Sidonie de la Houssaye.

George Washington Cable, Ed.

“Alix de Morainville.”

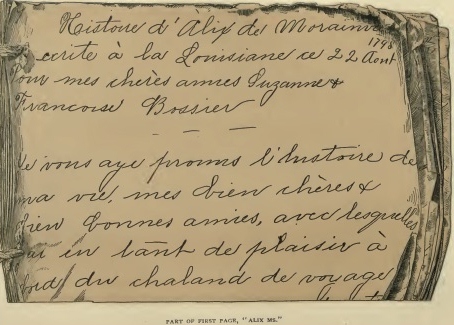

part of first page, “alix ms.”

part of first page, “alix ms.”

1773-95.

Written in Louisiana this 22d of August, 1795, for my dear friends Suzanne and Françoise Bossier.

I have promised you the story of my life, my very dear and good friends with whom I have had so much pleasure on board the flatboat which has brought us all to Attakapas. I now make good my promise.

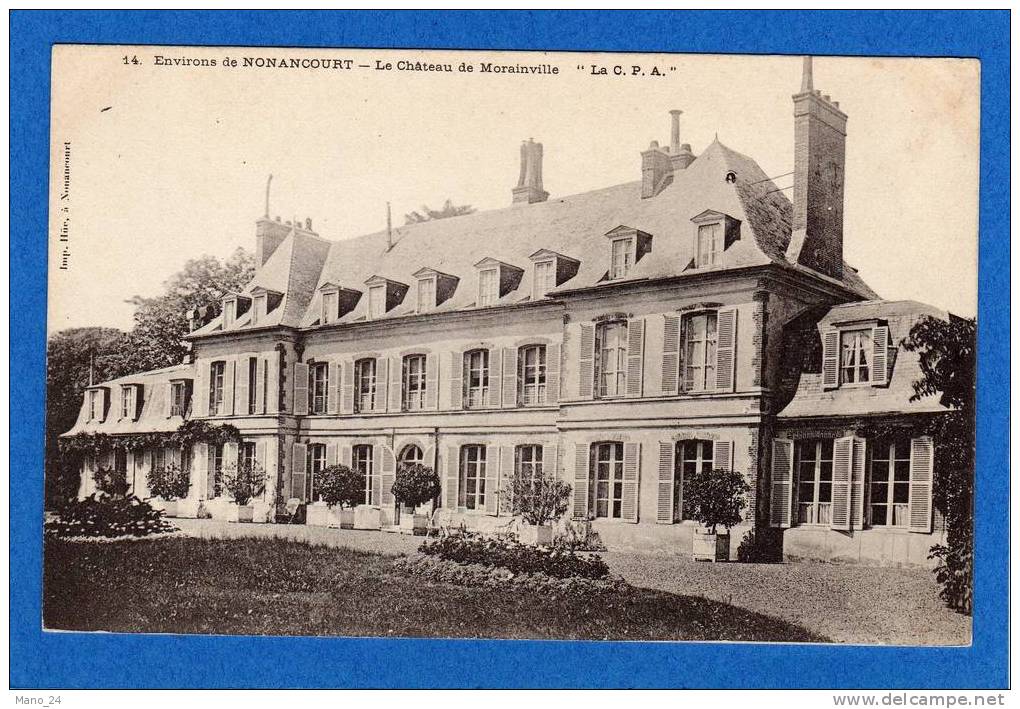

And first I must speak of the place where I was born, of the beautiful Château de Morainville, built above the little village named Morainville in honor of its lords. This village, situated in Normandy on the margin of the sea, was peopled only and entirely by fishermen, who gained a livelihood openly by sardine-fishing, and secretly, it was said, by smuggling. The château was built on a cliff, which it completely occupied. This cliff was formed of several terraces that rose in a stair one above another. On the topmost one sat the château, like an eagle in its nest. It had four dentilated turrets, with great casements and immense galleries, that gave it the grandest possible aspect. On the second terrace you found yourself in the midst of delightful gardens adorned with statues and fountains after the fashion of the times. Then came the avenue, entirely overshaded with trees as old as Noah, and everywhere on the hill, forming the background of the picture, an immense park. How my Suzanne would have loved to hunt in that beautiful park full of deer, hare, and all sorts of feathered game!

|

|

Chateau de Morainville.

