T was in the Théatre St. Philippe (they had laid a

temporary floor over the parquette seats) in the city we

now call New Orleans, in the month of September, and

in the year

1803.

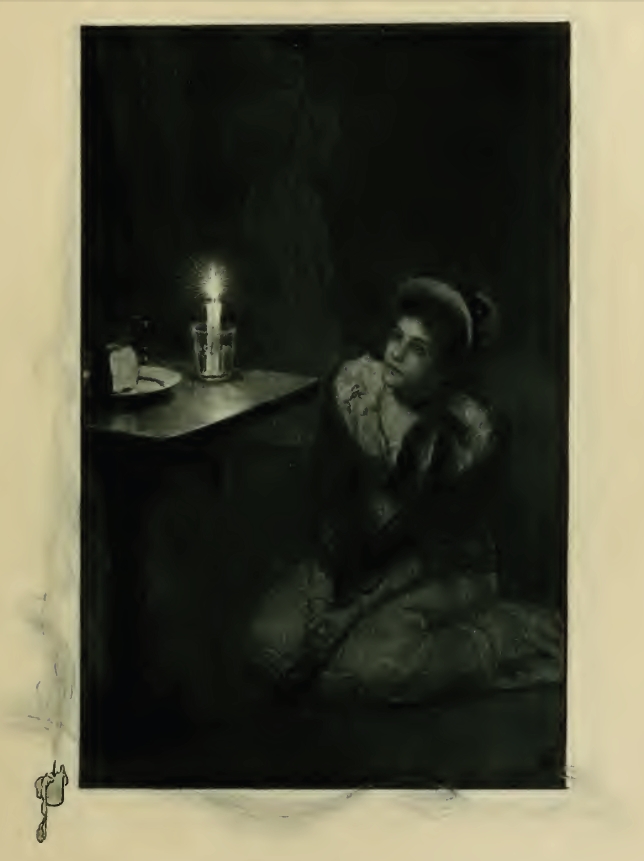

Under the twinkle of numberless

candles, and in a perfumed air thrilled with the wailing

ecstasy of violins, the little

Creole

capital's proudest and

best were offering up the first cool night of the languidly

departing summer to the divine

Terpsichore.

For

summer there, bear in mind, is a loitering gossip, that only

begins to talk of leaving when September rises to go.

It was like hustling her out, it is true, to give a select

bal masqué;

at such a very early — such an amusingly

early date; but it was fitting that something should be

done for the sick and the destitute; and why not this?

Everybody knows the Lord loveth a cheerful giver.

T was in the Théatre St. Philippe (they had laid a

temporary floor over the parquette seats) in the city we

now call New Orleans, in the month of September, and

in the year

1803.

Under the twinkle of numberless

candles, and in a perfumed air thrilled with the wailing

ecstasy of violins, the little

Creole

capital's proudest and

best were offering up the first cool night of the languidly

departing summer to the divine

Terpsichore.

For

summer there, bear in mind, is a loitering gossip, that only

begins to talk of leaving when September rises to go.

It was like hustling her out, it is true, to give a select

bal masqué;

at such a very early — such an amusingly

early date; but it was fitting that something should be

done for the sick and the destitute; and why not this?

Everybody knows the Lord loveth a cheerful giver.

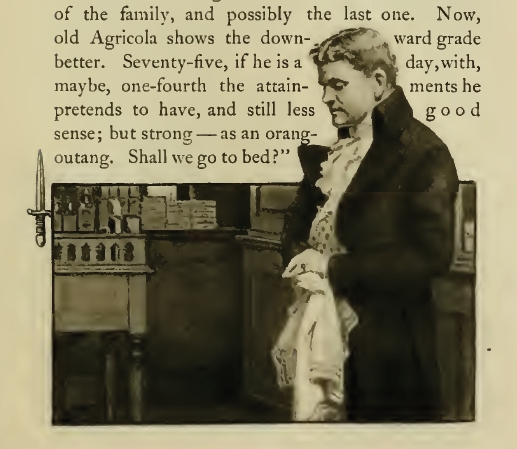

And so, to repeat, it was in the

Théatre St. Philippe

(the oldest, the first one), and, as may have been noticed,

in the year in which the First Consul of France gave

away Louisiana. Some might call it "sold." Old

Agricola Fusilier in the rumbling pomp of his natural

voice — for he had an hour ago forgotten that he was in

mask and domino — called it "gave away." Not that

he believed it had been done; for, look you, how could

it be? The pretended treaty contained, for instance,

no provision relative to the great family of

Brahmin Mandarin Fusilier de Grandissime.

It was evidently

spurious.

Being bumped against, he moved a step or two aside,

and was going on to denounce further the detestable

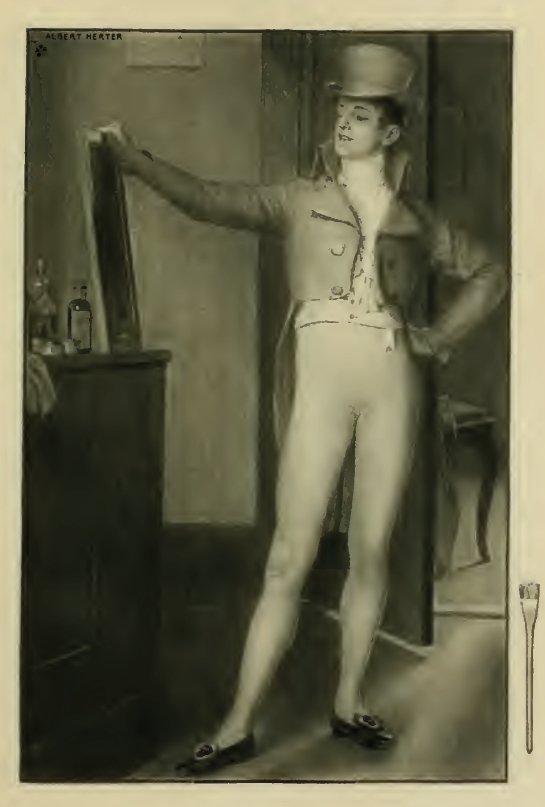

rumor, when a masker — one of four who had just

finished the contra-dance and were moving away in the

column of promenaders — brought him smartly around

with the salutation:

"Comment to yé, Citoyen

Agricola!"

"H-you young kitten!" said the old man in a growling

voice, and with the teased, half laugh of aged vanity

as he bent a baffled scrutiny at the back-turned face of

an ideal Indian Queen. It was not merely the

tutoiement

that struck him as saucy, but the further familiarity

of using the slave dialect. His French was unprovincial.

"H-the cool rascal!" he added laughingly, and only

half to himself; "get into the garb of your true sex, sir,

h-and I will guess who you are!"

But the Queen, in the same feigned voice as before,

retorted:

"Ah! mo piti fils, to pas connais to

zancestres?

Don't you know your ancestors, my little son!"

"H-the g-hods preserve us!" said Agricola, with a

pompous laugh muffled under his mask, "

the queen of the Tchoupitoulas

I proudly acknowledge, and my

great-grandfather,

Epaminondas Fusilier, lieutenant of

dragoons

under

Bienville;

but," — he laid his hand upon

his heart, and bowed to the other two figures, whose

smaller stature betrayed the gentler sex — "pardon me,

ladies, neither Monks nor

Filles à la

Cassette

grow on

our family tree."

The four maskers at once turned their glance upon

the old man in the domino; but if any retort was

intended it gave way as the violins burst into an agony of

laughter. The floor was immediately filled with waltzers

and the four figures disappeared.

"I wonder," murmured Agricola to himself, "if that

Dragoon can possibly be Honoré Grandissime."

Wherever those four maskers went there were cries of

delight: "Ho, ho, ho! see there! here! there! a group

of first colonists! One of

Iberville's

Dragoons! don't

you remember great-great-grandfather Fusilier's portrait

— the gilded casque and heron plumes? And that one

behind in the fawn-skin leggings and shirt of bird's

skins is an Indian Queen. As sure as sure can be, they

are intended for Epaminondas and his wife,

Lufki-Humma!" All, of course, in Louisiana French.

"But why, then, does he not walk with her?"

"Why, because, Simplicity, both of them are men,

while the little Monk on his arm is a lady, as you can

see, and so is the masque that has the arm of the Indian

Queen; look at their little hands."

In another part of the room the four were greeted

with, "Ha, ha, ha! well, that is magnificent! But see

that

Huguenotte

Girl on the Indian Queen's arm!

Isn't that fine! Ha, ha! she carries a little trunk.

She is a Fille à la Cassette!"

Two partners in a cotillion were speaking in an under

tone, behind a fan.

"And you think you know who it is?" asked one.

"Know?" replied the other. "Do I know I have a

head on my shoulders? If that Dragoon is not our

cousin Honoré Grandissime — well — "

"Honoré in mask? he is too sober-sided to do such

a thing."

"I tell you it is he! Listen. Yesterday I heard Doctor

Charlie Keene begging him to go, and telling him

there were two ladies, strangers, newly arrived in the city,

who would be there, and whom he wished him to meet.

Depend upon it the Dragoon is Honoré, Lufki-Humma

is Charlie Keene, and the Monk and the Huguenotte

are those two ladies."

But all this is an outside view; let us draw nearer and see

what chance may discover to us behind those four masks.

