Mark LaFlaur.

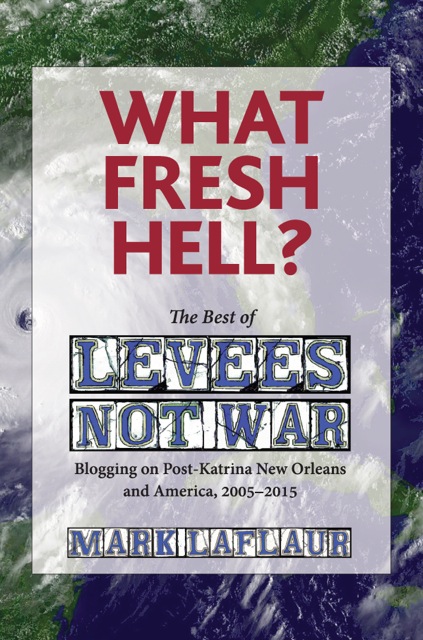

What Fresh Hell?

The Best of Levees not War.

© Mark LaFlaur.

Used by permission.

All rights reserved.

Introduction

What

fresh hell can this be?

Dorothy Parker

Isn’t it a bit backward to take a blog and make it into a book? Well, maybe, but at the same time, what’s the point of writing a blog if you can’t make a book out of it? As for backward, it’s always struck us as worse than reverse for an advanced nation like the United States to practically ignore its schools and public health and roads and levees while spending ever more billions on wars and overseas military bases. And isn’t it also retrograde to pretend our industries and our consuming ways of living don’t have some connection to the increasingly extreme weather and rising sea levels?

Levees Not War is a New Orleans-dedicated, New York-based blog that focuses on the environment, infrastructure, war and peace, and progressive politics — sexy things like that. We see these subjects as interrelated, inseparable, so it’s important to stay focused on multiple fronts at once, particularly as they affect New Orleans, Louisiana, the Gulf Coast, and America. The blog includes well-stocked sections on political action and how to help, with names and contact info of elected officials and relief and recovery organizations; a literature page with links to resources, reports, and videos; and interviews with authors and experts.

I started Levees Not War in the months following Hurricane Katrina (August 29, 2005). What would soon take shape as a website and then a blog began as a determined, persistent series of letters faxed and snail-mailed to members of Congress and to the news media, imploring them to keep the financial and humanitarian assistance coming to New Orleans and the Gulf Coast, and keep sending reporters and camera crews, please.

September 24, 2005.

The name of the blog comes from a sign I made for an anti-Iraq War march in Washington, D.C., on September 24, 2005, the weekend of Hurricane Rita, a month after Katrina. I’d thought I was being clever when I wrote “make levees, not war” on a big poster board. When we got to Washington (after our Amtrak train from Penn Station was delayed by a mysterious signal outage somewhere in New Jersey — more evidence of needed repairs to national infrastructure!), I found I was not as original as I’d thought: at least two dozen other protesters, all apparently independent of one another, had the same bright idea. The peace activism group Code Pink, too, carried a huge banner with the legend make levees not war.

The title of this book may sound familiar. “what fresh hell?” was the header that appeared at the top of an early version of Levees Not War, when it was more a crude website than a WordPress-style blog. During those years, so much bad news came in such a relentless barrage, on all fronts and with such intense velocity, that “What fresh hell do we have today?” was the attitude with which one unfolded the newspaper each morning. (There’s still as much bad news as ever, but in the George W. Bush years much of the hell was generated by the administration in power as it systematically dismantled or privatized key functions of government, reversed environmental protections, and went after the social safety net with chainsaws.) The phrase comes from Dorothy Parker, who is said to have grumbled “What fresh hell can this be?” each time the telephone or doorbell rang.

For someone who came of age around the time personal computers were being developed, before the Internet or the iPhone, there is something wonderful about the Web’s expanding universe of blogs and social media. Depending on where you click, it can be a nearly infinite storehouse of knowledge (e.g., Project Gutenberg) and a superb venue for good writing and investigative reporting — as long as the servers are up and the domain name is kept current, anyway. But there is also something reassuring, in a way that the Internet cannot quite duplicate, about a printed book as an enduring, time-tested preserver of an author’s writings. The book form (including the eBook) in addition to the blog is that extra bit of assurance that one’s words will not perish too quickly — and might reach new readers. And, besides, I’ve worked my whole adult life in publishing, so making a book feels like a natural thing to do. In a blog, of course, unless you keep listing previous writings in newer, related posts, the earlier pieces may easily be buried, like old newspapers piled in a corner: out of sight, out of mind. So, even though it may seem to be going against nature to publish a dead-tree edition of originally digital content, this Best Of collection is an attempt to keep readily accessible some writings from the past ten years that I hope will still be of interest even as more waves of fresh hell wash over us in the news cycles and Facebook and Twitter feeds.

