George Robert Gleig.

A Narrative of the Campaigns of the British Army at Washington, Baltimore, and New Orleans.

The following Letters were not the produce of mere recollection, but were formed from the substance of a journal kept, with considerable care, during the progress of the events which they record. Some of these were, indeed, too striking to have been easily forgotten, as to their general character; but for the detail of minute circumstances, which, it is hoped, will be found to possess some degree of interest, memory alone would not have been a secure or sufficient guide. The introductory and final forms of epistolary writing have been purposely omitted; but for all the particulars, however extraordinary, the Author is thus: enabled fairly to pledge his credit. The Letters will perhaps, obtain the more attention, as conveying the first detailed account of this concluding expedition of the war.

Philadelphia, July 5, 1821.

The following work, although more fair and candid, in most particulars, than the generality of those published in Europe respecting this country, contains some important errors and misstatements, which have called forth various animadversions in different parts of the United States. The American editor hopes he has performed an acceptable service to his fellow citizens, by presenting, in a condensed form, the most important of those animadversions, with such interlocutory remarks as appeared necessary to connect. and illustrate them.

But the period granted for such indulgence was not of long duration, for, on the following morning, the Tonnant, Ramilies, and two brigs, stood to sea, and on the 26th, the rest of the fleet got under weigh, and followed the Admiral. It is impossible to conceive a finer sea-view than this general stir presented. Our fleet amounted now to upwards of fifty sail, many of them vessels of war, which shaking loose their topsails, and lifting their anchors at the same moment, gave to Negril Bay an appearance of bustle such as it has seldom been able to show. In half an hour all the canvas was set, and the ships moved slowly and proudly from their anchorage, till having cleared the headlands, and caught the fair breeze which blew without, they bounded over the water with the speed of eagles, and long before dark, the coast of Jamaica had disappeared.

There is something in rapidity of motion, whether it be along a high road, or across the deep, extremely elevating; nor was its effect unperceived on the present occasion. It is true, that there were other causes for the high spirits which wow pervaded the armament, but I question if any one was more efficient in their production, than the astonishing rate of our sailing. Whether the business we were about to undertake would prove bloody, or the reverse, entered not into the contemplation of a single individual in the fleet. The sole subject of remark was the speed with which we got over the ground, and the probability that existed of our soon reaching the point of debarkation. The change of climate, likewise, was not without its effect in producing pleasurable sensations. The farther we got from Jamaica, the more cool and agreeable became the atmosphere; which led us to hope that, in spite of its southern latitude, New Orleans would not be found so oppressively hot as we had been taught to expect.

The breeze continuing to last without interruption, on the 29th we came in sight of the island of Grand Cayman. This is a small speck in the middle of the sea, lying so near the level of the water, as to be unobservable at any considerable distance. Though we passed along with prodigious velocity, a canoe nevertheless ventured off from the shore, and making its way through waves which looked as if they would swallow it up, succeeded in reaching our vessel. It contained a white man and two negroes, who brought off a quantity of fine turtle, which they gave us in exchange for salt pork; and so great was the value put upon salt provisions, that they bartered a pound and a half of the one for a pound of the other. To us the exchange was very acceptable, and thus both parties remained satisfied with their bargain.

Having lain to till our turtle merchants left us, we again filled and stood our course. The land of Cayman was soon invisible; nor was any other perceived till the 2d of December, when the western shores of Cuba presented themselves. Towards them we now directed the ship’s head, and reaching in within a few miles of the beach, coasted along till we had doubled the promontory which forms one of the jaws of the Mexican gulf. While keeping thus close to the shore, our sail was more interesting than usual, for though this side of Cuba is low, it is still picturesque, from the abundance of wood with which it is ornamented. There are likewise several points where huge rocks rise perpendicularly out of the water, presenting the appearance of old baronial castles, with their battlements and lofty turrets; and it will easily be believed, that none of these escaped our observation. The few books which we had brought to sea, were all read, many of them twice and three times through; and there now remained nothing to amuse, except what the variety of the voyage could produce.

But the shores of Cuba were quickly passed, and the old prospect of sea and sky again met the gaze. There was, however, one circumstance, from which we experienced a considerable diminution of comfort. As soon as we entered the gulf, a short disagreeable swell was perceptible; differing in some respects from that in the Bay of Biscay, but to my mind infinitely more unpleasant. So great was the motion, indeed, that all walking was prevented; but as we felt ourselves drawing every hour nearer and nearer to the conclusion of our miseries, this additional one was borne without much repining. Besides, we found some amusement in watching from the cabin windows, the quantity and variety of weed with which the surface of this gulf is covered. Where it originally grows, I could not learn, though I should think most probably in the gulf itself; but following the course of the stream, it floats continually in one direction; going round by the opposite coast of Cuba, towards the banks of Newfoundland, and extending sometimes as far as Bermuda and the Western Isles.

It is not, however, my intention to continue the detail of this voyage longer than may be interesting; I shall therefore merely state, that, the wind and weather having undergone some variations, it was the 10th of December before the shores of America could be discerned. On that clay we found ourselves opposite to the Chandeleur Islands, and near the entrance of Lake Borgne. There the fleet anchored, that the troops might be removed from the heavy ships, into such as drew least water; and from this and other preparations, it appeared, that to ascend this lake was the plan determined upon.

But before I pursue my narrative farther, it will be well if I endeavour to give some account of the situation of New Orleans, and of the nature of the country against which our operations were directed.

New Orleans is a town of some note, containing from twenty to thirty thousand inhabitants. It stands upon the eastern bank of the Mississippi, in 30� north latitude, and about 110 miles from the Gulf of Mexico. Though in itself unfortified, it is difficult to conceive a place capable of presenting greater obstacles to an invader; and at the same time more conveniently situated with respect to trade. Being built upon a narrow neck of land, confined on one side by the river, and on the other by impassable morasses, its means of defence require little explanation; and as these morasses extend only a few miles, and are succeeded by Lake Pontchartrain, which again communicates through Lake Borgne, with the sea, its peculiar commercial advantages must be equally apparent. It is by means of the former of these Lakes, indeed, that intercourse is maintained between the city and the northern parts of West Florida, of which it is the capital ; a narrow creek, called, in the language of the country, a Bayou or Bayouke, navigable for vessels drawing less than six feet water, running up through the marsh, and ending within two miles of the town. The name of this creek is the Bayouke of St. John, and its entrance is defended by works of considerable strength.

But to exhibit its advantages in a more distinct point of view, it will be necessary to say a few words respecting that mighty river upon which it stands. The Mississippi, (a corruption of the word Mechasippi, signifying, in the language of the natives, ‘the father of rivers,’) is allowed to be inferior, in point of size and general navigability, to few streams in the world. According to the Sioux Indians, it takes its rise from a large swamp, and is increased by many rivers emptying themselves into its course as far as the fall of St. Anthony, which, by their account, is upwards of seven hundred leagues from its source. But this fall, which is formed by a rock thrown across the channel, of about twelve feet perpendicular height, is known to be eight hundred leagues from the sea; and Pontchartrain. They are both extremely shallow, varying from 12 to 6 feet in depth. Therefore the whole course of the Mississippi, from its spring to its mouth, may be computed at little short of 5,000 miles.

Below the fall of St. Anthony, again, the Mississippi is joined by a number of rivers considerable in point of size, and leading out of almost every part of the continent of America. These are the St. Pierre, which comes from the west; St. Croix, from the east; the Moingona, which is said to run 150 leagues from the west, and forms a junction about 250 below the fall; and the Illinois, which rises near the Lake Michigan, 200 leagues east of the Mississippi.

