Milledge L. Bonham, Jr.

“The Flags of Louisiana.”

While it is common knowledge that several of our States, such as New York, Florida and Texas have had several flags, in their history, it is not so well known that Louisiana has had more different flags — nine — than any other commonwealth in the Union. Of these nine, eight were (or claimed to be) the insignia of sovereign states. Should we count all the various modifications of the various flags, for instance, that of Spain, the number would be legion rather than nine. It is the purpose of this article, however, merely to call attention to the nine flags which may be called fundamental, and to suggest their significance in the making of the Louisiana of today, as a part of the American republic.

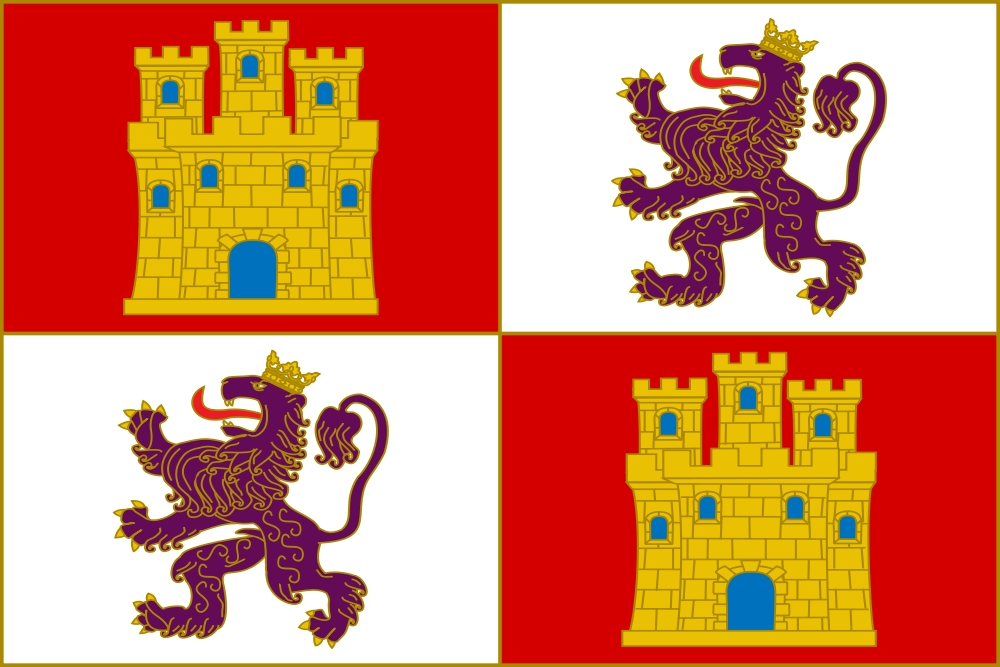

Apparently the first flag to flutter in Louisiana was that of Spain, which merely waved in passing, when in 1541, De Soto reached the Mississippi in what is now eastern Louisiana. What this flag was and what it represents will be discussed presently.

LaSalle seems to have been the godfather to christen the Mississippi valley “Louisiana” in 1679. He was perhaps the first to display the lilies of France in the present State, during his exploration of 1682. As in the case of De Soto’s flag, LaSalle’s simply waved in passing.

Pierre LeMoyne, Sieur d’Iberville and his brother, Jean, Sieur de Bienville, established the French colony of Louisiana when they settled Biloxi in 1699. On St. Patrick’s day of the same year they discovered and named Baton Rouge. In 1717, at Natchitoches (“Nacky-tosh”), Bienville made the first permanent settlement of which we are sure, in the present Louisiana. Soon Baton Rouge, New Orleans, St. Martinville and other communities began to appear. Until the cession of the French possession to England and Spain, then, the bourbon banner of France floated over Louisiana, and may be taken as the first of our series of nine. It was a white silken banner, in the center of which were three golden fleur-de-lys. This was the “oriflamme of Navarre” borne by Henri IV at Ivry, and becoming the national flag when he ascended the French throne.

What is its significance in Louisiana’s history? Its white may be taken to stand for the purity of the Ursuline nuns, the first (1727) educators in Louisiana, and its gold is indicative of the treasures of field, forest and stream, Lilies of every variety — human as well as horticultural — reproduce the fleur-de-lys. Today the white symbolizes Louisiana’s patriotism and the gold her generous hospitality.