Levees Not War was prompted by a wish to help my beloved home state and former residence — I had moved from New Orleans to New York City in 2001, just months before September 11. The letters and then the blog, launched in December 2005, were a way for a homesick transplant to try to help after the most destructive and traumatizing catastrophe in New Orleans’s three-hundred-year history.

In the aftermath of the storm, many electrical and phone lines were not working and cell phone towers were out, but text messages could be sent. The Times-Picayune hosted online message boards for community information, and New Orleans area bloggers posted updates about where essential services could (or could not) be found; which neighborhoods had regained electricity; where hot meals and cold drinks were being served; where you could recharge your laptop and mobile phone; which intersections’ traffic lights were still not working, and so on. There formed a community of bloggers in New Orleans, in some ways tight-knit and yet loose and informal. To name just a few: Your Right Hand Thief, People Get Ready, Hurricane Radio, Fix the Pumps, Library Chronicles, Humid City, Maitri’s VatulBlog, Tim’s Nameless Blog, and many more — see Levees Not War’s blogroll under In the Sunken City. One long-enduring event that grew out of this community is the annual Rising Tide conference on the future of New Orleans (see Part VI). Many of these bloggers are still active today, and a good sampling of their work appears in the excellent anthologies A Howling in the Wires (2010), edited by Sam Jasper and Mark Folse, and in Please Forward: How Blogging Reconnected New Orleans After Katrina (2015), edited by Cynthia Joyce. I am indebted to them all for ideas, inspiration, and friendship.

Now, part of the emotional energy behind Levees Not War — the indignant sense of injustice and determination to make things right — was unleashed when I read that a local Army Corps of Engineers project manager, Alfred Naomi, said that for $2.5 billion (modest on the scale of federal expenditures), the New Orleans area’s flood protection defenses could have been brought up to Category 5 strength — and yes, there were such plans ready for funding — which probably would have prevented what has become known as the federal flood. The U.S. at that time was (deficit) spending about $12 billion per week in Iraq, so $2.5 billion would have been about two and a half days’ worth.

Because of George W. Bush’s $1.35 trillion tax cut in 2001, unanticipated expenditures for homeland security after 9/11, and the costs of two wars, funding for Southeast Louisiana flood control projects in place since the mid 1990s was cut drastically. Nearly a dozen articles in the Times-Picayune in 2004 and 2005 cited the Iraq War as the reason for the huge cutbacks in funding for projects that had been approved by Congress and were under way when Bush took office. After the 2004 hurricane season, one of the worst in decades, the Bush administration and the Republican-led Congress slashed the Corps of Engineers New Orleans district’s FY2006 budget by $71.2 million, even as they were pushing a repeal of the estate tax on the wealthiest 2 percent. Predictably, after Katrina they claimed that a storm of this magnitude and destructiveness could not have been anticipated.

He shall judge the poor of the people, he shall save the children of the needy, and shall break in pieces the oppressor . . . he shall deliver the needy when he crieth; the poor also, and him that hath no helper.

In an interview in 2014 with Bruce R. Magee and Stephen Payne of the Louisiana Anthology podcast series, I was asked if there is a philosophy or moral vision behind Levees Not War. At the time Hurricane Katrina came knocking, I was already about a year and several hundred pages into a sprawling rough draft of what could charitably be described as political philosophy: an argument on behalf of the idea of the social contract. I wasn’t quite sure whether “social contract” was the exact term — it’s an age-old concept, as explained below — but what I was trying to get at was the idea that for moral reasons as well as for social stability there should be some kind of Golden Rule–like equilibrium of fairness in the society, in the conditions of life. (See “Does Believing in Social Contract Make Us Socialists?” in Part IV.) During the George W. Bush years, described by former labor secretary Robert B. Reich as a time of “corporate power in overdrive,” unfairness, greed, and indifference were all around, and coming in blows — as they are still. Especially amid widening wealth and income disparity — with the rich getting ever richer, corporate profits reaching new heights as corporate taxes drop to new lows, with jobs ever harder to find (or keep), and the nation’s social safety net for the poor and the middle class disintegrating (and not by accident) in a death by a thousand cuts — those who are very well-to-do ought to help the less fortunate without begrudging or insulting.