But by far the most important of these auxiliary streams is the Missouri, the source of which is as little known as that of the Father of Rivers himself. It has been followed by traders upwards of 400 leagues, who traffic with the tribes which dwell upon its banks, and obtain an immense return for European goods. The mouth of this river is five leagues below that of the Illinois, and is supposed to be 800 from its source, which, judging from the flow of its waters, lies in a northwest direction from the Mississippi. It is remarkable enough, that the waters of this river are black and muddy, and prevail over those of the Mississippi, which, running with a clear and gentle stream till it meets with this addition, becomes from that time both dark and rapid.

The next river of note is the Ohio, which, taking its rise near Lake Erie, runs from the northeast to the southwest, and joins the Mississippi about seventy leagues below the Missouri. Besides this, there are the St. Francis, an inconsiderable stream, and the Arkansas, which is said to originate in the same latitude with Santa Fé in New Mexico, and which, holding its course nearly 300 leagues, falls in about 200 above New Orleans. Sixty leagues below the Arkansas, comes the Yazous from the northeast; and about fifty-eight nearer to the city, is the Rouge, so called from the colour of its waters, which are of a reddish dye, and tinge those of the Mississippi at the time of the floods. Its source is in New Mexico, and after running about 200 leagues, it is joined by the Noir thirty miles above the place where it empties itself into the Mississippi.

Of all these rivers, there is none which will not answer the purposes of commerce, at least to a very considerable extent; and as they join the Mississippi above New Orleans, it is evident that this city may be considered as the general mart of the whole. Whatever nation, therefore, chances to possess this place, possesses in reality the command of a greater extent of country than is included within the boundary line of the whole United States; since from every direction are goods, the produce of East, West, North, and South America sent down by the Mississippi to the Gulf. But were New Orleans properly supplied with fortifications, it is evident that no vessels could pass without the leave of its governor; and therefore is it that I consider that city as of greater importance to the American government, than any other within the compass of their territories.

Having said so much on its commercial advantages, let me now point out more distinctly than I have yet done, the causes which contribute to its safety from all hostile attempts. The first of these is the shallowness of the river at its mouth, and the extreme rapidity of the current. After flowing on in one prodigious sheet of water, varying in depth from one hundred to thirty fathoms, the Mississippi, previous to its joining the Mexican Gulf, divides into four or five mouths, the most considerable of which is encumbered by a sand-bank, continually liable to shift. Over this bank, no vessel drawing above seventeen feet water, can pass; when once across, however, there is no longer a difficulty in being floated; but to anchor is hazardous, on account of the huge logs which are constantly carried down the stream. Should one of these strike the bow of the ship, it would possibly dash her to pieces; while, independent of this, there is always danger of drifting, or losing anchors, owing to the number of sunken logs which the undercurrent bears along within a few feet of the bottom. All vessels ascending the river are accordingly obliged, if the wind be foul, to make fast to the trees upon the banks; because, without a breeze at once fair and powerful, it is impossible to stem the torrent.

But besides this natural obstacle to invasion, the mouth of the river is defended by a fort, which, from its situation, may be pronounced impregnable. It is built upon an artificial causeway, and is surrounded on all sides by swamps totally impervious, which extend on both sides of the river to a place called the Detour des Anglais, within twenty miles of the city. Here two other forts are erected, one on each bank. Like that at the river’s mouth, these are surrounded by a marsh, a single narrow path conducting from the commencement of firm ground to the gates of each. If, therefore, an enemy should contrive to pass both the bar and the first fort, he must here be stopped, because all landing is prevented by the nature of the soil; and however fair his breeze may have hitherto been, it will not now assist his farther progress. At this point the Mississippi winds almost in a circle, in so much that vessels which arrive are necessitated to make fast, till a change of wind occur.

From the Detour des Anglais towards New Orleans, the face of the country undergoes an alteration. The swamp does not, indeed, end, but it narrows off to the right, leaving a space of firm ground, varying from three to one mile in width, between it and the river. At the back of this swamp, again, which may be about six or eight miles across, come up the waters of Lake Pontchartrain, and thus a neck of arable land is formed, stretching for some way above the city. The whole of these morasses are covered, as far as the Detour, with tall reeds; a little wood now succeeds, skirting the open country, but this is only a mile in depth, when it again gives place to reeds. Such is the aspect of that side of the river upon which the city is built; with respect to the other, I can speak with less confidence, having seen it but cursorily. It appears, however, to resemble this in almost every particular, except that it is more wooded, and less confined with marsh. Both sides are flat, containing no broken ground, or any other cover for military movements; for on the open shore there are no trees, except a few in the gardens of those houses which skirt the river, the whole being laid out in large fields of sugar-cane, separated from one another by rails and ditches.

From this short account of the country, the advantages possessed by a defending army must be apparent. To approach by the river is out of the question, and therefore an enemy can land only from the Lake. But this can be done no where, exceptwhere creeks or bayous offer conveniences for that purpose, because the banks of the lake are universally swampy; and can hardly supply footing for infantry, far less for the transportation of artillery. Of these, however, there are not above one or two which could be so used. The Bayou of St. John is one; but it is too well defended, and too carefully guarded for any attempts; and the Bayou of Catiline is another, about ten miles below the city. That this last might be found useful in an attack, was proved by the landing effected by our army at that point; but what is the consequence? The invaders arrive upon a piece of ground, where the most consummate generalship will be of little avail. If the defenders can but retard their progress; which, by crowding the Mississippi with armed vessels, may very easily be done, the labour of a few days will cover this narrow neck with entrenchments; while the opposite bank, remaining in their hands, they can at all times gall their enemy with a close and deadly cannonade. Of wood, as I have already said, or broken ground which might conceal an advance, there exists not a particle. Every movement of the assailants must, therefore, be made under their eyes; and as one flank of their army will be as well defended by morass, as the other by the river, they may bid defiance to all attempts at turning.

Such are the advantages of New Orleans; and now it is only fair, that I should state its disadvantages: these are owing solely to the climate. From the swamps with which it is surrounded, there arise, during the summer months, exhalations extremely fatal to the health of its inhabitants. For some months of the year, indeed, so deadly are the effects of the atmosphere, that the garrison is withdrawn, and most of the families retire from their houses to more genial spots, leaving the town as much deserted, as if it had been visited by a pestilence. Yet, in spite of these precautions, agues and intermittent fevers abound here at all times. Nor is it wonderful that this should be the case; for independent of the vile air which the vicinity of so many putrid swamps occasions, this country is more liable than perhaps any other, to sudden and severe changes of temperature. A night of keen frost, sufficiently powerful to produce ice, a quarter of an inch in thickness, frequently follows a day of intense heat; while heavy rains and bright sunshine often succeed each other several times, in the course of a few hours. But these changes, as may be supposed, occur only during the winter; the summer being one continued series of intolerable heat and deadly fog.

Of all these circumstances, the conductors of the present expedition were not ignorant. To ready the forts which command the navigation of the river, it was conceived, was a task too difficult to be attempted; and for any ships to pass without this reduction, was impossible. Trusting, therefore, that the object of the enterprize was unknown to the Americans, Sir Alexander Cochrane and General Keane determined to effect a landing somewhere on the banks of the Lake; and pushing directly on to take possession of the town, before any effectual preparation could be made for its defence. With this view the troops were removed from the larger into the lighter vessels, and these, under convoy of such gun-brigs as the shallowness of the water would float, began on the 13th to enter Lake Borgne. But we had not proceeded far, when it was apparent that the Americans were well acquainted with our intentions, and ready to receive us. Five large cutters, armed with six heavy guns each, were seen at anchor in the distance, and as all endeavours to land, till these were captured, would have been useless, the transports and largest of the gun-brigs cast anchor, while the smaller craft gave chase to the enemy.

