Anthology

of Louisiana Literature

George Washington Cable.

“Café des Exiles.”

THAT which in 1835 — I think he said thirty-five — was a

reality in the Rue Burgundy — I think he said Burgundy — is

now but a reminiscence. Yet so vividly was its story told

me, that at this moment the old Café des Exilés appears

before my eye, floating in the clouds of revery, and I doubt

not I see it just as it was in the old times.

An antiquated story-and-a-half Creole cottage sitting

right down on the banquette, as do the Choctaw squaws who

sell bay and sassafras and life-everlasting, with a high,

close board-fence shutting out of view the diminutive garden

on the southern side. An ancient willow droops over the

roof of round tiles, and partly hides the discolored stucco,

which keeps dropping off into the garden as though the old

café was stripping for the plunge into oblivion — disrobing

for its execution. I see, well up in the angle of the broad

side gable, shaded by its rude awning of clapboards, as the

eyes of an old dame are shaded by her wrinkled hand, the

window of Pauline. Oh for the image of the maiden, were it

but for one moment, leaning out of the casement to hang her

mocking-bird and looking

down into the garden, — where, above

the barrier of old boards, I see the top of the fig-tree,

the pale green clump of bananas, the tall palmetto with its

jagged crown, Pauline's own two orange-trees holding up

their hands toward the window, heavy with the promises of

autumn; the broad, crimson mass of the many-stemmed

oleander, and the crisp boughs of the pomegranate loaded

with freckled apples, and with here and there a lingering

scarlet blossom.

The Café des Exilés, to use a figure, flowered, bore

fruit, and dropped it long ago — or rather Time and Fate,

like some uncursed Adam and Eve, came side by side and cut

away its clusters, as we sever the golden burden of the

banana from its stem; then, like a banana which has borne

its fruit, it was razed to the ground and made way for a

newer, brighter growth. I believe it would set every tooth

on edge should I go by there now, — now that I have heard the

story, — and see the old site covered by the "Shoo-fly

Coffee-house." Pleasanter far to close my eyes and call to

view the unpretentious portals of the old café, with her

children — for such those exiles seem to me — dragging their

rocking-chairs out, and sitting in their wonted group under

the long, out-reaching eaves which shaded the banquette of

the Rue Burgundy.

It was in 1835 that the Café des Exilés was, as one might

say, in full blossom. Old M. D'Hemecourt, father of Pauline

and host of the café, himself a refugee from San Domingo,

was the cause — at least the human cause — of its opening. As

its white-curtained

glazed doors expanded, emitting a little

puff of his own cigarette smoke, it was like the bursting of

catalpa blossoms, and the exiles came like bees, pushing

into the tiny room to sip its rich variety of tropical

sirups, its lemonades, its orangeades, its orgeats, its

barley-waters, and its outlandish wines, while they talked

of dear home — that is to say, of Barbadoes, of Martinique,

of San Domingo, and of Cuba.

There were Pedro and Benigno, and Fernandez and Francisco,

and Benito. Benito was a tall, swarthy man, with immense

gray moustachios, and hair as harsh as tropical grass and

gray as ashes. When he could spare his cigarette from his

lips, he would tell you in a cavernous voice, and with a

wrinkled smile, that he was "a-t-thorty-seveng."

There was Martinez of San Domingo, yellow as a canary,

always sitting with one leg curled under him, and holding

the back of his head in his knitted fingers against the back

of his rocking-chair. Father, mother, brother, sisters,

all, had been massacred in the struggle of '21 and '22; he

alone was left to tell the tale, and told it often, with

that strange, infantile insensibility to the solemnity of

his bereavement so peculiar to Latin people.

But, besides these, and many who need no mention, there

were two in particular, around whom all the story of the

Café des Exilés, of old M. D'Hemecourt and of Pauline, turns

as on a double centre. First, Manuel Mazaro, whose small,

restless eyes were as black and bright as those of a mouse,

whose light talk became his dark girlish face, and whose

redundant

locks curled so prettily and so wonderfully black

under the fine white brim of his jaunty Panama. He had the

hands of a woman, save that the nails were stained with the

smoke of cigarettes. He could play the guitar delightfully,

and wore his knife down behind his coat-collar.

The second was "Major" Galahad Shaughnessy. I imagine I

can see him, in his white duck, brass-buttoned roundabout,

with his sabreless belt peeping out beneath, all his

boyishness in his sea-blue eyes, leaning lightly against the

door-post of the Café des Exilés as a child leans against

his mother, running his fingers over a basketful of fragrant

limes, and watching his chance to strike some solemn Creole

under the fifth rib with a good old Irish joke.

Old D'Hemecourt drew him close to his bosom. The Spanish

Creoles were, as the old man termed it, both cold and hot,

but never warm. Major Shaughnessy was warm, and it was no

uncommon thing to find those two apart from the others,

talking in an undertone, and playing at confidantes like two

school-girls. The kind old man was at this time drifting

close up to his sixtieth year. There was much he could tell

of San Domingo, whither he had been carried from Martinique

in his childhood, whence he had become a refugee to Cuba,

and thence to New Orleans in the flight of 1809.

It fell one day to Manuel Mazaro's lot to discover, by

sauntering within earshot, that to Galahad Shaughnessy only,

of all the children of the Café des Exilés, the good host

spoke long and confidentially concerning his daughter. The

words, half heard and magnified like objects seem in a fog,

meaning Manuel Mazaro knew not what, but made portentous by

his suspicious nature, were but the old man's recital of the

grinding he had got between the millstones of his poverty

and his pride, in trying so long to sustain, for little

Pauline's sake, that attitude before society which earns

respect from a surface-viewing world. It was while he was

telling this that Manuel Mazaro drew near; the old man

paused in an embarrassed way; the Major, sitting sidewise in

his chair, lifted his cheek from its resting-place on his

elbow; and Mazaro, after standing an awkward moment, turned

away with such an inward feeling as one may guess would

arise in a heart full of Cuban blood, not unmixed with

Indian.

