called for, and given, of men and material needed for a successful defence of Charleston and its Harbor.

From Richmond, on the 7th of October, the following telegram was sent to General Beauregard:

“Your command this day extended, in order to embrace South Carolina, Georgia, and that part of Florida east of the Appalachicola River. The camps of instruction for conscripts, in the several States, are under special control of the Secretary of War.

“S. Cooper, A. & I. G.”

This was not welcome news, for if it implied increase of territorial authority, it indicated no prospect of corresponding numerical strength in the Department. General Beauregard answered in these terms:

“Headquarters, Dept. S. C. And Ga.,

Charleston, S. C., Oct. 8th, 1862.

“General Samuel Cooper, Adjt. and Insp.-Genl., Richmond, Va.:

“General, — I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt, this day, of your telegram of the 7th instant, communicating information of the extension of the limits of this Department to include all of the State of Georgia, and so much of Florida as is situated east of the Appalachicola River. I beg to say that I trust this extension of the territory of the Department will be followed, at an early day, by a commensurate increase of the forces to guard it. It is proper for me to say, that the more urgent importance of the defence of the ports of Charleston and Savannah must necessarily occupy so much of my time, that I cannot be absent long enough to visit and make myself acquainted personally with the defensive resources and capabilities of Florida, and hence must rely entirely on the local commander.

“Respectfully, your obedient servant,

“G. T. Beauregard, Genl. Comdg.”

General Beauregard's solicitude was great for the safety of the approaches to Charleston. In the many works thrown up and directed by Engineers lacking experience grave errors had been committed, not only in their location but in their plans and profiles. Guns were put in position without regard to their range or calibre; traverses seemed to be ignored where most needed; enfilading fires by the enemy, the worst of all, had been almost entirely overlooked; yet one gun, well protected by traverses and merlons, is considered equivalent to five, unprotected. During the defence of Charleston, General Beauregard had all his heavy barbette guns surrounded with merlons and traverses, thus incasing them as if in a chamber. The bomb-proofs and service magazines, which he also placed in the traverses, protected the artillerists and, in doing so, materially increased their confidence, which was “half the battle.”

He had previously ordered the chief-engineer to enlarge the work at Rantowle's Station, on the Savannah Railroad, and to build a tete de pont and battery at the New Bridge, Church Flats. The same engineer had likewise been commanded to prepare a plan for the defence of the streets and squares of Charleston, in case of a successful land attack.

But General Beauregard's greatest efforts were directed towards the harbor. There, he was convinced, the land and naval forces against us would strike their heaviest blows. He wrote to Governor Pickens about his need of additional heavy guns; told him how little he relied on the effectiveness of the original boom; but spoke very encouragingly of Captain F. D. Lee's plan for a torpedo-ram, “which,” General Beauregard thought, “would be equivalent to several gunboats.” He added that “he feared not to put on record, now, that half a dozen of these torpedo-rams, of small comparative cost, would keep this harbor clear of four times the number of the enemy's ironclad gunboats.” *

See, in Appendix to this chapter, letter to Governor Pickens.

On the 10th he ordered a new work to be put up on the left of the “New Bridge, city side of the Ashley River, and to repair the battery at New Bridge,” Church Flats; and the chief-engineer was specially instructed as to the transfer and new location of guns already in position.

On the 12th he addressed this communication to Mr. J. K. Sass, Chairman of the State Gunboat Committee:

“Dear Sir, — In view of the necessity of getting ready, as soon as possible, the proposed torpedo-ram of Capt. F. D. Lee, and the difficulty, if not impossibility, of procuring the materials and machinery for its construction, I have the honor to request that the materials, etc., collected for the State's new gunboat should be applied to the torpedo-ram, which, I am informed, can be got ready sooner (in less than two months), will cost less, and be more efficacious, in my opinion. In other words, I think the State and the country would be the gainers by constructing one of these new engines of destruction, in place of the intended gunboat, now just commencing to be built.

“Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

“G. T. Beauregard, Genl. Comdg.”

The next day (13th) there were indications along the coast, especially about Port Royal, that the enemy would soon strike a blow in that vicinity. General Beauregard informed Colonel Walker, at McPhersonville, that every effort would be made to support him in case he was attacked; but that, nevertheless, it would be prudent for him to prepare himself for a retrograde movement, if overpowered. That he must therefore send to the rear all the heavy baggage, and hold his command ready for battle, with three days cooked rations, forty rounds of ammunition in boxes, and sixty in wagons. That his pickets must be on the alert and his spies actively employed. That reinforcements would be sent him as soon as required, but that he must indicate, with precision, the points most needing relief. That two thousand infantry would come from Charleston (General Gist's district), one thousand from the Second District (General Hagood's), and two thousand from Savannah (General Mercer's headquarters). And he was advised, furthermore, not to look upon General Mitchel as a very formidable adversary, but to prepare against his predatory incursions.

