Edward King.

The Great South: A Record of Journeys.

THE

GREAT SOUTH:

A RECORD OF JOURNEYS

IN

LOUISIANA, TEXAS, THE INDIAN TERRITORY, MISSOURI, ARKANSAS,

MISSISSIPPI, ALABAMA, GEORGIA, FLORIDA, SOUTH CAROLINA,

NORTH CAROLINA, KENTUCKY, TENNESSEE, VIRGINIA,

WEST VIRGINIA, AND MARYLAND.

BY

EDWARD KING.

PROFUSELY ILLUSTRATED FROM ORIGINAL SKETCHES

BY J WELLS CHAMPNEY.

AMERICAN PUBLISHING COMPANY,

HARTFORD, CONN.

1875.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1874, by

Scribner & Co.

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington, D. C.

CONTENTS.

- Louisiana, Past and Present . . . . . 17

- The French Quarter of New Orleans — The Revolution and its Effects . . . . . 28

- The Carnival — The French Markets . . . . . 38

- The Cotton Trade — The New Orleans Levées . . . . . 50

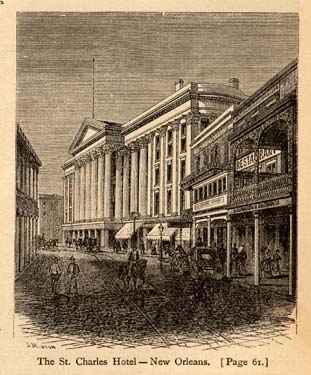

- The Canals and the Lake — The American Quarter . . . . . 59

- On The Mississippi River — The Levée System — Railroads — The Fort St. Philip Canal . . . . . 67

- The Industries of Louisiana — A Sugar Plantation — The Teche Country . . . . . 78

- The Political Situation in Louisiana . . . . . 89

- “Ho! For Texas” — Galveston . . . . . 99

ILLUSTRATIONS

AND MAPS.

- Scene on the Oclawaha River, Florida — Frontispiece

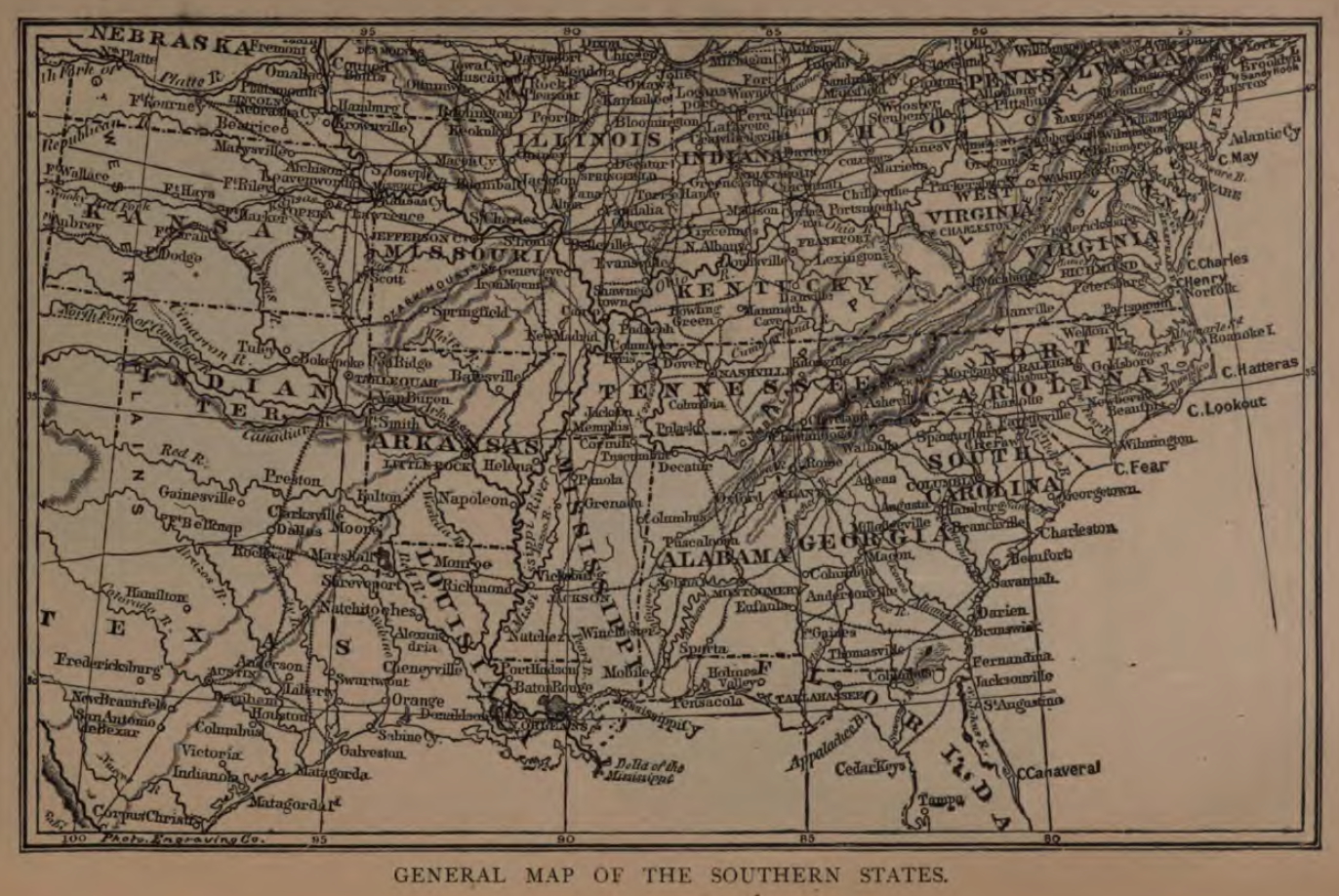

- General Map of the Southern States . . . . . 15

- Bienville, the Founder of New Orleans . . . . . 17

- The Cathedral St. Louis — New Orleans . . . . . 18

- “A blind beggar hears the rustling of her gown, and stretches out his trembling hand for alms,” . . . . . 19

- “A black girl looks wonderingly into the holy-water font” . . . . . 19

- The Archbishop’s Palace, New Orleans . . . . . 20

- “Some aged private dwellings, rapidly decaying,” . . . . . 25

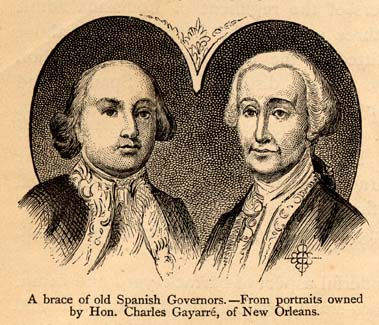

- A brace of old Spanish Governors. — From portraits owned by Hon. Charles Gayarré, of New Orleans . . . . . 26

- “And where to-day stands a fine Equestrian Statue of the Great General” . . . . . 27

- “A lazy negro, recumbent in a cart” . . . . . 29

- “The negro nurses stroll on the sidewalks, chattering in quaint French to the little children” . . . . . 30

- “The interior garden, with its curious shrine” . . . . . 31

- “The new Ursuline Convent, New Orleans . . . . . 32

- “And while they chatter like monkeys, even about politics, they gesticulate violently” . . . . . 35

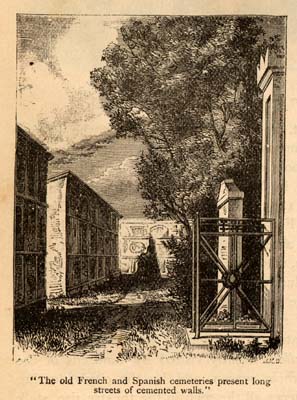

- “The old French and Spanish cemeteries present long streets of cemented walls” . . . . . 36

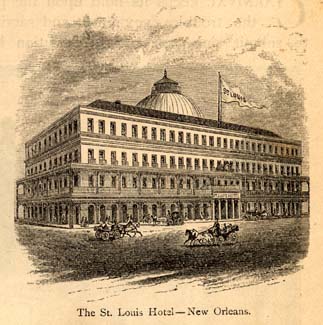

- The St. Louis Hotel, New Orleans . . . . . 37

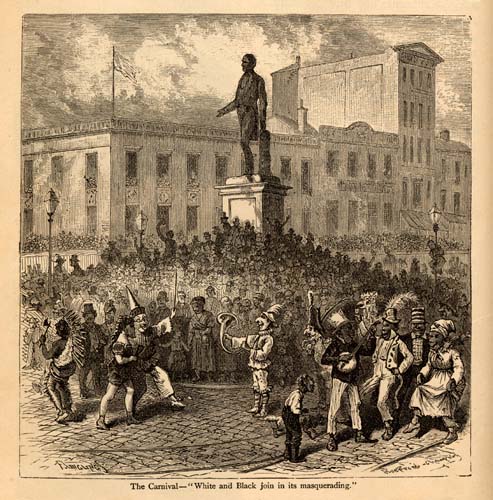

- The Carnival — “White and black join in its masquerading.” . . . . . 38

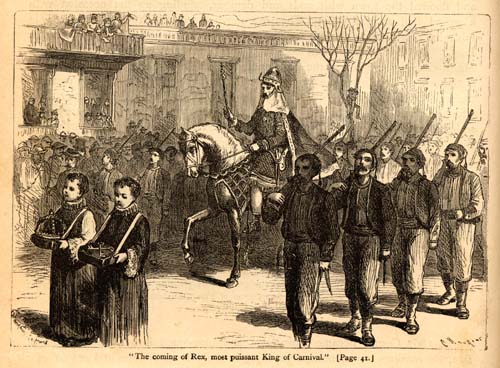

- “The coming of Rex, most puissant King of Carnival” . . . . . 40

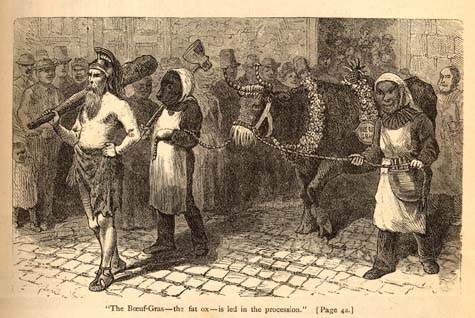

- “The Bœuf-Gras — the fat ox — is led in the procession” . . . . . 41

- “When Rex and his train enter the queer old streets, the balconies are crowded with spectators” . . . . . 42

- “The joyous, grotesque maskers appear upon the ball-room floor” . . . . . 43

- “Many bright eyes are in vain endeavoring to pierce the disguise” . . . . . 45

- “The French market at sunrise on Sunday morning” . . . . . 46

- “Passing under long, hanging rows of bananas and pine-apples” . . . . . 47

- “One sees delicious types in these markets” . . . . . 48

- “In a long passage, between two of the market buildings, sits a silent Louisiana Indian woman” . . . . . 49

- “Stout colored women, with cackling hens dangling from their brawny hands” . . . . . 49