After the treaty of Paris, in 1763, at the end of the French and Indian war, the Bourbon flag withdrew from Louisiana. First it disappeared from Baton Rouge and vicinity — known today as “the Florida parishes.” The little settlement there became “Fort Richmond” in the British province of West Florida, and England’s scarlet superceded France’s white. The British standard, of course, consists of a red banner having in the upper, inner comer the “Union Jack,” which is a field of blue on which are now combined the crosses of St. George, St. Andrew and St. Partick — though in 1763 only the first two appeared. The red and white crosses on the blue field produce the same combination found in our own and so many other national emblems. From Britain, Louisiana has drawn much of her constitutional law, just as from Rome, by way of France and Spain, she drew her civil law. The crosses of the Union Jack may be taken to symbolize the religious liberty enjoyed in Louisiana today.

Though New Orleans and Louisiana west of the Mississippi had been ceded to Spain in 1763, she did not take possession of her new colony until 1766, when the Bourbon lilies gave place to the lions and castles of Spain. Just what was the Spanish flag, as carried by De Soto and as brought by Don Antonio de Ulloa in 1766? When Columbus set sail in 1492 he bore the “standard of Spain,” which was a quartering of red and grey with a red lion of Leon ramping on the grey squares and the yellow castle of Castile on the red. It is doubtful if this flag was ever displayed in Louisiana, but all its colors are there, in the grey of the Spanish moss, the red of the pomegranate — not to mention the delicious “redfish courtbouillon” of the Louisiana cooks — and the yellow jasmine. De Soto may have borne the “royal standard” which was a purple flag bearing the royal coat-of-arms in the center. Its color suggests the regal beauty of the women of Louisiana, as well as the color of the water-hyacinths and the sugar cane. More familiar is the Spanish merchant flag, of yellow with two red stripes, near the upper and lower borders. As an admiral of Spain, it is more likely that De Soto carried the naval ensign, composed of two bands of red separated by a broader stripe of yellow, in which appears the royal coat-of-arms. It was one of these red and yellow banners which became the flag of Louisiana in 1766.

In the life of the State, the red denotes courage, a virtue which had been displayed by Louisianians from the pioneer days of Bienville at Natchitoches to the days of General John A. Lejeune and the marines at Chateau-Thierry. Red also are the hibiscus flowers of Louisiana and red the inviting lips of her daughters. Golden yellow are her rice fields, golden is the harvest of her cotton and cane fields, golden are her oranges and mimosas. The yellow fever has been extirpated by her physicians and yellow journalism never flourished there. Yellow is the product of the Calcasieu sulphur mines, perhaps the greatest on earth.

Sixteen years after the British flag was planted at Baton Rouge, it was hauled down, for in 1779, Spain having become an ally of France and the United Colonies, Governor Bernardo de Galvez came up from New Orleans with a force of Spaniards, Americans, and Indians on September 21, fought the only engagement of the American Revolution on Louisiana soil, compelling Colonel Dickson to surrender Fort Richmond. Thus all Louisiana came under the Spanish flag.

Napoleon, it will be remembered, (“First Consul Bonaparte”) compelled Spain to cede Louisiana to him in 1801. At once he began negotiations with the United States. Not until the spring of 1803 did his agent Laussat appear in the colony and not until November 30 did he take formal possession. That day he ran up the tricolor of the French republic on the flag pole in the “Place d’Armes” (now Jackson square) at New Orleans. Louisiana thus acquired its fourth flag. Its colors had already appeared at Baton Rouge in the British ensign, and were to appear in three other flags. The blue of truth in the tricolor suggests the waters of Louisiana’s fair lakes and bayous; the white, the pure blossoms of her camellias and magnolias, the pure Americanism of her children; the red, the ardent Creole nature with its love of art, of home, of State, of country.

Only three weeks did this new banner float, and apparently, only at the capital city of New Orleans. Laussat lowered it on December 20, 1803. and Governor W. C. C. Claiborne replaced it with the Stars and Stripes. As the blue, white and red descended, it passed the red, white and blue ascending. Thus we have the fifth of our series, which made the third in three weeks. November 30, the Spanish flag flew at dawn; the next dawn saw the French flag in its place, sunset of December 20 gilded “Old Glory.”