As he moved off, M. D'Hemecourt resumed: that in a last

extremity he had opened, partly from dire want, partly for

very love to homeless souls, the Café des Exilés. He had

hoped that, as strong drink and high words were to be alike

unknown to it, it might not prejudice sensible people; but

it had. He had no doubt they said among themselves, "She is

an excellent and beautiful girl and deserving all respect;"

and respect they accorded, but their respects they never

came to pay.

"A café is a café," said the old gentleman. "It is nod

possib' to ezcape him, aldough de Café des Exilés is

differen' from de rez."

"It's different from the Café des Réfugiés ," suggested the

Irishman.

"Differen' as possib'," replied M. D'Hemecourt. He looked

about upon the walls. The shelves were luscious with ranks

of cooling sirups which he alone knew how to make. The

expression of his face changed from sadness to a gentle

pride, which spoke without words, saying — and let our story

pause a moment to hear it say:

"If any poor exile, from any island where guavas or

mangoes or plantains grow, wants a draught which will make

him see his home among the cocoa-palms, behold the Café des

Exilés ready to take the poor child up and give him the

breast! And if gold or silver he has them not, why Heaven

and Santa Maria, and Saint Christopher bless him! It makes

no difference. Here is a rocking-chair, here a cigarette,

and here a light from the host's own tinder. He will pay

when he can."

As this easily pardoned pride said, so it often occurred;

and if the newly come exile said his father was a

Spaniard — Come!" old M. D'Hemecourt would cry; "another

glass; it is an innocent drink; my mother was a Castilian."

But, if the exile said his mother was a Frenchwoman, the

glasses would be forthcoming all the same, for "My father,"

the old man would say, "was a Frenchman of Martinique, with

blood as pure as that wine and a heart as sweet as this

honey; come, a glass of orgeat;" and he would bring it

himself in a quart tumbler.

Now, there are jealousies and jealousies. There are

people who rise up quickly and kill, and there are others

who turn their hot thoughts over silently in

their minds as

a brooding bird turns her eggs in the nest. Thus did Manuel

Mazaro, and took it ill that Galahad should see a vision in

the temple while he and all the brethren tarried without.

Pauline had been to the Café des Exilés in some degree what

the image of the Virgin was to their churches at home; and

for her father to whisper her name to one and not to another

was, it seemed to Mazaro, as if the old man, were he a

sacristan, should say to some single worshiper, "Here, you

may have this madonna; I make it a present to you." Or, if

such was not the handsome young Cuban's feeling, such, at

least, was the disguise his jealousy put on. If Pauline was

to be handed clown from her niche, why, then, farewell Café

des Exilés. She was its preserving influence, she made the

place holy; she was the burning candles on the altar.

Surely the reader will pardon the pen that lingers in the

mention of her.

And yet I know not how to describe the forbearing,

unspoken tenderness with which all these exiles regarded the

maiden. In the balmy afternoons, as I have said, they

gathered about their mother's knee, that is to say, upon the

banquette outside the door. There, lolling back in their

rocking-chairs, they would pass the evening hours with

oft-repeated tales of home; and the moon would come out and

glide among the clouds like a silver barge among islands

wrapped in mist, and they loved the silently gliding orb

with a sort of worship, because from her soaring height she

looked down at the same moment upon them and upon their

homes in the far Antilles. It was somewhat thus

that they

looked upon Pauline as she seemed to them held up half way

to heaven, they knew not how. Ah! those who have been

pilgrims; who have wandered out beyond harbor and light;

whom fate hath led in lonely paths strewn with thorns and

briers not of their own sowing; who, homeless in a land of

homes, see windows gleaming and doors ajar, but not for

them, — it is they who well understand what the worship is

that cries to any daughter of our dear mother Eve whose

footsteps chance may draw across the path, the silent,

beseeching cry, "Stay a little instant that I may look

upon you. Oh, woman, beautifier of the earth! Stay till I

recall the face of my sister; stay yet a moment while I look

from afar, with helpless-hanging hands, upon the softness of

thy cheek, upon the folded coils of thy shining hair; and my

spirit shall fall down and say those prayers which I may

never again — God knoweth — say at home."

She was seldom seen; but sometimes, when the lounging

exiles would be sitting in their afternoon circle under the

eaves, and some old man would tell his tale of fire and

blood and capture and escape, and the heads would lean

forward from the chair-backs and a great stillness would

follow the ending of the story, old M. D'Hemecourt would all

at once speak up and say, laying his hands upon the

narrator's knee, "Comrade, your throat is dry, here are

fresh limes; let my dear child herself come and mix you a

lemonade." Then the neighbors over the way, sitting about

their doors, would by and by softly say, "See, see! there is

Pauline!" and all the exiles would rise from

their

rocking-chairs, take off their hats and stand as men stand

in church, while Pauline came out like the moon from a

cloud, descended the three steps of the café door, and stood

with waiter and glass, a new Rebecca with her pitcher,

before the swarthy wanderer.