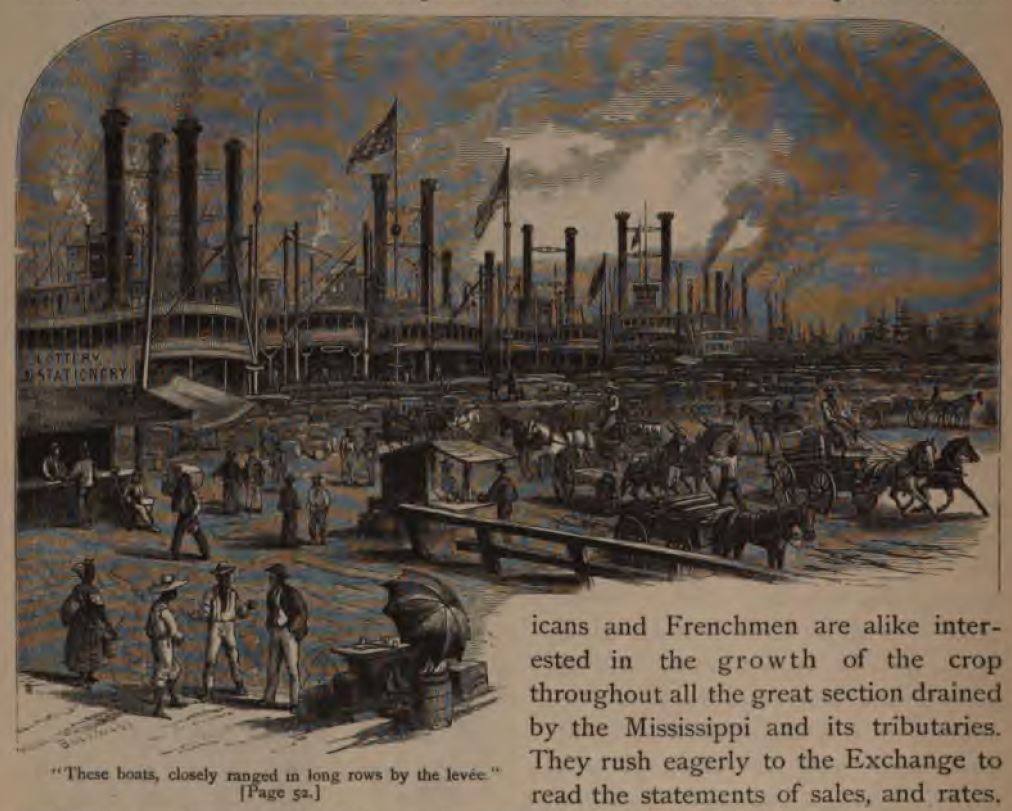

- “These boats, closely ranged in long rows by the levée” . . . . . 50

- “Whenever there is a lull in the work, they sink down on the cotton bales” . . . . . 52

- “Not far from the levée there is a police court, where they especially delight to lounge” . . . . . 52

- “The cotton thieves” . . . . . 55

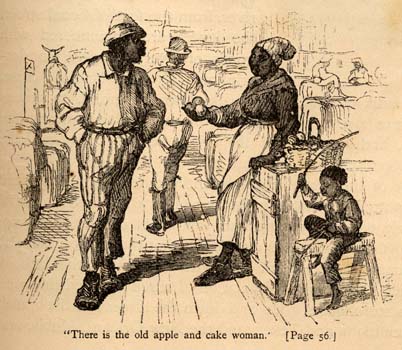

- “There is the old apple and cake woman” . . . . . 55

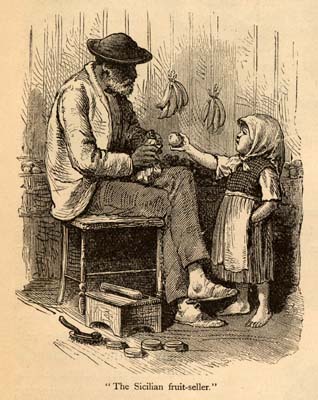

- “The Sicilian fruit-seller” . . . . . 56

- “At high water, the juvenile population perches on the beams of the wharves, and enjoys a little quiet fishing” . . . . . 57

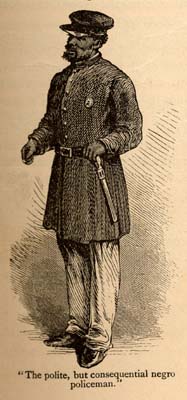

- “The polite but consequential negro policeman,” . . . . . 57

- The St. Charles Hotel, New Orleans . . . . . 59

- The New Basin . . . . . 60

- The old Spanish Fort . . . . . 60

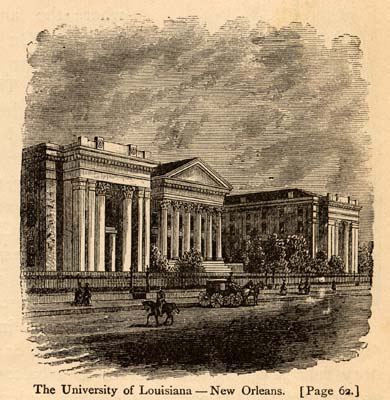

- The University of Louisiana, New Orleans . . . . . 61

- The Theatres of New Orleans . . . . . 61

- Christ Church, New Orleans . . . . . 62

- The Canal street Fountain, New Orleans . . . . . 62

- The Charity Hospital, New Orleans . . . . . 63

- The old Maison de Santé, New Orleans . . . . . 63

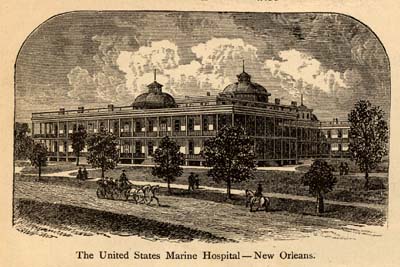

- The United States Marine Hospital, New Orleans . . . . . 64

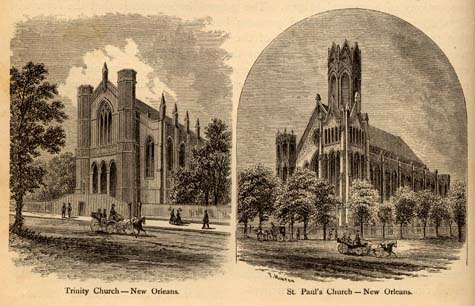

- Trinity Church, New Orleans . . . . . 64

- St. Paul's Church, New Orleans . . . . . 64

- First Presbyterian Church, New Orleans . . . . . 65

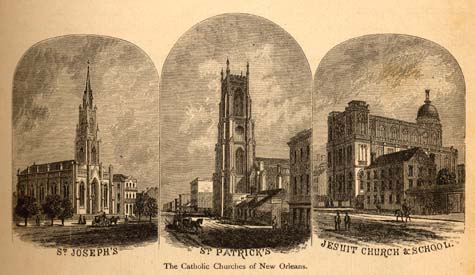

- The Catholic Churches of New Orleans — St. Joseph’s, St. Patrick’s Jesuit Church and School . . . . . 65

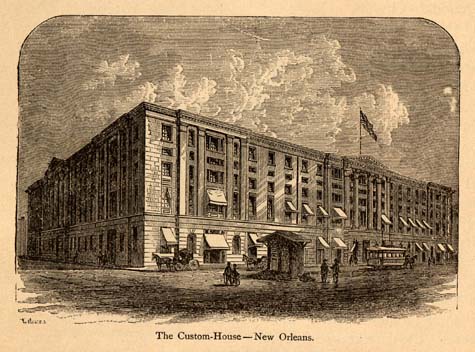

- The Custom-House, New Orleans . . . . . 66

- The United States Branch Mint, New Orleans . . . . . 66

- “Sometimes the boat stops at a coaling station” . . . . . 68

- “The Wasp” . . . . . 69

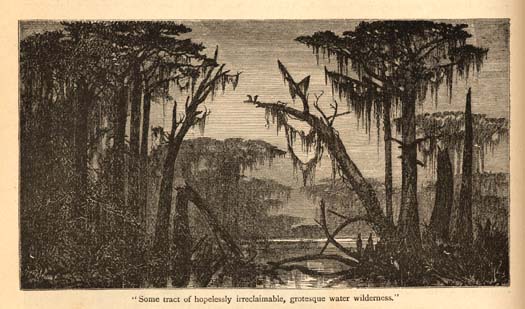

- “Some tract of hopelessly irreclaimable, grotesque water wilderness.” (From a painting by Julio.) . . . . . 70

- The monument on the Chalmette battle-field . . . . . 72

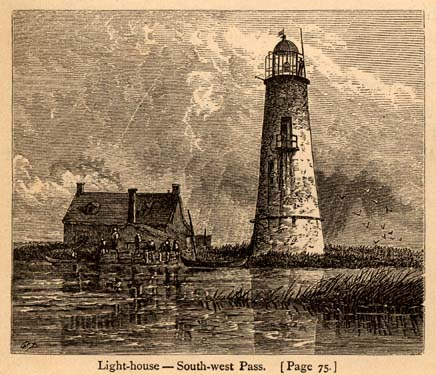

- Light-house, South-west Pass . . . . . 74

- “Pilot Town,” South-west Pass . . . . . 75

- “A Nickel for Daddy” . . . . . 77

- “A cheery Chinaman” . . . . . 82

- Sugar-cane Plantation — “The cane is cut down at its perfection” . . . . . 83

- “The beautiful ‘City Park,’” New Orleans . . . . .87

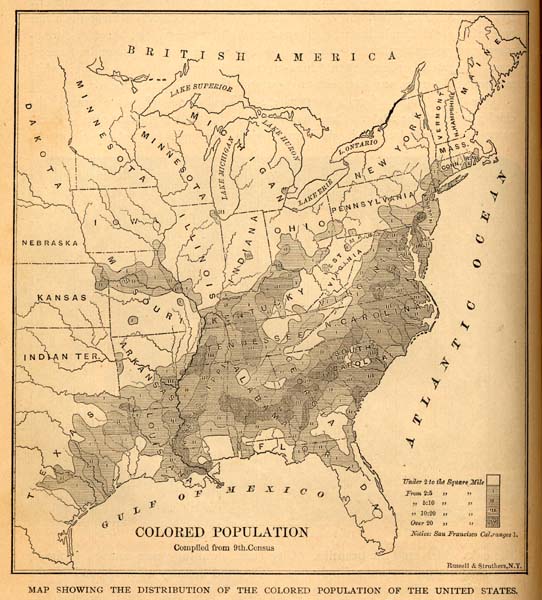

- Map showing the Distribution of the Colored Population of the United States. (From the U. S. Census Reports) . . . . . 88

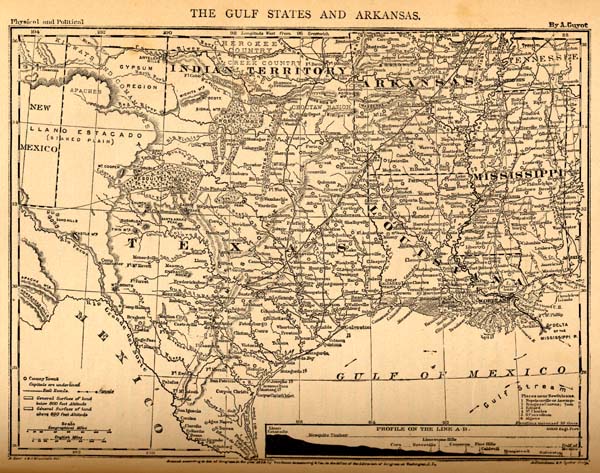

- Map of the Gulf States and Arkansas . . . . . 89

- The Supreme Court, New Orleans . . . . . 92

- The United States Barracks, New Orleans . . . . . 93

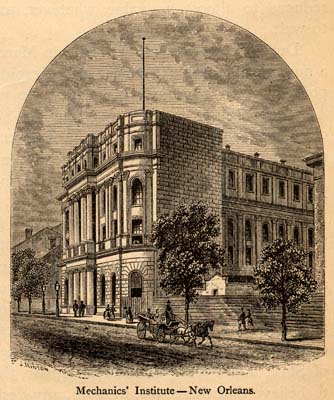

- Mechanics’ Institute, New Orleans . . . . . 95

- Going to Texas . . . . . 99

PREFACE.

