Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

The Journal of Latrobe.

In the possession of Ferdinand C. Latrobe, Esq.

By Charles Wilson Peale

CONTENTS

CHAPTER- By Sea to New Orleans

- New Orleans and Its People

- Peculiar Customs; With some Disjecta Membra upon Art Conventions

- Louisiana Limitations

CHAPTER VIII

BY SEA TO NEW ORLEANS

DECEMBER 17, 1818. On board the brig Clio; Captain Wynne, master. Left Baltimore twenty minutes before one o’clock, with a strong northwest wind, passed North Point at quarterpast two o’clock; at three, off Magotty, the wind chopped round to the southwest, and died away. Cast anchor. At sunrise, the 18th, the wind fresh from the northwest, a very fine day, fair and fresh wind. Got the cabin into order, and arranged our domestic hours of breakfast, dinner, and supper.

December 19th, about 1 a. m. Cast anchor off Old Point Comfort, to wait for a boat to take off the pilot. At sunrise weighed anchor, all hands sick.

Tuesday, the 22d, about 2 a. m. A perfect calm. The wind then shifted to the southwest, remarkably smooth sea without swell. At eight a very large shoal of porpoises played for an hour about the ship.

I have often heard that a shoal of porpoises round a ship indicates an approaching gale, and their direction to the point toward which they leave the ship to be that from which the storm will blow. In this instance the case was certainly so, for toward night the violence of the wind increased to a gale.

Thursday, the 24th. The wind during the night had got round to the north. The sea still as high as ever and wind not abated, but being quite favorable, the brig was put before it, and scudded under close reefed malntopsall and close reefed foresail. Got on deck and sat on the taffrall, from whence the motion of the brig through the most awful sea I ever beheld or imagined, at the rate of nine or ten knots, appeared the most wonderful effect of human art, and indeed of human courage, that can be imagined. The vessel is a most admirable sea boat, and skips over these mountainous waves without appearing to labor in the least. Several birds, of a species unknown to anyone on board, were flying near the water at no great distance from the ship, during the great part of the morning; the outer edge of the wing dark brown, pennon light ash color, back dark brown; could not distinguish the legs and bill,

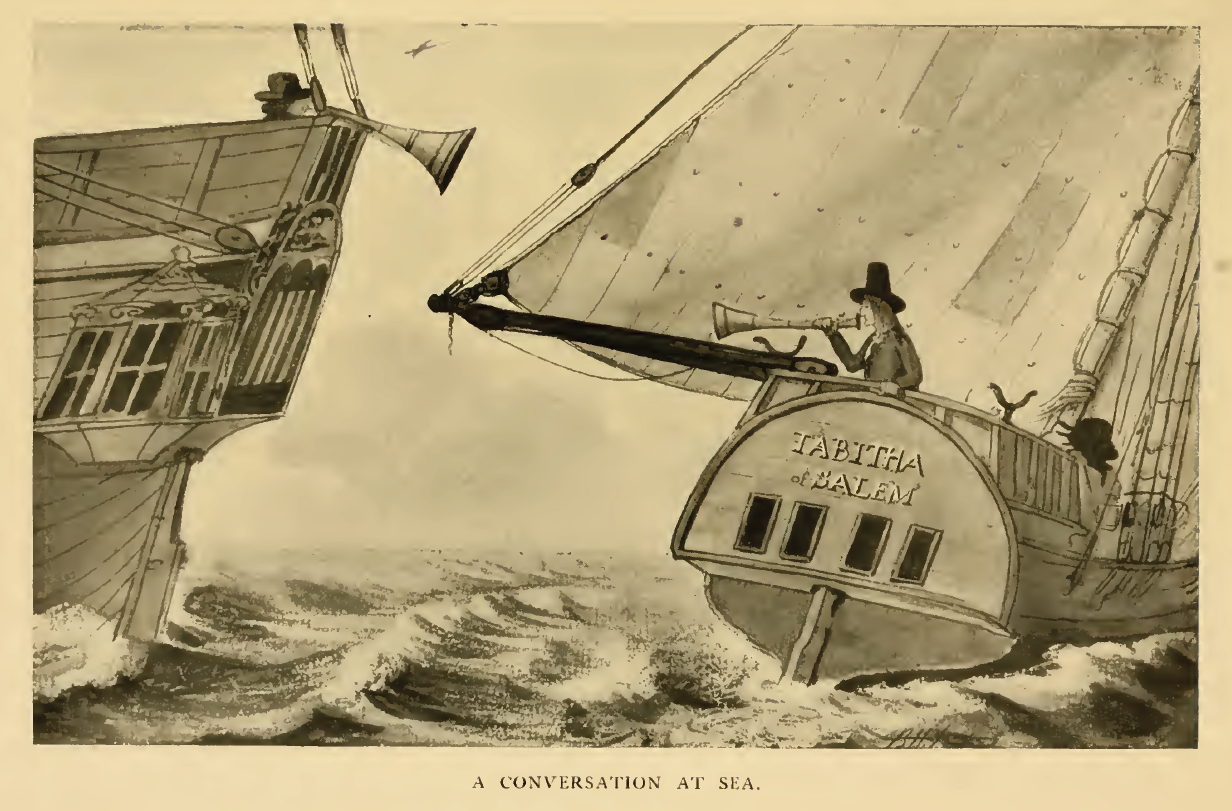

A CONVERSATION AT SEA

- Question.

- Hooooooagh!

- Answer.

- Hooooooooagh!

- Question.

- Whence came ye?

- Answer.

- From Stoningtown.

- Question.

- Where’s that?

- Answer.

- You’re a fine fellow for a captain not to know where Stoningtown is.

- Question.

- (Aside. Damn your Yankee soul!) Where are you bound?

- Answer.

- To Savannah, if ye know where that is.

- Question.

- What have you in?

- Answer.

- Only a few notions.

- Question.

- What’s your longitude?

- Answer.

- Right enough. Tebadiah, make sail, up helm.

Friday the 25th, Christmas day. Wind strong from the N.N.W. Got up more sail. All the passengers are dressed in honor of the day. The weather is now delightful, wind gentle, and, as I judge from my feelings, temperature about seventy degrees. Our party is so good-humored, from the captain to the second mate, that the day was spent very pleasantly, and the passengers remained on deck until eleven o’clock at night. A heavy dew reminded us of the necessity of retiring.

Saturday, the 26th. A magnificent sunset. The sky of Italy is deservedly celebrated. The singularity and brilliancy of this sky are not altogether peculiar to Italy, for in all latitudes, near to or upon the ocean, a similar sky prevails. It is a sky inimitable by the pencil.

Sunday, the 27th. A general shave and clean shirts. The captain’s birthday; celebrated by hot rolls at breakfast, a hog killed, apple pies for dinner, and a great variety of similar demonstrations of satisfaction. All these things are important in a sea voyage, and scatter flowers over the monotonous surface of so barren an existence.

The conversation is as multifarious as the habits and professions of the company — slave dealers, steamboats, tobacco, sea voyages. New Orleans and its manners, inhabitants, police, Mississippi, shipbuilding, etc. Mr. W. is the least informed of the company. He appears to be a sort of English agent, a most goodhumored creature, less opinionated than could be expected from his confined education and knowledge. He pointedly dislikes the government of his country, and sees clearly enough in what particulars America possesses superior advantages, both for the acquisition of wealth and on account of more generally diffused knowledge among the mass of the people. On this subject he one day discoursed very largely, and gave many instances within his own knowledge of the ignorance of the lower orders of the English respecting America and other foreign countries. After all were in their berths, M. and he continued their conversations from their beds across the cabin. M., who as a sailor has been several times in the East Indies and twice in China, was giving an account of the peculiar customs of the Chinese, and the difficulty of obtaining admission into their cities. Mr. W. observed that he should, of all things, like to be admitted to see the buildings of the cities of China; that he knew that foreigners could get into the suburbs of the city of China, which he believed was called Canton, but not into the city itself. It was with great difficulty, and much to the entertainment of his silent auditors, that M. explained to him that China is not a city but an extensive empire, of which Canton is a trading port, into the suburbs of which only foreigners could have access. W. persisted, and M. explained and exemplified for an hour, but I believe without convincing W. that China is not a walled town, for he suddenly recollected to have somewhere heard of the wall of China, and nobody could be so absurd as to believe that a country could be walled.

