Hon. Gaspar Cusachs

"Lafitte, the Louisiana Pirate and Patriot"

|

Historical Quarterly

LAFITTE, THE LOUISIANA PIRATE AND PATRIOT ———— • ———— A Paper by Hon. Gaspar Cusachs President of the Louisiana Historical Society and Read by him before the Society ———— • ———— December 20, 1919 |

So many demands are made on the Louisiana History Society for information concerning the career and death of Lafitte that I have compiled this sketch from various sources and to some extent from De Bow's Review. James Dunwody Brownson De Bow, who was born in 1820, began his literary career in the Southern Quarterly Review, published in Charleston, South Carolina. His contributions were generally of a historical, statistical or political nature. His articles on the Northern Pacific, California and Oregon and on the Oregon Question attracted much attention and became the subject of debate in the French Chamber of Deputies. Forstall, Gayarr and Dimitry sympathized in De Bow's "progress and public spirit" and with these he became one of the founders of the Louisiana Historical Society and, afterwards, a member of the New Orleans Academy of Sciences. His Review was founded about 1845. De Bow contemplated writing a history of Louisiana, and with that view collected historical notes. When he abandoned this idea he published this collected matter through several numbers of his Review, which continued until the end of 1867. The Sketch of Lafitte taken from the Review of 1851, is the most complete ever written of a man who combined in his person the accomplishments of a gentleman with the daring and barbaric instincts of the corsair. Patriot, pirate, smuggler and warrior, there is no character to compare with him except that of Robin Hood, whom he surpassed in audacity and success. The fabulous treasures accumulated by him were squandered or were bountifully distributed, or were hidden away deep in the earth or in the sea marshes. At the junction of the Rigolets and Bayou Sauvage Lafitte built a platform or wharf on which to unload his merchandise and booty. There it remained for inspection by his purchasers.

Jean Lafitte, "The Terror of the Gulf of Mexico," was a Frenchman and born at St. Malo, about the year 1781. He was tall, finely formed, and in his pleasant moods was always agreeable and interesting. When conversing upon a serious subject, he would stand for hours with one eye shut; at such times, his appearance was harsh.

|

|

Painting by R. Telfer WikiGallery

|

From his earliest boyhood, he loved to "play with old ocean's hoary locks"; and long before he had reached the age of manhood, he had made several voyages to different seaports of Africa and Europe. With a suavity of manners and apparent gentlemanly disposition, combined with a majestic deportment, and undoubted courage, he swayed the boisterous passions of those rude, untutored tars, of whom he was the associate and chief. He was universally esteemed and respected by all his crew. They were taught to admit his commanding mien, his firmness, his courage, his magnanimity and professional skill.

Soon after attaining the age of majority, unchecked in his bold career, with an independent and restless spirit, his aspirations naturally looked forward to other avenues of ambition than the inglorious advocations of private life. To the chivalric spirit the ocean wave offers allurements that nothing on land can equal. There is a proud feeling, a strong temptation to tread the peopled deck of a majestic ship — to ride, as it were, the warrior steed of the ocean, triumphant over the mountain billows, and the conflict of mighty elements. True there may be many dangers — the mutiny — the storm — the wreck — all conspire to intimidate the inexperienced youth; but he soon learns to turn the imaginary dangers to delight; and looks to the honor, the fame, that awaits on such bold achievements. The world of waters lay before him — and he determined to seek that more congenial life upon its bosom, which had been denied him on land. Nor was it long before an opportunity was presented. A French East Indiaman, under orders for Madras, had taken her full cargo, and only awaited a favorable wind to weigh anchor. Through the influence of several respectable acquaintances and friends, he was offered the berth of chief mate, which he accepted. The vessel proceeded on her voyage, and nothing of consequence occurred till on doubling the Cape of Good Hope, she was struck by a squall, and suffered so much damage by the shock and a fire that broke out in the hold, and other accidents, that the Captain deemed it prudent to put in at the Mauritius to repair. During this period a quarrel had arisen between Lafitte and the Captain, of such an aggravated nature, that the former whose haughty spirit never brooked control, determined to abandon the ship the moment she touched port, and refused to proceed on the voyage. As soon, therefore, as the vessel landed at the Mauritius, he quitted it in disgust, and from this period may be dated his illegal connection with the ocean. His restless spirit had been inflamed by the romantic exploits of the hardy buccaneers of the time, whose names and deeds had resounded over every land and sea; and he resolved to imitate, if not surpass, their most brilliant actions, and leave a fame to the future that would not soon be forgotten.

