Anthology

of Louisiana Literature

George Washington Cable.

Madame Delphine.

CONTENTS.

MADAME DELPHINE.

CHAPTER I.

AN OLD HOUSE.

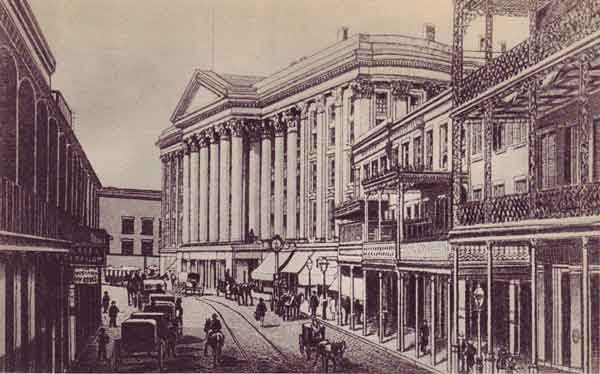

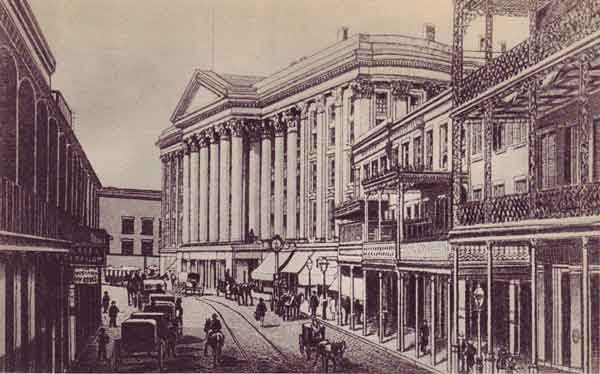

A few steps from the St. Charles Hotel, in New Orleans, brings you to

and across Canal street, the central avenue of the city, and to that

corner where the flower-women sit at the inner and outer edges of the

arcaded sidewalk, and make the air sweet with their fragrant

merchandise. The crowd — and if it is near the time of the carnival it

will be great — will follow Canal street.

|

|

St. Charles Hotel in the 1850’s.

|

But you turn, instead, into the quiet, narrow way which a lover of

Creole antiquity, in fondness for a romantic past, is still prone to

call the Rue Royale. You will pass a few restaurants, a few auction

rooms, a few furniture warehouses, and will hardly realize that you

have left behind you the activity and clatter of a city of merchants

before you find yourself in a region of architectural decrepitude, where

an ancient and foreign-seeming domestic life, in second stories,

overhangs the ruins of a former commercial prosperity, and upon

everything has settled down a long Sabbath of decay. The vehicles in the

street are few in number, and are merely passing through; the stores are

shrunken into shops; you see here and there, like a patch of bright

mould, the stall of that significant fungus, the Chinaman. Many great

doors are shut and clamped and grown gray with cobweb; many street

windows are nailed up; half the balconies are begrimed and rust-eaten,

and many of the humid arches and alleys which characterize the older

Franco-Spanish piles of stuccoed brick betray a squalor almost oriental.

Yet beauty lingers here. To say nothing of the picturesque, sometimes

you get sight of comfort, sometimes of opulence, through the unlatched

wicket in some

porte-cochère

— red-painted brick pavement, foliage of

dark palm or pale banana, marble or granite masonry and blooming

parterres; or through a chink between some pair of heavy batten

window-shutters, opened with an almost reptile wariness, your eye gets a

glimpse of lace and brocade upholstery, silver and bronze, and much

similar rich antiquity.

The faces of the inmates are in keeping; of the passengers in the street

a sad proportion are dingy and shabby; but just when these are putting

you off your guard, there will pass you a woman — more likely two or

three — of patrician beauty.

Now, if you will go far enough down this old street, you will see, as

you approach its intersection with ——. Names in that region elude one

like ghosts.

However, as you begin to find the way a trifle more open, you will not

fail to notice on the right-hand side, about midway of the square, a

small, low, brick house of a story and a half, set out upon the

sidewalk, as weather-beaten and mute as an aged beggar fallen asleep.

Its corrugated roof of dull red tiles, sloping down toward you with an

inward curve, is overgrown with weeds, and in the fall of the year is

gay with the yellow plumes of the golden-rod. You can almost touch with

your cane the low edge of the broad, overhanging eaves. The batten

shutters at door and window, with hinges like those of a postern, are

shut with a grip that makes one's knuckles and nails feel lacerated.

Save in the brick-work itself there is not a cranny. You would say the

house has the lock-jaw. There are two doors, and to each a single

chipped and battered marble step. Continuing on down the sidewalk, on a

line with the house, is a garden masked from view by a high, close

board-fence. You may see the tops of its fruit-trees — pomegranate,

peach, banana, fig, pear, and particularly one large orange, close by

the fence, that must be very old.

The residents over the narrow way, who live in a three-story house,

originally of much pretension, but from whose front door hard times have

removed almost all vestiges of paint, will tell you:

“Yass, de ’ouse is in’abit; ’tis live in.”

And this is likely to be all the information you get — not that they

would not tell, but they cannot grasp the idea that you wish to

know — until, possibly, just as you are turning to depart, your

informant, in a single word and with the most evident non-appreciation

of its value, drops the simple key to the whole matter:

“Dey’s quadroons.”

He may then be aroused to mention the better appearance of the place in

former years, when the houses of this region generally stood farther

apart, and that garden comprised the whole square.

Here dwelt, sixty years ago and more, one Delphine Carraze; or, as she

was commonly designated by the few who knew her, Madame Delphine. That

she owned her home, and that it had been given her by the then deceased

companion of her days of beauty, were facts so generally admitted as to

be, even as far back as that sixty years ago, no longer a subject of

gossip. She was never pointed out by the denizens of the quarter as a

character, nor her house as a “feature.” It would have passed all Creole

powers of guessing to divine what you could find worthy of inquiry

concerning a retired quadroon woman; and not the least puzzled of all

would have been the timid and restive Madame Delphine herself.

During the first quarter of the present century, the free quadroon caste

of New Orleans was in its golden age. Earlier generations — sprung, upon

the one hand, from the merry gallants of a French colonial military

service which had grown gross by affiliation with Spanish-American

frontier life, and, upon the other hand, from comely Ethiopians culled

out of the less negroidal types of African live goods, and bought at the

ship’s side with vestiges of quills and cowries and copper wire still in

their head-dresses, — these earlier generations, with scars of battle or

private rencontre still on the fathers, and of servitude on the

manumitted mothers, afforded a mere hint of the splendor that was to

result from a survival of the fairest through seventy-five years devoted

to the elimination of the black pigment and the cultivation of hyperian

excellence and nymphean grace and beauty. Nor, if we turn to the

present, is the evidence much stronger which is offered by the

gens de couleur

whom you may see in the quadroon quarter this afternoon, with

“Ichabod" legible on their murky foreheads through a vain smearing of

toilet powder, dragging their chairs down to the narrow gate-way of

their close-fenced gardens, and staring shrinkingly at you as you pass,

like a nest of yellow kittens.

But as the present century was in its second and third decades, the

quadroones

(for we must contrive a feminine spelling to define the

strict limits of the caste as then established) came forth in splendor.

Old travellers spare no terms to tell their praises, their faultlessness

of feature, their perfection of form, their varied styles of

beauty, — for there were even pure Caucasian blondes among them, — their

fascinating manners, their sparkling vivacity, their chaste and pretty

wit, their grace in the dance, their modest propriety, their taste and

elegance in dress. In the gentlest and most poetic sense they were

indeed the sirens of this land, where it seemed “always afternoon” — a

momentary triumph of an Arcadian over a Christian civilization, so

beautiful and so seductive that it became the subject of special

chapters by writers of the day more original than correct as social

philosophers.

The balls that were got up for them by the male

sang-pur

were to that

day what the carnival is to the present. Society balls given the same

nights proved failures through the coincidence. The magnates of

government, — municipal, state, federal, — those of the army, of the

learned professions and of the clubs, — in short, the white male

aristocracy in everything save the ecclesiastical desk, — were there.

Tickets were high-priced to insure the exclusion of the vulgar. No

distinguished stranger was allowed to miss them. They were beautiful!

