THE

village of Mandeville in the parish of St. Tammany,

Louisiana, is about twenty miles from New

Orleans on the north shore of Lake Ponchartrain. Here,

on the plantation of the same name, owned by the Marquis

de Mandeville de Marigny, John James Laforest

Audubon[1] was born, the Marquis having lent his home,

in the generous southern fashion, to his friend Admiral

Jean Audubon, who, with his Spanish Creole wife, lived

here some months. In the same house, towards the close

of the last century, Louis Philippe found refuge for a

time with the ever hospitable Marigny family, and he

named the beautiful plantation home "Fontainebleau."

Since then changes innumerable have come, the estate has

other owners, the house has gone, those who once dwelt

there are long dead, their descendants scattered, the old

landmarks obliterated.

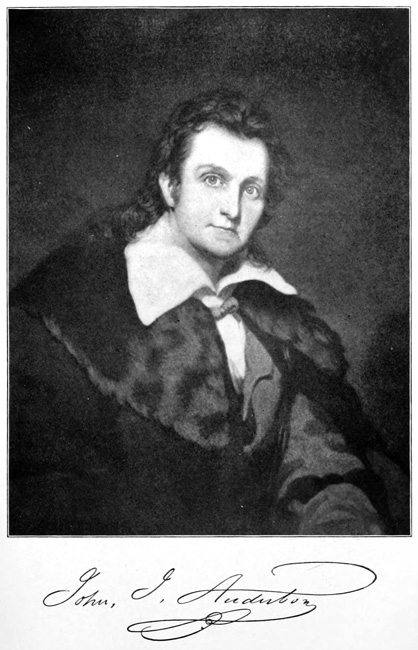

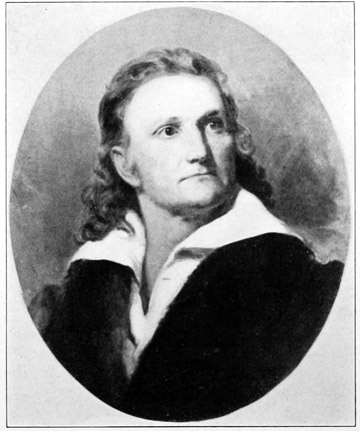

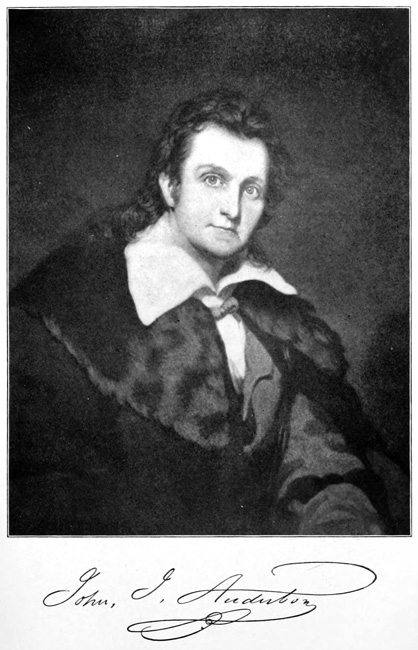

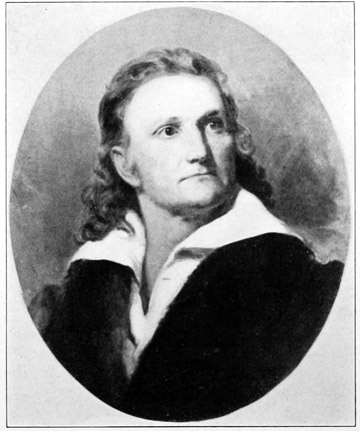

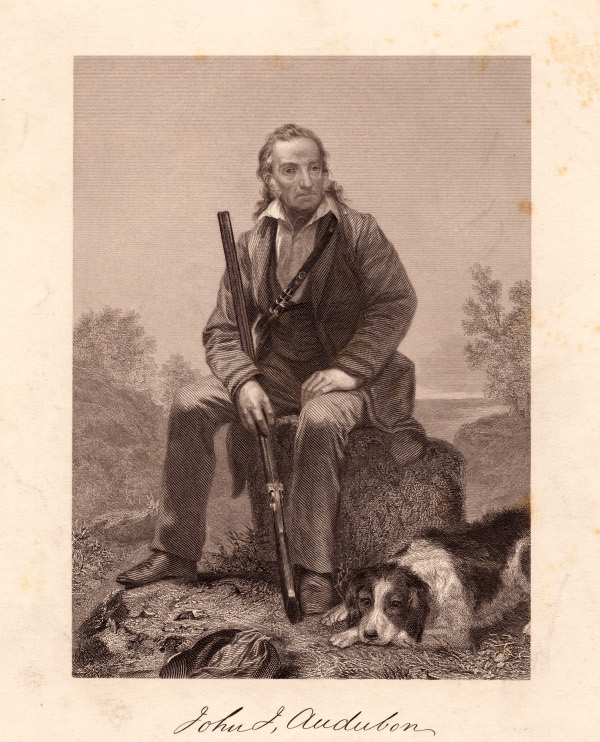

Audubon has given a sketch of his father in his own

words in "Myself," which appears in the pages following;

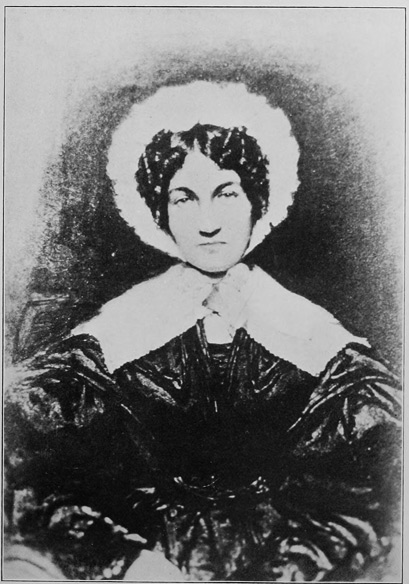

but of his mother little indeed is known. Only within the

year, have papers come into the hands of her great-grandchildren,

which prove her surname to have been Rabin.

Audubon himself tells of her tragic death, which was not,

however, in the St. Domingo insurrection of 1793, but in

one of the local uprisings of the slaves which were of

frequent occurrence in that beautiful island, whose history

is too dark to dwell upon. Beyond this nothing can be

found relating to the mother, whom Audubon lost before

he was old enough to remember her, except that in 1822

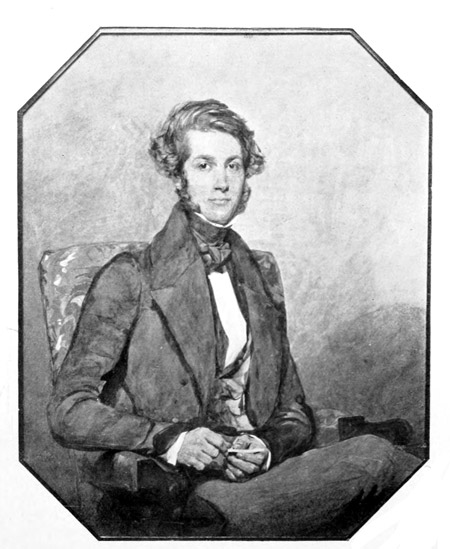

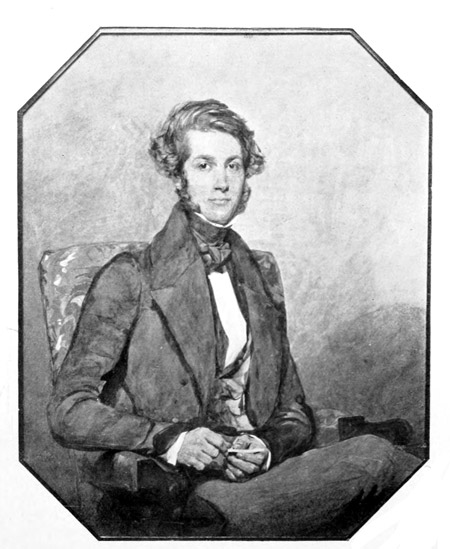

one of the family Marigny told my father, John Woodhouse

Audubon, then a boy of ten, who with his parents was living

in New Orleans, that she was "une dame d'une beauté

incomparable et avec beaucoup de fierté." It may seem

strange that nothing more can be found regarding this

lady, but it is to be remembered these were troublous

days, when stormy changes were the rule; and the roving

and adventurous sailor did not, I presume, encumber

himself with papers. To these circumstances also it is

probably due that the date of Audubon's birth is not

known, and must always remain an open question. In

his journals and letters various allusions are made to his

age, and many passages bearing on the matter are found,

but with one exception no two agree; he may have been

born anywhere between 1772 and 1783, and in the face of

this uncertainty the date usually given, May 5, 1780,

may be accepted, though the true one is no doubt

earlier.

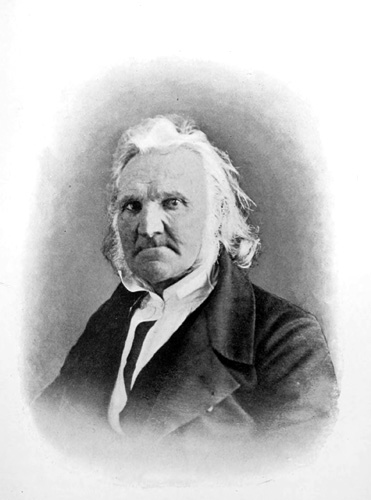

The attachment between Audubon and his father was of

the strongest description, as the long and affectionate, if

somewhat infrequent letters, still in the possession of the

family, fully demonstrate. When the Admiral was retired

from active service, he lived at La Gerbétière in France

with his second wife, Anne Moynette, until his death, on

February 19, 1818, at the great age of ninety-five.