What tales that would have been tear-compelling, nay,

heart-rending, had they not been palpable inventions, the

pretty, womanish Mazaro from time to time poured forth, in

the ever ungratified hope that the goddess might come clown

with a draught of nectar for him, it profiteth not to

recount; but I should fail to show a family feature of the

Café des Exilés did I omit to say that these make-believe

adventures were heard with every mark of respect and

credence; while, on the other hand, they were never

attempted in the presence of the Irishman. He would have

moved an eyebrow, or made some barely audible sound, or

dropped some seemingly innocent word, and the whole company,

spite of themselves, would have smiled. Wherefore, it may

be doubted whether at any time the curly-haired young Cuban

had that playful affection for his Celtic comrade, which a

habit of giving little velvet taps to Galahad's cheek made a

show of.

Such was the Café des Exilés, such its inmates, such its

guests, when certain apparently trivial events began to fall

around it as germs of blight fall upon corn, and to bring

about that end which cometh to all things.

The little seed of jealousy, dropped into the heart of

Manuel Mazaro, we have already taken into account.

Galahad Shaughnessy began to be specially active in

organizing a society of Spanish Americans, the

design of

which, as, set forth in its manuscript constitution, was to

provide proper funeral honors to such of their membership as

might be overtaken by death; and, whenever it was

practicable, to send their ashes to their native land. Next

to Galahad in this movement was an elegant old Mexican

physician, Dr. ——, — his name escapes me — whom the Café

des Exilés sometimes took upon her lap — that is to say

door-step — but whose favorite resort was the old Café des

Réfugiés in the Rue Royale (Royal Street, as it was

beginning to be called). Manuel Mazaro was made secretary.

It was for some reason thought judicious for the society

to hold its meetings in various places, now here, now there;

but the most frequent rendezvous was the Café des Exilés; it

was quiet; those Spanish Creoles, however they may afterward

cackle, like to lay their plans noiselessly, like a hen in a

barn. There was a very general confidence in this old

institution, a kind of inward assurance that "mother

wouldn't tell;" though, after all, what great secrets could

there be connected with a mere burial society?

Before the hour of meeting, the Café des Exilés always

sent away her children and closed her door. Presently they

would commence returning, one by one, as a flock of wild

fowl will do, that has been startled up from its accustomed

haunt. Frequenters of the Café des Réfugiés also would

appear. A small gate in the close garden-fence let them

into a room behind the café proper, and by and by the

apartment would be full of dark-visaged men conversing in

the low,

courteous tone common to their race. The shutters

of doors and windows were closed and the chinks stopped with

cotton; some people are so jealous of observation.

On a certain night after one of these meetings had

dispersed in its peculiar way, the members retiring two by

two at intervals, Manuel Mazaro and M. D'Hemecourt were left

alone, sitting close together in the dimly lighted room, the

former speaking, the other, with no pleasant countenance,

attending. It seemed to the young Cuban a proper

precaution — he was made of precautions — to speak in English.

His voice was barely audible.

"—— sayce to me, 'Manuel, she t-theeng I want-n to marry

hore.' Señor, you shouth 'ave see' him laugh!"

M. D'Hemecourt lifted up his head, and laid his hand upon

the young man's arm.

"Manuel Mazaro," he began, "iv dad w'ad you say is nod" —

The Cuban interrupted.

"If is no' t-thrue you will keel Manuel Mazaro? — a'

r-r-right-a!"

"No," said the tender old man, "no, bud h-I am positeef

dad de Madjor will shood you."

Mazaro nodded, and lifted one finger for attention.

"—— sayce to me, 'Manuel, you goin' tell-a Señor

D'Hemecourt, I fin'-a you some nigh' an' cut-a you' heart

ou'. An' I sayce to heem-a, 'Boat-a if Señor D'Hemecourt he

fin'-in' ou' frone Pauline'"——

"Silence!" fiercely cried the old man. "My God!

'Sieur

Mazaro, neider you, neider somebody helse s'all h'use de nem

of me daughter. It is nod possib' dad you s'all spick him!

I cannot pearmid thad."

While the old man was speaking these vehement words, the

Cuban was emphatically nodding approval.

"Co-rect-a, co-rect-a, Señor," he replied. "Señor, you'

r-r-right-a; escuse-a me, Señor, escuse-a me. Señor

D'Hemecourt, Mayor Shaughness', when he talkin' wi' me he

usin' hore-a name o the t-thime-a!"

"My fren'," said M. D'Hemecourt, rising and speaking with

labored control, "I muz tell you good nighd. You 'ave

sooprise me a verry gred deal. I s'all investigade doze

ting; an', Manuel Mazaro, h-I am a hole man; bud I will

requez you, iv dad wad you say is nod de true, my God! not

to h-ever ritturn again ad de Café des Exilés."

Mazaro smiled and nodded. His host opened the door into

the garden, and, as the young man stepped out, noticed even

then how handsome was his face and figure, and how the odor

of the night jasmine was filling the air with an almost

insupportable sweetness. The Cuban paused a moment, as if

to speak, but checked himself, lifted his girlish face, and

looked up to where the daggers of the palmetto-tree were

crossed upon the face of the moon, dropped his glance,

touched his Panama, and silently followed by the bare-headed

old man, drew open the little garden-gate, looked cautiously

out, said good-night, and stepped into the street.

As M. D'Hemecourt returned to the door through which he

had come, he uttered an ejaculation of

astonishment.

Pauline stood before him. She spoke hurriedly in French.

"Papa, papa, it is not true."

"No, my child," he responded, "I am sure it is not true; I

am sure it is all false; but why do I find you out of bed so

late, little bird? The night is nearly gone."

He laid his hand upon her cheek.

"Ah, papa. I cannot deceive you. I thought Manuel would

tell you something of this kind, and I listened."

The father's face immediately betrayed a new and deeper

distress.

"Pauline, my child," he said with tremulous voice, "if

Manuel's story is all false, in the name of Heaven how could

you think he was going to tell it?"