In truth, no greater proof of the want of a knowledge of the true state of foreign countries among the English in general could be adduced than this very conversation with W., unless it were the conduct of the English minister and of the generals during the late war.

Monday, 28th. I got up at the first dawn, and, remaining on deck till the sunrise, contemplated the magnificent star-spangled heavens with feelings that are not to be excited by any theological discussion, and which, founded on an exhibition of the power and benevolence of God that always exists and is not in the remotest degree dependent on opinion, must leave a permanent, habitual, and highly devotional impression on the heart. The gradual gilding of light clouds along the horizon preceded the glorious rise of the sun from the ocean. The increased knowledge of the construction of our solar system, of the general laws that govern the motion to the heavenly bodies, will forever prevent the revival of a religion in which the sun is considered as the living God of the world, to be adored as such, and propitiated by prayers and offerings, but surely no error deserves more indulgence, or is more natural, than the adoration of this glorious luminary as the God of our life and of our enjoyments. A trace of this idea remains in all the churches of Christendom excepting those having their origin more or less in the Reformation by Calvin and his followers. The situation of Catholic, Greek, and Church of England, as well as Lutheran altars, in the east of the church, and the consequent direction of the faces of worshipers to that point, is a vestige of the original religion of all uncivilized nations.

One of our black passengers, Tom, a negro belonging to. the notorious slave dealer Anderson, died this morning. He had been, with another, who came also sick aboard, sometime before his being sent off, in jail. He was most faithfully attended by our most humane captain and Dr. Day, and everything done for his recovery that the confined room in the vessel permitted. He had a mother and sisters on board, who treated him with very little kindness, and he would probably have recovered had they taken better care of him. As soon as we were off the bank, about 3 P. M., his body was committed to the sea. I read the Episcopal burial service on the occasion, every person on board attending. This man had cost Anderson $800 and his passage $30 more. He was a light mulatto and was expected to fetch $1,000 to $1,200 in Louisiana.

It appears to me, whatever may be said of the difficulty of suppressing the internal slave trade without infringing upon the rights of private property, as long as these men are considered as articles of legal traffic, that it certainly ought not to be aided by the Government or its officers. But this is certainly done, while the public jail is permitted to be a place of deposit for this sort of goods until they can be shipped. There is another man on board, half Indian, half negro, who came out of the same depot, the public jail of Baltimore, the same time with Tom, also sick — and, what is more noisome on board, absolutely eaten up with vermin. The only rags he possesses are those that were on his back on his being shipped. Captain Wynne, whose humanity to these poor wretches has been very active, and who has personally attended their wants, had him stripped and wrapped up in a blanket; his rags then were towed overboard, but I doubt whether the vermin would be expelled from them. The other colored people on board, and who are well clad and seem very respectable and orderly in their way, will neither approach nor assist this poor wretch, and had it not been for the captain’s attention, he would have starved, for they gave him nothing to eat for two days.

January 1, 1819. This being New Year’s, an extraordinary exertion was made to furnish our dinner table, and a boiled turkey marked the day, which, like all the rest, was spent in great good humor.

January 9, 1819. At daylight the wind, though very light, was favorable. The fog continued. We soon got under way and proceeded up the river, first through the wide bay from which the several passes, south and southwest, find their way into the Gulf of Mexico, then through a margin of reeds on both sides of the river about a mile wide. Presently large trees present themselves, thinly scattered on the west bank upon a narrow margin of more elevated ground. This growth continued to Fort Plaquemine or Fort St. Phillip, bombarded by the British during the late war and successfully defended by Colonel Overton.

After passing Plaquemine, low and mean houses, the residences of planters, appear occasionally on both sides of the river. Orange trees in the open air formed a short vista on the west bank, the first I had seen.

It is not easy to assign a cause for the present course of the Mississippi, although there is certainly an invincible necessity in the physical circumstances that belong to this mighty stream, which confines it to its present bed and forbids it to form any other.

The planters in the lower parts of the river are cultivators of rice. A large capital is required for the cultivation of sugar and coffee. The sugar plantations do not begin until within fifty miles of New Orleans. The first on a large scale is Johnson’s, formerly at the Balize, now a very rich man, as his solid and extensive sugar works prove. It has a large house of two stories of brick, with a portico on each front. All the other houses which I observed were of one story, low, and having a portico or piazza either all round, which is the old French style of building, or on each front. There are generally some orange trees growing about every house, sometimes forming a vista from the road to the door, sometimes planted in quincunx like an orchard. The larger plantations have a regular street of negro houses near the dwelling, many of them looking commodious and comfortable, with a belfry in the center to call the negroes to work. I saw an overseer directing the repair of the levee, with a long whip in his hand. The Creole French have the reputation of working their slaves very hard and feeding them very badly; the Americans are said to treat and feed them well.

On arriving at New Orleans in the morning, a sound more strange than any that is heard anywhere else in the world astonishes a stranger. It is a most incessant, loud, rapid, and various gabble of tongues of all tones that were ever heard at Babel. It is more to be compared with the sounds that issue from an extensive marsh, the residence of a million or two of frogs, from bullfrogs up to whistlers, than to anything else. It proceeded from the market and levee, a point to which we had cast anchor, and which, before we went ashore, was in a moment, by the sudden disappearance of the fog, laid open to our view.

New Orleans has, at first sight, a very imposing and handsome appearance, beyond any other city in the United States in which I have yet been. The strange and loud noise heard through the fog, on board the Clio, proceeding from the voices of the market people and their customers, was not more extraordinary than the appearance of these noisy folk when the fog cleared away and we landed. Everything had an odd look. For twenty-five years I have been a traveler only between New York and Richmond, and I confess that I felt myself in some degree again a cockney, for it was impossible not to stare at a sight wholly new even to one who has traveled much in Europe and America.

The first remarkable appearance was that of the market boats, differing in form and equipment from anything that floats on the Atlantic side of our country. We landed among the queer boats, some of which carried the tricolored flag of Napoleon, at the foot of a wooden flight of steps opposite to the center of the public square, which were badly fixed to the ragged bank. On the upper step of the flight sat a couple of Choctaw Indian women and a stark naked Indian girl. At the top of the flight we arrived on the levee extending along the front of the city. It is a wide bank of earth, level on the top to the width of perhaps fifty feet, and then sloping gradually in a very easy descent to the footway or banquet at the houses, a distance of about one hundred and fifty to two hundred feet from the edge of the levee. This footway is about five feet below the level of the levee, of course four feet below the surface of the water in the river at the time of the inundation, which rises to within one foot, sometimes less, at the top of the levee. Along the levee, as far as the eye could reach to the west, and to the market house to the east, were ranged two rows of market people, some having stalls or tables with a tilt or awning of canvas, but the majority having their wares lying on the ground, perhaps on a piece of canvas or a parcel of palmetto leaves. The articles to be sold were not more various than the sellers. White men and women, and of all hues of brown, and of all classes of faces, from round Yankees to grizzly and lean Spaniards, black negroes and negresses, filthy Indians half naked, mulattoes curly and straighthaired, quadroons of all shades, long haired and frizzled, women dressed in the most flaring yellow and scarlet gowns, the men capped and hatted. Their wares consisted of as many kinds as their faces. Innumerable wild ducks, oysters, poultry of all kinds, fish, bananas, piles of oranges, sugarcane, sweet and Irish potatoes, corn in the ear and husked, apples, carrots, and all sorts of other roots, eggs, trinkets, tinware, dry goods, in fact of more and odder things to be sold in that manner and place than I can enumerate. The market was full of wretched beef and other butcher’s-meat, and some excellent and large fish. I cannot suppose that my eye took in less than five hundred sellers and buyers, all of whom appeared to strain their voices to exceed each other in loudness. A little farther along the levee, on the margin of a heap of bricks, was a bookseller, whose stock of books, English and French, cut no mean appearance. Among others, there was a well-bound collection of pamphlets printed during the American war, forming ten octavo volumes, which I must get my friend Robertson of Congress, if here, to buy.