In this home near the Loire, Audubon spent his happy

boyhood and youth, dearly beloved and loving, and receiving

the best education time and place afforded. As the

boy grew older and more advantages were desired for

him, came absences when he was at school in La Rochelle

and Paris; but La Gerbétière was his home till in early

manhood he returned to America, the land he loved above

all others, as his journals show repeatedly. The impress

of the years in France was never lost; he always had a

strong French accent, he possessed in a marked degree

the adaptability to circumstances which is a trait of that

nation, and his disposition inherited from both parents

was elated or depressed by a trifle. He was quick-tempered,

enthusiastic, and romantic, yet affectionate, forgiving,

and with unlimited industry and perseverance; he was

generous to every one with time, money, and possessions;

nothing was too good for others, but his own personal

requirements were of the simplest character. His life

shows all this and more, better than words of mine can

tell; and as the only account of his years till he left

Henderson, Ky., in 1819, is in his own journal, it is given

here in full.[2]

Myself.[3]

The precise period of my birth is yet an enigma to me, and I

can only say what I have often heard my father repeat to me on

this subject, which is as follows: It seems that my father had

large properties in Santo Domingo, and was in the habit of visiting

frequently that portion of our Southern States called, and

known by the name of, Louisiana, then owned by the French

Government.

During one of these excursions he married a lady of Spanish

extraction, whom I have been led to understand was as beautiful

as she was wealthy, and otherwise attractive, and who bore my

father three sons and a daughter, — I being the youngest of the

sons and the only one who survived extreme youth. My mother,

soon after my birth, accompanied my father to the estate of Aux

Cayes, on the island of Santo Domingo, and she was one of the

victims during the ever-to-be-lamented period of the negro

insurrection of that island.

My father, through the intervention of some faithful servants,

escaped from Aux Cayes with a good portion of his plate and

money, and with me and these humble friends reached New

Orleans in safety. From this place he took me to France, where,

having married the only mother I have ever known, he left me

under her charge and returned to the United States in the employ

of the French Government, acting as an officer under Admiral

Rochambeau. Shortly afterward, however, he landed in the

United States and became attached to the army under La Fayette.

The first of my recollective powers placed me in the central

portion of the city of Nantes, on the Loire River, in France,

where I still recollect particularly that I was much cherished by

my dear stepmother, who had no children of her own, and that I

was constantly attended by one or two black servants, who had

followed my father from Santo Domingo to New Orleans and

afterward to Nantes.

One incident which is as perfect in my memory as if it had

occurred this very day, I have thought of thousands of times

since, and will now put on paper as one of the curious things

which perhaps did lead me in after times to love birds, and to

finally study them with pleasure infinite. My mother had several

beautiful parrots and some monkeys; one of the latter was a full-grown

male of a very large species. One morning, while the servants

were engaged in arranging the room I was in, "Pretty

Polly" asking for her breakfast as usual, "Du pain au lait pour le

perroquet Mignonne,"[3b] the man of the woods probably thought the

bird presuming upon his rights in the scale of nature; be this as

it may, he certainly showed his supremacy in strength over the

denizen of the air, for, walking deliberately and uprightly toward

the poor bird, he at once killed it, with unnatural composure.

The sensations of my infant heart at this cruel sight were agony to

me. I prayed the servant to beat the monkey, but he, who for

some reason preferred the monkey to the parrot, refused. I

uttered long and piercing cries, my mother rushed into the

room, I was tranquillized, the monkey was forever afterward

chained, and Mignonne buried with all the pomp of a cherished

lost one.

This made, as I have said, a very deep impression on my

youthful mind. But now, my dear children, I must tell you somewhat

of my father, and of his parentage.

John Audubon, my grandfather, was born and lived at the

small village of Sable d'Olhonne, and was by trade a very humble

fisherman. He appears to have made up for the want of wealth

by the number of his children, twenty-one of whom he actually

raised to man and womanhood. All were sons, with one exception;

my aunt, one uncle, and my father, who was the twentieth

son, being the only members of that extraordinary numerous

family who lived to old age. In subsequent years, when I visited

Sable d'Olhonne, the old residents assured me that they had seen

the whole family, including both parents, at church many times.

When my father had reached the age of twelve years, his father

presented him with a shirt, a dress of coarse material, a stick, and

his blessing, and urged him to go and seek means for his future

support and sustenance.

Some kind whaler or cod-fisherman took him on board as a

"Boy." Of his life during his early voyages it would be useless

to trouble you; let it suffice for me to say that they were of the

usual most uncomfortable nature. How many trips he made I

cannot say, but he told me that by the time he was seventeen he

had become an able seaman before the mast; when twenty-one

he commanded a fishing-smack, and went to the great Newfoundland

Banks; at twenty-five he owned several small crafts, all

fishermen, and at twenty-eight sailed for Santo Domingo with his

little flotilla heavily loaded with the produce of the deep. "Fortune,"

said he to me one day, "now began to smile upon me. I

did well in this enterprise, and after a few more voyages of the

same sort gave up the sea, and purchased a small estate on the

Isle à Vaches;[4] the prosperity of Santo Domingo was at its zenith,

and in the course of ten years I had realized something very considerable.

The then Governor gave me an appointment which

called me to France, and having received some favors there, I

became once more a seafaring man, the government having

granted me the command of a small vessel of war."[5]

How long my father remained in the service, it is impossible

for me to say. The different changes occurring at the

time of the American Revolution, and afterward during that in

France, seem to have sent him from one place to another as if

a foot-ball; his property in Santo Domingo augmenting, however,

the while, and indeed till the liberation of the black slaves

there.

During a visit he paid to Pennsylvania when suffering from the

effects of a sunstroke, he purchased the beautiful farm of Mill

Grove, on the Schuylkill and Perkiomen streams. At this place,

and a few days only before the memorable battle (sic) of Valley

Forge, General Washington presented him with his portrait, now

in my possession; and highly do I value it as a memento of that

noble man and the glories of those days.[6] At the conclusion of

the war between England and her child of the West, my father

returned to France and continued in the employ of the naval department

of that country, being at one time sent to Plymouth,

England, in a seventy-five-gun ship to exchange prisoners. This

was, I think, in the short peace that took place between England

and France in 1801. He returned to Rochefort, where

he lived for several years, still in the employ of government.

He finally sent in his resignation and returned to Nantes and La

Gerbétière. He had many severe trials and afflictions before his

death, having lost my two older brothers early in the French

Revolution; both were officers in the army. His only sister was

killed by the Chouans of La Vendée,[7] and the only brother he

had was not on good terms with him. This brother resided at

Bayonne, and, I believe, had a large family, none of whom I have

ever seen or known.[8]

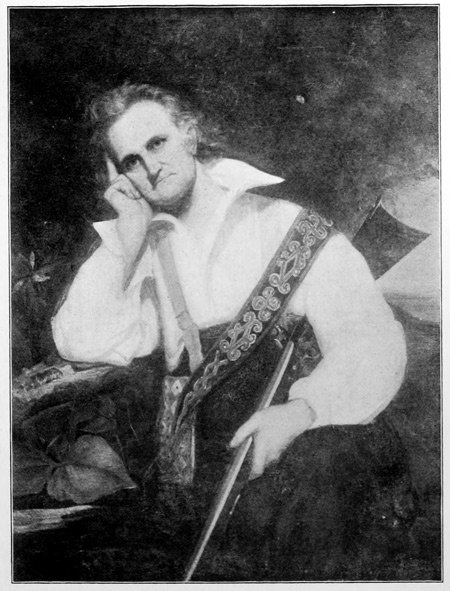

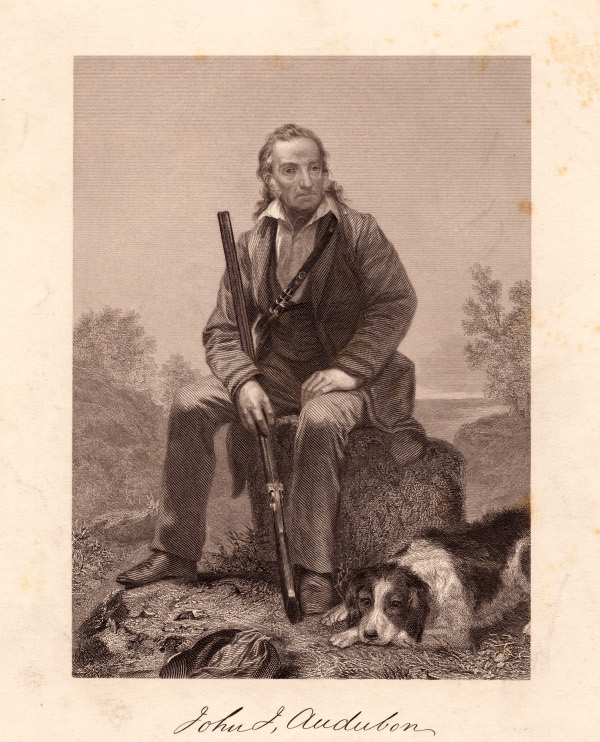

In personal appearance my father and I were of the same

height and stature, say about five feet ten inches, erect, and with

muscles of steel; his manners were those of a most polished

gentleman, for those and his natural understanding had been carefully

improved both by observation and by self-education. In temper

we much resembled each other also, being warm, irascible, and

at times violent; but it was like the blast of a hurricane, dreadful for

a time, when calm almost instantly returned. He greatly approved

of the change in France during the time of Napoleon, whom he

almost idolized. My father died in 1818, regretted most deservedly

on account of his simplicity, truth, and perfect sense of

honesty. Now I must return to myself.

My stepmother, who was devotedly attached to me, far too

much so for my good, was desirous that I should be brought up to

live and die "like a gentleman," thinking that fine clothes and

filled pockets were the only requisites needful to attain this end.

She therefore completely spoiled me, hid my faults, boasted to

every one of my youthful merits, and, worse than all, said frequently

in my presence that I was the handsomest boy in France.

All my wishes and idle notions were at once gratified; she went

so far as actually to grant me carte blanche[8b] at all the confectionery

shops in the town, and also of the village of Couéron, where

during the summer we lived, as it were, in the country.

