George Washington Cable.

“Salome Müller: The White Slave.”

SALOME MÜLLER,

THE WHITE SLAVE.

TABLE OF CONTENTS. |

||

| Page | ||

| I. | Salome and her Kindred | 145 |

| II. | Six Months at Anchor | 148 |

| III. | Famine at Sea | 150 |

| IV. | Sold into Bondage | 155 |

| V. | The Lost Orphans | 159 |

| VI. | Christian Roselius | 162 |

| VII. | Miller Versus Belmonti | 163 |

| VIII. | The Trial | 169 |

| IX. | The Evidence | 173 |

| X. | The Crowning Proof | 178 |

| XI. | Judgment | 180 |

| XII. | Before the Supreme Court | 185 |

SALOME MÜLLER,

THE WHITE SLAVE.

1818—45.

I.

SALOME AND HER KINDRED.

SHE may be living yet, in 1889. For when she came to Louisiana, in 1818, she was too young for the voyage to fix itself in her memory. She could not, to-day, be more than seventy-five.

In Alsace, France, on the frontier of the Department of Lower Rhine, about twenty English miles from Strasburg, there was in those days, as I suppose there still is, a village called Langensoultz. The region was one of hills and valleys and of broad, flat meadows yearly overflowed by the Rhine. It was noted for its fertility; a land of wheat and wine, hop-fields, flax-fields, hay-stacks, and orchards.

It had been three hundred and seventy years under French rule, yet the people were still, in speech and traditions, German. Those were not the times to make them French. The land swept by Napoleon’s wars, their firesides robbed of fathers and sons by the conscription, the awful mortality of the Russian campaign, the emperor’s waning star, Waterloo — these were not the things or conditions to give them comfort in French domination. There was a widespread longing among them to seek another land where men and women and children were not doomed to feed the ambition of European princes.

In the summer of 1817 there lay at the Dutch port of Helder — for the great ship-canal that now lets the largest vessels out from Amsterdam was not yet constructed — a big, foul, old Russian ship which a certain man had bought purposing to crowd it full of emigrants to America.

These he had expected to find up the Rhine, and he was not disappointed. Hundreds responded from Alsace; some in Strasburg itself, and many from the surrounding villages, grain-fields, and vineyards. They presently numbered nine hundred, husbands, wives, and children. There was one family named Thomas, with a survivor of which I conversed in 1884. And there was Eva Kropp, née Hillsler, and her husband, with their daughter of fifteen, named for her mother. Also Eva Kropp’s sister Margaret and her husband, whose name does not appear. And there were Koelhoffer and his wife, and Frau Schultzheimer. There is no need to remember exact relationships. All these except the Thomases were of Langensoultz.

As they passed through another village some three miles away they were joined by a family of name not given, but the mother of which we shall know by and by, under a second husband’s name, as Madame Fleikener. And there too was one Wagner, two generations of whose descendants were to furnish each a noted journalist to New Orleans. I knew the younger of these in my boyhood as a man of, say, fifty. And there was young Frank Schuber, a good, strong-hearted, merry fellow who two years after became the husband of the younger Eva Kropp; he hailed from Strasburg; I have talked with his grandson. And lastly there were among the Langensoultz group two families named Müller.

The young brothers Henry and Daniel Müller were by birth Bavarians. They had married, in the Hillsler family, two sisters of Eva and Margaret. They had been known in the village as lockmaker Müller and shoemaker Müller. The wife of Daniel, the shoemaker, was Dorothea. Henry, the locksmith, and his wife had two sons, the elder ten years of age and named for his uncle Daniel, the shoemaker. Daniel and Dorothea had four children. The eldest was a little boy of eight years, the youngest was an infant, and between these were two little daughters, Dorothea and Salome.

And so the villagers were all bound closely together, as villagers are apt to be. Eva Kropp’s young daughter Eva was godmother to Salome. Frau Koelhoffer had lived on a farm about an hour’s walk from the Müllers and had not known them; but Frau Schultzheimer was a close friend, and had been a schoolmate and neighbor of Salome’s mother. The husband of her who was afterward Madame Fleikener was a nephew of the Müller brothers, Frank Schuber was her cousin, and so on.

II.

SIX MONTHS AT ANCHOR.

SETTING out thus by whole families and with brothers’ and sisters’ families on the right and on the left, we may safely say that, once the last kisses were given to those left behind and the last look taken of childhood’s scenes, they pressed forward brightly, filled with courage and hope. They were poor, but they were bound for a land where no soldier was going to snatch the beads and cross from the neck of a little child, as one of Napoleon’s had attempted to do to one of the Thomas children. They were on their way to golden America; through Philadelphia to the virgin lands of the great West. Early in August they reached Amsterdam. There they paid their passage in advance, and were carried out to the Helder, where, having laid in their provisions, they embarked and were ready to set sail.

But no sail was set. Word came instead that the person who had sold the ship had not been paid its price and had seized the vessel; the delays of the law threatened, when time was a matter of fortune or of ruin.

And soon came far worse tidings. The emigrants refused to believe them as long as there was room for doubt. Henry and Daniel Müller — for locksmith Müller, said Wagner twenty-seven years afterwards on the witness-stand, “was a brave man and was foremost in doing everything necessary to be done for the passengers” — went back to Amsterdam to see if such news could be true, and returned only to confirm despair. The man to whom the passage money of the two hundred families — nine hundred souls — had been paid had absconded.

They could go neither forward nor back. Days, weeks, months passed, and there still lay the great hulk teeming with its population and swinging idly at anchor; fathers gazing wistfully over the high bulwarks, mothers nursing their babes, and the children, Eva, Daniel, Henry, Andrew, Dorothea, Salome, and all the rest, by hundreds.

Salome was a pretty child, dark, as both her parents were, and looking much like her mother; having especially her black hair and eyes and her chin. Playing around with her was one little cousin, a girl of her own age, — that is, somewhere between three and five, — whose face was strikingly like Salome’s. It was she who in later life became Madame Karl Rouff, or, more familiarly, Madame Karl.

Provisions began to diminish, grew scanty, and at length were gone. The emigrants’ summer was turned into winter; it was now December. So pitiful did their case become that it forced the attention of the Dutch Government. Under its direction they were brought back to Amsterdam, where many of them, without goods, money, or even shelter, and strangers to the place and to the language, were reduced to beg for bread.

But by and by there came a word of great relief. The Government offered a reward of thirty thousand gilders — about twelve thousand dollars — to any merchant or captain of a vessel who would take them to America, and a certain Grandsteiner accepted the task. For a time he quartered them in Amsterdam, but by and by, with hearts revived, they began to go again on shipboard. This time there were three ships in place of the one; or two ships, and one of those old Dutch, flattish-bottomed, round-sided, two-masted crafts they called galiots. The number of ships was trebled — that was well; but the number of souls was doubled, and eighteen hundred wanderers from home were stowed in the three vessels.

III.

FAMINE AT SEA.

THESE changes made new farewells and separations. Common aims, losses, and sufferings had knit together in friendship many who had never seen each other until they met on the deck of the big Russian ship, and now not a few of these must part.

