Helen Lockwood Coffin,

J. H. Gore,

W. S. Harwood,

F. H. Spearman, &

L. E. Stofiel.

Southern Stories:

Retold from St. Nicholas.

W. S. Harwood,

F. H. Spearman, &

L. E. Stofiel.

SOUTHERN STORIES

RETOLD FROM ST. NICHOLAS

Copyright, 1889, 1890, 1891, 1892, 1894, 1898, 1900, 1902, 1903, 1907,

by The Century Co.

THE DE VINNE PRESS

CONTENTS

| How We Bought Louisiana | Helen Lockwood Coffin |

| The City that Lives Outdoors | W. S. Harwood |

| Queer American Rivers | F. H. Spearman | Hiding Places in War Times | J. H. Gore |

| The “Walking-Beam Boy” | L. E. Stofiel |

SOUTH

Under the feet a garden of flowers, and the bluest of heavens

Bending above, and resting its dome on the walls of the forest.

— Longfellow.

HOW WE BOUGHT LOUISIANA

BY HELEN LOCKWOOD COFFIN

IT is a hard matter to tell just how much power a little thing has, because little things have the habit of growing. That was the trouble that France and England and Spain and all the other big nations had with America at first. The thirteen colonies occupied so small and unimportant a strip of land that few people thought they would ever amount to much. How could such insignificance ever bother old England, for instance, big and powerful as she was? To England’s great loss she soon learned her error in underestimating the importance or strength of her colonies.

France watched the giant and the pygmy fighting together, and learned several lessons while she was watching. For one thing, she found out that the little American colonies were going to grow, and so she said to herself: “I will be a sort of back-stop to them. These Americans are going to be foolish over this bit of success, and think that just because they have won the Revolution they can do anything they wish to do. They’ll think they can spread out all over this country and grow to be as big as England herself; and of course anybody can see that that is impossible. I’ll just put up a net along the Mississippi River, and prevent them crossing over it. That will be the only way to keep them within bounds.”

And so France held the Mississippi, and from there back to the Rocky Mountains, and whenever the United States citizen desired to go west of the Mississippi, France said: “No, dear child. Stay within your own yard and play, like a good little boy,” or something to that effect.

Now the United States citizen didn’t like this at all; he had pushed his way with much trouble and expense and hard work through bands of Indians and through forests and over rivers and mountains, into Wisconsin and Illinois, and he wished to go farther. And, besides, he wanted to have the right to sail up and down the Mississippi, and so save himself the trouble of walking over the land and cutting out his own roads as he went. So when France said, “No, dear,” and told him to “be a good little boy and not tease,” the United States citizen very naturally rebelled.

Mr. Jefferson was President of the United States at that time, and he was a man who hated war of any description. He certainly did not wish to fight with his own countrymen, and he as certainly did not wish to fight with any other nation, so he searched around for some sort of a compromise. He thought that if America could own even one port on this useful river and had the right of Mississippi navigation, the matter would be settled with satisfaction to all parties. So he sent James Monroe over to Paris to join our minister, Mr. Livingston, and see if the two of them together could not persuade France to sell them the island of New Orleans, on which was the city of the same name.

Now Napoleon was the ruler of France, and he was dreaming dreams and seeing visions in which France was the most important power in America, because she owned this wonderful Mississippi River and all this “Louisiana” which stretched back from the river to the Rockies. He already held forts along the river, and he was planning to strengthen these and build some new ones. But you know what happens to the plans of mice and men sometimes. Napoleon was depending upon his army to help him out on these plans, but his armies in San Domingo were swept away by war and sickness, so that on the day he had set for them to move up into Louisiana not a man was able to go. At the same time Napoleon had on hand another scheme against England, which was even more important than his plans for America, and which demanded men and money. Besides this, he was shrewd enough to know that he could not hold this far-away territory for any long time against England, which had so many more ships than France. He suddenly changed his mind about his American possessions, and nearly sent Mr. Monroe and Mr. Livingston into a state of collapse by offering to sell them not only New Orleans but also the whole Province of Louisiana.

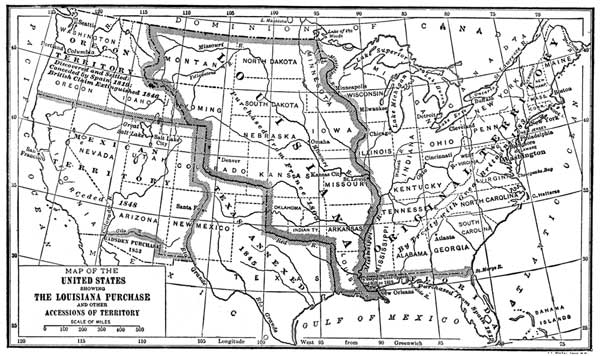

The Louisiana Purchase and Other Accessions of Territory.