General Beauregard was now most anxious to have built a “torpedo-ram,” upon the plan proposed by Captain F. D. Lee. He accordingly sent that officer to Richmond to explain his invention, and urged the necessity of obtaining assistance from the War and Navy Departments. He considered those rams to be far superior to the ironclad gunboats of the enemy; was convinced that their cost would be one-third less, and that they could be constructed in a much shorter time than the crafts then being built in Charleston. General Beauregard informed the Government that the South Carolina authorities were highly in favor of the new ram, and had already appropriated the sum of $50,000 for its construction; but that, should the Navy Department take the matter in hand, the result would be better and sooner attained. If successful in Charleston harbor, General Beauregard thought similar rams could be built for the Mississippi and James rivers, and for Port Royal and Savannah. This point he strongly pressed upon the consideration of the War Department, and earnestly recommended Captain Lee for his zeal, energy, and capacity as a practical engineer.

Full and comprehensive orders were given, on the 13th and 14th, to Colonel Walker, and Generals Gist and Mercer, to hold their troops in readiness, with the usual instructions as to provisions and ammunition; and railroad transportation was prepared to take reinforcements to Colonel Walker at a moment's notice. On the same day General Mercer was also ordered to have made a careful reconnoissance of the Ocmulgee, with a view to its effectual obstruction and protection by a fort.

About this period a remarkable occurrence took place which is worthy of note. When New Orleans was about to be evacuated, in April, 1862, the civil and military authorities advised the banks and insurance companies to put their funds in security beyond the reach of the enemy. They nearly all did so, and, among them, the wealthiest of all, namely, the “Bank of Louisiana,” which sent its assets, mostly of gold and silver, to the extent of some three millions of dollars, via Mobile, to Columbus, Georgia, under the care of its president. These funds were given in charge by him to Mr. W. H. Young, President of the Bank of Columbus, Georgia, with the belief that they would there be perfectly safe. To General Beauregard's surprise, on the 11th of October the following telegram was forwarded to him from Richmond:

“Take possession of the coin of the Bank of Louisiana, in the hands of W. H. Young, President of the Bank of Columbus, Ga., and place it in the bands of John Boston, the depositary of the Government, at Savannah. A written order will be sent immediately, but don't wait for it.

“G. W. Randolph, Secy. of War. ”

Without loss of time, though very reluctantly, General Beauregard sent an officer of his staff, Colonel A. G. Rice, Vol. A. D. C., to execute this disagreeable order. On the 14th, from Columbus, Colonel Rice telegraphed as follows:

“ To Genl. T. Jordan, A. A. G.:

“Mr. Young, under instructions from Mr. Memminger, dated 9th of June, refuses to give up the coin. He has telegraphed to Richmond. No reply yet.

“A. G. Rice, A. D. C.”

Forcible possession, however, was taken of the coin; and the Secretary of War, when applied to for further instructions, ordered that, inasmuch as Mr. Young had been “appointed a depositary” by Mr. Boston, “the money be left in the hands of the former, upon his consenting to receipt for it as the depositary of the Treasury Department.” See telegrams, in Appendix. This Mr. Young declined to do; and thereupon General Beauregard was ordered by the Secretary of War to turn over the coin to Mr. T. S. Metcalf, Government depositary at Augusta, Georgia; which was done, Colonel Rice taking triplicate receipts, one for the Secretary of War, one for General Beauregard's files, and one for himself.

Thus was the property belonging to citizens of Louisiana, who were then despoiled by the enemy, in possession of their State, taken away from them by the Government of the Confederate States, from which they had a right to claim protection. What became of that coin is, we believe, even to this day, a mystery. It was, doubtless, spent for the benefit of the Confederacy; but how, and to what purpose — not having been regularly appropriated by Congress — has never been made known to the South, especially to the stockholders and depositors of the “Bank of Louisiana.” That institution was utterly ruined by the seizure of its most valuable assets, thus arbitrarily taken from it. It would have been more equitable to leave this coin untouched, or, if not, to take no greater proportion of it than of the coin of all the other banks in the Confederacy.

