Katherine Pyle.

“The Talking Eggs.”

There was once a widow who had two daughters, one named Rose and the other Blanche.

Blanche was good and beautiful and gentle, but the mother cared nothing for her and gave her only hard words and harder blows; but she loved Rose as she loved the apple of her eye, because Rose was exactly like herself, coarse-looking, and with a bad temper and a sharp tongue.

Blanche was obliged to work all day, but Rose sat in a chair with folded hands as though she were a fine lady, with nothing in the world to do.

One day the mother sent Blanche to the well for a bucket of water. When she came to the well she saw an old woman sitting there. The woman was so very old that her nose and her chin met, and her cheeks were as wrinkled as a walnut.

“Good day to you, child,” said the old woman.

“Good day, auntie,” answered Blanche.

“Will you give me a drink of water?” asked the old woman.

“Gladly,” said Blanche. She drew the bucket full of water, and tilted it so the old woman could drink, but the crone lifted the bucket in her two hands as though it were a feather and drank and drank till the water was all gone. Blanche had never seen any one drink so much; not a drop was left in the bucket.

“May heaven bless you!” said the old woman, and then she went on her way.

And now Blanche had to fill the bucket again, and it seemed as though her arms would break, she was so tired. —

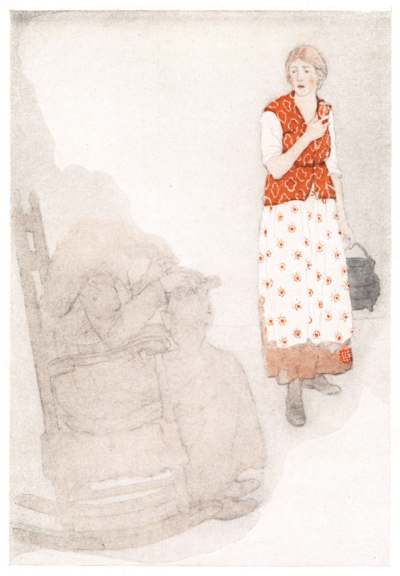

When she went home her mother struck her because she had tarried so long at the well. Her blows made Blanche weep. Rose laughed when she saw her crying.

The very next day the mother became angry over nothing and gave Blanche such a beating that the girl ran away into the woods; she would not stay in the house any longer. She ran on and on, deeper and deeper into the forest, and there, in the deepest part, she met the old woman she had seen beside the well.

“Where are you going, my child? And why are you weeping so bitterly?” asked the crone.

“I am weeping because my mother beat me,” answered Blanche; “and now I have run away from her, and I do not know where to go.”

“Then come with me,” said the old woman. “I will give you a shelter and a bite to eat, and in return there is many a task you can do for me. Only, whatever you may see as we journey along together you must not laugh nor say anything about it.”

Blanche promised she would not, and then she trudged away at the old woman’s side.

After a while they came to a hedge so thick and wide and so set with thorns that Blanche did not see how they could pass it without being torn to pieces, but the old hag waved her staff, and the branches parted before them and left the path clear. Then, as they passed, the hedge closed together behind them.

Blanche wondered but said nothing.

A little further on they saw two axes fighting together with no hand to hold them. That seemed a curious thing, but still Blanche said nothing.

Further on were two arms that strove against each other without a sound. Still Blanche was silent.

Further on again two heads fought, butting each other like goats. Blanche looked and stared but said no word. Then the heads called to her. “You are a good girl, Blanche. Heaven will reward you.”

After that she and her companion came to the hut where the old woman lived. They went in, and the hag bade Blanche gather some sticks of wood and build a fire. Meanwhile she sat down beside the hearth and took off her head. She put it in her lap and began to comb her hair and twist it up.

Blanche was frightened, but she held her peace and built the fire as the old woman had directed. When it was burning the old woman put back her head in place, and told Blanche to look on the shelf behind the door. “There you will find a bone; put it on to boil for our dinners,” said she.

Blanche found the bone and put it on to boil, though it seemed a poor dinner.