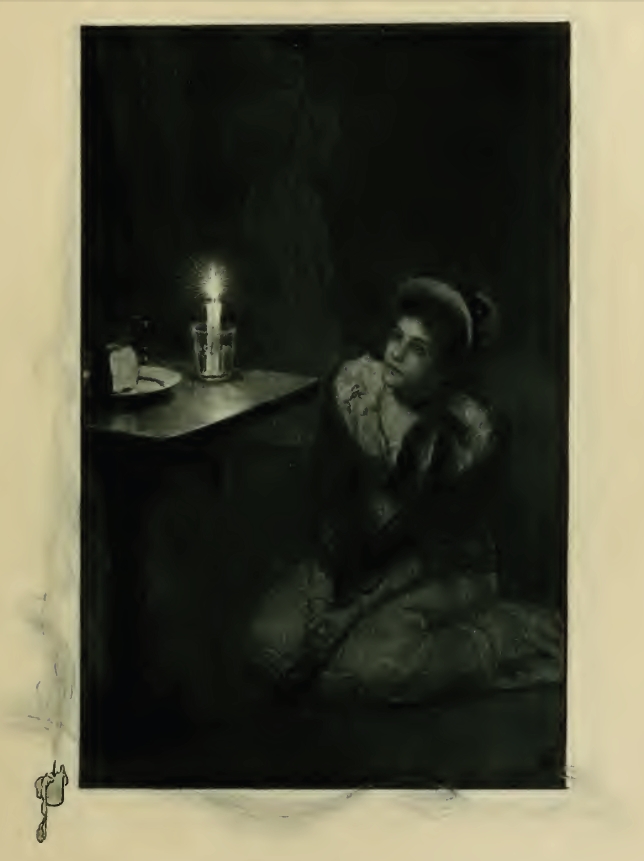

An hour has passed by. The dance goes on; hearts

are beating, wit is flashing, eyes encounter eyes with

the leveled lances of their beams, merriment and joy

and sudden bright surprises thrill the breast, voices are

throwing off disguise, and beauty's coy ear is bending

with a venturesome docility; here love is baffled, there

deceived, yonder takes prisoners and here surrenders.

The very air seems to breathe, to sigh, to laugh, while

the musicians, with disheveled locks, streaming brows

and furious bows, strike, draw, drive, scatter from the

anguished violins a never-ending rout of screaming

harmonies. But the Monk and the Huguenotte are not on

the floor. They are sitting where they have been left

by their two companions, in one of the boxes of the

theater, looking out upon the unwearied whirl and flash

of gauze and light and color.

"Oh,

chérie, chérie!"

murmured the little lady in the

Monk's disguise to her quieter companion, and speaking

in the soft dialect of old Louisiana, "now you get a

good idea of heaven!"

The Fille à la Cassette

replied with a sudden turn of

her masked face and a murmur of surprise and protest

against this impiety. A low, merry laugh came out of

the Monk's cowl, and the Huguenotte let her form sink

a little in her chair with a gentle sigh.

"Ah, for shame, tired!" softly laughed the other;

then suddenly, with her eyes fixed across the room, she

seized her companion's hand and pressed it tightly.

"Do you not see it?" she whispered eagerly, "just by

the door — the casque with the heron feathers. Ah,

Clotilde, I cannot believe he is one of those

Grandissimes!"

"Well," replied the Huguenotte, "Doctor Keene

says he is not."

Doctor Charlie Keene, speaking from under the

disguise of the Indian Queen, had indeed so said; but the

Recording Angel, whom we understand to be particular

about those things, had immediately made a memorandum

of it to the debit of Doctor Keene's account.

"If I had believed that it was he," continued the

whisperer, "I would have turned about and left him in the

midst of the contra-dance!"

Behind them sat unmasked a well-aged pair,

"bredouille,"

as they used to say of the wall-flowers, with

that look of blissful repose which marks the married and

established Creole. The lady in monk's attire turned

about in her chair and leaned back to laugh with these.

The passing maskers looked that way, with a certain

instinct that there was beauty under those two costumes.

As they did so, they saw the Fille à la

Cassette join in

this over-shoulder conversation. A moment later, they

saw the old gentleman protector and the Fille

à la

Cassette rising to the dance. And when presently the

distant passers took a final backward glance, that same

Lieutenant of Dragoons had returned and he and the

little Monk were once more upon the floor, waiting for

the music.

"But your late companion?" said the voice in the

cowl.

"My Indian Queen?" asked the Creole Epaminondas.

"Say, rather, your Medicine-Man," archly replied the

Monk.

"In these times," responded the Cavalier, "a

medicine-man

cannot dance long without professional interruption,

even when he dances for a charitable object.

He has been called to two relapsed patients." The

music struck up; the speaker addressed himself to the

dance; but the lady did not respond.

"Do dragoons ever moralize?" she asked.

"They do more," replied her partner; "sometimes,

when beauty's enjoyment of the ball is drawing toward

its twilight, they catch its pleasant melancholy, and

confess; will the good father sit in the confessional?"

The pair turned slowly about and moved toward the

box from which they had come, the lady remaining

silent; but just as they were entering she half withdrew

her arm from his, and, confronting him with a rich sparkle

of the eyes within the immobile mask of the monk, said:

"Why should the conscience of one poor little monk

carry all the frivolity of this ball? I have a right to

dance, if I wish. I give you my word, Monsieur

Dragoon, I dance only for the benefit of the sick and

the destitute. It is you men — you dragoons and others

who will not help them without a compensation in this

sort of nonsense. Why should we shrive you when you

ought to burn?"

"Then lead us to the altar," said the Dragoon.

"Pardon, sir," she retorted, her words entangled with

a musical, open-hearted laugh, "I am not going in that

direction." She cast her glance around the ball-room.

"As you say, it is the twilight of the ball; I am looking

for the evening star, — that is, my little Huguenotte."

"Then you are well mated."

"How?"

"For you are Aurora."

The lady gave a displeased start.

"Sir!"

"Pardon," said the Cavalier, "if by accident I have

hit upon your real name — "

She laughed again — a laugh which was as exultantly

joyous as it was high-bred.

"Ah, my name? Oh no, indeed!" (More work

for the Recording Angel.)

She turned to her protectress.

"Madame, I know you think we should be going

home."

The senior lady replied in amiable speech, but with

sleepy eyes, and the Monk began to lift and unfold a

wrapping. As the Cavalier drew it into his own possession,

and, agreeably to his gesture, the Monk and he

sat down side by side, he said, in a low tone:

"One more laugh before we part."

"A monk cannot laugh for nothing."

"I will pay for it."

"But with nothing to laugh at?" The thought of

laughing at nothing made her laugh a little on the spot.

"We will make something to laugh at," said the cavalier;

"we will unmask to each other, and when we find

each other first cousins, the laugh will come of itself."

"Ah! we will unmask? — no! I have no cousins. I

am certain we are strangers."

"Then we will laugh to think that I paid for the

disappointment."

Much more of this child-like badinage followed, and

by and by they came around again to the same last

statement. Another little laugh escaped from the cowl.

"You will pay? Let us see; how much will you give

to the sick and destitute?"

"To see who it is I am laughing with, I will give

whatever you ask."

"Two hundred and fifty dollars, cash, into the hands

of the managers!"

"A bargain!"

The Monk laughed, and her chaperon opened her

eyes and smiled apologetically. The Cavalier laughed,

too, and said:

"Good! That was the laugh; now the unmasking."

"And you positively will give the money to the

managers not later than to-morrow evening?"

"Not later. It shall be done without fail."

"Well, wait till I put on my wrappings; I must be

ready to run."

This delightful nonsense was interrupted by the return

of the Fille à la Cassette and

her aged, but sprightly,

escort, from a circuit of the floor. Madame again opened

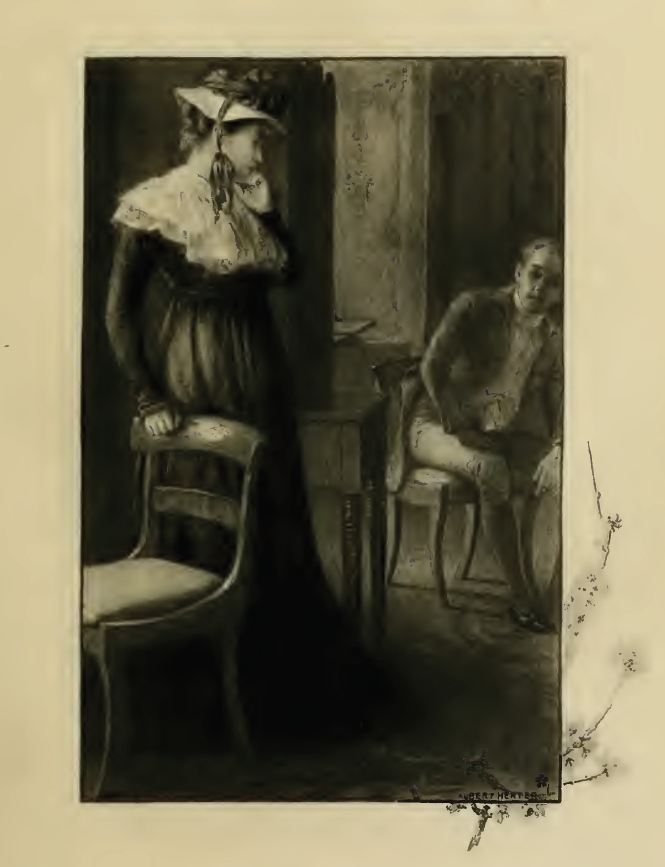

her eyes, and the four prepared to depart. The Dragoon

helped the Monk to fortify herself against the outer air.

She was ready before the others. There was a pause

a low laugh, a whispered "Now!" She looked upon

an unmasked, noble countenance, lifted her own mask a

little, and then a little more; and then shut it quickly

down again upon a face whose beauty was more than

even those fascinating graces had promised which

Honoré Grandissime had fitly named the Morning; but

it was a face he had never seen before.

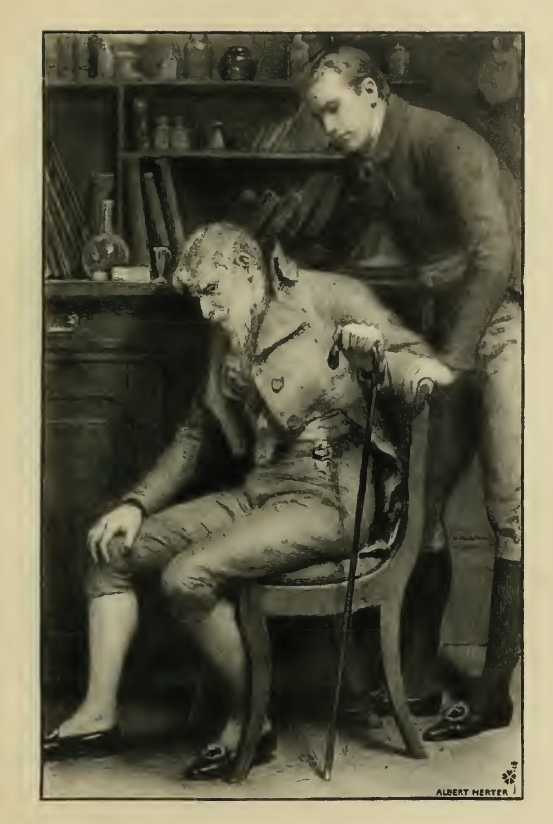

"She looked upon

an unmasked, noble countenance, lifted her own mask a

little, and then a little more; and then shut it quickly" . . .