I was so amused by the market that I spent half an hour or more in it, walking from one end of the levee to the other, as far as it was occupied by the market people.

The public square, which is open to the river, has an admirable general effect, and is infinitely superior to anything in our Atlantic cities as a water view of the city. The whole of the wide parallel to the river is occupied by the cathedral in the center, and by two symmetrical buildings on each side. That to the west is called the Principal, and contains the public offices and council chamber of the city. That on the east is called the Presbytery, being the property of the church. It is divided into seven stores, with dwellings above, which are rented and produce a large revenue.

At the southwest corner of the square is a building of excellent effect. The lower story and entresol are rented by storekeepers; the upper story is a hotel, Tremoulet’s, at which I have taken up my quarters. The rest, to the west side of the square and the whole of the east side, is built in very mean stores, covered with most villainous roofs of tiles, partly white, partly red and black, with narrow galleries in the second story, the posts of which are mere unpainted sticks, but they let at an enormous rent. The square itself is neglected, the fence is ragged, and in many places open. Part of it is let for a depot of firewood, paving stones are heaped up in it, and along the whole of the side next to the river is a row of mean booths in which dry goods are sold by yellow, black, and white women, who dispose, I am told, of incredible quantities of slops and other articles fit for sailors and boatmen, and those sort of customers. Thus a square which might be made the handsomest in America is rather a nuisance than otherwise.

Tremoulet, who keeps this house, was, I am told, formerly a cook, an excellent station from which to rise to the dignity of the master of a large hotel. He has lived here under the Spanish, French, and American governments, and prefers the former. He has lost three large fortunes made in this place by his hotels, and is now poor and old. He and Madame Tremoulet, however, are the most vigorous and cheerful and generous old people imaginable. The causes of Tremoulet’s failures have been the bank and his generous disposition. When the American Government took possession, the bank soon offered facilities to commerce that had not before existed. Tremoulet, although he did not meddle with commerce, aided those who did by indorsement. Nothing, to a man unused to the terrible consequences of becoming security for others with no other counter security than their honesty or success, seems so pleasant as to be able to assist a friend, and perhaps make his fortune, by writing his name across the back of a slip of paper. That caution is indeed lulled to sleep which would be awake if the security were given in the shape of a bond or lien upon an estate, because a man who indorses a note for another, while he himself does not require the aid of a bank, naturally conceives that the loss of credit attending the nonpayment of the note by the drawer is a coercion operating in his favor, and tends to render him more certain that he will not be called upon to pay it, but that the drawer will make any sacrifices rather than have the note protested.

Tremoulet, from having built and owned the two largest hotels in the city, is now the tenant of Madame Castillion, to whom the stores in the public square belong. His house is by far the filthiest which I have ever inhabited, but my room is kept clean by an excellent servant whom I have bribed to attend me particularly. The growing Americanism of this city is strongly evident by the circumstance that Tremoulet’s is the only French boarding house in the city, that it is unfashionable, and when he removes, for he is going to the Havana, there will be no other open. My object in preferring this house is to reacquire a facility in speaking French, a facility which I have lost by thirty years’ disuse of that language. Whether my object will be answered I am doubtful, for the company is exceedingly mixed and daily changing, and some courage is required to venture to converse with strangers in a language imperfectly spoken. Another obstacle exists in the excessive rapidity with which they speak, and a greater, in their all speaking at once, and excessively loud. Some, among them Tremoulet himself, occasionally strike up a song, in which others join; in fact the noise and gabble is so incessant that Tremoulet, seeing me look with astonishment and a smile at the vociferous party, thought some sort of an apology necessary, and said: “Voyez vous, nous autres Français sont un peu bruyans.” It must, indeed, be acknowledged that the party of this house is not exactly that which would constitute the best society anywhere: storekeepers, planters, and some of Lallemand’s ruined party from the Trinity River. But they are all decent men, and two or three of them seem to be men of excellent information and polished manners.

The construction of the house, and of two or three others which I have seen, is entirely French. A lower story, divided into and let as stores, and an entresol in which the shopkeepers live, or which is let to other families; then a handsome range of apartments surrounding a court of thirty by twenty-four feet. The appearance externally of the house is very good, and if the whole square were thus built up it would be one of the handsomest in any country.

In the interior, the court gives light to all the stories, but is reserved only for the use of the principal story and is entered by a porte-cochère. Part of the entresol is also appropriated to the use of the hotel, which thus becomes very roomy and commodious. The proportions of this are not correct, the house being longer from north to south than from east to west, but the subdivision is correct.

I asked Tremoulet whether, as his house is much frequented, he could not find it to his interest to remain here where he is known and respected, and where in the same line he had already made two fortunes. He answered with a shrug, “Chacun n’aime point ce Gouvernement,” and then told me a romantic story that must for the present be deferred, but which proves that gratitude has not entirely disappeared from the surface of the earth, and that he will probably succeed better in Cuba.

CHAPTER IX

NEW ORLEANS AND ITS PEOPLE

WHAT is the state of society in New Orleans? Is one of many questions which I am required to answer by a friend, who seems not to be aware that this question is equivalent to that of Shakespeare’s Polonius. He might as well ask: What is the shape of a cloud? The state of society at any time here is puzzling. There are, in fact, three societies here — first the French, second the American, and third the mixed. The French side is not exactly what it was at the change of government, and the American is not strictly what it is in the Atlantic cities. The opportunity of growing rich by more active, extensive, and intelligent modes of agriculture and commerce has diminished the hospitality, destroyed the leisure, and added more selfishness to the character of the Creoles. The Americans, coming hither to make money and considering their residence as temporary, are doubly active in availing themselves of the enlarged opportunities of becoming wealthy which the place offers. On the whole, the state of society is similar to that of every city rapidly rising into wealth, and doing so much, and such fast increasing business, that no man can be said to have a moment’s leisure. Their business is to make money. They are in an eternal bustle. Their limbs, their heads, and their hearts move to that sole object. Cotton and tobacco, buying and selling, and all the rest of the occupation of a money-making community, fill their time and give the habit of their minds. The post which comes in and goes out three times a week renders those days, more than the others, days of oppressive exertion. I have been received with great hospitality, have dined out almost every day, but the time of a late dinner and a short sitting after it have been the only periods during which I could make any acquaintance with the gentlemen of the place. As it is now the Carnival, every evening is closed with a ball, or a play, or a concert. I have been to two of each.

To entitle a stranger to describe the character of a society, more is required than to have looked at it superficially, and through the medium of habits acquired elsewhere. More than a superficial use of the senses is required to ascertain facts of which the senses are the only judges. The great fault of travelers, I was going to say, especially of English travelers — because we Americans have suffered most by the false accounts of our country — is to impose first impressions upon themselves and the public for the actual states of things. To determine upon the relative moral or political character of a community requires more time, more talent, and a more philosophical investigation of the history of its habits, and of those causes of them over which no control can be exercised, than traveling bookmakers possess or can command.

It would therefore be very impertinent in me, after ten days’ residence only, to call anything which I may put into these brochures by a name more decided than my impressions respecting New Orleans.

My impressions, then, as to the surface of female society, are that there are collected in New Orleans at a ball, many women, below the age of twenty-four or twenty-five, of more correct and beautiful features, and with faces and figures more fit for the sculptor, than I ever recollect to have seen together elsewhere in the same number. A few of them are perfect, and a great majority are far above the mere agreeable. I have said faces for the sculptor, not altogether for the painter, for the lilies have banished the roses. The Anglican slang of a painted French woman does not apply here. A few American ladies, not long resident here, had rosy cheeks, but very few. The French Creoles are universally of healthy color, fair, but the cheeks are of the color of the forehead. At a bal paré the number of brunettes was small, and my attention being alive to the subject, I could not see one face that had the slightest tinge of rouge. There was a face and a head, the beautiful hair of which was decorated with a single white rose, surmounting a figure exquisitely formed and moving with perfect grace, belonging to some young lady apparently of eighteen, whom I am glad I do not know, but which was as perfect in all respects as anything I have ever seen in or out of marble.