The movements of the Federals along the coast of Florida kept General Finegan in a state of constant perplexity, on account of the inferior force under him. On the 14th he gave a clear statement of the condition of his district, and asked that reinforcements should be sent him without delay. See, in Appendix to this chapter, his official letter to that effect. General Beauregard would gladly have complied with his request, but was unable to do so, as he was apprehensive at that time of an immediate attack at or near Pocotaligo, in Colonel Walker's district. He sent two officers of his staff, Lieutenants Chisolm and Beauregard, to confer with Colonel Walker as to the true condition of his command, and assure him again that he could rely on being reinforced as soon as the enemy further developed his intentions. Colonel Walker reiterated what he had already said about his weakness, and spoke of the want of rifles for his cavalry, which, he said, would have to fight as infantry, owing to the nature of the country in which the contest would probably take place. He designated Pocotaligo, Grahamville, and Hardeeville as points for concentrating his forces and reinforcements, according to circumstances and to the plan of the enemy, detailing his preparatory arrangements for meeting his adversary at any of the three places.

While these events were occurring — to wit, on the 17th of October — General Beauregard received a despatch from the Secretary of War, informing him that news from Baltimore, reported to be trustworthy, spoke of an attack upon Charleston by Commodore Dupont within the ensuing two weeks. General Beauregard communicated the rumor to Commodore Ingraham and to the Mayor of the city, Mr. Charles Macbeth, in order that he and the people of Charleston might be prepared for such an event. General Beauregard also instructed Doctor Cheves, in charge of the harbor obstructions, to hurry the laying of the “rope entanglement” in front of the “boom,” in the efficacy of which he now had but little, if any, faith.

It may be added here that when General Beauregard assumed command of Charleston he found prevalent among a certain class of people the habit of spreading exaggerated reports of the enemy's intended movements against the city. To put a stop to the uneasy state of excitement thus created, he ordered the various officers in command to obtain the names of all persons propagating such rumors, and, after tracing them to their original source, to arrest forthwith whoever was guilty of thus disturbing the public mind. In less than two weeks time, and before three arrests had been made, the habit was broken, and from that time forward no more trouble was experienced on this score.

General Beauregard's attention had already been attracted to the construction, or rather completion, of a railroad from Thomasville, Georgia, to Bainbridge, on Flint River, some thirty-six miles, and a branch from Grovesville to the Tallahassee Railroad — about sixteen miles — which would add greatly to the military facilities for the defence of Middle and Eastern Florida, and for sending troops rapidly from Savannah or the interior of Georgia to any point threatened in Florida. The matter was again referred to him, on the 18th, by Judge Baltzell, and he strongly advised the Government to take immediate action in regard to it; but scarcity of iron, it was alleged, and other reasons, not well explained, prevented the construction of either of the roads until the last year of the war, when, it seems, the project was finally sanctioned, but too late to accomplish any good.

Shortly after his arrival in Charleston, General Beauregard, at the suggestion of some of the leading men of the city, called for and obtained the services of Brigadier-General R. S. Ripley. He was a graduate of West Point, and an officer of merit, though erratic at times, and inclined to an exaggerated estimate of his own importance. He was, however, quick, energetic, and intelligent, and, for several months after his assignment to duty in the Department, materially assisted the general commanding in the execution of his plans.

On the 19th General Beauregard, through his chief of staff, gave General Ripley the following instructions:

“As the enemy has shown a design to interrupt or prevent the erection of any works at Mayrant's Bluff, the Commanding General directs me to suggest that the enemy may be foiled by proper efforts.

“Sham works should be attempted at some point in view of the gunboats, and, meanwhile, the real works should be vigorously prosecuted at night.

“It is likewise the wish of the General Commanding that Sullivan's Creek should be effectively obstructed, without delay, against the possible attempts of mortar-boats.

“Some arrangements must also be made for the disposition of the troops on Sullivan's Island, not needed for the service of the batteries, in case of an attack merely by gunboats. To this matter the Commanding General wishes you to give your immediate attention.

“The houses on Sullivan's Island, on the sea-shore, you will take measures to remove at an early day.”

We now have before us two important and interesting memoranda, giving an elaborate professional criticism of the defences of Savannah and its different approaches, showing the defects of the system adopted by General Beauregard's predecessor, and demonstrating clearly General Long's error of judgment in attributing the construction of these works — or most of them — to General R. E. Lee. The reader will find these memoranda in the Appendix to this chapter. We insert here the instructions given by General Beauregard to General Mercer, after his second tour of inspection of the defensive works at or around Savannah; they form a necessary supplement to the memoranda just spoken of:

“Savannah, Ga., Oct. 28th, 1862.