There was no time to write to President Jefferson and ask his advice, and this was before the days of the cable; so Monroe and Livingston took the matter into their own hands, and signed the contract which transferred the Louisiana territory to the United States for a consideration of $15,000,000. They were severely criticized by many of their own countrymen, and they had some doubts of their own about the wisdom of their action. You see, nobody knew then that corn and wheat would grow so abundantly in this territory, or that beyond the Mississippi there were such stretches of glorious pasture-lands, or that underneath its mountainous regions were such mines of gold, silver, and copper. Americans saw only the commercial possibilities of the river, and all they wanted was the right of navigating it and the permission to explore the unknown country to the westward.

But Jefferson and Monroe and Livingston builded better than they knew. All this happened a hundred years ago; and to-day that old Louisiana territory is, in natural resources, the wealthiest part of the whole United States. Without that territory in our possession we should have no Colorado and no Wyoming, no Dakotas, or Nebraska, or Minnesota, or Montana, or Missouri, or Iowa, or Kansas, or Arkansas, or Louisiana, or Oklahoma, or Indian Territory.

For all these reasons we owe our most sincere and hearty thanks to the patriotic and far-sighted men who were concerned in buying this territory for the United States.

It is a hard matter to tell just how much power a little thing has, because little things have the habit of growing. That was the trouble that France and England and Spain and all the other big nations had with America at first. The thirteen colonies occupied so small and unimportant a strip of land that few people thought they would ever amount to much. How could such insignificance ever bother old England, for instance, big and powerful as she was? To England’s great loss she soon learned her error in underestimating the importance or strength of her colonies.

France watched the giant and the pygmy fighting together, and learned several lessons while she was watching. For one thing, she found out that the little American colonies were going to grow, and so she said to herself: “I will be a sort of back-stop to them. These Americans are going to be foolish over this bit of success, and think that just because they have won the Revolution they can do anything they wish to do. They’ll think they can spread out all over this country and grow to be as big as England herself; and of course anybody can see that that is impossible. I’ll just put up a net along the Mississippi River, and prevent them crossing over it. That will be the only way to keep them within bounds.”

And so France held the Mississippi, and from there back to the Rocky Mountains, and whenever the United States citizen desired to go west of the Mississippi, France said: “No, dear child. Stay within your own yard and play, like a good little boy,” or something to that effect.

Now the United States citizen didn’t like this at all; he had pushed his way with much trouble and expense and hard work through bands of Indians and through forests and over rivers and mountains, into Wisconsin and Illinois, and he wished to go farther. And, besides, he wanted to have the right to sail up and down the Mississippi, and so save himself the trouble of walking over the land and cutting out his own roads as he went. So when France said, “No, dear,” and told him to “be a good little boy and not tease,” the United States citizen very naturally rebelled.

Mr. Jefferson was President of the United States at that time, and he was a man who hated war of any description. He certainly did not wish to fight with his own countrymen, and he as certainly did not wish to fight with any other nation, so he searched around for some sort of a compromise. He thought that if America could own even one port on this useful river and had the right of Mississippi navigation, the matter would be settled with satisfaction to all parties. So he sent James Monroe over to Paris to join our minister, Mr. Livingston, and see if the two of them together could not persuade France to sell them the island of New Orleans, on which was the city of the same name.

Now Napoleon was the ruler of France, and he was dreaming dreams and seeing visions in which France was the most important power in America, because she owned this wonderful Mississippi River and all this “Louisiana” which stretched back from the river to the Rockies. He already held forts along the river, and he was planning to strengthen these and build some new ones. But you know what happens to the plans of mice and men sometimes. Napoleon was depending upon his army to help him out on these plans, but his armies in San Domingo were swept away by war and sickness, so that on the day he had set for them to move up into Louisiana not a man was able to go. At the same time Napoleon had on hand another scheme against England, which was even more important than his plans for America, and which demanded men and money. Besides this, he was shrewd enough to know that he could not hold this far-away territory for any long time against England, which had so many more ships than France. He suddenly changed his mind about his American possessions, and nearly sent Mr. Monroe and Mr. Livingston into a state of collapse by offering to sell them not only New Orleans but also the whole Province of Louisiana.

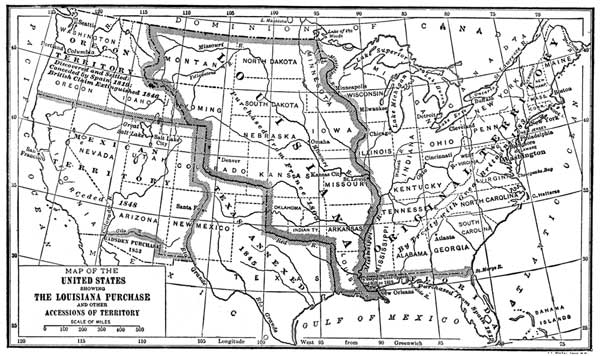

The Louisiana Purchase and Other Accessions of Territory.

There was no time to write to President Jefferson and ask his advice, and this was before the days of the cable; so Monroe and Livingston took the matter into their own hands, and signed the contract which transferred the Louisiana territory to the United States for a consideration of $15,000,000. They were severely criticized by many of their own countrymen, and they had some doubts of their own about the wisdom of their action. You see, nobody knew then that corn and wheat would grow so abundantly in this territory, or that beyond the Mississippi there were such stretches of glorious pasture-lands, or that underneath its mountainous regions were such mines of gold, silver, and copper. Americans saw only the commercial possibilities of the river, and all they wanted was the right of navigating it and the permission to explore the unknown country to the westward.

