Adah Isaacs Menken.

Infelicia. “Introduction.”

“Leaves pallid and sombre and ruddy,

Dead fruits of the fugitive years:

Some stained as with wine and made bloody,

And some as with, tears.”

TO

CHARLES DICKENS.

INTRODUCTION.

THE materials for a biography of Adah Isaacs Menken are meager enough. A magazine article here and there, a few words in this or that book of reminis cences, a wretched little pamphlet issued in 1868, vilely written and vilely printed, whose credibility is on a par with its impossible grammar, — these are the only memorials of the brilliant and beautiful woman who twenty-five years ago was the talk of two continents. The stormful life is over, the passionate heart is at rest, the queenly body is dust, and the jealous past has left us naught of value save this handful of verses which you can read through in an hour — which, once read, you can never forget.

Let us try, however, to piece together the few items of personal history that can be depended on as authentic. Adah’s baptismal name was Adelaide McCord. She was born June 15, 1835, within a few miles of New Orleans, La., at a place then known as Chartrain, and now as Milneburg. At the time of her birth her father, James McCord, was a merchant in good circumstances, but business reverses overtook him; and when she was barely when she was eight years old, he died, leaving two children besides Adelaide (both younger than herself), a widow — and nothing else.

Luckily, Mr. McCord had been an ardent lover of dancing, and had put his little girls, almost as soon as they could use their legs, under the tuition of a French dancing-master. Their progress had been astonishing, and it was probably through the dancing-master’s influence that Mrs. McCord, driven by poverty, secured a position for her two daughters in the ballet at the New Orleans Opera-house. They were known to the public as the Theodore sisters, and soon became great favor ites not only before, but behind, the footlights.

Adah was far the brighter, the cheerier, the more arch and piquant. She early developed a passionate love of study, and even as a child, worn out as she was by re hearsals and performances, she devoted her spare time to mastering Spanish, French, and the classic languages. At the age of twelve she is said to have begun a translation of Homer’s Iliad — “completing her arduous task with triumph,” says her early biographer, whose word can hardly be received, however, unless he knew Greek a great deal better than he knew English. At fourteen she was a woman, and her marvelous beauty had cap tured the town. Before she was seventeen she had mar ried a nobody whose very name seems to have been for gotten, who treated her cruelly, and who finally abandoned her.

We next hear of her, still in her teens, as the “Queen of the Plaza,” the favorite danseuse at the Tacon Theatre in Havana. Returning to the United States, she wandered out to one of the newly-created cities of Texas to assist an amateur company which, in dire need of a competent actress, had sent down to New Orleans for the purpose.