The United States flag, of course, has a history of its own, and at that time had more stripes (17) and fewer stars (17) than at present. But since it is most familiar in its present form, we shall accept it simply as the emblem of the United States and disregard the details of its evolution.

What did this emblem mean? The blue field was the same blue of truth shown in the Union Jack and the tricolor; but since it was in the flag of a young nation, evidently it typified the hope that humanity was basing on this experiement in democracy. That this hope has not been disappointed, Albert of Belgium and George of England join Poincare of France today in assuring Woodrow Wilson. These stars mean what? A constellation of States certainly, and just as each State is a jewel in the crown of Columbia, so do the starry jewels of domestic virtue, of hospitality, of industry, courage, sobriety, patriotism, art, education and generosity adorn the brow of Louisiana. Not only the purity of America’s purpose and the ardor of her patriotism are denoted, by these stripes but they are also the ladder of worthy deeds, whereby Louisianians as citizens of both State and Nation climb toward the goal of progress. Indubitably, Louisiana’s most flourishing epochs have been those when she has been without question beneath the aegis of Columbia, namely, from 1803 to 1861 and since 1865.

.svg.png)

While Governor Claiborne and his associates were busy organizing the government of the territory of Orleans, at Baton Rouge the scarlet and saffron of Spain still waved, and Spanish officials pursued the even tenor of their way. Don Carlos de Grandpre was the Governor, but in 1808 he was succeeded by Don Carlos de Hault de Lassus and Don Louis de Grandpre became conmiandant of the little fort at Baton Rouge. This stood on the same site previously occupied by Fort Richmond, and before that the French fort. On and about it, between 1820 and 1830 were erected the buildings of the United States arsenal and garrison, now part of the equipment of Louisiana State University. Once again the influence of Napoleon — now emperor of the French — affected the history of Louisiana. In 1808 he placed his brother, Joseph, on the throne of Spain. Soon in the Spanish colonies “juntas,” or committees of the colonists, loyal to the house of Bourbon, undertook to carry on the colonial government until the restoration of Ferdinand VII. Such a committee was organized at the “Tlains,” a few miles north of Baton Rouge, in July, 1810. In September, however, the Anglo-Americans in the province of West Florida held a convention and took the step that from 1814 to 1825 the other Spanish colonies were to take. “General” Philemon Thomas — a veteran of the American Revolution — was sent with an “army” of one hundred to capture the garrison at Baton Rouge. This was done, the gallant Grandpre being mysteriously slain, and the governor captured.