They were clad in silken extenuations from the throat to the feet, and

wore, withal, a pathos in their charm that gave them a family likeness

to innocence.

Madame Delphine, were you not a stranger, could have told you all about

it; though hardly, I suppose, without tears.

But at the time of which we would speak (1821-22) her day of splendor

was set, and her husband — let us call him so for her sake — was long

dead. He was an American, and, if we take her word for it, a man of

noble heart and extremely handsome; but this is knowledge which we can

do without.

Even in those days the house was always shut, and Madame Delphine’s

chief occupation and end in life seemed to be to keep well locked up

in-doors. She was an excellent person, the neighbors said, — a very

worthy person; and they were, may be, nearer correct than they knew.

They rarely saw her save when she went to or returned from church; a

small, rather tired-looking, dark quadroone of very good features and a

gentle thoughtfulness of expression which it would take long to

describe: call it a widow’s look.

In speaking of Madame Delphine’s house, mention should have been made of

a gate in the fence on the Royal-street sidewalk. It is gone now, and

was out of use then, being fastened once for all by an iron staple

clasping the cross-bar and driven into the post.

Which leads us to speak of another person.

He was one of those men that might be any age, — thirty, forty,

forty-five; there was no telling from his face what was years and what

was only weather. His countenance was of a grave and quiet, but also

luminous, sort, which was instantly admired and ever afterward

remembered, as was also the fineness of his hair and the blueness of his

eyes. Those pronounced him youngest who scrutinized his face the

closest. But waiving the discussion of age, he was odd, though not with

the oddness that he who reared him had striven to produce.

He had not been brought up by mother or father. He had lost both in

infancy, and had fallen to the care of a rugged old military grandpa of

the colonial school, whose unceasing endeavor had been to make “his

boy” as savage and ferocious a holder of unimpeachable social rank as it

became a pure-blooded French Creole to be who could trace his pedigree

back to the god Mars.

“Remember, my boy,” was the adjuration received by him as regularly as

his waking cup of black coffee, “that none of your family line ever kept

the laws of any government or creed.” And if it was well that he should

bear this in mind, it was well to reiterate it persistently, for, from

the nurse’s arms, the boy wore a look, not of docility so much as of

gentle, judicial benevolence. The domestics of the old man’s house

used to shed tears of laughter to see that look on the face of a babe.

His rude guardian addressed himself to the modification of this facial

expression; it had not enough of majesty in it, for instance, or of

large dare-deviltry; but with care these could be made to come.

And, true enough, at twenty-one (in Ursin Lemaitre), the labors of his

grandfather were an apparent success. He was not rugged, nor was he

loud-spoken, as his venerable trainer would have liked to present him to

society; but he was as serenely terrible as a well-aimed rifle, and the

old man looked upon his results with pride. He had cultivated him up to

that pitch where he scorned to practice any vice, or any virtue, that

did not include the principle of self-assertion. A few touches only were

wanting here and there to achieve perfection, when suddenly the old man

died. Yet it was his proud satisfaction, before he finally lay down, to

see Ursin a favored companion and the peer, both in courtesy and pride,

of those polished gentlemen famous in history, the brothers Lafitte.

The two Lafittes were, at the time young Lemaitre reached his majority

(say 1808 or 1812), only merchant blacksmiths, so to speak, a term

intended to convey the idea of blacksmiths who never soiled their hands,

who were men of capital, stood a little higher than the clergy, and

moved in society among its autocrats. But they were full of

possibilities, men of action, and men, too, of thought, with already a

pronounced disbelief in the custom-house. In these days of big carnivals

they would have been patented as the dukes of Little Manchac and

Barataria.

Young Ursin Lemaitre (in full the name was Lemaitre-Vignevielle) had not

only the hearty friendship of these good people, but also a natural turn

for accounts; and as his two friends were looking about them with an

enterprising eye, it easily resulted that he presently connected himself

with the blacksmithing profession. Not exactly at the forge in the

Lafittes’ famous smithy, among the African Samsons, who, with their

shining black bodies bared to the waist, made the Rue St. Pierre ring

with the stroke of their hammers; but as a — there was no occasion to

mince the word in those days — smuggler.

Smuggler — patriot — where was the difference? Beyond the ken of a

community to which the enforcement of the revenue laws had long been

merely so much out of every man’s pocket and dish, into the

all-devouring treasury of Spain. At this date they had come under a

kinder yoke, and to a treasury that at least echoed when the customs

were dropped into it; but the change was still new. What could a man be

more than Capitaine Lemaitre was — the soul of honor, the pink of

courtesy, with the courage of the lion, and the magnanimity of the

elephant; frank — the very exchequer of truth! Nay, go higher still: his

paper was good in Toulouse street. To the gossips in the gaming-clubs he

was the culminating proof that smuggling was one of the sublimer

virtues.

Years went by. Events transpired which have their place in history.

Under a government which the community by and by saw was conducted in

their interest, smuggling began to lose its respectability and to grow

disreputable, hazardous, and debased. In certain onslaughts made upon

them by officers of the law, some of the smugglers became murderers. The

business became unprofitable for a time until the enterprising

Lafittes — thinkers — bethought them of a corrective — “privateering.”

Thereupon the United States Government set a price upon their heads.

Later yet it became known that these outlawed pirates had been offered

money and rank by Great Britain if they would join her standard, then

hovering about the water-approaches to their native city, and that they

had spurned the bribe; wherefore their heads were ruled out of the

market, and, meeting and treating with Andrew Jackson, they were

received as lovers of their country, and as compatriots fought in the

battle of New Orleans at the head of their fearless men, and — here

tradition takes up the tale — were never seen afterward.

Capitaine Lemaitre was not among the killed or wounded, but he was among

the missing.

The roundest and happiest-looking priest in the city of New Orleans was

a little man fondly known among his people as Père Jerome. He was a

Creole and a member of one of the city’s leading families. His dwelling

was a little frame cottage, standing on high pillars just inside a tall,

close fence, and reached by a narrow outdoor stair from the green batten

gate. It was well surrounded by crape myrtles, and communicated behind

by a descending stair and a plank-walk with the rear entrance of the

chapel over whose worshippers he daily spread his hands in benediction.

The name of the street — ah! there is where light is wanting. Save the

Cathedral and the Ursulines, there is very little of record concerning

churches at that time, though they were springing up here and there.

All there is certainty of is that Père Jerome’s frame chapel was some

little new-born “down-town” thing, that may have survived the passage of

years, or may have escaped

“Paxton’s Directory”

“so as by fire.” His

parlor was dingy and carpetless; one could smell distinctly there the

vow of poverty. His bedchamber was bare and clean, and the bed in it

narrow and hard; but between the two was a dining-room that would tempt

a laugh to the lips of any who looked in. The table was small, but

stout, and all the furniture of the room substantial, made of fine wood,

and carved just enough to give the notion of wrinkling pleasantry. His

mother’s and sister’s doing, Père Jerome would explain; they would not

permit this apartment — or department — to suffer. Therein, as well as in

the parlor, there was odor, but of a more epicurean sort, that explained

interestingly the Père Jerome’s rotundity and rosy smile.

In this room, and about this miniature round table, used sometimes to

sit with Père Jerome two friends to whom he was deeply attached — one,

Evariste Varrillat, a playmate from early childhood, now his

brother-in-law; the other, Jean Thompson, a companion from youngest

manhood, and both, like the little priest himself, the regretful

rememberers of a fourth comrade who was a comrade no more. Like Père

Jerome, they had come, through years, to the thick of life’s

conflicts, — the priest’s brother-in-law a physician, the other an

attorney, and brother-in-law to the lonely wanderer, — yet they loved to

huddle around this small board, and be boys again in heart while men in

mind. Neither one nor another was leader. In earlier days they had

always yielded to him who no longer met with them a certain

chieftainship, and they still thought of him and talked of him, and, in

their conjectures, groped after him, as one of whom they continued to

expect greater things than of themselves.

They sat one day drawn thus close together, sipping and theorizing,

speculating upon the nature of things in an easy, bold, sophomoric way,

the conversation for the most part being in French, the native tongue of

the doctor and priest, and spoken with facility by Jean Thompson the

lawyer, who was half Américain; but running sometimes into English and

sometimes into mild laughter. Mention had been made of the absentee.