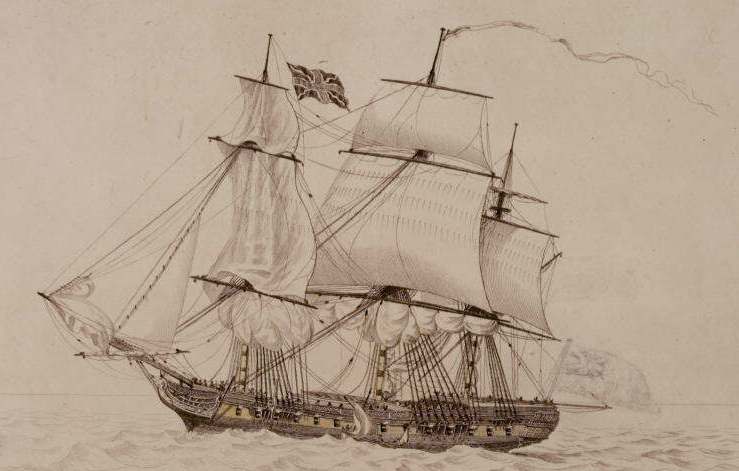

He did not remain long inactive. Several privateers were at this time fitting out at the island, the captaincy of one of which was offered Lafitte, and he accepted. She was a beautiful fast sailing vessel, and Lafitte spared no pains to make her the pride of the sea. Thus equipped, he attacked indiscriminately the weaker vessels of every nation, and though he accumulated vast sums of gold and silver, and enriched his crew, those sums were as soon squandered in profligacy and liberality; and his desires increasing with success, he resolved without hesitation, to embark in the slave-trade. While at the Seychelles, taking in a cargo of these miserable victims bound for the Mauritius, he was chased by an English man-of-war as far north as the equator; not having sufficient provisions to carry him to the French colony, with that energy, boldness and decision for which he was remarkable, he immediately put the helm about, and made for the Bay of Bengal, with the design of replenishing his stores from some English vessel then in port. He had not lost sight of his formidable pursuer many days, before he fell in with an English armed schooner with a numerous crew; which, after a sanguinary conflict, he captured. His own ship was but two hundred tons, carrying two guns only and twenty-six men, nineteen of whom he transferred to the schooner, of which he took the command and proceeded to cruise on the coast of Bengal. He had not cruised many days on this coast, teeming as it was with rich prizes, before he fell in with the Pagoda, an English East Indiaman, carrying a battery of twenty-six twelve-pounders, and manned with one hundred and fifty men. He so manoeuvred his vessel, as to induce the enemy to believe him a Ganges pilot; and as soon as he had the weather gauge of the ship, he suddenly boarded, cutlass in hand, and put all who resisted to the sword. Lafitte transferred his command to the captured vessel, and immediately made sail for the Mauritius, where he arrived, sold both prizes, and purchased a strong, well built ship, called "La Confiance," in which he put twenty-six guns, and two hundred and fifty men. Shortly after, (in the year 1807), he sailed in her for the coast of British India; and while cruising off the Sands Heads, fell in with the "Queen" East Indiaman, pierced for forty guns, and manned with a crew of about four hundred men. All eyes were upon her. She moved majestic on her way, as in defiance of his inferior force, and confident of her own strength. Yet Lafitte was not to be intimidated. He determined to take her. Accordingly, he addressed a powerful speech to his men — excited their wildest imaginations, and almost seemed to realize their most unbounded anticipations. This speech had the desired effect. Every man waved his hat and hand and cried aloud for action. The Queen bore down upon him with all the confidence of victory, and gave him a tremendous broadside, but owing to the height did but little execution. Before the commencement of the action, he had ordered his men to lay flat upon the deck, so that the crew of the Queen, believing that they were all killed or wounded, unwarily came alongside, with intention to grapple and board. At this moment Lafitte gave a whistle, and in an instant the deck was bristling with armed men. While the smoke yet prevailed, he ordered his hands into the tops and upon the yards, whence they poured down an incessant fire of shells, bombs, and grenades into the forecastle of the Indiaman, producing such havoc and slaughter among the crew, that they were obliged to retreat. At this critical juncture he beat to arms, and placing a favorite at the head of forty of his men with pistols in hand and daggers in their clenched teeth, ordered them to board. They rushed upon the deck, driving back the panic stricken crowd, who retreated to the steerage, and attempted to maintain a position. Lafitte now followed at the head of a second division of boarders, engaged the Captain of the Indiaman, who stood in a desperate position of defence, and after a severe conflict, slew him. Still the crew of the Queen maintained their post, and fought bravely. Lafitte impatient at their obstinacy, pointed at them a swivel, surcharged with grape and canister; when seeing extermination the result of further resistance, they surrendered. The vessel was then abandoned to plunder, and large amounts of gold and silver coin divided among the crew.

|

|

East Indiaman Wikipedia

|

The fame of this exploit spread over the Indian seas, and struck such a panic in the British commerce, that it was in the necessity of employing strong convoys to protect its trade. Seeing all hope of success cut off in this quarter, Lafitte concluded once more to return to his native France. On his way thither he doubled the Cape of Good Hope, and coasted along the Gulf of Guinea and the Bight of Benin. On his way he captured two valuable prizes laden with palm oil, ivory and gold dust. Arriving at St. Malo, the place of his birth, he disembarked, and shortly sold to advantage the "La Confiance," the two prizes and their valuable cargoes, and trod once more his native soil, opulent and renowned, where ten years previous he was scarcely known.

But he did not remain long inactive. His restless spirit, like a caged eagle, longed once more for his native element, the breeze, the battle, and the storm. Accordingly, he fitted out a brigantine, mounting twenty guns, and a crew of one hundred and fifty men, and made sail for Guadeloupe. On his way thither, and among the West India Islands, he continued the same successful career that had formerly attended his arms, captured several rich prizes which he disposed of on his arrival, and started for another cruise. While absent the English invested Guadeloupe by sea and by land, and as is well known the authorities there finally capitulated. During the blockade many privateers commissioned by the government of that island, were at sea, and after the capture, they dared not return. Lafitte was one of these, in consequence of which he sailed for Carthagena, which had but recently declared its independence of Spain. From the government of Carthagena these privateers received commissions to cruise against Spanish bottoms, and under the republican flag committed great havoc among the Spanish merchantmen trading in the Gulf of Mexico. Not being permitted to dispose of any of their prizes which were valuable and numerous, in any of the harbors or ports of the United States which were then at peace with Great Britain, and were bound to preserve the neutrality of their territory, they smuggled immense quantities of goods into New Orleans, through the inlets of Barataria, in direct violation of the revenue laws of the United States.