“Brig.-Genl. H. W. Mercer, Comdg. Dist. of Georgia, etc., etc.:

“ General, — Before leaving, on my return to Charleston, I think it advisable to leave with you a summary of the additions and changes I have ordered to the works intended for the defence of this city, and which ought to be executed as promptly as practicable, commencing with those on the river and at Caustine's Bluff:

“1. The magazines of several of the river batteries must be thoroughly drained at once, and repaired. They are now unfit for use, on account of their dampness, and the one at Battery Lawton has not yet been commenced. The position selected for it is too far to the rear. It should be closer to the battery, and well drained. Not a moment should be lost in its construction.

“The service magazine should have its entrance enlarged and strengthened at the top. The magazine doors at Fort Jackson do not open freely. This defect must be corrected.

“2. Good and strong traverses must be constructed, as directed, in the Naval Battery, to prevent enfilading.

“3. The two 8-inch columbiads on Fort Jackson must be separated, and one of the barbette 32-pounders (removed, for a traverse to be constructed in its place) must be put in position outside, in rear of the glacis, to fire down the river.

“4. Those river works, when garrisoned, must always be provided with several days' provisions on hand.

“5. The mortar-chamber in Capt. Lamar's battery is too small. The mortars should be mounted as soon as practicable, and the men drilled to it.

“6. It would be important, if possible, to lay a boom obstruction across the river, at or near Hutchinson's Island, under the guns of its battery, and of Fort Boggs, and a three or four gun battery should also be constructed at Screven's Ferry Landing.

“7. Caustine's Bluff must be made an enclosed work, with two mortars and four heavy guns added to its armament. Two of these guns must be placed so as to bear up the Augustine River.

“8. A three-gun battery must be constructed at Greenwich Point, on Augustine River, to cross fire with the two guns just referred to, on Whitmarsh Island, constructed against Caustine's Bluff.

“9. One rifled 32-pounder must be added to the Thunderbolt Battery, and one of its 8-inch shell-guns must be changed in position, as ordered, and the embrazure of its 8-inch columbiad must be reduced in size.

Several traverses must be raised and lengthened. The upper slope of the battery in front of several of its guns must be increased.

“10. A new battery for four 24-pounder howitzers, on siege-carriages, with some rifle-pits, must be constructed to command the Isle of Hope Causeway.

“11. Several of the guns of Fort Boggs and battery at Beaulieu are in want of elevating screws; and some in the latter battery require smaller trunnion-plates, and the upper slope of its parapet must be lowered in several places.

“12. A new battery and rifle-pits must be constructed on Rosedew Island for five or six pieces, of which one or two should be rifled guns, so as to command Little Ogeechee.

“One rifled 24-pounder is already on its way to this city from Atlanta for said work.

“13. Two rifled guns (one 32-pounder and one 24-pounder) must be added to the work on Genesis Point, and one of its 32-pounders must be changed in position, as ordered, to rake the pilings across the river. Its traverses must be raised and lengthened, and a merlon constructed to protect the two 32-pounders, now raking the obstruction, from being enfiladed.

Its magazines must be better protected, and its hot-shot furnace reconstructed as ordered. A more efficient commander than the present one would, I think, be required for this important position, and whoever is sent there should visit, first, the work at Beaulieu, to see its fine condition.

“14. A proper sunken battery should be constructed for the protection of the men and horses of all light batteries intended for the defence of watercourses. This applies especially to the light batteries now on the Little and Great Ogeechees.

“15. No provocation of the enemy's gunboats, to draw the fire of our batteries, should induce officers in command to waste in return their ammunition. They should reserve their fire until the enemy comes within pointblank range of a 32-pounder, placing, meanwhile, all the garrison under close cover. When they fire let them open simultaneously with all their guns upon the foremost vessel, in order to sink it, aiming rather low.

“16. Two mortars have been ordered from Charleston for Fort Jackson and Caustine's Bluff, to fire on river obstructions, and, in respect to the latter battery, to fire also on Whitmarsh Island. They must be placed in position as soon as they shall have arrived, and provided with ammunition, etc., and a detail of men drilled at them regularly.

“17. Ship-yard Creek, in rear of Beaulieu, must be guarded by a light battery, as already indicated for the Little and Great Ogeechees.

