James A Cowardin and

John D. Hammersley.

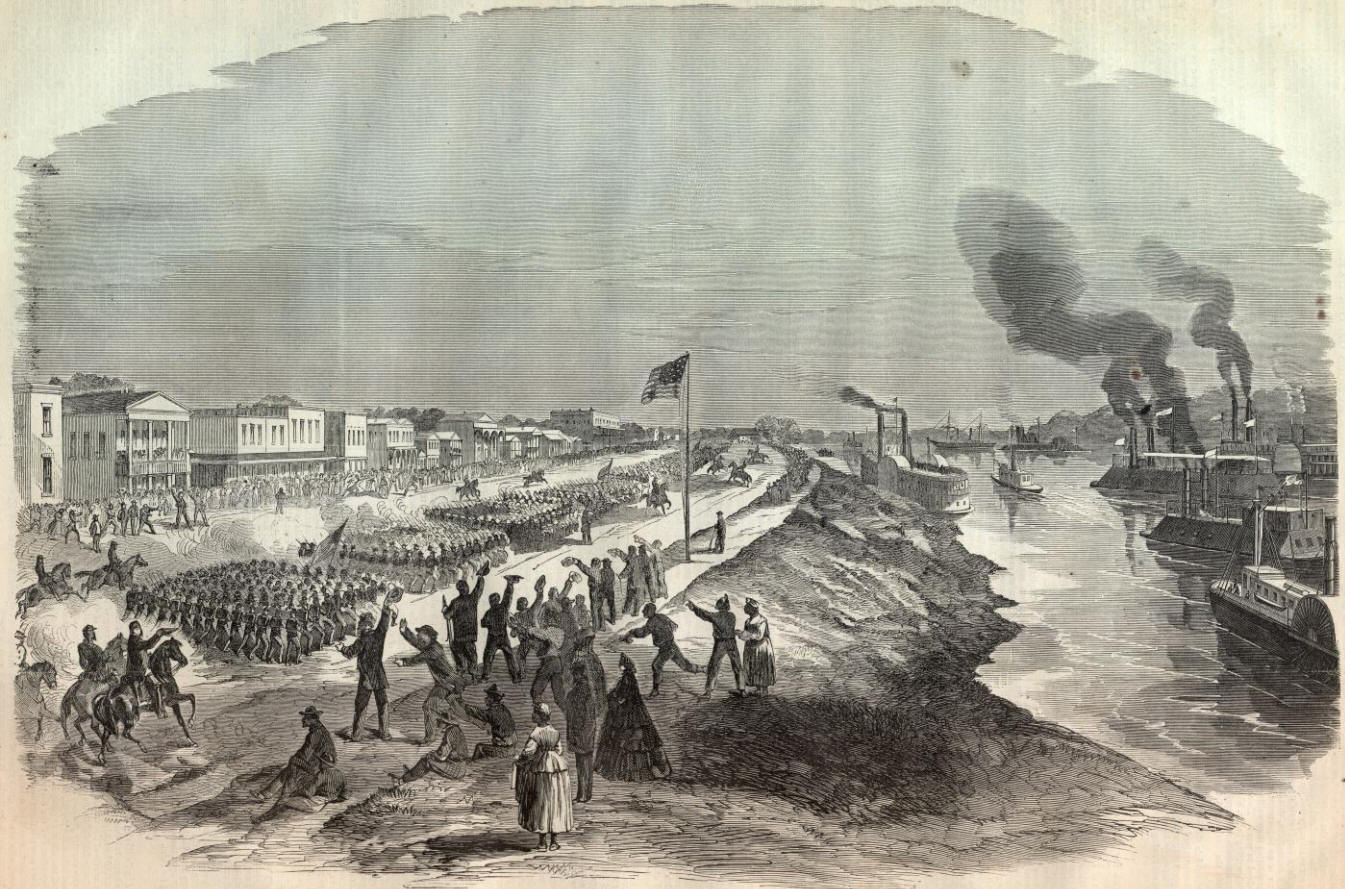

“Burning of Alexandria, Louisiana.”

A correspondent of the St. Louis Republican, writing from Cairo, Illinois, gives a description of the burning of Alexandria, Louisiana, by Banks's army, which we have never seen in the Southern prints. It is a very graphic sketch, and shows up the heartlessness and ferocity of our oppressors. It is peculiarly good reading just now, that the North is howling over Chambersburg. Here it is:

‘When gunboats were all over the falls, and the order to evacuate was promulgated, and the army nearly on the march, some of our soldiers, both white and black, as if by general understanding, set fire to the city in nearly every part, almost simultaneously. The flames spread rapidly increased by a heavy wind. Most of the houses were of wooden structure and soon devoured by the flames. Alexandria was a town of between four and five thousand inhabitants. All that part of the city north of the railroad was swept from the face of the earth in a few hours, not a building being left. About nineteenths of the town was consumed, comprising all the business part and all the fine residences, the “Ice House Hotel,” the Court-House all the churches, except the Catholic, a number of livery stables, and the entire front row of large and splendid business houses. The “Ice-House” was a large brick hotel, which must have cost one hundred thousand dollars, and which was owned by Judge Ariall, a member of the late Constitutional Convention, who voted for immediate and unconditional emancipation in Louisiana; which Convention also sent delegates to the Baltimore Convention. While Judge A. was serving the Administration, the Federal torch was applied to his house, his law office, his private and law library, and all his household goods and effects. All this property, be it remembered, has been protected for three years by the Confederates, who all the time knew the Judge’s Union proclivities. Hundreds of other instances may be cited of Union men who have suffered in like manner, et uno judice omne.

in Harper’s Weekly

June 20, 1863.