My father was quite of another, and much more valuable

description of mind as regarded my future welfare; he believed

not in the power of gold coins as efficient means to render a man

happy. He spoke of the stores of the mind, and having suffered

much himself through the want of education, he ordered that I

should be put to school, and have teachers at home. "Revolutions,"

he was wont to say, "too often take place in the lives of

individuals, and they are apt to lose in one day the fortune they

before possessed; but talents and knowledge, added to sound

mental training, assisted by honest industry, can never fail, nor be

taken from any one once the possessor of such valuable means."

Therefore, notwithstanding all my mother's entreaties and her

tears, off to a school I was sent. Excepting only, perhaps, military

schools, none were good in France at this period; the thunders

of the Revolution still roared over the land, the Revolutionists

covered the earth with the blood of man, woman, and child. But

let me forever drop the curtain over the frightful aspect of this

dire picture. To think of these dreadful days is too terrible, and

would be too horrible and painful for me to relate to you, my

dear sons.

The school I went to was none of the best; my private teachers

were the only means through which I acquired the least benefit.

My father, who had been for so long a seaman, and who was then

in the French navy, wished me to follow in his steps, or else to

become an engineer. For this reason I studied drawing, geography,

mathematics, fencing, etc., as well as music, for which I

had considerable talent. I had a good fencing-master, and a

first-rate teacher of the violin; mathematics was hard, dull work,

I thought; geography pleased me more. For my other studies,

as well as for dancing, I was quite enthusiastic; and I well recollect

how anxious I was then to become the commander of a corps

of dragoons.

My father being mostly absent on duty, my mother suffered me

to do much as I pleased; it was therefore not to be wondered at

that, instead of applying closely to my studies, I preferred associating

with boys of my own age and disposition, who were more

fond of going in search of birds' nests, fishing, or shooting, than

of better studies. Thus almost every day, instead of going to

school when I ought to have gone, I usually made for the fields,

where I spent the day; my little basket went with me, filled with

good eatables, and when I returned home, during either winter or

summer, it was replenished with what I called curiosities, such as

birds' nests, birds' eggs, curious lichens, flowers of all sorts, and

even pebbles gathered along the shore of some rivulet.

The first time my father returned from sea after this my room

exhibited quite a show, and on entering it he was so pleased to

see my various collections that he complimented me on my taste

for such things: but when he inquired what else I had done, and

I, like a culprit, hung my head, he left me without saying another

word. Dinner over he asked my sister for some music, and, on

her playing for him, he was so pleased with her improvement that

he presented her with a beautiful book. I was next asked to play

on my violin, but alas! for nearly a month I had not touched it,

it was stringless; not a word was said on that subject. "Had I

any drawings to show?" Only a few, and those not good.

My good father looked at his wife, kissed my sister, and humming

a tune left the room. The next morning at dawn of day my

father and I were under way in a private carriage; my trunk, etc.,

were fastened to it, my violin-case was under my feet, the postilion

was ordered to proceed, my father took a book from his

pocket, and while he silently read I was left entirely to my own

thoughts.

After some days' travelling we entered the gates of Rochefort.

My father had scarcely spoken to me, yet there was no anger exhibited

in his countenance; nay, as we reached the house where

we alighted, and approached the door, near which a sentinel

stopped his walk and presented arms, I saw him smile as he raised

his hat and said a few words to the man, but so low that not a

syllable reached my ears.

The house was furnished with servants, and everything seemed

to go on as if the owner had not left it. My father bade me sit

by his side, and taking one of my hands calmly said to me: "My

beloved boy, thou art now safe. I have brought thee here that I

may be able to pay constant attention to thy studies; thou shalt

have ample time for pleasures, but the remainder must be employed

with industry and care. This day is entirely thine own,

and as I must attend to my duties, if thou wishest to see the docks,

the fine ships-of-war, and walk round the wall, thou may'st accompany

me." I accepted, and off together we went; I was presented

to every officer we met, and they noticing me more or

less, I saw much that day, yet still I perceived that I was like a

prisoner-of-war on parole in the city of Rochefort.

My best and most amiable companion was the son of Admiral,

or Vice-Admiral (I do not precisely recollect his rank) Vivien,

who lived nearly opposite to the house where my father and I

then resided; his company I much enjoyed, and with him all

my leisure hours were spent. About this time my father was sent

to England in a corvette with a view to exchange prisoners, and

he sailed on board the man-of-war "L'Institution" for Plymouth.

Previous to his sailing he placed me under the charge of his

secretary, Gabriel Loyen Dupuy Gaudeau, the son of a fallen

nobleman. Now this gentleman was of no pleasing nature to me;

he was, in fact, more than too strict and severe in all his prescriptions

to me, and well do I recollect that one morning, after

having been set to a very arduous task in mathematical problems,

I gave him the slip, jumped from the window, and ran off through

the gardens attached to the Marine Secrétariat. The unfledged

bird may stand for a while on the border of its nest, and perhaps

open its winglets and attempt to soar away, but his youthful imprudence

may, and indeed often does, prove inimical to his

prowess, as some more wary and older bird, that has kept an eye

toward him, pounces relentlessly upon the young adventurer and

secures him within the grasp of his more powerful talons. This

was the case with me in this instance. I had leaped from the

door of my cage and thought myself quite safe, while I rambled

thoughtlessly beneath the shadow of the trees in the garden and

grounds in which I found myself; but the secretary, with a side

glance, had watched my escape, and, ere many minutes had elapsed,

I saw coming toward me a corporal with whom, in fact, I was

well acquainted. On nearing me, and I did not attempt to escape,

our past familiarity was, I found, quite evaporated; he bid me,

in a severe voice, to follow him, and on my being presented to

my father's secretary I was at once ordered on board the pontoon

in port. All remonstrances proved fruitless, and on board the

pontoon I was conducted, and there left amid such a medley of

culprits as I cannot describe, and of whom, indeed, I have but

little recollection, save that I felt vile myself in their vile company.

My father returned in due course, and released me from

these floating and most disagreeable lodgings, but not without a

rather severe reprimand.

Shortly after this we returned to Nantes, and later to La

Gerbétière. My stay here was short, and I went to Nantes to

study mathematics anew, and there spent about one year, the

remembrance of which has flown from my memory, with the exception

of one incident, of which, when I happen to pass my

hand over the left side of my head, I am ever and anon reminded.

'Tis this: one morning, while playing with boys of my own age, a

quarrel arose among us, a battle ensued, in the course of which I

was knocked down by a round stone, that brought the blood from

that part of my skull, and for a time I lay on the ground unconscious,

but soon rallying, experienced no lasting effects but the

scar.

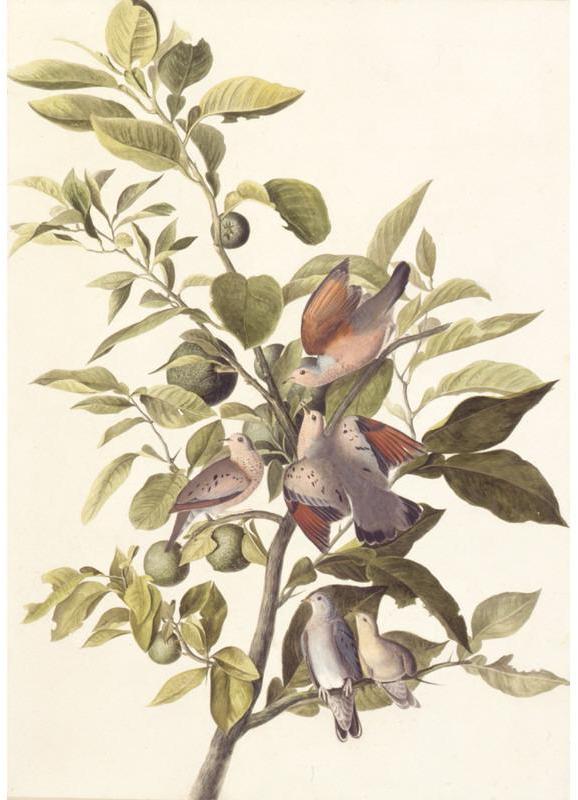

During all these years there existed within me a tendency to

follow Nature in her walks. Perhaps not an hour of leisure was

spent elsewhere than in woods and fields, and to examine either

the eggs, nest, young, or parents of any species of birds constituted

my delight. It was about this period that I commenced a

series of drawings of the birds of France, which I continued until

I had upward of two hundred drawings, all bad enough, my dear

sons, yet they were representations of birds, and I felt pleased

with them. Hundreds of anecdotes respecting my life at this

time might prove interesting to you, but as they are not in my

mind at this moment I will leave them, though you may find some

of them in the course of the following pages.

I was within a few months of being seventeen years old, when

my stepmother, who was an earnest Catholic, took into her head

that I should be confirmed; my father agreed. I was surprised

and indifferent, but yet as I loved her as if she had been my own

mother, — and well did she merit my deepest affection, — I took to

the catechism, studied it and other matters pertaining to the ceremony,

and all was performed to her liking. Not long after this,

my father, anxious as he was that I should be enrolled in

Napoleon's army as a Frenchman, found it necessary to send me

back to my own beloved country, the United States of America,

and I came with intense and indescribable pleasure.

On landing at New York I caught the yellow fever by walking

to the bank at Greenwich to get the money to which my father's

letter of credit entitled me. The kind man who commanded the

ship that brought me from France, whose name was a common

one, John Smith, took particular charge of me, removed me to

Morristown, N.J., and placed me under the care of two Quaker

ladies who kept a boarding-house. To their skilful and untiring

ministrations I may safely say I owe the prolongation of my life.

Letters were forwarded by them to my father's agent, Miers Fisher

of Philadelphia, of whom I have more to say hereafter. He came

for me in his carriage and removed me to his villa, at a short distance

from Philadelphia and on the road toward Trenton. There

I would have found myself quite comfortable had not incidents

taken place which are so connected with the change in my life as

to call immediate attention to them.