The dancing of the ladies was what is to be expected of French women; that of the gentleman, what Lord Chesterfield would have called, too good for gentlemen. I hope and believe that we Americans have qualities which make up for our deficiency in dancing, a deficiency which marked those young Americans that were upon the floor.

I have never been in a public assembly altogether better conducted. No confusion, no embarrassment as to the sets having, in their turn, a right to occupy the floor, no bustle of managers, no obtrusive solicitors of public attention.

Altogether the impression was highly favorable. The only nuisance was a tall, ill-dressed black in the music gallery, who played the tambourine standing up, and in a forced and vile voice called the figures as they changed.

The French population in Louisiana is said to be only 20,000, in the city not above 5,000 or 6,000. The increase is of Americans. Some French have come hither since the return of the Bourbons, but they did not find themselves at home; some joined General Lallemand in his settlement on Trinity River, a few remained so as sensibly to increase the French population. The accession, if worth mentioning, did not exceed the emigration which has taken place of those who did not like the American Government, or had amassed fortunes and have returned to France or settled In the West Indian islands. Since the breaking of Lallemand’s colony, a few have returned to New Orleans, but so few that they are not a perceptible quantity, even in the comparatively small French community.

On the other hand, Americans are pouring in daily, not in families, but in large bodies. In a few years, therefore, this will be an American town. What is good and bad in the French manners and opinions must give way, and the American notions of right and wrong, of convenience and inconvenience, will take their place.

When this period arrives. It will be folly to say that they are better or worse than they now are. They will be changed, but they will be changed into that which is more agreeable to the new population than what now exists. But a man who fancies that he has seen the world on more sides than one cannot help wishing that a mean, an average character, of society may grow out of the intermixture of the French and American manners.

Such a consummation is, perhaps, to be more devoutly wished than hoped for. There Is a lady, and I am told a leading one among the Americans, who can speak French well, but is determined never to condescend to speak to the French ladies in their language, although in New York she prided herself on her knowing that language. Many of the leading gentlemen, when not talking of tobacco or cotton, find it very amusing to abuse and ridicule French morals, French manners, and French houses. In truth, there is evidently growing up a party spirit, which in time will give success to the views of the Americans, and everything French will in time disappear. Even the miserable patois of the Creoles will be heard only in the cypress swamps.

At present the most prominent, and, to the Americans, the most offensive feature of French habits is the manner in which they spend Sunday. For about ten years the recoil of the French revolutionary principles has made religious profession fashionable, especially in England, from whence our American public mind always, more or less, receives its tone. The Holy Alliance of Greek, Roman, Lutheran, and Calvinistic sovereigns, who before the battle of Waterloo most piously consigned each other, as far as religious belief went, to eternal damnation, has given authority of high effect to this fashion. For my part, the effect of this impious farce upon my own mind is to make me retire with the more humility into my own heart and seek there a temple unprofaned by external dictation. Sunday in New Orleans is distinguished only, first, by the flags that are hoisted on all the ships; second, by the attendance at church (the cathedral) of all the beautiful girls in the place, and of two or three hundred quadroons, negroes, and mulattoes, and perhaps of one hundred white males to hear high mass, during which the two bells of the cathedral are jingling; third, by the shutting up of the majority of the shops and warehouses kept by the Americans, and fourth, by the firing of the guns of most of the young gentlemen in the neighboring swamps, to whom Sunday affords leisure for field sports; fifth, the Presbyterian, Episcopal, and Methodist churches are also open on that day, and are attended by a large majority of the ladies of their respective congregations.

In other respects, no difference between Sunday and any other day exists. The shops are open, as well as the theater and the ballroom, and in the city, at least, “Sunday shines no holiday” to slaves and hirelings.

In how far the intermarriage of Americans with French girls will produce a less rigid observance of the gloom of an English Sunday, it is impossible to foresee. For some time an effect will be produced; for I have spent Sunday in a family in which a devout Quaker and a Presbyterian, who have married two sisters, joined in a very agreeable dance after a little concert. But the pulpit, now filled very ably by the Presbyterian clergyman, Mr. Learned, and the Episcopalian, Mr. Hull, directs its principal energy against this pretended profanation of the Sabbath; and with the countenance of the American majority perseverance will at last prevail, and Sundays will become gloomy and ennuyant, as elsewhere among us.

A bill was moved, I think, at the last session of the Legislature to put down the practice of dancing and shopkeeping prevailing here on Sunday. I am not quite sure of the fact, but I have heard it stated; but if the attempt was made, it did not succeed. Perhaps my early education on the continent of Europe has still an influence over my opinions, but certainly, had I been in the Legislature, I should have voted against the law to prohibit recreation of any sort on Sunday, on principle. If gambling is a recreation, it is also a vice; that is, it produces certain inevitable misery to the winner as well as the loser, and certain injury to their families and to the community at large. The more effectually, therefore, that sort of recreation is put down, not on Sunday only, but on all days, and the sooner, so much the better. I was also of the opinion that the shopkeeping ought to be put down, independently of any religious motives, because it forces those who have no interest in the sales — that is, the hired people and apprentices — to labor, and deprives them of the privilege of divine worship or of recreation, if you please, which every other individual, and probably the masters themselves, enjoys once in seven days. But my opinion is altered after being better informed, principally by conversation with Mr. Thomas Urquhart, one of the oldest inhabitants and most sensible men of this place. The slaves are by no means obliged to work anywhere in the State on Sunday, as has been stated, and is believed in the Eastern States by many — excepting in the sugar-boiling season, and to prevent danger from inundation when the river rises on the levee. They do, indeed, work at other seasons by the desire, perhaps by the order, of their masters; but it is understood, I believe it is a law, that if they do work they shall be paid for their labor, both in boiling sugar on Sunday and for every other kind of work.

In the neighborhood of New Orleans the land is valuable for the cultivation of sugar, and there is so little of it that were is not for the vegetables and fowls and small marketing of all sorts, raised by the negro slaves, the city would starve. To the negroes it is not labor, but frolic and recreation, to come to market. They have only Sunday on which to sell their truck. If more good than evil grows out of the license to these wretches to come to town and earn some comfort, some decent clothing, or even some finery for their families, by the sale of their articles, if the town is fed and the negro slave clothed thereby, it would be difficult to show how the prohibition of the practice and its consequences would be compensated by the forced idleness of these people throughout the week, as well as their idleness or forced attendance at church on Sunday. I have often listened to the Puritan doctrine on the subject of Sunday with astonishment, in so far as it prohibits as sin, a word of very elastic meaning, every innocent act satisfactory to the human heart as constituted by our Creator on one day in the week, which it allows on every other, and justifies this rigor by the Ten Commandments and the example of the early Christians. All that the second commandment directs is contained in these words: “Six days shalt thou labor, and on the seventh [not on the first] thou shalt do no manner of work, neither thou,” etc., etc. Now, recreation is certainly not herein forbidden, neither walking, nor dancing, nor music, nor any other act that gives innocent pleasure, and to which forced labor, either of servant or animal, is not required. In the country in which the Sabbath was instituted a more benevolent, a more just, and a more politic law could not have been established by the common Father of master and slave. There the relation of slave to the master was infinitely more distant and more oppressive than with us. The master was master of the life, as well as of the labor, of his servant. But there is no country, not even the countries in which this relation is wholly unknown to the laws, in which the difference of rank and of wealth does not put the labor of the poor at the disposal of the rich. It is, therefore, a wise and benevolent institution that says to power: “Thus far shalt thou go, and no farther.” But shall the slave, released from the constraint of his master, be told: “You are not compelled to work, but you shall not play; you shall listen for six days to the sound of the tabor and pipe issuing from your master’s mansion, and see at a distance, when you return to your hovel, the blaze of his festivity, and through his windows gape at the dance and the revel without sharing it, but on the seventh you shall go to church for an hour or two and the rest of the day you shall sit idle by force, ‘for every step in the dance is a step toward hell fire?’ It is no sin for your master to spend, during six days, the product of the sweat of your brow on musicians and gardeners and coachmen and footmen, and all the other means of innocent pleasure which the most pious allow themselves; but for you to do the little dancing, and playing of football or cricket, which you can do on the seventh, is a crying sin.” It will be hard to find this doctrine in the second commandment; still less will it be found that at the risk of real injury to themselves, and to the city which their labor during the week tends to supply with food, they are forbidden to indulge the useful recreation of going to market.