Père Jerome advanced an idea something like this:

“It is impossible for any finite mind to fix the degree of criminality

of any human act or of any human life. The Infinite One alone can know

how much of our sin is chargeable to us, and how much to our brothers or

our fathers. We all participate in one another’s sins. There is a

community of responsibility attaching to every misdeed. No human since

Adam — nay, nor Adam himself — ever sinned entirely to himself. And so I

never am called upon to contemplate a crime or a criminal but I feel my

conscience pointing at me as one of the accessories.”

“In a word,” said Evariste Varrillat, the physician, “you think we are

partly to blame for the omission of many of your Paternosters, eh?”

Father Jerome smiled.

“No; a man cannot plead so in his own defense; our first father tried

that, but the plea was not allowed. But, now, there is our absent

friend. I tell you truly this whole community ought to be recognized as

partners in his moral errors. Among another people, reared under wiser

care and with better companions, how different might he not have been!

How can we speak of him as a law-breaker who might have saved him from

that name?” Here the speaker turned to Jean Thompson, and changed his

speech to English. “A lady sez to me to-day: ‘Père Jerome, ’ow dat is a

dreadfool dat ’e gone at de coas’ of Cuba to be one corsair! Aint it?’

“Ah, Madame,’ I sez, ‘‘tis a terrible! I’ope de good God will fo’give me

an’ you fo’ dat!’”

Jean Thompson answered quickly:

“You should not have let her say that.”

“Mais, fo’ w’y?”

“Why, because, if you are partly responsible, you ought so much the

more to do what you can to shield his reputation. You should have

said,” — the attorney changed to French, — “‘He is no pirate; he has

merely taken out letters of marque and reprisal under the flag of the

republic of Carthagena!’”

“Ah, bah!” exclaimed Doctor Varrillat, and both he and his

brother-in-law, the priest, laughed.

“Why not?” demanded Thompson.

“Oh!” said the physician, with a shrug, “say id thad way iv you wand.”

Then, suddenly becoming serious, he was about to add something else,

when Père Jerome spoke.

“I will tell you what I could have said. I could have said: ‘Madame,

yes; ’tis a terrible fo’ him. He stum’le in de dark; but dat good God

will mek it a mo’ terrible fo’ dat man, oohever he is, w’at put ’at

light out!’”

“But how do you know he is a pirate?” demanded Thompson, aggressively.

“How do we know?” said the little priest, returning to French. “Ah!

there is no other explanation of the ninety-and-nine stories that come

to us, from every port where ships arrive from the north coast of Cuba,

of a commander of pirates there who is a marvel of courtesy and

gentility —— ”

“And whose name is Lafitte,” said the obstinate attorney.

“And who, nevertheless, is not Lafitte,” insisted Père Jerome.

“Daz troo, Jean,” said Doctor Varrillat. “We hall know daz troo.”

Père Jerome leaned forward over the board and spoke, with an air of

secrecy, in French.

“You have heard of the ship which came into port here last Monday. You

have heard that she was boarded by pirates, and that the captain of the

ship himself drove them off.”

“An incredible story,” said Thompson.

“But not so incredible as the truth. I have it from a passenger. There

was on the ship a young girl who was very beautiful. She came on deck,

where the corsair stood, about to issue his orders, and, more beautiful

than ever in the desperation of the moment, confronted him with a small

missal spread open, and, her finger on the Apostles’ Creed, commanded

him to read. He read it, uncovering his head as he read, then stood

gazing on her face, which did not quail; and then, with a low bow, said:

‘Give me this book and I will do your bidding.’ She gave him the book

and bade him leave the ship, and he left it unmolested.”

Père Jerome looked from the physician to the attorney and back again,

once or twice, with his dimpled smile.

“But he speaks English, they say,” said Jean Thompson.

“He has, no doubt, learned it since he left us,” said the priest.

“But this ship-master, too, says his men called him Lafitte.”

“Lafitte? No. Do you not see? It is your brother-in-law, Jean Thompson!

It is your wife’s brother! Not Lafitte, but” (softly) “Lemaitre!

Lemaitre! Capitaine Ursin Lemaitre!”

The two guests looked at each other with a growing drollery on either

face, and presently broke into a laugh.

“Ah!” said the doctor, as the three rose up, “you juz kip dad

cog-an’-bull fo’ yo’ negs summon.”

Père Jerome’s eyes lighted up —

“I goin’ to do it!”

“I tell you,” said Evariste, turning upon him with sudden gravity, “iv

dad is troo, I tell you w’ad is sure-sure! Ursin Lemaitre din kyare

nut’n fo’ doze creed; he fall in love!”

Then, with a smile, turning to Jean Thompson, and back again to Père

Jerome:

“But anny’ow you tell it in dad summon dad ’e kyare fo’ dad creed.”

Père Jerome sat up late that night, writing a letter. The remarkable

effects upon a certain mind, effects which we shall presently find him

attributing solely to the influences of surrounding nature, may find for

some a more sufficient explanation in the fact that this letter was but

one of a series, and that in the rover of doubted identity and

incredible eccentricity Père Jerome had a regular correspondent.

About two months after the conversation just given, and therefore

somewhere about the Christmas holidays of the year 1821, Père Jerome

delighted the congregation of his little chapel with the announcement

that he had appointed to preach a sermon in French on the following

Sabbath — not there, but in the cathedral.

He was much beloved. Notwithstanding that among the clergy there were

two or three who shook their heads and raised their eyebrows, and said

he would be at least as orthodox if he did not make quite so much of the

Bible and quite so little of the dogmas, yet “the common people heard

him gladly.” When told, one day, of the unfavorable whispers, he smiled

a little and answered his informant, — whom he knew to be one of the

whisperers himself, — laying a hand kindly upon his shoulder:

“Father Murphy,” — or whatever the name was, — “your words comfort me.”

“How is that?”

“Because —

‘Væ quum benedixerint mihi homines!’”

The appointed morning, when it came, was one of those exquisite days in

which there is such a universal harmony, that worship rises from the

heart like a spring.

“Truly,” said Père Jerome to the companion who was to assist him in the

mass, “this is a Sabbath day which we do not have to make holy, but only

to keep so.”

May be it was one of the secrets of Père Jerome’s success as a preacher,

that he took more thought as to how he should feel, than as to what he

should say.

The cathedral of those days was called a very plain old pile, boasting

neither beauty nor riches; but to Père Jerome it was very lovely; and

before its homely altar, not homely to him, in the performance of those

solemn offices, symbols of heaven’s mightiest truths, in the hearing of

the organ’s harmonies, and the yet more eloquent interunion of human

voices in the choir, in overlooking the worshipping throng which knelt

under the soft, chromatic lights, and in breathing the sacrificial odors

of the chancel, he found a deep and solemn joy; and yet I guess the

finest thought of his soul the while was one that came thrice and again:

“Be not deceived, Père Jerome, because saintliness of feeling is easy

here; you are the same priest who overslept this morning, and overate

yesterday, and will, in some way, easily go wrong to-morrow and the day

after.”

He took it with him when — the

Veni Creator

sung — he went into the

pulpit. Of the sermon he preached, tradition has preserved for us only a

few brief sayings, but they are strong and sweet.

“My friends,” he said, — this was near the beginning, — “the angry words

of God’s book are very merciful — they are meant to drive us home; but

the tender words, my friends, they are sometimes terrible! Notice these,

the tenderest words of the tenderest prayer that ever came from the lips

of a blessed martyr — the dying words of the holy Saint Stephen, ’Lord,

lay not this sin to their charge.’ Is there nothing dreadful in that?

Read it thus: ’Lord, lay not this sin to their charge.’ Not to the

charge of them who stoned him? To whose charge then? Go ask the holy

Saint Paul. Three years afterward, praying in the temple at Jerusalem,

he answered that question: ’I stood by and consented.’ He answered for

himself only; but the Day must come when all that wicked council that

sent Saint Stephen away to be stoned, and all that city of Jerusalem,

must hold up the hand and say: ’We, also, Lord — we stood by.’ Ah!

friends, under the simpler meaning of that dying saint’s prayer for the

pardon of his murderers is hidden the terrible truth that we all have a

share in one another’s sins.”

Thus Père Jerome touched his key-note. All that time has spared us

beside may be given in a few sentences.