But Jefferson and Monroe and Livingston builded better than they knew. All this happened a hundred years ago; and to-day that old Louisiana territory is, in natural resources, the wealthiest part of the whole United States. Without that territory in our possession we should have no Colorado and no Wyoming, no Dakotas, or Nebraska, or Minnesota, or Montana, or Missouri, or Iowa, or Kansas, or Arkansas, or Louisiana, or Oklahoma, or Indian Territory.

For all these reasons we owe our most sincere and hearty thanks to the patriotic and far-sighted men who were concerned in buying this territory for the United States.

THE CITY THAT LIVES OUTDOORS

BY W. S. HARWOOD

WHEN the wind is howling through the days of the mad March far up in the lands where snow and ice thick cover the earth, here in this city that lives outdoors the roses are clambering over the “galleries” and the wistaria is drooping in purplish splendor from the low branches of the trees and from the red heights of brick walls.

The yellow jonquils, too, are swelling, and the geraniums are throwing out their scarlet flame across wide stretches of greensward, while the violets are nodding at the feet of the gigantic magnolias, whose huge yellowish-gray buds will soon burst into white beauty, crowning this noblest of flower-bearing trees.

It is a strange old city, this city that lives outdoors — a city rich in romantic history, throbbing with tragedy and fascinating events, a beautiful old city, with a child by its side as beautiful as the mother. The child is the newer, more modern city, and the child, like the parent, lives out of doors.

The people seem to come into closer touch with nature than the people of most other portions of the land. The climate, the constant invitation of the earth and sky, seem to demand a life lived in the open. This city that lives outdoors is a real city, with all a city’s varied life; but it is a country place as well — a city set in the country, or the country moved into town.

For at least nine months in the twelve, the people of this rare old town live out of doors nearly all the waking hours of the twenty-four. For the remaining three months of the year, December, January, and February, they delude themselves into the notion that they are having a winter, when they gather around a winter-time hearth and listen to imaginary wind-roarings in the chimney, and see through the panes fictitious and spectral snow-storms, and dream that they are housed so snug and warm. But when the day comes the sun is shining and there is no trace of white on the ground, and the grass is green and there are industrious buds breaking out of cover, and the earth is sleeping very lightly. Open-eyed, the youngsters sit by these December fire sides and listen to their elders tell of the snow-storms in the long ago that came so very, very deep — ah, yes, so deep that the darkies were full of fear and would not stir from their cabins to do the work of the white people; when snowballs were flying in the streets, and the earth was white, and the “banquettes,” or sidewalks, were ankle-deep in slush.

All the long years of the two centuries since this old city was born, a mighty river has been flowing by its doors, never so far forgetting its purpose to live outdoors as to freeze its yellow crest, stealing softly past by night and by day, bearing along the city’s front a vast commerce on down to the blue waters of the Gulf, and enriching the city by its cargoes from the outer world and from the plantations of the upper river. Strangely enough, the great yellow river flows above the city, its surface being nearly thirty feet above the streets in time of flood. It is held in its course by vast banks of earth.

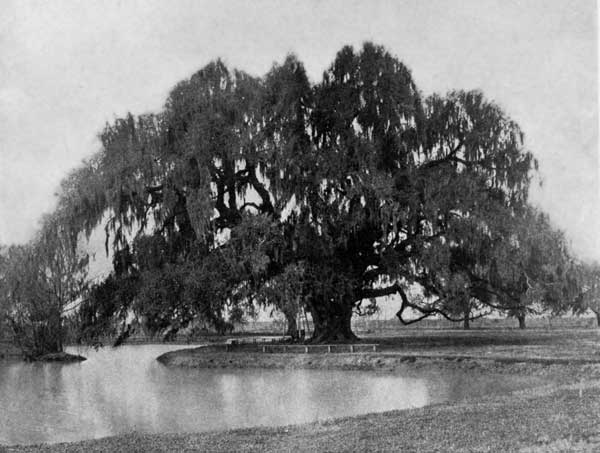

It is a cold, drear March where the north star shines high overhead; but here, where it seems suddenly to have lost its balance and to have dropped low in the brilliant night, March is like June. It is June indeed, June with its wealth of grasses, its noble avenue of magnolias, its great green spread of live-oaks — most magnificent of Southern trees; June with its soft balm, and its sweet sunshine, and its perfume-laden air. And if you have never seen the pole star in the sky of the north, where the star is almost directly over your head, you cannot realize how strange a sight it is to see it so low in the sky as it is here.

There is a large garden in this city — it is, in fact, a part of the city proper. It was once a beautiful faubourg, now known as the Garden District, where the people live outdoors in a fine old aristocratic way, and where all the beauty in nature seen in the other sections of the city seems to be outdone. Very many rare old homes are in this garden region, with its deep hedges and ample grounds, inclosed in high stone walls, and a wealth of flowers and noble courts and an abounding hospitality. But what, after all, are houses to a people that lives outdoors? Conveniences only; for such a people, better than houses are the air of the open, the scent of the roses, the blue of the Southern sky, the vast, strong sweep of the brilliant stars!