“18. Signal-stations must be established forthwith to communicate with each other at Genesis Point, Rosedew Island, Beaulieu, the Isle of Hope Causeway, Thunderbolt, Caustine's Bluff, Fort Jackson, Fort Boggs, and the city.

“19. The two large observatories or spindles towards the mouth of Savannah River must be destroyed forthwith, for fear of their falling into the hands of the enemy uninjured.

“20. Brigade drills must be commenced at once, whenever practicable, and regiments must not be armed with weapons of more than two different calibres, to prevent confusion in providing them with ammunition.

“21. The male residents of this city, not liable to conscription, must be organized at once by the civil authorities, for the defence of their homes and firesides (in case of an attack upon the city), into companies and regiments. They will thus afford material assistance to the Confederate troops in the defence of Savannah.

“22. Ample provision must be made by the civil authorities for the removal of the women and children to a safe locality outside of the city-the farther the better. This removal should take place on the first appearance of real danger.

“23. A sufficient number of switchlock keys should be provided at railroad depots for immediate use in case of necessity.

“24. The Georgia Central Railroad will furnish a reserve train, to be stationed at Ashley River Depot, for the purpose of conveying troops, without delay, from Charleston to the South Carolina lower parishes, or to Georgia. Another one will be held in readiness at the depot of the Central Railroad, in this city, for the purpose of conveying troops towards Charleston when required.

“25. The troops of this district must be vaccinated gradually.

“26. The woods of the island fronting the outworks must be cut down as soon as possible, wherever in too dangerous proximity.

“27. The city must be always provided with at least fifteen days provisions for ten thousand men, and with the same quantity in a convenient depot not nearer than thirty miles from the city, along the Central Railroad, so as to be beyond the reach of the enemy in every contingency.

“28. Ample supply of fuel should be made for the steamboats and for the troops forming the garrison of the city.

“29. The city authorities must see that the supply of water be ample for all emergencies, in case of a bombardment.

“Respectfully, your obedient servant,

“G. T. Beauregard, Genl. Comdg.”

“P. S.—It is ordered that all laborers employed on the interior of the city lines of defences, except those employed on the magazines, should be at once concentrated, first on the salient faces of the advanced lunettes and cremailleres, except those from Fort Mercer, inclusive to Fort Brown, then on the salient faces of the retired lunettes or redans, then on the shoulder faces of the first class, and afterwards of the second.

“The banquettes of Fort Brown must be put forthwith in proper condition. No labor must be expended on the finish of the above works, which must be put, with their batteries, magazines, etc., in a fighting condition as soon as possible, even if we should have to work day and night.

“Should you not have laborers enough for such a purpose, you must call on the Governor of the State for additional ones. I earnestly request that the utmost activity should be shown in every department of the service, so as to be ready in time for an intended attack of the enemy. I have called for five 10-inch or 13-inch mortars, and twenty heavy or long-range guns (five 10-inch and five 8-inch columbiads, five 42-pounders, rifled, and five 32-pounders, ditto), which will be distributed to the best advantage, when received, on the river defences and line of outworks.

“G. T. B. ”

During his second tour of inspection in Georgia, General Beauregard had directed his thoughts, despite his preoccupation at the time, to a subject, not immediately concerning his military occupations, but referring to, and closely connected with, the ulterior fate of the Confederacy. Believing that our Government could not again directly open the door to peace negotiations with the Federal Government, and knowing, on the other hand, that our Confederate Commissioners in Europe had never been allowed to offer the semblance even of an inducement in our favor to any of the foreign powers, it occurred to him that what could not appropriately be done by the authorized agents of the Confederacy might perhaps be attempted, with some chance of success, by the governors of the Southern States. Acting upon this impulse, he wrote from Savannah, on the 21st of October, the following message to Governors Pickens, of South Carolina; Brown, of Georgia; and Milton, of Florida; and to Colonel William P. Miles, M. C., formerly a member of his staff:

“Why should not governors of Southern States offer to meet those of Northwest States, at Memphis, under flag of truce, to decide on treaty of peace to be submitted to both governments? ”

The moment, General Beauregard thought, was propitious for such a step; for the Confederacy, notwithstanding many reverses, was holding out with success; but though the suggestion was at first approved of by two of the three governors written to, it was not acted upon. Governor Pickens, upon reflection, decided that the plan was not feasible, and Colonel Miles was of opinion that nothing could be effected now, and that our only course was to “fight it out.”

