Anthology

of Louisiana Literature

John Augustin.

“The Oaks: The Old Duelling-Grounds of New Orleans.”

[From an article written by the author in 1887 for one of the newspapers of the

Crescent City and reproduced in ‘The Louisiana Book,’ 1894. Copyright, Thomas

McCaleb. It recalls some of the most thrilling tragedies in the history of the Creole

State, and its charm of style no less than its piquancy of interest, makes it a classic

of literature. See Vol. XV, p. 13 for a sketch of the author, who was both a writer

of Attic prose and a poet of exceptional gifts.]

Under the wide-spreading oaks of ancient Gaul, the

consecrated Druids, with golden sickle, cut the holy mistletoe with

which they sanctified their foreheads in the stern celebration of

their rites of blood. Happy was the victim offered in sacrifice;

for to die was to know, and to go forward knowing, in that

eternity of progressive development and bliss which ended in the

perfection of knowledge. It also meant the sublime identification

with nature on some ultimate star, radiant with omniscience

and musical with the rhythmic pulsations of eternal peace.

I cannot sit of a calm evening under the pensive oaks,

from whose gray beards, waving under the sway of the

breeze, comes a murmur as of a prayer and prophecy, without

reverting to that stern yet hopeless creed of Runic times,

which held knowledge to be the supreme good, and pointed

to sacrificial death as the first step to its acquirement.

It is curious that rites of blood should have been the

foundation of every religion. Even the meek and divine

Jesus found it necessary to die on the cross that humanity

might be saved. There is a problem full of yet unfathomed

meaning in this perpetual theory of blood atonement. Else

why the traditional sanctity of war and the undying fame

which attaches to successful military chieftains, loftier than

the apotheosis of saints? Why the glamour around the

heroes of knight-errantry, riding alone and full-armed in

search of blood to spill for the redressing of wrong? Why

the trial by single combat, introduced by Holy Church and

but recently fallen into disfavor?