This long dissertation has been suggested by my accidentally stumbling upon an assembly of negroes, which, I am told, every Sunday afternoon meets on the Common in the rear of the city. My object was to take a walk on the bank of the Canal Carondelet as far as the Bayou St. John. In going up St. Peter’s Street and approaching the Common, I heard a most extraordinary noise, which I supposed to proceed from some horse-mill — the horses tramping on a wooden floor. I found, however, on emerging from the house to the Common that it proceeded from a crowd of five or six hundred persons, assembled in an open space or public square. I went to the spot and crowded near enough to see the performance. All those who were engaged in the business seemed to be blacks. I did not observe a dozen yellow faces. They were formed into circular groups, in the midst of four of which that I examined (but there were more of them) was a ring, the largest not ten feet in diameter. In the first were two women dancing. They held each a coarse handkerchief, extended by the corners, in their hands, and set to each other in a miserably dull and slow figure, hardly moving their feet or bodies. The music consisted of two drums and a stringed instrument. An old man sat astride of a cylindrical drum, about a foot in diameter, and beat it with incredible quickness with the edge of his hand and fingers. The other drum was an open-staved thing held between the knees and beaten in the same manner. They made an incredible noise. The most curious instrument, however, was a stringed instrument, which no doubt was imported from Africa. On the top of the finger board was the rude figure of a man in a sitting posture, and two pegs behind him to which the strings were fastened. The body was a calabash. It was played upon by a very little old man, apparently eighty or ninety years old. The women squalled out a burden to the playing, at intervals, consisting of two notes, as the negroes working in our cities respond to the song of their leader. Most of the circles contained the same sort of dances. One was larger, in which a ring of a dozen women walked, by way of dancing, round the music in the center. But the instruments were of different construction. One which from the color of the wood seemed new, consisted of a block cut into something of the form of a cricket bat, with a long and deep mortise down the center. This thing made a considerable noise, being beaten lustily on the side by a short stick. In the same orchestra was a square drum, looking like a stool, which made an abominable, loud noise; also a calabash with a round hole in it, the hole studded with brass nails, which was beaten by a woman with two short sticks. A man sung an uncouth song to the dancing, which I suppose was in some African language, for it was not French, and the women screamed a detestable burden on one single note. The allowed amusements of Sunday have, it seems, perpetuated here those of Africa among its former inhabitants. I have never seen anything more brutally savage and at the same time dull and stupid, than this whole exhibition. Continuing my walk about a mile along the canal, and returning after sunset near the same spot, the noise was still heard. There was not the least disorder among the crowd, nor do I learn, on inquiry, that these weekly meetings of the negroes have ever produced any mischief.

The general opinion of the masters and mistresses of the slaves in this city and neighborhood is that the Americans treat and feed and clothe their slaves well, but that the Creoles are, in all these respects, comparatively cruel to all these unfortunate people. In going into Davis’s ballroom and looking around the brilliant circle of ladies, it is impossible to imagine that any one of the fair, mild, and somewhat languid faces could express any feeling but of kindness and humanity. And yet several, I had almost said many, of these soft beauties had themselves handled the cowskin with a sort of savage pleasure, and those soft eyes had looked on the tortures of their slaves, inflicted by their orders, with satisfaction, while they had coolly prescribed the dose of infliction, the measure of which should stop short of the life of their property.

Madame Tremoulet — why should I conceal the name of such a termagant — is one of these notorious for their cruelty. She is a small, mild-faced creature, who weeps over the absence of her daughter, now with her husband in France. She has several servants; one a mulatto woman, by far the best house servant of her sex that I know of, famous also as a seamstress and for her good temper, so much so that she can at any time be sold for $2,000, and Tremoulet actually asks $3,000. Independently of her duty in a large boarding house, in waiting, and making beds, she is expected to make two shirts a day (and night) for the benefit of her mistress’ private purse. In six weeks I have never seen in her conduct the smallest fault; she is modest, obliging, and incredibly active. A few days ago she failed, because it was impossible, to make the bed of a stranger at the hour prescribed. In consequence of this fault, Madame Tremoulet had her stripped quite naked, tied to a bedpost, and she herself, in the presence of her daughter, Mrs. Turpin, the mother of three beautiful children, whipped her with a cowskin until she bled. Mrs. Turpin then observed: “Maman vous êtes trop bonne; pourquoi prcnez vous la peine de la fouetter vous-même, appellez done Guillaume.” William was called and made to whip her till she fainted. This scene made a noise in the house, and the blood betrayed it. Poor Sophy is ill and constantly crying. I shall leave the house as soon as convenient to me.

Madame —— is another of these hell cats. Her husband is a very amiable man, president of the Bank of Louisiana, whom she had driven to seek a divorce, but the matter has been compromised lately. She did actually whip a negress to death, and treated another so cruelly that she died a short time afterwards. Mr. —— , a principal merchant of this place, stated the facts to the grand jury, but it was hushed up from respect to the lady’s husband.

My landlady, a sensible Irish woman, saw through the fence preparations making by Madame C—— to punish several of her negroes. A ladder was brought and laid down and a naked man tied upon it. She was so shocked that she left her house for several hours and did not return until she supposed the execution was over. The first wife of —— was a beast of the same kind. A gentleman, whom I will not name, saw her stand by, some years ago, while a naked woman was tied on a ladder by her orders to undergo the punishment of the whip. He immediately turned about and departed.

At the ball on Washington’s birthday, the 22d, the idea of these things destroyed all the pleasure I should otherwise have felt in seeing the brilliant assemblage of as many beautiful faces and forms as I ever saw collected in one room. All pale, languid, and mild. I fancied that I saw a cowskin in every pretty hand, gracefully waved in the dance; and admired the comparative awkwardness of look and motion of my countrywomen, whose arms had never been rendered pliant by the exercise of the whip upon the bound and screaming slaves. Whatever, therefore, this community may lose in taste and elegance and exterior suavity, and acquire of serious and awkward bluntness, and commercial stiffness, may the change be as rapid as possible, if at the same time active humanity is introduced into the deplorable system of slavery, which, I fear, must long, perhaps forever, prevail in this State.

I begin to understand the town a little, as a collection of houses; and a curious town it is. It would be worth while, and if I can find time I will try to do something of the sort, to make a series of drawings representing the city as it now is, for it would be a safe wager that in a hundred years not a vestige will remain of the buildings as they now stand, excepting, perhaps, a few public buildings, and of houses built since the American acquisition of the country. The three most prominent buildings in the city are the cathedral, the Principal, and the Presbytery, already alluded to. They form the northwest side of the Place d’Armes. The cathedral occupies the center, the two others are perfectly symmetrical in their exterior, the Principal to the south, the Presbytery to the north of the church. Although in detail these buildings are as bad as they well can be, their symmetry and the good proportions and strong relief of the façades of the two latter and the solid mass of the former produce an admirable effect when seen from the river or the levee.

The construction of these buildings is curious. The foundations are laid about six inches below the natural surface, that is, the turf is shaved off, and logs then being laid level along the shallow trench, very solid piers and thick walls of brick are immediately built upon the logs. The cathedral Is bound together by numerous iron clamps, which appear externally in S’s and other forms; but I do not think they were very necessary, the settlement of buildings here being very equal and general, and few, if any, cramps appear on the outside of a few other buildings. The southeast corner of the Principal, however, has not settled as much as the rest of the front; for though no crack appears, the horizontal moldings are swayed down at least four inches toward the northeast. The corner that has not settled, as I was informed by the mayor, was built upon the foundation of an old wall; from which circumstance it would appear that the earth, once pressed down by considerable weight, does not afterwards admit of further condensation. In digging the foundation of my boring mill, I found the ground hardest at the very surface, and almost a quicksand on the northwest side, where the foundation of the old building obliged me to dig deeper.