The first vessel to sail was one of the two ships, the Johanna Maria. Her decks were black with people: there were over six hundred of them. Among the number, waving farewell to the Kropps, the Koelhoffers, the Schultzheimers, to Frank Schuber and to the Müllers, stood the Thomases, Madame Fleikener, as we have to call her, and one whom we have not yet named, the jungfrau Hemin, of Würtemberg, just turning nineteen, of whom the little Salome and her mother had made a new, fast friend on the old Russian ship.

A week later the Captain Grone — that is, the galiot-hoisted the Dutch flag as the Johanna Maria had done, and started after her with other hundreds on her own deck, I know not how many, but making eleven hundred in the two, and including, for one, young Wagner. Then after two weeks more the remaining ship, the Johanna, followed, with Grandsteiner as supercargo, and seven hundred emigrants. Here were the Müllers and most of their relatives and fellow-villagers. Frank Schuber was among them, and was chosen steward for the whole shipful.

At last they were all off. But instead of a summer’s they were now to encounter a winter’s sea, and to meet it weakened and wasted by sickness and destitution. The first company had been out but a week when, on New Year’s night, a furious storm burst upon the crowded ship. With hatches battened down over their heads they heard and felt the great buffetings of the tempest, and by and by one great crash above all other noises as the mainmast went by the board. The ship survived; but when the storm was over and the people swarmed up once more into the pure ocean atmosphere and saw the western sun set clear, it set astern of the ship. Her captain had put her about and was steering for Amsterdam.

“She is too old,” the travelers gave him credit for saying, when long afterwards they testified in court; “too old, too crowded, too short of provisions, and too crippled, to go on such a voyage; I don’t want to lose my soul that way.” And he took them back.

They sailed again; but whether in another ship, or in the same with another captain, I have not discovered. Their sufferings were terrible. The vessel was foul. Fevers broke out among them. Provisions became scarce. There was nothing fit for the sick, who daily grew more numerous. Storms tossed them hither and yon. Water became so scarce that the sick died for want of it.

One of the Thomas children, a little girl of eight years, whose father lay burning with fever and moaning for water, found down in the dark at the back of one of the water-casks a place where once in a long time a drop of water fell from it. She placed there a small vial, and twice a day bore it, filled with water-drops, to the sick man. It saved his life. Of the three ship-loads only two families reached America whole, and one of these was the Thomases. A younger sister told me in 1884 that though the child lived to old age on the banks of the Mississippi River, she could never see water wasted and hide her anger.

The vessels were not bound for Philadelphia, as the Russian ship had been. Either from choice or of necessity the destination had been changed before sailing, and they were on their way to New Orleans.

That city was just then — the war of 1812-15 being so lately over-coming boldly into notice as commercially a strategic point of boundless promise. Steam navigation had hardly two years before won its first victory against the powerful current of the Mississippi, but it was complete. The population was thirty-three thousand; exports, thirteen million dollars. Capital and labor were crowding in, and legal, medical, and commercial talent were hurrying to the new field.

Scarcely at any time since has the New Orleans bar, in proportion to its numbers, had so many brilliant lights. Edward Livingston, of world-wide fame, was there in his prime. John R. Grymes, who died a few years before the opening of the late civil war, was the most successful man with juries who ever plead in Louisiana courts. We must meet him in the court-room by and by, and may as well make his acquaintance now. He was emphatically a man of the world. Many anecdotes of him remain, illustrative rather of intrepid shrewdness than of chivalry. He had been counsel for the pirate brothers Lafitte in their entanglements with the custom-house and courts, and was believed to have received a hundred thousand dollars from them as fees. Only old men remember him now. They say he never lifted his voice, but in tones that grew softer and lower the more the thought behind them grew intense would hang a glamour of truth over the veriest sophistries that intellectual ingenuity could frame. It is well to remember that this is only tradition, which can sometimes be as unjust as daily gossip. It is sure that he could entertain most showily. The young Duke of Saxe-WeimarEisenach, was once his guest. In his book of travels in America (1825-26) he says:

My first excursion [in New Orleans] was to visit Mr. Grymes, who here inhabits a large, massive, and splendidly furnished house.... In the evening we paid our visit to the governor of the State.... After this we went to several coffee-houses where the lower classes amuse themselves.... Mr. Grymes took me to the masked ball, which is held every evening during the carnival at the French theater.... The dress of the ladies I observed to be very elegant, but understood that most of those dancing did not belong to the better class of society.... At a dinner, which Mr. Grymes gave me with the greatest display of magnificence,... we withdrew from the first table, and seated ourselves at the second, in the same order in which we had partaken of the first. As the variety of wines began to set the tongues of the guests at liberty, the ladies rose, retired to another apartment, and resorted to music. Some of the gentlemen remained with the bottle, while others, among whom I was one, followed the ladies.... We had waltzing until 10 o’clock, when we went to the masquerade in the theater in St. Philip street.... The female company at the theater consisted of quadroons, who, however, were masked.

Such is one aspect given us by history of the New Orleans towards which that company of emigrants, first of the three that had left the other side, were toiling across the waters.

IV.

SOLD INTO BONDAGE.

THEY were fever-struck and famine-wasted. But February was near its end, and they were in the Gulf of Mexico. At that time of year its storms have lulled and its airs are the perfection of spring; March is a kind of May. And March came.

They saw other ships now every day; many of them going their way. The sight cheered them; the passage had been lonely as well as stormy. Their own vessels, of course, — the other two, — they had not expected to see, and had not seen. They did not know whether they were on the sea or under it.

At length pilot-boats began to appear. One came to them and put a pilot on board. Then the blue water turned green, and by and by yellow. A fringe of low land was almost right ahead. Other vessels were making for the same lighthouse towards which they were headed, and so drew constantly nearer to one another. The emigrants line the bulwarks, watching the nearest sails. One ship is so close that some can see the play of waters about her bows. And now it is plain that her bulwarks, too, are lined with emigrants who gaze across at them. She glides nearer, and just as the cry of recognition bursts from this whole company the other one yonder suddenly waves caps and kerchiefs and sends up a cheer. Their ship is the Johanna.

Do we dare draw upon fancy? We must not. The companies did meet on the water, near the Mississippi’s mouth, though whether first inside or outside the stream I do not certainly gather. But they met; not the two vessels only, but the three. They were towed up the river side by side, the Johanna here, the Captain Grone there, and the other ship between them. Wagner, who had sailed on the galiot, was still alive. Many years afterwards he testified:

“We all arrived at the Balize [the river’s mouth] the same day. The ships were so close we could speak to each other from on board our respective ships. We inquired of one another of those who had died and of those who still remained.”

Madame Fleikener said the same:

“We hailed each other from the ships and asked who lived and who had died. The father and mother of Madame Schuber [Kropp and his wife] told me Daniel Müller and family were on board.”

But they had suffered loss. Of the Johanna’s 700 souls only 430 were left alive. Henry Müller’s wife was dead. Daniel Müller’s wife, Dorothea, had been sick almost from the start; she was gone, with the babe at her bosom. Henry was left with his two boys, and Daniel with his one and his little Dorothea and Salome. Grandsteiner, the supercargo, had lived; but of 1800 homeless poor whom the Dutch king’s gilders had paid him to bring to America, foul ships and lack of food and water had buried 1200 in the sea.