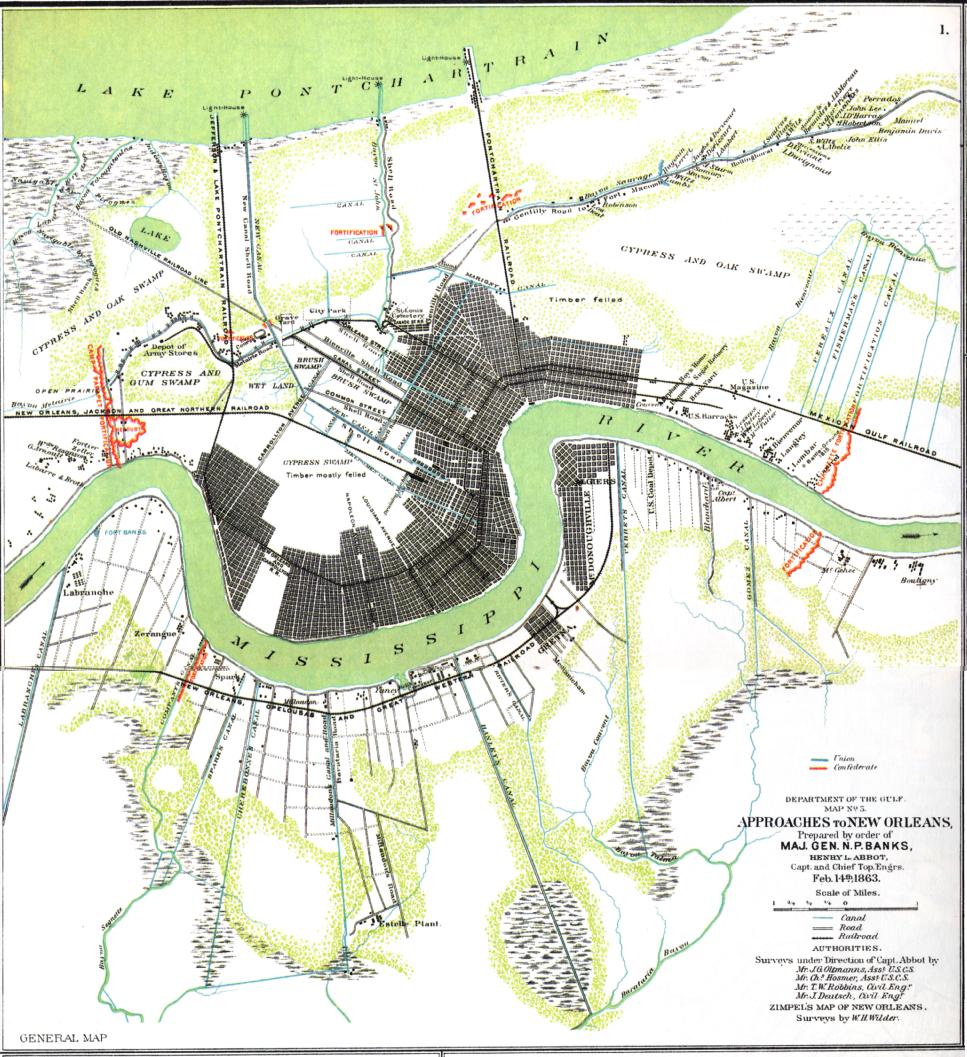

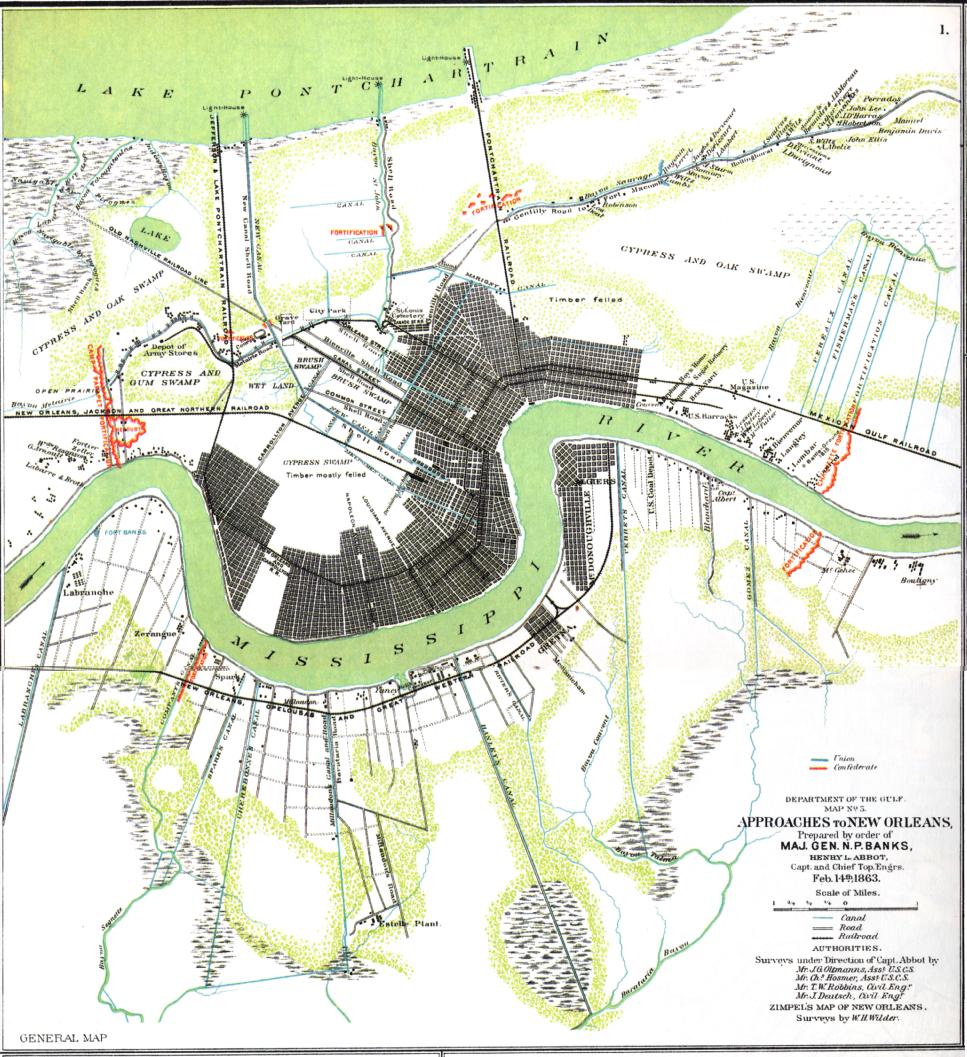

Where the Metaire ridge, slightly undulating, barely

breaks the monotonous flatness of the hazy landscape, standing

near the dilapidated tomb of Louis Allard, such thoughts

crossed the mind of the writer as he gradually became

enveloped in the dark shadows which the rays of the setting

sun slanted from the oaks of the Lower City Park.

These

oaks were formerly known as the “Chênes d’Allard” otherwise

called the “Metaire oaks.” These, also, in their time,

witnessed rites of blood, and lent their protecting shade to

many a preconcerted, solemn and deadly encounter between

man and man.

From the terminus of the Bayou Road street car line in

New Orleans, at the foot of Esplanade Street, after crossing

the bridge over Bayou St. John, a short walk brings the

visitor in front of a magnificent little forest of gigantic live oaks.

It is the lower City Park, in former days a wooded plantation

belonging to Louis Allard.

This gentleman, who was a man of letters and a poet,

owned all that tract of land extending from the Bayou St.

John to the Orleans Canal, and from the Metaire Road to

the old toll-gate. That portion of it which is now called the

Lower City Park was purchased previous to his death by the

millionaire philanthropist, John McDonogh, at a sale made

for foreclosure of mortgage by the Citizens’ Bank of Louisiana.

McDonogh left it by will to the cities of New Orleans

and Baltimore, and the city of New Orleans acquired it in

full ownership at the partition sale.

During the latter portion of his life, Allard, who, being

a poet, was an indifferent business man, crippled in health

and fortune, was permitted, after the sale, by special agreement,

to continue his occupation of the place. There he used

to spend all his days, reclining in an arm-chair under his

beloved oaks, reading his favorite authors, and dreaming of

what might have been. He died not long after the sale of

his property, and, in compliance with his last wish, he lies

buried in the old place under the very oak where the last

years of his life had been passed.

A few bricks, uncared for, a tomb burst open by time and ruthless

hands, protected from the sun and rain by the faithful boughs of his

favorite oak, mark his resting-place.

To one coming from the Metairie Road, this tomb is on a wooded

plain in the rear, well to the right of the park proper, from which it

is divided by a small, swampy ravine, crossed by a primitive wooden

bridge. From its site, glancing obliquely to the left, the legendary

oaks rear their majestic heads in solemn grandeur.

Scarcely half a century has passed over these centenarians since

Louis Allard, in the full vigor of youth, walked under their branches.

Allard is dead. McDonogh, who purchased from him, is also gone,

leaving behind him, as undying monuments, the public schools with

which he has gifted the city. A terrible war between two sections of

our great country has changed and revolutionized the entire social

system of the South. But the grand oaks are still the same, solemnly

brooding at night over memories of the past, Perhaps their gnarled

trunks are somewhat more rugged; but they are as majestic and

vigorous as ever, their green boughs throwing back the sunlight

with all the brightness and elasticity of everlasting youth.

But the fame of the Metaire oaks does not rest upon the

poetry or scholarly accomplishments of their former proprietor,

nor upon the memory of the philanthropist who bequeathed

them to the city nor upon the sturdy strength or the

perennial youth of their green branches; the great interest

that lingers among them comes from the memories which

they recall; it is the witchery of tradition which makes them

immortal.