|

|

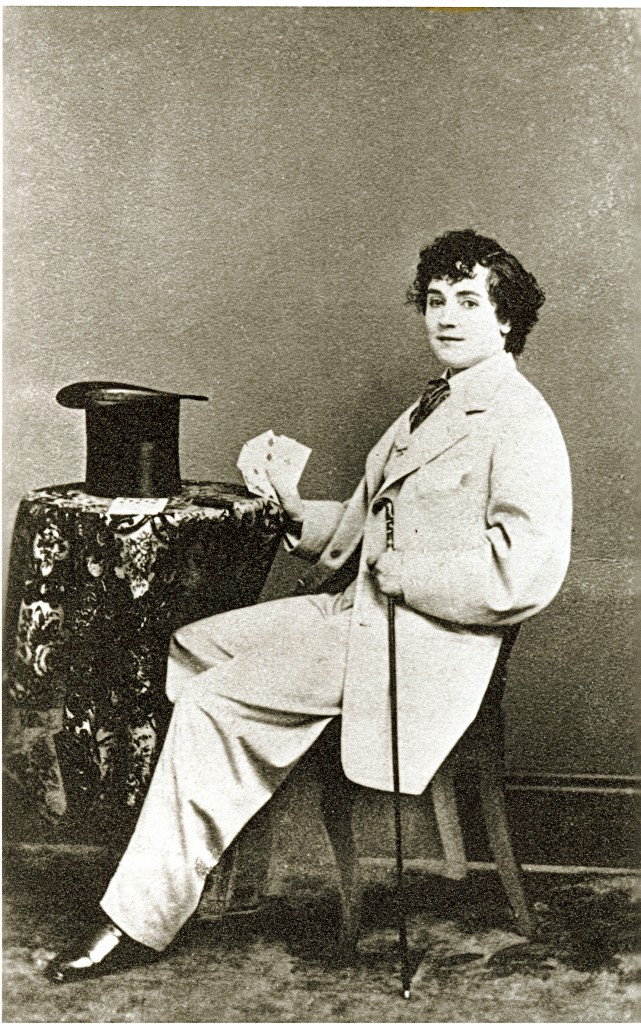

Adah Isaacs Menken.

Age 19 in 1854. Public domain photo by Wikipedia

|

For a few months she buried herself in the wilds of the new State. At Liberty, Texas, she established a paper which had a very brief existence, and at Port Levanca she met with an extraordinary adventure which was a fitting prelude to a romantic career. A hunting-party that she had joined one bright morning fell in with an ambush of Indians, who captured her and Gus Varney, an arrant coward in the party. An Indian girl called Laulerack — herself a captive from another tribe, reserved for a repugnant wedding — took pity on the white maiden, and they both seized an opportune moment to make their escape from the camp. No one witnessed their flight save the dastard Varney, who gave an alarm in the hope of currying favor with his captors. The two maidens, hotly pursued by the Indians, fell in, as luck would have it, with a camp of rangers. Before any explanations could be made, a rifle-shot from the surprised camp wounded Laulerack to death. Hurried explanations followed. The rangers, apprised in a moment of the situation, started out to meet the Indians, defeated them, took five prisoners, and rescued Varney, whose treachery Adelaide was too noble to expose. This story is told on the authority of William Wallis, an actor who claimed to have heard it from Adah’s own lips. It is added that the poem here given as “A Memory” was originally entitled “Laulerack,” and was written in memory of the Indian maiden.

Adah returned to New Orleans with the intention of giving up the stage and devoting her attention to liter ature. She began by studying assiduously the German language and reading the classic authors, supporting her self, meanwhile, by teaching French and Latin in a young ladies’ seminary, and by contributing to the New Orleans papers. A volume of poems which she published at about this time met with considerable popular favor.

But her restless spirit could not find peace. She returned to Texas, and at Galveston, on the 3d of April, 1856, she married Alexander Isaac Menken, a musician. Her husband was a Jew, and she herself adopted his faith, changing her name from Adelaide to Adah.

Again she turned her attention to the stage, and during the season of 1856-57 appeared at the Varieties Theatre, New Orleans, in the play of “Fazio.” Her début as an actress was a triumphant success: the theatre was crowded, and the cheers of welcome which greeted her entrance on the stage are described as deafening. For some time it was impossible for her to speak; when she could be heard, she put forth every effort to please, and, though not gifted with any great histrionic talents, her magnificent presence carried her through the ordeal successfully.

A pleasant glimpse is afforded of herself and her hus band at this time by Celia Logan. “Our family,” says Miss Logan, “was intimate with theirs, and one evening Olive and I were at a little child’s party — at which, of course, there were many elderly people — and on this occa sion I first saw Isaac Menken and his wife. There had been trouble about his marrying Adah, the reason of which I was too young to understand; but the old folks had concluded to make the best of it, and this was the proud young husband’s presentation of his bride to his family. Never shall I forget the hush which fell even upon the children as the pair paused a moment at the door, as if to ask permission to enter. Adah Menken must at that time have been one of the most peerless beauties that ever dazzled human eyes, while Isaac him self was a remarkably handsome man, with a countenance as intelligent as the expression was noble. How little any of these happy people present that night foresaw the gloomy fate that awaited that strange and gifted girl! In after-years, whoever threw a stone at Adah, it was never Isaac Menken, and, no matter what other ties she con tracted, she always retained his name, only adding a final ‘s’ to the Isaac, so much of the glamour of the first love hung over them both to the bitter end.”