The vessels reached port and the passengers prepared to step ashore, when to their amazement and dismay Grandsteiner laid the hand of the law upon them and told them they were “redemptioners.” A redemptioner was an emigrant whose services for a certain period were liable to be sold to the highest bidder for the payment of his passage to America. It seems that in fact a large number of those on board the Johanna had in some way really become so liable; but it is equally certain that of others, the Kropps, the Schultzheimers, the Koelhoffers, the Müllers, and so on, the transportation had been paid for in advance, once by themselves and again by the Government of Holland. Yet Daniel Müller and his children were among those held for their passage money.

Some influential German residents heard of these troubles and came to the rescue. Suits were brought against Grandsteiner, the emigrants remaining meanwhile on the ships. Mr. Grymes was secured as counsel in their cause; but on some account not now remembered by survivors scarce a week had passed before they were being sold as redemptioners. At least many were, including Daniel Müller and his children.

Then the dispersion began. The people were bound out before notaries and justices of the peace, singly and in groups, some to one, some to two years’ service, according to age. “They were scattered,” — so testified Frank Schuber twenty-five years afterwards, — “scattered about like young birds leaving a nest, without knowing anything of each other.” They were “taken from the ships,” says, the jungfrau Hemin, “and went here and there so that one scarcely knew where the other went.”

Many went no farther than New Orleans or its suburbs, but settled, some in and about the old rue Chartres — the Thomas family, for example; others in the then new faubourg Marigny, where Eva Kropp’s daughter, Salome’s young cousin Eva, for one, seems to have gone into domestic service. Others, again, were taken out to plantations near the city; Madame Fleikener to the well-known estate of Maunsell White, Madame Schultzheimer to the locally famous Hopkins plantation, and so on.

But others were carried far away; some, it is said, even to Alabama. Madame Hemin was taken a hundred miles up the river, to Baton Rouge, and Henry Müller and his two little boys went on to Bayou Sara, and so up beyond the State’s border and a short way into Mississippi.

When all his relatives were gone Daniel Müller was still in the ship with his little son and daughters. Certainly he was not a very salable redemptioner with his three little motherless children about his knees. But at length, some fifteen days after the arrival of the ships, Frank Schuber met him on the old customhouse wharf with his little ones and was told by him that he, Müller, was going to Attakapas. About the same time, or a little later, Müller came to the house where young Eva Kropp, afterwards Schuber’s wife, dwelt, to tell her good-bye. She begged to be allowed to keep Salome. During the sickness of the little one’s mother and after the mother’s death she had taken constant maternal care of the pretty, black-eyed, olive-skinned godchild. But Müller would not leave her behind.

V.

THE LOST ORPHANS.

THE prospective journey was the same that we saw Suzanne and Françoise, Joseph and Alix, take with toil and danger, yet with so much pleasure, in 1795. The early company went in a flatboat; these went in a round-bottom boat. The journey of the latter was probably the shorter. Its adventures have never been told, save one line. When several weeks afterwards the boat returned, it brought word that Daniel Müller had one day dropped dead on the deck and that his little son had fallen overboard and was drowned. The little girls had presumably been taken on to their destination by whoever had been showing the way; but that person’s name and residence, if any of those left in New Orleans had known them, were forgotten. Only the wide and almost trackless region of Attakapas was remembered, and by people to whom every day brought a struggle for their own existence. Besides, the children’s kindred were bound as redemptioners.

Those were days of rapid change in New Orleans. The redemptioners worked their way out of bondage into liberty. At the end of a year or two those who had been taken to plantations near by returned to the city. The town was growing, but the upper part of the river front in faubourg Ste. Marie, now in the heart of the city, was still lined with brick-yards, and thitherward cheap houses and opportunities for market gardening drew the emigrants. They did not colonize, however, but merged into the community about them, and only now and then, casually, met one another. Young Schuber was an exception; he throve as a butcher in the old French market, and courted and married the young Eva Kropp. When the fellow-emigrants occasionally met, their talk was often of poor shoemaker Müller and his lost children.

No clear tidings of them came. Once the children of some Germans who had driven cattle from Attakapas to sell them in the shambles at New Orleans corroborated to Frank Schuber the death of the father; but where Salome and Dorothea were they could not say, except that they were in Attakapas.

Frank and Eva were specially diligent inquirers after Eva’s lost godchild; as also was Henry Müller up in or near Woodville, Mississippi. He and his boys were, in their small German way, prospering. He made such effort as he could to find the lost children. One day in the winter of 1820-21 he somehow heard that there were two orphan children named Miller — the Müllers were commonly called Miller — in the town of Natchez, some thirty-five miles away on the Mississippi. He bought a horse and wagon, and, leaving his own children, set out to rescue those of his dead brother. About midway on the road from Woodville to Natchez the Homochitto Creek runs through a swamp which in winter overflows. In here Müller lost his horse. But, nothing daunted, he pressed on, only to find in Natchez the trail totally disappear.

Again, in the early spring of 1824, a man driving cattle from Attakapas to Bayou Sara told him of two little girls named Müller living in Attakapas. He was planning another and bolder journey in search of them, when he fell ill; and at length, without telling his sons, if he knew, where to find their lost cousins, he too died.

Years passed away. Once at least in nearly every year young Daniel Miller — the “u” was dropped — of Woodville came down to New Orleans. At such times he would seek out his relatives and his father’s and uncle’s old friends and inquire for tidings of the lost children. But all in vain. Frank and Eva Schuber too kept up the inquiry in his absence, but no breath of tidings came. On the city’s south side sprung up the new city of Lafayette, now the Fourth District of New Orleans, and many of the aforetime redemptioners moved thither. Its streets near the river became almost a German quarter. Other German immigrants, hundreds and hundreds, landed among them and in the earlier years many of these were redemptioners. Among them one whose name will always be inseparable from the history of New Orleans has a permanent place in this story.

VI.

CHRISTIAN ROSELIUS.

ONE morning many years ago, when some business had brought me into a corridor of one of the old court buildings facing the Place d’Armes, a loud voice from within one of the court-rooms arrested my own and the general ear. At once from all directions men came with decorous haste towards the spot whence it proceeded. I pushed in through a green door into a closely crowded room and found the Supreme Court of the State in session. A short, broad, big-browed man of an iron sort, with silver hair close shorn from a Roman head, had just begun his argument in the final trial of a great case that had been before the court for many years, and the privileged seats were filled with the highest legal talent, sitting to hear him. It was a famous will case, and I remember that he was quoting from “King Lear” as I entered.

“Who is that?” I asked of a man packed against me in the press.