"Hush!" she said,

"the enemies of religion are

watching us; the Huguenotte saw me. Adieu" — and

they were gone.

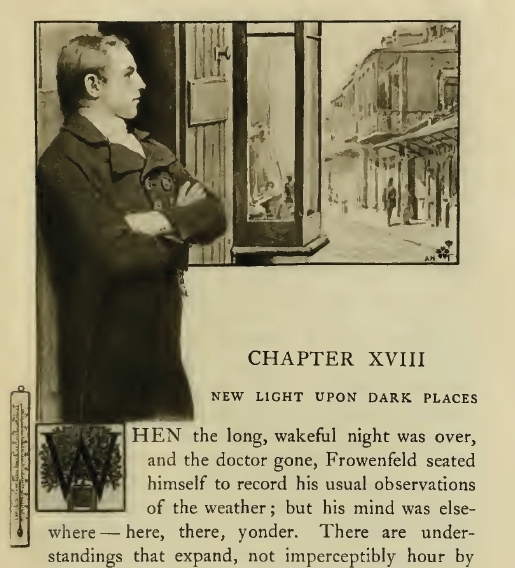

M. Honoré Grandissime turned on his heel and very

soon left the ball.

"Now, sir," thought he to himself, "we'll return to

our senses."

"Now I'll put my feathers on again," says the plucked

bird.

CHAPTER II.

THE FATE OF THE IMMIGRANT.

IT was just a fortnight after the ball, that one Joseph

Frowenfeld

opened his eyes upon Louisiana. He was

an American by birth, rearing and sentiment, yet German

enough through his parents, and the only son in a

family consisting of father, mother, self, and two sisters,

new-blown flowers of womanhood. It was an October

dawn, when, long wearied of the ocean, and with bright

anticipations of verdure, and fragrance, and tropical

gorgeousness, this simple-hearted family awoke to find

the bark that had borne them from their far northern

home already entering upon the ascent of the Mississippi.

We may easily imagine the grave group, as they came

up one by one from below, that morning of first

disappointment, and stood (with a whirligig of jubilant

mosquitoes spinning about each head) looking out across

the waste, and seeing the sky and the marsh meet in the

east, the north, and the west, and receiving with patient

silence the father's suggestion that the hills would, no

doubt, rise into view after a while.

"My children, we may turn this disappointment into

a lesson; if the good people of this country could speak

to us now, they might well ask us not to judge them or

their land upon one or two hasty glances, or by the

experiences of a few short days or weeks."

But no hills rose. However, by and by, they found

solace in the appearance of distant forest, and in the

afternoon they entered a land — but such a land! A

land hung in mourning, darkened by gigantic cypresses,

submerged; a land of reptiles, silence, shadow, decay.

"The captain told father, when we went to engage

passage, that New Orleans was on high land," said the

younger daughter, with a tremor in the voice, and

ignoring the remonstrative touch of her sister.

"On high land?" said the captain, turning from the

pilot; "well, so it is — higher than the swamp, but not

higher than the river," and he checked a broadening smile.

But the Frowenfelds were not a family to complain.

It was characteristic of them to recognize the bright as

well as the solemn virtues, and to keep each other

reminded of the duty of cheerfulness. A smile, starting

from the quiet elder sister, went around the group

directed against the abstracted and somewhat rueful

countenance of Joseph, whereat he turned with a better

face, and said that what the Creator had pronounced

very good they could hardly feel free to condemn. The

old father was still more stout of heart.

"These mosquitoes, children, are thought by some to

keep the air pure," he said.

"Better keep out of it after sunset," put in the captain.

After that day and night, the prospect grew less

repellent. A gradually matured conviction that New

Orleans would not be found standing on stilts in the

quagmire, enabled the eye to become educated to a

better appreciation of the solemn landscape. Nor was

the landscape always solemn. There were long openings,

now and then, to right and left, of emerald-green

savannah, with the dazzling blue of the Gulf far beyond,

evading a thousand white handed good-byes as the

funereal swamps slowly shut out again the horizon.

How sweet the soft breezes off the moist prairies! How

weird, how very near, the crimson and green and black

and yellow sunsets! How dream-like the land and the

great, whispering river! The profound stillness and

breadth reminded the old German, so he said, of that

early time when the

evenings and morningswere the first days of the half-built world.

The barking of a dog

in Fort Plaquemines seemed to come before its turn in

the panorama of creation — before the earth was ready

for the dog's master.

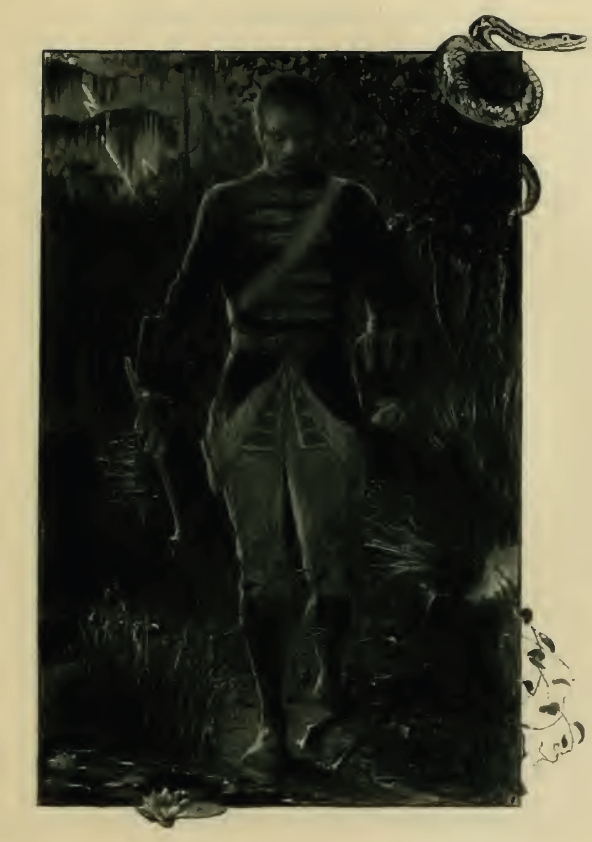

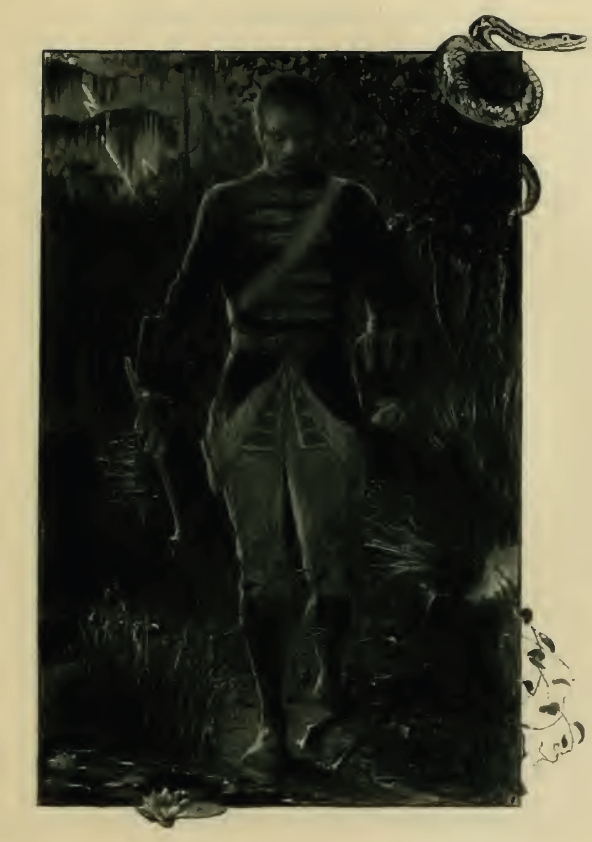

But he was assured that to live in those swamps was

not entirely impossible to man — "if one may call a

negro a man." Runaway slaves were not so rare in

them as one — a lost hunter, for example — might wish.

His informant was a new passenger, taken aboard at the

fort. He spoke English.

"Yes, sir! Didn' I had to run from Bras Coupé in

de haidge of de swamp be'ine de 'abitation of my cousin

Honoré, one time? You can hask 'oo you like!" (A

Creole always provides against incredulity.) At this

point he digressed a moment: "You know my cousin,

Honoré Grandissime, w'at give two hund' fifty dolla' to

de 'ospill laz mont'? An' juz because my cousin Honoré

give it, somebody helse give de semm. Fo' w'y don't he

give his nemm?"

The reason (which this person did not know) was that

the second donor was the first one over again, resolved

that the little unknown Monk should not know whom

she had baffled.

"Who was Bras Coupé?" the good German asked,

in French.

The stranger sat upon the capstan, and, in the shadow

of the cypress forest, where the vessel lay moored for

a change of wind, told in a patois difficult, but not

impossible, to understand, the story of a man who chose

rather to be hunted like a wild beast among those awful

labyrinths, than to be yoked and beaten like a tame one.

Joseph, drawing near as the story was coming to a close,

overheard the following English:

"Friend, if you dislike heated discussion, do not tell

that to my son."

The nights were strangely beautiful. The immigrants

almost consumed them on deck, the mother and

daughters attending in silent delight while the father

and son, facing south, rejoiced in learned recognition of

stars and constellations hitherto known to them only on

globes and charts.

"Yes, my dear son," said the father, in a moment of

ecstatic admiration, "wherever man may go, around this

globe — however uninviting his lateral surroundings may

be, the heavens are ever over his head, and I am glad to

find the stars your favorite objects of study."