The antithetic lights and shades of their leafy arcades,

typical of a state of society where tragedy and gaiety walked

side by side in chivalrous converse, take back our memories

to a period scarce fifty years remote, when it was an everyday

occurrence to see under these very branches a meeting

of adversaries in mortal combat, with rapier or pistol, sabre

or shot-gun.

At that time, New Orleans, though even then to a degree

cosmopolitan, was essentially a Creole city, and under the full

influence of the traditions which governed that high-strung

and chivalrous race. The descendants of the early possessors

of the soil, many of whom were of aristocratic blood,

had grown up with the more plebian sons of the other settlers,

and what, with education in common, received in Europe and

at the Collège d’Orléans in this city, what with intermarriages,

the habit of command acquired from the ownership

of slaves, and the refining influence of well employed leisure,

formed a sort of aristocracy from which the South derived

some of its brightest intellects. It was a nobility less of birth

than of manners, breeding, education and tradition.

Besides, life was easy in New Orleans at that time, for

the city was not only a great place of import and export

from its position near the Gulf, but owing to its river facilities,

not yet antagonized by the railroads, it controlled with

scarcely any competition the whole trade of the West.

Money

was therefore acquired without the absorbing and deleterious

consequences of incessant labor; there was time left to

merchants and clerks for mental culture, and imagination was not,

by the nature of things, excluded from the active world.

The

women, bred at home, under a mother’s jealous surveillance,

educated by the best private teachers or at the renowned

Convent of the Ursuline Nuns, were versed in arts and in

letters. Invariably treated with the most deferential gallantry

by the men, none of whom were ever known to smoke or

otherwise demean themselves in the presence of a lady, they

had naturally acquired manners of great refinement and

distinction.

The world and society therefore were of courtly

brilliancy. Merchants and lawyers were incidentally poets

and wits, and the ladies accomplished musicians.

Over all

this: over men and women, there ruled a supreme sense of

dignity and honor, maintained by the strictest and most

unflinching public opinion.

At that time bankrupts committed

suicide, and women fallen from virtue disappeared and were

never heard from. There was no compromise with honor;

society did not permit it.

Under this moral condition of affairs, the punctilio among

men was strict even to exaggeration. The least breach of

etiquette, the most venial sin against politeness, the least

suspicion thrown out of unfair dealing, even a bit of

awkwardness, were causes sufficient for a cartel,

which none dared refuse.

The acceptance, however, did not mean, that the quarrel

must inevitably be settled on the field. The seconds, two on

each side, discussed the quarrel dispassionately, sometimes

with the assistance of mutual friends, and often arrived at an

amicable and honorable settlement.

A blow was strictly

forbidden, and sufficient to debar the striker from the privilege

of the duello. A gentleman who would so far forget himself

as to strike another was exposed to the ignominy of being

refused a meeting. Some who have so far lost their self-possession

have been known to submit to the greatest humiliation

in order to obtain from their adversary an exchange of

shots or a crossing of swords. Nor was even an insult

permitted to go beyond a certain decorum of form. Experienced

friends, well versed in the law and precedents of the code,

settled beforehand every nice point, so that the adversaries

met under the oak in full equality morally and socially.

How many a bloody combat originated in a ballroom,

where the cause of the difficulty passed unnoticed by all!

Said a gentleman to a much-courted lady, dancing in a

brilliant ballroom:

“Honor me with half of this dance?”

“Ask monsieur,” answered the lady, “it belongs to him.”

“Never,” spoke the dancer when appealed to, whirling past

in the waltz, and who had just caught the words softly spoken

by smiling lips as he passed by.

“Ah,

vous êtes mal élevé.”

Not a word more was said that night between the two

gentlemen, though they subsequently met and bowed; but

early the next morning the flippant talker received a challenge,

and in the evening a neat coup droit under the oaks at the

Metaire.

So well recognized was the code by all who had any

pretensions to good breeding, that even judges on the bench

would resent an insult from lawyers at the bar. A typical

anecdote of the time is here given as exemplifying the

then existing feeling about the duello.

Judge Joachim Bermudez,

father of the present Chief Justice of the State,

while on the

bench, made a ruling against a certain lawyer, who objected

in rather unbecoming terms. He was ordered to sit down,

and refused; whereupon the judge ordered the sheriff to take

him into custody for contempt of court. Drawing a pistol,

the lawyer defied the sheriff, who feared to advance. The

judge, leaping from his bench, seized the lawyer by the arm

and handed him to a police officer, who led him to prison.

The judge soon after ordered his release.

That evening he received a challenge from the lawyer,

which was promptly accepted. On the field, the lawyer

offered to apologize; but that was forbidden by the code. Never,

on the field. The judge absolutely refused any apology, and

the lawyer had to leave the country. He could not have

practiced, after this, before the courts of the State.

The oaks of the Metaire, or “Chênes d’Allard,” did not

become a place of rendezvous for duellists until the year 1834.

Previous to this the favorite place for fighting was the

Fortin property, now the Fair Grounds. The fact is New Orleans

being then but sparsely built in the rear, there were a

number of convenient places close at hand where those who had a

stomach for battle could satisfy their cravings to their heart’s

content, without fear of interference. To say the truth,

interference was the exception. It is true that there existed

a law against duelling, but the practice was so strongly welded

in the customs of the people that the statute served only to

add the glamour of mystery and the flavor of forbidden fruit

to the other fascinations of the deadly game, and might as

well not have existed.

Things being so, it is not astonishing that New Orleans

should have been a favorite resort for professors of fence

or maîtres d’armes. Most

of these, having no further personal

value than their skill with the foils, lived in blood, wine,

and profligacy their circumscribed lives, between the cafés

and the salles

d’escrime, and even their names are now forever

forgotten. Others who pursued their calling as an honored

profession, acquired a certain standing in society, and old

residents love to talk over their skill in arms and their lovable

and manly traits. Others, again, have acquired fame for having

killed or having been killed in duels.