Public domain photo at

Delcampe.fr.

|

And yet no one inhabited that beautiful domain. Its lord and mistress, the Count Gaston and Countess Aurélie, my father and mother, resided in Paris, and came to their château only during the hunting season, their sojourn never exceeding six weeks.

Already they had been five years married. The countess, a lady of honor to the young dauphine, Marie Antoinette, bore the well-merited reputation of being the most charming woman at the court of the king, Louis the Fifteenth. Count and countess, wealthy as they were and happy as they seemed to be, were not overmuch so, because of their desire for a son; for one thing, which is not seen in this country, you will not doubt, dear girls, exists in France and other countries of Europe: it is the eldest son, and never the daughter, who inherits the fortune and titles of the family. And in case there were no children, the titles and fortune of the Morainvilles would have to revert in one lump to the nephew of the count and son of his brother, to Abner de Morainville, who at that time was a mere babe of four years. This did not meet the wishes of M. and Mme. de Morainville, who wished to retain their property in their own house.

|

|

Marie Antoinette.

Public domain photo at

Wikipedia.

|

But great news comes to Morainville: the countess is with child. The steward of the château receives orders to celebrate the event with great rejoicings. In the avenue long tables are set covered with all sorts of inviting meats, the fiddlers are called, and the peasants dance, eat, and drink to the health of the future heir of the Morainvilles. A few months later my parents arrived bringing a great company with them; and there were feasts and balls and hunting-parties without end.

It was in the course of one of these hunts that my mother was thrown from her horse. She was hardly in her seventh month when I came into the world. She escaped death, but I was born as large as — a mouse! and with one shoulder much higher than the other.

I must have died had not the happy thought come to the woman-in-waiting to procure Catharine, the wife of the gardener, Guillaume Carpentier, to be my nurse; and it is to her care, to her rubbings, and above all to her good milk, that I owe the capability to amuse you, my dear girls and friends, with the account of my life — that life whose continuance I truly owe to my mother Catharine.

When my actual mother had recovered she returned to Paris; and as my nurse, who had four boys, could not follow her, it was decided that I should remain at the château and that my mother Catharine should stay there with me.

Her cottage was situated among the gardens. Her husband, father Guillaume, was the head gardener, and his four sons were Joseph, aged six years; next Matthieu, who was four; then Jerome, two; and my foster-brother Bastien, a big lubber of three months.

My father and mother did not at all forget me. They sent me playthings of all sorts, sweetmeats, silken frocks adorned with embroideries and laces, and all sorts of presents for mother Catharine and her children. I was happy, very happy, for I was worshiped by all who surrounded me. Mother Catharine preferred me above her own children. Father Guillaume would go down upon his knees before me to get a smile (risette), and Joseph often tells me he swooned when they let him hold me in his arms. It was a happy time, I assure you; yes, very happy.

I was two years old when my parents returned, and as they had brought a great company with them the true mother instructed my nurse to take me back to her cottage and keep me there, that I might not be disturbed by noise. Mother Catharine has often said to me that my mother could not bear to look at my crippled shoulder, and that she called me a hunchback. But after all it was the truth, and my nurse-mother was wrong to lay that reproach upon my mother Aurélie.

Seven years passed. I had lived during that time the life of my foster-brothers, flitting everywhere with them over the flowery grass like the veritable lark that I was. Two or three times during that period my parents came to see me, but without company, quite alone. They brought me a lot of beautiful things; but really I was afraid of them, particularly of my mother, who was so beautiful and wore a grand air full of dignity and self-regard. She would kiss me, but in a way very different from mother Catharine’s way — squarely on the forehead, a kiss that seemed made of ice.

One fine day she arrived at the cottage with a tall, slender lady who wore blue spectacles on a singularly long nose. She frightened me, especially when my mother told me that this was my governess, and that I must return to the château with her and live there to learn a host of fine things of which even the names were to me unknown; for I had never seen a book except my picture books.