The idea of the social contract (or compact), an ancient concept that has taken various forms over the years (Rousseau, Locke, medieval coronation oaths, etc.) and dates at least as far back as King David’s covenant with the elders of Israel, holds that political authority derives from the consent of the governed (as it says in the Declaration of Independence). “The people themselves are the originating source of all the powers of government,” as Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in a Supreme Court ruling in June 2015. (Some of these ideas are enshrined in Magna Carta, whose eight-hundredth anniversary was being celebrated as this book was being assembled.) There is or should be a reciprocal agreement by which the people can rely upon the leader’s protection and benevolence in exchange for their allegiance. A balanced social contract would also rightly expect that all able-bodied citizens shall contribute to the common good through some kind of labor. Similarly, as the people agree to work and produce the goods of society, the wealthy and powerful share some of their abundance for the protection of the less affluent. Everyone should have some kind of work, and all who labor should not be without food and shelter. Everyone unable to work — the very young, the infirm, and disabled — should be assisted by the community. And the state, for the people’s labor and payments of taxes, shall in turn help educate and house the populace. The poor will always be with us, so programs and policies should be in place to assist them, with no grumbling from the blessed.

Conservative politicians are always paying homage to Ronald Reagan, so why not restore the upper-income tax rates to the 50 percent that the wealthy paid during the Reagan years of 1982–86? They can afford it. After all, in the past thirty years, more than four-fifths of the total increase in American incomes has gone to the richest 1 percent. Meanwhile, according to data from the 2010 U.S. Census, more than half the American population lives in poverty or is low-income.

A social contract would also involve taking better care of the earth, as good stewards of nature, God’s creation — not plundering and laying waste our only planet.

These, anyway, are some of the ideas I was working on at the time Hurricane Katrina struck, when all the shortcomings of American society — particularly of the downsized, privatized, and underfunded functions of its federal and state governments — became so starkly, painfully obvious to all who had eyes to see. After August 29, 2005, the leisurely work of composing a treatise of political philosophy had to give way to more urgent advocacy and action.

. . . It is here, under this oak where Evangeline waited for her lover, Gabriel, who never came. This oak is an immortal spot, made so by Longfellow’s poem, but Evangeline is not the only one who has waited here in disappointment.

Where are the schools that you have waited for your children to have, that have never come?

Where are the roads and the highways that you send your money to build, that are no nearer now than ever before?

Where are the institutions to care for the sick and disabled? . . .

Huey P. Long, 1928, St. Martinville, Louisiana

One of the reasons why I care so strongly about the social safety net and public works is that I came of age in a state where there was a proud and still-breathing tradition of progressive, liberal spending on behalf of public schools, hospitals for the poor, roads and bridges, and a good, low-priced state university on a beautiful campus. Louisiana, though a largely traditional and conservative state, once was a place where populist and agrarian-socialist ideas were not uncommon. When Huey P. Long took office as governor in 1928, the state had 30 miles of paved roads, no bridges across major rivers, and half the state’s children were unschooled. In three years 2,500 miles of paved roads, 6,000 miles of gravel roads, and 12 bridges were built, and by the end of the Great Depression about two-thirds of black children were attending public schools. Long provided new schools, hospitals — including a grand and massive new state-of-the-art facility for the centuries-old Charity Hospital in New Orleans — courthouses, free bridges across bayous, and a beautiful, well-funded and affordable state university at a time when other schools were contracting or closing. Importantly — and today’s elected officials might take note — he shifted most of the tax burden from individuals to industry, and slashed personal property taxes and fees. In order to fund the free textbooks for public schools, taxes were raised on the oil companies doing business in the state. (Standard Oil led an attempt to have him impeached.) It is well known that Huey Long grew corrupt and dictatorial, but when he was good he was very good for the state, in a way that no Louisiana governor had ever been before. It should be mentioned, too, that while he was generous to the public, Long was also fiscally conservative: in his term as governor (1928?32), taxes rose 2.2 percent compared to the 4.7 percent national average.

In this ten years’ collection you will find pieces on hurricanes, Louisiana’s environmental predicament, the BP disaster, and climate change; on infrastructure and public works in a time of job-killing scrooges (with a definite nostalgia for Franklin Roosevelt’s WPA and CCC programs); on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and beyond; plenty about politics, including a mad tea party and half-mute Democrats; blogging and merrymaking with friends in New Orleans, with a dash of burlesquery; on-the-scene reporting from Occupy Wall Street; remembrances of Katrina and 9/11, and tributes to activist leaders such as Medgar Evers, Tom Hayden, John F. Kennedy, and an early founder of Greenpeace. After the interviews with Harry Shearer and experts on the environment and infrastructure, there’s a bibliography to point readers to further sources of information, organizing, and activism. This and much more. Jump in at any point. I hope you enjoy the book — and the blog.