Miers Fisher had been my father's trusted agent for about

eighteen years, and the old gentlemen entertained great mutual

friendship; indeed it would seem that Mr. Fisher was actually

desirous that I should become a member of his family, and this

was evinced within a few days by the manner in which the good

Quaker presented me to a daughter of no mean appearance, but

toward whom I happened to take an unconquerable dislike. Then

he was opposed to music of all descriptions, as well as to dancing,

could not bear me to carry a gun, or fishing-rod, and, indeed,

condemned most of my amusements. All these things were difficulties

toward accomplishing a plan which, for aught I know to

the contrary, had been premeditated between him and my father,

and rankled the heart of the kindly, if somewhat strict Quaker.

They troubled me much also; at times I wished myself anywhere

but under the roof of Mr. Fisher, and at last I reminded him

that it was his duty to install me on the estate to which my father

had sent me.

One morning, therefore, I was told that the carriage was ready

to carry me there, and toward my future home he and I went.

You are too well acquainted with the position of Mill Grove for

me to allude to that now; suffice it to say that we reached the

former abode of my father about sunset. I was presented to

our tenant, William Thomas, who also was a Quaker, and took

possession under certain restrictions, which amounted to my

not receiving more than enough money per quarter than was

considered sufficient for the expenditure of a young gentleman.

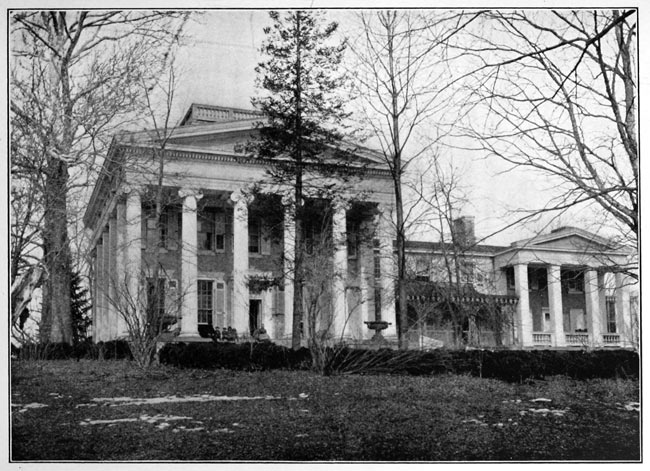

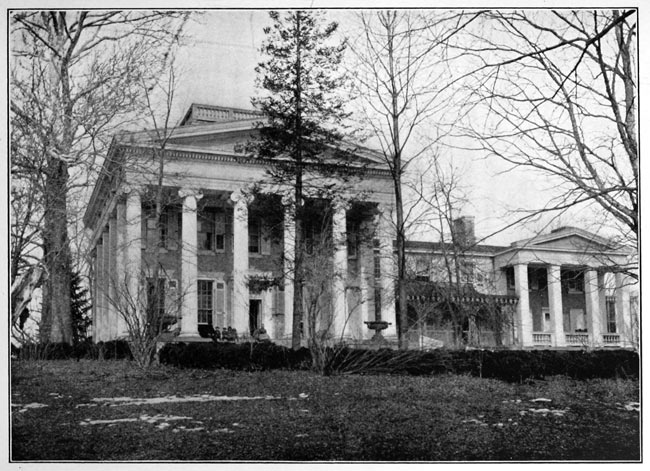

|

|

MILL GROVE MANSION ON THE PERKIOMEN CREEK.

FROM A PHOTOGRAPH FROM W. H. WETHERILL, ESQ.

|

Miers Fisher left me the next morning, and after him went

my blessings, for I thought his departure a true deliverance; yet

this was only because our tastes and educations were so different,

for he certainly was a good and learned man. Mill Grove was

ever to me a blessed spot; in my daily walks I thought I perceived

the traces left by my father as I looked on the even fences

round the fields, or on the regular manner with which avenues of

trees, as well as the orchards, had been planted by his hand.

The mill was also a source of joy to me, and in the cave, which

you too remember, where the Pewees were wont to build, I never

failed to find quietude and delight.

Hunting, fishing, drawing, and music occupied my every

moment; cares I knew not, and cared naught about them. I

purchased excellent and beautiful horses, visited all such neighbors

as I found congenial spirits, and was as happy as happy

could be. A few months after my arrival at Mill Grove, I was

informed one day that an English family had purchased the

plantation next to mine, that the name of the owner was Bakewell,

and moreover that he had several very handsome and interesting

daughters, and beautiful pointer dogs. I listened, but

cared not a jot about them at the time. The place was within

sight of Mill Grove, and Fatland Ford, as it was called,

was merely divided from my estate by a road leading to the

Schuylkill River. Mr. William Bakewell, the father of the family,

had called on me one day, but, finding I was rambling in

the woods in search of birds, left a card and an invitation to

go shooting with him. Now this gentleman was an Englishman,

and I such a foolish boy that, entertaining the greatest prejudices

against all of his nationality, I did not return his visit for many

weeks, which was as absurd as it was ungentlemanly and impolite.

Mrs. Thomas, good soul, more than once spoke to me on the

subject, as well as her worthy husband, but all to no import;

English was English with me, my poor childish mind was settled

on that, and as I wished to know none of the race the call remained

unacknowledged.

Frosty weather, however, came, and anon was the ground

covered with the deep snow. Grouse were abundant along the

fir-covered ground near the creek, and as I was in pursuit of

game one frosty morning I chanced to meet Mr. Bakewell in the

woods. I was struck with the kind politeness of his manner, and

found him an expert marksman. Entering into conversation, I

admired the beauty of his well-trained dogs, and, apologizing for

my discourtesy, finally promised to call upon him and his

family.

Well do I recollect the morning, and may it please God that I

may never forget it, when for the first time I entered Mr. Bakewell's

dwelling. It happened that he was absent from home,

and I was shown into a parlor where only one young lady was

snugly seated at her work by the fire. She rose on my entrance,

offered me a seat, and assured me of the gratification her father

would feel on his return, which, she added, would be in a few

moments, as she would despatch a servant for him. Other

ruddy cheeks and bright eyes made their transient appearance,

but, like spirits gay, soon vanished from my sight; and there I sat,

my gaze riveted, as it were, on the young girl before me, who,

half working, half talking, essayed to make the time pleasant to

me. Oh! may God bless her! It was she, my dear sons, who

afterward became my beloved wife, and your mother. Mr. Bakewell

soon made his appearance, and received me with the

manner and hospitality of a true English gentleman. The other

members of the family were soon introduced to me, and "Lucy"

was told to have luncheon produced. She now arose from her

seat a second time, and her form, to which I had previously paid

but partial attention, showed both grace and beauty; and my

heart followed every one of her steps. The repast over, guns

and dogs were made ready.

Lucy, I was pleased to believe, looked upon me with some

favor, and I turned more especially to her on leaving. I felt

that certain "je ne sais quoi"[8c] which intimated that, at least, she

was not indifferent to me.

To speak of the many shooting parties that took place with

Mr. Bakewell would be quite useless, and I shall merely say that

he was a most excellent man, a great shot, and possessed of extraordinary

learning — aye, far beyond my comprehension. A

few days after this first interview with the family the Perkiomen

chanced to be bound with ice, and many a one from the neighborhood

was playing pranks on the glassy surface of that lovely stream.

Being somewhat of a skater myself, I sent a note to the inhabitants

of Fatland Ford, inviting them to come and partake of the

simple hospitality of Mill Grove farm, and the invitation was

kindly received and accepted. My own landlady bestirred herself

to the utmost in the procuring of as many pheasants and

partridges as her group of sons could entrap, and now under my

own roof was seen the whole of the Bakewell family, seated round

the table which has never ceased to be one of simplicity and

hospitality.

After dinner we all repaired to the ice on the creek, and there

in comfortable sledges, each fair one was propelled by an ardent

skater. Tales of love may be extremely stupid to the majority,

so that I will not expatiate on these days, but to me, my dear

sons, and under such circumstances as then, and, thank God, now

exist, every moment was to me one of delight.

But let me interrupt my tale to tell you somewhat of other

companions whom I have heretofore neglected to mention.

These are two Frenchmen, by name Da Costa and Colmesnil.

A lead mine had been discovered by my tenant, William Thomas,

to which, besides the raising of fowls, I paid considerable attention;

but I knew nothing of mineralogy or mining, and my

father, to whom I communicated the discovery of the mine, sent

Mr. Da Costa as a partner and partial guardian from France.

This fellow was intended to teach me mineralogy and mining

engineering, but, in fact, knew nothing of either; besides which

he was a covetous wretch, who did all he could to ruin my father,

and indeed swindled both of us to a large amount. I had to go

to France and expose him to my father to get rid of him, which

I fortunately accomplished at first sight of my kind parent. A

greater scoundrel than Da Costa never probably existed, but

peace be with his soul.

The other, Colmesnil, was a very interesting young Frenchman

with whom I became acquainted. He was very poor, and I

invited him to come and reside under my roof. This he did,

remaining for many months, much to my delight. His appearance

was typical of what he was, a perfect gentleman; he was

handsome in form, and possessed of talents far above my own.

When introduced to your mother's family he was much thought

of, and at one time he thought himself welcome to my Lucy;

but it was only a dream, and when once undeceived by her whom

I too loved, he told me he must part with me. This we did with

mutual regret, and he returned to France, where, though I have

lost sight of him, I believe he is still living.

During the winter connected with this event your uncle

Thomas Bakewell, now residing in Cincinnati, was one morning

skating with me on the Perkiomen, when he challenged me to

shoot at his hat as he tossed it in the air, which challenge I accepted

with great pleasure. I was to pass by at full speed, within

about twenty-five feet of where he stood, and to shoot only when

he gave the word. Off I went like lightning, up and down, as if

anxious to boast of my own prowess while on the glittering surface

beneath my feet; coming, however, within the agreed

distance the signal was given, the trigger pulled, off went the

load, and down on the ice came the hat of my future brother-in-law,

as completely perforated as if a sieve. He repented, alas! too

late, and was afterward severely reprimanded by Mr. Bakewell.