Among the latter were Marcel Dauphin, who was killed by A. Nora

in a duel with shotguns; Bonneval, who was killed by Keynard, also

a professional swordsman; L’Alouette, who killed Shubra, another

professor, and who was Pepe Bulla’s teacher of fence and subsequently

his associate; Thimecourt, who killed Poulaga, and of whom more

hereafter, as also about his confrère Monthiach; and more of the same

sort.

Among the former were E. Baudoin, a Parisian, who was very

popular and well esteemed; Émile Cazère, who had quite an aristocratic clientèle; and Gilbert Rosière, familiarly called by his pupils

Titi Rosière, perhaps the most popular among all the fencing-masters

that ever came to New Orleans. I must not forget Basile Croquère,

who, though a mulatto, was such a fine blade that many of the best

Creole gentlemen did not hesitate, notwithstanding the strong

prejudice against color, to frequent his salle d’armes, and even cross swords

with him in private assauts.

Gilbert Rosière, whose son Gustave, himself an excellent

swordsman, followed the Gardes d’Orléans to the plain of

Shiloh at General Beauregard’s call, is the maîtres d’armes

who has left the best and certainly the most vivid souvenirs.

All of us, who were young before the war, remember the gay,

whole-souled, though irascible fencing master. A native of

Bordeaux, he had come to New Orleans when a very young

man, to make his fortune at the bar. But he was of a wild

disposition and fell in with a wild set; so he dropped the Code

Napoleon for the Code of Honor, became a leader in all the

escapades and devil-may-care adventures of the jeunesse dorée

of that time, and turned fencing master. During the

Mexican war he earned a fortune, by teaching his art to officers,

but it was squandered as lightly as made. Brave and generous

to a fault he was every one’s friend, and, contradictory as it

may seem, this hero of seven duels in one week was, in some

respects, of womanly tenderness. He would fight with men

to the bitter death, but would not hurt a defenceless thing,

woman, child or fly.

He was passionately fond of music and nervously

sensitive to its melting impressions. A great frequenter of the

opera, his superb head could be seen almost every night

towering above the others in the parquette. On one occasion,

deeply touched by the pathos of a well-sung cantilena, he

wept audibly. An imprudent neighbor laughed, but his

amusement was of short duration, for Rosière had scarcely

noticed it than his tenderness turned to anger.

“C’est vrai,” he

said, “je pleure, mais je donne aussi des

callottes.”

By this time the man’s face was already slapped, and the

next day a flesh wound had taught him that it is not always

good to laugh. Well might Rosière have exclaimed with the

old German knight

at the close of his career:

“I have lived my life, I have fought my fight,

I have drunk my share of wine;

From Trier to Koln there never was knight

Led a merrier life than mine!”

It was in the spring of 1840. There was a grand assaut

d’armes between the professors of the old “Salle St. Phillipe,”

which was filled with the gilded youth of old-time New Orleans.

None but brevetted experts, who could show a diploma,

were allowed to participate. The valorous Pepe Lulla,

now famous for a large number of successful duels, then a

vigorous young man, skilled in the use of weapons, was refused

the privilege of a bout because he had no papers to

show.

An Italian professor of counterpoint, named Pulaga, a

man of magnificent physique and herculean strength, was

there holding his own with the broadsword, and bidding defiance to all comers.

Captain Thimécourt, a former cavalry officer, opposed and

defeated him. The humiliation was too much for the Italian’s

pride, and he remarked with a sneer that Thimécourt was a

good tireur de salle.

“Qu’a cela ne

tienne,” at once exclaimed the

soldier, “let

us adjourn to the field.”

Without further parley, they took rendezvous for the oaks,

and there Thimécourt cut his adversary to pieces.

This same assaut d’armes was the cause of Pepe Lulla’s challenging

a French professor named Grand Bernard, who had insisted upon his

producing a diploma before crossing swords with him in the salle

d’armes. They fought with broadswords, and Pepe with his good

blade, though he had no diploma, opened the master’s

flank in two

places.

Thimécourt was one of the most noted professors of fence of the

period, his favorite weapon being the broadsword, in the management

of which he excelled. An admirable expounder of the counterpoint,

he was not otherwise highly cultivated in any manner, and delighted

principally in broils and battle.

Another well-known and contemporaneous professor was a German

swordsman named Monthiach. He was tall, fleshy, and muscular, and

at the same time the best-natured fellow in the world, but of course

always ready for a duel, particularly with a professor. Professors of

all kinds have always been, more or less, jealous of each other, but the

maitres d’armes of that period were peculiarly and aggressively so.

Well, Thimécourt and Monthiach had some slight difference about

a coup, and, naturally, as they disagreed completely, the only way to

come to an understanding was to fight it out.

They fought with broadswords, because it was about that weapon

that they had disagreed. The duel was short, sharp, and decisive.

At the first pass, Monthiach made a terribly vicious cut at his

adversary, evidently intended to cut off his

head at one blow. The coup

was admirably conceived and executed.

Thimécourt, who had his own idea, did not parry with his sword,

but dodged. His hat was cut clear in two, Monthiach’s blade grazing

his scalp. At the same time the Frenchman, passing under his

adversary’s sword, opened his breast with a splendid coup de pointe. The

seconds interfered. The gash was a frightful one, and the blood flowed

freely, yet the German professor insisted upon going on with the fight.

The seconds, however, would not permit it.

They had taken no surgeon with them, and Monthiach, to the

horror of the bystanders, pulled out some tow which he had in his

pocket, and packing his wound with it, to stop the flow of blood,

walked home in a frenzy of anger, cursing at the seconds who had

stopped the fight, for, as he said, it was a beautiful coup, and he would

have assuredly chopped off Thimécourt’s head if he had had a chance

to renew it. Three days after he was on parade, marching, musket in

hand, in the ranks of the “Fusiliers,” a German militia company, then

commanded by Captain Daniel Friedrich.