Now called Jackson Square.

These three buildings are, in fact, the best looking in New Orleans at present. The hospital is a good design by my son. The New Orleans theater joined to Davis’s Assembly rooms is a thing that had not a striking effect. It is tame, but otherwise not a bad composition. The old theater of St. Philip has an unfinished front, which, if complete, would be rather pretty. After a longer residence I shall be better qualified to speak of the private houses. But this much I may say, that although the sort of house built here by the French is not the best specimen of French arrangement, yet it is infinitely, in my opinion, superior to that arrangement which we have inherited from the English. But so inveterate is habit that the merchants from the old United States, who are daily gaining ground in the manners and habits, the opinions and the domestic arrangements of the French, have already begun to introduce the detestable, lop-sided London house, in which a common passage and stairs acts as a common sewer to all the necessities of the dwelling, and renders it impossible to preserve a temperature within the house materially different from that of the atmosphere without, as the coughs, colds, and consumptions of our Eastern cities amply testify. With the English arrangement, the red brick fronts are also gaining ground, and the suburb St. Mary, the American suburb, already exhibits the flat, dull, dingy character of Market Street in Philadelphia, instead of the motley and picturesque effect of the stuccoed French buildings of the city. We shall introduce many grand and profitable improvements, but they will take the place of much elegance, ease, and some convenience.

The change which is gradually taking place in the character of this city is not very rapid compared with the march of society on the continent generally, but to the old inhabitants it must appear extraordinary enough. Much of what was a daily practice has entirely disappeared, never to return; for instance, the military parade of the intendant, and all the ceremony that belongs to the government of a city in which the people were only an appendage to the magistracy. The governor of the State is certainly the head of a much more important and powerful community than the Spanish authority ever reigned over. But the difference of respect with which the former is treated, compared with the submission shown to the latter whenever he appeared, is in an immense ratio entirely. I observed a remarkable instance of the democratic character of the citizens at the magnificent ball given at Davis’s, on Washington’s birthday. There were about three hundred gentlemen present, and probably four hundred ladies. When supper was ready, old Mr. Fortier, an old Creole of about seventy, with the spirits and manners of a boy of seventeen, who is a sort of self-elected master of the ceremonies, not only at balls, but at all private parties to which he is invited, stopped the dancing, and called out: “Il y a cinquante couverts, cinquante dames au souper, an souper, an souper!” About one hundred, however, sat down, and the gentlemen stood behind their chairs; another and another set succeeded. The third set did not fill the table, and the gentlemen sat down to it as fast as they could. The governor, Villere, the chief judge of the United States Circuit Court, an officer whom I do not know, Commodore Patterson, and the Mayor of Orleans, were shown to the head of the table by the managers. But all the places were occupied by young men, not one of whom would give way. I happened to be among them and immediately rose, offering my place to the governor, and giving a hint to my neighbors. They looked round, but not a man of them followed my example, and as I vacated only one place and did not sit down again, it was soon filled by somebody else.

The Catholic religion formerly was the only one permitted, and was carried on with all the pomp and ceremony of a Spanish establishment. The Host was carried to the sick in great parade, and all those whom it encountered knelt devoutly till it had passed. All that is now over, and I understand that the procession of the Host through the streets has not been seen here for several years.

When the American Government took possession of New Orleans, it found here a bishop, who was in full possession of all the ecclesiastical power belonging to his rank, and of a considerable share of civil authority. He did not remain here, but went to the Havana, where I am told he now resides. A vicar was appointed, I do not know by what authority, and the famous Abbé Dubourg was the man. There is here an old Spanish monk. Father Anthony, whose influence among the Catholics is unbounded. He did not like this new vicar, Abbé Dubourg, who — ambition is equal to his talents, and both are of the first magnitude — exerted himself to maintain his authority. He twice entered the pulpit But as soon as his voice was heard, a number in the church were seized with the most violent colds; they sneezed, coughed, spat, and, as decency required, rubbed out their spittle on the floor with their feet. They sat, in fact, so uneasily on their benches that they were obliged to be in perpetual motion, and did not recover anything like tranquillity until the abbé had finished his sermon.

The conduct of Father Antoine, in fact, was such that Archbishop Carrol suspended him, and I think Archbishop Mareschal has been obliged to do the same. He made his submission and was restored. Abbé Dubourg acquired a temporary éclat on the 8th of January, when he collected all the ladies in the church and performed high mass, while the men were fighting at the lines. The subsequent parade and a flaming oration à la Française kept him up for some time, and he then went to Italy and France. The Pope consecrated him Bishop of Orleans and he returned; but Father Anthony remained refractory, and yet refused to acknowledge his authority, no regular deposition or abdication of the Spanish bishop having taken place. The Catholic Church here, therefore, is in a kind of schismatic state. All matters of ceremony and faith are, I presume, as elsewhere; but the authority of the Holy Father at Rome appears to be disavowed in the person of the bishop he has consecrated and sent out. In the meantime, Bishop Dubourg, with the collection of priests, ornaments, and money which he has collected and begged in Europe, and which amount to forty of the former and a very large sum of the latter, has established himself at St. Louis, where he Is about to build his cathedral. In speaking on this subject to Archbishop Mareschal, at Baltimore, he seemed very rationally to think It best to let the schism die with Father Anthony.

Although the procession of the Host no longer parades the streets, the parade of funerals Is still a thing which Is peculiar to New Orleans, among all the American cities. I have twice met, accidentally, a funeral. They were both of colored people; for the coffin was carried by men of that race, and none but negroes and quadroons followed It. First marched a man in a military uniform with a drawn sword. Then came three boys in surplices, with pointed caps, two carrying staves with candlesticks in the form of urns at the top, and the third. In the center, a large silver cross. At some distance behind came Father Anthony and another priest, who seemed very merry at the ceremony of yesterday, and were engaged in loud and cheerful conversation. At some distance farther came the coffin. It was carried by four well-dressed black men, and to It were attached six white ribbons about two yards in length, the ends of which were held by six colored girls, very well dressed In white, with long veils. A crowd of colored people followed confusedly, many of whom carried candles lighted. I stood upon a step till the whole had passed, and counted sixty-nine candles.

About a month ago I attended high mass at the cathedral. All the usual motions were made; I think in greater profusion, indeed, than ordinary, and the common service performed in the common way. But what was unusual was the procession of the Host round the church; the Mortranza (literally the “showbox,” Latin pix, from which the exclamation “Please the pigs” — pix — is derived) was a very fine affair indeed, and an embroidered canopy was carried over it upon six silver staves, held by six very respectable-looking men.

One of my motives for going to the cathedral was the hope of hearing good and affecting church music. In this I was most sadly disappointed. There was no organ, at least the miserable organ which they have was not played. The voices, half a dozen, at least, of them, that chanted the service were the loudest and most unmusical that I ever heard in a church. The loudness was terrific, of one of them particularly, and as they chanted in unison, and in the most villainous taste imaginable, something between a metrical melody and a free recitative, it is not easy to conceive anything more diabolical.

The congregation consisted of at least four-fifths women, of which number one-half, at least, were colored. For many years I have not seen candles offered at the altars; but at each of the side altars there were half a dozen candles stuck upon the steps by old colored women, who seemed exceedingly devout.

At Baltimore, the metropolis of American Catholicism, the stages of the mass performing within the church is no longer announced to those who do not attend there. But here, the pious Catholic confined to his bed at home can follow the congregation in the church through the whole exhibition. The bell is kept at work as a signal, and when the Host is elevated. It rings a peal that is heard all over the city.

Father Anthony is said to be near eighty. He looks, indeed, so. He has a long, sharp face, with an aquiline nose and a gray beard, long and thin, which has once been red.

CHAPTER X

PECULIAR CUSTOMS, WITH SOME

DISJECTA MEMBRA

UPON ART CONVENTIONS

New Orleans, March 8, 1819.