If we pause here along this street where run such every-day things as electric street-cars, we shall see on one side of the splendid avenue a smooth-paved roadway for the carriages, on the other a course for the horsemen, and in the center a noble inner avenue of trees set in a velvet-like carpet of grass; and here and there along the way, almost in touch of your hand from the open car window, appears the Spanish dagger, with its green, sharp blades and its snowy, showy plume. Not far away stands a lowly negro cabin, where the sun beats down hot and fierce upon a great straggling rose-bush, reaching up to the eaves, beating back the rays of the sun defiantly and gaining fresh strength in the struggle. On such a bush one day I counted two hundred and ninety roses.

This city which lives outdoors must play most in the open, and in its noble park, with its vast stretches of bright green, here empurpled by masses of the dainty grass-flower, there yellowing with the sheen of the buttercup, one finds the tireless golf-players leisurely strolling over the links; from yonder come the cries of the boys at ball; and in the farther distance you may see through the frame-like branches of a giant live-oak the students of a great university hard set at a game of tennis. And yet — is it the air, or the race, or the traditions? — something it is which makes the sportsmen, like the spring, seem slow to move.

And here even the palms grow outdoors in the city yards. And should you go past the city’s limits, and yet within seeing distance of its blue-tiled housetops, you will find the palms growing rank in the great swamps, which you must search if you care to hunt for the languid alligators — palms growing so thick and rank that it is quite like looking into some vast conservatory, with the blue dome of the sky for glass. And here grow the magnolias in their wild, barbaric splendor of bloom, and the live-oaks, mighty of girth and spread, draped in somber gray moss as if for the funeral of some god of the deep green wood. At the fringe of the swamp, tempting you until near to jumping into the morass after them, are the huge fleurs-de-lis, each gorgeous blossom fully seven inches across its purple top.

To the north, somewhat apart from the reach of the treacherous river, lie the health-giving piny woods, and along the big, sullen stream the sugar plantations, some of them still the home of a lavish hospitality, some of them transformed into mere places of trade, where thrift and push have elbowed out all that fine gallantry and ease and ample hospitality of an earlier day — that hospitality which will ever remain a leading characteristic of the people. To be a Southern man or a Southern woman and to be inhospitable — that is not possible in the nature of things.

It is, when all is said and done, on the gallery that this city lives most of its life — on the gallery even more than on the evening-thronged banquette, which is the sidewalk of the North, or the boulevards, or even the fragrant parks, where life flows in a fair, placid stream. Some there must be who toil by day in shop, or at counter, or in dim accounting-rooms, or on the floors of the marts where fortunes are made and lost in sugar or cotton or rice. For such the gallery is a haven of rest. If they must pass the earlier day indoors, for them the gallery during the long, late afternoon, and the ghost of a twilight, and the long evenings far into the starry night. The ghost of a twilight indeed — the South knows no other. Sometimes I have watched the long, splendid twilight come down over the wild Canadian forest — slowly delaying; creeping up the low mountains; halting from hour to hour in the glades below; shade after shade in the glorious sky of the west gradually merging into the dimness of the oncoming dusk; the moments passing so slowly, the day fading so elusively, until, at last, when even the low moon has hung out its silver sign in the west and the stars are pricking through, it is still twilight along the lower earth. And still farther to the north, around the globe in the far upper Europe, with the polar circle below you, it is like living on a planet of eternal day to sit through the northern light and feel about you the all-pervasive twilight of the land of the midnight sun. But the night is so hasty here, and the day is swift; and between them runs but a slender, dim thread.

The gallery is a feature of every house in this city that lives outdoors, be it big or little, humble or grand, or lowly or mean. It is on the first floor or the second, or even the third, though the third it seldom reaches, for few people care for houses of great height. Indeed, there are hundreds of homes of but one story, full of the costliest tokens of the taste of an artistic people. And the soil below is so like a morass that ample space must be left between floor and earth; while as for cellars, I have heard of but two in all the great city. The gallery may run around the entire house, flanked and set off by splendid pillars with capitals rich and ornate; it may run across one end of the residence and be a marvel of rich ironwork, as fine as art and handicraft can make it, with, mayhap, the figures of its field outlined in some bit of color, as gold or green; it may be but a single cheap wooden affair, paintless, dingy, dilapidated, weather-worn, and stained with neglect; but a gallery it is still, an important social feature of this outdoor life.

Over the gallery grow the roses; out near at hand a bignonia-vine lifts its yellow flare aloft and throws down a fluttering shower of bell-like blooms, and all the air is heavy with the scents of the South. So through the long evening the people sit upon the gallery and chat or read or sing or doze or plan or discuss their family affairs. By day the galleries are protected with gay-colored awnings or those filmy woven sheets of reeds which keep out the glare and let through the light and the fragrant breeze. Children make of the gallery a play-house; young people here entertain their friends; the elders discuss the affairs of a nation or dwell on that wonderful past through which this ancient Southern city has come tumultuously down through the lines of Castilian and Saxon and Gaul.