Another anecdote I must relate to you on paper, which I have

probably too often repeated in words, concerning my skating in

those early days of happiness; but, as the world knows nothing

of it, I shall give it to you at some length. It was arranged one

morning between your young uncle, myself, and several other

friends of the same age, that we should proceed on a duck-shooting

excursion up the creek, and, accordingly, off we went

after an early breakfast. The ice was in capital order wherever

no air-holes existed, but of these a great number interrupted our

course, all of which were, however, avoided as we proceeded upward

along the glittering, frozen bosom of the stream. The day

was spent in much pleasure, and the game collected was not

inconsiderable.

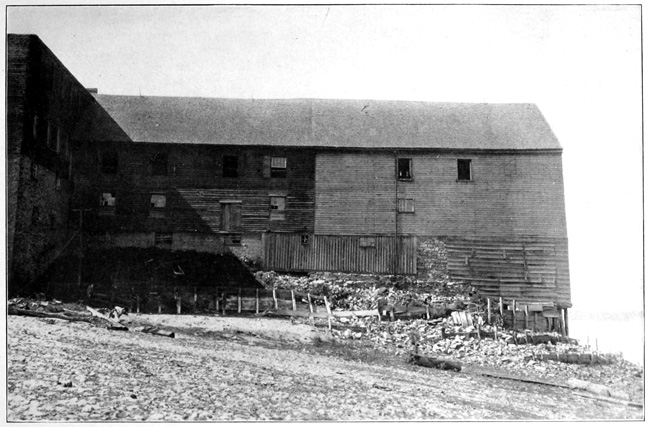

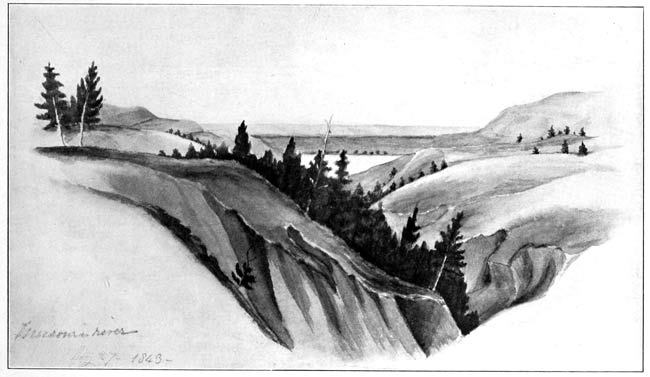

|

|

FATLAND FORD MANSION,

LOOKING TOWARD VALLEY FORGE.

FROM A PHOTOGRAPH FROM W. H. WETHERILL, ESQ.

|

On our return, in the early dusk of the evening, I was bid to

lead the way; I fastened a white handkerchief to a stick, held it

up, and we all proceeded toward home as a flock of wild ducks

to their roosting-grounds. Many a mile had already been passed,

and, as gayly as ever, we were skating swiftly along when darkness

came on, and now our speed was increased. Unconsciously

I happened to draw so very near a large air-hole that

to check my headway became quite impossible, and down it I

went, and soon felt the power of a most chilling bath. My senses

must, for aught I know, have left me for a while; be this as it

may, I must have glided with the stream some thirty or forty

yards, when, as God would have it, up I popped at another air-hole,

and here I did, in some way or another, manage to crawl

out. My companions, who in the gloom had seen my form so

suddenly disappear, escaped the danger, and were around me

when I emerged from the greatest peril I have ever encountered,

not excepting my escape from being murdered on the prairie, or

by the hands of that wretch S — — B — — , of Henderson. I was

helped to a shirt from one, a pair of dry breeches from another,

and completely dressed anew in a few minutes, if in motley and

ill-fitting garments; our line of march was continued, with, however,

much more circumspection. Let the reader, whoever he

may be, think as he may like on this singular and, in truth, most

extraordinary escape from death; it is the truth, and as such I

have written it down as a wonderful act of Providence.

Mr. Da Costa, my tutor, took it into his head that my affection

for your mother was rash and inconsiderate. He spoke triflingly

of her and of her parents, and one day said to me that for a man

of my rank and expectations to marry Lucy Bakewell was out of

the question. If I laughed at him or not I cannot tell you, but

of this I am certain, that my answers to his talks on this subject

so exasperated him that he immediately afterward curtailed my

usual income, made some arrangements to send me to India, and

wrote to my father accordingly. Understanding from many of

my friends that his plans were fixed, and finally hearing from

Philadelphia, whither Da Costa had gone, that he had taken my

passage from Philadelphia to Canton, I walked to Philadelphia,

entered his room quite unexpectedly, and asked him for such an

amount of money as would enable me at once to sail for France

and there see my father.

The cunning wretch, for I cannot call him by any other name,

smiled, and said: "Certainly, my dear sir," and afterward gave

me a letter of credit on a Mr. Kauman, a half-agent, half-banker,

then residing at New York. I returned to Mill Grove, made all

preparatory plans for my departure, bid a sad adieu to my Lucy

and her family, and walked to New York. But never mind the

journey; it was winter, the country lay under a covering of snow,

but withal I reached New York on the third day, late in the

evening.

Once there, I made for the house of a Mrs. Palmer, a lady of

excellent qualities, who received me with the utmost kindness,

and later on the same evening I went to the house of your

grand-uncle, Benjamin Bakewell, then a rich merchant of New

York, managing the concerns of the house of Guelt, bankers, of

London. I was the bearer of a letter from Mr. Bakewell, of Fatland

Ford, to this brother of his, and there I was again most

kindly received and housed.

The next day I called on Mr. Kauman; he read Da Costa's

letter, smiled, and after a while told me he had nothing to give

me, and in plain terms said that instead of a letter of credit, Da

Costa — that rascal! — had written and advised him to have me

arrested and shipped to Canton. The blood rose to my temples,

and well it was that I had no weapon about me, for I feel even

now quite assured that his heart must have received the result of

my wrath. I left him half bewildered, half mad, and went to

Mrs. Palmer, and spoke to her of my purpose of returning at once

to Philadelphia and there certainly murdering Da Costa. Women

have great power over me at any time, and perhaps under all circumstances.

Mrs. Palmer quieted me, spoke religiously of the

cruel sin I thought of committing, and, at last, persuaded me to

relinquish the direful plan. I returned to Mr. Bakewell's low-spirited

and mournful, but said not a word about all that had

passed. The next morning my sad visage showed something was

wrong, and I at last gave vent to my outraged feelings.

Benjamin Bakewell was a friend of his brother (may you ever

be so toward each other). He comforted me much, went with

me to the docks to seek a vessel bound to France, and offered

me any sum of money I might require to convey me to my father's

house. My passage was taken on board the brig "Hope,"

of New Bedford, and I sailed in her, leaving Da Costa and

Kauman in a most exasperated state of mind. The fact is, these

rascals intended to cheat both me and my father. The brig

was bound direct for Nantes. We left the Hook under a very

fair breeze, and proceeded at a good rate till we reached the

latitude of New Bedford, in Massachusetts, when my captain

came to me as if in despair, and said he must run into port, as

the vessel was so leaky as to force him to have her unloaded and

repaired before he proceeded across the Atlantic. Now this was

only a trick; my captain was newly married, and was merely

anxious to land at New Bedford to spend a few days with his

bride, and had actually caused several holes to be bored below

water-mark, which leaked enough to keep the men at the pumps.

We came to anchor close to the town of New Bedford; the captain

went on shore, entered a protest, the vessel was unloaded,

the apertures bunged up, and after a week, which I spent in

being rowed about the beautiful harbor, we sailed for La Belle

France. A few days after having lost sight of land we were

overtaken by a violent gale, coming fairly on our quarter, and

before it we scudded at an extraordinary rate, and during the

dark night had the misfortune to lose a fine young sailor overboard.

At one part of the sea we passed through an immensity

of dead fish floating on the surface of the water, and, after nineteen

days from New Bedford, we had entered the Loire, and

anchored off Painbœuf, the lower harbor of Nantes.

On sending my name to the principal officer of the customs,

he came on board, and afterward sent me to my father's villa,

La Gerbétière, in his barge, and with his own men, and late that

evening I was in the arms of my beloved parents. Although I

had written to them previous to leaving America, the rapidity of

my voyage had prevented them hearing of my intentions, and to

them my appearance was sudden and unexpected. Most welcome,

however, I was; I found my father hale and hearty, and

chère maman as fair and good as ever. Adored maman, peace

be with thee!

I cannot trouble you with minute accounts of my life in France

for the following two years, but will merely tell you that my first

object being that of having Da Costa disposed of, this was

first effected; the next was my father's consent to my marriage,

and this was acceded to as soon as my good father had received

answers to letters written to your grandfather, William Bakewell.

In the very lap of comfort my time was happily spent; I went

out shooting and hunting, drew every bird I procured, as well as

many other objects of natural history and zoölogy, though these

were not the subjects I had studied under the instruction of the

celebrated David.

It was during this visit that my sister Rosa was married to

Gabriel Dupuy Gaudeau, and I now also became acquainted with

Ferdinand Rozier, whom you well know. Between Rozier and

myself my father formed a partnership to stand good for nine

years in America.

France was at that time in a great state of convulsion; the republic

had, as it were, dwindled into a half monarchical, half

democratic era. Bonaparte was at the height of success, overflowing

the country as the mountain torrent overflows the plains

in its course. Levies, or conscriptions, were the order of the

day, and my name being French my father felt uneasy lest I

should be forced to take part in the political strife of those

days.

I underwent a mockery of an examination, and was received as

midshipman in the navy, went to Rochefort, was placed on

board a man-of-war, and ran a short cruise. On my return, my

father had, in some way, obtained passports for Rozier and me,

and we sailed for New York. Never can I forget the day when,

at St. Nazaire, an officer came on board to examine the papers of

the many passengers. On looking at mine he said: "My dear

Mr. Audubon, I wish you joy; would to God that I had such

papers; how thankful I should be to leave unhappy France under

the same passport."