I WALKED to-day to the burial grounds on the northwest side of the town. There is an inclosure for the Catholic Church of about three hundred feet square, and immediately adjoining is the burial place of the Protestants, of about equal dimensions. The Catholic tombs are of a very different character from those of our Eastern and Northern cities. They are of brick, much larger than necessary to inclose a single coffin, and plastered over so as to have a very solid and permanent appearance. They are of many shapes of similar character, covering each an area of seven or eight feet long and four or five feet wide, and being from five to seven feet high. They are crowded close together, without any particular attention to aspect. The range of the sides of the area is southwest and northeast, and northwest and southeast. It appeared to me possible that the confusion might arise from the different degrees of importance which the friends or priests might attach to the east and west position of the tomb, a position which was once considered an essential in the construction of a church, as well as in the placing of a tomb; and is a surviving remnant of Eastern worship which still hangs about our religious practice after being disavowed by our creeds. I was once told by a Catholic priest that the position of the coffin, with the feet to the east and the head to the west, was of the first importance, because that at the resurrection Christ would appear in the east, and if they were placed otherwise they would rise with their backs toward Him. Without intending to place this subject in a ludicrous light, I mention this opinion as a strong proof that the worship of the sun rising in the east -has strongly impregnated the religious practices of the Christian church; and assuredly, of all false worship, none appears to me more natural and pardonable than that of the rising sun.

In one corner of the Catholic burying ground are two sets of catacombs, of three stories each, roughly built, and occupying much more room than is necessary. Many of the catacombs were occupied, but not in regular succession, and the mouths of some were filled up with marble slabs having inscriptions. But more were bricked up and plastered, without any indication of the person’s name who occupies it. Of the tombs there are very few that are furnished with any inscription whatever. The few that are record only the name and the date of the birth and death of the deceased, with a very few exceptions. One of the catacombs had this simple epitaph on L. M. M. Villouet, aged twenty years:

More needed not to be said.

The Protestant burying ground has tombs of much the same construction, but a little varied in character, and they are all ranged parallel to the sides of the inclosure. The monument of the wife, child, and brother-in-law of Governor Claiborne is the most conspicuous, and has a panel enriched with very good sculpture, A female lies on a bed with her child lying across her body, both apparently just departed. A winged figure, pointing upward, holds over her head the crown of Immortality. At the foot of the bed kneels the husband in an attitude of extreme grief. The execution is very good, and it is less injured than might have been expected from its exposure in an open burial place. The governor’s rank is indicated by the fasces at the head of the bedstead.

There were two or three graves opened and expecting their tenants. Eight or nine inches below the surface they were filled with water and were not three feet deep. Thus all persons are here buried in the water. The surface of the burying ground must now be seven or eight feet below the level of the Mississippi, which has still five or six feet to rise before it attains its usual highest level. The ground was everywhere perforated by the crawfish, the amphibious lobster (écrevisse). I have, indeed, seen them in their usual attitude of defiance in the gutters of the streets. The French are fond of them, and make excellent and “handsome” soup of them, their scarlet shells being filled with forced meat and served up in the tureen. But the Americans, with true English anti-Gallican prejudices, disdain this species of the Cancer, although we delight in crabs and lobsters, the food of which we all know to be in the last degree disgusting. They pretend that the sellers of this fish collect them principally in the churchyards, which is not, I believe, true, and, in fact, impossible, considering the quantity that are sold.

We are all slaves, nationally and individually, of habit; our minds and our bodies are equally fashioned by education, and although the original dispositions of individuals give specific variety to character, the general sentiment, like the general manners, modes of living, and cooking, of sitting and standing and walking, can only be slowly changed by the gradual substitution of a new habit for the old.

In nothing does habit and general and long-continued practice guide a community more despotically than in the disposal of the bodies of the dead. The Parsees, in Hindostan, expose them in the open air to be devoured by vultures, and judge of the happiness or misery of the departed soul by the attack of the birds upon the right or left eye. The rich Hindoos burn and the poor throw their dead into the river to be devoured by alligators or fish. We bury them, as food for worms and crawfish. At sea we deliver them to the sharks, crabs, and lobsters. Those who can afford it inclose them in leaden and stone coffins, as if jealous of the appetites of the vermin to whom they might give nourishment; while the ancient Egyptians and the European princes and nobles embalm the bones and fleshy parts and leave the bowels to shift for themselves in leaden boxes. In many places in Sicily and Italy and Malta the bodies are preserved by drying. The Greeks and Romans committed them to the flames. Of all these modes of getting rid of the dead body, the latter is, after all, productive of the least annoyance, and most completely avoids that accumulation which we find so very inconvenient, and which inevitably attends our mode of burial.

I do not recollect to have met in any author, ancient or modern, with any account of the manner and the reasons of the change in the usual mode of disposing of the dead, after the promulgation of Christianity, and of the substitution of the grave for the funeral pile. But it seems to have naturally grown out of the doctrine of the resurrection of the body, of the very body which the soul inhabited in this state of our existence. The dissipation of all its parts by the action of fire appeared so near an approach to annihilation that it was, I presume, the natural consequence of the new doctrine that the body, after death, should be as well preserved in the ground as possible. “The graves shall give up their dead.” Besides, the early Christians were of opinion that the day of judgment and the resurrection of the body would take place during the existence of the first or second generation after Christ — an opinion which appears to have been that of St. Paul. “We shall not all die, but we shall be all changed.” And though this text is explained away, as well as that of Christ, “Verily, verily, I say unto you, that this generation shall not pass away before these things come to pass,” yet those who are not polemical theologians have a right to take them in their natural sense.

The whole event of the resurrection of the natural body must be the work of omnipotence; and it cannot, therefore, be of any importance whether the particles of which it consists be dissipated by fire or by any other mode of dissolution. In either mode the individuality is destroyed, and a new synthesis must take place.

I cannot, therefore, help wishing on many accounts that the burning of bodies had continued to be the practice of Christians. The health of cities, the convenience, as respects public squares and building grounds, are greatly involved in our practice. At the cathedral in Baltimore, and, in fact, in most great cities, the existence of graveyards has been found a serious nuisance. The great operation at Paris, in removing the dead from the cemetery of Les Innocents, is an astonishing instance of the expensive efforts that have been found necessary to get rid of them, an operation that none but Frenchmen could have conceived or executed. But there are other reasons for which I would give a preference to the Greek and Roman practice. Those who have lost friends, especially of a different sex from themselves, and have hearts to feel, need not be told that whatever philosophical indifference may have existed respecting the fate of their own bodies after death, those of their friends become infinitely dear to them, and that no display of their affection is considered too extravagant or too expensive to be indulged and executed. But if habit did not reconcile us to everything, how inconsistent with the delicate enthusiasm of a husband respecting the body of his wife and child does it not seem to put it into a hole full of stagnant water about three feet deep, to be there devoured by crawfish, as is done unavoidably in New Orleans, or to place it in a catacomb where the worms may dispose of it!

Now, if the body were burned, and the ashes separately retained, which may easily be done by many methods, besides the expensive one of sheets of asbestos, if they ever were used, the space occupied would be so small and the remains so entirely inoffensive to any sense that all objections, public and private, would vanish which render the preservation of what Is left behind of those we loved so difficult, expensive, and, in most cases, impossible. And if the urns that inclose the ashes of our departed friends were placed in our view, the delightful sentiment of posthumous affection would be longer kept alive, and its moral effect be stronger and more beneficial.

I have a confused recollection of the account given to me by Mr. Foster, the British minister, of the discovery of the tomb of Aspasla. Within the monument was a large marble urn, or vase, exquisitely sculptured, with decorations of cheerful import. Within this outer vase was found an urn of bronze of small size, but of the most exquisite workmanship, containing the ashes of that extraordinary woman, who, to the talents and acquirements of the Baroness de Stael, added a most refined and graceful taste and exquisite beauty, although her moral character, judged on the most latitudinarian of Athenian libertinism, must always be an object of disgust. Upon the ashes, which only partly filled the urn, lay a wreath of gold, the most perfect effort of art, a wreath composed of a sprig of laurel and one of myrtle.

