Cheré Coen.

“Forest Hill, Louisiana: A Bloom Town History.”

© Cheré Coen.

Used by permission.

All rights reserved.

Introduction

DRIVING north on Interstate 49 through the heart of Louisiana, the terrain changes shortly past Bunkie. Prairies dotted with sprawling live oak trees and rice fields filled with crawfish buckets quickly turn to rolling hills and dense pine forests. Turn right at Exit 66 and the hills disappear, replaced by the flat, alluvial plains of the Red River where once plantations grew cotton and there was sugar cane as far as the eye could see. Head west from I-49 and the hills continue, the highway rolling through acres of what gardeners consider a Louisiana heaven.

At first glance, the town of Forest Hill appears as little more than a moment at a traffic light. Before visitors connect with U.S. Highway 165, another main thoroughfare to Lake Charles or Alexandria, they’ll spot the Forest Hill City Hall, the volunteer fire department, a small collection of businesses — including one bank and a barbershop — and a delightful municipal park with a pond at its center. A few streets over is the elementary school and the former high school’s gymnasium, now being used as a senior citizens center. Scattered here and there are the handful of churches and cemeteries tucked within the woods.

And then there are the more than 200 plant nurseries. Without the acres and acres of plant nurseries greeting visitors on the way into town, Forest Hill would just be another small, rural Louisiana town. Instead, it’s home to a multimillion-dollar industry. Even more surprising, the population of Forest Hill hovers near nine hundred residents, while the number of plant nurseries in the town and surrounding areas has been well over two hundred for at least a few decades. The recent recession took a small bite out of the trade, which saw its heyday in the ’80s and ’90s and depends largely on the housing industry, but business is still blooming in Forest Hill, a pun that’s routinely popular in newspaper and magazine headlines.

The history of Forest Hill predates the nursery industry, with economics in the piney woods demanding constant reinvention. Small farmers and timber mill owners moved into the region in the 19th century, but the soil wasn’t as conducive to farming as the rich loam to the east near the town of Lecompte, where plantations were built on Red River floodplains and slave labor cotton drew a high price at market. Fortunes were made along Bayou Boeuf south of Alexandria, so settlement in the piney woods in and around present-day Forest Hill was slow to come by, except by hardy souls who started farms and plantation owners who visited the pine forests to escape the destructive fevers of summer.

One of those early settlers was William Prince Ford, who owned a plantation house on the old Texas Road near Hurricane Creek, what is today Blue Lake Road in Forest Hill. His sawmill was a few miles to the north on Indian Creek, and his wife owned a large plantation on Bayou Boeuf. Ford was pastor of Spring Hill Baptist Church and headmaster of Spring Creek Academy from 1837 to just before the Civil War.

Much is written of one of the first settlers of Forest Hill due to the memoirs of Solomon Northup, a free man of color who was kidnapped into slavery, brought to New Orleans and sold to Ford and his Rapides Parish plantation in 1841. Northup was a literate man and wrote of his ordeal in Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853, From a Cotton Plantation near the Red River in Louisiana, with the assistance of writer David Wilson. Northup details Ford’s house, his neighbors,cthe mill on Indian Creek, and the Native Americans who resided there. It’s a detailed, first-person account of early life in what Northup called the “Great Piney Woods.”

After the Civil War, the economy shifted for those growing cotton on Bayou Boeuf plantations, although prosperity for Forest Hill was still decades away. Where thoughts of taking advantage of the great virgin pine forests to the west had crossed minds in the early and mid-19th century, ideas on milling these acres of opportunity only took shape with the advent of railroads and investors in the latter part of the century. Once the Kansas City, Watkins, and Gulf Railway pushed through the area in 1892, establishing a depot at Forest Hill, a new era began. The prosperous timber industry roared through the piney woods as fast as a forest fire with this new avenue of shipping lumber to market — in many ways, it was just as destructive upon its conclusion. For years, jobs were plenty and towns sprung up almost overnight to satisfy the sawmills and their ever-roaring blades slicing massive longleaf pine into lumber.

In 1897, Forest Hill officially became a town, with citizens working at a number of sawmills in the area, including the large Long Leaf complex and two major mills at McNary. Gravel pits began operating as well, and railroad spurs traversed the woods in all directions. “It was an industrial complex,” said Everett Lueck, senior staff geologist at Alta Mesa Holdings and president of the board at the Southern Forest Heritage Museum, located just outside Forest Hill.