If you should take your map of the United States and run your finger far down its surface until it rested upon the largest city in all the beautiful South, and the metropolis of a vast inner empire which holds two civilizations, one French-Spanish, one American, both slowly, very slowly, merging through the centuries; or, better still, if you should stroll along the streets on a sweet March day, peering into its curious quarters, watching the beautiful little children and the dark-eyed men and the gaily dressed women and all the throngs of people, city people who can never long remain away from the green fields and the noble old trees and the scent of the roses — then you could not fail to hit upon this charming old place, New Orleans — in many ways the most interesting of all the cities in America, the beautiful city that lives outdoors.

QUEER AMERICAN RIVERS

BY F. H. SPEARMAN

I wonder if my readers realize what a story of the vast extent of our country is told by its rivers?

Every variety of river in the world seems to have a cousin in our collection. What other country on the face of the globe affords such an assortment of streams for fishing and boating and swimming and skating — besides having any number of streams on which you can do none of these things? One can hardly imagine rivers like that; but we have them, plenty of them, as you shall see.

As for fishing, the American boy may cast his flies for salmon in the Arctic circle, or angle for sharks under a tropical sun in Florida, without leaving the domain of the American flag. But the fishing-rivers are not the most curious, nor the most instructive as to diversity of climate, soil, and that sort of thing — physical geography, the teacher calls it.

For instance, if you want to get a good idea of what tropical heat and moisture will do for a country, slip your canoe from a Florida steamer into the Ocklawaha River. It is as odd as its name, and appears to be hopelessly undecided as to whether it had better continue in the fish and alligator and drainage business, or devote itself to raising live-oak and cypress-trees, with Spanish moss for mattresses as a side product.

In this fickle-minded state it does a little of all these things, so that when you are really on the river you think you are lost in the woods; and when you actually get lost in the woods, you are quite confident your canoe is at last on the river. This confusion is due to the low, flat country, and the luxuriance of a tropical vegetation.

To say that such a river overflows its banks would hardly be correct; for that would imply that it was not behaving itself; besides, it has n’t any banks — or, at least, very few! The fact is, those peaceful Florida rivers seem to wander pretty much where they like over the pretty peninsula without giving offense; but if Jack Frost takes such a liberty — presto! you should see how the people get after him with weather-bulletins and danger-signals and formidable smudges. So the Ocklawaha River and a score of its kind roam through the woods, — or maybe it is the woods that roam through them, — and the moss sways from the live-oaks, and the cypress trees stick their knees up through the water in the oddest way imaginable.

In Florida one may have another odd experience: a river ride in an ox-cart. Florida rivers are usually shallow, and when the water is high you can travel for miles across country behind oxen, with more or less river under you all the way. There are ancient jokes about Florida steamboats that travel on heavy dews, and use spades for paddle-wheels.

But those of you who have been on its rivers know there is but one Florida, with its bearded oaks and fronded palms; its dusky woods, carpeted with glassy waters; its cypress bays, where lonely cranes pose, silently thoughtful (of stray polliwogs); and its birds of wondrous plumage that rise with startled splash when the noiseless canoe glides down upon their haunts.

Every strange fowl and every hideous reptile, every singular plant and every tangled jungle, will tell the American boy how far he is to the south. Florida is, in fact, his corner of the tropics; and the clear waters of its rivers, stained to brown and wine-color with the juices of a tropical vegetation, will tell him, if he reads nature’s book, how different the sandy soil of the South is from the yellow mold of the great Western plains.

Such a boy hardly need ask the conductor how far west he is if he can catch a glimpse of one of the rivers. All the rivers of the plains are alike full of yellow mud, because the soil of the plains melts at the touch of water. These are our spendthrift rivers, full to the banks at times, but most of the year desperately in need of water. It is only with the greatest effort that they can keep their places in the summer: there is just a scanty thread of water strung along a great, rambling bed of sand, to restrain Dame Nature from revoking their licenses to run and turning them into cattle-ranches.

No wonder that fish refuse to have anything to do with such streams, and refuse tempting offers of free worms, free transportation, and protection from the fatal nets. Fancy trying to raise a family of little fish, and not knowing one day where water is coming from the next!

Not but what there is water enough at times; only, those rivers of the great plains, like the Platte and the Kansas and the Arkansas, are so wasteful of their supply in the spring that by July they are gasping for a shower. So, part of the year they revel in luxury, and during the rest they go shabby — like shiftless people.

But the irrigation engineers have lately discovered something wonderful about even these despised rivers. During the very driest seasons, when the stream is apparently quite dry, there is still a great body of water running in the sand. Like a vast sponge, the sand holds the water, yet it flows continually, just as if it were in plain sight, but more slowly of course. The volume may be estimated by the depth and breadth of the sand. One pint of it will hold three quarters of a pint of water. This is called the underground flow, and is peculiar to this class of rivers. By means of ditches this water may be brought to the surface for irrigation.