He unconsciously clasped his hands. The good child had

one trait which she could not have inherited from her

father; she was quick-witted and discerning; yet now she

stood confounded.

"Speak, my child," cried the alarmed old man; "speak! let

me live, and not die."

"Oh, papa," she cried, "I do not know!"

The old man groaned.

"Papa, papa," she cried again, "I felt it; I know not how;

something told me."

"Alas!" exclaimed the old man, "if it was your

conscience!"

"No, no, no, papa," cried Pauline, "but I was afraid of

Manuel Mazaro, and I think he hates him — and I think he will

hurt him in any way he can

— and I know he will even try to

kill him. Oh! my God!"

She struck her hands together above her head, and burst

into a flood of tears. Her father looked upon her with such

sad sternness as his tender nature was capable of. He laid

hold of one of her arms to draw a hand from the face whither

both hands had gone.

"You know something else," he said; "you know that the

Major loves you, or you think so: is it not true?"

She dropped both hands, and, lifting her streaming eyes

that had nothing to hide straight to his, suddenly said:

"I would give worlds to think so!" and sunk upon the

floor.

He was melted and convinced in one instant.

"Oh, my child, my child," he cried, trying to lift her.

"Oh, my poor little Pauline, your papa is not angry. Rise,

my little one; so; kiss me; Heaven bless thee! Pauline,

treasure, what shall I do with thee? Where shall I hide

thee?"

"You have my counsel already, papa."

"Yes, my child, and you were right. The Café des Exilés

never should have been opened. It is no place for you; no

place at all."

"Let us leave it," said Pauline.

"Ah! Pauline, I would close it to-morrow if I could, but

now it is too late; I cannot."

"Why?" asked Pauline pleadingly.

She had cast an arm about his neck. Her tears sparkled

with a smile.

"My daughter, I cannot tell you; you must go now to bed;

good-night — or good-morning; God keep you!"

"Well, then, papa," she said, "have no fear; you need not

hide me; I have my prayer-book, and my altar, and my garden,

and my window; my garden is my fenced city, and my window my

watch-tower; do you see?"

"Ah! Pauline," responded the father, "but I have been

letting the enemy in and out at pleasure."

"Good-night," she answered, and kissed him three times on

either cheek; "the blessed Virgin will take care of us;

good-night; he never said those things; not he;

good-night."

The next evening Galahad Shaughnessy and Manuel Mazaro met

at that "very different" place, the Café des Réfugiés.

There was much free talk going on about Texan annexation,

about chances of war with Mexico, about San Domingan

affairs, about Cuba and many et-ceteras. Galahad was in his

usual gay mood. He strode about among a mixed company of

Louisianais, Cubans, and Americains, keeping them in a great

laugh with his account of one of Ole Bull's concerts, and

how he had there extorted an invitation from M. and Mme.

Devoti to attend one of their famous children's fancy dress

balls.

"Halloo!" said he as Mazaro approached, "heer's the

etheerial Angelica herself. Look-ut heer, sissy, why ar'n't

ye in the maternal arms of the Café des Exilés?"

Mazaro smiled amiably and sat down. A moment

after, the

Irishman, stepping away from his companions, stood before

the young Cuban, and asked, with a quiet business air:

"D'ye want to see me, Mazaro?"

The Cuban nodded, and they went aside. Mazaro, in a few

quick words, looking at his pretty foot the while, told the

other on no account to go near the Café des Exilés, as there

were two men hanging about there, evidently watching for

him, and —

"Wut's the use o' that?" asked Galahad; "I say, wut's the

use o' that?"

Major Shaughnessy's habit of repeating part of his words

arose from another, of interrupting any person who might be

speaking.

"They must know — I say they must know that whenever I'm

nowhurs else I'm heer. What do they want?"

Mazaro made a gesture, signifying caution and secrecy, and

smiled, as if to say, "You ought to know."

"Aha!" said the Irishman softly. "Why don't they come

here?"

"Z-afrai'," said Mazaro; "d'they frai' to do an'teen een

d-these-a crowth."

"That's so," said the Irishman; "I say, that's so. If I

don't feel very much like go-un, I'll not go; I say, I'll

not go. We've no business to-night, eh, Mazaro?"

"No, Señor."

A second evening was much the same, Mazaro repeating his

warning. But when, on the third evening,

the Irishman again

repeated his willingness to stay away from the Café des

Exilés unless he should feel strongly impelled to go, it was

with the mental reservation that he did feel very much in

that humor, and, unknown to Mazaro, should thither repair,

if only to see whether some of those deep old fellows were

not contriving a practical joke.

"Mazaro," said he, "I'm go-un around the caurnur a bit; I

want ye to wait heer till I come back. I say I want ye to

wait heer till I come back; I'll be gone about

three-quarters of an hour."

Mazaro assented. He saw with satisfaction the Irishman

start in a direction opposite that in which lay the Café des

Exilés, tarried fifteen or twenty minutes, and then,

thinking he could step around to the Café des Exilés and

return before the expiration of the allotted time, hurried

out.

Meanwhile that peaceful habitation sat in the moonlight

with her children about her feet. The company outside the

door was somewhat thinner than common. M. D'Hemecourt was

not among them, but was sitting in the room behind the café.

The long table which the burial society used at their

meetings extended across the apartment, and a lamp had been

placed upon it. M. D'Hemecourt sat by the lamp. Opposite

him was a chair, which seemed awaiting an expected occupant.

Beside the old man sat Pauline. They were talking in

cautious undertones, and in French.

"No," she seemed to insist; "we do not know that he

refuses to come. We only know that Manuel says so."

The father shook his head sadly. "When has he ever staid

away three nights together before?" he asked. "No, my

child; it is intentional. Manuel urges him to come, but he

only sends poor excuses."