The old woman gave her a grain of rice and bade her grind it in the mortar. Blanche put the rice in the mortar and ground it with the pestle, and before she had been grinding two minutes the mortar was full of rice, enough for both of them and to spare.

When it was time for dinner she looked in the pot and it was full of good, fresh meat. She and the old woman had all they could eat.

After dinner was over the old woman lay down on the bed. “Oh, my back! Oh, my poor back! How it does ache,” groaned she. “Come hither and rub it.”

Blanche came over and uncovered the old crone’s back, and she was surprised when she saw it; it was as hard and ridgy as a turtle’s. Still she said nothing but began to rub it. She rubbed and rubbed till the skin was all worn off her hand.

“That is good,” said the old woman. “Now I feel better.” She sat up and drew her clothes about her. Then she blew upon Blanche’s hand, and at once it was as well as ever.

Blanche stayed with the old woman for three days and served her well; she neither asked questions nor spoke of what she saw.

At the end of that time her mistress said to her, “My child, you have now been with me for three days, and I can keep you here no longer. You have served me well, and you shall not lack your reward. Go to the chicken-house and look in the nests. You will find there a number of eggs. Take all that say to you, ‘Take me,’ but those that say, ‘Do not take me,’ you must not touch.”

Blanche went out to the chicken-house and looked in the nests. There were ever so many eggs; some of them were large and beautiful and white and shining and so pretty that she longed to take them, but each time she stretched out her hand toward one it cried, “Do not take me.” Then she did not touch it. There were also some small, brown, muddy-looking eggs, and these called to her, “Take me!” So those were the ones she took.

When she came back to the house the old woman looked to see which ones she had taken. “You have done what was right,” said she, “and you will not regret it.” She then showed Blanche a path by which she could return to her own home without having to pass through the thorn hedge.

“As you go throw the eggs behind you,” she said, “and you will see what you shall see. One thing I can tell you, your mother will be glad enough to have you home again after that.”

Blanche thanked her for the eggs, though she did not think much of them, and started out. After she had gone a little way she threw one of the eggs over her shoulder. It broke on the path, and a whole bucket full of gold poured out from it. Blanche had never seen so much gold in all her life before.

She gathered it up in her apron and went a little farther, and then she threw another egg over her shoulder. When it broke a whole bucket full of diamonds poured out over the path. They fairly dazzled the eyes, they were so bright and sparkling.

Blanche gathered them up, and went on farther, and threw another egg over her shoulder. Out from it came all sorts of fine clothes, embroidered and set all over with gems. Blanche put them on, and then she looked like the most beautiful princess that ever was seen.

She threw the last egg over her shoulder, and there stood a magnificent golden coach drawn by four white horses, and with coachman and footman all complete. Blanche stepped into the coach, and away they rolled to the door of her mother’s house without her ever having to give an order or speak a word.

When her mother and sister heard the coach draw up at the door they ran out to see who was coming. There sat Blanche in the coach, all dressed in fine clothes, and with her lap full of gold and diamonds.

Her mother welcomed her in and then began to question her as to how she had become so rich and fine. It did not take her long to learn the whole story.

Nothing would satisfy her but that Rose should go out into the forest, and find the old woman, and get her to take her home with her as a servant.

Rose grumbled and muttered, for she was a lazy girl and had no wish to work for any one, whatever the reward, and she would rather have sat at home and dozed; but her mother pushed her out of the door, and so she had to go.

She slouched along through the forest, and presently she met the old woman. “Will you take me home with you for a servant?” asked Rose.

“Come with me if you will,” said the old woman, “but whatever you may see do not laugh nor say anything about it.”

“I am a great laugher,” said Rose, and then she walked along with the old woman through the forest.

Presently they came to the thorn hedge, and it opened before them just as it had when Blanche had journeyed there. “That is a good thing,” said Rose. “If it had not done that, not a step farther would I have gone.”

Soon they came to the place where the axes were fighting. Rose looked and stared, and then she began to laugh.

A little later they came to where the arms were striving together, and at that Rose laughed harder still. But when she came to where the heads were butting each other, she laughed hardest of all. Then the heads opened their mouths and spoke to her. “Evil you are, and evil you will be, and no luck will come through your laughter.”