By the 1920s, however, the timber was spent, acres in all directions clear cut and devoid of the majestic longleaf pine trees. With the elimination of forests came the abandonment of the lumber companies, many packing up shop and leaving the region, if not Louisiana. Forest Hill residents had to learn to regroup, return to farming, or head to the gravel pits.

One entrepreneur, Samuel Stokes, had a better idea. A lover of plants and nature, Stokes found interesting species in the piney woods near his home, plants such as rare dogwoods, camellias, and azaleas. Stokes taught himself horticulture and learned to graft, propagating the central Louisiana native plants, first for his own enjoyment and then to sell to others. He discovered pansies as well as ways to grow hundreds of the colorful flowers on his property for an eager market throughout the country. Within years, Stokes had a booming nursery business.

Forest Hill residents also found new opportunities with the Civilian Conservation Corps, which arrived to alleviate the devastation to the soil brought on by unregulated timber practices. A state fish hatchery was built; neighboring Woodworth received a massive fire tower, which helped in combating the relentless forest fires; and tourists visited the area’s watering holes, such as Shady Nook and fishing meccas Indian Creek Dam and Cocodrie Lake. In the meantime, Stokes taught others his nursery business, including residents such as Baker Taylor, Billy Mitchell, and the Poole brothers (Murphy Archie Poole and Hayden Johns Poole Sr.). The industry began to slowly grow.

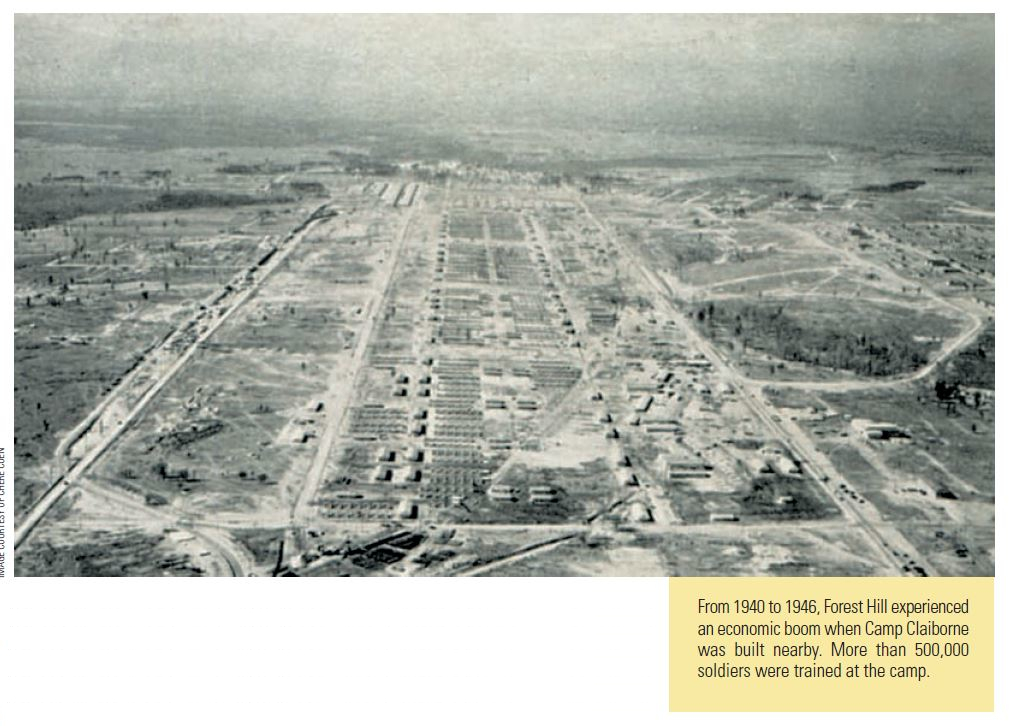

By 1940 the economy of Forest Hill — and Rapides Parish — shifted again. Troops training for combat in World Boilers were used to steam non-essentials from the soil to harvest and plant pansy seeds, which were a huge seller for the Stokes Nursery. War II came roaring through the region much like the timber industry had done, with 500,000 troops visiting the temporary military base of Camp Claiborne just a few short miles north of Forest Hill from 1940 to 1946. The town enjoyed prosperity instantly, feeding off the military base and its temporary inhabitants until, like the virgin forest, the soldiers were gone.