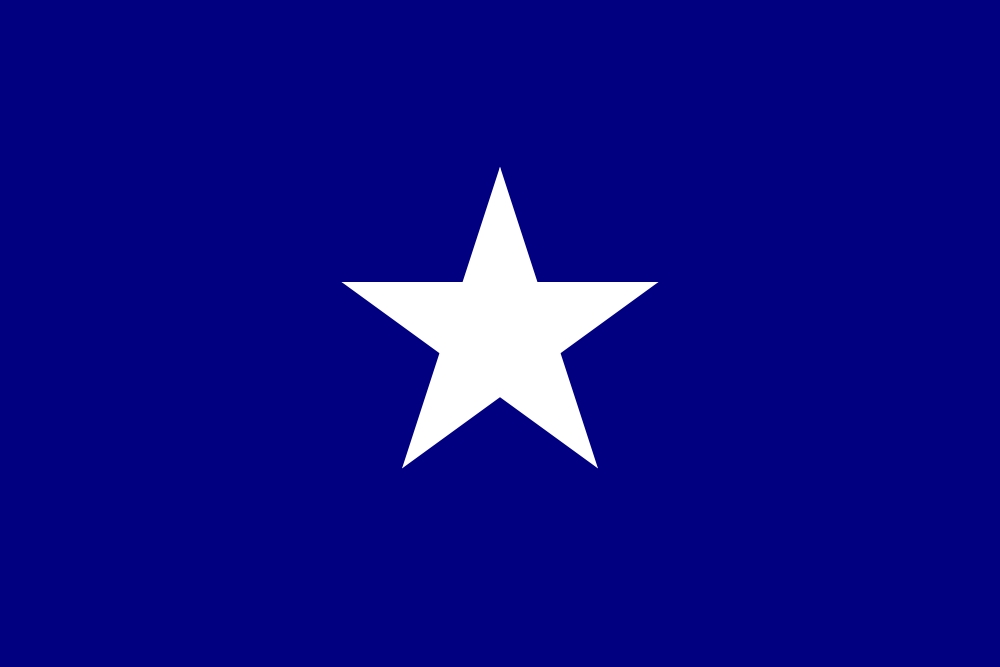

This date, September 23, 1810, marked the appearance of the “Republic of West Florida,” whose ensign, the sixth in our series, was the first “lone star” flag in American history, being a blue woollen field with a single silver star in the centre. Fulwar Skipwith was soon elected governor of the republic, which applied for annexation to the United States as a new commonwealth. President Madison believed that this region had been included in the Louisiana purchase, so directed Governor Claiborne to administer it as part of the territory of Orleans, which he began doing in December, 1810. Two years later, that portion of the old West Florida province (and “republic") between the lakes, the Mississippi and Pearl rivers, and the present State of Mississippi, entered the Union as part of the State of Louisiana; whence the name “Florida parishes.” In the language of a distinguished descendant of some of the West Florida revolutionists, “the Stars and Stripes replaced the argent star on the blue field; the government of the free State peacefully dissolved; its troops disbanded and its citizens enrolled themselves among the truest and staunchest of the Great Republic.”

Blue, deep blue, like the skies of Louisiana, was this sixth banner, and silver as the clear notes of her mocking birds was the star. Note how often this true blue thread appears in her history, and the silver or grey or white, whether of purbity, or of magnolia bloom, or of the fogs of the Father of Waters, recurs again and again.

Louisianians followed the flag of the Union in the War of 1812, the Seminole and Mexican wars, displaying the virtues symbolized by these six banners. Perhaps this was why the seventh and the eighth, like the sixth, were to be the bomb of war, and like it, destined to be short lived.

Once again, as in 1810, Baton Rouge was the scene of a declaration of independence. The convention of Louisiana, on January 26, 1861, adopted the ordinance of secession, and Louisiana was proclaimed a free and independent State. A committee was ordered to design a national flag for her, which was adopted early in February, and until Louisiana entered the Confederacy in March, was the emblem of her “sovereignty.” The committee declared that they were trying, in this “national flag of the State of Louisiana” to epitomize all her previous flags. Let us see if they succeeded. The design was a standard of thirteen stripes of blue (4), white (6), and red (3), in that order, with a field of red in the upper, inner corner, containing a single star of pale yellow. It will be seen at a glance that this flag contains the white and gold of the Bourbon oriflamme, while the lone yellow star in the red field suggests both the colors of Spain and the single star of West Florida. Stripes of blue, white and red remind us of the banners of Britain and the French republic, while the mystic number thirteen was borrowed from Old Glory.

It will soon appear that the committee was prophetic as well as historic in its instincts, since the flag also contains the colors of the State’s other two flags. Probably the complicated nature of this flag symbolizes the racial elements in Louisiana’s population. Among the whites we find first the Creoles — pure whites of French or Spanish descent, then Anglo-Americans, people of German, Dutch, Portuguese, Italian, Greek, Scandinavian, Russian, Armenian and Balkan extraction, with many intermarriages among these various dements. There are a few Hindus, some Indians, many Mongolians and large numbers of heroes.