Under the denomination of Barataria, is comprised part of the coast of Louisiana, to the west of the mouth of the Mississippi, comprehended between Bastien Bay on the east, and the mouths of the Bayou Lafourche on the west. Adjacent to the sea are numerous lakes communicating with one another by several large bayous, with a great number of branches. Barataria Island which is formed by the largest of these bays of the same name, is situated about latitude 29°15´, Longitude 92°30´, and is as remarkable for the salubrity of the atmosphere, as for the superior quality of the shell fish with which the waters abound. Contiguous to the sea there is another island formed by the two arms or passes of this bay and the sea, called Grande Terre. This island is six miles in length, and from two to three miles in breadth, running parallel with the coast. The western entrance is called the Grande Passe, and has from nine to ten feet of water, through the harbor, the only secure one on the coast (formerly frequented by the pirates) and lies about two leagues from the open sea. Here amid the innumerable branches of bayous, passes, and inextricable cypress swamps, persons may lie concealed from the strictest scrutiny. In 1811, Lafitte fortified the eastern and western points of this island, and established a regular depot. Here the prizes were brought and sold to the inhabitants of the adjoining districts, who resorted to these places for the purpose of obtaining bargains in matters of trade and without being at all solicitous to conceal the object of their journey. No effective measures having been taken to expel the pirates they continued their depredations upon the Spanish commerce and sometimes ventured to attack vessels of other nations. They were generally regarded as pirates, but it is probable that most, if not all of them, were commissioned by the Carthagenian government.

|

|

Sunset over Barataria Bay National Journal

|

But it was impossible for this state of things to continue long without being checked by the general government, and particularly by the State of Louisiana. In order more effectually to break up and destroy these establishments, which were becoming daily more formidable by their boldness and reckless disregard to all law or threats the Governor thought proper to strike at the head. Lafitte soon after his arrival at Barataria, seems to have laid aside that boldness and audacity which characterized his former career. He had amassed an immense quantity of plunder, and he was obliged to have dealings with the merchants of the United States and the West Indies, and collect debts due him from the sale of booty, he was forced to be more circumspect, and cloak as much as possible his real character. Nevertheless, he was generally known to the inhabitants of the city of New Orleans from his immediate connection, and his once having been a fencing master in that city, of great repute, which art he had learned in Bonaparte's army, where he had been a captain.

Such was the notoriety inspired by his frequent and daring depredations, that the Governor offered five hundred dollars for his head; which Lafitte on hearing, answered in retaliation, by offering fifteen thousand dollars for the head of the Governor. The Governor, seeing his authority set at defiance, ordered out a company, under the command of a captain who had formerly served under Lafitte, and authorized him to burn and destroy all the property of the buccaneers and to bring them to New Orleans for trial. But the expedition proved disastrous. Lafitte suffered them to approach his fortifications without molestation, and whilst they flattered themselves with a speedy destruction of the pirates, they heard a sound like that of a boatswain's whistle, and before they could strike a blow, found themselves surrounded by armed men of superior force and all avenues of retreat cut off. It was on this occasion that Lafitte showed that characteristic nobleness and generosity of his nature which glitters like a jewel in the darkness of a thousand crimes. Instead of executing the man who had come to take away his life, and destroy all that was dear to him, he loaded him with presents and suffered him to return unmolested and in safety to New Orleans. This circumstance, together with other concurrent events, proved conclusively that the pirates were not to be taken by land, and the navy of the United States was yet too feeble to effect anything of consequence by sea, and had on one occasion been actually repulsed and was obliged to retreat before the overwhelming forces of Lafitte.

In the early part of 1814 Commodore Patterson of the United States Navy, received orders from Washington to disperse or destroy the illicit establishment at Barataria. Accordingly he left New Orleans on the 11th of June of that year, accompanied by Col. Ross, with a detachment of seventy-one picked men from the Forty-fourth regiment of the United States infantry. On the 12th he reached the schooner Caroline, which had been stationed below in Plaquemines, to accompany the expedition. On the 13th he formed a juncture with the gun-boats at the Balize, sailed from the South West Pass on the evening of the 15th, and at half past eight o'clock A.M. on the 16th, made the island of Barataria. He discovered a number of vessels in the harbor, some of which displayed Carthagenian colors. After remaining in the offing several hours, he discovered the enemy forming in a line of battle with six gun-boats and Sea Horse tender, mounting one six pounder and fifteen men, and a launch mounting one twelve pound carronade. The schooner Caroline was drawing too much water to cross the bar. At half past ten o'clock he perceived several smokes along the coast as signals, and at the same time a white flag hoisted on board a schooner at the fort, an American flag at the main-mast head, and a Carthagenian flag at her topping lift. He replied by a white flag at his main. At eleven o'clock discovering that the pirates had fired two of their best schooners, he hauled down the white flag and made the signal for battle at the same time hoisting a large white flag with the motto, "PARDON TO DESERTERS." At the approach of our forces, which were diminished by two of the gun-boats grounding on the bar, the Baratarians abandoned their vessels in the most disorderly flight. A launch and two barges were sent in pursuit of them, and though they were closely pursued, they succeeded in making their escape over the numerous bays and morasses of the adjacent district. About noon, however, that day, Commodore Patterson took possession of all their vessels in harbor, consisting of six fine schooners and one felucca, cruisers and prizes of the pirates, and one armed schooner under Carthagenian colors, found in company, and ready to oppose his command. Col. Ross now landed at the head of his troops, took possession of their establishment on shore, consisting of about forty houses of different sizes, badly constructed, and thatched with palmetto leaves.

|

|

Commodore Daniel Patterson Wikipedia

|

Commodore Patterson, in his report to the Secretary of War, goes on to say, "When I perceived the enemy forming their vessels into a line of battle, I felt confident from their number, and from their very advantageous position that they would have fought me. Their not doing so I regret. For had they done so, I should have been enabled more effectually to destroy or make prisoners of them and their leaders; but it is a subject of great satisfaction to me to have effected the object of my enterprise without the loss of a man.