THIS book is the record of an extensive tour of observation through the States of the South and South-west during the whole of 1873, and the Spring and Summer of 1874.

The journey was undertaken at the instance of the publishers of Scribner’s Monthly, who desired to present to the public, through the medium of their popular periodical, an account of the material resources, and the present social and political condition, of the people in the Southern States. The author and the artists associated with him in the preparation of the work, traveled more than twenty-five thousand miles; visited nearly every city and town of importance in the South; talked with men of all classes, parties and colors; carefully investigated manufacturing enterprises and sites; studied the course of politics in each State since the advent of reconstruction; explored rivers, and penetrated into mountain regions heretofore rarely visited by Northern men. They were everywhere kindly and generously received by the Southern people; and they have endeavored, by pen and pencil, to give the reading public a truthful picture of life in a section which has, since the close of a devastating war, been overwhelmed by a variety of misfortunes, but upon which the dawn of a better day is breaking.

The fifteen ex-slave States cover an area of more than 880,000 square miles, and are inhabited by fourteen millions of people. The aim of the author has been to tell the truth as exactly and completely as possible in the time and space allotted him, concerning the characteristics of this region and its inhabitants.

The popular favor accorded in this country and Great Britain to the fifteen illustrated articles descriptive of the South which have appeared in Scribner’s Monthly, has led to the preparation of the present volume. Much of the material which has appeared in Scribner will be found in its pages; the whole has, however, been re-written, re-arranged, and, with numerous additions, is now simultaneously offered to the English-speaking public on both sides of the Atlantic.

To the talent and skill of Mr. J. Wells Champney, the artist who accompanied the author during the greater part of the journey, the public is indebted for more than four hundred of the superb sketches of Southern life, character, and scenery which illustrate this volume. The other artists who have contributed have done their work faithfully and well.

New York, November, 1874.

DEDICATION.

TO MR. ROSWELL-SMITH,

Scribner & Co., 654 Broadway, New York.

My Dear Sir: — You have been from first to last so inseparably as well as pleasantly connected with "The Great South” enterprise, that I cannot forbear taking this occasion to thank you, not only for originally suggesting the idea of a journey of observation through the Southern States, but also for having generously submitted to the enlargement of the first plan’s scope, until the undertaking demanded a really immense outlay.

I am sure that thousands of people will unite with me in testifying to you, and the gentlemen associated with you, their thanks for the lavish expenditure which has procured the beautiful series of engravings illustrating this volume. What I have been able only to hint at, the artists have interpreted with a fidelity to life and nature in the highest degree admirable.

I herewith present you the result of the joint labor of author and artists, “The Great South” volume. Permit me, sir, to dedicate it to you, and by means of this humble tribute to express my admiration for the energy and unsparing zeal with which you have carried to completion the largest enterprise of its kind ever undertaken by a monthly magazine.

Sincerely Yours.

EDWARD KING.

November 1, 1874.

THE GREAT SOUTH.

I.

louisiana past and present.

LOUISIANA to-day is Paradise Lost. In twenty years it may be Paradise Regained. It has unlimited, magnificent possibilities. Upon its bayou-penetrated soil, on its rich uplands and its vast prairies, a gigantic struggle is in progress. It is the battle of race with race, of the picturesque and unjust civilization of the past with the prosaic and leveling civilization of the present. For a century and a-half it was coveted by all nations; sought by those great colonizers of America, — the French, the English, the Spaniards. It has been in turn the plaything of monarchs and the bait of adventurers. Its history and tradition are leagued with all that was romantic in Europe and on the Western continent in the eighteenth century. From its immense limits outsprang the noble sisterhood of South-western States, whose inexhaustible domain affords an ample refuge for the poor of all the world.

A little more than half a century ago the frontier of Louisiana, with the Spanish internal provinces, extended nineteen hundred miles. The territory boasted a sea-coast line of five hundred miles on the Pacific Ocean; drew a boundary line seventeen hundred miles along the edge of the British-American dominions; thence followed the Mississippi by a comparative course for fourteen hundred miles; fronted the Mexican Gulf for seven hundred miles, and embraced within its limits nearly one million five hundred thousand square miles. Texas was a fragment broken from it. California, Kansas, the Indian Territory, Missouri, and Mississippi, were made from it, and still there was an Empire to spare, watered by five of the finest rivers of the world. Indiana, Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, and Nebraska were born of it.

From French Bienville to America Claiborne the territorial administrations were dramatic, diplomatic, bathed in the atmosphere of conspiracy. Superstition cast a weird veil of mystery over the great rivers, and Indian legend peopled every nook and cranny of the section with fantastic creations of untutored fancy. The humble roof of the log cabin on the banks of the Mississippi covered all the grace and elegance of French society of Louis the Fourteenth’s time. Jesuit and Cavalier carried European thought to the Indians.

Frenchman and Spaniard, Canadian and Yankee, intrigued and planned on Louisiana soil with an energy and fierceness displayed nowhere else in our early history. What wonder, after this cosmopolitan record, that even the fragment of Louisiana which has retained the name — this remnant embracing but a thirtieth of the area of the original province — yet still covering more than forty thousand square miles of prairie, alluvial, and sea marsh — what wonder that it is so richly varied, so charming, so unique?

Six o’clock, on Saturday evening, in the good old city of New Orleans. From the tower of the Cathedral St. Louis the tremulous harmony of bells drifts lightly on the cool spring breeze, and hovers like a benediction over the antique buildings, the blossoms and hedges in the square, and the broad and swiftly-flowing river. The bells are calling all in the parish to offer masses for the repose of the soul of the Cathedral’s founder, Don Andre Almonaster, once upon a time “perpetual regidor” of New Orleans. Every Saturday eve, for three-quarters of a century, the solemn music from the Cathedral belfry has brought the good Andre to mind; and the mellow notes, as we hear them, seem to call up visions of the quaint past.

Don Andre gave the Cathedral its dower in 1789, while the colony was under the domination of Charles the Fourth of Spain. The original edifice is gone now, and in its stead, since 1850, has stood a composite structure which is a monument to bad taste. Venerable

and imposing was the old Cathedral, with its melange of rustic, Tuscan, and Roman Doric styles of architecture; with its towers crowned with low spires, and its semicircular arched door, with clustered columns on either side at the front; and many a grand pageant had it seen.

Under the pavement of the Cathedral lies buried Father Antonio de Sedella, a Spanish priest, who, in his time, was one of the celebrities of New Orleans, and the very recollection of whom calls up memories of the Inquisition, of intrigue and mystery. Father Antonio’s name is sacred in the Louisiana capital, nevertheless; for although an enraged Spanish Governor once expelled him for presuming to establish the Inquisition in the colony, he came back, and flourished until 1837, under American rule, dying at the age of ninety, in the odor of sanctity, mourned by the women and worshiped by the children.

Now the sunlight mingles with the breeze bewitchingly; the old square, the gray and red buildings with massive walls and encircling balconies, the great door of the new Cathedral, all are lighted up. See! a black-robed woman, with downcast eyes, passes silently over the holy threshold; a blind beggar, with a parti-colored handkerchief wound about his weather-beaten head, hears the rustling of her gown, and stretches out his trembling hand for alms; a black girl looks wonderingly into the holy-water font; the market-women hush their chatter as they near the portal; a mulatto fruit-seller is lounging in the shade of an ancient arch, beneath the old Spanish Council House. This is not an American scene, and one almost persuades himself that he is in Europe, although ten minutes of rapid walking will bring him to streets and squares as generically American as any in Boston, Chicago, or St. Louis.

The city of New Orleans is fruitful in surprises. In a morning’s promenade, which shall not extend over an hundred acres, one may encounter the civilizations of Paris, of Madrid, of Messina; may stumble upon the semi-barbaric life of

the negro and the native Indian; may see the overworked American in his business establishment and in his elegant home; and may find, strangest of all, that each and every foreign type moves in a special current of its own, mingling little with the American, which is dominant: in it, yet not of it — as the Gulf Stream in the ocean.

But the older colonial landmarks in the city, as throughout the State and the Mississippi Valley, are fast disappearing. The imprint of French manners and customs will long remain, however; for it was produced by two periods of domination. The hatred of Napoleon the Great for the English was the motive which led to the cession of Louisiana to the United States: had he not come upon the stage of European politics, the Valley of the Father of Waters might have been French to-day; and both sides of Canal street would have reminded the European of Paris and Bordeaux.

The French Emperor, fearful lest the cannon of the English fleets might thunder at the gates of New Orleans when he was at war with England, at the beginning of this century, sold the “Earthly Paradise” to the United States. “The English,” said the man of destiny, “shall not have the Mississippi, which they covet.” And they did not get it. Seventy years ago the tide of crude, hasty American progress rushed in upon the lovely lowlands bordering the river and the Gulf; and it is astonishing that even a few landmarks of French and Spanish rule are left high above the flood.

Yonder is the archbishop’s palace: enter the street at one side of it, and you seem in a foreign land; in the avenue at the other you catch a glimpse of the rush and hurry of American traffic of to-day along the levée; you see the sharp-featured “river-hand,” hear his uncouth parlance, and recognize him for your countryman; you see huge piles of cotton bales; you hear the monotonous whistle of the gigantic white steamers arriving and departing; and the irrepressible negro slouches sullenly by with his hands in his pockets, and his cheeks distended with tobacco.