About a fortnight after leaving France a vessel gave us chase.

We were running before the wind under all sail, but the unknown

gained on us at a great rate, and after a while stood to the windward

of our ship, about half a mile off. She fired a gun, the ball

passed within a few yards of our bows; our captain heeded not,

but kept on his course, with the United States flag displayed and

floating in the breeze. Another and another shot was fired at us;

the enemy closed upon us; all the passengers expected to receive

her broadside. Our commander hove to: a boat was almost

instantaneously lowered and alongside our vessel;[9] two officers

leaped on board, with about a dozen mariners; the first asked

for the captain's papers, while the latter with his men kept guard

over the whole.

The vessel which had pursued us was the "Rattlesnake" and

was what I believe is generally called a privateer, which means

nothing but a pirate; every one of the papers proved to be in perfect

accordance with the laws existing between England and America,

therefore we were not touched nor molested, but the English

officers who had come on board robbed the ship of almost everything

that was nice in the way of provisions, took our pigs and

sheep, coffee and wines, and carried off our two best sailors

despite all the remonstrances made by one of our members of

Congress, I think from Virginia, who was accompanied by a

charming young daughter. The "Rattlesnake" kept us under her

lee, and almost within pistol-shot, for a whole day and night,

ransacking the ship for money, of which we had a good deal in

the run beneath a ballast of stone. Although this was partially

removed they did not find the treasure. I may here tell you

that I placed the gold belonging to Rozier and myself, wrapped

in some clothing, under a cable in the bow of the ship, and there

it remained snug till the "Rattlesnake" had given us leave to

depart, which you may be sure we did without thanks to her

commander or crew; we were afterward told the former had

his wife with him.

After this rencontre we sailed on till we came to within about

thirty miles of the entrance to the bay of New York,[10] when we

passed a fishing-boat, from which we were hailed and told that two

British frigates lay off the entrance of the Hook, had fired an American

ship, shot a man, and impressed so many of our seamen that

to attempt reaching New York might prove to be both unsafe and

unsuccessful. Our captain, on hearing this, put about immediately,

and sailed for the east end of Long Island Sound, which we

entered uninterrupted by any other enemy than a dreadful gale,

which drove us on a sand-bar in the Sound, but from which we

made off unhurt during the height of the tide and finally reached

New York.

I at once called on your uncle Benjamin Bakewell, stayed with

him a day, and proceeded at as swift a rate as possible to Fatland

Ford, accompanied by Ferdinand Rozier. Mr. Da Costa

was at once dismissed from his charge. I saw my dear Lucy,

and was again my own master.

Perhaps it would be well for me to give you some slight information

respecting my mode of life in those days of my youth,

and I shall do so without gloves. I was what in plain terms

may be called extremely extravagant. I had no vices, it is true,

neither had I any high aims. I was ever fond of shooting, fishing,

and riding on horseback; the raising of fowls of every sort

was one of my hobbies, and to reach the maximum of my desires

in those different things filled every one of my thoughts. I was

ridiculously fond of dress. To have seen me going shooting in

black satin smallclothes, or breeches, with silk stockings, and

the finest ruffled shirt Philadelphia could afford, was, as I now

realize, an absurd spectacle, but it was one of my many foibles, and

I shall not conceal it. I purchased the best horses in the country,

and rode well, and felt proud of it; my guns and fishing-tackle

were equally good, always expensive and richly ornamented,

often with silver. Indeed, though in America, I cut as many

foolish pranks as a young dandy in Bond Street or Piccadilly.

I was extremely fond of music, dancing, and drawing; in all I

had been well instructed, and not an opportunity was lost to confirm

my propensities in those accomplishments. I was, like most

young men, filled with the love of amusement, and not a ball, a

skating-match, a house or riding party took place without me.

Withal, and fortunately for me, I was not addicted to gambling;

cards I disliked, and I had no other evil practices. I was, besides,

temperate to an intemperate degree. I lived, until the day of

my union with your mother, on milk, fruits, and vegetables, with

the addition of game and fish at times, but never had I swallowed

a single glass of wine or spirits until the day of my wedding. The

result has been my uncommon, indeed iron, constitution. This

was my constant mode of life ever since my earliest recollection,

and while in France it was extremely annoying to all those round

me. Indeed, so much did it influence me that I never went to

dinners, merely because when so situated my peculiarities in my

choice of food occasioned comment, and also because often not a

single dish was to my taste or fancy, and I could eat nothing from

the sumptuous tables before me. Pies, puddings, eggs, milk, or

cream was all I cared for in the way of food, and many a time

have I robbed my tenant's wife, Mrs. Thomas, of the cream intended

to make butter for the Philadelphia market. All this

time I was as fair and as rosy as a girl, though as strong, indeed

stronger than most young men, and as active as a buck. And

why, have I thought a thousand times, should I not have kept to

that delicious mode of living? and why should not mankind in

general be more abstemious than mankind is?

Before I sailed for France I had begun a series of drawings of

the birds of America, and had also begun a study of their habits.

I at first drew my subjects dead, by which I mean to say that,

after procuring a specimen, I hung it up either by the head, wing,

or foot, and copied it as closely as I possibly could.

In my drawing of birds only did I interest Mr. Da Costa. He

always commended my efforts, nay he even went farther, for one

morning, while I was drawing a figure of the Ardea herodias,[11] he

assured me the time might come when I should be a great American

naturalist. However curious it may seem to the scientific

world that these sayings from the lips of such a man should affect

me, I assure you they had great weight with me, and I felt a

certain degree of pride in these words even then.

Too young and too useless to be married, your grandfather

William Bakewell advised me to study the mercantile business;

my father approved, and to insure this training under the best

auspices I went to New York, where I entered as a clerk for your

great-uncle Benjamin Bakewell, while Rozier went to a French

house at Philadelphia.

The mercantile business did not suit me. The very first venture

which I undertook was in indigo; it cost me several hundred

pounds, the whole of which was lost. Rozier was no more fortunate

than I, for he shipped a cargo of hams to the West Indies,

and not more than one-fifth of the cost was returned. Yet I

suppose we both obtained a smattering of business.

Time passed, and at last, on April 8th, 1808, your mother and

I were married by the Rev. Dr. Latimer, of Philadelphia, and the

next morning left Fatland Ford and Mill Grove for Louisville, Ky.

For some two years previous to this, Rozier and I had visited the

country from time to time as merchants, had thought well of it,

and liked it exceedingly. Its fertility and abundance, the hospitality

and kindness of the people were sufficiently winning things

to entice any one to go there with a view to comfort and happiness.

We had marked Louisville as a spot designed by nature to become

a place of great importance, and, had we been as wise as we

now are, I might never have published the "Birds of America;"

for a few hundred dollars laid out at that period, in lands or town

lots near Louisville, would, if left to grow over with grass to a

date ten years past (this being 1835), have become an immense

fortune. But young heads are on young shoulders; it was not to

be, and who cares?

On our way to Pittsburg, we met with a sad accident, that

nearly cost the life of your mother. The coach upset on the

mountains, and she was severely, but fortunately not fatally hurt.

We floated down the Ohio in a flatboat, in company with several

other young families; we had many goods, and opened a large

store at Louisville, which went on prosperously when I attended to

it; but birds were birds then as now, and my thoughts were ever

and anon turning toward them as the objects of my greatest delight.

I shot, I drew, I looked on nature only; my days were happy

beyond human conception, and beyond this I really cared not.

Victor was born June 12, 1809, at Gwathway's Hotel of the

Indian Queen. We had by this time formed the acquaintance of

many persons in and about Louisville; the country was settled

by planters and farmers of the most benevolent and hospitable

nature; and my young wife, who possessed talents far above par,

was regarded as a gem, and received by them all with the greatest

pleasure. All the sportsmen and hunters were fond of me,

and I became their companion; my fondness for fine horses was

well kept up, and I had as good as the country — and the country

was Kentucky — could afford. Our most intimate friends

were the Tarascons and the Berthouds, at Louisville and Shippingport.

The simplicity and whole-heartedness of those days I

cannot describe; man was man, and each, one to another, a

brother.

I seldom passed a day without drawing a bird, or noting

something respecting its habits, Rozier meantime attending the

counter. I could relate many curious anecdotes about him, but

never mind them; he made out to grow rich, and what more

could he wish for?

In 1810 Alexander Wilson the naturalist — not the American

naturalist — called upon me.[12] About 1812 your uncle Thomas

W. Bakewell sailed from New York or Philadelphia, as a partner

of mine, and took with him all the disposable money which I had

at that time, and there [New Orleans] opened a mercantile

house under the name of "Audubon & Bakewell."

Merchants crowded to Louisville from all our Eastern cities.

None of them were, as I was, intent on the study of birds, but all

were deeply impressed with the value of dollars. Louisville did

not give us up, but we gave up Louisville. I could not bear to

give the attention required by my business, and which, indeed,

every business calls for, and, therefore, my business abandoned

me. Indeed, I never thought of it beyond the ever-engaging

journeys which I was in the habit of taking to Philadelphia or

New York to purchase goods; these journeys I greatly enjoyed,

as they afforded me ample means to study birds and their habits

as I travelled through the beautiful, the darling forests of Ohio,

Kentucky, and Pennsylvania.

Were I here to tell you that once, when travelling, and driving

several horses before me laden with goods and dollars, I lost

sight of the pack-saddles, and the cash they bore, to watch the

motions of a warbler, I should only repeat occurrences that happened

a hundred times and more in those days. To an ordinary

reader this may appear very odd, but it is as true, my dear sons, as

it is that I am now scratching this poor book of mine with a

miserable iron pen. Rozier and myself still had some business

together, but we became discouraged at Louisville, and I longed

to have a wilder range; this made us remove to Henderson, one

hundred and twenty-five miles farther down the fair Ohio. We

took there the remainder of our stock on hand, but found the

country so very new, and so thinly populated that the commonest

goods only were called for. I may say our guns and fishing-lines

were the principal means of our support, as regards food.