"But," said the girl, shading her face from the lamp and

speaking with some suddenness, "why have you not sent word

to him by some other person?"

M. D'Hemecourt looked up at his daughter a moment, and

then smiled at his own simplicity.

"Ah!" he said. "Certainly; and that is what I will — run

away, Pauline. There is Manuel, now, ahead of time!"

A step was heard inside the café. The maiden, though she

knew the step was not Mazaro's, rose hastily, opened the

nearest door, and disappeared. She had barely closed it

behind her when Galahad Shaughnessy entered the apartment.

D'Hemecourt rose up, both surprised and confused.

"Good-evening, Munsher D'Himecourt," said the Irishman.

"Munsher D'Himecourt, l know it's against rules — I say, I

know it's against rules to come in here, but" — smiling, — "I

want to have a private wurd with ye. I say, I want to have

a private wurd with ye."

In the closet of bottles the maiden smiled triumphantly.

She also wiped the dew from her forehead, for the place was

very close and warm.

With her father was no triumph. In him sadness and doubt

were so mingled with anger that he dared not lift his eyes,

but gazed at the knot in the wood of the table, which looked

like a caterpillar curled up.

Mazaro, he concluded, had really asked the Major to come.

"Mazaro tol' you?" he asked.

"Yes," answered the Irishman. "Mazaro told me I was

watched, and asked" —

"Madjor," unluckily interrupted the old man, suddenly

looking up and speaking with subdued fervor, "for w'y — iv

Mazaro tol' you — for w'y you din come more sooner? Dad is

one 'eavy charge again' you."

"Didn't Mazaro tell ye why I didn't come?" asked the

other, beginning to be puzzled at his host's meaning.

"Yez," replied M. D'Hemecourt, "bud one brev zhenteman

should not be afraid of" —

The young man stopped him with a quiet laugh. "Munsher

D'Himecourt," said he, "I'm nor afraid of any two men

living — I say I'm nor afraid of any two men living, and

certainly not of the two that's bean a-watchin' me lately,

if they're the two I think they are."

M. D'Hemecourt flushed in a way quite incomprehensible to

the speaker, who nevertheless continued:

"It was the charges," he said, with some slyness in his

smile. "They are heavy, as ye say, and that's the very

reason — I say that's the very reason why I staid away, ye

see, eh? I say that's the very reason I staid away."

Then, indeed, there was a dew for the maiden to wipe from

her brow, unconscious that every word that was being said

bore a different significance in the mind of each of the

three. The old man was agitated.

"Bud, sir," he began, shaking his head and lifting his

hand.

"Bless yer soul, Munsher D'Himecourt," interrupted the

Irishman. "Wut's the use o' grapplin' two cut-throats,

when" —

"Madjor Shaughnessy!" cried M. D'Hemecourt, losing all

self-control. "H-I am nod a cud-troad, Madjor Shaughnessy,

h-an I 'ave a r-r-righd to wadge you.

The Major rose from his chair.

"What d'ye mean?" he asked vacantly, and then: "Look-ut

here, Munsher D'Himecourt, one of uz is crazy. I say one" —

"No, sar-r-r!" cried the other, rising and clenching his

trembling fist. "H-I am nod crezzy. I 'ave de righd to

wadge dad man wad mague rimark aboud me dotter."

"I never did no such a thing."

"You did."

"I never did no such a thing."

"Bud you 'ave jus hacknowledge' — "

"I never did no such a thing, I tell ye, and the man

that's told ye so is a liur."

"Ah-h-h-h!" said the old man, wagging his finger.

"Ah-h-h-h! You call Manuel Mazaro one liar?"

The Irishman laughed out.

"Well, I should say so!"

He motioned the old man into his chair, and both sat down

again.

"Why, Munsher D'Himecourt, Mazaro's been keepin' me away

from heer with a yarn about two

Spaniards watchin' for me.

That's what I came in to ask ye about. My dear sur, do ye

s'pose I wud talk about the goddess — I mean, yer

daughter — to the likes o' Mazaro — I say to the likes o'

Mazaro?"

To say the old man was at sea would be too feeble an

expression — he was in the trough of the sea, with a

hurricane of doubts and fears whirling around him. Somebody

had told a lie, and he, having struck upon its sunken

surface, was dazed and stunned. He opened his lips to say

he knew not what, when his ear caught the voice of Manuel

Mazaro, replying to the greeting of some of his comrades

outside the front door.

"He is comin'!" cried the old man. "Mague you'sev hide,

Madjor; do not led 'im kedge you, Mon Dieu!"

The Irishman smiled.

"The little yellow wretch!" said he quietly, his blue eyes

dancing. "I'm goin' to catch him."

A certain hidden hearer instantly made up her mind to rush

out between the two young men and be a heroine.

"Non, non!" exclaimed M. D'Hemecourt excitedly. "Nod in

de Café des Exilés — nod now, Madjor. Go in dad door, hif

you pliz, Madjor. You will heer 'im w'at he 'ave to say.

Mague you'sev de troub'. Nod dad door — diz one."

The Major laughed again and started toward the door

indicated, but in an instant stopped.

"I can't go in theyre," he said. "That's yer daughter's

room."

"

Oui, oui, mais! " cried the other softly, but Mazaro's

step was near.

"I'll just slip in heer," and the amused Shaughnessy

tripped lightly to the closet door, drew it open in spite of

a momentary resistance from within which he had no time to

notice, stepped into a small recess full of shelves and

bottles, shut the door, and stood face to face — the broad

moonlight shining upon her through a small, high-grated

opening on one side — with Pauline. At the same instant the

voice of the young Cuban sounded in the room.