But these cutters were built purposely to act upon the Lake. They accordingly set sail, as soon as the English cruisers were within a certain distance, and running on, were quickly out of sight, leaving the pursuers fast aground. To permit them to remain in the hands of the enemy, however, would be fatal, because, as long as they commanded the navigation of the Lake, no boats could venture to cross. It was, therefore, determined at all hazards, and at any expense, to take them; and since our lightest craft could not float where they sailed, a flotilla of launches and ship’s barges was got ready for the purpose.

This flotilla consisted of fifty open boats; most of them armed with a carronade in the bow, and well manned with volunteers from the different ships of war. The command was given to Captain Lockier, a brave and skilful officer, who immediately pushed off; and about noon, came in sight of the enemy, moored fore and aft, with the broadsides pointing towards him. Having pulled a considerable distance, he resolved to refresh his men before he hurried them into action; and, therefore, letting fall grapplings just beyond reach of the enemy’s guns, the crews of the different boats cooly ate their dinner.

As soon as that meal was finished, and an hour spent in resting, the boats again got ready to advance. But, unfortunately, a light breeze which had hitherto favoured them, now ceased to blow, and they were accordingly compelled to make way only with the oar. The tide also ran strong against them, at once increasing their labour, and retarding their progress; but all these difficulties appeared trifling to British sailors; and giving an hearty cheer, they moved steadily onward in one extended line.

It was not long before the enemy’s guns opened upon them, and a tremendous shower of balls saluted their approach. Some boats were sunk, others disabled, and many men were killed and wounded; but the rest pulling with all their mieht and occasionally returning the discharges from their comrades, succeeded, after an hour’s labour, in closing with the Americans. The marines now began a deadly discharge of musketry; while the seamen, sword in hand, sprang up the vessels’ sides in spite of all opposition; and sabring every man that stood in the way, hauled down the American ensign, and hoisted the British flag in its place.

One cutter, however, which bore the commodore’s broad pennant, was not so easily subdued. Having noted its pre-eminence, Captain Lockier directed his own boat against it; and happening to have placed himself in one of the lightest and fastest sailing barges in the flotilla, he found himself along side of his enemy, before any of the others were near enough to render him the smallest support. But nothing dismayed by odds so fearful, the gallant crew of this small bark, following their leader, instantly leaped on board the American. A desperate conflict now ensued, in which Captain Lockier received several severe wounds; but after fighting from the bow to the stern, the enemy were at length overpowered; and other barges coming up to the assistance of their commander, the commodore’s flag shared the same fate with the others.

Having thus destroyed all opposition in this quarter, the fleet again weighed anchor, and stood up the Lake. But we had not been many hours under sail, when ship after ship ran aground : such as still floated were, therefore, crowded with the troops from those which could go no farther, till finally the lightest vessel stuck fast; and the boats were of necessity hoisted out, to carry us a distance of upwards of thirty miles. To be confined for so long a time, as the prosecution of this voyage would require, in one posture, was of itself no very agreeable prospect; but the confinement was but a trifling misery, when compared with that which arose from the change in the weather. Instead of a constant bracing frost, heavy rains, such as an inhabitant of England cannot dream of, and against which no cloak will furnish protection, began. In the midst of these were the troops embarked in their new and straitened transports, and each division, after an exposure of ten hours, land ed upon a small desert spot of earth, called Pine Island, where it was determined to collect the whole army, previous to its crossing over to the main.

Than this spot, it is scarcely possible to imagine any place more completely wretched. It was a swamp, containing a small space of firm ground at one end, and almost wholly unadorned with trees of any sort or description. There were, indeed, a few stinted firs upon the very edge of the water; but these were so diminutive in size, as hardly to deserve an higher classification than among the meanest of shrubs. The interior was the resort of wild ducks and other water fowl; and the pools and creeks with which it was intercepted abounded in dormant aligators.

Upon this miserable desert, the army was assembled, without tents or huts, or any covering to shelter them from the inclemency of the weather : and in truth we may fairly affirm, that our hardships had here their commencement. After having been exposed all day to a cold and pelting rain, we landed upon a barren island, incapable of furnishing even fuel enough to supply our fires. To add to our miseries, as night closed, the rain generally ceased, and severe frosts set in; which congealing our wet clothes upon our bodies, left little animal warmth to keep the limbs in a state of activity and the consequence was, that many of the wretched negroes, to whom frost and cold were altogether new, fell fast asleep, and perished before morning.

For provisions, again, we were entirely dependent upon the fleet. There were here no living creatures which would suffer themselves to be caught; even the water-fowls being so timorous, that it was impossible to approach them within musket shot. Salt meat and ship biscuit therefore, our food, moistened by a small allowance of rum; fare, which, though no doubt very wholesome, was not such as to reconcile us to the cold and wet under which we suffered.

On the part of the navy, again, all these hardships were experienced in a four-fold degree. Night and day were boats pulling from the fleet to the island, and from the island to the fleet; for it was the 21st before all the troops were got on shore; and as there was little time to inquire into men’s turns of labour, many seamen were four or five days continually at the oar. Thus, they had not only to bear up against variety of temperature, but against hunger, fatigue, and want of sleep in addition; three as fearful burdens as can be laid upon the human frame. Yet, in spite of all this, not a murmur nor a whisper of complaint could be heard throughout the whole expedition. No man appeared to regard the present, while every one looked forward to the future. From the General down to the youngest drum-boy, a confident anticipation of success seemed to pervade all ranks; and in the hope of an ample reward in store for them, the toils and grievances of the moment were forgotten. Nor was this anticipation the mere offspring of an over-weaning confidence in themselves. Several Americans had already deserted, who entertained us with accounts of the alarm experienced at New Orleans. They assured us that there were not at present 5,000 soldiers in the State; that the principal inhabitants had long ago left the place; that such as remained were ready to join us as soon as we should appear among them; and that, therefore, we might lay our account with a speedy and bloodless conquest. The same persons likewise dilated upon the wealth and importance of the town, upon the large quantities of government stores there collected, and the rich booty which would reward its capture; subjects well calculated to tickle the fancy of invaders, and to make them unmindful of immediate afflictions, in the expectation of so great a recompense.

While the troops were thus assembling, an embassy was dispatched to the Chactaws, a tribe of Indians with whom our government chanced to be in alliance. Along with this embassage I had the good fortune to be sent; and a most amusing expedition it proved to be.

We set sail in a light schooner, and running along the coast till we came to a district not far from Apalachicola, pushed our vessel into a creek, and landed. Proceeding a short distance from the shore, we arrived at a considerable settlement of these savages; as singular a collection of human habitations as ever I beheld. It consisted of upwards of thirty huts, composed of reeds and branches of trees, erected in the heart of a wood, without any regard to form or regularity; each hut standing at a short distance from the rest. At the doors of these huts sat the men, in a posture of the most perfect indolence, with their knees bent upwards, their elbows resting upon their knees, and their chins upon their hands. Not a word was interchanged between man and man, while they appeared to be totally absorbed, each in his own private contemplations. The women, however, were differently employed. Upon them, indeed, all the toil of domestic economy seemed to have devolved; for they were carrying water, splitting wood, lighting fires, and cooking provisions. Some children, though not so many as one would have expected, from the extent of the settlement, were likewise playing about; but their sports had little of the spirit of European games; and frequently ended in quarrels and combats.

On our approach, two men rose from the doors of their huts, and came to meet us. These proved to be the chief, and the principal warrior of the tribe; the first an elderly infirm person, and the last a man of fierce countenance, probably about the age of forty. They were not, however, distinguished from their countrymen by any peculiarity of dress; being arrayed, as the others were, in buffalo hides, with a loose scarf of cotton thrown over one shoulder, and wrapped round their loins; the size of their ornaments alone indicated that they were persons of consequence, the king having two broad pieces of gold suspended from his ears, and bracelets of the same metal round his wrists; while the warrior’s ears were graced with silver rings, and a whole Spanish dollar hung from his nose. With these men, Colonel Nickolls of the Marines, who conducted the embassy, was well acquainted, having been previously appointed Generalissimo of all their forces; and they therefore extended to us the right hand of friendship, and conducted us into the largest hut in the town.