Scattered among the foot-hills of the Rockies are rivers still more wilful in their habits. Instead of keeping to their duties in a methodical way, they rush their annual work through in a month or two; then they take long vacations. For months together they carry no water at all; and one may plant and build and live and sleep in their deserted beds — but beware! Without warning, they resume active business. Maybe on a Sunday, or in the middle of the night, a storm-cloud visits the mountains. There is a roar, a tearing, a crashing, and down comes a terrible wall of water, sweeping away houses and barns and people. No fishing, no boating, no swimming, no skating on those treacherous rivers; only surprise and shock and disaster!

So different that they seem to belong in a different world are the great inter-mountain streams, like the Yellowstone and the Colorado.

They flow through landscapes of desolate grandeur, vast expanses compassed by endless mountain-ranges that chill the bright skies with never-melting snows. The countless peaks look down on the clouds, while far below the clouds wind valleys that the sunlight never reaches. Twisting in gloomy dusk through these valleys, a gaping ca�on yawns. Peering fearfully into its black, forbidding depths, an echo reaches the ear. It is the fury of a mighty river, so far below that only a sullen roar rises to the light of day. With frightful velocity it rushes through a channel cut during centuries of patience deep into the stubborn rock. Now mad with whirlpools, now silently awful with stretches of green water, that wait to lure the boatman to death, the mighty river rushes darkly through the Grand Colorado Ca�on.

No sport, no fun, no frolic there. Here are only awe-inspiring gloom and grandeur, and dangers so hideous that only a handful of men have ever braved them — fewer still survived.

Grandest of American rivers though it is, you will be glad to get away from it to a noble stream like the Columbia, to a headstrong flood like the Missouri, or an inland sea like the Mississippi; on them at least you can draw a full breath and speak aloud without a feeling that the silent mountains may fall on you or the raging river swallow you up.

In the vast territory lying between the Missouri River and the Pacific Ocean the rivers are fast being harnessed for a work that will one day make the most barren spots fertile. Irrigation is claiming every year more of the flow of Western rivers. Even the tricksy old Missouri is contributing somewhat to irrigation, but in the queerest possible way.

With all its other eccentricities, the Missouri River leaks badly; for you know there are leaky rivers as well as leaky boats. The government engineers once measured the flow of the Missouri away up in Montana, and again some hundred miles further down stream. To their surprise, they found that the Missouri, instead of growing bigger down stream, as every rational river should, was actually 20,000 second-feet smaller at the lower point.

Now, while 20,000 second-feet could be spared from such a tremendous river, that amount of water makes a considerable stream of itself. Many very celebrated rivers never had so much water in their lives. Hence there was great amazement when the discrepancy was discovered. But of late years Dakota farmers away to the south and east of those points on the Missouri, sinking artesian wells, found immense volumes of water where the geologists said there would n’t be any. So it is believed that the farmers have tapped the water leaking from that big hole in the Missouri River away up in Montana; and from these wells they irrigate large tracts of land, and, naturally, they don’t want the river-bed mended. Fancy what a blessing it is, when the weather is dry, to have a river boiling out of your well, ready to flow where you want it over the wheat-fields! For of all manner of work that a river can be put to, irrigation is, I think, the most useful. But isn’t that a queer way for the Missouri to wander about underneath the ground?

HIDING PLACES IN WAR TIMES

BY J. H. GORE

FOR some years after the close of our Civil War, the attention of our people was chiefly occupied with a study and recital of the most prominent battles, the decisive events, and the acts of famous officers. But when these bolder features of the war panorama had been examined and discussed, more time was taken to look at some of the details, to call up the minor incidents, to bestow meed of praise upon privates, or to record the littles that made up the much.

The sacrifices of the women and children at home have been repeatedly referred to in general, but seldom do we see mention made of their daily privations, the petty but continual annoyances to which they were subjected, and the struggle they made to sow and reap, as well as the difficulties they met in saving the harvested crops.

The hiding-places here described were all in one house. This house was in Virginia, near a town which changed hands, under fire, eighty-two times during the war — a town whose hotel register shows on the same page the names of officers of both armies, a town where there are two large cities of the fallen soldiers, each embellished by the saddest of all epitaphs — “To the unknown dead.” Out from this battered town run a number of turnpikes, and standing as close to one of these as a city house stands to the street was the house referred to — the home of a widow, three small children, a single domestic, and, for part of the time, an invalid cousin, whose ingenuity and skill fashioned the secret places, one of which was on several occasions his place of refuge.

With fall came the “fattening time” for the hogs. They were then brought in from the distant fields, where they had passed the summer, and put in a pen by the side of the road. And although within ten feet of the soldiers as they marched by, they were never seen, for the pen was completely covered by the winter’s wood-pile, except at the back, where there was a board fence through whose cracks the corn was thrown in. Whenever the passing advance-guard told us that an army was approaching, the hogs were hurriedly fed, so that the army might go by while they were taking their after-dinner nap, and thus not reveal their presence by an escaped grunt or squeal. Fortunately, the house was situated in a narrow valley, where the opportunities for bushwhacking were so great that the soldiers did not tarry long enough to search unsuspected wood-piles. On one occasion we thought the hogs were doomed. A wagon broke down near the house, and a soldier went to the wood-pile for a pole to be used in mending the break. Luckily, he found a stick to his liking without tearing the pile to pieces. This suggested that some nice, straight pieces be always left conveniently near for such an emergency, in case it should occur again.

