Louisiana Encyclopedia

Louisiana Encyclopedia

Micaela Leonarda Antonia Almonester, Baroness de Pontalba

by Joannie Hughes

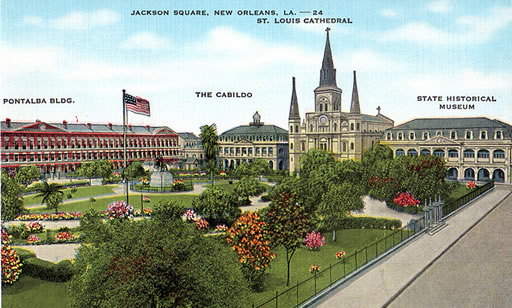

Micaela Leonarda Antonia Almonester, Baroness de Pontalba (November 6, 1795-April 20, 1874) was a member of one of the most illustrious Creole families in Louisiana. Her father died when she was only 2 years old — leaving her with his fortune which he obtained in real estate & politics. Prior to his death, he had commissioned architect Gilberto Guillemard to design and construct the St. Louis Cathedral, the Presbytere and the Cabildo, all of which line one side of Jackson Square (then known as Place de Armes). Very shortly after her father's death, Micaela's mother Louise married Jean Baptiste Castillon, a 25-year-old Frenchman. Her Mother was 40 years old. The huge difference in their ages caused a great scandal and much scorn amongst the people of New Orleans, who showed their displeasure by conducting a riotous charivari that lasted for three days and nights which even featured effigies of her new bridegroom and dead husband in his coffin. The charivari was only called off once Louise had promised to donate the sum of $3,000 to the poor.

|

|

St. Louis Cathedral in 1838

Public domain images at

Wikipedia.

|

Micaela was well educated by the nuns at the Ursuline Convent (situated on la Rue Conde, now Chartres Street). In keeping with Creole tradition, a marriage was arranged for Micaela in 1811 when she was fifteen. Although Micaela was in love with an impoverished man, she had no choice but to accept the husband her mother had picked for her. He was her 20-year-old cousin, Xavier Célestin Delfau de Pontalba, known as Celestin or "Tin Tin," who although born in New Orleans, lived with his family in France.

Sometime after the wedding, Micaela and Célestin, accompanied by both their mothers, left Louisiana for France. They arrived in July 1812 and the couple took up residence with Célestin's family at Mont-l’Évêque, the moated, medieval de Pontalba chateau outside Senlis which was about 50 miles from Paris.

At first the marriage was successful; Micaela became pregnant shortly after their arrival in France and eventually bore her husband a total of four sons and a daughter. To alleviate the boredom of country life, she converted a large room at the old chateau into a theatre where she put on plays. She put a lot of energy and enthusiasm into her project, ordering costumes for the performers and hiring local people for the minor roles and Parisian artists for the leading roles. She often performed onstage in the amateur theatrical productions which were attended by her friends from Paris.

However, the constant interference of her eccentric father-in-law eventually turned the marriage into a disaster which was made worse by the fact that Célestin possessed a weak, spoiled, effeminate character. Her father-in-law, Baron Joseph Delfau de Pontalba, was greedy and unstable, and over the years proceeded to make Micaela's life extremely unhappy and intolerable. The baron was already greatly disappointed with Micaela's dowry, considering it much smaller than he had been led to expect. The $40,000 plus some jewelry Micaela brought to Célestin as her dowry which had been the sum agreed upon when the marriage contract was drawn up, represented only one-quarter of her Almonester inheritance with the remaining three-quarters retained by Louise. The old baron, intent upon seizing the vast Almonester fortune, had forced Micaela into signing a general Power of Attorney giving her husband control over her assets, rents, and capital, both dotal, and as heir of her father. In the early 1820s, to escape the tyranny of her father-in-law, Micaela persuaded Célestin to set up his own household in Paris, and the couple and their children moved into one of his father's homes in the Rue du Houssaie close to her mother's residence.

|

|

The Baroness de Pontalba

|

The death of her mother in 1825 left Micaela as the sole recipient of her considerable estate which also included numerous properties in Paris. The de Pontalbas furiously demanded that she sign over all her New Orleans property to them in exchange for her being allowed to assume control of her mother's Paris houses. In 1830, without her husband's permission, she went to New Orleans for an extended visit, taking the opportunity to travel around other parts of the United States. She stopped in Washington DC where President Andrew Jackson sent his own carriage and secretary of state Martin Van Buren to bring her to the White House as his guest. It was rumored that they had a torrid affair while she was in Washington.