Pauline was in a great tremor. She made as if she would

have opened the door and fled, but the Irishman gave a

gesture of earnest protest and re-assurance. The re-opened

door might make the back parlor of the Café des Exilés a

scene of blood. Thinking of this, what could she do? She

staid.

"You goth a heap-a thro-vle, Señor," said Manuel Mazaro,

taking the seat so lately vacated. He had patted M.

D'Hemecourt tenderly on the back and the old gentleman had

flinched; hence the remark, to which there was no reply.

"Was a bee crowth a' the Café the Réfugiés," continued

the young man.

"Bud, w'ere dad Madjor Shaughnessy?" demanded M.

D'Hemecourt, with the little sternness he could command.

"Mayor Shaughness' — yez-a; was there; boat-a," with a

disparaging smile and shake of the head, "he woon-a come-a

to you, Señor, oh! no."

The old man smiled bitterly.

"Non?" he asked.

"Oh, no, Señor!" Mazaro drew his chair closer. "Señor;"

he paused, — "eez a-vary bath-a fore-a you thaughter, eh?"

"W'at?" asked the host, snapping like a tormented dog.

"D-theze talkin' 'bou'," answered the young man; "d-theze

coffee-howces noth a goo' plaze-a fore hore, eh?"

The Irishman and the maiden looked into each other's eyes

an instant, as people will do when listening; but Pauline's

immediately fell, and when Mazaro's words were understood,

her blushes became visible even by moonlight.

"He's r-right!" emphatically whispered Galahad.

She attempted to draw back a step, but found herself

against the shelves. M. D'Hemecourt had not answered.

Mazaro spoke again.

"Boat-a you canno' help-a, eh? I know, 'out-a she gettin'

marry, eh?"

Pauline trembled. Her father summoned all his force and

rose as if to ask his questioner to leave him; but the

handsome Cuban motioned him down with a gesture that seemed

to beg for only a moment more.

"Señor, if a-was one man whath lo-va you' thaughter, all

is possiblee to lo-va."

Pauline, nervously braiding some bits of wire which she

had unconsciously taken from a shelf, glanced up — against

her will, — into the eyes of Galahad. They were looking so

steadily down upon her that with a

great leap of the heart

for joy she closed her own and half turned away. But Mazaro

had not ceased.

"All is possiblee to lo-va, Señor, you shouth-a let marry

hore an' tak'n 'way frone d'these plaze, Señor."

"Manuel Mazaro," said M. D'Hemecourt, again rising, "you

'ave say enough."

"No, no, Señor; no, no; I want tell-a you — is a-one

man — whath lo-va you' thaughter; an' I knowee him!"

Was there no cause for quarrel, after all? Could it be

that Mazaro was about to speak for Galahad? The old man

asked in his simplicity:

"Madjor Shaughnessy?"

Mazaro smiled mockingly.

"Mayor Shaughness'," he said; "oh, no; not Mayor

Shaughness'!"

Pauline could stay no longer; escape she must, though it

be in Manuel Mazaro's very face. Turning again and looking

up into Galahad's face in a great fright, she opened her

lips to speak, but —

"Mayor Shaughness'," continued the Cuban; "he nev'r-a

lo-va you' thaughter."

Galahad was putting the maiden back from the door with his

hand.

"Pauline," he said, "it's a lie!"

"An', Señor," pursued the Cuban, "if a was possiblee you'

thaughter to lo-va heem, a-wouth-a be worse-a kine in worlt;

but, Señor, I" —

M. D'Hemecourt made a majestic sign for silence. He had

resumed his chair, but he rose up once more, took the

Cuban's hat from the table and tendered it to him.

"Manuel Mazaro, you 'ave" —

"Señor, I goin' tell you" —

"Manuel Mazaro, you" —

"Boat-a, Señor" —

"Bud, Manuel Maz" —

"Señor, escuse-a me" —

"Huzh!" cried the old man. "Manuel Mazaro, you 'ave

desceive' me! You 'ave mocque me, Manu" —

"Señor," cried Mazaro, "I swear-a to you that all-a what I

sayin' ees-a" —

He stopped aghast. Galahad and Pauline stood before him.

"Is what?" asked the blue-eyed man, with a look of quiet

delight on his face, such as Mazaro instantly remembered to

have seen on it one night when Galahad was being shot at in

the Sucking Calf Restaurant in St. Peter Street.

The table was between them, but Mazaro's hand went upward

toward the back of his coat-collar.

"Ah, ah!" cried the Irishman, shaking his head with a

broader smile and thrusting his hand threateningly into his

breast; "don't ye do that! just finish yer speech."

"Was-a notthin'," said the Cuban, trying to smile back.

"Yer a liur," said Galahad.

"No," said Mazaro, still endeavoring to smile through his

agony; "z-was on'y tellin' Señor D'Hemecourt someteen z-was

t-thrue."

"And I tell ye," said Galahad, "ye'r a liur, and to be so

kind an' get yersel' to the front stoop, as I'm desiruz o'

kickin' ye before the crowd."

"Madjor!" cried D'Hemecourt —

"Go," said Galahad, advancing a step toward the Cuban.

Had Manuel Mazaro wished to personate the prince of

darkness, his beautiful face had the correct expression for

it. He slowly turned, opened the door into the café, sent

one glowering look behind, and disappeared.

Pauline laid her hand upon her lover's arm.

"Madjor," began her father.

"Oh, Madjor and Madjor," said the Irishman; "Munsher

D'Hemecourt, just say 'Madjor, heer's a gude wife fur ye,'

and I'll let the little serpent go."