I uttered piercing cries; but my mother, without paying any attention to my screams, lifted me cleverly, planted two spanks behind, and passed me to the hands of Mme. Levicq — that was the name of my governess. The next day my mother left me and I repeated my disturbance, crying, stamping my feet, and calling to mother Catharine and Bastien. (To tell the truth, Jerome and Matthieu were two big lubbers (rougeots) very peevish and coarse-mannered, which I could not endure.) Madame put a book into my hands and wished to have me repeat after her; I threw the book at her head. Then, rightly enough, in despair she placed me where I could see the cottage in the midst of the garden and told me that when the lesson was ended I might go and see my mother Catharine and play with my brothers. I promptly consented, and that is how I learned to read.

This Mme. Levicq was most certainly a woman of good sense. She had a kind heart and much ability. She taught me nearly all I know — first of all, French; the harp, the guitar, drawing, embroidery; in short, I say again, all that I know.

I was fourteen years old when my mother came, and this time not alone. My cousin Abner was with her. My mother had me called into her chamber, closely examined my shoulder, loosed my hair, looked at my teeth, made me read, sing, play the harp, and when all this was ended smiled and said:

“You are beautiful, my daughter; you have profited by the training of your governess; the defect of your shoulder has not increased. I am satisfied — well satisfied; and I am going to tell you that I have brought the Viscomte Abner de Morainville because I have chosen him for your future husband. Go, join him in the avenue.”

I was a little dismayed at first, but when I had seen my intended my dismay took flight — he was such a handsome fellow, dressed with so much taste, and wore his sword with so much grace and spirit. At the end of two days he loved me to distraction and I doted on him. I brought him to my nurse’s cabin and told her all our plans of marriage and all my happiness, not observing the despair of poor Joseph, who had always worshiped me and who had not doubted he would have me to love. But who would have thought it — a laboring gardener lover of his lord’s daughter? Ah, I would have laughed heartily then if I had known it!

On the evening before my departure — I had to leave with my mother this time — I went to say adieu to mother Catharine. She asked me if I loved Abner.

“Oh, yes, mother!” I replied, “I love him with all my soul”; and she said she was happy to hear it. Then I directed Joseph to go and request Monsieur the curé, in my name, to give him lessons in reading and writing, in order to be able to read the letters that I should write to my nurse-mother and to answer them. This order was carried out to the letter, and six months later Joseph was the correspondent of the family and read to them my letters. That was his whole happiness.

I had been quite content to leave for Paris: first, because Abner went with me, and then because I hoped to see a little of all those beautiful things of which he had spoken to me with so much charm; but how was I disappointed! My mother kept me but one day at her house, and did not even allow Abner to come to see me. During that day I must, she said, collect my thoughts preparatory to entering the convent. For it was actually to the convent of the Ursulines, of which my father’s sister was the superior, that she conducted me next day.

Think of it, dear girls! I was fourteen, but not bigger than a lass of ten, used to the open air and to the caresses of mother Catharine and my brothers. It seemed to me as if I were a poor little bird shut in a great dark cage.

My aunt, the abbess, Agnes de Morainville, took me to her room, gave me bonbons and pictures, told me stories, and kissed and caressed me, but her black gown and her bonnet appalled me, and I cried with all my might:

“I want mother Catharine! I want Joseph! I want Bastien!”

My aunt, in despair, sent for three or four little pupils to amuse me; but this was labor lost, and I continued to utter the same outcries. At last, utterly spent, I fell asleep, and my aunt bore me to my little room and put me to bed, and then slowly withdrew, leaving the door ajar.

On the second floor of the convent there were large dormitories, where some hundreds of children slept; but on the first there were a number of small chambers, the sole furniture of each being a folding bed, a washstand, and a chair, and you had to pay its weight in gold for the privilege of occupying one of these cells, in order not to be mixed with the daughters of the bourgeoisie, of lawyers and merchants. My mother, who was very proud, had exacted absolutely that they give me one of these select cells.