So passed the time as the vessel, hour by hour, now

slowly pushed by the wind against the turbid current,

now warping along the fragrant precincts of orange or

magnolia groves or fields of sugar-cane, or moored by

night in the deep shade of mighty willow-jungles,

patiently crept toward the end of their pilgrimage; and

in the length of time which would at present be consumed

in making the whole journey from their Northern home

to their Southern goal, accomplished the distance of

ninety-eight miles, and found themselves before the

little, hybrid city of "Nouvelle Orleans." There was

the cathedral, and standing beside it, like Sancho beside

Don Quixote, the squat hall of the

Cabildo

with the

calabozo

in the rear. There were the forts, the military

bakery, the hospitals, the plaza, the Almonaster stores,

and the busy rue Toulouse; and, for the rest of the

town, a pleasant confusion of green tree-tops, red and

gray roofs, and glimpses of white or yellow wall, spreading

back a few hundred yards behind the cathedral, and

tapering into a single rank of gardened and belvedered

villas, that studded either horn of the river's crescent with

a style of home than which there is probably nothing in

the world more maternally home-like.

"And now," said the "captain," bidding the immigrants

good-by, "keep out of the sun and stay in after

dark; you're not 'acclimated,' as they call it, you know,

and the city is full of the

fever."

Such were the Frowenfelds. Out of such a mold and

into such a place came the young Américain, whom even

Agricola Fusilier as we shall see, by and by thought

worthy to be made an exception of, and honored with

his recognition.

The family rented a two-story brick house in the rue

Bienville, No. 17, it seems. The third day after, at

daybreak, Joseph called his father to his bedside to say

that he had had a chill, and was suffering such pains in

his head and back that he would like to lie quiet until

they passed off. The gentle father replied that it was

undoubtedly best to do so and preserved an outward

calm. He looked at his son's eyes; their pupils were

contracted to tiny beads. He felt his pulse and his

brow; there was no room for doubt; it was the dreaded

scourge — the fever. We say, sometimes, of hearts that

they sink like lead; it does not express the agony.

On the second day while the unsated fever was

running through every vein and artery, like soldiery through

the streets of a burning city, and far down in the caverns

of the body the poison was ransacking every palpitating

corner, the poor immigrant fell into a moment's sleep.

But what of that? The enemy that moment had

mounted to the brain. And then there happened to

Joseph an experience rare to the sufferer by this disease,

but not entirely unknown, — a delirium of mingled

pleasures and distresses. He seemed to awake somewhere

between heaven and earth reclining in a gorgeous

barge, which was draped in curtains of interwoven silver

and silk, cushioned with rich stuffs of every beautiful

dye, and perfumed ad nauseam with orange-leaf tea.

The crew was a single old negress, whose head was

wound about with a blue

Madras handkerchief,

and who

stood at the prow, and by a singular rotary motion,

rowed the barge with a tea-spoon. He could not get his

head out of the hot sun; and the barge went continually

round and round with a heavy, throbbing motion, in the

regular beat of which certain spirits of the air — one of

whom appeared to be a beautiful girl and another a

small, red-haired man, — confronted each other with the

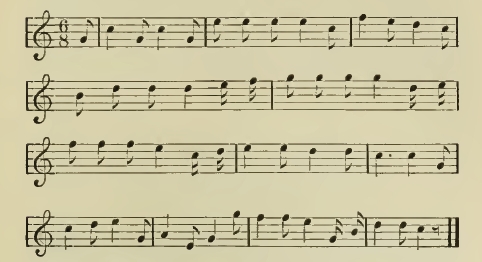

continual call and response:

"Keep the bedclothes on him and

the room shut tight,

keep the bedclothes on him and the room shut

tight," — "An' don' give 'im some watta, an' don' give

'im some watta."

During what lapse of time — whether moments or days

— this lasted, Joseph could not then know; but at last

these things faded away, and there came to him a positive

knowledge that he was on a sick-bed, where unless

something could be done for him he should be dead in

an hour. Then a spoon touched his lips, and a taste

of brandy and water went all through him; and when

he fell into sweet slumber and awoke, and found the

teaspoon ready at his lips again, he had to lift a little the

two hands lying before him on the coverlet to know that

they were his — they were so wasted and yellow. He

turned his eyes, and through the white gauze of the

mosquito-bar saw, for an instant, a strange and beautiful

young face; but the lids fell over his eyes, and when he

raised them again the blue-turbaned black nurse was

tucking the covering about his feet.

"Sister!"

No answer.

"Where is my mother?"

The negress shook her head.

He was too weak to speak again, but asked with his

eyes so persistently, and so pleadingly, that by and by

she gave him an audible answer. He tried hard to

understand it, but could not, it being in these words:

"Li pa' oulé vini 'ci — li pas capabe."

Thrice a day for three days more, came a little man

with a large head surrounded by short, red curls and

with small freckles in a fine skin, and sat down by the

bed with a word of good cheer and the air of a

commander. At length they had something like an

extended conversation.

"So you concluded not to die, eh? Yes, I'm the

doctor — Doctor Keene. A young lady? What young

lady? No, sir, there has been no young lady here.

You're mistaken. Vagary of your fever. There has

been no one here but this black girl and me. No, my

dear fellow, your father and mother can't see you yet; you

don't want them to catch the fever, do you? Good-bye.

Do as your nurse tells you, and next week you may

raise your head and shoulders a little; but if you don't

mind her you'll have a

back-set,

and the devil himself

wouldn't engage to cure you."

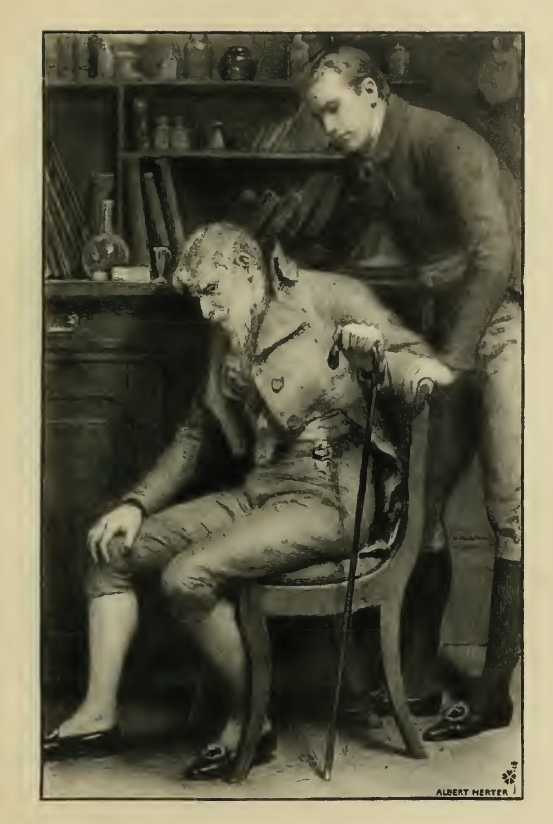

The patient had been sitting up a little at a time for

several days, when at length the doctor came to pay a

final call, "as a matter of form:" but, after a few

pleasantries, he drew his chair up gravely, and, in a

tender tone — need we say it? He had come to tell

Joseph that his father, mother, sisters, all, were gone on

a second — a longer — voyage, to shores where there

could be no disappointments and no fevers, forever.

"And, Frowenfeld," he said, at the end of their long

and painful talk, "if there is any blame attached to not

letting you go with them, I think I can take part of it;

but if you ever want a friend, — one who is courteous to

strangers and ill-mannered only to those he likes, — you

can call for Charlie Keene. I'll drop in to see you, anyhow,

from time to time, till you get stronger. I have

taken a heap of trouble to keep you alive, and if you

should relapse now and give us the slip, it would be a

deal of good physic wasted; so keep in the house."

The polite neighbors who lifted their cocked hats to

Joseph as he spent a slow convalescence just within his

open door, were not bound to know how or when he

might have suffered. There were no "Howards" or

"Y.M.C.A's" in those days; no "Peabody Reliefs."

Even had the neighbors chosen to take cognizance of

those bereavements, they were not so unusual as to fix

upon him any extraordinary interest as an object of

sight; and he was beginning most distressfully to realize

that

"great solitude"

which the philosopher attributes

to towns, when matters took a decided turn.

CHAPTER III.

"AND WHO IS MY NEIGHBOR?"

WE say matters took a turn; or, better, that Frowenfeld's

interest in affairs received a new life. This had its

beginning in Doctor Keene's making himself specially

entertaining in an old-family-history way, with a view

to keeping his patient within-doors for a safe period.

He had conceived a great liking for Frowenfeld, and

often, of an afternoon, would drift in to challenge him

to a game of chess — a game, by the way, for which

neither of them cared a farthing. The immigrant had

learned its moves to gratify his father, and the doctor —

the truth is, the doctor had never quite learned them;

but he was one of those men who cannot easily consent

to acknowledge a mere affection for one, least of

all one of their own sex. It may safely be supposed,

then, that the board often displayed an arrangement

of pieces that would have bewildered

Morphy

himself.

"By the by, Frowenfeld," he said one evening, after

the one preliminary move with which he invariably

opened his game, "you haven't made the acquaintance

of your pretty neighbors next door."

Frowenfeld knew of no specially pretty neighbors

next door on either side — had noticed no ladies.

"Well, I will take you in to see them sometime."

The doctor laughed a little, rubbing his face and his

thin, red curls with one hand, as he laughed.

The convalescent wondered what there could be to

laugh at.

"Who are they?" he inquired.

"Their name is De Grapion — oh, De Grapion, says

I! their name is Nancanou. They are, without exception,

the finest women — the brightest, the best, and the

bravest — that I know in New Orleans." The doctor

resumed a cigar which lay against the edge of the

chessboard, found it extinguished, and proceeded to relight

it. "Best blood of the Province; good as the Grandissimes.

Blood is a great thing here, in certain odd ways,"

he went on. "Very curious sometimes." He stooped

to the floor, where his coat had fallen, and took his

handkerchief from a breast-pocket. "At a grand mask ball

about two months ago, where I had a bewilderingly fine

time with those ladies, the proudest old turkey in the

theater was an old fellow whose Indian blood shows in

his very behavior, and yet — ha, ha! I saw that same old

man, at a

quadroon ball

a few years ago, walk up to the

handsomest, best dressed man in the house, a man with

a skin whiter than his own, — a perfect gentleman as to

looks and manners, — and without a word slap him in the

face."