Thereupon, sure enough, both M. D'Hemecourt and his

daughter, rushing together, did what I have been hoping all

along, for the reader's sake, they would have dispensed

with; they burst into tears; whereupon the Major, with his

Irish appreciation of the ludicrous, turned away to hide his

smirk and began good-humoredly to scratch himself first on

the temple and then on the thigh.

Mazaro passed silently through the group about the

door-steps, and not many minutes afterward, Galahad

Shaughnessy, having taken a place among the exiles, rose

with the remark that the old gentleman would doubtless be

willing to tell them good-night. Good-night was accordingly

said, the Café des Exilés closed her windows, then her

doors, winked a moment or two through the cracks in the

shutters and then went fast asleep.

The Mexican physician, at Galahad's request, told Mazaro

that at the next meeting of the burial society

he might and

must occupy his accustomed seat without fear of molestation;

and he did so.

The meeting took place some seven days after the affair in

the back parlor, and on the same ground. Business being

finished, Galahad, who presided, stood up, looking, in his

white duck suit among his darkly-clad companions, like a

white sheep among black ones, and begged leave to order

"dlasses" from the front room. I say among black sheep;

yet, I suppose, than that double row of languid, effeminate

faces, one would have been taxed to find a more

harmless-looking company. The glasses were brought and

filled.

"Gentlemen," said Galahad, "comrades, this may be the last

time we ever meet together an unbroken body."

Martinez of San Domingo, he of the horrible experience,

nodded with a lurking smile, curled a leg under him and

clasped his fingers behind his head.

"Who knows," continued the speaker, "but Señor Benito,

though strong and sound and har'ly thirty-seven" — here all

smiled — "may be taken ill to-morrow?"

Martinez smiled across to the tall, gray Benito on

Galahad's left, and he, in turn, smilingly showed to the

company a thin, white line of teeth between his moustachios

like distant reefs.

"Who knows," the young Irishman proceeded to inquire, "I

say, who knows but Pedro, theyre, may be struck wid a

fever?"

Pedro, a short, compact man of thoroughly mixed

blood, and

with an eyebrow cut away, whose surname no one knew, smiled

his acknowledgments.

"Who knows?" resumed Galahad, when those who understood

English had explained in Spanish to those who did not, "but

they may soon need the services not only of our good doctor

heer, but of our society; and that Fernandez and Benigno,

and Gonzalez and Dominguez, may not be chosen to see, on

that very schooner lying at the

Picayune Tier

just now,

their beloved remains and so forth safely delivered into the

hands and lands of their people. I say, who knows bur it

may be so!"

|

|

The Picayune Tier.

Public domain photo.

|

The company bowed graciously as who should say,

"Well-turned phrases, Señor — well-turned."

"And amigos, if so be that such is their approoching fate,

I will say:"

He lifted his glass, and the rest did the same.

"I say, I will say to them, Creoles, countrymen, and

lovers, boun voyadge an' good luck to ye's."

For several moments there was much translating, bowing,

and murmured acknowledgments; Mazaro said: "Bueno!" and all

around among the long double rank of moustachioed lips

amiable teeth were gleaming, some white, some brown, some

yellow, like bones in the grass.

"And now, gentlemen," Galahad recommenced, "fellow-exiles,

once more. Munsher D'Himecourt, it was yer practice, until

lately, to reward a good talker with a glass from the hands

o' yer daughter." (Si, si!) "I'm bur a poor speaker."

(Si, si, Señor, z-a-fine-a kin'-a can be; si!)

"However, I'll ask ye,

not knowun bur it may be the last time we all

meet together, if ye will not let the goddess of the Café

des Exilés grace our company with her presence for just

about one minute?" (Yez-a, Señor; si; yez-a; oui.)

Every head was turned toward the old man, nodding the

echoed request.

"Ye see, friends," said Galahad in a true Irish whisper,

as M. D'Hemecourt left the apartment, "her poseetion has

been a-growin' more and more embarrassin' daily, and the

operaytions of our society were likely to make it wurse in

the future; wherefore I have lately taken steps — I say I

tuke steps this morn to relieve the old gentleman's

distresses and his daughter's" —

He paused. M. D'Hemecourt entered with Pauline, and the

exiles all rose up. Ah! — but why say again she was lovely?

Galahad stepped forward to meet her, took her hand, led

her to the head of the board, and turning to the company,

said:

"Friends and fellow-patriots, Misthress Shaughnessy."

There was no outburst of astonishment — only the same old

bowing, smiling, and murmuring of compliment. Galahad

turned with a puzzled look to M. D'Hemecourt, and guessed

the truth. In the joy of an old man's heart he had already

that afternoon told the truth to each and every man

separately, as a secret too deep for them to reveal, but too

sweet for him to keep. The Major and Pauline were man and

wife.

The last laugh that was ever heard in the Café des Exilés

sounded softly through the room.

"Lads," said the Irishman. "Fill yer dlasses. Here's to

the Café des Exilés, God bless her!"

And the meeting slowly adjourned.

Two days later, signs and rumors of sickness began to find

place about the Café des Réfugiés, and the Mexican physician

made three calls in one day. It was said by the people

around that the tall Cuban gentleman named Benito was very

sick in one of the back rooms. A similar frequency of the

same physician's calls was noticed about the Café des

Exilés.

"The man with one eyebrow," said the neighbors, "is sick.

Pauline left the house yesterday to make room for him."

"Ah! is it possible?"

"Yes, it is really true; she and her husband. She took

her mocking-bird with her; he carried it; he came back

alone."