Hardly had my aunt left me when I awoke, and fear joined itself to grief. Fancy it! I had never lain down in a room alone, and here I awoke in a corner of a room half lighted by a lamp hung from the ceiling. You can guess I began again my writhings and cries. Thereupon appeared before me in the open door the most beautiful creature imaginable. I took her for a fairy, and fell to gazing at her with my eyes full of amazement and admiration. You have seen Madelaine, and you can judge of her beauty in her early youth. It was a fabulous beauty joined to a manner fair, regal, and good.

She took me in her arms, dried my tears, and at last, at the extremity of her resources, carried me to her bed; and when I awoke the next day I found myself still in the arms of Madelaine de Livilier. From that moment began between us that great and good friendship which was everything for me during the time that I passed in the convent. I should have died of loneliness and grief without Madelaine. I had neither brothers nor sisters; she was both these to me: she was older than I, and protected me while she loved me.

She was the niece of the rich Cardinal de Ségur, who had sent and brought her from Louisiana. This is why Madelaine had such large privileges at the convent. She told me she was engaged to the young Count Louis le Pelletrier de la Houssaye, and I, with some change of color, told her of Abner.

One day Madelaine’s aunt, the Countess de Ségur, came to take her to spend the day at her palace. My dear friend besought her aunt with such graciousness that she obtained permission to take me with her, and for the first time I saw the Count Louis, Madelaine’s fiancé. He was a very handsome young man, of majestic and distinguished air. He had hair and eyes as black as ink, red lips, and a fine mustache. He wore in his buttonhole the cross of the royal order of St. Louis, and on his shoulders the epaulettes of a major. He had lately come from San Domingo [where he had been fighting the insurgents at the head of his regiment]. Yes, he was a handsome young man, a bold cavalier; and Madelaine idolized him. After that day I often accompanied my friend in her visits to the home of her aunt. Count Louis was always there to wait upon his betrothed, and Abner, apprised by him, came to join us. Ah! that was a happy time, very happy.

At the end of a year my dear Madelaine quitted the convent to be married. Ah, how I wept to see her go! I loved her so! I had neither brothers nor sisters, and Madelaine was my heart’s own sister. I was very young, scarcely fifteen; yet, despite my extreme youth, Madelaine desired me to be her bridesmaid, and her aunt, the Countess de Ségur, and the Baroness de Chevigné, Count Louis’s aunt, went together to find my mother and ask her to permit me to fill that office. My mother made many objections, saying that I was too young; but — between you and me — she could refuse nothing to ladies of such high station. She consented, therefore, and proceeded at once to order my costume at the dressmaker’s.

It was a mass of white silk and lace with intermingled pearls. For the occasion my mother lent me her pearls, which were of great magnificence. But, finest of all, the Queen, Marie Antoinette, saw me at the church of Notre Dame, whither all the court had gathered for the occasion, — for Count Louis de la Houssaye was a great favorite, — and now the queen sent one of her lords to apprise my mother that she wished to see me, and commanded that I be presented at court — grande rumeur!

|

|

The Cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris, 1841.

Public domain photo at

Wikipedia.

|

Mamma consented to let me remain the whole week out of the convent. Every day there was a grand dinner or breakfast and every evening a dance or a grand ball. Always it was Abner who accompanied me. I wrote of all my pleasures to my mother Catharine. Joseph read my letters to her, and, as he told me in later days, they gave him mortal pain. For the presentation my mother ordered a suit all of gold and velvet. Madelaine and I were presented the same day. The Countess de Ségur was my escort [marraine] and took me by the hand, while Mme. de Chevigné rendered the same office to Madelaine. Abner told me that day I was as pretty as an angel. If I was so to him, it was because he loved me. I knew, myself, I was too small, too pale, and ever so different from Madelaine. It was she you should have seen.

|

|

The Palace of Versailles.

Public domain photo at

Wikipedia.

|

|

|

The Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.

Public domain photo at

Wikipedia.

|

I went back to the convent, and during the year that I passed there I was lonely enough to have died. It was decided that I should be married immediately on leaving the convent, and my mother ordered for me the most beautiful wedding outfit imaginable. My father bought me jewels of every sort, and Abner did not spare of beautiful presents.