John Pope, our clerk, who was a Kentuckian, was a good shot

and an excellent fisherman, and he and I attended to the procuring

of game and fish, while Rozier again stood behind the

counter.

Your beloved mother and I were as happy as possible, the

people round loved us, and we them in return; our profits were

enormous, but our sales small, and my partner, who spoke English

but badly, suggested that we remove to St. Geneviève, on

the Mississippi River. I acceded to his request to go there, but

determined to leave your mother and Victor at Henderson, not

being quite sure that our adventure would succeed as we hoped.

I therefore placed her and the children under the care of Dr.

Rankin and his wife, who had a fine farm about three miles from

Henderson, and having arranged our goods on board a large

flatboat, my partner and I left Henderson in the month of December,

1810, in a heavy snow-storm. This change in my plans

prevented me from going, as I had intended, on a long expedition.

In Louisville we had formed the acquaintance of Major

Croghan (an old friend of my father's), and of General Jonathan

Clark, the brother of General William Clark, the first white man

who ever crossed the Rocky Mountains. I had engaged to go

with him, but was, as I have said, unfortunately prevented. To

return to our journey. When we reached Cash Creek we were

bound by ice for a few weeks; we then attempted to ascend the

Mississippi, but were again stopped in the great bend called

Tawapatee Bottom, where we again planted our camp till a thaw

broke the ice.[13] In less than six weeks, however, we reached the

village of St. Geneviève. I found at once it was not the place

for me; its population was then composed of low French Canadians,

uneducated and uncouth, and the ever-longing wish to be

with my beloved wife and children drew my thoughts to Henderson,

to which I decided to return almost immediately. Scarcely

any communication existed between the two places, and I felt cut

off from all dearest to me. Rozier, on the contrary, liked it; he

found plenty of French with whom to converse. I proposed

selling out to him, a bargain was made, he paid me a certain

amount in cash, and gave me bills for the residue. This accomplished,

I purchased a beauty of a horse, for which I paid dear

enough, and bid Rozier farewell. On my return trip to Henderson

I was obliged to stop at a humble cabin, where I so nearly

ran the chance of losing my life, at the hands of a woman and

her two desperate sons, that I have thought fit since to introduce

this passage in a sketch called "The Prairie," which is to be

found in the first volume of my "Ornithological Biography."

Winter was just bursting into spring when I left the land of lead

mines. Nature leaped with joy, as it were, at her own new-born

marvels, the prairies began to be dotted with beauteous flowers,

abounded with deer, and my own heart was filled with happiness

at the sights before me. I must not forget to tell you that I

crossed those prairies on foot at another time, for the purpose of

collecting the money due to me from Rozier, and that I walked

one hundred and sixty-five miles in a little over three days, much

of the time nearly ankle deep in mud and water, from which I suffered

much afterward by swollen feet. I reached Henderson in

early March, and a few weeks later the lower portions of Kentucky

and the shores of the Mississippi suffered severely by earthquakes.

I felt their effects between Louisville and Henderson, and also at

Dr. Rankin's. I have omitted to say that my second son, John

Woodhouse, was born under Dr. Rankin's roof on November 30,

1812; he was an extremely delicate boy till about a twelvemonth

old, when he suddenly acquired strength and grew to be a lusty

child.

Your uncle, Thomas W. Bakewell, had been all this time in New

Orleans, and thither I had sent him almost all the money I could

raise; but notwithstanding this, the firm could not stand, and one

day, while I was making a drawing of an otter, he suddenly appeared.

He remained at Dr. Rankin's a few days, talked much

to me about our misfortunes in trade, and left us for Fatland

Ford.

My pecuniary means were now much reduced. I continued

to draw birds and quadrupeds, it is true, but only now and then

thought of making any money. I bought a wild horse, and on

its back travelled over Tennessee and a portion of Georgia, and

so round till I finally reached Philadelphia, and then to your

grandfather's at Fatland Ford. He had sold my plantation of

Mill Grove to Samuel Wetherell, of Philadelphia, for a good

round sum, and with this I returned through Kentucky and at

last reached Henderson once more. Your mother was well, both

of you were lovely darlings of our hearts, and the effects of poverty

troubled us not. Your uncle T. W. Bakewell was again in

New Orleans and doing rather better, but this was a mere transient

clearing of that sky which had been obscured for many a

long day.

Determined to do something for myself, I took to horse, rode

to Louisville with a few hundred dollars in my pockets, and there

purchased, half cash, half credit, a small stock, which I brought

to Henderson. Chemin faisant,[13b] I came in contact with, and

was accompanied by, General Toledo, then on his way as a revolutionist

to South America. As our flatboats were floating one

clear moonshiny night lashed together, this individual opened

his views to me, promising me wonders of wealth should I decide

to accompany him, and he went so far as to offer me a colonelcy

on what he was pleased to call "his Safe Guard." I listened, it

is true, but looked more at the heavens than on his face, and in

the former found so much more of peace than of war that I concluded

not to accompany him.

When our boats arrived at Henderson, he landed with me,

purchased many horses, hired some men, and coaxed others, to

accompany him, purchased a young negro from me, presented

me with a splendid Spanish dagger and my wife with a ring, and

went off overland toward Natchez, with a view of there gathering

recruits.

I now purchased a ground lot of four acres, and a meadow of

four more at the back of the first. On the latter stood several

buildings, an excellent orchard, etc., lately the property of an

English doctor, who had died on the premises, and left the

whole to a servant woman as a gift, from whom it came to me as

a freehold. The pleasures which I have felt at Henderson, and

under the roof of that log cabin, can never be effaced from my

heart until after death. The little stock of goods brought from

Louisville answered perfectly, and in less than twelve months I

had again risen in the world. I purchased adjoining land, and

was doing extremely well when Thomas Bakewell came once

more on the tapis, and joined me in commerce. We prospered

at a round rate for a while, but unfortunately for me, he took it

into his brain to persuade me to erect a steam-mill at Henderson,

and to join to our partnership an Englishman of the name of

Thomas Pears, now dead.

Well, up went the steam-mill at an enormous expense, in a

country then as unfit for such a thing as it would be now for me

to attempt to settle in the moon. Thomas Pears came to Henderson

with his wife and family of children, the mill was raised, and

worked very badly. Thomas Pears lost his money and we lost

ours.

It was now our misfortune to add other partners and petty

agents to our concern; suffice it for me to tell you, nay, to assure

you, that I was gulled by all these men. The new-born Kentucky

banks nearly all broke in quick succession; and again we started

with a new set of partners; these were your present uncle N. Berthoud

and Benjamin Page of Pittsburg. Matters, however, grew

worse every day; the times were what men called "bad," but I

am fully persuaded the great fault was ours, and the building

of that accursed steam-mill was, of all the follies of man, one of

the greatest, and to your uncle and me the worst of all our pecuniary

misfortunes. How I labored at that infernal mill! from

dawn to dark, nay, at times all night. But it is over now; I am

old, and try to forget as fast as possible all the different trials of

those sad days. We also took it into our heads to have a steamboat,

in partnership with the engineer who had come from

Philadelphia to fix the engine of that mill. This also proved an

entire failure, and misfortune after misfortune came down upon

us like so many avalanches, both fearful and destructive.

About this time I went to New Orleans, at the suggestion of

your uncle, to arrest T — — B — — , who had purchased a steamer

from us, but whose bills were worthless, and who owed us for the

whole amount. I travelled down to New Orleans in an open

skiff, accompanied by two negroes of mine; I reached New

Orleans one day too late; Mr. B — — had been compelled to

surrender the steamer to a prior claimant. I returned to Henderson,

travelling part way on the steamer "Paragon," walked from

the mouth of the Ohio to Shawnee, and rode the rest of the

distance. On my arrival old Mr. Berthoud told me that Mr.

B — — had arrived before me, and had sworn to kill me. My

affrighted Lucy forced me to wear a dagger. Mr. B — — walked

about the streets and before my house as if watching for me, and

the continued reports of our neighbors prepared me for an encounter

with this man, whose violent and ungovernable temper

was only too well known. As I was walking toward the steam-mill

one morning, I heard myself hailed from behind; on turning,

I observed Mr. B — — marching toward me with a heavy club in

his hand. I stood still, and he soon reached me. He complained

of my conduct to him at New Orleans, and suddenly

raising his bludgeon laid it about me. Though white with

wrath, I spoke nor moved not till he had given me twelve severe

blows, then, drawing my dagger with my left hand (unfortunately

my right was disabled and in a sling, having been caught and

much injured in the wheels of the steam-engine), I stabbed him

and he instantly fell. Old Mr. Berthoud and others, who were

hastening to the spot, now came up, and carried him home on a

plank. Thank God, his wound was not mortal, but his friends

were all up in arms and as hot-headed as himself. Some walked

through my premises armed with guns; my dagger was once

more at my side, Mr. Berthoud had his gun, our servants were

variously armed, and our carpenter took my gun "Long Tom."

Thus protected, I walked into the Judiciary Court, that was then

sitting, and was blamed, only, — for not having killed the scoundrel

who attacked me.

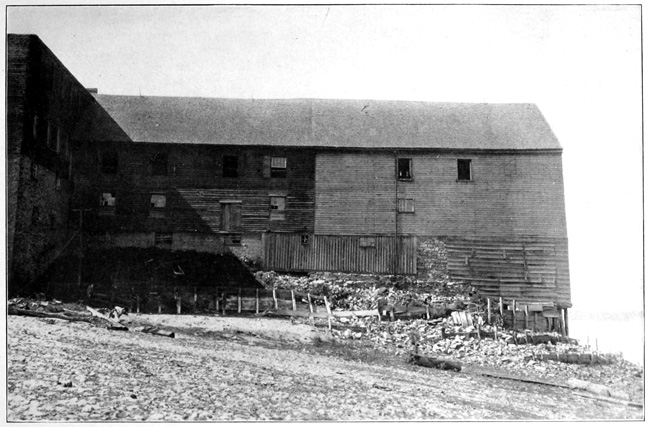

|

|

AUDUBON'S MILL AT HENDERSON, KENTUCKY.