The rest of the warriors were by this time roused from their lethargy, and soon began to crowd about us; so that in a few minutes the hut was filled with upwards of an hundred savages, each holding in his hand the fatal tomahawk, and having his scalping knife suspended from a belt fastened round his middle. The scene was now truly singular. There is a solemnity about the manner of an Indian chief extremely imposing; and this, joined with the motions which were meant to express welcome, compelled me, almost in spite of myself, to regard these half-naked wretches with veneration.

With the form, complexion, and costume of an American Indian, most Englishmen are well acquainted. In stature, they hardly come up to the common height of an European, and in appearance of robustness they are greatly inferior, being generally spare and slender in their make. Nor, indeed, do they at all equal the natives of Europe in strength. Their agility is superior to ours, but in muscular power they fall much short of us. Their complexion is a dark red, resembling brick dust rather than copper; their hair is universally long, coarse, and black; they have little or no beard, and the body is entirely smooth. Their features are high, and might perhaps be regular, were nature left to herself; but they are usually twisted and distorted into the most frightful shapes, with the view of adding to the ferocity of their looks. Their dress is of the simplest kind, consisting partly of the skins of wild beasts, and party of a scarf, made of cotton cloth. For their legs and feet they have no covering, and instead of a cap, they wear their own hair twined into a knot, and ornamented with various coloured feathers. Besides the tomahawk and scalping knife, each man is armed with a rifle or firelock, in the use of which they are exceedingly dexterous.

The women, again, are as much the reverse of beautiful as it is easy to conceive. Being forced by their husbands to undergo the greatest fatigues, and to perform the most menial offices, their air has in it nothing of the commanding dignity which characterizes that of the men. On the contrary, they are timid and servile, never approaching the other sex without humble prostrations; while their shape is spoiled by hard labour, and their features disfigured with ornaments. Whenever the tribe marches, they are loaded with the children, and all culinary utensils, the haughty warrior condescending to carry nothing except his arms; and as soon as it halts, they are condemned to toil for the benefit of the men, who throw themselves upon the ground, and doze till their meal is prepared.

But I must not attempt to describe the manners and customs of this strange people, which have been so frequently and so much better described already. I would rather relate such incidents as fell under my own immediate observation, without suffering; my simple narrative to aim at a dignity to which it is not entitled.

Having brought with us an interpreter, we were informed by him that the king declined entering upon business till after the feast. This was speedily prepared, and laid out upon the grass, consisting of lumps of Buffalo flesh, barely warmed through, and swimming in blood; with cakes of Indian corn and manioc. Of dishes and plates, there were none. The meat was brought in the hand of the females who had dressed it, and placed upon the turf; the warriors cut slices from it with their knives; and holding the flesh in one hand, and the cake in the other, they eat, as I thought rather sparingly, and in profound silence. Besides these more substantial viands, there were likewise some minced-meats of an extraordinary appearance, served up upon dried hides. Of these the company seemed to be particularly fond, dipping their hands into them without ceremony, and thus conveying the food to their mouths; but for my own part, I found it sufficiently difficult to partake of the raw flesh, and could not overcome my loathing so much as to taste the mince.

When the remnant of the food was removed, an abundant supply of rum, which these people had received from our fleet, was produced. Of this they swallowed large potations; and, as the spirit took effect, their taciturnity gave way before it; till at last, speaking all together, each endeavoured, by elevating his voice, to drown the voices of his companions, and a tremendous shouting was the consequence. Springing from the ground, where hitherto they had sat cross-legged, many of them likewise began to jump about, and exhibit feats of activity; nor was I without apprehension that this riotous banquet would end in bloodshed. The king and chief warrior alone still retained their senses sufficiently unclouded to understand what was said. From them, therefore, we obtained a promise, that the tribe would afford to the expedition. Every assistance in their power; after which wc retired for the night to a hut assigned for our ac commodation, leaving our wild hosts to continue the revel as long as a single drop of spirits remained.

On the following morning, having presented the warriors with muskets and ammunition, we departed, taking with us the two chiefs at their own request. For this journey they had equipped themselves in a most extraordinary manner; making their appearance in scarlet jackets, which they had obtained from Colonel Nickolls. old fashioned steel-bound cocked hats, and shoes. Trowsers they would not wear, but permitted their lower parts to remain with no other covering than a girdle tied round their loins; and sticking scalping knives in their belts, and holding tomahawks in their hands, they accompanied us to the fleet, and took up their residence with the Admiral.

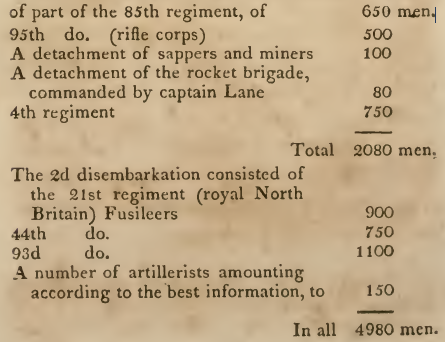

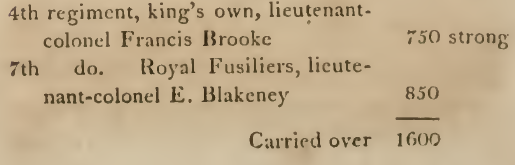

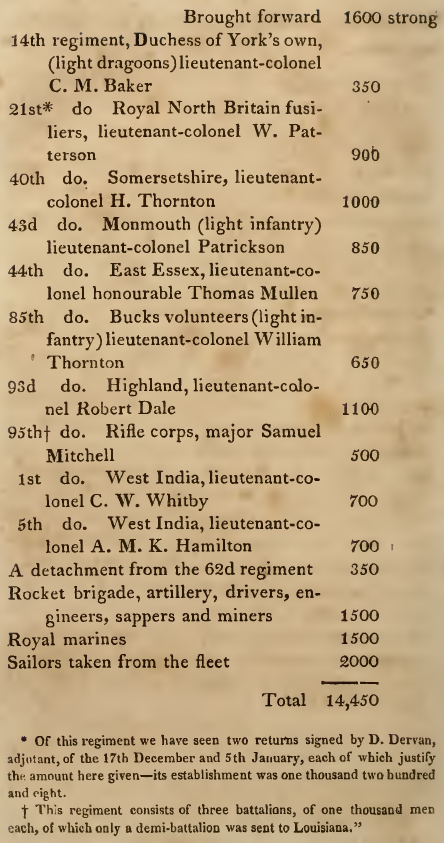

In the mean time, the disembarkation was going on with much spirit. The cutters being taken, and all difficulties removed, the troops began, on the 16th, to quit the ships, and onthe 21st, were assembled in force upon Pine Island. But before they could cross over to the main, it was necessary that some arrangements should be made, and that the different battalions should be divided into corps and brigades. With this design, General Keane reviewed his army on the 22d, and distributed it into the following order.

Instead of a light brigade, he determined to form three battalions into an advanced guard. The regiments appointed to this service, were the 4th, 85th, and 95th; and as an officer of courage and enterprising talent is required to lead the advance of an army, they were put under the command of Colonel Thornton. Attached to this corps of infantry, were a party of rocket-men, and two light three-pounder guns; a species of artillery convenient enough, where celerity of movement is alone regarded, but of very little service in the field. The rest of the troops were arranged as before into two brigades. The first, composed of the 21st, 44th, and one black regiment, was intrusted to Colonel Brook; and the second, containing the 93d, and the other black corps, to Colonel Hamilton, of the 7th West India regiment. To each of these, a certain proportion of artillery and rockets was allotted; while the dragoons, who had brought their harness and other appointments on shore, remained as a sort of body-guard to the General, till they should provide themselves with horses.