The house had a cellar with a door opening directly out upon the “big road,” and never did a troop, large or small, pass by without countless soldiers seeking something eatable in this convenient cellar. It was never empty, but nothing was ever found. A partition had been run across about three feet from the back wall, so near that even a close inspection would not suggest a space back of it; and being without a door, no one would think there was a room beyond. The only access to this back cellar was through a trapdoor in the floor of the room above. This door was always kept covered by a carpet, and in case any danger was imminent, a lounge was put over this, and one of the boys, feigning illness, was there “put to bed.” In this cellar apples, preserves, pickled pork, etc., were kept, and its existence was not known to any one outside of the family.

The two garrets of the house had false ends, with narrow spaces beyond, where winter clothing, flour, and corn were safely stored. The partition in each was of weather-boarding, and nailed on from the inner side so as to appear like the true ends, and, being in blind gables, there was no suspicion aroused by the absence of windows. The entrance to these little attics was through small doors that were a part of the partition, and, as usual in country houses, the clothesline stretched across the end from rafter to rafter held enough old carpets and useless stuff to silence any question of secret doors. Several closets also were provided with false backs, where the surplus linen of the household found a safe hiding-place.

In such an exposed place a company of scouts, or even a regiment, could appear so unexpectedly that it was necessary to keep everything out of sight. Even the provisions for the next meal had to be put away, or before the meal could be prepared a party of marauders might drop in and carry off the entire supply. In the kitchen a wood-box of large size stood by the stove. It had a false bottom. In the upper part was “wood dirt,” a plentiful supply of chips, and so much stove-wood that the impression would be conveyed that at least there was a good stock of fuel always on hand. The box was made of tongued and grooved boards, and one of these in the front could be slipped out, thus forming a door. Into this box all the food and silverware were put. No little ingenuity was needed in making this contrivance. The nails that were drawn out to let this board slip back and forth left tell-tale nail-holes, but these were filled up with heads of nails, so that all the boards looked just alike. I remember once a soldier was sitting on this box while mother was cooking for him what seemed to be the last slice of bacon in the house. She was so afraid that he would drum on the box with his heels, as boys frequently do, and find that the box was hollow, that she continually asked him to get up while she took a piece of wood for the fire. It was necessary to disturb him a number of times before he found it advis able to take the proffered chair, and in the meantime a hotter fire had been made than the small piece of meat required.

Of course it was advisable to have at least scraps of food lying around — their absence at any time would have aroused suspicion and started a search that might have disclosed all. The large loaves of bread were put in an unused bed in the place of bolsters; money, when there was any on hand, was rolled up in a strip of cotton which was tied as a string around a bunch of hoarhound that hung on a nail in the kitchen ceiling; the chickens were reared in a thicket some distance from the house, and, being fed there, seldom left it.

Although this house was searched repeatedly, by day and by night, by regulars and by guerrillas, by soldiers of the North and of the South, the only loss sustained were a few eggs, and this loss was not serious, for the eggs were stale.

THE “WALKING-BEAM BOY.”

BY L. E. STOFIEL

IN 1836 the steam-whistle had not yet been introduced on the boats of the western rivers. Upon approaching towns and cities in those days, vessels resorted to all manner of schemes and contrivances to attract attention. They were compelled to do so in order to secure their share of freight and passengers, so spirited was the competition between steamboats from 1836 to 1840. There were no railroads in the West (indeed there were but one or two in the East), and all traffic was by water. Consequently steamboat-men had all they could do to handle the crowds of passengers and the tons of merchandise offered them.

Shippers and passengers had their favorite packets. The former had their huge piles of freight stacked upon the wharves, and needed the earliest possible intelligence of the approach of the packet so that they might promptly summon clerks and carriers to the shore. The passengers, loitering in neighboring hotels, demanded some system of warning of a favorite steamer’s coming, that they might avoid the disagreeable alternative of pacing the muddy levees for hours at a time, or running the risk of being left behind.

Without a whistle, how was a boat to let the people know it was coming, especially if some of those sharp bends for which the Ohio River is famous intervened to deaden the splashing stroke of its huge paddle-wheels, or the regular puff, puff, puff, puff, of its steam exhaust-pipes?

The necessity originated several crude signs, chief among which was the noise created by a sudden escapement of steam either from the rarely used boiler waste-pipes close to the surface of the river, or through the safety-valve above. By letting the steam thus rush out at different pressures, each boat acquired a sound peculiarly its own, which could be heard a considerable distance, though it was as the tone of a mouth-organ against a brass-band, when compared with the ear-splitting roar of our modern steamboat-whistle. Townspeople of Cincinnati and elsewhere became so proficient in distinguishing these sounds of steam escapement that they could foretell the name of any craft on the river at night or before it appeared in sight.