“Roselius,” he whispered; and the name confirmed my conjecture: the speaker looked like all I had once heard about him. Christian Roselius came from Brunswick, Germany, a youth of seventeen, something more than two years later than Salome Müller and her friends. Like them he came an emigrant under the Dutch flag, and like them his passage was paid in New Orleans by his sale as a redemptioner. A printer bought his services for two years and a half. His story is the good old one of courage, self-imposed privations, and rapid development of talents. From printing he rose to journalism, and from journalism passed to the bar. By 1836, at thirty-three years of age, he stood in the front rank of that brilliant group where Grymes was still at his best. Before he was forty he had been made attorney-general of the State. Punctuality, application, energy, temperance, probity, bounty, were the strong features of his character. It was a common thing for him to give his best services free in the cause of the weak against the strong. As an adversary he was decorous and amiable, but thunderous, heavy-handed, derisive if need be, and inexorable. A time came for these weapons to be drawn in defense of Salome Müller.

VII.

MILLER versus BELMONTI.

IN 1843 Frank and Eva Schuber had moved to a house on the corner of Jackson and Annunciation streets . They had brought up sons, two at least, who were now old enough to be their father’s mainstay in his enlarged business of “farming” (leasing and subletting) the Poydras market. The father and mother and their kindred and companions in long past misfortunes and sorrows had grown to wealth and stand ing among the German-Americans of New Orleans and Lafayette. The little girl cousin of Salome Müller, who as a child of the same age had been her playmate on shipboard at the Helder and in crossing the Atlantic, and who looked so much like Salome, was a woman of thirty, the wife of Karl Rouff.

One summer day she was on some account down near the lower limits of New Orleans on or near the river front, where the population was almost wholly a lower class of Spanish people. Passing an open door her eye was suddenly arrested by a woman of about her own age engaged in some humble service within with her face towards the door.

Madame Karl paused in astonishment. The place was a small drinking-house, a mere cabaret; but the woman! It was as if her aunt Dorothea, who had died on the ship twenty-five years before, stood face to face with her alive and well. There were her black hair and eyes, her olive skin, and the old, familiar expression of countenance that belonged so distinctly to all the Hillsler family. Madame Karl went in.

“My name,” the woman replied to her question, “is Mary.” And to another question, “No; I am a yellow girl. I belong to Mr. Louis Belmonti, who keeps this ‘coffee-house.’ He has owned me for four or five years. Before that? Before that, I belonged to Mr. John Fitz Müller, who has the saw-mill down here by the convent. I always belonged to him.” Her accent was the one common to English-speaking slaves.

But Madame Karl was not satisfied. “You are not rightly a slave. Your name is Müller. You are of pure German blood. I knew your mother. I know you. We came to this country together on the same ship, twenty-five years ago.”

“No,” said the other; “you must be mistaking me for some one else that I look like.”

But Madame Karl: “Come with me. Come up into Lafayette and see if I do not show you to others who will know you the moment they look at you.”

The woman enjoyed much liberty in her place and was able to accept this invitation. Madame Karl took her to the home of Frank and Eva Schuber.

Their front door steps were on the street. As Madame Karl came up to them Eva stood in the open door much occupied with her approach, for she had not seen her for two years. Another woman, a stranger, was with Madame Karl. As they reached the threshold and the two old-time friends exchanged greetings, Eva said:

“Why, it is two years since last I saw you. Is that a German woman? — I know her!”

“Well,” said Madame Karl, “if you know her, who is she?”

“My God!” cried Eva, — “the long-lost Salome Müller!”

“I needed nothing more to convince me,” she afterwards testified in court. “I could recognize her among a hundred thousand persons.”

Frank Schuber came in, having heard nothing. He glanced at the stranger, and turning to his wife asked:

“Is not that one of the girls who was lost?”

“It is,” replied Eva; “it is. It is Salome Müller!”

On that same day, as it seems, for the news had not reached them, Madame Fleikener and her daughter — they had all become madams in Creole America — had occasion to go to see her kinswoman, Eva Schuber. She saw the stranger and instantly recognized her, “because of her resemblance to her mother.”

They were all overjoyed. For twenty-five years dragged in the mire of African slavery, the mother of quadroon children and ignorant of her own identity, they nevertheless welcomed her back to their embrace, not fearing, but hoping, she was their long-lost Salome.

But another confirmation was possible, far more conclusive than mere recognition of the countenance. Eva knew this. For weeks together she had bathed and dressed the little Salome every day. She and her mother and all Henry Müller’s family had known, and had made it their common saying, that it might be difficult to identify the lost Dorothea were she found; but if ever Salome were found they could prove she was Salome beyond the shadow of a doubt. It was the remembrance of this that moved Eva Schuber to say to the woman:

“Come with me into this other room.” They went, leaving Madame Karl, Madame Fleikener, her daughter, and Frank Schuber behind. And when they returned the slave was convinced, with them all, that she was the younger daughter of Daniel and Dorothea Müller. We shall presently see what fixed this conviction.

The next step was to claim her freedom. She appears to have gone back to Belmonti, but within a very few days, if not immediately, Madame Schuber and a certain Mrs. White — who does not become prominent — followed down to the cabaret. Mrs. White went out somewhere on the premises, found Salome at work, and remained with her, while Madame Schuber confronted Belmonti, and, revealing Salome’s identity and its proofs, demanded her instant release.

Belmonti refused to let her go. But while doing so he admitted his belief that she might be of pure white blood and of right entitled to freedom. He confessed having gone back to John F. Müller soon after buying her and proposing to set her free; but Müller, he said, had replied that in such a case the law required her to leave the country. Thereupon Belmonti had demanded that the sale be rescinded, saying: “I have paid you my money for her.”

“But,” said Müller, “I did not sell her to you as a slave. She is as white as you or I, and neither of us can hold her if she chooses to go away.”

Such at least was Belmonti’s confession, yet he was as far from consenting to let his captive go after this confession was made as he had been before. He seems actually to have kept her for a while; but at length she went boldly to Schuber’s house, became one of his household, and with his advice and aid asserted her intention to establish her freedom by an appeal to law. Belmonti replied with threats of public imprisonment, the chain-gang, and the auctioneer’s block.

Salome, or Sally, for that seems to be the nickname by which her kindred remembered her, was never to be sold again; but not many months were to pass before she was to find herself, on her own petition and bond of $500, a prisoner, by the only choice the laws allowed her, in the famous calaboose, not as a criminal, but as sequestered goods in a sort of sheriff’s warehouse. Says her petition: “Your petitioner has good reason to believe that the said Belmonti intends to remove her out of the jurisdiction of the court during the pendency of the suit”; wherefore not he but she went to jail. Here she remained for six days and was then allowed to go at large, but only upon giving still another bond and security, and in a much larger sum than she had ever been sold for.

The original writ of sequestration lies before me as I write, indorsed as follows:

Received 24th January, 1844, and on the 26th of the same month sequestered the body of the plaintiff and committed her to prison for safe keeping; but on the 1st February, 1844, she was released from custody, having entered bond in the sum of one thousand dollars with Francis Schuber as the security conditioned according to law, and which bond is herewith returned this 3d February, 1844.

B.F. Lewis, d’y sh’ff.

Inside is the bond with the signatures, Frantz Schuber in German script, and above in English,

Also the writ, ending in words of strange and solemn irony: “In the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and forty-four and in the sixty-eighth year of the Independence of the United States.”