The adjustment of these matters having occupied a considerable part of the 22d, it was determined that all things should remain as they were till next morning. Boats, in the mean time, began to assemble from all quarters, supplies of ammunition were packed, so as to prevent the possibility of damage from moisture, and stores of various descriptions were got ready. But it appeared, that even now, many serious inconveniences must be endured, and obstacles surmounted, before the troops could reach the scene of action. In the first place, from Pine Island to that part of the main towards which prudence directed us to steer, was a distance of no less than 80 miles. This, of itself, was an obstacle, or at least an inconvenience of no slight nature, for should the weather prove boisterous, open boats heavily laden with soldiers, would stand little chance of escaping destruction. in the course of so long a voyage. In the next place, and what was of infinitely greater importance, it was found that there were not throughout the whole fleet, a sufficient number of boats to transport above one-third of the army at a time. But to land in divisions, would expose our forces to be attacked in detail, by which means, one party might be cut to pieces before the others could arrive to its support. The undertaking was, therefore, on the whole, extremely dangerous, and such as would have been probably abandoned by more timid leaders. Ours, however, were not so to be alarmed. They had entered upon a hazardous business, in whatever way it should be prosecuted; and since they could not work miracles, they resolved to lose no time in bringing their army into the field, in the best manner which circumstances would permit.

With this view, the advance, consisting of 1,600 men, and two pieces of cannon, was next morning embarked. I have already stated that there is a small creek, called the Bayou de Catiline, which runs up from Lake Pontchartrain through the middle of an extensive morass, about ten miles below New Orleans. Towards this creek were the boats directed, and here it was resolved to effect a landing. When we set sail, the sky was dark and lowering, and before long, a heavy rain began to fall. Continuing without intermission during the whole of the day, towards night it as usual ceased, and was succeeded by a sharp frost; which taking effect upon men thoroughly exposed, and already cramped by remaining so long in one posture, rendered our limbs completely powerless. Nor was there any means of dispelling the benumbing sensation, or effectually resisting the cold. Fires of charcoal, indeed, were lighted in the sterns of the boats, and were suffered to burn as long as day-light lasted; but as soon as it grew dark, they were of necessity extinguished, lest the flame should be seen by row-boats from the shore, and an alarm be thus communicated. Our situation was, therefore, the reverse of comfortable; since even sleep was denied us, from the apprehension of fatal consequences.

Having remained in this uncomfortable state till midnight, the boats cast anchor, and hoisted awnings. There was a small piquet of the enemy stationed at the entrance of the creek, by which we meant to effect our landing. This it was absolutely necessary to surprise; and while the rest lay at anchor, two or three fast sailing barges were sent on to execute the service. Nor did they experience much difficulty in accomplishing their object. Nothing, as it appeared, was less dreamt of by the Americans than an attack from this quarter, consequently, no persons could be less on their guard than the party here stationed. The officer who conducted the force sent against them, found not so much as a single sentinel posted; but having landed his men at two places, above and below the hut which they inhabited, extended his ranks so as to’ surround it, and closing gradually in, took them all fast asleep, without noise or resistance.

When such time had been allowed as was deemed sufficient for the accomplishment of this undertaking, the flotilla again weighed anchor, and without waiting for intelligence of success, pursued their voyage. Hitherto we had been hurried along at a rapid rate by a fair breeze, which enabled us to carry canvas; but this now left us, and we made way only with rowing. Our progress was, therefore, considerably retarded, and the risk of discovery heightened by the noise which that labour necessarily occasions; but in spite of all this, we reached the entrance of the creek by dawn; and about nine o’clock, were safely on shore.

The place where we landed was as wild as it is possible to imagine. Wherever we looked, nothing was to be seen except one huge marsh, covered with tall reeds; not a house, nor a vestige of human industry could be discovered; and even of trees, there were but a few growing upon the banks of the creek. Yet it was such a spot as, above all others, favoured our operations. No eye would watch us, or report our arrival to the American General. By remaining quietly among the reeds, we might effectually conceal ourselves from notice; because, from the appearance of all around, it was easy to perceive that the place which we occupied was seldom, if ever before marked with a human footstep. Concealment, however, was the thing of all others which we required, for be it remembered, that there were now only sixteen hundred men on the main land. The rest were still at Pine Island, where they must remain till the boats which had transported us should return for their conveyance, consequently many hours must elapse before this small corps could be either reinforced or supported. If, therefore, we had sought for a point where a descent might be made, in secrecy and safety, we could not have found one better calculated for mat purpose than the present; because it afforded every means of concealment to one part of our force, until the others should be able to come up.

It was, therefore, confidently expected, that no movement would be made previous to the arrival of the other brigades; but, in our expectations of quiet, we were deceived. The deserters who had come in, and accompanied us as guides, assured the General that he had only to show himself, when the whole district would submit. They repeated, that there were not five thousand men in arms throughout the state; that of these, not more than twelve hundred were regular soldiers, and that the whole was at present several miles on the opposite side of the town, expecting an attack on that quarter, and apprehending no danger on this. These arguments, together with the nature of the ground on which we stood, so ill calculated for a proper distribution of troops, in case of attack, and so well calculated to hide the movements of a force acquainted with all the passes and tracks which, for aught we knew, intersected the morass, induced our leader to push forward at once into the open country. As soon, therefore, as the advance was formed, and the boats had departed, we began our march, following an indistinct path along the edge of a ditch or canal. It was not, however, without many checks that we were able to proceed. Other ditches, similar to that whose course we pursued, frequently stopped us by running in a cross direction, and falling into it at right angles. These were too wide to be leaped, and too deep to be forded; consequently, on all such occasions, the troops were obliged to halt, while bridges were hastily constructed of what materials could be procured, and thrown across.

Having advanced in this manner for several hours, we, at length, found ourselves approaching a more cultivated region. The marsh became gradually less and less continued, being intercepted by wider spots of firm ground; and the reeds gave place, by degrees, to wood; and the wood to inclosed fields. Upon these, however, nothing grew, harvest having long ago ended. They presented, therefore, but a melancholy appearance, being covered with the stubble of sugar-cane, which resembled the reeds we had just quitted, in every thing except altitude. Nor as yet was any house or cottage to be seen. Though we knew, therefore, that human habitations could not be far off, it was impossible to guess where they lay, or how numerous they might prove; and as we could not tell whether our guides might not be deceiving us, and whether ambuscades might not be laid for our destruction, as soon as we should arrive where troops could conveniently act, our march was now conducted with more caution and regularity.

But in a little while, some groves of orange trees presented themselves; on passing which, two or three farm-houses appeared. Towards these, our advanced companies immediately hastened, with the hope of surprising the inhabitants, and preventing any alarm from being raised. Hurrying on at double quick time, they surrounded the buildings, succeeded in securing the inmates, and capturing several horses; but becoming rather careless in watching their prisoners, one man contrived to effect his escape; after which, nil hope of eluding observation was laid aside. The rumour of our landing would, we knew, spread faster than we could march; and it now only remained to make that rumour as terrible as possible.

With this view, the column was ordered to widen its files, and to present as formidable an appearance as could be assumed. Changing our order, therefore, we marched, not in sections of eight or ten abreast, but in pairs, and thus contrived to cover with our small division as large a track of ground, as if we had mustered thrice our present numbers. Our steps were likewise quickened, that we might gain, if possible, some advantageous position, where we might be able to cope with any force that might attack us; and thus hastening on, we soon arrived at the main road, which leads directly to New Orleans. Turning to the right, we then advanced in the direction of that town for about a mile; when having reached a spot where it was considered that we might encamp in comparative safety, our little column halted; the men piled their arms, and a regular bivouac was formed.