The enemy had mounted on their vessels twenty pieces of cannon of different calibre, and as I have since learned, from eight hundred to one thousand men of all nations and colors. Early in the morning of the 20th, the Caroline which was anchored off shore about five miles, discovered a strange sail to eastward, and immediately gave chase. The enemy stood for Grande Terre with all sail set, and at half past eight hauled her wind off shore to escape; when Lieut. Spedding was sent with four boats armed and manned to prevent her passing the harbor. At 9 o'clock A.M. the chase fired upon the Caroline, which was returned, each vessel continuing to fire when their long guns would reach. At ten o'clock the chase grounded outside the bar, and the Caroline from the shoalness of the water, was obliged to haul her wind off for the shore and give up the chase. A fire was now opened upon the chase across the island from the gun vessels, and at half past ten o'clock she struck her colors and surrendered. She proved to be the armed schooner General Bolivar, consisting of an armament of one long brass eighteen pounder, one long brass six pounder, two twelve pounders, small arms, etc., and twenty-one packages of dry goods. On the afternoon of the 23rd Commodore Patterson got under headway with the whole squadron, in all seventeen vessels, (one having escaped the night previous) and on the next day arrived at New Orleans.

This expedition struck a panic among the freebooters, whose operations from this time were veiled in the deepest mystery, and conducted with the utmost caution and circumspection. The British early saw the importance of this hold, and after several ineffectual overtures to induce Lafitte to espouse their cause, they attacked him on several occasions with the intention of taking their prizes, and even their armed vessels; but were as frequently repulsed with loss and mortification. One of these attempts was on the 23rd of June, 1813, when a British sloop anchored at the entrance of the pass, and sent out her boats to endeavor to take two privateers anchored off Cat Island, but were repulsed with considerable loss. They, however, did not despair. On the 3rd of September, 1814, an Englishman-of-war, (Sophia), appeared off the harbor, and after firing on the inhabitants, hoisted a flag of truce. This conduct was so incomprehensible, that Lafitte set out for the ship in a small boat, to inquire the cause. When about half way between the ship and the shore, he saw a yawl let down from the stern of the ship, and make directly toward him. Suspecting treachery his first impulse was to flee — but seeing them close upon him, he resolved to brave it out and meet them. The yawl was soon alongside, well manned, displaying at her stern the British ensign, and at her bow a flag of truce. Captain Lockyer, commander of the man-of-war, hailed them, and asked if Lafitte was aboard, and being answered in the negative, gave him a package with instructions to guard it with great care, and to present it to Lafitte with his own hands, which he promised to perform. In the meantime, a strong inwardly current had drifted both boats near shore — lined with upwards of two hundred men — and Lafitte finding his opponent in his power, briefly told him, "I am he whom ye seek." As soon as landed, he conducted them to his house, amid the vociferations of his people demanding their lives upon the instant, or to send them to Jackson at New Orleans, to be hung as spies. Lafitte, whose influence and decision was greater than their indignation, dissuaded them from such rash acts, and pacified them with promises of speedy revenge. When the tumult was quelled, he opened the package which consisted of three papers, and read over their contents in silence. The first was a letter from Captain Percy, of his Majesty's sloop of war Hermes; the second was also a letter from Colonel Nicols, commander of the British land forces in Florida; the third, an inflammatory address to the Louisianians, clothed in florid eloquence and patriotic sentiment, calling on them to support the mother country.

As soon as Captain Lockyer perceived that Lafitte had finished reading the packages, conjecturing from his silence and looks that some doubts hung heavy on his mind, and knowing that no time was to be lost and no effort left untried, he regarded Lafitte with an anxious eye, and pushing up his point, spoke forcibly of the advantage, the fame, the glory, that would attend his decision in their favor; and as a further inducement, offered him the sum of thirty thousand pounds, to be paid as soon as he set foot at Pensacola. Lafitte hesitated but Captain Lockyer pressing his reasons, endeavored at once to bring his mind to a decision, which when once formed, he knew was irrevocable. He further offered him the rank of Post Captain in the British Navy, the command of a frigate, and the pardon for all past offenses. To such a man as Lafitte, in whom ambition, self aggrandizement and fame, were the predominant elements such offers might seem irresistible; but he had greater and nobler aims in view. He therefore demanded a few days for consideration, and though they remonstrated against delay with all the eloquence and persuasive language that might swerve his intent, he abruptly left them, and retired at a distance to avoid further repetition of argument, which if he had considered a moment, might have induced him to adopt a different course.