There was not a day passed without one or two encounters at the

oaks or elsewhere. The spirit of the age might have been expressed

in Don Cæsar de Bazan’s terse saying in Victor Hugo’s

Ruy Blas:

“Quand je tiens un bon duel je ne le lache pas.”

Old citizens who lived in the neighborhood of the oaks say that

for a time it was a daily procession of pilgrims to this bloody Mecca.

Some of them walked or rode back, others were carried home for

burial, but once on the field, honor required that some blood should be

spilt. Sometimes it was a drop only, sometimes a draining of the

veins.

The following double anecdote is typical of the manners

and customs of the period:

Mr. Hughes Pedesclaux was a tall, muscular, and athletic

young man, whole-souled and popular, but somewhat

quick-tempered; brave as all of his race, and skilled in the use of

arms.

Mr. Donatien Augustin was a tall, slim young lawyer,

a great student, fond of his profession, but fond also

of the military. Both were attached to the “Cannoniers d’Orléans,”

a crack artillery company of those days. Augustin

had just been made a lieutenant, and was rather proud of his

uniform and trailing artillery sabre. Parade had just been

dismissed; Pedesclaux came up to his friend Augustin, (a child

whom he had spanked and bullied at the “Collège

d’Orléans”),

and jovially, but irreverently, gave a deprecatory kick to the

swaggering weapon, saying:

“What could you do with this thing?”

Quick as a flash came the retort:

“Follow me a few paces to some quiet place, and I will

show you!”

Not a word more was said. Each man picked up two

friends to act as seconds, and forthwith, followed by the

delighted crowd, eager for the sight of a scrimmage, marched to

the scene of combat.

In those days New Orleans was not extensively built, and

fighters were not particular about time or place. A

convenient spot was soon reached, the adversaries doffed their

uniforms, stripped to their shirt sleeves, and drew their weapons.

The seconds, after placing them in position, and enjoining

each to do his duty as a gentleman, uttered the sacramental

words:

“Allez, messieurs,”

and to it they went with a will.

Pedesclaux was in the

full vigor of manhood and skilled in sword-play; Augustin

was a mere youth, with little experience in arms, but very

active and willing. As luck would have it, after a few passes,

he cut his redoubtable adversary in the sword-arm.

The

seconds interfered; there was a great shaking of hands, and

the incident ended in a gay and plentiful dinner at Victor’s

on Toulouse Street.

Some time afterward, Pedesclaux had a quarrel with a

retired French cavalry officer, reputed as a duellist.

The cartel was passed between

the two parties with due solemnity, and the Frenchman,

having the choice of weapons, selected broadswords, on

horseback. They fought on a plain, in the rear of the second

district, known as

“La Plaine Raquette,”

on account of the

peculiar game of ball which used to be played there.

An eye-witness says: “It was a handsome sight. The

adversaries were mounted on spirited horses, and stripped to

the waist. As they

rode up to each other, nerved for the combat, their respective muscu-

lar development and the confidence of their bearing gave promise of

an interesting fight. The Frenchman was heavy and somewhat

ungainly, but his muscles looked like whip-cord, and his broad, hairy

chest gave evidence of remarkable strength and endurance.

Pedesclaux, somewhat lighter in weight, was admirably proportioned, and

his youthful suppleness seemed to more than counterbalance his

adversary’s brawny but somewhat rigid manhood.

“A clashing of the steel, which drew sparks

from the blades, and the two adversaries crossed and passed

each other by unhurt. In a moment, both horses had been

vaulted to face each other by the expert riders, and the

enemies met again. A terrible head blow from the Frenchman

would now have cleft Pedesclaux to the shoulder-blade, if

his quick sword had not warded off the death stroke. It was

then, with lightning rapidity, before his adversary could

recover his guard, which had been disturbed by the momentum

of his blow, the Creole, by a rapid half-circle, regained his,

and with a well directed

coup

de pointe à droite

plunged his blade

through the body of the French officer, who reeled in his

saddle, fell, and was picked up senseless and bleeding by his

friends. He died soon afterward.”

Another duel on horseback, which was much talked about at the

time, was fought with cavalry sabres by Alexander Cuvillier and Lieu-

tenant Schomberg of the United States Cavalry. They had a quar-

rel, which terminated in a street fight, the result of which was that

Cuvillier was wounded by Schomberg with a sword cane.

As soon as he had sufficiently recovered from his injuries, Cuvillier

sent Messrs. Eniile Lasere and Mandeville de Marigny with a cartel to

Schomberg, who immediately accepted it, choosing broadswords, on

horseback. They fought on D’Aquin Green, a little above Carrollton.

After the second pass, Cuvillier made a vicious cut at his adversary,

which, falling short, or being otherwise miscalculated, severed the

jugular vein of Schomberg’s horse, that fell and died on the spot.

This put a stop to the duel.

Sometime afterward Alexander Cuvillier died, and his brother,

Adolphe Cuvillier, who had charge of his succession, received a letter

from Schomberg. This letter recalled the duel, saying that the horse

which had been killed in the fight belonged to his Colonel, that it was

worth five hundred dollars, which he had had to reimburse, and

hinting that it would certainly be proper for Mr. Cuvillier to pay him

back at least half that amount. Mr. Adolphe Cuvillier wrote back,

saying that his brother was dead, and that he had accepted the

succession, and had charge of all his brother’s business, this quarrel, of

course, included; that he would cheerfully send a check for two

hundred and fifty dollars, as testamentary executor of his brother, and as

such, would also be exceedingly willing to pay full price for another

horse if the lieutenant agreed to renew the fight with him. He never

received any answer.

It would seem that Donatien Augustin, who was later

in his life judge of one of the district courts, General of the

Louisiana Legion, and one of the most highly esteemed and

conservative of our citizens, was lucky in the few duels in

which the temper of the period caused him to be engaged.