On the next afternoon the children about the Café des

Réfugiés enjoyed the spectacle of the invalid Cuban moved on

a trestle to the Café des Exilés, although he did not look

so deathly sick as they could have liked to see him, and on

the fourth morning the doors of the Café des Exilés remained

closed. A black-bordered funeral notice, veiled with crape,

announced that the great Caller-home of exiles had served

his summons upon Don Pedro Hernandez (surname borrowed for

the occasion), and Don Carlos Mendez y Benito.

The hour for the funeral was fixed at four

p.m. It

never took place. Down at the Picayune Tier on the river bank

there was, about two o'clock that same day, a slight

commotion, and those who stood aimlessly about a small, neat

schooner, said she was "seized." At four there suddenly

appeared before the Café des Exilés a squad of men with

silver crescents on their breasts — police officers. The old

cottage sat silent with closed doors, the crape hanging

heavily over the funeral notice like a widow's veil, the

little unseen garden sending up odors from its hidden

censers, and the old weeping-willow bending over all.

"Nobody here?" asks the leader.

The crowd which has gathered stares without answering.

As quietly and peaceably as possible the officers pry open

the door. They enter, and the crowd pushes in after. There

are the two coffins, looking very heavy and solid, lying in

state but unguarded.

The crowd draws a breath of astonishment. "Are they going

to wrench the tops off with hatchet and chisel?"

Rap, rap, rap; wrench, rap, wrench. Ah! the cases come

open.

"Well kept?" asks the leader flippantly.

"Oh, yes," is the reply. And then all laugh.

One of the lookers-on pushes up and gets a glimpse within.

"What is it?" ask the other idlers.

He tells one quietly.

"What did he say?" ask the rest, one of another.

"He says they are not dead men, but new muskets" —

"Here, clear out!" cries an officer, and the loiterers

fall back and by and by straggle off.

The exiles? What became of them, do you ask? Why,

nothing; they were not troubled, but they never all came

together again. Said a chief-of-police to Major Shaughnessy

years afterward:

"Major, there was only one thing that kept your expedition

from succeeding — you were too sly about it. Had you come

out flat and said what you were doing, we'd never a-said a

word to you. But that little fellow gave us the wink, and

then we had to stop you."

And was no one punished? Alas! one was. Poor, pretty,

curly-headed traitorous Mazaro! He was drawn out of

Carondelet Canal — cold, dead! And when his wounds were

counted — they were just the number of the Café des Exilés'

children, less Galahad. But the mother — that is, the old

café — did not see it; she had gone up the night before in a

chariot of fire.

In the files of the old "Picayune" and "Price-Current" of

1837 may be seen the mention of Galahad Shaughnessy among

the merchants — "our enterprising and accomplished

fellow-townsman," and all that. But old M. D'Hemecourt's

name is cut in marble, and his citizenship is in "a city

whose maker and builder is God."

Only yesterday I dined with the Shaughnessys — fine old

couple and handsome. Their children sat about them and

entertained me most pleasantly. But

there isn't one can

tell a tale as their father can — 'twas he told me this one,

though here and there my enthusiasm may have taken

liberties. He knows the history of every old house in the

French Quarter; or, if he happens not to know a true one, he

can make one up as he goes along.

Notes

- Café.

In most countries refers to an establishment which focuses on serving coffee. The name derives from the French and Spanish word for the drink.

- Des Exilés.

Exiles. Forced separation from one's native country;

expulsion from one's home by the civil authority; banishment,

sometimes voluntary separation from one's native country.

- Creole.

The English term creole comes from French créole, which is cognate with the Spanish term criollo and Portuguese crioulo, all descending from the verb criar ("to breed" or "to raise"), ultimately from Latin creare ("to produce, create"). It refers to those born in a colony rather than the original colonists. The specific sense of the term was coined in the 16th and 17th century, during the great expansion in European maritime power and trade that led to the establishment of European colonies in other continents.

- Confidantes.

The confidant (feminine: confidante, same pronunciation) is a character in a story that the lead character (protagonist) confides in and trusts. Typically, these consist of the best friend, relative, doctor or boss.

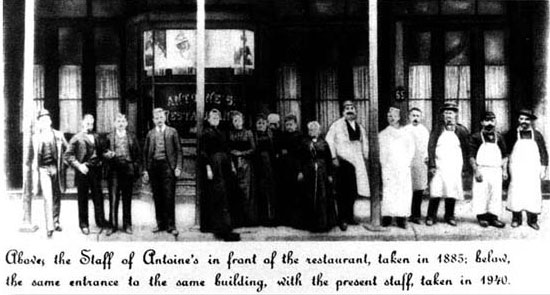

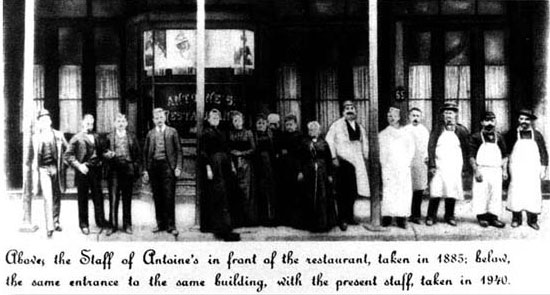

- Café des Réfugiés.

Now called Antoine's. Considered by many to be New Orleans' first eatery.

-

Picayune Tier.

The Picayune Tier, also know as Lugger Langing, was located by the fish market.

- Amigos.

Friend or comrade.

- Bueno.

Good.

- Oui, oui, mais!

Yes, yes, but.

Page Prepared by:

- Justin Bennett

- Michael Macaluso

- Himal Sashankar

- Sajan Shrestha

Source

Cable, George Washington.

Old Creole Days.. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1893. Internet Archive. Web. 27 Feb. 2012.

<http://archive. org/details/ oldcreoledays02 cablgoog>.

Anthology of Louisiana

Literature