Soon after they arrived at the old woman’s house. She pushed open the door, and they went in. The crone bade Rose gather sticks and build a fire; she herself sat down by the hearth, and took off her head, and began to comb and plait her hair.

Rose stood and looked and laughed. “What a stupid old woman you are,” she said, “to take off your head to comb your hair!” and she laughed and laughed.

The old woman was very angry. Still she did not say anything. She put on her head and made up the fire herself. Rose would not do anything. She would not even put the pot on the fire. She was as lazy at the old woman’s house as she was at home, and the old crone was obliged to do the work herself. At the end of three days she said to Rose. “Now you must go home, for you are of no use to anybody, and I will keep you here no longer.”

“Very well,” said Rose. “I am willing enough to go, but first pay me my wages.”

“Very well,” said the old woman. “I will pay you. Go out to the chicken-house and look for eggs. All the eggs that say, ‘Take me’, you may have, but if they say, ‘Do not take me’, then you must not touch them.”

Rose went out to the chicken-house and hunted about and soon found the eggs. Some were large and beautiful and white, and of these she gathered up an apronful, though they cried to her ever so loudly, “Do not take me.” Some of the eggs were small and ugly and brown. “Take me! Take me!” they cried.

“A pretty thing if I were to take you,” she cried. “You are fit for nothing but to be thrown out on the hillside.”

She did not return to the hut to thank the old woman or bid her good-by but set off for home the way she had come. When she reached the thorn thicket it had closed together again. She had to force her way through, and the thorns scratched her face and hands and almost tore the clothes off her back. Still she comforted herself with the thought of all the riches she would get out of the eggs.

She went a little farther, and then she took the eggs out of her apron. “Now I will have a fine coach to travel in the rest of the way,” said she, “and gay clothes and diamonds and money,” and she threw the eggs down in the path, and they all broke at once. But no clothes, nor jewels, nor fine coach, nor horses came out of them. Instead snakes and toads sprang forth, and all sorts of filth that covered her up to her knees and bespattered her clothing.

Rose shrieked and ran, and the snakes and toads pursued her, spitting venom, and the filth rolled after her like a tide.

She reached her mother’s house, and burst open the door, and ran in, closing it behind her. “Look what Blanche has brought on me,” she sobbed. “This is all her fault.”

The mother looked at her and saw the filth, and she was so angry she would not listen to a word Blanche said. She picked up a stick to beat her, but Blanche ran away out of the house and into the forest. She did not stop for her clothes or her jewels or anything.

She had not gone very far before she heard a noise behind her. She looked over her shoulder, and there was her golden coach rolling after her. Blanche waited until it caught up to her, and then she opened the door and stepped inside, and there were all her diamonds and gold lying in a heap. Her mother and Rose had not been able to keep any of them.

Blanche rode along for a long while, and then she came to a grand castle, and the King and Queen of the country lived there. The coach drew up at the door, and every one came running out to greet her. They thought she must be some great Princess come to visit them, but Blanche told them she was not a Princess, but only the daughter of a poor widow, and that all the fine things she had, had come out of some eggs an old woman had given her.

When the people heard this they were very much surprised. They took her in to see the King and Queen, and the King and Queen made her welcome. She told them her story, and they were so sorry for her they declared she should live there with them always and be as a daughter to them.

So Blanche became a grand lady, and after a while she was married to the Prince, the son of the old King and Queen, and she was beloved by all because she was so good and gentle.

But when Blanche’s mother and sister heard of the good fortune that had come to her, and how she had become the bride of the Prince, they were ready to burst with rage and spite. Moreover they turned quite green with envy, and green they may have remained to the end of their lives, for all that I know to the contrary.

Source

Pyle, Katharine. “The Talking Eggs.” Tales of Folk and Fairies. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1920. 123-136. Internet Archive. 7 December 2007. Web. 5 November 2013. <https:// archive.org/ details/ tales folkand fai00pyle goog>.

Page prepared by:

- Cody Hill

- Dantrel Hutchinson

- Bruce R. Magee

- Jordan Robinson