You must know much of the past of New Orleans and Louisiana to thoroughly understand their present. New England sprang from the Puritan mould; Louisiana from the French and Spanish civilizations of the eighteenth century. The one stands erect, vibrating with life and activity, austere and ambitious, upon its rocky shores; the other lies prone, its rich vitality dormant and passive, luxurious and unambitious, on the glorious shores of the tropic Gulf. The former was Anglo-Saxon and simple even to Spartan plainness at its outset; the latter was Franco-Spanish, subtle in the graces of the elder societies, self-indulgent and romantic at its beginning. And New Orleans was no more and no less the opposite of Boston in 1773 than a century later. It was a hardy rose which dared to blush, in the New England even of Governor Winthrop’s time, before June had dowered the land with beauty; it was an o’er modest Choctaw rose in the Louisiana of De Soto’s epoch which did not shower its petals on the fragrant turf in February.

In Louisiana summer lingers long after the rude winter of the North has done its work of devastation; the sleeping passion of the climate only wakes now and then into the anger of lightning or the terrible tears of the thunder-storm; there are no chronic March horrors of deadly wind or transpiercing cold; the sun is kind; the days are radiant.

Wandering from the ancient Place d’Armes, now dignified with the appellation of “Jackson Square,” through the older quarters of the city, one may readily recall the curious, changeful past of the commonwealth and its cosmopolitan capital; for there is a visible reminder at many a corner and on many a wall. It requires but little effort of imagination to restore the city to our view as it was in 1723, five years after Bienville, the second French Governor of Louisiana, had undertaken the dubious project of establishing a capital on the treacherous Mississippi’s bank.

Discouraged and faint almost unto death, after the terrible sufferings which he and his fellow-colonists had undergone at Biloxi, a bleak fort in a wilderness, he had dragged his weary limbs to the place on the river where New Orleans stands to-day, and there defiantly unfurled the flag of France, and made his last stand! Bienville was a man of vast courage and supreme daring; he had been drifting along the Mississippi, through the stretches of wilderness, since 1699; had vanquished Indian and beast of the forest; was skilled in the lore of the backwoodsman, as became hardy son of hardier Canadian father.

When he succeeded the alert and courageous Sauvolle as Governor of the colony, which had then become indisputably French, he entered upon a period of harrowing and petty vexations. He had to keep faithful and persistent watch at the entrance of the river from the Gulf, for, during many years England, France, and Spain were at war, and the Spaniards ever kept a jealous eye on French progress in America. The colony languished, and was inhabited by only a few vagabond Canadians, some dubious characters from France, and the Government officers. On the 14th of September, 1712, Louis the Magnificent granted to Anthony Crozat, a merchant prince, the Rothschild of the day, the exclusive privilege, for fifteen years, of trading in all the indefinitely bounded territory claimed by France as Louisiana.

Crozat obtained with his charter the additional privilege of sending a ship once a year for negroes to Africa, and of owning and working all the mines that might be discovered in the colony, provided that one-fourth of their proceeds should be reserved for the king. One ship-load of slaves to every two ship-loads of independent colonists was the proportion established for emigration to Louisiana more than a century and a half ago. Slavery was well begun.

In 1713 Bienville was displaced to make room for Cadillac, sent from France as Governor; a rude, quarrelsome man, who saw no good in the new colony, and hated and feared Bienville. But Cadillac’s daughter loved the quondam Governor whom her father’s arrival had degraded; and to save her from a wasted life, the proud Cadillac offered her in marriage to Bienville. The latter did not reciprocate the maid’s affection, and Cadillac, burning with rage, and anxious to avenge himself for this humiliation, sent Bienville with a small force on a dangerous expedition among the hostile Indians. He went, returning successful and unharmed. Cadillac’s temper soon caused his own downfall, and others, equally unsuccessful, succeeded him. Crozat’s schemes failed, and he relinquished the colony.

And then? Louisiana the indefinite and unfortunate fell into the clutches of John Law. The regent Duke of Orleans had decided to “foster and preserve the colony,” and in 1717 gave it to the “Company of the Indies,” a commercial oligarchy into which Law had blown the breath of life. The Royal Bank sprang into existence under Law’s enchanted wand; the charter of the Mississippi Company was registered at Paris, and the exclusive privilege of trading with Louisiana, during twenty-five years, was granted to that company.

France was flooded with rumors that Louisiana was the long-sought Eldorado; dupes were made by millions; princes waited in John Law’s anti-rooms in Paris. Then came the revulsion, the overturn of Law. Louisiana was no longer represented as the new Atlantis, but as the very mouth of the pit; and it was colonized only by thieves, murderers, beggars, and gypsies, gathered up by force throughout France and expelled from the kingdom.

After the bursting of the Law bubble, Bienville was once more appointed Governor of Louisiana, and his favorite town was selected as the capital of the territory. The seat of government was removed from New Biloxi to New Orleans, as the city was called in honor of the title of the regent of France.

Let us look at the New Orleans of the period between 1723 and 1730. Imagine a low-lying swamp, overgrown with a dense ragged forest, cut up into a thousand miniature islands by ruts and pools filled with stagnant water. Fancy a small cleared space along the superb river channel, a space often inundated, but partially reclaimed from the circumambient swamp, and divided into a host of small correct squares, each exactly like its neighbor, and so ditched within and without as to render wandering after nightfall perilous.

The ditch which ran along the four sides of every square in the city was filled with a composite of black mud and refuse, which, under a burning sun, sent forth a deadly odor. Around the city was a palisade and a gigantic moat; tall grasses grew up to the doors of the houses, and the hoarse chant of myriads of frogs mingled with the vesper songs of the colonists. Away where the waters of the Mississippi and of Lake Pontchartrain had formed a high ridge of land, was the “Leper’s Bluff;” and among the reeds from the city thitherward always lurked a host of criminals.

The negro, fresh from the African coast, then strode defiantly along the low shores by the stream; he had not learned the crouching, abject gait which a century of slavery afterwards gave him. He was punished if he rebelled; but he kept his dignity. In the humble dwellings which occupied the squares there were noble manners and graces; all the traditions and each finesse of the time had not been forgotten in the voyage from France: and airy gentlemenand stately dames promenaded in this queer, swamp-surrounded, river-endangered fortress, with Parisian grace and ease.

There were few churches, and the colonists gathered about great wooden crosses in the open air for the ceremonials of their religion There were twice as many negroes as white people in the city. Domestic animals were so scarce that he who injured or fatally wounded a horse or a cow was punished with death. Ursuline nuns and Jesuit fathers glided about the streets upon their scared missions. The principal avenues within the fortified enclosure were named after princes of the royal blood — Maine, Condé, Conti, Toulouse, and Bourbon; Chartres street took its name from that of the son of the regent of Orleans, and an avenue was named in honor of Governor Bienville.

Along the river, for many miles beyond the city, marquises and other noble representatives of aristocratic French families had established plantations, and lived luxurious lives of self-indulgence, without especially contributing to the wealth of the colony. Jews were banished from the bounds of Louisiana. Sundays and holidays were strictly observed, and negroes found working on Sunday were confiscated. No worship save the Catholic was allowed; white subjects were forbidden to marry or to live in concubinage with slaves, and masters were not allowed to force their slaves into any marriage against their will; the children of a negro slave-husband and a negro free-wife were all free; if the mother was a slave and the husband was free, the children shared the condition of the mother.

Slaves were forbidden to gather in crowds, by day or night, under any pretext, and if found assembled, were punished by the whip, or branded with the mark of the flower-de-luce, or executed. The slaves all wore marks or badges, and were not permitted to sell produce of any kind without the written consent of their masters. The protection and security of slaves in old age was well provided for; Christian negroes were permitted burial in consecrated ground. The slave who produced a bruise, or the “shedding of blood in the face,” on the person of his master, or any of the family to which he appertained, by striking them, was condemned to death; and the runaway slave, when caught, after the first offence, had his ears cut off, and was branded; after the second, was hamstrung and again branded; after the third, was condemned to death. Slaves who had been set free were still bound to show the profoundest respect to their “former masters, their widows and children,” under pain of severe penalties. Slave husbands and wives were not permitted to be seized and sold separately when belonging to the same master; and whenever slaves were appointed tutors to their masters’ children, they “were held and regarded as being thereby set free to all intents and purposes.”

The Choctaws and Chickasaws, neighbors to the colonists, were waging destructive war against each other; hurricanes regularly destroyed all the engineering works erected by the French Government at the mouths of the Mississippi; and expeditions against the Natchez and the Chickasaws, arrivals of ships from France with loads of troops, provisions, and wives for the colonists, the building of levées along the river front near New Orleans, and the occasional deposition from and re-instatement in office of Bienville, were the chief events in those crude days of the beginning.

I like to stand in these old Louisiana by-ways, and contemplate the progress of French civilization in them, now that it has been displaced by a newer one. I like to remember that New Orleans was named after the regent of France; that the beautiful lake lying between the city and the Gulf was christened after the splendid Pontchartrain, him of the lean and hungry look, and of the “smile of death,” him to whom the heart of Louis the Fourteenth was always open; and that the other lake, near the city, was named in memory of Maurepas, the wily adviser of Louis the Sixteenth and unlucky.

I like to remember that Louisiana itself owes its pretentious name to the devotion of its discoverer to the great monarch whom the joyous La Salle could not refrain from calling “the most puissant, most high, most invincible and victorious prince.” I like to picture to myself Allouez and Father Dablon, Marquette and Joliet, La Salle, Iberville, and Bienville, following in the footsteps of Garay and Leon, Cordova and Narvaez, De Vaca and Friar Mark; and finally tracing and identifying the current of the wild, mysterious Mississippi, which had been but a tradition for ages, until every nook and cranny, from the Falls of St. Anthony to the Gulf of Mexico, re-echoed to French words of command and prayer, as well as to gayest of French chansons.

Let us take another picture of New Orleans, from 1792 to 1797, thirty years after the King of France had bestowed upon “his cousin of Spain” the splendid gift of Louisiana, ceding it, “without any exception or reservation whatever, from the pure impulse of his generous heart.” That a country should, by a simple stroke of the pen, strip herself of possessions extending from the mouth of the Mississippi to the St. Lawrence, is almost incomprehensible.

France had perhaps already learned that her people had not in their breasts that eternal hunger for travel, that feverish unrest, which has made the Anglo-Saxon the most successful of colonists, and has given half the world to him and to his descendants. But the French had nobly done the work of pioneering. Sauvolle, grimly defying death at Biloxi; Bienville, urging the adventurous prow of his ship through the reeds at the Mississippi’s mouth, are among the most heroic figures in the early history of the country.

New Orleans from 1792 to 1797? Its civilization has changed; it is fitted into the iron groove of Spanish domination, and has become bigoted, narrow, and hostile to innovation. Along the streets, now lined with low, flat-roofed, balconied houses, out of whose walls peep little hints of Moorish architecture, stalks the lean and haughty Spanish cavalier, with his hand upon his sword; and the quavering voice of the night watchman, equipped with his traditional spear and lantern, is heard through the night hours proclaiming that all is “serene,” although at each corner lurks a fugitive from justice, waiting only until the watchman has passed to commit new crime. Six thousand souls now inhabit the city, there are hints in the air of a plague, and the Intendant has written home to the Council of State that “some affirm that the yellow fever is to be feared.”