It was reserved for the steamboat Champion to carry this idea a little further. It purposed to catch the eye of the patron as well as his ear. The Champion was one of the best known vessels plying on the Mississippi in 1836. It was propelled by a walking-beam engine. This style of steam-engine is still common on tide-water boats of the East, but has long since disappeared from the inland navigation of the West. To successfully steam a vessel up those streams against the remarkably swift currents, high-pressure engines had to be adopted generally. In that year, however, there were still a number of boats on the Mississippi and Ohio which, like the Champion, had low-pressure engines and the grotesque walking-beams.

One day it was discovered that the Champion’s escapement-tubes were broken, and no signal could be given to a landing-place not far ahead. A rival steamboat was just a little in advance, and bade fair to capture the large amount of freight known to be at the landing.

“I’ll make them see us, sir!” cried a bright boy, who seemed to be about fourteen years old. He stood on the deck close to where the captain was bewailing his misfortune.

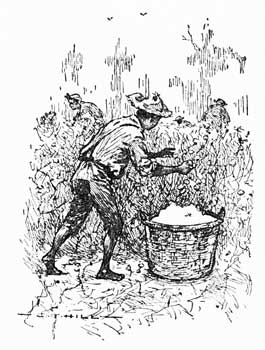

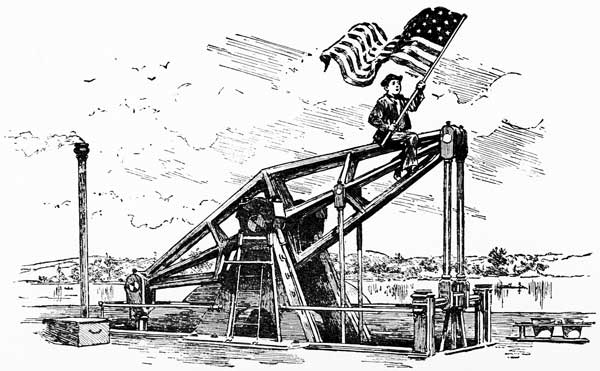

Without another word, the lad climbed up over the roof of the forecastle, and, fearlessly catching hold of the end of the walking-beam when it inclined toward him with the next oscillation of the engine, swung himself lithely on top of the machinery. It was with some difficulty that he maintained his balance, but he succeeded in sticking there for fifteen minutes. He had taken off his coat, and he was swinging it to and fro.

The plan succeeded. Although the other boat beat the Champion into port, the crowd there had seen the odd spectacle of a person mounted on the walking-beam of the second vessel, and, wondering over the cause, paid no attention to the landing of the first boat, but awaited the arrival of the other.

The incident gave the master of the Champion an idea. He took the boy as a permanent member of the crew, and assigned him to the post of “walking-beam boy,” buying for him a large and beautiful flag. Ever afterward, when within a mile of any town, the daring lad was to be seen climbing up to his difficult perch, pausing on the roof of the forecastle to get his flag from a box that had been built there for it. By and by he made his lofty position easier and more picturesque by straddling the walking-beam, well down toward the end, just as he would have sat upon a horse.

This made a pretty spectacle for those upon shore who awaited the boat’s arrival. They saw a boy bounding up and down with the great seesawing beam. For a second he would sink from view, but up he bobbed suddenly, and, like a clear-cut silhouette, he waved the Stars and Stripes high in the air with only the vast expanse of sky for a background. The vision was only for an instant, for both flag and boy would disappear, and — up again they came, before the spectator’s eye could change to another direction! This sight was novel — it was thrilling!

“I used to think if I could ever be in that young fellow’s place, I would be the biggest man on earth,” remarked a veteran river-man. Like thousands of others along the Mississippi and Ohio, he remembered that when a child he could recognize the Champion a mile distant by this unique signal.

After a while, though, other steamboats operating low-pressure engines copied the idea, and there were several “walking-beam boys” employed on the rivers, and their flags were remodeled to have some distinctive feature each. It was a perilous situation to be employed in, but I am unable to find the record of any “walking-beam boy” being killed or injured in the machinery. On the other hand, the very hazard of their duty, and the conspicuous position it gave them, made them popular with passengers and shippers, and so they pocketed many fees from Kentuckians, confections from Cincinnati folks, bonbons from New Orleans Creoles, and tips from Pittsburgers.

But at length, in 1844, the steam-whistle was introduced, and the “walking-beam boys” were left without occupation.

Notes:

- Second-feet. The volume of rivers is measured by the number of cubic feet of water flowing past a given point every second. The breadth of the river is multiplied by its average depth, and the ascertained speed of the current gives the number of cubic feet of water flowing by the point of measurement each second. This will explain the term second-feet. — Author’s note.

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

- Alexis Sneed

- Kacie Stringer

- Monica Stults

Source

Coffin, Helen Lockwood, et al. Southern Stories Retold from St. Nicholas. New York: De Vinne, 1907. Project Gutenberg. 6 Dec. 2007. Web. <http:// www. gutenberg.org/ files/ 23751/ 23751-h/ 23751-h.htm>.