While absent, his men rushed upon Captain Lockyer and the other officer, and secured them as prisoners. As soon as Lafitte was informed of this outrage, he assembled his people by torchlight, and addressing them in an eloquent manner, showed the disgrace of violating the laws of hospitality, the total disregard to the flag of truce, and that by their mistaken policy they would lose forever the only favorable opportunity of discovering what were the enemy's intentions against the southern detachment of the American army. After this harangue, they were persuaded to let Lafitte act as he judged proper; and on the following morning he released the prisoners, and apologized for their incarceration. On the 4th of September, 1814, Lafitte wrote to Captain Lockyer, who was still cruising off the place, that he would require two weeks for consideration, and would at that time give him a definite answer; but that, all things considered, he thought he should accept his offer. On the same day he despatched another letter to Mr. Blanque of the Louisiana House of Representatives, inclosing all the papers the British officer had given him, as also a letter to Governor Claiborne, recapitulating the offers of the enemy, and showing, in strong language, the importance of the hold he occupied, and that it was both his desire and the desire of his men to enlist in the American cause, provided, the act of oblivion for all past offences be granted them. Those letters and papers were delivered by Mr. Blanque to the Governor, who immediately laid them before the Committee of Safety and Defence, over which he presided. The result was that Mr. Raucher, Lafitte's messenger, was sent back with instructions to Lafitte to take no final steps until the Committee could act and decide upon his proposition, and that in the meantime he should remain under the protection of the government.

|

|

Governor Claiborne Wikipedia

|

The two weeks having elapsed, Captain Lockyer again appeared in the offing; but Lafitte took no notice of the signals, and as soon as he disappeared — having received a passport from General Jackson — he embarked for New Orleans. He was taken to the Governor's reception room, and found him and General Jackson there alone. They both welcomed him with cordiality, and expressed their personal wishes that his request should be acceded to, and undertook to use their influence in the Council of State to that effect. When about to depart, the old hero grasped his hand with emotion, and as he reached the door, said, "Farewell — I trust the next time we meet will be in the ranks of the American army."

The Committee of Defence was convened, the papers were laid before it, and Lafitte's proposition was accepted. The Governor, hereupon issued his proclamation, inviting the Baratarians to join the standard of the United States, and was authorized to say, that, should their conduct in the field meet with the approbation of the Major General, that officer will unite with the Governor in a request to the President of the United States, to extend to each and every individual, so acting, a full pardon. Thus general orders were placed in the hands of Lafitte, who circulated them among his dispersed followers, most of whom readily embraced the conditions, and flocked to the standard of the United States. Lafitte's elder brother, who had previously been apprehended by the American authorities, and thrown into prison in New Orleans, was released, and permitted to join his companions.

The movements and operations of General Jackson in defence of New Orleans, are too well known to need repetition in this place. From the intelligence received, it was evident that the British fleet would make an effort to co-operate with the troops already landed. To prevent this, the forts on the river were strongly fortified, and filled with brave men to resist an attack in that direction. Major Reynolds and Captain Lafitte were ordered to put the passes of Barataria and Bayou Lafourche in the best possible state of defence, lest the enemy should by these entries, unite with its forces on the east side of the river, and attack Jackson's line on the flank and rear. This was accordingly done. Some of Lafitte's men were retained at Fort St. Philip, others were sent to the Fort of Petites Coquilles, and the Bayou St. John.

After these arrangements had been effected, from the 22nd of December to the 1st of January, the British were actively preparing to execute their designs, and several engagements took place; but nothing decisive was effected on either side. At length the ever memorable eighth dawned upon the plains of Chalmette. The mists of night were slowly melting away before the light of the winter morn. The awakening murmurs of the Camp arose, and the banners streamed and flapped along the breastwork, behind which stood the American army, waiting the signal of action. Suddenly, dark masses of the enemy were seen at the distance of nine hundred yards, moving rapidly across the plain, sublime and appalling enough to quicken the pulsations of the stoutest heart. Instantly a tremendous fire was opened on them from the batteries; but undaunted by the danger, the veterans pressed steadily forward amid a fearful carnage, making the earth smoke and thunder as they came, closing up their front as one after another fell, and only pausing when they reached the slippery edge of the glacis. Here it was found that the scaling ladders and fascines had been forgotten, and a halt occurred until they could be sent for and brought up. Along the whole range of the breastwork rolled a fierce devouring fire, emptying the saddles of those brave horsemen with fearful rapidity, and strewing the earth with the bodies of riders and steeds together. Unable to withstand the deadly fire of the American rifles, the enemy fell back in disorder from the foot of the parapet. At this crisis, amid the confusion of his bravest troops, Packenham, with a dauntless courage, galloped up, and dashing himself at the head of the 44th regiment, rallied his men and cheered them on, with uncovered head, to the very foot of the glacis. While cheering on his troops, a ball struck him, and he fell mortally wounded. Appalled by this sight, his brave troops recoiled. But their officers calling to remembrance the terrific assault of Badajos, brought them once again to the attack. With desperate but unavailing courage, they strove to force their way over the ditch and up the fatal entrenchments; but the rifles of the Americans met them at every step, and mowed them down in columns. Again and again did those splendid squadrons wheel to reform, and charge with deafening shouts, while their nodding plumes and glittering bayonets, like forests of steel, gleamed through the smoke of battle.

Led on by the gallant Keane, the Southern Highlanders, who had faced death in many a well fought field, continued to press on, notwithstanding the tempest of grape and shot which swept the plain. But that same wasting fire received them. The bulwarks of the American army seemed girded with fire, so rapid and constant were the discharges. At the head of his gallant troops fell the intrepid Keane. Burning to avenge the death of their commanders, the Highlanders rushed forward with inextinguishable fury. The whole plain was filled with marching squadrons of horse, galloping wildly, while the thunder of cannon and fierce rattle of musketry, amid which now and then was heard the blast of a thousand trumpets and the strains of martial music, filled the air. Still the veterans of the Peninsula pressed on, mounting on each other's shoulders to gain a foothold in the works, where they fought with the ferocity of frantic lions, mad with pain, rage and despair. Few, however, reached this point, and those who clambered up the entrenchments were bayoneted as they appeared. Three times the enemy advanced to the assault, and three times was he driven back in wild disorder.