There is some difference between such a monument to departed worth and the death’s heads and cross bones of our churchyards.

March 16, 1819.

I happened this morning to be in the dry-goods store of Mrs. Herries, a lady who formerly, as the wife of the rich Banker Herries, of Buffalo, figured in the highest circles of fashion; and now, one of the many ruins of the French Revolution, still exhibits in her manners and language the characters of former taste and elegance. At the same time she has had the good sense not to be ashamed of her present situation and employment, and is a most admirable and attentive shopwoman, both to her customers and to her interest.

While I was in the shop a mulatto man came in and asked for some shawls. Mrs. Herries produced some very elegant ones, which the man looked at with an apparent intention to buy, but said he had no money with him, but that, if her woman was out with shawls and she called at the house, one would be bought and paid for, Mrs. Herries replied that her woman was not out that morning, but should go out, and the man went away.

This circumstance induced me to make inquiries as to the details of a mode of retail trade which I had long observed, and which had excited my curiosity. In every street, during the whole day, women, chiefly black women, are met carrying baskets upon their heads and calling at the doors of houses. These baskets contain assortments of dry goods, sometimes, to appearance, to a considerable amount. The shawls at Mrs. Herries’s which the man looked at cost from $28 to $50 each, and were many of them exceedingly handsome.

These female peddlers are slaves belonging either to persons who keep dry-goods stores or who are too poor to furnish a store with goods, but who buy as many at auction as will fill a couple of baskets, which baskets are their shops. I understand that the whole of the retail trade in dry goods was carried on in this way before the United States got possession of the country. It was not then, nor is it now, the fashion for ladies to go shopping. The creole families stick still to the peddlers. Although many inducements are held out by the better arrangement and exhibition of the shops to the ladies to buy, still, as in everything else, the old habit wears away very slowly. I am informed that it is a very unprofitable mode of dealing; that the infidelity of the peddlers, their ignorance or forgetfulness of prices at which they ought to sell, and the slow sales, render it even more so than it might be. But it is continued by two circumstances: by the dependence of those who live by the labor of their slaves upon this traffic, and by the necessity thus imposed upon the shopkeepers to meet their petty rivals on the same ground, this retail trade is so far worthy of notice as it forms one of the characteristic features of this city at present.

The existence of slavery brings with it many things which seem contradictory. Servants who are slaves are always treated with more familiarity than hirelings; probably because if you indulge and behave familiarly to a hireling you cannot, if he presume upon it, correct him as you can a slave, and make him feel his inferiority by corporal punishment. Therefore we find cruelty and confidence, cowhiding and caressing, perfectly in accord with one another among the creoles of this place and their slaves.

There are poor creole families and individuals who live upon the labor of their slaves. Their fuel is collected by them wherever they can find it, and the house is kept either by the petty traffic above described or by some other species of industry of the slaves, in which the master or mistress takes no share. I have heard of mistresses who beat their slaves cruelly if they do not bring them a sufficient sum of money to enable them to keep the house or fuel to warm them. I know, also in my neighborhood, an old, decrepit woman who is maintained entirely by an old slave whom she formerly emancipated, but who, on her mistress getting old and helpless, returned to her and devoted her labor to her support.

Judge M—— , of this city, a severe miser and very rich, is said to be entirely maintained by his slaves, to a few of whom he has given the liberty to earn as much as they can for themselves, provided they kept a good table for him.

March 18, 1819.

I went, this morning, with Mr. Planton to see his wife’s picture of the Treaty of Ghent. It is an excellent painting in many points of view, and there are parts of it, separate figures and groups, that have very extraordinary merit. But its inherent sin, especially in America, is its being an allegorical picture. When the mythology of antiquity was the substance of its religion, and the character and history of every deity were known to every individual of the nation, allegorical representations were a kind of written description of the subject represented, and might be generally understood. But since Hercules and Minerva and the rest of the deities are in fashion only as decorations of juvenile poetry, and are known by character only to those few who have had classical educations, an allegorical picture stands as much in need of an interpreter as an Indian talk.

Mrs. Planton has painted exceedingly well, but has judged very ill. In another respect, also, her American feeling has betrayed her into error. She has painted a picture of the largest size in oil, of course a picture calculated for duration, and forming an historical record, to represent evanescent feelings, the feelings of unexpected and, of course, riotous and unreasonable triumph. Britannia is represented as laying her flag, her rudder (emblems of naval superiority), her laurels, and other symbols of victory and dominion, at the feet of America, who approaches in a triumphal car. She kneels in the posture of an humble suppliant, while Hercules and Minerva threaten her with the club and the spear: all this is caricature. But the whole of this group, excepting Hercules, is admirably painted. The figure of Britannia is very graceful and well drawn, and the drapery has superior merit. The group on the right is also uncommonly well conceived and executed. The whole picture does, indeed, infinite credit to the artist and to her country, for she is a Philadelphian. The great fault is the choice of the subject, for the signing of negotiation of a treaty, as a matter of fact, can at best be but a collection of expressive likenesses of persons writing or conversing, and has nothing picturesque about it. Strength, fortitude, courage, and some good luck, on our side, were not wanting to “conquer the treaty,” in the French fashionable phrase; and admirable talent was displayed in the negotiation. But these are not very well paintable.

As to allegory, generally it is a most difficult branch of the art of the painter and sculptor, and belongs rather to the poetical department. Yet sometimes the sculptor and painter have succeeded in rendering sentiment Intelligible by the chisel and pencil; for instance, in the personification of Peace, by Canova, where a pair of doves make their nest in a helmet.

Some years ago Dr. Thornton, of Washington, described, before a large company, the allegorical group which it was his intention, as commissioner of the city of Washington, to place in the center of the Capitol, around the statue of the general.

“I would,” said he, “place an immense rock of granite in the center of the dome. On the top of the rock should stand a beautiful female figure, to represent Eternity or Immortality. Around her neck, as a necklace, a serpent — the rattlesnake of our country — should be hung, with its tail in its mouth — the ancient and beautiful symbol of endless duration. At the foot of the rock another female figure, stretching her hands upward in the attitude of distressful entreaty, should appear, ready to climb the steep. Around her a group of children, representing Agriculture, the Arts and Sciences, should appear to join in the supplication of the female. This female is to personify Time, or our present state of existence. Just ascending the rock, the noble figure of General Washington should appear to move upward, invited by Immortality, but also expressing some reluctance in leaving the children of his care.

“There,” said he, “Mr. Latrobe, is your requisite in such works of art; it would represent a matter of fact, a truth, for it would be the very picture of the general’s sentiments, feelings, and expectations in departing this life — regret at leaving his people, but hoping and longing for an immortality of happiness and of fame. You yourself have not ingenuity suflicient to pervert its meaning, and all posterity would understand it.”

The doctor was so full of his subject that I was unwilling to disturb his good humor; but I said that I thought his group might tell a very different story from what he intended. He pressed me so hard that at last I told him that, supposing the name and character of General Washington to be forgotten, or at least that the group had been found in the ruins of the Capitol, and the learned antiquarians of two thousand years hence were assembled to decide its meaning, I thought then that they would thus explain it:

“There is a beautiful woman on the top of a dangerous precipice, to which she invites a man, apparently well enough inclined to follow her. Who is this woman? Certainly not a very good sort of a one, for she has a snake about her neck. The snake indicates, assuredly, her character — cold, cunning, and poisonous. She can represent none but some celebrated courtesan of the day. But there is another woman at the foot of the rock, modest and sorrowful, and surrounded by a family of small children. She is in a posture of entreaty, and the man appears half-inclined to return to her. She can be no other than his wife. What an expressive group! How admirable the art which has thus exposed the dangerous precipice to which the beauty and the cunning of the abandoned would entice the virtuous, even to the desertion of a beautiful wife and the mother of a delightful group of children!”

I was going on, but the laughter of the company and the impatience of the doctor stopped my mouth. I had said enough, and was not easily forgiven.

March 22, 1819.