When she returned to France, the baron accused her of deserting Célestin; as a result she became a "virtual prisoner" of the de Pontalbas. In frustration, she took her children and transferred back to Paris where she began a series of lawsuits to obtain a separation from Célestin, but lost them due to the strict French marriage laws.

Micaela's attempts to protect her fortune and separate from Célestin so enraged Baron de Pontalba that he resorted to violence. On October 19, 1834, during one of her visits to the chateau, he stormed into her bedroom and shot Micaela four times in the chest at point-blank range with a pair of duelling pistols. After the first shot, she allegedly screamed out: "Don't! I'll give you everything". Whereupon he replied: "No, you are going to die" and shot her another three times in the chest, one bullet passing through the hand that she had instinctively put up to cover one of the gun's muzzles. Despite her injuries, Micaela made an attempt to escape her father-in-law and outside the door she fell into the arms of her maid who had rushed up the stairs upon hearing the first gunshot. With the armed baron still in pursuit, Micaela was dragged down the stairs to the drawing room where she fell to the floor, crying out, "Help me." Baron de Pontalba stood over her bleeding, unconscious body, yet he fired no more shots and returned to his study.

She survived the shooting attack, despite having been shot four times in the chest, with one of the bullets having crushed her hand. Her left breast was disfigured and two of her fingers mutilated. That same evening the baron, having never left his study, committed suicide by shooting himself in the head with the same pistols.

As Célestin had succeeded to his father's barony upon the latter's suicide, Micaela was henceforth styled Baroness de Pontalba. Eventually, after several more lawsuits, a civil law judge ordered the restitution of her property and Micaela was granted a legal separation from her husband; although they were not actually divorced. With some of the money her mother had willed her, she commissioned noted architect Louis Visconti to construct a mansion on the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris which she subsequently used to entertain lavishly, hosting an endless succession of balls, soirees, and parties. This mansion is known today as the H�tel de Pontalba and serves as official residence of the United States Ambassador to France.

In 1848 at the outbreak of revolution in France, Micaela, accompanied by two of her sons Alfred and Gaston, departed for her home of New Orleans, where she quickly became the leader of fashionable society. The wealthiest woman in New Orleans at the time, her contemporaries regarded Micaela as having been shrewd, vivacious, and business-like. Seeing New Orleans for the first time after an absence of many years, Micaela had immediately noticed that the once-stylish French Quarter had become derelict and unsightly. The Place d'Armes (Jackson Square), in the heart of the French Quarter, was little better than a slum; its parade ground muddy, and houses squalid and neglected. She owned most of the property in Place d'Armes as it formed part of her vast inheritance. Micaela put her imagination to work and made energetic plans to remedy the situation. She ordered the houses to be demolished and hired the skilled building contractor Samuel Stewart to renovate the Place d'Armes. The following year after obtaining an agreement from the city for a 20-year tax exemption, she personally designed and commissioned the construction of the beautiful red-brick town houses forming two sides of Place d'Armes which are today known as the Pontalba Buildings. The construction of the Pontalba Buildings cost more than $300,000 and she was a constant visitor to the construction sites, often supervising the work on horseback. She was very "hands-on" in supervising the construction of the buildings — visiting the site daily — dressed often in pants and boots and climbing the scaffeling to inspect the work being done. Her unlady-like fashion choices caused great scandal in a time when women only wore the most feminine of dresses. Women wearing pants were unheard of in those days and considered quite improper!

|

|

One of the Portalba Buildings.

Public domain photo at Wikipedia.

|

The cast-iron work decorating the balconies were another of her many her personal designs in the buildings and she had her initials "AP" carved into the center of each section — and they can still be seen today. Micaela knew so much about the design and construction of buildings that historian Christina Vella described her as a "genius in architecture". Andrew Jackson — whom she was still "very fond" of — scolded her many times for wearing pants, for being on the work site and for ordering the workmen about. He told her that she was not acting like a proper lady and that he would refuse to tip his hat to her (gesture of respect from men to women of those days) until she started behaving like a lady again. Micaela and her sons occupied the house at number 5 on the St. Peter Street side of the square — to the rear left if you are facing the square.

|

|

Historic Postcard of Jackson Square

Courtesy of John Olson, Flickr's Creative Commons.

|

Micaela was not to be out done. She financed the bronze equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson which stands in the very center of the square today — and had it built directly facing her apartment in the building — with Andrew Jackson tipping his hat directly at her balcony. She had very clear vision of what Jackson Square should look like. When she was landscaping the garden, she threatened the mayor with a shotgun after he tried to prevent her from tearing down two rows of trees.

Micaela Almonester de Pontalba died on April 20, 1874 at the age of seventy-eight, a legend in the city of her birth.

Louisiana Encyclopedia

Louisiana Encyclopedia