Two of his adversaries each killed his man in subsequent

encounters. Pedesclaux, as above stated, and Saintmanat,

with whom he harmlessly exchanged one or two pistol shots in a

slight quarrel, who afterward killed Azenor Bosque in a duel, also

with pistols, and subsequently, with similar weapons, grievously

wounded Commodore Riebaud.

The following affair, which he had with

Alexander Grailhe, is told here on account of the interest

connected with Grailhe’s luck in a subsequent encounter. The

cause of the quarrel is at this day of small concern. Suffice

it to say that after the insult, or rather provocation, (for in

those days gentlemen rarely insulted), and each was sure that

a deadly meeting was to follow, the two gentlemen travelled

in a carriage with ladies, who wondered after the duel, at

their mutual affability during the trip.

They met with

colichemardes

at the oaks. Grailhe, highly bred, and under,

as he deemed, grevious provocation, as soon as the weapons

had been crossed, and the impressive Allez, messieurs, had

been given, lost his temper and furiously charged his

antagonist. Augustin, cool, collected and agile, parried and evaded

each savage thrust, till finally by a

temps

d’arret judiciously

interpolated into a terrific lunge of Grailhe, pierced him

through and through the chest.

One of the lungs had been perforated. Grailhe remained

for a long time between life and death, and at last came out

of his room, but bent forward like an old man. The

physicians despaired of his life, for an internal abscess, which could

scarcely be reached, had formed; and it was now for the

wounded man only a question of time and chance. The latter

divinity came to his rescue in a most remarkable and original

manner.

He quarreled with Colonel Mandeville de Marigny, and

they met at the oaks. The weapons were pistols at fifteen

paces, two shots each, advance five paces, and fire at will.

Grailhe advanced three or four steps, Marigny remaining

perfectly still, and both fired simultaneously. Grailhe fell,

pierced through the body, exactly in the place of his former

and unhealed wound, the ball lodging directly against the

spinal column. Marigny advanced, pistol in hand, cool as a

piece of marble, to the utmost limit marked out, when Grailhe,

who was suffering dire pain, exclaimed:

“Achevez

moi!”

Marigny lifted his pistol high above his head and firing

into the air, said:

“I never strike a fallen enemy!”

Grailhe was carried home more a corpse than a living

man; but, sooth to say, the ball had pierced the smouldering

abscess that threatened his life, had opened an exit for its

poisonous accumulations, and the wounded man, some time

afterward, walked out of his room, as erect and stately as

ever. Thus for once did the messenger of death bring life

and health.

Poor Frank Yates was less fortunate in his affair with Joe

Chandler, some time in 1859. A lie, reported by an injudicious friend,

brought a cartel, and it was agreed that the young men should fight

with duelling pistols at ten paces. The fight was to take place in the

afternoon, under the oaks at the Metairie; but the duellists were

interfered with there by the police, so they repaired to a place

farther on, near Bayou St. John, whence they were again driven away

by the officers of the law. It was now getting late; a drizzling rain

had set in, and it was urgent to bring matters to an issue before

night; so principals and seconds jumped out of their carriages at a

place somewhere at the foot of Bienville Street, where preparations

were promptly made for the fight and the principals placed in position.

Night was coming on apace, and the drizzling rain added to the

gloomy and desolate appearance of the surroundings. The pistols

were loaded, handed to the principals, and the command given to fire.

Two shots were exchanged with no effect, and an attempt was made

by Chandler’s seconds to settle the matter; but this was resisted by

the opposite side, and a third shot became necessary. Both fired at

the same time, and Frank Yates fell. Chandler’s ball had struck him

in the side, ranging upward through the bowels. He died a few days

afterward.

The population of New Orleans has always been fond of music,

and particularly of the opera, which in its palmy days it lavishly

sustained. The Creoles, extreme in all things, carried this taste to

the limits of passion. Many a deadly duel grew out of simple

discussions over the merits of individual singers. It would take a

volume to recite the various quarrels that were engendered by the opera.

Journalistic critics, of course, who published their opinions, had to

bear the brunt and be ever ready to back an article with steel or lead.

Many still living, and even who would not like to be called old,

remember two delightful artistes who flourished here during the

season of 1857-58, under Mr. Boudousquie’s administration; namely,

Mlle. Bourgeois, a contralto of great dramatic talent, and Mme.

Colson, one of the wittiest and most fascinating of light soprani. It

must be added that Mme. Colson had replaced as

chanteuse légère

a

Mme. Préti-Baille, who was a very pretty woman, a singer of great

technical accomplishments, but cold as an icicle, and therefore not

popular with the general public. She was a great friend of Mile.

Bourgeois. It is useless to add that there was no love lost between

Mme. Colson and the contralto.

This Mlle. Bourgeois made it a point to show, on the occasion of

her benefit night, for which she had chosen Victor Massé’s

opera of

Galathée, when, instead of asking Mme. Colson, in whose

répertoire the title rôle undoubtedly

was, she went outside of the company,

and asked Mme. Préti-Baille, who was then in the city

giving music

lessons, to sing the part. The announcement created great feeling

among opera-goers, and was warmly discussed in the clubs. Mme.

Colson was very much liked and admired, and her partisans, feeling

outraged at the insult, as they deemed, thus put upon her, swore that

Préti-Baille would not be permitted to sing.

The friends of Bourgeois

swore on their side that it was not, after all, the woman’s fault, and

that those who hissed her would rue it. That threat was sufficient in

those days to create an army of hissers.

The matter, as before stated, was largely discussed at the clubs, on

the streets, and at the salle d’armes. In one of the latter places

Emile Bozonier and Gaston de Coppens, two of the most popular

young fellows of the day, were with a number of others practising

with foils, or lounging. Of course Bourgeois’ benefit night was the

topic of conversation. Some said that Préti-Baille

should be hissed,

others that it would be a shame. Bozonier said nothing (it is probable

that he did not care much one way or the other). Suddenly Coppens,

turning to him, said:

“What do you say about this, Bozonier?”

“I,” was the deliberate answer, “think that a man who goes to the

theatre for the purpose of hissing a woman is a blackguard and should

have his face slapped!”