The country where we had now established ourselves, answered, in every respect, the description I have already given of the neck of land on which New Orleans is built. It was a narrow plain of about a mile in width, bounded on one side by the Mississippi, and on the other by the marsh from which we had just emerged. Towards the open ground, this marsh was covered with dwarf-wood, having; the semblance of a forest rather than of a swamp; but on trying the bottom, it was found that both characters were united, and that it was impossible for a man to make his way among the trees, so boggy was the soil upon which they grew. In no other quarter, however, was there a single hedge-row, or plantation of any kind; excepting a few apple and other fruits trees in the gardens of such houses as were scattered over the plain, the whole being laid out in large fields for the growth of sugar-cane; a plant which seems as abundant in this part of the world as in Jamaica.

Looking up towards the town, which we at this time faced, the marsh is upon your right, and the river upon your left. Close to the latter runs the main road, following the course of the stream all the way to New Orleans. Between the road and the water, is thrown up a lofty and strong embankment, resembling the dykes in Holland, and meant to serve a similar purpose; by means of which, the Mississippi is prevented from overflowing its banks, and the entire flat is preserved from inundation. But the attention of a stranger is irresistibly drawn away from every other object, to contemplate the magnificence of this noble river. Pouring along at the prodigious rate of four miles an hour, an immense body of water is spread out before you; measuring a full mile across, and nearly a hundred fathoms in depth. What this mighty stream must be near its mouth, I can hardly imagine, for we were here upwards of a hundred miles from the ocean.

Such was the general aspect of the country which we had entered; our own position, again, was this. The three regiments turning off from the road into one extensive green field, formed three close columns within pistol-shot of the river. Upon our right, but so much in advance as to be of no service to us, was a large house, surrounded by about twenty wooden huts, probably intended for the accommodation of slaves. Towards this house, there was a slight rise in the ground, and between it and the camp was a small pond of no great depth. As far to the rear again as the first was to the front, stood another house, inferior in point of appearance, and skirted by no out-buildings : this was also upon the right; and here General Keane, who accompanied us, fixed his head-quarters; but neither the one nor the other could be employed as a covering redoubt, the flank of the division extending, as it were, between them. Immediately in front, where the advanced posts were stationed, ran a dry ditch and a row of lofty palings; and thus, both it and the left were in some degree protected; while the right and rear were wholly without cover. Though we occupied this field, therefore, and might have looked well in a peaceable district, it must be confessed that our situation hardly deserved the title of a military position.

LETTER XX.

NOON had just passed, when the word was given to halt, and therefore every opportunity was afforded of posting the piquets with leisure and attention. Nor was this deemed enough to secure tranquillity; several parties were sent out in all directions to reconnoitre, who returned with an account that no enemy nor any trace of an enemy could be discerned. The troops were accordingly suffered to light fires, and to make themselves comfortable; only their accoutrements were not taken off, and the arms were piled in such form as to be within reach at a moment’s notice.

As soon as these agreeable orders were issued, the soldiers proceeded to obey them both in letter and in spirit. Tearing up a number of strong palings, large fires were lighted in a moment; water was brought from the river, and provisions were cooked. But their bare rations did not content them. Spreading themselves over the country as far as a regard to safety would permit, they entered every house, and brought away quantities of hams, fowls, and wines of various descriptions: which being divided among them, all fared well and none received too large a quantity. In this division of good things, they were not unmindful of their officers; for upon active warfare the officers are considered by the privates as comrades, to whom respect and obedience are due, rather than as masters.

It was now about three o’clock in the afternoon, and all had as yet remained quiet. The troops having finished their meal, lay stretched beside their fires, or refreshed themselevs by bathing, for today the heat was such as to render this latter employment extremely agreeable, when suddenly a bugle from the advanced posts sounded the alarm, which was echoed back from all in the army. Starting up, we stood to our arms, and prepared for battle, the alarm being now succeeded by some firing; but we were scarcely in order, when word was sent from the front that there was no danger, only a few horse having made their appearance, who were checked and put to flight at the first discharge. Upon this intelligence, our wonted confidence returned, and we again betook ourselves to our former occupations, remarking that, as the Americans had never yet dared to attack, there was no great probability of their doing so on the present occasion.

In this manner the day passed without any farther alarm; and darkness having set in, the fires were made to blaze with increased splendour, our evening meal was eat, and we prepared to sleep. But about half-past seven o’clock, the attention of several individuals was drawn to a large vessel, which seemed to be stealing up the river till she came opposite to our camp; when her anchor was dropped, and her sails leisurely furled. At first we were doubtful whether she might not be one of our own cruisers which had passed the fort unobserved, and had arrived to render her assistance in our future operations. To satisfy this doubt, she was repeatedly hailed, but returned no answer; when an alarm spreading through the bivouac, all thought of sleep was laid aside. Several musket shots were now fired at her with the design of exacting a reply, of which no notice was taken; till at length having fastened all her sails, and swung her broadside towards us, we could distinctly hear some one cry out in a commanding voice, ‘Give them this for the honour of America.’ The words were instantly followed by the flashes of her guns, and a deadly shower of grape swept down numbers in the camp.

Against this dreadful fire we had nothing whatever to oppose. The artillery which we had landed was too light to bring into competition with an adversary so powerful; and as she had anchored within a short distance of the opposite bank, no musketry could reach her with any precision or effect. A few rockets were discharged, which made a beautiful appearance in the air; but the rocket is an uncertain weapon, and these deviated too far from their object to produce even terror among those against whom they were directed. Under these circumstances, as nothing could be done offensively, our sole object was to shelter the men as much as possible from this iron hail. With this view, they were commanded to leave the fires, and to hasten under the dyke. Thither all, accordingly, repaired, without much regard to order and regularity, and laying ourselves along wherever we could find room, we listened in painful silence to the pattering of grape shot among our huts, and to the shrieks and groans of those who lay wounded beside them.

The night was now as dark as pitch, the moon being but young, and totally obscured with clouds. Our fires deserted by us, and beat about by the enemy’s shot, began to burn red and dull, and, except when the flashes of those guns which played upon us cast a momentary glare, not an object could be distinguished at the distance of a yard. In this state we lay for nearly, an hour, unable to move from our ground, or offer any opposition to those who kept us there; when a straggling ire of musketry called our attention towards the piquets, and warned us to prepare for a closer and more desperate strife. As yet, however, it was uncertain from what cause this dropping fire arose. It might proceed from the sentinels, who, alarmed by the cannonade from the river, mistook every tree for an American; and till this should be more fully ascertained, it would be improper to expose the troops, by moving any of them from the shelter which the bank afforded. But these doubts were not permitted to continue long in existence. The dropping fire having paused for a few moments, was succeeded by a fearful yell; and the heavens were illuminated on all sides by a semi-circular blaze of musketry. It was now clear that we were surrounded, and that by a very superior force; and, therefore, no alternative remaining, but, either to surrender at discretion, or to beat back the assailants.

The first of these plans was never for an instant thought of; and the second was immediately put into force. Rushing from under the bank, the 85th and 95th flew to support the piquets, while the 4th, stealing to the rear of the encampment, formed close column, and remained as a reserve. But to describe this action is altogether out of the question, for it was such a battle as the annals of modern warfare can hardly match. All order, all discipline, were lost. Each officer, as he was able to collect twenty or thirty men round him, advanced into the middle of the enemy, when it was fought hand to hand, bayonet to bayonet, and sword to sword, with the tumult and ferocity of one of Homer”s combats.