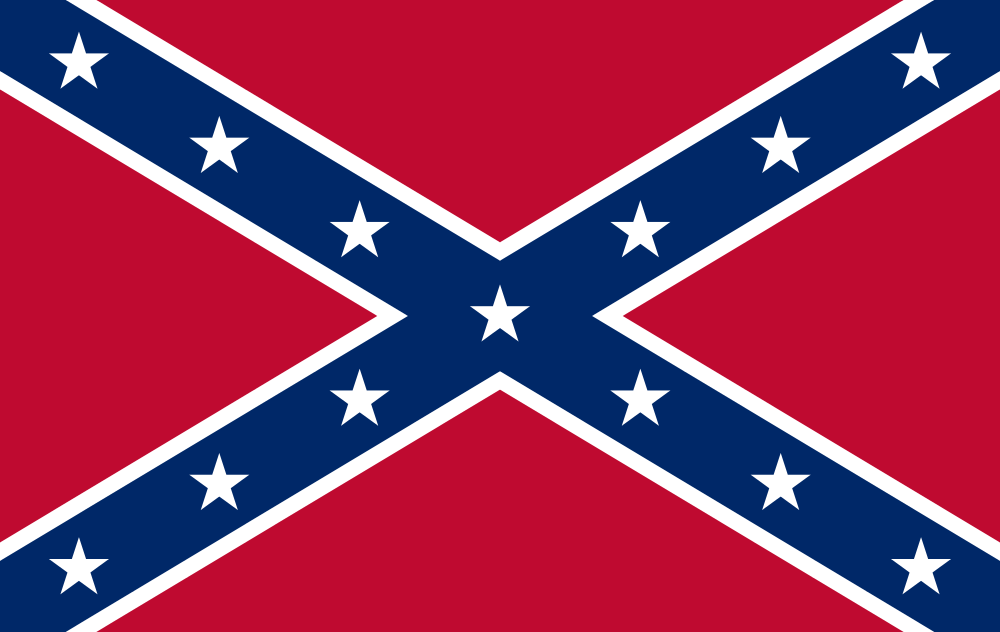

Soon the eighth flag appeared, relating the seventh to the rank of a State flag. Of course the eighth was the banner of the Confederacy. Like some others, it had several forms, but the best known and most popular was the crimson field with a blue St. Andrew’s cross, bordered with white and bearing thirteen white stars. These colors have already been interpreted sufficiently, but the cross suggests the religious fervor with which Louisiana threw herself into the struggle for Southern independence. It symbolizes also the heavy cross she bore during Reconstruction.

|

|

Battle Flag — Army of Tennessee

Public domain photo by Wikipedia

|

Early in 1862, it was superceded by the Stars and Stripes in the southern part of the State, and this gradually penetrated north and westward until in 1865 it waved everyone. Today there is not a Louisianian who does not pray that the Stars and Stripes will continue to float over the State as long as mankind endures.

.svg.png)

|

|

First National Confederate Flag — 7 Stars

(March 4, 1861 - May 21, 1861) Public domain photo by Wikipedia

|

These eight flags were the emblems of limits claiming independent sovereignty. Our ninth is that of a sub-division of a nation — the well-known “Pelican flag” of the State of Louisiana. While it seems that various flags hearing pelicans — sometimes red flags, sometimes blue — had been used at deferent times by military companies and other organizations, and the pelican design was suggested to the convention of 1861, it was not until after Reconstruction that the present, blue pelican flag came into general use, and not until July 1, 1912 did the legislature officially and formally declare it the State flag. General John McGrath, ex-president of the Historical Society of East and West Baton Rouge, is inclined to think, that since no convention ever rescinded the adoption of the “synoptical” Flag of 1861, it is still the official State flag, while the Pelican flag is merely the governor’s headquarters standard.

The symbolism of the Pelican flag is, of course, very clear. The blue field signifies both truth and hope, and Louisiana is true to American ideals and optimistic as to her future. The motto : Union, Justice, Confidence, speaks for itself. The design of the Pelican feeding the young in the nest is based on the legend that in time of famine this mother plucked the flesh from her breast to nourish her fledglings. Equally devoted is Louisiana to her children and so from her bosom — her fertile fields — does she draw their sustenance.