The priests and friars are half-mad with despair because the mixed population pays so very little attention to its salvation from eternal damnation, and because the roystering officers and soldiers of the regiment of Louisiana admit that they have not been to mass for three years. The French hover about the few taverns and coffee-houses permitted in the city, and mutter rebellion against the Spaniard, whom they have always disliked. The Spanish and French schools are in perpetual collision; so are the manners, customs, diets, and languages of the respective nations. The Ursuline convent has refused to admit Spanish women who desire to become nuns, unless they learn the French language; and the ruling Governor, Baron Carondelet, has such small faith in the loyalty of the colonists that he has had the fortifications constructed with a view not only to protecting himself against attacks from without, but from within.

The city has suddenly taken on a wonderful aspect of barrack-yard and camp. On the side fronting the Mississippi are two small forts commanding the road and the river. On their strong and solid brick-coated parapets, Spanish sentinels are languidly pacing; and cannon look out ominously over the walls. Between these two forts, and so arranged as to cross its fires with them, fronting on the main street of the town, is a great battery commanding the river. Then there are forts at each of the salient angles of the long square forming the city, and a third a little beyond them — all armed with eight guns each. From one of these tiny forts to another, noisy dragoons are always clattering; officers are parading to and fro; government officials block the way; and the whole town looks like a Spanish garrison gradually growing, by some mysterious process of transformation, into a French city.

Yet the Spanish civilization does not and can not take a strong hold there. Spain does not give to New Orleans so many lasting historic souvenirs as France. Barracks, petty forts, dragoon stables, and many other quaint buildings finally disappear, leaving only the “Principal,” next the Cathedral, its fellow on the other side of the old church, some aged private dwellings, rapidly decaying, and a delicate imprint and suggestion of former Spanish rule scattered throughout various quarters of the city. But Spanish society still lingers, and in some parts of the old town the many-balconied, thick-walled houses for the moment mislead the visitor into the belief that he is in Spain until he hears the French language, or the curious Creole patois everywhere about him.

Let us take another look at the past of New Orleans. The Spaniard has gone his ways; Ulloa and O’Reilly, Unzaga, Galvez, and Miro, have held their governorships under the Spanish King. Carondelet, Gayoso, Casa-Calvo, and Salcedo alike have vanished. There have been insurrections on the part of the French; many longings after the old banner; and at last the government of France determines once more to possess the grand territory. Spain well knows that it is useless to oppose this decision; is not sorry, withal, to be rid of a colony so difficult to govern, and so near to the quarrelsome Americans, who have many times threatened to take New Orleans by force if any farther commercial regulations are made by Spaniards at the Mississippi’s outlet.

Napoleon the Great has three things to gain by the possession of the Territory: the command of the Gulf; the supply of the islands owned by France; and a place of settlement for surplus population. So that, at St. Ildefonso, on the morning of October first, 1800, a treaty of cession is signed by Spain, its third article reading as follows: “His Catholic Majesty promises and engages, on his part, to retrocede to the French Republic, six months after the full and entire execution of the conditions and stipulations herein relative to His Royal Highness the Duke of Parma — the colony or province of Louisiana, with the same extent that it now has in the hands of Spain, and that it had when France possessed it; and such as it should be after the treaties subsequently entered into between Spain and other states.”

This treaty is kept secret while the French fit out an expedition to sail and take sudden possession of the reacquired Territory; but the United States has sharp ears; and Minister Livingston besets the cabinet of the First Consul at Paris; fights a good battle of diplomacy; is dignified as well as aggressive; wins his cause; and Napoleon tells his counselors, on Easter Sunday, 1803, his resolve in the following words: “I know the full value of Louisiana, and I have been desirous of repairing the fault of the French negotiator who abandoned it in 1763; a few lines of a treaty have restored it to me, and I have scarcely recovered it when I must expect to lose it. But if it escapes from me, it shall one day cost dearer to those who oblige me to strip myself of it than to those to whom I wish to deliver it.” And it is forthwith ceded to the United States, in 1803, on the “tenth day of Floreal, in the eleventh year of the French republic,” in consideration of the payment by our government of sixty millions of francs.

Half a generation brings the conflicting national elements into something like harmony, and makes Louisiana a territory containing fifty thousand souls. The first steamboat ploughs through the waters of the Mississippi, but more stirring events also take place. In 1812 Congress declares that war exists between Great Britain and the United States, and early in 1815 General Andrew Jackson wins a decisive victory over the English arms, on the lowlands near New Orleans. Fifteen thousand skilled British soldiers are beaten off and sent home in disorder by the raw troops of the river States, by the stalwart Kentuckians, the hunters of Tennessee, the rough, hard-handed sons of Illinois, the dashing horsemen of Mississippi, and the handsome and athletic Creoles of Louisiana. When the victorious Americans return to New Orleans, a grand parade is held in the square henceforth to commemorate the name of Jackson, and where to-day stands a fine equestrian statue of the great general. In front of old Almonaster’s cathedral the troops are drawn up in order of review. Under a triumphal arch, from which glittering lines of bayonets stretch to the river, General Jackson, the hero of the Chalmette battle-field, passes, and bows low his laurel-crowned head to receive the apostolic benediction of the venerable Abbé.

II.

THE FRENCH QUARTER OF NEW ORLEANS —

THE REVOLUTION AND ITS EFFECTS.

LET me show you some pictures from the New Orleans of to-day. The nightmare of civil war has passed away, leaving the memory of visions which it is not my province — certainly not my wish — to renew. The Crescent City has grown so that Claiborne and Jackson could no longer recognize it. It was gaining immensely in wealth and population until the social and political revolutions following the war came with their terrible, crushing weight, and the work of re-establishing the commerce of the State has gone on under conditions most disheartening and depressing; though trial seems to have brought out a reserve of energy of which its possessors had never suspected themselves capable.

Step off from Canal street, that avenue of compromises which separates the French and the American quarters, some bright February morning, and you will at once find yourself in a foreign atmosphere. A walk into the French section enchants you; the characteristics of an American city vanish; this might be Toulouse, or Bordeaux, or Marseilles! The houses are all of stone or brick, stuccoed or painted; the windows of each story descend to the floors, opening, like doors, upon airy, pretty balconies, protected by iron railings; quaint dormer windows peer from the great roofs; the street doors are massive, and large enough to admit carriages into the stone-paved court-yards, from which stairways communicate with the upper apartments.

Sometimes, through a portal opened by a slender, dark-haired, bright-eyed Creole girl in black, you catch a glimpse of a garden, delicious with daintiest blossoms, purple and red and white gleaming from vines clambering along a gray wall; rose-bushes, with the grass about them strewn with petals; bosquets, green and symmetrical; luxuriant hedges, arbors, and refuges, trimmed by skillful hands; banks of verbenas; bewitching profusion of peach and apple blossoms; the dark green of the magnolia; in a quiet corner, the rich glow of the orange in its nest among the thick leaves of its parent tree; the palmetto, the catalpa; — a mass of bloom which laps the senses in slumbrous delight. Suddenly the door closes, and your paradise is lost, while Eve remains inside the gate!

From the balconies hang, idly flapping in the breeze, little painted tin placards, announcing “Furnished apartments to rent!” Alas! in too many of the old mansions you are ushered by a gray-faced woman clad in deepest black, with little children clinging jealously to her skirts, and you instinctively note by her manners and her speech that she did not rent rooms before the war. You pity her, and think of the multitudes of these gray-faced women; of the numbers of these silent, almost desolate houses.

Now and then, too, a knock at the porter’s lodge will bring to your view a bustling Creole dame, fat and fifty, redolent of garlic and new wine, and robust in voice as in person. How cheerily she retails her misfortunes, as if they were blessings! “An invalid husband — voyez-vous ça! Auguste a Confederate, of course — and is yet; but the pauvre garçon is unable to work, and we are very poor!” All this merrily, and in high key, while the young negress — the housemaid — stands lazily listening to her mistress’s French, nervously polishing with her huge lips the handle of the broom she holds in her broad, corded hands.

Business here, as in foreign cities, has usurped only half the domain; the shopkeepers live over their shops, and communicate to their commerce somewhat of the aroma of home. The dainty salon, where the ladies’ hairdresser holds sway, has its doorway enlivened by the baby; the grocer and his wife, the milliner and his daughter, are behind the counters in their respective shops. Here you pass a little café, with the awning drawn down, and, peering in, can distinguish half-a-dozen bald, rotund old boys drinking their evening absinthe, and playing picquet and vingt-et-un, exactly as in France.

Here, perhaps, is a touch of Americanism: a lazy negro, recumbent in a cart, with his eyes languidly closed, and one dirty foot sprawled on the sidewalk. No! even he responds to your question in French, which he speaks poorly though fluently French signs abound; there is a warehouse for wines and brandies from the heart of Southern France; here is a funeral notice, printed in deepest black: “The friends of Jean Baptiste,” etc., “are respectfully invited to be present at the funeral, which will take place at precisely four o’clock, on the ——.” The notice is on black-edged note-paper, nailed to a post. Here pass a group of French negroes, the buxom girls dressed with a certain grace, and with gayly-colored handkerchiefs wound about an unpardonable luxuriance of wool. Their cavaliers are clothed mainly in antiquated garments rapidly approaching the level of rags; and their patois resounds for half-a-dozen blocks.

Turning into a side street leading off from Royal, or Chartres, or Bourgogne, or Dauphin, or Rampart streets, you come upon an odd little shop, where the cobbler sits at his work in the shadow of a grand old Spanish arch; or upon a nest of curly-headed negro babies ensconced on a tailor’s bench at the window of a fine ancient mansion; or you look into a narrow room, glass-fronted, and see a long and well-spread table, surrounded by twenty Frenchmen and Frenchwomen, all talking at once over their eleven o’clock breakfast.

Or you may enter aristocratic restaurants, where the immaculate floors are only surpassed in cleanliness by the spotless linen of the tables; where a solemn dignity, as befits the refined pleasure of dinner, prevails, and where the waiter gives you the names of the dishes in both languages, and bestows on you a napkin large enough to serve you as a shroud, if this strange melange of French and Southern cookery should give you a fatal indigestion. The French families of position usually dine at four, as the theatre begins promptly at seven, both on Sundays and week days. There is the play-bill, in French, of course; and there are the typical Creole ladies, stopping for a moment to glance at it as they wend their way shopward. For it is the shopping hour; from eleven to two the streets of the old quarter are alive with elegantly, yet soberly attired ladies, always in couples, as French etiquette exacts that the unmarried lady shall never promenade without her maid or her mother.

One sees beautiful faces on the Rue Royale (Royal street), and in the balconies and lodges of the Opera House; sometimes, too, in the cool of the evening, there are fascinating little groups of the daughters of Creoles on the balconies, gayly chatting while the veil of the twilight is torn away, and the glory of the Southern moonlight is showered over the quiet streets.