We need not follow the history at the slow gait of court proceedings. At Belmonti’s petition John F. Miller was called in warranty; that is, made the responsible party in Belmonti’s stead. There were “prayers” and rules, writs and answers, as the cause slowly gathered shape for final contest. Here are papers of date February 24 and 29 — it was leap year — and April 1, 2, 8, and 27. On the 7th of May Frank Schuber asked leave, and on the 14th was allowed, to substitute another bondsman in his place in order that he himself might qualify as a witness; and on the 23d of May the case came to trial.

VIII.

THE TRIAL.

IT had already become famous. Early in April the press of the city, though in those days unused to giving local affairs more than the feeblest attention, had spoken of this suit as destined, if well founded, to develop a case of “unparalleled hardship, cruelty, and oppression.” The German people especially were aroused and incensed. A certain newspaper spoke of the matter as the case “that had for several days created so much excitement throughout the city.” The public sympathy was with Salome.

But by how slender a tenure was it held! It rested not on the “hardship, cruelty, and oppression” she had suffered for twenty years, but only on the fact, which she might yet fail to prove, that she had suffered these things without having that tincture of African race which, be it ever so faint, would entirely justify, alike in the law and in the popular mind, treatment otherwise counted hard, cruel, oppressive, and worthy of the public indignation.

And now to prove the fact. In a newspaper of that date appears the following:

This cause came on to-day for trial before the court, Roselius and Upton for plaintiff, Canon for defendant, Grymes and Micou for warrantor; when after hearing evidence the same is continued until to-morrow morning at 11 o’clock.

Salome’s battle had begun. Besides the counsel already named, there were on the slave’s side a second Upton and a Bonford, and on the master’s side a Sigur, a Caperton, and a Lockett. The redemptioners had made the cause their own and prepared to sustain it with a common purse.

Neither party had asked for a trial by jury; the decision was to come from the bench.

The soldier, in the tableaux of Judge Buchanan’s life, had not dissolved perfectly into the justice, and old lawyers of New Orleans remember him rather for unimpeachable integrity than for fine discrimination, a man of almost austere dignity, somewhat quick in temper.

Before him now gathered the numerous counsel, most of whose portraits have long since been veiled and need not now be uncovered. At the head of one group stood Roselius, at the head of the other, Grymes. And for this there were good reasons. Roselius, who had just ceased to be the State’s attorney-general, was already looked upon as one of the readiest of all champions of the unfortunate. He was in his early prime, the first full spread of his powers, but he had not forgotten the little Dutch brig Jupiter, or the days when he was himself a redemptioner. Grymes, on the other side, had had to do — as we have seen — with these same redemptioners before. The uncle and the father of this same Sally Miller, so called, had been chief witnesses in the suit for their liberty and hers, which he had — blamelessly, we need not doubt — lost some twenty-five years before. Directly in consequence of that loss Salome had gone into slavery and disappeared. And now the loser of that suit was here to maintain that slavery over a woman who, even if she should turn out not to be the lost child, was enough like to be mistaken for her. True, causes must have attorneys, and such things may happen to any lawyer; but here was a cause which in our lights to-day, at least, had on the defendant’s side no moral right to come into court.

One other person, and only one, need we mention. Many a New York City lawyer will recall in his reminiscences of thirty years ago a small, handsome, gold-spectacled man with brown hair and eyes, noted for scholarship and literary culture; a brilliant pleader at the bar, and author of two books that became authorities, one on trade-marks, the other on prize law. Even some who do not recollect him by this description may recall how the gifted Frank Upton — for it is of him I write — was one day in 1863 or 1864 struck down by apoplexy while pleading in the well-known Peterhoff case. Or they may remember subsequently his constant, pathetic effort to maintain his old courtly mien against his resultant paralysis. This was the young man of about thirty, of uncommon masculine beauty and refinement, who sat beside Christian Roselius as an associate in the cause of Sally Miller versus Louis Belmonti.

IX.

THE EVIDENCE.

WE need not linger over the details of the trial. The witnesses for the prosecution were called. First came a Creole woman, so old that she did not know her own age, but was a grown-up girl in the days of the Spanish governor — general Galvez, sixty-five years before. She recognized in the plaintiff the same person whom she had known as a child in John F. Miller’s domestic service with the mien, eyes, and color of a white person and with a German accent. Next came Madame Hemin, who had not known the Müllers till she met them on the Russian ship and had not seen Salome since parting from them at Amsterdam, yet who instantly identified her “when she herself came into the court-room just now.” “Witness says,” continues the record, “she perceived the family likeness in plaintiff’s face when she came in the door.”

The next day came Eva and told her story; and others followed, whose testimony, like hers, we have anticipated. Again and again was the plaintiff recognized, both as Salome and as the girl Mary, or Mary Bridget, who for twenty years and upward had been owned in slavery, first by John F. Miller, then by his mother, Mrs. Canby, and at length by the cabaret keeper Louis Belmonti. If the two persons were but one, then for twenty years at least she had lived a slave within five miles, and part of the time within two, of her kindred and of freedom.

That the two persons were one it seemed scarcely possible to doubt. Not only did every one who remembered Salome on shipboard recognize the plaintiff as she, but others, who had quite forgotten her appearance then, recognized in her the strong family likeness of the Müllers. This likeness even witnesses for the defense had to admit. So, on Salome’s side, testified Madame Koelhoffer, Madame Schultzheimer, and young Daniel Miller (Müller) from Mississippi. She was easily pointed out in the throng of the crowded court-room.

And then, as we have already said, there was another means of identification which it seemed ought alone to have carried with it overwhelming conviction. But this we still hold in reserve until we have heard the explanation offered by John F. Miller both in court and at the same time in the daily press in reply to its utterances which were giving voice to the public sympathy for Salome.

It seems that John Fitz Miller was a citizen of New Orleans in high standing, a man of property, money, enterprises, and slaves. John Lawson Lewis, commanding-general of the State militia, testified in the case to Mr. Miller’s generous and social disposition, his easy circumstances, his kindness to his eighty slaves, his habit of entertaining, and the exceptional fineness of his equipage. Another witness testified that complaints were sometimes made by Miller’s neighbors of his too great indulgence of his slaves. Others, ladies as well as gentlemen, corroborated these good reports, and had even kinder and higher praises for his mother, Mrs. Canby. They stated with alacrity, not intending the slightest imputation against the gentleman’s character, that he had other slaves even fairer of skin than this Mary Bridget, who nevertheless, “when she was young,” they said, “looked like a white girl.” One thing they certainly made plain — that Mr. Miller had never taken the Müller family or any part of them to Attakapas or knowingly bought a redemptioner.

He accounted for his possession of the plaintiff thus: In August, 1822, one Anthony Williams, being or pretending to be a negro-trader and from Mobile, somehow came into contact with Mr. John Fitz Miller in New Orleans. He represented that he had sold all his stock of slaves except one girl, Mary Bridget, ostensibly twelve years old, and must return at once to Mobile. He left this girl with Mr. Miller to be sold for him for his (Williams’s) account under a formal power of attorney so to do, Mr. Miller handing him one hundred dollars as an advance on her prospective sale. In January, 1823, Williams had not yet been heard from, nor had the girl been sold; and on the 1st of February Mr. Miller sold her to his own mother, with whom he lived — in other words, to himself, as we shall see. In this sale her price was three hundred and fifty dollars and her age was still represented as about twelve. “From that time she remained in the house of my mother,” wrote Miller to the newspapers, “as a domestic servant” until 1838, when “she was sold to Belmonti.”