At about the same time was received Captain F. D. Lee's report of his visit to the War and Navy departments, at Richmond, with reference to his torpedo-ram. He had been much encouraged by these two departments, by the chief-engineer and the chief of ordnance of the navy. All spoke in the highest terms of his invention. Unfortunately, he left Richmond without securing the necessary orders for the construction of his boat, and, as a consequence, many untoward delays ensued. In the Appendix will be found Captain Lee's report of his mission to the Confederate capital, and a letter from General Beauregard to the Hon. S. B. Mallory, in acknowledgment of his prompt and favorable support of the marine torpedo-ram project. In this letter he said:

“I confidently believe that with three of these light-draught torpedo-rams, and as many ironclad gunboat-rams, this harbor [meaning the Charleston Harbor] could be held against any naval force of the enemy ;” and he added: “The same means can also be used (with one less of each class) for Savannah and Mobile.” He disclaimed wishing to take the matter out of the hands of competent naval officers. “All I desired,” he wrote, “was to see it [the ram] afloat and ready, for action as soon as possible.” Time and the progress of naval warfare have only confirmed the opinion he entertained twenty years ago.

At last occurred, on the 22d, the long-expected attack of the Federals against Colonel W. S. Walker, at Pocotaligo and Coosawhatchie. General Beauregard was then in Savannah. So carefully were all his arrangements made in prevision of that occurrence, and so minute his instructions to his chief of staff in Charleston, that he did not forego his inspection of the defensive works in General Mercer's command. Still supervising the movements of the troops, he rapidly sent forward the reinforcements held in readiness for that purpose, and thus materially aided Colonel Walker in securing his brilliant victory.

The enemy, in some thirteen gunboats and transports, came up Bee's Creek, apparently aiming at Coosawhatchie. Effecting a landing at Mackay's Point, and marching thence in the direction of Pocotaligo, they took possession of the railroad at Coosawhatchie and destroyed the telegraphic line at that point, thus compelling us to communicate with Savannah and Hardeeville via Augusta.Colonel Walker now telegraphed for reinforcements, as was agreed, and retired to “Old Pocotaligo,” one mile from the Pocotaligo station, intending, if necessary, to fall back to the Salkahatchie bridge. This, however, he did not do, but took a fixed position at the junction of the Mackay's Point road and the road between Pocotaligo and Coosawhatchie. The engagement was then in full progress, the enemy's force being, at first, relatively small, but constantly increasing with the arrival of reserves. Colonel Walker was resolved to hold his ground at Old Pocotaligo until reinforcements should arrive, which he again telegraphed for, asking that all troops coming from Savannah should be sent to Coosawhatchie, and those from Charleston to Pocotaligo, as both points were being assailed in force.

The first reinforcements that reached the scene of action, at about 4.30 P. M., came up from Adams Run. They double-quicked to where the fight seemed heaviest, their presence giving additional resolution to Colonel Walker's gallant troops, and showing their commander that he could now count upon success. He was not disappointed. The enemy, after a contest that lasted from 11.30 A. M. to 6 P. M., gave way in disorder, leaving his dead and wounded on the field, with quite a number of small-arms, with ammunition, knapsacks, and other accoutrements. Two companies of cavalry were sent in pursuit, but could not be moved nearer than two miles to the Federal gunboats, which opened and kept up a destructive fire upon them.

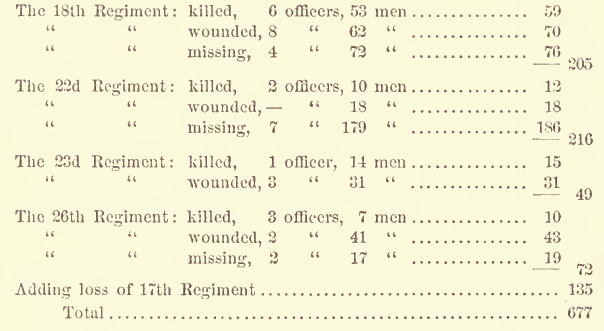

Our loss was small, though, in proportion, greater than that of the enemy, and amounted to an aggregate of one hundred and sixty-three, killed, wounded, and missing. The loss on the other side was estimated at not less than three hundred.

Uncertain, however, as to the ulterior object of the enemy, other troops were asked for by Colonel Walker; and Generals Hagood and Gist, with forces kept prepared for that purpose, were rapidly sent to reinforce him. They arrived after the action was over, and took no part in it, General Gist, with two strong regiments, only reaching Pocotaligo the next day, October 23d. It was now evident that no further assistance was needed.