“Ah!” he cried once, “if it were merely my own sins that I had to answer

for, I might hold up my head before the rest of mankind; but no, no, my

friends — we cannot look each other in the face, for each has helped the

other to sin. Oh, where is there any room, in this world of common

disgrace, for pride? Even if we had no common hope, a common despair

ought to bind us together and forever silence the voice of scorn!”

And again, this:

“Even in the promise to Noë, not again to destroy the race with a flood,

there is a whisper of solemn warning. The moral account of the

antediluvians was closed off and the balance brought down in the year of

the deluge; but the account of those who come after runs on and on, and

the blessed bow of promise itself warns us that God will not stop it

till the Judgment Day! O God, I thank thee that that day must come at

last, when thou wilt destroy the world, and stop the interest on my

account!”

It was about at this point that Père Jerome noticed, more particularly

than he had done before, sitting among the worshippers near him, a

small, sad-faced woman, of pleasing features, but dark and faded, who

gave him profound attention. With her was another in better dress,

seemingly a girl still in her teens, though her face and neck were

scrupulously concealed by a heavy veil, and her hands, which were small,

by gloves.

“Quadroones,” thought he, with a stir of deep pity.

Once, as he uttered some stirring word, he saw the mother and daughter

(if such they were), while they still bent their gaze upon him, clasp

each other’s hand fervently in the daughter’s lap. It was at these

words:

“My friends, there are thousands of people in this city of New Orleans

to whom society gives the ten commandments of God with all the nots

rubbed out! Ah! good gentlemen! if God sends the poor weakling to

purgatory for leaving the right path, where ought some of you to go who

strew it with thorns and briers!”

The movement of the pair was only seen because he watched for it. He

glanced that way again as he said:

“O God, be very gentle with those children who would be nearer heaven

this day had they never had a father and mother, but had got their

religious training from such a sky and earth as we have in Louisiana

this holy morning! Ah! my friends, nature is a big-print catechism!”

The mother and daughter leaned a little farther forward, and exchanged

the same spasmodic hand-pressure as before. The mother’s eyes were full

of tears.

“I once knew a man,” continued the little priest, glancing to a side

aisle where he had noticed Evariste and Jean sitting against each other,

“who was carefully taught, from infancy to manhood, this single only

principle of life: defiance. Not justice, not righteousness, not even

gain; but defiance: defiance to God, defiance to man, defiance to

nature, defiance to reason; defiance and defiance and defiance.”

“He is going to tell it!” murmured Evariste to Jean.

“This man,” continued Père Jerome, “became a smuggler and at last a

pirate in the Gulf of Mexico. Lord, lay not that sin to his charge

alone! But a strange thing followed. Being in command of men of a sort

that to control required to be kept at the austerest distance, he now

found himself separated from the human world and thrown into the solemn

companionship with the sea, with the air, with the storm, the calm, the

heavens by day, the heavens by night. My friends, that was the first

time in his life that he ever found himself in really good company.

“Now, this man had a great aptness for accounts. He had kept them — had

rendered them. There was beauty, to him, in a correct, balanced, and

closed account. An account unsatisfied was a deformity. The result is

plain. That man, looking out night after night upon the grand and holy

spectacle of the starry deep above and the watery deep below, was sure

to find himself, sooner or later, mastered by the conviction that the

great Author of this majestic creation keeps account of it; and one

night there came to him, like a spirit walking on the sea, the awful,

silent question: ’My account with God — how does it stand?’ Ah! friends,

that is a question which the book of nature does not answer.

“Did I say the book of nature is a catechism? Yes. But, after it answers

the first question with ’God,’ nothing but questions follow; and so, one

day, this man gave a ship full of merchandise for one little book which

answered those questions. God help him to understand it! and God help

you, monsieur and you, madame, sitting here in your smuggled clothes,

to beat upon the breast with me and cry, ’I, too, Lord — I, too, stood by

and consented.’”

Père Jerome had not intended these for his closing words; but just

there, straight away before his sight and almost at the farthest door, a

man rose slowly from his seat and regarded him steadily with a kind,

bronzed, sedate face, and the sermon, as if by a sign of command, was

ended. While the Credo was being chanted he was still there; but when,

a moment after its close, the eye of Père Jerome returned in that

direction, his place was empty.

As the little priest, his labor done and his vestments changed, was

turning into the Rue Royale and leaving the cathedral out of sight, he

just had time to understand that two women were purposely allowing him

to overtake them, when the one nearer him spoke in the Creole patois,

saying, with some timid haste:

“Good-morning, Père — Père Jerome; Père Jerome, we thank the good God for

that sermon.”

“Then, so do I,” said the little man. They were the same two that he had

noticed when he was preaching. The younger one bowed silently; she was a

beautiful figure, but the slight effort of Père Jerome’s kind eyes to

see through the veil was vain. He would presently have passed on, but

the one who had spoken before said:

“I thought you lived in the Rue des Ursulines.”

“Yes; I am going this way to see a sick person.”

The woman looked up at him with an expression of mingled confidence and

timidity.

“It must be a blessed thing to be so useful as to be needed by the good

God,” she said.

Père Jerome smiled:

“God does not need me to look after his sick; but he allows me to do it,

just as you let your little boy in frocks carry in chips.” He might have

added that he loved to do it, quite as much.

It was plain the woman had somewhat to ask, and was trying to get

courage to ask it.

“You have a little boy?” asked the priest.

“No, I have only my daughter;” she indicated the girl at her side. Then

she began to say something else, stopped, and with much nervousness

asked:

“Père Jerome, what was the name of that man?”

“His name?” said the priest. “You wish to know his name?”

“Yes,

Monsieur

“ (or Miché, as she spoke it); “it was such a beautiful

story.” The speaker’s companion looked another way.

“His name,” said Father Jerome, — “some say one name and some another.

Some think it was Jean Lafitte, the famous; you have heard of him? And

do you go to my church, Madame —— ?”

“No, Miché; not in the past; but from this time, yes. My name” — she

choked a little, and yet it evidently gave her pleasure to offer this

mark of confidence — “is Madame Delphine — Delphine Carraze.”

Père Jerome’s smile and exclamation, as some days later he entered his

parlor in response to the announcement of a visitor, were indicative of

hearty greeting rather than surprise.

“Madame Delphine!”

Yet surprise could hardly have been altogether absent, for though

another Sunday had not yet come around, the slim, smallish figure

sitting in a corner, looking very much alone, and clad in dark attire,

which seemed to have been washed a trifle too often, was Delphine

Carraze on her second visit. And this, he was confident, was over and

above an attendance in the confessional, where he was sure he had

recognized her voice.

She rose bashfully and gave her hand, then looked to the floor, and

began a faltering speech, with a swallowing motion in the throat, smiled

weakly and commenced again, speaking, as before, in a gentle, low note,

frequently lifting up and casting down her eyes, while shadows of

anxiety and smiles of apology chased each other rapidly across her face.

She was trying to ask his advice.

“Sit down,” said he; and when they had taken seats she resumed, with

downcast eyes:

“You know, — probably I should have said this in the confessional, but —

“No matter, Madame Delphine; I understand; you did not want an oracle,

perhaps; you want a friend.”

She lifted her eyes, shining with tears, and dropped them again.

“I” — she ceased. “I have done a” — she dropped her head and shook it

despondingly — “a cruel thing.” The tears rolled from her eyes as she

turned away her face.

Père Jerome remained silent, and presently she turned again, with the

evident intention of speaking at length.

“It began nineteen years ago — by” — her eyes, which she had lifted, fell

lower than ever, her brow and neck were suffused with blushes, and she

murmured — “I fell in love.”

She said no more, and by and by Père Jerome replied:

“Well, Madame Delphine, to love is the right of every soul. I believe in

love. If your love was pure and lawful I am sure your angel guardian

smiled upon you; and if it was not, I cannot say you have nothing to

answer for, and yet I think God may have said: ’She is a quadroone; all

the rights of her womanhood trampled in the mire, sin made easy to

her — almost compulsory, — charge it to account of whom it may concern.”