The smoke of battle was rolling furiously over the host, and all seemed confusion and chaos in their ranks. The plain was already encumbered with two thousand dead and wounded, and the charging squadrons fell so fast that a rampart of dead bodies was soon formed around them. Along the whole length of the breastwork burst forth one incessant sheet of flame, and as fast as the heads of the columns appeared, they melted away before their murderous cannonade.

During the engagement the voice of Lafitte was heard along the lines, encouraging his men to action. He had been stationed at one of the important embrasures under the edge of the Mississippi, with Dominique, his countryman, as second in command. The French are among the first artillerists in the world, and these were some of the best of them. On that memorable day they achieved those brilliant feats of daring and valor worthy of their former fame. From their two batteries poured a terrific fire, which mowed down the ranks of the enemy like the harvest before the scythe of the reaper. In the heat of the engagement, a portion of the British troops, borne away by an irresistible ardor, and frantic with rage, rushed within the outposts, forcing a small party there to retreat. Before the batteries could be brought to bear, the enemy advanced with loud shouts of triumph at their brief success. In an instant Lafitte charged upon them with his men, outside the breastwork, which they had not yet gained, and dashing among the disordered ranks, raged like a lion amid his prey. He cut down two of the officers in command with his own arm, and his men with the rapidity of lightning, brandishing their sabres, burst through the thinned ranks of the enemy, who, appalled by the suddenness and efficacy of the movement, retired in confusion and dismay. At places where the fiercest struggles had been made, the dead were piled in heaps. Finding that victory was hopeless, General Lambert, on whom the command now devolved, gave orders to retreat, and fell back in great confusion. Thus closed one of the most sanguinary battles on record. The national pride was gratified not only in the preservation of the city, but in the reflection that its brave defenders had met and overthrown the conquerors of Peninsular Europe.

General Jackson, in his official report to the Secretary of War, did not fail to commend the gallant exploits and chivalrous daring of the brave band of Baratarians; and in consequence, President Madison, after peace, issued a proclamation, granting full pardon to all those who had been engaged in the defence of New Orleans.

|

|

General Andrew Jackson Museum of Florida History

|

Lafitte, restored to respectability, might have lived to an honorable old age, esteemed and respected by all around him. He traded awhile in and about New Orleans, but soon became dissatisfied and impatient of the restraints of civilization. His soul was as free as his native element, and he pined once more for the field of action, where his armament might ride in watchfulness over the world of waters, beneath the meteor flag that floats over every sea and fans every shore.

As early as 1812, he built a small village upon the site of the present city of Galveston, his own house being two stories and well furnished. All others were one story, and of a plainer construction. They procured their building materials from New Orleans, with which place they kept up a regular intercourse and commerce. In fact Lafitte boasted that he had made half of the merchants of that city rich. About the year 1819 the Governor of Galveston, a Mexican General, by the name of Longe, gave him a commission for the several vessels which he owned in partnership with those whom he had always retained in his employ; and Gen. Humbert, the subsequent governor, also gave him a commission for smaller boats, which he had constructed with a view of running far up the inland rivers. It is believed from this time that he kept up a regular life of robbing, smuggling and piracy, though he uniformly alleged that his depredations were committed alone on vessels sailing under the Spanish flag. Two of these boats having robbed a plantation on the Mermento river, belonging to an American citizen, were captured by the boats of the United States schooner Lynx, mounting five guns. Lafitte, to propitiate the government, hung at his yard-arm one of the men engaged in the affair, and disclaimed the intimation of having given such orders, or sanctioned their proceeding. Shortly after, however, the Lynx captured two of his vessels, discovered in smuggling along our coast; and it was now evident, that he must have had some previous knowledge of these acts, and have been an accomplice in the transaction.

Nevertheless he carried on his depredations with great secrecy and in a short time amassed immense sums of money, which were carried to the wild and uninhabited islands along the southern coast of Louisiana, and divided among the crew. Twenty thousand dollars concealed in kegs was discovered a few years ago on Caillou, by an individual named Wagner, (in company with six others), who was murdered by his comrades, and the treasure carried off, but nothing since has ever been heard of them. Gold bars, of great value, have since been discovered among the islands of Barataria, and it is probable that great treasures may be elsewhere concealed, for these pirates were all rich, and Lafitte is said to have spent sixty thousand dollars in fashionable society, during a short stay at Washington City.

About this time the Texas revolution burst forth, and many signal battles were fought on land and sea, until the lone star of the republic rose in refulgent beauty on the horizon of nations. Foremost in the cause of freedom was Lafitte. He commanded the "Jupiter," one of his own cruisers, the first vessel ever chartered by the new government, and by the very terror of his name, spread panic and dismay among the enemy. He was rewarded for his gallant services by being appointed governor of Galveston, a post of honor and distinction. Not long after, an American ship was boarded near our coast, and rifled of a large amount of specie; and the Jupiter having arrived at Galveston with a great amount of that commodity on board, Lafitte was immediately suspected, and one of our men of war, under Lieut. Madison, received orders to cruise off the coast, and vigilantly watch his manoeuvres. Lafitte became highly exasperated at this proceeding, and addressed a letter to the Commander, demanding by what authority he continued to lie before that port of which he was governor. The Commander made no reply, but still continued to keep a strict look-out and watch the operations of Lafitte, who burning with indignation, resolved to set his authority at defiance.