Once again, Forest Hill was forced to reinvent itself, and it found its stride in a new and exciting venture. Residents began working for the Stokes and Poole Brothers Nurseries, learning the trade and opening their own nurseries soon thereafter. New generations came along to take their parents’ places, branching out like a genealogy tree and marrying into other nursery families.

The Central Louisiana Association of Nurserymen was organized to promote networking and cost-saving measures among the nursery owners, and the growing industry started attracting nursery distributors and other associated businesses.

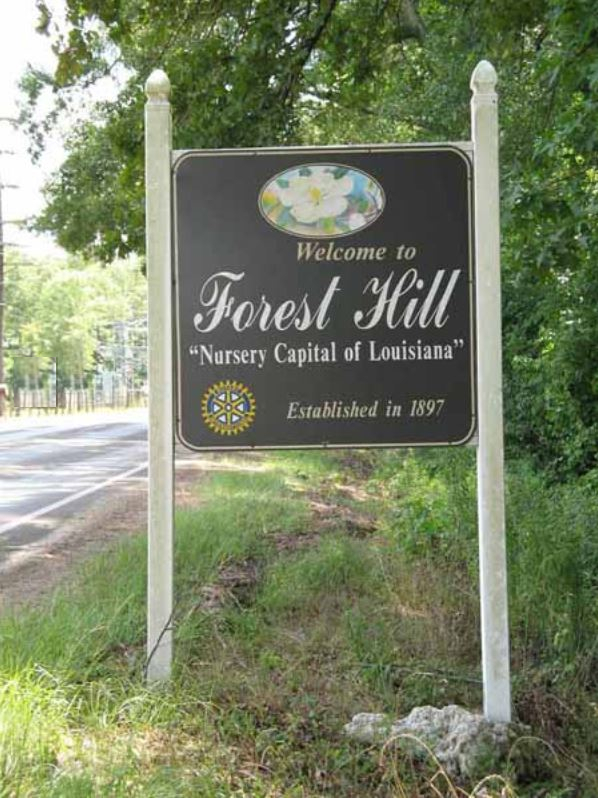

By the 1980s, Forest Hill owned a thriving plant nursery industry, one that inspired the Louisiana legislature to label it the “Nursery Capital of Louisiana.” Plants grown in Forest Hill traveled throughout Louisiana and its surrounding states; some were sold as far as the East Coast, and many ended up on shelves of big-box stores such as Lowe’s, Home Depot, and Walmart. Every spring, thousands would flock to the piney woods town for the popular Louisiana Nursery Festival.

And the great American success story continued with the Hispanic community of Forest Hill — workers arrived from Mexico as seasonal workers to fill a labor shortage, learned the trade, and opened their own nurseries, much as the early Forest Hill residents had done.

Today, the success story that is Forest Hill lines Highways 112 and 165, pouring into neighboring towns such as Glenmora, Woodworth, McNary and Lecompte. Even nurseries located in adjacent parishes have ties to the horticultural town, connected to one another through a unique sharing of business. Some nurseries, such as Stokes, date back one hundred years or more, while others are newcomers to the trade.

At first glance, Forest Hill appears as another miniature, rural Louisiana town nestled in the state’s piney wood forests. Children attend the local elementary, parents deposit their money at the Red River bank branch, and residents pay their municipal bills at the small windowed office at City Hall. On Sundays, voices rise up in a handful of churches.

Just behind the small-town façade, however, lies a massive green industry, its rows of woody ornamentals, trees, and flowers branching off from the center of town for thousands of acres into the horizon. Like the headlines sporting puns, Forest Hill is a bloom town.

Sam Stokes Starts an Industry

THERE are more than 200 plant nurseries in and around Forest Hill today, and they all owe their existence to a self-taught man.