The Creole ladies are not, as a rule, so highly educated as the gracious daughters of the “American quarter;” but they have an indefinable grace, a savoir in dress, and a piquant and alluring charm in person and conversation, which makes them universal favorites in society.

One of the chiefest of their attractions is the staccato and queerly-colored English, really French in idea and accent, which many of them speak. At the Saturday matinées, in the opera or comedy season at the French Theatre, you will see hundreds of the ladies of “the quarter;” and rarely can a finer grouping of lovely brunettes be found; nowhere a more tastefully-dressed and elegantly-mannered assembly.

The quiet which has reigned in the old French section since the war ended is, perhaps, abnormal; but it would be difficult to find village streets more tranquil than are the main avenues of this foreign quarter after nine at night. The long, splendid stretches of Rampart and Esplanade streets, with their rows of trees planted in the centre of the driveways, — the whitewashed trunks giving a fine effect of green and white, — are peaceful; the negro-nurses stroll on the sidewalks, chattering in quaint French to the little children of their former masters — now their “employers.”

There is no attempt on the part of the French or Spanish families to inaugurate style and fashion in the city; quiet home society, match-making and marrying of daughters, games and dinner parties, church, shopping, and calls in simple and unaffected manner, content them.

The majority of the people in the whole quarter seem to have a total disregard of the outside world, and when one hears them discussing the distracted condition of local politics, one can almost fancy them gossiping on matters entirely foreign to them, instead of on those vitally connected with their lives and property. They live very much among themselves. French by nature and training, they get but a faint reflection of the excitements in these United States. It is also astonishing to see how little the ordinary American citizen of New Orleans knows of his French neighbors; how ill he appreciates them. It is hard for him to talk five minutes about them without saying, “Well, we have a non-progressive element here; it will not be converted.” Having said which, he will perhaps paint in glowing colors the virtues and excellences of his French neighbors, though he cannot forgive them for taking so little interest in public affairs.

Here we are again at the Archbishop’s Palace, once the home of the Ursuline nuns, who now have, further down the river, a splendid new convent and school, surrounded by beautiful gardens. This ancient edifice was completed by the French Government in 1733, and is the oldest in Louisiana. Its Tuscan composite architecture, its porter’s lodge, and its interior garden with its curious shrine, make it well worth preserving, even when the tide of progress shall have reached this nook on Condé street. The Ursuline nuns occupied this site for nearly a century, and it was abandoned by them only because they were tempted, by the great rise in real estate in that vicinity, to sell. The new convent is richly endowed, and is one of the best seminaries in the South.

Many of the owners of property in the vicinity of the Archbishop’s Palace have removed to France, since the war, — doing nothing for the benefit of the metropolis which gave them their fortunes. The rent of these solidly-constructed old houses once brought them a sum which, when translated from dollars into francs, was colossal, and which the Parisian tradesmen tucked away into their strong boxes. Now they get almost nothing; the houses are mainly vacant. With the downfall of slavery, and the advent of reconstruction, came such radical changes in Louisiana politics and society that those belonging to the ancien régime who could flee, fled; and a prominent historian and gentleman of most honorable Creole descent told me that, among his immense acquaintance, he did not know a single person who would not leave the State if means were at hand.

The grooves in which society in Louisiana and New Orleans had run before the late struggle were so broken that even a residence in the State was distasteful to him and the society he represented; since the late war, he said, 500 years seemed to have passed over the common-wealth. The Italy of Augustus was not more dissimilar to the Italy of to-day than is the Louisiana of to-day to the Louisiana before the war. There was no longer the spirit to maintain the grand, unbounded hospitality once so characteristic of the South. Formerly, the guest would have been presented to planters who would have entertained him for days, in royal style, and who would have sent him forward in their own carriages, commended to the hospitality of their neighbors. Now these same planters were living upon corn and pork. “Most of these people,” said the gentleman, “have vanished from their homes; and I actually know ladies of culture and refinement, whose incomes were gigantic before the war, who are ‘washing’ for their daily bread. The misery, the despair, in hundreds of cases, are beyond belief.”

“Many lovely plantations,” said he, “are entirely deserted; the negroes will not remain upon them, but flock into the cities, or work on land which they have purchased for themselves.” He would not believe that the free negro did as much work for himself as he formerly did for his master. He considered the labor system at the present time terribly onerous for planters. The negroes were only profitable as field hands when they worked on shares, the planters furnishing them land, tools, horses, mules, and advancing them food. He said that he would not himself hire a negro even at small wages; he did not believe it would be profitable. The discouragement of the natives of Louisiana, he believed, arose in large degree from the difficulty of obtaining capital with which to begin anew. He knew instances where only $10,000 or $20,000 were needed for the improvement of water power, or of lands which would net hundreds of thousands. He had himself written repeatedly, urging people at the North to invest, but they would not, and alleged that they should not alter their determination so long as the present political condition prevailed.

He added, with great emphasis, that he did not think the people of the North would believe a statement which should give a faithful transcript of the present condition of affairs in Louisiana. The natives of the State could hardly realize it themselves; and it was not to be expected that strangers, of differing habits of life and thought, should do it. He did not blame the negro for his present incapacity, as he considered the black man an inferior being, peculiarly unfitted by ages of special training for what he was now called upon to undertake. The negro was, he thought, by nature, kindly, generous, courteous, susceptible of civilization only to a certain degree; devoid of moral consciousness, and usually, of course, ignorant. Not one out of a hundred, the whole State through, could write his name; and there had been fifty-five in one single Legislature who could neither read nor write. There was, according to him, scarcely a single man of color in the last Legislature who was competent in any large degree.

The Louisiana white people were in such terror of the negro government that they would rather accept any other despotism. A military dictator would be far preferable to them; they would go anywhere to escape the ignominy to which they were at present subjected. The crisis was demoralizing every one. Nobody worked with a will; every one was in debt. There was not a single piece of property in the city of New Orleans in which he would at present invest, although one could now buy for $5,000 or $10,000 property originally worth $50,000. He said it would not pay to purchase, the taxes were so enormous. The majority of the great plantations had been deserted on account of the excessive taxation. Only those familiar with the real causes of the despair could imagine how deep it was.

Benefit by immigration, he maintained, was impossible under the present régime. New-comers mingled in the distracted politics in such a manner as to neglect the development of the country. Thousands of the citizens were fleeing to Texas (and I could vouch for the correctness of that assertion). He said that the mass of immigrants became easily discouraged and broken down, because they began by working harder than the climate would permit.

In some instances, Germans on coming into the State had been ordered by organizations both of white and colored native workmen not to labor so much daily, as they were setting a dangerous example! Still, he believed that almost any white man would do as much work as three negroes. He hardly thought that in fifty years there would be any negroes in Louisiana. The race was rapidly diminishing. Planters who had owned three or four hundred slaves before the war, had kept a record of their movements, and found that more than half of them had died of want and neglect. The negroes did not know how to care for themselves. The women now on the same plantations where they had been owned as slaves gave birth to only one child where they had previously borne three. They would not bear children as of old; the negro population was rapidly decreasing. Gardening, he said, had proved an unprofitable experiment, because of the thievish propensities of the negro. All the potatoes, turnips, and cabbages consumed by the white people of New Orleans came from the West.

Such was the testimony of one who, although by no means unfair or bitterly partisan, perhaps allowed his discouragement to color all his views. He frankly accepted the results of the war, so far as the abolition of slavery and the consequent ruin of his own and thousands of other fortunes were concerned; he has, indeed, borne with all the evils which have arisen out of reconstruction, without murmuring until now, when he and thousands of his fellows are pushed to the wall. He is the representative of a very large class; the discouragement is no dream. It is written on the faces of the citizens; you may read and realize it there.

Ah! these faces, these faces; — expressing deeper pain, profounder discontent than were caused by the iron fate of the few years of the war! One sees them everywhere; on the street, at the theatre, in the salon, in the cars; and pauses for a moment, struck with the expression of entire despair — of complete helplessness, which has possessed their features. Sometimes the owners of the faces are one-armed and otherwise crippled; sometimes they bear no wounds or marks of wounds, and are in the prime and fullness of life; but the look is there still. Now and then it is controlled by a noble will, the pain of which it tells having been trampled under the feet of a great energy; but it is always there. The struggle is over, peace has been declared, but a generation has been doomed. The past has given to the future the dower of the present; there seems only a dead level of uninspiring struggle for those going out, and but small hope for those coming in. That is what the faces say; that is the burden of their sadness.

These are not of the loud-mouthed and bitter opponents of everything tending to reconsolidate the Union; these are not they who will tell you that some day the South will be united once more, and will rise in strength and strike a blow for freedom; but they are the payers of the price. The look is on the faces of the men who wore the swords of generals who led in disastrous measures; on the faces of women who have lost husbands, children, lovers, fortunes, homes, and comfort for evermore. The look is on the faces of the strong fighters, thinkers, and controllers of the Southern mind and heart; and here in Louisiana it will not brighten, because the wearers know that the great evils of disorganized labor, impoverished society, scattered families, race legislation, retributive tyranny and terrorism, with the power, like Nemesis of old, to wither and blast, leave no hope for this generation. Heaven have mercy on them! Their fate is too utterly inevitable not to command the strongest sympathy.

Of course, in the French quarter, there are multitudes of negroes who speak both French and English in the quaintest, most outlandish fashion; eliding whole syllables which seem necessary to sense, and breaking into extravagant exclamations on the slightest pretext. The French of the negroes is very much like that of young children; spoken far from plainly, but with a pretty grace which accords poorly with the exteriors of the speakers. The negro women, young and old, wander about the streets bareheaded and barearmed; now tugging their mistresses’ children, now carrying huge baskets on their heads, and walking under their heavy burdens with the gravity of queens. Now and then one sees a mulatto girl hardly less fair than the brown maid he saw at Sorrento, or in the vine-covered cottage at the little mountain town near Rome; now a giant matron, black as the tempest, and with features as pronounced in savagery as any of her Congo ancestors.

But the negroes, taken as a whole, seem somewhat shuffling and disorganized; and apart from the statuesque old house and body servants, who appear to have caught some dignity from their masters, they are by no means inviting. They gather in groups at the street corners just at nightfall, and while they chatter like monkeys, even about politics, they gesticulate violently. They live without much work, for their wants are few; and two days’ labor in a week, added to the fat roosters and turkeys that will walk into their clutches, keeps them in bed and board. They find ample amusement in the “heat o’ the sun,” the passers-by, and tobacco. There are families of color noticeable for intelligence and accomplishments, but, as a rule, the negro of the French quarter is thick-headed, light-hearted, improvident, and not too conscientious.