In the great storm of 1818, he lost many men and four vessels, three of which were foundered at sea, and one went ashore on Virginia point, on the opposite side of the bay. In consequence of which accident, he sent Lafage to New Orleans, to have built a new schooner which when finished and manned, mounted two guns as her heavy ordnance, and a crew of fifty men. As soon as their vessel was launched, Lafage took command and made a short cruise, in which he captured a vessel, and was proceeding with her under flowing sheets, to Lafitte's station, when he was met by the United States cutter, Alabama, on her way to the Mississippi. The cutter, suspecting the character of the schooner, bore down and hailed her, but was answered by a tremendous volley of gun-shot, which cut her rigging and seriously disabled six of her crew. A desperate action ensued, and Lafage, after losing the greater part of his bravest men, surrendered. The vessel and her prize were brought into our port at Bayou St. John, and the captured crew taken in irons to New Orleans, where at the next session of the Circuit Court of the United States, they were tried, condemned and executed.

Lafitte was highly exasperated at the result of this trial; he seemed to think that the whole world was against him, and resolved therefore to wage an indiscriminate war against all mankind. He had lately received a commission in the navy of the Colombian republic, and selling all his vessels, avowed his intention of my enlisting in the service. But he was secretly planning other great schemes. He called together his scattered crew, and with the proceeds of the sale of his vessels, bought a stout, large, fast-sailing brigantine, on which he placed an armament of sixteen guns, and a crew of one hundred and sixteen men. Thus equipped, he went forth like an evil spirit to war against the world.

But his eventful career was drawing to a close. A British sloop-of-war, cruising in the Gulf of Mexico, having heard of his intentions, kept a sharp look-out from the mast-head, with the hope of meeting him. One morning as an officer was sweeping the horizon with his glass, he discovered in the dim distance a suspicious looking sail, and immediately orders were given to make chase. As the sloop-of-war had the weather-gauge of the pirate, and could outsail her before the wind, she set her studding sails and crowded every inch of canvas. Lafitte, as soon as he ascertained the character of his opponent, furled his awnings, set his big square sail, and shot rapidly through the water. But the breeze freshening, the sloop continued to gain upon him, when finding escape impossible, he opened fire upon the ship, killing a number of men, and carrying away her fore-topmast. The man-of-war reserved her fire until close in with the brigantine, when she poured into her a broadside and a volley of small arms. The broad-side was too much elevated to hit the low hull of the brigantine, but did considerable execution among her rigging and crew, ten of whom were killed. At this juncture, the English came up and boarded her over the starboard bow. A terrible conflict now ensued.

Above the storm of battle, Lafitte's stern voice was heard and his red arm, streaming with gore, and grasping a shattered blade, was seen in the darkest of the conflict. The blood now ran in torrents from the scuppers and dyed the waters with a crimson stain. At light Lafitte fell, wounded desperately in two places. A ball had broken the bone of his right leg, a cutlass wound has penetrated his stomach. The Commander of the boarders was researched senseless on the deck close by Lafitte, and the desperate pirate, beholding his victim within his grasp, raised himself with difficulty and pain, dagger in hand, to slay the unconscious man. He threw his clotted locks aside, and drew his hand across his brow, to clear his sight of blood and mist, and raised the glittering blade above the heart of the dying man. But his brain was dizzy, his aim unsure, and the dagger descending, pierced the thigh of his powerless foe, and Lafitte fell back exhausted to the deck. Again reviving, with the convulsive grasp of death he essayed again to plunge the dagger to the heart of the foe, but as he held it over his breast, the effort to strike burst asunder the slender ligament of life — and Lafitte was no more.

Still the action raged with unabated fury: but so superior was the force of the assailants, that victory was no longer doubtful; yet so desperately had they been met that of a crew of one hundred and sixty, but sixteen survived the conflict. These were taken to Jamaica, and at a subsequent sitting of the Court of Admiralty, they were all condemned to death; ten, however, only were executed, the remaining six having been pardoned by the British government.

Thus fell Lafitte, a man superior in talent, in knowledge of his profession, in courage, and in physical strength. His memory is justly cherished by the Americans, for he rendered them great service in the perilous field; and there are many who believe him to be alive at this day, no authentic account of his death ever having been published. But the proceedings of the court, and testimony of the witnesses place this beyond a doubt, and, however dear his memory may be to some, we must not forget, that the road of honor was open to him; that he forsook its pleasant and peaceful enjoyments; in a word, all that might endear the remembrance of man on earth — to leave a career written in blood —

|

"A corsair's name to other times, Linked with one virtue, and a thousand crimes." |

The author of this biographical sketch of Lafitte, the "Corsair of the Gulf," assures us in a letter that it is "compiled from various sources — from individuals what have known and served under him, from an old number of the Galveston Civilian, from a note to Byron's Corsair, Frost's History, from public documents, letters, proclamations, and the most generally received accounts of his life and exploits in the books of pirates." — (Ed.)