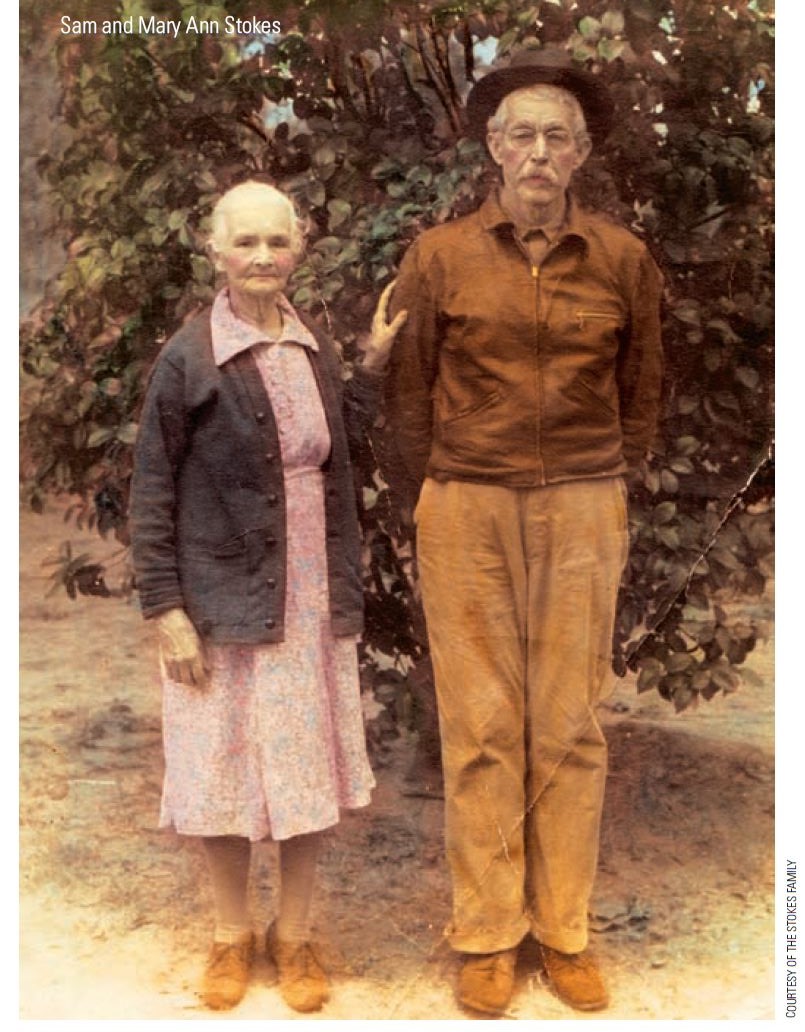

Samuel Stokes was born on December 28, 1866, to Samuel Washington Stokes and Kindness Pope of Mississippi. The family moved to central Louisiana in 1869, first settling in an area of Rapides Parish that would later be Vernon Parish when the boundaries shifted. Young Sam Stokes and his wife, Mary Ann Musgrove, a member of a Rapides Parish pioneering family, moved to the Midway community in 1896, literally halfway between Forest Hill and Lecompte on Highway 112. Their money was meager, but they managed to purchase 50 acres for $50, a parcel of land with soil a combination of sand and clay. Crops didn’t take so well to this piney woods land, but the soil allowed for good drainage and easy removal of plants, the perfect habitat for a nursery.

Courtesy of the Stokes Family.

Stokes first grew and grafted fruit trees for his own use, teaching himself planting and propagation techniques. Soon, neighbors began asking for his plants, and Stokes realized that there was a market to be had. He began first selling plants to friends and neighbors; then he opened a nursery to the public in 1901.

“Samuel Stokes was the first plant nurseryman in the Forest Hill, Louisiana, area,” wrote Wilford Perry Stokes in Stokes, a Family History. “He was a self-taught, nationally recognized authority on nursery plant propagation.”

The tall, blue-eyed man respected all plants, said his daughter, Maude Stokes Athens in a 1984 Louisiana Life magazine article. “He wasn’t a … religious man, but he’d sit on the porch when it’d be springtime, and he’d say, ‘Now, those leaves, there, they know when to come out. They know when the winter’s over.’ He could identify all the trees in the woods, even in winter, when they were bare.”

Stokes would roam the region’s forests and return home, arms covered in flowers, shrubs, and other plants ready to be propagated and planted, according to his wife in Lecompte: Plantation Town in Transition. “Well, he started raising strawberries, but he couldn’t get but 50 cents a gallon for ’em, so he started selling his plants, mostly native growth like holly, live oak, and yaupon,” she said. “It was back in the fall of 1900 when we sold our first plants�cape jasmines.”