‘The scenes attending the burning of the city were appalling. Women, gathering their helpless babes in their arms, rushing frantically through the streets with their screams and cries, that would have melted the hardest heart to tears. Little boys and girls were running hither and thither crying for their mothers and fathers; old men, leaning on a staff for support to their trembling limbs, were hurrying away from the suffocating heat of their burning dwellings and homes. The fair and beautiful daughters of the South, whose fathers and brothers were in one army or the other; the frail and helpless wives and children of absent husbands and fathers, were, almost in the twinkling of an eye, driven from their burning houses into the streets, leaving everything behind but the clothes they then wore. Owing to the simultaneous burning in every part of the city, the people found no security in the streets, where the heat was so intense as almost to create suffocation. Everybody rushed to the river’s edge, being protected there from the heat by the high bank of the river. The gunboats lying at the landing were subjected to great annoyance, the heat being so great that the decks had to be flooded with water to prevent the boats from taking fire. Among those who thus crowded on the river bank were the wives, daughters and children, helpless, and now all houseless, of the Union men who had joined the Federal army since the occupation of Alexandria. Their husbands had already been marched off to the front, toward Simmesport, leaving their families in their old homes, but to the tender mercies of the Confederates.

The Federal torch had now destroyed their dwellings, their household goods and apparel, the last morsel of provisions, and left them starving and destitute. As might be expected, they desired to go along with the Federal army, where their husbands had gone. They applied to General Banks, with tears and entreaties, to be allowed to go aboard the transports. They were refused. They became frantic with excitement and rage. Their screams and piteous cries were heart-rending. With tears streaming down their cheeks, women and children begged and implored the boats to take them on board. The officers of the boats were desirous of doing so, but there was the peremptory order from General Banks not to allow any white citizens to go aboard. A rush would have been made upon the boats, but there stood the guard, with fixed bayonets, and none could mount the stage plank except they bore the special permit of the commanding general. Could any thing be more inhuman and cruel? But this is not all. General Banks found room on his transports for six or seven thousand negroes that had been gathered in from the surrounding country.

Cotton that had been loaded on transports to be shipped through the quartermaster to New Orleans, under Banks’s order, was thrown overboard to make room for negroes. But no room could be found for white women and children, whose husbands and brothers were in the Federal army, and whose houses and all had just been burned by the Federal torch! I challenge the records of all wars for acts of such perfidy and cruelty.

But there is still another chapter in this perfidious military and political campaign. Banks, on arriving at Alexandria, told the people that his occupation of the country was permanent; that he intended to protect all who would come forward and take the oath of allegiance; while those who would not were threatened with banishment and confiscation of property. An election was held, and delegates were sent to the Constitutional Convention, then in session at New Orleans. A recruiting officer was appointed, and over a thousand white men were mustered into the United States service. Quite a number of permanent citizens of Alexandria took the oath and were promised protection. Their houses and other property have now all been reduced to ashes, and they turned out into the world with nothing — absolutely nothing, save the amnesty oath! They could not now go to the Confederates and apply for charity. They, too, applied to General Banks to be allowed to go aboard the transports and go to New Orleans. They were refused in every instance! Among those who applied was a Mr. Parker, a lawyer of feeble health, who had been quite prominent making speeches since the Union occupation in favor of the emancipation, unconditional Union, and the suppression of the rebellion. Permission to go on a transport was refused him. He could not stay, and hence, feeble as he was, he went afoot with the army. Among the prominent citizens who took the oath was John K. Elgee, of Alexandria.

Before the return of the army from Grand Ecore, Judge Elgee went to New Orleans, leaving his family behind, expecting to return. He was not able to do so before the evacuation of Alexandria. Judge Elgee is one of the most accomplished and able men of the South. A lawyer by profession, he occupied a prominent position, both politically and socially, and had immense influence. So great stress was placed upon his taking the oath that one of our bands serenaded him at his residence, and General Grover and General Banks honored him in every way possible. During my stay in Alexandria, I had occasion to call upon the Judge at his residence, and at his office — which were both in the same building — on business. His law and literary library occupied three large rooms — being as fine a collection of books as I ever saw. His residence was richly and tastefully furnished — a single painting cost twelve hundred dollars. In his absence, the Government he had sworn to support, and which had promised him protection, allowed its soldiers to apply the torch to his dwelling and turn his family into the streets. — His fine residence, with all its costly furniture, his books, papers, and his fine paintings, were burned up. It may be that many of the last-named articles will yet find their way to the North, having been rescued from the flames by pilferers and thieves; for where arson is resorted to, it is generally to cover theft.

J. Madison Wells, the Lieutenant-Governor of Louisiana, elected with Hahn, by General Bank’s orders, was not spared. He had been a Union man from the beginning. He had a splendid residence in Alexandria, well and richly furnished, at which his own and his son’s family resided. His son was absent in New Orleans, attending the Constitutional Convention, of which he was a member, and in which he voted for abolition and all the ultra measures; but that did not secure his family the protection of the government. All was burned. Thousands of people — men, women and children — were, in a few short hours, driven from comfortable homes into the streets.

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Cowardin, James A., and John D. Hammersley “Burning of Alexandria, LA.” The Daily Dispatch [Richmond]: August 11, 1864. Richmond Dispatch. Microfilm. Ann Arbor, Mi: Proquest. 1 microfilm reel; 35 mm.