"Barataria, 4th September, 18

"To Captain Lockyer:"Sir — The confusion which prevailed in our camp yesterday and this morning, and of which you have a complete knowledge, has prevented me from answering in a precise manner to the object of your mission; nor even at this time can I give you all the satisfaction that you desire; however, if you grant me a fortnight, I would be entirely at your disposal at the end of that time. This delay is indispensable to enable me to put my affairs in order. You may communicate with me by sending a boat at the eastern point of the pass, where I will be found. You have inspired me with more confidence than the admiral, your superior officer, and from you also I will claim in due time the reward of the services I may render you."

|

"Yours, &c., Signed: "J. LAFITTE." |

"Barataria, September 4,

"To Governor Claiborne:

"Sir — In the firm persuasion that the choice made of you to fill the office of first magistrate of this State, was dictated by the esteem of your fellow citizens and was conferred on merit, I confidently address you on an affair on which may depend the safety of this country. I offer you to restore to this State several citizens who, perhaps, in your eyes have lost their title. I offer you them, however, such as you would wish to find them, ready to exert their utmost efforts in defence of the country. This point of Louisiana which I now occupy is of great importance in the present crisis. I tender my services to defend it; and the only reward I ask is that a stop be put to the proscription against me and my adherents by an act of oblivion, for all that has been done hitherto. I am the stray sheep wishing to return to the fold. If you are thoroughly acquainted with the nature of my offences, I should appear to you much less guilty, and still worthy to discharge the duties of a good citizen. I have never sailed under any flag but that of the republic of Carthagena, and my vessels are perfectly regular in that respect. If I could have brought my lawful prizes into the ports of this State, I should not have employed the illicit means that have caused me to be proscribed. I decline saying more on the subject, until I have the honor of your Excellency's answer, which, I am persuaded can only be dictated by wisdom. Should you not answer favorably to my ardent desires, I declare to you that I will instantly leave the country, to avoid the imputation of having co-operated towards an invasion on this point, which cannot fail to take place, and rest assured in the acquittal of my conscience.

|

"I have the honor to be, your Excellency, &c., Signed: "J. LAFITTE." |

The President's Proclamation.

"Among the many evils produced by the war, which, with little intermission, have afflicted Europe, and extended their ravages into other quarters of the globe for a period exceeding twenty years, the dispersion of a considerable portion of the inhabitants of different countries in sorrow and in want, has not been the least injurious to human happiness, nor the least severe trial of human virtue. "It has been long ascertained that many foreigners, flying from the danger of their own home, and that some citizens, forgetful of their duty, have co-operated in forming an establishment on the island of Barataria, near the mouth of the river Mississippi, for the purpose of a clandestine and lawless trade; the government of the United States caused the establishment to be broken up and destroyed; and having obtained the means of designating the offenders of every description, it only remained to answer the demands of justice by inflicting an exemplary punishment. "But it has since been represented that the offenders have manifested a sincere penitence; that they have abandoned the prosecution of the worst cause for the support of the best, and, particularly, that they have exhibited, in the defence of New Orleans, unequivocal traits of courage and fidelity. Offenders, who have refused to become the associates of the enemy in the war, upon the most seducing terms of invitation; and who have aided to repel his hostile invasion of the territory of the United States, can no longer be considered as objects of punishment, but as objects of a generous forgiveness. "It has, therefore, been seen, with great satisfaction, that the General Assembly of the State of Louisiana earnestly recommend those offenders to the benefit of a full pardon; and in compliance with that recommendation, as well as in consideration of all the other extraordinary circumstances of the case, I, (James Madison), President of the United States of America, do issue this proclamation, hereby granting, publishing and declaring, a free and full pardon of all offences committed in violation of any act or acts of the Congress of the said United States, touching the revenue trade and navigation thereof, or touching the intercourse or commerce of the United States with foreign nations at any time before the eight day of January, in the present year, one thousand eight hundred and fifteen, by any person or persons whatever, being inhabitants of New Orleans and the adjacent country, during the invasion thereof as aforesaid. "And I do hereby further authorize and direct all suits, indictments and prosecutions for fines, penalties and forfeitures against any person or persons, who shall be entitled to the benefit of this full pardon, forthwith to be stayed, discontinued and repealed: All civil officers are hereby required, according to the duties of their respective stations, to carry this proclamation into immediate and faithful execution. "Done at the City of Washington, the sixth day of February, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifteen, and of the Independence of the United States the thirty-ninth. "By the President, Signed: "JAMES MADISON. "James Monroe, Acting Secretary of State.""To the Commander of the American Cruiser off the Port of Galveston: "Sir — I am convinced that you are a cruiser of the navy, ordered by your government, I have therefore deemed it proper to inquire your intention. I shall by this message inform you, that the port of Galveston belongs to, and is in possession of the republic of Texas, and was made a port of entry the 9th of October last. And whereas the Supreme Congress have thought proper to appoint me as governor of this place, in consequence of which, if you have any demands on said government, or persons belonging to or residing in the same, you will please to send an officer with such demands, whom you may be assured, will be treated with the greatest politeness, and receive every satisfaction required. But if you are ordered, or should you attempt to enter this port in a hostile manner, my oath and my duty to the government compels me to rebut your intentions at the expense of my life. "To prove to you my intentions towards the welfare and harmony of your government, I send enclosed the declarations of several prisoners, who were taken into custody yesterday, and by a court of inquiry appointed for that purpose, were found guilty of robbing the inhabitants of the United States of a number of slaves and specie. The gentlemen bearing this message will give you any reasonable information relating to this place, that may be required. Signed: "J. LAFITTE."

Notes

Source

SourceCusachs, Gaspar. "Lafitte, the Louisiana Pirate and Patriot." Louisiana Historical Quarterly 2.4 (1919): 418-38. Archives.org. Web. 31 Oct. 2012. <http:// archive.org/ stream/ louisiana histor 00unkngoog# page/n432/ mode/2up> .

Anthology of Louisiana

Literature

|