Mr. Miller’s public statement was not as full and candid as it looked. How, if the girl was sold to Mrs. Canby, his mother — how is it that Belmonti bought her of Miller himself? The answer is that while Williams never re-appeared, the girl, in February, 1835, “the girl Bridget,” now the mother of three children, was with these children bought back again by that same Mr. Miller from the entirely passive Mrs. Canby, for the same three hundred and fifty dollars; the same price for the four which he had got, or had seemed to get, for the mother alone when she was but a child of twelve years. Thus had Mr. Miller become the owner of the woman, her two sons, and her daughter, had had her service for the keeping, and had never paid but one hundred dollars. This point he prudently overlooked in his public statement. Nor did he count it necessary to emphasize the further fact that when this slave-mother was about twenty-eight years old and her little daughter had died, he sold her alone, away from her two half-grown sons, for ten times what he had paid for her, to be the bond-woman of the wifeless keeper of a dram-shop.

But these were not the only omissions. Why had Williams never come back either for the slave or for the proceeds of her sale? Mr. Miller omitted to state, what he knew well enough, that the girl was so evidently white that Williams could not get rid of her, even to him, by an open sale. When months and years passed without a word from Williams, the presumption was strong that Williams knew the girl was not of African tincture, at least within the definition of the law, and was content to count the provisional transfer to Miller equivalent to a sale.

Miller, then, was — heedless enough, let us call it — to hold in African bondage for twenty years a woman who, his own witnesses testified, had every appearance of being a white person, without ever having seen the shadow of a title for any one to own her, and with everything to indicate that there was none. Whether he had any better right to own the several other slaves whiter than this one whom those same witnesses of his were forward to state he owned and had owned, no one seems to have inquired. Such were the times; and it really was not then remarkable that this particular case should involve a lady noted for her good works and a gentleman who drove “the finest equipage in New Orleans.”

One point, in view of current beliefs of to-day, compels attention. One of Miller’s witnesses was being cross-examined. Being asked if, should he see the slave woman among white ladies, he would not think her white, he replied:

“I cannot say. There are in New Orleans many white persons of dark complexion and many colored persons of light complexion.” The question followed:

“What is there in the features of a colored person that designates them to be such?”

“I cannot say. Persons who live in countries where there are many colored persons acquire an instinctive means of judging that cannot be well explained.”

And yet neither this man’s “instinct” nor that of any one else, either during the whole trial or during twenty years’ previous knowledge of the plaintiff, was of the least value to determine whether this poor slave was entirely white or of mixed blood. It was more utterly worthless than her memory. For as to that she had, according to one of Miller’s own witnesses, in her childhood confessed a remembrance of having been brought “across the lake”; but whether that had been from Germany, or only from Mobile, must be shown in another way. That way was very simple, and we hold it no longer in suspense.

X.

THE CROWNING PROOF.

“IF ever our little Salome is found,” Eva Kropp had been accustomed to say, “we shall know her by two hair moles about the size of a coffee-bean, one on the inside of each thigh, about midway up from the knee. Nobody can make those, or take them away without leaving the tell-tale scars.” And lo! when Madame Karl brought Mary Bridget to Frank Schuber’s house, and Eva Schuber, who every day for weeks had bathed and dressed her godchild on the ship, took this stranger into another room apart and alone, there were the birth-marks of the lost Salome.

This incontestable evidence the friends of Salome were able to furnish, but the defense called in question the genuineness of the marks.

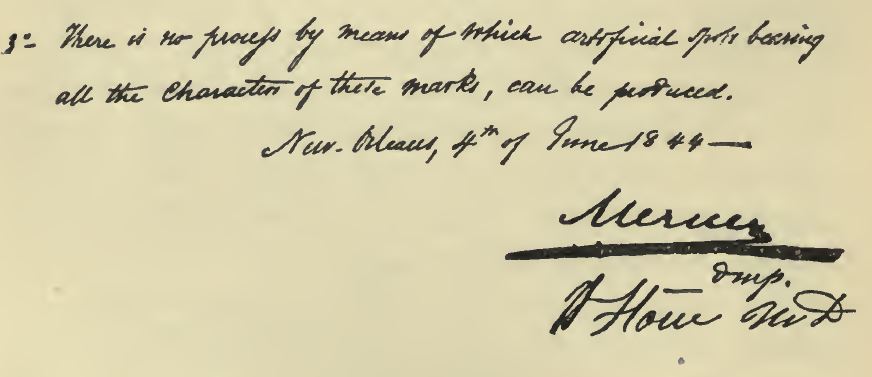

The verdict of science was demanded, and an order of the court issued to two noted physicians, one chosen by each side, to examine these marks and report “the nature, appearance, and cause of the same.” The kindred of Salome chose Warren Stone, probably the greatest physician and surgeon in one that New Orleans has ever known. Mr. Grymes’s client chose a Creole gentleman almost equally famed, Dr. Armand Mercier.

Dr. Stone died many years ago; Dr. Mercier, if I remember aright, in 1885. When I called upon Dr. Mercier in his office in Girod street in the summer of 1883, to appeal to his remembrance of this long-forgotten matter, I found a very noble-looking, fair old gentleman whose abundant waving hair had gone all to a white silken floss with age. He sat at his desk in persistent silence with his strong blue eyes fixed steadfastly upon me while I slowly and carefully recounted the story. Two or three times I paused inquiringly; but he faintly shook his head in the negative, a slight frown of mental effort gathering for a moment between the eyes that never left mine. But suddenly he leaned forward and drew his breath as if to speak. I ceased, and he said:

“My sister, the wife of Pierre Soulé, refused to become the owner of that woman and her three children because they were so white!” He pressed me eagerly with an enlargement of his statement, and when he paused I said nothing or very little; for, sad to say, he had only made it perfectly plain that it was not the girl Mary Bridget whom he was recollecting, but another case.

He did finally, though dimly, call to mind having served with Dr. Stone in such a matter as I had described. But later I was made independent of his powers of recollection, when the original documents of the court were laid before me. There was the certificate of the two physicians. And there, over their signatures, “Mercier d.m.p.” standing first, in a bold heavy hand underscored by a single broad quill-stroke, was this “Conclusion”:

“1. These marks ought to be considered as nœvi materni.

“2. They are congenital; or, in other words, the person was born with them.

“3. There is no process by means of which artificial spots bearing all the character of the marks can be produced.”

XI.

JUDGMENT.

ON the 11th of June the case of Sally Miller ver Louis Belmonti was called up again and the report of the medical experts received. Could anything be offered by Mr. Grymes and his associates to offset that? Yes; they had one last strong card, and now they played it.

It was, first, a certificate of baptism of a certain Mary’s child John, offered in evidence to prove that this child was born at a time when Salome Müller, according to the testimony of her own kindred, was too young by a year or two to become a mother; and secondly, the testimony of a free woman of color, that to her knowledge that Mary was this Bridget or Sally, and the child John this woman’s eldest son Lafayette. And hereupon the court announced that on the morrow it would hear the argument of counsel.