Contents

- Introduction 1

Part I: Hurricane Katrina and the Environment

- Remember August 29, 2005 11

- Understanding Louisiana’s Environmental Crisis 14

- Louisiana Flood Protection Agency Sues Big Oil to Repair Wetlands 18

- BP Found Grossly Negligent in Deepwater Horizon Spill 23

- BP Celebrates Earth Day with Bonfire, Oil Spill 25

- “Oil-Spotted Dick”: Cheney’s Oily Fingerprints in the BP Disaster 30

- If New Orleans Is Not Safe 36

- Hurricane Watch in New York City 37

- Something Called “Volcano Monitoring” 41

- LSU Fires Ivor van Heerden of LSU Hurricane Center 45

- Diagnosis of a Stressed-Out Planet 49

- Wrath of God? Global Warming and Extreme Weather 52

- Here Comes the Flood 57

Part II: ‘I’ Is for Infrastructure

- Public Works in a Time of Job-Killing Scrooges 67

- Framing the Case for Infrastructure Investment, Taxing the Rich 72

- Infrastructure, Baby, Infrastructure! A Defense of Stimulus Investments 75

- Republicans Secretly (Seriously) Like the Stimulus 78

- Barack, You’re Totally Our Infrastructure Hero! 82

- A Reply to “Obama Our Infrastructure Hero” from a New Orleans Engineer/Blogger 85

- American-Made: A WPA History for Our Time 87

- FDR, Treehugger-in-Chief, Inspires Hopes for Coastal Conservation Corps 90

Part III: War and Peace and War

- Eisenhower on the Opportunity Cost of the War Machine 97

- Obama Has Plans for ISIS; Now Congress Must Vote 98

- As “End” of Iraq War Is Announced, U.S. Digs In, Warns Iran 103

- As Combat Troops Leave Iraq, Where’s Our National Security” 111

- Ten Years of U.S. War in Afghanistan 114

- Mission Accomplished: Bin Laden Is Dead. Now Focus on Threats Closer to Home. 118

- Deeper into Afghanistan: 360 Degrees of Damnation 122

- In Honor of Veterans 128

- Jobs, Jobs . . . Senate Republicans Keep Vets Unemployed 130

- Grinch Wins Plastic Turkey Award: Pentagon Demands Repayment of Disabled Vets’ Signing Bonuses 133

- Approaching Five Years in Iraq, 4,000th U.S. Fatality 135

- Omigod! Infinite Iraqi Freedom! We’re Never Leaving! 137

Part IV: Politics, Society, and the Social Contract

- Is Katrina More Significant Than September 11? 141

- “Kill the Bill” vs. “Stop the War”: A Tale of Two Protests 145

- The Social Contract, Explained by Warren, Krugman, and Kuttner 156

- Does Believing in Social Contract Make Us Socialists? Then So Be It. 160

- Anti-Islamic Furor Helps al Qaeda, Endangers America 164

- Pajama Party 172

- Winter of Our Discontent 173

- Mad Tea Party with Chainsaws and Clowns 176

- Arguing about How to Defuse a Huge Ticking Bomb 179

- The Credit Crisis and the Social Contract 183

- The Destroyer 185

- Is the U.S. an Occupied Nation? 188

- Supreme Conservatives Drag U.S. Ceaselessly into the (Jim Crow) Past 189

- Democrats in the 2010 Midterms: A Failure to Communicate” Not a Failure to Govern 193

- Mr. Jindal, Tear Down This Ambition 200

- Jindal: From Rising Star to Black Hole 203

- What John Edwards Brought Us 205

Part V: Activism, Tributes, Remembrances

- We’re Not Forgetting 213

- On July 4, Yearning for a Progressive American Revolution 216

- On Independence Day, with Help from a Founding Mother 219

- Occupying Wall Street with Nurses, Teachers, Transit Workers, and the Rest of America’s Middle Class 223

- In Honor of Medgar Evers and Res Publica 227

- Tom Hayden and Todd Gitlin on the Port Huron Statement at 50 231

- Jim Bohlen, a Greenpeace Founder, Dies 244

- “And Death Shall Have No Dominion”: A Tribute to President John F. Kennedy 246

Part VI: In and About New Orleans

- What Is New Orleans? Resilient, a Moveable Feast, and Growing, Slowly 251

- In Memoriam: Greg Peters, “Suspect Device” Artist and Blogger, Father, Friend 254

- Rising Tide: Making Blogging (and Civics) Sexy in New Orleans 258

- Dedra Johnson of “The G Bitch Spot” Wins 2011 Ashley Award 266

- Viva New Orleans — for Art’s Sake! 269

- ReNEW, ReOPEN Charity Hospital 271

- Happy Mardi Gras (selections) 273

- Viva Burlesque! 276

Part VII: Interviews

- Harry Shearer 281

- Ivor van Heerden 291

- Mark Schleifstein 299

- Afterword 313

- Acknowledgments 317

- Bibliography 319

- Illustration Credits 327

- Index 331

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

LaFlaur, Mark. What Fresh Hell?: The Best of Levees Not War: Blogging on Post-Katrina New Orleans and America, 2005-2015. Kew Gardens, New York: Mid-City, 2015. Print. © Mark LaFlaur. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

LaFlaur, Mark. Levees Not War. Web. 21 Oct. 2015. <http:// www.levees notwar.org/>.