"You laugh?" asked Frowenfeld.

"Laugh? Why shouldn't I? The fellow had no

business there. Those balls are not given to quadroon

males, my friend. He was lucky to get out alive, and

that was about all he did."

"They are right!" the doctor persisted, in response

to Frowenfeld's puzzled look. "The people here have

got to be particular. However, that is not what we

were talking about. Quadroon balls are not to be

mentioned in connection. Those ladies — " He addressed

himself to the resuscitation of his cigar. "Singular people

in this country," he resumed; but his cigar would not

revive. He was a poor story-teller. To Frowenfeld —

as it would have been to any one, except a Creole or

the most thoroughly Creoleized Américain — his

narrative, when it was done, was little more than a thick mist

of strange names, places and events; yet there shone a

light of romance upon it that filled it with color and

populated it with phantoms. Frowenfeld's interest rose —

was allured into this mist — and there was left befogged.

As a physician, Doctor Keene thus accomplished his

end, — the mental diversion of his late patient, — for in

the midst of the mist Frowenfeld encountered and grappled

a problem of human life in Creole type, the possible

correlations of whose quantities we shall presently find

him revolving in a studious and sympathetic mind, as

the poet of to-day ponders the

The quantities in that

problem were the ancestral — the

maternal — roots of those two rival and hostile families

whose descendants — some brave, others fair — we find

unwittingly thrown together at the ball, and with whom

we are shortly to have the honor of an unmasked

acquaintance.

CHAPTER IV.

FAMILY TREES.

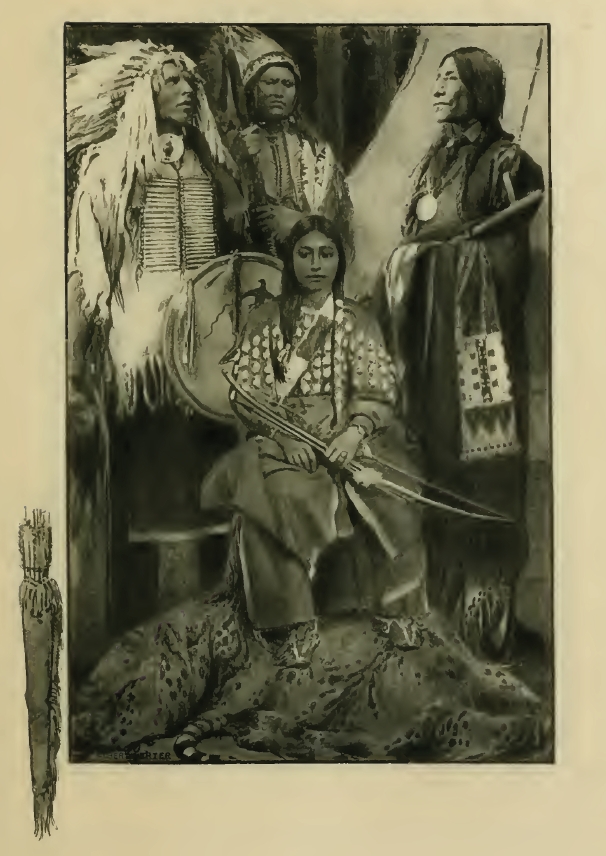

IN the year 1673, and in the royal hovel of a Tchoupitoulas

village not far removed from that "Buffalo's

Grazing-ground," now better known as New Orleans,

was born Lufki-Humma, otherwise Red Clay. The

mother of Red Clay was a princess by birth as well as

by marriage. For the father, with that devotion to his

people's interests, presumably common to rulers, had

ten moons before ventured northward into the territory

of the proud and exclusive Natchez nation, and had so

prevailed with — so outsmoked — their "Great Sun," as

to find himself, as he finally knocked the ashes from his

successful

calumet,

possessor of a wife whose pedigree

included a long line of royal mothers, — fathers being of

little account in Natchez heraldry, extending back beyond

the Mexican origin of her nation, and disappearing

only in the efullgence of her great original, the orb

of day himself. As to Red Clay's paternal ancestry, we

must content ourselves with the fact that the father was

not only the diplomate

we have already found him, but

a chief of considerable eminence; that is to say, of seven

feet stature.

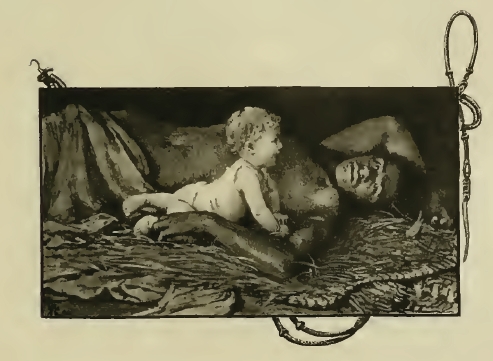

It scarce need be said than when Lufki-Humma was

born, the mother arose at once from her couch of skins,

herself bore the infant to the neighboring bayou and

washed it — not for singularity, nor for independence, nor

for vainglory, but only as one of the heart curdling

conventionalities which made up the experience of that most

pitiful of holy things, an Indian mother.

Outside the lodge door sat and continued to sit, as she

passed out, her master or husband. His interest in the

trivialities of the moment may be summed up in this,

that he was as fully prepared as some men are in more

civilized times and places to hold his queen to strict account

for the sex of her offspring. Girls for the Natchez,

if they preferred them, but the chief of the Tchoupitoulas

wanted a son. She returned from the water

came near, sank upon her knees! laid the infant at his

feet, and lo! a daughter.

Then she fell forward heavily upon her face. It may

have been muscular exhaustion, it may have been the

mere wind of her hasty-tempered matrimonial master's

stone hatchet as it whiffed by her skull; an inquest now

would be too great an irony; but something blew out

her "vile candle."

Among the squaws who came to offer the accustomed

funeral howlings, and seize mementoes from the deceased

lady's scant leavings, was one who had in her

own palmetto hut an empty cradle scarcely cold, and

therefore a necessity at her breast, if not a place in her

heart, for the unfortunate Lufki-Humma; and thus it

was that this little waif came to be tossed, a droll hypothesis

of flesh, blood, nerve and brain, into the hands of

wild nature with carte blanche as to the disposal of it.

And now, since this was Agricola's most boasted ancestor

— since it appears the darkness of her cheek had no

effect to make him less white, or qualify his right to

smite the fairest and most distant descendant of an

African on the face,

and since this proud station and right

could not have sprung from the squalid surroundings of

her birth, let us for a moment contemplate these crude

materials.

As for the flesh, it was indeed only some of that "one

flesh" of which we all are made; but the blood — to go

into finer distinctions — the blood, as distinguished from

the milk of her Alibamon foster-mother, was the blood

of the royal caste of the great Toltec mother-race, which

before it yielded its Mexican splendors to the conquering

Aztec, throned the jeweled and gold-laden Inca in

the South, and sent the sacred fire of its temples into

the North by the hand of the Natchez. For it is a short

way of expressing the truth concerning Red Clay's tissues

to say she had the blood of her mother and the

nerve of her father, the nerve of the true North American

Indian, and had it in its finest strength.

As to her infantine bones, they were such as needed

not to fail of straightness in the limbs, compactness in

the body, smallness in hands and feet, and exceeding

symmetry and comeliness throughout. Possibly between

the two sides of the occipital profile there may have been

an Incæan tendency to inequality; but if by any good

fortune her impressible little cranium should escape the

cradle-straps, the shapeliness that nature loves would

soon appear. And this very fortune befell her. Her

father's detestation of an infant that had not consulted

his wishes as to sex, prompted a verbal decree which,

among other prohibitions, forbade her skull the distortions

that ambitious and fashionable Indian mothers delighted

to produce upon their offspring.

And as to her brain: what can we say? The casket

in which Nature sealed that brain, and in which Nature's

great step-sister Death, finally laid it away, has never

fallen into the delighted fingers — and the remarkable

fineness of its texture will never kindle admiration in

the triumphant eyes — of those whose scientific hunger

drives them to dig for crania Americana; nor yet will

all their learned excavatings ever draw forth one of those

pale souvenirs of mortality with walls of shapelier contour

or more delicate fineness, or an interior of more

admirable spaciousness, than the fair council-chamber

under whose dome the mind of Lufki-Humma used, about

two centuries ago, to sit in frequent conclave with high

thoughts.

"I have these facts," it was Agricola Fusilier's habit

to say, "by family tradition; but you know, sir,

h-tradition is much more authentic than history!"

Listening Crane, the tribal medicine-man, one day

stepped softly into the lodge of the giant chief, sat down

opposite him on a mat of plaited rushes, accepted a

lighted calumet, and, after the silence of a decent hour,

broken at length by the warrior's intimation that "the

ear of Raging Buffalo listened for the voice of his brother,"

said, in effect, that if that ear would turn toward the

village play-ground, it would catch a murmur like the

pleasing sound of bees among the blossoms of the

catalpa, albeit the catalpa was now dropping her leaves, for

it was the moon of turkeys. No, it was the repressed

laughter of squaws, wallowing with their young ones

about the village pole, wondering at the Natchez-Tchoupitoulas

child, whose eye was the eye of the panther, and

whose words were the words of an aged chief in council.

There was more added; we record only enough to

indicate the direction of Listening Crane's aim. The

eye of Raging Buffalo was opened to see a vision: the

daughter of the Natchez sitting in majesty, clothed in

many-colored robes of shining feathers crossed and

recrossed with girdles of serpent-skins and of wampum,

her feet in quilled and painted moccasins, her head

under a glory of plumes, the carpet of buffalo-robes

about her throne covered with the trophies of conquest,

and the atmosphere of her lodge blue with the smoke of

ambassadors' calumets; and this extravagant dream the

capricious chief at once resolved should eventually

become reality. "Let her be taken to the village temple,"

he said to his prime-minister, "and be fed by

warriors on the flesh of wolves."