NOW OWNED BY MR. DAVID CLARK.

|

The "bad establishment," as I called the steam-mill, worked

worse and worse every day. Thomas Bakewell, who possessed

more brains than I, sold his town lots and removed to Cincinnati,

where he has made a large fortune, and glad I am of it.

From this date my pecuniary difficulties daily increased; I had

heavy bills to pay which I could not meet or take up. The

moment this became known to the world around me, that moment

I was assailed with thousands of invectives; the once wealthy

man was now nothing. I parted with every particle of property

I held to my creditors, keeping only the clothes I wore on that

day, my original drawings, and my gun.

Your mother held in her arms your baby sister Rosa, named

thus on account of her extreme loveliness, and after my own sister

Rosa. She felt the pangs of our misfortunes perhaps more

heavily than I, but never for an hour lost her courage; her brave

and cheerful spirit accepted all, and no reproaches from her

beloved lips ever wounded my heart. With her was I not always

rich?

Finally I paid every bill, and at last left Henderson, probably

forever, without a dollar in my pocket, walked to Louisville alone,

by no means comfortable in mind, there went to Mr. Berthoud's,

where I was kindly received; they were indeed good friends.

My plantation in Pennsylvania had been sold, and, in a word,

nothing was left to me but my humble talents. Were those

talents to remain dormant under such exigencies? Was I to see

my beloved Lucy and children suffer and want bread, in the

abundant State of Kentucky? Was I to repine because I had

acted like an honest man? Was I inclined to cut my throat in

foolish despair? No!! I had talents, and to them I instantly

resorted.

To be a good draughtsman in those days was to me a blessing;

to any other man, be it a thousand years hence, it will be a blessing

also. I at once undertook to take portraits of the human

"head divine," in black chalk, and, thanks to my master, David,

succeeded admirably. I commenced at exceedingly low prices,

but raised these prices as I became more known in this capacity.

Your mother and yourselves were sent up from Henderson to our

friend Isham Talbot, then Senator for Kentucky; this was done

without a cent of expense to me, and I can never be grateful

enough for his kind generosity.

In the course of a few weeks I had as much work to do as I

could possibly wish, so much that I was able to rent a house in

a retired part of Louisville. I was sent for four miles in the

country, to take likenesses of persons on their death-beds, and so

high did my reputation suddenly rise, as the best delineator of

heads in that vicinity, that a clergyman residing at Louisville (I

would give much now to recall and write down his name) had

his dead child disinterred, to procure a fac-simile of his face,

which, by the way, I gave to the parents as if still alive, to their

intense satisfaction.

My drawings of birds were not neglected meantime; in this

particular there seemed to hover round me almost a mania, and I

would even give up doing a head, the profits of which would have

supplied our wants for a week or more, to represent a little citizen

of the feathered tribe. Nay, my dear sons, I thought that I now

drew birds far better than I had ever done before misfortune intensified,

or at least developed, my abilities. I received an invitation

to go to Cincinnati,[14] a flourishing place, and which you

now well know to be a thriving town in the State of Ohio. I was

presented to the president of the Cincinnati College, Dr. Drake,

and immediately formed an engagement to stuff birds for the

museum there, in concert with Mr. Robert Best, an Englishman

of great talent. My salary was large, and I at once sent for your

mother to come to me, and bring you. Your dearly beloved

sister Rosa died shortly afterward. I now established a large

drawing-school at Cincinnati, to which I attended thrice per week,

and at good prices.

The expedition of Major Long[15] passed through the city soon

after, and well do I recollect how he, Messrs. T. Peale,[16] Thomas

Say,[17] and others stared at my drawings of birds at that time.

So industrious were Mr. Best and I that in about six months we

had augmented, arranged, and finished all we could do for the

museum. I returned to my portraits, and made a great number

of them, without which we must have once more been on the

starving list, as Mr. Best and I found, sadly too late, that the

members of the College museum were splendid promisers and

very bad paymasters.

In October of 1820 I left your mother and yourselves at Cincinnati,

and went to New Orleans on board a flat-boat commanded

and owned by a Mr. Haromack. From this date my journals

are kept with fair regularity, and if you read them you will easily

find all that followed afterward.

In glancing over these pages, I see that in my hurried and

broken manner of laying before you this very imperfect (but perfectly

correct) account of my early life I have omitted to tell you

that, before the birth of your sister Rosa, a daughter was born at

Henderson, who was called, of course, Lucy. Alas! the poor,

dear little one was unkindly born, she was always ill and suffering;

two years did your kind and unwearied mother nurse her with all

imaginable care, but notwithstanding this loving devotion she

died, in the arms which had held her so long, and so tenderly.

This infant daughter we buried in our garden at Henderson,

but after removed her to the Holly burying-ground in the same

place.

Hundreds of anecdotes I could relate to you, my dear sons,

about those times, and it may happen that the pages that I am

now scribbling over may hereafter, through your own medium, or

that of some one else be published. I shall try, should God

Almighty grant me life, to return to these less important portions

of my history, and delineate them all with the same faithfulness

with which I have written the ornithological biographies of the

birds of my beloved country.

Only one event, however, which possesses in itself a lesson

to mankind, I will here relate. After our dismal removal from

Henderson to Louisville, one morning, while all of us were sadly

desponding, I took you both, Victor and John, from Shippingport

to Louisville. I had purchased a loaf of bread and some apples;

before we reached Louisville you were all hungry, and by the

river side we sat down and ate our scanty meal. On that day the

world was with me as a blank, and my heart was sorely heavy, for

scarcely had I enough to keep my dear ones alive; and yet through

these dark ways I was being led to the development of the talents

I loved, and which have brought so much enjoyment to us all,

for it is with deep thankfulness that I record that you, my sons,

have passed your lives almost continuously with your dear mother

and myself. But I will here stop with one remark.

One of the most extraordinary things among all these adverse

circumstances was that I never for a day gave up listening to the

songs of our birds, or watching their peculiar habits, or delineating

them in the best way that I could; nay, during my deepest

troubles I frequently would wrench myself from the persons

around me, and retire to some secluded part of our noble forests;

and many a time, at the sound of the wood-thrush's melodies

have I fallen on my knees, and there prayed earnestly to our God.

This never failed to bring me the most valuable of thoughts and

always comfort, and, strange as it may seem to you, it was often

necessary for me to exert my will, and compel myself to return to

my fellow-beings.

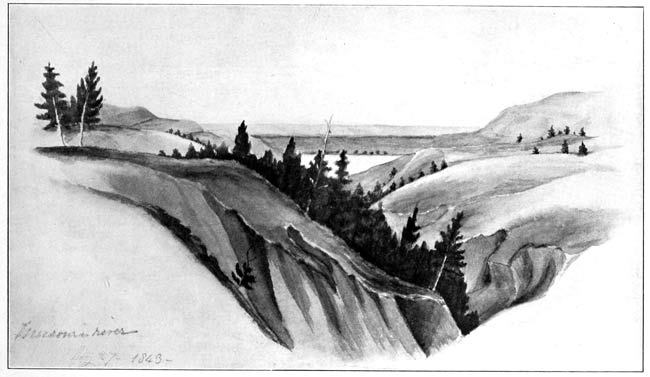

To speak more fully on some of the incidents which

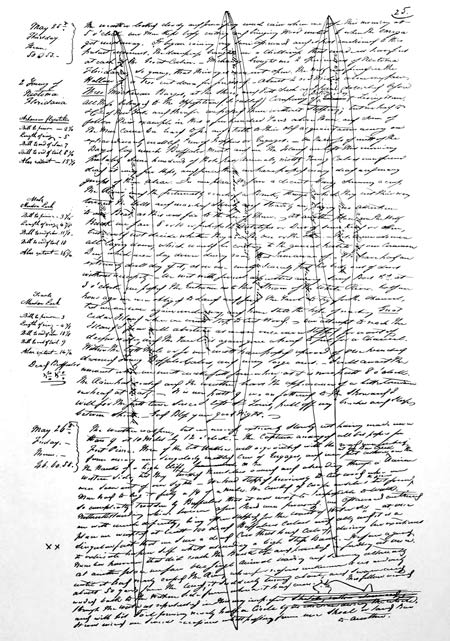

Audubon here relates, I turn to one of the two journals

which are all that fire has spared of the many volumes

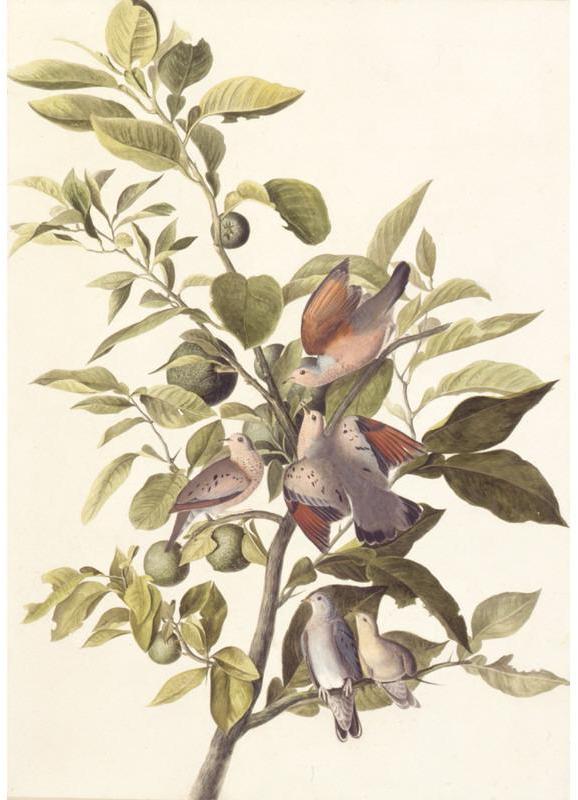

which were filled with his fine, rather illegible handwriting