“No, no!” said Madame Delphine, looking up quickly, “some of it might

fall upon — “Her eyes fell, and she commenced biting her lips and

nervously pinching little folds in her skirt. “He was good — as good as

the law would let him be — better, indeed, for he left me property, which

really the strict law does not allow. He loved our little daughter very

much. He wrote to his mother and sisters, owning all his error and

asking them to take the child and bring her up. I sent her to them when

he died, which was soon after, and did not see my child for sixteen

years. But we wrote to each other all the time, and she loved me. And

then — at last —” Madame Delphine ceased speaking, but went on diligently

with her agitated fingers, turning down foolish hems lengthwise of her

lap.

“At last your mother-heart conquered,” said Père Jerome.

She nodded.

“The sisters married, the mother died; I saw that even where she was she

did not escape the reproach of her birth and blood, and when she asked

me to let her come — .” The speaker’s brimming eyes rose an instant. “I

know it was wicked, but — I said, come.”

The tears dripped through her hands upon her dress.

“Was it she who was with you last Sunday?”

“Yes.”

“And now you do not know what to do with her?”

“Ah! c’est ça, oui! — that is it.”

“Does she look like you, Madame Delphine?”

“Oh, thank God, no! you would never believe she was my daughter; she is

white and beautiful!”

“You thank God for that which is your main difficulty, Madame Delphine.”

“Alas! yes.”

Père Jerome laid his palms tightly across his knees with his arms bowed

out, and fixed his eyes upon the ground, pondering.

“I suppose she is a sweet, good daughter?” said he, glancing at Madame

Delphine without changing his attitude.

Her answer was to raise her eyes rapturously.

“Which gives us the dilemma in its fullest force,” said the priest,

speaking as if to the floor. “She has no more place than if she had

dropped upon a strange planet.” He suddenly looked up with a brightness

which almost as quickly passed away, and then he looked down again. His

happy thought was the cloister; but he instantly said to himself: “They

cannot have overlooked that choice, except intentionally — which they

have a right to do.” He could do nothing but shake his head.

“And suppose you should suddenly die,” he said; he wanted to get at once

to the worst.

The woman made a quick gesture, and buried her head in her handkerchief,

with the stifled cry:

“Oh, Olive, my daughter!”

“Well, Madame Delphine,” said Père Jerome, more buoyantly, “one thing is

sure: we must find a way out of this trouble.”

“Ah!” she exclaimed, looking heavenward, “if it might be!”

“But it must be!” said the priest.

“But how shall it be?” asked the desponding woman.

“Ah!” said Père Jerome, with a shrug, “God knows.”

“Yes,” said the quadroone, with a quick sparkle in her gentle eye; “and

I know, if God would tell anybody, He would tell you!”

The priest smiled and rose.

“Do you think so? Well, leave me to think of it. I will ask Him.”

“And He will tell you!” she replied. “And He will bless you!” She rose

and gave her hand. As she withdrew it she smiled. “I had such a strange

dream,” she said, backing toward the door.

“Yes?”

“Yes. I got my troubles all mixed up with your sermon. I dreamed I made

that pirate the guardian of my daughter.”

Père Jerome smiled also, and shrugged.

“To you, Madame Delphine, as you are placed, every white man in this

country, on land or on water, is a pirate, and of all pirates, I think

that one is, without doubt, the best.”

“Without doubt,” echoed Madame Delphine, wearily, still withdrawing

backward. Père Jerome stepped forward and opened the door.

The shadow of some one approaching it from without fell upon the

threshold, and a man entered, dressed in dark blue cottonade, lifting

from his head a fine Panama hat, and from a broad, smooth brow, fair

where the hat had covered it and dark below, gently stroking back his

very soft, brown locks. Madame Delphine slightly started aside, while

Père Jerome reached silently, but eagerly, forward, grasped a larger

hand than his own, and motioned its owner to a seat. Madame Delphine’s

eyes ventured no higher than to discover that the shoes of the visitor

were of white duck.

“Well, Père Jerome,” she said, in a hurried under-tone, “I am just going

to say Hail Marys all the time till you find that out for me!”

“Well, I hope that will be soon, Madame Carraze. Good-day, Madame

Carraze.”

And as she departed, the priest turned to the new-comer and extended

both hands, saying, in the same familiar dialect in which he had been

addressing the quadroone:

“Well-a-day, old playmate! After so many years!”

They sat down side by side, like husband and wife, the priest playing

with the other’s hand, and talked of times and seasons past, often

mentioning Evariste and often Jean.

Madame Delphine stopped short half-way home and returned to Père

Jerome’s. His entry door was wide open and the parlor door ajar. She

passed through the one and with downcast eyes was standing at the other,

her hand lifted to knock, when the door was drawn open and the white

duck shoes passed out. She saw, besides, this time the blue cottonade

suit.

“Yes,” the voice of Père Jerome was saying, as his face appeared in the

door — “Ah! Madame — ”

“I lef’ my parasol,” said Madame Delphine, in English.

There was this quiet evidence of a defiant spirit hidden somewhere down

under her general timidity, that, against a fierce conventional

prohibition, she wore a bonnet instead of the turban of her caste, and

carried a

parasol.

Père Jerome turned and brought it.

He made a motion in the direction in which the late visitor had

disappeared.

“Madame Delphine, you saw dat man?”

“Not his face.”

“You couldn’ billieve me iv I tell you w’at dat man purpose to do!”

“Is dad so, Père Jerome?”

“He’s goin’ to hopen a bank!”

“Ah!” said Madame Delphine, seeing she was expected to be astonished.

Père Jerome evidently longed to tell something that was best kept

secret; he repressed the impulse, but his heart had to say something. He

threw forward one hand and looking pleasantly at Madame Delphine, with

his lips dropped apart, clenched his extended hand and thrusting it

toward the ground, said in a solemn under-tone:

“He is God’s own banker, Madame Delphine.”

Madame Delphine sold one of the corner lots of her property. She had

almost no revenue, and now and then a piece had to go. As a consequence

of the sale, she had a few large bank-notes sewed up in her petticoat,

and one day — may be a fortnight after her tearful interview with Père

Jerome — she found it necessary to get one of these changed into small

money. She was in the Rue Toulouse, looking from one side to the other

for a bank which was not in that street at all, when she noticed a small

sign hanging above a door, bearing the name “Vignevielle.” She looked

in. Père Jerome had told her (when she had gone to him to ask where she

should apply for change) that if she could only wait a few days, there

would be a new concern opened in Toulouse street, — it really seemed as

if Vignevielle was the name, if she could judge; it looked to be, and it

was, a private banker’s, — “U. L. Vignevielle’s,” according to a larger

inscription which met her eyes as she ventured in. Behind the counter,

exchanging some last words with a busy-mannered man outside, who, in

withdrawing, seemed bent on running over Madame Delphine, stood the man

in blue cottonade, whom she had met in Père Jerome’s door-way. Now, for

the first time, she saw his face, its strong, grave, human kindness

shining softly on each and every bronzed feature. The recognition was

mutual. He took pains to speak first, saying, in a re-assuring tone, and

in the language he had last heard her use:

“’Ow I kin serve you, Madame?”

“Iv you pliz, to mague dad bill change, Miché.”

She pulled from her pocket a wad of dark cotton handkerchief, from which

she began to untie the imprisoned note. Madame Delphine had an

uncommonly sweet voice, and it seemed so to strike Monsieur Vignevielle.

He spoke to her once or twice more, as he waited on her, each time in

English, as though he enjoyed the humble melody of its tone, and

presently, as she turned to go, he said:

“Madame Carraze!”

She started a little, but bethought herself instantly that he had heard

her name in Père Jerome’s parlor. The good father might even have said a

few words about her after her first departure; he had such an

overflowing heart.

“Madame Carraze,” said Monsieur Vignevielle, “doze kine of note wad you

’an’ me juz now is bein’ contrefit. You muz tek kyah from doze kine of

note. You see —” He drew from his cash-drawer a note resembling the one

he had just changed for her, and proceeded to point out certain tests of

genuineness. The counterfeit, he said, was so and so.

“Bud,” she exclaimed, with much dismay, “dad was de manner of my bill!

Id muz be — led me see dad bill wad I give you, — if you pliz, Miché.”

Monsieur Vignevielle turned to engage in conversation with an employé

and a new visitor, and gave no sign of hearing Madame Delphine’s voice.