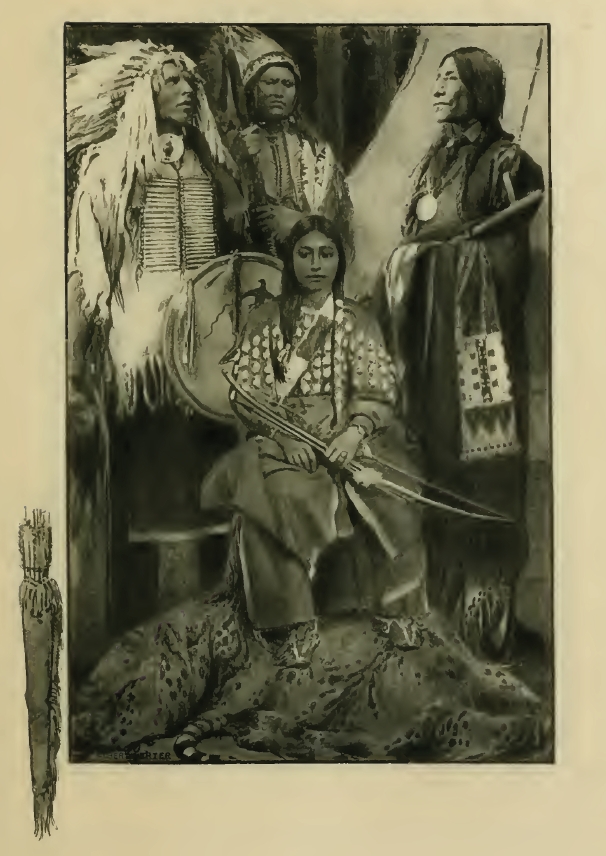

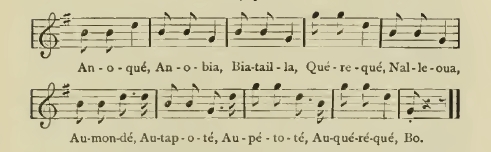

"The daughter of the Natchez sitting in majesty, clothed in

many-colored robes of shining feathers crossed and

recrossed with girdles of serpent-skins and of wampum" . . .

The Listening Crane was a patient man; he was the

"man that waits" of the old French proverb; all things

came to him. He had waited for an opportunity to

change his brother's mind, and it had come. Again, he

waited for him to die; and, like Methuselah and others,

he died. He had heard of a race more powerful than

the Natchez — a white race; he waited for them; and

when the year 1682 saw a humble "black gown"

dragging and splashing his way, with La Salle and Tonti,

through the swamps of Louisiana, holding forth the

crucifix and backed by French carbines and Mohican

tomahawks, among the marvels of that wilderness was

found this: a child of nine sitting, and — with some

unostentatious aid from her medicine-man — ruling;

queen of her tribe and high-priestess of their temple.

Fortified by the acumen and self-collected ambition of

Listening Crane, confirmed in her regal title by the

white man's

Manitou

through the medium of the "black

gown," and inheriting her father's fear-compelling frown,

she ruled with majesty and wisdom, sometimes a decreer

of bloody justice, sometimes an Amazonian counselor of

warriors, and at all times — year after year, until she had

reached the perfect womanhood of twenty-six — a virgin

queen.

On the 11th of March, 1699, two overbold young

Frenchmen of M. D'Iberville's little exploring party

tossed guns on shoulder, and ventured away from their

canoes on the bank of the Mississippi into the wilderness.

Two men they were whom an explorer would have been

justified in hoarding up, rather than in letting out at such

risks; a pair to lean on, noble and strong. They hunted,

killed nothing, were overtaken by rain, then by night,

hunger, alarm, despair.

And when they had lain down to die, and had only

succeeded in falling asleep, the Diana of the Tchoupitoulas,

ranging the magnolia groves with bow and quiver,

came upon them in all the poetry of their hope-forsaken

strength and beauty, and fell sick of love. We say not

whether with Zephyr Grandissime or Epaminondas

Fusilier; that, for the time, being, was her secret.

The two captives were made guests. Listening Crane

rejoiced in them as representatives of the great gift-making

race, and indulged himself in a dream of pipe-smoking,

orations, treaties, presents and alliances, finding its

climax in the marriage of his virgin queen to the king of

France, and unvaryingly tending to the swiftly increasing

aggrandizement of Listening Crane. They sat down

to bear's meat,

sagamite,

and beans. The queen sat

down with them, clothed in her entire wardrobe: vest

of swan's skin, with facings of purple and green from the

neck of the mallard; petticoat of plaited hair, with

embroideries of quills; leggings of fawn-skin; garters

of wampum; black and green serpent-skin moccasins,

that rested on pelts of tiger-cat and buffalo; armlets of

gars'

scales, necklaces of bears' claws and alligators'

teeth,

plaited tresses, plumes of raven and flamingo, wing of

the pink curlew, and odors of bay and sassafras. Young

men danced before them, blowing upon reeds, hooting,

yelling rattling beans in gourds and touching hands and

feet. One day was like another, and the nights were

made brilliant with flambeau dances and processions.

Some days later M. D'Iberville's canoe fleet, returning

down the river found and took from the shore the

two men, whom they had given up for dead, and with

them, by her own request, the abdicating queen, who

left behind her a crowd of weeping and howling squaws

and warriors. Three canoes that put off in their wake,

at a word from her, turned back; but one old man

leaped into the water, swam after them a little way, and

then unexpectedly sank. It was that cautious wader

but inexperienced swimmer, the Listening Crane.

When the expedition reached Biloxi, there were two

suitors for the hand of Agricola's great ancestress.

Neither of them was Zephyr Grandissime. (Ah! the

strong heads of those Grandissimes.)

They threw dice for her. Demosthenes De Grapion

— he who, tradition says, first hoisted the flag of France

over the little fort — seemed to think he ought to have a

chance, and being accorded it, cast an astonishingly

high number; but Epaminondas cast a number higher

by one (which Demosthenes never could quite understand),

and got a wife who had loved him from first

sight.

Thus, while the pilgrim fathers of the Mississippi

Delta with Gallic recklessness were taking wives and

moot-wives from the ill specimens of three races, arose

with the church's benediction, the royal house of the

Fusiliers in Louisiana. But the true, main Grandissime

stock, on which the Fusiliers did early, ever, and yet do,

love to marry, has kept itself lily-white ever since France

has loved lilies — as to marriage, that is; as to less

responsible entanglements, why, of course —

After a little, the disappointed Demosthenes, with due

ecclesiastical sanction, also took a most excellent wife,

from the first cargo of House of Correction girls. Her

biography, too, is as short as Methuselah's, or shorter;

she died. Zephyr Grandissime married, still later, a

lady of rank, a widow without children, sent from France

to Biloxi under a

lettre de cachet.

Demosthenes De

Grapion, himself an only son, left but one son, who also

left but one. Yet they were prone to early marriages.

So also were the Grandissimes, or, as the name is

signed in all the old notarial papers, the Brahmin

Mandarin de Grandissimes. That was one twig that kept

their many-stranded family line so free from knots and

kinks. Once the leisurely Zephyr gave them a start,

generation followed generation with a rapidity that kept

the competing De Grapions incessantly exasperated, and

new-made Grandissime fathers continually throwing

themselves into the fond arms and upon the proud necks

of congratulatory grandsires. Verily it seemed as though

their family tree was a fig-tree; you could not look for

blossoms on it, but there, instead, was the fruit full of

seed. And with all their speed they were for the most

part fine of stature, strong of limb and fair of face. The

old nobility of their stock, including particularly the

unnamed blood of her of the lettre

de cachet, showed

forth in a gracefulness of carriage, that almost identified

a De Grandissime wherever you saw him, and in a

transparency of flesh and classic beauty of feature, that

made their daughters extra-marriageable in a land and

day which was bearing a wide reproach for a male

celibacy not of the pious sort.

In a flock of Grandissimes might always be seen a

Fusilier or two; fierce-eyed, strong-beaked, dark,

heavy-taloned birds, who, if they could not sing, were of rich

plumage, arid could talk and bite, and strike, and keep

up a ruffled crest and a self-exalting bad humor. They

early learned one favorite cry, with which they greeted

all strangers, crying the louder the more the endeavor

was made to appease them: "Invaders! Invaders!"

There was a real pathos in the contrast offered to this

family line by that other which sprang up as slenderly

as a stalk of wild oats from the loins of Demosthenes De

Grapion. A lone son following a lone son, and he

another — it was sad to contemplate, in that colonial

beginning of days, three generations of good, Gallic

blood tripping jocundly along in attenuated Indian file.

It made it no less pathetic to see that they were

brilliant, gallant, much-loved, early epauletted fellows,

who did not let twenty-one catch them without wives

sealed with the authentic wedding kiss, nor allow

twenty-two to find them without an heir. But they had a sad

aptness for dying young. It was altogether supposable

that they would have spread out broadly in the land;

but they were such inveterate duelists, such brave

Indian-fighters, such adventurous swamp-rangers, and such

lively free-livers, that, however numerously their half-kin

may have been scattered about in an unacknowledged

way, the avowed name of De Grapion had become

less and less frequent in lists where leading citizens

subscribed their signatures, and was not to be seen in

the list of managers of the late ball.

It is not at all certain that so hot a blood would not

have boiled away entirely before the night of the bal

masqué, but for an event which led to the union of that

blood with a stream equally clear and ruddy, but of a

milder vintage. This event fell out some fifty-two years

after that cast of the dice which made the princess

Lufki-Humma the mother of all the Fusiliers and of none

of the De Grapions. Clotilde, the Casket-Girl, the little

maid who would not marry, was one of an heroic sort,

worth — the De Grapions maintained — whole swampfuls

of Indian queens. And yet the portrait of this great

ancestress, which served as a pattern to one who, at the

ball, personated the long-deceased heroine en masque,

is hopelessly lost in some garret. Those Creoles have

such a shocking way of filing their family relics and

records in rat-holes.

One fact alone remains to be stated: that the De

Grapions, try to spurn it as they would, never could

quite suppress a hard feeling in the face of the record,

that from the two young men who, when lost in the

horrors of Louisiana's swamps, had been esteemed

as good as dead, and particularly from him who married

at his leisure, — from Zephyr de Grandissime, — sprang

there so many as the sands of the Mississippi

innumerable.

CHAPTER V.

A MAIDEN WHO WILL NOT MARRY.

MIDWAY between the times of Lufki-Humma and

those of her proud descendant, Agricola Fusilier,

fifty-two years lying on either side, were the days of

Pierre

Rigaut, the magnificent, the "Grand Marquis," the

Governor, De Vaudreuil.