Salome’s counsel besought the court for a temporary postponement on two accounts: first, that her age might be known beyond a peradventure by procuring a copy of her own birth record from the official register of her native Langensoultz, and also to procure in New Orleans the testimony of one who was professionally present at the birth of her son, and who would swear that it occurred some years later than the date of the baptismal record just accepted as evidence.

“We are taken by surprise,” exclaimed in effect Roselius and his coadjutors, “in the production of testimony by the opposing counsel openly at variance with earlier evidence accepted from them and on record. The act of the sale of this woman and her children from Sarah Canby to John Fitz Miller in 1835, her son Lafayette being therein described as but five years of age, fixes his birth by irresistible inference in 1830, in which year by the recorded testimony of her kindred Salome Müller was fifteen years old.”

But the combined efforts of Roselius, Upton, and others were unavailing, and the newspapers of the following day reported: “This cause, continued from yesterday, came on again to-day, when, after hearing arguments of counsel, the court took the same under consideration.”

It must be a dull fancy that will not draw for itself the picture, when a fortnight later the frequenters of the court-room hear the word of judgment. It is near the end of the hot far-southern June. The judge begins to read aloud. His hearers wait languidly through the prolonged recital of the history of the case. It is as we have given it here: no use has been made here of any testimony discredited in the judge’s reasons for his decision. At length the evidence is summed up and every one attends to catch the next word. The judge reads:

“The supposed identity is based upon two circumstances: first, a striking resemblance of plaintiff to the child above mentioned and to the family of that child. Second, two certain marks or moles on the inside of the thighs [one on each thigh], which marks are similar in the child and in the woman. This resemblance and these marks are proved by several witnesses. Are they sufficient to justify me in declaring the plaintiff to be identical with the German child in question? I answer this question in the negative.”

What stir there was in the room when these words were heard the silent records lying before me do not tell, or whether all was silent while the judge read on; but by and by his words were these:

“I must admit that the relatives of the said family of redemptioners seem to be very firmly convinced of the identity which the plaintiff claims.... As, however, it is quite out of the question to take away a man’s property upon grounds of this sort, I would suggest that the friends of the plaintiff, if honestly convinced of the justice of her pretensions, should make some effort to settle à l’aimable with the defendant, who has honestly and fairly paid his money for her. They would doubtless find him well disposed to part on reasonable terms with a slave from whom he can scarcely expect any service after what has passed. Judgment dismissing the suit with costs.”

The white slave was still a slave. We are left to imagine the quiet air of dispatch with which as many of the counsel as were present gathered up any papers they may have had, exchanged a few murmurous words with their clients, and, hats in hand, hurried off and out to other business. Also the silent, slow dejection of Salome, Eva, Frank, and their neighbors and kin — if so be, that they were there — as they rose and left the hall where a man’s property was more sacred than a woman’s freedom. But the attorney had given them ground of hope. Application would be made for a new trial; and if this was refused, as it probably would be, then appeal would be made to the Supreme Court of the State.

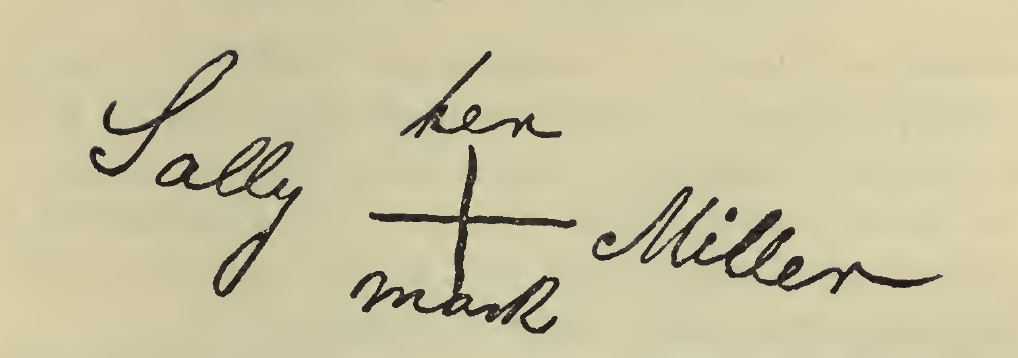

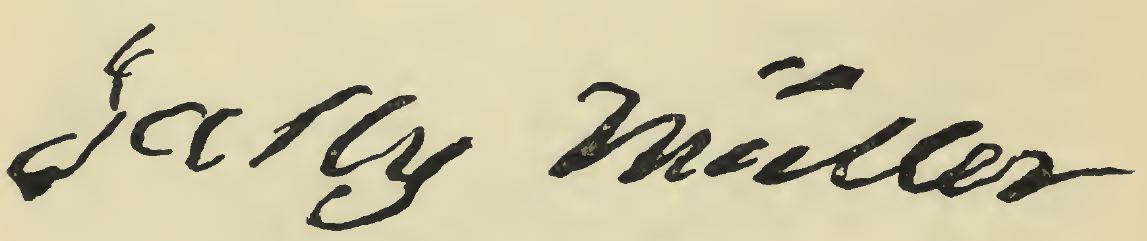

So it happened. Only two days later the plaintiff, through one of her counsel, the brother of Frank Upton, applied for a new trial. She stated that important evidence not earlier obtainable had come to light; that she could produce a witness to prove that John F. Miller had repeatedly said she was white; and that one of Miller’s own late witnesses, his own brother-in-law, would make deposition of the fact, recollected only since he gave testimony, that the girl Bridget brought into Miller’s household in 1822 was much darker than the plaintiff and died a few years afterwards. And this witness did actually make such deposition. In the six months through which the suit had dragged since Salome had made her first petition to the court and signed it with her mark she had learned to write. The application for a new trial is signed —

The new trial was refused. Roselius took an appeal. The judge “allowed” it, fixing the amount of Salome’s bond at $2000. Frank Schuber gave the bond and the case went up to the Supreme Court.

In that court no witnesses were likely to be examined. New testimony was not admissible; all testimony taken in the inferior courts “went up” by the request of either party as part of the record, and to it no addition could ordinarily be made. The case would be ready for argument almost at once.

XII.

BEFORE THE SUPREME COURT.

ONCE more it was May, when in the populous but silent court-room the clerk announced the case of Miller versus Louis Belmonti, and John F. Miller, warrantor. Well-nigh a year had gone by since the appeal was taken. Two full years had passed since Madame Karl had found Salome in Belmonti’s cabaret. It was now 1845; Grymes was still at the head of one group of counsel, and Roselius of the other. There again were Eva and Salome, looking like an elder and a younger sister. On the bench sat at the right two and at the left two associate judges, and between them in the middle the learned and aged historian of the State, Chief-Justice Martin.