I had been about fifteen days out of the convent when terrible news caused me many tears. My dear Madelaine was about to leave me forever and return to America. The reason was this: there was much disorder in the colony of Louisiana, and the king deciding to send thither a man capable of restoring order, his choice fell upon Count Louis de la Houssaye, whose noble character he had recognized. Count Louis would have refused, for he had a great liking for France; but [he had lately witnessed the atrocities committed by the negroes of San Domingo], and presentiment — warned him that the Revolution was near at hand. He was glad to bear his dear wife far from the scenes of horror that were approaching with rapid strides.

Madelaine undoubtedly experienced pleasure in thinking that she was again going to see her parents and her native land, but she regretted to leave France, where she had found so much amusement and where I must remain behind her without hope of our ever seeing each other again. She wept, oh, so much!

She had bidden me good-bye and we had wept long, and her last evening, the eve of the day when she was to take the diligence for Havre, where the vessel awaited them, was to be passed in family group at the residence of the Baroness de Chevigné. Here were present, first the young couple; the Cardinal, the Count and Countess de Ségur; then Barthelemy de la Houssaye, brother of the Count, and the old Count de [Maurepas, only a few months returned from exile and now at the pinnacle of royal favor]. He had said when he came that he could stay but a few hours and had ordered his coach to await him below. He was the most lovable old man in the world. All at once Madelaine said:

“Ah! if I could see Alix once more — only once more!”

The old count without a word slipped away, entered his carriage, and had himself driven to the Morainville hotel, where there was that evening a grand ball. Tarrying in the ante-chamber, he had my mother called. She came with alacrity, and when she knew the object of the count’s visit she sent me to get a great white burnoose, enveloped me in it, and putting my hand into the count’s said to me:

“You have but to show yourself to secure the carriage.” But the count promised to bring me back himself.

Oh, how glad my dear Madelaine was to see me! With what joy she kissed me! But she has recounted this little scene to you, as you, Françoise, have told me.

A month after the departure of the De la Houssayes, my wedding was celebrated at Notre Dame. It was a grand occasion. The king was present with all the court. As my husband was in the king’s service, the queen wished me to become one of her ladies of honor.

Directly after my marriage I had Bastien come to me. I made him my confidential servant. He rode behind my carriage, waited upon me at table, and, in short, was my man of all work.

I was married the 16th of March, 1789, at the age of sixteen. Already the rumbling murmurs of the Revolution were making themselves heard like distant thunder. [On the 13th of July the Bastille was taken and the head of the governor De Launay was carried through the streets.] My mother was frightened and proposed to leave the country. She came to find me and implored me to go with her to England, and asked Abner to accompany us. My husband refused with indignation, declaring that his place was near his king.

“And mine near my husband,” said I, throwing my arms around Abner’s neck.

My father, like my husband, had refused positively to leave the king, and it was decided that mamma should go alone. She began by visiting the shops, and bought stuffs, ribbons, and laces. It was I who helped her pack her trunks, which she sent in advance to Morainville. She did not dare go to get her diamonds, which were locked up in the Bank of France; that would excite suspicion, and she had to content herself with such jewelry as she had at her residence. She left in a coach with my father, saying as she embraced me that her absence would be brief, for it would be easy enough to crush the vile mob. She went down to Morainville, and there, thanks to the devotion of Guillaume Carpentier and of his sons, she was carried to England in a contrabandist vessel. As she was accustomed to luxury, she put into her trunks the plate of the château and also several valuable pictures. My father had given her sixty thousand francs and charged her to be economical.

Soon I found myself in the midst of terrible scenes that I have not the courage, my dear girls, to recount. The memory of them makes me even to-day tremble and turn pale. I will only tell you that one evening a furious populace entered our palace. I saw my husband dragged far from me by those wretches, and just as two of the monsters were about to seize me Bastien took me into his arms, and holding me tightly against his bosom leaped from a window and took to flight with all his speed.