The Federal force engaged in this affair consisted of six regiments, one battery of ten 10-pounder rifled guns, and two boat howitzers. Colonel Walker had, when he first went into the fight, about four hundred effective men of all arms, and was subsequently reinforced by the Nelson Battalion, under Captain Sligh, numbering two hundred men, making in all, towards the close of the fight, a total force of not more than six hundred men, against an aggregate of not less than three thousand five hundred on the part of the enemy. In his official report of the engagement Colonel Walker said:

“The force of the enemy was represented by prisoners, and confirmed by the statement of negroes who had crossed Port Royal Ferry to the mainland on that day and been captured, to be seven regiments, one of which, I judge, went to Coosawhatchie. * * * There were abundant evidences that the retreat of the enemy was precipitate and disordered. One hundred small-arms were picked up, and a considerable amount of stores and ammunition. The road was strewn with the debris of the beaten foe. Forty-six of the enemy's dead were found on the battle-field and road-side. Seven fresh graves were discovered at Mackay's Point. I estimate their total killed and wounded at three hundred. * * * We have ample reason to believe that our small force not only fought against great odds, but against fresh troops brought up to replace those first engaged. * * * I beg to express my admiration of the remarkable courage and tenacity with which the troops held their ground. The announcement of my determination to hold my position until reinforcements arrived seemed to fix them to the spot with unconquerable resolution.”

General Beauregard the day following informed the War Department of the defeat of the enemy at Pocotaligo; and, recognizing the coolness, intelligence, and foresight displayed by Colonel Walker on that occasion, strongly recommended him for immediate promotion. The War Department acceded to that request, and when, on November 4th, the official report of the fight at Pocotaligo reached Department Headquarters in Charleston, it was signed “W. S. Walker, Brigadier-General, Commanding.”