Perhaps one of the most patent proofs of the poverty now so bitterly felt among the hitherto well-to-do families in New Orleans was apparent in the suspension of the opera in the winter of 1873. Heretofore the Crescent City has rejoiced in brilliant seasons, both the French and Americans uniting in subscriptions sufficient to bring to them artists of unrivaled talent and culture. But opera entailed too heavy an expense, when the people who usually supported it were prostrate under the hands of plunderers, and a comedy company from the Paris theatres took its place upon the lyric stage. The French Opera House is a handsomely arranged building of modern construction, at the corner of Bourbon and Toulouse streets. The interior is elegantly decorated, and now during the season of six months the salle is nightly visited by hundreds of the subscribers, who take tickets for the whole season, and by the city’s floating population. Between each act of the pieces all the men in the theatre rise, stalk out, puff cigarettes, and sip iced raspberry-water and absinthe in the cafés, returning in a long procession just as the curtain rises again; while the ladies receive the visits of friends in the loges or in the private boxes, which they often occupy four evenings in the week. The New Orleans public, both French and American, possesses excellent theatrical taste, and is severely critical, especially in opera. It is difficult to find a Creole family of any pretensions in which music is not cultivated in large degree.

People in the French quarter very generally speak both prevailing languages, while the majority of the American residents do not affect the French. The Gallic children all speak English, and in the street-plays of the boys, as in their conversation, French and English idioms are strangely mingled. American boys call birds, fishes and animals by corrupted French names, handed down through seventy years of perversion, and a dreadful threat on the part of Young America is, that he will “mallerroo” you, which seems to hint that our old French friend malheureux, “unhappy,” has, with other words, undergone corruption. When an American boy wishes his comrade to make his kite fly higher, he says, poussez! just as the French boy does, and so on ad infinitum.

Any stranger who remains in the French quarter over Sunday will be amazed at the great number of funeral processions. It would seem, indeed, as if death came uniformly near the end of the week in order that people might be laid away on the Sabbath. The cemeteries, old and new, rich and poor, are scattered throughout the city, and most of them present an extremely beautiful appearance — the white tombs nestling among the dark-green foliage.

It would be difficult to dig a grave of the ordinary depth in the “Louisiana lowlands” without coming to water; and, consequently, burials in sealed tombs above ground are universal. The old French and Spanish cemeteries present long streets of cemented walls, with apertures into which once were thrust the noble and good of the land, as if they were put into ovens to be baked; and one may still read queer inscriptions, dated away back in the middle of the eighteenth century. Great numbers of the monuments both in the old and new cemeteries are very imposing; and, one sees every day, as in all Catholic communities, long processions of mourning relatives carrying flowers to place on the spot where their loved and lost are entombed; or catches a glimpse of some black-robed figure sitting motionless before a tomb. The St. Louis Cemetery is fine, and many dead are even better housed in it than they were in life. The St. Patrick, Cypress Grove, Firemen’s, Odd Fellows, and Jewish cemeteries, in the American quarter, are filled with richly-wrought tombs, and traversed by fine, tree-planted avenues.

The St. Louis Hotel is one of the most imposing monuments of the French quarter, as well as one of the finest hotels in the United States. It was originally built to combine a city exchange, hotel, bank, ball-rooms, and private stores. The rotunda, metamorphosed into a dining-hall, is one of the most beautiful in this country, and the great inner circle of the dome is richly frescoed with allegorical scenes and busts of eminent Americans, from the pencils of Canova and Pinoli. The immense ball-room is also superbly decorated. The St. Louis Hotel was very nearly destroyed by fire in 1840, but in less than two years was restored to its original splendor. On the eastern and western sides of Jackson Square are the Pontalba buildings, large and not especially handsome brick structures, erected by the Countess Pontalba, many years ago. Chartres street, and all the avenues contributing to it, are thoroughly French in character; cafés, wholesale stores, pharmacies, shops for articles of luxury, all bear evidence of Gallic taste.

Every street in the old city has its legend, either humorous or tragical; and each building which confesses to an hundred years has memories of foreign domination hovering about it. The elder families speak with bated breath and touching pride of their “ancestor who came with Bienville,” or with such and such Spanish Governors; and many a name among those of the Creoles has descended untarnished to its present possessors through centuries of valor and adventurous achievement.

III.

THE CARNIVAL — THE FRENCH MARKETS.

CARNIVAL keeps it hold upon the people along the Gulf shore, despite the troubles, vexations, and sacrifices to which they have been forced to submit since the social revolution began. White and black join in its masquerading, and the Crescent City rivals Naples in the beauty and richness of its displays. Galveston has caught the infection, and every year the King of the Carnival adds a city to the domain loyal to him. The saturnalia practiced before the entry into Lent are the least bit practical, because Americans find it impossible to lay aside business utterly even on Mardi-Gras. The device of the advertiser pokes its ugly face into the very heart of the masquerade, and brings base reality, whose hideous features, outlined under his domino, put a host of sweet illusions to flight.

The Carnival in New Orleans was organized in 1827, when a number of young Creole gentlemen, who had recently returned from Paris, formed a street-procession of maskers. It did not create a profound sensation — was considered the work of mad wags; and the festival languished until 1837, when there was a fine parade, which was succeeded by another still finer in 1839. From two o’clock in the afternoon until sunset of Shrove Tuesday, drum and fife, valve and trumpet, rang in the streets, and hundreds of maskers cut furious antics, and made day hideous. Thereafter, from 1840 to 1852, Mardi-Gras festival had varying popularity — such of the townspeople as had the money to spend now and then organizing a very fantastic and richly-dressed rout of mummers. At the old Orleans Theatre, balls of princely splendor were given; Europeans even came to join in the New World’s Carnival, and wrote home enthusiastic accounts of it. In 1857 the “Mistick Krewe of Comus,” a private organization of New Orleans gentlemen, made their début, and gave to the festivities a lustre which, thanks to their continued efforts, has never since quitted it. In 1857 the “Krewe” appeared in the guise of supernatural and mythological characters, and flooded the town with gods and demons, winding up the occasion with a grand ball at the Gaiety Theatre; previous to which they appeared in tableaux representing the “Tartarus” of the ancients, and Milton’s “Paradise Lost.” In 1858 this brilliant coterie of maskers renewed the enchantments of Mardi-Gras, by exhibiting the gods and goddesses of high Olympus and of the fretful sea, and again gave a series of brilliant tableaux. In 1859 they pictured the revels of the four great English holidays, May Day, Midsummer Eve, Christmas and Twelfth Night. In 1860 they illustrated American history in a series of superb groups of living statues mounted on moving pedestals. In 1861 they delighted the public with “Scenes from Life” — Childhood, Youth, Manhood and Old Age; and the ball at the Varieties Theatre was preceded by a series of grandiose tableaux which exceeded all former efforts. Then came the war; maskers threw aside their masks; but, in 1866, after the agony of the long struggle, Comus once more assembled his forces, and the transformations which Milton attributed to the sly spirit himself were the subject of the display. The wondering gazers were shown how Comus,

By sly enticement gives his baneful cup,

With many murmurs mixed, whose pleasing poison

The visage quite transforms of him that drinks,

And the inglorious likeness of a beast

Fixes instead.”

In 1867 Comus

became Epicurean, and blossomed into a walking bill of fare, the maskers

representing everything in the various courses and entrées of a

gourmand’s dinner, from oysters and sherry to the omelette brûlée,

the Kirsch and Curaçoa. A long and stately array of bottles, dishes of

meats and vegetables, and desserts, moved through the streets, awakening

saturnalian laughter wherever it passed. In 1868 the Krewe presented a

procession and tableaux from “Lalla Rookh;” in 1869, the “Five Senses;”

and in 1870, the “History of

Another feature has been added to the festivities, one which promises in time to be most attractive of all. It is the coming of Rex, most puissant King of Carnival. This amiable dignitary, depicted as a venerable man, with snow-white hair and beard, but still robust and warrior-like, made his first appearance on the Mississippi shores in 1872, and issued his proclamations through newspapers and upon placards, commanding all civil and military authorities to show subservience to him during his stay in “our good city of New Orleans.” Therefore, yearly, when the date of the recurrence of Mardi-Gras has been fixed, the mystic King issues his proclamation, and is announced as having arrived at New York, or whatever other port seemeth good. At once thereafter, and daily, the papers teem with reports of his progress through the country, interspersed with anecdotes of his heroic career, which is supposed to have lasted for many centuries. The court report is usually conceived somewhat in the style of the following paragraph, supposed to be an anecdote told at the “palace” by an “old gray-headed sentinel:”

“Another incident, illustrating the King’s courageous presence of mind, was related by the veteran. While sojourning at Auch (this was several centuries ago), a wing of the palace took fire, the whole staircase was in flames, and in the highest story was a feeble old woman, apparently cut off from any means of escape. His Majesty offered two thousand francs to any one who would save her from destruction, but no one presented himself. The King did not stop to deliberate; he wrapped his robes closely about him, called for a wet cloth — which he threw aside — then rushed to his carriage, and drove rapidly to the theatre, where he passed the evening listening to the singing of ’If ever I cease to love.’”

This is published seriously in the journals, next to the news and editorial paragraphs; and yearly, at one o’clock on the appointed day, the King, accompanied by Warwick, Earl-Marshal of the Empire, and by the Lord High Admiral, who is always depicted as suffering untold pangs from gout, arrives on Canal street, surrounded by troops of horse and foot, fantastically dressed, and followed by hundreds of maskers. Sometimes he comes up the river in a beautiful barge and lands amid thunderous salutes from the shipping at the wharves. This parade, which is gradually becoming one of the important features of the Carnival, is continued through all the principal streets of the city. The bœuf-Gras — the fat ox — is led in the procession.

The animal is gayly decorated with flowers and garlands. Mounted on pedestals extemporized from cotton-floats are dozens of allegorical groups, and the masks, although not so rich and costly as those of Comus and his crew, are quite as varied and mirth-provoking. The costumes of the King and his suite are gorgeous; and the troops of the United States, disguised as privates of Arabian artillery and as Egyptian spahis, do escort-duty to his Majesty. Rumor hath it, even, that on one occasion, the ladies of New Orleans presented a flag to an officer of the troops of “King Rex” (sic), little suspecting that it was thereafter to grace the Federal barracks. Thus the Carnival has its pleasant waggeries and surprises.

Froissart thought the English amused themselves sadly; and indeed, comparing the Carnival in Louisiana with the Carnival in reckless Italy, one might say that the Americans masquerade grimly. There is but little of that wild luxuriance of fun in the streets of New Orleans which has made Italian cities so famous; people go to their sports with an air of pride, but not of all-pervading enjoyment. In the French quarter, when Rex and his train enter the queer old streets, there are shoutings, chaffings, and dancings, the children chant little couplets on Mardi-Gras; and the balconies are crowded with spectators. But the negroes make a somewhat sorry show in the masking: their every-day garb is more picturesque.

Carnival culminates at night, after Rex and the “day procession” have retired.Thousands of people assemble in dense lines along the streets included in the published route of march; Canal street is brilliant with illumination, and swarms of persons occupy every porch, balcony, house-top, pedestal, carriage and mule-car. Then comes the train of Comus, and torch-bearers, disguised in outré masks, light up the way. After the round through the great city is completed, the reflection of the torch-light on the sky dies away, and the Krewe betake themselves to the Varieties Theatre, and present tableaux before the ball opens.