To give some idea of this extraordinary combat, I shall detail the adventures of a friend of mine, who chanced to accompany one of the first parties sent out. Dashing through the bivouac under an heavy discharge from the vessel, his party reached the lake, which was forded, and advanced as far as the house where General Keane had fixed his head quarters. The moon hail by this time made her way through the clouds; and though only in her first quarter gave light enough to permit their seeing, though not distinctly. Having now gone far enough to the right, the party pushed on towards the front, and entered a sloping field of stubble; at die upper end of which they could distinguish a dark line of men; but, whether they were friends or foes it was impossible to determine. Unwilling to fire, lest he should kill any of our own people, my friend led on the volunteers whom he had got round him, till they reached some thick piles of reeds, about twenty yards from the object of their notice. Here they were saluted by a sharp volley, and being now confident that they were enemies, he commanded his men to fire. But a brother officer who accompanied him, was not so convinced, assuring him that they were soldiers of the 95th, upon which they agreed to divide the forces; that he who doubted, should remain with one part, where he was, while my friend, with the rest, should go round upon the flank of this line, and discover certainly to which army it belonged.

Taking with him about fourteen men, he accordingly moved off to the right, when falling in with some other stragglers, he attached them likewise to his party, and advanced. Springing over a high rail, they came down upon the left of those concerning whom the doubt had existed, and found them to be, as my friend had supposed, Americans. Not a moment was lost in attacking, but having got unperceived, within a few feet of where they stood, they discharged their pieces, and rushed on to the charge. In the whole course of my military career, I do not recollect any scene at all resembling that which followed. Some soldiers having lost their bayonets, laid about them with the butt end of their firelocks; while many a sword, which till to night had not drank blood, became in a few minutes crimsoned enough.

The contest, though desperate, was of short duration. Panic struck at the vigour of the assault, the Americans soon fled, and our people pursued them through a garden, and into the middle of the huts, which I have stated as surrounding a large house upon the right front of our original position. Here they found a considerable number of our own men, and one or two officers taken, and guarded by a detachment of Americans. These they immediately released, who, catching up what weapons they could find, followed their liberators in the chase of the flying enemy.

But, having now got as far in advance of the main body as he considered prudent, my friend determined to pause here, till he should discover how things went in other parts of the field.

With this view he halted his party, amounting, by the late addition, to forty men and two officers; and proceeding alone towards the front, he descried another line, of the length of one strong battalion, at the bottom of a field on the left. Being anxious to discover who they were, he walked forward, when a voice from among them called out not to fire, because they were Americans. But my friend had more in view than merely to discover what countrymen they were, and therefore, answering as one of themselves, he demanded to what corps they belonged. To this the speaker replied, that they were the 2d battalion of the 1st Regiment, and requested to be informed what had become of the 1st battalion. Still imitating the American twang, my friend again made answer that it was upon his right; and assuming a tone of authority, commanded them to remain as they were, till he should join them with a party of which he was at the head.

Having ended this conversation, he returned to the village, and forming his party in line, lad them on in deep silence towards the 2d battalion of the 1st Regiment. As they drew near he called out for the commanding officer, or him who had spoken, to come forward, adding that he had something to communicate; upon which an elderly man, armed with a huge dragoon sabre, advanced to meet him. As soon as they were together, my friend seized his sword, and desired him to surrender, declaring that he and his regiment were surrounded, and that resistance would only occasion unnecessary blood, shed. The man was completely confounded, and resigned his sword immediately; when, turning to another officer he demanded his. This person, however, was younger, and appeared to have his wits more about him, for instead of giving up his weapon, he made a cut at my friend’s head, which he had scarcely time to ward of. Their countrymen, likewise, who had hitherto stood motionless, took courage at the deed, and began firing; when, as all chance of cheating them into a surrender was at an end, our soldiers dashed amongst them, and once more renewed the combat hand in hand.

But though the enemy had so far recovered from their panic as to refuse a surrender, their resolution did not prompt them to any determined resistance. Charged as they were upon the flank, it is not wonderful that they soon fell into confusion, and being closely pressed by the brave little party, they had no time given to rally. In less than an hour, therefore, they began to fly; and as my friend considered that he had been rash enough in attacking a force so superior, with a handful of men, he did not add to that rashness, by continuing the pursuit too far; but having chased them a little way, recalled his followers, and returned to the hamlet.

In giving a detail so minute of the adventures of an individual, on the present occasion, I am far from wishing to exhibit him in the light of an hero of romance. The fact is, that what he did, was done in a greater or less degree by every officer in the army; for this was a combat which compelled every man, in spite of himself, to rely solely on his own resources. Attacked unexpectedly, and in the dark, surrounded by enemies before any arrangements could be made to oppose them, it is not conceivable that order, or the rules of disciplined war could be preserved. We were mingled with the Americans, frequently before we could tell whether they were friends or foes; because speaking the same language with ourselves, there was no mark by which to distinguish them, at least none whose influence extended beyond the distance of a few paces. The consequence was, that more feats of individual gallantry were performed in the course of this night, than many campaigns might have afforded an opporrunity of performing; while viewing the affair as a regular action, none can be imagined more full of blunders and confusion. No man could tell what was going forward in any quarter, except where he himself chanced immediately to stand; no one part of the line could bring assistance to another, because, in truth, no line existed. It was in one word a perfect tumult, resembling, except in its fatal consequences, those scenes which the night of an Irish fair usually exhibits, much more than an engagement between two civilised armies.

The night was far spent, and the sound of fighting had begun to die away, when my friend once more established himself among the huts. Here, likewise, considerable numbers of our people assembled, from whom he learned that the enemy were repulsed on all sides. The combat had been long and obstinately contested, having begun at eight in the evening, and continuing till three in the morning, but the victory was decidedly ours; for the Americans retreated in the greatest disorder, leaving us in possession of the field. Our loss, however, was enormous. Not less than 500 men had fallen, many of whom were our finest soldiers and best officers, and yet we could not but consider ourselves fortunate in escaping from the toils, even at the expense of so great a sacrifice.

The recal being sounded, our troops were soon brought together, and filing to the left, formed line in front of the ground, where we had at first encamped. Here we remained ready for whatever might occur till morn, when, to avoid the fire of the vessel, we again betook ourselves to the bank, and lay down. For some hours past, indeed, she had ceased to annoy us, but this we knew was owing merely to the ignorance of her crew, where to direct her aim; and we were well aware that, unless we contrived to cover ourselves before that ignorance was removed, we should undoubtedly suffer for our temerity.

Day light was beginning to appear, and we were just able to distinguish that our enemy was a line schooner, pierced for eighteen guns, and crowded with men, when we retreated to the bank. Here we lay for some hours worn out with fatigue and want of sleep, and shivering in the cold air of a frosty morning, without being able to light a fire, or prepare a morsel of provisions. Whenever an attempt of the kind was made; as soon as two or three men began to steal from shelter, the schooner’s guns immediately opened; and thus was the whole division kept, as it were, prisoners, for the space of an entire day.

While our troops lay in this uncomfortable situation, I stole away with two or three men to find out and bury a friend who was among the slain. In wandering over the field for this purpose, the most shocking and disgusting sights every where presented themselves. I have frequently beheld a greater number of dead bodies in as small a compass, though these, indeed, were numerous enough, but wounds more disfiguring or more horrible, I certainly never witnessed. A man, shot through the head or heart, lies as if he were in a deep slumber; in so much, that when you gaze upon him, you experience little else than pity. But of these many had met their death from bayonet wounds, sabre cuts, or heavy blows from the butt ends of muskets; and the consequence was, that not only were the wounds themselves exceedingly frightful, but the very countenances of the dead exhibited the most savage and ghastly expressions. Friends and foes lay together in small groups of four or six, nor was it difficult to tell almost the very hand by which some of them had fallen. Nay, such had been the deadly closeness of the strife, that in one or two places, an English and American soldier might be seen with the bayonet of each fastened in the others body.