Coppens grew pale.

“Do you know,” he retorted, “that I have proclaimed myself one

of those who will hiss that woman down?”

“No,” Bozonier replied, “but I nevertheless mean what I said.”

“Would you slap a man’s face who hisses on that occasion?”

“If he is close enough to me, I assuredly will,” answered Bozonier,

now thoroughly aroused and interested.

“Well, you will have your hands full,” said Coppens, and the

matter was dropped.

And so the benefit night came on. The opera house on Orleans

Street was crowded to suffocation, and it was evident, from the excited

and determined looks of the young men present, that a fire was

smouldering all through that audience. Mlle.

Bourgeois was the Pygmalion,

and nothing special happened until the

curtain covering the statue was

drawn aside and Galathée began to live and move.

Then there arose such an antagonistic cacophony of hisses from

one side, and applause from the other, as has rarely been heard in an

opera house. Cold as marble and all as white, but apparently unmoved,

the singer, amid the growing tumult, which never ceased till the curtain

fell, sang all her numbers undaunted, braver than any hero who ever

repelled an assault or led a charge. And so on all along, also, during

the second act and until the final drop of the curtain.

Little, indeed, did anybody that evening hear of Massé’s music,

most of the ladies, of course, having deserted long before the end. In

that encounter of hisses and plaudits several quarrels were picked up

by the young bloods, which ended at the oaks or elsewhere, but we

are now preoccupied with only one.

Coppens had hissed, and Bozonier had seen him, but they were

separated by a dense crowd; only their eyes met and a sign of

defiance was passed. A day or so afterward, Bozonier met Coppens, who

crossed over the street to him, smiling under a sneer, and accosted

him with:

“Well, Bozonier, what about those slaps?”

Bozonier was of herculean strength, and his answer was a buffet

which sent Coppens sprawling in the street. Quick as lightning, and

agile as a cat, Coppens got up and grasped for his weapons, but

Bozonier was too powerful for him, and soon had placed

it out of his power

to use either knife or pistol. A few days afterwards, Bozonier had

received a challenge, and being skilled neither in the use of rapier

nor pistol, chose cavalry sabres.

They fought at the oaks, within pistol shot of Allard’s tomb.

Bozonier was a trifle above the middle height, but remarkably

active and muscular. Coppens was small in stature, but wiry and of

feline activity. Both were dandies in dress and lions in courage.

In a twinkling the coats were on the grass. The principals were

placed in position, and the usual recommendations made by the seconds,

comprising the instructions that the fight was to last till one of

the adversaries should be completely disabled.

The first pass was terrible; Bozonier engaged Coppens in tierce,

made a feint, then taking advantage of the movement of his adversary

to parry, rapidly passed over his sword and made a swinging stroke

at him, which would inevitably have severed his head from his body,

had not Coppens, by a timely movement, warded off partly the effect

of the blow. But there was vigor to spare in the cut, for Coppens

fell, the blood spurting like water from a terrible gash on the cheek

and a severe cut in the chest.

It was lucky for him at that moment that Bozonier’s generous soul

prevented him following up his advantage, for he had his foe at his

mercy. He paused till Coppens rose. This rise was the spring of a

wounded tiger; a furious coup de pointe penetrated Bozonier’s

swordarm above the elbow, cutting the muscles and disabling him. Then

Coppens had it all his own way, though his plucky adversary did his

best, handicapped as he was by his now almost useless arm, which

could scarcely hold the weapon. The seconds did not see his terrible

position in time, neither could his furious foe appreciate it, and before

the former could interfere, Bozonier had received two deep cuts in the

chest, a terrible slash in the left arm, and a fearful coup

de pointe in

the side. He was bleeding at every pore.

Happily for his many friends, his strong constitution saved him,

and he lives yet, though four years of war, superadded to this fearful

hashing, have left but a comparative wreck from his once splendid

physique.

Coppens, who was afterward colonel of the Louisiana Zouaves,

died like a soldier at the battle of Seven Pines, flag in hand, forty

yards in front of his command, while gallantly leading a Florida

regiment, after his own had been cut to pieces.

At the period referred to, the opera season lasted six months, and

such was the inclination of our people for this kind of music that the

interest remained unabated to the end. So a month or so after the

duel just narrated, a violent critique from the pen of Emile Hiriart,

who was writing for the True Delta, appeared in the columns of that

sheet. Hiriart, who was a very trenchant writer, had smote, as it

seems, right and left, and spared no one.

The very same day he received two challenges — one from Mr.

Placide Canonge, now the highly polished art and musical critic of

the New Orleans Bee, and one from Mr. E. Locquet, both of whom

had taken exceptions to the article. He accepted both.

Mr. Canonge’s challenge having priority, he was first attended to.

They fought with pistols at ten yards, and exchanged three shots,

each shot of Hiriart’s cutting Mr. Canonge’s clothes, and that

gentleman

receiving those leaden warnings with the utmost composure and

the sweetest of smiles. Their seconds thereupon withdrew them, and

the matter between them was settled.

A few days after, Hiriart was out again with his faithful seconds,

this time to answer Locquet’s challenge.

There was more underlying this meeting than the conventional

chivalry of the “point of honor.” There was hate between the two,

and a deadly purpose, as was evidenced by the choice of weapon —

double-barrelled shotguns loaded with ball, distance forty paces. In

the hands of Creole gentlemen, who were all practised hunters, this

weapon was the deadliest. It was rare that both parties survived an

encounter of this kind. Often the two adversaries were killed, and

almost invariably one was carried away from the field a corpse.

Seconds rarely permitted the use of the shotgun, unless under the

gravest provocation.

The preliminaries of a duel are always solemn, but here an

atmosphere of awe pervaded the scene,

as, in silence, the ground was

measured, the principals placed

in position, the weapons loaded and handed

to them by their seconds. Both were calm and apparently unmoved;

but the set chin, the firm lip, the eye coldly gleaming, told of deadly

passion and intent.