Happy for us that it was night and that the monsters were busy pillaging the house. They did not pursue us at all, and my faithful Bastien took me to the home of his cousin Claudine Leroy. She was a worker in lace, whom, with my consent, he was to have married within the next fortnight. I had lost consciousness, but Claudine and Bastien cared for me so well that they brought me back to life, and I came to myself to learn that my father and my husband had been arrested and conveyed to the Conciergerie.

My despair was great, as you may well think. Claudine arranged a bed for me in a closet [cloisette] adjoining her chamber, and there I remained hidden, dying of fear and grief, as you may well suppose.

At the end of four days I heard some one come into Claudine’s room, and then a deep male voice. My heart ceased to beat and I was about to faint away, when I recognized the voice of my faithful Joseph. I opened the door and threw myself upon his breast, crying over and over:

“O Joseph! dear Joseph!”

He pressed me to his bosom, giving me every sort of endearing name, and at length revealed to me the plan he had formed, to take me at once to Morainville under the name of Claudine Leroy. He went out with Claudine to obtain a passport. Thanks to God and good angels Claudine was small like me, had black hair and eyes like mine, and there was no trouble in arranging the passport. We took the diligence, and as I was clothed in peasant dress, a suit of Claudine’s, I easily passed for her.

Joseph had the diligence stop beside the park gate, of which he had brought the key. He wished to avoid the village. We entered therefore by the park, and soon I was installed in the cottage of my adopted parents, and Joseph and his brothers said to every one that Claudine Leroy, appalled by the horrors being committed in Paris, had come for refuge to Morainville.

Then Joseph went back to Paris to try to save my father and my husband. Bastien had already got himself engaged as an assistant in the prison. But alas! all their efforts could effect nothing, and the only consolation that Joseph brought back to Morainville was that he had seen its lords on the fatal cart and had received my father’s last smile. These frightful tidings failed to kill me; I lay a month between life and death, and Joseph, not to expose me to the recognition of the Morainville physician, went and brought one from Rouen. The good care of mother Catharine was the best medicine for me, and I was cured to weep over my fate and my cruel losses.

It was at this juncture that for the first time I suspected that Joseph loved me. His eyes followed me with a most touching expression; he paled and blushed when I spoke to him, and I divined the love which the poor fellow could not conceal. It gave me pain to see how he loved me, and increased my wish to join my mother in England. I knew she had need of me, and I had need of her.

Meanwhile a letter came to the address of father Guillaume. It

was a

contrabandist vessel that brought

(Torn off and gone.)

it and

of the first evening

other to the address

recognized the writing

set me to sobbing

all, my heart

I began

demanded of

my father of

saying that

country well

added that Abner and I must come also, and that it was nonsense to

wish to

remain faithful to a lost cause. She begged my father to go and

draw her

diamonds from the bank and to send them to her with at least a

hundred

thousand francs. Oh! how I wept after seeing

(Torn off and gone.)

letter! Mother Catharine

to console me but

then to make. Then

and said to me, Will

to make you

England, Madame

Oh! yes, Joseph

would be so well pleased

poor fellow

the money of

family. I

From the way in which, the cabin was built, one could see any one coming who had business there. But one day — God knows how it happened — a child of the village all at once entered the chamber where I was and knew me.

“Madame Alix!” he cried, took to his heels and went down the terrace pell-mell (quatre à quatre) to give the alarm. Ten minutes later Matthieu came at a full run and covered with sweat, to tell us that all the village was in commotion and that those people to whom I had always been so good were about to come and arrest me, to deliver me to the executioners. I ran to Joseph, beside myself with affright.

“Save me, Joseph! save me!”

“I will use all my efforts for that, Mme. la Viscomtesse.” At that moment Jerome appeared. He came to say that a representative of the people was at hand and that I was lost beyond a doubt.

“Not yet,” responded Joseph. “I have foreseen this and have prepared everything to save you, Mme. la Viscomtesse, if you will but let me make myself well understood.”

“Oh, all, all! Do thou understand, Joseph, I will do everything thou desirest.”

“Then,” he said, regarding me fixedly and halting at each word — “then it is necessary that you consent to take Joseph Carpentier for your spouse.”

I thought I had [been] misunderstood and drew back haughtily.

“My son!” cried mother Catharine.