She asked a second time, with like result, lingered timidly, and as he

turned to give his attention to a third visitor, reiterated:

“Miché Vignevielle, I wizh you pliz led —— ”

“Madame Carraze,” he said, turning so suddenly as to make the frightened

little woman start, but extending his palm with a show of frankness, and

assuming a look of benignant patience, “‘ow I kin fine doze note now,

mongs’ all de rez? Iv you pliz nod to mague me doze troub’.”

The dimmest shadow of a smile seemed only to give his words a more

kindly authoritative import, and as he turned away again with a manner

suggestive of finality, Madame Delphine found no choice but to depart.

But she went away loving the ground beneath the feet of Monsieur U. L.

Vignevielle.

“Oh, Père Jerome!” she exclaimed in the corrupt French of her caste,

meeting the little father on the street a few days later, “you told the

truth that day in your parlor. Mo conné li à c’t heure. I know him

now; he is just what you called him.”

“Why do you not make him your banker, also, Madame Delphine?”

“I have done so this very day!” she replied, with more happiness in her

eyes than Père Jerome had ever before seen there.

“Madame Delphine,” he said, his own eyes sparkling, “make him your

daughter’s guardian; for myself, being a priest, it would not be best;

but ask him; I believe he will not refuse you.”

Madame Delphine’s face grew still brighter as he spoke.

“It was in my mind,” she said.

Yet to the timorous Madame Delphine many trifles became, one after

another, an impediment to the making of this proposal, and many weeks

elapsed before further delay was positively without excuse. But at

length, one day in May, 1822, in a small private office behind Monsieur

Vignevielle’s banking-room, — he sitting beside a table, and she, more

timid and demure than ever, having just taken a chair by the door, — she

said, trying, with a little bashful laugh, to make the matter seem

unimportant, and yet with some tremor of voice:

“Miché Vignevielle, I bin maguing my will.” (Having commenced their

acquaintance in English, they spoke nothing else.)

“’Tis a good idy,” responded the banker.

“I kin mague you de troub’ to kib dad will fo’ me, Miché Vignevielle?”

“Yez.”

She looked up with grateful re-assurance; but her eyes dropped again as

she said:

“Miché Vignevielle ——” Here she choked, and began her peculiar motion

of laying folds in the skirt of her dress, with trembling fingers. She

lifted her eyes, and as they met the look of deep and placid kindness

that was in his face, some courage returned, and she said:

“Miché.”

“Wad you wand?” asked he, gently.

“If it arrive to me to die —— ”

“Yez?”

Her words were scarcely audible:

“I wand you teg kyah my lill’ girl.”

“You ’ave one lill’ gal, Madame Carraze?”

She nodded with her face down.

“An’ you godd some mo’ chillen?”

“No.”

“I nevva know dad, Madame Carraze. She’s a lill’ small gal?”

Mothers forget their daughters’ stature. Madame Delphine said:

“Yez.”

For a few moments neither spoke, and then Monsieur Vignevielle said:

“I will do dad.”

“Lag she been you’ h-own?” asked the mother, suffering from her own

boldness.

“She’s a good lill’ chile, eh?”

“Miché, she’s a lill’ hangel!” exclaimed Madame Delphine, with a look of

distress.

“Yez; I teg kyah ’v ’er, lag my h-own. I mague you dad promise.”

“But ——” There was something still in the way, Madame Delphine seemed

to think.

The banker waited in silence.

“I suppose you will want to see my lill’ girl?”

He smiled; for she looked at him as if she would implore him to decline.

“Oh, I tek you’ word fo’ hall dad, Madame Carraze. It mague no differend

wad she loog lag; I don’ wan’ see ’er.”

Madame Delphine’s parting smile — she went very shortly — was gratitude

beyond speech.

Monsieur Vignevielle returned to the seat he had left, and resumed a

newspaper, — the Louisiana Gazette in all probability, — which he had

laid down upon Madame Delphine’s entrance. His eyes fell upon a

paragraph which had previously escaped his notice. There they rested.

Either he read it over and over unwearyingly, or he was lost in thought.

Jean Thompson entered.

“Now,” said Mr. Thompson, in a suppressed tone, bending a little across

the table, and laying one palm upon a package of papers which lay in the

other, “it is completed. You could retire from your business any day

inside of six hours without loss to anybody.” (Both here and elsewhere,

let it be understood that where good English is given the words were

spoken in good French.)

Monsieur Vignevielle raised his eyes and extended the newspaper to the

attorney, who received it and read the paragraph. Its substance was that

a certain vessel of the navy had returned from a cruise in the Gulf of

Mexico and Straits of Florida, where she had done valuable service

against the pirates — having, for instance, destroyed in one fortnight in

January last twelve pirate vessels afloat, two on the stocks, and three

establishments ashore.

“United States brig Porpoise,” repeated Jean Thompson. “Do you know

her?”

“We are acquainted,” said Monsieur Vignevielle.

A quiet footstep, a grave new presence on financial sidewalks, a neat

garb slightly out of date, a gently strong and kindly pensive face, a

silent bow, a new sign in the Rue Toulouse, a lone figure with a cane,

walking in meditation in the evening light under the willows of Canal

Marigny, a long-darkened window re-lighted in the Rue Conti — these were

all; a fall of dew would scarce have been more quiet than was the return

of Ursin Lemaitre-Vignevielle to the precincts of his birth and early

life.

But we hardly give the event its right name. It was Capitaine Lemaitre

who had disappeared; it was Monsieur Vignevielle who had come back. The

pleasures, the haunts, the companions, that had once held out their

charms to the impetuous youth, offered no enticements to Madame

Delphine’s banker. There is this to be said even for the pride his

grandfather had taught him, that it had always held him above low

indulgences; and though he had dallied with kings, queens, and knaves

through all the mazes of Faro, Rondeau, and Craps, he had done it

loftily; but now he maintained a peaceful estrangement from all.

Evariste and Jean, themselves, found him only by seeking.

“It is the right way,” he said to Père Jerome, the day we saw him there.

“Ursin Lemaitre is dead. I have buried him. He left a will. I am his

executor.”

“He is crazy,” said his lawyer brother-in-law, impatiently.

“On the contr-y,” replied the little priest, “‘e ’as come ad hisse’f.”

Evariste spoke.

“Look at his face, Jean. Men with that kind of face are the last to go

crazy.”

“You have not proved that,” replied Jean, with an attorney’s obstinacy.

“You should have heard him talk the other day about that newspaper

paragraph. ’I have taken Ursin Lemaitre’s head; I have it with me; I

claim the reward, but I desire to commute it to citizenship.’ He is

crazy.”

Of course Jean Thompson did not believe what he said; but he said it,

and, in his vexation, repeated it, on the

banquettes

and at the clubs;

and presently it took the shape of a sly rumor, that the returned rover

was a trifle snarled in his top-hamper.

This whisper was helped into circulation by many trivial eccentricities

of manner, and by the unaccountable oddness of some of his transactions

in business.

“My dear sir!” cried his astounded lawyer, one day, “you are not running

a charitable institution!”

“How do you know?” said Monsieur Vignevielle. There the conversation

ceased.

“Why do you not found hospitals and asylums at once,” asked the

attorney, at another time, with a vexed laugh, “and get the credit of

it?”

“And make the end worse than the beginning,” said the banker, with a

gentle smile, turning away to a desk of books.

“Bah!” muttered Jean Thompson.

Monsieur Vignevielle betrayed one very bad symptom. Wherever he went he

seemed looking for somebody. It may have been perceptible only to those

who were sufficiently interested in him to study his movements; but

those who saw it once saw it always. He never passed an open door or

gate but he glanced in; and often, where it stood but slightly ajar, you

might see him give it a gentle push with his hand or cane. It was very

singular.

He walked much alone after dark. The guichinangoes (garroters, we

might say), at those times the city’s particular terror by night, never

crossed his path. He was one of those men for whom danger appears to

stand aside.

One beautiful summer night, when all nature seemed hushed in ecstasy,

the last blush gone that told of the sun’s parting, Monsieur

Vignevielle, in the course of one of those contemplative, uncompanioned

walks which it was his habit to take, came slowly along the more open

portion of the Rue Royale, with a step which was soft without intention,

occasionally touching the end of his stout cane gently to the ground and

looking upward among his old acquaintances, the stars.