Stokes would travel by train, selling his Rapides Parish plants in Alexandria and New Orleans. He shared his knowledge of Louisiana horticulture with customers, even corresponding with Cammie Henry of Melrose Plantation in Natchitoches, who collected native plants, and conservationist Caroline Dormon, who wrote numerous books on Louisiana trees and plants and helped establish the Kisatchie National Forest in central Louisiana.

“He spent a long time rambling through the woods around here,” said Forest Hill resident and nursery owner Marcia Young. “He was an amateur biologist. And Caroline Dorman, who wrote the book [Wild Flowers of Louisiana, with the assistance of Stokes], was his pal, and she’d come down or come up from LSU and wander with him in the woods.”

Stokes became adept at grafting — a horticultural technique by which tissue from a plant is inserted onto the rootstock of another, and a new plant is produced where the tissues have joined together. Over the years, Stokes produced the first dwarf yaupon holly; a double pink camellia, named for his granddaughter, Alice Stokes; and the propagation of the Governor Mouton camellia from cuttings gleaned from the Mouton family’s gardens in Lafayette (Alexandre Mouton was the ninth governor of Louisiana). In front of the Stokes Nursery grew two tung oil trees that he grafted together, forming an arch.

“Papa was always grafting,” Athens said. “He’d sit flat down on the floor and graft at night.”

“He’s the father of them all,” Young said. “There’s hardly a state in the union where you can’t find a dwarf yaupon.”

Nursery plants were grown in the fields when Stokes began his business. Whereas the piney woods soil wasn’t ideal for crops, the sandy, porous soil provided a good nesting area for young plants. The piney woods also helped to shelter plants against wind and cold. “That [soil] was good for azaleas, acid soil,” said George Johnson, originator of George Johnson Nursery. “You could grow camellias, hollies; they are acid-loving plants. Mr. Stokes used to go in the woods and pick up seedlings — magnolias and dogwoods, yaupon, American holly. These were all seedlings. He started doing this, selecting this stuff out in the woods. Some of it he planted, and some of it he’d sell bare root. He would plant things in his nursery, but if someone came by wanting to buy them bare root, he’d sell them to them.”

For the plants in the fields, customers would arrive at the Stokes Nursery in Midway and choose their plants, and Stokes would dig them up, dip them into a soil mixture and wrap them in moss or burlap; they would be ready for the planting when customers reached home.

“Everything was grown in the field, then, like cotton,” recalled Hayden Johns Poole, Jr., in a 1984 Louisiana Life article. “Everybody had them a little mud hole near the well, a little trough-like. They’d go in the hills, get sticky red clay off the banks, bring it back and make a thick batter in the mud hole. They’d dip the plant in it coating the roots, lay out a sack and put straw in with the plant and wrap it all up.” Later, burlap was used as an outer wrapping for nursery owners selling plants to the public.

Word soon got out about Stokes’s nursery and his talent with plants. Customers would travel down from Alexandria and up from Cajun country. “People would come and eat lunch here because it took so long to get here,” said Sam Stokes (great-grandson of Sam Stokes), who now owns the nursery with his wife, Donna.

A good part of his business, however, was shipping plants from the Forest Hill depot. Pansies were a huge seller for the Stokes Nursery, and Stokes would steam the soil to kill grass and other nonessential seeds by a portable boiler; then he would plant the pansy seeds and cover them until they grew. Once pulled from the sand, bundled, and boxed, trains would transport the plants all over the southern United States.

Pansies proved a successful plant for Stokes because they could be grown in mass. The plants sold rather cheaply, but Stokes made his money by shipping in bulk. “They were not humongous,” Young explained. “You can grow a lot of little bitty plants in a very small amount of sand beds.”

Success wasn’t easy for Forest Hill residents at the turn off the 20th century. Lumber mills provided jobs until the forests were cleared, and the piney woods soil wasn’t as conducive to farming as the plantation lands to the east along Bayou Boeuf. As Stokes was able to operate a feasible business, it gave other residents inspiration, and he was willing to share his expertise. He taught Baker Taylor his grafting techniques, for instance, who then taught his son, Harvey Taylor. Taylor’s nursery opened in the 1920s to grow gardenias, sweet olive, Easter lilies, cherry laurel, and Southern magnolia. “After World War I, Mr. Stokes helped Papa get started in his own nursery,” Harvey Taylor explained in the Louisiana Life article.