The attorneys had known from the first that the final contest would be here, and had saved their forces for this; and when on the 19th of May the deep, rugged voice of Roselius resounded through the old Cabildo, a nine-days’ contest of learning, eloquence, and legal tactics had begun. Roselius may have filed a brief, but I have sought it in vain, and his words in Salome’s behalf are lost. Yet we know one part in the defense which he must have retained to himself; for Francis Upton was waiting in reserve to close the argument on the last day of the trial, and so important a matter as this that we shall mention would hardly have been trusted in any but the strongest hands. It was this: Roselius, in the middle of his argument upon the evidence, proposed to read a certain certified copy of a registry of birth. Grymes and his colleagues instantly objected. It was their own best gun captured and turned upon them. They could not tolerate it. It was no part of the record, they stoutly maintained, and must not be introduced nor read nor commented upon. The point was vigorously argued on both sides; but when Roselius appealed to an earlier decision of the same court the bench decided that, as then, so now, “in suits for freedom, and in favorem libertatis, they would notice facts which come credibly before them, even though they be dehors the record.” And so Roselius thundered it out. The consul for Baden at New Orleans had gone to Europe some time before, and was now newly returned. He had brought an official copy, from the records of the prefect of Salome’s native village, of the registered date of her birth. This is what was now heard, and by it Salome and her friends knew to their joy, and Belmonti to his chagrin, that she was two years older than her kinsfolk had thought her to be.

Who followed Roselius is not known, but by and by men were bending the ear to the soft persuasive tones and finished subtleties of the polished and courted Grymes. He left, we are told, no point unguarded, no weapon unused, no vantage-ground unoccupied. The high social standing and reputation of his client were set forth at their best. Every slenderest discrepancy of statement between Salome’s witnesses was ingeniously expanded. By learned citation and adroit appliance of the old Spanish laws concerning slaves, he sought to ward off as with a Toledo blade the heavy blows by which Roselius and his colleagues endeavored to lay upon the defendants the burden of proof which the lower court had laid upon Salome. He admitted generously the entire sincerity of Salome’s kinspeople in believing plaintiff to be the lost child; but reminded the court of the credulity of ill-trained minds, the contagiousness of fanciful delusions, and especially of what he somehow found room to call the inflammable imagination of the German temperament. He appealed to history; to the scholarship of the bench; citing the stories of Martin Guerre, the Russian Demetrius, Perkin Warbeck, and all the other wonderful cases of mistaken or counterfeited identity. Thus he and his associates pleaded for the continuance in bondage of a woman whom their own fellow-citizens were willing to take into their houses after twenty years of degradation and infamy, make their oath to her identity, and pledge their fortunes to her protection as their kinswoman.

Day after day the argument continued. At length the Sabbath broke its continuity, but on Monday it was resumed, and on Tuesday Francis Upton rose to make the closing argument for the plaintiff. His daughter, Miss Upton, now of Washington, once did me the honor to lend me a miniature of him made about the time of Salome’s suit for freedom. It is a pleasing evidence of his modesty in the domestic circle — where masculine modesty is rarest — that his daughter had never heard him tell the story of this case, in which, it is said, he put the first strong luster on his fame. In the picture he is a very David — “ruddy and of a fair countenance”; a countenance at once gentle and valiant, vigorous and pure. Lifting this face upon the wrinkled chief-justice and associate judges, he began to set forth the points of law, in an argument which, we are told, “was regarded by those who heard it as one of the happiest forensic efforts ever made before the court.”

He set his reliance mainly upon two points: one, that, it being obvious and admitted that plaintiff was not entirely of African race, the presumption of law was in favor of liberty and with the plaintiff, and therefore that the whole burden of proof was upon the defendants, Belmonti and Miller; and the other point, that the presumption of freedom in such a case could be rebutted only by proof that she was descended from a slave mother. These points the young attorney had to maintain as best he could without precedents fortifying them beyond attack; but “Adele versus Beauregard” he insisted firmly established the first point and implied the court’s assent to the second, while as legal doctrines “Wheeler on Slavery” upheld them both. When he was done Salome’s fate was in the hands of her judges.

Almost a month goes by before their judgment is rendered. But at length, on the 21st of June, the gathering with which our imagination has become familiar appears for the last time. The chief-justice is to read the decision from which there can be no appeal. As the judges take their places one seat is left void; it is by reason of sickness. Order is called, silence falls, and all eyes are on the chief-justice.

He reads. To one holding the court’s official copy of judgment in hand, as I do at this moment, following down the lines as the justice’s eyes once followed them, passing from paragraph to paragraph, and turning the leaves as his hand that day turned them, the scene lifts itself before the mind’s eye despite every effort to hold it to the cold letter of the time-stained files of the court. In a single clear, well-compacted paragraph the court states Salome’s claim and Belmonti’s denial; in another, the warrantor Miller’s denial and defense; and in two lines more, the decision of the lower court. And now?

“The first inquiry,” so reads the chief-justice — “the first inquiry that engages our attention is, What is the color of the plaintiff?”

But this is far from bringing dismay to Salome and her friends. For hear what follows:

“Persons of color” — meaning of mixed blood, not pure negro — “are presumed to be free.... The burden of proof is upon him who claims the colored person as a slave.... In the highest courts of the State of Virginia ... a person of the complexion of the plaintiff, without evidence of descent from a slave mother, would be released even on habeas corpus.... Not only is there no evidence of her [plaintiff] being descended from a slave mother, or even a mother of the African race, but no witness has ventured a positive opinion that she is of that race.”

Glad words for Salome and her kindred. The reading proceeds: “The presumption is clearly in favor of the plaintiff.” But suspense returns, for — “It is next proper,” the reading still goes on, “to inquire how far that presumption has been weakened or justified or repelled by the testimony of numerous witnesses in the record.... If a number of witnesses had sworn” — here the justice turns the fourth page; now he is in the middle of it, yet all goes well; he is making a comparison of testimony for and against, unfavorable to that which is against. And now — “But the proof does not stop at mere family resemblance.” He is coming to the matter of the birth-marks. He calls them “evidence which is not impeached.”

He turns the page again, and begins at the top to meet the argument of Grymes from the old Spanish Partidas. But as his utterance follows his eye down the page he sets that argument aside as not good to establish such a title as that by which Miller received the plaintiff. He exonerates Miller, but accuses the absent Williams of imposture and fraud. One may well fear the verdict after that. But now he turns a page which every one can see is the last:

“It has been said that the German witnesses are imaginative and enthusiastic, and their confidence ought to be distrusted. That kind of enthusiasm is at least of a quiet sort, evidently the result of profound conviction and certainly free from any taint of worldly interest, and is by no means incompatible with the most perfect conscientiousness. If they are mistaken as to the identity of the plaintiff; if there be in truth two persons about the same age bearing a strong resemblance to the family of Miller [Müller] and having the same identical marks from their birth, and the plaintiff is not the real lost child who arrived here with hundreds of others in 1818, it is certainly one of the most extraordinary things in history. If she be not, then nobody has told who she is. After the most mature consideration of the case, we are of opinion the plaintiff is free, and it is our duty to declare her so.

“It is therefore ordered, adjudged, and decreed, that the judgment of the District Court be reversed; and ours is that the plaintiff be released from the bonds of slavery, that the defendants pay the costs of the appeal, and that the case be remanded for further proceedings as between the defendant and his warrantor.”