From New Orleans, Adah went to Wood’s Theatre in Cincinnati, then to Louisville, and afterward, as the leading lady of W. H. Crisp’s dramatic company, she traveled through the Southern States, supporting several eminent actors, one of whom was Edwin Booth. Then she retired for another brief period, and studied sculp ture in the studio of T. D. Jones at Columbus, Ohio, contributing, also, to various newspapers. Shortly after ward, at Cincinnati, she became the principal contributor to The Israelite, then the leading Jewish paper in America. Her scathing reply to a bigoted article that appeared in The Churchman on the question of Baron Rothschild’s admission to Parliament traveled the rounds of the papers in America, was copied extensively in England, and was translated for several of the leading journals in France and Germany. The baron sent her a letter of thanks in his own handwriting, in which he called her the inspired Deborah of her adopted race.

But the old hankering after the stage overcame her again. At Dayton, Ohio, she scored a great success. She had affected the military, and learned the art of drilling so perfectly that she was elected captain of the Life-Guards in that place. It was about this time that she met the celebrated prize-fighter John C. Heenan, familiarly known as “The Benicia Boy.” On the 3d of April, 1859, she was married to him in New York City.

In New York she appeared first at the “National,” and afterward at the “Old Bowery,” in such plays as “The French Spy,” “The Soldier’s Daughter,” etc. She next traveled as a star through the Southern States, supporting James E. Murdoch. “I found her,” says Murdoch, in his book on The Stage, “to be a mere novice, and not at all qualified for the important position to which she had aspired. But she was anxious to improve and willing to be taught. A woman of personal attractions, she made herself a great favorite. She dashed at everything in tragedy and comedy with a reckless disregard of consequences, until, at length, with some degree of trepidation, she paused before the character of Lady Macbeth! I found in the first rehearsal that she had no knowledge of the part save what she had gained from seeing it performed by popular actresses of the day. She did not even know her lines.”

Mr. Murdoch sought to explain the character of Lady Macbeth and give a few general ideas of the action of the part; he then besought her to study the words. When the performance came off, she passed through her first scene with great applause, although she strayed far away from the text. But in the next scene she broke down. In the midst of the passionate denunciation which follows Macbeth’s assertion, “I dare do all that doth become a man,” she rushed over to Murdoch, and, laying her head on his shoulder, whispered, “I don’t know the rest.” “From that point Macbeth ceased to be the guilty thane and became a mere prompter in a Scotch kilt and tartans. For the rest of the scene I gave the lady the words. Clinging to my side in a manner very different from her former scornful bearing, she took them line by line before she uttered them, still, how ever, receiving vociferous applause, and particularly when she spoke of dashing out the brains of her child; until, at length, poor Macbeth, who was but playing a second fiddle to his imperious consort, was glad to make his exit from a scene where the honors were certainly not even.” The rest of the play Adah managed to get through with by “winging it” — i. e., by refreshing her memory in the wings while she was off the stage.

It was Mr. Murdoch, by the way, who suggested to her what in the end proved the great success of her life. “Adah,” said he one day, “why not adopt the sensational line? You have a pretty face and a good form, and possess grace enough to cope with Celeste,” a popular actress who had made a hit in “The French Spy.” Adah was hurt at this suggestion, deeming it a hint that she would never succeed in the legitimate drama.