He was the Solomon of

Louisiana. For splendor, however, not for wisdom.

Those were the gala days of license, extravagance and

pomp. He made paper money to be as the leaves of the

forest for multitude; it was nothing accounted of in the

days of the Grand Marquis. For

Louis Quinze was king.

Clotilde, orphan of a murdered Huguenot, was one of

sixty, the last royal allotment to Louisiana, of imported

wives. The king's agents had inveigled her away from

France with fair stories: "They will give you a quiet

home with some lady of the colony. Have to marry?

— not unless it pleases you. The king himself pays your

passage and gives you a casket of clothes. Think of

that these times, fillette; and passage free, withal, to —

the garden of Eden, as you may call it — what more, say

you, can a poor girl want? Without doubt, too, like a

model colonist, you will accept a good husband and have

a great many beautiful children, who will say with pride,

'Me, I am no

House-of-Correction-girl

stock; my

mother' — or 'grandmother,' as the case may be — 'was

fille à la cassette!' "

The sixty were landed in New Orleans and given into

the care of the Ursuline nuns; and, before many days

had elapsed, fifty-nine soldiers of the king were well

wived and ready to settle upon their riparian land-grants

The residuum in the nuns' hands was one stiff-necked

little heretic, named, in part, Clotilde. They bore with

her for sixty days, and then complained to the Grand

Marquis. But the Grand Marquis, with all his pomp,

was gracious and kind-hearted, and loved his ease almost

as much as his marchioness loved money. He bade

them try her another month. They did so, and then

returned with her;

she would neither marry nor pray to Mary.

Here is the way they talked in New Orleans in those

days. If you care to understand why Louisiana has

grown up so out of joint, note the tone of those who

governed her in the middle of the last century:

"What, my child," the Grand Marquis said, "you a

fille à la cassette? France, for shame! Come here by

my side. Will you take a little advice from an old

soldier? It is in one word — submit. Whatever is

inevitable, submit to it. If you want to live easy and

sleep easy, do as other people do- — submit. Consider

submission in the present case; how easy, how comfortable,

and how little it amounts to! A little hearing of

mass, a little telling of beads, a little crossing of one's

self — what is that? One need not believe in them.

Don't shake your head. Take my example; look at

me; all these things go in at this ear and out at this.

Do king or clergy trouble me? Not at all. For how

does the king in these matters of religion? I shall not

even tell you, he is such a bad boy. Do you not know

that all the noblesse, and all the savants, and especially

all the archbishops and cardinals, — all, in a word, but

such silly little chicks as yourself, — have found out that

this religious business is a joke? Actually a joke, every

whit; except, to be sure, this heresy phase; that is a

joke they cannot take. Now, I wish you well, pretty

child; so if you — eh? — truly, my pet, I fear we shall

have to call you unreasonable. Stop; they can spare

me here a moment; I will take you to the Marquise:

she is in the next room. * * * Behold," said he, as he

entered the presence of his marchioness, "the little maid

who will not marry!"

The Marquise was as cold and hard-hearted as the

Marquis was loose and kind; but we need not recount

the slow tortures of the fille à la cassette's second verbal

temptation. The colony had to have soldiers, she was

given to understand, and the soldiers must have wives.

"Why, I am a soldier's wife, myself!" said the gorgeously

attired lady, laying her hand upon the governor-general's

epaulet. She explained, further, that he was

rather soft-hearted, while she was a business woman

also that the royal commissary's rolls did not comprehend

such a thing as a spinster, and — incidentally — that

living by principle was rather out of fashion in the

Province just then.

After she had offered much torment of this sort, a

definite notion seemed to take her; she turned her lord

by a touch of the elbow, and exchanged two or three

businesslike whispers with him at a window overlooking

the Levee.

"Fillette," she said, returning, "you are going to live

on the sea-coast. I am sending an aged lady there to

gather the wax of the wild myrtle. This good soldier

of mine buys it for our king at twelve livres the pound.

Do you not know that women can make money? The

place is not safe; but there are no safe places in

Louisiana. There are no nuns to trouble you there;

only a few Indians and soldiers. You and Madame will

live together, quite to yourselves, and can pray as you

like."

"And not marry a soldier," said the Grand Marquis.

"No," said the lady, "not if you can gather enough

myrtle-berries to afford me a profit and you a living."

It was some thirty leagues or more eastward to the

country of the Biloxis, a beautiful land of low, evergreen

hills looking out across the pine-covered sand-keys of

Mississippi Sound to the Gulf of Mexico. The northern

shore of Biloxi Bay was rich in candleberry-myrtle. In

Clotilde's day, though Biloxi was no longer the capital of

the Mississippi Valley, the fort which D'Iberville had

built in 1699, and the first timber of which is said to have

been lifted by Zephyr Grandissime at one end and

Epaminondas Fusilier at the other, was still there,

making brave against the possible advent of

corsairs,

with a few old

culverines

and one wooden mortar.

And did the orphan, in despite of Indians and soldiers

and wilderness settle down here and make a moderate

fortune? Alas, she never gathered a berry! When she

— with the aged lady, her appointed companion in exile,

the young commandant of the fort, in whose pinnace

they had come, and two or three French sailors and

Canadians — stepped out upon the white sand of Biloxi

beach, she was bound with invisible fetters hand and foot,

by that

Olympian rogue of a boy,

who likes no better

prey than a little maiden who thinks she will never marry.

The officer's name was De Grapion — Georges De

Grapion. The Marquis gave him a choice grant of land

on that part of the Mississippi river "coast" known as

the

Cannes Brulées.

"Of course you know where Cannes Brulées is, don't

you?" asked Doctor Keene of Joseph Frowenfeld.

"Yes," said Joseph, with a twinge of reminiscence that

recalled the study of Louisiana on paper with his father

and sisters.

There Georges De Grapion settled, with the laudable

determination to make a fresh start against the

mortifyingly numerous Grandissimes.

"My father's policy was every way bad," he said to

his spouse; "it is useless, and probably wrong, this

trying to thin them out by duels; we will try another

plan. Thank you," he added, as she handed his coat

back to him, with the shoulder-straps cut off. In

pursuance of the new plan, Madame De Grapion, — the

precious little heroine! — before the myrtles offered

another crop of berries, bore him a boy not much smaller

(saith tradition) than herself.

Only one thing qualified the father's elation. On that

very day Numa Grandissime (Brahmin-Mandarin de

Grandissime), a mere child, received from Governor De

Vaudreuil a cadetship.

"Never mind, Messieurs Grandissime, go on with

your tricks; we shall see! Ha! we shall see!"

"We shall see what?" asked a remote relative of that

family. "Will Monsieur be so good as to explain

himself?"

Bang! bang!

Alas, Madame De Grapion!

It may be recorded that no affair of honor in

Louisiana ever left a braver little widow. When Joseph

and his doctor pretended to play chess together, but

little more than a half-century had elapsed since the fille à

la cassette stood before the Grand Marquis and refused to

wed. Yet she had been long gone into the skies, leaving

a worthy example behind her in twenty years of beautiful

widowhood. Her son, the heir and resident of the

plantation at Cannes Brulées, at the age of — they do say

— eighteen, had married a blithe and pretty lady of

Franco-Spanish extraction, and, after a fair length of

life divided between campaigning under the brilliant

young

Galvez

and raising unremunerative indigo crops,

had lately lain down to sleep, leaving only two descendants

— females — how shall we describe them? — a Monk

and a Fille à la Cassette. It was very hard to have to go

leaving his family name snuffed out and certain

Grandissime-ward grievances burning.

"There are so many Grandissimes," said the weary-eyed

Frowenfeld, "I cannot distinguish between — I can

scarcely count them."

"Well, now," said the doctor, "let me tell you, don't

try. They can't do it themselves. Take them in the

mass — as you would shrimps."

CHAPTER VI.

LOST OPPORTUNITIES.

THE little doctor tipped his chair back against the

mall, drew up his knees, and laughed whimperingly in

his freckled hands.

"I had to do some prodigious lying at that ball. I

didn't dare let the De Grapion ladies know they were in

company with a Grandissime."

"I thought you said their name was Nancanou."

"Well, certainly — De Grapion-Nancanou. You see,

that is one of their charms; one is a widow, the other is

her daughter, and both as young and beautiful as

Hebe.

Ask Honoré Grandissime; he has seen the little widow;

but then he don't know who she is. He will not ask

me, and I will not tell him. Oh yes; it is about eighteen

years now since old De Grapion — elegant, high-stepping

old fellow — married her, then only sixteen

years of age, to young Nancanou, an indigo-planter on

the

Fausse Rivière

— the old bend, you know, behind

Pointe Coupée. The young couple went there to live.

I have been told they had one of the prettiest places in

Louisiana. He was a man of cultivated tastes, educated

in Paris, spoke English, was handsome (convivial, of

course), and of

perfectly pure blood.

But there was one

thing old De Grapion overlooked; he and his son-in-law

were the last of their names. In Lousiana

a man

needs kinfolk. He ought to have married his daughter

into a strong house. They say that Numa Grandissime

(Honoré's father) and he had patched up a peace

between the two families that included even old Agricola,

and that he could have married her to a Grandissime.

However, he is supposed to have known what he was

about.

"A matter of business called young Nancanou to

New Orleans. He had no friends here; he was a

Creole, but what part of his life had not been spent on

his plantation he had passed in Europe. He could not

leave his young girl of a wife alone in that exiled sort of

plantation life, so he brought her and the child (a girl)

down with him as far as to her father's place, left them

there, and came on to the city alone.

"Now, what does the old man do but give him a letter

of introduction to old Agricole Fusilier! (His name

is Agricola, but we shorten it to Agricole.) It seems

that old De Grapion and Agricole had had the indiscretion

to scrape up a mutually complimentary correspondence.

And to Agricole the young man went.

"They became intimate at once, drank together,

danced with the quadroons together, and got into as

much mischief in three days as I ever did in a fortnight.

So affairs went on until by an by they were gambling

together. One night they were at the Piety Club, playing

hard, and the planter lost his last quarti. He became

desperate, and did a thing I have known more

than one planter to do: wrote his pledge for every arpent

of his land and every slave on it, and staked that.