Having searched for some time in vain, I at length discovered my friend lying behind a bundle of reeds, where, during the action, we had separated; and shot through the temples by a rifle bullet so remarkably small, as scarcely to leave any trace of its progress. I am well aware that this is no fit place to introduce the working of my own personal feelings, but he was my friend, and such a friend as few men are happy enough to possess. We had known and loved each other for years; our regard had been cemented by a long participation in the same hardships and dangers; and it cannot therefore surprise, if even now I pay that tribute to his worth and our friendship, which, however unavailing it may be, they botli deserve.

When in the act of looking for him, 1 had flattered myself, that I should be able to bear his loss with something like philosophy, but when I beheld him pale and bloody, I found all my resolution evaporate. I threw myself on the ground beside him, and wept like a child. But this was no time for the indulgence of useless sorrow. Like the royal bard, I knew that I should go to him, but he could not return to me, and I could not tell whether an hour would pass before my summons would arrive Lifting him, therefore, upon a cart, I had him carried down to head-quarter house, now converted into an hospital, and having dug for him a grave at the bottom of the garden, I laid him there as a soldier should be laid, arrayed, not in a shroud, but in his uniform. Even the very privates, whom I brought with me to assist at his funeral, mingled their tears with mine, nor are many so fortunate as to return to the parent dust more deeply or more sincerely lamented.

Retiring from the performance of this melancholy duty, I strolled into the hospital, and visited the wounded. It is here that war loses its grandeur and show, and presents only a real picture of its effects. Every room in the house was crowded with wretches mangled, and apparently in the most excruciating agonies. Prayers, groans, and I grieve to add, the most horrid exclamations, smote upon the ear wherever I turned. Some lay at length upon straw, with eyes half closed, and limbs motionless; some endeavoured to start up, shrieking with pain; while the wandering eye and incoherent speech of others, indicated the loss of reason, and usually foretold the approach of death. But there was one among the rest, whose appearance was too horrible ever to be forgotten. He had been shot through the wind-pipe, and the breath making its way between the skin and the flesh, had dilated him to a size absolutely terrific. His head and face were particularly shocking. Every feature was enlarged beyond what can well be imagined; while his eyes were so completely hidden by the cheeks and forehead, as to destroy all resemblance to an human countenance.

Passing through the apartments where the private soldiers lay, I next came to those occupied by officers. Of these there were five or six in one small room, to whom little better accommodation could be provided than to their inferiors. It was a sight peculiarly distressing, because all of them chanced to be personal acquaintances of my own. One had been shot in the head, and lay gasping and insensible; another had received a musket ball in the belly, which had pierced through and lodged in the back bone. The former appeared to suffer but little, giving no signs of life, except what an heavy breathing produced; the latter was in the most dreadful agony, screaming out, and gnawing the covering under which he lay. There were many besides these, some severely, and others slightly hurt; but as I have already dwelt at sufficient length upon a painful subject, I shall only observe, that to all was afforded every assistance which circumstances would allow; and that the exertions of their medical attendants were such, as deserved and obtained the grateful thanks of even the most afflicted among the sufferers themselves.

LETTER XXI.

IN the mean time the rest of the troops were landing as fast as possible, and hastening to join their comrades. Though the advance had set out from Pine Island by themselves, they did not occupy all the boats in the fleet. Part of the second brigade, therefore, had embarked about twelve hours after their departure; and rowing leisurely on, were considerably more than half way across the lakes when the action began. In the stillness of night, however, it is astonishing at what distance a noise is heard. Though they must have been at least twenty miles from the Bayou when the schooner first opened, the sound of firing reached them, and roused the rowers from their indolence. Pulling with all their might, they now hurried on, while the most profound silence reigned among the troops, and gaining the creek in little more than three hours, sent fresh reinforcements to share in the danger and glory of the night.

Nor was a moment lost by the sailors in returning to the island. Intelligence of the combat spread like wild-fire; the boats were loaded even beyond what was strictly safe, and thus by exerting themselves in a degree almost unparalleled, our gallant seamen succeeded in bringing the whole army into position before dark on the 24th. The second and third brigades, therefore, now took up their ground upon the spot where the late battle was fought, and resting their right upon the woody morass, extended so far towards the river, as that the advance by wheeling up might continue the line across the entire plain.

But instead of taking part in this formation, the advance was still fettered to the bank, from which it was additionally prevented from moving by the arrival of another large ship, which cast anchor about a mile above the schooner. Thus were three battalions kept stationary by the guns of these two formidable floating batteries, and it was clear that no attempt to extricate them could be made without great loss, unless undercover of night. During the whole of the 24th, therefore, they remained in this uncomfortable situation; but as soon as darkness had well set in, a change of position was effected. Withdrawing the troops, company by company, from behind the bank, General Keane stationed them in the village of huts; by which means the high road was abandoned to the protection of a piquet, and the left of the army covered by a large chateau.

Being now placed beyond risk of serious annoyance from the shipping, the whole army remained quiet for the night. How long we were to continue in this state, nobody appeared to know, not a whisper was circulated as to the time of advancing, nor a surmise ventured respecting the next step likely to be taken. In our guides, to whose rumours we had before listened with avidity, no farther confidence was reposed. It was perfectly evident, either that they had purposely deceived us, or that their information was gathered from a most imperfect source; therefore, though they were not exactly placed in confinement, they were strictly watched, and treated more like spies than deserters. Instead of an easy conquest, we had already met with vigorous opposition; instead of finding the inhabitants ready and eager to join us, we found the houses deserted, the cattle and horses driven away, and every appearance of hostility. To march by the only road was rendered impracticable, so completely was it commanded by the shipping. In a word, all things half turned out diametrically opposite to what had been anticipated; and it appeared, that instead of a trifling affair, more likely to fill our pockets, than to add to our renown, we had embarked in an undertaking which presented difficulties not to be surmounted, without patience and determination.

Having effected this change of position, and covered the front of his army with a strong chain of outposts, General Keane, as I have said, remained quiet during the remainder of the night, and on the morrow was relieved from farther care and responsibility by the unexpected arrival of Sir Edward Pakenham, and General Gibbs. As soon as the death of Ross was known in London, the former of these officers was dispatched to take upon himself the command of the army. Sailing immediately with the latter, as his second in command, he had been favoured, during the whole voyage, by a fresh and fair wind, and now arrived in time to see his troops brought into a situation from which all his abilities could scarcely expect to extricate them. Nor were the troops themselves ignorant of the unfavourable circumstances in which they stood. Hoping everything, therefore, from a change, they greeted their new leader with an hearty cheer; while the confidence which past events had tended in some degree to dispel, returned once more to the bosoms of all. It was Christmas Day, and a number of officers clubbing their little stock of provisions, resolved to dine together in memory of former times. But at so melancholy a Christmas dinner I do not recollect at any time, to have been present. We dined in a barn; of plates, knives and forks there was a dismal scarcity, nor could our fare boast of much either in intrinsic good quality, or in the way of cooking. These, however, were mere matters of merriment: it was the want of many well known and beloved faces that gave us pain; nor were any other subjects discussed, besides the amiable qualities of those who no longer formed part of our mess, and never would again form part of it. A few guesses as to the probable success of future attempts alone relieved this topic, and now and then a shot from the schooner drew our attention to ourselves; for though too far removed from the river to be in much danger, we were still within cannon shot of our enemy. Nor was she inactive in her attempts to molest. Elevating her guns to a great degree, she contrived occasionally to strike the wall of the building within which we sat; but the force of the ball was too far spent to penetrate, and could therefore produce no serious alarm.

While we were thus sitting at table, a loud shriek was heard, after one of these explosions, and on running out, we found that a shot had taken effect in the body of an unfortunate soldier. I mention this incident, because I never beheld in any human being so great a tenacity of life. Though fairly cut in two at the lower part of the belly, the poor wretch lived for nearly an hour, gasping for breath, and giving signs even of pain.