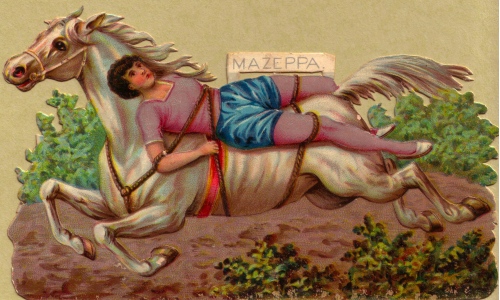

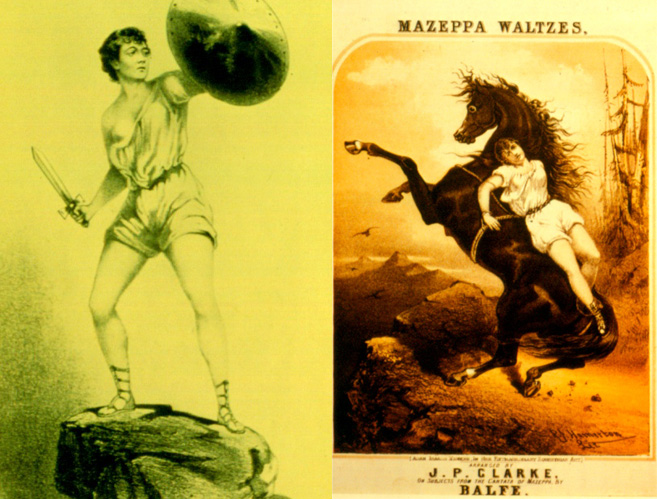

Nevertheless, the suggestion bore fruit. On June 7, 1861, Adah made her appearance at the Green Street Theatre, in Albany, in the character of Mazeppa.

The manager of that theatre was a Captain John B. Smith. He had been employing R. E. J. Miles to play the part, and it had been a great success. No woman had ever attempted it. But by a curious coincidence Captain Smith hit upon the same idea as Murdoch. Menken’s beauty had become the talk of the country. She had already been in Albany for a few weeks, and had become a favorite. It struck him that if Menken would consent to appear as the hero she would make a hit. He made his proposal, and received word from the actress, in St. Louis, that she was coming East and would do as requested.

On the Saturday before the performance she arrived. As usual, she arrived in total ignorance of her part — ignorance alike of the words and of the business. The company had gathered for rehearsal, but it would not do to let them know that the star was totally unprepared; so they were dismissed on the plea that Miss Menken was thoroughly fatigued with her journey. Then Captain Smith and Adah got down to serious work.

“Belle Beauty,” the horse she was to use, had already been trained to the business by R. E. J. Miles. He rode the act with but a single strap, and Adah was to do the same. A band was first securely fastened around the horse’s body. A strap was run through a loop in this band, and encircled the body of the performer, who held the ends in his hands, so that the closer he drew them together the closer he was held to the horse, but by letting go he was free at once.

“Now, Miss Menken,” said Captain Smith, “I will show you how it is done.”

He was lifted into place. The horse, true to its train ing, sprang forward from the footlights up an eighteen-inch run in the painted mountain.

Adah looked on, pale and trembling.

“I’d give every dollar I am worth,” she said, “if I were sure I could do that.”

Smith assured her there was no danger; she had only to hold on like death, and the horse would do the rest. Still she faltered, and begged that the horse, instead of starting from the footlights, be led up to the run. Smith humored her in this.

But he made a grievous error. The horse, thrown out of its usual routine, went only part way up, and then with an awful crash plunged off the planking upon the staging and timbers beneath. Menken was lifted up, pale, almost lifeless, with the blood streaming from her shoulder. A doctor was summoned. He found that she was not seriously injured, but declared she could not appear on Monday evening. He little knew whom he had to deal with. Adah’s blood was up; she swore that she would go on with the rehearsal then and there. All efforts to dissuade her were unavailing. She resumed her place on the horse as soon as it could be sufficiently calmed; and this time the feat was performed in safety.

The performance on Monday was witnessed by a crowd that packed the theatre from pit to dome. The fame of the performance was heralded all over the country. After a six weeks’ run in Albany, Miss Menken played the part in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and New York, drawing large crowds to every performance.

Meanwhile, she had married again. In October, 1861, she was united to R. H. Newell, the humorist — better known as “Orpheus C. Kerr” — and nearly a year later was divorced from J. C. Heenan by an Indiana court. It was generally known that Heenan had treated her in the most brutal and ignominious manner.

With her new husband she started for California in July, 1863, and made her appearance in the opera-house as Mazeppa. In April, 1864, she sailed for England — alone — and was immediately secured for Astley’s Theatre, in London, where her American success was more than repeated. “Mazeppa” became the town-talk. During the latter part of 1865 she also appeared in a play entitled “The Child of the Sun,” written for her by John Brougham, which had a successful run for seven weeks.