It was one of those southern nights under whose spell all the sterner

energies of the mind cloak themselves and lie down in bivouac, and the

fancy and the imagination, that cannot sleep, slip their fetters and

escape, beckoned away from behind every flowering bush and

sweet-smelling tree, and every stretch of lonely, half-lighted walk, by

the genius of poetry. The air stirred softly now and then, and was still

again, as if the breezes lifted their expectant pinions and lowered them

once more, awaiting the rising of the moon in a silence which fell upon

the fields, the roads, the gardens, the walls, and the suburban and

half-suburban streets, like a pause in worship. And anon she rose.

Monsieur Vignevielle’s steps were bent toward the more central part of

the town, and he was presently passing along a high, close, board-fence,

on the right-hand side of the way, when, just within this inclosure, and

almost overhead, in the dark boughs of a large orange-tree, a

mocking-bird began the first low flute-notes of his all-night song. It

may have been only the nearness of the songster that attracted the

passer’s attention, but he paused and looked up.

And then he remarked something more, — that the air where he had stopped

was filled with the overpowering sweetness of the night-jasmine. He

looked around; it could only be inside the fence. There was a gate just

there. Would he push it, as his wont was? The grass was growing about it

in a thick turf, as though the entrance had not been used for years. An

iron staple clasped the cross-bar, and was driven deep into the

gate-post. But now an eye that had been in the blacksmithing

business — an eye which had later received high training as an eye for

fastenings — fell upon that staple, and saw at a glance that the wood

had shrunk from it, and it had sprung from its hold, though without

falling out. The strange habit asserted itself; he laid his large hand

upon the cross-bar; the turf at the base yielded, and the tall gate was

drawn partly open.

At that moment, as at the moment whenever he drew or pushed a door or

gate, or looked in at a window, he was thinking of one, the image of

whose face and form had never left his inner vision since the day it had

met him in his life’s path and turned him face about from the way of

destruction.

The bird ceased. The cause of the interruption, standing within the

opening, saw before him, much obscured by its own numerous shadows, a

broad, ill-kept, many-flowered garden, among whose untrimmed rose-trees

and tangled vines, and often, also, in its old walks of pounded shell,

the coco-grass and crab-grass had spread riotously, and sturdy weeds

stood up in bloom. He stepped in and drew the gate to after him. There,

very near by, was the clump of jasmine, whose ravishing odor had

tempted him. It stood just beyond a brightly moonlit path, which turned

from him in a curve toward the residence, a little distance to the

right, and escaped the view at a point where it seemed more than likely

a door of the house might open upon it. While he still looked, there

fell upon his ear, from around that curve, a light footstep on the

broken shells, — one only, and then all was for a moment still again. Had

he mistaken? No. The same soft click was repeated nearer by, a pale

glimpse of robes came through the tangle, and then, plainly to view,

appeared an outline — a presence — a form — a spirit — a girl!

From throat to instep she was as white as Cynthia. Something above the

medium height, slender, lithe, her abundant hair rolling in dark, rich

waves back from her brows and down from her crown, and falling in two

heavy plaits beyond her round, broadly girt waist and full to her knees,

a few escaping locks eddying lightly on her graceful neck and her

temples, — her arms, half hid in a snowy mist of sleeve, let down to

guide her spotless skirts free from the dewy touch of the

grass, — straight down the path she came!

Will she stop? Will she turn aside? Will she espy the dark form in the

deep shade of the orange, and, with one piercing scream, wheel and

vanish? She draws near. She approaches the jasmine; she raises her arms,

the sleeves falling like a vapor down to the shoulders; rises upon

tiptoe, and plucks a spray. O Memory! Can it be? Can it be? Is this

his quest, or is it lunacy? The ground seems to M. Vignevielle the

unsteady sea, and he to stand once more on a deck. And she? As she is

now, if she but turn toward the orange, the whole glory of the moon will

shine upon her face. His heart stands still; he is waiting for her to do

that. She reaches up again; this time a bunch for her mother. That neck

and throat! Now she fastens a spray in her hair. The mocking-bird cannot

withhold; he breaks into song — she turns — she turns her face — it is she,

it is she! Madame Delphine’s daughter is the girl he met on the ship.

She was just passing seventeen — that beautiful year when the heart of

the maiden still beats quickly with the surprise of her new dominion,

while with gentle dignity her brow accepts the holy coronation of

womanhood. The forehead and temples beneath her loosely bound hair were

fair without paleness, and meek without languor. She had the soft,

lacklustre beauty of the South; no ruddiness of coral, no waxen white,

no pink of shell; no heavenly blue in the glance; but a face that

seemed, in all its other beauties, only a tender accompaniment for the

large, brown, melting eyes, where the openness of child-nature mingled

dreamily with the sweet mysteries of maiden thought. We say no color of

shell on face or throat; but this was no deficiency, that which took

its place being the warm, transparent tint of sculptured ivory.

This side door-way which led from Madame Delphine’s house into her

garden was overarched partly by an old remnant of vine-covered lattice,

and partly by a crape-myrtle, against whose small, polished trunk leaned

a rustic seat. Here Madame Delphine and Olive loved to sit when the

twilights were balmy or the moon was bright.

“Chérie,”

said Madame Delphine on one of these evenings, “why do you

dream so much?”

She spoke in the

patois

most natural to her, and which her daughter

had easily learned.

The girl turned her face to her mother, and smiled, then dropped her

glance to the hands in her own lap, which were listlessly handling the

end of a ribbon. The mother looked at her with fond solicitude. Her

dress was white again; this was but one night since that in which

Monsieur Vignevielle had seen her at the bush of night-jasmine. He had

not been discovered, but had gone away, shutting the gate, and leaving

it as he had found it.

Her head was uncovered. Its plaited masses, quite black in the

moonlight, hung down and coiled upon the bench, by her side. Her chaste

drapery was of that revived classic order which the world of fashion was

again laying aside to re-assume the mediæval bondage of the stay-lace;

for New Orleans was behind the fashionable world, and Madame Delphine

and her daughter were behind New Orleans. A delicate scarf, pale blue,

of lightly netted worsted, fell from either shoulder down beside her

hands. The look that was bent upon her changed perforce to one of gentle

admiration. She seemed the goddess of the garden.

Olive glanced up. Madame Delphine was not prepared for the movement, and

on that account repeated her question:

“What are you thinking about?”

The dreamer took the hand that was laid upon hers between her own palms,

bowed her head, and gave them a soft kiss.

The mother submitted. Wherefore, in the silence which followed, a

daughter’s conscience felt the burden of having withheld an answer, and

Olive presently said, as the pair sat looking up into the sky:

“I was thinking of Père Jerome’s sermon.”

Madame Delphine had feared so. Olive had lived on it ever since the day

it was preached. The poor mother was almost ready to repent having ever

afforded her the opportunity of hearing it. Meat and drink had become of

secondary value to her daughter; she fed upon the sermon.

Olive felt her mother’s thought and knew that her mother knew her own;

but now that she had confessed, she would ask a question:

“Do you think, maman, that Père Jerome knows it was I who gave that

missal?”

“No,” said Madame Delphine, “I am sure he does not.”

Another question came more timidly:

“Do — do you think he knows him?”

“Yes, I do. He said in his sermon he did.”

Both remained for a long time very still, watching the moon gliding in

and through among the small dark-and-white clouds. At last the daughter

spoke again.

“I wish I was Père — I wish I was as good as Père Jerome.”

“My child,” said Madame Delphine, her tone betraying a painful summoning

of strength to say what she had lacked the courage to utter, — “my child,

I pray the good God you will not let your heart go after one whom you

may never see in this world!”

The maiden turned her glance, and their eyes met. She cast her arms

about her mother’s neck, laid her cheek upon it for a moment, and then,

feeling the maternal tear, lifted her lips, and, kissing her, said:

“I will not! I will not!”

But the voice was one, not of willing consent, but of desperate

resolution.

“It would be useless, anyhow,” said the mother, laying her arm around

her daughter’s waist.

Olive repeated the kiss, prolonging it passionately.

“I have nobody but you,” murmured the girl; “I am a poor quadroone!”

She threw back her plaited hair for a third embrace, when a sound in the

shrubbery startled them.

“

Qui ci ça?

“ called Madame Delphine, in a frightened voice, as the two

stood up, holding to each other.

No answer.