“Oh, you see,” replied Joseph, “my mother herself accuses me, and you — you, madame, have no greater confidence in me. But that is nothing; I must save you at any price. We will go from here together; we will descend to the village; we will present ourselves at the mayoralty — ”

In spite of myself I made a gesture.

“Let me speak, madame,” he said. “We have not a moment to lose. Yes, we will present ourselves at the mayoralty, and there I will espouse you, not as Claudine Leroy, but as Alix de Morainville. Once my wife you have nothing to fear. Having become one of the people, the people will protect you. After the ceremony, madame, I will hand you the certificate of our marriage, and you will tear it up the moment we shall have touched the soil of England. Keep it precious till then; it is your only safeguard. Nothing prevents me from going to England to find employment, and necessarily my wife will go with me. Are you ready, madame?”

For my only response I put my hand in his; I was too deeply moved to speak. Mother Catharine threw both her arms about her son’s neck and cried, “My noble child!” and we issued from the cottage guarded by Guillaume and his three other sons, armed to the teeth.

When the mayor heard the names and surnames of the wedding pair he turned to Joseph, saying:

“You are not lowering yourself, my boy.”

At the door of the mayoralty we found ourselves face to face with an immense crowd. I trembled violently and pressed against Joseph. He, never losing his presence of mind (sans perdre la carte), turned, saying:

“Allow me, my friends, to present to you my wife. The Viscomtesse de Morainville no longer exists; hurrah for the Citoyenne Carpentier.” And the hurrahs and cries of triumph were enough to deafen one. Those who the moment before were ready to tear me into pieces now wanted to carry me in triumph. Arrived at the house, Joseph handed me our act of marriage.

“Keep it, madame,” said he; “you can destroy it on your arrival in England.”

At length one day, three weeks after our marriage, Joseph came to tell me that he had secured passage on a vessel, and that we must sail together under the name of Citoyen and Citoyenne Carpentier. I was truly sorry to leave my adopted parents and foster-brother, yet at the bottom of my heart I was rejoiced that I was going to find my mother.

But alas! when I arrived in London, at the address that she had given me, I found there only her old friend the Chevalier d’Ivoy, who told me that my mother was dead, and that what was left of her money, with her jewels and chests, was deposited in the Bank of England. I was more dead than alive; all these things paralyzed me. But my good Joseph took upon himself to do everything for me. He went and drew what had been deposited in the bank. Indeed of money there remained but twelve thousand francs; but there were plate, jewels, pictures, and many vanities in the form of gowns and every sort of attire.

Joseph rented a little house in a suburb of London, engaged an old Frenchwoman to attend me, and he, after all my husband, made himself my servant, my gardener, my factotum. He ate in the kitchen with the maid, waited upon me at table, and slept in the garret on a pallet.

“Am I not very wicked?” said I to myself every day, especially

when I saw

his pallor and profound sadness. They had taught me in the convent

that

the ties of marriage were a sacred thing and that one could not

break

them, no matter how they might have been made; and when my

patrician pride

revolted at the thought of this union with the son of my nurse

(Evidently torn

before Alix wrote on it, as no

words are wanting in

the text.)

my heart pleaded

and pleaded

hard the cause

of poor J

Joseph. His

care, his

presence, became

more and more

necessary. I knew not how to do anything myself, but made him my

all in

all, avoiding myself every shadow of care or trouble. I must say,

moreover, that since he had married me I had a kind of fear of him

and was

afraid that I should hear him speak to me of love; but he scarcely

thought

of it, poor fellow: reverence closed his lips. Thus matters stood when

(Opposite page of the

same torn sheet. Alix

has again written

around the rent.)

one evening Joseph

entered the room

where I was read-

ing, and standing

upright be-

fore me, his hat

in his hand, said

to me that he had something to tell me. His expression was so unhappy that I felt the tears mount to my eyes.

“What is it, dear Joseph?” I asked; and when he could answer nothing on account of his emotion, I rose, crying:

“More bad news? What has happened to my nurse-mother? Speak, speak, Joseph!”

“Nothing, Mme. la Viscomtesse,” he replied. “My mother and Bastien, I hope, are well. It is of myself I wish to speak.”