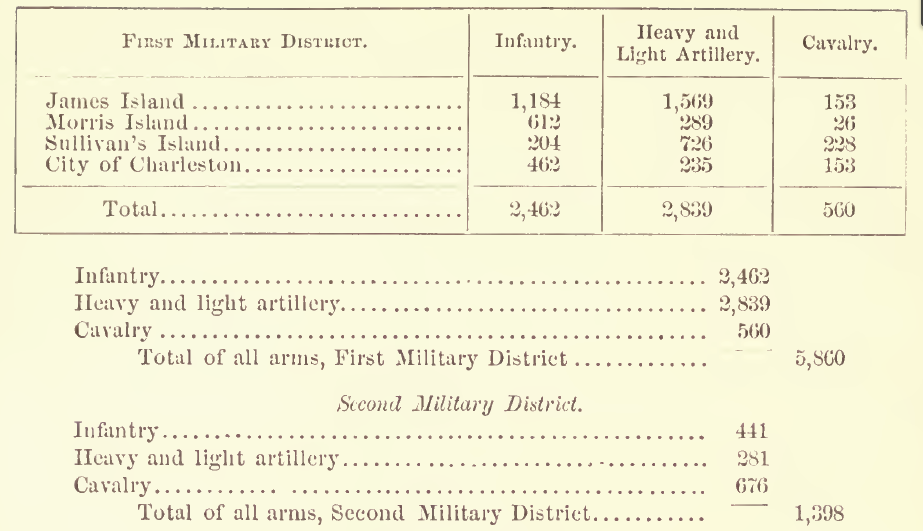

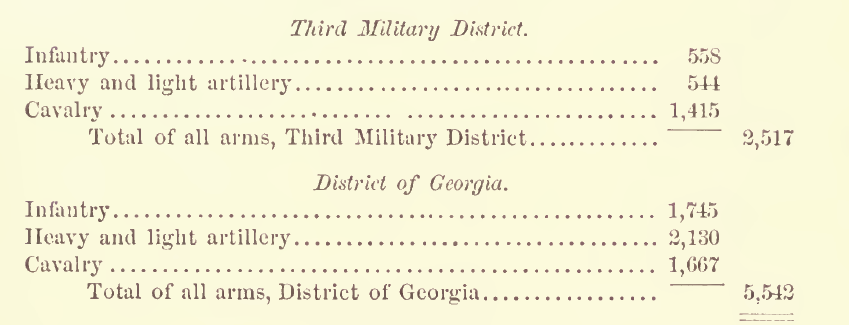

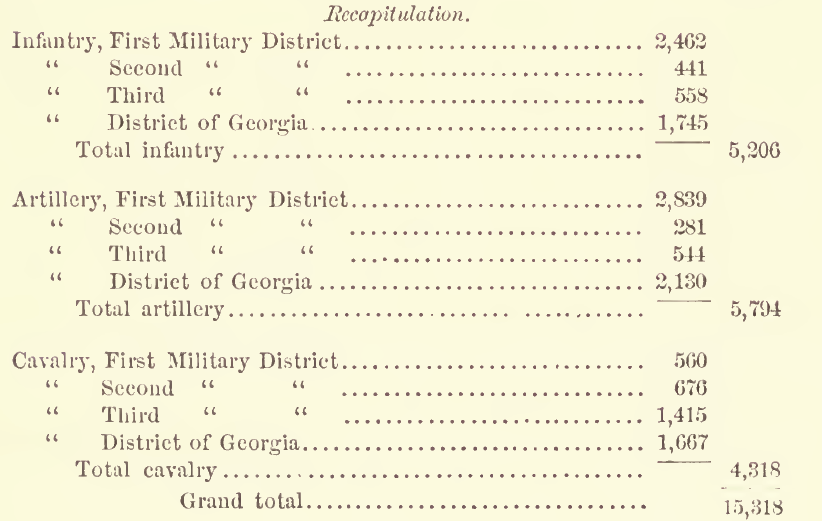

Our success at Pocotaligo, although very encouraging, more than ever demonstrated our numerical weakness, and led General Beauregard to reflect with great uneasiness upon the results which might follow a simultaneous attack by the enemy at various points in his Department. Hesitating to trust his judgment alone relative to the deficiency of troops in the First Military District, he called on its commanding officer for an estimate “of the men and material he thought necessary for a prolonged successful resistance to any attack which the resources of the enemy may enable him to make.”

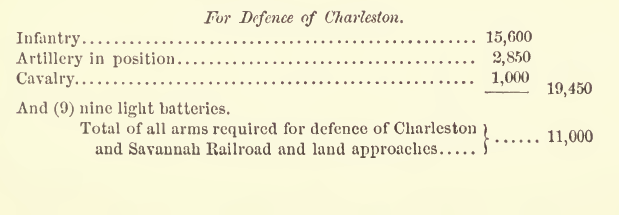

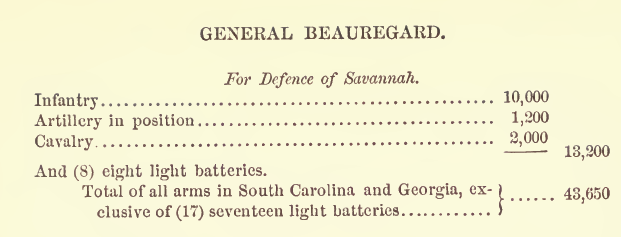

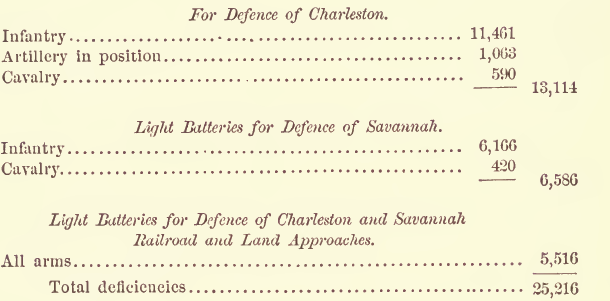

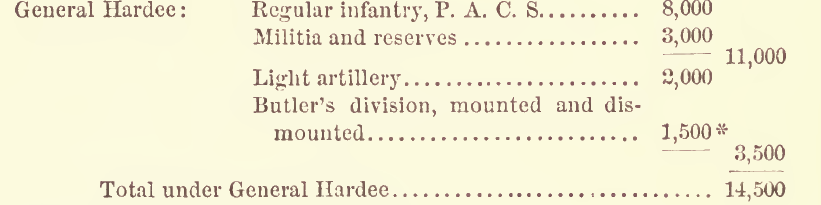

In compliance with this request, Generals Ripley and Gist, the commander and sub-commander of the district referred to, furnished the following report:

“Headquarters, First Military Dist., S. C., Charleston, Oct. 25th, 1862.

“Increase of numerical force called for by Brigadier-General S. R. Gist, commanding:

“Ripley, Brig.-Genl. Comdg.”