“It was only the dropping of a twig,” she whispered, after a long

holding of the breath. But they went into the house and barred it

everywhere.

It was no longer pleasant to sit up. They retired, and in course of

time, but not soon, they fell asleep, holding each other very tight, and

fearing, even in their dreams, to hear another twig fall.

Monsieur Vignevielle looked in at no more doors or windows; but if the

disappearance of this symptom was a favorable sign, others came to

notice which were especially bad, — for instance, wakefulness. At

well-nigh any hour of the night, the city guard, which itself dared not

patrol singly, would meet him on his slow, unmolested, sky-gazing walk.

“Seems to enjoy it,” said Jean Thompson; “the worst sort of evidence. If

he showed distress of mind, it would not be so bad; but his

calmness, — ugly feature.”

The attorney had held his ground so long that he began really to believe

it was tenable.

By day, it is true, Monsieur Vignevielle was at his post in his quiet

“bank.” Yet here, day by day, he was the source of more and more vivid

astonishment to those who held preconceived notions of a banker’s

calling. As a banker, at least, he was certainly out of balance; while

as a promenader, it seemed to those who watched him that his ruling idea

had now veered about, and that of late he was ever on the quiet alert,

not to find, but to evade, somebody.

“Olive, my child,” whispered Madame Delphine one morning, as the pair

were kneeling side by side on the tiled floor of the church, “yonder is

Miché Vignevielle! If you will only look at once — he is just passing a

little in —— . Ah, much too slow again; he stepped out by the side

door.”

The mother thought it a strange providence that Monsieur Vignevielle

should always be disappearing whenever Olive was with her.

One early dawn, Madame Delphine, with a small empty basket on her arm,

stepped out upon the banquette in front of her house, shut and

fastened the door very softly, and stole out in the direction whence you

could faintly catch, in the stillness of the daybreak, the songs of the

Gascon butchers and the pounding of their meat-axes on the stalls of the

distant market-house. She was going to see if she could find some birds

for Olive, — the child’s appetite was so poor; and, as she was out, she

would drop an early prayer at the cathedral. Faith and works.

“One must venture something, sometimes, in the cause of religion,”

thought she, as she started timorously on her way. But she had not gone

a dozen steps before she repented her temerity. There was some one

behind her.

There should not be anything terrible in a footstep merely because it is

masculine; but Madame Delphine’s mind was not prepared to consider that.

A terrible secret was haunting her. Yesterday morning she had found a

shoe-track in the garden. She had not disclosed the discovery to Olive,

but she had hardly closed her eyes the whole night.

The step behind her now might be the fall of that very shoe. She

quickened her pace, but did not leave the sound behind. She hurried

forward almost at a run; yet it was still there — no farther, no nearer.

Two frights were upon her at once — one for herself, another for Olive,

left alone in the house; but she had but the one prayer — “God protect my

child!” After a fearful time she reached a place of safety, the

cathedral. There, panting, she knelt long enough to know the pursuit

was, at least, suspended, and then arose, hoping and praying all the

saints that she might find the way clear for her return in all haste to

Olive.

She approached a different door from that by which she had entered, her

eyes in all directions and her heart in her throat.

“Madame Carraze.”

She started wildly and almost screamed, though the voice was soft and

mild. Monsieur Vignevielle came slowly forward from the shade of the

wall. They met beside a bench, upon which she dropped her basket.

“Ah, Miché Vignevielle, I thang de good God to mid you!”

“Is dad so, Madame Carraze? Fo’ w’y dad is?”

“A man was chase me all dad way since my ’ouse!”

“Yes, Madame, I sawed him.”

“You sawed ’im? Oo it was?”

“’Twas only one man wad is a foolizh. De people say he’s crezzie.

Mais,

he don’ goin’ to meg you no ’arm.”

“But I was scare’ fo’ my lill’ girl.”

“Noboddie don’ goin’ trouble you’ lill’ gal, Madame Carraze.”

Madame Delphine looked up into the speaker’s strangely kind and patient

eyes, and drew sweet re-assurance from them.

“Madame,” said Monsieur Vignevielle, “wad pud you hout so hearly dis

morning?”

She told him her errand. She asked if he thought she would find

anything.

“Yez,” he said, “it was possible — a few lill’ bécassines-de-mer, ou

somezin’ ligue. But fo’ w’y you lill’ gal lose doze hapetide?”

“Ah, Miché,” — Madame Delphine might have tried a thousand times again

without ever succeeding half so well in lifting the curtain upon the

whole, sweet, tender, old, old-fashioned truth, — “Ah, Miché, she wone

tell me!”

“Bud, anny’ow, Madame, wad you thing?”

“Miché,” she replied, looking up again with a tear standing in either

eye, and then looking down once more as she began to speak, “I thing — I

thing she’s lonesome.”

“You thing?”

She nodded.

“Ah! Madame Carraze,” he said, partly extending his hand, “you see? ’Tis

impossible to mague you’ owze shud so tighd to priv-en dad. Madame, I

med one mizteg.”

“Ah, non, Miché!”

“Yez. There har nod one poss’bil’ty fo’ me to be dad guardian of you’

daughteh!”

Madame Delphine started with surprise and alarm.

“There is ondly one wad can be,” he continued.

“But oo, Miché?”

“God.”

“Ah, Miché Vignevielle ——” She looked at him appealingly.

“I don’ goin’ to dizzerd you, Madame Carraze,” he said.

She lifted her eyes. They filled. She shook her head, a tear fell, she

bit her lip, smiled, and suddenly dropped her face into both hands, sat

down upon the bench and wept until she shook.

“You dunno wad I mean, Madame Carraze?”

She did not know.

“I mean dad guardian of you’ daughteh godd to fine ’er now one ’uzban’;

an’ noboddie are hable to do dad egceb de good God ’imsev. But, Madame,

I tell you wad I do.”

She rose up. He continued:

“Go h-open you’ owze; I fin’ you’ daughteh dad’ uzban’.”

Madame Delphine was a helpless, timid thing; but her eyes showed she was

about to resent this offer. Monsieur Vignevielle put forth his hand — it

touched her shoulder — and said, kindly still, and without eagerness.

“One w’ite man, Madame; ’tis prattycabble. I know ’tis prattycabble.

One w’ite jantleman, Madame. You can truz me. I goin’ fedge ’im.

H-ondly you go h-open you’ owze.”

Madame Delphine looked down, twining her handkerchief among her fingers.

He repeated his proposition.

“You will come firz by you’se’f?” she asked.

“Iv you wand.”

She lifted up once more her eye of faith. That was her answer.

“Come,” he said, gently, “I wan’ sen’ some bird ad you’ lill’ gal.”

And they went away, Madame Delphine’s spirit grown so exaltedly bold

that she said as they went, though a violent blush followed her words:

“Miché Vignevielle, I thing Père Jerome mighd be ab’e to tell you

someboddie.”

Madame Delphine found her house neither burned nor rifled.

“Ah! ma piti sans popa! Ah! my little fatherless one!” Her faded

bonnet fell back between her shoulders, hanging on by the strings, and

her dropped basket, with its “few lill’ bécassines-de-mer” dangling

from the handle, rolled out its okra and soup-joint upon the floor. “Ma

piti! kiss! — kiss! — kiss!”

“But is it good news you have, or bad?” cried the girl, a fourth or

fifth time.

“Dieu sait, ma c’ère; mo pas conné!” — God knows, my darling; I cannot

tell!

The mother dropped into a chair, covered her face with her apron, and

burst into tears, then looked up with an effort to smile, and wept

afresh.

“What have you been doing?” asked the daughter, in a long-drawn,

fondling tone. She leaned forward and unfastened her mother’s

bonnet-strings. “Why do you cry?”

“For nothing at all, my darling; for nothing — I am such a fool.”

The girl’s eyes filled. The mother looked up into her face and said:

“No, it is nothing, nothing, only that —” turning her head from side to

side with a slow, emotional emphasis, “Miché Vignevielle is the

best — best man on the good Lord’s earth!”

Olive drew a chair close to her mother, sat down and took the little

yellow hands into her own white lap, and looked tenderly into her eyes.

Madame Delphine felt herself yielding; she must make a show of telling

something:

“He sent you those birds!”

The girl drew her face back a little. The little woman turned away,