We have seen that at one time or another, over all or part of the present State of Louisiana, at least nine flags have floated. Having glanced in a figurative manner at their symbolism, let us try for a moment to see what actual contributions to the State’s development these banners suggest. Beginning with France, we derive the name, the Creole and Acadian elements in the population, the French elements the language, the civil law, the literature, the menu and the art of Louisiana, with the gracious personal traits of the Gaul, and the large Catholic element in her population. Such place-names as Orleans. Terrebonne, Lafayette, Thibodaux, Iberville, Pontchartrain, are redolent of “la Belle France.” Martin and Moreau-Lislet in law, Etienne de Boré in sugar manufacturing, Madeleine Hachard and Pere Allouez in religion, Moweau Gottschalk in music, Alcée Fortier in literature, Chaillé in medicine, Audubon in science, Jean Louis in philanthropy, Mouton and Hebert in politics, Blanchard, Beauregard, LeJeune, in war, Julien Poydras in agriculture and philanthropy, are enough to illustrate the rich and varied contributions of France to the making of Louisiana. Matas in surgery, Unzaga and Miro in government, Galvez and Desoto on the map, Gayarré in history, Penalvert y Cardenas in religion, Almonaster in philanthropy, Bermudez in law, Quintero in journalism, are typical of the Spanish element in her history. From the United States Louis iana derived such jurists as Edward Livingston and E. D. White, such authors as Grace King and George W. Cable, such educators as James W. Nicholson, the mathematician, David F. Boyd, sometime president of Louisiana State University, A. B. Dinwiddie, president of Tulane; such clergymen as B. M. Palmer and Max Heller, and the Protestant religion, such soldiers as “Dick” Taylor and Franklyn Gardner, such diplomatists as J. B. Eustis, the first American ambassador to France; such philanthropists as John McDonogh and Judah Touro. The English language is part of Louisiana’s heritage from Britain, while Judah P. Benjamin, “the brains of the Confederacy,” was born under the British flag, as were Mr. William Beer of the Howard Memorial Library, and Professor W. H. Dalrymple, the noted scientist. Many of the West Florida revolutionists were English loyalists who had fled to that province during the Revolution, but who preferred American rule to Spanish. With the “lone star” flag we associate Philemon Thomas, of course, who later entered the State legislature, and commanded the Baton Rouge militia at the battle of New Orleans. John Rhea, Fulwar Skipwith and other members of this revolutionary party were the ancestors of many prominent Louisianians of today. Two of the first city councilmen (1818) of Baton Rouge were veterans of this revolution — William Williams and Hugh Crawford.

With the Confederate flag we naturally associate Generals P. G. T, Beauregard, “Dick” Taylor, Braxton Bragg; Duncan F. Kenner, president of the convention of 1861, and a member of the Confederate Congress; Governors T. O. Moore and Henry Watkins Allen, Judah P. Benjamin and P. A. Rost. While many noted Louisianians first attained prominence during the era of the Confed eracy, their greatest services were rendered in the epoch of the Pelican flag, especially during Reconstruction. Amongst them were Governor and Senator S. D. McEnery, Governors F. T. Nicholls and L. A. Wiltz, E. D. White, Chief Justice of the United States, the author Ruth McEnery Stuart, and educators like Boyd and Nichol son. Belonging entirely to the Pelican flag period are State Superin tendent Thomas H. Harris, Governor Ruffin G. Pleasant, Dr. Oscar Dowhng, the wonder working president of the State Board of Health, Miss Sophie B. Wright, Mrs. John Dibert, John M. Parker, Dr. Rudolpdi Matas, Bishop Davis Sessums, and many distinguished soldiers, sailors and marines in the World War, of whom a few of the more prominent are General John A. Lejeune, Colonels F. P. Stubbs, C. B. Hodges, Sanderford Jarman, Ogden Fuqua and Major O. W. McNeese.

Flags are, of themselves, nothing: as emblems they are significant. It is hoped that this brief essay has shown that each of Louisiana’s nine flags is emblematic of positive and valuable contributions to American civilization. Louisiana is proud of every one of her flags. But she wishes for no more, and so far as her efforts can secure that end, the Stars and Stripes and the Pelican will wave side by side from her capitol until time shall be no more.

Text prepared by

- Chase Alspaugh

- Brandon Crear

- Shakeidra Evans

- Mark Lowe

- Michael Perkins

- Korbin Sims

Notes

- Great Republic. Favrot, Henry L., “The West Florida Revolution.” in Pubs., La. His. Soc., I, Pts.. i, ii.

Source

Bonham, Milledge L., Jr. “The Flags of Louisiana.” The Louisiana Historical Quarterly 2.1 (1919): 439-46. Archive.org. Web. 31 October 2012. <http://archive.org/ stream/ louisiana histor00 unkngoog#page/ n452/ mode/2up>.