Hiriart’s friends had tossed, as is customary, for the word of

command, and won it. In a close contest like this one —

for both were

excellent shots and men of recognized nerve —

this was considered a

great advantage.

The word was given: “Fire! one, two, three!”

Hiriart fired between the command and “one”; Locquet at the

word “one,” but it was not a second’s difference.

Locquet turned completely around, leaped in the air, and fell flat

on his face, without a word or cry.

Hiriart made a half pivot, exclaimed “I am done for,” and fell on

his hands apparently lifeless.

The mutual friends and surgeons rushed to their principals. Locquet was dead. The ball had penetrated the brain.

Hiriart’s life had been saved, it appears, by his quick firing, which

did not allow his adversary time enough to raise his weapon to a

sufficient elevation, for his shot was dead in line.

The ball had ploughed the

ground within about fifteen feet of Hiriart, then glanced up and struck

him in the stomach. A welt of the size of a duck’s egg was disclosed

on his body, black and protruding, while the skin was but slightly

abrased; the ball was found in the lining of his coat. He recovered

after a few days’ seclusion.

Several memorable duels with shotguns are chronicled with letters

of blood, among which are the unfortunate affair in which John de

Buys killed young Castaing; the one in which Alpuente, fighting also

with De Buys, was saved from death by a twenty-dollar gold piece

which he had forgotten in his vest pocket, and which arrested the

too true course of the ball; the duel in which Nora killed Dauphin;

the affair between Arthur Guillotte and Piseros, in which the latter

had a lung perforated and was disabled; the fatal meeting between

George White and Packenham Le Blanc, in which Le Blanc was killed

outright; the meeting in which General Sewell killed Thomas Cane,

and other fatal affairs.

A duel which, at the time, created quite a sensation, was the affair

between John de Buys and Aristide Gérard, in which the former

received fourteen wounds at Gérard’s hands. They fought with

colichemardes. De Buys, though the best, of fellows, was fearfully

quick-tempered and had fought some twenty-four duels, with more or

less success, three or four of which with

his mortal foe, Octave Le Blanc.

The quarrel with Gérard

happened at Belanger’s Billiard Hall, at the

corner of Orleans and Royal Streets.

A fatal duel with colichemardes was that in which Amaron Ledoux

killed a Frenchman named De Chêvremont.

It would be possible to go on thus indefinitely, but, for the purposes

of this writing, the cases cited are more than sufficient.

Whatever modernists may say, with great reason, against

the duello, for it led to many deplorable abuses, there was

more in the institution than the mere agreement to fight, and

there was more in it also than in the old relic of barbarism,

the “trial by combat.” It was in many instances an

impediment to bloodshed. Friends quarreled in momentary excitement,

and instead of seeking personal explanation, which, in

high-strung people, is impossible under provocation,

intrusted mutual friends with the demand of satisfaction. If the

seconds were wise, calm explanation would follow, and the

trifle was adjusted. The duties of the seconds were of

paramount importance, for they assumed every responsibility, and

were answerable for the life or honor of the principals at the

bar of public opinion.

The duello, however, had a refining influence, for every

gentleman was forced to be guarded in his language and

behavior, as he well knew that bare brutal courage was not

sufficient to carry him triumphantly through. It is true that a

gentleman was obliged to fight, but he had to fight well —

that is, for reason, and under plausible and legitimate conditions,

stanch enough to hold the current of public opinion.

Otherwise he was quickly ostracised, and society sustained all

who refused to cross swords or exchange shots with him.

The code was very strict. You could not fight a man whom

you could not ask to your house.

This is not an apology of the duello, which is now out of

fashion and has even become absurd, if it were only be reason of

the almost total indifference of public opinion in its regard.

It does not matter

nowadays if a man fights or not.

We have other ways of proving ourselves gentlemen.

The purpose here is only to

recall a brilliant, though not altogether faultless epoch of

Louisiana history, to show what reason our fathers had in

their madness, and to point the lessons that may be profitably

gathered by discriminating minds under the leafy shades of

the oaks.

Notes

- Collège d’Orléans.

College Orleans (1804-1818) was founded after the Louisiana Purchase to

provide local higher education so that young men would not have to go to France. The

locals boycotted and closed it when the learned the president was an atheist.

- “Ah, vous êtes mal élevé.”

“Ah, you are rude.”

- Coup droit.

Forehand.

- Present.

1887.

- Maîtres d’armes.

Fencing masters.

- Salles d’escrime.

Fencing rooms.

- Jeunesse dorée.

Gilded youth.

- Cantilena.

Chant.

- “C’est vrai,”

he said, “je pleure, mais je donne aussi des

callotes.”

“This is true,” he said, “I cry, but I also give skull-caps.”

- Old German knight. “The

Knight’s Leap” by Charles Kingsley.

- Assaut d’armes.

Assault of weapons.

- Tireur de salle.

Shooter room.

- “Qu’a cela ne tienne.”

Never mind.

-

“Quand je tiens un bon duel je ne le lache pas.” “When I want a good

duel, I do not lose.”

- “Allez, messieurs!”

“Come, gentleman!”

-

Raquette. A

game similar to lacrosse that

New Orleanians probably adopted from the Choctaw Indians.

- Coup de pointe à droite.

Sudden peak right.

-

Colichemardes.

Short swords

primarily used in the late 17th & early 18th centuries.

- Temps d’arret.

Final move.

- “Achevez moi!”

“Finish me!”

-

Chanteuse légère. Light singer.

Source

Augustin, John. “The Oaks: The Old Duelling-Grounds of

New Orleans.” The Louisiana book: selections from literature of the state. 1887. Ed. Thomas M’Caleb. New Orleans: R. F. Straughn, 1894. 71-87. Archive. Web. 5 May 2013. <http:// archive.org/ details/ louisiana books el00mcal>.

Anthology of Louisiana Literature