During her absence in England she had been divorced from Mr. Newell, again by an Indiana court, and on returning to the United States one of her first acts was to take another husband, James Barclay (August 21, 1866). A month or two later she sailed back to England, played a short engagement in Liverpool, and then appeared in Paris, December 30, at the Gaiété Theatre, in a play written for her and entitled “Les Pirates de la Savanne.” She was called out nine times the first night, and at the close of her one hundred nights’ engagement there were present Napoleon III., the king of Greece, the duke of Edinburgh, and the prince imperial. Afterward she alternated between London, Vienna, and Paris. In London her rooms at the Westminster Hotel were frequented by such men as Charles Dickens, Charles Reade, Watts Phillips, John Oxenford, and Algernon Charles Swinburne; in Paris she was the intimate friend of Alexander Dumas and Theophile Gautier.

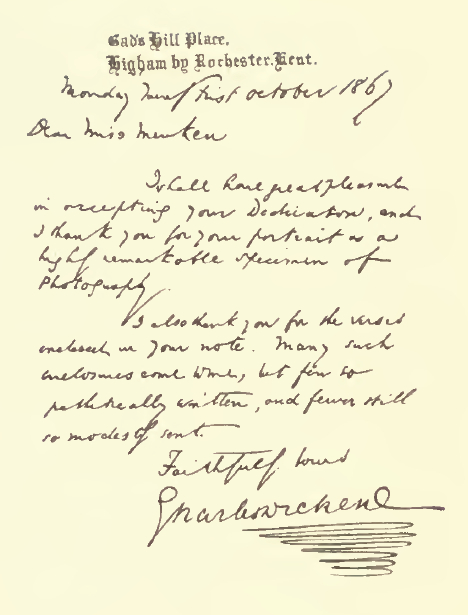

It was at the period of her greatest triumph, in 1867, that she collected her fugitive poems into the volume Infelicia, dedicated by permission, as the fac-simile autograph letter shows, to Charles Dickens.

In June, 1868, while in Paris attending rehearsals for the “Pirates de la Savanne,” in which she was to open in the beginning of July, Adah was stricken down with sickness. She never rallied. On August 10 she died quietly and peacefully, attended by ministers of the Jewish faith. She was buried in Père la Chaise, and on her tombstone were inscribed, at her own request, the simple words “Thou knowest.”

Adah Isaacs Menken’s faults lay on the surface, and it is idle to attempt any concealment of them. But, with all her faults, she was a noble creature. Her generosity was unparalleled. She squandered money recklessly, but seldom upon herself. The attaches at the theatre, men, women, and children, were her beneficiaries, and even in the streets she would thrust handfuls of silver or rolls of bills in the hands of strangers who attracted her pity or liking. “No one cared less for money than Adah Isaacs Menken,” said a writer in the Boston Courier, “and, had her income been a thousand dollars a minute, she would have been poor at the end of an hour. While she loved a man she would cling to him with doglike fidelity, giving up everything, and exacting the same self-abandonment in return with a jealousy that was not only unreasonable, but unbearable. Sometimes, when her fiery temper was enraged by some real or fancied slight, she would go into a cataleptic fit that is described as terrible to witness. But she never said an ill word behind another’s back, no mat ter how brutally he might have injured her, and she never forgot a kindness.

Her poems are as erratic, as impulsive, as faulty, as her self. They may not have the true lyric form. The true lyric cry wails through them in defiance of form, and goes straight to the reader’s heart. “C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas la guerre,” might be the martinet’s criticism. But the martinet does not win all the battles.

Never was the anguish of a broken spirit put into more potent words than in such poems as “One Year Ago,” “My Heritage,” and “Infelix.” Even in her brightest poems there is no joy — nothing but a maddened sense of the impossibility of joy which has a sort of delirious ecstasy of its own. It is like the wail of a lost soul that has had a glimpse of heaven, and it appeals with sudden and blinding force to us poor creatures who, grossly hemmed in by our earthly senses, know neither hell nor heaven.

Text prepared by

- Michael Hoge

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Menken, Adah Isaacs. Introduction. Infelicia. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1902. iii-xiv. Internet Archive. 30 Sept. 2006. Web. 11 May 2014. <https:// archive.org/ details/ infelici00 menkiala>.