Agricole refused to play. 'You shall play,' said Nancanou,

and when the game was ended he said: 'Monsieur

Agricola Fusilier, you cheated.' You see? Just as I

have frequently been tempted to remark to my friend,

Mr. Frowenfeld.

"But, Frowenfeld, you must know, withal the Creoles

are such gamblers, they never cheat; they play absolutely

fair. So Agricole had to challenge the planter.

He could not be blamed for that; there was no choice —

oh, now, Frowenfeld, keep quiet! I tell you there was

no choice. And the fellow was no coward. He sent

Agricole a clear title to the real estate and slaves, —

lacking only the wife's signature, — accepted the challenge

and fell dead at the first fire.

"Stop, now, and let me finish. Agricole sat down

and wrote to the widow that he did not wish to deprive

her of her home, and that if she would state in writing

her belief that the stakes had been won fairly, he would

give back the whole estate, slaves and all; but that if

she would not, he should feel compelled to retain it in

vindication of his honor. Now wasn't that drawing a

fine point?" The doctor laughed according to his

habit, with his face down in his hands. "You see, he

wanted to stand before all creation — the Creator did not

make so much difference — in the most exquisitely proper

light; so he puts the laws of humanity under his feet,

and anoints himself from head to foot with Creole

punctilio."

"Did she sign the paper?" asked Joseph.

"She? Wait till you know her! No, indeed; she

had the true scorn. She and her father sent down

another and a better title. Creole-like, they managed to

bestir themselves to that extent and there they stopped.

"And the airs with which they did it! They kept all

their rage to themselves, and sent the polite word, that

they were not acquainted with the merits of the case,

that they were not disposed to make the long and arduous

trip to the city and back, and that if M. Fusilier de

Grandissime thought he could find any pleasure or profit

in owning the place, he was welcome; that the widow

of his late friend was not disposed to live on it, but

would remain with her father at the paternal home at

Cannes Brulées.

"Did you ever hear of a more perfect specimen of

Creole pride? That is the way with all of them. Show

me any Creole, or any number of Creoles, in any sort of

contest, and right down at the foundation of it all, I will

find you this same preposterous, apathetic, fantastic,

suicidal pride. It is as lethargic and ferocious as an alligator.

That is why the Creole almost always is (or thinks he is)

on the defensive. See these De Grapions' haughty good

manners to old Agricole; yet there wasn't a Grandissime

in Louisiana who could have set foot on the De Grapion

lands but at the risk of his life.

"But I will finish the story; and here is the really

sad part. Not many months ago, old De Grapion —

'old,' said I; they don't grow old; I call him old — a

few months ago he died. He must have left everything

smothered in debt; for, like his race, he had stuck to

indigo because his father planted it, and it is a crop that

has lost money steadily for years and years. His daughter

and granddaughter were left like babes in the wood;

and, to crown their disasters, have now made the grave

mistake of coming to the city, where they find they

haven't a friend — not one, sir! They called me in to

prescribe for a trivial indisposition, shortly after their

arrival; and I tell you, Frowenfeld, it made me shiver

to see two such beautiful women in such a town as this

without a male protector, and even" — the doctor

lowered his voice — "without adequate support. The

mother says they are perfectly comfortable; tells the

old couple so who took them to the ball, and whose

little girl is their embroidery scholar; but you cannot

believe a Creole on that subject, and I don't believe her.

Would you like to make their acquaintance?"

Frowenfeld hesitated, disliking to say no to his friend,

and then shook his head.

"After a while — at least not now, sir, if you please."

The doctor made a gesture of disappointment.

"Um-hum," he said grumly — "the only man in New

Orleans I would honor with an invitation! — but all right;

I'll go alone."

He laughed a little at himself, and left Frowenfeld, if

ever he should desire it, to make the acquaintance of his

pretty neighbors as best he could.

CHAPTER VII.

WAS IT HONORÉ GRANDISSIME?

A CREOLE gentleman, on horseback one morning

with some practical object in view, — drainage, possibly,

— had got what he sought, — the evidence of his own

eyes on certain points, — and now moved quietly across

some old fields toward the town, where more absorbing

interests awaited him in the Rue Toulouse; for this

Creole gentleman was a merchant, and because he would

presently find himself among the appointments and restraints

of the counting-room, he heartily gave himself up,

for the moment, to the surrounding influences of nature.

It was late in November; but the air was mild and

the grass and foliage green and dewy. Wild flowers

bloomed plentifully and in all directions; the bushes

were hung, and often covered, with vines of sprightly

green, sprinkled thickly with smart-looking little worthless

berries, whose sparkling complacency the combined

contempt of man, beast and bird could not dim. The

call of the field-lark came continually out of the grass,

where now and then could be seen his yellow breast;

the orchard oriole was executing his fantasias in every

tree; a covey of partridges ran across the path close under

the horse's feet, and stopped to look back almost within

reach of the riding-whip; clouds of starlings, in their

odd, irresolute way, rose from the high bulrushes and

settled again, without discernible cause; little wandering

companies of sparrows undulated from hedge to

hedge; a great rabbit-hawk sat alone in the top of a

lofty pecan-tree; that petted rowdy, the mocking-bird,

dropped down into the path to offer fight to the horse,

and, failing in that, flew up again and drove a crow into

ignominious retirement beyond the plain; from a place

of flags and reeds a white crane shot upward, turned,

and then, with the slow and stately beat peculiar to her

wing, sped away until, against the tallest cypress of the

distant forest, she became a tiny white speck on its

black, and suddenly disappeared, like one flake of snow.

The scene was altogether such as to fill any hearty

soul with impulses of genial friendliness and gentle

candor; such a scene as will sometimes prepare a man

of the world, upon the least direct incentive, to throw

open the windows of his private thought with a freedom

which the atmosphere of no counting-room or drawing-room

tends to induce.

The young merchant — he was young — felt this.

Moreover, the matter of business which had brought him

out had responded to his inquiring eye with a somewhat

golden radiance; and your true man of business — he

who has reached that elevated pitch of serene, good-natured

reserve which is of the high art of his calling —

is never so generous with his pennyworths of thought as

when newly in possession of some little secret worth

many pounds.

By and by the behavior of the horse indicated the

near presence of a stranger; and the next moment the

rider drew rein under an immense live-oak where there

was a bit of paling about some graves, and raised his hat.

"Good-morning, sir.' But for the silent r's, his

pronunciation was exact, yet evidently an acquired one.

While he spoke his salutation in English, he was thinkin

French: "Without doubt, this rather oversized,

bare headed, interrupted-looking convalescent who stands

before me, wondering how I should know in what

language to address him, is Joseph Frowenfeld, of whom

Doctor Keene has had so much to say to me. A good

face — unsophisticated, but intelligent, mettlesome and

honest. He will make his mark; it will probably be a

white one; I will subscribe to the adventure."

"You will excuse me, sir?" he asked after a pause,

dismounting, and noticing, as he did so, that Frowenfeld's

knees showed recent contact with the turf; "I

have, myself, some interest in two of these graves,

sir, as I suppose — you will pardon my freedom — you

have in the other four."

He approached the old but newly whitened paling,

which encircled the tree's trunk as well as the six graves

about it. There was in his face and manner a sort of

impersonal human kindness, well calculated to engage

a diffident and sensitive stranger, standing in dread of

gratuitous benevolence or pity.

"Yes, sir," said the convalescent, and ceased; but the

other leaned against the palings in an attitude of attention,

and he felt induced to add: "I have buried here

my father, mother and two sisters," — he had expected

to continue in an unemotional tone; but a deep respiration

usurped the place of speech. He stooped quickly

to pick up his hat, and, as he rose again and looked into

his listener's face, the respectful, unobtrusive sympathy

there expressed went directly to his heart.

"Victims of the fever," said the Creole with great

gravity. "How did that happen?"

As Frowenfeld, after a moment's hesitation, began to

speak, the stranger let go the bridle of his horse and sat

down upon the turf. Joseph appreciated the courtesy

and sat down, too; and thus the ice was broken.

The immigrant told his story; he was young — often

younger than his years — and his listener several years

his senior; but the Creole, true to his blood, was able at

any time to make himself as young as need be, and

possessed the rare magic of drawing one's confidence

without seeming to do more than merely pay attention.

It followed that the story was told in full detail, including

grateful acknowledgment of the goodness of an unknown

friend, who had granted this burial-place on condition

that he should not be sought out for the purpose of

thanking him.

So a considerable time passed by, in which acquaintance

grew with delightful rapidity.

"What will you do now?" asked the stranger, when

a short silence had followed the conclusion of the story.

"I hardly know. I am taken somewhat by surprise.

I have not chosen a definite course in life — as yet. I

have been a general student, but have not prepared

myself for any profession; I am not sure what I shall

be."

A certain energy in the immigrant's face half redeemed

this child-like speech. Yet the Creole's lips, as he

opened them to reply, betrayed amusement; so he

hastened to say:

"I appreciate your position, Mr. Frowenfeld, — excuse

me, I believe you said that was your father's name. And

yet," — the shadow of an amused smile lurked another

instant about a corner of his mouth, — "if you would

understand me kindly I would say, take care — "

What little blood the convalescent had rushed violently

to his face, and the Creole added:

"I do not insinuate you would willingly be idle. I

think I know what you want. You want to make up

your mind now what you will do, and at your leisure

what you will be, eh? To be, it seems to me," he said

in summing up, — "that to be is not so necessary as to

do, eh? or am I wrong?"

"No, sir," replied Joseph, still red, "I was feeling

that just now. I will do the first thing that offers; I

can dig."

The Creole shrugged and pouted.

"And be called a dos brilée — a 'burnt-back.' "

"But" began the immigrant, with overmuch

warmth.

The other interrupted him, shaking his head slowly,

and smiling as he spoke.

"Mr. Frowenfeld, it is of no use to talk; you may

hold in contempt the Creole scorn of toil — just as I do,

myself, but in theory, my-de'-seh, not too much in practice.

You cannot afford to be entirely different to the

community in which you live; is that not so?"

"A friend of mine," said Frowenfeld, "has told me I

must 'compromise.' "

"You must get

acclimated,"

responded the Creole;

"not in body only, that you have done; but in mind —