Then my heart made a sad commotion in my bosom, for I thought he was about to speak of love. But not at all. He began again, in a low voice:

“I am going to America, madame.”

I sprung towards him. “You go away? You go away?” I cried. “And I, Joseph?”

“You, madame?” said he. “You have money. The Revolution will soon be over, and you can return to your country. There you will find again your friends, your titles, your fortune.”

“Stop!” I cried. “What shall I be in France? You well know my château, my palace are pillaged and burned, my parents are dead.”

“My mother and Bastien are in France,” he responded.

“But thou — thou, Joseph; what can I do without thee? Why have you accustomed me to your tenderness, to your protection, and now come threatening to leave me? Hear me plainly. If you go I go with you.”

He uttered a smothered cry and staggered like a drunken man.

“Alix — madame — ”

“I have guessed your secret,” continued I. “You seek to go because you love me — because you fear you may forget that respect which you fancy you owe me. But after all I am your wife, Joseph. I have the right to follow thee, and I am going with thee.” And slowly I drew from my dressing-case the act of our marriage.

He looked, at me, oh! in such a funny way, and — extended his arms. I threw myself into them, and for half an hour it was tears and kisses and words of love. For after all I loved Joseph, not as I had loved Abner, but altogether more profoundly.

The next day a Catholic priest blessed our marriage. A month later we left for Louisiana, where Joseph hoped to make a fortune for me. But alas! he was despairing of success, when he met Mr. Carlo, and — you know, dear girls, the rest.

Roll again and slip into its ancient silken case the small, square manuscript which some one has sewed at the back with worsted of the pale tint known as “baby-blue.” Blessed little word! Time justified the color. If you doubt it go to the Teche; ask any of the De la Houssayes — or count, yourself, the Carpentiers and Charpentiers. You will be more apt to quit because you are tired than because you have finished. And while there ask, over on the Attakapas side, for any trace that any one may be able to give of Dorothea M?ller. She too was from France: at least, not from Normandy or Paris, like Alix, but, like Françoise’s young aunt with the white hair, a German of Alsace, from a village near Strasbourg; like her, an emigrant, and, like Françoise, a voyager with father and sister by flatboat from old New Orleans up the Mississippi, down the Atchafalaya, and into the land of Attakapas. You may ask, you may seek; but if you find the faintest trace you will have done what no one else has succeeded in doing. We shall never know her fate. Her sister’s we can tell; and we shall now see how different from the stories of Alix and Françoise is that of poor Salome M?ller, even in the same land and almost in the same times.

Notes.

- Attakapas. The Attakapas were a native American tribe that lived along the Louisiana and Texas coast. The Poste des Attakapas trading post was later named St. Martin, then St. Martinville.

- Count Louis le Pelletrier de la Houssaye. Spanish Louisiana also fought the British during the American Revolution. Count de la Houssaye served under Gov. Galvez as the Captain of the 4th Dragoons.

- Where he had been fighting the insurgents at the head of his regiment. Inserted by a later hand than the author’s. — Translator. The count was fighting against the slave uprising in the Haitian Revolution.

- Grande rumeur. Huge story!

- He had lately witnessed the atrocities committed by the negroes of San Domingo. Inserted by a later hand than the author’s. — Translator.

- Maurepas, only a few months returned from exile and now at the pinnacle of royal favor. Interted by a later hand than the author’s. — Translator.

- On the 13th of July the Bastille was taken and the head of the governor De Launay was carried through the streets. Alix makes a mistake here of one day. The Bastille fell on the 14th. — Translator.

- Factotum. A general servant. From the Latin fac + totum "do everything."

Text prepared by

- Kristen Adcock

- Erika Craft

- Andrea Fite

- Cami Haden

- Jon Kelley

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

de la Houssaye, Sidonie. “Alix De Morainville.” Trans. George Washington Cable. Strange True Stories of Louisiana. Ed. George Washington Cable. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890. 121-44. Internet Archive. 2 Aug. 2007. Web. 22 May 2013. <http:// archive. org/ details/ strange true stori 00cabluoft>.