Billy Mitchell also caught the fever, starting his nursery in 1923. The Poole brothers, Murphy Archie Poole and Hayden Johns (“H.J.”) Poole Sr., opened a nursery shortly afterward, selling roses and fig trees. They, too, grew plants in the field and removed them bare root to send home with customers, along with offering catalogues and shipment by rail.

The Poole brothers married the Chamberlain sisters, with Murphy marrying Odessa Irene Chamberlain (known as “Dessie”) and H.J. marrying Bessie Rovilla Chamberlain; both women were part of a family that owned a nursery as well. George Johnson, a field operator at Poole Brothers Nursery before owning his own nursery, married Murphy Poole’s daughter, Vera Lee Poole. Murphy’s son, Samuel Newman Poole Sr., married Wanda Ruth Johnson, Johnson’s sister.

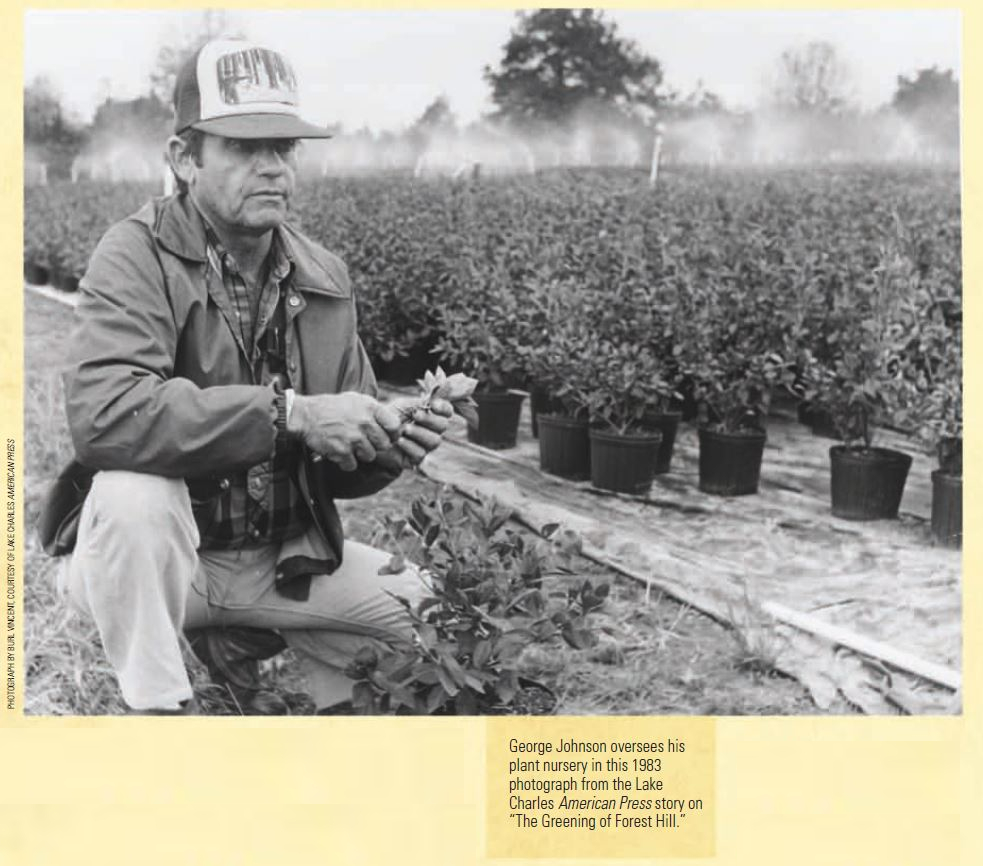

“You might say I married into the business,” George Johnson told the Lake Charles American Press, which spotlighted his nursery in a December 18, 1983 article. “As a boy, I knew every tree in these woods�by the bark and by the leaf but I never dreamed I’d ever be in the growing business.”

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Coen, Cheré Dastugue. Forest Hill Louisiana: A Bloom Town History. Charleston, SC: History, 2014. Print. © Cheré Coen. Used by permission. All rights reserved.