This theatre, during the hour or two preceding the Mardi-Gras ball, offers one of the loveliest sights in Christendom. From floor to ceiling, the parquet, dress-circle and galleries are one mass of dazzling toilets, none but ladies being given seats. White robes, delicate faces, dark, flashing eyes, luxuriant folds of glossy hair, tiny, faultlessly-gloved hands, — such is the vision that one sees through his opera-glass.

Delicious music swells softly on the perfumed air; the tableaux wax and wane like kaleidoscopic effects, when suddenly the curtain rises, and the joyous, grotesque maskers appear upon the ball-room floor. They dance; gradually ladies and their cavaliers leave all parts of the galleries, and come to join them; and then,

To chase the glowing hours with flying feet.”

Meantime, the King of the Carnival holds a levée and dancing party at another place; all the theatres and public halls are delivered up to the votaries of Terpsichore; and the fearless, who are willing to usher in Lent with sleepless eyes, stroll home in the glare of the splendid Southern sunrise, yearly vowing that each Mardi-Gras has surpassed its predecessor.

Business in New Orleans is not only entirely suspended on Shrove Tuesday (Mardi-Gras), but the Carnival authorities have absolute control of the city. They direct the police; they arrest the mayor, and he delivers to them the keys, while the chief functionaries of the city government declare their allegiance to “Rex;” addresses are delivered, and the processions move. The theatres are thrown open to the public, and woe betide the unhappy manager who dares refuse the order of the King to this effect. On one occasion a well-known actor arrived in the city during the festivities to fulfill an engagement, but as the managers of the theatre at which he was to act had refused to honor the King’s command for free admission to all, the actor was at once arrested, taken to the “den” of the Earl-Marshal, and there kept a close prisoner until a messenger arrived to say that the recalcitrant manager had at last “acknowledged the corn.” The violet is the royal flower; the imperial banner is of green and purple, with a white crown in the centre; and the anthem of the mystic monarch is, “If ever I cease to love.” The accumulation of costumes and armor, all of which are historically accurate, is about to result in the establishment of a valuable museum.

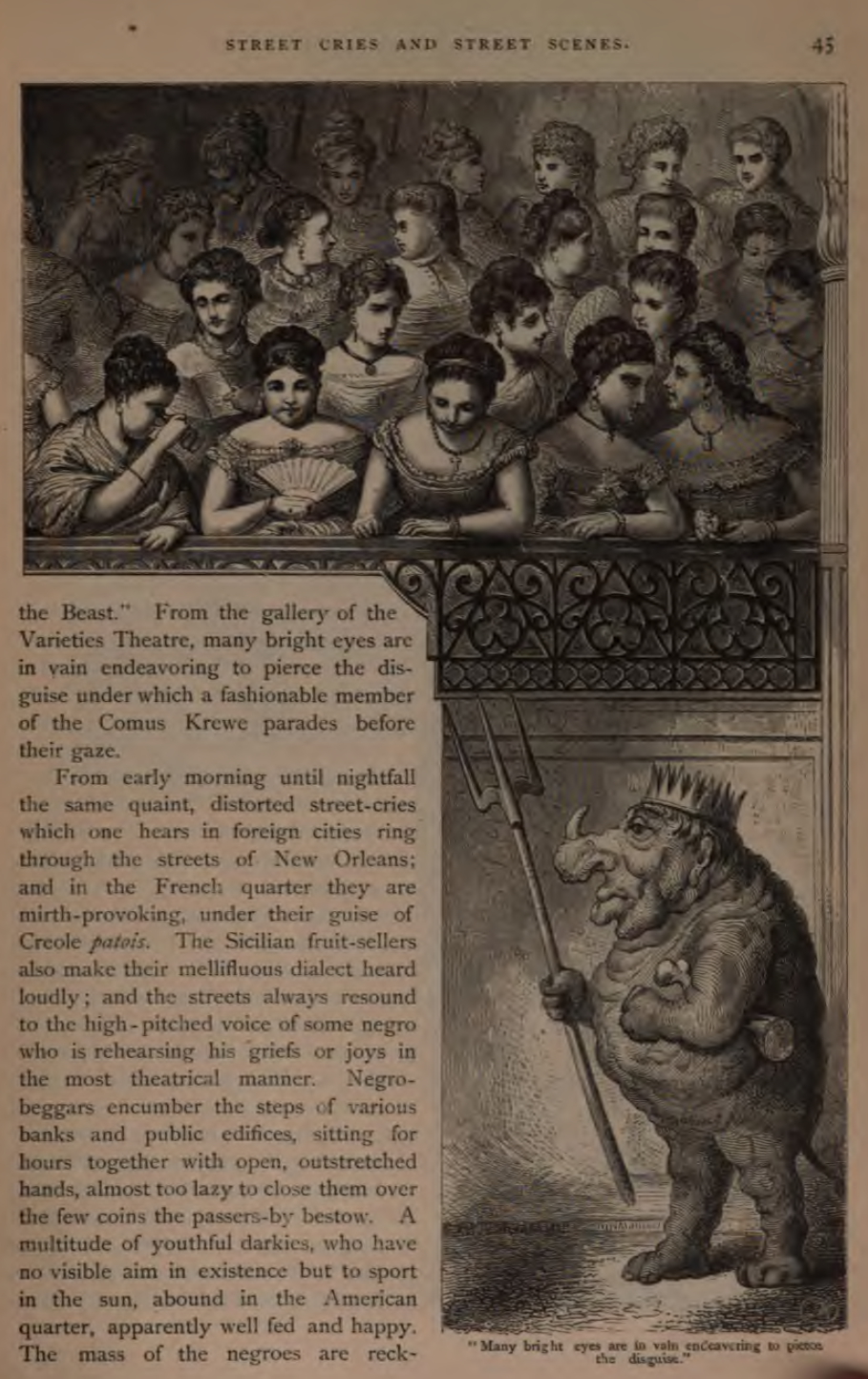

The artist’s pencil has reproduced in these pages one of the many comical incidents which enliven the Carnival tide, and calls his life sketch “Beauty and the Beast.” From the gallery of the Varieties Theatre, many bright eyes are in vain endeavoring to pierce the disguise under which a fashionable member of the Comus Krewe parades before their gaze.

From early morning until nightfall the same quaint, distorted street-cries which one hears in foreign cities ring through the streets of New Orleans; and in the French quarter they are mirth-provoking, under their guise of Creole patois. The Sicilian fruit-sellers also make their mellifluous dialect heard loudly; and the streets always resound to the high-pitched voice of some negro who is rehearsing his griefs or joys in the most theatrical manner. Negro-beggars encumber the steps of various banks and public edifices, sitting for hours together with open, outstretched hands, almost too lazy to close them over the few coins the passers-by bestow. A multitude of youthful darkies, who have no visible aim in existence but to sport in the sun, abound in the American quarter, apparently well fed and happy. The mass of the negroes are recklessly improvident, living, as in all cities, crowded together in ill-built and badly-ventilated cabins, the ready victims for almost any fell disease.

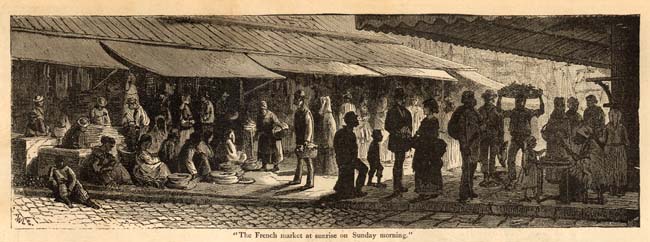

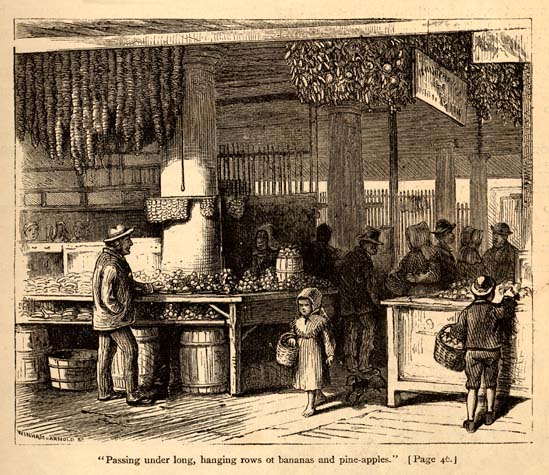

Next to the river traffic, the New Orleans markets are more picturesque than anything else appertaining to the city. They lie near the levée, and, as markets, are indeed clean, commodious, and always well stocked. But they have another and an especial charm to the traveler from the North, or to him who has never seen their great counterparts in Europe. The French market at sunrise on Sunday morning is the perfection of vivacious traffic. In gazing upon the scene, one can readily imagine himself in some city beyond the seas. From the stone houses, balconied, and fanciful in roof and window, come hosts of plump and pretty young negresses, chatting in their droll patois with monsieur the fish-dealer, before his wooden bench, or with the rotund and ever-laughing madame who sells little piles of potatoes, arranged on a shelf like cannon balls at an arsenal, or chaffering with the fruit-merchant, while passing under long, hanging rows of odorous bananas and pineapples, and beside heaps of oranges, whose color contrasts prettily with the swart or tawny faces of the purchasers.

During the morning hours of each day, the markets are veritable bee-hives of industry; ladies and servants flutter in and out of the long passages in endless throngs; but in the afternoon the stalls are nearly all deserted. One sees delicious types in these markets; he may wander for months in New Orleans without meeting them elsewhere. There is the rich savage face in which the struggle of Congo with French or Spanish blood is still going on; there is the old French market-woman, with her irrepressible form, her rosy cheeks, and the bandanna wound about her head, just as one may find her to this day at the Halles Centrales in Paris; there is the negress of the time of D’Artaguette, renewed in some of her grandchildren; there is the plaintive-looking Sicilian woman, who has been bullied all the morning by rough negroes and rougher white men as she sold oranges; and there is her dark, ferocious-looking husband, who handles his cigarette as if he were strangling an enemy.

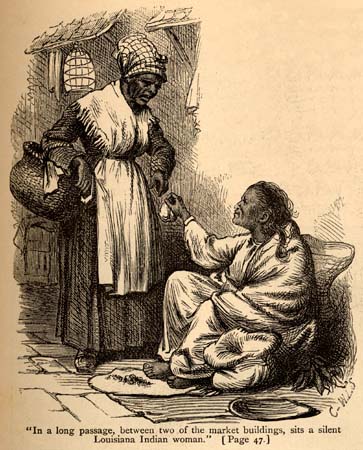

In a long passage, between two of the market buildings, where hundreds of people pass hourly, sits a silent Louisiana Indian woman, with a sack of gumbo spread out before her, and with eyes downcast, as if expecting harsh words rather than purchasers.